Episode 15: Canaan

The Old Testament, Part 1 of 10. 1207 BCE. Two world empires. And between them, an unassuming strip of seacoast land that has been at the center of history, ever since.

| Read Transcription | References and Notes |

| Episode Quiz | Episode Song |

| Episode on Spotify | Episode on Apple Podcasts |

| Previous Show | Next Show |

Canaan: The Historical and Archaeological Background of the Old Testament

Hello, and welcome to Literature and History. Episode 15: Canaan. This is the first of ten episodes of this podcast that will be devoted to the Tanakh, or Old Testament, and this program will focus on the history of territories within what is today Israel, Palestine, Lebanon, and Syria, between about 900 and 500 BCE. Our goal in this program is to learn the basic geography and Ancient Near Eastern history necessary for understanding the earlier books of the Old Testament – the books that stretch from Genesis to Kings. The narrative portions of these earlier books tell two main stories. The Bible’s first five books offer the long narrative of the patriarch Abraham, his forebears and his successors. And the next ten or so books, depending on which Bible you’re holding, tell the story of two kingdoms once situated in modern-day Israel and Palestine – a northern kingdom, anchored in Samaria (today, the town of Sebastia in Palestine), and a southern kingdom, anchored in Jerusalem. Setting aside the narratives that trace the descendants of Adam all the way down to Moses, the entire Tanakh is colored by historical events that happened in these two ancient city states, whose capitals were just 35 miles apart as the crow flies.The tale of these two kingdoms – called Israel and Judah in the Bible – is an intense, dramatic story. A northern monarch leads his people into apostasy, and the kingdom suffers; a southern monarch is pious and good, and his kingdom is prosperous; but a generation later, the southern monarch’s successor leads his people astray, and the northern monarch’s successor suddenly takes the right path – this is the narrative of hundreds of pages of the Tanakh, alternatingly, again and again. The Old Testament, when you actually work your way through it, is often an insider’s book, expecting you to have a knowledge of a local world of ancient civilizations once rooted on the far eastern shore of the Mediterranean. The authors of, and contributors to books like Numbers, Judges, and Kings wrote these books for contemporaries and successors who were steeped in local and tribal history – readers who knew that Moab was east of the Jordan River, that Edom was to the south of it, that Aram-Damascus was a powerful nation in the northeast, and so on. We don’t have this knowledge when we open the Tanakh today. Many of us, opening the Old Testament, don’t expect a narrative so taken up with wars and power politics; monarchical dynasties and foreign invaders – a narrative that covers centuries of history, and throws hundreds of proper nouns at you along the way – places, names of foreign leaders and peoples, names of foreign gods and religions, all with the tacit expectation that you are an Israelite and on all subjects a partisan of a theological and cultural movement that blossomed to life in Jerusalem over the course of the 600s BCE. And so in this episode, the first of many Literature and History episodes that will cover the Tanakh, Second Temple period, New Testament, apocrypha, Early Christian sects, church fathers and Late Antique theology, we’re going to take an unconventional step. We’re going to leave the Bible closed for the moment, for this first of our episodes on the world’s most influential book. And instead, we’ll mainly be looking at the material archaeological record in order to start understanding where the earliest portions of the Old Testament came from.

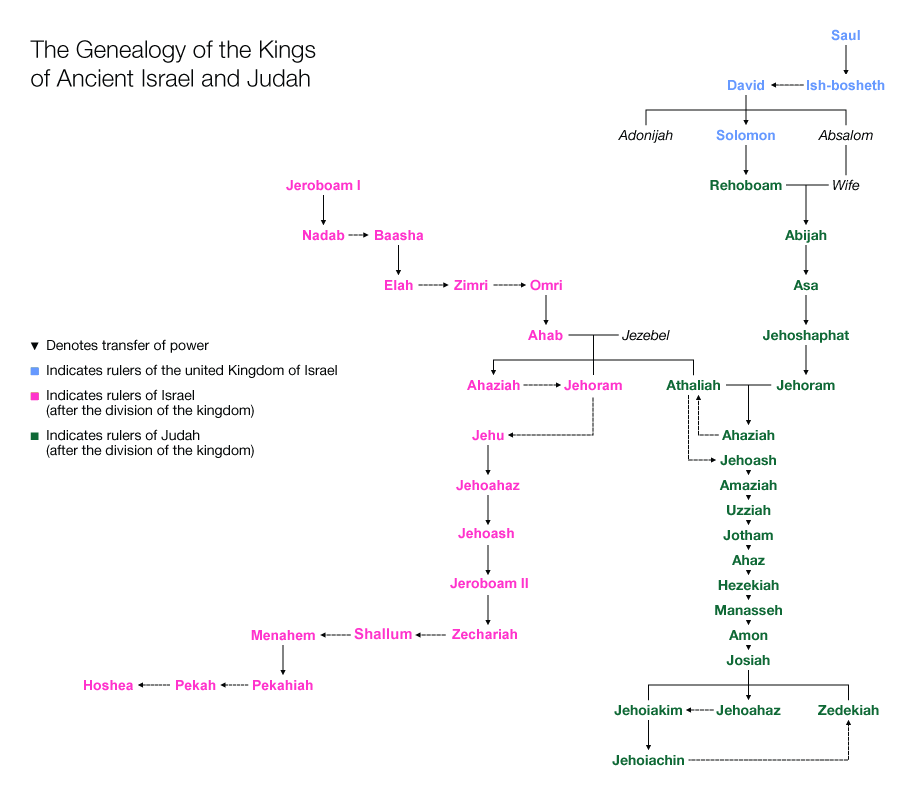

This is the most important image to familiarize yourself with in order to understand the Old Testament. The Old Testament is essentially the tale of two regions – Jerusalem, the southern capital (called Judah), and Samaria, the northern capital (called Israel). Almost every single name you see here is part of the narrative of the Old Testament. Map by Richardprins.

Before we jump into the Iron Age history of Canaan, let me say a couple of things. The decision to use the name “Tanakh,” or “Old Testament,” is an important, and a complicated one. I will use both terms to describe the book in my episodes on the subject, although, due to variations between the Tanakh and the various Christian Old Testament canons, “Tanakh” and “Old Testament” don’t quite describe the same collection of books, and certainly not in the same order. The Tanakh, which came together mostly between the 600s and 100s BCE, was a compendium of Jewish sacred writings ages before Christianity existed – a collection gradually supplemented in the history of Judaism by the Oral Torah, which was in turn codified and developed during Late Antiquity into Midrash, and separately, into Halacha and Aggadah by the Mishna and Gemara of the Talmud to form the foundational texts of modern-day Rabbinical Judaism. The Tanakh was first, and has been ever since, a Jewish book, and so our focus as we learn about it will be on ancient Jewish history – the First Temple period, the Exilic Period, the Second Temple period and Hasmonean monarchy, the Herodian dynasty, and then on into the Christian period. The Tanakh is a book with astounding theological diversity, with bluntly proscriptive early texts like Leviticus and Deuteronomy eventually giving way to books written during the Persian and Hellenistic periods – books like the world-weary Ecclesiastes, the sultry Song of Songs, the kindly book of Ruth, and the almost novelistic sagas of Esther and Daniel. The Old Testament’s outlook, ultimately, becomes more cosmopolitan and pluralistic in books written during later periods of history, with the xenophobia and harsh laws of earlier texts like Numbers and Joshua ultimately giving way to the gentler worldview of later books like Jonah, and in the expanded Roman Catholic canon, Tobit, the Wisdom of Solomon, and the Greek additions to Esther. Produced, once again, mostly between the 600s and the 100s BCE, the books that eventually became the Tanakh’s canon were authored by very different epochs of ancient Jewish history, some of them dire and terrifying, others peaceful and commercially prosperous, and others still outright triumphant.

But let’s begin at the beginning. Not the beginning of Genesis, thought by most modern Biblical scholars have been produced during or after the late 600s BCE.1 Let’s begin six hundred years before this, in the twilight of the Bronze Age, during which the civilizations of the Ancient Mediterranean and Fertile Crescent had expanded and commercially interconnected with one another, cuneiform was the lingua franca of the Ancient Near East, and trade had linked up city states from Mesopotamia to Sub-Saharan Africa to the Baltic Sea to Sicily.2 We will begin the long story of the Bible just before night fell on the Late Bronze Age – in the year 1207 BCE. Because 1207 BCE, as we’ll see in a moment, gives us our first historically recorded instance of the name “Israel.” [music]

The Judaean Mountains North of Jerusalem, 1207 BCE

Mountains near Jerusalem. Ecological microclimates in the mountains of Judah caused pastoral tribespeople to congregate up away from the coast, which was the hardest hit by the Bronze Age Collapse. Photo by Someone35.

To the east, just eight miles over ridges and down through small basins, lies the Jordan Valley. You might walk there from the shelter of the hills north of Jerusalem in half a day at a good clip. Cresting a few final boulders, you’d look out over the lowlands and see birds. Even long before the settlement of Canaan, birds told the story of what kind of a place it was and would be. Over the Jordan Valley, as we look out in 1207 BCE, 500 million birds are making their way north along the migratory flyway, passing over the four thousand mile long scar called the Syrian-East African Rift, a rift which cuts northeast from the Red Sea, all along the Jordan River, through Lake Galilee, and deep into the mountains of Lebanon. Over the Jordan Valley fly cranes, geese, and eagles, some 500 species that begin and end at many destinations, but all pass over the land of Canaan along the way.

The diverse lands of Canaan – the deep southern desert, the damper coastal plain, the central hill country and arable valleys, the freshwater lakes and rivers and springs – they have since early Paleolithic times been inhabited. But climate and natural resources, at least in the ancient world, made Canaan less amenable to large populations than its monolithic neighbors to the south, north, and east. Erratic rainfall was the primary hindrance to population growth. A whole generation might experience seasonal abundances of water and strong crop yields. The next might face dearth and famine, and, in desperation, migrate along desert roads to the Nile Delta to the south. Such variances in Canaan made for a smaller, more scattered population than in ancient Egypt, Assyria, Babylon, and Hattusa, with their more reliable abundances of river water. By 1207 BCE, great empires had formed along the Nile, along the Tigris and Euphrates, and in the foothills of central Turkey, not to mention the far-off Indus Valley and coastal plain in present day Veracruz. But Canaan remained, for millennia, a network of seminomadic settlements and modest trading hubs. The power of its various regions – Ammon in the east, Moab in the southeast, Edom to the south, Aram to the north, and Philistia to the west, waxed and waned according to the variations of the seasons and the invasions of foreign opportunists.

The latter – invading armies, I mean – was the other overarching cause Canaan never quite managed to become a major power player in the Ancient Near East on the scale of its neighbors. Large scale city building had begun in Egypt and Mesopotamia around 3,000 BCE. These civilizations hardened their weapons with wars and made advancements in science and industry far earlier than the peoples of Canaan did. And the peoples of this small land in the eastern Mediterranean experienced, over and over again, being caught between massive armies, brokering alliances in a bid to try and survive, sometimes enjoying rises in power, but more often, living at the whims of much larger powers.

So this was Canaan in 1207 BCE, a beautiful, ecologically diverse strip of seacoast land, the balmy back end of the Mediterranean, a territory with many biomes and many peoples, and not, during the twilight of the Bronze Age, a place that seemed like it would play such a tremendous role in world history. After the 700s BCE, however, Canaan would be the knot at the center of a rope tugged by greater powers – Egypt and Assyria, Assyria and Babylon, the Achaemenids and the Macedonians, the Ptolemaic Empire and the Seleucid Empire, Rome and the Parthians, the Byzantines and the Sasanians, the Byzantines and the Islamic Caliphates, the Caliphates and the Crusaders, and back and forth and on and on. It would be the anvil on which the single most influential book in human history would be produced, century after century. But let’s leave that book on the shelf for a bit for a while longer, still, and talk about the origins of the people who created it. [music]

Canaan, Egypt, and the Merneptah Stele

In 1207 BCE, the Egyptian Pharaoh Merneptah returned from his campaigns abroad. Merneptah’s capital was Thebes, a city halfway down the Egyptian Nile, 700 miles to the southwest of Canaan. Pharaoh Merneptah’s capital, Thebes, was a grand city, with colossal statues and vast temples, honoring the past two millennia of Egyptian civilization. Across the river from Thebes lay the Valley of Kings, where a hundred years earlier, the tomb of the boy king Tutankhamun had been cut from living rock and sealed, not to be opened for 3245 years.In 1207 BCE, Pharaoh Merneptah returned to Thebes, victorious from wars abroad. When he landed in Thebes, he did what many ancient strongmen did after a military campaign. He had his achievements recorded in a stone carving. The Merneptah Stele, a 10-foot-high slab of black granite, now sits in the Egyptian Museum in Cairo. Like many other Bronze Age royal inscriptions, the Merneptah Stele is chillingly matter of fact about the carnage unleashed in its sponsor’s wars abroad. The stele first records Merneptah’s wars in the west, with the peoples of modern-day Libya and their northern allies. The Merneptah Stele announces, “Great joy has arisen in the Black Land [of Egypt], and shouts of jubilation come forth from the towns of Egypt. They are talking about the victories which Merneptah. . .achieved over the [Libyans]. How beloved he is, the victorious ruler.”3 The stele describes Egypt’s decisive victory over its rebellious colonies in North Africa, and then, almost as an afterthought, describes a brief campaign that the Pharaoh Merneptah conducted in the land of Canaan.

Canaan, in 1207 BCE, was securely under the yoke of Egyptian imperial power. Merneptah’s father, Ramesses II, had been the most powerful of all of Egypt’s pharaohs, and had exercised tight control over the peoples and resources of Canaan. When Ramesses II died in 1213, and Merneptah assumed leadership, the lands of Canaan, once subjugated as client kingdoms of Egypt, seem to have begun trying to fight for independence. It was therefore important for Merneptah to quell any insurrections in the lands to the northeast. The Pharaoh Merneptah needed to show that he had the same military prowess and long arm as his father, and he did this by waging a punitive military campaign against the Libyans, then crossing the Sinai and Negev deserts, and subduing the small city states to the north that had tried to assert themselves.

The Merneptah Stele, again, carved in 1207 BCE, concisely records Pharaoh Merneptah’s victories in Canaan. It announces that “Now that [Libya] has come to ruin, / The Canaan has been plundered into every sort of woe: / Ashkelon has been overcome; / Gezer has been captured; / Yanoam is made nonexistent. / Israel is laid waste; his seed is no longer.”4 And to repeat that last line, “Israel is laid waste; his seed is no longer.” That line, carved into black granite, is the first historical mention of Israel that we know of outside of the Old Testament. It was cut into rock, 700 miles from Canaan, at the turn of the twelfth century BCE, in the twilight of the Late Bronze Age. This stele was discovered by the pioneering British archaeologist Flinders Petrie in 1896, and when Petrie found it, he knew that it would be the most important discovery of his career.

For my listeners who are totally unfamiliar with the Old Testament, let me pause for just a minute and explain why this piece of black granite found along the Egyptian Nile was such a big deal. The Israelites are the main protagonists of the Tanakh, or Old Testament. Isra-El means “The one who struggles with God,” and the main narrative portion of the Tanakh is, to put it absurdly briefly, about the people of Israel making covenants with God, breaking those covenants, and being rewarded and punished accordingly – the story of a people’s long, epic struggle with both their own devoutness as well as the intrusions of foreign armies. The Merneptah stele of 1207 is a big deal because it’s the first piece of definitive archaeological evidence that we have, outside the Old Testament, that a people called the Israelites existed at the end of the Late Bronze Age in ancient Canaan.

Now, if you’ve read the Tanakh, or even just dipped into the first few books, especially the end of Genesis and much of Exodus, you know that Canaanites frequently had unpleasant dealings with Egyptians. But, let’s continue to keep the Bible closed for now, and talk about the archaeological record of the relationship between Canaan and Egypt. This relationship had been going on long before the Merneptah stele was carved in 1207 BC. Egypt was almost always more powerful, and more stable than the arid coastal plains and hill country of Canaan. The center of the Nile Delta lies a little over 500 miles from the Canaanite highlands where the earliest Israelites seem to have lived. This was a route that, in 1207 BCE, ancient Egyptians knew well. The road that led from the lush Nile Delta, over the present-day Suez Canal, across the arid expanse of the Sinai Peninsula and the Negev Desert of southern Israel was called the Ways of Horus. This road was a carefully engineered chain of forts, wells, and stocking stations, each one a day’s march from the next, so that even huge armies could cross the desert and remain fortified with provisions. The Ways of Horus was Egypt’s interstate freeway north, a string of garrisons designed to control traffic across the desert.5

A tomb discovered near the modern day town of Beni Hasan contained well preserved wall paintings dating between the 2000s to the 1600s BCE. One of these displays a series of figures dressed in Semitic garments, thought to be Hyksos in origins – in other words from Canaan or the lands around it. To biblical literalists, the Beni Hasan tomb is evidence of a broad Israelite presence in Middle Egypt during the Middle Bronze Age, a time around which Rabbinical history dates the life of Moses and the Exodus from Egypt. To archaeologists, the tomb simply shows a record of an unusual period of foreign leadership in Egypt in the Middle Bronze Age.

It had been built, however, long before 1207 BCE. On one occasion, and one occasion only to our knowledge, Canaan reversed the long historical pattern of subjugation in the region. An entire dynasty of pharaohs, in power between 1670 and 1570 BCE, were Canaanite in origin. They came to power at a site called Avaris, and they were called the Hyksos. Avaris was in the northeastern part of the Nile Delta, about 70 miles northeast of present-day Cairo as the crow flies. Archaeological excavations of Avaris have demonstrated a slow swelling and spreading of Canaanite burial customs, pottery, and building practices there. The Hyksos, through a gradual process of immigration, gained power in Egypt, bringing with them northern military tools like the composite bow, the horse, and the chariot. Canaan, for this brief time – again 1670-1570 BCE – exercised control over Egypt. It was the high-water mark of Canaanite power in the region. And it would not happen again.Ancient Egypt had too many monolithic reminders of its cultural past to suffer under the Canaanite Hyksos dynasty for long. Around 1570, the Canaanite leadership of Egypt was forcibly exiled, and the Ways of Horus were built to monitor immigrant traffic and buffer invasions from the north. Centuries passed, and the Middle Bronze Age trickled into the Late Bronze Age, and Ancient Egypt for a time became the most powerful empire in the Mediterranean and Ancient Near East. Canaan, in turn, over the 1400s, and 1300s, and afterward became a small marchland in between greater powers.

Two hundred years after the Canaanite Hyksos pharaohs ruled over the Nile, during the 1350s BCE, we have substantial evidence of the power Egypt exercised over Canaan. The famous Amarna letters, found at the capital city of the heretic monotheist pharaoh Akhenaten at the turn of the twentieth century, tell of what was going on in Canaan during the Late Bronze Age. By the mid-1300s, in contrast to the brief period during which Hyksos pharaohs had ruled Egypt, the tables had turned. Canaan was totally dominated by Egypt. Its tiny city-states, as modern archaeology has shown, city states that included Shechem, Megiddo, Hazor, Lachish, and Jerusalem, were little more than unwalled settlements – small palaces and temple compounds with outlying administrative buildings. Canaan’s population, in comparison to its long armed imperial neighbors, was tiny and powerless during the 1300s and 1200s BCE. Egyptian forts and garrisons studded the territory, and an Egyptian military capital in Gaza, at the time of the Merneptah Stele of 1207 BCE, made sure that the peoples of Canaan remained subjects of their overlords along the Nile.

Let’s return to the Merneptah Stele, and the first mention of Israel. By the year 1207, Canaanites and Egyptians knew one another quite well. Canaanites had been in Egypt. Egyptians had been, and continued to inhabit Canaan. Before and after the year 1207, traffic continued along the Ways of Horus. The peoples of Canaan had cultural memories of migrations down to Egypt. Sometimes, in decades of low rainfall in Canaan, the region’s inhabitants crossed the southern desert and went to the lands of Nile Delta, where food was more plentiful. At other times, they journeyed to Egypt as traders. At still other junctures, they were captured as prisoners of war and compelled to work on pharaonic building projects. In 1207 BCE, to the hill dwelling Semitic speaking people we know as the Israelites, Egypt was the bronze fist that hung over the highlands west of the Jordan River. Only, something happened that’s come up a number of times in this podcast so far. Something apocalyptic, a perfect storm that changed the balance of power in the Mediterranean world. Without this something, the Israelites might have remained another highland tribe lost to history, and the Bible never would have been written. This something was the Bronze Age Collapse. [music]

The Bronze Age Collapse Comes to Canaan

The Merneptah Stele, which records the pharaoh’s victories against the Libyans to the west, shows optimism about Egypt’s continued regional power, and the king’s capacity to subjugate his foes. But less than a century later, Egypt was on the brink of annihilation, having fallen deeply into what Egyptologists call the Third Intermediate Period. What happened that sent this imperial juggernaut on a path to destruction? How could the most powerful empire of the Late Bronze Age be hobbled in less than a hundred years?

An illustration of migration patterns during the Bronze Age Collapse, courtesy of Lommes [CC BY-SA 4.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)], via Wikimedia Commons.

There are many theories as to why the Sea Peoples invaded at the end of the Bronze Age. Several of them hold widespread credibility. Climate change was almost certainly part of the picture. The semiarid country of the eastern Mediterranean, always sensitive to years of low rainfall, likely experienced exceptionally low crop yields over successive years. Studies of core sediment samples from around Galilee and the Dead Sea in Canaan show that a severe drought plagued the region around the beginning of the Bronze Age Collapse. Famine during the period is widely recorded, and would have driven oceangoing raiders eastward in search of provisions and stable living conditions.

Another well regarded theory about the Bronze Age Collapse is often called the “systems collapse.” In the main power centers of the ancient world, a premature degree of specialization – in crops, in commerce, metallurgy, and irrigation – was crudely superintended by heavy handed kingships. These kingships were always vulnerable to assassinations, coups, and succession disputes. When this already imperfect system faced rapid systemic change as a result of population growth, evolution in military technology, sudden famine, and strongly motivated raiders and migrants from the north and west, the civilized centers of the Mediterranean and Ancient Near East buckled. Some, like Ugarit in present day Syria, and Hattusa in present day Turkey, never rose again. Others were changed forever by the influx of new citizens and the rearrangement of whole economies. But our goal in this program isn’t to look at the Bronze Age Collapse in its entirety. For our present purposes, we need to come back to Canaan, to 1207 BCE, when the name “Israel” first appears on the written record.

Let’s once more imagine ourselves twenty-five miles north-northeast of Jerusalem. Pines and shrubs rise out of shaded ravines, and pale rocks tower like ramparts on the heights. Flocks of goats chomp on tough native bushes, and kestrels hover overhead in the cloudless sky. Nearby, an olive tree has dropped its fruits down to a twiggy world of bugs and rodents, and the fragrance of flowers and fermentation passes over the rugged landscape. At dusk, the stalks of dry grass hold the fading light as the sun plunges into the Mediterranean to the west.

As we’ve learned in this program so far, this scenic little corner of present-day Palestine was not a very consequential place during the Bronze Age. But being inconsequential, during certain periods of history, has considerable advantages. Modern archaeologists, working in sites throughout the Judaean Mountains, have now pinpointed what they believe are the earliest material remnants of the Israelites mentioned in the Merneptah Stele. And if we imagine living in those mountains, as the Sea Peoples established beachheads on coastlines, as raiders broke down city walls in the desert and along the coastal plain and began looting and killing, and as interdependent economies broke down under the pressure of civilizational collapse, the small communities of the Judean Mountains must have been pretty decent places live during the end of the world. Let’s talk about those communities.

Whatever defeat the Israelites suffered from Pharaoh Merneptah in 1207 BCE, they recovered. And over the next century, as that generation of Israelites, and their children, and their grandchildren stood in that sequestered region twenty-five miles north-northeast of Jerusalem, they would have seen smoke if they looked north and westward. The cities of Canaan’s upper coastal plain bear archaeological evidence of mass destruction during the Bronze Age Collapse – this coastal plain was ground zero for the Sea Peoples who’d come from the Aegean and Central Mediterranean in search of plunder. Seventy-five miles to the north of this inland region of the Judaean Mountains, the prosperous city of Lachish fell to foreign invaders, not to be resettled for two hundred years. Fifty miles away from the sheltered highlands, the coastal cities of Ashdod and Ashkelon were destroyed and repopulated by Philistine conquerors. Even closer, less than forty miles distance from our quiet spot in the highlands, the city of Megiddo was also burned. In the distant north, large cities in present day Syria and Turkey fell to the sea people – Carchemish, Alalakh, Aleppo, and beautiful, civilized Ugarit.

If you lived in those sequestered hills, twenty-five miles from Jerusalem, as the some of the earliest Israelites did, you would not be safe over the course of the apocalyptic 1100s BCE. But in comparison to your coastal neighbors, with their dense population concentrations, their wealth, and their provisions, you and your family would not be a principal target. You’d quietly tend to your herds and scattered fields, be on the lookout for marauding patrols, cultivate your small vineyards and olive groves, and try to protect and provide for your family and clan.

The reason I keep bringing up this very specific region of what’s today Palestine has to do with some of the pioneering work of the last few generations of archaeologists at work in Israel, Palestine, Lebanon, Syria, and Egypt. Using techniques of survey archaeology in the Mountains of Judaea, archaeologists, beginning with the pioneering work of Yohanan Aharoni in the 1950s and 60s, gradually uncovered more than 250 communities scattered among the hills north of Jerusalem and southwest of Lake Galilee.6 These communities, each home to about fifty adults and fifty children, added up to about 45,000 people, all told. These highlanders north of Jerusalem were able to weather the Bronze Age Collapse due to their remote location, and relative self-sufficiency. As maritime and overland trade connections disintegrated during the 1100s, the hill dwellers of central Canaan remained sturdily self-sufficient, and modest in their means of living. They had no palaces, no centers for food storage, no public halls, almost no luxury goods, and their structures were, on average, some 600 square feet in size. Their villages, unlike the towns on the coastal plains to the west, had no fortifications, and no weaponry. These unassuming highlanders, sheltered from the Bronze Age collapse by the obscurity of their location, are thought by modern archaeologists to be the first Israelites. Again and again, I’ve mentioned the hills twenty-five miles north of Jerusalem, roughly the site of the northern city of Shiloh. If the dispersed villages of the earliest Israelites had a geographical center, this might have been it.

One question remains, though. We have a mention of the noun “Israel” on the Merneptah Stele of 1207 BCE. And we’ve just learned that hundreds of modestly sized Late Bronze Age communities have been unearthed in the region around Shiloh by the careful work of the past three generations of, most frequently, Israeli archaeologists. The question is, why do specialists believe that these villages seeded among the Judaean Mountains during the 1200s, 1100s, and afterward belonged to the Israelites? Couldn’t the highland villages north of Jerusalem have belonged all sorts of different nomadic herders? And here is the answer.

The highlands of what’s today Israel and Palestine were inhabited for a long time. Long before Egypt raised its first pyramid, seminomadic settlements thrived there, in the Mountains of Judaea, and for that matter all of the rugged parts of Israel and Palestine where herding was more feasible than tilling crops. And communities of highlanders thrived not just to the north of Jerusalem, but also to the east and south of the Old City, in the lands of Ammon, Moab, and Edom. The cultures of these various highland regions were largely interchangeable. Archaeology shows that they worshipped conventional Canaanite deities, among them El, the distant patriarchal god of the Levant, symbolized by a bull and later incorporated into Biblical Hebrew names like Bethel “house of God” Elohim “God” or “Gods,” and Israel “The one who struggles with God.”

But there was a discernible difference between the 250 or so communities unearthed around Shiloh, and the other dig sites all over modern-day Israel and its neighbors. This difference was that for whatever reasons, the inhabitants of central Canaan – this area 25 miles north-northeast of Jerusalem, did not keep or consume pigs. The Ammonites, the Moabites, and the Edomites all did. But centuries and centuries before restrictions against pork were formally set down in Exodus and Leviticus, the Israelites disdained the husbandry of pigs. They were, then, by 1207, a people for whom we have a named historical instance, archaeological evidence, and, most importantly, a people who considered themselves culturally distinct from key neighbors, as archaeological remnants of their animal husbandry shows. And 1207, needless to say, was only the very beginning of their presence on the historical record. [music]

The Emergence of Israel and Judah in the Early Iron Age

The Bronze Age Collapse shattered Egypt’s control over Canaan. Other peoples – the aforementioned Sea Peoples – migrated and settled along the coast, and the demography of the territory’s population centers was radically transformed. To the hill-dwelling Israelites of the 1100s BCE, the despoliation of Egypt, which had had its boot on Canaan’s neck for four hundred years, must have been a gratifying sight to behold. Egypt, pummeled by raiders from the west and north, retreated from its colonies and withered. The imperial strongholds of Egypt no longer held sway over Canaan. And when the Sea Peoples continued inland in search of more concentrations of wealth and prosperity, Egypt’s former vassals in Canaan, including the Israelites, suddenly had room to breathe and stretch their legs. There was, in Canaan, a power vacuum, and it began to draw people down from the highlands. The population of the hill-dwelling Israelites swelled. They expanded westward, beyond the interior valleys of the east. In the centuries between 1200 and 1000, archaeology shows an increasing degree of specialization in the early Israelites. Slowly, they transitioned from self-sustaining communities of a hundred or so villagers each to interknit networks based on commerce.The process was similar to the one we saw in early Greece. Your village might own a fabulous olive grove on some dry slopes, but lack fertile lowlands to grow grain. But the people on the other side of the ridge had just the opposite, and so you traded with them. Then there were those other people who lived up north whose goats produced that really tasty milk, and so you traded them some goat milk for olives. A few generations of this sort of thing, some intermarriage, growing genetic diversity, some fine tuning of cultivation techniques, some mass exchange of collective knowledge, and maybe a couple of families immigrating in from Mesopotamia or Anatolia and sharing ideas and technologies with you, and you had the start of a civilization. It was happening all over Canaan. The Edomites to the south, the Moabites to the southeast, and the Ammonites to the east, now the Egyptians were gone, were all free to grow and prosper. Sea Peoples, too, settled, adding their engineering knowhow and cultural heritage into the new demographics of Canaan as the Bronze Age ended and the Iron Age began. The Bronze Age collapse turned scattered hill communities like those of the Israelites into distinct city states. The once meek, due to the flux of history, had inherited a nice bit of Earth.

Toward the beginning of this episode, I mentioned the two kingdoms central to the narrative portions of the Tanakh. These kingdoms were Israel in the North, and Judah in the south. These two kingdoms had very old roots. Even before the Bronze Age Collapse booted Egypt back to the Nile, the hill communities of central Canaan – the future Israelites – had long been loosely divided into two regions. By 1,000 BCE, the Israelites had congregated into ecologically and geographically distinct areas. In the north, their capital was Tirzah, just ten miles east of where the northern capital of Samaria later be. In the south, the regional centers were Jerusalem and Hebron. The northern kingdom, early on, was far more populous and prosperous. In the north, fertile valleys provided farmland, and regions of the northern kingdom lay on the overland trade route between Egypt and Mesopotamia. The greener pastures of the north received more rainfall, and, abutting the cosmopolitan world of southern Syria, had more diversity in population and economy.

The south was a different story. Jerusalem, Hebron, Beersheba – these were arid, sparsely populated lands. The terrain in the south was steeper, rockier, and harsher. Olives and orchards might be managed, but always at the risk of climatic fluctuations. Because we’re going to be dealing with these two lands extensively, we need to have names for them. The names that we’ll use, and I’ve said them already, are the ones that the Tanakh gives us. In the Bible, the northern kingdom is called Israel. And the southern kingdom is called Judah. These two names are extremely confusing to the newcomer. “Israelites” is used to describe the citizens of the Biblical nations of Israel and Judah together, as the followers of a shared set of cultural practices. “Judahites,” on the other hand, always means the inhabitants of the southern kingdom.

So if you’re new to the Old Testament, then, heads up, let me repeat. Much of the Old Testament tells, or makes reference to the story of the two kingdoms of Israel and Judah. Again, the northern one is Israel. And the southern one is Judah. These two kingdoms will come up again and again in this and coming episodes, and if you need a mnemonic device just remember that “I” comes before “J,” just as the center of the Biblical Kingdom of Israel is about 35 miles north of that of Judah on a map, and Israel’s historical rise predated Judah’s. Over the next twenty or thirty minutes, I’m going to tell you about these two kingdoms – first the rise and fall of Israel, and then the rise and fall of Judah – what archaeologists have found at dig sites there, and, occasionally, why the Bible is especially concerned with certain monarchs in the north and south.

Samaria and the Jezreel Valley, 900-700 BCE

Excavations at northern and southern kingdoms, again, Israel and Judah, respectively, show that they developed on very different timeframes.7 The northern kingdom, far sooner than the southern one, departmentalized agriculturally and commercially. Archaeologists found stone administrative centers in the north that date to the early 800s, two centuries before such buildings were constructed in the south. The northern capital, Samaria, became a center of operations over a century before the southern capital of Jerusalem emerged in the late 700s. Industrial olive oil production took place in the north two hundred years before it did in the south. As long as the northern kingdom of Israel was standing, its southern counterpart Judah was always in second place. In fact, through the 800s and 900s, the southern kingdom of Judah only encompassed about twenty villages, ringed with herders and wandering bands of desert raiders.During the 900s BCE, the fragile populations of Israel and Judah experienced something which would happen again and again in the history of Canaan. This something was the incursion of a large foreign imperial power. And the power in question was none other than the Canaanites’ ancestral bugbear of Egypt. Egypt, knocked out for three hundred years after the Bronze Age Collapse, was on the loose again. The pharaoh Sheshonq invaded and conquered cities in the north – Megiddo, Taanach, and Shechem. He left the south relatively unscathed, but the assault was a grim reminder that Canaan was, unfortunately, a small place ringed by huge, powerful neighbors. Canaan, however, sometimes proved that it could hit back.

The archaeological site of Jezreel on the east end of the Jezreel valley. Israel and the northern territory, during the Iron Age, was always more fertile and populous than Judah and the southern territory. Picture by Ori.

The sons and grandsons of Omri, which included Ahab, Ahaziah, and Jehoram, saw the northern kingdom into a period of unprecedented prosperity. The Omride dynasty left behind huge building projects that archaeologists have been able to study – the city of Samaria, to the north of it, a compound of structures in Israel’s Jezreel valley, palaces in Megiddo, and robust fortifications at the city of Hazor. The palace at Samaria, built roughly between 890 and 840 BCE, was constructed with well carved ashlar blocks and capped with beautifully ornamented stonework, demonstrating both cosmopolitan architectural influences as well as sophisticated engineering techniques. Samaria and its sister cities in the north were also complete with underground water channels carved from bedrock. Excavations within the Jezreel valley during the 1990s showed distinct archaeological features common to Samaria, Megiddo, Hazor, and a distant city on the fringe of Moab. The Omride dynasty, it seemed, were the ones actually responsible for the monumental construction projects once attributed to the Biblical Solomon. A century after their dynasty was founded, or very roughly 800 BCE, the northern kingdom had become a proper population center.

By the early 700s, the northern kingdom had around 350,000 inhabitants. Rich natural resources there fed its sizable population. It was a multiethnic civilization, with ties to the Phoenicians on the coast, and Syrians to the north, and accordingly, one home to a number of different religions and languages. The northern kingdom of Samara was wealthy, productive, and organized, and its neighbors, by the end of the 800s and the beginning of the 700s, had begun to notice.

To the north of Israel, centered in Damascus, there existed a civilization called Aram, or sometimes Aram-Damascus. During the years between 835 and 800, Aram-Damascus invaded and occupied some of Israel’s regional centers. Four cities were conquered and occupied, and the Syrians may have even besieged the capital. But no all-out war followed. The Aramaeans retained their territories, and across Israel, pottery and other artifacts thereafter show Aramaic writing alongside Hebrew. Aramaic would later be a part of Canaan’s culture and the lingua franca of the Ancient Near East for a long time – the language of Jesus, and one of the main languages of the Talmud.9 The northern kingdom continued to be, as it always had been, a diverse mixture of peoples, and though the armed incursion by Aram-Damascus was no peaceable affair, it seems to have resolved itself in a renewed stasis between the two regional powers. As powerful as Aram-Damascus and Israel were, however, they were still young, and only medium-sized kingdoms as far as Iron Age dominions were concerned. One kingdom to their east was much larger and more powerful. This kingdom had weathered the Bronze Age Collapse and persisted. Israelites had met them once before, under King Ahab, and survived. But over the next century, no power in Canaan, and no confederation of powers in the ancient world, would be able to stand up to the terrifying strength of the Assyrians. [music]

Assyria Comes to the Northern Kingdom

If you read the tablets and stone inscriptions that record the achievements of the Assyrian kings, you get the impression that they were a pretty harsh civilization. In a previous episode, I read you a testimony of Tiglath-Pileser, who bragged about flaying rebellious chiefs and covering a pillar with their skins, who bound severed heads to tree trunks, who impaled victims on pillars of spikes, and who dismembered, mutilated and burned alive citizens of conquered cities. It’s difficult to know the reality behind such appalling monarchical inscriptions. The Middle Assyrian Code, a set of laws developed during the late 1000s BCE in the ancient Iraqi city of Ashur, show that the Assyrians were just as harsh with one another as they were with subject kingdoms. Punishments included an encyclopedia of mutilations and dismemberments, with cutting off noses, ears, fingers, genitals, rape, impalement, and gouging out eyes all par for the course.10

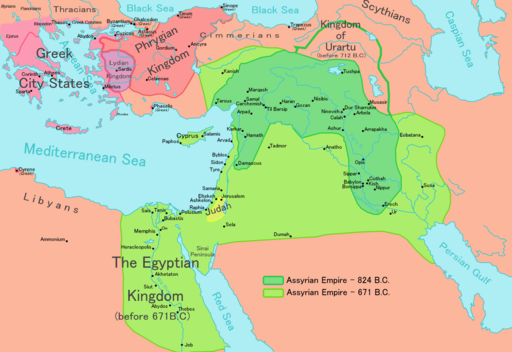

This map shows the astonishing expansion of the Assyrian empire over the course of about a hundred and fifty years. This expansion eradicated the Northern Kingdom and threatened the southern kingdom, as well. The later Historical Books tell the story of Canaan’s encounters with Assyria. Map by Ningyou.

Under the long reign Jeroboam II, from very roughly 790-750 BCE, the Hebrew and Aramaic speaking citizens of Israel saw more public building projects, and the elite citizens of Samaria who spent time in the palace there and surrounding grounds enjoyed an opulent lifestyle. Archaeologists have found ornately carved ivory plaques and fine furniture in the palace of Jeroboam II, and even a royal seal bearing the name of a courtier who described himself as “Shema, the servant of Jeroboam.” The earliest of the biblical prophets, Amos and Hosea, knew the luxuries of Israel’s court during the second half of the 700s, and their writings, or perhaps later writings attributed to them, disdained the luxuries of the northern king’s lavish court as the decadent frippery of an impious monarch.

When Jeroboam II died in 747, a rapid succession of rulers followed him, and changes in leadership were occurring in Assyria as well. A king called Tiglath-Pileser III, (the Bible calls him Pul) assumed power in 745. In the next decade, this new Assyrian monarch Tiglath-Pileser III placed fierce new economic demands on Canaanite cities. Unable to meet them, the King of Israel at the time, Pekah, attempted to form a consortium with the coastal cities and Damascan rebels in the north. But Canaan’s military efforts against the Assyrians were futile. The northern part of Canaan faced widespread destruction. Several biblical records of the Assyrian destruction of Israel in the late 730s BCE are supported by archaeological evidence. Syria, Damascus, and its king fell first. Israel was next. Only the core region of Samaria was left semi-sovereign. Meanwhile, neighboring Megiddo was made the center of Assyrian power in the north. The regions of the kingdom of Israel, which had grown and grown from 870 and 750 BCE, had suddenly shriveled into the tiny core of Samaria and its vicinity.

The final king of Israel, Hoshea, came to power by assassinating his predecessor. In the 720s, Hoshea saw what he believed was a golden opportunity. The Assyrians were transitioning between kings. There was the very real possibility of a dynastic dispute. While Hoshea continued paying his tribute to the Assyrians, he secretly formed an alliance with Egypt. His strategy would be to pit the two world powers against one another. Assyria, after all, might be mired in leadership squabbles, and this unusual juncture in the 720s seemed like it would be the northern king Hoshea’s only real chance to win sovereignty for himself and put regional power back in the hands of Samaria. Hoshea ceased his tribute payments to Assyria and waited for the clash between the two empires to unfold, expecting a slow, poorly coordinated response from the east. Hosea did not get what he expected.

The new king of Assyria – this was Shalmaneser V, seeing that the tribute payments from King Hoshea had ended, moved in and destroyed Samaria. Assyrian records tell of the massive victories, and the forced resettlement of tens of thousands of Israelites into various regions of Mesopotamia. In turn, Assyrians settled thousands of their own people into the fertile regions of Israel. This was the end of Canaanite leadership in the north, and the Biblical kingdom of Israel. But it was not the end of a Canaanite citizenry in the north. Although Assyria did deport unknown numbers of Israelites, the majority of them stayed behind. Assyrian conquerors knew that it’s bad policy to depopulate a country of its harmless and productive peasantry. And so the always cosmopolitan northern region of Canaan, now populated with outsiders from a wide range of eastern cities, became even more cosmopolitan. The ideologies, stories, and religions of faraway kingdoms in modern day Iraq and Turkey now had free reign to circulate among the Israelites, along with those of the Aramaeans, who had already been there for other a century, and those of the Egyptians, who had been there for millennia.

But this new, even more international state was no utopia for the conquered Israelites. The terror and butchery of the Assyrian conquests of the 720s, together with property confiscations and new resident aliens, drove the subjugated Israelites south, out of the green expanses of Samaria and the Jezreel valley, and into the dryer hinterlands of Judah. And finally, after the fall of Israel in the north, in the last decades of the 700s BCE, the city of Jerusalem would begin to rise, and over the course of the next century, a new faith involving exclusive devotion to Yahweh above all other Canaanite deities would emerge onto the historical record. [music]

Northern Immigrants: A Windfall for Judah, 720-700 BCE

By 700 BCE, refugees were flooding southward into the previously marginal kingdom of Judah, the southern kingdom, and the other civilization that the Old Testament spends so many hundreds of pages chronicling. With Israel in the north having collapsed, it was now Judah’s time to shine in the south. Judah’s population swelled as it absorbed immigrants from the north. These newcomers were not just dead weight. They had knowledge, and commercial connections up north, and their arrival to Judah connected the small southern kingdom with the population centers of what had until recently been the Kingdom of Israel. The refugees and their newfangled ways mandated the adoption of weights and measures, and throughout the 600s BCE, for the first time, writing appears on pottery in and around Jerusalem in the archaeological record.Jerusalem itself had been a named settlement since at least the 1300s, but it wasn’t until the 600s that the settlement grew into a city. Immigrants swelled the population from 1,000 to as many as 15,000 citizens, and fortifications were built around the town. Farms blossomed all around the growing city, and neighboring settlements all swelled in size. On the whole, the aftermath of Assyria’s sacking the north caused the regional population of Judah to increase from 20,000 or 30,000 to around 120,000. The southern kingdom experienced a shift from village subsistence farming to cash cropping, and the exiled northerners helped solidify lucrative trading arrangements with the Assyrian economy and caravans from the Arabian Peninsula.

Judah and Assyria

As had happened a century earlier in the northern kingdom of Israel, the economic prosperity of the southern kingdom of Judah led to the rise of an upper class. Over this upper class, from the 720s until around 690, there reigned a king named Hezekiah. The Bible has much to say about Hezekiah, and his descendants, and we’ll leave the details of these stories until later. The main thing to remember here is the overall story of Canaan’s history between 900 and 600 BCE, which is essentially a story about minor fledgling kingdoms trickling into the power vacuum left by the Bronze Age Collapse, only to suffer repeated conquests by larger neighbors. The story of Judah, the southern kingdom, is no exception to this general pattern.

The kings of Israel and Judah. For the purposes of historically understanding the Old Testament and its gestation, and really the entire history of monotheism, two kings are most important – Hezekiah and Josiah, both on the lower right. Hezekiah instituted religious reforms demanding public sacrifice only at the Jerusalem temple and worked to purge Canaan of its ancestral religions. His son and grandson, Manasseh and Amon, did not continue this push for Yawhistic monotheism, but Hezekiah’s great grandson Josiah did. Josiah receives more praises in the Old Testament than any king except for David, and it was probably during and shortly after the reign of Josiah that the Deuteronomistic History (the section ofthe Bible stretching from Deuteronomy to 2 Kings) was written.

The inscriptions of the Assyrian king Sennacherib, together with archaeological evidence, suggest the ferocity of the Assyrian retaliation to Judah’s rebellion. Jerusalem’s thriving sister city, Lachish, was leveled. Archaeologists discovered a mass grave nearby stuffed with some 1,500 men, women and children. The Canaanites in the south were no match for the Assyrian military. King Hezekiah of Judah was captured. Assyrians moved in and began dominating, but, as had happened in the north, Judah was not entirely decimated. Evidently, the Assyrians recognized Hezekiah’s capacities as an administrator and leader. And so Hezekiah, however it was worked out, was able to pass leadership down to his son Manasseh, who collaborated with the Assyrians and, over the course of a 55-year-long reign, from the 680s until the 640s, kept cosmopolitan Judah in relative prosperity.

Although, after the year 700 or so, Judah was under the shadow of Assyria, the southern kingdom of Judah expanded in all directions during the middle of the 600s. Satellite towns around Beersheba spread deep into the southern desert. And during this period Judah became what its northern neighbor Israel had once been – a full-fledged state, wired into regional commerce; a functional junior partner in league with more monolithic neighbors. Archaeological evidence from the mid-600s shows extensive governmental presence in the lives of the citizens of Judah. Seal impressions and administrative seals, and written records on tablets and pottery fragments attest to the spread of a literate bureaucracy. Though the Bible has nothing good to say about him, Judah’s king during the mid-600s, Manasseh, was probably a competent leader who steered his little country through a complicated era of history, and by the 640s, notwithstanding its being pulverized by Assyria a generation before, Judah was once more a promising young nation.

At the end of Manasseh’s long and successful reign, his son briefly ruled, and then his grandson came to power. Manasseh’s grandson Josiah, who ruled from around 640 to 609 BCE, is the last king I’ll mention in this episode, and, by all rights, one of the most important people in human history. Why is this so? It’s simple. During the reign of King Josiah, particularly during the 620s, Biblical scholars generally agree that a large portion of the Tanakh was written. King Josiah, like his great-grandfather King Hezekiah, believed in the exclusive worship of Yahweh. Like his great-grandfather Hezekiah, Josiah wanted the Jerusalem temple, and not any other place in the kingdom of Judah, to be the site where animal sacrifices were made. In a general movement that had been growing since the fall of the northern kingdom of Israel, King Josiah wanted the Canaanites to abandon their polytheistic ancestral traditions and to bow to a single god. The geography, the historical references, and the anachronisms of the Old Testament all generally suggest that a great deal of it was composed in Jerusalem during the reign of King Josiah or during the next generation. He is spoken of in glowing terms, as a king prophesied to deliver Judah from its wayward tendencies. Josiah is praised more highly than any other king in the Bible, except perhaps for David.

In the 620s and 610s BCE, Josiah was at the helm of a growing, cosmopolitan nation, but one which nonetheless had a large store of people who identified themselves as descendants of the ancient hill tribe called the Israelites. Josiah was a religious figurehead, probably spearheading purges against the old Canaanite religions. And somewhere in his court, a writer, or enclave of writers, were likely recording the books of Deuteronomy, Joshua, Judges, Samuel, and Kings, and producing and making changes to ancestral oral traditions passed down between generations of Israelites. Josiah himself is a main protagonist in these stories, a sort of climax that all of Canaan’s bloody history had worked to produce.

The Death of King Josiah by Antonio Zanchi (1631-1722). Josiah’s death was a horrific blow to the Judahites who were pushing for Yahwistic monotheism and against the older polytheism that continued to persist in Canaan.

Only, this doesn’t fit with the story of Canaan’s history, does it? Canaan, even in the boom times of King Josiah, even with its cadre of revisionist scribes and historians, was still a tiny place, a sturdy little fish surrounded by sharks. Egypt, long dormant and cowed by Assyrian dominance, sniffed blood in the water. By the time Assyria’s capital fell in 612, Egyptian armies had poured into Canaan. And in 610, something unimaginable happened to the kingdom of Judah. King Josiah was killed by Egyptian forces. Josiah, to the bitter disappointment of his followers, was no luminary to guide them into peace and prosperity. He was just another sad moment in the history of Canaan. And the story would soon grow even more tragic. [music]

Judah, 610-586 BCE

There’s just one more group in the broad cast of characters that concerns us today. This group is the Babylonians. Once a subject kingdom of Assyria, Babylon, about fifty miles south of present-day Baghdad, rebelled and proved to be the coffin nail of the faltering Assyrian state, wresting control of much of the Mesopotamian heartland after 612. With control over the Tigris and Euphrates secured, the Babylonians turned their attention to the west, to the lucrative colonies Assyria had controlled.Once again, little Canaan was stuck between Egypt to the southwest and Mesopotamia to the east. The tiny kingdom of Judah watched uncertainly as Egypt fell to Babylon. In the wake of King Josiah’s death, four Judahite kings ruled in quick succession. One of them rebelled against Babylon, and in 597 BCE, Babylonian forces swept through Canaan, destroying the coastal cities. A decade later, some of Judah’s crown cities had fallen, and the Babylonians turned their attention to Jerusalem. There, in the year 586, the great temple and sacred monuments of were pulverized, and the aristocracy and priesthood of Judah were forcibly relocated to Babylon. The promise of King Josiah – that luminous vision of a Canaanite kingdom united beneath the mantle of Yahweh, must have seemed all but impossible. The hopes of that ancient hill tribe that called itself Israel, at least as old as 1207, were shattered by the horrors of the 580s. Compressed into the memories of a handful of generations were conquests by Egypt, Aramaeans, waves and waves of Assyrians, then Egyptians again, and then Babylonians. But bitterest of all – bitterest for that generation who had lived in the court of King Josiah and had dared to hope that their small land might be pious and flourish – was that this generation saw their temple obliterated in 586 BCE, their political and cultural center taken over, and that the priestly class of this generation was taken to a foreign land far to the east, a land with strange gods and customs, a land that regarded the Canaanite provincials as pitiful and of little consequence.

In Babylon, a core of Judah’s exiled aristocrats and clergy remained a tightly knit community of expatriates. Outside of Babylon, exiled Judahites immigrated elsewhere. Jewish civilization would return to Canaan, and flourish there once more, after the Achaemenid Persians assumed control of Mesopotamia in 539 BCE. But this is a good stopping point for the present. Any coursework you’d take on Biblical History would start with the pre-exilic period, or the period before the Judahites were exiled to Babylon between 586 and 539 BCE, and I think we’ve done a decent job exploring this period. We learned about the first written mention of Israel on the Merneptah Stele in 1207 BCE, and how the ancient highland communities around Shiloh in the Mountains of Judaea are modern archaeology’s best guess at the earliest ancestors of the Israelites. We learned how the Bronze Age collapse shook off Egyptian control over Canaan, and how the population center of Israel to the north, centered in the capital of Samaria, flourished for a century and a half before being destroyed by Assyria around 720 BCE. We learned that the survivors of this destruction migrated southward to Judah, where they brought skills and prosperity to a region that had up to that point barely been populated, and how Judah enjoyed a tremendous rise over the next century down to the late 600s, up until Egypt, and after it, Babylon thwarted the young civilization’s growth. This is the history of the pre-exilic period, and the overall story of the two kingdoms so often mentioned in the Tanakh, Israel in the north, and Judah in the south. [music]

Survey Archaeology and Historicist Scholarship: Newer Approaches to the Bible

If you know the Old Testament well, you know that the story I just told is somewhat out of line with the one told there, especially in the books of Exodus, Numbers, Joshua, Judges, Samuel, and Kings. You will notice that there was no mention of plagues of locusts, nor the decimation of the firstborn of Egypt. There was no mention of Moses, nor a 600,000 strong population of Israelites crossing over the Jordan to begin conquering the territory of Canaan under the leadership of Joshua and the Judges. There was no mention of this war of conquest, in which sizable Middle Bronze Age cities up and down the breadth of modern-day Israel were destroyed by powerful armies of Israelites. There was no mention of David, nor of Solomon, with his warehouse of a thousand wives and prostitutes, nor his multibillion-dollar income, nor the opulent monumental constructions he is said to have bankrolled around Jerusalem.The story that I’ve told you in this episode has been based on archaeology, rather than the narratives of the Tanakh. And archaeology has evolved substantially over the past few generations. The Mycenaean period excavations of the German archaeologist Heinrich Schliemann, which began in the 1870s, were geared toward finding the sites mentioned in Homeric poetry – most of all Troy. The assumption was that Homer’s poems were accurate descriptions of real historical events, and that a canny archaeologist, with the right crew, could actually pinpoint and unearth material evidence of what was set down in ancient Greek poetry. In much the same way, the first phase of Biblical archaeology was geared toward finding sites, and even specific artifacts mentioned in the Old Testament. In this first phase, scholars and archaeologists would locate a verse or chapter in the Bible, then, shovels and picks in hand, hurry out to a dig site to try and prove that they’d found conclusive material evidence of this or that event in the Old Testament. There have been over 170 expeditions to find Noah’s Ark on the slopes of Mount Ararat, and they continue into the present day, demonstrating that this first phase of Biblical archaeology is still alive and well.

But in the 1960s, a new phase of archaeology began in the hill country of what was once known as Canaan. And in this second phase of Biblical archaeology, scholars and archaeologists began to simply conduct systematic investigations of huge swaths of the Canaanite countryside and carefully catalog their findings. In what’s called survey archaeology, archaeologists chart their courses based on what’s already been found in the ground, rather than using an ancient text to guide their investigations. Survey archaeologists, rather than seeking out Samson’s jawbone, or David’s sling, or Deborah’s chariot, might approach a site, work there for a year, and then catalog results, concluding, “We found eighty-six pottery fragments here, along with a female fertility figurine, human and animal remains, a shell necklace, and some stone tools.” Or, “We found four ostraca, covered in mostly unreadable Aramaic datable to the Omride period, an iron bit of Hittite design, and stone etching that seems to be of Baal’s sister Anat.” The strictly empirical approach of survey archaeology is perhaps less exciting and spectacular than sending another expedition of hopefuls out to find Noah’s Ark, but its results are more systematically produced and less liable to hopeful conjecture.

Just as survey archaeology has slowly supplanted the tomb raiding and treasure hunting of previous generations, what we call historical criticism has gradually become a fixture in modern scholarly study of the Bible. Over the course of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, German scholars like F.C. Bauer, and after him William Wrede and Adolf von Harnack began trying to understand the roots of Biblical books in their historical context. For us today, particularly those of us inclined to listen to a podcast with the title Literature and History, the notion that history is important to the understanding of books is pretty obvious. Nevertheless, for long periods of Judaism and Christianity, Biblical hermeneutics, or the interpretation of the Bible, was more likely to rest on the understandings of any given theologian, rather than research into historical context. In Book 12 Augustine’s Confessions, in an absolutely enormous analysis of the first verses of Genesis, Augustine writes that no one will ever know what the book’s human writer was thinking when the verses were being set down under divine inspiration, that it’s disingenuous for anyone to allege that they do know, and by extension, that thinking of sacred texts as products of their cultural environments is a less reliable way of understanding them than just having faith that they were written under divine inspiration.11 Comparing verses of the Bible to springs that yield more and more meanings and interpretations the more they’re studied, Augustine, like so many of his predecessors and successors, was more interested in having the Tanakh speak to him and support his theological views than in understanding it as the product of a very ancient culture whose ideology had significant differences from his own.

I mention Augustine here for good reason. The second most famous Christian theologian after Paul, Augustine lived from 354-430, through a period of irreversible catastrophe for the western Roman Empire. I imagine we will reach his work around the hundredth episode of this podcast, and it is, to me, the fifth century CE during which both Late Antique Christian theology and Amoraic period work on the Talmud began to make Catholicism and Judaism, respectively, decisively start to look pretty close to the way that they still look like today. The two religions, put plainly, took a long, long time to develop – a lot longer than most of us realize. The Old Testament’s creation spanned, very roughly speaking, the five hundred years between the 600s and the 100s BCE. The New Testament was set down between about 50 and 110 CE. And I think the reason that so many of us open a Bible with the intention of reading it, and then give up, is a very basic misunderstanding of what the Bible is.

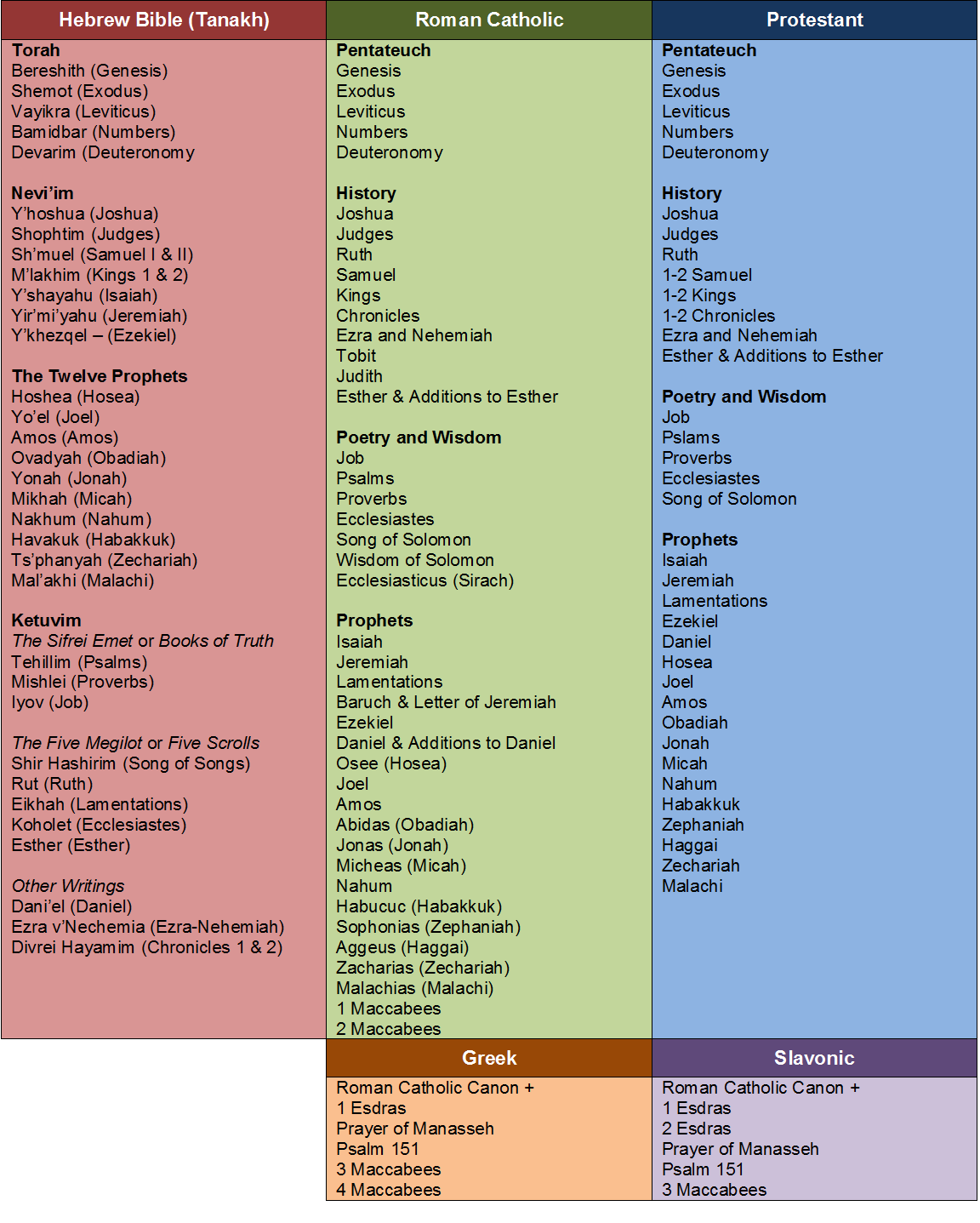

The Canons of the Old Testament. There are more canons and more apocrypha, but this is nonetheless a decent infographic I made for myself when I was first going through the OT and apocrypha.

What makes things even more complicated for many of us is the organization of the Christian Old Testaments. Unlike in what we might find in an anthology of literature today, the books of the Roman Catholic and Protestant Old Testament canons are not arranged in the chronological order that biblical scholars today believe they were written. These Christian canons stick Second Temple texts, like Ruth and Chronicles, in the middle of the older historical books. Very old prophetic books, like Amos, Hosea and Isaiah, are in Christian Old Testaments actually placed before considerably younger poetic and wisdom books, like Ecclesiastes and the Song of Songs. This is all relatively common knowledge, and not intended as a criticism of Christianity’s Old Testament canons. It’s just that when, as newcomers, we open an Old Testament, we end up getting some younger books closer to the front, and older books closer to the end, which can have the effect of making a challenging text even more challenging still.12

Well, anyway, let’s zoom out. In addition to telling you about the history of Iron Age Canaan during the preexilic period in this program, I also wanted to tell you a bit about developments in modern biblical archaeology and biblical scholarship. These developments have made understanding the Old Testament substantially easier, following the last two generations of work in religious studies departments and archaeological sites. The Bible has the odd distinction of being the most ubiquitous book on earth, and at the same time, one which very few of us, if we’re being honest, have ever actually read. We are not – not one of us – Iron Age Judahites, embittered against the diminished fortunes of our kingdom and familiar with a who’s-who of the peoples of Canaan and its surroundings. We are not – again, not one of us – bitterly upset at the thought that our brethren are not making their animal sacrifices at the Jerusalem Temple. There are broad stretches of the Tanakh that are as moving and profound as they were in ancient times. There are other broad stretches that are the exotic remnants of a bygone Iron Age civilization. And it is the latter, I think, with which we need the most help upfront – hence our episode today, on the ancient history of a land once called Canaan. [music]

Moving on to the Tanakh Itself

Well that, folks, concludes our fairly short tour of Canaanite history during the Iron Age. We learned about the earliest evidence of a people called the Israelites living there, both in ancient inscriptions as well as the material archaeological record. We learned about the two kingdoms central to the Tanakh’s story – Israel to the north, and Judah to the south – and how their fortunes rose and fell over the centuries between about 900 and 600 BCE. We learned about how Biblical archaeology matured over the course of the mid twentieth century, and how today’s Biblical scholarship, following traditions that began in the late nineteenth century, is much more interested in the historical contexts that gave rise to various books. Archaeology and modern Biblical scholarship will continue to be useful tools for us as we actually open an Old Testament next time, and get a sense of the overall architecture of the book.Over the course of this program, we dove pretty quickly into the history behind the Old Testament. Even if you’re a keen listener, if you’re new to the Bible, I imagine there were a few flurries of proper nouns here and there that left you puzzled. My apologies for that, but when we put the Tanakh on our desks, we are dealing with a huge book that’s part of multiple theological traditions and has a lot of history behind it, as well, and to put it simply, there’s a lot that needs to be introduced, all at once. However, in the next show, we’ll meet the older books of the Bible in a very simple fashion, grouping them into four main parts, and we’ll get a sense of the book’s overall contents. I think that too many of us who take a stab at reading the Bible march bravely into the creation story of Genesis, and then run out of steam before we ever even get to Exodus. What I’ll do next time is summarize the whole Old Testament, and talk about its organization, and the various versions of the Old Testament that are used by major world religions today. By the end of the next episode, you’ll know a bit about the history of Canaan, the general group of people who produced the Tanakh, and the contents and structure of this singularly important book.

Thanks for listening to Literature and History. There’s a quiz on this program available in the “Details” section of your podcast app if you want to review what you learned. And I’d like to close with a song – as always, skip it if you’d like.

Still listening? This song is a little tune to celebrate the fact that we’re about to read the Bible. I mean read it – not generalize about it, not say what its teachings are and how they should be applied, and not tell anyone what they ought to believe. I mean, we’re just going to crack that book open, and start combing through it. I hope you like this silly little ditty, and I’ll see you next time, with Episode 16: Four Main Parts.

References

2.^ As the Uluburun shipwreck (dated to about 1305 BCE), which we discussed in a previous episode, demonstrated.

3.^ The Literature of Ancient Egypt. Ed. William Kelly Simpson, et. al. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2003, p. 359.

4.^ Ibid, p. 359.

5.^ For a good summary of Sheshonq and the Ways of Horus, see Chapter 20 of Wilkinson, Toby. The Rise and Fall of Ancient Egypt. New York: Random House, Inc., 2010.

6.^ See Aharoni, Yohanan. The Land of the Bible: A Historical Geography (1967), Investigations at Lachish: The Sanctuary and the Residency (1975).

8.^ Matthews, Victor Harold. Old Testament Parallels: Laws and Stories from the Ancient Near East. Paulist Press, Third Ed. Copyright 2007. Kindle Edition, Location 1389.

9.^ Talmudic Aramaic of the Bavli is, needless to say, vastly different than what would have been spoken in present-day Syria in the 800s BCE, but the language had quite a long staying power, notwithstanding the fact that knowledge of it today only exists in very specialized circles.

10.^ The code is preserved and put in parallel with regulations in Leviticus, Numbers and Deuteronomy in Matthews (2007), Location 971.

11.^ The discussion is in 12.25-8.

12.^ The Tanakh, conversely – and this time I specifically mean the Tanakh that sits in today’s synagogues – is organized with much more attention to the order in which its books were originally written, the Five Megilot and Other Writings portions containing Second Temple and Hellenistic period books.