Episode 5: Beneath the Obelisks

We know about Ancient Egypt’s pyramids, temples, and sarcophagi. What about its folktales and stories, like “The Shipwrecked Sailor” and “The Eloquent Peasant?”

| Read Transcription | References and Notes |

| Episode Quiz | Episode Song |

| Episode on Spotify | Episode on Apple Podcasts |

| Previous Show | Next Show |

Ancient Egyptian Short Fiction: “The Shipwrecked Sailor” and “The Eloquent Peasant”

Hello, and welcome to Literature and History. Episode 5: Beneath the Obelisks. Last time, we took a long look at the Ancient Egyptian Book of the Dead, a vast tome full of incantations designed to safeguard the body and soul of the deceased. More copies and fragments of The Book of the Dead have been found in Egyptian dig sites than any other piece of writing. But Egyptians, like their Mesopotamian counterparts, were prolific writers. Though their writing materials were more perishable – often papyrus and linen, in comparison to the Mesopotamians’ durable clay tablet – we still have enough Ancient Egyptian writing to form a picture of their secular and commercial lives, as well.“Back Then”

I want to start with a couple of anecdotes. As someone who’s taught lots of literature at the college level, of course I’ve had to grade a lot of essays. For the most part, I’ve enjoyed it – it’s great to watch your students think through the prose, poems and plays that you love and have tried to share with them. Sometimes I’d jump up and dance. But occasionally, I’ve seen certain kinds of logically problematic assumptions or generalizations, and, like all English teachers, have tried to show students how this or that paragraph might be clearer or more argumentatively watertight. One generalization in particular that’s made me want to grind my teeth from time to time was when students would write, “Back then.”For instance, you might hear, “Hamlet delays his plan for revenge because back then people were very religious and they knew murder was bad.” Or, you might hear “Jane Austen’s novel ends in a marriage because she wrote in the early 1800s, and all women could do back then was get married.” Right. Or “Dante puts homosexuals in the Seventh Circle of hell because he lived in the Middle Ages and back then people were very ignorant.” Anyway, you get the idea. These kinds of statements imagine that time period and culture are massive forces that determine the way that we all think and act, never mind our individual personalities or intellectual energies. The notion of cultural determinism, as we call it, is useful. None of the statements above are totally false – they just operate with the kind of simplistic logic that most of us are able to move beyond after a certain point.

Let’s get back to Egypt. When studying the history of Ancient Egypt for the first time, more than with any other place or period of history, I felt tempted into culturally deterministic generalizations like the ones I was just kind of making fun of. I wanted some sort of window into the consciousness of individual Egyptians. I’d read three full length studies of Ancient Egypt, along with the usual assortment of documentaries, podcasts, and web content – man the twenty-first century can be cool. But the twenty-first century BCE, on the other hand, especially along the Nile, did not seem very cool. I was tempted into the kind of roughshod logic I’ve seen from time to time in undergraduate papers – I wanted to say, “Back then, there was a three thousand year long, bone crushing autocracy, led by the most narcissistic men earth has ever known.” Full stop. There’s a bit of truth to it. Early in his excellent recent study, The Rise and Fall of Ancient Egypt, historian Toby Wilkinson writes, “From human sacrifice in the First Dynasty to a peasants’ revolt under the Ptolemies, ancient Egypt was a society in which the relationship between the king and his subjects was based on coercion and fear, not love and admiration— where royal power was absolute, and life was cheap.”1 At its worst, the three or so millennia and thirty-one dynasties of the Nile read like a nightmarish what if scenario. What if a series of rulers, composed mostly of Neros, Louis XIVs, Kim Jong Ils, and an occasional Ghengis Khan subjugated a hundred generations of mostly powerless commoners? What if they were able to keep up a cult of leader worship so successfully that they could openly call themselves demigods, gods, or even sole gods? What if the record of a civilization that endured longer than almost anything that now exists were predominantly a long list of self-aggrandizing men willing to tear the tendons and sinews of ten thousand of workers just so that they could have big statues of themselves built, fashioned to look like gods? And worse than anything, what if rather being disgusted at the greed and egotism of the king, sharpening their Bronze Age daggers and killing him in his grotesquely oversized harem, his courtiers emulated him, building smaller versions of his tombs and monuments for themselves? There is no what if. Back then, all of this happened.

But beyond the tombs, the grave goods, the monuments, the inscriptions, the cold, humorless serenity of the pharaoh statues and colossi, there lived the Egyptians themselves, a busy, inventive, hardworking and increasingly cosmopolitan people that we have yet to say much about. [music]

Thebes, Autumn of 1363 BCE

For a minute, forget about the Giza plateau or the Great Pyramid, and picture Thebes, capital of the New Kingdom on the middle of the Egyptian Nile. The year is 1363 BCE. It’s autumn. The sun hangs high on the fresh stonework of Luxor Temple. The harvesters cut wheat and barley out in the kemet fields, the gleaners gather their leavings. Market stalls at the city entrances sell leeks, cabbages, figs, melons and pomegranates. From shores and boats, people wave at one another, and shoals of perch, catfish and eels weave through cattails and bulrushes. In scriptoriums, workers carefully copy the hieroglyphics of The Book of the Dead onto papyri and linen to be sold to the families of the bereaved, perhaps with unbroken solemnity, and more likely taking frequent breaks to engage in jokes and horseplay.This is the Eighteenth Dynasty, Ancient Egypt’s boom time. Egypt controls the lands of Israel and Palestine, they’ve forged partnerships with former enemies, and southward along the Nile from the Mediterranean come lapis lazuli from the mountains of Afghanistan, pottery from the Island of Crete, and fragrant cypress wood from the land of Canaan. Dock workers unload goods from ships, nervous merchants figure their profit margins, and little kids are told to be wary of crocodiles as they head out to the river to swim and look for frogs.

In the temple, king Amenhotep III, perhaps the greatest builder of all of Ancient Egypt’s leaders, is looking at a carving that will later be famous in world history. Amenhotep has his hands on his hips and is nodding in satisfaction. The carving shows his mother with the God Mutemwia, and describes, in lurid detail, how the two copulated to produce Amenhotep himself. The carving and captions please the king, who believes now that posterity will see him as the creator deity, the direct son of a god – a Jesus Christ of the middle Nile.

Outside, though, no one really cares. The pharaohs, after all, have always had big stone things being built for them. For the median citizen of the Egyptian capital, there are courtiers to dispatch, investments to consider, furrows to dig, sandals to fix, gossipy stories to exchange, gifts to buy, and dinners to prepare. Of course, when the jubilee comes – this is the festival in which the king parades as a god, with lavish costuming and buildings commissioned for the occasion – when the jubilee comes, everyone will go out to see it. And as we learned in the previous episode, Ancient Egyptians weren’t some mercantile secular society – they had strong convictions about the afterlife and made offerings to their ancestors. But their relationship to their king was not merely one of thoughtless idolization. Their literature, as you’ll see shortly, proves it.

The main idea of this episode is its title – “Beneath the Obelisks,” and, as the name perhaps implies, we’re going to try and figure out what Ancient Egyptians thought about their kings and their social order. We will see that they were often reverent, but also resentful, and critical, and even capable of astute legalistic analysis. If poor egomaniacal Amenhotep III, while looking at the umpteenth statue of himself that he’d commissioned, knew that nearby, some papyrus scribbling genius was penning something that would undermine all autocracy, he’d probably have been upset. He might have even had a trace of self consciousness about the fact that he’d just paid someone to create a stone carving of his own mother having sex. Maybe.

The vast bulk of what we’ve inherited from Ancient Egypt is a sort of stream of consciousness fantasy world – masterfully carved in stone and gold – of a very small group of leaders, many the products of brother-sister marriages, and even generations of these. To resist the kinds of messy generalizations I was talking about earlier, it’s important to remember that almost all of what we know about the culture and statecraft of Ancient Egypt comes from the tombs and stonework of their privileged 1%.

I think that because the monuments of Ancient Egypt are so unique, we’re conditioned to picture the nation’s entire history as a bunch of sweaty, bronzed laborers trawling blocks through the dust while a stoic strongman wearing a headdress and artificial beard nods in approval. In fact, excepting relatively isolated incidences of conscripted labor, the population was not just bowing and scraping at the base of the Great Pyramid. There were coups and assassinations, divisions of power, and an increasingly steady influx of foreigners. And the kingdom was large. Even to the first cataract, the Egyptian Nile is over seven hundred miles long, and the Nile Delta two hundred miles from east to west at its widest. Regional powers and cultures lay beyond the shadows of pharaohs and pyramids and colossi, and were far less subject to the deifications and delusions of the kings.

We’re going to spend the rest of this episode talking about two pieces of Ancient Egyptian writing. There are many that we can consider, but I want to try for quality rather than quantity. The first one is a very short story from what we call the First Intermediate Period – it was believed to have been written around 2000 BCE – and it’s called “The Shipwrecked Sailor.” “The Shipwrecked Sailor” is a fairy tale about a sailor who gets marooned on a strange island where a giant serpent talks to him about the meaning of life. The second story, dating from about two hundred years later, is called “The Eloquent Peasant.” “The Eloquent Peasant” is about a downtrodden commoner who will not accept the provincial bureaucrats who steal his possessions, and who later sways the Pharaoh himself with his extraordinary powers of persuasion. These two tales, “The Shipwrecked Sailor,” and “The Eloquent Peasant,” are part of a small group of fifteen or twenty fictional narratives discovered alongside the far more common religious texts of Egyptian tombs. If you think about it, that’s a pretty small collection, and it’s obviously just a tiny, tiny portion of what must have been circulating around Ancient Egypt throughout its thirty-one dynasties.

The papyrus plant. You don’t exactly look at this picture and think, “literature,” but nonetheless the leaves of this plant were harvested, woven together into mats, and pressed into flat sheets. Learn about how it was made on this wonderful page from the University of Michigan. Photo credit: By SuSanA Secretariat [CC BY 2.0], via Wikimedia Commons

But we do have some. In fact, thanks to William Kelly Simpson and other editors and translators, we have a whole anthology. The main book I’m quoting from today is called The Literature of Ancient Egypt (2003). It’s published by Yale University Press. The Literature of Ancient Egypt is the book to buy if you’re interested in Ancient Egyptian literature. Mine, which I first obtained about seven years ago at a campus bookstore, even came with hot pink highlights from its previous owner, a girl named Nidan. Nidan, if you’re listening, you may not have this book back. Selling it back to the bookstore was a big mistake. But thanks for those highlights and lecture notes in the margins. Totally helpful.

Now, let’s get into the first story. Let’s go back in time, a dizzying four thousand years, to a turbulent period of Ancient Egyptian history. Let’s lean closely over a tattered manuscript that’s older than any religion now practiced, breathe in its mysterious scent, study its unfamiliar black and red hieratic script, and see what it says. [music]

[music]

The Shipwrecked Sailor

A Sailor and His Commander: The Frame Narrative

It had been a long, difficult expedition, but the men were returning home. They had been in the south – perhaps quarrying, perhaps on a military exercise. But more importantly than the challenges they’d faced, and the distant lands to which they’d ventured, was the fact that they were going northward along the Nile, back to the capital.

Tomb art from Giza of an impressive Ancient Egyptian vessel, which could be propelled either by oars or wind power. Daily life in Ancient Egypt involved seeing these coming up and down the Nile and throughout the Nile delta.

The sailor wondered if the commander were nervous about his upcoming meeting with the king. Perhaps, thought the sailor, the commander could use some advice on how to prepare for the consequential meeting. “Wash up,” said the sailor, “So you can speak to the king with confidence, / So you can answer [him] without stammering. / The speech of a man can save him, / And his words can cause indulgence for him.” But still, the commander was silent, gloomy and enigmatic.

At a loss for anything else to say, the sailor began a story – his own story, about how he was shipwrecked on a strange island. And hence begins the central narrative of “The Shipwrecked Sailor.” [music]

The Sailor Gets Shipwrecked

In the midst of a vast body of water, in a great ship, the sailor voyaged, one member of a crew of a hundred and twenty brave men. In a strange section of the ocean on the way to some copper mines, the sailors were assaulted by a terrifying storm. The ship was obliterated and the sailors tossed into the ocean. The sailor who is the subject of this story was able to cling to a floating plank. Before long, he washed up onto the shore of an island.Utterly exhausted, the sailor staggered into a thicket and fell asleep in the shade. When he awoke, he found figs and grapes, strange berries, gourds and giant melons, and a profusion of fish and birds. It was a strange place, and it was strange that he was alive, and so he cut a hole in the ground, built a fire, and made sacrifices to thank the gods.

Drowsy after his adventures and plentiful meals, the sailor heard thunder, and was suddenly alert. He thought it might be waves crashing at the seashore, but then he saw something. The trees were moving, and the earth shuddered, and something came through the branches. It was a giant serpent, almost fifty feet high, glittering with gold and gems, and it peered down at him, its eyes great and blue jewels.

“Who has brought you?” (45) it asked. The sailor collapsed onto his belly, mortified. “Who has brought you?” it said. The sailor did not speak. “Who has brought you?” it repeated, and it leaned down, picked him up, and took him to its den. Upon realizing that he would not immediately be eaten, the sailor was able to speak. He told the creature his tragic story – that his friends had all been killed, and that mere chance had led to his survival. The serpent comforted him.

The Serpent’s Counsel

“Do not fear, do not fear, citizen,” it said. “Do not turn white, for you have reached me. / See, God has allowed you to live: / He has brought you to this island of the spirit” (50). The serpent told the sailor he’d be able to return home in four months, and that he’d be buried there, in Egypt, as all Ancient Egyptians wanted.And then then serpent told the sailor his own story. He had once, he said, lived in a family of 75 snakes – his brothers, sisters, and children. They prospered there, until one day a meteor fell, causing a great fire. All of his brothers and sisters perished. Although he almost died from grief, the serpent buried his family. At least, the serpent implied, the sailor had not had such misfortunes. “If you would be brave,” the serpent said, “and your heart strong, / You will fill your arms with your children, / You will kiss your wife, and you will see your [home]. / It is better than anything. / You will reach home where you were / Among your siblings” (51).

The sailor was grateful – grateful for his safety, and grateful for the serpent’s kindness and understanding. He stammered and promised to spread fame of the snake’s grandeur all over once he returned to Egypt. He even promised that “I shall have brought to you laudanum, oil, / Spice, balsam, and incense of the temples” (51).

The general location of the land of Punt, somewhere in southeastern Egypt or perhaps the Arabian Peninsula. Hatshepsut (15th century BCE) sent an expedition there which returned with myrrh and incense, and Punt in the Ancient Egyptian imagination was a realm of exotic goods and finery.

The sailor, endlessly grateful, brought the gifts back home and bestowed them on the king. Approving the lavish gifts, the king promoted the sailor into a higher position, and, though he’d lost his comrades and nearly lost his life, the sailor ended up safe, prosperous, and back at home. [music]

The Sailor’s Commander Responds

So that was the story within the story that the sailor told the gloomy commander, to cheer him up. The commander was about to meet with the king at the end of his own expedition, and the sailor probably wanted to hearten his superior, by showing that the king was good to those who were good to him. But the story ends with the commander speaking one mysterious, and incredibly dark line.“Do not be so proper friend,” said the commander. “What is the use of giving water to the fowl at daybreak / When it is to be killed in the morning?” In other words, you don’t need to comfort me. I’m done for. Thus the story of the adventuring sailor, an attempt to console a forlorn commander, falls on totally deaf ears. Now you know the story of “The Shipwrecked Sailor.”

The Historical Context of “The Shipwrecked Sailor”

What did this tale mean to its contemporaries? Was there some honorable military commander who’d been unjustly executed by a cruel and capricious king? Is the sailor’s folkloric narrative about the serpentine Prince of Punt disregarded because it is some outdated piece of paganism? Is it an excerpt from a far longer work, in which the tragic, haunted commander is a main character? All of these are tantalizingly possible, and we might have just experienced a single, small excerpt from a lengthy lost saga.To try and interpret what the story means is up to you. But let me offer a simple interpretation, informed by some straightforward historical analysis. The First Intermediate Period of Egyptian history was not a peaceful or orderly time period. The best thing that Ancient Egyptians had known was despotism. Skeletons of tomb and temple workers over the course of Ancient Egypt’s history show muscle tears, arthritis, bone breaks, hernias, and other signs of literally being worked to death. The civilization along the Nile was plagued by tuberculosis, Pott’s disease, and schistosomiasis, a disease caused by waterborne parasites. In such a place and time, one must have largely felt that one’s fate was out of one’s own control.

When the Egyptian King Pepi concluded his legendary 94-year-long reign near the end of the third millennium BCE, Egypt’s 6th dynasty collapsed and the country fell into chaos. This was the period of history that produced “The Shipwrecked Sailor.” Seventeen kings ruled in twenty years, and thereafter two factions, operating out of Thebes in the middle and Herakleopolis in the north, fought for a hundred and ten years. Nubian forces (and remember, the sailor and commander of the story we just read are coming back from Nubia) – Nubian forces were warmongering, and the peasantry suffered greatly under unregulated taxation by greedy local officials, faltering irrigation systems, and resulting famine. These were all the forces that pressed Egypt to hope for an afterlife and caused the cult of Osiris to become a national religion. Life on earth was chaos and suffering, and the idea of a blessed afterlife was a great comfort.

So to return to “The Shipwrecked Sailor,” I think it’s ultimately a secular folktale about forces beyond our control. Sometimes, these forces are good to us. The great serpent that the sailor meets gives him food and blessings, and the king, when the sailor returns home, offers him a promotion and material prosperity. In contrast, sometimes uncontrollable forces are not sympathetic to us. The sailor loses his hundred and twenty man crew to a tempest, the serpent loses his seventy-five member family to a meteor, and the commander – whatever it is that he specifically fears – is worried about something that he is powerless to change – as powerless as a chicken awaiting slaughter.

The story likens the pharaoh’s power to that of a terrible cyclone or obliterating meteor. But rather than making us feel awe or admiration, we simply feel sad. Powerful things kill our friends and families, our siblings and children, be they storms, or asteroids, or tyrants. The commander’s mysterious horror at the story’s end is horror at the unpredictability of a violent autocrat, who might rise up to harm his subjects as quickly as a natural disaster.

In the midst of a thousand inscriptions commemorating the dominion of this or that ruler, or proclaiming this pharaoh’s victory at a battle, or that pharaoh’s union with some divine being, I think that “The Shipwrecked Sailor” helps us see what life was like for the other 99% of the Egyptians who lived beneath the obelisks.

The next story we’ll look at, “The Eloquent Peasant,” isn’t so much of a downer. Written about two hundred years after “The Shipwrecked Sailor,” “The Eloquent Peasant” is a story about a commoner named Khunanup, whose persistence and relentless intelligence in the face of persecution and disenfranchisement eventually serve him well. While the meaning of “The Shipwrecked Sailor” is elusive, I think you’ll find “The Eloquent Peasant” to be clear as a diamond.

The Eloquent Peasant

Khunanup Gets Waylaid

In the countryside, just after the fall of the twelfth dynasty, or, say, 1750 BCE, there lived a peasant named Khunanup. A trader and farmer, Khunanup and his wife and children got along by growing provisions, eating what they needed, and exchanging the surplus for what they could not produce on their own. One day, Khunanup asked his wife to help him pack provisions for a journey, and shortly thereafter, he set out to a more central part of Egypt.In his donkey cart, the eloquent peasant Khunanup had plants, salt, wood, skins, seeds, birds, and other beautiful products of his homeland. He was passing through a stretch of countryside that belonged to a man named Rensi, but, knowing the penalties for trespassing, Khunanup stayed carefully on the path. The roadway wound down close to the river, and an overseer named Nemtynakte saw the peasant and his donkey cart approaching. The overseer studied the peasant’s wares, and the course of the roadway, and he thought carefully. Corn grew on the sloping hillside that led down to the track, and Nemtynakte the overseer devised a plan. He had a servant drape linen sheets over the pathway that lay beside the river.

Khunanup saw these sheets, and stopped. Nemtynakte confronted him. “Do you really,” he asked “want to tread on my fabric?”

Khunanup was undaunted. “I’ll do what I must,” he said. “My way is good.” Nemtynakte warned him again, and Khunanup again insisted that he was perfectly justified in using a public pathway. “My way is good,” he said. “The riverbank is steep, and the road is covered with your corn, and you’ve blocked the path with your linen. Do you really intend not to let us pass?”3 As the peasant slowed, however, his donkey leaned over and bit off an ear of corn. And this was exactly what Nemtynakte had planned.

“Your donkey has eaten my corn!” shouted Nemtynakte. He would, he announced, confiscate the donkey. Khunanup, in spite of his lowly status, was not afraid to express his disgust. “I know the master of this estate,” he said. “It belongs to Rensi. He’s driven every robber out of the whole country. Am I to be robbed on his estate?.”4 Nemtynakte did not like this insubordination. He got a cudgel, and beat the peasant. He took Khunanup’s donkeys, had them brought to his compound. Khunanup remonstrated, but Nemtynakte told him to be silent.

Some peasants might have returned home, scraped by on what provisions they had, and lamented the cruelty of the world. Khunanup was not one of these. He spent ten days hovering around Nemtynakte’s lands, telling the greedy overseer that his goods had been unjustly confiscated. Nemtynakte didn’t listen. Still, Khunanup was undaunted. He got his things, and went to the city to find the estate’s owner, Rensi.

It was difficult to get an audience with Rensi. Khunanup petitioned Rensi’s official, who relayed the complaint to the great landowner. “Lord,” the official told Rensi, “it’s only a matter that concerns one of the peasants of Nemtynakte. He was going to do business with someone other than Nemtynakte. You should know that peasants have to do business with overseers when overseers demand it. Why would you bother to punish Nemtynakte for the sake of a couple of donkeys and some dry goods?” But the landowner Rensi, for whatever reason, was curious to hear the argument of a persistent farmer, who’d traveled all the way to the city to make his petition.

Hence begins the main part of the story “The Eloquent Peasant.” It’s a series of nine different petitions in verse which fill about thirteen pages, with occasional narrative breaks. Khunanup tells the landowner Rensi that some justice must be brought to the greedy Nemtynakte, and, more generally, to impoverished people everywhere. While Knunanup’s mannerism is initially humble and sycophantic, his argumentative style becomes increasingly aggressive, and even insulting, leading to Rensi the landowner beating him at one point. Yet physical abuse, as before, is no bar to Khunanup’s unrelenting eloquence.

Khunanup’s Speech

I’m going to stitch together excerpts from Khunanup’s speech, quoting from the version in The Literature of Ancient Egypt – again, edited by William Kelly Simpson, and published by Yale University Press. I want you to see how Khunanup moves from humble supplicant to fearless champion of the disenfranchised, his argument unfolding and his anger building over the course of his ten days of speaking. It’s a speech calling for social justice for the repressed and prosecution of the wealthy and privileged who take advantage of them, anticipating the anti-monarchial and reformist arguments of thinkers like John Milton, Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Thomas Jefferson, John Stuart Mill, and Karl Marx. And best of all, it was written four thousand years ago, in one of the most iron-fisted autocracies the world has known. So here it is – the eloquence of “The Eloquent Peasant.” [music]Chief Steward, my lord:

You are Re, the lord of heaven, with your attendants;

The provisions of all mankind are from you. . .

You. . .make. . .verdant the fields and revive. . .the desert.

[You’re the] Punisher of the thief, defender of the distressed,

Become not / a raging torrent against the supplicant. . .

If you veil your face against brutality,

Who then will reprove evil? (34-5)

[These days] Goodness is annihilated, for there is no fidelity to it,

(No desire) to fling deceit backwards upon the earth.

Who [these days] can sleep peacefully until dawn?

Vanished (now) is walking during the night,

Or even traveling by day. (36).

You [Rensi] are satisfied / with your bread

And contented with your beer;

You abound in all manner of clothing

But evil is done all around you.

You who know / the affairs of all men

Can you ignore my plight?

You who can extinguish the peril of all waters. . .

Rescue one who has been shipwrecked. (33)

[You] who [are] well provided should be compassionate,

For force belongs (only) to the desperate,

And theft is natural (only) for him who has nothing of his own;

That which is theft (when done) by the criminal

Is (only) a misdemeanor (when done by) him who is [desperate].

One cannot be wrathful with him on account of it,

For it is only a (means of) seeking (something) for himself. (33)

[Y]ou are mighty and powerful,

Yet your hand is stretched out, your heart is greedy. . .

Behold you are (like) a city / without a governor,

Like a people without a ruler,

Like a ship on which there is no captain,

(Like) a crowd without a leader.

. . .you are a constable who steals, a governor who takes bribes,

A district administrator responsible for suppressing crime,

But one who has become the archetype of the perpetrator. (36)

Your grain is excessive and even overflows,

And what issues forth perishes on the earth.

(You are) a rogue, a thief, an extortioner. . .

You have a plantation in the country,

You have a salary in the administration,

You have provisions in the storehouse,

The officials pay you, and still you steal. . .(41)

There is no one who was silent whom you caused to speak.

There is no one sleeping whom you caused to wake.

There are none who were exhausted whom you have revived.

There is no one who was closemouthed whom you have opened.

There is no one who was ignorant whom you have made wise.

There is no one who was unlearned whom you have taught. . .(40)

[C]ompassion has passed far beyond you. . .

[Y]our abode reeks of crocodiles. (33)

Idiot! Behold, you are struck!

You know nothing! And. . .you are questioned!

You are an empty vessel! And. . .you are exposed!

. . . . . . I appeal to you, but you do not hear it.

I shall now depart and appeal about you to Anubis.

With this final, blood curdling threat, Khunanup left the hall of Rensi the great landowner, after ten days of petitions which grew increasingly vehement and impatient. Even on the first day, Rensi found the peasant’s arguments powerful. He sent a copy of the first day’s speech to King Nebkaure, a reference to a real First Intermediate Period ruler, and Khunanup was promised the consolation of a small allotment of bread and beer. But Khunanup was implacable.

On the evening of the day of his last speech, Khunanup was summoned to Rensi’s quarters. He feared more beatings, but resolved to take what was coming, having said everything he’d wanted to say. Rensi the landowner then made his proclamation. He had had all of Khunanup’s speeches copied – not just the ones from the first day – and he’d sent them to king Nebkaure. Nebkaure had read them. This news fell heavily on Khunanup’s ears. The peasant knew that his speeches had been seditious, and that pharaohs did not take kindly to any form of insubordination.

But Khunanup was shocked by the response that he heard. The king had written that Khunanup’s speeches “were pleasing to his heart more than anything which was in his entire land” (44). After giving his unqualified approval, Nebkaure told the landowner Rensi to do with Khunanup as he saw fit. Rensi made his announcement. All of the lands of the thieving overseer – all of Nemtynakte’s donkeys, cornfields, linens, food, and finery, would be given to Khunanup. The two would have their places switched, with the fair-minded peasant in a position of prosperity, and the wicked Nemtynakte deprived of his former powers. And that’s the end. [music]

“The Eloquent Peasant” and Lower Class Dissent in Ancient Egypt

Well, now you know “The Tale of the Eloquent Peasant.” We don’t, of course, know if there was a real Khunanup, or whether the story is just a collection of proverbs placed into a frame narrative by some smart compiler. Either way, the very title of “The Eloquent Peasant” seems like a shocking oxymoron in the context of Ancient Egyptian thought. Fifth and sixth dynasty tombs featured carvings of tall kings and aristocrats at the triumphant moments of their lives, towering over wives and children, who barely come up to knee height. To quote historian Toby Wilkinson again, “scenes of peasants at work, disease, deformity, dirt, and dissent had no place in the aristocratic ideal of the ruling elite.”5 In other words, the peasant class was out of sight, out of mind.Why then, have two manuscripts come down to us that feature such an incendiary story? “The Eloquent Peasant” expresses vigorous, consistent criticism of the imbalance of wealth and power in Ancient Egypt. Aristocrats are not only agents of injustice – they’re also parasitic, useless things that live on the backs of the strong and capable. Khunanup’s furious accusation that “There is no one who was ignorant whom you have made wise / There is no one who was unlearned whom you have taught” (40) – this line and litany of similar statements against the wealthy paint a picture of a leisure class that contributes no work, no ideas, and no goods to society, but instead only consumes the work of others.

In its most sophisticated moment “The Eloquent Peasant” describes how the thefts of a poor person, made out of desperation to survive, are mostly excusable, whereas the thefts of the wealthy class, merely to swell their riches, are unforgivable. A poor man steals a loaf of bread and is beaten for it, and a rich man steals a wagon of bread and gets away with it. This is social order of “The Eloquent Peasant,” and I think its relativistic conception of class and justice is particularly stunning for the period. When you consider Khunanup alongside Hammurabi’s code of laws, written within the same half century, you can see just how far ahead of his time Khunanup was. “If anyone is committing a robbery and is caught,” reads the 22nd law of Hammurabi’s code, “then he shall be put to death.” That’s it. There are no qualifiers here, no questions of motive, as we see in “The Eloquent Peasant” – only crime and punishment. And it’s too bad that the eyes for eyes, the bones for bones, the killing for adultery that we see prescribed in Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers and Deuteronomy in the Hebrew Bible, set down twelve or thirteen hundred years after “The Eloquent Peasant,” lack the Ancient Egyptian papyrus’ more sophisticated notions of justice and legalism.

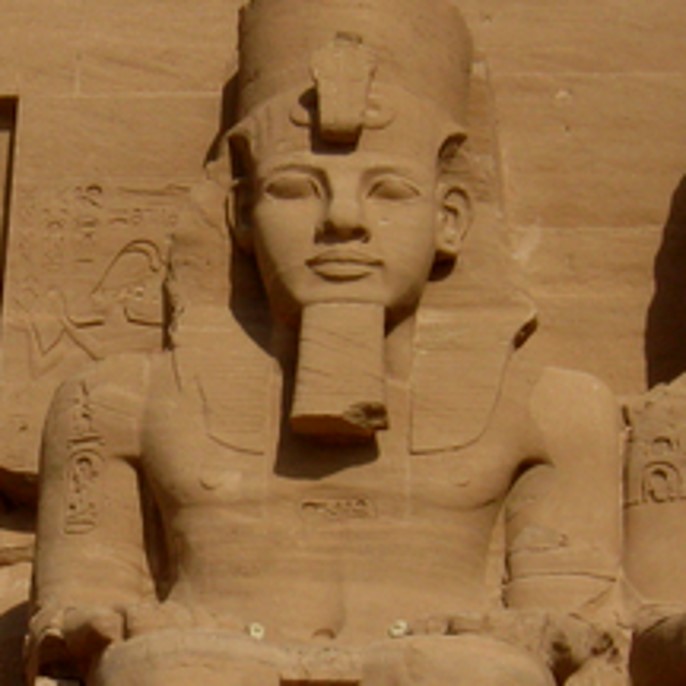

So if, in 1800 BCE someone in the Middle Kingdom of Ancient Egypt could write something that so obviously undermined theocratic despotism, what happened? Why aren’t we reading about the triumph of liberty, equality, and fraternity in the Middle Kingdom, of a collective revolution that began in 1789 BCE with the storming of the bas – the bas – the basalt – uh – temples of Ahmenemhet IV? Well, there are plenty of answers, but maybe the simplest one is the best. The world hadn’t known organized democracy yet. Archaeological remnants of minimally militarized, relatively egalitarian societies have been found from around the same period in coastal Peru and the Indus Valley, but the Egyptians didn’t know these. A society governed by egalitarian jurisprudence like the one we glimpse in Khunanup’s speech in “The Eloquent Peasant” would be a long, long time in coming. Still, the tattered papyrus of Khunanup is in many ways far more impressive than the vast temples of say, Ramses II at Abu Simbel or Qurna. Kings had built droves of grand temples, statues and earthworks. But the idea of egalitarianism and lower class dissent, of a persistent commoner who could make an agent of the pharaoh himself back down – in the historical record, at least – this is something new. [music]

Moving on to Ancient Egyptian Wisdom Literature

Let’s go full circle. The literature of Ancient Egypt helps us get a rounder picture of what life was like beneath the obelisks, and it helps us resist making generalizations about the way all people thought “back then.” Most scholars figure that Ancient Egypt had a literacy rate of less than one percent, and of course that one percent was the aristocracy and landed gentry that Khunanup rails against, and that the shipwrecked sailor story quietly fears. I think that makes it all the more telling that even though the surviving body of Ancient Egyptian literature that we do have is quite small, and even though it was crafted by scribes who had to work for wealthy patrons, it still reveals traces of dissent, disgust, and sadness at the economic imbalances of the state that lay along the Nile. Maybe this means that dissension, and a whole culture of political satire existed amidst the Egyptian masses – one that flourished in oral narratives, short plays, and folk songs, that’s been almost entirely lost to history.In the next episode, we’re going to look at a different side of Ancient Egyptian literature. While The Book of the Dead captures their religious beliefs, and the stories we explored in this episode may point to a hidden tradition of anti-monarchial rhetoric, a text called “The Instruction of Amenemope” will show you the secular ethical beliefs of the average Egyptian. “The Instruction of Amenemope” is part of a small but influential genre we’ll be dealing with a lot in this podcast, a genre called wisdom literature. “The Instructions of Amenemope,” the Books of Proverbs, the Wisdom of Solomon, and Sirach in the Bible, the Satires and Epistles of Horace, the Meditations of Marcus Aurelius, all the way down to the self help section of your local book store all contain various moments of pithy counsel and advice. In “The Instructions of Amenemope,” and a later text called “The Instructions of ‘Onchsheshonqy” you’ll be able to see that even though the Ancient Egyptians worshipped Ibis headed deities and buried themselves with jars of beer, the ethical approach they took to daily conduct was pretty close to the one we have today. Thanks for listening to Literature and History, try a quiz on Ancient Egyptian fiction on the website if you’d like, I’ve got a silly song coming up if you want to hear it, and otherwise, see you next time.

Still here? So, I got to thinking about Khunanup. I wondered, what if he were rushed forward, almost four thousand years, to our time. I think he’d probably enjoy many facets of modern life, like medicine, and air travel, and ice cream. But I think he’d be a bit disappointed, too, by the economic discrepancies of our times. I got to thinking – what kind of music would Khunanup play, if he were brought forward to modern times? Do we have a genre of music, like Khunanup’s speech, that expresses predominantly lower class dissent against the modern day aristocracy? Do we happen to have a whole system of music in which virtuoso lyrics are used, frequently, to capture the anger and ingenuity of the disenfranchised? Why, yes, we certainly do! And it’s called rap. I think Khunanup would make one hell of a rapper. This one’s called “The Eloquent Peasant Rap,” and it is, to my knowledge, the only rap song ever to be composed about Bronze Age Ancient Egyptian literature.

References

2.^ The Literature of Ancient Egypt. Ed. William Kelly Simpson, et. al. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2003, p. 47. Further references noted parenthetically.

3.^ Quoted in Budge, E.A. The Literature of the Ancient Egyptians. London: J.M. Dent & Sons Limited, 1914.

4.^ Ibid.

5.^ Wilkinson (2010), Location 1560.