Episode 122: The Early Abbasid Caliphate

From 750-861, a dynasty of ten caliphs seated in modern-day Iraq ruled one of history’s largest empires. The territory they lost and won, the wars they fought, and the cultural renaissance that they helped usher in all had far reaching impacts on world history.

Episode 122: The Early Abbasid Caliphate

Gold Sponsors

David Love

Andy Olson

Andy Qualls

Bill Harris

Christophe Mandy

Jeremy Hanks

John David Giese

KelleyGr

Laurent Callot

Maddao

ml cohen

Nate Stevens

Olga Gologan

Steve baldwin

Silver Sponsors

Lauris van Rijn

Alexander D Silver

Andreu Andreu i Andreu

Basak Balkan

Boaz Munro

Charlie Wilson

David

Devri K Owen

Ellen Ivens

Evasive Species

Hannah

Jennifer Deegan

John Weretka

Jonathan Thomas

Julius Barbanel

Michael Sanchez

Mike Roach

rebye

Top Clean

Sponsors

Katherine Proctor

Carl-Henrik Naucler

Joseph Maltby

Stephen Connelly

Chris Guest

Sander

Matt Edwards

A Chowdhury

A. Jesse Jiryu Davis

Aaron Burda

Abdul the Magnificent

Aksel Gundersen Kolsung

Alex Metricarti

Andrew Dunn

Anthony Tumbarello

Ariela Kilinsky

Arvind Subramanian

Bendta Schroeder

Benjamin Bartemes

Berta Kienle

Brian Conn

Carl Silva

Cat Peterson

Charles Hayes

Chief Brody

Chris Auriemma

Chris Brademeyer

Chris Ritter

Chris Tanzola

Christopher Centamore

Chuck

Cody Moore

Daniel Stipe

David Macher

David Stewart

Denim Wizard

Dominic Klyve

Doug Sovde

Earl Killian

Eliza Turner

Elizabeth Lowe

Eric

Eric McDowell

Erik Trewitt

Evan Flecker

Francine

Friederike Otto

FuzzyKittens

Garlonga

Glenn McQuaig

J.W. Uijting

James McGee

Jason Davidoff

Jay Cassidy

JD Mal

Jillyp

Joan Harrington

joanna jansen

John Barch

John Sanchez

John-Daniel Encel

Jonah Newman

Jonathan Whitmore

Jonathon Lance

Joran Tibor

Joseph Flynn

Joshua Edson

Joshua Hardy

Kathrin Lichtenberg

Kathy Chapman

Kyle Pustola

Lat Resnik

Laura Ormsby

Le Tran-Thi

Leonardo Betzler

Lori Gum

Maria Anna Karga

Mark Griggs

MarkV

Martin Schleuse

Matt Hamblen

Maury K Kemper

Michael

Mike Beard

Mike Sharland

Mike White

Morten Rasmussen

Mr Jim

Nassef Perdomo

Neil Patten

noah brody

Oli Pate

Oliver

Paul Camp

Peter Goldstein

pfschmywngzt

purden@verizon.met

Richard Greydanus

Riley Bahre

Robert Auers

Robert Brucato

De Sulis Minerva

Rosa

Ryan Booth

Ryan Goodrich

Ryan Shaffer

Ryan Walsh

Ryan Walsh

Shaun

Shaun Walbridge

Sherry B

Sonya Andrews

stacy steiner

Steve Grieder

Steven Laden

Stijn van Dooren

Stuart Sherman

SUSAN ANGLES

susan butterick

Susan Hall

Ted Humphrey

The Curator

Thomas Bergman

Thomas Leech

Thomas Liekens

Thomas Skousen

Thomas Woolverton

Tim Rosolino

Tod Hostetler

Tom Wilson

Torakoro

Trey Allen

Troy

Valentina Tondato Da Ruos

vika

Vincent Vandeven

William Coughlin

Xylem

Zak Gillman

Between 750 and 861, the golden age of Islamic history began. From Tunisia to Kyrgyzstan, a dynasty of ten caliphs held sway over many of the most densely inhabited regions of Earth. The city of Baghdad was founded, along with its House of Wisdom, one of history’s most famous libraries and academies. The caliph al-Ma’mun launched a major translation movement to bring knowledge of Greek philosophy, medicine, and science into Arabic texts. Literature flourished in prose and verse, under the pens of writers still widely read today. Society under the Abbasid caliphs was sprawling and diverse, with the Umayyad Arab hegemony slowly giving way to a more heterogeneous patrician and intellectual class. If we imagine the Islamic golden age as a long, bright day, the years between 750 and 861 were its morning, and the time when social and economic systems were established that catalyzed the flowering of Islamic art and science over the next few centuries. And while these secular developments were central to later Islamic history, Islam itself underwent important developments during the early Abbasid caliphate, as well.

Just as Christianity was still very much in development a century and a half after the death of Jesus, in the year 750, Islam was still being codified and buttressed by a textual tradition far larger than the Qur’an. The four doctors of Islamic law worked during the early Abbasid period, these being Abu Hanifa, Malik ibn Anas, ash-Shafi’i, and Ahmad ibn Hanbal, thinkers whose legal frameworks still subdivide the world of Sunnism today. The imam Ja’far al-Sadiq, Muhammad’s great great great grandson, and one of the main figures in Shiism and Sufism, concluded his career in the early decades of the Abbasid caliphate. Around the end of the years between 750 and 861, a number of the most important Sunni hadith compilations were well underway, compilations that would prove second only to the Qur’an in Sunnism, forever after. Foundational works on early Islamic history came into being, as well, including those of ibn Ishaq, ibn Hisham, al-Waqidi, and ibn Sa’d. And toward the end of the period between 750 and 861, the Mu’tazilite movement, a movement focused on applying reason to theological conundrums, became a flashpoint of controversy in the Abbasid empire.

What is perhaps most important to understand about the early Abbasid era is that during this caliphate’s first century, the early history of Islam as we know it today was written, just as the later history of Islam was set in motion. The early biographies of Muhammad that are still read today, and the Jahili literature and history still studied today, comes down to us from early Abbasid writers, and early Abbasid writers also formulated the law codes, exegeses, theological debates, and many of the prophetic traditions still central to Islam today. Between 750 and 861, then, the Islamic present created the Islamic past and future simultaneously. Few other dynasties have presided over a period as pivotal to world history as the first ten Abbasid caliphs.

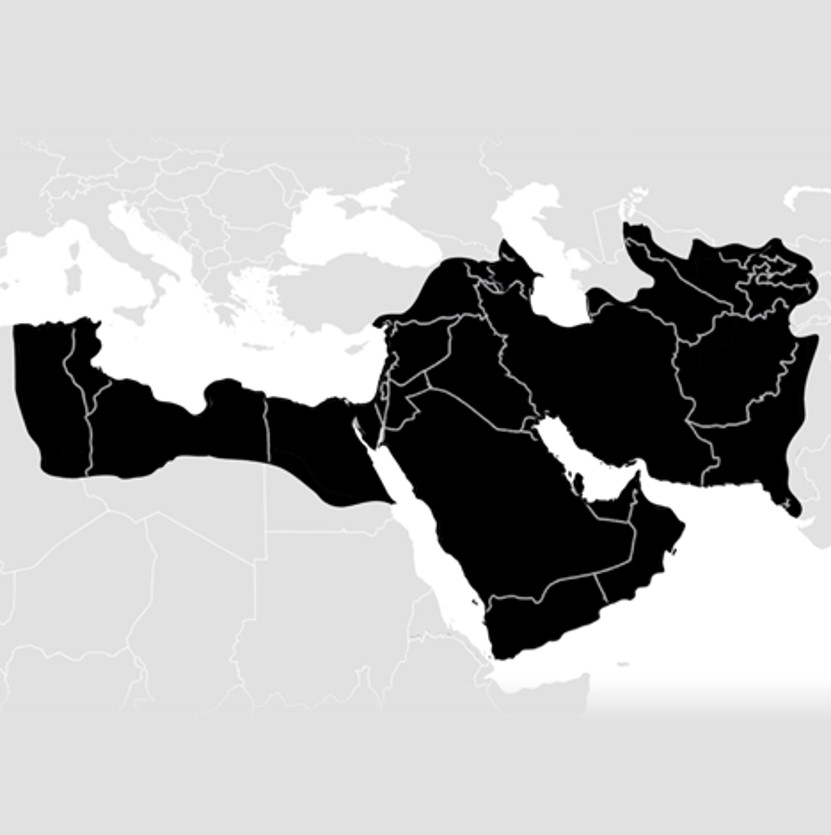

They ruled over a gigantic and topographically diverse empire. It included the Arabian Peninsula, and the Sawad, or Black Land of the Tigris and Euphrates, of course. But the caliphate also held the snow-capped peaks of the Zagros and the rugged territory around the Oxus, the lush wetlands around the mouth of the Indus, the chilly Iranian steppe and the sweltering Egyptian Nile, the leafy southern shore of the Caspian Sea and the long miles of the Helmand River, the Georgian Black Sea coast, and the heterogeneous populations of the Levant. The flag of the Abbasid caliphate was a rectangle of uniform black. Looking at it, we might imagine an empire, stretching from Tunisia to Kyrgyzstan, similarly uniform in nature, ruled by one dynasty and one religion. But the Abbasid caliphate, like the Roman empire before it, was a patchy dominion with many gradients and hues, staked into cities and garrisons, but thin in the countryside and leaky along borders.

So let’s take our first few steps into the Islamic golden age, an epoch on which we’ll ultimately spend multiple seasons. We will begin the story of the Abbasid caliphate from 750-861 not at the beginning, but just a bit before the beginning, and review what we learned last time about the Abbasid revolution – that series of events that, over the second half of the 740s, ended the power of the Umayyad dynasty. [music]

The Rise of the Abbasid Dynasty

The Umayyads, who ruled from 661 to 750, ultimately made two mistakes. The first mistake was nepotism. The second, related mistake, was often ignoring the egalitarian doctrines of Islam and creating a civilization in which some Muslims were more equal than other Muslims. Especially in Iraq, and in the eastern region where present-day Iran and Afghanistan come together, discontent at the Umayyad regime’s discrepant policies had reached a boiling point by the late 740s. The Umayyads were a Syrian regime, and they lorded their clan ties and old Arabian roots over everyone in the empire, their provincial appointees sucking tax revenue from all over and channeling it into Umayyad coffers. Many subjects were opposed to them for many reasons, but it was, again, the late 740s when discontent finally flared into a successful revolution.The Abbasid revolution had long, complex roots. Throughout the Umayyad period, more and more from 661-750, subjects of the caliphate had begun to look at the Umayyad rulers as corrupt interlopers who had usurped leadership of the Islamic world. Dissidents of the Umayyad caliphs had many ideas about who should be on the throne. On one side, there were those who, following ancient Arabian customs, thought that each new ruler ought to be selected through inter-tribal consensus, and that religious leadership was not necessarily the prerogative of the caliph. On the other side was a diverse polity who, as decades passed, rallied behind different descendants of the Prophet Muhammad, believing that God had invested these descendants with the capacity for both sacred and secular leadership. This second group can loosely be called Shi’at Ali, or the party of Ali, often called the Alids in modern scholarship. Shi’at Ali, during the Rashidun Caliphate of 632-661, can be understood fairly simply as supporters of Ali ibn Abi Talib, the Prophet’s cousin and son-in-law, and his two sons Hasan and Husayn. As the decades of the Umayyad caliphate stretched onward, though, Shi’at Ali began to rally behind different leaders, including Zayd ibn ‘Ali, a great-great-grandson of Muhammad, and ‘Abd Allah ibn Mu’awiya, a descendant of ‘Ali’s brother Ja’far, and thus not actually a genetic descendant of Muhammad.1 While the candidates that they backed changed from generation to generation, what the Shi’at Ali shared was a revolutionary optimism that leaders existed who, once enthroned, would begin a fairer and more righteous era of Islamic history.

There were, then, throughout the Umayyad caliphate of 661-750, Muslim subjects who wanted new, meritocratic leadership selected by consensus, and what we might call a partial partitioning of church and state. And then there were Muslim subjects who believed that Muhammad’s descendants, once brought in to lead as imams, would set things on a better course. While these two groups, just prior to the Abbasid revolution, had significantly different ideas about who ought to lead the Islamic empire, they strongly agreed that the Umayyad caliphs should not be in charge. The Abbasid revolution took place during the late 740s, when the millenarian ideas of the Shi’at Ali converged with the broader dissent of other groups in the Umayyad empire. The Abbasid revolution took its name from Muhammad’s paternal uncle, Abbas ibn Abd al-Muttalib, as it was the descendants of this uncle, the first Abbasid caliph, as-Saffah, and then as-Saffah’s brother, al-Mansur, who assumed leadership after the revolution.

It was thus the descendants of Muhammad’s uncle, rather than Muhammad himself, who, in the year 750, became the new kings of the Islamic world. Their enthronement was heartbreaking to the Shi’at Ali, who wanted the same thing they’d already sought for a century – Islamic leadership held by the genetic descendants of the Prophet. The Abbasid regime was equally dissatisfying to purist sects of Islam like the Kharijites and Ibadis, to whom the Abbasid revolution simply looked like one clan of Arabs pirating power from another clan of Arabs, and for the sake of worldly gain, rather than any revitalization of Islam; a new greedy boss, same as the old greedy boss. But inasmuch as some groups within the Islamic world in the year 750 reeled at the thought of Abbasid leadership, many did not. The Abbasids were, if nothing else, a clean start. The Abbasids had never opposed the Prophet, like the old Umayyad patriarch Abu Sufyan had. The Abbasids had never killed the Prophet’s grandchildren, like the Umayyads had. The Abbasids might not have been the direct descendants of Muhammad, but they were still Hashemites – in other words, leaders from Muhammad’s own clan. For all of these reasons, then, the Abbasids, when their first leader declared himself caliph on October 31st, 749 in Kufa, had as decent a chance as any group at holding power in the gigantic empire. Centrist, of acceptable pedigree, and otherwise embodying a reasonable cross section of what many had wanted across the caliphate, the Abbasid regime would ultimately be one of the most successful dynasties in history. [music]

The Abbasid Caliphate’s First Few Years

Real political revolutions are very messy. They begin due to fortuitous coalescences of forces. Then a goal is achieved – usually something is overthrown. Then there is a period of equilibrium and often recidivism, and fissures appear in the coalition that catalyzed the revolution, such that powerful members of a previous regime are able to retain some of what they had before. All of this was the case with the Abbasid revolution, which, to put it very cynically, replaced an old avaricious clan monarchy with a new avaricious clan monarchy somewhat more adept at leading and with less ethical baggage.

Frankish diplomats came to Baghdad in 797. In European and American history, the story of the embassies between the Franks and Abbasids have proved especially fascinating, making this one of the more enduring images of the whole early Abbasid period. The painting is Julius Köckert’s Harun al-Rashid receiving a delegation of Charlemagne in Baghdad (1864).

Though Umayyad power was a thing of the past by 752, and although the first Abbasid caliph as-Saffah had declared himself ruler, the caliphate was a gigantic landmass, with various regions that wanted to go their own way. On the west side of the Zagros Mountains, the Abbasids made government a family business, taking control of many of the most important governmental and military posts. Not everyone was elated at the clan’s manifold seizures of power in the west. Powerful families in the old Umayyad headquarters of Syria keenly missed the ousted leadership. But by and large, for a new regime, the Abbasids had a reasonable degree of control over the western half of the empire.

And then, there was the east. On the east side of the Zagros Mountains, the Abbasid revolutionary leader Abu Muslim, as of the early 750s, ruled much of what is today Iran as an autonomous kingdom. Charismatic, shrewd, and as history would soon prove, revered by many native Persians, Abu Muslim was a significant threat to the first two Abbasid caliphs. This was the state of the very early Abbasid Caliphate in the year 754, when its first caliph, as-Saffah, died. The western half was ruled by an old Quraysh clan. The eastern half was ruled by Abu Muslim, the revolutionary who had helped the Abbasids to power, but then, quietly and carefully, maintained power.

It is worth pausing here for a moment and talking about a specific region of the Abbasid empire. This region is called Khurasan. Understanding what and where Khurasan is is essential for understanding the early Abbasid caliphate, so let’s get it in our minds – Khurasan, Khurasan, Khurasan, spelled K-H-U-R-A-S-A-N. Khurasan, in the early 750s, was an immense region in the northeastern Abbasid empire. Its boundaries today encompass the hot and dry stretches of eastern Iran, the southeastern shore of the Caspian Sea and lowlands of southeastern Turkmenistan, and almost all of Afghanistan, to the north, abutting the Oxus River. It was and is an ecologically diverse region with many natural resources. Though lacking a central agricultural cash cow like the Nile or Tigris and Euphrates floodplain, Khurasan not only had a wealth of unique minerals. It was also the region where silk road goods entered the Islamic empires, just as they had previously entered Persian empires.

Just beyond Khurasan was a region that historians of antiquity often call Transoxiana, or the north bank across the Oxus River. Transoxiana included excellent farmland fed by water coming out of the mountains of Tajikistan, and its cities, sometimes controlled by Islamic empires during the Middle Ages, and at other times, other groups, were hubs for east Asian goods on their way to the west. Khurasan, then, which was at the northeastern extremity of the early Abbasid empire, was, especially after the 700s, an extremely important and influential place during the Medieval period. Early Iranian dynasties were rooted there, and from end to end of the Middle Ages, all the way up until the Mongols invaded in the 1200s, Khurasan was the cultural epicenter of Persia – the home of Avicenna, al-Biruni, Omar Khayyam, and other heavyweights of intellectual history. Sometimes expanding to the north bank of the Oxus, and at other times not, Khurasan was a gigantic, spongy region capable of going its own way even when Abbasid Baghdad was at its mightiest, as was the case when the de facto eastern revolutionary leader Abu Muslim, in the year 754, held power in Khurasan, not particularly concerned with what was going on 1,000 miles over to the west in Baghdad. So, that’s Khurasan, again centered at the juncture between modern day Iran, Afghanistan, and Turkmenistan. Khurasan was where the Abbasid Revolution began, and whenever major events happened in early Abbasid history, Khurasan was usually involved.

The Difficult Early Reign of al-Mansur (r. 754-775)

When the first Abbasid caliph As-Saffah died in 754, his brother, Abu Ja’far, better known as al-Mansur, came to power. Al-Mansur, one of the most famous and successful of all the Abbasid caliphs, would be on the throne from 754-775. While al-Mansur achieved a lot during his long reign, and in many ways can be thought of as the first Abbasid caliph proper, as of 754, when Al-Mansur inherited the Abbasid throne from his brother, the paint on this throne had barely had a chance to dry. The second Abbasid caliph al-Mansur had foes on the west side of the Zagros who resented him for economic reasons, and in Iran, Abu Muslim ruled an entire hemisphere of the caliphate, with powerful Persian families in far-off Khurasan keen on backing a separatist eastern state. And everywhere, east and west, many Muslims who had crossed their fingers during the Abbasid ascension from 750-754, as historian Hugh Kennedy puts it, “found that, instead of a new society, based on the Qur’an, justice and the equality of all Muslims, led by a divinely elected imam, they had simply replaced one ruling elite with another and that a substantial section of the old elite had actually been incorporated in the new.”2The early years of Al-Mansur’s caliphate, then, were spent trying to shore up power. One of his uncles made a bid for the throne throughout the second half of 754, marching from Syria to the main Abbasid power base in Iraq. This early rebellion, with roots in dissent from the former Umayyad aristocracy of Syria, was ultimately unsuccessful, with al-Mansur’s eastern ally Abu Muslim offering the caliph military support. Yet almost as soon as al-Mansur’s uncle’s rebellion was quelled, a new conflict flared up. As mentioned earlier, the revolutionary leader Abu Muslim had been central to the fall of Umayyad power in the empire’s enormous eastern territories. After the revolution, Abu Muslim had unofficially ruled half of the new caliphate, a half whose demographics and geography made it look suspiciously like the old Persian Empire. As ambitious as al-Mansur was, he was no Arab Diocletian, amenable to an imperial co-ruler. Al-Mansur took steps to put Abu Muslim in his place.

Their conflict began with a provocation. Al-Mansur offered the eastern revolutionary Abu Muslim a governorship – Abu Muslim could govern the rich province of Egypt, or of Syria. Abu Muslim declined. He did not want to come over the Zagros Mountains and rule a single province of the caliphate. He already ruled its entire eastern half. Al-Mansur was prepared for this rejection. The Abbasid caliph was able to compel Abu Muslim into a meeting with him. At the meeting, the caliph leveled treasonous accusations against the revolutionary who had helped him to power. And Abu Muslim, without whom the Abbasid Revolution would never have taken place, was executed in February of 755. His death marked the end of the Abbasid caliphate’s birth pangs. Abu Muslim remains a somewhat mysterious figure, swept under the rug by Abbasid historiography. To many Persians in the mid-750s, Abu Muslim’s death marked the end of a short-lived dream of the return of an autonomous Persian state, led by a Muslim seated in present-day Iran and an ethnic Persian more sensitive to the nuances of former Sasanian territories than a caliph enthroned in faraway Iraq or Syria. From the caliph al-Mansur’s perspective, though, Abu Muslim’s refusal to govern in the west meant that Abu Muslim was an existential threat to Abbasid rule. Al-Mansur, as we’ll see in a moment, had big plans, and there was no place in those plans for a semi-sovereign eastern division of the empire with an overwhelming majority of Persian speaking citizens.

When Abu Muslim died – again in early 755 – an uprising occurred which demonstrated the extent to which many Persians saw Abu Muslim as a way forward for Persian independence. An Iranian named Sundabh led a rebellion which aimed to do nothing less than restore Persia to Persian rule, revitalize Zoroastrianism, and eventually, to destroy the Kaaba itself. Sundabh’s rebellion got traction quickly, taking over a town just south of modern-day Tehran and receiving support from an area called Tabaristan, roughly speaking the rugged southern shore of the Caspian Sea. This rebellion heralded more to come. Old families of the Sasanian empire, faithful Zoroastrians, and average Persians alike resentful of the new Arab-Islamic hegemony all had cause to rebel against Abbasid rule, just as they had had cause to rebel against Rashidun and Umayyad rule. Abu Muslim’s death, to these Persian rebels, meant that the significant role they had played in the Abbasid revolution had resulted in nothing more than the continued ascendancy of an Arab-Muslim regime from far away. Persian insurgencies, and moreover insurgencies in the Abbasid east, would be a fixture for long durations of the caliphate’s history. In 755, however, the Persian revolutionary Sundbah’s army was defeated, and hopes for a Persian resurgence were decisively disappointed for a generation.

So, let’s turn our full attention to al-Mansur, now, again one of the most famous caliphs in all history, on the throne from 754-775. Al-Mansur, as we’ve just learned, had immediate military challenges to contend with when he ascended to the throne. He also faced ideological challenges. One of the most volatile ideological forces in the newborn caliphate was what we can call messianism – in other words, the belief in a coming messiah. A main accelerant of the Abbasid revolution was the notion that a savior figure would take the reins of the caliphate and lead people to a better tomorrow. Al-Mansur was not the descendant of Ali ibn Abi Talib that the various Alid uprisings had sought. And al-Mansur, in addition to his Abbasid successors, found the messianic beliefs of the Alids and other groups to be especially intractable.

We have, in our podcast, learned about many imperial ascensions, after which an emperor placates, exiles, or executes his obvious rivals, and then is able to rule and get things done. The Abbasid regime faced a unique challenge with the Alids, however, because there were many descendants of Ali, and their supporters rallied behind them at different times and different places, and each one, according to his backers, had a divinely ordained claim to sovereignty. If an Abbasid emperor favored a descendant of Ali and his supporters, then that Alid rose to more dangerous prominence within the empire. If an Abbasid emperor persecuted or executed a real Alid, then the emperor found himself in the dreadful position of harming a descendant of the Prophet Muhammad, which was not only morally unconscionable, but also created a martyr and catalyzed more messianic support against the Abbasid regime.

Al-Mansur dealt with this issue as best he could. Between 755 and 762, two Alid brothers, “Alid” again meaning descendants of Ali, first evaded and then rebelled against the caliph Al-Mansur. One brother eventually led a rebellion from Medina and died fighting Abbasid forces, and the other led an urban revolt in Basra, which, with more difficulty, was put down in 763. A letter survives in the historian at-Tabari in which al-Mansur decries Alid claims to the Abbasid throne. To be clear, all Alids were genetic descendants of the Prophet’s daughter, Fatima, and in the letter you’re about to hear, al-Mansur emphasizes that the Abbasids, descended from Muhammad’s male relatives, are better suited to rule than the Alids, descended from Muhammad’s daughter. Al-Mansur states in the letter to his Alid challenger, “Now if your pride glories in the kinship of women, in order to delude thereby the uncouth and the rabble, still God does not make women the equal of paternal uncles and forefathers nor like the paternal relatives and male kindred, for God has made the paternal uncle like a father, and in His Book gives the mother a lower place.”3 While al-Mansur perhaps did believe that there was some theological justification for Abbasid rule rather than Alid rule, the Shi’at Ali who had already been backing Ali and his descendants didn’t agree. The suppression of their rebellions was arduous, but Abbasid leadership managed it. Though messianic Alid sentiments were never going to go away, as the winter of 763 gave way to spring, the caliph al-Mansur had finally guided the Abbasid caliphate past its nascency. Born out of a patchwork of revolutionaries, the new empire had taken a while to stabilize, its volatile east and internal factionalism making the Abbasid throne precarious for its first decade. Al-Mansur, however, even during his initial years of rule, had done more than grimly shoring up power. Al-Mansur, though he had some hurdles to jump during his first few years on the throne, intended to leave an impressive legacy behind, and in this, he certainly succeeded. [music]

Al-Mansur’s Founding of Baghdad and Sponsorship of Arts and Sciences

Let’s talk about some of the things that al-Mansur accomplished between 754 and 775 as the second caliph of the Abbasid empire. We have already discussed the military and political snafus that al-Mansur had to navigate during his first years on the throne, and so we can begin by quickly talking about the first Abbasid military. From the increasingly detailed annals of early Abbasid history, we can begin to get a sense of how the caliphate’s army was structured, and how it worked. There were, interestingly, what we can think of as military dynasties at work beneath the imperial dynasty. Military leaders known as quwwad, or generals, oversaw divisions of troops, and Abbasid generals passed military leadership down to their heirs. A hierarchy was thus ingrained in the early Abbasid caliphate, wherein the caliph appointed leadership to generals, often members of the Abbasid clan, who themselves handed subdivisions of military leadership down to their heirs. The political and military apparatus of the early caliphate, then, was largely a family affair, somewhat insulated from the ambitions of interlopers.Al-Mansur also paid the military well, and apportioned land to those who served. Early Abbasid records attest 80 dirhams a month for each soldier in the regular army – by contrast, laborers building cities in what is today Iraq were making just one or two dirhams per month, and so military service was a lucrative line of work.4 While al-Mansur funded the military well, the Abbasid clan more generally was able to align and collaborate with extant interests throughout the 750s, such that after the aforementioned insurrections wound down in 763, the caliphate enjoyed a period of relative peace.

Baghdad, a few decades after its foundation, had grown around the fortified round city and ballooned over to the east bank of the Tigris. It would be the epicenter of a lot of early Abbasid history.

Baghdad’s heart was the Round City, home to Al-Mansur’s palace, military quarters, and buildings that housed wings of the governmental administration. To the city’s northwest, military leaders were given plots of land, and soon the city spread to the east bank of the Tigris, as well. The area exploded in population between Baghdad’s founding in 762 and the end of the century, growing to perhaps half a million inhabitants by 800.5 Various satellite palaces grew over the early Abbasid period, and way up along the Syrian Euphrates, near the present day city of Raqqa, Al-Mansur founded the city of Rafiqa, likely a predominantly military outpost designed to manage the circulation of troops up along the Byzantine frontier.

Abbasid Baghdad, especially early Abbasid Baghdad, is one of history’s most famous places, comparable to Periclean Athens, Augustan age Rome, and 18th-century Paris, so it’s worth pausing for a moment to talk about the city’s first century. The centrality of Baghdad allowed it to become a hub of commerce and luxury nearly unique at that point in world history. A cosmopolitan metropolis at the seam between Europe and Asia, you could meet people from all over the world on the streets of Baghdad. In the later decades of the 700s, the Chinese travel writer Du Huan, after visiting Baghdad, remarked that “Everything produced from the earth is available there … Brocade, embroidered silks, pearls, and other gems are displayed all over markets and street shops.”6 Just as Baghdad was full of diverse goods, it was also theologically diverse. Built in a scenic bend of the Tigris, the city became a center of operation for Nestorian Christianity, and Jews, over Baghdad’s first century, moved academies from southern Iraq up to Baghdad, which became a center for Jewish learning. About a century after Baghdad was founded, the historian al-Tabari notes offhandedly that in the year 858, “the Festival of Sacrifice of the Muslims, Palm Sunday of the Christians, and Passover of the Jews coincided.”7 There is a sense here that these were public holidays that everyone knew about and that their falling on the same day was a coincidence curious enough for all practitioners of Abrahamic religion living in the city to note.

The second Abbasid caliph al-Mansur did something else between founding Baghdad in 762 and his death in 775. This was funding a great deal of writing. The most ambitious emperors in world history have not only tried to control the present and future. They have also endeavored to control the past. We began this season of the Literature and History podcast with a synopsis of Pre-Islamic Arabic poetry. Much of this poetry was assembled by the literary historian Mufaddal adh-Dabbi on behalf of the caliph al-Mansur. Al-Mansur also sponsored the biographer Ibn Ishaq, whose name we heard so often in episodes about the life of the Prophet Muhammad. Ibn Ishaq, who died in 768, completed his biography on Muhammad at the apex of al-Mansur’s reign, and the next major biographer, al-Waqidi, came of age during this same reign, writing his own Sira, or prophetic biography, under some of the most famous Abbasid caliphs. The historical accuracy of the Sira, or biographical literature about the Prophet Muhammad, as we’ve discussed in past episodes, is ultimately hard to determine. Enough of it sounds like hagiography that we can assume a fair amount of fiction went into Abbasid biographies of Muhammad. Where the early biographers Ibn Ishaq and al-Waqidi most likely did create some innovations are sections of their biographies dealing with Muhammad’s uncle al-Abbas ibn Abd al-Muttalib. Al-Abbas, from whom the Abbasids traced their lineage, became a prominent figure in Abbasid period biographies that are still popular today. Muhammad’s uncle, in ibn Ishaq and al-Waqidi, becomes a sagely figure in tune with the meaning of the Qur’an, and in the biographer al-Waqidi, uncle al-Abbas is more worthy of leadership than Muhammad’s son-in-law Ali. We have seen these sorts of revisionist history moves before, under different historical regimes. Augustus wanted his Julio-Claudian ancestors to be figures at the very foundations of ancient Roman history, and the poet Virgil took care of that for him. Constantine wanted to be the summit of Christian cosmic history, and Eusebius made it happen. In much the same way, the Abbasids wanted their rule to appear divinely consecrated, and historians willing to give the Abbasid patriarch Abbas a bit of extra sheen and sparkle had powerful incentives to do so.

Al-Mansur’s Succession

Al-Mansur and his successors, then, commissioned what historian Tayeb El-Hibri calls “the most critical phase in the shaping of Islamic textuality and culture.”8 We’ll talk more about the literary culture of the early Abbasid caliphate in lots of future episodes – the work of the poet Bashshar ibn Burd and the translator Ibn al-Muqaffa, both active during the early Abbasid period, and both ethnic Persians who spent their careers in Iraq, shows the confluence of Persian and Arab culture in Mesopotamia that so thoroughly characterized the Abbasid empire’s first century.It wasn’t all smooth sailing for the second Abbasid caliph al-Mansur after he founded Baghdad and fended off his major rivals. About a year after al-Mansur founded Baghdad in 762, and for much of the remainder of his reign, he faced a complex problem. This was the issue of succession. Al-Mansur’s brother, the first caliph, As-Saffah, had chosen a successor for Al-Mansur – this was the nephew of the two brothers, a young man named Isa ibn Musa. At the time, in the turbulent early 750s, the backup succession plan had been geared to ensure the longevity of Abbasid power. However, once al-Mansur had settled into his new throne room in Baghdad, and eliminated the major rival movements to his power, he wanted his son to take over as caliph after he died, rather than his nephew. Al-Mansur’s son Muhammad, known today as al-Mahdi, though young, was popular in the military, and as the Abbasid caliphate continued to flourish, al-Mansur’s son al-Mahdi seemed to many like a ticket to continued prosperity.

Al-Mansur, then, attempted to convince his nephew Isa ibn Musa to relinquish his claims to the throne. Al-Mansur tried several different strategies, but eventually it was the Abbasid military’s strong support of the son, rather than the nephew, that led Isa ibn Musa to give up his claim to the throne. The way for the third Abbasid caliph, al-Mahdi, was now clear. Al-Mansur died in the autumn of 775, while leading a pilgrimage to Mecca. In his mid-sixties, the caliph had reigned for more than twenty years, and in doing so, had brought the Abbasid state to healthy maturity. Al-Mansur had not been the messiah that many had wanted. He had left in place systems and legacies from the previous century that privileged some Muslims greatly above all others. But al-Mansur’s practical, restrained, intelligent oversight of the empire had fostered stability and security, and when his son al-Mahdi took the throne in early October of 775, the young man inherited a functional, healthy state.

Al-Mansur, between 754 and 775, all told, had proved a deft, talented leader; a harsh strongman who consolidated a dynasty in the disorderly aftermath of a revolution, but also an intelligent emperor with both foresight and restraint. He is, in hindsight, noted for his combination of authoritarianism and guile; his delegation as well as careful selection of bureaucrats and appointees, and his willingness to micromanage and involve himself in the minutiae of the state. He set his sons and grandsons up for peaceful, prosperous reigns, and over the next 35 years, his immediate descendants presided over a flourishing empire. [music]

The Ascension of the third Abbasid Caliph al-Mahdi (r. 775-785)

In 775, the third Abbasid caliph, al-Mahdi, ascended to the throne. He was in his 30s. His career, which had begun early, during his teenage years, had been a military one, based, early on, near what is today Tehran. In 764, the announcement went out that al-Mahdi would be his father’s heir, and al-Mahdi came west to join his father al-Mansur in the greater security of Baghdad. Father and son ruled together for eleven years, such that when al-Mahdi became a caliph in 775, he was militarily and politically experienced enough to be prepared for the role. His reign of ten years was relatively short, as far as caliphal reigns go, but it was also successful.Al-Mahdi’s ascension to the throne was a smooth one. Al-Madhi was well-liked in the military, and appreciated as liberal with the caliphal treasury, funding the construction and enlargement of some important mosques. As a spiritual leader, al-Mahdi was a different creature than his father, who had been a secular monarch more than an active Muslim figurehead. Al-Mahdi funded improvements to the road between Iraq and Mecca, so that pilgrims could more safely stop at watering holes and waystations, and ordered the elimination of partitions in mosques between regular worshippers and then leaders and potentates in the audience. These benign acts in the service of Islam, however, were counterbalanced by less benign ones. Al-Mahdi supported sporadic persecutions of those who rejected Islam, and gave a Chrisitan Arab tribe called the Taghlib the choice between conversion and death, although he seems otherwise to have treated Christian citizens according to Qur’anic precepts for clemency.

Al-Mahdi, as 775 turned to 776 and 777, faced some of the same challenges his father had. The new caliph wanted to pass power onto his son, although his cousin Isa ibn Musa had been promised the throne next, just as he had been the one intended to take the throne rather than al-Mahdi himself in the first place. Isa ibn Musa was given another payoff and swept under the rug once more, living the rest of his life out in what is today northern Iraq. In addition to than Isa ibn Musa, al-Mahdi also had to manage relations with the Alids, those descendants of Ali and the Prophet Muhammad whom many in the empire thought should be on the caliphal throne.

There were numerous Alids active during the early Abbasid dynasty. Some, like the revered Imam Ja’far as-Sadiq, stayed out of politics, passing on the traditions of the Prophet’s inner family and contributing to Islamic history with the hadiths and other writings they left behind. Other Alids were more politically active. The caliph al-Mahdi, who again came to the throne in 775, seems to have treated key Alids with proactive generosity rather than paranoid harshness. Medina, as it had been a century before, was a center of Alid activity, and al-Mahdi showered money on the city and its Alid-connected families in order to demonstrate that he was glad to have them in the empire. Al-Mahdi’s largesse to the Alids didn’t solve the Abbasid dynasty’s long-term problem with the presence of the Shi’at Ali in the empire, but diplomacy toward the Alids probably protected al-Mahdi from any especially serious Alid challengers to his rule while on the throne.

Al-Mahdi and the Rise of the Barmakids

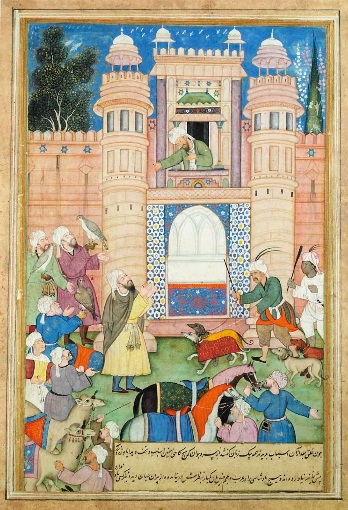

A member of the Barmakid family offering gifts to the Abbasid caliph, in a Mughal manuscript from the late sixteenth century.

The subject of a government bureaucracy doesn’t sound like a thrilling one at first glance. Bean counters in cubicles, so to speak, aren’t stereotypically as exciting as cavalry charges or naval salvos. However, during the early Abbasid period, a lot of interesting things were happening in the world of government departments. The years of al-Mahdi’s reign – again 775-785 – saw the old Umayyad and Rashidun distinctions between Arab Muslims and other Muslims softening. At the level of government bureaucracy, when an administration needed a director of postal service, or taxation, or transportation, that director didn’t need to be an esteemed Arab Muslim of noble extraction. In fact, it was often better for the Abbasid regime to just find a freedman or otherwise lowborn imperial subject. If, as a caliph, you hired a nobody, that nobody’s allegiances were going to be toward you, and toward their career, rather than toward enriching their familial or clan connections. The Kuttab, then, or bureau of government officials, and beneath them the Abbasid bureaucracy, became a meritocratic vehicle for hardworking individuals of various extractions, which, of course, was good for the health of the empire. As scholar Hugh Kennedy writes, the Kuttab quickly became “a highly educated élite of administrative secretaries. . .the mandarins of the early Islamic world, whose power and wealth were based on the fact that they alone could administer the revenue-collecting machinery on which the regime depended. . .they were also important as patrons of poets and prose-writers alike.”9 In particular, an Iranian family called the Barmakids flourished in al-Mahdi’s bureaucracy. These Persians, of old Sasanian extraction, distinguished themselves at various echelons of the Abbasid civil service. By the end of al-Mahdi’s ten-year reign in 785 – a central government had emerged in Baghdad whose general caliphate-wide interests were sometimes at odds with those of regional governors and military leaders.

Al-Mahdi’s reign, in spite of two expeditions against the Byzantines and one further afield in modern-day Pakistan, was generally a peaceful one. Later historians memorialized al-Mahdi’s ten years on the throne as politically peaceful and unexciting, and al-Mahdi seems to have been a generous, sophisticated, inquisitive, friendly person fond of hunting. One of his most famous exploits was purchasing a famous singer and musician from Medina and making her his concubine, and with this concubine, siring Ulayya bint al-Mahdi, who would herself be poet and musician, and fixture in the next generation of Abbasid court life.

The Caliphate of al-Hadi (r. 785-786)

The caliph, in his 40s in the 780s, had two sons eligible to rule, and he named both as successors. To use their later caliphal names, the older brother al-Hadi was to rule first, and then, in the event of al-Hadi’s death, ar-Rashid was to take his place on the throne. This sort of arrangement is always problematic, but without going into any great detail, when the caliph al-Mahdi died in a hunting accident in 785, his older son al-Hadi, about 22 years old, ascended to the throne, as his father al-Mahdi had intended, and the younger son, ar-Rashid, settled into a life comfortably away from the public eye.The older son al-Hadi’s caliphate was brief – a little over a year. He treated the Alids, again the descendants of Muhammad’s son-in-law Ali, more strictly than his father had, and a minor Alid rebellion in Mecca resulted, which the Abbasids squashed in the summer of 785. Following the rebellion, an Alid leader and descendant of Muhammad named Idris ibn Abd Allah fled to what is today Morocco, where the Idrisid Dynasty was soon established in 788, a dynasty which would endure in Morocco and Algeria for almost 200 years and abet the spread of Islam in northwest Africa. Other than unintentionally abetting the Idrisid Dynasty in present-day Morocco, though, the caliph al-Hadi was unable to achieve a great deal in his brief time on the throne.

Al-Hadi, like every Abbasid we have met thus far, could not endure the thought that anyone but his own son would inherit his throne, in spite of previous familial arrangements, and a year into his reign, he was planning to ouster his brother. Al-Hadi died, however, before he was able to formally declare his young son as his chosen heir. He may have had an ulcer, and he may have been assassinated – stories about this episode in Abbasid history focus on al-Hadi and his brother ar-Rashid’s mother, who preferred the younger son over the older and evidently had some political aspirations of her own. However it happened, in mid-September of 786, the fourth, short-lived Abbasid caliph al-Hadi was gone, and his brother ar-Rashid’s supporters, acting quickly, strongarmed ar-Rashid into the throne. Ar-Rashid would have the longest caliphate of the early Abbasid period – all told, the 23 years between 786 and 809. Ar-Rashid would preside over the most golden era of the early Abbasid empire, so let’s spend a bit more time getting to know ar-Rashid.

The Early Reign of Harun ar-Rashid (r. 786-809)

If you have ever heard the name of a caliph, there’s a good chance that name is Harun ar-Rashid. A character in the 1001 Nights, a lavish patron of the arts, and the leader of a peaceful and flourishing period of Abbasid history, Harun ar-Rashid was as generous as he was ruthless, and his 23-year long caliphate, though lauded to no end by Abbasid sources and dilettantish nineteenth-century orientalists, had some different phases, some ups and downs. The image of him and his chief minister Ja’far, strolling through the streets of Baghdad engaged in leisure and chicanery, is an appealing one in the 1001 Nights, but ar-Rashid, of course, was a real person with a long and complex political career. To begin at the outset of his caliphate, in the year 786, like many hereditary monarchs in history, Harun ar-Rashid came to the throne at a young age – somewhere between 18 and 20. As a young ruler, he needed a lot of help. Fortunately for him, help was available in the form of a sizeable and seasoned bureaucracy.Behind the early Abbasid caliphs was a group I mentioned a moment ago – the Barmakids. The Barmakids were an Iranian family that originally hailed from the caliphate’s far northeast – the city of Balkh in the north central part of what is today Afghanistan. From the first Abbasid caliph onward, the Barmakid family served the Abbasid caliphs at every level of the administration. Eventually, in the year 787, the Barmakids even acquired the caliph’s seal, and the power to make executive decisions on his behalf. When young Harun ar-Rashid came to the throne in 785, the Barmakids were already in the midst of taking desks at every echelon of the Abbasid bureaucracy. Harun ar-Rashid, content to delegate the responsibilities of ruling the empire to the Barmakids, enjoyed a symbiotic relationship with this bureaucratic dynasty. The caliph Harun ar-Rashid’s relationship with the Barmakids was, in fact, so close that it can be described as familial. He saw the leading Barmakid Yahya ibn Khalid as a paternal figure, and Yahya’s son Ja’far was the caliph’s dear friend. These Bamarkid handlers made themselves indispensable to the young caliph Harun ar-Rashid, deftly collecting taxes from the empire’s eastern regions, in particular.

The caliph ar-Rashid’s grandfather al-Mansur had founded the city of Baghdad with the intention of having a rich capital at the heart of the gigantic Islamic empire. Ar-Rashid presided over a period of continued centralization. The Abbasid regime and its Barmakid operatives, for the first half of Ar-Rashid’s reign of 786-809, shored up power at its center. With adept and loyal ministers at his disposal, ar-Rashid was able to diminish the importance of provincial governorships, slowly buying up and otherwise acquiring sawafi, or state lands, such that tenants and farmers paid dues directly to the caliph in strategic areas of the empire. Ar-Rashid’s own power grew, and just beneath him, the power of his Barmakid viceroys.

At first glance, the Barmakid ascendancy during the first decade and a half of ar-Rashid’s reign appears to be a recipe for a coup. After all, a shadow regime occupied in seizing bureaucratic posts in the imperial center might naturally go for broke and attempt to nab the caliphate itself. However, the Barmakids were more white-collar careerists than military crackerjacks, and they were Machiavellian only up to a point. When a number of rebellions flared up in the caliphate between 794 and 797, it became clear that military superintendence was not a Barmakid specialty, and after 797, Harun ar-Rashid, by that time over thirty years of age, leaned on his Barmakid ministers less and less.

Not everything ar-Rashid did involved bureaucratically convoluted statecraft. A moment ago, we learned that ar-Rashid’s grandfather al-Mansur had encouraged the creation of the earliest prophetic biographies. Ar-Rashid was also interested in Islam’s past, surrounding himself with a group of scholars and jurists together focused on the correct recitation of the Qur’an, and the drafting of Islamic laws based on the Qur’an, hadiths, and legal precedents. Ar-Rashid knew two of the four architects of modern Sunni law, Malik ibn Anas and al-Shafi’i, and his sons, who would both be caliphs, studied hadiths with Malik ibn Anas. Ar-Rashid’s genuine desire to help codify Sunnism for the future was matched by a shared sense of how religion can dovetail with political theater. The caliph’s southbound journeys from Baghdad to Mecca involved stops at population centers to appear before his subjects. Ar-Rashid’s wife Zubayda funded the creation of an 875-mile-long highway between Kufa and Mecca with dozens of watering stations to make sure pilgrims could get down to the central Hijaz safely from the Abbasid empire’s center.

Many of the major events from the middle part of ar-Rashid’s reign happened in the empire’s central north. Khazar raiders, coming down through modern-day Armenia, descended into Abbasid territories, and the armies of the caliphate were able to rebuff them. Closer to home, ar-Rashid, over the course of the 790s, seems to have developed an aversion to the metropolis of Baghdad, and he made his residence up in Raqqa in present-day Syria, increasingly avoiding Baghdad altogether. Additionally, ar-Rashid worked spiritedly to manage the Byzantine frontier, buttressing Abbasid control of the border, and leading the occasional campaign.

The Later Reign of Harun ar-Rashid

By the year 800, Harun ar-Rashid was in his late 30s. He still had nine years left in his reign, but he had also, by this point, been on the throne for 14 years. His style of governance over these 14 years had evolved. From relying on the Barmakid bureaucrats early on in his caliphate, he had increasingly pulled away from them. In Raqqa toward the end of his reign, though he had left Baghdad, the emperor was gathering power increasingly at the center of the caliphate by building out provincial towns with nearby bases for Abbasid troops. By the year 800, ar-Rashid was thinking about the future. Like every Abbasid leader before him, ar-Rashid wanted to pass power onto his sons. Unlike every Abbasid leader before him, ar-Rashid planned to divvy the Caliphate up, and to have his older son rule the western half, and his younger son, a half-brother of the first, rule the eastern half.The decision to divide the empire up was a strange one in many ways. Ar-Rashid’s caliphate, after all, and the caliphates of his Abbasid predecessors, had been characterized by centralization. The Abbasid empire had become strong because centralization in Baghdad helped keep its centrifugal forces in check. Dividing the caliphate into east and west, in particular, would underscore the eastern half’s already perennial tendency to turn into a culturally Persian breakaway state. Then, there was the more obvious problem that princelings do not share power well with one another, especially when each princeling has powerful, motivated backers who want to use him to further their group’s political aspirations. In spite of the manifold problems of trying to pass monarchical power down to two heirs simultaneously, as of the year 800, Harun ar-Rashid had set one son, about age 13, up in Baghdad, and the other son, also about age 13, up in Khurasan in the empire’s northeast. Power sharing agreements were drafted in the first few years of the 800s, and by 803, the terms of the coming co-rule had been established, and they were on display in contracts in the Kaaba in Mecca.

Harun ar-Rashid, Yahya ibn Khalid, and Ja’far ibn Yahya in a 19th century German edition of the 1001 Nights. The story of ar-Rashid and the Barmakids captivated several generations of nineteenth-century European intellectuals.

There is also a scurrilous and steamy story that survives about ar-Rashid killing his friend Ja’far because of Ja’far’s illicit relationship with the caliph’s sister. According to this story, Ja’far and the caliph’s sister, Abbasa, were part of ar-Rashid’s circle, and they hung out with him often. Because highborn women in the empire had to be carefully monitored in order to avoid controversy, ar-Rashid had drawn up a nominal marriage between Abbasa and Ja’far, so that the caliph could hang out with his buddy and his sister at the same time. However, so the story goes, at some point the nominal marriage got a bit too heated, and Abbasa got pregnant. She managed to have the baby in secret, but ar-Rashid found out about it. Hence, again according to this story, ar-Rashid suddenly going berserk in 803 and killing Ja’far and getting the Barmakids out of government. It’s a juicy, Suetonius-style tale of imperial intrigue, which is why I’ve just offered you the short version. But ar-Rashid’s sister Abbasa actually died in 798, and so it’s unlikely that a purge that happened five years later had to do with a princess’ sexual indiscretions.

Following the purge of leading Barmakids from government in 803, Harun ar-Rashid spent the final years of his reign between 803 and 809 absorbed in managing the affairs of the empire’s two most volatile frontiers. Ar-Rashid, in 805, funded a major attack on the Byzantine empire, in retaliation for an incursion by the new Byzantine emperor Nicephorus. This retaliatory campaign, though it didn’t result in much more for the Abbasids than the acquisition of a single new town, made excellent press for Harun ar-Rashid. Beyond the Byzantine empire, the Abbasids well knew, in the forests and mountains of central and western Europe, and the northern Mediterranean, there were more Christians.

The Abbasids had been in contact with Frankish monarchs since al-Mansur had exchanged embassies with Pepin the Short, and these embassies continued under Charlemagne and Harun ar-Rashid. Frankish diplomats arrived in Baghdad in 797, and Abbasid diplomats arrived in Pisa in 801, and later in 807. The 801 embassy, very famously, in Latin sources, brought with them an elephant – probably shipped over from Tunisia, not to mention a brass water clock, exquisite textiles, and silk robes, all unlike anything the Latin west of the early Medieval period had ever seen. Charlemagne’s court historian Einhard wrote of Harun ar-Rashid’s great esteem for the first Holy Roman Emperor in terms that are probably exaggerated. In reality, the Abbasid Caliphate and the kingdom of Charlemagne shared, for different reasons, hostility to the Byzantines, and to a lesser extent Al-Andalus, and so the two empires had some practical reasons to maintain strong diplomatic relations with one another.

More pressing to Harun ar-Rashid at the tail end of his career than the faraway frosty forests of France was the ever-volatile northeast of Khurasan. The Abbasid caliphate had been born from Khurasan, and Khurasan always threatened to become a power center to rival Iraq. Ar-Rashid led a campaign there toward the end of 808, accompanied by his son Ma’mun, who had been groomed to rule in Khurasan. Though the seasoned caliph probably planned a series of decisive victories in the northeast, ar-Rashid never made it to the frontier. He sickened near in the northeastern part of present-day Iran, near the border with Turkmenistan, and while the caliphal army proceeded onto the front, ar-Rashid, in his early 40s, died of an unknown illness. [music]

The Beginning of the Fourth Fitna (808-813)

In the early part of 809, following ar-Rashid’s death, his succession plans were put to the test. His sons were both about 22. One son, whom history would know as al-Amin, was securely enthroned in Baghdad, at the empire’s center of power. The other son, al-Ma’mun, was out on the eastern frontier, in Khurasan, surrounded by a large military. As it turned out, al-Amin and Ma’mun shared power together peacefully, and everyone lived happily ever after. Just kidding. Each co-caliph, albeit for different reasons, turned on the other. The saber rattling began almost immediately upon the death of Harun ar-Rashid, and the immensely successful first half century of the Abbasid caliphate, quite quickly came to its end.Whatever ar-Rashid had imagined happening upon his death, he seems to have forgotten a cardinal rule of the early Abbasid dynasty. And that is that when any new Abbasid caliph sat down on the Abbasid throne for more than half a second, no matter what sorts of agreements had been brokered, that Abbasid caliph would begin foaming at the mouth with the desire to pass power onto his own son, rather than any other previously discussed heir that made sense for the empire. It happened every single time, with every succession, and it happened when ar-Rashid’s son al-Amin plopped down onto the throne in Baghdad in 809. Al-Amin couldn’t possibly tolerate his equally qualified brother as a candidate for a throne for which his brother had been groomed. al-Amin had a toddler. And the most important thing in the universe was that no matter what al-Amin’s previous oaths had been, and no matter the cost in human carnage, this toddler had to be seated safely on the Abbasid throne so that the child might vomit and drool on its cushions. What did paternal and fraternal ties and the general wellbeing of an empire matter, after all, when a small infant posterior, still clad in diapers and unable to control its emissions, had not yet been guaranteed absolute power? What worth was all human life, when an infant with literally no leadership capacity whatsoever, who spent his days whimpering and mouthing his toys, had not been consecrated as the future head of state? Al-Amin wanted his son to be caliph, and so he began what would soon turn into a massive civil war called the Fourth Fitna.

The Fourth Fitna was a war between the caliph ar-Rashid’s two sons, al-Amin in the west, and then al-Ma’mun in the east. Its first phase, which we will now discuss, lasted for four years between 809 and 813. It had an enormous human cost, and although the two brothers who ended up leading the factions had backers who stoked the fires of the conflict, the war was, tragically, as preventable as any succession dispute, hence my overcooked sarcasm a moment ago.

The war began with a testy exchange between the brothers via letters, with al-Amin asking al-Ma’mun to – um – come back to Baghdad, because al-Amin – y – um needed al-Ma’mun’s advice. Al-Ma’mun declined and al-Ma’mun asked if maybe – um – could al-Amin send his family and relatives out to the east? Al-Amin declined, as these family members would be valuable hostages. Al-Amin held the main Abbasid control room when hostilities began in 809, and there, he declared that his aforementioned baby son would be the next caliph. On the other side of the mountains, Al-Ma’mun made some farsighted moves at the beginning of the conflict. Al-Ma’mun proclaimed himself as Imam – in other words, the divinely guided spiritual leader of Islam, in doing so, trying with some success to get some wind in his sails from the messianic sentiments circulating throughout the empire. Al-Ma’mun also cut off his brother al-Amin’s lines of communication to the east, thus keeping al-Amin insulated from what was going on over on the Iranian side of the Zagros Mountains.

Al-Ma’mun defeated his brother al-Amin in 813, as shown in this Persian manuscript from the late 16th century. In reality, al-Ma’mun was all the way over on the other side of the Abbasid empire when the defeat happened, so the illustrator is taking some poetic license here.

As the winter of 811 deepened, over in Baghdad, things went from bad to worse. Al-Amin, as it turned out, who had reached for the stars by setting his baby son up as an heir, had neither the leadership skills, nor the courage to back up his pugnacious ambition. The coalition that had amassed in his favor showed fissures. The most important of these fissures occurred in the western military. This military was, for a long time, staffed by lieutenants and regulars of Iranian stock, whose families had served in the Abbasid military for more than half a century, an impressive vanguard that had protected the military interests of a number of different Abbasid caliphs. These Iranian military men had failed in the conflicts of 811, and as the western half of the caliphate tried to field armies thereafter, long-held prejudices against Baghdad’s Iranian vanguard came to the surface. The western caliph al-Amin soon found that although he had military men willing to fight for him for different reasons, they weren’t necessarily willing to work together. An attempt to drum up more military support in Syria that same year also failed, and when the eastern caliph Ma’mun ordered an invasion or Iraq in the spring of 812, the eastern armies met with little effective resistance from the splintered western military.

As the army of the eastern caliph Ma’mun slashed upward through Mesopotamia toward Baghdad, in Baghdad itself, a coup broke out. The western caliph al-Amin was arrested, but then released in a dramatic turnabout. Having escaped by the skin of his teeth, al-Amin still had to deal with the presence of an invading army. It was, by this time, the late summer of 812, and between September of 812 and September of 813, Baghdad was under siege. The Round City, built for defensibility by the second Abbasid caliph al-Mansur, was, by the time his great-grandsons, the site of a terminal conflict and war of attrition. The citizens of Baghdad themselves were armed and acted as a defense force, but eventually, assailants from the east overpowered the Baghdadis. The western caliph al-Amin, who had both instigated the war, as well as mismanaged his side of it, surrendered, and was executed. [music]

Al-Ma’mun and the East-West Struggle of the Fourth Fitna, 813-818

The death of al-Amin in 813 marks the end of the first half of the Fourth Fitna. Although the eastern caliph al-Ma’mun had emerged as the sole heir of the Abbasid throne, al-Ma’mun himself was way over in the eastern part of what is today Iran. A year passed between the autumn of 813, and the autumn of 814, and tensions quickly rose between several different factions of the empire.The eastern caliph al-Ma’mun had won the civil war with his brother. But he was also, by late 814, still in Khurasan, and seemed to want to rule the Islamic empire from the distant east, never mind all the centralization that had taken place in Baghdad for the past fifty years. The idea of a Khurasani caliph, and moreover Iranian military boots stomping around the Tigris-Euphrates floodplain, was unpalatable to many Abbasid citizens who made their homes in modern-day Iraq. Thus, a simple east-west division lay at the heart of the rest of the Fourth Fitna, or fourth Islamic civil war. On the right side, there was a caliph in the east, and eastern military occupiers who had besieged and broken Baghdad. On the left side, or west, there were Iraqis, and beyond them, Arab families in Syria, Egypt and Arabia leery of a Persian power-grab.

While discord between the empire’s eastern and western halves kept the fires of civil war burning after 814, a more immediate source of disruption were the Alids. An Alid rebellion flared up in Iraq during the first weeks of 815, taking control of some important southern cities, including Kufa. The rebellion, not without difficulty, was put down by the Khurasani military leadership then present in Baghdad. Baghdad, as of 815, was under the leadership of a pair of brothers called the Sahlids. The Sahlids were sons of an Iranian who had converted to Islam from Zoroastrianism, and they were an important power bloc during the rest of Fourth Fitna. The brothers nominally served the victorious caliph al-Ma’mun, but they also sought power for themselves in Baghdad, generally endeavoring to keep the caliph al-Ma’mun way over in Khurasan so that he wouldn’t know how dysfunctional things had grown in the Abbasid epicenter of Iraq.

And things had indeed grown dysfunctional. By the summer of 816, a rebellion out of Baghdad had set its crosshairs on the Sahlid brothers, and later that year, the eastern occupiers and the resentful Baghdadis fought an inconclusive battle a hundred miles downriver from Baghdad. A year of messy history followed in Iraq, with the Baghdadi rebels being only slightly less organized and militarily unified than their Sahlid oppressors. By May of 817, though, the Sahlids, nominally serving the caliph al-Ma’mun, and definitely serving themselves, had Baghdad, and beneath it Mesopotamia, under their control.

Around the same time, and in events unconnected with the conflict in Iraq, the victorious caliph Ma’mun did something remarkable. In March of 817, Ma’mun, around 30 years of age, who had been in power for three and a half very rocky years, announced his successor. This successor would not be a drooling and unqualified infant, but instead a full-grown adult. The successor’s name was Ali ibn Musa ibn Ja’far, and he is better known as Ali ar-Rida. Ali ar-Rida was an Alid, or a descendant of the Prophet Muhammad, revered today as the eighth of Twelver Shiism’s twelve Imams. Al ar-Rida was older than the victorious caliph al-Ma’mun – about 50 years old in comparison to al-Ma’mun’s 30. Al-Ma’mun, it seems, was the first Abbasid caliph in several generations who made a succession appointment not out of fondness for his own son, but for the health of the empire.

Let’s review for a moment, just in case you’re lost in this whirlwind of military and political history. The Abbasids had always had trouble with the Alids. There was always a readymade contingent in the Abbasid empire who were ready to get behind a descendant of Muhammad’s son-in-law Ali. Against the careful efforts of the Abbasid caliphs to establish a continuous dynasty in Baghdad, the messianic energy in favor of the Alids created an ambient tension in the empire – a sense that the caliphal throne was just one succession away from this or that Alid who would suddenly commence a dramatically better future for the Islamic world. Thus, by naming an Alid, Ali ar-Rida as his successor, instead, gosh, I don’t know, his own baby son, the 30-year-old caliph Ma’mun was able to accomplish a lot of things at once. First, the Alids and the Abbasids were close kin. Both groups were part of the Prophet Muhammad’s Hashemite clan, and both families were eminently eligible for the caliphate, making Ali ar-Rida a very reasonable choice. Moreover, the caliph al-Ma’mun knew that there had just been an Alid rebellion out of Kufa two years prior, and that the Alids, seeing an Alid successor chosen as the next Abbasid caliph, would line up behind the current Abbasid caliph. Whether or not al-Ma’mun saw his handpicked Alid successor as an actual successor is open to question – again Ali ar-Rida was around fifty, so there’s a good chance that al-Ma’mun saw this quote unquote heir as a political expedient. Anyway, to move forward, and finally wrap up the Fourth Fitna, let’s talk about what happened next.

To repeat, in the spring of 817, just as the Khurasani forces of al-Ma’mun locked down control of Iraq, al-Ma’mun named an Alid as his successor. We might expect that this was the end of the war, but as it turned out, the black lands along the Tigris and Euphrates still had plenty of infighting left in them. Al-Ma’mun’s main military superintendents in Iraq were, again, the Sahlid brothers, and their incompetence continued when another Baghdadi insurrection broke out. In spite of the caliph al-Ma’mun appointing an Alid as his successor, the pro-Alid population of the empire, centered in Kufa, were not confident that a soft power transition to one of their own number was actually going to happen. The Sahlid brothers and their greater clan, as 817 rumbled to an ugly end in Mesopotamia, were obviously losing control. Another Abbasid dynast was suddenly hailed as caliph in the land between the rivers. Iraq was coming apart at the seams.

What is surprising about this period of the civil war is that the caliph al-Ma’mun, way over in Khurasan, had hardly known about the extent of the tumult to the west. When he learned of it, he finally, at the beginning of 818, left Khurasan to actually come to the heart of his empire. Before he reached Baghdad, the fractious city had been largely restored to peace. The rebel caliph fled, and Baghdad fell under the control of a general loyal to the caliph al-Ma’mun. It was on August 10th, 819 that Ma’mun entered the city of Baghdad as caliph, ending a ten-year period of general strife for the Abbasid caliphate. The Fourth Fitna was over, and Ma’mun, though already ten years into what had been intended as a co-rule, still had much of his caliphate ahead of him. [music]

The Reign of al-Ma’mun (813-833)

Ma’mun’s tenure as sole caliph began in 813, and it concluded in 833. His era on the throne was a period of both compromise and incremental success, rather than sudden, dramatic victories. He emerged as the victor of the Fourth Fitna slowly and through a series of concessions. He had wanted to rule from Khurasan, but eventually conceded to come to Baghdad. He may have wanted to squelch the various rebellions in Iraq with decisive military force, but instead did so through attrition, and the appointment of an Alid heir. One might say that al-Ma’mun, like some of his predecessors, came to the throne prepared to rule an empire, but instead found himself overseeing a patchwork of regions under varying degrees of caliphal control.

Al-Ma’mun finally came to Baghdad in the summer of 819, where, after a long civil war, he was hailed as caliph, as shown in this manuscript from the late 16th century.

Let’s stick with al-Ma’mun for now, though, and focus on his time on the throne following the civil war – again the years between 819 and 833. Al-Ma’mun needed all the help he could get. Ten years of civil war had allowed many regions of the caliphate to grow unkempt. Egypt had become divided, Syria had been polka-dotted with indigenous rebel groups, and Azerbaijan had fallen under the control of Persian nativist freedom fighters. Al-Ma’mun’s enforcers first locked down Syria, treating rebel groups there with clemency. Next on the list was Egypt, which had become subdivided into several different territories. By 827, the western part of the caliphate, through diplomacy and military interventions, had been brought back under the leadership of Baghdad. Azerbaijan presented a more complicated situation.

Azerbaijan, during the 700s and 800s, was at the northern periphery of the Islamic world. Colonization had taken place there, but, as with other porous areas of the Islamic empires, Arab settlers dealt carefully with extant populations who spoke different languages and continued to practice their own religions. With Baghdad enfeebled, between 809 and 819, by the Fourth Fitna, Azerbaijan had fallen under the control of a leader named Babak Khorramdin, a revolutionary of uncertain extraction who supported an eastern return to the glories of the Persian past, including Zoroastrianism. When a governor of Mosul was killed around 827 during clashes with the separatist movement based in Azerbaijan, the caliph al-Ma’mun dispatched a general to secure Mosul and then attack Babak Khorramdin further to the north. Using the rugged northern terrain to their advantage, Babak’s rebel forces outmaneuvered the Abbasid army, and the Abbasid general was killed. The caliph al-Ma’mun decided to cut his losses. Azerbaijan was abandoned for the remainder of al-Ma’mun’s caliphate, just as, over the opening decades of the 800s, the Abbasids had lost control over northwestern Africa.

Let’s talk for a moment about the distant peripheries of the Abbasid world, around the year 830 CE. Empires, as we’ve observed in Literature and History, move like water. An initial splash of military conquest is often followed by a receding of tides, as colonized populations reassert their rights to sovereignty. As the waters of empire recede, it becomes clear that not everything was actually conquered, and that indigenous cultures and institutions, resilient and obdurate, have sponged up only a small amount of the invading imperial culture. Where the waters of empire are shallow, power changes hands often, and hybrid ideologies and ethnicities commingle into new populations. In time, the waters of a past military conquest evaporate altogether, and what is left behind is a new patchwork of internal polities, self-interested and intractable to central imperial control. This process – conquest, and then simultaneous cultural synthesis and cultural resistance, was always at work in the Islamic caliphates. In 830, in particular, the north-central territories of Africa, a region called Ifriqiyya by the Abbasids, proved particularly unruly, just as Khurasan, all the way on the other side of the empire, already had.

The Peripheries of the Abbasid Empire in 830

Let’s start with Khurasan in 830, since we’ve already discussed this northeastern region of the empire. If the Romans had, in, say, the time of Trajan in 117 CE, consolidated all of the provinces they possessed, from modern-day Turkey to modern-day Iraq, given it a name, like “Romistan,” and crossed their fingers and hoped that it wouldn’t explode, they would have had something like Khurasan. Khurasan, by the tail end of al-Ma’mun’s caliphate in 830, was a province that ran a thousand miles from east to west, and included the Hindu Kush and other ranges, rivers, oases, and deserts; wastelands and huge cities, and pretty much every religion and ethnicity to be found in Central Asia in the early Medieval period. In Khurasan, Arab Muslims walked tall in big cities, but old Iranian aristocrats still had deep pockets and a lot of social and political power. Up in the mountains, checkerboards of powerful families along with subsistence pastoralists and nomads might live out their lives more or less indifferent to the Abbasid throne in Baghdad.

Khurasan in 836. Al-Ma’mun gave his general Tahir ibn Husayn sovereignty over Khurasan, beginning the Tahirid dynasty. Map by Ro4444.

The story of the early Abbasid caliphate, as I’ve emphasized several times, is a story that necessarily involves Khurasan, and the east, as the region was a volatile and evolving center of gravity in the early Islamic world. But a different region, called Ifriqiyya, was equally unruly. The Abbasids had lost control of their far western regions early on. First, Al-Andalus, around 756, had broken away into an independent emirate, ruled by an Umayyad prince named Abd al-Rahman I. After 756, Al-Andalus became the Emirate of Córdoba for a couple of centuries, and its various Umayyad leaders dealt with the Abbasid throne as nominal subordinates, though in reality they enjoyed sovereignty in southern and central Spain. The first Emir of Al-Andalus, precisely three decades into his reign, saw the ascension of the great caliph Harun ar-Rashid in 786. And in 786, the Emir of Al-Andalus began the construction of the Great Mosque of Córdoba – the building that still stands there today as the Mezquita, an emblem of the independence of Al-Andalus from the Abbasids.

With Spain having essentially broken off back in the 750s, then, the Abbasids also had to deal with central North African regions also asserting their independence. To turn to the subject of Ifriqiyya, let’s first define this region. Ifriqiyya can loosely be understood as modern day Tunisia, northeastern Algeria, and western Libya. This region, like faraway Khurasan, was on the empire’s outer edges. Umayyad and Abbasid garrisons, and the towns that expanded around them, created colonial populations of Arab Muslims. But beyond caliphate’s enclaves were Berber groups that had been there since pre-Roman times. What happened with these Berber groups during the century between 750 and 850 had a formative effect on North Africa, or al-Maghrib al-Adna, or the Maghreb, that can still be felt today.

Several episodes ago, we first met a group called the Kharijites. The Kharijites appeared during the First Fitna of 656-661. They are, in medieval Islamic sources, described as extremists – an uncompromising group characterized most of all by the belief that Islamic leadership should be based on Islamic piety, and not on clan, tribe, paternity, or ethnicity. The Kharijites were a diverse group that evolved over time, and yet even as they evolved, for the entire duration of the Umayyad and much of the Abbasid caliphate, they were a force with which each new caliph had to reckon. Caliphs passed the throne down to family members. Kharijites, on the contrary, taught that power in the caliphate should go to the devout and faithful, and not the highborn. Kharijites, then, believed in meritocratic leadership rather than hereditary monarchy. Tired of kings and princes, and dissatisfied with kingdoms in which some Muslims were clearly more equal than others, the Kharijites preached the appealing message of equality before God, and they were perennially a very powerful force in the early caliphates.

A map of the Abbasid Caliphate in 850. Note the Aghlabids and of course, the absence of al-Andalus, which became semi-independent back in 756. More autonomous dynasties would quickly arise in the third quarter of the 800s. Map by Cattette.