Episode 16: Four Main Parts

The Old Testament, Part 2 of 10. There are tons of books, thousands of proper nouns, and many versions of the Old Testament. But all of it fits into four main parts.

| Read Transcription | References and Notes |

| Episode Quiz | Episode Song |

| Episode on Spotify | Episode on Apple Podcasts |

| Previous Show | Next Show |

The Superstructure of the Old Testament

Hello, and welcome to Literature and History. Episode 16: Four Main Parts. This is the second of ten shows that we’ll do on the Old Testament. And in this program, we’re going to talk about the overall superstructure of the Old Testament, dividing it into four main parts – the Pentateuch, the Historical Books, the Wisdom Books, and the Prophetic Books. Our goal, by the end of this program is to have established a high-level view of first, the different Old Testament canons, and then, the content and organization of those books common to all Old Testaments.In the previous show, we learned all about Canaan, that small strip of coastal land between Egypt and Mesopotamia. We learned about two kingdoms there, Israel in the north and Judah in the south, both of which were, as early as 1207 BCE associated, with an indigenous people called the Israelites, who came down out of the eastern highlands and onto the coastal plain after the Bronze Age Collapse destabilized the power structure once dominated by Egypt. And we learned that in both north and south, from the late 800s down to the early 500s BCE, these Israelites faced wave upon wave of invasions by foreigners – Egyptians, then Aramaic Syrians, then generations of Assyrians, then Egyptians again, and finally, Babylonians. We voyaged through the history of Canaan up until the 580s, when, after years of being pummeled by foreign conquests, the nobles and priests of the southern kingdom of Judah were relocated to modern day Iraq in what is commonly called the Babylonian Captivity. And, most importantly, we paid very close attention to those crucial years between about 630 and 580, when a generation came to maturity in the court of a king called Josiah – a generation that almost certainly wrote much of the Old Testament. With that important prep work accomplished, it’s now time to set some of the various Old Testaments on our desk, and take a look at what’s inside. For the sake of candidness, and general respect for a wide and diverse listenership, let me talk for just a moment about our approach to the Old Testament in this show.

This Show’s Approach to the Old Testament

This podcast is called Literature and History. And our primary objective with the Old Testament, beyond reading its books, is to understand it in the context of Ancient Near Eastern cultural history, especially ancient Jewish history, during the final millennium BCE. This is an old approach to the Tanakh, dating back to nineteenth- and turn-of-the-century German scholars like F.C. Bauer, William Wrede and Adolf von Harnack, and made possible by archaeological and textual discoveries that have taken place since the discovery of the Rosetta Stone in 1799, and philological knowledge and paleographic techniques that have developed over the past two centuries. The historicist approach to sacred writing, as it’s called, isn’t concerned with theological truths. It’s neither infallible, nor objective, but what it’s interested in is advancing hypotheses that link texts up with specific timeframes and contexts. So while I understand the Old Testament’s unique staying power as a piece of theology in different worship communities, I think that one of the ways – though it’s a more academic way – that we can appreciate, understand, and revere it, is to do so within the context of the immense historical framework that produced it, and the literary traditions of the Ancient Near East and Mediterranean.As I record this, I already have all ten of our episodes on the Old Testament written and completed. They come to about a hundred thousand words, and the music and recordings will create a connected narrative of around fifteen hours. Researching and writing these programs wasn’t my first go through the books of the Tanakh. But the extent to which I took my time, and immersed myself in the history and intertextual traditions of the Ancient Near East made the Old Testament come to life in ways that it never has before. So many books now have deep associations for me with events and in some cases cultural contexts that may have inspired them – the Prophetic Books and the Assyrian and Babylonian invasions, for instance; some of the narratives in Genesis and the Akkadian tablets of Nineveh and Ashur; Ecclesiastes and Ruth, and the comparative tranquility of the Persian period; the intellectual flowering of the Hellenistic Period, and parallels between Platonism, Stoic philosophy, and late books like 4 Maccabees; the growing Greek traditions of prose travel writing and the earliest Greek novels, and the novelistic architecture of later books like Esther, Tobit, and Jonah. The long story of the people who wrote the Old Testament is as great as any story that’s in the Old Testament. And in the episodes to come, I’m going weave them together, and share them with you.

So, to repeat what I said earlier. Our approach to this book is going to be historicist, and intertextual. No one will be converted, or unconverted to anything by it. We’ll be looking at the Tanakh in the context of its ancient history, rather than under the lens of later rabbinical or Christian commentaries. And two quick further notes. The first is that, as in the previous episode, I will be saying the tetragrammaton, YHWH, aloud, sometimes frequently, and particularly in an upcoming episode that deals extensively with what’s called the Documentary Hypothesis. It is common in contemporary Biblical scholarship, university lectures, and other podcasts that deal with theology and Bible studies to say aloud that sacred Hebrew name for God, and so I will do so, too, for the same practical and scholarly reasons that others do. To my devout Jewish listeners, I’m very sorry to break such a sacred rule in a series that’s about the Tanakh, and of course would never use the tetragrammaton in a Synagogue or at a friend’s Shabbat dinner or anything like that. Going forward, though, there are some areas of theology – the aforementioned Documentary Hypothesis, and much later, the rise of Nicene Trinitarianism and later Christological developments, where it is really helpful to have good, solid proper nouns when reading the Tanakh and New Testament’s descriptions of the deity carefully.

Finally, there is one other issue of terminology that we need to be conscientious about upfront. This is what we call the swath of land that presently includes Israel, Palestine, Lebanon, and some parts of Jordan and Syria. This area at the extreme eastern end of the Mediterranean has had a lot of names, names which have included Canaan, Samaria and Judah, Yehud, Judea, Palaestina Prima, Jund Filasṭīn, Acre, Old Yishuv, Palestine, and today, Israel, and what these many names have described have been larger and smaller swathes of territory, depending on which century one is studying. As we discuss Biblical history throughout our show, I will do my best to use period correct names for what is sometimes called the Levant today – in other words, Canaan prior to the two kingdoms period, Samaria and Judah during the pre-exilic period, and later, Judea during the Roman period prior to Hadrian, and Palaestina Prima for the Roman period after Hadrian, and so on. I am here to discuss the Old Testament and its historical roots, and definitely not to comment on contemporary history, and so if my terminology for this land of many names strikes you the wrong way at one juncture or another, I apologize in advance.

That’s enough posturing and caveats upfront for one episode. With respect to all, then, let’s gather around the most influential book ever written, and open up to the table of contents. [music]

Old Testament, New Testament, and Apocrypha: Their Compositional Timeframes and Length

We will begin by talking about the overall structure of the Bible – not just the Old Testament, but the entire Bible. To those of us raised Jewish or Christian, or those of us who have read a Bible for other reasons, the notion that different Bibles and Old Testaments have different books in different orders is familiar. For those of us unfamiliar with the Bible, though, an explanation of which books are in which Old Testaments in which order would not be coherent upfront here. So, for utilitarian purposes, because I want this to be comprehensible to total newcomers to the Bible, to pitch to the middle of you listening out there, and because our podcast is ultimately going to be on the subject of Anglophone literature, I am going to be mostly talking about the Protestant and Catholic Old Testaments in the remainder of this show, in terms of the organization of books therein. These ultimately had the most impact on Anglophone literature, and the order of the books, conveniently, is similar in both canons.

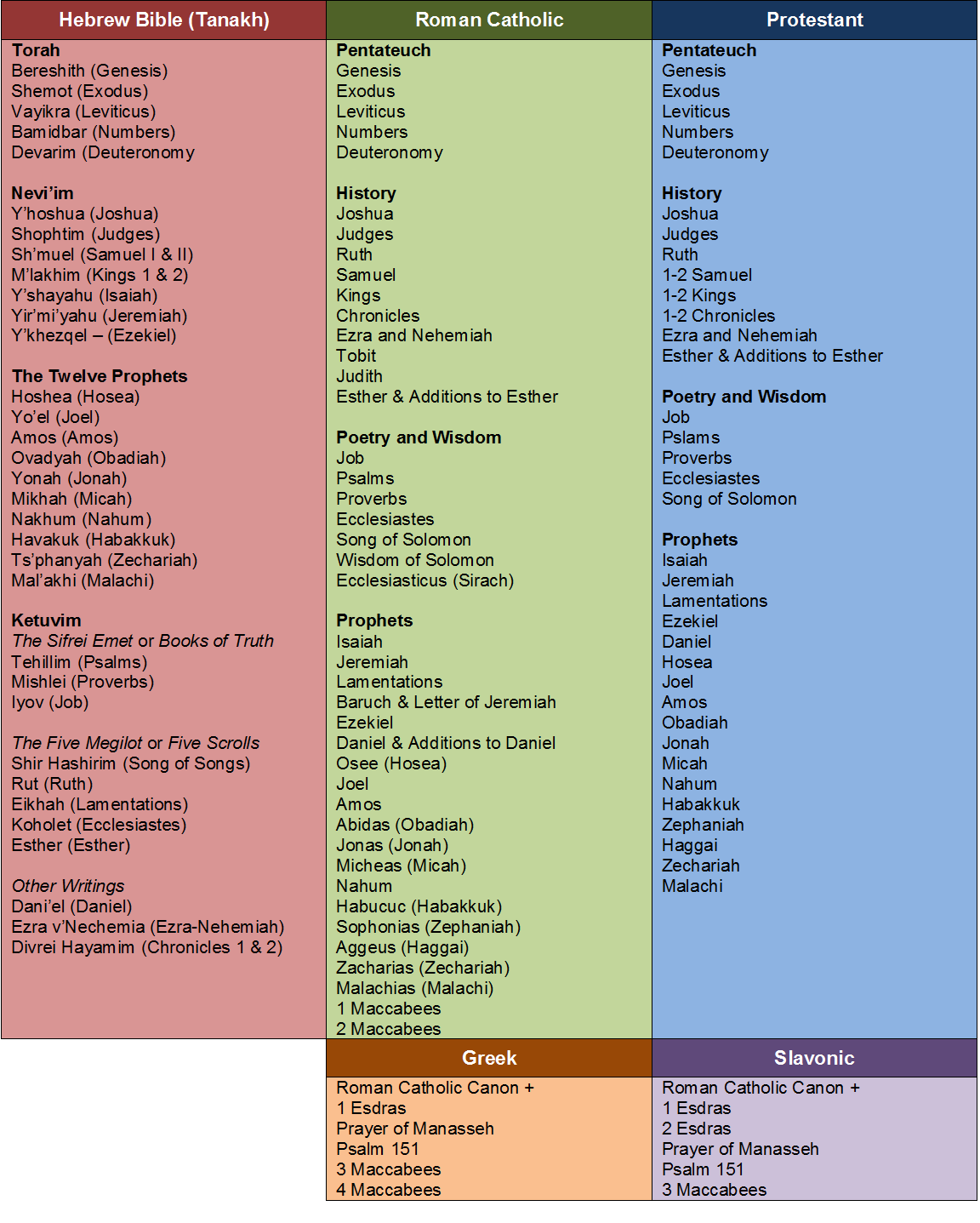

The main canons of the Old Testament. I made this infographic when reading the book for the first time. While it captures a lot of the complexity of the Old Testament’s canonization, it doesn’t really give a comparable idea of the ocean of Second Temple period and Early Christian apocryphal literature outside of the Deuterocanonical books and those in the Greek and Slavonic bibles.

A moment ago, we learned that some canons are larger than others. The reason that this is the case is that, for instance, the Protestant canon excludes certain Old Testament books included in the Catholic canon, deeming these excluded books to be Apocryphal. In turn, the Catholic canon excludes certain books that are in the Greek, Slavonic, and Tewahedo canons. And a gigantic amount of Jewish and Christian sacred writings have now been found, sorted, and translated, that are not canonical in any Bible, notwithstanding the fact that these apocryphal writings deal with sacred subjects and were written in the same styles and timeframes as their canonized counterparts. Your host is especially interested in apocryphal literature – who wouldn’t want to read texts that rabbis and church fathers deemed unsuitable for canonization? – and I suspect we’ll go through a lot of Apocryphal literature on down the road. To be clear, “apocryphal” doesn’t necessarily mean something like “evil” or “forbidden” – Jewish and Christian theologians and clerics over the past two thousand years have naturally had healthy interests in sacred writings that didn’t necessarily make it into their canons. Apocryphal, though it does mean “hidden” in Greek, might better be understood to just mean “not in our religion’s canon, but maybe otherwise kind of cool and okay.” Alright, enough about the slippery subject of the Apocrypha, for now. For the moment, let’s stick with those timeworn Catholic and Protestant Bibles, and keep things very simple upfront here.

The Old Testament, New Testament, and the more common Apocrypha – this is a group of texts called the Deuterocanonical Books, only apocryphal in the Protestant and Hebrew Bible canons, together weigh in at about 915,000 words, depending on the translation. To picture how long this is – and by this I mean a standard Catholic Bible – the modern print novel has between 300 and 400 words on each page. This means that if the entire Catholic Bible were printed not in the double column, tiny font manner that it usually is, but like a modern book, it would be somewhere between 3,000 and 3,660 pages long.

Focusing on just the Catholic Bible for just a moment longer, because it’s a very common book and it has a bit more stuff in it, let’s talk about the length of each of those parts in a Catholic Bible – the Old Testament, New Testament, and Apocrypha. Of those 3,000 or so pages, the vast majority are the Old Testament. With some 2,000 pages, the Old Testament dwarfs the rest of the Bible in size and density. Because it was produced over such a wide period by so many different sources, the Old Testament is more miscellaneous in language and contents than the other portions of the Bible. Though its opening books are a thousand years younger than Gilgamesh and the Atrahasis of Babylon, the Old Testament is nonetheless difficult from the beginning, and its rapid-fire alternations between storytelling and imperative instructions for self-conduct have challenged new readers for thousands of years. The New Testament, by comparison, is far shorter. There are only nine books in it that are of any significant length. Because the New Testament was produced in less than a century, as opposed to the many centuries it took to form the Old Testament, the 600 pages of the New Testament are a bit more stylistically and ideologically homogeneous. As to the length of the Apocrypha – well, this is an open question. There are hundreds of surviving apocryphal and pseudepigraphal works, some in their entirety, some fragmentary, written during the Second Temple period and deep into the early Christian period – pseudepigraphal meaning attributed to an ancient author but probably not written by that ancient author. Because, by definition, apocryphal literature is non-canonical, I can’t really give you a definite figure for the word count or page length of all of the apocryphal writings of Judaism and Christianity, but rest assured that we’ll talk lot about them on down the road.

So, let’s go a little deeper than just talking about the overall layout of a Bible and the length of its main sections. I’ve introduced the Old Testament, New Testament, and Apocrypha, the general timeframes and languages of their composition, and their length in the relatively middle-of-the-road Catholic Bible. These three overarching-sections – Old Testament, New Testament, and Apocrypha – are intelligible enough. But as we start to consider these three overarching sections in more detail, things get quite complicated, quite quickly. There are many Bibles. Their contents vary, and their internal organization varies. Without getting into granular subject of which books are included in which canons, let’s take a quick tour of some of the most influential Bibles in circulation today.

We’ll start at the beginning, with Judaism. Judaism’s Tanakh is divided into three main sections – the Torah, or Law, the Nevi’im, or Prophets, and the Ketuvim, or Writings. If you’ve been raised Catholic or Protestant, and look at the table of contents of a Tanakh in a synagogue, it looks like someone took the table of contents of your familiar Old Testament, moved everything around a bit, changed some titles, and, if you’re Catholic, removed the Deuterocanonical Books. The shortest Bible by far, the Tanakh of Judaism is the oldest anthology of scriptures sacred to Judaism or Christianity, and for students in yeshivas, or yeshivot studying to be rabbis, printed in the same language that it was composed in, two and a half thousand years ago.

While Judaism likely had a canon more or less formed by the close of the first century CE, the Christian Bible’s formation took longer. Let me briefly tell you about the length and breadth of six major bibles, currently in use today. The Tanakh – again, the Hebrew bible, is the first. It has 24 books. The other five major bibles will all be Christian ones that include the New Testament. Let’s put these five Christian bibles on our metaphorical desk, in order from smallest to largest, left to right. The shortest Christian canon is the Protestant canon. It has 66 books. It is a slimmed down Bible largely due to Martin Luther eliminating a large part of the Catholic Old Testament canon from what he saw as an ideal Christian Bible. The next shortest Christian Bible is the Catholic Bible, with 73 books. Moving to our right and onto longer Christian Bibles, the Greek Orthodox and Slavonic Bibles, which have regional variations, have about 78 books, although this number changes slightly depending on where you are. And finally, the longest Christian Bible of all, and really the one that offers the richest collection of Second Temple period Jewish texts is the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Bible, with 81 books.

The Long History of Judaism and Christianity’s Development

The Bible, then, is difficult because of its massiveness. It is difficult due to the fact that it refuses to hold still and be one thing, with even its major canons varying from one another and excluding fascinating apocryphal texts. If you were raised going to synagogue or church, this is all familiar information. But to leave the realm of the familiar, let’s enter Divinity School for just a moment, and I’ll take a stab at telling you the thousand year long story of the Bible’s composition, and this composition’s aftermath in one paragraph. Here’s that paragraph – it’s a long one.The oldest parts of the Bible, like the Song of Deborah in the Book of Judges, bear diction and syntax from the earliest known Hebrew, likely being oral poems as old as the 800s or even 900s BCE, passed down through generations before being embedded into the books of the Tanakh in the 600s and 500s BCE. These ancient songs are tendrils of Israel’s ancient past during the early Iron Age, as Israelites headed down onto the coastal plain and into the Jezreel valley following the Bronze Age collapse and sparred with other tribes, until they came to be a formative part of the kingdom centered in Samaria – that northern kingdom called Israel in the Bible. What happened over the next three centuries we covered in the previous show – waves of invaders, chiefly the Assyrians and Babylonians, caused the northern and southern kingdoms to fall. These events are the background of most of the Old Testament. But the return from the Babylonian Captivity in the 530s and 520s BCE, and the building of the Second Temple at Jerusalem – these events marked only the beginning of the Tanakh’s being written and redacted over the ensuing centuries. As Leonidas and his beefcake Spartan friends fought the Persian forces in the early 400s BCE in Greece, deep within the Persian territories, Jerusalem was peaceful and prosperous, as the book of Ecclesiastes suggests, and it began to show the imprint of Persian religion, as we see in the Book of Tobit. In 330 BCE, though, catastrophe struck again, when Alexander of Macedon wrecked the Persian Empire and left a mess in his wake, a mess that included a checkerboard of successor kingdoms, two of which, the Ptolemaic and Seleucid Empires, played tug-of-war with the civilization centered in Jerusalem for a long time, eventually resulting in conflicts like the one which we read about in the Books of Maccabees. One of the most far-reaching consequences of Alexander’s conquests between 334 and 323 BCE was that Koine Greek became the international language. Another was that the interstate chaos ultimately caused by Alexander’s conquests had a broad effect on Ancient Mediterranean ideologies for the next three centuries leading up to the birth of Christ. People didn’t want to sacrifice goats at their ancestral temples anymore. Many ancestral temples had been demolished by various imperial regimes, indigenous peoples had been deracinated and sold into slavery, and they continued to as Republican Rome gained ground during the 200s and 100s. As a result, citizens of the Ancient Near East and Mediterranean worlds began to seek out philosophies and cult religions not based on ethnic heritage or geographical center, but instead due to the intrinsic appeal of their various creeds – creeds centered on self-regulation and, connectedly, posthumous salvation – creeds like brawny Socratic self-reliance and all of its variants, stoicism, Epicureanism, mystery religions, the cults of Dionysus Zagreus, Egyptian Isis, Anatolian Cybele, and eventually, Jesus Christ – creeds that gave their adherents a sense of agency and security no matter who was king or emperor, and even if ancient temples were destroyed. Meanwhile, to the east of Jerusalem, Persian Zoroastrianism was a constant influence on Ancient Mediterranean ideology, later inspiring Christian sects like the Gnostics and Manichaeans, which, especially during the second century CE, profoundly influenced early Christianity. The Tanakh’s canon was probably solidified in Judaism by about the 90s CE.1 The New Testament canon isn’t first definitely described in surviving Christian writings until 367 CE.2 Throughout Late Antiquity, in Judaism, the development of the Oral Torah and Midrash, and then different phases of work on the Talmud added Halacha and Aggadah to Rabbinical Judaism, supplementing the Tanakh with a great deal of additional doctrine and clerical practices. And similarly, over the same period, work by important church Christian fathers like Tertullian, Jerome, and Augustine developed the doctrines of Christianity in response to clashes with Gnostics, Manichaeans, Arians, and other sects.

So that’s the story of the Bible’s expansive ideological background in a paragraph. It’s a story that leads from the tribal oral narratives of the early Israelites all the way to the lavishly cosmopolitan and educated provincial Roman world of Saint Paul and his colleagues, who wrote the New Testament 900 years later, and then the later Jewish and Christian theologians who continued to develop their respective religions’ doctrines into the 400s and 500s CE, and after. And that history is imbedded into every single Bible ever printed. The massive ideological and cultural evolutions that took place in the Mediterranean and greater Eurasian and North African worlds during the Bible’s centuries and centuries of composition are another reason, then, for its foreboding difficulty. The Bible itself not only refuses to be a single thing, with all of the variants of it that exist. And it is not only astoundingly long. Additionally, the ideology, or ideologies that it contains also form an unfolding story – a story about the Mediterranean and Ancient Near East, over a thousand-year period, a story with many characters, places, events, and striking twists of plot.

Luckily, we don’t need to dive into all of that at once. The Bible, after all, has a nucleus, a nucleus that Paul and Peter and John the Baptist and Jesus himself would have known, and that nucleus is the Old Testament books found in the Tanakh, which are also found in every Christian Bible, as well. This group of core books is often called the Protocanonical books – the books that are in every Bible, Jewish as well as Christian. So now, we’re going to put away the New Testament for a long time, and bracket the Apocrypha for quite a while, too. We’ll take the history piecemeal as it comes. And from here on out today, our plan with the Old Testament will be to understand it as divisible into four main parts. The protocanonical books included variously in the different versions of the Old Testament are ordered in different configurations, depending on whose Bible you’re holding. But mainline Biblical scholarship commonly divides any given Old Testament into four main parts – great big groupings of books all sharing a kernel of common characteristics. Let’s go over those four main parts. [music]

Four Main Parts, Part 1: The Pentateuch

The first main part of the Old Testament has a couple of names. The Hebrew name is the Torat Moshe, which means the Law of Moses, or more commonly Torah. The other name for this bundle books is the Greek word Pentateuch, from the words πέντε (pénte), or five, and τεῦχος (teûkhos), or scrolls – five scrolls. The “five scrolls” in question are Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, and Deuteronomy – the first five books of all Bibles. By chapter count, the Torah makes up about 20% of the Old Testament. Because they start the whole thing off, and they are in all major bibles, the books of the Pentateuch are probably the most heavily read and studied texts in human history. So, what’s in the Pentateuch?A lot of the Pentateuch is a narrative, or story – a story that’s ultimately about a family – a singular family, chosen by God to be the progenitors of an entire nation. The narrative portion of the Pentateuch concerns the generations that lead up to Abraham, the patriarch of the Israelites, and then after that, the generations that follow him. It tells of the earliest Israelites’ trials and tribulations, in the days when the world was still new, and it ends just as they stand on the shores of their promised land of Canaan, before they enter and begin to settle there. It’s the origin story of an entire people, a people whom it presupposes are at the center of all history.

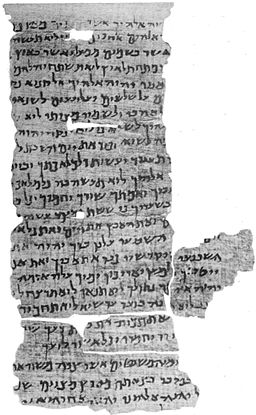

The Nash Papyrus, acquired in Egypt in 1898, contains Exodus 20:2-17 and Deuteronomy 4:45. The text is usually dated to the 100s BCE, and is closer to the Septuagint than the Hebrew Masoretic text. This was the earliest fragment of the Old Testament known prior to the discovery of the Dead Sea Scrolls in 1946.

But the narrative portion, or the story of the first five books of the Bible, is only half of what’s in the Pentateuch. In addition to the great family saga of the earliest Israelites, the Pentateuch also contains a huge amount of instructional material, written by an unspecified narrator, telling the reader what to do, and how to do it, in order to stay in the good graces of the Old Testament God and his priests. The instructional portion of the Pentateuch, commonly called the “Priestly” portion, tells you how to design the holy tabernacle, or sacred tent of the Israelites. It goes into exhaustive detail about animal sacrifice, cleanliness, and civic conduct. Verse after verse after verse specifies how a bull must be clean before it is sacrificed, a turtledove’s blood must be splashed on the altar in just this fashion, that this tapestry must be this many cubits long in the tabernacle, that we must not marry our siblings, and so on. The priestly section of the Pentateuch is the early brick wall that stops many of us from getting through the Bible. We can see a certain gloomy majesty in the flood story of Noah. We can sense the wonder and adventure of the journeys of Abraham, and the drama of Moses interceding on behalf of the people of Israel in the desert of Sinai. But when the priestly section of the Pentateuch starts telling you that you need to take a good, long look the testicles of a bull you bring to the temple to be sacrificed, and that those testicles need to be nice and unblemished, you start to become conscious of a wide historical and situational difference between your timeframe and the Pentateuch’s. Piety, for the modern Jew or Christian, does not mean leaning down and inspecting the scrotum of a hoofed mammal before taking it to be butchered by holy men. Put simply, and I hope, neutrally, to the modern reader some sections of the Pentateuch are far more inspiring, entertaining, and relatable than others. In Episode 18, then, titled “The 613 Commandments,” we’ll explore the expansive instructional materials in the Pentateuch, and similar material that survives from ancient Assyria and Babylon.

So, the Torah, or Pentateuch, is the first of the four main parts of the Old Testament. It tells the epic family story of Abraham, and his progenitors, and his descendants, and offers some very specific instructions for sacrifice, cleanliness, and holiness in the Iron Age coastal strip called Canaan, some of which are stirring and ethically coherent, and others which are not quite so relevant to modern life, to put it diplomatically. The narrative portion, and the instructional portion of Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, and Deuteronomy – these are the two portions of the Pentateuch, the first of our four main parts of the Old Testament. Let’s go on to the next. [music]

Four Main Parts, Part 2: The Historical Books

The central narrative of the Historical Books is the tale of two kingdoms, headquartered in Samaria (that’s the northern kingdom, Israel) and Jerusalem (that’s the southern kingdom, Judah). Map by Richardprins.

Although this is a very basic fact about the Old Testament, and it’s probably clear by now, I’ll pause for a moment, and say it anyway. Much of the Old Testament is simply national history. If you open, say, the book of Second Kings expecting to hear praises and hymns to God, sometimes you’ll read for a long time before you find anything theological. I’d advise you, early on, to think of the Historical Books as a national diary just as much as a religious text, the diary of a small civilization that persisted against many odds in a violent, chaotic period of Ancient Near Eastern history. What is surprising to many readers of the Old Testament is that it is not, like the New Testament or Qur’an, a book that offers joy and salvation to anyone who is devout. The vast bulk of the Old Testament does not proselytize or promise, but instead tells the conflicted story of the history of a single ethnic group. Accepting some psalms and an odd group of verses here and there, it’s not engineered to compel you to accept the Old Testament God into your heart – it’s built to share the story of the early Israelites, rationalize what’s happened to them, and reconcile them to their sufferings and sacrifices.

Although the history in the Old Testament is understandably biased, sometimes contradicted by archaeological discoveries, and sometimes full of revealing anachronisms, it’s important to remember that the Historical Books were perhaps the first concentrated effort of a people to draft a comprehensive national narrative. That, in itself, would make the Historical Books a world-famous text, even if they weren’t affixed to the other sections of the Old Testament.

Being composed during and after the reign of King Josiah, the Historical Books are over a hundred years older than Herodotus’ Histories. Three episodes from now, in Episode 19, there will be a show called “The One Who Struggles with God.” In that upcoming show, I will cover the Historical Books and related work in Biblical archaeology that variously supports and contradicts what’s printed in the Bible, a fascinating subject for many reasons. So, that’s a quick introduction to the Historical Books. [music]

Four Main Parts, Part 3: The Poetic and Wisdom Books

So the Pentateuch is the first big section of the Old Testament, and then the Historical Books. Let’s go on to the next one. Section 3 of 4 is what we call the “Poetic and Wisdom Books.” These books, by chapter count, make up about a tiny little 10% of the Old Testament, although if you include the 150 Psalms as chapters, that number jumps way up to 25%. Earlier in this podcast, I introduced the wisdom literature of Ancient Egypt, and the wisdom literature of the first millennium BCE more generally. The Poetic and Wisdom Books of the Bible are Ancient Israel’s main contribution to the genre of wisdom literature – literature that is philosophical nature and meditates on the human condition in various ways, depending on who’s writing it. The Bible’s Poetic and Wisdom Books, which include Job, Psalms, Proverbs, Ecclesiastes, and the Song of Solomon, or Song of Songs, are of special interest to literary scholars, like me. They’re often gorgeously written, with dense figurative language and intellectual energy. With powerful literary craftsmanship, and a philosophical restlessness that in places seems to scratch at the bounds of monotheism, the Poetic and Wisdom books are one of the more accessible parts of the Old Testament, and so we’re going to spend a disproportionate amount of time with them.One of the really magical things about the poetic and wisdom books is that you can read them in isolation from the rest of the Old Testament and still understand and enjoy them. You don’t, for instance, need to know the whole grand history of the Israelites in order to understand that many of the Psalms are well-constructed poems. The Psalms are filled with compressed bursts of meaning. Often an impassioned first-person speaker pleads for help, or expresses awe at the vastness of God and the universe, or hopes for retribution for wrongs done to him. The Psalms are, for the intimacy of their speakers, and intensity of their messages, frequently immediately comprehensible. In this podcast so far, the poetry that we’ve explored is very different from the Psalms. Understanding Homer or Hesiod or ancient Babylonian religious texts requires familiarity with a small panorama of human and mythological figures, referenced variously throughout their pages. The Psalms, however, are usually simpler. There is a speaker, and an addressee – most often God, and a series of parallel lines that develop an idea or image. And that’s it. Whether or not you share their specific strain of monotheism, the Psalms communicate an essentially human core of emotional experiences – hope, anguish, reverence, and fury – that are the same today as they were back during the Iron Age. So the 150, or 151 by some counts Psalms have always been one of the more broadly accessible parts of the Old Testament. We’ll cover the Psalms – the most heavily read poems on Earth – in Episode 21, in a show called “The Bible’s Magic Trick.”

“Miserable comforters are you all!” (Job 16:2), says Job to his supposed comrades. This 1805 illustration by William Blake demonstrates the Poetic and Wisdom books’ particularly heavy influence on Anglophone literary history – especially Job, Psalms, and Ecclesiastes.

While I won’t spend much time with Proverbs, which we already have more or less covered with the Ancient Egyptian wisdom literature of the Instructions of Amenemope and ‘Onchsheshonqy, the next part of the poetic and wisdom books is the Book of Ecclesiastes. Ecclesiastes is very short – just twelve chapters, but it’s another one of the Old Testament’s more philosophically robust contributions to world history. Ecclesiastes, a long speech delivered by a mysterious figure called “the gatherer,” or “the teacher,” or “the preacher,” questions the point of existence. Everything, Ecclesiastes tells us, is as meaningless and ephemeral as a single breath. Everything that we do, Ecclesiastes tell us and try to do, that we fear and hope for doesn’t amount to much. Just as the Book of Job is surprisingly modern in its engagement with the problem of evil, Ecclesiastes, with its aloof indifference to earthly life, often seems like a piece writing from a far later era – a piece of stoic or even existential philosophy more than an expression of religious devoutness. In Episode 22, entitled “Fatalism,” we’re going to learn about the remarkable confluence of philosophical traditions that came together in Persian period Jerusalem, and, connectedly, the Book of Ecclesiastes, and, before the Book of Revelation and Catholicism came along and carefully codified heaven and hell, consider what the Tanakh has to say about the meaning of life on earth.

The final poetic and wisdom book is the Song of Solomon, or the Song of Songs. At just eight chapters, it’s a tiny book. But the Song of Songs has engendered centuries and centuries of controversy. Because the Song of Songs doesn’t – on the surface at least – seem to be a religious text at all. There’s no mention of the Old Testament God, or of sacrifice, or fidelity to Iron Age Judah, or any of those core strains that propel the rest of the Old Testament along. The Song of Songs is a love poem that runs as a dialogue between a male and female speaker. Judaism and Christianity have come up with interpretations of the Song of Songs that work to explain what it’s doing in the Old Testament, and their interpretations are every bit as interesting as the book itself. In Episode 23, “Love, Desire, Exegesis,” we’ll learn all about this book of the Old Testament, and the ways it’s been interpreted.

So that’s the poetic and wisdom books – Psalms, Job, Proverbs, Ecclesiastes, and the Song of Songs. Because they’ve been so influential to world literature, and because they’re more thematically diverse than many other sections of the Old Testament, we’re, again, going to spend a disproportionate amount of time with them. So with three out of four of our main parts done, let’s go on to the last one. [music]

Four Main Parts, Part 4: The Prophetic Books

Let’s quickly talk about the Prophetic Books. By chapter count, they make up about 27% of the Old Testament. There are seventeen Prophetic Books, but by far the most important are just three – those thought to have been composed by the eighth-century prophet Isaiah, his sixth-century successor Jeremiah, and a man roughly the contemporary of Jeremiah, Ezekiel. If the Historical Books chronicle the kings and major events in Ancient Israel’s history, the Prophetic Books record the psychological ramifications of these events. In a word, as generations of Ancient Israelites found themselves cornered, conquered, and humiliated, their prophets attempted to cope with geopolitical setbacks in their religious writings. The Prophetic Books are thus frequently angry, blaming the people of Ancient Israel for their own sufferings, furiously condemning Israel’s enemies for impiety, and predicting a coming period of vengeance and/or righteousness. Written in first person singular, and often alternating rapidly between vigorous anger and vibrant visions of the future, the Prophetic Books are one of the darker and more thematically repetitious portions of the Tanakh.

A detail of the Great Isaiah Scroll, the most complete of the Dead Sea Scrolls. Probably written by an Essene sect in the 100s BCE, contemporary with younger books of the Old Testament like Maccabees, Daniel, and Judith, and over in Rome, the plays of Terence and tracts of Cato the Elder.

One of the main reasons has to do with what the Prophetic Books prophesize. In the midst of the cornucopia of violent punishments envisioned for both Israelites and their opponents as a result of various transgressions, the Prophetic Books, somewhat less often, envision a better future for Israel. At four or five points in the first prophetic book, the Book of Isaiah, especially Chapters 52 and 53, there are references to a mysterious redeemer figure who will some day come and lead the Judahites into an era of much greater prosperity. And a reference to a “messenger of the covenant” in the final prophetic book – the Book of Malachi, also seems to indicate the impending arrival of a savior figure. The Jewish midrash, and commentaries in the Talmud, have their own explanations for these passages in the Prophetic Books. But to Christians, including the authors of the New Testament themselves, the descriptions of savior figures, in Isaiah, Malachi, and a couple of other prophetic books are referencing the coming of Jesus. So, put plainly, Christian Bibles place those Prophetic Books last because that way, they form a logical segue to the stories of Jesus in the Gospels of the New Testament.

I’m going to cover all the Prophetic Books in a single episode – Episode 24, “God May Relent.” There are individual prophetic books that stand out from the crowd. Daniel and Jonah, for instance, are formally distinguished by the fact that they’re written in third person omniscient and tell splendid little short stories with memorable plots. Portions of Ezekiel are famous their visionary and almost hallucinatory imagery. Amos is notoriously miscellaneous – a sort of hodgepodge of instruction. However, when you remove these, the Prophetic Books start to become indistinguishable from one another, unless you’re a specialist on the subject in some way or another. As I said, stretching across hundreds of pages are denunciations of foreign peoples, castigations of the Israelites themselves, and less often, hopeful statements about the future. Because of the repetitious nature of these books, I feel like we can cover them in a single episode.

So that’s it – the four main parts – the Pentateuch, Historical Books, Poetic and Wisdom Books, and the Prophetic Books. To close out today’s show, I want to talk a little bit about some of the resources I’m going to be using, in addition to the Old Testament, to help give context to it. [music]

Bible Reading Over the Generations

The first Bible that I ever read is one that will come up often in this show, and one that I still use today. It’s called the New Oxford Annotated Bible. It has copious footnotes that deal with everything from translation issues to textual variants to cultural context to intertextual comparisons. The New Oxford Bible also has introductions to each book, maps, and essays at the end that offer further information about Biblical history and geography, contemporary Biblical scholarship, the history of its interpretation, and that kind of thing. And it contains a respectable amount of apocrypha, as well – the entire Deuterocanon of the Catholic Bible as well as some books otherwise only found in Greek and Slavonic Bibles. The New Oxford Annotated Bible uses what’s called the NRSV, or New Revised Standard Version translation, which is standard in seminary and divinity schools today, and overall the New Oxford Annotated Bible is a common and uncontroversial part of a modern theological library.It is an especially friendly book if you’re an outsider to Judaism and Christianity. I have relied on it so extensively throughout my own years of learning about the Abrahamic religions that it’s hard for me to imagine reading an unannotated Bible, and sometimes it’s easy to forget just how much collaborative and interdenominational scholarship goes into offering laypeople just one tentative timeframe to date just one book, or just one possible intercultural textual parallel to just a single verse. The scholarly work of the past century and a half has opened up the history of the Bible in ways that were not accessible to previous generations. Speaking of previous generations, let’s travel back in time, to – say – 1905, and try to imagine what reading the Bible would have been like then.

Sometimes, in my mind, I try to picture someone of my great grandma’s generation – someone born a decade or two before the turn of the twentieth century. I picture this woman sitting in a pew, and picking up one of those black jacketed, gilded letters on the spine, double columned bibles, and cracking it open. There she is, wearing a conservative floral printed dress, and some sensible shoes. She’s nudging her spectacles up onto the bridge of her nose, flipping through a ways – there, she’s in Psalms – no, she doesn’t want to read Psalms. Back to Deuteronomy. Deuteronomy? Nope, not Deuteronomy. She opens to Ruth. Ruth! Good choi – oh, no, not Ruth. She opens to Hosea. Hmm. Hosea. A very, very old prophetic book.

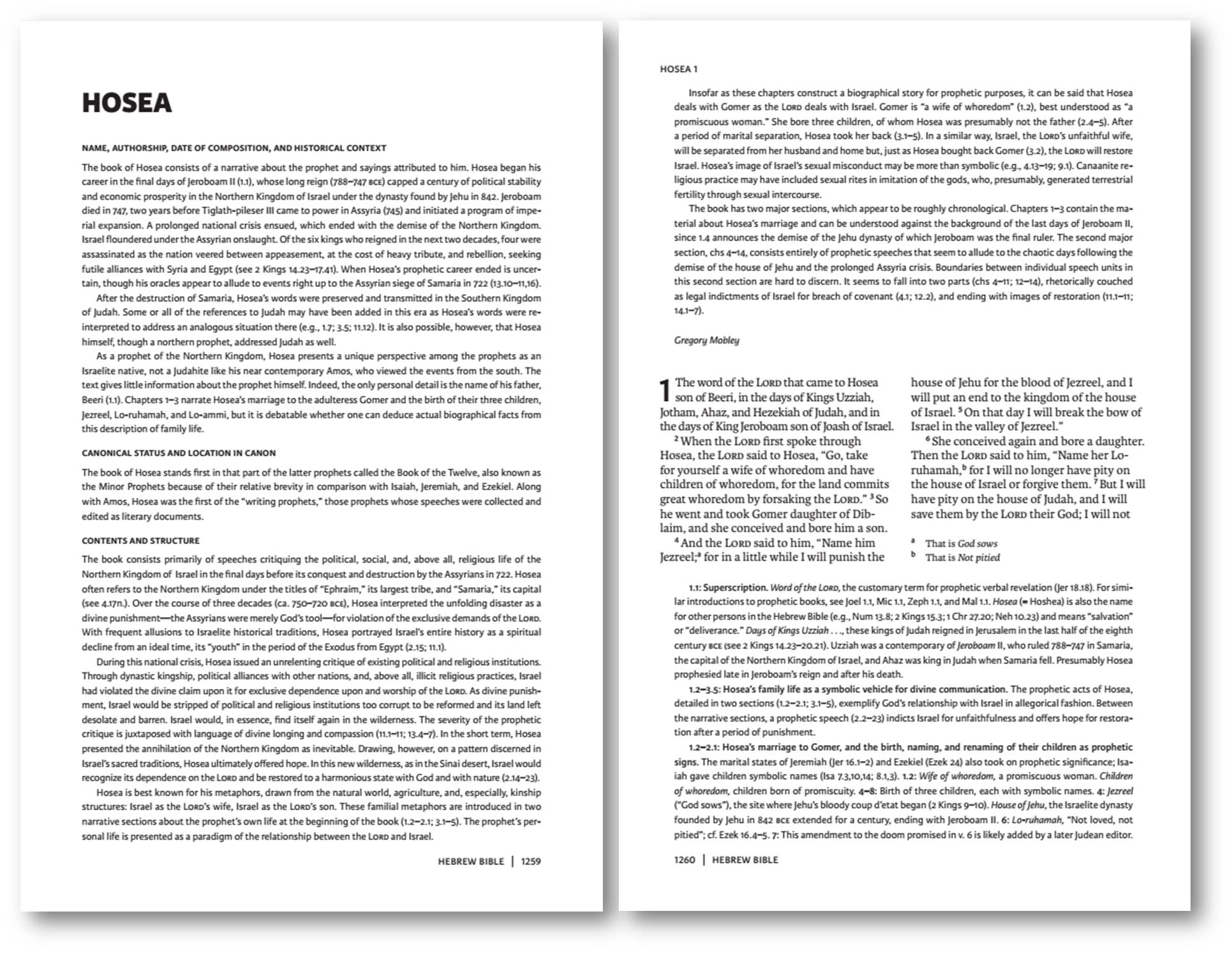

The introductory matter for Hosea and opening verses of this book of the Old Testament, from the New Oxford Annotated Bible, one of the richest, most indispensible and academically robust books ever published. From the time I started reading the Old Testament, this edition, with its maps, historical background, copious notes on translation, was my constant partner.

Still, I put myself in the shoes of this woman in a pew with a Bible a few generations ago, and I think that understanding what’s going on in the Old Testament seems like it would have been really challenging, and in many cases impossible. There are 1,399 chapters in the Old Testament, New Testament, and Apocrypha of the middle-of-the-road Catholic Bible we discussed earlier. These chapters contain, by one count, over 2,600 proper nouns. There aren’t ten commandments in the Pentateuch. There are 613. And there are seventeen prophets, scattered across the history of ancient Israel and Judah, each with his own book, and the Prophetic Books had later redactors working on them and adding to them, too.

So I imagine this woman of my great grandma’s generation opening up something like the Book of Hosea in one of those old minimalist black bibles. How was she supposed to know who Hosea was? In 1905, what did we know about the city of Samaria, where Hosea lived? We hadn’t excavated there, or found the famous ivory plaques, or catalogued the finery of the court of Jeroboam II, a result of this king’s economic ventures with the Neo-Assyrian Empire. If we were of my great grandma’s generation, when we opened to the Book of Hosea, we just saw the single capitalized noun, HOSEA, then, the names of a bunch of kings and then this: “When the LORD first spoke through Hosea, the LORD said to Hosea, ‘Go, take for yourself a wife of whoredom and have children of whoredom, for the land commits great whoredom by forsaking the LORD.’ So he went and took Gomer daughter of Diblaim, and she conceived and bore him a son” (Hos 1.2-3). Wait, what? Slow down. Who’s Hosea? Why did God tell him to marry a whore? What kind of advice is that? And to return to the original question, what did a person of my great grandmother’s generation, unless she had a trained specialist around, take from reading Hosea in, say, about 1905, straight with no chaser?

A single sentence or two in a precursory head note would have sufficed. If the editors just said at the beginning of the Book of Hosea, “Hey there. Hosea lived during the late 700s BC, in the lavish court of the northern kingdom of Israel. The king there at the time was called Jeroboam II. Hosea is angry at the decadence of the northern kingdom of Israel and wants people to turn to a simple, pious life centered on the worship of Yahweh. Got it? 700s, angry minimalist guy in an opulent court. Have fun.” You and I can find this information in five seconds. But someone of my great grandma’s generation wouldn’t have found it – certainly not in her unadorned, black-jacketed Bible.

The Flowering of Biblical Archaeology and Scholarship, 1800-Present

The translation of the Bible into vernacular languages during the Early Modern period was our first step, as laypeople outside of the clergy, in reading it and understanding it for ourselves. But over the past century and a half, other tools have become widely available that make understanding the Bible easier than ever. It was, as it turned out, my great grandmother’s generation, and the two before her who unlocked Biblical archaeology and began to decisively pry open ancient languages – Egyptian hieroglyphs, Akkadian, Ugaritic, Hittite and other languages of the Ancient Near East relevant to the Old Testament. Many of the things that we talked about last time were discovered by her contemporaries, and her parents’ and grandparents’ generations. Flinders Petrie discovered the Merneptah Stele in 1896. The Mesha Stele was found three decades before this, and over the course of the 19th century, other seminal findings from Biblical archaeology were dug up and put in museums that we’ll soon learn more about – the Obelisk of Shalmaneser, the Annals of Tiglath-Pileser, Sennacherib’s Prism, and the Library of Ashurbanipal. We have had the Old Testament’s version of ancient history for thousands of years. Only recently have we had other sides of the story.Since the Rosetta Stone was discovered in 1799 and deciphered by Jean-François Champollion and Thomas Young in the 1820s, we’ve begun to have a much clearer understanding of the dynasties of Ancient Egypt – their religion and culture, their economics and international relations. Soon after, Henry Rawlinson began transcribing the famous Behistun Inscription in the Zagros Mountains of modern-day Iran in the 1830s, and Austen Henry Layard found the library of Ashurbanipal in 1851. It contained 20,000 clay tablets – a snapshot of all of the Mesopotamian literature in circulation during the Iron Age. Six years later, in 1857, four translators working on behalf of the Royal Asiatic Society created similar translations of an Akkadian cuneiform tablet from around 1,100 BCE. The decipherment of ancient languages from Iraq and Iran meant that the texts of ancient Mesopotamia could be read and understood for the first time in millennia. Then, in 1906, the discovery of 10,000 more tablets in Hattusa, the land of the Hittites in modern day Turkey, added hugely to our knowledge of the ancient world. And also at the turn of the century, the discovery and compilation of the Amarna letters, clay tablet correspondence between Egypt’s kings and the regional powers of Mesopotamia, Turkey, and the Levant, began to give us a view of a Late Bronze Age world that was highly specialized, economically stratified, and commercially interlinked, from Sicily to the eastern regions of Iran, up to the mountains of the Balkan peninsula, and as far south as Yemen and the Sudan. The world that existed before Ancient Greece and Rome, once buried beneath sands and lost in dark caches under crumbled cities, started being recovered in the nineteenth century. Ancient Greece and Ancient Israel were no longer the twin darlings of antiquity – as it turned out, they had uncles, aunts, parents, and grandparents, and a lot of them. And the discoveries accelerated and accelerated over my grandparents’ and parents’ generations. In the 1920s, the same decade King Tutankhamun’s tomb was opened, a cache of Ugaritic texts was discovered in modern day Syria, and once deciphered, these late Bronze Age tablets began to reveal extensive parallels with the theology of Ancient Israel.

A century before my great grandma’s generation, it seemed that the Old Testament was the largest, most colorful, reliable source of information about the ancient world we had. If it said that King Solomon had 700 wives and undertook larger than life building projects, then there was little reason to suppose otherwise. If it said that Joshua’s armies marched around Jericho tooting trumpets and Jericho’s walls collapsed, then the trumpets sounded, and the walls fell. But we have many other contemporary and older texts now – the Enuma Elish, Atrahasis, Gilgamesh, the Descent of Ishtar, the poetry of Enheduanna, the Ugaritic Baal cycle, the Hittite Kumarbi cycle, and a whole shelf of writings from Ancient Egypt, from pharaonic inscriptions to short fiction like “The Shipwrecked Sailor” to the novella The Story of Sinuhe to the wacky and pornographic “Contendings of Horus and Set” to the gigantic Book of the Dead. These texts were not widely available a hundred years ago. They are now.

There is something inherently nettling to some of us about drawing textual parallels between the Tanakh, and other Iron Age, and Bronze Age texts. As we explore some of these parallels together over the next bundle of episodes, though, I should note that my intention isn’t to prick or scratch at the colossus that is the Old Testament, which is doing quite fine with its two billion readers, so much as it is to prop up some other texts that are far less well known. To this day, shockingly, to me, there are hardly any editions of the work of Enheduanna, a priestess of Ur in the 2200s BCE and the first named author in the historical record. You might think that this lady would merit a Penguin or Oxford edition, or perhaps even be a household name. Similarly, from the same period, the Descent of Ishtar, sometimes called the Epic of Inanna and Dumuzi to use the deities’ Sumerian names, a long narrative about a courageous deity, her journey to the underworld, her doomed love, and a lot of beer and sex along the way, is only known to specialists and published in one modern edition, while her masculine counterpart Gilgamesh somehow snuck into the world of general literary knowledge. The sacred narratives of the Hittites and of Ugarit, Israel’s neighbors, as important as they are, are still only published in a couple of editions. The oldest Zoroastrian texts, roughly contemporary with, or a little younger than the Old Testament, are not compiled in any modern scholarly edition, although Zoroastrians and Jews were next door neighbors in the Levant and Babylonia for a thousand years. To put it briefly, Israel and Judah, those kingdoms we met last time, were never powerful on an imperial, intercontinental scale over the course of the 1,000 years the Bible was being written, and when we look back into the ancient world, outside of specialist circles, we continue to almost completely ignore their larger cultural milieu. In drawing your attention from time to time to probable lines of influence behind some parts of the Old Testament, then, I hope to call just a bit more attention to other wonderful ancient texts that continue to be stubbornly and unaccountably ignored outside of academic circles.

This is a superb time to read the Old Testament. Archaeology has produced a wealth of raw materials – cuneiform tablets, wooden coffin inscriptions, papyrus fragments, ostraca and stele with writing on them, architectural remnants, pottery and jewelry, bones and mummified remains, burn layers, soil samples, shipwrecks, figurines, plinths and totems, armor and weaponry, chariots, bits, sculptures, etchings, seals, and far more. These materials have been, and continue to be processed and analyzed. In 1993, as the Simpsons entered its fifth season on television, a paving stone was discovered near the Golan Heights, dated roughly to the 800s BCE, that contained the first archaeological record of the name of King David. There is still a lot out there in the ground, and it will tell us more and more about the Ancient Near East. While we can hope that the next few decades will bring us another set of Dead Sea Scrolls or another Nag Hammadi Library, maybe the most important thing that biblical archaeology has taught us is something that can be summed up very simply.

From archaeology and scholarship, we have learned that the Old Testament isn’t really that old. We learned in our podcast’s first episode that half of recorded history had elapsed before the Tanakh’s earliest books started being written. While for some 2,500 years we have been reading the Old Testament, it’s only been over the last 200 of those years that we’ve begun having substantive archaeological information about the ancient world. And of those 200 years, only for a scant century have professionally trained philologists and paleographers, together with the techniques of modern survey archaeology, been put to work in understanding the world of the ancient Israelites. The Old Testament, then, is closer to us, and more approachable, and more human than it’s ever been. And today we’ve learned that as complicated as the Old Testament can sometimes seem, it’s all divisible into four main parts – say it with me if you can – first, the Pentateuch; second, the Historical Books; third, the Wisdom and Poetic Books; and fourth, the Prophetic Books. [music]

Moving on to the Narrative Portions of the Pentateuch

In the next episode, then, we’re finally going to get into it – the first of those four main parts we talked about today, the Pentateuch, or Torat Moshe, or Torah, and the narrative sections that stretch through the Bible’s first five scrolls – Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, and Deuteronomy. In the next episode, we’re going to meet the most famous family in history – specifically, the family of Abraham, his progenitors, and his successors, and we’ll explore the world of the Biblical patriarchs down to Moses’ farewell speech on the banks of the Jordan River. And while we’ll hear the story of the patriarchs of Israel, we’ll also consider some parallels between the Pentateuch and other ancient Mediterranean tales of watery creations, floods, original sins, babies adrift on rivers, and explore whether some of the Hebrew names for God in the Bible might bear traces of a polytheistic past.So thanks for listening to Literature and History. As always I have a quiz on this episode available in the Details section of your podcast app. At literatureandhistory.com, there is the full episode transcription, plus illustrations, and some especially handy inforgraphics about the various canons of the Bible. Got a song coming up if you want to hear it. If not, class dismissed, and I’ll see you next time.

Still listening? I got to thinking about how long the Bible is – I mean, those 915,000 words of the Old Testament, New Testament, and Apocrypha. How many novels, plays, and poems could you squeeze into that length, and which ones? Just how long is 915,000 words? I got to thinking about that, and I wrote the following jazz tune, called “It’s Long.” Hope you like it, and Abraham, Isaac, Jacob and the gang and I are coming your way soon in Episode 17: Roots of the Pentateuch.

References