Episode 17: The Roots of the Pentateuch

The Old Testament, Part 3 of 10. Hear the Biblical story of creation and the first founders of Israel, and the texts that may have influenced this story.

| Read Transcription | References and Notes |

| Episode Quiz | Episode Song |

| Episode on Spotify | Episode on Apple Podcasts |

| Previous Show | Next Show |

The Narrative Portions of the Pentateuch and Ancient Near Eastern Literature

Hello, and welcome to Literature and History. Episode 17: The Roots of the Pentateuch. In this program, we’re going to cover the narrative, or story portion of the first five books of the Old Testament – Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, and Deuteronomy.וְהָאָרֶץ הָיְתָה תֹהוּ וָבֹהוּ וְחֹשֶׁךְ עַל־פְּנֵי תְהֹום וְרוּחַ אֱלֹהִים מְרַחֶפֶת עַל־פְּנֵי הַמָּיִם׃

וַיֹּאמֶר אֱלֹהִים יְהִי אֹור וַיְהִי־אֹור׃

וַיַּרְא אֱלֹהִים אֶת־הָאֹור כִּי־טֹוב וַיַּבְדֵּל אֱלֹהִים בֵּין הָאֹור וּבֵין הַחֹשֶׁךְ׃

וַיִּקְרָא אֱלֹהִים ׀ לָאֹור יֹום וְלַחֹשֶׁךְ קָרָא לָיְלָה וַיְהִי־עֶרֶב וַיְהִי־בֹקֶר יֹום אֶחָד׃ פ

Read by Israel Radvinsky on Librivox.

When we read this book, sometimes, it seems deceptively familiar to us. For thousands of years, we have spun around it like a vortex, fashioning our civilizations in different ways but hurrying back always to its pages and finding slightly different things there. The Bible tells of how God created the world, as you just heard in Biblical Hebrew a moment ago, but we can just as well say that the Bible itself created us. It taught us the rather curious ideas that there was a beginning and that there will be an end, that an extrasensory tier of reality persists somewhere beyond our capacity to understand it, that our deeds and thoughts have moral ramifications, and that life on earth is a matter of some sort of providence, and some has greater consequence than the random flux of everyday experience might otherwise lead us to believe. Such ideas abounded in the Ancient Near Eastern and Mediterranean prior to the Bible, but it was through the Bible that they came to many of us today, and through the Bible that individuals and states and organizations acted on them, creating the cultural and national geography of much of the modern world.

A Samaritan Priest with a Torah Scroll, by Ephraim Moses Lilien (1874-1925) The Pentateuch contains both stories and laws.

One of the most challenging facets of the Bible’s first five books is their organization. The Pentateuch, or Torat Moshe, meaning the books of Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, and Deuteronomy – these books on our desk for today are a mixture of two different sorts of writing. The first is a story – a story that concerns a family lineage that stretches from Adam and Eve at the outset of Genesis down to the descendants of the twelve patriarchs of Israel at the end of Deuteronomy. While the story portion of the Pentateuch veers left or right once in a while to offer you a genealogy list, or becomes distractingly repetitious, it is nonetheless a chronologically ordered narrative, beginning with the moment of creation and ending after many generations of people have lived and many tumultuous events have occurred. That’s the first sort of writing in the Pentateuch – the narrative portion, about the descendants of Adam, and how the lineage of Israel came to be. The other type of writing, mainly present in Exodus, Numbers, Deuteronomy, and especially Leviticus, is what we can call “prescriptive” writing – writing that offers instructions and guidelines on how to live a pious life in the Iron Age city state of Judah. This second type of writing is why the Pentateuch is also called the Torah, Torat Moshe in Hebrew, which means Law of Moses. While the Pentateuch does tell a sweeping story about the roots of Israel, it is also studded nearly from end to end with regulations and directives related to animal sacrifice, cleanliness, community rules, and other laws written by, biblical scholars today assume, temple priests concerned with correct tithing and deportment by their congregations. Both parts of the Pentateuch – the story portion, and the laws portion, in other words – are very important. Today, we will concern ourselves with the narrative portion, beginning with Adam and Eve, and ending with the Israelites about to cross over the Jordan River into Canaan.

In the remainder of this episode, I’m first going to summarize the stories of the Pentateuch. Then, I’m going to talk about some of the literary and religious texts that were circulating around in the Ancient Near East in the Late Bronze and Iron Ages that demonstrate the Pentateuch as part of a greater textual environment, and in some cases, though we’ll never know for certain, might have influenced the Pentateuch. We’ll begin the journey with a book that needs no introduction. At 50 chapters, Genesis is the fifth longest book in the Bible by chapter count, behind Psalms, Isaiah, Jeremiah, and Sirach. But while no one remembers all the Psalms, or the visions of the prophets, and many bibles don’t even include Sirach, Genesis, from end to end, is a book that everyone should go through at least once. Unless otherwise noted, quotes from the Pentateuch in this episode will be out of the NRSV translation, from the New Oxford Annotated Bible, published by Oxford University Press in 2010. [music]

The Pentateuch, Book 1: Genesis

Creation, Transgression, and Exile

The Old Testament creation story begins like many other Ancient Near Eastern creation stories – with darkness, and water.In the beginning when God created the heavens and the earth, the earth was a formless void and darkness covered the face of the deep, while a wind from God swept over the face of the waters. Then God said, “Let there be light”; and there was light. And God saw that the light was good; and God separated the light from the darkness. (Gen 1:1-4)1

In due time, night and day came to be, then the sky and earth, plants, the sun and moon, and moving creatures. And the chief among them would be humankind. Pondering the creation of humanity, God said, “Let us make humankind in our own image, according to our likeness” (Gen 1:26), and so, all in a moment, “God created humankind in his image, in the image of God he created them; male and female he created them” (Gen 1:27). God promised them dominion over all living things, and was pleased with everything he’d made.

Later, because rains were flooding the fallow fields, God realized someone was needed to till them, and he created man from the dust of the ground, this time by breathing into his nostrils. (There’s a double creation of humankind in Genesis, by the way – one that takes place in Chapter 1, and a second more detailed creation in Chapter 2.) So this second man was given a garden called Eden, a land of four rivers, the Pishon, the Gihon, the Tigris, and the Euphrates. God set this second man down into the garden and told him to eat whatever he wanted there, except for the fruit of one tree. God said, “You may freely eat of every tree of the garden, but of the tree of the knowledge of good and evil you shall not eat, for in the day that you eat of it you shall die” (Gen 2:16-17).

With this first – or second man safely situated in Eden, and having given this man crucial instructions about the Tree of Knowledge, God decided that the man ought to have a companion, and so he created a woman. God had the man fall asleep and using one of the man’s ribs to create her. So there they were, the man, and the woman, in the Garden of Eden, naked, unashamed, and within arm’s reach of plenty of food. You know, for the first two of the Bible’s total of one 1,399 chapters, things were going fairly well. But, I suspect you know the next part of the story.

A serpent – just a serpent, keep that in mind – Satan makes no appearances in the Old Testament – a serpent came to the woman, and, in spite of her apprehension, the serpent promised her that “when you eat of [the forbidden fruit] your eyes will be opened, and you will be like God, knowing good and evil” (Gen 3:5). So the curious woman took a bite, then her husband did so, too, and abruptly they felt the need to cover their private parts with fig leaves. Their shame at their nakedness tipped God off, and then, the punishments began.

First, the talking snake was cursed to crawl on his belly. The woman was cursed to suffer pain in childbirth, to desire her husband, and to be ruled over by him. The man was cursed to work, sweat, and toil in the fields, and cursed to return to the dust from whence he had came. God made them clothing, and announced that they were henceforth exiled from Eden. The couple were chased out of the garden by God, and a flaming sword was put up east of the garden to prevent them from reentering. [music]

From Cain and Abel to Abraham

Now exiled from Eden, the inaugural couple had a baby. The man named his wife Eve. The name Eve that we use today comes from the Latin name Eva, which itself came from her actual Hebrew name חַוָּה, meaning “to breathe” or “living.” The man, whose name we later learn is Adam, and his wife Eve’s first baby was named Cain. Soon another boy – this one called Abel – was born to the first couple. Cain liked to grow vegetables and fruits. Abel was a shepherd, and he kept flocks. One day, the two young men offered sacrifices to God. Cain offered fruits and vegetables. Abel offered meat. God wanted the meat. In general, the gods and holy men of the Ancient Near East really, really liked meat, as we’ll see over the next few episodes.Having his fresh produce spurned by God did not sit well with poor Cain. He’d worked quite hard to grow those fruits and vegetables. So Cain, out of jealousy killed his brother Abel. As a punishment for fratricide, God told Cain that Cain would be forever cursed to wander the earth. Cain went to the Land of Nod, where he found a wife. The fact that Cain goes to the Land of Nod in Genesis, Chapter 4, Verse 16, and finds a wife is a famously strange part of the Book of Genesis. We have been told by the narrative so far that Cain’s parents were the first people, and that they had just the two sons so far – and the Book of Genesis then tells us that some sort of secondary civilization was out there waiting for Cain. That isn’t very narratively coherent, and biblical scholars today assume that the creation story, the Cain and Abel story, and Cain’s finding a wife in the Land of Nod were all separate tales that were combined together at one point.

So, however exactly it happened, Cain married, and he had a son named Enoch, and founded a settlement called Enoch, which was soon home to Cain’s many descendants. Meanwhile, the original couple, Eve, and her husband Adam, now both aged a hundred and thirty years, had another boy. His name was Seth. Seth’s son was called Enosh, whose son was Kenan, and then Mahalalel, and then Jared, Enoch, Methuselah, Lamech, and then Noah. Of all these men, Enoch had the shortest lifespan, living a paltry 365 years. The others lived into their eight hundreds and nine hundreds. It was an extraordinary time – people not only had fantastically long life spans, but they also interbred with a race of giants called the Nephilim. The Nephilim copulated with human females, creating “the heroes that were of old, warriors of renown” (Gen 6:4). And this, by the way, is an intriguing little grotto of the Book of Genesis, and later, during the second century BCE, a genre of Jewish apocryphal literature called the Enochian corpus was born, which concerned a race of semidivine giants that lived on the earth while it was still young.2

As more generations came of age, and perhaps due to disquietude about the scions of the Nephilim stalking around the earth, God resolved that men would no longer live as long as they had. A hundred and twenty years, God resolved, was quite long enough. But merely making humans live shorter lives was not enough chastisement for what God saw happening in the world that he had created. As Genesis tells us, “The LORD saw that the wickedness of humankind was great in the earth, and that every inclination of the thoughts of their hearts was only evil continually” (Gen 6:5). Convinced that the whole earth had very quickly turned foul, God decided to take drastic measures.

God told Noah, the great great great great great great great great grandson of Adam, to build a giant boat, fill it with the world’s species, and be ready for some heavy rain. After just nine generations of humankind, then, God planned the first apocalypse written of in the Bible. We discussed the Biblical Flood in a lot of detail in our program on the Atrahasis epic, so let’s move on. Following the Biblical Flood, Noah offered God some sacrifices. God caught scent of the meaty odors, and summarily resolved that he wouldn’t again flood the planet. God issued some preliminary rules for Noah, and then said he wouldn’t forget this covenant. There are many moments to come in the Old Testament during which an enraged God ravages the Israelites or their progenitors, and then, after a period of strife, a new concord or covenant is established. This is the first of those scenes. Later Pharisee scribes, during the second century BCE, paid special attention to this moment in an apocryphal book called Jubilees – this moment in which what’s called Noahide Law is established.3 It was a surprisingly significant moment, this cusp between Chapters 8 and 9 of Genesis, to later scribes interested in Biblical Law, because after God floods the earth, he becomes friendly once more toward Noah and issues the first lengthy set of directives in the whole Bible.

To return to the narrative of Genesis, as for Noah, patriarch of the ninth generation of mankind – Noah had three sons – Shem, Ham, and Japheth. The three of them repopulated the earth. Due to an awkward incident in which Ham saw his father drunk and naked, Ham and his son Canaan were cursed to be the slaves of his brothers Shem and Japheth. Then proceeds the infamous tenth chapter of Genesis, a list of the descendants of Noah. Generally, these descendants are associated with geographical locations in Egypt, Mesopotamia, and Asia Minor, and the story of Noah’s descendants is shorthand for the dissemination of civilizations in the Ancient Near East that were familiar to the authors of the Book of Genesis. In the middle of the genealogy of Noah’s descendants, the narrative pauses to tell the story of the Tower of Babel – how it threatened God, and how God destroyed it and created a plurality of languages instead of a single one. And in Episode 1 of this podcast, we spent ninety minutes considering this strange story, and whether it might be an allegory for the end of Akkadian Cuneiform following the rise of the Achaemenid Persian Empire over the course of the sixth century BCE.

More genealogical narrative proceeds in the eleventh chapter of Genesis, offering us the names of patriarchs, their oldest sons, and their lifespans. From time to time, you will meet people who talk about all of the “begats” in the Book of Genesis, and how tedious this part of the Bible is. Chapters 10-11 of Genesis offer the biggest concentration of “begats.” For such a notoriously dense section of the Bible, though, the “begats” portion of Genesis is really only a few pages. And it’s actually more interesting to read than many of us think, because if you know a little about the geography of ancient Canaan and its neighbors, you can see that this dry genealogical narrative is a decent little origin story for the power relations of the Late Bronze and early Iron Ages in and around modern-day Israel. In the antiquity, in ancient Greece and Rome as well as the Ancient Near East, people were absolutely smitten with something called etiology – or investigating the origins of, say, a civilization, or a cultural practice, and a huge amount of Ancient Mediterranean narratives are about how this or that came to be. Genesis contains a great many etiologies – we’ve so far learned about why we have to work, why women have to bear children, and why our lives are shorter than they might otherwise be, and the “begats” portion, or genealogical narrative that follows the Biblical Flood in Genesis similarly offers origin stories for the many neighbors of Judah around the exilic period.

Anyway, the genealogical chapters of Genesis culminate in a descendant of Noah’s son Shem, a descendant called Terah. Terah was terribly important, because Terah was the father of Abraham. And Abraham is the most important person in the Old Testament. [music]

Abraham and the Cities on the Plain

Abraham’s name, initially, is Abram. But I’m just going to call him Abraham. Abraham, according to the narrative, was born in the Sumerian city of Ur. This city had risen in prominence at the end of the 2,000s BCE, and would have been remembered, in later centuries, like those which produced the Bible, as an especially ancient and storied part of Mesopotamian history. Abraham, his wife Sarah (or Sarai, as she’s called at first) and his nephew Lot left the city of Ur. After a journey to Canaan, and then Egypt, Abraham returned to Canaan. His brother had settled on the plain east of the Jordan, and Abraham himself, now well off, settled permanently in Canaan, the beautiful, ecologically diverse land we talked so much about a couple of episodes ago. One day, as Abraham gazed around Canaan, God told him, “Raise your eyes now, and look from the place where you are, northward and southward and eastward and westward; for all the land that you see I will give to you and to your offspring forever” (Gen 13:14-15). This promise, which is frequently repeated by God to Abraham and his more significant descendants, is one of the main themes of the Old Testament. The notion that Canaan was the destined homeland of Abraham’s descendants, according to divine mandate, is one of the core tenets of the Old Testament, and of course, a very important idea in the history of Jewish culture.

The Geneaology of Abraham. Much of the narrative portion of Genesis, and the rest of the Pentateuch is dedicated to explaining the story of this family, down to Joseph. Graphic by Drnhawkins.

More dramatic events unfolded in Abraham’s life after this. Abraham’s supposedly infertile wife conceived a son. Then, Abraham learned that God planned the wholesale destruction of cities out to the east, on the other side of the Jordan. What happened next happens again and again and again in the Old Testament. It happens as often as God guarantees the Promised Land to the Israelites. God got angry. Abraham pleaded with God to spare people and not vent too much wrath on them, and God relented. That’s again a main plot structure throughout the Old Testament. Somebody screws up. God gets ready for some wholesale slaughter. Then someone begs God’s mercy. And God relents. This incident takes place dozens of times in the Hebrew Bible.

So, in this specific case, the first intercession story, if you will, Abraham tried to keep God from killing absolutely everyone in the cities Sodom and Gomorrah. After throwing many numbers out there, Abraham asked whether God would spare the wicked cities of Sodom and Gomorrah if just ten righteous people could be found there. God said he would. After this, two angels went to Sodom, and sought shelter in the house of Lot. Chapter 19 of Genesis – the story of Sodom, Lot, and Lot’s daughters, is a dark tale, filled with violence, wickedness, drunkenness, incestuous sex, and the overt threat of homosexual rape. In it, God’s angels went to Sodom and sheltered with Lot. The citizens of Sodom wanted to have sex with the newcomers. Lot offered the randy citizens of Sodom his daughters, instead. Eventually, the angels, in self-defense, blinded the men who had come for them. The cities of Sodom and Gomorrah were destroyed, as not even ten righteous people had been found there, after all. Lot and his wife and their two daughters escaped to safety, though Lot’s wife, looking backward, turned into a pillar of salt. Afterward, Lot impregnated his daughters in a cave. The children of these ignominious and incestuous unions would go on to be the progenitors of the nations of Amon and Moab, states that would be Judah’s sometime foes when most of the Old Testament was being set down.

So the crisis in Sodom and Gomorrah, the Cities on the Plain, was taken care of. Back on the other side of the Jordan River, God decided to test Abraham. Abraham’s wife Sarah had given birth to a boy Isaac. God asked Abraham to kill the boy. Abraham was willing to kill his son, and he ascended Mount Moriah to do so in one of the Bible’s more famous and dramatic narratives. But in the nick of time, God stopped the murder, being satisfied with Abraham’s unquestioning loyalty. In due time, young Isaac was grown enough to be married, and wed a woman named Rebekah. And Isaac had two sons. One of them was red and hairy. His name was Esau, and he was the oldest. The other was more normal looking. His name was Jacob, and he was the youngest. And like so many figures in Genesis, Jacob is preposterously important. [music]

Jacob and the Struggle with God

First and foremost, Jacob was clever. Through trickery and the help of his mother, he was able to secure the rights of the firstborn son from his hairy brother. Esau was not happy about this, and, at his mother’s behest, Jacob fled to the land of his uncle Laban. There, he served Laban for seven years, and had sex with every female in the house. Jacob slept with Leah, Laban’s older daughter. He slept with the maids, and got everybody pregnant. Then he married the youngest daughter, Rachel, who was barren. With his new bride and crop of semi-legitimate children, Jacob left the land of Laban, pursued by his angry uncle slash father-in-law slash master, later managing to smooth things over.

Alexander Louis Leloir’s Jacob Wrestling with the Angel (1865). This incident in the Pentateuch is the one from which Israel gets its name.

Jacob’s story would continue to be one of struggling. He met his brother Esau again, and again treated the man very, very cautiously. Once Jacob had grown older, and sired more and more children, a man named Shechem raped one of Jacob’s daughters. Jacob forced the man to pay a very high dowry and marry his daughter – that was the law, but even after Shechem and his people were circumcised, and made part of Jacob’s religion, they seemed to just want to take the Israelites’ property. In retaliation, two of Jacob’s sons snuck into the city of Shechem, murdered all the males, and stole all the valuables, enslaving their virginal women and children. Jacob’s two sons assured him that the killing and enslavement had all been done for the sake of honor.

Jacob, or Israel, as he was now called by this point, had many sons, and was quite clever and successful in his work as a herdsman and trader. He migrated to a place called Bethel and set up a sacrificial altar there. His father Isaac died, and then his wife died in childbirth. And at this point, the narrative begins to concern itself with the twelve sons of Jacob, or Israel, who would go on to become the twelve tribes of Israel. [music]

The Story of Joseph and His Brothers

Let’s have a quick review, and get a sense of the timeframe that’s elapsed so far in Genesis. We’ll start by getting three names in our heads – Adam, Noah, and Abraham. Adam was the first person. Noah was the ninth-generation male offspring from Adam, and Noah survived the flood. And Abraham was born ten generations after Noah, and thus nineteen after Adam. Abraham is the patriarch of the nation of the nation of Israel, the central subject of the entire two thousand pages of the Old Testament. Abraham – his journeys and his covenant with God – is where it all really begins. Abraham is the beginning of Israel. We get the name Israel from Abraham’s grandson, Jacob, who strove or struggled with God, which is what Israel means. So, again, Adam, then nine generations, then Noah and flood, then ten generations, then Abraham, his son, and his super-important grandson Jacob, whom I will call Israel from here on out, because the Old Testament begins to. Adam, Noah, Abraham, Israel. Twenty-one generations into humankind, and then, Israel, the one who struggled with God. Also, the one who struggled with a number of women in bed.Israel had multiple wives, and multiple concubines. The lot of them together produced twelve sons. These were Rueben, Simeon, Levi, Judah, Issachar, Zebulon, Gad, Asher, Dan, Naphtali, Joseph, and Benjamin. A few of these kids are going to be really important for different reasons. We’ll start with Joseph.

Joseph was one of Israel’s younger sons. Joseph and his father Israel signify a general change in the first twenty-two generations of humankind. At first, mere piety is sought by God. Israel’s grandfather Abraham’s most important moment is the test of his willingness to kill his son in order to please God. But with the coming of Abraham’s grandson Israel, and Israel’s son, Joseph, ingenuity, trickery, and innovation are the favored characteristics of the central figures of the story of the patriarchs. Israel tricks his brother out of his birthright. He contrives to not just marry his uncle’s youngest daughter, but both of the man’s daughters, and to use their maids as concubines. Israel is an expert breeder of livestock and his innovations make him wealthy. And if Israel is smart, a sort of trickster folk hero who’s wily enough to wrestle with God himself, then Israel’s son, Joseph, is the apple that fell closest to the trickster tree.

Joseph was his father Israel’s favorite of all of the twelve sons – clever, ambitious, and in his own way, merciless. All of the other boys knew it. Joseph had a dream that he would one day dominate all of his brothers. When he told them about this dream, they were understandably disconcerted. They considered killing him. Instead, they sold Joseph into slavery. Subsequently, Joseph wound up a slave in Egypt.

Ever associated with his ability to understand dreams, Joseph managed to become dream interpreter to the Egyptian Pharaoh. Years passed, and Joseph proved ever more useful to his king. Joseph’s intelligence and his connections also helped him become commercially and socially successful in the lands of Egypt. A dream told Joseph that the earth would face seven years of famine. Subsequently, Joseph’s careful stockpiling of grain saved Egypt from a terrible food shortage. As the entire ancient world reeled from famine, some of Joseph’s brothers were sent down south to Egypt to seek the stockpile of grain in the Nile. Joseph did not immediately reveal his identity to his brothers, who had some time ago sold him into slavery. In fact, Joseph demanded to see his youngest brother Benjamin, about whom he’d worried for a long time. The older brothers brought Benjamin to Joseph, and after an extensive delay, Joseph revealed his identity to his long-estranged siblings, telling them that he did not fault them for selling him into slavery. It had all been God’s plan to send him to Egypt, so that he could stockpile food.

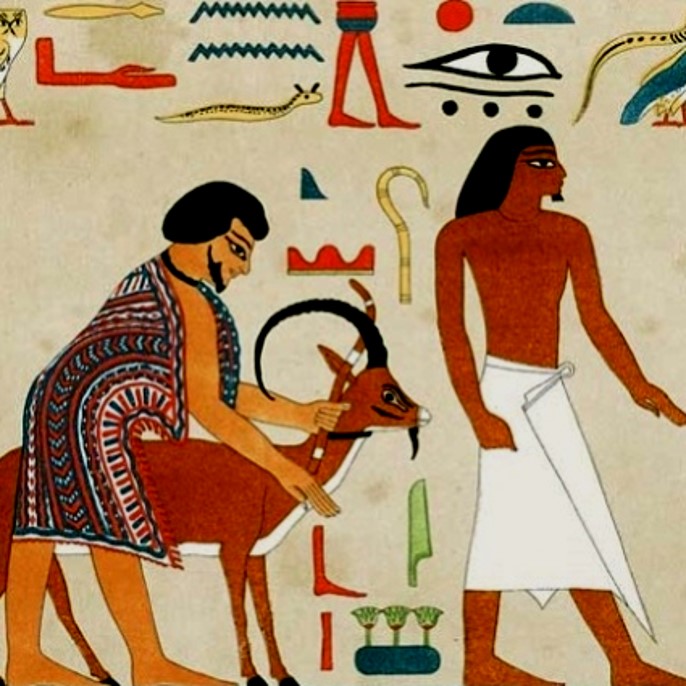

The Chastity of Jacob by Jose de Antonio del Castillo (1616-1668). The folktale that the Pentateuch borrows of a chaste young man refusing a married woman’s advances can be found in the Ancient Egyptian story of Anubis and Bata in “The Two Brothers,” the Hittite language fragment of Asherah trying to seduce Baal, the Greek myth of Anteia, Proteus and Bellerophon, and the more famous Greek myth of Phaedra, Hippolytus and Theseus.

Israel, the father of the twelve tribes, was by this point getting old. He requested to be buried in his ancestral land of Canaan. And on his deathbed, old Israel gave his sons a lengthy speech, criticizing some of them, and giving others his blessing. When Israel died, Israel’s youngest son Joseph wept deeply. Israel was embalmed in the Egyptian style. Joseph asked permission to go bury Israel in his ancestral home. A great retinue escorted the fallen patriarch across the desert to the northeast, where he was interred in the soil of his homeland.

When Joseph returned to Egypt, his older brothers watched with anxiety. Their father being dead changed everything. Joseph would remember, they thought, their misdeeds in the past. They made up a story that Israel, on his deathbed, had asked that Joseph would forgive them for their misdeeds. But as before, Joseph showed circumspection and forgiveness to his brothers. He told his brothers “Do not be afraid. . .Am I in the place of God? Even though you intended to do harm to me, God intended it for good, in order to preserve a numerous people, as he is doing today. So have no fear; I myself will provide for you and your little ones” (Gen 50:19-21).

Then, after living 110 years, and seeing the birth of his great-grandchildren, Joseph bid his brothers goodbye, requesting that he be buried in Canaan like his father, Israel. The Book of Genesis breaks off at the twenty-second generation of mankind, the most central figures of whom are Joseph and his brothers, the twelve tribes of Israel. One of these tribes was the tribe of Levi, the patriarch of the priests, or Levites, of Israel, for whom the Book of Leviticus is named. While Joseph emerged as the key figure in getting the Israelites down to Egypt to help them weather a great famine, it would be a descendant of the tribe of Levi who’d get them back up to Canaan. [music]

The Pentateuch, Book 2: Exodus

The Coming of Moses and the Exit from Egypt

The name exodus comes from the Greek έξοδο Αίγυπτο, or “exit from Egypt.” Over the years that led up to the patriarchs of the Twelve Tribes, the Israelites, descendants of Israel, and before him Isaac and Abraham, had generally prospered. Their population had grown steadily. But a power transition in the mighty empire of Egypt brought down their fortunes. A new Pharaoh came to power who mistrusted the success of the Israelites. They were not Egyptians, after all, but foreigners who had settled in the Delta. Soon thereafter, as the first chapter of Exodus tells us, “The Egyptians became ruthless in imposing tasks on the Israelites, and made their lives bitter with hard service in mortar and brick and in every kind of field labor. They were ruthless in all the tasks that they imposed on them” (Ex 1:13-14). Even these oppressive acts were not enough.The Pharaoh began demanding that midwives kill the male babies of the Israelites – that they drown these unfortunate boys in the Nile. One Israelite mother – a woman of the tribe of Levi – would not see her defenseless baby massacred. At a loss for anything else to do, this woman made a papyrus basket, plastering it over with bitumen and pitch. The Nile bore the baby northward, and the baby was found by the Pharaoh’s daughter as she bathed in the Nile. He was given an Egyptian name, Moses. But his interests, as a young man and long after, were with the nation of Israel.

Moses quickly showed concern with the way his fellow Israelites were treated. Exodus tells very concisely of a defining experience that Moses had during his young adulthood. The book tells us that “One day, after Moses had grown up, he went out to his people and saw their forced labor. He saw an Egyptian beating a Hebrew, one of his kinsfolk. He looked this way and that, and seeing no one, he killed the Egyptian and hid him in the sand” (Ex 2: 11-13 86). Unfortunately, the Pharaoh found out about this murder, and Moses had to flee. He fled far to the northeast, to a land called Midian, where he found a wife, and had a son.

Meanwhile, for the average Israelite in Egypt, things were bad indeed. So great were the tribulations of the Israelites that God heard about them. As brave Moses tended to his flock in the land of Midian, he saw an amazing spectacle in a field. Exodus tells us that “There the angel of the LORD appeared to [Moses] in a flame of fire out of a bush; he looked, and the bush was blazing, yet it was not consumed” (Ex 3:2). Then Moses spoke with God. God said he’d heard of the Israelites’ miseries, and that “I have come down to deliver them from the Egyptians, and to bring them up out of that land to a good and broad land, a land flowing with milk and honey, to the country of the Canaanites” (Ex 3.8). And then, God told Moses his name – YHWH, or Yahweh, which means “I AM WHO I AM,” or “I AM WHAT I AM” or “I WILL BE WHAT I WILL BE.” God has a number of different names in the Pentateuch – we’ll discuss these later in this and the subsequent episodes.

Suffice it to say that God revealing his name to Moses, and appearing as fire in a bush, and promising to get the Israelites out of Egypt all meant that Moses was a pretty special person. Moses humbly wondered whether his people would believe that he was acting on God’s behalf. To convince Moses, God performed some miracles. He changed Moses’ staff into a snake, and then back to a staff. God made Moses’ hand bear the marks of leprosy, and then returned it to normal. God said that if Moses needed such miraculous evidence of his divine guidance, these miracles would be available to him when the time came. Moses’ anxieties persisted, though. God had to assure him that Moses would be able to turn the Nile to blood. Moses worried that he wouldn’t be a good public speaker, and so God said Moses’ brother Aaron would accompany him from Midian back to Egypt. On a side note, these personal details about Moses create one of the Old Testament’s more three-dimensional characters. The castaway child grew up downtrodden in Egypt and, confronted suddenly with divine favor and responsibility, Moses shies away from it, perhaps still feeling keenly conscious of his humble origins. Inasmuch as Exodus draws a pretty rich portrait of Moses, the next part of the Exodus narrative – the one concerning Moses and the Egyptian Pharaoh, is a bit bumpier.

In Exodus, Chapter 4, God disclosed a rather strange plan to Moses. God would require Moses to go to the court of the Pharaoh, and show the Pharaoh the divine miracles – the snake staff, the leper hand, and the bloody Nile. But God would also force the Pharaoh not to be convinced by any of these divine miracles. God resolved “I will harden his heart” (Ex 4.21). After forcing the Pharaoh not to be convinced by Moses’ miracles, God said, God would murder the firstborn sons of Egypt. Not exactly a fair plan from the perspective of the Pharaoh or the innocent children of Egypt, but, that was the plan that God disclosed to Moses. Moses, then, headed down to the land of the Nile.

On the way to Egypt, a frightening incident occurred. God almost killed Moses for not having circumcised his son, but fortunately, Moses’ wife performed the emergency surgery in the nick of time and saved her husband from certain death. So thereafter, with his son’s penis acceptably circumcised, and his God justly placated, Moses finished his journey down to Egypt. He and his brother Aaron rallied the Israelites, and they asked the Pharaoh for an allotment of time – time to go and celebrate a religious festival in the wilderness. The Pharaoh was not convinced, and he accused the Israelites of merely being lazy.

The Old Testament god kills the firstborn children of the Egyptians in the final “plague,” in one of the more grim moments of the Pentateuch. From the book Figures de la Bible (1728), illustrated by Gerard Hoet.

Then came the tenth plague. God told Moses and Aaron to carve up lambs and splash their blood on the doorposts and above the door of all the Israelites’ houses. God said he was going to butcher all of Egypt’s firstborn children, and didn’t want to accidently kill any of the firstborn children of the Israelites. These preparations made, God killed the firstborn of all the Egyptians, from the son of the Pharaoh himself to the firstborn sons in Egypt’s prisons, and even the firstborn of the livestock. Following this climax in the bloodletting, God allowed the Pharaoh to be convinced of his primacy. And this narrative in Exodus, as many of you know, is the root of the Jewish holiday of Passover, as God passed safely over the marked doors of the Israelites living in Egypt at that time.

By this point, the Egyptians were weakened and demoralized. The Israelites stole openly from them. Six hundred thousand Israelites convened and they prepared to make the journey from Egypt back to Canaan, and their great journey home, or exit from Egypt, or exodus, began. God showed them where to go, the Book of Exodus explaining that “The LORD went in front of them in a pillar of cloud by day, to lead them along the way, and in a pillar of fire by night, to give them light, so that they might travel by day and by night” (13.21).

Sadly for the Egyptians, God was not done playing mind games with the Pharaoh. God forced the Pharaoh to pursue the Israelites. God told Moses, “I will harden Pharaoh’s heart, and he will pursue [the Israelites], so that I will gain glory for myself over Pharaoh and all his army, [against]. . .all the gods of Egypt” (14:4; 12:12). The Israelites fled to the east, the waters of the Red Sea parted to allow their crossing, and the pursuing Egyptian army was drowned in its entirety. After a victory celebration on the eastern shore, the Israelites continued their journey. [music]

The Israelites Wander to Sinai

Two and a half months passed on the Sinai Peninsula. When the Israelites became hungry, God made it rain, telling them to gather up a specific portion, plus double the day before the Sabbath, so that they would have plenty to eat on the holy day. As time passed, Moses had become the leader of the Israelites, and settled all their disputes and court cases. Some of Moses’ extended family recommended that he delegate at least some of his minor responsibilities.

Rembrandt’s Moses with the Ten Commandments (1659). As we discuss in the next episode, even in Exodus (not to mention the rest of the Pentateuch) there are far more than just ten commandments.

After promulgating the Ten Commandments, along with dozens of other rules, Moses had hammered out some of the details of the covenant with Yahweh. God, in turn, told Moses that an angel would be sent to guide the Israelites to the Promised Land. It was important, God explained, that they kill absolutely everyone in the Promised Land. Otherwise, the Israelites might be led astray by false religions. All these instructions were set down in stone and given to Moses. He built twelve pillars for all of the twelve tribes, sacrificed many oxen, and sprayed blood all over the pillars. He then listened to six chapters of explanations of how to build God’s holy tabernacle, where the sacred tablets would be stored, along with explanations on how to slaughter animals in front of the tent, splash their blood on altars and burn their organs correctly, and so on. More legalistic instructions, and we’ll cover them in the next episode. Let me just say that the tabernacle, if you haven’t heard of it, was Israel’s holy tent, where the Ten Commandments were kept, and so the precision of its assembly was naturally of high importance to the authors of the Tanakh.

After Moses listened to the nitty gritty of God’s instructions, he came down the mountain and saw something that upset him greatly. The Israelites, anxious that their leader was absent on such a long conference with God, had convinced Aaron to build a golden calf. Moses was not happy. He broke the golden calf. He broke the tablets. He told some priests to kill each other, and three thousand died in this way. God, seeing the idolatry and pandemonium, hurled a plague at the Israelites. But fortunately, this was not the end of the fledgling nation.

Moses met with God in an isolated spot and begged God to have mercy on the Israelites. This would be Moses’ main role, for the rest of his life. If you looked at his resume, you’d see a long list of bullet points. You’d see “1476 BCE Mount Sinai – stopped God from killing everyone.” “1475, wilderness of Sinai – interceded on behalf of my people and convinced God not to kill us all.” “1475, again, wilderness of Sinai – convinced God not to kill us all.” “1474, persuaded God not to kill us all.” “1472, quote marks.” “1471, quote marks.” Israel’s transgressions, and Moses’ intercessions, are the story that is repeated throughout most of the rest of the Pentateuch. The golden calf is simply the inaugural instance in a long line of similar episodes.

So following his private conference with God, Moses went up onto Mount Sinai for forty days and forty nights, got everything reinscribed in new tablets, and he apologized, asking God not to abandon them. He said, “O Lord, I pray, let the Lord go with us. Although this is a stiff-necked people, pardon our iniquity and our sin, and take us for your inheritance” (Ex 34:9). God accepted this apology, and, after the Israelites heard God’s instructions, they gave Moses the building materials necessary for the Tabernacle’s construction. The Tabernacle was built, the Covenant tablets were stored safely inside, and God, whose cloud hung over the holy tent, after some early hiccups, had a dwelling place with the Israelites. [music]

The Pentateuch, Book 3: Leviticus

Leviticus. Leviticus, Leviticus, Leviticus. When you read the Bible for the first time, you can push your way through the genealogical sections of Genesis. You can force yourself by sheer will to read the huge, granular account of the way that the Tabernacle is to be built in Exodus. But Leviticus, being a massive index of laws from an Iron Age city state, is quite a dense read.Other than Moses’ nephews being slaughtered by God for lighting incense at the wrong time in the holy tent, nothing really happens in the Book of Leviticus. Because Leviticus is all about lighting the incense at the right time. It is, again, a massive, ancient catalog of laws on ritual sacrifice, cleanliness, and atonement for sin. It says that male homosexuals should be executed. It also says that we should splatter the blood of pigeons and turtledoves on altars, burn prostitutes alive, kill wizards, avoid church for a week after ejaculating or menstruating, eat grasshoppers, not get tattoos, and make sure our sacrificial bulls, lambs, rams, and female goats are all spotless before squirting their blood all over the Tabernacle altar. Personally speaking, I always kill wizards when I see them, but the rest of those regulations seem pretty outdated.

On the general subject of Leviticus, let me just say this. In the New Testament, John 3:16 is the succinct maxim, “For God so loved the world that he gave his one and only Son, that whoever believes in him shall not perish but have eternal life.” Well, whether or not you’re a Christian, it’s quite a nice sounding verse. And now let’s hear Leviticus 3:16. “All fat is the LORD’s.” Again. “All fat is the LORD’s.” Save your – uh fat for God. Leviticus 3:16.

Let’s leave Leviticus until a bit later. We’ll spend a bit of time in the world of blood, fat, boils, and bodily fluids in the next episode on the 613 Commandments. Let’s continue on with the story of the Israelites, whom we left just having finished that Tabernacle in the hinterlands of the Sinai Peninsula. [music]

The Pentateuch, Book 4: Numbers

The Intercession Stories of Numbers

The sprawling 36 chapters of Numbers tell the story of Israel’s journey from the southern Sinai Peninsula into the outreaches of Canaan, specifically, the land of Midian or Moab. It is a dangerous, violent journey, filled with internal dissension, ceaseless outbreaks of sacrilege, divine punishment, and the threat of foreigners. And it begins where Exodus left off.With a Tabernacle, a devoted priestly class called the Levites, and a nascent leadership system headed by Moses, the Israelites had the beginning of a nation. And like many nations, they decided to take a census, discovering that there were exactly 603,530 of them out there wandering around and subsisting mainly on heavenly manna. Ten chapters of Numbers are more of the same legalistic substance of Leviticus, until we get once again to the story of Moses and his followers.

There is a central pattern in the Book of Numbers, an event that happens nine different times, with variations, and takes up most of the book. It’s an even I’ve already described before, typified by the golden calf episode. The Israelites do something impious. Then, God prepares to kill everyone. Moses intercedes, and God’s wrath is blunted. Yet in spite of Moses’ timely intercessions, many Israelites still suffer terribly over the course of these stories. They suffer, over the course of the Book of Numbers, from plagues, banishments, military defeats, poisonous snakes, and various other forms of grisly death. But in the main, Moses’ intercessions keep the bulk of the Israelites alive, and keep them chugging along, crisis after crisis, to Midian, just to the southeast of Canaan, the Promised Land.

The sins of the Israelites throughout the Book of Numbers follow a general pattern – in some way or another, they doubt God’s power, or question his elected officials. They complained about the variety of meat and food, and later griped about a lack of water. They worried openly about the dangerousness of the lands into which God was leading them. They questioned the eligibility of Moses and Aaron as leaders multiple times. They defected to foreign lands, and had sex with foreign women. Thousands of them died for these transgressions, victims of God’s various punishments. For the brio of their narration and the historical value of their descriptions, the sin and penalty episodes at the core of the Book of Numbers deserve to be read in great detail. But because they are a repetition of essentially the same event, chapter after chapter, they are a good place for me to pick just one to serve of an example of all of them.

The intercession story that we’ll look at in the Book of Numbers is the very last one, an event that occurs after the Israelites have journeyed lengthily over the Sinai Peninsula up to the lands southeast of Canaan, lands called Midian, or Moab. On the way to Moab, the Israelites had already killed every living person as they passed through a land called Bashan. As they prepared for the wholesale slaughter of Moab, the Moabite king tried to get a powerful seer to leverage curses against the Israelites. God came to this seer, however, and intervened, and soon Moab was ripe for the taking. Some form of military victory was won against Moab, although it wasn’t the genocide that was carried out against Bashan. On the contrary, many Moabites were left alive, and the Israelites began fornicating with their women. God was utterly enraged. God told Moses “Take all the chiefs of the [sinning Israelites], and impale them in the sun before the LORD, in order that the fierce anger of the LORD may turn away from Israel” (Num. 25.4). One Israelite was executed in just this way. Later, Aaron’s grandson Phineas saw an Israelite who’d returned to camp with a Moabite woman, and he speared them both through the belly.

God’s wrath was still not sated. After a break for some more legalistic instructions, and more details on how and when to sacrifice God told Moses it was time to go to war on the Moabites. The purpose of this war was to “Avenge the Israelites” (31.2), evidently to get revenge on the Moabites since some of them had been willing to integrate culturally with the Israelites. The punitive campaign that ensued was gruesome. All of the males of Moab were killed. And thereafter Moses was dissatisfied with his officers for their mercy. God, and Moses sought more killing. I’m going to read Numbers Chapter 31, verses 15-18.

Moses became very angry with the officers of the army, the commanders of thousands and the commanders of hundreds, who had come from service in the war. Moses said to them, “Have you allowed all the women to live? These women here. . .made the Israelites act treacherously against the LORD. . .so that the plague came among the congregation of the LORD. Now therefore, kill every male among the little ones, and kill every woman who has known a man by sleeping with him. But all the young girls who have not known a man by sleeping with him, keep alive for yourselves.” (Num. 31.15-18)

Those again are Moses’ instructions to the Israelites. The narrator makes it clear that in addition to the huge numbers of sheep, oxen, and donkeys taken from the slaughtered Moabites, the Israelites took 32,000 virgins, presumably to be forced into prostitution or marriage.

The violence against the Moabites finally sated God’s anger in the Book of Numbers. The 600,000 people of the twelve tribes of Israel migrated northward. On the outskirts of Jericho, on the east bank of the Jordan river, God told Moses they were about to cross into the Promised Land, and he set out some additional rules for the Israelites. He specified how pastures ought to be laid out around towns. He delineated rules for cities of refuge, where accused persons might seek solace from vigilante justice. And God disentangled some inheritance rules for wealth passing through daughters. With these latest regulations in place, and the chaotic journey of the Israelites through the wilderness of Sinai and the territories of Bashan and Moab complete, the Book of Numbers finally concludes. [music]

The Pentateuch, Book 5: Deuteronomy

Let’s talk about Deuteronomy. Plot-wise, the Book of Genesis tells of the earliest patriarchs. The most important are Adam, Noah, Abraham, Jacob/Israel, and then Joseph. Then there’s Book 2, Exodus. Exodus is about Israel’s great great grandson Moses, and Moses getting everybody out of Egypt. Book 3, Leviticus, has no plot. That’s easy. Then Book 4, Numbers, which is the story of the wilderness journey across Sinai and into the outer reaches of Canaan. Now, Book 5, Deuteronomy, is the final book of the Pentateuch. I wish I could tell you that Deuteronomy is a gripping tale, which continues with a riveting account of the ongoing adventures of the Israelites. But Deuteronomy is something else.Get an image of Moses in your head. Picture him standing on the east bank of the Jordan River, with the sun setting behind him. Got that? The sun is setting on a generation of Israelites. They’re on the verge of crossing into the Promised Land. And Moses is retiring. And Deuteronomy is his retirement speech. It is a really, really long speech. And basically, it recounts what the Israelites have been through, and then it outlines, in elaborate detail, all of the behavioral rules that they must follow, a great many of which have already been covered in Exodus, Leviticus, and Numbers. Deuteronomy means “second law,” and much of Moses’ speech is a reworking of the legal codes found in Exodus, Leviticus, and Numbers. The writer of Deuteronomy, biblical scholars concur, lived in a different timeframe than the other writers who worked on the Pentateuch. He’s commonly called the “Deuteronomist,” and his worldview and moral compass are distinct to the books of the Bible that he wrote. Let’s take a quick look at the contents of Deuteronomy.

In his retirement speech, Moses recollected the military campaigns that transpired in the Book of Numbers. He proudly recounted the ethnic cleansing the Israelites had performed in Heshbon, and Bashan. Moses made clear that as the Israelites entered the lands of Canaan, that they must treat the Hittites, Girgashites, Amorites, Canaanites, Perizzites, Hiyites, and Jebusites a similar degree of wholesale ruthlessness, leaving not a single one of them alive. Not too long after, Moses assured his listeners that “the LORD your God. . .is not partial and takes no bribe. . .and. . .loves the strangers, providing them food and clothing. You shall also love the strangers, for you were strangers in the land of Egypt” (10.17-19). There’s obviously some inconsistency there.

This paradox runs through the center of Deuteronomy. On one hand, Moses emphasizes the kindness, and forbearance of God. On the other hand, he stresses necessity of killing anyone guilty of apostasy, and all of their neighbors, and even their livestock, and lays out a draconian legalistic code, imposing the death penalty unstintingly. But to stick, once more, with just the narrative portion of the Pentateuch, there’s really only one thing that happens in Deuteronomy, excepting Moses’ sizable speech.

Moses told the Israelites that he was a hundred and twenty years old. He had been informed by God he wouldn’t be crossing the Jordan. Then, Moses was summoned by God, along with a man named Joshua, who would take up Moses’ mantle as leader of the Israelites. God warned Moses that the Israelites would forget him in the Promised Land, and so Moses wrote down the Book of Deuteronomy itself. God also told Moses to write down a song to remember him by. Moses sung his song to the Israelites, offered a long blessing to his people, praising each of the twelve tribes. He then died, and was buried by God himself. The Book of Deuteronomy, and the entire Pentateuch, closes with the words “Never since has there arisen a prophet in Israel like Moses, whom the LORD knew face to face” (34.10). Because almost all of Deuteronomy is made up of legalistic codes rather than narrations of events, we can consider it covered for today’s purposes. [music]

Parallels: Ancient Near Eastern Creation Stories

So that was a summary of the narrative portions of the Pentateuch, narratives which are mostly in Genesis, Exodus, and Numbers. We went pretty quickly through the main events of the Pentateuch, and we’ll come back to some of the key ones from time to time in episodes to come. But what you just heard, summary though it was, was the most famous part of the Protocanonical books in all Bibles. The only comparably well-read swathe of the Bible are the Gospels of Matthew, Mark, Luke and John in the New Testament, and we’ll explore those in great detail later on. In the remainder of this show, I want to tell you a bit more about the cultural and historical milieu from which the narrative portions of the Pentateuch emerged. We began our podcast with Ancient Egyptian and Mesopotamian cultural history, and with more of this history coming to light every year, we’re beginning to understand, more and more, some of the narrative traditions that were out there while the Bible was being set down.

The reconstructed Ishtar gate at Babylon, Mahaweel, Babylon Governorate, Iraq. Scholarly consensus suggests that the Priestly Source of the Pentateuch was active during the post-exilic or early Persian period, and thus after the Israelite elites had been exposed to almost two generations of Mesopotamian culture. Photo by Hamody al-iraqi.

Let’s begin exploring the roots of the Pentateuch by thinking about creation and flood stories. There are a lot of them. From Bronze Age Pyramid Texts in Egypt that describe the world being created out of primordial water to the creation and flood story in Ovid’s Metamorphoses, in which a single couple, Deucalion and Pyrrha, survive a global flood and repopulate the earth, antiquity left behind a lot of texts that sound like the opening chapters of Genesis. Generally, the story is that an initial creator deity appears in a chaotic welter of water and darkness, and fashions the sky and land. Then, this deity or its successors create life, including humanity. The next part of the story is always a dramatic one. Strife between deities, or between humans and deities, leads to war and catastrophe – a flood to punish humanity, or a war between generations of gods. But following this catastrophe, resolutions are made for a more harmonious epoch to come, either because an older and primordial set of deities is subdued, or because humanity and deities have sealed an agreement for better times to come. The Bible contains all of this, with the stories in Genesis that we read today, as well as a tale at the end of the Book of Job in which the Old Testament God brags about having subdued a primeval creature called the Leviathan.

This – a creation out of the murk, strife between initial generations, and then the outset of a more peaceful era – this is, pan-culturally, our creation narrative. We find it in tales that have survived from all over the Ancient Mediterranean and Near East, in narratives that came about before the Book of Genesis, like the Enuma Elish, various Ancient Egyptian texts, the Eridu Genesis, Hittite Kumarbi cycle, Ugaritic Baal cycle, and Hesiod’s Theogony, as well as creation tales that came about after the Book of Genesis, like Plato’s Timaeus and the aforementioned Metamorphoses of Ovid. A century ago, the Swiss psychoanalyst Carl Jung popularized the notion that a collective unconscious in all of us is filled with archetypal symbols – symbols like water, a great mother figure, a tree of life, and numerous other elements recycled all over world mythology. And while it’s tempting to hypothesize about some sort of pan-human cultural mist that floats around from person to person and puts ideas in our heads, a more grown-up explanation is that we have always been a footloose, curious species, that we have always immigrated and moved around, that we were connected on an intercontinental scale by the Middle Bronze Age.

Due to these interconnections, it is little wonder that Genesis, as we saw back in Episode 2, tells a creation and flood story that’s closest in all ancient mythology to the Atrahasis of Babylon, a popular Akkadian story generally dated to the eighteenth century BCE. The story of the Atrahasis, as you may remember, is as follows.

In the beginning, everything was roiling, primordial of darkness. Then the waters and lands were separated. Then the dome of heaven was built. Great leviathans and monsters swarmed in the ocean, and God vanquished them. And after a time, God rested. Soon, humankind was made, fashioned both from clay and divine material, and after almost no time at all, humankind was compelled into an existence defined by physical labor.

Soon, man began to vex God. God planned a cataclysmic flood. A single pious man was given instructions to build a vast boat, on which he installed his family, and a huge variety of animals. The flood raged, obliterating humanity, and when it was over, the boat became lodged on a great mountain, surrounded by floodwaters on all sides. The pious man then sent forth birds, to see if they could find land, and when one of them did, he knew his tribulations were complete.

After this, God and the pious man and his ancestors had a new covenant. The pious man made animal sacrifices to God, and seeing them, God resolved to treat the pious man and his ancestors with justice and clemency.

As you certainly know from today’s episode, this is the story of Genesis up until we get to Noah and the aftermath of the Biblical flood. But it’s also the story of the Enuma Elish and Atrahasis, the popular Akkadian creation stories that had been circulating around the Tigris and Euphrates since around 1,800 BCE. In these tales, Gods create men out of raw materials. A deity in the Enuma Elish announces, “I will knead blood and bone into a savage.”4 In Genesis, God “formed man from the dust of the ground” (Gen 2:7) and he makes Eve out of one of Adam’s bones. Let’s look at another parallel. The physical formation of a man by a deity is of primary importance in the Ancient Egyptian hymns to the gods Ptah and Atum. These hymns were discovered carved in granite and written on papyrus, both of them dating back to before 1200 BCE, and Ancient Egypt’s creation stories bear close resemblances to the one in Genesis.

At the beginning of things, reads the ancient papyrus about the Egyptian god Atum, “There were no heavens and no earth, / There was no dry land. . .There was not a single living creature.”5 Comparably, Genesis describes how “In the beginning. . .the earth was a formless void and darkness covered the face of the deep” (Gen 1:2). To look at another parallel from Ancient Egypt, a Late Bronze Age stele written about the creator deity Ptah announces that “The. . .living were created in the image of Ptah. / All formed in his heart and by his tongue.”6 In Genesis, “God created humankind in his image” (1:27) and “breathed into [man’s] nostrils the breath of life” (2:7). With his acts of creation completed, the Egyptian creator “Ptah rested and was content with his work,” just as God in Genesis “rested on the seventh day” (2:2) after he “saw everything that he had made, and indeed, it was very good” (1:31).7 Considering these parallels, and many others, it doesn’t seem too farfetched to conclude that some widespread Ancient Near Eastern creation stories likely influenced the one that opens the Bible. Canaanites had been in and out of Egypt since at least the Hyksos dynasty that began in 1670 BCE, and the generations of Israelites whom scholars believe produced the flood and creation stories spent 47 years in the city of Babylon, if not longer, where the old Akkadian flood and creation stories still circulated.

The flood story of Atrahasis – the one that, even at a granular level, so closely resembles Noah’s, is also told in the Epic of Gilgamesh. And Gilgamesh has another element in common with the early chapters of Genesis – a mortal who comes close to the possibility of immortality, only to find it impossible. That story – of coming close to immortality, making a mistake, and being punished for it, is also pervasive throughout the Ancient Near East and Mediterranean. It happens to Adam and Eve. And Gilgamesh also loses immortal life due to a serpent. The plant Uta-naphisti had told him about, as Gilgamesh is bathing, is stolen from him by a snake, depriving him of eternal life. The Mesopotamian folk hero Adapa, whose stories were discovered in the Library of Ashurbanipal along with Gilgamesh’s, also comes within a hair’s breadth of immortality. A god offers Adapa, “Eat our life-giving bread. / Drink our life-giving water. / You, mortal, will become immortal.”8 But Adapa refuses, and his refusal seals the fate of the humans who come after him. Stories like these – mortals coming to the verge of immortality, and then stepping back, extended beyond just Mesopotamia and Canaan. Even way out in the world of the Aegean and Asia Minor, the story of the Lydian king Tantalus bears the same pattern. A man steals ambrosia, the food of the gods, and has their mysteries revealed to him, only to thereafter commit terrible transgressions and be punished in Hades forever after. Or, theme with variation in the poet Hesiod – Prometheus tricks Zeus into acquiring fire, a divine mystery, and afterward Prometheus was cursed with the coming of Pandora and her fateful jar, which dooms mankind to toil and trouble. Forbidden apples, plants at the bottom of the sea, divine food, water and ambrosia, and forbidden fire – these things all have the same results in ancient literature that’s come down to us.

Original sin stories like these also serve an important function. They are etiological tales about why things are hard for us today. Pervasive across the Ancient Mediterranean was a story that we often call the “Ages of Man” narrative. In this story, there was a gold age, and a silver age, and a bronze age, and now we are living in a much dingier and more debased age. Hesiod told this story. Genesis, Jerome, Ezekiel and Daniel all tell this story.9 Roman poets, like Catullus, Virgil, Horace and Juvenal, all left behind versions of it.10 The ages of man narrative, a story of decline and fall, generally assigns humanity responsibility for our own sufferings. It is not the fault of our gods that our lives are difficult – it is due to some ancient mistake that tarnished what might have otherwise been a more peaceful and happy tenure on earth. We seem to love writing and sharing these narratives that, like the Tower of Babel story, involve mortals reaching for the power of immortality, and reaching too far, and having their overweening hopes dashed by one consequential mistake.

Babies Adrift and Feuding Brothers

There are, then, plenty of analog narratives with parallels similar to the opening of Genesis. And moreover, the idea of history as a decline and degeneration from a golden age was ubiquitous in the ancient world. While the opening chapters of Genesis, then, have numerous commonalities with other creation, flood, and fall-from-grace stories that have also survived from antiquity, the Pentateuch more broadly has some more salient parallels with other texts that are worth knowing about. Another famous instance of the Pentateuch possibly borrowing from other narrative traditions comes after the Book of Genesis. From the Book of Exodus onward, Moses is at the center of the Pentateuch, and his origin story is famous. “My mother, a priestess, conceived me and bore me in secret, / she put me in a basket of reeds, sealed its lid with pitch; / she cast me adrift on the river from which I could not arise, the river bore me up.”11 These words are written about Moses, right? Actually, they’re not. They’re about the childhood of Sargon, who lived almost a thousand years before Moses was said to have lived, around 2300 BCE, and had legends of his birth inscribed on stele and cuneiform tablets. Just as Sargon’s mother “put me in a basket of reeds, sealed its lid with pitch, [and] cast me adrift on the river,” Moses’ mother “got a papyrus basket for him, and plastered it with bitumen and pitch, [and] put. . .it among the reeds on the bank of the river” (Ex. 2:3). And like our friend Odysseus meeting princess Nausicaa in the land of the Phaeacians in the Odyssey, Moses, once cast adrift, was discovered, clothed, and taken to safety by a bathing princess, and soon thereafter ingratiated a royal household.These parallels – like the ones we’ve already seen concerning the creation of the world, of the creation of man, of Moses, are all over the Pentateuch. The sibling rivalries of Cain and Abel, and Jacob and Esau, are par for the course in Ancient Near Eastern narrative traditions that focus on brothers fighting brothers, like Egypt’s story of Anubis and Bata, recorded before the Bronze Age Collapse.12 Barren wives and parents praying for children fill the Pentateuch, and other ancient texts, like the Ugaritic story of Aqhat, which is referenced in the Book of Ezekiel. The Bible’s demigods, or Nephilim, seem to come from a northern tradition about beings called “Rephaim,” or deified ancestors, beings mentioned in Genesis, Deuteronomy, Joshua, Job, and Isaiah.13

Seeing these different strands of influence behind the Pentateuch doesn’t need to diminish our appreciation of it as a text – a text that persisted against all odds. The transmission of stories from generation to generation, is, with important exceptions, a process of survival of the fittest, and the Old Testament, for its massiveness, power, and its capacity to synthesize many traditions, survived for a reason. Nonetheless, according it a unique respect doesn’t mean that we exempt it from close study – even the parts of it that are most sacred, and most central. I am talking, specifically, about the God of the Old Testament.

El, Elyon, Elohim, Yahweh, El Shadday, Yahweh Elohim

You cannot read the Old Testament without noticing that its central figure – God, of course – exhibits many very diverse patterns of behavior. He has many names in Biblical Hebrew – El, Elyon, Elohim, Yahweh, El Shadday, Yahweh Elohim. He is sometimes kind. He tells Aaron in a beautiful verse in Numbers, “The LORD bless you and keep you; / the LORD make his face to shine upon you, and be gracious to you; / the LORD lift up his countenance / upon you, and give you peace” (Num. 6.25-6). Later, in Deuteronomy, God emphasizes that he is a being who “is not partial and takes no bribe, who executes justice for the orphan and the widow, and who loves the strangers, providing them food and clothing” (10.17-18). Yet this same god who loves strangers orders mass child murder, impalements, capital punishment for dozens of offenses, and demands a multi-generational campaign of ethnic cleansing that continues hundreds of pages into the Historical Books. The Old Testament God has many names, and many characteristics, being sometimes a distant, numinous deity out of physical reach of the Israelites, and at others blowing into Adam’s nostrils, sniffing the scent of Noah’s sacrifices, and wrestling with Jacob. The Old Testament God is sometimes brutal, and other times kind; sometimes otherworldly, and other times anthropomorphic. For all of these reasons, for over a hundred years, Biblical scholars, looking closely at the Hebrew names of God, and the vocabulary and interests of different portions of the Old Testament, have argued that it is the product of many people, over a number of centuries, and that Old Testament God is a composite of multiple Canaanite deities.

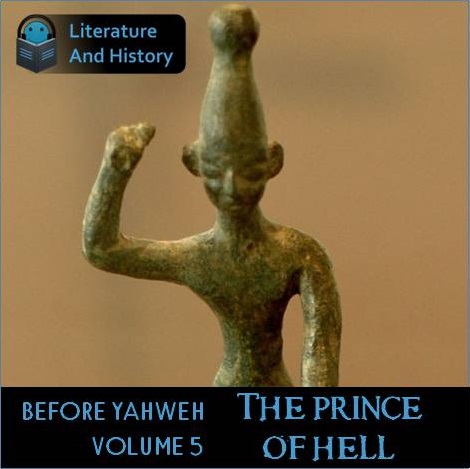

The Canaanite patriarchal deity, El. The Biblical Hebrew words “Elohim,” “El-Shadday,” and “Israel,” used throughout the Pentateuch, all share this deity’s name. The figurine is at the Oriental Institute Museum at the University of Chicago.

El, when you read the about him in the Ugaritic texts, is a sort of sleepy grandfather figure. El’s epithets are “the Kind,” or “the Compassionate.”14 In Ugaritic art, he was shown as a beneficent, bearded father figure, and associated with a bull. And El ruled over other Ugaritic gods, among them Baal, the Canaanite storm God, Asherah, El’s wife, and Anat, El’s powerful daughter. El was, in short, a distant, otherworldly being who dealt with his fellow deities at a distance. In some of the El stories, he is a bumbling old man with erectile dysfunction, and in others, embarrassingly drunk.15 Altogether, though, the Canaanite deity El was kindhearted and not particularly threatening – an utterly different figure from bombastic thunder gods like Zeus and Marduck.

El’s name is all over the Old Testament, both in its singular form, El, and its plural form, Elohim. When God reveals the name Yahweh to Moses, if we use the Ancient Hebrew words for God’s names, Exodus tells us, “Elohim spoke to Moses, and he said to him, ‘I am Yahweh. I appeared to Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob as El Shadday, but by my name Yahweh I was not known to them.”16 El Shadday means “El of the Mountain,” a reference to a “cosmic mountain” mentioned elsewhere in Ugaritic texts on which El lived and ruled over the other deities of Canaan.17 The Old Testament is quite frank about God’s multiple names. Chapter 6 of Exodus distinguishes between “earlier and later names of the God of Israel” (Ex 6:2-3). And numerous moments of the Old Testament mention multiple Gods. God is depicted as presiding over assemblies of Gods in 1 Kings 22 and the first chapter of Job. One of the Psalms begins with the words “Elohim has taken his place in the / Assembly of El, / in the midst of the gods he / holds judgment” (Ps 82:1). Similarly, God is the superintendent of many gods in the famous Song of Moses in Deuteronomy: “When Elyon apportioned the nations, / when he divided humankind, / he fixed the boundaries of the peoples / according to the number of gods” (Deut 32:8).

El, Elohim, El Shadday, Yahweh – if this is confusing, the conclusion biblical scholars have often drawn from all of it is straightforward. Many parts of the Old Testament bear the marks of a polytheistic past. They show the people of Israel and Judah co-opting and adapting older northern stories about El and his pantheon, and changing this El into a different being – a more anthropomorphic warrior deity, or storm god, called Yahweh. Yahweh is a name that may have come from a nomadic people called the Shasu who lived along the Jordan River. Egyptian texts from the 1300s and 1200s BCE survive that associate these Shasu nomads with a deity called Yhw or Yahu.18 Whatever variant of the way his name was spelled, the Canaanite deity Yahweh may have had a wife. Yahweh was linked to the Canaanite goddess Asherah at a religious site used during the 700s BCE in northeastern Sinai called Kuntillet ‘Ajrud – iconography and text at the site identify Asherah as Yahweh’s wife or consort.19 What I’m telling you here is the tip of the iceberg, by the way – book length studies of most the parallels I’m mentioning exist, and footnotes to this episode transcription should get you started if you want to know more. Anyway, if Yahweh is an adapted version of the Canaanite deity El, it is no wonder that early practitioners of the Israelite religion still associated Asherah, El’s wife, with Yahweh. While Yahweh has much in common with the Canaanite deity El, he perhaps has even more in common with the Canaanite deity Baal. Let’s talk about Baal, about whom a whole narrative saga has been unearthed from the ancient city of Ugarit.

There was a pervasive story in the Ancient Near East, a story that all the major cultures told. This was the story of a brave young storm god who fought and bested the ocean. The Enuma Elish tells this story – Marduk defeats Tiamat and establishes himself as the chief of the gods. In the Theogony and elsewhere in ancient Greek myths, Zeus fights the giant monster Typhon or Tiphoios, toward the beginning of creation. The Canaanite deity Baal, in the Ugaritic Baal cycle, conquers the ocean, or Litan, similarly, establishing his primacy. And the Old Testament bears the remnants of a similar story, not about a Litan, but a Leviathan. God assures Job that he bested this Leviathan, a terrifying sea monster of the likes of Babylonian Tiamat, Greek Tiphoios, or Canaanite Litan. As the Book of Job recounts, “With [God’s] power, he stilled the sea, / with his skill he smote [the sea], / with his wind he bagged Sea, / his hand pierced the fleeing serpent” (Job 26:12-13). Following their victories over the ocean, Marduk, Baal, and Yahweh all have structures carefully built in their honor – for Marduk and Baal, grand temples, and for Yahweh, both the Tabernacle and, as we’ll soon see, a temple in Jerusalem.

L&H’s full length bonus episode on the Baal cycle is available on our Bonus Content page.

We began a moment ago by considering the different temperaments and names of the Old Testament God, a figure given different titles and epithets throughout the Bible’s earliest books. Considering what we’ve just learned, the different temperaments of the God of the Old Testament may reflect the fact the broader religious history of ancient Canaan. God in the Pentateuch, which we covered today, has many characteristics. Sometimes, especially throughout Genesis, Exodus, Numbers, Psalms and Job he is the wise distant patriarch El that we see in the ancient Canaanite tablets discovered in Syria in 1929. At other times, he is a war god like the divinities in Homer’s Iliad, a swashbuckling, temperamental figure who forces the Pharaoh’s army to chase him in Exodus just so that he can crush them and show them his might. His alternations between gentle, sagely wisdom and militant braggadocio, between blessings and unspeakable curses, have puzzled readers for thousands of years. And again, one common answer to his temperamental inconsistencies, made possible by the archaeological discoveries of the past two centuries, has been that the being called El, Elohim, El Shadday, and Yahweh is an amalgamation of diverse theological traditions. [music]

The Pentateuch and the Historical Rise of Monotheism

We’re almost through for today. Let’s leave El, or Elohim, or Yahweh for a minute. Actually, let’s put down the Bible, too. Let’s climb into a hot air balloon, and float way, way up above the lands of Canaan, so that we can see the Aegean Sea, and the mountains of Turkey – the distant green of the Nile Delta and the vast reaches of the Mesopotamian desert. There’s been an elephant in the room for this entire show. This elephant is bigger than any single idea I’ve covered in the podcast so far. And the name of this elephant is the historical rise of monotheism. Up here, in our air balloon, with the Jordan River far below us, and the whole Fertile Crescent in sight, we can see the broad, warm landscape that nurtured this idea and brought it to life.In our very first episode, we looked at a clay tablet found in the city of Uruk, impressed in 3100 BCE – essentially a receipt for a sacrifice to the Sumerian goddess Inanna. “2, Sheep, God, Inanna,” it said.22 The early Mesopotamians believed that their gods actually dwelt in their temples – often embodied by a sacred object, which received worship and sacrifices. Their gods were not distant vaporous entities that dwelt in a separate spiritual world. They were embodiments of palpable things – fresh water, wind, sex, and fire. The Israelites’ worship of the golden calf in Book of Exodus, to the authors of the Old Testament, is not only an instance of sacrilege – a direct violation of one of the commandments. The golden calf is also a moment of cultural backsliding. You can imagine Moses saying, “Are you really praying to a golden calf? Come on, folks, it’s the Late Bronze Age, not 3,000 BCE. Get it together!”

The move from naturist polytheism to the worship of numinous otherworldly gods is evident throughout the Ancient Near East during the first and second millennia BCE. Assyriologists have noted from surveying thousands of clay tablets a rhetorical shift wherein believers began addressing the gods all together as a body that determined human fates, rather than diverse individual spirits reigning over the various cogs and wheels of physical reality. By the time of Tiglath-Pileser’s Assyrian empire in 1120 BCE, Mesopotamian religious artwork had begun depicting deities with symbols – stars, crescents, and so on. This was a big change from the way gods had been delineated a thousand years earlier, during the reign of Sumerian Sargon, when gods were illustrated merely as people. At the center of this change in the lands of the Tigris and the Euphrates was the Assyrian god Ashur, a being who received increasingly exclusive worship in the Assyrian empire before and during the time the Assyrians conquered Israel and Judah.23 Whether the Judahites were the sole source of the new monotheism, a product of the greater cultural forces around them, or something in between, the Judahites in the 600s BCE lived during a time in which gods were being increasingly imagined as distant, ethereal, and omnipresent, rather than powerful hominids with specific physical attributes. Looking very closely at the names and deeds of God in the Pentateuch, especially if we read them alongside other Ancient Near Eastern religious traditions, reveals the hidden story of the spread of monotheism.