Episode 11: Who Was Homer?

The Iliad, Books 17-24. As the Iliad reaches its spectacular climax, it’s time to ask a big question. Who wrote it?

| Read Transcription | References and Notes |

| Episode Quiz | Episode Song |

| Episode on Spotify | Episode on Apple Podcasts |

| Previous Show | Next Show |

Homer’s Iliad, Books 17-24

Hello, and welcome to the Literature and History, Episode 11: Who Was Homer. In this show, we’ll cover the last eight books of Homer’s Iliad, the Ancient Greek epic about the Trojan War. Then by way of finishing up the Iliad, we’ll talk about Homer himself – when and whether he existed, when and where the Iliad was created, and how it came about. If you want to hear the story of the Iliad from the beginning, it all started two episodes back in Episode 9. In Episode 9, I introduced all the main characters, and covered Books 1-8. Then in, in Episode 10, we went over books 9-16. Today, we’re finally going to wrap up the first of Homer’s two great epics.Where we last left off, the war was, yet again, at a bloody draw. Just as the Greeks were on the verge of total annihilation and the Trojans were burning their ships, the Greek champion Achilles’ closest friend Patroclus went to him. Patroclus asked the great warrior Achilles if he could wear Achilles’ armor into battle and lead their elite army, the Myrmidons, against the Trojans. Achilles gave his consent. And so, wearing the champion’s armor, Patroclus led a savage offense against the Trojans, pushing them back to the city of Troy. In a climactic moment, Apollo, who favored the Trojans, stunned Patroclus. Then Patroclus was speared by a Trojan warrior – a mortal blow. The Trojan champion Hector taunted Patroclus, who was not at all humbled by death. In fact, Patroclus knew that his death was the end for the Trojans, because Patroclus believed that when he died, the greatest warrior in the world, Patroclus’ dear friend Achilles, would come for the Trojans.

Now, on to the end of the Iliad. The very first line of the poem is, “Sing, Goddess, Achilles’ rage, / Black and murderous.”1 In the last eight books of the Iliad, we finally see the rage of Achilles in full force. The quotes in this episode, unless otherwise noted, come from the Stanley Lombardo translation, published by Hackett in 1977, although the book titles are taken from the Robert Fagles translation, published by Penguin in 1990. [music]

The Iliad, Book 17: Menelaus’ Finest Hour2

Patroclus had fallen. Menelaus, the former husband of Helen and brother of the Greek king Agamemnon, stood over Patroclus’ corpse. Menelaus defended Patroclus’ remains from a powerful Trojan, but soon saw that Hector and the entire Trojan army were coming his way, and retreated. Hector then stripped Achilles’ precious armor from the corpse of Patroclus, and prepared to dismember the body, but Menelaus had returned with giant Ajax and the two men defended the fallen Greek warrior’s remains.Hector’s men taunted him, telling him he should get back into the fight. The Trojan champion put on Achilles’ fine armor, and prepared for more fighting. But up on Olympus, Zeus shook his head. Hector had no business putting on Achilles’ armor, he said. It would be the end of Hector. Hector wife would never welcome him home. Feeling sorry for the Trojan champion, Zeus filled Hector with great strength one last time.

A violent skirmish broke out over the remains of Patroclus. Ajax and Menelaus fought in the center of the defending Greeks, and, joining forces, a knot of Greeks managed to fend off the rallying Trojans. A gray mist fell over the spot of turf where Patroclus had died, and the ground became dark with blood. The men fought until the living were soaked with sweat and their muscles slack with exhaustion. Achilles’ war horses wept at the sight of the warriors fighting for the body, and Zeus was moved to make one of the more famous statements of the Iliad: “Nothing is more miserable than man / Of all that breathes and moves upon the earth” (XVI.460-1).

Amidst the chaos whirling around Patroclus’ body, the Greeks discussed what was next. Menelaus told a Greek fighter to dispatch the message to Achilles that his dearest friend was dead, and the fighter ran to dispatch the news. And then, with great effort, the Greeks Menelaus and Ajax managed to secure their countryman Patroclus’ body. [music]

The Iliad, Book 18: The Shield of Achilles

The Greek messenger hurried through the battlefield, through smoke and din and screaming, past the Greek fortifications, and to the Greek encampment. There, he found Achilles, and he told the Greek champion the news. Achilles learned that his closest friend was dead, and that the Trojan champion Hector had stolen Achilles’ armor from the corpse of Patroclus. Achilles screamed. And when Achilles screamed, all of his concubines came out of his tent and beat their breasts, and the sound went down to the nymphs in the sea, who did the same thing.When Achilles’ mother Thetis came to him – she was a sea nymph, remember – she told Achilles that if he took revenge on Hector, he would die. Achilles welcomed it. Achilles said that it was his fault that Patroclus, and many other Greek heroes, were dead. He said didn’t deserve to go home, either. Achilles said,

[I] just squatted by my ships, a dead weight on the earth. . .Achilles’ mother Thetis said she knew she couldn’t change Achilles’ mind. She only asked him to wait a day, so that she could bring him new armor from the smith god, Hephaestus.

I wish all strife could stop, among gods

And among men, and anger too – it sends

Sensible men into fits of temper,

It drips down our throats sweeter than honey

And mushrooms up in our bellies like smoke. . .

But I’m going now to find. . .[Hector] (XVIII.109-112-116,120)

Meanwhile, the Trojans had caught up with the Greeks carrying Patroclus’ body, and a fight had erupted around it again. You kind of wonder how much of Patroclus was left by this time. Hector got hold of the body, and a messenger goddess came to Achilles. She told Achilles what was happening on the battlefield – Hector was going to take Patroclus’ body, and skin it, and put the head on the Trojan rampart. The messenger goddess told Achilles to go and take a look. But, said Achilles, he had no armor. It didn’t matter, said the messenger goddess. Just go and stand near the trench.

And so Achilles rushed out of the Greek earthworks and stood as he had been instructed. Athena put a nimbus of golden cloud around Achilles, radiant with moving fire. Achilles looked out on the battlefield, and he screamed. Everyone stopped, shocked. The horses winced. Achilles screamed twice more, and the Greeks were able to get Patroclus’ body to safety. Achilles wept over his friend, and the sun set slowly, “Its last rays touching the departing Greeks with gold. / It had been a day of brutal warfare” (XVIII.258-9).

That night, the mood was tense in the Trojan camp. Everyone knew who the man by the ditch was. Everyone knew what he was. One of Hector’s lieutenants counseled him to return to Troy, bolt the gates up, and make Achilles face their walls. But Hector disapproved. He’d had enough of being trapped in the city, he said. They’d fight at the ships.

Similar resolution filled the Greek camp. Achilles promised the fallen Patroclus that he would kill Hector, along with twelve Trojan princes, and the fallen warrior Patroclus was bathed and anointed, then draped in linen. [music]

This 490-480 BCE red figure kylix shows Hephaestus giving Achilles’ armaments to Achilles’ mother Thetis.

Hephaestus started with a shield – one with triple rims, and elaborately – I mean very, very, very elaborately decorated. Achilles’ shield showed the earth, sea, sky, and sun, the constellations, two full cities filled with miniature scenes, multiple armies, gods, a river, herds of livestock, farms, plowmen, a king, reapers, trees, a vineyard, herdsmen, dogs, a dance with carefully adorned dancers, acrobats, and a final giant river. The description is famous because each one of the things I just mentioned is carefully described, and there are many more I didn’t mention. It’s an instance of what’s called “ekphrasis,” or a lengthy literary description of a work of art – there’s a similar one of Enkidu’s funerary statue in the Epic of Gilgamesh, there’s one about Jason’s mantle in the Argonautica, one about Aeneas’ shield in the Aeneid, and in a separate tradition, the most famous one of all might be the prolonged description of the tabernacle in the Book of Exodus. Back to the Iliad, though.

Hephaestus finished Achilles’ inordinately detailed shield. Then Hephaestus made a breastplate, a helmet, and leg armor, and the gear was all ready for the Greek champion. Achilles’ mother Thetis hurried back to the Greek camp to give the great warrior his godly armor.

The Iliad, Book 19: The Champion Arms for Battle

At dawn, Achilles’ mother arrived at the Greek camp. Thetis told Achilles it was time to end his mourning, “And when she set the armor down before Achilles, / All of the metalwork clattered and chimed” (XIX.19-20). The Greek champion summoned an assembly, and told them that he would humble his pride, and that his quarrel with Agamemnon had done far more harm than good. He would fight with them. Everyone cheered. Agamemnon said he understood that no one liked him. Agamemnon acknowledged that he’d angered Achilles in a fit of madness brought on by Zeus, and of course a person couldn’t resist the gods. To repent, Agamemnon said, he’d take the treasure out of his ships that he’d been hording and divide it among all the men.Achilles said he didn’t care about treasure. It was time for war. Odysseus said they ought to at least wait until after breakfast to begin the fighting. Achilles said he wouldn’t eat until he was avenged. Achilles proclaimed, “Nothing matters to me now / But killing, and blood, and men in agony” (XIX.226-7). Doubtless, the words of a well-adjusted, psychologically healthy individual. Still, reason prevailed, and the treasures were doled out. Achilles continued to grieve for Patroclus. Though Achilles still refused to eat, Zeus sent Athena to him, who filled him up with ambrosia and nectar. Then, the remaining Greek armies began to assemble. Homer describes, in the HarperCollins Caroline Alexander translation, how:

from the swift ships the men poured forth;Upon mounting his chariot, Achilles heard one more dire warning. The gods would be with him for a little while longer, but his time to die had come. And Achilles said, “I know in my bones I will die here, / Far from my father and mother. Still, I won’t stop / Until I have made the Trojans sick of war” (XIX.451-2). [music]

as when thick-falling snow flies forth from Zeus above,

ice-cold beneath the blast of Boreas, the North Wind born of the high clear sky,

so then the close-pressed helmets gleaming bright

were borne forth from the ships, and the bossed shields,

strong-made breastplates and ash-wood spears.

And their gleam reached the heavens, and all the earth rang with laughter round them

at the lightning flash of bronze; thunder rose beneath the feet

of men, and in the midst godlike Achilles began to arm.

With a gnashing of his teeth, his eyes

shining like fire flare, and sorrow beyond endurance

in his heart, raging at the Trojans. (XIX.356-67)3

The Iliad, Book 20: Olympian Gods in Arms

As the Greeks and Trojans amassed for an apocalyptic final battle, Zeus summoned all deities to Olympus. And Zeus told them his plan. He’d just sit at Olympus and watch. He told them to go an ally themselves with whomever they wanted, because otherwise, Achilles would make mincemeat out of the Trojans, and it wouldn’t be much of a show.So on the Greek side were, as usual, Hera, Athena, and Poseidon. They were joined by the smith god Hephaestus and the swift god Hermes. On the Trojan side gathered the other usual suspects, Apollo and Aphrodite. They were joined by the god of war, Ares, and the archer goddess Artemis. And though the Trojans had lost their will to fight once they saw the incandescent Achilles, all of the massed gods spurred the armies into war with one another.

Zeus rocked the sky with thunder. Poseidon rattled the earth, until the mountains themselves shivered from their roots. Beneath the earth, Hades shrieked at the tumult, believing that the underworld would be torn open by the calamity. The gods paired off in single combat – Poseidon against Apollo, Ares against Athena, Hera against Artemis, and so on.

Apollo encouraged the Trojan hero Aeneas, son of Aphrodite, to fight Achilles, and the gods paused to watch the two men fight. The two men shared a – curiously lengthy series of remarks prior to the battle, Aeneas offering Achilles a nearly comprehensive autobiography in order to emphasize his aristocratic pedigree – later Romans, who saw Aeneas as their ultimate ancestor, loved this bit, by the way. Anyway, after a few more ripostes, Achilles and Aeneas began fighting. Even as the first spears were hurled, it was clear that Achilles had the advantage. And Poseidon decided to save Aeneas. The poor Trojan had been tricked by Apollo into fighting, after all. And so Poseidon swept Aeneas up in mist, and, for the second time in the Iliad, Aeneas, the future hero of the great Roman epic, the Aeneid, was whisked away to safety, although he quickly went back into a different part of the fray. We’ll see you in a few hundred years in the Aeneid, Aeneas.

Achilles, at this point, was in the battle with full force, now. He killed half a dozen people in spectacular ways, and then he saw Hector. Achilles screamed, “Here he is, the man who has reamed my heart, / Who has killed my noble friend” (XX.439-40). Side note, by the way, sorry. For some reason, no one seems to remember that the person who actually killed Patroclus at the end of Book 16 was not Hector, but instead a minor Trojan character named Euphorbus. All Hector did was taunt the dying Patroclus and then filch his armor. Anyway, Achilles saw Hector and called him “the man. . .Who has killed my noble friend,” and Hector said he wasn’t a bit afraid. Spears were hurled, but as Achilles bore down on the Trojan champion, Apollo swirled fog around Hector and moved him to safety.

Achilles spat and cursed and resolved that Hector wouldn’t survive another encounter with him. In the mean time, Achilles had plenty of people to kill. Achilles killed with his spear and sword. Achilles stabbed a man so hard his victim’s liver flew out, decapitated another one so forcefully that bone marrow spurted up into the air, and the ground beneath Achilles, and his hands and chariot, were all black with blood. [music]

The Iliad, Book 21: Achilles Fights the River

His rage in full force, Achilles divided up the Trojans and chased many of them into the river Xanthus. As they floundered in the water, he slaughtered them. His limbs became exhausted from all the fighting, and he captured twelve Trojan boys and had them led back to the Greek ships – boys who would be sacrificed for the sake of Patroclus.

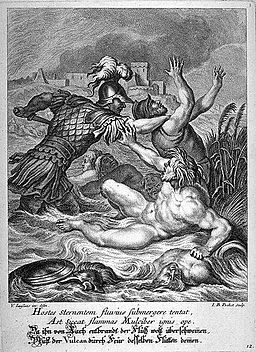

Achilles fights by the river in this 18th-century engraving by Johann Balthasar Probst (1673 – 1748).

The river Xanthus made a wall of water form around Achilles, and washed his victims back onshore. But Achilles dashed out of the water and back onto the Trojan plain. The river pursued him. It smashed into his shoulders, it pooled around his legs and dragged the earth from under his feet. Finally, Achilles prayed to Zeus, and Poseidon and Athena came to his aid and the river receded. The whole Trojan plain was now littered with drowned bodies, and bronze gear gleamed under the darkening afternoon.

The river Xanthus called to its brother, the river Simois, telling it that they must destroy Achilles, this impetuous man who acted like a god. They would bury him, Xanthus said, and his fine armor would be lost amidst mud and slime. The river surged, and, filled with logs and debris, prepared to crush Achilles. But Hera came to his aid. She told the smith god Hephaestus to light up the riverbanks with a mass of fire, and as the fire surged, the bright water began evaporating. Hephaestus’ fire intensified. All along the riverbanks the plants burned, and the fish felt the flames, and the heat increased until the river itself burned. The river Xanthus begged mercy from Hera and Hephaestus, and they relented.

Meanwhile, elsewhere, all over the battlefield the Gods squared off in combat, and Zeus laughed in amusement as their fights unfolded. Ares and Athena fought, and Athena clubbed him with a giant stone. Aphrodite attempted to lead the wounded Ares from the battlefield, but Athena intercepted her and punched her in the breast. Aphrodite and Ares toppled to the ground, and Athena taunted them.

Then Apollo and Poseidon, after debating about it, decided there was no reason to fight. Hera and Artemis, however did not feel the same way. They squared off, and Hera beat Artemis until arrows toppled out of her quiver. Artemis turned and fled, going to cry at the feet of Zeus. The gods returned to Olympus, some victorious, and some defeated.

On the battlefield, Achilles continued to dispatch men and horses alike. The Trojan king Priam saw the violence and said to hurry and get their armies inside the wall. A Trojan warrior, with the aid of Apollo, challenged Achilles. The Greek champion bested him, but Apollo spirited the warrior away in a shower of mist before Achilles could finish his opponent. Then Apollo disguised himself as the Trojan warrior, letting Achilles chase him from the battlefield. With Achilles gone, the Trojans were able to pour back into their city, and toward momentary safety. [music]

The Iliad, Book 22: The Death of Hector

Homer begins this book of the epic with the words “Everywhere you looked in Troy, exhausted / Soldiers, glazed with sweat like winded deer, / Leaned on their walls, cooling down / And slaking their thirst. / Outside, the Greeks / Formed up close to the wall, locking their shields” (XXII.1-5). Achilles left off chasing the disguised Apollo, and he ran straight for Troy. The old Trojan king Priam saw him coming.The Trojan champion Hector prepared for the fight. Priam spoke with his oldest son. Priam said, “Hector, my boy, you can’t face Achilles / Alone like that, without any support – / You’ll go down in a minute. He’s too much / For you, son, he won’t stop at anything” (XXII.45-8). Priam lamented all the sons he’d lost in the war. He asked Hector to stay in the city and help defend it. The Greeks would enter, and rape, and kill the city’s infants. And he, Priam, would die a death without dignity, an old, helpless man, mauled by dogs. Hector’s mother pleaded with him not to go. But Hector, ignoring their advice went out to face the Greek champion Achilles.

A moment later, Hector watched the approach of Achilles. He couldn’t stand down, he thought. It had been a mistake to meet Achilles in the open – his own mistake – and his men had paid dearly for it. If Hector hid behind the walls, he’d only earn the resentment of his men, because he’d made them face Achilles on the plains. He considered meeting Achilles unarmed and trying to broker peace. But he knew Achilles would just murder him. He would have to fight.

Achilles was almost within the distance of a spear throw, and seeing his giant adversary, Hector lost his nerve and ran. Achilles followed close behind, and the two of them, from the heights of the walls, appeared like a falcon and a dove. They passed numerous landmarks familiar to the Trojans, until

They came to the wellsprings of eddyingI’ll pause here for just a minute and say once again that often at the most climactic and bloody moments of the Iliad, Homer creates similes and set descriptions that reference peace time, harmony, and an honest day’s work, and that, as in this famous and obvious case, such references to an elusive peace make the horror of warfare all the more piercing to the poem’s reader. We’ll talk more about this soon. To return to the story, the two men passed the cool springs, and continued. They ran a circuit around the city three times.

Scamander, two beautiful pools, one

Boiling hot with steam rising up,

The other flowing cold even in summer,

Cold as freezing sleet, cold as tundra snow.

There were broad basins there, lined with stone,

Where the Trojan women used to wash their silky clothes

In the days of peace, before the Greeks came. (XXII.178)

Peter Paul Rubens’ Achilles Slays Hector (c 1630-5) shows both the persistent intervention of Athena in the combat as well as the defiant strength of the great Trojan champion in his final moments.

Athena came to Hector in the form of one of his brothers and told him it was time to fight the Greek champion. Athena promised Hector – falsely – that Hector brother would help. And so, filled with specious courage, Hector prepared to fight. Hector proposed to Achilles that whoever won the fight would honor the other’s corpse.

Achilles was not interested. He said, “Don’t try to cut any deals with me, Hector. / Do lions make peace treaties with men? / Do wolves and lambs agree to get along? / No, they hate each other to the core, / And that’s how it is between you and me” (XXII.287-91). With this, he flung his spear at the Trojan champion. Hector ducked, and the spear rammed into the earth behind him. Hector laughed at Achilles, and hurled his own spear. The weapon struck Achilles’ mighty shield squarely, and was deflected. Still believing his brother was with him, Hector requested another spear, and heard – nothing. He realized was alone, and death had come for him. And he said “Well, this is fate, / But I will not perish without doing some great deed / That future generations will remember” (XXII.331-3). Hector unsheathed his broadsword. The heroes charged one another. Hector wore Achilles’ armor – the armor that he’d stripped from the fallen Patroclus, and Achilles knew the armor’s weak spot – just near the collarbones.

It was there that he struck, wounding Hector mortally, and the great Trojan champion finally crashed down into the dust. Over his fallen adversary, Achilles exulted. Hector had made a big mistake in killing Patroclus and tearing off his armor. Achilles gloated, “[N]ow, I have laid you out on the ground. Dogs and birds are going to draw out your guts” (XXII.371-2). It was the worst fate a hero could have. Hector begged Achilles to reconsider, offering a great ransom. For the sake of his own parents, Achilles would reconsider, wouldn’t he? And Achilles responded with one of the darkest speeches in all literature.

Don’t whine to me about my parents,Hector presaged an equally dark fate for Achilles, and then the Trojan champion died. The Greeks mutilated his remains with their spears, gloating that the man who had burned their ships the day before now lay at their feet. Achilles, his violence unrelenting, pierced Hector’s heels and tied leather tongs through them, so that he could drag the man’s corpse, face down, behind his chariot. [music]

You dog! I wish my stomach would let me

Cut off your flesh in strips and eat it raw

For what you’ve done to me. There is no one

And no way to keep the dogs off your head,

Not even if they bring ten or twenty Ransoms. . .

No, dogs and birds will eat every last scrap. (XXII.383-9,93)

At the sight of their champion Hector’s death, the resolve of the Trojans broke. They wept and tore at themselves. Old King Priam said that grief would kill him. Hector’s wife, who had been preparing a bath for her husband’s return, heard the wailing and she ran to the ramparts, just in time to see her Hector’s remains being torn behind the chariot. Andromache was broken, not only at the loss of such a great, selfless champion of the city, but also at the thought that her baby son would grow up an orphan. In a moment of utter tragedy, thinking that they wouldn’t even be able to bury him, Hector’s wife Andromache thought of his clothes.

Your clothes are stored away, [she said,]Book 22 of the Iliad ends with the Trojan women weeping for their fallen hero. [music]

Beautiful, fine clothes made by women’s hands –

I’ll burn them all now in a blazing fire.

They’re no use to you, you’ll never lie

On the pyre in them. Burning them will be

Your glory before Trojan men and women. (XXII.569-74)

The Iliad, Book 23: Funeral Games for Patroclus

Back in the Greek encampment, at Achilles’ bidding, the Greek warriors circled their horses around the fallen Patroclus. Achilles flung Hector’s corpse low before the bier of Patroclus, by way of offering. Then, the men removed their armor and made many animal sacrifices for Patroclus. In the dark of the night, when Achilles finally fell asleep, he met the spirit of Patroclus. He tried to embrace his friend, but Achilles’ arms were only filled with smoke.The next day large quantities of wood were cut to serve as Patroclus’ funeral pyre. More animals were ritually killed, and food and oil were set on the pyre too. Then, Achilles gathered the Trojan boys he’d captured at the river and cut all of their throats. With some difficulty, the fire was lit, and once it was lit it roared and roared, all through the night. The following morning dawned bright, and Patroclus’ bones were put into a golden bowl. It was time for funeral games. Funeral games, by the way, are an epic convention, allowing poets to create a denouement after an important event by narrating some striking athletic set pieces, like footraces, javelin and discus throwing, wrestling, and that kind of thing. If we read the Iliad, the Aeneid, and the Thebaid from cover to cover, the funeral games portions of these stories seem narratively odd, occurring, as they do, in the midst of wars and perilous journeys.4 Don’t epic heroes want to conserve their strength, we wonder, for the real fighting and trials ahead, rather than suplexing one another and exhausting themselves on the racetrack? The answer to the question is, logically, yes, but we have to remember that these ancient epics were publicly performed to music, and a funeral games chapter would have been a self-contained sung narrative of perhaps an hour in length, in which many of the main characters of a greater epic appeared and demonstrated their excellence in various sports and feats of strength, maybe even encouraging some ancient Greek party guests to have another cup of wine and try their own hands at wrestling one another.

Well to return to the story, to kick off Patroclus’ funeral games, Achilles brought treasures out from his ship as prizes. The first competition was a chariot race, which Diomedes won. The second was a boxing match. The third was a wrestling match. Ajax and Odysseus went at it for so long that Achilles had to break them apart. Next was a sprint, which Odysseus won with some help from his patron goddess Athena. Next was a bout with real weapons – whoever first drew blood would win – and Diomedes won this. Then, there was a contest to throw a large lump of iron, a contest with archery, and a contest to throw a spear the farthest. The Greek warriors hurled themselves into the funeral games all day, filled with the same drive to distinguish themselves that they had in warfare. Excepting a few brief spates that Achilles settled, the games proceeded peacefully and fairly, fine prizes going to the best contestants. Let’s move on past the funeral games, though, and into the final book of Homer’s Iliad. [music]

The Iliad, Book 24: Achilles and Priam

That night, after the funeral games, Achilles lay awake, still thinking of the fallen Patroclus. Achilles was still not reconciled to his friend’s demise, and Achilles had continued to drag Hector’s corpse around the Greek camp. Hector’s remains were, however, protected by Apollo, so that Hector remained undefiled in spite of Achilles’ mutilations. Twelve days of this passed, and finally, Apollo went to the other gods. Apollo told the other gods that Hector had been good to all of them, and that his remains should be returned to Troy to console his family. Apollo told them that Achilles’ pride and rage were unacceptable. Apollo said, “Achilles, has lost all pity and has no shame left. / Shame sometimes hurts men, but it helps them too. / A man may lose someone dearer than Achilles has, / A brother from the same womb, or a son, / But when he has wept and mourned, he lets go” (XXIV.48-52).The gods agreed that Achilles was overdoing it. And Zeus formed a plan. Achilles’ mother Thetis would tell Achilles to accept a ransom from the Trojans for the corpse of Hector. And at the same time, a messenger goddess dispatched in the opposite direction would go to the Trojans, and instruct them to send emissaries with the aforementioned ransom.

Achilles’ mother Thetis, as she had been instructed to by the gods, told her son it was time to accept a Trojan ransom, and Achilles said that he would concede, since it was the will of the gods. Within the walls of Troy, old King Priam was told by a divine messenger to go and make the request of Achilles – all alone, with only a cart driver to bear him there. Priam’s wife was skeptical of this venture, but Priam insisted. Soon, old Priam was packing a hoard of treasures to take to the Greek champion. In spite of the Greek massacre of so many of Priam’s sons, a number of them were still alive, and Priam told Paris and his brothers that with Hector and his other stronger boys gone, “all I have left / Are these petty delinquents, pretty boys, and cheats, / These dancers, toe-tapping champions, / Renowned throughout the neighborhood for filching goats!” (XXIV.277-80). Priam made the smattering of his surviving sons get his cart ready for its short journey. Then, with a prayer to Zeus, Priam departed.

Zeus heard the prayer and he sent a god down to enshroud Priam, so that the old Trojan king could get all the way to Achilles without being detected. On the way there, the god pretended to be one of Achilles’ men, and when asked, told Priam not to worry – his poor son’s corpse was still intact, in spite of the Greeks abusing it. Hector’s body was protected by the gods.

And so the god in disguise brought Priam through the Greek earthworks, through their camp, to the door of Achilles’ hut, and then took his leave. Old King Priam stood there alone, ready to supplicate himself – to beg from the man who had killed many of his sons. Priam entered unnoticed, just after an evening meal, crept over to Achilles, and knelt at the killer’s knees, kissing the Greek champion’s hands. Achilles looked up in wonder at the sudden appearance of the Trojan king in his tent. And Priam said, in the Caroline Alexander translation,

Remember your father, godlike Achilles,It was a speech made from a place of utter humiliation, an admission of hopelessness and vulnerability, and an attempt to show the remorseless Greek champion that all men had fathers, and that fathers and sons needed another. In an epic so full of muscle bound goliaths killing one another out of egotistic one-upmanship, Priam’s speech is something sacred – a sort of hymn of hope for the ultimate similarity of every human being beneath the passing feuds of clans and civilizations. And it broke Achilles’ heart, ending, finally, the wrath that Homer describes in the first line of the Iliad. Following Priam’s speech, the two men, suddenly overcome with sympathy and mutual understanding, began to cry together. Homer writes, in the Lombardo translation,

The same age as I, on the ruinous threshold of old age.

And perhaps those who dwell and surround him and

bear hard upon him, nor is there anyone to ward off harm and destruction.

Yet surely when he hears you are living

he rejoices in his heart and hopes for all his days

to see his beloved son returning from Troy.

But I am fated utterly, since I sired the best sons

in broad Troy, but I say not one of them is left. . .

he alone was left to me, he alone protected our city and those inside it,

him it was you lately killed as he fought to defend his country,

Hector. And for his sake I come now to the ships of the [Greeks]

to win his release from you, and I bear an untold ransom.

Revere the gods, Achilles, and have pity upon me,

remembering your father; for I am yet more pitiful,

and have endured such things as no other mortal man upon the earth,

drawing to my lips the hands of the man who killed my son. (XXIV.486-94,499-505)

The two of them remembered. Priam,Achilles said he would release the body. He’d had a message from the gods, too. Hector’s body was cleaned and anointed, and Priam’s treasure was unloaded. Achilles told the old Trojan king that at dawn, Hector’s body would be taken back to Troy, and that Priam had best stay in Achilles’ hut, for his own safety, for the night. The two men shared a meal, mostly silent, but as it drew to an end they took measure of one another, Priam gazing with awe on Achilles’ great strength, and Achilles with reverence on Priam’s wisdom and composure even in the midst of the old man’s devastating grief.

Huddled in grief at Achilles’ feet, cried

And moaned softly for. . .Hector.

And Achilles cried for his father and

For Patroclus. The sound filled the room.

When Achilles had his fill of grief

And the aching sorrow left his heart,

He rose from his chair and lifted the old man

By his hand, pitying his white hair and beard.

And his words enfolded him like wings:

“Ah, [Achilles said,] the suffering you’ve had, and the courage.

To come here alone to the Greek ships

And meet my eye, the man who slaughtered

Your many fine sons! You have a heart of iron.

But come, sit on this chair. Let our pain

Lie at rest a while, no matter how much we hurt.

[My father – ] I can’t be with him

To take care of him now that he’s old, since I’m far

From my fatherland, squatting here in Troy,

Tormenting you and your children (XXIV.547-63,582-4).

Alexander Andreyevich Ivanov’s Priam Begging the Body of Hector from Achilles (1824). Ivanov’s depiction shows Achilles’ initial standoffishness, prior to the heartbreaking moment at the climax of the Iliad during which the two men share an essential human connection in spite of the unending war.

Not long afterward, in the darkest part of night, the god who’d escorted Priam into the camp told Priam he’d best get going. Casting a spell over the Trojan king, his mule, his cart, and his dead son, the god brought Priam safely back to Troy. There, the citizens saw their hero’s remains and grieved. Priam pulled the Trojan hero through the gates, and the mood was not optimistic. Hector’s wife Andromache looked at Hector’s dead body and prophesied grim things. Troy would fall. She and the other Trojan women would be carried off in ships. Andromache foresaw that her son would be tossed from a tower. Hector’s mother lamented his passing, and then Helen, who had special words for her departed brother-in-law. Hector’s people had taken her in, Helen said, in spite of the danger to them, and had never given her an unkind word – not once. It was she who deserved to be dead – not Hector.

The Trojans spent nine days bringing lumber into the city for the funeral pyre, knowing the Greeks would not strike due to the armistice. On the morning of the tenth, they put Hector on the pyre and ignited it, and “Light blossomed like roses in the eastern sky” (XXIV.845-6). That day, the Trojans built Hector’s tomb as quickly as they could, in case the Greeks struck early. And the Iliad ends with these words: “When the tomb was built, they all returned / To the city and assembled for a glorious feast / In the house of Priam. . ./ That was the funeral of Hector, breaker of horses” (XXIV.857-60). [music]

Who Was Homer: An Introduction

It’s a very moving ending, but you might be saying to yourself, “What?” or perhaps, “Eeh?” or, “That’s the end?” “Wasn’t there – like – a horse?” Or, “What about Achilles’ Achilles heel?” Or, “So, uh – who won the Trojan War?” All very reasonable questions, and the answer, as you maybe recall from our earlier episodes on the Iliad, is that the Iliad is the second book in a massive, eight book long cycle, out of which we now only possess the second and seventh installments. Originally, after the Iliad, there followed a poem called the Aethiopis – this was a story about distant Trojan allies, including Amazonian women, coming to Troy after the death of Hector to help Troy out, and in the midst of the Aethiopis, Achilles is killed by an arrow from Paris while leading an assault in the newly bolstered Trojan defenses. Book 4 of the mostly lost Epic Cycle, following the Aethiopis, was a shorter work called the Little Iliad, which detailed a large scale contest in the Greek camp for the arms and armor of Achilles, the arrival of Achilles’ son at the war, and the construction of the Trojan Horse. Book 5, the Iliou Persis, or “sack of Troy” was about Troy finally being crushed by the Greeks after the successful use of the Trojan Horse. Book 6, the Nostoi, covered the returns of the Greek brothers Menelaus and Agamemnon to their respective homelands of Sparta and Argos. Book 7 was the Odyssey, which we’ll read next in this podcast, and which, conveniently, retells some of the lost portions of the Epic Cycle. And Book 8, the Telegony, was about Odysseus’ adventures after he returned to Ithaca and retook his homeland.5I’m doing my best to give you a general sense of Homer’s style, its darkness and its beauty, and the events of the Iliad. And I hope that I’ve been able to convey, at least to an extent, the incredible power and grace in the most famous scenes in the poem – like the early fight between Menelaus and Paris, the savage violence at the Greek rampart, and poor old Priam kneeling in front of Achilles and finally managing to make the ruthless killer understand the human cost of the campaign on which Achilles has embarked. Still, as with all the authors we’ll cover in this show, to get the full octane of Homer’s power, not to mention the extraordinary talent of Stanley Lombardo, Robert Fagles and Caroline Alexander, the authors of the three translations I’ve quoted from, I encourage you to get a hold of the Iliad itself. If you’ve listened to the last three shows, you’ll devour that sucker.

Anyway, let’s move onto the big question. Who was Homer? Who wrote this story that you’ve been listening to, over the course of several hours, over the last three episodes? Who created Helen, and Achilles, and Hector? Who wrote a poem so filled with violent, lusty gods and mortals who suffer at their whims? Who wrote a later poem, in which a crafty maritime adventurer travels home, which you’ll hear about over the next three programs?

I wish I could tell you that we have ample contemporary documentary evidence that all the legends are true: a blind poet who lived in the west of modern day Turkey wrote all of it. Wish I could say that a profoundly brilliant man named Homer just sat at a table during the autumn of 725 BCE, clenched his teeth, and made up the Iliad. That this singular Homer, from the bottomless profundity of his imagination, had it all occur to him in a flash of brilliant synthesis, maybe with the aid of a goblet of some of that Ancient Greek cheese barley wine. And then, that what he wrote down was diligently copied, and then sealed in stone time capsules and simultaneously distributed to every single individual in the Greek speaking world. And you can now buy at the book store that’s a precise translation of what that blind poet of the eastern Aegean wrote, in a moment of revelation, in 725 BCE.

I wish I could tell you all of that, but none of it is true. We have no contemporary records of a person named Homer, nor a Greek public quickly becoming enchanted with his singular writing. We’re not certain about when the historical Trojan War happened, or what was really at stake. Ancients and moderns alike have generated a wide array of theories about who Homer was. Readers of the Iliad have proclaimed that Homer was not a Greek poet but a Sicilian Girl, that he was Swedish, English, Ancient Egyptian, and that Homer’s Aegean was actually the west Atlantic. Multiple sources, including a ninth-century CE life of Homer, quoting from a lost book by Aristotle, argue that Homer was born when a spirit that danced with muses coupled with a Greek girl, and so he was half Greek, and half pure poetry. Other biographical fragments construe Homer as an outsider, sometimes a tragic outsider.

The problem is that the information we have on Homer often takes the following form. A medieval Islamic transcription of an Alexandrian manuscript of a set of commentaries on a lost book on Aristotle reports that an unidentified man who lived two hundred years after Homer repeated reading another chronicler’s work that Homer spent part of his life on the island of Chios. Okay. While you can’t count such information useless, the twists and folds in the factoid’s journey toward the present make it highly suspect. You know the game of telephone. You whisper “Homer” into your neighbor’s ear, and she hears “home,” and then her neighbor hears “who,” and the next person hears “whoops.” From Homer to whoops in just ten seconds. When not ten seconds, but 2,700 years have passed, and many of the whisperers have had personal interest at stake, well – you get the picture. You have a lot of whoopses, and maybe – just maybe – a few Homers. [music]

Eastern Cities and Western Invaders: The Iliad and the Bronze Age Collapse

As with a lot of ancient literature, the origins of the Iliad and Odyssey are obscured by time. What we have to work with is hearsay, copies of copies, the textual details of the poems themselves, and a fair amount of ancient art – etchings, pottery, mosaics, and so on, that appear to depict scenes from the Homeric epics. From this evidence, generations of linguists, archaeologists and art historians have reached a few conclusions. The first conclusion is that we shouldn’t be asking who the author of the Iliad and Odyssey was. We should be asking who the authors were.The two poems are now generally thought to have been produced by multiple centuries – maybe even a thousand years – of oral tradition woven around that wider set of myths and legends called the Epic Cycle which we discussed a moment ago. The cycle was formative to the works of both Hesiod and Homer. While the Epic Cycle is now almost entirely lost, we possess enough information about them to understand that the Homeric poems did not appear suddenly in the mind of some blind genius. If you’ll remember, going back to episode 9, Homer begins the first book of the Iliad in the ninth year of the Trojan War. Helen has already been stolen by Paris. Agamemnon, Achilles, Nestor, Thetis, and various gods are all brought in with no introduction. The assumption is that you’re already up to speed with the story of the war, you know all the major players, and you’re ready for a rollicking recitation of some of their most central words and deeds.

And I did say “recitation.” We’re still a couple thousand years away from the moment when lengthy, mechanically reproduced manuscripts could find their way into the hands of literate masses. The Homeric poems, written in the mostly dactylic hexameter we discussed a few episodes ago, were oral tradition. And oral tradition, for there to be a tradition, had to be collective.

So with all this said, I can give you what’s currently the most common theory on the authorship of the Homeric poems.

First, there was in the ancient Aegean world a narrative tradition of writing about invading armies laying siege to cities. In these narratives, a mobile, warlike band of adventurers attacks a more settled urban center for the sake of plunder, enslavement, and rape, just as the wandering, mostly male Greeks attack and massacre the affluent, family centered city of Troy. This narrative tradition was likely the result of two cultures that clashed in the Ancient Aegean – the Indo-European steppe people who had descended from the Eurasian grasslands by 1700 BCE, who would become the Greeks, and the urban, commercial societies of Crete, Ancient Egypt and Asia Minor. This is the story that plays out in the Iliad, and in two other ancient poems – the Thebaid and its successor the Epigoni. Wandering marauders seek the spoils of war, and city dwellers die defending their landed lifestyle. The Iliad is in some ways the story of the Bronze Age Collapse in miniature.

This core narrative – that of marauding invaders kicking down the walls of settled towns and cities – is essentially the story of a real cultural encounter. The people of the Eurasian steppe lands really did meet the older landed civilizations, and fought and integrated with them. The events of the Trojan War – a band of disparate, violent, profiteering males sacking a wealthy trading hub – was par for the course in Ancient Greece during the years between 2,000 and 1,000 BCE. There were many, many Trojan Wars, and many stories and legends about them.

A photo of the archaeological site of Wilusa in the northwestern Turkey, a couple of miles inland from the mouth of the Hellespont, usually identified as “Troy.” Photo by Jorge Láscar.

Excavations at the Troy dig site began in 1865. Different cities were discovered in different layers. The earliest layer spanned the years from 2400-1800 BCE. This was the estimated date of the Trojan War given by Heinrich Schliemann, a 19th-century German archaeologist central to the early Troy excavation as famous as he remains controversial. The wealth that Schliemann found in this layer, and the cloth manufacturing equipment, led Schliemann to conclude that the textile-rich Troy of Homer’s poem was the oldest layer of the city he’d excavated. Andromache, Hector’s wife, after all, says just after Hector dies, “there are clothes laid aside in the house, / finely woven, beautiful, fashioned by the hands of women” (XXII.510-11).6 The Trojans in Homer’s poem weren’t exactly running around in sackcloth.

Later archaeologists disagreed with Schliemann about the Trojan taking place way back in 2000 BCE. A new date of 1300 BCE was proposed. An archaeologist discovered that a wall ringing the city had a weak spot, just like Homer’s Troy was reported to have. Later, the date was changed to 1200, as different layers of the ancient city were excavated. The later date – 1200 BCE or just after – was settled on, when remnants of fire and violence were discovered dated to about 1184 BCE. This date was even in line with the theory of the great fifth-century BCE Greek historian Herodotus, and it’s still the most common date associated with the historical Trojan War – again 1184 BCE – notwithstanding some compelling contrary theories. Now, the historical Troy was probably a part of the Hittite Empire of present day Turkey – a client or vassal state. And there’s little reason to suppose that the historical Trojans spoke Greek, or were ethnically Indo-European. So, it follows that we don’t have any historical records or archaeological evidence of an articulate Greek speaking Trojan Hector, who issued lengthy challenges to marauding armies from the west, or any other archaeological evidence of any figure in the Iliad, whatsoever. Not one.

Using the Iliad‘s Many Objects to Date the Poem

So far, then, all I’ve told you that we know with certainty is that violent city sacking stories were common in the pre-Homeric world, and Troy was very likely a real place, that Troy, or the Hittite city Wilusa, at least, really was leveled – perhaps in about 1184. But fortunately for us, archaeology onsite at Troy has been just a small part of investigating the origins of the Homeric poems.Another tool way we’ve investigated the origins of the Homeric poems has been carefully examining the vast catalog of objects in the Iliad and Odyssey and comparing them to archaeological finds throughout the Aegean world. For instance, several of the poem’s characters, including Agamemnon, carry silver studded swords. These were rarely found after 1500 in Mycenaean Greece. Similarly, the vast tower shield of Ajax, described at several points, is also an anachronism if we accept 1184 as the date of the Trojan War, as such shields had fallen out of use over a hundred years before 1184.7 And, a leather helmet, carefully stitched and gleaming with boar teeth, described in Book 10, is just as out of place, similar ones having been found in Crete and Mycenaean dig sites, but never ats Troy. Shields like Achilles’ shield, on the other hand, with circular rings of narrative stories, can’t be found in dig sites older than the 600s BCE. These three examples alone don’t do much to challenge the 1184 date, but careful investigations into Homer’s heaps of weapons, chariots, architectural details and clothing have uncovered many similar anachronisms, to such an extent that an archaeologically informed reader of the Iliad feels like she’s reading a story about the Vietnam War, and some fighters are wielding muskets and wearing tophats and girdles, while others are brandishing machine guns and wearing combat fatigues. Perhaps the most emblematic example of these anachronisms is with iron. In Book 23, Achilles is offered a single piece of iron as a valuable prize during the games of Patroclus. But earlier, in Book 4, a Trojan archer has iron arrowheads, suggesting that iron is commonplace. Either iron became rare and precious over the week or so covered in the Iliad’s books, or, it’s probably more reasonable to assume, different passages of this poem were produced at different times in Ancient Greek history.

So, certain objects in the Iliad suggest that while it may be generally about a Trojan War that happened around 1184, it borrows numerous episodes, equipment lists, characters, and scene descriptions from far earlier narratives. Simultaneously, other objects, like Achilles’ shield, point to a far later date. The Homeric epics also have a range of geographical knowledge that could not have come before 800 BCE, when Greek colonization had expanded to many of the new corners of the Aegean world visited by Odysseus.

The bottom line is pretty simple. The Homeric poems were almost certainly composed over long timeframes, and woven together by generations of performers. Just like an archaeological dig site, they have deep layers, that are oldest, and shallower layers, that are more recent. We know about the old layers from all of the antique objects catalogued in the poem – objects from the old world of Mycenaean Greek palace culture. And we know about the newer layers because Homeric geography suggests the expanded Greek world of the 700s BCE and perhaps even later, and some of the objects and artwork described in the poem seem to be of this vintage. But there have been other approaches used to date and understand the world of the Iliad – approaches that happen to be pretty easy to explain in podcast form. [music]

Metrical Analysis, Dating, and the Iliad‘s Authorship

Let’s say – just for kicks – let’s say you still want to believe that a single individual – a single Homer-Sapien wrote or composed the entire thing – in Homer studies this is called the unitarian approach. Let’s say that even though the Homeric poems are full of objects that are way out of place chronologically, you still want to make the case that in 725 BCE, a single individual sat down and put the whole thing together. One argument you could make would be that he or she knew a lot of old legends, and was perfectly willing to include ancient as well as modern weapons in his or her story about the war to end all wars. It makes sense. Only, besides archaeology and the object catalogs of the Homeric poems, we have another tool to investigate the origins of the Iliad and Odyssey.This tool is linguistic and metrical analysis. Now, this stuff is pretty new to those of us who haven’t been exposed to much poetry, which I imagine is most of us. I’m going to explain this to you using metered verse. Here goes.

POetic MEter is STUdied by SCHolars who CAREfully LOOK at it.You felt that, right – slightly exaggerated, but that last line fell out of step with its friends. Its friends were all in dactylic hexameter – the meter that runs most of a Homeric line. But that last line was a naughty boy. That last line marched to the beat of a different drum, put on a leather jacket, lit up a cigarette, and turned into trochaic pentameter. Ooooh. Well, when this happens in poetry, scholars investigate why. Metrical investigation of the Iliad has led Homer scholars to conclude that about 20% of the poem’s lines don’t fit correctly into Homer’s typical meter, but in many cases, if you use older variants of Greek words – words that come from a vintage of silver studded swords and tower shields, then the meter is consistent. This metrical analysis has led us to conclude that somewhere around 20% of the poem is older than 1400 BCE.

TYpically EVer-y LINE fits in TO the same STRUCTural PATTerning.

BUT sometimes A line falls OUT of the SEQuence which OTHers are FOLLowing.

AND when that HAPPens it SOUNDS so VERy STRANGE and UNexPECted.

In fact, a sizable amount of scholarship that went into investigating who Homer was has gone into thinking about the poems as oral traditions. In addition to noticing the metrical quirks I just described, investigators have tried to imagine how a single individual, or even a traveling troupe of individuals, could commit tens of thousands of lines to memory. By the time I went to school, memorization was not a big part of the curriculum. But generations of Russian schoolchildren have memorized Pushkin, Muslims have historically placed high value on committing the Qur’an to memory, and to use a pop cultural example, millions of us have stanzas and stanzas of lyrics of our favorite songs by rote. Memorized narratives were a big part of the entertainment industry in Ancient Greece, too. The question is how much, for instance, a recitation of Book 1 of the Iliad would be exactly the same from performance to performance, and how much components of it might be improvised.

The Iliad and Memorization

You or I might not be able to memorize the 27,803 lines of poetry that make up Homer’s epics. Not without some tools. But the Greeks of the 700s knew all about those tools. One of those tools was the meter we’ve been talking about – that predominantly dactylic hexameter. As I said in the episode on Hesiod, meter and rhyme help us memorize the information of a poem. You know that the line that follows “Peter peter pumpkin eater” is going to sound like DAH dah DAH dah DAH dah EE ur. Therefore, to recall the next line, you probably only need one word, maybe “wife,” to bring the whole unit up to your memory: “Had a wife and couldn’t feed her.” I know I’ve said this before, but when we in twenty-first century think that meter and rhyme exist just to be “flowery” or “decorative” we misunderstand their origins. Meter and rhyme exist for the storage and transmission of information. In the ancient world, they were not “flowery” or “decorative.” They were indispensible technical innovations engineered for the preservation and transfer of verbal data.Almost everywhere throughout the Homeric poems, the forty or so characters who return again and again have what are called epithets. If you’ve heard Richard the Lion Heart or Catherine the Great, you’ve heard epithets – compressed descriptive language that accompanies a name and tells you something about that name. In Homer, Achilles is often “swift-footed godlike Achilles” and Odysseus “much-suffering godlike Odysseus.” Dozens of these epithets exist in the Homeric poems. The epithets serve some obvious purposes. In the midst of a broad cast of characters, they remind us of who is onstage. And assuming that the massive Iliad, Odyssey and Epic Cycle were most likely recited piecemeal at festivals, the epithets also help you jump right into any given book and know, at a basic level, the characteristics of who’s being talked about. Even as a modern reader, these epithets are terrifically helpful. If you hear “mighty Diomedes” or “giant Ajax” you’re more likely to remember who these guys are.

But aside from being audience-friendly, the epithets serve an important metrical purpose. The Homeric Greek words for “much-suffering godlike Odysseus,” repeated thirty-eight times in the poems, are polytlas dios Odysseus. And for “swift-footed godlike Achilles,” the words are podarkēs dios Achilleus. Let’s hear those again. Polytlas dios Odysseus. Podarkēs dios Achilleus. Dactyl dactyl dactyl. Three dactyls. It’s half a Homeric line – remember that he and Hesiod both wrote in hexameter – six units per line. The great 20th century Homer scholar Milman Parry, reading and rereading the two epics, discovered that a little less than a third of their lines are – get this – repeated. Now, you notice this when you read them. Descriptions are reused – of the dawn, the sea, of a person’s agony upon their death in battle, similes, and of course the epithets. Fragments of the same speeches are found in multiple places. What the scholar Milman Parry concluded was that much of the Homeric epics were made of, to use another scholar, Adam Nicolson’s words, “prefabricated elements that had been evolved to fit the metrical pattern of the hexameter. Anyone telling the story of the Odyssey or the Iliad in verse would have had, ready to hand, words and expressions that could easily be put into this form” (77).

So, with epithets, a rock solid poetic meter, and a lot of transplantable elements, an Ancient Greek performer had a lot of tools at his or her disposal to keep huge amounts of poetry ready at hand for an audience. This ancient Greek performer might modify components of the poem from show to show, but the components would be the same – interlocking, metrically consistent language about the same essential core of characters.

It’s all pretty cool stuff. But how much can one person actually have memorized? Could there really have been one super-performer, perhaps from the west of Turkey, as some legends say Homer was, who synthesized a core part of a civilization’s narrative traditions, and put these into a single connected narrative, using his own distinct touches, who had the same name as a modern cartoon character who works in a power plant and eats pink donuts? Why yes, in fact. It is possible.

Not all of the research into Homeric authorship consisted of digging through rubble and studying ancient manuscripts. In fact, that very famous Homer scholar I mentioned earlier – Milman Parry – believed in a single composer had assembled the Iliad and the Odyssey. Where did Milman Parry go to gather evidence for his hypothesis? The ancient island of Chios, thought by many to be the ancient residence of Homer? No. Not Chios. What about Athens, where, by the 300s BCE, the Iliad and the Odyssey had the status of sacred scriptures? No. Not Athens. Milman Parry went to. . .Yugoslavia.

He had good reason to. In the early 1930s, the Homer scholar Milman Parry traveled throughout Yugoslavia to listen to over ten thousand separate songs sung by folk singers, and he began to understand how they could perform hours and hours of verbal material purely from memory. Parry and his scholarly successor, who listened to performers in Crete, noticed that folk singers used blocks of lines, repeated stanzas, and the same kinds of formulae found in the Homeric poems. This seemed to suggest that an experienced orator, working within the grooves of a familiar meter and making use of accustomed themes, could deliver massive quantities of partially improvised, partially memorized narration at will. What this great Homer scholar learned in Yugoslavia was that there might have actually been one person who could have performed the entire Iliad and the Odyssey. Later folklorists in the 1950s, studying storytellers who came from long pedigrees of storytellers, discovered something even more striking. A long culture of oral tradition seemed to be able to produce individuals who could recite tens of thousands of words from memory. It seemed that a singular Homer might be possible, after all. [music]

Evidence of the Iliad in Archaeological Depictions

But still, there were problems with the unitarian approach. Why would this singular Homer break his own meter in order to write lines that would fit if only they would use archaic word forms from a previous epoch of Greek civilization? Why would episodes – like the appearance of Achilles’ old tutor in Book 9, for instance – be both grammatically and thematically out of place? There are still what are called unitarians who believe in a single compiler or author for the Iliad and the Odyssey, but much more common view is that the Homeric poems had multiple authors, operating at different phases of Greek civilization, starting with the earlier Mycenaean palace culture of the Bronze Age, ending with the expanded colonizing Greek world of the 500s and 600s, and with the Trojan War of 1184 BCE squarely between them.This is the span of time that produced the Homeric poems, but it also produced a lot of related material. Earlier I mentioned the Epic Cycle – a group of poems that circulated widely in the world of Ancient Greece, predated the Homeric epics, and also postdated them. We have scant information on these poems – at best a Greek compiler from the 400s BCE who provides us with a summary of the Epic Cycle, and so it’s difficult to tell exactly what the Homeric poems took from them and what the Homeric poems invented. What we can do, though, is turn again to archaeology, and ancient art, for depictions of what are likely Homeric scenes, and what are scenes from other stories.

The artifact called Nestor’s Cup, discovered on the Magna Graecian island of Ischia, and dated to around 725 BCE. Photo by Antonius Proximo.

To return to the Epic Cycle, and its influence on Homer, alongside the pottery and other artifacts showing Homeric scenes, we’ve also found scenes of characters from the Iliad and Odyssey doing things that are not ever mentioned in these two surviving poems. There are many scenes of the Greek hero Ajax taking his own life. Others show Achilles’ father kidnapping Achilles’ mother from the sea nymphs. The death of Hector’s baby son at the hands of Odysseus is another common scene. We’ve even discovered many depictions of Ajax and Achilles together playing a board game. What all of these carefully dated scenes show is that Homer’s characters had an extensive life outside of the Iliad and Odyssey, and that even after the Homeric versions of these poems were born, people were still hearing about, writing about, and painting Achilleses, Agamemnons, and Odysseuses independently of Homer.

Throughout this series on Homer I’ve kept mentioning 725 BCE as the hypothetical date at which a hypothetical single individual wrote two epics in a burst of creativity. I’ve been doing this because of a broken wine cup. This wine cup was dug up on the island of Ischia, off the west coast of Italy near present day Naples. It was buried with the remains of a teenage boy, and it claimed – facetiously – to be the cup of the Greek hero Nestor. If you have a superhuman memory, and recall that cheese barley wine scene from Book 11 of the Iliad, which we covered last time, Nestor has a cup that’s very large. Nestor drinks from this cup, feels heartened, and tells a story. The cup from 725 BCE discovered in Ischia said, essentially, that it was Nestor’s cup, and that if you drink from it, you will be filled with the desire for Aphrodite. The real cup and its inscription are an irreverent joke on the cup of Nestor. They may, in fact, have to do with an earlier epic cycle tradition unrelated to Homer. But maybe not. The broken cup may exhibit an early example of a specific allusion to the Iliad in art, and so when scholars do their best to bookend the dates when the Iliad and Odyssey were produced, for a number of reasons, the late 700s BCE is often the period mentioned. [music]

Manuscripts and the Continuing Search for Homer

I haven’t even talked about manuscripts. All of this discussion has been about internal evidence within the poems themselves, and then archaeology and artifacts. We have papyrus scraps, fragments on broken pottery, and a lot of quotes in the writings of Plato, Aristotle, and other Greek writers. But the earliest hefty manuscript we have is from long, long after the 700s BCE, and it was found not in the Aegean, but in the tomb of a woman who died in about 150 CE, nine hundred years after the time when the Iliad and Odyssey were probably composed, in Egypt, just south of present day Cairo. This manuscript, a large scroll called the Hawara Homer, contains Books 1 and 2 of the Iliad, and was found being used as the deceased’s pillow, a sort of “Pilliad,” if you will. The pillow manuscript – the Hawara Homer – is similar enough to the later, larger manuscripts that have come down to us by way of the library at Alexandria, and thereafter the Byzantine Empire that we can generally conclude that by 150 CE, the Iliad and the Odyssey had reached a form similar to the one that we read now. As far as what happened in the 900 years before, between the Hawara manuscript and the legendary life of Homer, and what happened before that, in the remoter past of ancient, ancient Greece, we’re far less certain.I waited until we were through with the Iliad to bring up the subject of authorship because in Homeric studies authorship is one of the more frustrating, and more evasive subjects. I think that the processes we’ve used to pursue the question of authorship – metrical analysis, archaeology, art history, and linguistics are far more interesting than the fogbank we enter when we really try to pinpoint the authorship of the two epics and only find broken wine cups and echoes of echoes. While we have no certainty on the historical Homer, the energy with which we’ve pursued the question has hugely increased our knowledge of the languages of the ancient Aegean, of oral and folkloric tradition, and of the western settlements of the ancient Hittite empire. All of that is at least as valuable as knowing whether it was really just one guy or girl who strapped on a lyre and blasted out the Iliad and Odyssey, all by themselves, and then, by way of an encore, wrote them down, too.

The title of this episode is “Who Was Homer,” and it’s certainly been the main topic, other than the Iliad itself. One viable answer – the only answer available to us at present, as I think you’ve seen – is that Homer was many people. And I think the most magnificent things we’ve created as a species are group projects. Sit on the lawn at Canterbury Cathedral, and I doubt that you say, “Which man made this, and in which year?” Stand at the foyer in the British museum and look at the catalog of exhibits, and you can hardly ask, “Who is the man who made all this?” Or, stand on Navy Pier and look at the Chicago skyline on a summer night while the sun sets, and the lights are dazzling below on the waters of Lake Michigan, and I don’t think you’ll say, “Which man created that?” The only simplistic answer to such a simplistic question would be “We did.” And without wanting to sound too romantic, I think we can say the same thing about the Iliad. There might have been some individual who wrangled a huge amount of it together at some crucial moment in the 700s BCE. But the Iliad is older than that, and like a cathedral, or museum, or great city, it’s the production of many people, from the poem’s earliest singers, to their audiences, who inspired and shaped new singers, to whatever in the world happened in the 700s, to the later Greeks, who loved and memorized and copied and reshaped the poem, to copyists in the Middle Ages who preserved it, to modern translators and scholars who continue to breathe life into it, to you. And now, you know the Iliad, and you’re a part of it, too. [music]

Moving on to the Odyssey

Well, let’s continue on to the Odyssey, shall we? In the Odyssey, we get to learn Homer’s take on what happened at Troy after the death of Hector. They all made peace with one another, cut their losses, shook hands, and – no – just kidding, it was a horrifying massacre. But after the real ending of the Trojan War, we get the most famous adventure story in European literature. There will be witches, cyclopes, sirens, temptresses, hungry monsters, exotic palaces, wine, feasts, shipwrecks, a furious sea god, a trip to the dark pits of Hades, and a bloody beatdown at the end to match anything in the Trojan War. Thanks for listening to Literature and History, as always there’s a quiz on this program at literatureandhistory.com if you want to test your retention of these characters and some of the scholarship on Homer, and I have something a bit special to close this episode before we move on to the Odyssey.I have written, recorded, and mixed an epic rap battle, starring all the main characters of the Iliad. If you want to check it out, and listen to verbal sparring between Achilles, Hector, Odysseus and company, it’s about five minutes long and the audio of this song is coming up in a second. I have also – and bear with me in my sometimes tacky attempts to popularize classical literature – made a 3d animated cartoon of this very rap battle on YouTube, which you can find links to on my website – there’s a little YouTube icon on the upper right hand corner of the screen, or you can visit literatureandhistory.com, and click Episodes, and then Songs and find it there. I realize it’s unconventional for an educational podcaster to write comedy tunes, let alone create animated cartoons of their own comedy songs, but I thought it would be a fun way to celebrate one of my favorite pieces of literature on earth, and I’m terrible at social media and advertising and all that so I thought it might be a good promo piece for the podcast if some of you shared it with your friends. So this ends the strictly serious part of the show. If you’re not partial to my second rate musical tomfoolery, just hit stop or jump to the next episode. Thanks for listening to Literature and History and, and here’s the “Trojan War Epic Rap Battle.”

References

2.^ Homer. Iliad. Translated by Robert Fagles and with an Introduction by Bernard Knox. Penguin, 1990, p. 442. Further book titles come from this volume in this episode transcription.

3.^ Homer. Iliad. Translated and with an Introduction by Caroline Alexander. HarperCollins, 2015, p. 424. Further references to this text will be quoted parenthetically with line numbers.

4.^ Particularly in Virgil’s Aen 5, harried by Juno and fresh from the awful death of Dido, it seems peculiar that the Trojans stay over for multi-day funeral games for old Anchises. In Statius (The 6), a book worth of funeral games held at Nemea for the dead infant prince are even clunkier, considering the awkward circumstances of the baby’s death.

6.^ Alexander (2015), p. 483.

7.^ See Nicolson, Adam. Why Homer Matters. New York: Henry Holt and Co., 2014, p. 103. This wonderful, accessible book was central to my research on Homeric authorship, and many other topics having to do with the Iliad and Odyssey