Episode 27: The Bloody King

Aeschylus’ Oresteian Trilogy, 1 of 3: Agamemnon. A terrible family curse. A wronged queen. The Trojan War was only the start of the bloodshed.

| Read Transcription | References and Notes |

| Episode Quiz | Episode Song |

| Episode on Spotify | Episode on Apple Podcasts |

| Previous Show | Next Show |

What is the Oresteia?

Hello, and welcome to Literature and History. Episode 27: The Bloody King. This program covers the play Agamemnon, a tragedy by the ancient Greek dramatist Aeschylus, first staged in the city of Athens in the spring 458 BCE. Agamemnon is the first play in a sequence of three tragedies that scholars call the Oresteian trilogy, or the Oresteia. The Oresteia is the only trilogy of plays that’s survived from ancient Greece in full. As we learned last time, theater festivals during the classical period generally required tragedians who competed to submit three tragedies, along with a comedy, in order to participate. While we have a lot of plays from classical Athens, the Oresteian trilogy, because all three of its original plays survive, is the longest onstage story that’s come down to us from ancient Greece. If you were taking a college class on ancient Greek literature, it would very likely include the Oresteia.In total, about 44 plays have survived from classical Greece. They were all, with the possible exception of one, written by four dramatists, and these 44 plays were staged between about 480 and 380 BCE.1 The earliest of classical Greece’s four dramatists is our writer for today, again Aeschylus. While the three plays in the Oresteia aren’t quite the oldest of ancient Athens’ surviving plays, the Oresteia is still a great welcome mat to ancient Greek theater. Its story connects directly to the Homeric epics, which we’ve read in our show, featuring some characters we’ve already met.

The Oresteian trilogy – not just our play for today, Agamemnon, but the entire Oresteian trilogy, is, at its core, about revenge. Revenge, in stories, is an accelerant. It gets characters moving. Revenge drives gravelly-voiced soliloquies onstage or in voiceovers behind the camera. Revenge turns underdogs into combatants, and it lets audiences rise alongside protagonists who have been underestimated and downtrodden. But revenge stories are also problematic. They often involve outsized pursuits of retribution. The cowboy in the white hat might take down the gang of cowboys in black hats, but not all of the bad cowboys are really that bad, and they have families and friends, and when the black hat cowboys’ families and friends start going after the white hat cowboy, before long, all of the hats are gray and it’s just a long and meaningless sequence of murders. Ancient Greeks knew this, just as we do, today. Cycles of revenge were, in scholar M.N. Nagler’s words, “the most dangerous source of disorder in prelegal societies.”2 When Aeschylus staged the Oresteian trilogy in 458 BCE, Athenian democracy was developing out of an earlier world of fiefdoms and blood feuds, and into a more advanced world of commerce-driven empires. The Oresteia is the story of a civilization moving from feudalism to law and order, and thus, although it’s a very dark and bloody tale at times, it ends on a high note.

The full story of the Orestian trilogy will take us three full episodes. Its first play, which again we’re covering today, is Agamemnon, and Agamemnon tells the story of how the king who won the Trojan War came home from Troy. Its main character is King Agamemnon, the overlord of the Greek forces in Homer’s Iliad. After Agamemnon in the Oresteia is a second play, called the Libation Bearers. In the Libation Bearers, we meet Agamemnon’s son, Orestes, from whom the Oresteia gets its name. The second play in the triptych is about an awful crime that young Orestes commits, and then the third play, the Eumenides, is about the ramifications of the crime of Orestes, son of Agamemnon.

In the trilogy that we will explore over the next few episodes, there will blood, atrocities, and a family inclined to murder, generation after dreadful generation. Agamemnon, his wife Clytemnestra, and their son Orestes are magnetic figures, but not, perhaps, the kinds of people you’d want to sit next to on a long plane ride. But as intense as Agamemnon and his family can be, and as grim as the Oresteia gets at times, Aeschylus’ most famous story is, again, ultimately about civilizational progress, and at its end, there is hope – the best kind of hope in literature, too – the kind that looks into the very worst of human experiences and attests that if we work together – if we are organized, attentive, and fair, we can and will make things better for ourselves, and for those who come after us. Ladies, gentlemen, nymphs, satyrs, get ready for one of the biggest blockbusters of ancient Greek theater, the Oresteia, beginning with Part 1: Agamemnon. [music]

Revenge in the Homeric Epics

The Odyssey closes Odysseus’ murder of over 100 suitors, and then Athena intervening briefly to stop a war between Odysseus and the bereaved suitors’ families. Athena, though she forestalls a new bloodbath, has not given us any sense that she cares about peace or stability, and the Homeric epics with a bleak view of human history. Aeschylus, on the other hand, had a more progressive and optimistic view of humanity. The painting is Ulysse et Télémaque massacrent les prétendants de Pénélope by Thomas Degeorge (1812). Photo by VladoubidoOo.

Some ancient readers wished that the Odyssey ended with Odysseus and Penelope flying into each other’s arms after the killing of the suitors.3 But, the story grinds on. Odysseus had killed more than a hundred young men, many of whom begged for their lives. The slain suitors’ families came to Odysseus’ palace, seeking retribution and asking questions. Didn’t the suitors have a right to court the absent king’s wife? they asked. Odysseus had been gone for almost twenty years, after all. There had, admittedly, been a slight to his honor, but killing all hundred suitors – even ones who had begged for their lives? Killing the women, who’d merely been trying to survive with the changing times? In the final book of the Odyssey, voicing these objections to the magnitude of Odysseus’ vengeance, the families of the suitors also recollected that twenty years earlier, Odysseus had also carried off the youths of Ithaca to fight the Trojan War, and none had returned but him! And now this butchery in the palace?

Things at the end of the Odyssey grew even worse. The families of the suitors confronted Odysseus in a rural spot near a cottage. Odysseus stood next to his father and son, some slaves, and two loyal herdsman, and prepared for more indiscriminate homicide. But at the last minute, Athena intervened, telling everyone to lay down their weapons. What survives in the Odyssey, as we saw back in Episode 14, is an awkward, disquieting ending. Whatever peace the goddess has brokered may or may not last. Odysseus, by his story’s end, has become as villainous and hubristic as any character in Homer. The poor families of the murdered men and women of Ithaca, in contrast, seem justified in their desire for payback. What will follow will be revenge against the vengeful Odysseus, and then revenge against that revenge, and revenge against that revenge, and more revenge, for generations, with cadenced breaks for each new cohort to grow and reach maturity. Thirteen episodes ago, we saw how this ending, however unsettling it is to us, is nonetheless consistent with the Homeric worldview. To Homer, there is no ultimate forward progress toward betterment. There is only an endless rhythmic cycle of war and peace, and war and peace, and humanity is caught in it. It is a beautiful cycle, filled with each generation’s new hope and heroism, courage and cunning all around, but it’s also a cycle that devours everyone and leaves nothing behind except legends – legends which, as the Homeric Achilles tells us from Hades, do no good for the dead.

Homer’s worldview is captivating in its ruthlessness. It fit the cusp between the Greek Dark Age and the Greek Archaic Age. By that spring day in 458 BCE, when you and I went to the theater in Athens in the previous show, generations of Greeks from all over the Aegean had heard, read, and recited Homer. But also by this spring day in 458 BCE – again the day that Aeschylus’ Oresteia premiered, historical events had taken place that had begun to suggest that life might unfold in a way more meaningful than ungovernable sequences of carnage and recuperation, and carnage and recuperation.

We’ll learn more about Aeschylus, and the early history of classical Athens, toward the end of this show. However, before we get into Aeschylus’ biography, and the historical context of the Oresteia, I think you need to hear the story. Let’s start with some background.

The Homeric epics were set down some time from roughly between 725-625 BCE, and they concerned a much earlier period of history – the Bronze Age Mycenaean world of 1200 or 1100 BCE or so. The Homeric epics were oral story cycles that eventually, as writing and phonetic alphabets became popular in the Greek speaking world, were set down through some sort of collaboration between oral storytellers and scribes. Contemporary to the Homeric epics, the poems of Hesiod were also set down. Homer and Hesiod, together, were the root ball and trunk of ancient Greek literature, and later, ancient Roman literature. Homer and Hesiod told gigantic stories with hundreds of proper names and named places, and for centuries, later writers used their characters in spin-off tales and reboots. Many of these spin-off tales – ones that survive at least – were set down during the 400s BCE. From the root ball and trunk of Homer and Hesiod, during the 400s, there grew many different branching storylines concerning Odysseus and his contemporaries. Ancient Athenian dramatists like Aeschylus – again our author for today – knew that Homeric characters would fill theater seats, just as Wolverine and Spider Man fill seats today. Aeschylus and later ancient Greek dramatists wrote stories about Homeric characters who survived the Trojan War, imagining what happened to them after the Trojan War. Odysseus, after all, had had a heck of a time getting home. What about Agamemnon? There were legends about him. The Odyssey talked about what had happened to Agamemnon after the Greek king won the war. He was a gigantic figure in ancient Greek literature. But what was the real story behind Agamemnon, and how he’d come home from the Trojan War? [music]

Agamemnon: The Archetypal Autocrat

Agamemnon, in the Homer’s Iliad, is a despot. In the first book of the epic, he steals the champion Achilles’ wife, subsequently losing the allegiance of his most powerful warrior. In the second book of the epic, he plays a cruel trick on the Greek armies, telling them it’s been ten years, and for goodness’ sake they can all go home, and then just kidding, that they have to stay there – he was just testing their loyalty to him. Agamemnon is not a coward. At one point in Homer’s Iliad, he leads a major assault, throwing himself into the center of the fighting. In the Iliad, he’s not without self-consciousness, as he later repents and apologizes for stealing Achilles’ wife. But in the main, Agamemnon is not the most likable Homeric character. An authoritarian, an egomaniac, and the superintendent of ancient literature’s most famous war, Agamemnon isn’t the kind of person you’d want working at a preschool or teaching a yoga class.

A detail from the Taleides Painter’s illustration of Agamemnon intervening in the fight for the body of Patroclus, dated to about 520 BCE.

By the time of the Oresteia’s premiere in 458 BCE, Athenians had very specific reasons to dislike absolute monarchies. Aeschylus himself, a combat veteran, along with thousands of other Athenian democrats, had fought a quarter century long war with a real-life Agamemnon. This Agamemnon had not been from Argos, nor mainland Greece, nor even the eastern Aegean. The autocracy that Aeschylus and his generation fought against was the Achaemenid Persian Empire, and it had multiple Agamemnons – one named Darius, and another called Xerxes, and more besides these. Historically, the kings of Achaemenid Persia were more multidimensional than the fictional Greek character Agamemnon, but to Aeschylus, and his family, and his friends, Darius and Xerxes were despots of an old world – they were self-aggrandizing, swaggering tyrants who built bridges over oceans and carried sumptuous luxury with them even on the battlefield. Aeschylus’ Agamemnon, then, is about a fictional Homeric character. But the play is also, more largely, about all violent, unlovely autocrats, old and new, and the fate that tends to befall them.

So, I’ve introduced two ideas so far here. One of them is that the entire Oresteia is a sequence of plays about revenge – about how it works, the results that it produces, and the steps that humankind can take to move civilization out of generations of tit for tat violence. And the second idea, more prevalent to today’s play, Agamemnon, is that bloody kings, be they Bronze Age swaggerers like Agamemnon or the despotic Persian kings whom Aeschylus fought – that bloody, absolutist monarchies are a relic of the antique past. I think that’s enough upfront information about the overall historical currents in the air when the Oresteia was first staged in 458 BCE at the Theater of Dionysus, just southeast of the Athenian Acropolis. Let’s begin the story of the play Agamemnon. We will start by talking not about Agamemnon, but about his great, great grandfather, a ruler named King Tantalus. [music]

From Tantalus to Agamemnon: The House of Atreus

The lands of Lydia, in the eastern Aegean, were a tumultuous place during the Iron Age. Occupying the western half of Asia Minor, Lydia had no geographical barriers to the east. When the Persians came, it was the first area of the Greek world to fall under the rule of Cyrus the Great. Lydia was thus in the central Aegean imagination a place somewhere between East and West, between civilized and savage, where great cities existed – Sardis, Smyrna, Ephesus, and Troy – but at the same time, where barbaric regimes could invade and usurp entire regions in an eyeblink.

The principal characters in the play Agamemnon, together with their ancestors. Graphic by Ian Johnston.

King Tantalus had a son called Pelops. And in an offering to the Gods, Tantalus chopped this son into pieces, and served the remains of Pelops to the gods. The Olympian pantheon saw what had been served to them, and they responded quickly. The innocent boy, Pelops, was restored, and grew into a beautiful young man. As for Tantalus, his punishment was to stand, in Hades, rooted in a pool of water beneath fruit laden trees. When Tantalus lifted his hands up, the branches lifted the fruits out of reach. When he bent to drink, the water sunk beneath his feet. Tantalus’ punishment, in the darkest layer of Hades, was to endure eternal proximity to food and drink without ever being able to touch it. Odysseus sees Tantalus in the underworld sequence in the Odyssey, which means that the story of Tantalus is roughly contemporary with that of Adam and Eve and their plunder of divine fruit.4 Tantalus is also where we get the word “tantalized.” So that’s what happened to Tantalus, the founding father of what’s called the House of Atreus. Let’s talk about Tantalus’ son, and the second generation of the House of Atreus.

Tantalus’ son Pelops, who had been divinely restored, isn’t the end of the story. Though Zeus at first coddled Pelops, Zeus eventually threw the handsome young man out of Olympus. Pelops, once back on earth, wanted to marry a woman. The woman’s name was Hippodamia. Hippodamia was the daughter of a king called Oenomaus, a king who had been told in a prophecy that he’d be murdered by his son-in-law. Knowing this, the king had killed eighteen suitors who had courted his beautiful and much-coveted daughter Hippodamia, and the king had nailed their heads to the columns of his palace. King Oenomaus had killed them all by inviting them to compete with him in a deadly chariot race – and King Oenomaus always won. Whether in the Odyssey or elsewhere, being a suitor was dangerous business in ancient Greek mythology.

So, one would hope that young Pelops, second figure in the House of Atreus, seeing eighteen heads in various states of decomposition rotting on the pillars of his beloved’s castle, would intuit that he ought to seek out true love elsewhere. I believe that rotting heads on spikes are a fairly universal sign to keep your distance. But let’s not forget. Young Pelops had been dismembered by his father and served as a meal. He probably wasn’t a marvel of psychological stability. And so Pelops accepted the challenge of the chariot race, cheated – either by a miracle from Poseidon, or an extremely dirty trick involving King Oenomaus’ chariot driver – and won. King Oenomaus was dragged to death by his horses.

And so Pelops and Hippodamia were married, and one would hope that they removed the severed heads from around the palace. The victory was a big enough deal that forever after, the giant landmass King Oenomaus had ruled had its name changed to Pelopos nísos, or Pelops’ Island which is where we get the name “Peloponnese” today. Pelops and Hippodamia actually lived long enough to sire three children – the third generation of the House of Atreus. And unfortunately, these poor little apples didn’t fall too far from the crooked, dysfunctional family tree.

There were three sons in the third generation of the House of Atreus – Atreus himself, his brother Thyestes, and their oldest brother Chrysippus. Chrysippus, at an early point, seemed to be the hope for the future. Old Pelops, king of the Peloponnese, believed Chrysippus ought to inherit the throne. Chrysippus, everyone seemed to agree, was the hope for the future. He was strong, and just, and he would lift the kingdom out of ignominy and squalor, this firstborn son, Chrysippus. Unfortunately, the other two sons, Atreus and Thyestes, murdered him. Atreus and Thyestes were thereafter banished from their father Pelops’ kingdom, and their mother committed suicide. The two young men survived this trauma, though, and they grew older, and were wed. Like their father Pelops, both Atreus and Thyestes, the survivors of the third generation of the House of Atreus, each had some sons.

Atreus serving Thyestes the flesh of his children. From a 1410 codice called Des cas des nobles hommes et femmes.

Thyestes, following this horrific ordeal, was forced into exile. As Atreus’ own sons grew, Thyestes sought divine advice. An oracle told Thyestes that he must have sex with his own daughter in order to produce a male heir who would kill Atreus, and avenge the death of poor Thyestes’ sons. Thyestes did just this, and a boy was born named Aegisthus.

And this brings us to the fourth generation of the House of Atreus. Their story so far has involved theft from the gods, murder, infanticide, cannibalism, incest, and adultery, all, seemingly, increasing in quantity from generation to generation. And soon, more murder was added to the list. Thyestes’ son, Aegisthus, did fulfill the prophecy, and he murdered his uncle Atreus. And yet Atreus’ sons didn’t immediately exact revenge on their cousin. Atreus’ sons were actually busy people – people whom you’ve met before. What could these two young men possibly do to top the crimes of their forebears? What could Atreus’ two boys, the fourth generation of the House of Atreus, do that could possibly be any more malevolent than killing children and serving them to their parents? They actually did something far, far worse. Their names were Agamemnon, and Menelaus. And they started the Trojan War.

And so now that you know the history of the House of Atreus, down to Agamemnon. There’s just one more thing to cover before we jump in, and that is this play’s setting. The play Agamemnon is set in the Peloponnesian city of Argos. Argos is about 60 miles southwest of Athens as the crow flies, and it’s close to the center of a fertile plain that extends right out to the Bay of Argos. During antiquity, including the bygone Mycenaean period when ancient Greeks imagined the events of the Trojan War taking place, Argos was always one of Greek civilization’s power centers, and so the return of King Agamemnon to his father Pelops’ Peloponnesian stronghold was the second most famous “homecoming” story in ancient Greek mythology, behind that of Odysseus. So, it’s time to begin the Oresteia. Unless otherwise noted, all quotes in the remainder of this program will come from the Robert Fagles translation, first published by Penguin Books in 1979. [music]

The Oresteia, Part 1: Agamemnon

An autumn night hung over the palace of Atreus, the citadel of King Agamemnon. The lands of Argos, beyond the palace walls, were silent and dark. King Agamemnon had been gone for ten years, and the campaign season for the present year was now finished. Soon, the waters of the Aegean would prove treacherous, and squalls would crush any returning boats. If the king didn’t return soon – if he didn’t complete that perilous 500-mile journey west across the Aegean and back up to Argos, he’d be gone all winter, and spend the better part of another year abroad in Troy.

The archaeological site of Ancient Argos, said to have been the city of Agamemnon. Photograph by Ploync.

No one in Argos knew it yet, but the Greek forces had crushed their Trojan adversaries. A clever ruse had helped them get behind the Trojan fortifications, and once within the city, they had massacred their enemies. Ten years of stalemate, of living in a camp with minimal provisions, living only with other fighters, and slaves and concubines, had affected the Greek forces. They hadn’t seen their families, nor children, nor, moreover, lived in civilized society for a long time. Instead, they’d camped alongside the hulls of their black ships, piled thick on one another like animals in cages. And so when the Greeks had broken into the beautiful city of Troy, they had done terrible things. The massacre in the city had been animalistic, and merciless – the conflagration of ten years of pent-up animosity suddenly released. And at the center of the sack of Troy stood the brothers, Agamemnon and Menelaus, the sons of Atreus. There had been a divine hand in all the events. The meddling of Apollo, Hera, Aphrodite, Athena, and Zeus had prolonged the violence of the war. But insofar as humankind were responsible, the ringleaders of the slaughter that took place in Troy were Agamemnon and Menelaus.Far from Troy, then, on the other side of the Aegean, Agamemnon’s household awaited his return. A watchman stood on a silent rooftop. He was so accustomed to loneliness that it was his habit to talk to himself. As the watchman stood there that night, he waited for any sign – a sign that the war had finally ended, or that the king was returning, or perhaps, for the sight of Trojan ships arriving to make retaliatory war on Argos. The watchman said aloud that he was dog tired, and that he knew the shape of every single star. Nearly falling asleep, he shook himself awake, tried to sing a little, and he wished that the House of Atreus hadn’t fallen into such a poor condition.

The watchman fell into a deeper sadness, but suddenly, he saw light coming from the east. It was a signal fire – the one he’d been waiting for for a decade, a glow that to him seemed brighter the than dawn. Agamemnon, he thought, would finally return. The watchman’s jubilation changed into a more tempered caution. The watchman said, “Just bring him home. . .[A]nd then. . .the rest is silence. . .Aye, but the house and these old stones, give them a voice and what a tale they’d tell. . .[but] I never say a word.”5 The watchman, you see, knew that Agamemnon was coming home. But the watchman also knew some other things that had been going on in Argos – things that had changed in the king’s absence. The watchman, after observing the palace over the past ten years from atop his high perch, knew that mighty King Agamemnon was coming home to a very dangerous situation. [music]

Clytemnestra and the Death of Iphigenia

Agamemnon’s murder of his daughter Iphigenia, minimally told in the Iliad, is an important forerunner story to the Oresteian trilogy. The painting is Le Sacrifice d’Iphigénie by Abel de Pujol (1822-5).

Now, Helen had a sister. Her name was Clytemnestra. And she was married to King Agamemnon. The marriage of these two beautiful sisters – Helen and Clytemnestra, to two powerful brothers – Menelaus and Agamemnon, had seemed both righteous and politically unbreakable. When the easterner Paris had taken Helen, though, the bonds of the double marriage had been violated. And so the signal fires that Troy had been taken indicated to Clytemnestra that her sister had also been recovered by the Atreus brothers. The old men of the chorus watched Queen Clytemnestra light sacrificial fires in the palace, fires that began to share the glow of the rising dawn. The old assembly was puzzled at the sight. What did Queen Clytemnestra know that they didn’t?

The men of the chorus watched Clytemnestra. They knew that she had been “growing strong in the house / with no fear of [her] husband” (108). And the old men of the chorus knew that all was not well between Clytemnestra and Agamemnon. Because ten years before, as he had set out to make war on the city of Troy, Agamemnon had done something terrible. The chorus remembered the circumstances of this awful act a decade ago. As the Greek armies had prepared to go to war, the chorus recalled,

Weatherbound [the Greeks] could not sail,

our stores exhausted, fighting strength hard-pressed,

and the squadrons rode in the shallows. . .

where the riptide crashes, drags,

and winds from the north pinned down our hulls. . .

sheets and the cables snapped

and the men’s minds strayed,

[with] pride, the bloom of Greece

was raked as time ground on,

ground down, and then the cure for the storm

and it was harsher – Calchas cried,

“My captains, Artemis must have blood!” (110)

The old men of the chorus remembered this, and they knew that Queen Clytemnestra remembered it. King Agamemnon had sacrificed their daughter, Iphigenia. The Greeks had taken Iphigenia out to the ocean, and forced her over an altar there. They gagged her. Her soft saffron colored robes blew in the sand, and they murdered her, so that the winds would take them to Troy. The poor young woman had been killed so that the war could start in earnest. And when Agamemnon killed his daughter, the chorus agreed, “he slipped his neck in the strap of Fate, / his spirit veering black, impure, unholy, / once he turned he stopped at nothing” (110). [music]

Clytemnestra’s First Lines

The chorus’ leader addressed Queen Clytemnestra, and the old men of Argos asked her why she was lighting the sacrificial fires. And Clytemnestra replied, in her first line in the play, “Let the new day shine – as the proverb says – / glorious from the womb of Mother Night” (112). What a magnificent first line for a major character in world literature, by the way! The chorus leader asked Clytemnestra about the end of the Trojan War, and the queen explained how a system of signal fires had relayed news of the Greek victory back to Argos. Clytemnestra said the Greeks were at that moment making lodgings in the houses of Troy.Left to themselves, the old men of the chorus mused on the queen’s words. Paris, the old men said, had insulted Greek hospitality unforgivably by stealing Helen away – the Gods would no longer hear his prayers. And yet Agamemnon had also committed a terrible affront by sacrificing his daughter Iphigenia in order to sail to the war. And many Greeks had died grisly deaths all for the sake of Menelaus’ wife. The chorus knew that in the lands of Argos, the families of dead Greek soldiers were “mutter[ing] / in secret and the rancor steals / toward our staunch defenders, Atreus’ sons” (119). Separately, the men of the chorus discussed the breaking news, and meanwhile, a herald arrived on a ship. The herald landed at the beach near the palace and ran up to the assembly of old men, kneeling before them.

This newly arrived herald was a Greek who had come all the way from Troy. He had been in the Trojan War for the past ten years, and he ran his fingers gratefully through the soil of his homeland of Argos. The newcomer told the chorus of old men to welcome King Agamemnon home when the king arrived. The herald proclaimed, “[G]reet him well – so many years are lost, [Agamemnon] comes, he brings us light in the darkness. . .Give him the royal welcome he deserves!” (121).

The chorus asked the recent arrival from Troy what conditions had been like, and the herald told them. For ten years the Greeks been penned into the ship camps like livestock, inhabiting quagmires and gulches, being preyed on by lice, sleet, and in the summer, beatingly hot, windless days. But, the herald said, it had ultimately been worth it. They’d won.

Queen Clytemnestra then came out of the palace. By all appearances she was joyous at the news of her husband’s victory overseas, and Agamemnon’s imminent arrival. Clytemnestra asked, “What dawn can feast a woman’s eyes like this? / I can see the light, the husband plucked from war / by the Saving God. . .As for his wife, / may he return and find her true at hall, / just as the day he left her, faithful to the last” (125). Queen Clytemnestra wheeled and turned back into the palace. The chorus discussed her words with some dubiety, and then talked about the fate of Menelaus, whose ships had been separated from the main Greek armada during a terrible storm. They pondered beautiful Helen, who had come into Troy on a wedding day of blood that harkened the coming of hell. They thought about how violence begat violence, over the course of generations. And they chorus of old men from Argos sung of a certain kind of personality that sought grandeur, and wealth, and finery, and would do horrible things in their pursuit. And, the chorus lamented, while warmongers and tyrants passed down their desperate and destructive need for distinction and power, meanwhile in humble dwellings, just, decent people thrived for generations, well loved by the gods. With this sentiment, the chorus finished their song. And at just this moment, riding in his chariot, returning to his palace among heaps of sparkling plunder taken from Troy, King Agamemnon finally arrived home. [music]

Agamemnon’s New Slave Cassandra

The king’s servants carried gold and bronze treasures. But half hidden behind him in his chariot was his favorite piece of plunder from the Trojan War. It wasn’t a gold statue, or throne, or fine suit of bronze armor. It was a girl. She was a princess, and her name was Cassandra.The old men of the chorus pressed in around him, and expressed their satisfaction at his return. Agamemnon thanked them for their loyalty, and then he turned to Clytemnestra. Momentously, the queen announced that the anguish of a woman with an absent husband was intense and terrible. Clytemnestra said that she wished their son, Orestes, were there to be with them, and then bid Agamemnon to come down from his chariot. Rich red tapestries had been placed between the king’s chariot and the palace doors.

Agamemnon said that the Queen was fawning over him too much. He didn’t need to walk on a red carpet. He was no glittery, effeminate eastern king. After they exchanged further remarks, Agamemnon removed his travelling boots and he descended from the chariot. Behind him came the Trojan princess Cassandra, dressed as a sacred priestess of Apollo. As everyone gazed at Cassandra, Agamemnon explained that his new concubine must be treated kindly, because he considered her “The gift of the armies, / flower and pride of all the wealth we won, / she follows me from Troy” (139). He said he might walk on the fine red tapestries, after all.

Clytemnestra didn’t bat an eyelash. Of course he should walk on the tapestries, she said, just like Zeus trampling red grapes into wine. And the King, and the Queen, following these ceremonial words of public reunion, vanished into the palace. [music]

The Oracles of Cassandra

Outside, the old men of the chorus conversed worriedly. They were elated that the king was back, but still, a foreboding sense of dread hung over them – dread mixed with a choking panic. A minute later Queen Clytemnestra reemerged from the palace, and she addressed the newcomer Cassandra. She said, “Won’t you come inside? I mean you, Cassandra. / Zeus in all his mercy wants you to share / some victory libations with the house. . .Down from the chariot, / this is no time for pride. Why even Heracles, / they say, was sold into bondage long ago, / he had to endure the bitter bread of slaves” (142).

John Collier’s Cassandra. Collier’s painting captures the pain and fatigue of this Trojan heroine after she endured a ten year war and awful abuses at the hands of the Greeks.

When the queen left, Cassandra finally stepped down from King Agamemnon’s chariot. Her speech, when she spoke at last, was broken and confused. She said, “God of the iron marches. . .Apollo Apollo my destroyer – / where, where have you led me now? what house – [?]” (144). They told her. She was in the House of Atreus. Cassandra said, “No. . .[T]he house that hates god, / an echoing womb of guilt, kinsmen / torturing kinsmen, severed heads, / slaughterhouse of heroes, soil streaming [with] blood. . .babies / wailing, skewered on the sword, / their flesh charred, the father gorging on their parts” (145).

The captured princess Cassandra began a series of dark oracles. She knew she was in a terrible place and saw that unspeakable things would continue to happen there. Her visions were horrifying, and at the climax of them, Cassandra saw a female figure, wielding a net, and a male figure, killed as though gored to death with the black horn of a bull. The chorus could not make sense of these visions, and they thought Cassandra mad. Cassandra cried and saw visions of her family – her venerable old father Priam, making sacrifices, and the last embers of the burning city of Troy. Cassandra saw visions of frightening creatures cavorting atop the roof of the house of Atreus, preparing for dreadful things to come.

The chorus of old men from Argos was awestruck at her strange speech and foreboding visions. They asked Cassandra about the origins of these visions. Cassandra had been given a partial gift from Apollo, she said, when she had refused to bear him a child. She could see the future, and told others of her visions, but they were never believed. And she followed this explanation with another vision of atrocities – disemboweled children, a woman waiting to kill a man, like a viper, like a sea monster lurking in a nest of rocks, and at the end of her oracle, Cassandra said, “Believe me if you will. What will it matter / if you won’t? It comes when it comes, / and soon you’ll see it face to face. . .Agamemnon. / You will see him dead” (152-3). She, too, she said, would be killed – she could already see a cleaver with her blood on it. So saying, the captured princess Cassandra went toward the palace doors and exclaimed, “Murder. / The house breathes with murder – bloody shambles!. . .I know that odor. I smell the open grave” (157). After a few more words, the Trojan princess turned and went into the palace. [music]

Agamemnon‘s Climactic Moment

The old men of the chorus heard a terrible clamor from within the palace. They heard King Agamemnon shrieking. Chaos broke out in the ranks of the chorus. Some proposed that the guards should be summoned and sent into the palace. Others panicked, distraught that new rulers might be coming to the land of Argos. Just as they resolved to root out what had happened, the palace doors burst open.In the threshold of the palace, Clytemnestra stood alongside a silver cauldron. The cauldron contained the gory remains of Agamemnon, wrapped in a bloody robe. Cassandra, murdered, lay on the other side of the silver cauldron from the queen. Queen Clytemnestra approached the chorus imperiously, and she began a long speech, this time in the University of Chicago Richard Lattimore translation. Cassandra said:

I stand now where I struck him down. The thing is done.

Thus have I wrought, and I will not deny it now.

That he might not escape nor beat aside his death,

as fishermen cast their huge circling nets, I spread

deadly abundance of rich robes, and caught him fast.

I struck him twice. In two great cries of agony

he buckled at the knees and fell. When he was down

I struck him the third blow, in thanks and reverence

To Zeus beneath the ground, the prayed-for Savior of the dead.

Thus he went down, and the life struggled out of him;

and as he died he spattered me with the dark red

and violent driven rain of bitter-savored blood

to make me glad, as plants stand. . .amidst the showers

of god in glory at the birthtime of the buds. (1379-92)6

The chorus of old men of Argos was shocked. They couldn’t believe that Clytemnestra would exult over her murder. Clytemnestra said her heart was steel, and that she had done what was just. Agamemnon, said Clytemnestra, had murdered their poor daughter just so that he and his ships could get favorable winds to blow them to the Trojan War.

John Collier’s Clytemnestra (1882). The painting, with its bloody ax and the resolute expression of the heroine, crackles with the same power as some of Aeschylus’ best lines.

The chorus could not disagree, with her, but still, they presaged that no good would come of the killing. They observed that “[T]he roofs are toppling. I dread the drumbeat thunder / the heavy rains of blood will crush the house / the first light rains are over – / Justice brings new acts of agony, yes, / on new grindstones Fate is grinding sharp the sword of Justice” (166).

From the palace, a new character emerged. His name was Aegisthus. He was Agamemnon’s cousin. And second cousin. And Clytemnestra’s lover. Now, a recap on the Atreus family tree. The parents of Aegisthus and Agamemnon were brothers. Agamemnon’s dad had killed some of Aegisthus’ siblings, and fed them to Aegisthus’ dad. Aegisthus’ dad had then been told to have sex with his daughter, thus resulting in the birth of Aegisthus. And when he came of age, Aegisthus had murdered Agamemnon’s dad. So, while Agamemnon had been away during the ten-year Trojan War, Aegisthus had moved in on Agamemnon’s wife, Clytemnestra. Clytemnestra hated her husband because he had murdered their daughter in a sacrifice, and so, out of mutual loathing for King Agamemnon, his wife and his cousin slash second cousin Aegisthus had murdered him. Aegisthus is pretty important character in the Oresteia – he’ll be around for a while.

So, everyone had plenty of cause to hate everyone else, and Aegisthus, needless to say, believed that his brutal murder of his cousin Agamemnon was entirely justified. In fact, Aegisthus came right out of the gates explaining his motivations to the old men of the chorus. Aegisthus gave a particularly lurid account of Agamemnon’s father dismembering children and feeding them to his nemesis – again Aegisthus’ father. Aegisthus himself was unrepentant about the murder of the king. Agamemnon had deserved the agony of death, Aegisthus said.

The chorus of old men from Argos responded to Aegisthus with bitter hostility. In their eyes, Agamemnon’s cousin was a usurper who had slaughtered the rightful king. Aegisthus would answer for the murder, they said. But Aegisthus spat at this idea. He said he had been justified, and he dismissed the chorus’ threats. Swords were drawn, but Clytemnestra restrained both sides. And the last three lines of the play Agamemnon strike some very ominous tones. Clytemnestra growled, “I promise you, you’ll pay, old fools – in good time, too!” (172). And the leader of the elders from Argos said, “Strut on your dunghill, you cock beside your mate” (172). And Queen Clytemnestra cautioned her lover Aegisthus a final time. She said, “Let them howl – they’re impotent. You and I have power now. / We will set the house in order once for all” (172). And that’s the end. [music]

“Aeschylus the Athenian”

That, again, was the end of Agamemnon, the first of the three plays in the Oresteia. To quickly review what we learned last time, this play would have been staged in the morning, with Clytemnestra’s ferocious final words echoing up through the theater benches as the musicians played some sort of closing piece, and there would be an intermission, after which Athenians in attendance would go and watch the second and third installments of the story. If we were there, this is where we might grab lunch, take a moment to catch up with friends, say “Holy [censored] that play was amazing” and talk about it a bit, and then, before long, sit back down to watch the second part of the trilogy.While I can’t offer you a nice ancient Greek lunch, or a brisk walk around the Acropolis to stretch your legs, such as the play’s original attendants would have had at this point, I do have some additional information for you about the context of the play Agamemnon. Specifically, I want to talk a bit about our tragedian for today, Aeschylus – what we know about who he was, historically, and how his biographical experiences may have influenced the plays that he wrote.

Aeschylus is a giant in literary history for many reasons. For our purposes today, one of those reasons is that he’s the first person we’ve come to in this podcast that we actually know a little bit about. As for Hesiod, or Homer, or the biblical prophets Isaiah, Jeremiah, and Ezekiel, or even archaic Greek writers we’ve covered like Sappho and Pindar, we know very little – in some cases with these folks we don’t even know if they were real people. But with Aeschylus, we have some widespread biographical fragments, and we also have records of the period of history in which he lived. We know about historical events that he experienced, and, seeings as this podcast is called “Literature and History,” it’s time to talk a bit about the extraordinary period of time in which Aeschylus lived, and how this period of time probably influenced his writings.

After Aeschylus died – just a couple of years after producing the plays we’ve just been talking about, by the way – he was old by 458 BCE, when the Oresteia won him the first-place laurel crown at the Dionysia festival. Anyway, after Aeschylus died, according to one chronicler, his headstone bore a curious inscription. This great Athenian playwright’s headstone said, “Under this stone lies Aeschylus the Athenian. . .the grove at Marathon and the Persians who landed there were witnesses to his courage.”7 Again, “Under this stone lies Aeschylus the Athenian. . .the grove at Marathon and the Persians who landed there were witnesses to his courage.” Why should this epitaph seem peculiar to us? Well, put simply, the inscription says nothing about his plays, or his revolutionary work in the theater. Instead, it makes reference to something that happened 35 years before he died, something so pivotal, and so definitive to the history of Athens that it actually overshadowed all of old Aeschylus’ dramatic achievements. This event was the Battle of Marathon, in which Aeschylus fought, a decisive battle against the Persian Empire that happened in 490 BCE. Aeschylus also fought at the Battle of Salamis against the Persian fleet ten years later, a naval battle waged southwest of Athens, in which the Greeks scored a decisive victory. In both cases, the Greeks were outnumbered, and due to their superior equipment and military tactics, they scored unlikely triumphs. Aeschylus, then, had been involved with the most perilous and pivotal battles in Athenian history. By the time of his death around 456 BCE, Aeschylus was venerated for the literature that he produced. But perhaps even more so, he was venerated for his military service.

I talked about the Persian Empire a bit during Episode 22 on the Book of Ecclesiastes. But this show and the next nine shows are all the theatrical works of classical Athens. And these theatrical works were created during a century sandwiched between wars – the Persian Wars, at the beginning of the 400s, and the Peloponnesian War, at the end of the 400s. We’ll get to the latter war in a little while, once the literature does. For now, let’s stick with the conflicts that historians have very practically named the Greco-Persian Wars, and explore the basics of how those wars affected Aeschylus and his contemporaries. [music]

The Greco-Persian Wars

The Achaemenid Persian Empire was the first of three ancient Persian empires seated in central Eurasia. Although in the English-speaking world, the Achaemenid, Parthian, and Sasanian empires don’t get a lot of educational airtime, they were an anchor in central Eurasia for more than a thousand years, from 550 BCE all the way up until 650 CE. We’ll talk about ancient Persian history plenty in our podcast in programs to come. But for the purposes of today’s show, which is to understand the context of the Oresteia, we can cover Achaemenid Persia fairly quickly.

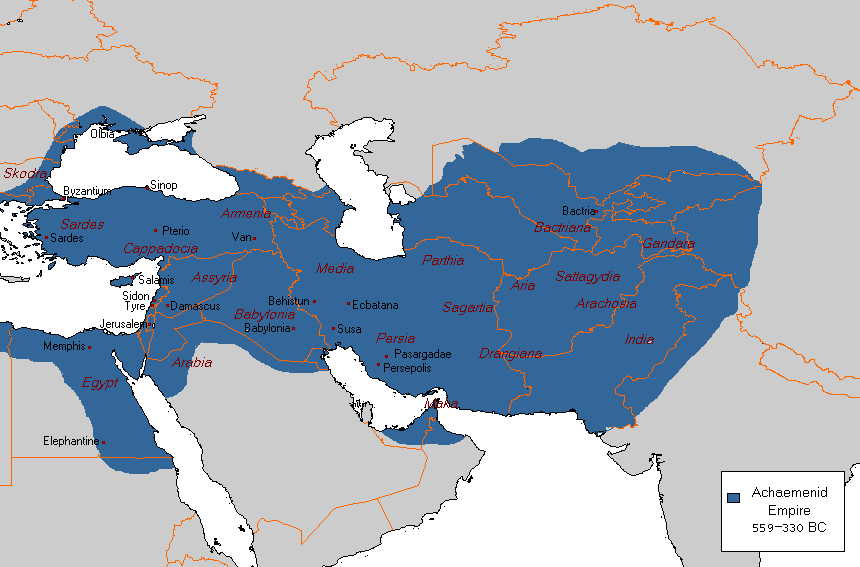

The Achaemenid Empire at its greatest extent. Hindering the empire’s westward expansion, from the mid 490s to the mid 470s, was the central occupation of Aeschylus’ generation of Athenians.

The Persians ate Egypt for breakfast thirty-five years before they met the comparatively smaller city of Athens in battle for the first time. The nice thing about conquering Egypt was that everyone was more or less together in one place, along the river and delta. Egypt was by this point in history fairly ethnically diverse, and did have significant settlements out west in oases, to the south along the upper Nile. But in comparison to Greece, Egypt in 525 BCE was eminently conquerable. Their current dynasty of Pharaohs had ruled for almost a hundred and forty years. The Persians conquered this dynasty, and the lands of the Nile were theirs.

Greece proved much more challenging. If you were trying to take over Greece in 500 BCE, which the Persians were, you had a number of challenges to contend with. Even if no one had lived there, the Aegean world was a maze of islands, bays, isthmuses, straits, hills, mountains, and tricky passes. Just exploring it would have been difficult. But exploring it when it was full of resistant locals, and when these locals pretended to be loyal to your empire only to double cross you later – this was really difficult. And it got no easier when, once you tried your divide and conquer tactics, those Aegean locals pretended to be loyal to you, only to make alliances with one another, or, in sudden unexpected windfalls, came to meet you in peace where you’d brought a large army expecting a war. The Persians were capable of fighting massive land battles – they’d taken Egypt this way in the spring of 525 BCE. But when they went into the Aegean, they faced a multi-decade war of attrition. Rather than an organized campaign forward, they were confronted by a geographical labyrinth, and a bewildering checkerboard of city states that fought one another, and banned together, and fought the Persians, and fragmented and fell in line, only to rebel again later. The Greeks were utterly unpredictable. To make things worse, meeting these forces in combat was always a distinct challenge. The Greeks were fewer in number, but they were tough, and they knew the turf. They were incredible oarsmen and sailors. Their weapons and armor made them particularly formidable.

Additionally, Greek speakers lived in an area of the world that, unlike Mesopotamia and Egypt, had not seen a slideshow of different centuries of conquerors. The Levant, for instance, had bowed under Egyptian rule, and then Assyrian, then Babylonian, all before the Persians arrived there, changed some of the street signs and tax rules, and dusted off their hands. Greece, by contrast – especially stronger mainland city states like Athens, Corinth, and Sparta, had no memories of acceding to foreign rule. These tough little civilizations, especially Sparta, proved, quite shockingly, willing to fight it out to the last, rather than to accept the nominal rule of a foreign king. So in summation, from the Persian perspective, tiny, rocky little Greece seemed like it would be a nice little gemstone to add to the crowns of Darius and Xerxes, once the Aegean world started nipping away at the westernmost part of the Persian Empire in the 490s. The problem was, Greece itself, and the leathery little city-states therein, were unlike anything the vast Achaemenid Empire had ever seen before. In the words of historian Tom Holland, “[T]he [Greeks], to [the Persians], were an enigma— and a challenge. All they ever did, it seemed to the Persians, was quarrel. This interminable feuding, which had helped immensely when it came to conquering them, also made them a uniquely wearisome people to rule. Where the Lydians had their bureaucrats and the Judaeans their priests, the Greeks seemed to have only treacherous and floating factions.”8

So let’s bring it back to Aeschylus. Aeschylus was born around 525 BCE. And he died around 456. Over the course of his seventy or so years of life, Aeschylus saw Athens go from an ordinary dictatorship to a tightly run democracy that controlled the oceans of the Eastern Mediterranean. The day Aeschylus was born, his home city of Athens was a scrappy little kingdom, indistinguishable from its neighbors, ruled by a pair of brothers. When Aeschylus was 9, one of these brothers was assassinated. When Aeschylus was 15, he saw Athens at war for the first time – a Spartan invasion force led by an Athenian named Cleisthenes broke in and crushed the oppressive tyrant who’d been ruling in Athens. Cleisthenes then pushed for democracy, but the Spartan army who had backed him wanted to make Athens into a client kingdom. The Spartans consolidated their power in the city, but they were beaten back by a gigantic popular uprising. And when Aeschylus was eighteen, the man who had proposed democracy and beaten the tyrant of Athens, Cleisthenes, returned, and the free speech, legislative input, and votes were extended to all free male citizens of Athens. In 507, around his eighteenth birthday, Aeschylus saw the birth of Athenian democracy.

As Aeschylus turned nineteen, and then twenty, he saw the countryside around Athens being restructured into what were called “demes,” or regional blocks. To resist old clannish tendencies and feudal centers around the city, Athenians broke the countryside up into subsections that fractured old power structures. During these years Aeschylus again experienced war, as Sparta returned and tried and take the city that had rebelled a few years earlier. Sparta failed, along with its northern ally, Thebes. A quote from the historian Herodotus sums up what Aeschylus had seen by his twenty-first birthday. Herodotus wrote:

Thus did the Athenians increase in strength. And it is plain enough, not from this instance only, but from. . .everywhere, that freedom is an excellent thing since even the Athenians, who, while they continued under the rule of tyrants, were not a whit more valiant than any of their neighbors, no sooner shook off the yoke than they became decidedly the first of all. These things show that, while undergoing oppression, they let themselves be beaten, since they worked for a master; but so soon as they got their freedom, each man was eager to do the best he could for himself.9

In the first years of Athens’ democracy, Aeschylus saw statues and buildings being erected all around the Acropolis, or central rocky promontory in Athens – a 5,000 seat Assembly, and a vast bronze statue of a horses and chariot. But Aeschylus wasn’t the only one who knew about these developments in Athenian history.

The Persian king heard of the restructuring of power in Athens. It was of great interest, since his brother held a capital in the west part of Anatolia, just across the Aegean from Athens. Athenians and their allies, all rising in power to the west, rebelled throughout the western par of what’s today Turkey, and burnt the western Persian capital to the ground. This insurrection took place around 498, when Aeschylus was 27. And a few years later, in 494, Aeschylus saw one of the most remarkable people in ancient history come to influence in Athens.

His name was Themistocles. And Themistocles believed in the navy. Over and above armies that they could muster on land, Themistocles believed that if the Athenians could control the water, they could control the Aegean. Themistocles agitated for militarization. And it was a good time to be thinking about militarization. To the east, in the Aegean, Persia had taken the large and famous island of Miletus, one of Greece’s intellectual and cultural centers. And the Argives, a people to the north and west of Sparta and Athens, consolidated an alliance with Persia.10

In 492, Aeschylus was thirty-three, and a gigantic Persian fleet began making its way down into Aegean, conquering territories in present day Bulgaria and Macedonia. Persian ambassadors were sent to Athens and Sparta. In both places, they were convicted and killed. By 490, the Persians had conquered more Aegean territories, and bore down on Athens. Aeschylus was 35 years old. He’d been at ground zero for a number of terrifically important moments in ancient history. And he was about to see more.

The Persian beachhead and plain at Marathon, where Aeschylus fought before hurry some 26 miles back to Athens to guard the city from a secondary invasion force.

Athenian infantrymen of this period, including of course Aeschylus, used large circular shields, a meter in diameter, called hopla, from which we get the name “hoplites.” Their military formations required each man to lock shields and depend on his neighbors during each offensive or defensive maneuver. And as the Athenians looked across the Plain of Marathon in August of 490, you have to think that their new national identity as a democracy must have been intermingled with a sense that they were there voluntarily, and that just as in peacetime, each man was partly responsible for the rights and wellbeing of his neighbors.

What happened next was one of the great underdog victories of ancient history. The Athenian infantry didn’t just win. When the two armies crunched together, the Athenians shattered the Persian invaders who’d showed up on their shores. Their weapons and armor were technologically superior. And I imagine that their resolve and will to throw themselves into combat was far greater than those of the Persian armies, who were far from home and fighting a war that wouldn’t bring them any particular benefit or distinction. According to Greek records, 6,400 Persians and Medes died in the fighting, and only 192 Athenians. For every thirty-three soldiers Persia lost, Athens lost one. Are these figures exaggerated by the ancient historians? Almost certainly. But at any rate, Athens won. And according to the record, one of the dead Athenians was Aeschylus’ brother.

Following this victory at Marathon, what did the Greek infantry do? Did they wash their weapons in the sea, or drink to victory, or burn every single Persian ship? No, actually, though they did manage to burn seven Persian ships before the foreign fleet disembarked. The Athenian army knew they had plenty to deal with. The Persian cavalry was still out there. And so the Athenians undertook history’s most famous run. The modern marathon is named after the 26.2 or so miles that the Athenian infantry ran from Marathon back to Athens to make sure that the Persian cavalry wasn’t burning the city in their absence. It wasn’t. The battle of Marathon was an unqualified victory for Athens. And as a mediocre marathon runner, I always try to imagine running a marathon after facing a gigantic land army, carrying a spear and large bronze shield the whole way, and doing the whole thing in armor and leather sandals, and the moral of the story is that the ancient world is inspiring and humbling. [music]

The Naval Militarization of Athens

I think that the Battle of Marathon is referred to on Aeschylus’ tombstone because August of 490 was the moment at which Athens realized that it could not only face a superpower. It was the moment Athens realized it that could be a superpower. Only, there was one thing still standing in the way, and this was that the world’s existing superpower, Persia, saw their loss at the Battle of Marathon to be a very minor incident. The loss of 6,000 or so infantrymen wasn’t especially significant to Persia. After Marathon, to the south, in Egypt, Persia lost its king, and a new one soon came to power. The new king, Xerxes, decided it was time to finish his father’s campaign against those rowdy, polytheistic bumpkins over to the west in the Aegean. And he wanted to do it with gusto.King Xerxes was advised to bring an elite strike force, probably of horse archers, to combat the hardened Greek phalanxes. For Xerxes, this wasn’t sufficient. He wanted something immense – a land army so gigantic that a pontoon bridge had to be built across the Hellespont, and in other places mile wide canals had to be dug for his fleet.

The response from Persia was slow, and colossal. Athens began hearing rumors of it in the second half of the 480s, as Aeschylus reached the age of 40. Imagine having fought in wars your whole life, having lost your brother, and then, as you reach middle age, and expect a well-deserved respite from all your hard work, you hear that hundreds of thousands of people are inbound, and that they’re bringing every conceivable kind of weapon and military conveyance, and they plan to reduce you and everyone you know to corpses and slaves. That was what Aeschylus experienced as he blew out the candles on his fortieth birthday cake.

But the late 480s weren’t all bad for Athens. The year 483 saw a remarkable stroke of luck for Aeschylus’ hometown, when a gigantic deposit of silver was discovered in the city’s territory. And Athens, listening to its veteran and statesman Themistocles, used this silver to undertake a naval militarization that was swift and remarkably effective, constructing hundreds of new elite vessels, rowed by three decks of oarsmen, called triremes. For the remainder of Athens’ classical period, the trireme would be the quintessence of the Athenian spirit – fast, versatile, far ranging, and soundly engineered. Most of all, the trireme was an emblem of democratic collectivism. Each ship, with 170 salaried citizen rowers, needed perfect collaboration and communication in order to coordinate its remarkable eleven-and-a-half-hour continuous speed and crucial ramming maneuvers.11 Aeschylus, and other Greek dramatists we’ll soon discuss, knew the decks of triremes well. [music]

Salamis, Plataea, and the End of the Greco-Persian Wars

So Athens built a great fleet with their new store of silver. They didn’t regret it. The year Aeschylus turned 45, Xerxes’ famous army of Persians bore down on mainland Greece. This second invasion, however, faced a consolidated front of Spartans and Athenians. Three major battles occurred in quick succession in the late summer of 480. The Persians lost huge volumes of ships in the Aegean due to an unlucky sequence of storms. They faced unexpectedly stalwart resistance as they tried to advance south through the pass at Thermopylae, where a small Spartan force could only be unseated after being betrayed by one of its allies. Although the Persians won Thermopylae, they lost a nearby naval battle called Artemisium. And what happened next sent Xerxes, and much of his jumbo army home for good.Aeschylus, now aged 45, fought in the great naval battle at Salamis, a battle in which an outnumbered, beleaguered flotilla of Athenian ships defeated the Persian navy and sent it packing. Everything hinged on this battle. Athens itself had been abandoned to help with the general military maneuvers – the monuments erected on the Acropolis decades earlier were crushed by Persian invaders, and the city was looted. The Battle of Salamis, if it had been lost, would have been the end of the fledgling democracy that later proved so influential. But just as Athens had achieved an unlikely victory at Marathon a decade earlier, careful maneuvering and misinformation tactics duped the Persians into a compromised position at Salamis, and Athens won. And the next summer, once Xerxes had left the war in the hands of his general Mardonius, an alliance of Greek armies including Athens, Sparta, Corinth, and Megara faced the Persian empire a final time and defeated them. The Persian general Mardonius was killed.

And there’s a famous anecdote in Herodotus about the end of this battle – the final one that would be fought against the Persians in mainland Greece. The great king Xerxes, after he’d headed home in 480 after the disappointment at Salamis, had left his tent with his general Mardonius. This tent was purportedly lavish, the sort of thing that made most Greek palaces seem plain by comparison, and again this was simply the king’s campaign tent – not a palace, or anything.

Aeschylus had seen this tent. In fact, he may have seen a lot of it. The Oresteia plays, although they are by far Aeschylus’ most famous works, weren’t his only plays. He’d actually produced as many as 90 plays.12 An early play, The Persians, was produced in 472 BCE. And according to one study, the tent captured at the final battle against the Persians was on prominent display at the Theater of Dionysus in Athens, during this play Aeschylus wrote about the Greco-Persian Wars. It had been configured into a shade that hung over the orchestra area. And all around it, the wooden benches of the theater were crafted from the planks of Persian ships sunk during the previous decades of wars.13 We don’t know how long these unique furnishings stayed there, in the Theater of Dionysus. But suffice it to say that as you sat in the Theater of Dionysus in the 470s, 460s, and 450s, you were actually surrounded with the bits and pieces of the defeated Persian campaign – their royal tent, the benches that their rowers sat on, the timber that kept their great fleet afloat. As Athens made a blindingly spectacular recovery from the Persian Wars during these decades, it did not forget how close it had come to annihilation. [music]

Moving on to The Libation Bearers

So let’s get back to the play we covered today, Agamemnon. We still have a ways to go with the Oresteia as a whole – this, again, is the intermission bit, where we eat bread and olives. But in addition to hearing the prologue and the story of the first of the three plays, you also now know a bit about the military career of their author, and how the Greco-Persian Wars of the early 400s BCE were the definitive event in Athens for the first generation of classical Greek history, lingering in the average Athenian’s mind as he or she sat down in the spring of 458 BCE to watch Aeschylus’ most famous plays. You know that Aeschylus’ audience might have actually been sitting on Persian lumber, and that perhaps a large tent, a little frayed at the edges, might have fluttered above the orchestra area where the play Agamemnon was first staged. Agamemnon is about the brutal death of a returning conqueror. The king has murdered his daughter Iphigenia, sped off to Troy, proved a horror to the city for a decade, and then, finally beaten it, destroyed it, killed its inhabitants, and made its princess into a personal sex slave. To the Athenians of 458 BCE, Agamemnon would have been more than just a villain from the storied Homeric epics. He was an archetype. Men like Agamemnon had ruled Athens before democracy had been installed there. Men like Agamemnon had filled an entire generation’s life with war. During the Persian sack of Athens, one man like Agamemnon had occupied Athens in the darkest hour of the democracy’s history in the spring just over two decades ago, and shattered the temples and statues that had once been a hundred meters behind the Athenians who watched Aeschylus’ plays, as they sat in the Theater of Dionysus. And that previous Agamemnon’s tent, again, a bit worse for the wear by time, might have still flapped and rippled above the stage as the actors playing Agamemnon, Clytemnestra, and Aegisthus voiced their lines. A play about a bloody king was staged beneath and amidst the detritus of a real bloody king. The play Agamemnon ends as do many of ancient Athens’ plays concerning tyrants. Hubris proves to be a lethal setback. The tyrant falls, humiliated. Even the first play of the Oresteian trilogy must have struck a powerful chord with Aeschylus’ audience, as they sat there on the remnants of a real conqueror’s failed expedition, hearing about another commander who also, eventually, faced failure and retribution. To the Athenians of the 450s BCE, Agamemnon was just another bloated city sacker, another failed Xerxes, another blind megalomaniac who’d stepped too far, and stumbled. But Aeschylus knew, and his fellow Athenians knew, that history did not end with the toppling of a tyrant. The city was fifty years into the establishment of democracy in the spring of 458 BCE, when the play Agamemnon was first staged. Athenians understood well enough that the collapse of an oppressive regime didn’t lead to credits rolling, happy outro music, and a bunch of montages in soft pastels. They knew that challenges continued to unfold. The playwright was 67 years old when Agamemnon was produced, and fifty of these years had been lived under democracy. An ending in which the tyrant fell, and everyone lived happily ever after, would just not do. So in the next show, we’re going to hear the rest of the story – the same story that an incredible generation of Athenians heard in the mid-spring of 458 BCE and appreciated so much. The trilogy’s main character, Agamemnon’s son, Orestes, is going to come home and find that his dad’s cousin and his mother have murdered his father. But unlike many similar revenge stories, Orestes’ tale does not end with just another retributive murder that signifies the coming of more – the slow and hideous generational blossoming of the curse of the House of Atreus. Orestes’ story, like the story of ancient Athens, and we hope, like our own, is one in which a person can learn from his mistakes, in which natural proclivities can be overcome, and in which one, through great effort, can transcend the circumstances of his birth and determine the course of his own future. I can’t wait to continue the trilogy with you in the next program, Episode 28, A Mother’s Curse. There’s a quiz on this program available there in the notes section of your podcast app. Thanks for listening to Literature and History, and if you listen to the songs, I’ve got one coming up. If not, see you next time. Still here? Nice. So I got to thinking. Throughout the course of this year, I’ve been neck deep in ancient history – in military campaigns, monumental inscriptions, and victory steles. And I’ve met a lot of really arrogant monarchs – ones like Xerxes, and Ramses II and Amenhotep III, and Tiglath-Pileser and Sennacherib and Nebuchadnezzar. And I decided to try and capture the essence of a toweringly, ridiculously arrogant ancient monarch in a song. I thought I’d do something kind of minor, in march time. So this song is narrated from the perspective of Agamemnon, and it’s called “Hello, My Name is Agamemnon.” Thanks for listening to Literature and History, and Clytemnestra, Orestes, Aegisthus, and I will see you next time!References

2.^ Nagler, M.N. “Ethical anxiety and artistic inconsistency: The case of oral epic.” Printed in Cabinet of the Muses: Essays on Classical and Comparative Literature in Honor of Thomas G. Rosenmeyer. Scholars Press, 1990, p. 233.

3.^ The Hellenistic scholars Aristophanes of Byzantium and Aristarchus of Samos wished that it had concluded at 23.293-5, and had no 24th book at all.

4.^ He appears toward the tail end of the nekyia (11.584-92).

5.^ Aeschylus. Agamemnon. Printed in The Oresteia: Agamemnon, The Libation Bearers, The Eumenides. Translated by Robert Fagles. Penguin Books, 1977, p. 104. Further references to this text will be noted parenthetically in the episode transcription.

6.^ Aeschylus. Agamemnon. Printed in Aeschylus II. Edited by David Greene and Richard Lattimore. University of Chicago Press, 2013, p. 68.

8.^ Holland, Tom. Persian Fire. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. Kindle Edition, Locations 2640-2.

9.^ Herodotus. Histories (5:78). Translated by George Rawlinson. Digireads Publishing, 2004, pp. 293-4.

10.^ This was Agamemnon’s legendary city, making Aeschylus’ parallels between Agamemnon and the Persian despots even more compelling.

11.^ Hale, John. Lords of the Sea: How Athenian Trireme Battles Changed History. Gibson Square. Kindle Edition, 2014, Location 174.

12.^ See Ley, Graham. A Short Introduction to the Ancient Greek Theater: Revised Edition. University of Chicago Press, 2006, p. 5.

13.^ Broneer, Oscar. “The Tent of Xerxes and the Greek Theater.” University of California Publications in Classical Archaeology. 1: 1944.