Episode 21: The Bible’s Magic Trick

The Old Testament, Part 7 of 10. In the Book of Psalms, a single, fascinating, familiar linguistic device propels the world’s most famous poems.

| Read Transcription | References and Notes |

| Episode Quiz | Episode Song |

| Episode on Spotify | Episode on Apple Podcasts |

| Previous Show | Next Show |

The Psalms and the Literary Device that Drives Them

Hello, and welcome to Literature and History. Episode 21: The Bible’s Magic Trick. This is the seventh of ten episodes on the Old Testament. In this show, we’re going to talk about the Book of Psalms, a collection of 150 lyric poems, subdivided into five sections, that together make up one of the longest books in the Bible.

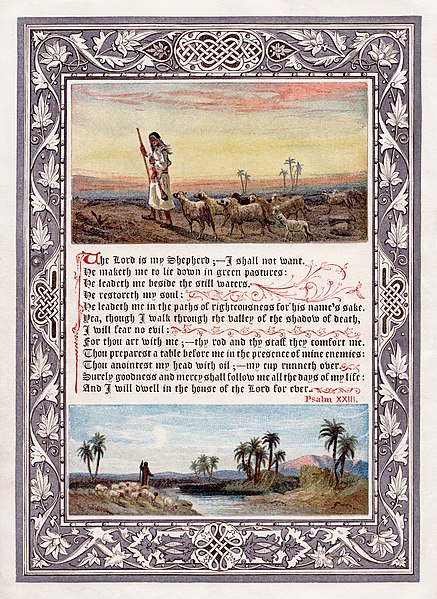

Psalm 23 in a nineteenth century King James Bible. The poem is arguably the most well known piece of verse in the Anglophone world.

As we’ll learn in future episodes, lyric poetry, or short poetry, sometimes associated with a lyre and frequently discussing personal emotional experiences, shows up in the literary record as a genre for the first time in the 600s BCE. It was likely occasional poetry during its initial centuries – in other words, poetry written for specific occasions to be performed with musical accompaniment before an audience. Audiences would have frequently included patrons who had commissioned the poems themselves, and the earliest lyric poems would have hardly ever had much of a life span beyond their first stagings. Before widespread literacy, when writing materials were expensive and less sturdy than they are now, and when no copyrights protected authors from having their work circulating for free, the safest way to make money as a poet was to perform one’s poems in public for an immediate paycheck. I think nowadays we tend to think of poetry as something very profound and private – an author sets down meditations on the human condition that are revered somewhere by someone else in isolation. In antiquity, though, poetry was most often a public affair. And while some poems were read at parties, dedications, inaugurations, and athletic games, one of poetry’s roles was also, always liturgical.

The Psalms almost certainly served a role in temple services in ancient Jerusalem. Taken together, they are a stockpile of short works concisely expressing some of the Tanakh’s core messages – reverence toward God, ire at Israel’s adversaries, sadness at the privations Israel had endured, hope for better times to come, and so on. For a temple service in antiquity, just as much as in a synagogue or church service today, the Psalms have frequently been used to underscore the content of a service or sermon, bringing the voices of the congregation itself in to sing, or read along, with the Bible’s short poems.

I think most people listening have likely read a Biblical Psalm or two, and it’s certainly not difficult to understand that the Psalms are a large book of the Bible filled with short poems. In this episode, our goal will be, first of all, to get a high-level view of all 150 Psalms – their relative length and breadth, and how they generally fit into one of several different categories. Once we’ve taken a tour of these different categories and heard some representative instances of different kinds of Psalms, we’ll be able to go a little bit deeper.

Our approach to the Bible in this podcast has been historicist. We’ve used archaeology, comparative mythology, and less often explored later interpretations of biblical books in order to understand where the Old Testament came from, and how it was understood in subsequent centuries. Since we’ve already spent six episodes exploring the historical background of the pre-exilic, exilic, and immediate post-exilic periods, we have a pretty good idea of the overall history behind the Tanakh. We know that a great deal of it was written between about 640 BCE – the first year of Josiah’s kingship in Jerusalem, and 540 BCE – the last year of the Babylonian Captivity. We know that those who wrote it did so with firsthand experiences of a series of invasions by powerful foreign armies, and eventually, a forced exile to the territory of their conquerors. We know that one of the Old Testament’s central purposes was to try and make sense of why the Israelites, who had a sacred covenant with God and were this God’s chosen people, continued to have to endure so much loss and trauma. This is the cardinal question of the Tanakh, whether it’s explored across hundreds of chapters, as in the Historical Books that stretch from Judges to Esther, or whether it’s explored in the Book of Job, which we read in our previous program.

Because we have a decent overall understanding of the history behind the Old Testament, at the tail end of this episode, after we get an overview of all of the Psalms, we can go a little deeper into the structure of the Bible’s lyric poems. Those of us who get literature degrees, like your host, are trained to understand literature as part of cultural history. But we’re also trained to do more technical things with literature. These things include scansion, or pinpointing the meter and feet of a line of verse. They also include identifying literary devices within texts, from familiar things like alliteration, metaphor and simile, to slightly less familiar devices, like anaphora, epistrophe and chiasmus, to dozens of more esoteric devices within literature – things like pleonasm, apophasis, polysyndeton, litotes, syncope, and many others. I bring up the issue of literary devices here at the beginning of the show because the Psalms illustrate one of the Bible’s characterizing literary devices. It is a device so pervasive within the Old Testament, that I have named this show “The Bible’s Magic Trick” in honor of the device – one that’s virtually everywhere at any juncture when the Tanakh is written in verse rather than prose. We’ll get into the nitty gritty of the Old Testament’s characterizing literary device soon. For now, let’s get to know the Psalms – the overall breadth and content of the 150 most widely circulated poems in human history. [music]

The Scope and Utility of the Psalms

There are 150 Psalms. Let’s get every single one of them set out in front of us on a gigantic table for a second, and make some basic observations about their length and the scope of their content. First off, 150 – the total quantity of Psalms – is the key number to remember. The Greek Bible includes Psalm 151 – a short narrative of King David remembering how he grew up and then went to fight Goliath, and this additional Psalm was also found in Hebrew in the Dead Sea Scrolls. But for the vast majority of Judaism and Christianity’s lifespans, the Anglophone world didn’t deal much with Psalm 151, so we’ll stick with just the normal 150.Let’s begin by talking about length. The Psalms have a variety of lengths. The shortest Psalm, Psalm 117, is only two verses. Here’s Psalm 117 in its entirety.

Praise the LORD, all you nations!

Extol him, all you peoples!

For great is his steadfast love toward us

and the faithfulness of the LORD endures forever.

Praise the LORD!1

So, that’s the shortest Psalm. What about the longest Psalm? That would be Psalm 119. With 176 verses, Psalm 119 is almost a hundred times longer than the one I just read to you. It’s a freak in the Bible, being over a hundred verses longer than the second longest Psalm – that’s Psalm 78, which weighs in at 72 verses. While there are a few outliers – in other words very short Psalms, and very long Psalms, with most of these poems, if you printed them out on printer paper in twelve-point font, they would be between half a page and a page and a half.

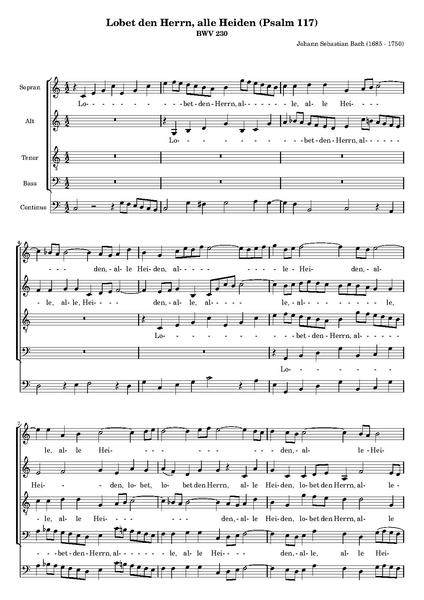

BWV 230, written for voice. Bach’s arrangements often put beautiful harmony and counterpoint over the familiar language of the Pslams.

While all of the Books of the Old Testament are intended to be read and contemplated, Psalms, as I mentioned earlier has always had an additional purpose – a liturgical purpose. The Psalms were, from the beginning, intended to be used in a public worship setting. They were meant to be accompanied by music, in the Temple in Jerusalem. Many of them have superscripts indicating that they’re supposed to be played and sung in a certain fashion – with stringed instruments, or under this sort of direction, or to this or that (now unfortunately lost) melody. Something that I mentioned before, but always bears repeating, is that religion in the Ancient Near East and Mediterranean was initially a public affair. It was a thing of spectacle, and sound, and sight – it involved animal sacrifice, processions, costumes, and decorations. The Psalms, thus, were not a little volume meant to be read in the isolation of one’s home. They were like the libretto to an opera – one that took place at the Temple in Jerusalem. When we read them today, long after the Protestant Reformation, it’s easy to forget that – Protestantism’s emphasis on individuals reading the Bible for themselves, in general, assumes a level of literacy and mass-produced texts that simply didn’t exist in the ancient world, when Hebrew and Aramaic speakers encountered Biblical texts in a performance environment.

Speaking of Protestantism, Martin Luther wrote extensively about the Psalms. In his severe emphasis on individuals reading scripture for themselves, Martin Luther may have occasionally ignored the public role that books like Psalms played in the Jerusalem Temple when they were first written. But nonetheless, Luther understood how the Psalms fit into the Biblical canon. In a preface to the Book of Psalms, Luther wrote that the book “might well be called a little Bible. In it is comprehended most beautifully and briefly everything that is in the entire Bible. . .so that anyone who could not read the whole Bible would have anyway almost an entire summary of it, comprised in one little book.”2 Modern Jews and Christians alike can understand Luther’s statement perfectly. The Psalms are like a summary of the Tanakh’s core ideas, a distilled index of the main tenets of Judaism. If you were a devout goatherd who lived on the outskirts of Jerusalem in 490 BCE, you would not own a copy of the Hebrew Bible. Part of the reason for this is that the Old Testament was still being written. You wouldn’t have read the searing story of the Babylonian conquest and subsequent diaspora told in the late Historical Books, nor the Prophetic Books’ messages of hope for the future, though this story and appendant truism would likely be a part of your overall culture. You could, however, attend the Temple service, and the music there, and collective ritual, and poetry being recited could still communicate a lot of the central themes of the Tanakh. That’s how, and where the Psalms were born, and the purpose that they initially served.

Still, even when they’re just words on the page, and not being sung in their original language to original melodies, the Psalms are powerful stuff. Concision is a potent weapon in literature and theology. When I used to teach Introduction to Literature classes, I would often use a crude, but somehow always effective analogy, to explain poetry’s power within the holy trinity of literature – that’s prose, drama, and poetry. Prose – meaning novels and stories, is a bit like beer. You sometimes have to read for quite a few hours before feeling the effect. Drama, or plays, whether in person or in private – is like wine. It’s classy, it takes effect a bit sooner, and sneaks up on you. And poetry – well – poetry is the stuff that comes in a little black bottle with the skull and crossbones on it. Pound for pound, it packs the biggest wallop – but it’s also the hardest to acquire a taste for. When Martin Luther called Psalms the “little Bible,” he understood perfectly well how much meaning was compacted into each Psalm. Any given Psalm, unlike, say, the long historical narrative of Kings or the contorted tirades of Jeremiah – any given Psalm can deliver its impact in a compressed timeframe, like a shot of holy spirits. That’s the unique power of the Book of Psalms, and, in some ways, its unique challenge. [music]

Authorship, Categories, and Liturgical Context: Three Scholarly Approaches to the Psalms

Individual Psalms don’t make for a difficult read. They’re succinct, clear, and even for those who don’t love poetry, very accessible. But reading the Book of Psalms as a whole is quite a challenge. For any human being, jumping from theme to theme and topic to topic more than a few times in the space of a fifteen minutes can be fatiguing. The Book of Psalms, if you’re crazy enough to try and plough through it from beginning to end, feels especially enormous. I did this once. Not to say that many people haven’t done the same thing – I’m sure people are doing it as we speak. But as I pushed through all 150 Psalms over the course of a couple of days, I learned, the hard way, that the wisdom and poetry books of the Bible can’t be treated like other parts of the Bible. We talked about the structure of wisdom literature a while ago, back in Episode 6 – the one on Ancient Egyptian wisdom literature – and the gist of what I want to recall from that show is that wisdom literature is intended to be read piecemeal, at separate intervals. Whatever your perspective on them, the best way to read the Psalms is to look at them one or two at a time. That’s what most of the remainder of this episode will be about.However, before we dive into some individual Psalms, let’s talk just a little bit more about Psalms as a whole. Thousands of years of scholarship have produced thorough analyses of every single Psalm, but as with any other scholarship on the Bible or Biblical archaeology, the ways that we have studied and understood the Psalms have changed over the course of Judaism’s lifespan.

Many early analyses of the Psalms investigated their authorship. The Bible frequently attributes them to King David – assuming that this tenth-century BCE Judahite monarch personally wrote a giant swath of the Bible. The theory of Davidic authorship is no longer taken seriously by Biblical scholars. David may have been a historical figure. We talked in previous episodes about the Tell Dan stele – that paving stone discovered in 1993 in the far northeast of Israel, covered in Aramaic and thought to have been carved in about 835 BCE, which mentions the “household of David.” But the monotheistic, temple-centered Judaism that existed in Jerusalem in, say, 490 BCE, when the Psalms were probably in liturgical use – this religion was born in the courts of the seventh-century monarchs Hezekiah and Josiah. It is quite difficult to believe, considering what archaeology and Biblical scholarship have unearthed over the past five decades, that a person from the 900s BCE could have articulated an ideology that wasn’t in circulation until three hundred years later.

It’s quite common in the Biblical canon for writings to be attributed to a patriarch. By saying that a piece of scripture came from the pen of Moses, or Abraham, or Solomon, or David, later scribes could lend a heft and legitimacy to their writings. A whole class of writings called the pseudepigrapha, composed within a few centuries of the birth of Christ, are all attributed to bygone patriarchs. The Book of Jubilees, used by the Ethiopian Orthodox Church, is said to have been a revelation to Moses. 1 Enoch, included in the Tewahedo Bible, too, is said to have been written by the great-grandfather of the patriarch Noah. The third book of Baruch, while not widely in use, attributes itself to the 6th-century BCE scribe Baruch ben Neriah, although 3 Baruch was likely written seven hundred years after his lifespan. Both within and outside of the Biblical canon, then, in the ancient world, attributing a text to a venerable ancestor was widespread. The traditional attribution of Davidic authorship to the Psalms is another example of ancient scribes working to legitimate their poetry through linking it with a revered forefather. Try and publish a poem under your own name these days, and good luck. But if you can somehow get publishers convinced that your poem is a lost work of Dickinson, or Pushkin, or Octavio Paz, it will be taken far more seriously. The same thing was true in 490 BCE.

So that general pattern of attributing the Psalms as a whole to King David, and linking them to moments in his life – that pattern of analysis had its day in the sun, but has become outmoded by other approaches. Let’s talk about these other approaches. The first time I read Psalms – again, foolishly, straight through – one method of analysis seemed immediately useful, and immediately intuitive to me. And that was the method originally pioneered by the great German biblical scholar Hermann Gunkel. Gunkel’s work on Psalms came at the end of his career, in 1926 and 1933.3 By this time, Gunkel, together with other pundits, had pioneered a school called “Form Criticism,” often associated with genre criticism. What this means, in the context of the Psalms, is that Gunkel considered their literary form, structure, and theme, and he grouped them together according to those structures and themes. This approach, when I first read Psalms, seemed very natural and logical. I mean it doesn’t take a huge amount of brainpower to put blue things next to other blue things, and red things next to other red things, apples together, bananas together, and so on.

Gunkel thus subdivided the Psalms into different categories. He discovered many poems had kingly attributions, and were composed on royal themes. Even more were hymns of praise toward God. He found that many of the poems expressed gratitude toward God, and grouped these together as Individual and Community Thanksgiving Psalms. He found that many of the poems were sad – and grouped these into Individual and Community laments. And finally, Gunkel observed a number of Psalms might be classified as wisdom literature, because of the worldly counsel that they offered. There were others, but the overwhelming number of the Psalms fit into these five categories – Royal Psalms, Praise Psalms, Thanksgiving Psalms, Lamentation Psalms, and Wisdom Psalms. An easy way to remember Gunkel’s classification is the sentence “Reading Psalms takes lots of work,” which begins with the same letters as “Royal, Praise, Thanksgiving, Lament, and Wisdom.” We’ll come back to these, and generally use Gunkel’s categorization to understand the Book of Psalms as a whole. But Gunkel was a fairly early figure in the realm of modern Biblical scholarship, and we should talk for a minute about the other approaches that have been used in the past century to understand the Psalms.

Another way that the Psalms have been understood was the approach of Hermann Gunkel’s student, Sigmund Mowinckel, a Norwegian professor most prominently interested in the worship practices of Ancient Israel. Throughout his career, which spanned from the 1920s to the 1950s, Mowinckel sustained an interest in the way that Psalms, and moreover the Hebrew Bible in general, were used. Mowinckel’s functionalist approach to looking at the Old Testament was a refreshing alternative to the misguided assumption that ancient Israelites experienced the Bible in the same way that we do – mass produced and standardized on the printed page. Mowinckel’s cultural and anthropological interests to the Bible were a product of the renaissance in archaeology taking place during the first half of the 20th century.

So Hermann Gunkel had grouped the Psalms according to theme and pattern. And then Sigmund Mowinckel emphasized the importance of their use in temple rituals. There was one more major shift in Psalms scholarship, and this was thinking about the way that they were ordered. If you had a crush on someone, and you were making a playlist for this person, you might arrange the songs of your playlist in such an order that the playlist built in intensity, and had a certain thematic progression, or something like that. Saint Augustine, who wrote a huge analysis of the Psalms 1600 years ago, noted that “the arrangement of the Psalms. . .seems to me to contain the secret of a mighty mystery. . .[B]y the fact that they in all amount to one hundred and fifty.”4 What was this mystery? How does an overall story or logical progression unfold over the course of the 150 psalms?

Many, many, many people have tried to answer this question. The problem with trying to answer this question in a podcast is that you need to reference dozens and dozens of different Psalms to make an argument. It helps to have diagrams and tables, together with close linguistic analysis, too. The studies that have emerged on the subject of editorial arrangement of the Book of Psalms are erudite and insightful. Critics have studied the divisions between the psalms in the Hebrew Bible and proposed that in its entirety, Psalms tells the story of King David’s ultimately failed covenant with God.5 Another approach has been to claim that the order of the Psalms, as a whole, creates a narrative about trying to live a life of faith and wisdom in a fraught world.6 Another approach has been to argue that the Psalms, when read as a sequence, ultimately mirror the story of Israel’s birth as a kingdom, its scattering, and its reconstruction by a heavenly monarch, as told in the Bible’s Historical Books.7 Considering the editorial arrangement of the Psalms is the work of a book length study, though, and not a podcast episode. For our purposes, I think it will be easiest to stick with the fairly intuitive approach of Hermann Gunkel, that “Reading Psalms takes lots of work,” or that Psalms can be divided into Royal, Praise, Thanksgiving, Lamentation, and Wisdom poems. Unless otherwise noted, quotes from the Psalms in this episode will come from the NRSV translation in The New Oxford Annotated Bible, published by Oxford University Press in 2010. [music]

Psalm 19: A Royal Psalm of King David

Let’s start with a royal psalm. Psalm 19 announces that it is “A Psalm of David.”8 Being a royal Psalm, the poem announces itself as King David’s prayer to God. Psalm 19 begins with a statement of awe at the marvel of creation, then emphasizes that God’s laws are faultless, then petitions God to keep him sinless and clean, and ends with the famous lines, “Let the words of my mouth and the meditation of my heart be acceptable to you, O LORD, my rock and redeemer.”9 It’s one of the more famous short works in the Bible. Scholar and author C.S. Lewis wrote, “I take [Psalm 19] to be the greatest poem in the Psalter and one of the greatest lyrics in the world.”10 So let’s talk about Psalm 19 in detail a bit – perhaps not such a singular Psalm as Lewis proclaimed – but nonetheless a good, solid Psalm that perfectly exhibits the characterizing structural feature of Ancient Hebrew poetry. Here’s the opening.The heavens are telling the glory of God;

and the firmament proclaims his handiwork.

Day to day pours forth speech,

and night to night declares knowledge.

There is no speech, nor are there words;

their voice is not heard;

yet their voice goes out through all the earth,

and their words to the end of the world. (PS 19:1-4)

These opening lines marvel at the miracle of the world, emphasizing that day and night transmit a ubiquitous, silent message – a message of God’s power and glory. Psalm 19 then describes the miracle of the sun, and how the sun’s light washes over the whole earth. Analogously, Psalm 19 explains the law of God:

The law of the LORD is perfect,

reviving the soul;

the decrees of the LORD are sure,

making wise the simple;

the precepts of the LORD are right,

rejoicing the heart;

the commandment of the LORD is clear,

enlightening the eyes;

the fear of the LORD is pure,

enduring forever;

the ordinances of the LORD are true

and righteous altogether. (PS 19:7-9)

King David, the alleged speaker of the poem, prays for God to keep him safe from sin, to protect him from insolent people, and he prays that his prayer will be acceptable. And that’s the Psalm – 14 verses in all. So now that we have a Psalm in front of us, I want to talk about two tremendously important things. We’ll do the simpler one first.

A nineteenth-century illustration of the universe’s layout according to Psalm 19:2, along with other biblical verses.

I realize this is all English 101 stuff. But looking at the Psalms, it’s really important to remember that in Protestant, Catholic, and Greek bibles, Psalms is the first time you begin to hear a lot of first person singular. In Psalm 19, David prays, “Clear me from hidden faults. Keep back your servant also from the insolent. . .Let the words of my mouth and the meditation of my heart be acceptable to you, O LORD, my rock and my redeemer” (PS 19:12-14). There’s nothing distant about these words. They are earnest and direct. They invite you to read them out loud, and experience their sentiments. There are dozens, and dozens of voices in the Book of Psalms – ones that extol God, ones that dispense wisdom, ones that are bloodthirsty and dark, and others that are joyous and tranquil. The first person singular narrators who deliver the bulk of the Psalms, then, are an important component in making the poems so immediately accessible.

Parallelism in Biblical Hebrew: An Introduction

So, one the things that strikes us when we reach the Psalms in the Bible is their intimacy, an intimacy that comes largely from first person narration. Another is that it’s within the Psalms that the characterizing literary device of Ancient Hebrew poetry becomes truly hard to ignore for the first time. Literary devices are hard to deal with when you are reading poetry in translation. Things that have to do with the sounds of words, like alliteration, consonance, assonance, and rhymes are all, generally gone in translation. But some literary devices come across regardless of translation, and the Bible’s magic trick – that special feature of ancient Hebrew poetry to which I alluded earlier, is one of these. Scholar Walter Brueggemann calls the opening of Psalm 19 “a fine example of Hebrew poetic structure,” and it’s time to find out why.11 First of all I’m going to give you some examples of this structure from some different parts of the Bible. Here’s an example of it from Isaiah. “Zion shall be redeemed with judgment, / and her converts with righteousness” (Is 1:27). One from Amos. “[L]et justice roll down like waters, / and righteousness like an ever-flowing stream” (Am 5:24). Here’s one from Exodus. “The Lord is my strength and my might, / and he has become my salvation” (Ex 15:2). And yet another – this one from the Book of Micah. “[T]hey shall beat their swords into plowshares, / and their spears into pruning hooks” (Mi 4:3).So, you heard that, right? There were pairs of lines that went together. A single line introduces an idea. A secondary line reinforces or develops that idea. The umbrella term for this sort of structure is “parallelism.” An absolutely enormous amount of the Bible is written using parallelism – essentially, pairs of lines that lock together to drive home an image, or propel an argument, like the ones we just heard from different parts of the Tanakh. Let’s hear some extended Biblical parallelism from Psalm 19, that same Royal psalm with which we started.

The heavens are telling the glory of God;

and the firmament proclaims his handiwork.

Day to day pours forth speech,

and night to night declares knowledge.

There is no speech, nor are their words;

their voice is not heard;

yet their voice goes out through all the earth,

and their words to the end of the world. (PS 19:1-4)

Each of these four verses is a textbook example of Biblical parallelism. An idea is introduced, and then developed or underscored. Another idea is introduced, and then also developed or underscored. Then a third. Then a fourth.

Biblical poetry has many characterizing structural features. Old Testament scholarship has extensively analyzed the complex literary devices in the Psalms and elsewhere – metonymy, merism, synecdoche, hyperbole, metaphor, personification, and many more than these. But over the past century of so, the main thing you learn in a college class or personal study that covers Ancient Hebrew poetry is that it is absolutely chock full of parallelism – structure in which the first half of a line makes a statement, and the second half of the line does something to that same statement. We’ll talk a bit more about parallelism as we move forward, but I still wanted to introduce it before we got any further. So, now we’ve seen a Royal Psalm – a poem allegedly written by King David that celebrates the miracle of creation, and then asks for guidance and acceptance. Our mnemonic device from earlier, regarding the categories of the Psalms was RPTLW, or “Reading Psalms Takes Lots of Work.” That means we’re on “P,” so let’s move forward to the next category of Psalms, and look at a Praise Psalm. [music]

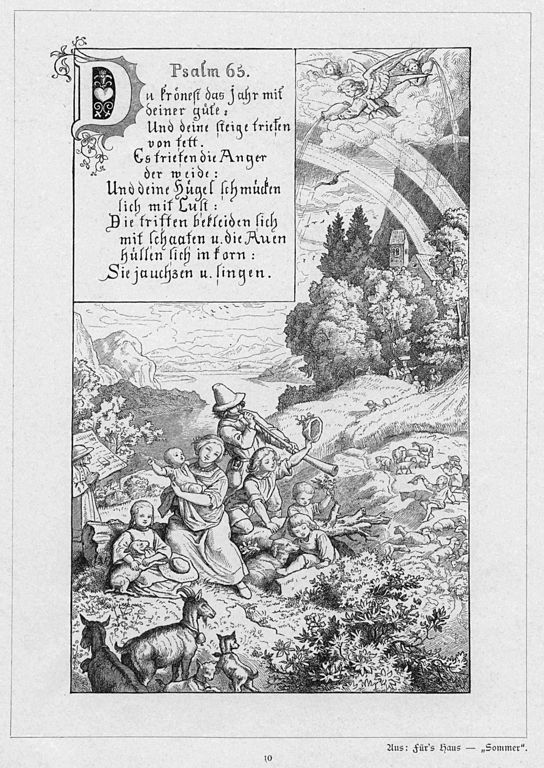

Psalm 65: A Praise Psalm

The Praise Psalms, while the name might lead you to believe that they are rather predictable in subject matter – praise the lord, celebrate God, and so on – the Praise Psalms actually have a surprising variety. One in particular, Psalm 65, stands out for a number of reasons, not the least of which is the craftsmanship of its language. Psalm 65 expresses gratitude at God’s forbearance, and then it launches into a beautiful summary of some of the miraculous things exist in the world as a result of the divine creation. I’ll read most of it to you now.As I read, pay attention to the way parallelism works in what you’re about to hear. Most often, parallelism works via what we might call recapitulation – a first clause introduces an idea, and a second and occasionally third or even fourth clause underscores that initial idea or simply repeats it in different language. At other junctures, parallelism doesn’t simply reiterate – it actually completes, often using symmetrical syntax, an idea that’s being expressed. I’ll pause a little longer than I usually would as I read this poem so as to indicate full line breaks as opposed to parallel clauses. Here’s, once again, most of Psalm 65.

Praise is due to you, O God, in Zion;. . .

Happy are those whom you choose and bring near to

to live in your courts. . .

By your strength you established the mountains;

you are girded with might.

Your silence the roaring of the seas,

the roaring of the waves,

the tumult of the peoples.

Those who live at the earth’s farthest bounds

are awed by your signs;

you make the gateways of the morning

and the evening shout for joy.

You visit the earth and water it,

you greatly enrich it;

the river of God is full of water;

you provide the people with grain,

for so you have prepared it.

You water its furrows abundantly,

settling its ridges,

softening it with showers,

and blessing its growth.

You crown the year with your bounty;

your wagon tracks overflow with richness.

The pastures of the wilderness overflow,

the hills gird themselves with joy,

the meadows clothe themselves with flocks

the valleys deck themselves with grain,

they shout and sing together for joy. (PS 65;1,4-13)

That’s again Psalm 65. Now, this is not, simply put, an angry psalm. It doesn’t ask for vengeance against enemies, or strength against the temptations of iniquity, or express sadness related to the loss of freedom, as dozens and dozens of poems in the Book of Psalms do. Instead, Psalm 65 is an exuberantly happy panorama of the beauty of earth. It’s full of flowing water and fertile furrows, hills decked out with fresh grass, meadows and uplands that shimmer with beauty, and, to many people, are evidence of the miracle of divine creation. Parallelism is everywhere in this terrific little poem. The second to last line introduces personification: “The pastures of the wilderness overflow, / the hills gird themselves with joy.” The final line takes this personification and adds not one but two parallel clauses: “the meadows clothe themselves with flocks, / the valleys deck themselves with grain, / they shout and sing together for joy.” The piling on of parallel clauses in this final line is appropriate to the poem’s theme – it’s about the plentitude of divine creation, so why not include one final, personification-rich line of poetry to celebrate the abundance of divinely-created Earth?

So Psalm 65, our example of a praise psalm, chooses for its subject the miraculous splendor of the natural world. Of the 150 Psalms in the Book of Psalms, around 40 are “Praise Psalms” like the one you just heard. To editorialize for a moment, they are quite a nice surprise when you reach them in a Christian Old Testament, if you’re moving forward through the book from beginning to end. With the exception of the Book of Ruth, some parts of Esther, and a few verses here and there, the tenor of the Pentateuch, Historical Books, and Job up to the Book of Psalms is often quite grim, with its long story of the Israelites seesawing between devoutness and blasphemy, and the often tragic narrative of the foreign invasions and internal strife that led up to the Babylonian Captivity from 586-539 BCE. After all of this, when you reach the more celebratory or content poems in the Book of Psalms, it’s quite a breath of fresh air. Let’s move on. We’ve seen a royal psalm – a psalm purportedly by King David, and just now a praise psalm expressing gratitude in regards to the miracle of nature. What’s next? Let’s see. Reading Psalms Takes Lots of Work. Next up is T – Thanksgiving. And I have another great one picked out for Thanksgiving. [music]

Psalm 23: A Thanksgiving Psalm

For our Thanksgiving Psalm, we will use three stanzas that are rather well known throughout much of the planet Earth. If you had to take a guess, as to what the most famous, most highly circulated, commonly memorized lines in Psalms are, and perhaps in the entire Bible, what would your guess be? Of course it’s debatable, but I’d put my money on one in particular. One that involves [sheep] a certain metaphor that’s very common in the Bible.The LORD is my shepherd, I shall not want.

He makes me lie down in green pastures;

he leads me beside still waters;

he restores my soul.

He leads me in right paths

for his name’s sake.

Even though I walk through the darkest valley,

I fear no evil;

for you are with me;

your rod and your staff –

they comfort me.

You prepare a table before me

in the presence of my enemies;

you anoint my head with oil;

my cup overflows.

Surely goodness and mercy shall follow me

all the days of my life,

and I shall dwell in the house of the LORD

my whole life long. (PS 23:1-6)

Psalm 23, one of the most, and possibly the most well circulated poem in human history, communicates a message of humbleness, trust and hope. Its first stanza is addressed to the public, and then the second two, with their increasing sense of gratitude, are addressed directly to the Old Testament God.

To look a little closer at Psalm 23, first, of course, Psalm 23 uses the Bible’s magic trick – that parallel structure in which pairs of lines reinforce, develop, underscore, and sometimes complicate one another. What we’ve learned about parallelism so far in this program is mainly that it recapitulates and underscores. Let’s consider an example of just that in Psalm 23. The line “you anoint my head with oil; [parallel] my cup overflows” can be understood as a paraphrastic line – the image of the overflowing cup emphasizes just how much oil has anointed the speaker’s head, driving home a single idea – God’s blessings, in this case symbolized by oil, are bounteous. But some parallelism in the Bible doesn’t simply recap or rephrase in this fashion. Some parallelism in the Bible works by means of antithesis, or opposing parallel clauses.

We can find an example of antithetical parallelism in line 5 of the Bible’s most famous poem. This is “You prepare a table for me [parallel] in the presence of my enemies.” We might expect something like “You prepare a table for me [parallel] rich with bread and honey.” Instead, Psalm 23’s author goes in a striking and antithetical direction. In the line “You prepare a table for me [parallel] in the presence of my enemies,” the poem employs an unexpected contrast between a divinely laid table and the presence of adversaries. It is a contrast in line with an earlier image in the poem – walking through a dark valley accompanied by God. But the parallel structure of just line 5 in Psalm 23 – the one about a table in the presence of enemies – is an efficient summation of the whole poem’s theme – the world is big and scary, but beneath the care of God, the speaker feels safe.

Whether parallelism is recapitulating or complicating ideas within a line of Biblical poetry, it is the characterizing device of the Hebrew verse that we find in the Tanakh. There are hundreds and hundreds of literary devices. When I was in college, the freshman English major’s backpack often had M.H. Abrams’ A Glossary of Literary Terms in it, a huge index of literary terms, from the basic stuff like metaphors, down to absurdly specialized nomenclature related to specific kinds of poems. If I had to lift parallelism out of that book – the sort of parallelism that we see in Psalm 23 and more generally Ancient Hebrew poetry, I would say that parallelism has a sort of relentless clarity to it. It’s hard to get lost when every clause is reiterated in some way; indeed, repetition tends to drive home points very effectively; once more, in case you missed those first two points, restating something makes it exceedingly clear.

But part of the beauty of Biblical poetry is of course those graceful, subtle differences and developments between parallels in individual lines. If all parallel lines ever did was repeat ideas using near synonyms, the Psalms wouldn’t be as beautiful as they are. For instance, “The Lord is my shepherd, I shall not want [parallel]. He makes me lie down in green pastures” – this line doesn’t simply echo itself. The first part of the line, “The lord is my shepherd, I shall not want,” introduces the common metaphor of God as a shepherd, and then offers a message of contentment. The parallel that follows, “He makes me lie down in green pastures,” develops the first part of the line, showing us the speaker resting, like a sheep, in a verdant meadow. The parallel structure of Ancient Hebrew poetry is always doing things like this – here is a striking clause, and here is a clause that follows it closely, sometimes simply repeating it, but just as often developing it in thousands of creative ways.

So far, we’ve mainly been talking about the formal structure of Psalm 23. Let’s switch lanes for a moment and talk about the history behind it. Biblical poetry, as most of us know, has a huge store of images of sheep and shepherds. Ezekiel 34, Psalm 95, John 10 and Luke 15 are some other famous moments. The word “pastor” comes from the Latin word for “shepherd,” and metaphors of priests and congregations as herdsmen and flocks have been a part of Judaism, and after it Christianity, since time immemorial. We know from past episodes that modern archaeology identifies the Judaean Mountains, with an epicenter on the town of Shilo, as the probable origin point of the earliest Israelites, who, even during the Late Bronze Age, were herding animals. Needless to say, as human beings, we make our metaphors with shared experiences close at hand, and so in some ways the poem’s central metaphor of shepherds and sheep was an easily understandable way to depict the relationship between the Old Testament God and his subjects.

But let’s go a little deeper than this – a little deeper into the history behind, and later interpretation of Psalm 23. “Shepherd,” in the ancient world, was a common term used to describe a king – in particular, a king who had obligations to take care of and look out for his people. The opening line of Psalm 23, then, which begins with “The Lord is my shepherd,” is a bit more striking of a statement than many modern readers might realize. As scholar Walter Brueggemann puts it, “It is likely that [Psalm 23] is not idyllic and romantic as is often interpreted; rather, the psalmist speaks out of a context of deep danger and articulates confidence in [the Old Testament God] as the one who will keep the flock safe and protected in the face of every danger.”12 Psalm 23, then, might have been a bit more politically charged to its original readers than it seems to us today. We hear it and perhaps picture a timeless, pastoral landscape of livestock and a divine caretaker. But its original audience, who heard it as a Psalm of David, may have heard different connotations – namely, that David, or any Israelite monarch, was subject to the deity, just as they were subject to the monarchs who were David’s successors.

To stay on Psalm 23 for just a little while longer, most readers, when they read the words “The Lord is my shepherd,” etc., hear a message of comfort. But a few outliers have had a different interpretation. John Calvin, who can often be counted on for unique interpretations of Biblical books, was interested in the implicit leadership structure of Psalm 23. He wrote that the sheep in the poem were people “who willingly abide in his sheepfold and surrender themselves to be governed by him.”13 John Calvin was not, in other words, merely transported by the poem’s message of comfort. He was also concerned with the degree of surrender and faith required of the poem’s sheep. God, after all “makes me lie down in green pastures. . .for his name’s sake,” making use of a rod and a staff to compel his flock to do his bidding. In Calvin’s mind, the poem’s sheep, or monarchical or divine subjects, had to suspend any skepticism or apprehensions toward their king, or God, and trust in his leadership and good intentions, and this was a substantial leap of faith. If we understand the shepherd in Psalm 23 to have associations with a king as well as a deity, as ancient Hebrew listeners would have, and as Calvin perhaps did, the sheep’s ready surrender to the shepherd’s whims can be just a bit troubling.

That interpretation, however, is obviously an idiosyncratic one. For most readers, Psalm 23 offers a promise of relief and safety in a big, scary world. Before, during, and after the Babylonian Captivity, the ancient Israelites were a minority in a territory of transitioning superpowers, a population that, whether they wanted them or not, had enemies, and were ruled over by a lot of kings, many of whom cared very little about their wellbeing. It’s little wonder that the most famous poem that they produced mentions these enemies, and a “darkest valley,” and a deity that kept them together through war, siege and diaspora, regardless of whoever was wearing the crown at any given moment.

So that was an example of a “Thanksgiving Psalm.” Of the 150 Psalms, about twenty of them are “Thanksgiving Psalms.” We’re most of the way through for this show, or perhaps “psalmost” to through the main portion of it. To return to our mnemonic device, “Reading Psalms Takes Lots of Work,” we’re now on “L,” or Lamentation Psalms. Let’s take a look at one of these. [music]

Psalm 88: A Lamentation Psalm

So far, we’ve seen a really happy Psalm. Psalm 65 looked at the miracles of nature and marveled at the manifold beauties of God’s creation. And we’ve seen a serene and faithful Psalm – the shepherd Psalm, with its still waters and dwelling in the house of the Lord. Now it’s time for something completely different. We’re going to reach deep down into the barrel of Psalms, past the happy ones, past the trusting ones, through the sagacious ones that offer advice. We’re going to reach way down in there to the bottom of the barrel, among the rust and grime, and pull out the very darkest, angriest poem in the whole Book of Psalms. This will be Psalm 88.Psalm 88 is, essentially, an expression of horror and anger at prayers never having been answered. Almost all of the Lamentation Psalms feature a speaker expressing sadness and loss, and then, in a dramatic turn of narrative, finding some kind of a reprieve from God. The speaker of Psalm 88, though, finds no such thing. There is only silence from God, and continued horror. If the parallelism of Psalm 23 communicates serenity and hope, the parallel structure in Psalm 88 conveys a sense of growing, inescapable anguish. Here are some excerpts from Psalm 88, our Lamentation Psalm. [music]

You have put me in the depths of the Pit,

in the regions dark and deep.

Your wrath lies heavy upon me,

and you overwhelm me with all your waves.

You have caused my companions to shun me;

you have made me a thing of horror to them.

I am shut in so that I cannot escape;

my eye grows dim through sorrow.

Every day I call on you, O LORD;

I spread out my hands to you. . .

O LORD, why do you cast me off?

Why do you hide your face from me?. . .

Wretched and close to death from my youth up,

I suffer your terrors; I am desperate.

Your wrath has swept over me. . .

You have caused friend and neighbor to shun me;

my companions are in darkness. (PS 88:6-9,14,16,18)

I skipped over some of Psalm 88, there, but that’s the basic message. The speaker is broken, isolated, and suffering. The speaker gets nothing in the way of consolation from God. The last word of the poem is, appropriately, “darkness.” There is no turnabout – no “I was suffering in a dark place but then, wonder of wonders, I found the healing light of God.” There’s just pain. Granted, Psalm 88 is especially dark within Ancient Hebrew poetry, but that’s one of the things that makes it so remarkable.

If you caught the previous episode on the Book of Job, then the message of Psalm 88 is maybe familiar. Sometimes, life is horrible. Sometimes it’s not green pastures and singing fields of grain and daybreak ringing with the glory of God. Critics have tried – with some success – to read an alternate message into Psalm 88.14 But the sheer amount of anger, and isolation, and pain at divine rejection in the poem is impossible to ignore. Psalm 88 thus reflects the same problem of evil we see in the Book of Job – in other words the question of why bad things happen to good, innocent people, and its answer is little different. The speaker of the darkest of all the Psalms, just like Job, lives in a world in which prayers aren’t answered, and undeserved suffering is everywhere. It is not a comforting message. But what it lacks in gentle consolation, it makes up for in gritty realism. If nothing else, when you’re having a bad day, or month, or year, and you look into the grimness of Psalm 88, you at least know that somebody before you experienced something similar. And I think that can help a lot.

While Psalm 88 is an especially dark lamentation, the sheer volume of Lamentation Psalms in the Book of Psalms shows that the religion practiced in the Jerusalem Temple wasn’t exactly a happy-go-lucky, clap-your-hands-and-feel-the-holy-spirit sort of religion. In all, nearly 70 of the 150 Psalms, or nearly half of the whole collection, are lamentations. That’s a lot of lamenting. [music]

Psalm 133: A Wisdom Psalm

Now, our very last Psalm for the show. We have learned, over the course of today’s show, that “Reading Psalms Takes Lots of Work,” and we’re now on W. This would be a Wisdom Psalm, or a psalm concerned with articulating some kind of truism – often a secular truism. The Wisdom Psalms are like little packets of practical counsel, mixed in with songs of praise, thanksgiving, and lamentation. Because we’ve already covered a lot of territory here, I’d like to do a short one. That short one will be Psalm 133.Psalm 133 is part of a well-known sequence called the Song of Ascents, a group of Psalms that were probably sung together by pilgrims climbing the road to Jerusalem, or singers going up the steps at the front of the Jerusalem Temple. It’s a sustained reflection on the importance of family sticking together, likening the blessing of family to the blessing of God on Jerusalem and the worshippers there. It’s not a complicated Psalm – its three verses simply say, “How very good and pleasant it is when kindred live together in unity!” and then compare this unity to anointment with oil, and then dew on the mountains around the city of Jerusalem. Let’s hear Psalm 133 – the King James version, just to get a little different flavor. This is a nice one to wrap up the main section of the show, in a podcast that’s meant for everyone.

Behold, how good and how pleasant it is

for brethren to dwell together in unity!

It is like the precious ointment upon the head,

that ran down upon the beard,

even Aaron’s beard:

that went down to the skirts of his garments;

As the dew of Hermon,

and as the dew that descended upon the mountains of Zion:

For there the LORD commanded the blessing,

even life for evermore. (Ps 133 1-3)

Togetherness, this Psalm emphasizes, is as beautiful as the luxuries of human civilization, like being anointed with oil. And familial togetherness is, even more profoundly, as sacred as dew on the slopes of holy mountains. The poem, short as it is, is once again an example of a wisdom psalm – one which communicates or proposes some general truism pertinent to life in ancient Israel. Of the 150 Psalms, around a dozen are categorizable as “Wisdom Psalms,” like Psalm 133.

Lowth’s Hypothesis of Parallelism and Dual Choirs

So now you know the basics of the Book of Psalms – that it’s an anthology of 150 short poems, written with parallel lines, and roughly divisible into royal, praise, thanksgiving, lamentation and wisdom psalms. The approach that I took in presenting the Psalms – namely category by category, isn’t an exact science. The names of the categories used by different scholars vary greatly, as do the way that certain Psalms get classified. But whatever the exact categories you use, and however you classify individual Psalms, I think that placing them into some sort of groups is an indispensable tool to understanding how they function.Talking about the way the Psalms function structurally is a relatively new trend. Robert Lowth, the Bishop of Oxford, England from 1766-1777, was the first scholar to recognize the pervasiveness and consistency of parallelism in Ancient Hebrew poetry. His book Lectures on the Sacred Poetry of the Hebrews, first published in English in 1787, contained the first extensive analysis of the parallelism pervasive throughout the Psalms. Lowth’s hypothesis is fascinating. He proposed that during Temple services, “one of the choirs sung a single verse to the other, while the other constantly added a verse in some respect correspondent to the former. . . And this mode of composition being admirably adapted to the musical notation of that kind of poetry, which was most in use among them from the very beginning, and at the same time being perfectly agreeable to the genius and cadence of the language. . .[Overall,] among the Hebrews almost every poem possesses a sort of responsive form. . .in two lines. . .things for the most part shall answer to things, and words to words, as if fitted to each other by a kind of rule or measure. This parallelism has much variety and many gradations.”15 And just like that, Robert Lowth pinpointed, and proposed a logical, liturgical reason for the Bible’s magic trick, parallelism. Two choirs articulated ideas in pairs, the first reading the opening parallel, and the second undergirding it with further imagery or ideas.

There are occasional notes in the Psalms that suggest performance contexts. A common marginal note is the word Selah, often set at the ends of stanzas and generally interpreted to indicate a pause between them – perhaps for quiet reflection, or perhaps for an instrumental performance. Other marginal notes mark certain poems with the title maskil, perhaps a word describing the instrumentation, melody, or harmony meant to accompany the psalm’s performance. Some are just marked as A Song to indicate that they are to be performed. Others are marked by the note with stringed instruments. Even more head notes to the Psalms than these have long been a part of the Book of Psalms. Their details, in antiquity, would have cued clergymen, singers, musicians, and temple personnel into what sort of musical accompaniment and melodies to expect.

We are hard pressed, today, to understand the actual performance context of the Psalms, even with all of the original headnotes that survive. But Robert Lowth’s hypothesis – that the Psalms were likely performed by pairs of speakers, has stood the test of time decently over the past two centuries. So let’s go back to Psalm 19 and hear what its parallel lines might have sounded like, performed by two different choirs and accompanied by stringed instruments. It would sound something like this: [stereo recording with music]

The heavens are telling the glory of God;

and the firmament proclaims his handiwork.

Day to day pours forth speech,

and night to night declares knowledge.

There is no speech, nor are there words;

their voice is not heard;

yet their voice goes out through all the earth,

and their words to the end of the world. (PS 19:1-4)

This – singing or chanting parallels by two different groups – may very well may be how the Psalms worked 2,500 years ago at a basic level. If I knew Biblical Hebrew well and were trained as a cantor, you can bet I would have I would have put those skills to use just then. But speaking of cantors, synagogues, choirs and churches, in many modern places of worship today, the Psalms and other portions of the Bible are sung in pairs of choirs, or read in a sort of call and response form with someone from the clergy reading one parallel line, and then the audience reading the responding one. It is a hypnotic thing to observe and participate in, bringing a choir and/or congregation together in tandem to actually sing or chant Biblical poetry. The unfolding structure of parallelism, in a live setting like this, makes it such that the two halves of the audience are actually in dialogue with one another, a dialogue that’s been a continuous part of worship services for a long time, and has kept the Psalms alive and breathing all the while.

It is impossible to exaggerate the overall influence of the Bible’s 150 Psalms on Anglophone, and more broadly world literature. I am personally averse to looking for the origins of things in antiquity. Anyone who tells you that monotheism was born in Judah, or Akhenaten’s Amarna, or anywhere else, is taking a wild gamble. We don’t really know where monotheism came from. Likewise, when Ancient Greece, as it so often does, gets extolled as the wellspring of civilization, those who identify it as such have to ignore the two thousand years of recorded history that came along before it. When Socrates gets lauded as the father of philosophy, those who claim him as such ignore the immediate prehistory of Greek thinkers who came along before him, and the greater intellectual traditions of Ancient Egypt and the Ancient Near East that preceded him, too. When we reach something like the Psalms – something so transcendently important to literary and cultural history, there is a temptation to view them as an instantiating moment. Here, we are tempted to say, is the very juncture that lyric poetry’s steam engine got started – the very moment that short poetry began to have a known public role, a role that has never let up or stopped since. It’s impossible to make this claim, though. Millions of Bronze Age urbanites lived and held ceremonies and public gatherings long before the lyric poetry of Greece and Rome, and it’s difficult to imagine that in ancient Thebes, Memphis, Avaris, Babylon, Nineveh, Ugarit, Hattusa, Ur, and Uruk didn’t also have performances centered on lyrics set to music, as well. The Bull Headed Lyre of the City of Ur, dated to about 2,500 BCE and uncovered in 1926 during the Royal Cemetery of Ur excavations, has a strip of illustrations along its soundbox, suggesting that even back during the Middle Bronze Age, musicians told stories with words while accompanying themselves with instruments, and I think this has probably been the case since we were sitting around campfires, thumping bones onto logs, and singing songs together.

The Psalms, the Qur’an, and Liturgical Poetry

However, the Psalms, while very likely not the first body of poetry consecrated for use in liturgy, have proved unique in their freshness and their staying power. They have, in fact, had such a remarkably successful track record as a collection that they are even mentioned in the Qur’an. Sura 17 of the Qur’an contains the following words from God to the Prophet Muhammad: “Your Lord knows best about everyone in the heavens and the earth. We gave some prophets more than others: We gave David a book [of Psalms].”16 In context, in a sura whose title gets translated as “The Night Journey,” God is telling Muhammad that he lifts people up and pushes them back down as he sees fit, prophets included. Elsewhere, God tells Muhammad “We wrote. . .the Psalms, as we did. . .[earlier] Scripture” (21:105).17 The Qur’an, as you may know, mentions many Biblical figures and stories, including, frequently, Abraham, Moses, Noah, and Jesus, considering all of them prophetic predecessors to Muhammad. It is thus not too surprising, when you reach Sura 17, to hear a reference to King David, or his Psalms. Muhammad, educated as he was, as well as many early Muslims, knew about the Psalms, what they said, and how they were used in Jewish and Christian worship communities during Late Antiquity.It is thus little surprise that some of the most beautiful passages in the Qur’an have similar sentiments to what we find in the Psalms. Earlier in this program, we read most of a praise Psalm. This was Psalm 65. After Psalm 65 describes how God quiets the roaring of waves and tumult of civilization, the Psalm celebrates the miracles of nature. God, Psalm 65 tells us, brings rain and ripe fields of grain, washes away the hard ridges of the summer, brings lush grass to the hills, and causes the landscape to sing with happiness. Similar sentiments propel some beautiful lines in the Qur’an’s second Sura, in which God says, “In the creation of the heavens and the earth. . .in the water which God sends down from the sky to give life to earth when it has been barren, scattering all kinds of creatures over it; in the changing of the winds and clouds that run their appointed courses between the sky and earth: there are signs in all of these for those who use their minds” (2:156).18 Setting aside generalizations about the long and complex history of the Abrahamic religions, we can simply say, here, that it’s wonderful that one of the most beloved Psalms, and one of the most beloved Suras both pause to marvel at the miraculous fecundity of the natural world.

The Psalms, while they were probably not the first liturgical works in verse, and while they likely do not mark the invention of parallelism as a literary device, are still the most widely read poems in human history. They have, over the many years that they’ve been studied, generally been subdivided into different categories like the ones that we explored today – Royal psalms, associated with David, and then Praise, Thanksgiving, Lamentation, and Wisdom. And while parallelism as a literary device likely goes back to the Paleolithic, in the Psalms, parallelism is put to work with ingenuity, clarity, variety, and great beauty. Parallelism, the Bible’s magic trick, is the dynamo that powers Biblical poetry, perhaps born of an oral culture in which repetition helped lasso in those of varying linguistic and cultural backgrounds, by adding them added clarity. In congregation settings, poetic parallelism, since the Iron Age, has been engaging and interactive, inviting the audience to be a part of a service and blurring the boundaries between clergy and laity as all collaborate to sing, and to recite. The authors who set down the Psalms were ultimately some of history’s most successful poets, their lines continuously on thousands of lips for centuries and centuries after they lived. We might today read the Psalms alone, but when they were born, they were the product of a living, and public theology – one in which sacrifices and singing; sacred rites and holidays; and spectacles and recitations were all coming to life, psalm by psalm, parallel by parallel, line by line, and word by word. [music]

Moving on to Ecclesiastes

In the next show, we’re going to talk about the Book of Ecclesiastes, or the Book of the Gatherer, or Teacher. As we’ve moved through these books of the Old Testament in recent episodes, I seem to again and again emphasizing the importance of this book, or that chapter, or this verse. Covering the Tanakh is a bit like hiking the Himalayas – everything within sight is larger than life – every single mountain has cast shadows that endured for eons, and the elevation of it all makes one feel a bit lightheaded. And while Psalms, and Job, and before them the Historical Books and the Pentateuch, are all towering Everests and K2s in the history of human culture, the Book of Ecclesiastes, especially in literary history, looms just as large.Ecclesiastes is another rather unique book in the Bible. Its quiet resignation and its unflinching realism have endured it to generations of readers and writers. So while in the Book of Psalms we have a nice broad catalog of poems for every occasion – sad or happy, the Book of Ecclesiastes is one text that works for any occasion. In just twelve chapters, it covers nearly the whole scope of human experience. Thanks for listening to Literature and History. There’s a quiz on this program in the Details section of your podcasting app if you want to review what you learned, along with the usual full, illustrated episode transcription. If you stay on for the songs, I have one about Psalms. If not, thanks for stopping by.

Alright, still here? So I got to thinking. Having read all these Psalms in conjunction I’m often struck at the alternations in tone between them. This one is calm and unperturbed, the next one distraught and angry, the next one ebullient and optimistic, and on and on. I couldn’t get the association out of my head that the Psalms are kind of like a radio station – a sort of Ancient Hebrew FM. And so I wrote the following song, which is sort of like a concept song, in which various kinds of psalms – Royal, Praise, Lamentation, and Thanksgiving, appear as classical, gospel, blues, alt rock, and that kind of thing, along with interspersed advertisements. It is a very silly exercise in imagining what a radio station might have sounded like if a radio station had existed near the city of Jerusalem in about 490 BCE. I hope it makes you laugh, and I’ll see you next time, with the Book of Ecclesiastes.

References

1.^ Printed in The New Oxford Annotated Bible. Ed. Michael Coogan et. al. Oxford University Press, 2010, p. 878. Further references to this text will be quoted with chapter and verse in this episode transcription.

2.^ Luther, Martin. “Preface to the Psalter.” Printed in Luther, Martin. Luther’s Works. Trans. C.M. Jacobs and Rev. E.T. Bachman. Muhlenberg, 1960, p. 254.

3.^ The Psalms: A Form-Critical Introduction was published 1926, and An Introduction to the Psalms in 1933, after Gunkel’s death in 1932.

4.^ Augustine. Enarrations on the Psalms (CL). Delphi Collected Works of Saint Augustine. Delphi Classics, 2016. Kindle Edition, Location 129718.

5.^ See Wilson, Gerald. The Editing of the Hebrew Psalter. Society of Biblical Literature, 1985.

6.^ See Brueggemann, W. “Bounded by Obedience and Praise: The Psalms as Canon.” JSOT 50:63–92.

7.^ See Mitchell, David C. The Message of the Psalter. JSOT Series, 1997.

8.^ Brueggemann, Walter; Bellinger, Jr, W. H. Psalms. Cambridge University Press, 2014. Kindle Edition, Location 2942.

9.^ Coogan, Michael, et. al., eds. The New Oxford Annotated Bible. Oxford University Press, 2010, p. 788.

2.^ Luther, Martin. “Preface to the Psalter.” Printed in Luther, Martin. Luther’s Works. Trans. C.M. Jacobs and Rev. E.T. Bachman. Muhlenberg, 1960, p. 254.

3.^ The Psalms: A Form-Critical Introduction was published 1926, and An Introduction to the Psalms in 1933, after Gunkel’s death in 1932.

4.^ Augustine. Enarrations on the Psalms (CL). Delphi Collected Works of Saint Augustine. Delphi Classics, 2016. Kindle Edition, Location 129718.

5.^ See Wilson, Gerald. The Editing of the Hebrew Psalter. Society of Biblical Literature, 1985.

6.^ See Brueggemann, W. “Bounded by Obedience and Praise: The Psalms as Canon.” JSOT 50:63–92.

7.^ See Mitchell, David C. The Message of the Psalter. JSOT Series, 1997.

8.^ Brueggemann, Walter; Bellinger, Jr, W. H. Psalms. Cambridge University Press, 2014. Kindle Edition, Location 2942.

9.^ Coogan, Michael, et. al., eds. The New Oxford Annotated Bible. Oxford University Press, 2010, p. 788.

10.^ Lewis, C.S. Reflections on the Psalms. New York: Harcourt, 1958, p. 63.

11.^ Brueggemann and Bellinger (2014), Location 3007.

12.^ Brueggemann and Bellinger (2014), Locations 3503-6.

13.^ Calvin, John. Commentary on the Book of Psalms, vol. 1. Baker, 1979, p. 392.

14.^ See Terrein, Samuel. The Psalms: Strophic Structure and Theological Commentary. Erdmans, 2003, p. 628.

15.^ Lowth, Robert, DD. Lectures on the Sacred Poetry of the Hebrews. Translated by G. Gregory, P.A.S. Crocker and Brewster: Boston, 1829, pp. 155-7.

16.^ Haleem, M.A.S. Abdel, trans. The Qur’an. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 2010, p. 178. See also 4:163.

17.^ Ibid, p. 208.

18.^ Ibid, p. 18.

11.^ Brueggemann and Bellinger (2014), Location 3007.

12.^ Brueggemann and Bellinger (2014), Locations 3503-6.

13.^ Calvin, John. Commentary on the Book of Psalms, vol. 1. Baker, 1979, p. 392.

14.^ See Terrein, Samuel. The Psalms: Strophic Structure and Theological Commentary. Erdmans, 2003, p. 628.

15.^ Lowth, Robert, DD. Lectures on the Sacred Poetry of the Hebrews. Translated by G. Gregory, P.A.S. Crocker and Brewster: Boston, 1829, pp. 155-7.

16.^ Haleem, M.A.S. Abdel, trans. The Qur’an. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 2010, p. 178. See also 4:163.

17.^ Ibid, p. 208.

18.^ Ibid, p. 18.