Episode 117: The Qur’an, Part 1: Overview

Learn the basics of the Qur’an – its size, structure, how and when it came together, and the book’s most important contents.

| Read Transcription | References and Notes |

| Quiz | |

| Episode on Spotify | Episode on Apple Podcasts |

| Previous Show | Next Show |

Episode 117: The Qur’an, Part 1: Overview

Gold Sponsors

David Love

Andy Olson

Andy Qualls

Bill Harris

Christophe Mandy

Jeremy Hanks

Laurent Callot

Maddao

ml cohen

Nate Stevens

Olga Gologan

Steve baldwin

Silver Sponsors

Lauris van Rijn

Alexander D Silver

Boaz Munro

Charlie Wilson

Danny Sherrard

David

Devri K Owen

Ellen Ivens

Evasive Species

Hannah

Jennifer Deegan

John Weretka

Jonathan Thomas

Michael Davis

Mike Roach

rebye

Susan Hall

Top Clean

Sponsors

Katherine Proctor

Carl-Henrik Naucler

Joseph Maltby

Stephen Connelly

Chris Guest

Matt Edwards

A Chowdhury

A. Jesse Jiryu Davis

Aaron Burda

Abdul the Magnificent

Aksel Gundersen Kolsung

Alex Metricarti

Andrew Dunn

Anthony Tumbarello

Ariela Kilinsky

Arvind Subramanian

Basak Balkan

Bendta Schroeder

Benjamin Bartemes

Brian Conn

Carl Silva

Charles Hayes

Chief Brody

Chris Auriemma

Chris Brademeyer

Chris Ritter

Chris Tanzola

Christopher Centamore

Chuck

Cody Moore

Daniel Stipe

David Macher

David Stewart

Denim Wizard

Doug Sovde

Earl Killian

Elijah Peterson

Eliza Turner

Elizabeth Lowe

Eric McDowell

Erik Trewitt

Francine

Friederike Otto

FuzzyKittens

Garlonga

Glenn McQuaig

J.W. Uijting

James McGee

Jason Davidoff

Jay Cassidy

JD Mal

Jill Palethorpe

Joan Harrington

joanna jansen

Joe Purden

John Barch

John-Daniel Encel

Jonah Newman

Jonathan Whitmore

Jonathon Lance

Joran Tibor

Joseph Flynn

Joshua Edson

Joshua Hardy

Julius Barbanel

Kathrin Lichtenberg

Kathy Chapman

Kyle Pustola

Lat Resnik

Laura Ormsby

Le Tran-Thi

Leonardo Betzler

Maria Anna Karga

Marieke Knol

Mark Griggs

MarkV

Matt Hamblen

Maury K Kemper

Michael

Mike Beard

Mike Sharland

Mike White

Morten Rasmussen

Mr Jim

Nassef Perdomo

Neil Patten

Nick

noah brody

Oli Pate

Oliver

Pat

Paul Camp

Pete Parker

pfschmywngzt

Richard Greydanus

Riley Bahre

Robert Auers

Robert Brucato

De Sulis Minerva

Rosa

Ryan Goodrich

Ryan Shaffer

Ryan Walsh

Ryan Walsh

Shaun

Shaun Walbridge

Sherry B

Sonya Andrews

stacy steiner

Steve Grieder

Steven Laden

Stijn van Dooren

SUSAN ANGLES

susan butterick

Ted Humphrey

The Curator

Thomas Bergman

Thomas Leech

Thomas Liekens

Thomas Skousen

Tim Rosolino

Tom Wilson

Torakoro

Trey Allen

Troy

Valentina Tondato Da Ruos

vika

Vincent

William Coughlin

Xylem

بِسْمِ ٱللَّهِ ٱلرَّحْمَـٰنِ ٱلرَّحِيمِ ١

In the name of God, the Lord of Mercy, the Giver of Mercy!

ٱلْحَمْدُ لِلَّهِ رَبِّ ٱلْعَـٰلَمِينَ ٢

Praise belongs to God, Lord of the Worlds,

ٱلرَّحْمَـٰنِ ٱلرَّحِيمِ ٣

the Lord of Mercy, the Giver of Mercy,

مَـٰلِكِ يَوْمِ ٱلدِّينِ ٤

Master of the Day of Judgment

إِيَّاكَ نَعْبُدُ وَإِيَّاكَ نَسْتَعِينُ ٥

It is You we ask for help.

ٱهْدِنَا ٱلصِّرَٰطَ ٱلْمُسْتَقِيمَ ٦

Guide us to the straight path:

صِرَٰطَ ٱلَّذِينَ أَنْعَمْتَ عَلَيْهِمْ غَيْرِ ٱلْمَغْضُوبِ عَلَيْهِمْ وَلَا ٱلضَّآلِّينَ ٧

the path of those You have blessed, those who incur no anger and have not gone astray.1

Hello, and welcome to Literature and History. Episode 117: The Qur’an, Part 1: Overview. In this program we will first introduce the Qur’an and learn the basic facts about it, including nomenclature necessary for understanding the book, its size and contents, and its organization and language. Then, we’ll learn about what are believed to be some of the very earliest verses of the Qur’an. We’ll explore some of the main subjects of the book, including what the Qur’an says about God and the world, creation and humanity, and judgment day, and heaven and hell. We’ll hear some more Qur’anic Arabic like we did a moment ago, and then at the end, we’ll learn a bit about academic scholarship on the Qur’an.

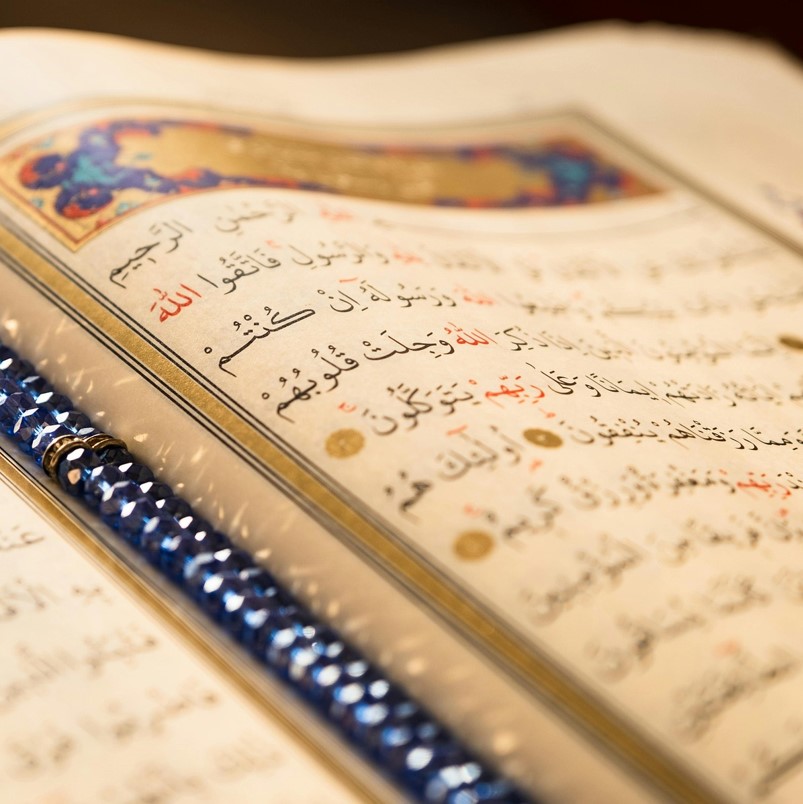

In much of the world today, the Qur’an has been the most influential book ever written. From a linguistic perspective alone, the revelations of the Prophet Muhammad have shaped the words that many of us use today. Modern Persian was born from the confluence of Qur’anic Arabic and Middle Persian, and through modern Persian, Arabic words are widely present in Kurdish and Pashto. Islamic regimes put Arabic phraseology in Urdu, Bengali, Punjabi, and Sindhi, and elsewhere, in Berber, Swahili, Hausa, Malay, and Indonesian. Because the Arabic Qur’an, and not vernacular translations of the Qur’an, is used in formal liturgy in Islam, Muslims from all over the world meet and pray together reciting the same Qur’anic verses in the same language that Muhammad did starting in the year 610 CE. No words, in all of human history, have probably been repeated more than Surat al-Fatihah, the Qur’an’s first surah, recited by hundreds of millions of Muslims numerous times a day. You just heard it a moment ago, in Qur’anic Arabic, and then in the Oxford Haleem translation. But Surat al-Fatihah is just the first chapter of one of humanity’s most beloved books, a book that, after a considerable 116-episode windup and full biography of the Prophet Muhammad, it is now time to put on our podcast’s proverbial desk, and spend some time with. [music]

Let’s start very simple. The Qur’an is a text of about 77,000 words. This brings it to a length of 446 pages in the popular Oxford World’s Classics Haleem translation. By contrast, a Catholic Bible – one of the longer Bibles – has about 780,000 words, making it more than ten times the length of the Qur’an, if that helps you picture the book’s relative size. There is a reason for the Qur’an’s relative brevity. The Qur’an is not, like the Tanakh, or New Testament, an anthology of documents from different sources and time periods, but instead, a compilation of revelations from one person, over a fairly short period of time. The Qur’an is thus quite consistent in its language and ideology. The book’s name comes from the verb qara’a, which means, “to read,” or “to recite.” In what is generally understood to be the first verse ever revealed to the Prophet Muhammad, he was instructed, ٱقْرَأْ بِٱسْمِ رَبِّكَ ٱلَّذِى خَلَقَ, or “Recite in the Name of [your] Lord Who created,” or often “[Read] in the Name of [your] Lord Who created.”2 The word “al-Qur’an,” then, is most commonly translated as “Recitation,” and the book emphasizes at various junctures that it is to be chanted at a measured cadence or otherwise recited, as well as read.

The Qur’an is an Arabic text – at numerous junctures the book itself emphasizes that it’s in Arabic, as when God states in one of the surahs, “We sent it down as an Arabic Quran.”3 Many Muslims and non-Muslims around the world today read the Qur’an in translation, just as we are going to study it in English in our podcast. However, it’s worth remembering upfront here that in Islamic liturgy everywhere, the call to prayer, and the daily prayers are all undertaken in classical Arabic, and considered invalid in other languages. Though necessity has engendered translations of the Qur’an in many different languages, the book is also, ultimately, considered untranslatable. Its words are a melodious combination of Arabic prose and verse, and alternating between, and intermingling the two, the Qur’an describes itself as “the speech of a noble messenger, and not the speech of a poet.”4 The Qur’an itself, then, repeatedly emphasizes the uniqueness, and inimitability, of its compositional style, a style, in Islamic history, that has long been considered incomparable and unrivaled, as the book is the word of God. We will hear some more Qur’anic Arabic a little later in this program, in some verses considered especially beautiful examples of the Qur’an’s prosimetric style.

The Qur’an has 114 surahs, or what we can think of as chapters, though the Arabic word “surah” is better translated as “division” or “section.”5 The second surah, called al-Baqarah or “The Cow,” is the longest – about 30 pages in the Oxford Haleem paperback edition – and generally speaking, as you move forward through the Qur’an, the surahs become shorter and shorter. The surahs are not chronologically organized, and the 114 surahs of the Qur’an do not constitute 114 separate revelations. Instead, according to Islamic history, parts of surahs were often revealed to Muhammad at different intervals, such that any given surah, especially longer surahs, can be made up of many different revelations. According to tradition, Muhammad himself specified the organization of the verses within the surahs, and then the final order of the 114 surahs themselves, in addition to the names of the surahs as they exist today.6 Surahs are made up of ayat, or verses, and any given surah might have verses from a number of different revelations that the Prophet had. As a result, the organization of the Qur’an is neither topical, nor chronological. The verses within each surah change subject and direction quickly, and Islamic tafsirs, or commentaries, have explored the book’s unique organization for a long time.

Let’s very quickly talk about how the Qur’an came together. Muhammad’s world was predominantly one of oral, rather than written literature, and so during Muhammad’s 23 years as a prophet, the Qur’an flourished as a body of memorized recitations. Parts of the Qur’an were set down piecemeal during Muhammad’s life, on parchment, sheepskin, and even the broad shoulder blades of camels. According to tradition, although Muhammad never read nor wrote, he worked with numerous companions who wrote down the his revelations and let Muhammad proofread them to ensure their accuracy.7 The first recorder of the Qur’an was Zayd ibn Thabit, a young Medinan who knew Muhammad personally and was known for his own Qur’anic recitations. Zayd ibn Thabit, once again according to tradition, collected and collated all Qur’anic texts and put them into a single manuscript, giving this manuscript to the first Caliph, Abu Bakr. Abu Bakr gave the manuscript with the second Caliph, ‘Umar, and after ‘Umar passed away, the manuscript went to Muhammad’s widow and ‘Umar’s daughter Hafsah. By this time, it was 644, and Muhammad had been gone for twelve years. The third Caliph, ‘Uthman, knew that history was moving fast, and he wanted to make sure that the Qur’an was meticulously preserved for posterity, and so ‘Uthman ordered Zayd ibn Thabit, the Medinan who had organized the manuscript in the first place, to consult with others who had the Qur’an memorized, and then to produce a new, cross-checked codex. This codex, called the ‘Uthmanic codex, would have been produced some time around the beginning of ‘Uthman’s reign – again, 644, and not a bad date to remember, as it saw the completion of the Qur’an as it exists today, at least according to Sunni views. The ‘Uthmanic codex was afterward sent out to Mecca, Kufa, Basra, and Damascus, the epicenters of Islam at that time in 644, and the caliph ‘Uthman kept a copy for himself in Medina, too. Some traditions maintain that Muhammad’s son-in-law ‘Ali ibn Abi Talib, Islam’s fourth Caliph, also set down a copy of the Qur’an, and that other companions of the Prophet collected the verses of the Qur’an, too. However, excepting some small numbering variances, the Qur’an is a very standard text today across Sunnism and Shiism – again, 77,000 words and 114 surahs – and a little later in this sequence we’ll talk about the book’s textual history in a bit more detail.8 [music]

The Qur’an’s Style, Contents, and Compilation: An Overview

Now that we have a basic sense of the size, language, layout, and original compilation of the Qur’an, let’s very quickly talk about its contents. The organization of the Qur’an is, again, assorted, with each surah changing direction often, as verses from different revelations are situated right next to one another. Though the surahs can be challengingly varied to read through, on the whole, the Qur’an is still a very ideologically consistent text. The book emphasizes the oneness of God, and the need for everyone to revere God as the creator and sovereign of the universe. The Qur’an describes a bipartite afterlife, in which those who believe in God and act rightly will enjoy the pleasures of heaven, and those who fail to do so will suffer the punishments of hell. One of the names for the Qur’an in Islamic societies is al-Huda, or “the guide,” and as a guide, in addition to outlining the salvific monotheism I’ve just described, the Qur’an also includes precepts on how to conduct oneself with probity and truthfulness within human society, placing particular emphasis on individual responsibilities and accountability. The Qur’an follows the prophetic traditions of Judaism and Christianity, and has frequent references to Old Testament patriarchs from Adam onward, considering Jesus as a noble and true prophet in the line of other Biblical prophets. We should always remember, as we read these frequent references, that Muhammad’s Mecca was no further from Jerusalem than Constantinople or Rome were from Jerusalem, and that Arabia had long had populations of Jews, Christians, and moreover, that regional Abrahamic narratives would have been familiar to Arabs like Muhammad even a thousand years before the Prophet was born.

The Birmingham Qur’an Manuscript, its parchment carbon-dated from first half of the 600s, includes the end of Surat Maryam (19) and the beginning of Surat Ta Ha (20).

So that, from a very high altitude, is what the Qur’an is, how it came together, and what it contains. To get a little deeper into the book, we’ll need a plan. The Qur’an, like the Psalms in the Old Testament, is not a text that most people read straight through from beginning to end. It’s a dense text with a lot of compressed meaning in it, and due to its complexity and miscellaneous organization, readers rarely begin with the first surah and then close the book with the 114th. As with so many texts I cover in Literature and History, I invite you to get a copy and read it in a way that suits you, as the Qur’an has always been, and always will be, quite an appealing, approachable book in spite of some of the challenges it presents to new readers. For our purposes, in this podcast, we will subdivide our three 2-hour programs on the Qur’an into three main categories – Episode 117, Overview; Episode 118, Ordinances; and Episode 119, Origins. The episode to which you are currently listening, now that we’ve covered some very basic facts about the Qur’an, will explore the very earliest verses of the Qur’an, and then spend the majority of the rest of the time discussing the book’s statements about God and the world, creation and humanity, and judgment day, and heaven and hell, though we’ll also hear some more Qur’anic recitation and talk about academic scholarship on the Qur’an toward the end of this show.

The present program will not talk about Islamic Law in the Qur’an, as that is the subject of the next show – Episode 118: Ordinances, on the subject of the Qur’an’s regulatory framework and later Islamic Law. Finally, Episode 119: Origins will consider the Qur’an’s Abrahamic and Arabian theological heritage. Because we are about to open one of Earth’s great sacred books, let me repeat something I said prior to when we opened the New Testament, and before that, prior to when we opened the Tanakh. This is a podcast about cultural history. I don’t think anyone has ever been converted, or unconverted to anything while listening to it. The approach that we take in this podcast to texts is a historicist one. In other words, we try to study theology, philosophy, literature, and other subjects as part of a greater river of human cultural evolution. Historicism is not the best, nor the only way to study sacred texts. First pioneered in the nineteenth century by German scholars, historicism attempts to understand books, including sacred literature, within the cultural contexts that engendered them. If you are looking for Qur’anic instruction that is rooted in traditional Islamic faith, there are plenty of audio programs out there for you. While I’ve been familiar with the Qur’an for a long time, my only real strength in presenting the book to you is familiarity with the cultural and theological history that led up to it, and the historicist approach I mentioned a moment ago. Historicism is as biased as anything, but its partisanship more commonly results in reductive guesswork than categorical prejudice, and thus, of all the subjective approaches to sacred texts out there, I hope our podcast’s is as inoffensive as possible.

Let me make a note upfront on translations, too, before we jump in. Translating Qur’anic Arabic is legendarily difficult. Some verses of the book are exegetical warzones. There are multivalent meanings in the original text, and there are a number of seventh-century Arabic words that still puzzle scholars today. We have spent literally hundreds of hours reading texts in translation in Literature and History, and thus we can readily understand that the best sounding translation, and even the clearest translation, is not always the most accurate translation. This is the case with the Qur’an, too, because sometimes a contorted and impenetrable verse in English more faithfully represents what the Qur’an actually says than a verse that sounds luminous and beautiful. To help give you as detailed and faithful an introduction to the Qur’an as I can, I’m consulting at least four different translations at all times, and often looking at notes having to do with the original Arabic. While I will use several translations, unless otherwise noted, I’ll be quoting from the M.A.S. Abdel Haleem translation, first published by Oxford World’s Classics in 2004. As always with our podcast, if you want the detailed chapter and verse of anything I quote, it’s all available in the link to the episode transcription in your podcast app. [music]

Muhammad’s Earliest Revelations, and Where They Are in the Qur’an

The first revelation that the Muhammad ever had was in a cave at a place called Hira, just outside of Mecca. We discussed the dramatic story behind this revelation several episodes ago. Muhammad had, during his 40th year, begun going to this cave to be alone, and to think and worship for stretches of multiple days at a time.11 After his first revelation, terrified that he might be losing his mind, or that he might be misinterpreted as a mere poet, Muhammad considered killing himself, though the angel Gabriel stopped him.12 Muhammad returned, distraught, to his wife Khadija, asking her to cover him, and it was only after a consultation with Khadija’s cousin, a Christian Arab named Waraqah, that Muhammad began to believe that this revelation, and his vision of the angel Gabriel, had been the work of God. The revelation that Muhammad had, now the first five verses of Surat al-Alaq, the 96th surah of the Qur’an, is as follows. “[Recite]! In the name of your Lord who created: He created man from a clinging form. [Recite]! Your Lord is the Most Bountiful One who taught by the pen, who taught man what he did not know” (96:1-5).13 The word “recite” there is often translated as “read,” so, for clarification and just because these are such central verses, let’s hear that one more time with the imperative “read” instead of “recite.” “Read! In the name of your Lord who created: He created man from a clinging form. Read! Your Lord is the Most Bountiful One who taught by the pen, who taught man what he did not know.”

A Qur’anic manuscript from Kashmir from around 1821-2 with 15 lines per page and marginal commentary.

The words “Read! In the name of your Lord who created: He created man from a clinging form. Read! Your Lord is the Most Bountiful One who taught by the pen, who taught man what he did not know” – these words teach us something else about the Qur’an. That is that the Qur’an is intended as an instructive text, and one written in the tradition of earlier prophetic history. The Qur’an is familiar with the narratives of the Tanakh, and the New Testament, both of which it considers esteemed and respectable. The Qur’an presents itself as a capstone to all earlier Abrahamic scriptures. When we learned about the Old Testament in our podcast a hundred episodes ago, we subdivided it into four main parts – the Pentateuch, the Historical Books, the Wisdom Books, and the Prophetic Books. If I had to classify the Qur’an within these four categories, I would say that the Qur’an most closely resembles the Wisdom literature of particularly the Second Temple period, having more of the measured, mellow confidence of the Wisdom of Solomon or Ecclesiastes than the dour doomsaying of Jeremiah. So, that takes us through the earliest five verses of the Qur’an – we only have 6,231 to go.

Let’s hear verses from another very early revelation. These are from Surat al-Qalam, or “The Pen,” and they show God assuring Muhammad that the Prophet was not a madman, and telling Muhammad to be patient. Surat al-Qalam says, in the Oxford Haleem translation,

By the pen! By all they write! You [Prophet] are not, by [receiving] God’s grace, a madman. . .and soon you will see, as will they, which of you is afflicted with madness. . .There will be Gardens of bliss for those who are mindful of God. . .So [Prophet] leave those who reject this revelation to Me: We shall lead them on, step by step, in ways beyond their knowledge; I will allow them more time, for My plan is powerful. (68.1-2, 34, 44-5)

These verses, as well, can teach us plenty about the rest of Qur’an. If you are new to the book, one of its surprising elements is how much of Muhammad’s own autobiography is in the Qur’an. In many surahs, after describing, or alluding to specific things happening in Muhammad’s life, God instructs Muhammad, chides Muhammad, prods the Prophet, and, as we just saw, counsels Muhammad to have forbearance and be patient toward the skeptical world around him. These largely one-sided conversations show Muhammad himself receiving divine wisdom and counsel, much as in Augustine’s Confessions, Augustine records being humbled or inspired by realizations that Augustine had about God. The Qur’an, similarly, often shows the divine, restrained, gentle voice of God telling the silent Muhammad to be patient and gracious to a world that doesn’t always return the favor. This dialogic quality of the book gives it its unique intimacy – it is the voice of God speaking to a man who never, in the Qur’an, affects to be anything but a messenger.

The Qur’anic voice also uses a lush variety of sentence constructions and rhetorical strategies. “By the pen!” begins the passage we just heard in an exclamatory sentence, and then another, with anaphoric repetition: “By all they write.” The next sentence, a declarative one, addresses Muhammad and, by extension, the beleaguered believers, telling them “You. . .are not, by [receiving] God’s grace, a madman. . .and soon you will see, as will they, which of you is afflicted with madness,” in a rhetorical reversal of roles. Finally, we heard the following at the end of that quote: “[L]eave those who reject this revelation to Me: We shall lead them on, step by step. . .I will allow them more time.” There are grammatical shifts there – leave it to me, we will lead them on, I will allow them more time. These rhetorical shifts, in Arabic, are called iltifat, and they are a striking part of the Qur’an’s language. The voice of the book is urgent, and insistent – within any given surah, the Qur’an undertakes restless shifts between sentence types and pronouns – “[Leave them]. . .to me. . .We shall lead them on. . .I will allow them” – each shift inviting the reader to listen ever more closely.

The early revelations of the Qur’an often show God speaking gently toward Muhammad and imposing on the Prophet the gravity of Muhammad’s revelations. Surat al-Muzzammil, the 73rd surah, whose title can be translated as “enfolded,” addresses Muhammad as, “You [Prophet], enfolded in your cloak” (73.1), and another early revelation begins with “You, wrapped in your cloak, arise and give warning,” and then tells Muhammad, “Proclaim the greatness of your Lord; cleanse yourself; keep away from all filth; do not weaken, feeling overwhelmed; be steadfast in your Lord’s cause” (74.1-7). These reassuring verses have a universality to them, telling all believers to take heart and be calm, as Muhammad himself faced persecution and opposition, too. Not all of the early revelations merely counseled Muhammad to keep calm and carry on. Others told him that those who were set against him would suffer divine retribution. Surat al-Masad, or “The Palm Fiber,” is an oracle against Muhammad’s half-uncle Abu Lahab, which reads, “May the hands of Abu Lahab be ruined! May he be ruined too! Neither his wealth nor his gains will help him: he will burn in the Flaming Fire and so will his wife, the firewood-carrier, with a palm-fibre rope around her neck” (111.1-5). It is a grim vision of Abu Lahab’s coming fall, but in the various ninth century biographies of Muhammad, Abu Lahab appears as a particularly vicious opponent of the earliest Muslims.

Another early revelation, Surat at-Takwir, or “Rolling Up,” is a complete theological statement, containing much of what we’ve heard thus far from these early Meccan surahs – an assurance that God’s justice is coming, though a much gentler assurance than the one we just heard, together with an exhortation to believe. Surat at-Takwir, the Qur’an’s 81st surah, is also breathtakingly beautiful. Let’s hear it, this time in the Penguin Tarif Khalidi prosimetric translation:

In the name of God,

Merciful to all,

Compassionate to each!

When the sun is rolled up;

When the stars are cast adrift;

When the mountains are wiped out;

When pregnant camels are left unattended;

When wild animals are herded together;

When seas are filled to overflowing;

When souls are paired together;

When the newborn girl, buried alive, is asked

For what crime she was murdered;

When scrolls are unfolded;

When the sky is scraped away;

When hell-fire is kindled;

When the Garden is drawn near;

Then each soul will know what it has readied.

No indeed!

I swear by the planets,

Ascending or receding!

By the night when it slinks away

! By the morning when it respires!

This is the speech of a noble envoy:

He is a figure of great power,

In high esteem with the Lord of the throne

Obeyed in heaven, worthy of trust.

Your companion is not possessed;

He saw him on the open horizon.

Nor does he hold back what comes from the Unseen.

Nor is this the speech of an accursed demon.

So where are you heading?

This is but a Remembrance to mankind,

To any of you who wish to follow the straight path.

And you cannot do so unless God wishes,

Lord of the worlds.14

The revelation we just heard is an apocalyptic vision, like so many in the annals of Abrahamic prophecy. By the time Muhammad was born, apocalyptic oracles were more than a thousand years old, their general visions of pleasure for the pious and suffering for the sinners unspooling over the thousands of pages of prophets that stretch from Isaiah to John of Patmos, the author of the Christian book of Revelation, and after these, apocryphal apocalypse books and surely hundreds of lost visions of the end of the world. What makes Surat at-Takwir, remarkable in the ancient tradition of apocalyptic visions is the delicate balance of its imagery. Oceans seethe and the stars come loose from their orbits, but animals are herded, and a baby girl, killed by her parents in the ignorance before Islam for being born female, is granted divine justice. The sun is stowed away, but people are justly sorted. Hell blazes, but heaven is brought near, and daybreak breathes softly. Just as Jahili Arabic poets like Antarah ibn Shaddad performatively acknowledged their own virtuosity, the surah we just heard attests, “This is the speech of a noble envoy,” the very deftness and beauty of the passage’s language presented as evidence of the revelation’s divine origins.

Let’s pause for a moment and reflect on what we’ve learned so far from these very early Meccan revelations. The verses that we’ve just looked at were from Surahs 96, 68, 73, 74, 111, and 81, and to reiterate, these verses are scattered throughout later parts of the Qur’an, which is not organized according to the chronological order of Muhammad’s revelations. The verses that we’ve looked at so far have given us an idea of the often dialogic quality of the Qur’an – the surahs often show God speaking directly to Muhammad to offer the Prophet counsel and directives at specific junctures. The verses that we just looked at offered an introductory sense of the Qur’an’s linguistic richness – its variety in sentence structure, its rhetorical shifts, its deft and carefully balanced imagery, and moreover the power of the Qur’anic voice – its capacity to be urgent and insistent, but also sympathetic, warm, and close at hand. The verses that we just heard also give us some sense of the Qur’an’s Abrahamic heritage, including Abrahamic eschatology.

Another very early revelation is one that we’ve already heard – the surah which opened the present podcast episode. The first surah of the Qur’an is a short chapter called Surat al-Fatihah, which is often simply translated as “The Opening.” Let’s hear it again, this time in the N.J. Dawood translation, first published by Penguin in 1956 – to be clear, if you open a Qur’an to page one, this is what you read.

IN THE NAME OF GOD THE MERCIFUL THE COMPASSIONATE

Praise be to God, Lord of the Universe,

The Merciful, the Compassionate,

Sovereign of the Day of Judgement!

You alone we worship, and to You alone we turn for help.

Guide us to the straight path,

The path of those whom You have favoured,

Not of those who have provoked Your ire,

Nor of those who have lost their way.15

Surat al-Fatihah, or “The Opening,” is something that hundreds of millions of believers recite every day, although the recitation is of course in Qur’anic Arabic. Surat al-Fatihah is generally considered to be one of the earliest revelations that Muhammad had.16 The first words of the first Surah of the Qur’an are: “IN THE NAME OF GOD THE MERCIFUL THE COMPASSIONATE.” This verse is called the Basmala, or the Tasmiyyah, and it is printed at the top of every single Surah in the Qur’an, save just one.

An Indonesian youngster reads the Qur’an with some help from his cat. Photo by Maizal Chaniago. Is this a historical photo, teaching us about the roots of the Qur’an? Not really. But it’s an adorable picture. Abu Hurayra would have been proud.

Other revelations considered to be the last, or among the last verses ever revealed to Muhammad exhibit a similar quality of finality, and universality. A verse toward the end of Surat al-Baqarah, the lengthy second surah, tells believers, “Beware of a Day when you will be returned to God: every soul will be paid in full for what it has earned, and no one will be wronged” (2:281). Another late revelation tells believers that if they are ostracized, they should say, “God suffices me. There is no god but He. In Him do I trust, and He is the Lord of the mighty Throne” (9:129). In what is generally understood as the last complete surah ever revealed to Muhammad – a surah revealed during the conquest of Mecca, there is a clear tone of victory. Surat al-Nasr, or “Help,” the Qur’an’s 110th surah, says, “When God’s help comes and He opens up your way [Prophet], when you see people embracing God’s faith in crowds, celebrate the praise of your Lord and ask His forgiveness: He is always ready to accept repentance” (110:1-3).20

There is, then, an outline of the long and decorated career of Muhammad that zigzags through the Qur’an’s many verses. From being the frightened recipient of divine words, huddled beneath his cloak, Muhammad, in the final revelations, is triumphant, offering verses again and again that seem to contain the pith of Islamic teaching in just a sentence or two.

So, to move forward, one of the ways to understand the Qur’an is something we just did – to study it as a sequence of revelations that Muhammad had between 610 and 632. Muhammad’s wife Aisha, once asked about Muhammad’s character, replies in a hadith, “Do you not read the Quran?. . .His character was the Quran.”21 Indeed, as we’ve seen so far and will continue to see, the personality of the Prophet, as evident in the early biographies of Ibn Ishaq and al-Waqidi, is evident in the pages of the Qur’an. The Qur’anic voice is wise, practical, patient, persuasive, and eloquent, precisely as we see Muhammad in so many ninth century biographies. It is important to understand some of the biographical and historical origins of the many verses and surahs of the Qur’an, hence our six hours of programs on the life of the Prophet leading up to this one.

This is the point in the episode at which I need to make some organizational decisions. The longer surahs of the Qur’an do not offer sustained arguments or narratives that I can go through and summarize as cohesive units. The shorter surahs are frequently single revelations, each incandescent and rich with meaning, but also, each its own theological and philosophical statement. You’ve just heard a general introduction to the Qur’an’s form and contents, and then learned about some of the very earliest, and very latest revelations that Muhammad had. Rather than continuing to tack Qur’anic verses onto the timeline of Muhammad’s life, and because this is an introductory episode, I think the best way for us to continue will be to hear an overview of some of the major topics recurrently covered in the Qur’an, along with representative verses on each major topic.

The major topics to be covered in the remainder of this episode will be what the Qur’an says about God, creation, humanity, and Jannah and Jahannam, or heaven and hell. These are among the most important subjects in the book, and we certainly won’t comb through each verse on each topic. Additionally, we will once again have two more programs on the Qur’an after this one, the first on Islamic law in the Qur’an and the second on the Qur’an’s theological heritage. While we will only hear a small sampling of Qur’anic verses in the remainder of this episode, again on God, creation, humanity, and heaven and hell, by the time we’re through, you should have a basic sense of some of the book’s most important teachings. So let’s begin by exploring the ways in which the Qur’an describes, and does not describe God. [music]

The Qur’anic Descriptions of, and Passages about God

There is a wondrousness in the way that the Qur’an describes God that is well established by the end of the Qur’an’s second surah. The Qur’an, as mentioned earlier, often cites signs or proofs, or in Arabic, ayat, as overwhelming evidence of God’s presence. The Qur’an, at some of its most soaring moments, simply cites some of the miracles of nature as evidence for the majesty of God, as in these passages from Surat al-Baqarah, or “The Cow,” again the Qur’an’s second surah:Marvelous Creator of the heavens and the earth!

When He decrees a matter, He merely says to it: “Be!” and it is.

The ignorant say, “If only God would speak to us! If only a sign would descend upon us!”

This too was said by past generations, word for word. Their minds are much alike.

But We have made clear these signs to a people of firm faith. (2.117-18)

It is He Who made the earth a bed for you, the sky a canopy; Who causes water to descend from the sky with which he brings forth fruits as sustenance for you. Do not, therefore, set up any equals to God when you know better.

If you doubt what We revealed to Our servant, bring forth one sura like it. (2.22-4)

In the creation of the heavens and the earth,

In the cycle of night and day,

In ships that plough the sea, to mankind’s benefit,

In what God causes to descend from the sky of water,

Giving life to the earth, hitherto dead,

And peopling it with all manner of crawling creatures,

In varying the winds and clouds, which run their course

between sky and earth –

In these are signs for people who reflect. (2.164)22

That was the Tarif Khalidi translation, published by Penguin in 2008. What we hear in those passages, which are in both prose and verse in the original Arabic, are descriptions of the bounties and beauties of Earth as tangible evidence for divine creation. The surah asks why people are waiting around for a sign to believe when, right there in front of them, there is rain and changing winds, plants springing up from dead earth, and the great cadences of clouds and night and day, and ships sailing through far off seas.

These verses are striking within the annals of Abrahamic theology. Judaism and Christianity, and along with their silent partner, Platonism, have had a sometimes squeamish relationship with the material world. New Testament epistles often dismiss Earth as a grubby prelude to heaven, and with the exception of Psalm 65 and the erotic metaphors of the Song of Songs, the Tankah says very little about nature. For these reasons, celebratory passages about the Earth’s wondrousness in Surat al-Baqarah and other chapters are a unique part of Islamic history, having inspired the work of early Islamic science, as well as exegeses on the Qur’an centered on the natural sciences.23 If you come to Surat al-Baqarah, the second chapter of the Qur’an, as we are, fairly well versed in the Bible, the verses praising Earth as evidence of the divine are one of the surah’s most distinctive features.

The Qur’an, then, describes God as manifestly present within the wonders all around us. The tacit point in the passage you just heard is the Qur’an’s often-repeated assurances that “God has power over everything” (3:165, 3:189, 8:41, 11:4, 41:39) and “control of the heavens and earth belongs to God” (9:116, 42:39, 42:49, 57:2), and that whenever God wants something to happen, “He says only ‘Be,’ and it is” (2:117, 6:73, 16:40, 40:68), each of these phrases used numerous times throughout the book. The Qur’an calls God the wisest of all judges (95:8), and says that God, omnipresent and omniscient (2:115) is the force that makes people laugh, as well as weep (53:43).

Numerous surahs marvel on the infinite and otherwise indescribable wisdom of God. A verse in Surat al-An’am, the sixth surah, reads, “He has the keys to the unseen: no one knows them but Him. He knows all that is in the land and sea. No leaf falls without His knowledge, nor is there a single grain in the darkness of the earth, or anything, fresh or withered, that is not written in a clear Record” (6:59).24 This divine knowledge, of course, extends to the sphere of human activity and the deeds of every person (9:94, 9:105), and a very frequently repeated epithet is “Him who knows what is seen and unseen” (9:105, 13:9, 32:6, 39:46, 59:22, 62:8, 64:18) and elsewhere, “God knows all that is hidden in the heavens and earth; he knows the thoughts contained in the heart” (35:38, 49:18). Finally, in a famous description, the Qur’an calls God “the First and the Last; the Outer and the Inner; He who has knowledge of all things” (57:3). In summation, then omnipotence, omnipresence, and omniscience, are qualities thoroughly applied to God throughout the Qur’an. In what is likely the single most well-known verse of the entire Qur’an, Ayat al-Kursi, or “The Throne Verse,” adorning thousands of mosques and homes all over the world, the Qur’an states,

God, there is not god but He, the Living, the Self-Subsisting. Neither slumber overtakes Him nor sleep. Unto Him belongs whatsoever is in the heavens and whatsoever is on the earth. Who is there who may intercede with him save by His leave? He knows that which is before them and that which is behind them. And they encompass nothing of His Knowledge, save what He wills. His pedestal embraces the heavens and the earth. Protecting them tires Him not, and He is. . .Exalted, the Magnificent. (2:255)25

That was from the HarperOne Study Quran translation, published in 2015. In hearing these verses and epithets, it’s important to pause for a moment here, and emphasize that if the entire Qur’an has a main point, that point is the stupendous oneness and grandeur of God. That’s the core of the book. It is an inspirational book, offering readers an anchor of reassurance that beneficent protector who is present on the earth, in the stars, and in everything around us. The Qur’an covers many topics – we’re only an hour into the seven or so that we’ll spend on it in our podcast – but again, the heart of the book is its many revelations about the oneness, omnipotence, omniscience, and omnipresence of God.

While the Qur’an often describes what God is, the Qur’an also describes what God is not. Surat Annisa, the fourth surah, proclaims that “Jesus, son of Mary, was nothing more than a messenger of God, His word directed to Mary, and a spirit from Him. So believe in God and His messengers and do not speak of a ‘Trinity’. . .God is only one God, He is far above having a son” (4:171). Elsewhere, considering Christianity and perhaps other religions, the Qur’an states that God has neither a wife, nor a son (72:3), and in one of the final surahs, “He begot no one nor was He begotten” (112:3). While the Qur’an’s insistence that God has no son is at odds with Christian doctrine for extremely obvious reasons, Christianity has no issue with the Qur’an’s similar insistence that God has no daughters. The Qur’an describes the pagan Arabian goddesses “al-Lat and al-‘Uzza, and the third, other one, Manat” (53:19), and the book remarks with incredulity at numerous junctures that pagan Arabs envision God having only daughters while they themselves (the patriarchal Arabs, in other words) place stock in having sons (16:57, 17:40, 43:16, 52:39, 53:21). God, in the Qur’an, then, is emphatically singular, having neither partners, nor children.

In addition to being sovereign, and singular, the Qur’anic voice describes God as fundamentally just, and good. The Qur’an states that “God does not will injustice for His creatures” (3.108), and that “He does not wrong anyone by as much as the weight of a speck of dust: He doubles any good deed” (4.40). Numerous other verses emphasize that God is never unjust (40.31, 22:10, 26:209, 40:31, 41:46, 50:29) perhaps culminating in an avowal in Surat al-Jathiyah, the 45th surah, that “God created the heavens and earth for a true purpose: to reward each soul according to its deeds. They will not be wronged” (45:22). The Qur’an’s view of Earth is of a place governed by an ultimate cosmic justice, with one verse emphasizing that God will weigh the deeds of believers down to the weight of a mustard seed on the day of judgement (21:47). Judgment day, and the administration of divine justice, are pervasive topics in the Qur’an, which emphasizes that God will mete out justice to all according to their deeds. Before we get to judgment day, or the end, so to speak, let’s actually go back to the beginning, and explore the basics of what the Qur’an has to say about God’s creation of the world, and creation of humanity. [music]

The Story of Creation in the Qur’an

The Qur’an’s cosmogony, or theory regarding the origin of the universe, is a creationist account of the beginning of things, similar to the one we find in the Book of Genesis. Perhaps most representatively, Surat al-Araf, the seventh surah, describes “God, who created the heavens and earth in six Days, then established Himself on the throne. . .He created the sun, moon, and stars to be subservient to his command; all creation and command belong to Him” (7:54). Other surahs also describe this same six-day creation, and also emphasize how God became sovereign over his creation after it took place (10:3, 25:59, 57:4), with another surah having a familiar image from Genesis: “He. . .created the heavens and the earth. . .and His throne was on water” (11:7). The longest account of creation in the Qur’an is in Surat Fussilat, the 41st surah, and this account describes the creation of the earth and heavens as subdivided into first two days, and then four days, and then two additional days. Surat Fussilat, whose title can be translated as “Made Clear,” states that God:created the earth in two days. . .He Who is Lord of the Worlds!. . .

Above the earth He erected towering mountains, and He blessed it, and appraised its provisions in four days, in equal measure to those who need them

Then he ascended to heaven, while yet smoke, and said to it and to the earth: ‘Come forth, willing or unwilling!’

And both responded: ‘We come willingly.’

Then he ordained seven heavens in two days, and inspired each heaven with its disposition.

And We adorned the lowest heaven with lanterns, and for protection. Such was the devising of the Almighty, All-Knowing. (41:9-12)26

That was the Penguin Tarif Khalidi translation. Elsewhere, the Qur’an tells us that God brings day from night, and night from day (22:61). Striking verses marvel at God’s creation of the sky and earth, and the livestock that serves humanity, and God’s creation of “other things you know nothing about” (16.8), emphasizing that the palpable world of human experience is only a small portion of the divine.

To repeat something that we learned earlier, the Qur’an doesn’t simply see the world as a drab stage on which the drama of human ethical behavior will be carried out. The Qur’an sees the world and universe as gorgeous, churning systems, full of life and color, that are themselves palpable proofs, or signs, or God’s presence. For instance, in Surat Fatir, or “The Creator,” the 35th surah, the Qur’an says, in the Oxford Haleem translation,

Praise be to God, Creator of the heavens and earth. . .It is God who sends forth the winds; they raise up the clouds. . .The two bodies of water are not alike – one is palatable, sweet, and pleasant to drink, the other salty and bitter – yet from each you eat fresh fish and extract ornaments to wear, and in each you see the ships ploughing their course. . .Have you. . .not seen how God sends water down from the sky and that We produce with it fruits of varied colours; that there are in the mountains layers of white and red of various hues, and jet black; that there are various colours among human beings, wild animals, and livestock, too? (35:1,9,12,27)

As you can see, there, as in earlier verses I quoted, the Qur’an’s creationism is part of its broader sense that the magnificence of the world is a sign of the oneness of God.

There is a repeated emphasis, in the Qur’an’s many accolades of the created universe, of the harmony that governs the environments that humans experience. The sun and moon, the book tells us, are beautiful in separate ways, and both help demarcate the orderly passage of time (10.5, 6:96). The falling meteorites (34:9), the constellations of the zodiac, visible to everyone to see (15:16), and the star Sirius (53:49) are all within the governance of God. So, too, are the many natural systems at work around us, including pollination (15:22), tornados (17:68), mountains, and rivers (16:15). And among all the creations of God described in the Qur’an, the Qur’an itself is often cited as a divine production. A rich verse of the book states that “If all the trees on earth were pens and all the seas, with seven more seas besides, [were ink,] still God’s words would not run out” (31:27). Revere the world, the Qur’an teaches its reader, but also, appreciate the Qur’an itself as a guide and index for the world and the many things in it.

The Creation of Humanity in the Qur’an

In the Qur’an, as in Judaism and Christianity, one of God’s many creations is humanity. Let’s discuss the Qur’an’s account of humanity’s creation. The Qur’an variously states that God created the first human from “dried clay formed from dark mud” (15:26; 6:2, 7:12, 17:61, 32:7), or from dust (3:59, 18:37, 22:5 35:11), and then from a drop of fluid (16:4, 18:37, 22:5, 23:13, 35:11, 36:77). The Qur’an frequently emphasizes that God didn’t just create the first humans, and then let biological life go on its way. The Qur’an tells us that God continues to be present in the ongoing creation of human life, following the initial creation. For instance, the book states that God “created you from dust, then from a drop of fluid, then from a tiny, clinging form, then He brought you forth as infants, then He allowed you to reach maturity” (40:67). The creation of humans in the Qur’an, then, is a continuously generative process, as God is part of the miraculous gestation of every person. Just as the Book of Genesis does, the Qur’an emphasizes that God created humanity as male and female (92:3), and in corresponding pairs (78:8). The surahs emphasize that from the union of male and female come not only children and grandchildren, but also unions between people that are characterized by “tranquility: He ordained love and kindness between you” (30:21). As with natural wonders like rain and growing plants, the Qur’an frequently cites the biological perpetuation of human life and the everyday miracles of love and reproduction as further marvelous signs of God’s presence, and God’s beneficence.The Qur’an, then, contains these general accounts of humanity’s creation – that we were made from clay or dust into pairs to produce more of us, and that God is part of every epoch of humanity’s generation, past, present, and future. But the Qur’an also contains the familiar, mostly Biblical account of Adam and creation. Surat al-Baqarah, the Qur’an’s second surah, tells us, in the Dawood translation,

And when we said to the angels: ‘Prostrate yourselves before Adam,’ they all prostrated themselves except Satan, who in his pride refused and became an unbeliever.

We said: ‘Adam, dwell with your spouse in Paradise and both of you eat of its fruits to your hearts’ content whatever you will. But never approach this tree or you shall both become transgressors.’

But Satan lured them thence and brought about their banishment. ‘Get ye down,’ We said, ‘and be enemies to each other. The earth will provide for you an abode and comforts for a time.’ (2:34-6)

What follows in the second surah of the Qur’an, and many other surahs, is an account of how God offered prophetic messages to humanity from Adam to Moses on down to Muhammad himself. I want to talk about the Abrahamic and Arabian heritage of the Qur’an extensively in the third program in this trio of episodes on the Qur’an, so let’s stick with the Qur’an itself for the moment.

An illuminated Qur’an from the Ottoman Empire, dated between 1848 and 1849, with fifteen lines per page, and a staggering quantity of flowers and leaves. Ottoman readers liked their illuminated manuscripts to be particularly luminous.

The short answer is somewhere in between. First of all, the Qur’an, just as it venerates the many miracles of the natural world, also cites the multiplicity of humanity as a sign of God’s sovereignty – as the Qur’anic voice puts it, “And one of His signs is. . .the diversity of your languages and colours” (30:22). Multiform as humanity is, though, the Qur’an also at one point emphasizes that people are just one small part of the cosmos. The book emphasizes that “The creation of the heavens and earth is greater by far than the creation of mankind, though most people do not know it” (40:57), quite a nice verse, in my opinion, that moves away from the homocentricity so common in salvific religions. The Qur’an also describes humanity as neither good nor evil, instead stating that “Man was truly created anxious: he is fretful when misfortune touches him, but tight-fisted when good fortune comes his way” (70:19-21). A different surah offers a more sanguine verse about human nature, saying, “So [Prophet] as a man of pure faith, stand firm and true in your devotion to the religion. This is the natural disposition God instilled in mankind – there is no altering God’s creation” (30:30). Elsewhere, though, the Qur’an proclaims “We created man in the finest state then reduced him to the lowest of the low” (95:4-5), and at several junctures, the book, calls humanity “surely. . .ungrateful” (14:34, 22:66, 43:15), spending large portions of numerous surahs (7, 11, 26, 37, 54) lamenting that in earlier history, people ignored the revelations of God’s prophets. The Qur’an’s sense of human nature, then, largely comes from and is consonant with Christian and Jewish traditions – we were created by a gracious and benevolent deity and given copious furnishings on earth to make us comfortable, and yet in spite of the palpable evidence around us, we all too often refuse to believe in God or respect the validity of prophetic messages.

So that takes us through two massively important subjects in the Qur’an – its descriptions of God and divine nature, and then its account of how Earth was created, and the nature of humanity. While I hope I’ve given you a sense of what the Qur’an says on these central topics, I also hope that the plentiful quotes you’ve heard from the Qur’an have offered some impression of what the book sounds like. Its voice is patient, measured, and pedagogical. Its signs, or ayat, whether rain or oceans or human gestation, are presented as self-evident miracles and evidence of the omnipresent ministrations of God. While the book’s voice is calm and calculated, the Qur’an’s sentences unfold in nearly constant structural variety, switching from imperatives to declaratives to interrogatives. The Qur’anic voice sometimes speaks in the third person, sometimes the royal we, and sometimes the first person. Beneath the rustle of the book’s continuously evolving language, however, are the consistent drumbeats of its main points – there is only one, wonderful God, Muhammad is his prophet, and the world and human life alike are full of signs of that God’s sovereignty.

Let’s move on, now, to a different topic. This topic is another central subject in the Qur’an – the subject of salvation. Islam is, like Christianity before it, an exclusive monotheism and a salvific religion, and thus one of the Qur’an’s principal teachings is that believers will enjoy the rewards of Jannah, or heaven, and disbelievers will suffer the punishments of Jahannam, or hell. Hearing some of the great many Qur’anic verses on these subjects, along with its descriptions of judgment day and resurrection, should give you more of a sense of what the Qur’anic voice sounds like, along with its teachings on salvation and eschatology, or the end of times. [music]

Heaven as the Qur’an Describes It

Heaven, in the Qur’an, is described similarly to the way that it was being described in Jewish and Christian apocalyptic literature during Late Antiquity. It is a vast place, described as having seven levels (23:17), and envisioned as having “rivers of water forever pure, rivers of milk forever fresh, rivers of wine, a delight for those who drink, rivers of honey clarified and pure, [all] flow in it; there they will find fruit of every kind; and they will find forgiveness from their Lord” (47:15). Muhammad himself is understood to have journeyed there, and at the apex of heaven, Muhammad saw the angel Gabriel, as the book states, “A second time he saw him: by the lote tree beyond which none may pass near the Garden of Restfulness, when the tree was covered in nameless [splendour]” (53:13-4). While passages about the seven levels of heaven, its four rivers, and the summit of heaven are rare and memorable descriptions in the Qur’an, much more commonly, the book describes heaven as a garden, as Jannah, the Arabic word for heaven, means “garden.”The Qur’an describes the garden of heaven with frequently repeated epithets. Two representative descriptions from the second and third surahs are as follows. The second surah states, “[Prophet], give those who believe and do good the news that they will have Gardens graced with flowing streams. . .They will have pure spouses and there they will stay” (2:25). And Surat Aali-Imran, the third surah, says, “Their Lord will give those who are mindful of God Gardens graced with flowing streams, where they will stay with pure spouses and God’s good pleasure” (3:15). The phrase “Gardens graced with flowing streams” is repeated very often in the Qur’an – 32 times, and perhaps the richest description of heaven in the Qur’an is in Surat Arrahman, the 55th surah. Let’s hear Surat Arrahman on the subject of heaven, in the Penguin Tarif Khalidi translation.

In it are two running springs. . .In it are, of every fruit, two kinds. . .[Believers] recline on couches, their mattresses of brocade, / With the fruit of the. . .Garden. . .close to hand. . .Therein are maidens, chaste of glance, / Undefiled before them by humans or Jinn. . .As if they were rubies or coral. . .Below these. . .are two other Gardens. . .Over-shadowing. . .In them are two fountains, ever gushing. . .In these two are fruits, palms and pomegranates. . .In them are maidens, virtuous and beautiful. . .Dark-eyed, confined to pavilions. . .Undefiled before them by humans or Jinn. . .They recline on green cushions, and sumptuous rugs. (55:46-76)27

The next surah contains a similar description of paradise. Let’s hear that one, too, in its entirety, and then we can discuss heaven in the Qur’an for a moment. This is a second sustained description of heaven, and the N.J. Dawood translation of Surat al-Waqi’ah, the 56th surah. Surat al-Waqi’ah says that the foremost of the believers

shall be brought near to their Lord in the Gardens of Delight. . .They shall recline on jeweled couches face to face, and there shall wait on them immortal youths with bowls and ewers and a cup of purest wine (that will neither pain their heads nor take away their reason); with fruits of their own choice and flesh of fowls that they relish. And theirs shall be dark-eyed houris, chaste as virgin pearls: a [reward] for what they did.

Therein they shall hear no idle talk, no sinful speech, but only the greeting, ‘Peace! Peace!’

[Others] shall recline on couches raised on high in the shade of thornless sidr [trees] and clusters of [acacia]; amidst gushing waters and abundant fruits, never-ending, unforbidden.

We created the houris and made them virgins, loving companions for those on the right hand. (56:11-38)28

So those should give you a sense of what the Qur’an says about heaven, and what believers can expect to find there.

If we set Qur’anic descriptions of heaven alongside Biblical ones, we are confronted by a very simple fact. The Bible doesn’t ever describe heaven to any great extent. In apocryphal apocalyptic literature, like the Enochian corpus and the Apocalypse of Paul, we read visionary tours of heaven and hell, in which heaven is seen as a pagoda-like place with many tiers and various rivers of milk and honey such as we catch glimpses of in the Qur’an. The Bible itself, though, to be very clear, says nothing about heaven other than that it is the abode of God, the Biblical doctrine of salvation more often being described as a corporeal resurrection on Earth, from the Pentateuch all the way to Revelation. Thus, one of the reasons the Qur’anic descriptions of heaven are so memorable is that the Qur’an is the only piece of canonical Abrahamic scripture to describe heaven with any specificity.

Heaven in the Qur’an is a place of water and plentitude, tasty fruits and comfortable sitting places, truth and genuine conversation, shade and plants, and attractive houris for companionship, women that, in the Oxford Haleem translation, are described as “maidens restraining their glances, untouched before by man or jinn” (55:56). Needless to say, the notion that sensual pleasure would be a part of heaven would have made Saint Augustine and Saint Jerome’s heads explode, but the Qur’an’s numerous references to chaste and alluring female companions as part of the heavenly rewards of the pious believer are still important parts of Islamic tradition. The Qur’an, then, describes Heaven in several sustained passages as a lush, comfortable, satisfying place where believers who have braved the challenges and privations of a sometimes harsh world are rewarded for being honest, trustworthy, praying and following the Qur’an’s framework of rules, and above all, believing in God.

Hell as the Qur’an Describes It

Heaven, however, is of course only one of two possible posthumous destinations for humans in the Qur’an, the second destination being a rather different one. The Qur’an mentions hell hundreds of times, most often briefly, as the destination of unbelievers in one of several epithets, most often calling it nar, or “fire.” The proper noun for hell in the Qur’an, Jahannam, comes from the Hebrew word Gehenna, or Ge Hinnom, the name of a valley west and southwest of Jerusalem associated with idolatrous practices since the Preexilic period, which, by the time the Christian Synoptic Gospels were written in the mid to late first century, was a general term for a place of eternal punishment in Judaism and Christianity. While hell in the Qur’an is sometimes called “fire,” and sometimes Jahannam, it is also commonly shorthanded as jahim, or “blazing fire.” Most often in the Qur’an, hell is mentioned briefly as a grim alternative to believing in God and adhering to the truths of the surahs.

A 9th-century Qur’an written in the Kufic Arabic script in the Reza Abbasi Museum in Tehran. This is what a small Qur’an might look like during the early decades of the Islamic Golden Age.

The Qur’an states that “Hell is the promised place for all [the wicked], with seven gates, each gate having its allotted share of them” (15:43). In the Qur’an’s hell, as a surah explains, “Everyone is assigned a rank according to their deeds” (6:132). Hell is also, somehow, tantalizingly close to paradise, such that, as the book puts it, “The people of the Fire will call to the people of Paradise, ‘Give us some water, or any of the sustenance God has granted you!’” (7:50). The Qur’an also tells us that within hell, there is a tree – a tree that is part of the punishment of the damned. A surah tells us, this time in the Dawood translation, “[T]hey shall dwell amidst scorching winds and seething water: in the shade of pitch-black smoke, neither cool nor refreshing. For they have lived in comfort and persisted in the heinous sin. . .[A]s for you who err and disbelieve, you shall eat from the Zaqqum tree and fill your bellies with its fruit. You shall drink scalding water: yet you shall drink it as the thirsty camel drinks” (56:42-46, 51-5). Elsewhere on the subject of this tree, the Qur’an states “The tree of Zaqqum will be [the] food for the sinners: [hot] as molten metal, it boils in their bellies like seething water” (44:43-6).

And while the Qur’an has a small handful of passages illustrating some of the specifics of the hell and how it works, most often, hell is described as a ferocious blaze. The Qur’anic voice explains that, “We adorned the lower sky with lanterns, and made them to be volleys against the demons, for whom We have readied the torment of the Blaze. . .And to those who blasphemed their Lord there awaits the torment of hell – and a wretched destiny it is!. . .When hurled therein, they hear it sighing as it boils over. It almost seethes with rage whenever a batch is thrown in. Its watchmen will ask them: ‘Did no warner come to you?’ And they shall answer: ‘Yes, a warner did come, but we cried lies and said that God had sent down nothing’” (67:5-9). So that should give you an idea of how the Qur’an describes hell – the scorching, ruthless dungeon of all those who don’t believe.

Horrific as hell is in the Qur’an, it is most often presented in double passages that also illustrate the joys and comforts of heaven. Qur’anic depictions of hell, to Muslims of Muhammad’s generation all the way up to our own, are understood as descriptions of a very real and dreadful place. At the same time, depictions of hell juxtaposed with descriptions of heaven create a powerful rhetorical effect in the Qur’an. Hell might be a place of scalding fire and choking smoke, but heaven, to dutiful believers, is paradise beyond compare, attainable by acknowledging the validity of the Qur’anic message and adhering to the precepts of Islam. Hearing the vivid comparisons between Jannah and Jahannam that fill so many Qur’anic surahs, comparisons with detailed, multisensory descriptions of each place, is a powerful part of reading the book or hearing it recited.

So, we’ve just heard some of the principal Qur’anic passages that describe heaven and hell, the posthumous destinations of the pious and the impious, respectively. While the Qur’an shares the earlier Abrahamic religions’ doctrines of individual posthumous salvation, the Qur’an also shares Judaism and Christianity’s belief in an approaching judgment day. This doctrine is significantly different in Sunnism and Shiism, and we can talk about that more on down the road. For now, let’s leaf through Qur’an just a bit more in this introductory episode, and learn about how the Qur’an describes the last judgment. [music]

Judgment Day as Described in the Qur’an

Apocalyptic literature is always a spectacular genre. From the eschatological prophecies of Jeremiah, to Zoroastrian writings on the frashokereti, to the Christian book of Revelation, to Late Antique Christian and Jewish writings about the end of the world, apocalyptic writings are full of memorable fireworks. With the world rumbling to an end, and in Zoroastrianism and Christianity, an actual pitched battle between good and evil, there is a lot for the apocalyptic prophet to describe and set down, and the Qur’an’s apocalyptic visions are as striking and powerful as any. Yawm al-qiyamah, or the “Day of Resurrection,” is mentioned many times in the surahs, as both a promise and a threat. Let’s hear some of the Qur’an’s most famous and representative descriptions of Judgment Day, starting with one in Surat al-Haqqah, the 69th surah of the Qur’an:[W]hen a single blast is blown in the trumpet and the earth and mountains are borne away and ground up in a single grinding, on that Day the Event shall befall, the sky shall be rent asunder; for that Day it shall be frail. And the angels shall be at its sides; that Day eight shall carry the Throne of [your] Lord above them. That Day you shall be exposed; no secret of yours shall be hidden. As for one who is given his book in his right hand, he will say, “Here, read my book. Truly I knew for certain that I would meet my reckoning.” So he shall enjoy a life contenting, in a lofty Garden with low-hanging clusters. . .As for one who is given his book in his left hand, he will say, “Would that I had not been given my book. And did not know of my reckoning”. . .Take him and shackle him. Then cast him in Hellfire. (69:13-23,25-6,30-1)

That was the HarperOne Study Quran translation. What we just heard typifies Qur’anic apocalypticism more generally.29 The world comes to an end. Each person bears a book of their deeds, sometimes symbolically carried in a right or left hand, and this book of deeds is read, after which the person is saved or damned. The many descriptions of Judgment Day in the Qur’an have this general outline. The end of the world is elsewhere described vividly, as when the book imagines the sun rolling up, stars falling and mountains exploding, seas burning and even heaven and hell themselves coming close to earth (81:1-14). A different Surah foretells how the sky will be torn to pieces, the mountains will be pulverized into sand, and the hair of children will turn gray (73:14-18). Qur’anic descriptions of the earth’s end focus in particular on the skies torn apart (55:37, 69:16, 73:18, 77:9), and the sky becoming red hot (70:8, 55:37), and the earth quaking and being smashed (56:4, 50:44) or outright leveled (84:3), and finally the mountains becoming as soft as tufts of wool (70:9, 101:5), or vanishing (78:20), or shattering (56:5). At one point, the Qur’an describes “the peoples of Gog and Magog. . .let loose [to] swarm swiftly from every highland” (21:96).

The Qur’an also depicts Judgment Day as a day of physical resurrection, when the dead, following the blast of the divine trumpet, will be reknit from their remains into their physical forms (17:98-9, 39:67-9, 79:10-14, 80:22). This miracle – of God bringing the dead back to life, is only part of a greater resurrection, as God says, “We shall reproduce creation just as We produced it the first time” (21:104). Jesus, the Qur’an tells us, will be front and center at some of the miracles of Judgment Day. As an early surah puts it, “on the Day of Resurrection [Jesus] will be a witness” (4:159), and elsewhere (3:55), Jesus is depicted as destined for special esteem on Judgment Day. The Qur’an has dozens and dozens of mentions of Judgment Day and resurrection, and when we look at all of them together, we can make a few generalizations.

The Qur’an describes Judgment Day as a calling forth and a convocation – an inescapable moment at which all have their deeds laid bare before God. There is tumult and terror on Judgment Day – the end, as we learned a moment ago, involves the skies being ripped to pieces and the mountains smashed to dust. However, there is also a careful order and almost tenderness within the more general demolition of the apocalypse. In an apocalyptic vision we heard toward the beginning of this episode, the sun is rolled up and the seas boil, but at the same time, animals are herded, humanity is taxonomized, and divine justice is carried out. The Qur’an emphasizes that judgment is an affair as meticulous as it is final. Two famous verses bid the heavenly angels to “gather together those who did wrong, and others like them, as well as whatever they worshipped beside God, lead them all to the path of Hell, and halt them for questioning” (37:22-4). This “path of hell” or sirat al-jahim, later in Islamic eschatology, started being envisioned as a bridge that all humans had to cross – a thin, perilous bridge that hung over hell, but that led to heaven.30

And speaking of extraquranic materials related to Judgment Day, like the Dajjal, the Sufyani, and most importantly, the Mahdi, many doctrines were later appended to the Qur’an’s core story of the end of the world and the administration of Divine Justice. But, as this is an introductory overview of the Qur’an, and not all of Islamic history, I think we’ve likely heard enough illustrative quotations for one program, both short and long. In the remainder of this show, I’d like to do two things. First, I’d like for you to hear some Qur’anic recitations, in Arabic, of some of the book’s most beautiful and beloved verses. Tajweed, or the art of reciting the Qur’an, is one of Islam’s most beloved traditions, and it would be a shame for you to walk away from even an introductory episode on the Qur’an without hearing it the way it is intended to be heard. After we hear some of the book’s most cherished verses in Arabic, I’m going to wrap things up by talking just a bit about scholarly issues surrounding some of the things we’ve discussed today – issues related to Qur’anic manuscripts, how we date the text, and how Islamic Studies scholarship now currently understands the formation of the Qur’an. Let’s begin by hearing some recitations. [music]

Some Iconic Qur’anic Passages, with Tajweed

At the outset of this episode, I mentioned that one of the things that makes the Qur’an unique is that in liturgical or religious settings in Islam, the Qur’an is always recited in Arabic. If a devout Muslim lady from Turkey, and a pious Indonesian Sunni and an Ibadi grandma from Oman and a devout Uzbek grandpa and practicing Shia from Iran are in the same room, they all know the same Arabic Qur’an. Because the language of the Qur’an is so globally ubiquitous, I thought I’d take advantage of the podcast form to have my season’s editor read some of the Qur’an’s most absolutely famous verses in proper Qur’anic Arabic while I translate them into English.We’ve already heard some famous verses in this program, and we even heard Surat al-Fatihah, or “The Opening” – the Qur’an’s first lines – at the opening of this show in Arabic. Let’s hear some more of the Qur’an in Arabic. I want to go, line by line, through part of Surat Annur, or “Light,” the 24th surah of the Qur’an. We’re going to hear a verse known in Arabic as ayat an-nur, or “The Light Verse,” one of the most cherished verses in the whole book. This will be a phrase-by-phrase translation with Arabic first, and then the HarperOne Study Qur’an translation.

ٱللَّهُ نُورُ ٱلسَّمَـٰوَٰتِ وَٱلْأَرْضِ ۚ

God is the Light of the heavens and the earth.

مَثَلُ نُورِهِۦ كَمِشْكَوٰةٍۢ فِيهَا مِصْبَاحٌ

The parable of His Light is a niche, wherein is a lamp.

ۖ ٱلْمِصْبَاحُ فِى زُجَاجَةٍ ۖ

The lamp is in a glass.

ٱلزُّجَاجَةُ كَأَنَّهَا كَوْكَبٌۭ دُرِّىٌّۭ يُوقَدُ مِن شَجَرَةٍۢ مُّبَـٰرَكَةٍۢ

The glass is as a shining star kindled from a blessed. . .tree,

زَيْتُونَةٍۢ لَّا شَرْقِيَّةٍۢ وَلَا غَرْبِيَّةٍۢ يَكَادُ زَيْتُهَا يُضِىٓءُ

[an olive] neither of the East nor of the West. Its oil would well-nigh shine forth,

وَلَوْ لَمْ تَمْسَسْهُ نَارٌۭ ۚ

even if no fire had touched it.

نُّورٌ عَلَىٰ نُورٍۢ

Light upon light.

ۗ يَهْدِى ٱللَّهُ لِنُورِهِۦ مَن يَشَآءُ ۚ

God guides unto His Light whomsoever He will,

وَيَضْرِبُ ٱللَّهُ ٱلْأَمْثَـٰلَ لِلنَّاسِ

and God sets forth parables for mankind,

وَٱللَّهُ بِكُلِّ شَىْءٍ عَلِيمٌۭ

and God is Knower of all things. (24:35)

Even without knowing any Arabic, you can hear some of the universal tools of poetry at work there, like assonance, or vowel repetition, in al-lahu nuru, in mathalu nurihi, and consonance, as in al-lahu al-amthala lilnnasi wal-lahu bikulli, together with wonderful parallel constructions – mis’bahun, al-mis’bahu; zujajatin, al-zujajatu; and most famously, nurun ala noor or “Light upon light.” Anyway, it’s one thing to understand that the culture into which the Qur’an emerged was one steeped in marvelous oral poetry, but I hope that by hearing some of this you can get an idea of what a formidable force the Qur’an is when recited. So that again was the famous lamp verse.

Let’s hear another verse from just a moment later in the same surah. One of the things that the Qur’an very often does is to compare the misguided notions of disbelievers with the correct notions of believers, juxtaposing the foolishness and ill-fatedness of the former with the wisdom and blessedness of the latter. The following additional verse for Surat Annur, or “The Light,” again the Qur’an’s 24th chapter, describes the falseness of disbelief with a familiar metaphor. Here it is, with the translation again from the HarperOne Study Quran.

وَٱلَّذِينَ كَفَرُوٓا۟

As for those who disbelieve,

أَعْمَـٰلُهُمْ كَسَرَابٍۭ بِقِيعَةٍۢ يَحْسَبُهُ ٱلظَّمْـَٔانُ مَآءً

their deeds are like a mirage upon a desert plain which a thirsty man supposes is water,

حَتَّىٰٓ إِذَا جَآءَهُۥ لَمْ يَجِدْهُ شَيْـًۭٔا

[until] when he comes upon it, he does not find it to be anything.

وَوَجَدَ ٱللَّهَ عِندَهُۥ

but finds God there.

فَوَفَّىٰهُ حِسَابَهُۥ ۗ وَٱللَّهُ سَرِيعُ ٱلْحِسَابِ

He will then pay him his reckoning in full, and God is swift in reckoning. (24:39)

The metaphor here is as old as humanity – the falseness of a mirage, but the assonance in the original Arabic is as incredible as it is memorable, as in al-dhamanu maan hatta idha jaahu lam yajid’hu. In earlier episodes of Literature and History, in programs on Hesiod and Homer, we learned just how much mnemonic technology there is in oral poetry – how many tools and tricks exist within it to help bards with memorization and recitation, and to engage the ear and imagination of the listener. The Qur’an, both read and recited today, is a bridge between the ancient past and the present of human language, its various qira’at, or different forms of recitation, each having countless ties to the world in which the Prophet Muhammad lived and worked.

Speaking of Muhammad, and to come full circle, let’s go back to Surat al-Alaq, or “The Clinging Form,” the Qur’an’s 96th surah, and hear what is almost always considered to be the first words of the Qur’an ever revealed to the Prophet. In the cave of Hira, where Muhammad was praying and contemplating in the year 610 CE, he heard these words,

ٱقْرَأْ بِٱسْمِ رَبِّكَ ٱلَّذِى خَلَقَ

Read! In the name of your Lord who created:

خَلَقَ ٱلْإِنسَـٰنَ مِنْ عَلَقٍ

He created man from a clinging form.

ٱقْرَأْ وَرَبُّكَ ٱلْأَكْرَمُ

Read! Your Lord is the Most Bountiful One

ٱلَّذِى عَلَّمَ بِٱلْقَلَمِwho taught by the pen,

عَلَّمَ ٱلْإِنسَـٰنَ مَا لَمْ يَعْلَمْ

who taught man what he did not know. (96:1-5)

These six short verses illustrate much of what was to come in the language of Muhammad’s later revelations. There are rhymes, like khalaqa and alaqin, and line ends that use consonance – al-akramu, bil-qalami, and ya’lam. Line endings become line beginnings, as in khalaqa and khalaqa, and alladhi allama, allama al-insana. To be clear, the Qur’an emphasizes several times that it is not poetry. The Qur’anic voice states that “We have not taught the Prophet poetry. . .This is a revelation,” and in another surah, that “this [Qur’an] is. . .not the word of a poet” (69:40-1). It’s important to remember that distinction when learning about, and discussing the Qur’an, but at the same time, some literary terms are still useful in order to discuss some of the features of Qur’anic language, as we’ve been doing over the past few minutes.