Episode 44: Homo Sum

The Roman playwright Terence (c. 184-159 BCE) produced a string of brilliant comedies in the 160s BCE. His masterpiece, The Brothers, continues to astonish us today.

| Read Transcription | References and Notes |

| Episode Quiz | Episode Song |

| Episode on Spotify | Episode on Apple Podcasts |

| Previous Show | Next Show |

Terence’s The Brothers

Hello, and welcome to Literature and History. Episode 44: Homo Sum. This show is on the Roman playwright Terence, who lived from about 184-159 BCE. This program will first introduce you to Terence and his world, and the central part of it will be devoted to exploring Terence’s final play and probably his masterpiece, The Brothers, and lastly, as we usually do in this podcast, we’ll consider the historical background of the literature that we’re going to read together – how Terence’s work reflects the culture and time period in which he lived.I read Terence for the first time in my last year of college. There used to be a microfilm and microfiche room off the east side of the first floor of the Doe Library at UC Berkeley. It was my preferred place to read as an undergrad – it had mouldering green paint the color of a key lime pie, corroded cement all over the place, and ugly, scarred, pitted tables. And even better, this huge microfilm room had a basement, where the walls were even more decrepit, the tables even more ramshackle, and in total it was all so ugly and silent that no matter what I brought down there to read, my books were always more interesting than my surroundings. I must be the only living human being who has happy memories of that hideous basement, because of all the great stuff I read down there, but anyway, let’s get to Terence.

When I read Terence down there, down in the furthest, dingiest corner of that microfilm basement, I kept stopping. I’d read a monologue, and shake my head and mutter, “No way,” or “Wow,” or most often “Really, this was written in the 160s B.C.?” I mean there was no one down there – I could talk to myself with impunity – and I kept stopping, with incredulity, to reread soliloquies and rapid back and forth dialogues, and I must have gone through a pen or two underlining passages I loved and drawing little smiley faces and exclamation points next to them. I read an older translation back then – Betty Radice’s, and while writing this show I reread some Terence plays in a more recent translation by Peter Brown, and in both cases, I would describe the experience of reading Terence as follows. It was like someone had taken a play, modeled on Greek New Comedy of the late 300s and early 200s BCE, got a hypodermic needle, and injected that play with some Tennessee Williams and Eugene O’Neill. In other words, it was as though ancient Greco-Roman comedy had been given an inconsistent but nonetheless potent shot of deep psychological realism and dynamic characterization, and the problems, and hopes, and conflicts that people had in Republican Rome were identical to the ones that we have today.

You don’t see Terence staged too much these days. During any given theatrical season, pre-modern theater is mostly a Shakespeare factory with the occasional Antigone or Medea chucked in to add variety – or maybe a Molière or Corneille. But Shakespeare himself, who, as we learned last time, modeled some plays on Plautus. Shakespeare’s contemporaries, who read both Plautus and Terence, took plots and plot devices from these Latin playwrights. And modern comedy – even cinematic comedy, is a very old tree with a trunk and root ball made out of Menander, Plautus, Terence, and a couple dozen other writers whose works are now lost. We may love the tragedy of Aeschylus, Sophocles and Euripides, with their heavy, deliberate plots and rich poetic choruses, or the comedy of Aristophanes, with its exuberant pornography and rollicking choral interludes, but in Anglophone literary history, the high theater of Classical Athens of the 400s BCE was far less influential than the Greco-Roman comedy popular from 330 onward, and it was through the Latin dramatists Plautus and Terence that this comedy reached writers at the beginning of the Renaissance.1 So, before we read Terence’s The Brothers, let’s talk a little bit about Terence – who he was, what he wrote, and what he is most famous for. [music]

Terence’s Style and Differences from Plautus

Terence was born in about 184 BCE – around the time Plautus, the playwright we covered in our previous show, died. Like Plautus, Terence adapted Greek New Comedy to the Roman stage. And also like Plautus, Terence staged generally light-hearted plays featuring stock situations – orphans returned to parents, comedic misunderstandings, love affairs, scurrilous servants and wily slaves, and resolutions involving marriages – often multiple marriages. Unlike Plautus, though, Terence died young, producing just six plays before passing away while still in his twenties. And all of these plays have survived.There are some other salient differences between these two Latin playwrights that we should talk about. Terence is often called subtler, and simpler. Classicist Betty Radice deemed Terence’s work “the most lucid and elegantly simple Latin which had yet been written.”2 Scholar Philip Whaley Harsh agrees, writing that “The style of Terence is modeled after the beautifully chaste style of Menander – very different from the lusty exuberance of Plautus.”3 Plautus captivated his audiences with exuberant wordplay, and farce; crude humor and musical elements. In Terence, much of this is minimized. That’s not to say Terence was writing something like free verse or prose – Terence still set spoken dialogue in carefully metered iambic senarii, Terence’s monodies were performed with the accompaniment of a reed-pipe player, and Terence still used formulaic plot architecture borrowed from earlier dramatists.4 Terence, in other words, was not a totally diametric departure from previous Greco-Roman drama, but considering what had come before him, he was subtler, and more complex, and required a bit more of his audience’s attention. Terence liked to spin a compounded web of dramatic irony – dramatic irony being the situation in which an audience knows something that a character or characters don’t. Terence is particularly known for using double plots – plots in which very different groups of characters are all affected by the same sequence of events, and their varying reactions to this sequence of events highlight fundamental differences in human perception and experience. In the play that we’ll read in this episode – again The Brothers, first staged in 160 BCE, we’ll see all of this in action – a lacework of dramatic irony, a double plot, and several characters who are acutely changed by what happens to them.

Today, readers like us can understand Terence as a writer in some ways two thousand years ahead of his times. But in Terence’s own lifetime – in the mid-100s BCE, his subtlety and complexity seem to have kept him from ever being as popular as his predecessor Plautus.5 As we learned in the previous show, a Roman playwright working in the 100s BCE had intense and colorful competition from alternative forms of entertainment – gladiators, boxers, strippers, exotic animal shows, and that kind of thing. Terence wrote that during the first performance of one of his plays, rather than watching it, “the foolish, fanatical public had become engrossed in a tightrope walker,” and many of them left.6 At a later performance of the same play, Terence’s audience enjoyed the production’s opening, “but then word got around that a show of gladiators was going to be given: people flocked together, there was an uproar, they were shouting and fighting for a place,” and soon enough Terence was again staging a play for a significantly reduced audience.7 It’s a sad story both times, and literary history is filled with tales of precocious brilliance misunderstood by an artist’s contemporaries, but nonetheless Terence did have a small, but important set of acquaintances who obviously had some notion of his capacities as a writer. In fact, let’s talk a bit about the biographical information that we have today about Terence. [music]

Ancient Sources on the Life of Terence

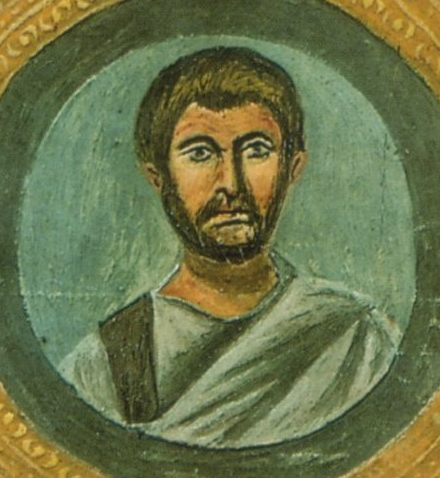

This map displays Carthage’s territory before the Second Punic War. Terence, ancient sources concur, was from the capital. Map by William Robert Shepherd.

Many sources say that Terence was a Carthaginian, born around 184 or 185 BCE. He was supposedly a medium-sized man, though particularly slender and with a dark complexion, and strikingly good-looking. During the decade that Terence was born, Carthage had already lost the Second Punic War – that’s the big one that involved Hannibal and elephants over the Alps and Cannae and Scipio Africanus. The year Terence was born, Carthage was limping along as a subaltern state, paying its huge punitive fees and licking its wounds, and Rome was already the de facto boss of the Mediterranean world. Terence came to Rome as a slave – he was purchased by a senator called Terentius Lucanus. Terence’s master evidently thought highly of him. According to Suetonius, “Terentius Lucanus, a senator . . . because of [Terence’s] talent and good looks not only gave him a liberal education, but soon set him free.”9

“Terence Reading His Play to Caecilius.” From The Comic History of Rome by Gilbert Abbott A Beckett, c. 1850.

If the biographies are accurate, Terence seemed to ingratiate people in just this fashion. Perhaps after his dinner with the famous poet, Terence fell in with an extremely illustrious crowd. We’ll talk more about this crowd toward the end of the episode, but for now it will suffice to say that Terence may well have gone from being a slave from North Africa to keeping company with some of the most powerful, educated, and influential people in Republican Rome. He spent the mid to late 160s staging his six plays, with a bit of mixed success. His second play, The Mother-in-Law, evidently failed twice and it stung him throughout his short career, but according to Suetonius, Terence’s play The Eunuch was “acted twice in the same day and earned more money than any previous comedy of any writer, namely eight thousand sesterces.”12

Whatever his reputation at the end of the 160s, Terence disappears from the historical record around the age of 25, several ancient sources suggesting a shipwreck. He left Rome, maybe sailing east to Asia Minor, and never returned. Like John Keats, Terence probably died at the age of 25, having led a short, prolific, stunningly brilliant career. Just how brilliant, I would like you to now see. So let’s put a copy of Terence’s final play and masterpiece on our desk, that’s The Brothers, and open it up to the introduction.[music]

The Situation of The Brothers

Terence’s The Brothers, staged in 160 BCE, is ultimately a play about how children should be raised. Now, my dad once told me that a general rule to follow in conversations with extended family and coworkers is to tread lightly around the topics of religion, and politics, and parenting. These topics can cause almost instantaneous animosities to bubble to the surface, and the third one – parenting, or conversations about how we should raise our children – the subject of parenting can cause serious disagreements between even the most mild-mannered of us, particularly as we grow older, have kids, and begin to have opinions on how children ought to be raised, and educated, and so forth.So – for the sake of quickly understanding the thematic core of Terence’s play The Brothers – imagine this. Imagine you have a little brother. And imagine that you also have two sons. For whatever reason, financial expedience or because your brother can’t have children or something like that – for whatever reason, you allow your brother to adopt your older son, although you keep your younger son and raise him as your own. Now this situation is inevitably going to be challenging for you, because your younger brother is going to have different ideas about how to raise a child, and you have to watch your older son grow up raised by someone else. And this situation would become even more volatile if you were to grow increasingly apart from your younger brother as you got older. Imagine – again just for the purposes of understanding this play – that as you became older you increasingly took to country life, became a bit stodgy and conservative and set in your ways – and you raised your younger son according to this ideology. Your younger brother, however – the one who had long ago adopted your older son – your younger brother moved to the city and was quite the opposite of you – liberal, fond of easy living, morally lax, and he raised your older son according to be a rather lazy, entitled urbanite. You can imagine that if you ever did see your younger brother, you’d have a lot of issues to work out with him – not only the differences between your rustic conservativism and his metropolitan liberalism, but also how his lifestyle had affected your son whom he had adopted.

So, that’s the scenario of Terence’s 160 BCE play The Brothers – a pair of elder brothers, and a pair of younger brothers, a rather problematic adoption, and a good deal of debating about the best way to raise a kid.13 The elder brother – the conservative, countrified one – his name is Demea. He is the funniest and most memorable character in the play, and although his provincial outlook and salty minimalism are often mocked, the old farmer Demea eventually emerges as a very likable, and very intelligent man. Old rural Demea’s younger metropolitan brother is called Micio. Micio has adopted old Demea’s eldest son, Aeschinus, and the question of how Aeschinus is to be raised is at the center of the play. And finally, back on the farm is old Demea’s younger son, Ctesipho. Ctesipho, wholesome rural youth, the morally pure younger brother, protected from the vices of the city by his father Demea’s farm. At least, that’s what old Demea thinks at the outset of the play. Both of the older brothers, Demea and Micio, as the play progresses, begin to learn that no matter how they’ve tried to raise their sons, the two boys have minds of their own.

Now that you know the central situation on which The Brothers is anchored – that it’s a play about parenting, and about the country versus the city, we should open up our Oxford edition, translated by Peter Brown and first published in 2006, and hear Terence’s prologue. [music]

Terence’s Artistic Expositions and the Prologue to The Brothers

The Prologue to The Brothers, like the prologues to all of Terence’s plays, is a short artistic manifesto spoken by one of the play’s actors – a sort of salvo against criticisms that have been lodged against Terence in the past. Terence’s prologues are one of his theatrical innovations. In Plautus, whose plays Terence knew, following the tradition of New Comedy, a divine or semidivine being, or just a prologue speaker, performs the prologue, telling you what you need to know to understand the action that’s about to unfold. Last time, we saw the star Arcturus introduce the action of Plautus’ play The Rope. Terence doesn’t do this. Rather than putting plot and character exposition into his prologues, Terence takes the gutsy and self-conscious step of talking about himself, and his artistry, in each of his prologues. And so in the opening of Terence’s final play The Brothers, Terence takes issue with some charges that that have been leveled against him.To give you a feel for how this self-defensive artistic manifesto sounds, it begins in the Peter Brown translation, with the words, “Since the author has observed that his writings are subjected to scrutiny by hostile men, and that his enemies are casting aspersions on the play that we’re about to act, he will give evidence on his own behalf, you will be the judges of whether what he’s done should be praised or criticized.”14 The actor speaking on Terence’s behalf goes on to emphasize that the play he’s about to stage rescues a lost scene from a playwright named Diphilus, and integrates this scene into the plot of The Brothers in a word for word translation.15 The play, then, Terence makes clear, will be an example of what Latin literary historians called contaminatio, or the adaptation of multiple literary works into a single new one. Next, Terence answers the weighty accusation that he has received aristocratic help in the writing of his plays. Terence says that he doesn’t think this is a criticism it all – if his plays seem to bear the traces of patrician assistance, then he’s even prouder of his creations.

With these self-defensive maneuverings out of the way, the actor voicing the prologue announces that the play’s opening conversation will reveal all the exposition necessary in order to understand the play. So, let’s hear the story of Terence’s nearly 2,200 year old comedy, The Brothers. [music]

Micio Offers Exposition

Onstage, there stood two houses. One of these was the house of an old widow who lived with her daughter. And the other was the house of a 64-year-old bachelor, a man who, avoiding the pressures of married life, had overall taken a leisurely path. This man – this 64-year-old unmarried urbanite – was called Micio. Micio is the first character onstage in Terence’s play The Brothers, and it is Micio who offers us a great deal of exposition into the situation at hand.16It was close to dawn in the city of Athens, and as urbane old Micio came out of his house, he appeared fretful. He was looking for his son, a young man named Aeschinus. Aeschinus had gone to a dinner party the previous evening, and Aeschinus hadn’t yet returned home. Now, just as Terence’s prologue has promised, old Micio offers us an exposition into the slightly confusing familial situation at the heart of The Brothers. I know I explained it above, but let’s hear Micio’s own words, describing his brother and his two nephews, one of whom he’s adopted as a son. After explaining that his son hasn’t returned home after a night out, Micio explains, and I’m quoting the Oxford Peter Brown translation,

What’s more, this boy is not my son but my but my brother [Demea’s] son; and [my brother Demea] has had a different style of living ever since we were young men. I have pursued this gentle city life of leisure, and as for what some people think a blessing – a wife – I’ve never had one. [My brother Demea] has been the opposite in all the following respects: [Demea has] spent his life on the farm; [Demea] always lived a frugal and hard existence; [Demea] married; two sons were born. Of them, I [, Micio,] adopted this elder one [, Aeschinus,]; I’ve brought him up from childhood; I’ve regarded [Aeschinus] as my own, and loved him accordingly. That’s what I take delight in; that’s the one thing that’s dear to me. I do my best to make him feel the same towards me: I give him things; I overlook things; I don’t feel the need to exercise my authority all the time. (264)

Micio went on, in this opening monologue of the play, to talk more about his parenting philosophy. He said he knew his adopted son Aeschinus enjoyed a bit of drinking, and sleeping around. But Micio said it was best to be honest and communicative with Aeschinus, so that there was no duplicity between them. Old rustic Demea, Micio’s brother, endlessly criticized the way Micio was raising Aeschinus, telling Micio there was no need to buy a young man fine clothes and finance his affairs and drinking habits. Micio said he and his brother had a central disagreement about parenting – old Demea believed in compulsion and force. Micio believed that force on the part of the parent only led to resentment and duplicity on the part of the child. As Micio put it, “This is the mark of a father, to get his son into the habit of acting rightly of his own accord rather than through fear of another; that’s the difference between a father and a master. If a man can’t do that, he should admit that he doesn’t know how to rule over his children” (265). And just as he finished this thought, Micio saw his brother Demea coming across the stage toward him. [music]

Micio and Demea Talk of Demea’s Sons

Old provincial Demea was not in a good mood. He was old enough to walk with a cane, and seeing his younger brother, Demea hurried over to Micio as quickly as he could. Demea said they needed to talk. Their son – Demea’s biological son and Micio’s adopted one – their son Aeschinus had really done it this time. He had broken his way into a man’s house, beaten up everyone inside, and kidnapped a woman. This, old Demea said, was going way too far. Aeschinus had been spared the rod, the old farmer said, and ended up a reprehensible man. Demea’s other son, however, the old clodhopper insisted, was a model of agrarian virtue.Micio was not persuaded by this verbal assault on his parenting style. Micio told his older brother that he and Demea themselves probably would have been liable to just the same sorts of turpitude if they’d had the opportunity. Rather than apologizing for Aeschinus’ wayward behavior, Micio told old Demea that Demea’s other, younger son should also be allowed to come to the city and indulge in his wayward passions. Old Demea began a rebuttal, but Micio interrupted him. Micio said that he had adopted Aeschinus, he was responsible for Aeschinus, and would meet all the expenses of Aeschinus’ indiscretions.

This was naturally difficult for Demea to stomach. Demea said, with eloquence and feeling, that it was impossible for him not to care about the moral ruination of his eldest son, and yet, caving into his powerlessness in the situation, the old farmer said he’d do his best to raise his remaining son to be a good man. With these words, Demea left his brother alone onstage.

Micio, upon the departure of his rustic brother, didn’t feel any sense of triumph. Micio admitted that he really was upset with young Aeschinus’ behavior, and yet he hadn’t wanted old Demea to see this. Trying to deal with things one at a time, the urbanite Micio resolved to find his errant adopted son, and left the stage with a heavy heart. Just then, a motley group of individuals hurried onto the stage.

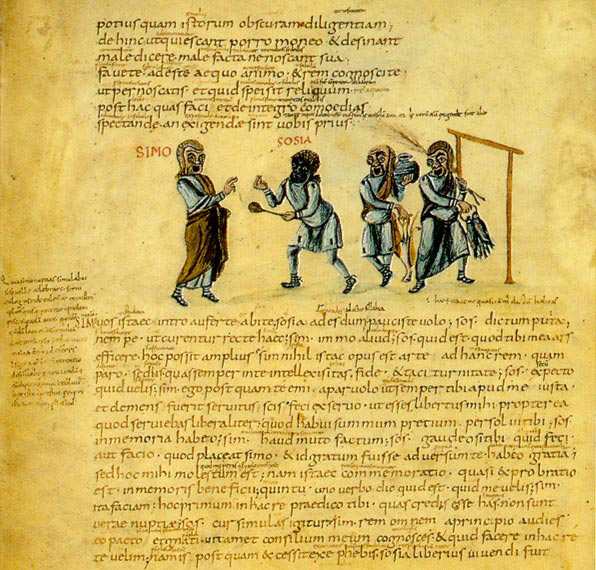

In front of the pack was the morally wayward older son Aeschinus, in the company of a prostitute. With Aeschinus were four of Micio’s household slaves, and behind him was a pimp. The pimp was in the midst of castigating Aeschinus. Aeschinus had abducted his prostitute, and so the pimp was seeking to get the girl back. When the pimp, whose name was Sannio, made a move to snatch the girl away from Aeschinus, Aeschinus had one of his slaves punch the pimp, and then punch him again.

Having shown that he was not above violence, Aeschinus told the prostitute to go into his house (also his adopted father Micio’s house). The pimp was incredulous. The pimp had paid money for the prostitute. He owned her. And Aeschinus had just stolen her. Sannio the pimp, trying to reason with the violent young man, said, “I’m a pimp, I admit it, the universal destruction of young men, a double-crossing disaster for them! All the same, I haven’t caused you any wrong!” (270). The pimp said he’d paid a lot of silver for the prostitute, and wasn’t interested in selling her.

Aeschinus said he wasn’t going to buy the prostitute. The prostitute, said Aeschinus, was a free-born woman, and thus ineligible for slavery! Still, Aeschinus said, he’d pay the pimp the girl’s purchasing price and become her new owner. Aeschinus went in, and Sannio the pimp grumbled about being treated dishonestly by his customers. A moment later Sannio the pimp realized he had been outsmarted. Aeschinus and his slaves knew that Sannio was soon embarking on a business trip to Cyprus. Sannio couldn’t postpone the trip, and by the time he got back the case of his stolen prostitute would be past settlement in the courts. Still, the pimp was flabbergasted. Aeschinus, he said, had beaten him badly and knocked out his teeth, and now Aeschinus was going to cheat him? Sannio the pimp begged Aeschinus’ slave to at least do something to help him recover the funds for his stolen prostitute, and just as the two men were negotiating an agreement, a new character appeared onstage. [music]

Ctesipho Emerges as a Profligate

So, we’ve met urbane Micio, Micio rural brother Demea, and Demea’s unscrupulous older son Aeschinus. Now it’s time to meet Demea’s younger son, Ctesipho. Now, why would Ctesipho come to see his older brother at this crucial moment? Had he been watching his urban counterpart slide into a morass of depravity, and come to counsel wayward Aeschinus, and return him to the path of pastoral probity? Had young Ctesipho come to rescue his older brother from sin and damnation?No. Actually. Ctesipho had come to thank Aeschinus. Because the prostitute that Aeschinus had just stolen from the pimp was young Ctesipho’s girlfriend. [sigh] So much for old man Demea’s countrified ethics of hard work and virtue. So, far from upbraiding his older brother for immorality, Ctesipho announced, “Oh my brother, my brother, how can I praise you now? I know for an absolute fact that however extravagantly I put it I shall never say anything to match your merit!” (272). At moments like this you can see why Christian writers over the ages were fascinated by Terence, though with some reservations.17 Anyway, after praising his brother’s theft of the prostitute, Ctesipho greeted his older brother Aeschinus warmly. Urbane Aeschinus told his countrified little brother to go and enjoy a reunion with the stolen prostitute, but first Ctesipho asked for the pimp Sannio to be paid. Otherwise, it might come out that he had taken a lover, and if rural old Demea found out, it would be trouble for everyone. With payment to the pimp arranged, Ctesipho said it was high time for a party. [music]

The House of the Widow Sostrata

Now there are a couple more characters we need to meet. The house of Micio, as you just heard, was about to spend the afternoon carousing. But nearby, at another house, something very serious was happening. Adjacent to the home of Micio in Athens was the house of a widow named Sostrata. And Sostrata’s daughter was having a baby. And the father of this baby was none other than Aeschinus, the adopted son of the neighbor Micio. Aeschinus had raped Sostrata’s daughter – her name was Pamphila, nine months before, and the baby was due that very day.On the one hand, the revelation that Aeschinus had raped the helpless neighbor girl seems to cast an even deeper shadow onto the morality of his character. Over the course of the play so far he’s been guilty of breaking and entering, assault, property theft, and now rape. But on the other hand, it wasn’t an absolutely bleak and hopeless day over at the neighboring house of the old widow Sostrata. Sostrata’s nursemaid revealed that Aeschinus had been coming over every day to visit his rape victim over the course of her pregnancy, and that he was in love with her. Further, Sostrata emphasized that Aeschinus, rapist that he was, was their best bet for survival, since he loved young Pamphila, and he was wealthy, and could rescue their household from economic squalor.

Not everyone in the old widow Sostrata’s household was delighted that the girl was giving birth that day. One of Sostrata’s slaves, a man named Geta, expressed great wrath at the household of Micio, and particularly Aeschinus himself. The slave Geta was so angry that he could scarcely speak, because he’d found something out. Sostrata tried to get her fuming slave to spill the beans, and finally, he collected himself long enough to explain what was happening. The neighbor boy Aeschinus, said the slave of the old widow Sostrata, had done right by his rape victim so far, visiting her over the course of her pregnancy and, we assume, promising a marital union. But, said Sostrata’s slave, Aeschinus had betrayed them all! Aeschinus had stolen a beautiful prostitute, and thus had made pregnant young Pamphila an abandoned woman, and condemned the entire household of Sostrata into economic ruination!

Okay, the plot is getting a little thick here, particularly in podcast form, so let’s clarify and recap. At the start of this play, the city brother, Aeschinus, stole a prostitute for the country brother, Ctesipho. At this point in the play – where we are now – next door, the city brother Aeschinus’ rape victim – whom he loves and is dedicated to – is having his baby. However, a slave who works at the neighbor girl’s house has seen the city brother Aeschinus steal the prostitute for the country brother, Ctesipho. And this slave has just told the neighbor girl’s mother that Aeschinus has stolen the prostitute for himself. We, the audience, know that this is not why Aeschinus stole the prostitute, and thus it’s hard not to feel sorry for the neighbor girl Pamphila, and her widowed mother Sostrata, because these economically disadvantaged women were counting on Pamphila ending up with Aeschinus.

So, under the false presumption that pregnant young Pamphila was soon to be abandoned, the household of the widow Sostrata began discussing what to do. Old Sostrata, somewhat to everyone’s consternation, proposed making Aeschinus’ crimes public. She sent a slave to go and talk to her departed husband’s best friend to try and get some help. [music]

The Older Brothers Learn More of the Doings of the Younger Brothers

We’ve just heard about what the younger generation of brothers were up to – the city brother Aeschinus, who has impregnated the poor neighbor girl, has just stolen a prostitute for his rural counterpart Ctesipho. With this plot set in motion, the playwright Terence moves the action back to the older pair of brothers – particularly the old farmer Demea.Demea, as it turns out, has found out about his supposedly virtuous younger son’s union with a prostitute. And even worse, as old Demea emerged onstage he learned that his brother Micio had paid for the purchase of the stolen prostitute and thus sanctioned the whole affair. Demea lamented that his younger son Ctesipho would fall into financial ruination and have to serve as a soldier in order to support himself. Yet in the midst of Demea’s grieving about both sons falling into moral murkiness, the old man got some good news. Micio’s slave told the old farmer not to worry – for in actuality young Ctesipho had behaved with perfect moral conduct. Micio’s slave, lying through his teeth, told old Demea that Demea’s cherished younger son had actually berated Aeschinus for Aeschinus’ indecency – and thus that young Ctesipho was still as morally upright as ever. Poor old Demea ate these lies right up, swelling with pride and saying, “Heaven preserve [my younger son Ctesipho]! He’s a chip off the old block!” (279).

Micio’s slave, who had entirely fooled old Demea, convinced the farmer to head back home. But just as Demea was on the verge of leaving town, Demea caught sight of an old friend. This old friend was named Hegio. Hegio was not only old Demea’s friend. Hegio had also been best friends with the widow Sostrata’s dead husband, and poor Sostrata, worried about her pregnant and abandoned daughter, had sent Hegio out to try and find some reprieve for her household.

Now, at this point, old Demea knew that that his oldest son had stolen a prostitute via a violent act of breaking and entering. But Demea’s old friend Hegio, once the two old men had greeted each other, told Demea an even more awful truth about Demea’s oldest son. Demea was shocked to learn that Aeschinus had raped the young daughter of their mutual friend – the widow Sostrata’s departed husband. This was dreadful news for provincial old Demea, who took pride in his goodness and rectitude. But Hegio offered Demea a momentary consolation. As Hegio says in the Peter Brown translation,

At least you can tolerate that, one way or another, [Aeschinus] was led on by the night, by passion, by wine, by youthful spirits; it’s only human. When he realized what he’d done, he went to the girl’s mother entirely on his own initiative: he wept, he begged, he implored her; he gave his word, he swore he’d marry her. They forgave him; they kept it quiet; they trusted him. (282)

All this, old Demea agreed, was at least some consolation for the ugly crime. But, Hegio added, Aeschinus had now done something almost as bad as the initial rape. Aeschinus was abandoning the poor girl who counted on him – abandoning her for the prostitute he’d stolen.

Hegio said that the abandonment was more than he could accept. And at just that moment, the neighbor girl Pamphila cried out in the pain of childbirth. Hegio looked at Demea and said that the poor girl’s mother was a widow – her father had been a great friend of Hegio’s. Hegio said he would seek justice for poor young Pamphila. And in a short, memorable speech, Hegio said,

[S]ee that you reflect on this, Demea: people like you have a very easy life, and you’re particularly powerful, wealthy, lucky, and well born, so it’s particularly important that you should give fair recognition to fair dealing, if you want to be regarded as honest men. (283)

Having heard this counsel, which he believed in already, Demea went off to find his brother Micio to get the other man’s help with the crisis. Hegio, loyal to his dead friend’s widow, went briefly into her house to see Pamphila, and gently counseled the old widow to have heart. And thus with an air of moral anxiety and shock at what the younger generation was doing, old Hegio left the stage. [music]

Micio Confronts Aeschinus

Now in an earlier scene, Micio’s slave had played a trick on old rural Demea. This intelligent, perceptive slave, whose name was Syrus, had praised Demea’s parenting, and lied to Demea about the righteousness of Demea’s son, and convinced Demea to head back to his farm. The scene we’re about to watch will be another moment of the slave Syrus talking with, and manipulating gullible old Demea.

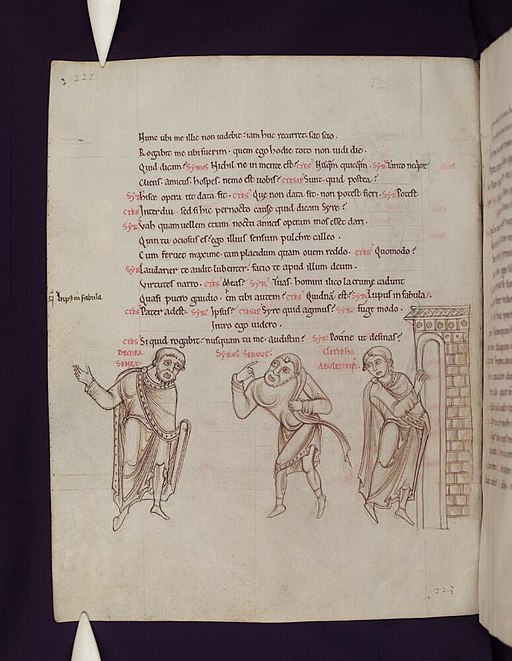

A statue of a Roman actor playing a slave, circa first century CE. Slaves are fixtures of Roman plays like Terence’s The Brothers.

Sure enough, in the conversation that ensued between the crafty slave Syrus and old Demea, Syrus convinced Demea that, first off, Demea’s younger son Ctesipho was morally spotless, that this young Ctesipho had heroically assaulted and badgered certain members of the house of Micio for their immorality, and third, that Demea himself ought to head out to find his supposedly righteous young son. Gullible old Demea went off to do just this.

With the stage empty again, Aeschinus, whom we haven’t seen in a little while, went over to the house of Sostrata and began a long monologue. Aeschinus, the older, supposedly morally reprehensible son of Demea, said he was distraught. His fiancé, Pamphila – at that very moment having his baby – believed the worst of him. Pamphila, her widowed mother Sostrata, and their entire household believed that Aeschinus had stolen the prostitute for himself, and not his younger brother. The conundrum was, Aeschinus said, he couldn’t have it come out that he had stolen her for young Ctesipho – because this would ruin Ctesipho’s reputation. Still, feeling like he had to say something, Aeschinus hesitantly knocked on the widow Sostrata’s door. Just then, Micio was walking out.

Now, all the time that this scene has been taking place, unbeknownst to Aeschinus, Aeschinus’ adopted father Micio was in the widow’s house. Micio knew everything that was going on, and had been in the midst of assuring Sostrata’s household of his son’s loyalty. But, once Micio saw his son just outside of Sostrata’s house, Micio decided to play a trick on Aeschinus. Because – uh – the plot isn’t already sufficiently complex. Micio told Aeschinus that Aeschinus’ beloved Pamphila was going to be married off to a man from the island of Miletus. Aeschinus went through a whole spectrum of emotions upon hearing this, but eventually grief took over, and he found himself weeping in front of his adopted father. He began to confess his story to Micio, but Micio interrupted him, and the following interchange took place.

Aeschinus, I’ve heard the whole story; [said Micio,] I know everything. I love you, and that’s why I particularly care about your behavior.

[And Aeschinus said,] I hope I’ll deserve your love as long as you live, dad, and I’m extremely upset that I’ve behaved so badly; I’m ashamed to stand before you.

I can well believe it: [said Micio,] I know your open-hearted spirit. But I’m afraid you’re just too thoughtless. After all, what city do you think you’re living in? You raped a girl, when it was against the law for you to lay a finger on her. That was your first wrong, and a great one . . . You’ve been treacherous to yourself, to the poor girl . . .as treacherous as you could be. (290-1)

Micio, however, didn’t just condemn his son for poor conduct. Instead, Micio told Aeschinus, after a long speech, that Aeschinus could marry the neighbor girl Pamphila. Aeschinus was stunned and speechless with gratitude for a moment – but a moment later he said that he loved Micio more than his own eyes – really just as much as he loved his fiancé – that his father was a much better man than he was. After Micio went in to begin arrangements for the wedding, Aeschinus remained on stage, almost unable to describe the extent of his father’s goodness and generosity. And, decisively vindicating Micio’s earlier statement hands-off about parenting, Aeschinus said,

What’s happening here? Is this what’s meant by being a father, or by being a son? If he were my brother or my best friend, what more could he do to fall in with my wishes? Shouldn’t I love him? Shouldn’t I hug him to my breast? Well, shouldn’t I? In fact he’s so obliging he makes me feel quite worried that I might do something unconsciously against his wishes. (292)

And with these reverent words about his forgiving father, Aeschinus went into their house. [music]

Demea Confronts Micio

With that plot line tied up, Terence moves to tie up another. Old rural Demea had been wandering around Athens looking for Micio. And, grumbling about his fruitless search, Demea came down the street and was surprised to see Micio come out of his house. Demea prepared to drop dreadful news on Micio – news about an innocent neighbor girl raped, about a prostitute purchased, and other lurid details, but Micio already knew about all of it. Micio told his older brother his plan. Aeschinus would marry the compromised neighbor girl Pamphila. She had, as it turned out, just given birth to a son. No, Micio admitted when asked, poor Pamphila did not have a dowry. When asked if he were pleased about marrying his adopted son off to a girl with no dowry, Micio shook his head and he voiced one of my favorite lines in classical comedy.No, [said Micio,] if I could change it; as it is, since I can’t, I bear it with equanimity. The life of man is like a game of dice: if the throw doesn’t give you the number you most need, you have to use your skill to make the best of the number it does happen to give you. (293)

Micio’s thought was eloquent, but it still didn’t quell his old brother Demea’s anger. Old Demea knew that the marriage wasn’t the only thing going on – what was also unbelievable was that Micio had spent twenty pieces of silver buying a prostitute to live in his household.

Micio went over to the widow Sostrata’s house – the house of his soon-to-be daughter-in-law, and a moment later old Demea found himself in conversation with the clever slave Syrus. Syrus had tricked old Demea twice, and at this point, Syrus was for whatever reason rather drunk, and he and another slave accidentally let it slip that old Demea’s younger son was actually in Micio’s house at that very moment. Demea was shocked – at this point he still had no idea that his younger son was also morally compromised, and he stormed into Micio’s house to investigate.

A moment later, as Micio emerged from the widow Sostrata’s house next door, Demea burst out of his brother’s house. Demea now knew everything – that his younger son was as experienced with sex and drinking as his older son, that the prostitute had been purchased for the supposedly spotless young Ctesipho. And old Demea assaulted his younger brother with verbal abuse. Hadn’t giving Micio one of his sons been enough? Demea asked. Had it really been necessary for Micio to corrupt both of his boys? Yet Micio, who takes on an increasing tone of confidence as he deals with, and accepts the tumult caused by his adopted son, met his brother’s accusations without flinching.

Micio said Demea didn’t need to worry about money. He’d take care of both boys financially, as fortune had been kind to him. Nothing that was happening would affect Demea financially, and Demea could continue to pinch pennies and moralize as he always had. Micio added that the two boys, in spite of their bad decisions, had good hearts and were quite capable of moral behavior, and, though Demea remonstrated, Micio said Demea ought to take Ctesipho’s girlfriend back to the farm to live with them. Demea was hardly silenced by all of this seasoned advice, but nonetheless eventually the two brothers wore one another out, and they went into Micio’s house to prepare for the impending wedding. [music]

A Change Comes Over Demea

The stage was empty for a while, and the audience was left to presume that inside the house of Micio everyone was readjusting to the dramatically changing circumstances wrought by the eventful day. Aeschinus had been awed at his adopted father’s unexpected generosity. Micio had been startled to learn about how fast his nephew and adopted son were growing up, and had been compelled to deal with their changing behavior. The whole household of the widow Sostrata had gone from hopeful to despairing to hopeful once more over the course of a single day. And soon, Micio’s door opened, and old Demea emerged, alone, and offered a speech to the audience. I’m going to quote a long piece of the Peter Brown translation, first published by Oxford University Press in 2006 – and I encourage you to pick up a copy of this edition. This is a pivotal monologue by the old farmer Demea, about his psychological experience over the course of the play.No one [said old Demea,] has ever done his sums so well in the account book of his life that events, time, and experience don’t always bring him something new, something to learn from. The result is that you don’t know what you thought you knew, and experience teaches you to reject what you thought most important for yourself. That’s what has happened to me now: that harsh life that I have lived so far I now abandon when I have almost run its course. Why do I do that? Events themselves have taught me that nothing is better than for a man to be obliging and kind. Anyone can easily see that’s true from me and my brother. He has always spent his life in a relaxed way, dining out, being kind and gentle, attacking no one to his face, with a smile for everyone . . . Everyone speaks well of him, and everyone’s fond of him. I, that rustic, fierce, severe, mean, aggressive, close-fisted man, got married: what misery I’ve seen as a result! Sons were born: that meant more worry . . . Now, at the end of my life, this is the return I get from them for my hard work: hatred! He, [Micio,] without doing a stroke of work, gets all the advantages of fatherhood: they love him, they avoid me; they trust him with all their plans; they’re fond of him, they both spend their time with him, and they leave me deserted. (297-8)

Demea’s long speech, however, wasn’t a bitter lamentation from end to end. In fact, the old farmer ended on a note of hope and resolution. He said that if his brother wanted to be “charming and generous” (298), Demea himself could certainly try and do the same thing. Acting on his new resolution, Demea saw the clever slave Syrus emerge from Micio’s house. Demea greeted the slave Syrus and told him that, although Syrus was a slave, he had the qualities of a free man. Syrus, surprised at the old farmer’s sudden generosity, thanked him. Demea was similarly kind to a slave of Sostrata’s household, telling the man he’d been exemplary in loyalty to his family, and this second slave thanked Demea and said that the old farmer was a good person, too.

Aeschinus came out and told his father he was worried about arrangements for the wedding – there had to be a pipe player, and young Pamphila would have to be brought over, and she’d just given birth. Demea proposed a simple, and strange solution – why not just break down the wall between the widow Sostrata’s house and Micio’s house – they were going to be one household, anyway. Aeschinus loved the idea, called his father wonderful, and Demea was delighted at being complimented by one of his sons.

The newly transformed Demea had another idea. First getting his oldest son Aeschinus on his side, Demea, with some difficulty, proceeded to convince his brother Micio to marry – to marry the widow Sostrata, mother of Aeschinus’ bride-to-be. Micio accepted, and yet still Demea wasn’t through with his sudden burst of generosity. Sostrata’s dead husband’s friend – the man named Hegio, who’d briefly played a role in the play – this man, said old Demea, needed to be taken care of. Demea convinced his brother Micio to give old Hegio a plot of land that Micio owned.

Now, as all these generous acts are carried out at Demea’s behest, Terence is careful to show us that Demea hasn’t suddenly transformed into an angel of goodness. All of these acts of kindness, after all, have to be funded by Micio, and at one point old Demea turned toward the audience and said, “I’m cutting his throat with his own sword!” (302). It’s a violent metaphor, but of course it means that Demea is using his brother’s liberal ethics to run down Micio’s seemingly inexhaustible supply of money. As a final stroke of generosity, Demea said that the clever slave Syrus absolutely had to be freed, along with his wife, and even given a parting gift of money, and soon Micio was strong armed into this manumission as well.

Now at this point Micio was thoroughly shocked at his brother’s turnabout, and Micio asked old Demea just what he was up to. Demea explained himself to his family. Demea told Micio that the two boys loved Micio because he was indulgent and acquiescent. And Demea said the boys hated him because, rather than bowing to their every desire, he tried to teach them things that would be useful when they were older. The old farmer said that if they just wanted comfort and indulgence, Micio was their man. But if they wanted to learn how to see the world more clearly, and improve their judgment, and be prepared for adult life, they might still find their biological father useful.

At this, Aeschinus brought up the subject of Ctesipho, and Ctesipho’s prostitute girlfriend who had been purchased for him. Demea – perhaps rolling his eyes, huffing a bit, and shaking his head, said, “I’ll let him keep her – but she’d better be the last!” And that’s the end. [music]

Salient Literary Elements of The Brothers

So that was the story of Terence’s The Brothers. If you boil this play down to its simplest structural elements, it resembles both the Greek New Comedy that came before it, and later works of Renaissance romantic comedy that came along after it. There are bourgeois youths running around and falling in love, a damsel in distress who’s rescued at the end, a clever slave and a duped pimp, an inevitable double marriage, and other Lego blocks that have been getting combined and recombined in theatrical comedy in various ways since the late 300s BCE. You have all of these elemental components in Terence’s The Brothers, but you also have some other stuff.

An add for a 1917 production of Moliere’s School for Husbands (1661), a play inspired by Terence’s The Brothers.

In the play that we just read, almost every character suffers from false assumptions that we, the audience, understand are false. Old Demea spends most of the play believing that one of his sons is corrupt and the other morally upright. The entire household of the widow Sostrata spends most of the play under the assumption that wealthy young Aeschinus is going to abandon poor young mistreated Pamphila. Aeschinus is duped by his adopted father Micio into believing that his beloved Pamphila is leaving him. Even the comparatively well-informed Micio spends the beginning of the play flummoxed by his son’s absence. These secrets, and the general dual intertwined story of the households of Micio and Sostrata swell throughout the rising action of Terence’s play. We wait for the secrets to disentangle, but they continue to compound, and this is one of the most wonderful features of Terence’s plays. He didn’t invent dramatic irony, nor present some final and definitive example of it. But Terence knew that when an audience knows a secret, and characters don’t, that audience gets very curious about what’s going to happen when all the facts are laid bare.

Dramatic irony and double plots are important elements of Terence’s craft as a dramatist, but perhaps the most remarkable element of Terence from a purely literary perspective is his use of dynamic characterization. Now, this is English 101 stuff, so the literature veterans out there will have to forgive me for a moment, but in Introduction to Literature classes we contrast flat or static characters with round or dynamic characters. Flat or static characters are often stock characters – a town drunk, a villainous seducer, a knight in shining armor, a parsimonious old man, and so forth, and flat or stock characters don’t change much over the course of a narrative. Round or dynamic characters, on the other hand, are multi-dimensional and evolve over the course of a narrative. In the play we just read, old Demea, far from being a set in stone rural miser, learns from watching his sons interact with his brother, adjusts his mode of conduct, and as the play comes to its conclusion, Demea’s adaptability and perceptiveness lead him to gently but definitively assert that he still has an indispensible role to play in his own family.

The closing line of The Brothers shows Demea finally accepting that his prized younger son has a mistress – the old farmer growls, “I’ll let him keep her – but she’d better be the last!” – and in this moment Demea’s grouchy, begrudging, but ultimately kindly acceptance of his sons’ behavior shows us how much he has changed. Demea might have ended up as powerless and irrelevant as the stingy curmudgeon Knemon – the main character of Menander’s Old Cantankerous, which Terence probably read just as we did a few shows ago, but as The Brothers comes to a close, we have a sense that Demea is a good man and that his self-discipline and virtue will help anchor his otherwise erratic and hedonistic family.18

Demea, in fact, seems to have learned specifically from his brother Micio, who told him earlier in the play, “The life of man is like a game of dice: if the throw doesn’t give you the number you most need, you have to use your skill to make the best of the number it does happen to give you” (293). This is, perhaps, the creed not only of Terence’s more dynamic characters, but of all of us who have changed careers, coped with unexpected traumas, given up dreams, and in all other fashions surfed the strange and unruly wave of human existence. The two pairs of brothers in Terence’s final play decide, ultimately, that while they won’t give up their individuality altogether, nor the prerogatives that make them who they are, they will accept the hands they’ve been dealt – and more than that – that they will find joy and fulfillment in doing so. [music]

Adoption in Republican Rome

The Brothers is, like all of Terence’s plays, a literarily inventive piece of work with a dual plot, plenty of dramatic irony, and most importantly, a particularly touching dash of dynamic characterization. Now that we’ve talked about the literary features of The Brothers, let’s delve a bit more into the history behind this play – both some general elements of Ancient Roman culture that I think will help us understand the play, as well as some history behind its first staging.At the center of The Brothers is an adoption. In the lives of Terence, and Terence’s friends, and moreover Ancient Roman society as a whole – adoption was a much more pervasive and integral cornerstone of society – particularly aristocratic society – than it is for us today. Terence’s friend and possibly patron Scipio Aemilianus was the adopted grandson of the great general Scipio Africanus.19 Scipio Aemelianus’ brother also became the adopted grandson of a prominent general from the Second Punic War.20 Whether Terence himself was ever formally adopted by the senator who purchased and freed him – Terentius Lucanus – or the poet Caecilius who helped further his reputation, or one of the Scipionae circle, we don’t know, but it’s possible that the handsome, talented ex-slave subsisted as something like an adopted brother to his close friend Scipio Aemelianus.

Now, a bit of background on Roman culture – and this is fascinating stuff if you haven’t heard it before. Last time we talked a bit about the practice of infant exposure in the Greco-Roman world – that practice of leaving unwanted babies out to be picked up by passerby, or simply to perish. Another practice common in Roman culture was the practice of strategic, socially advantageous adoptions. As historian Paul Veyne writes, “[O]ne gave a child for adoption as one might give a daughter in marriage, particularly a ‘good’ marriage . . . Adoption could prevent a family line from dying out . . . Everything that could be had through marriage could also be had through adoption.”21 Far from being loved for their genetic lineage to their parents, Veyne describes Roman children – especially patrician children “moved about like pawns on the chessboard of wealth and power.”22

The Julio-Claudian family tree. Note the dotted lines, signifying adoptions, in particularly significant places! Image by Dominic Byrd-McDevitt.

Once, when the emperor Galba declared Lucius Calpernius Piso his son and legal heir, the fate of the empire seemed for a moment to hinge on the mechanics of an adoption. But actually, all of Roman history after Julius Caesar was determined by an adoption – Caesar’s adoption of his great nephew, a young man named Gaius Octavianus, who became the first emperor of Rome in 27 BCE and assumed the title of Augustus.These high profile imperial adoptions took place long after the life of Terence, but even during Terence’s life the mechanics of adoption were used to propel familial ambitions, jumpstart the careers of young men, and of course to cement friendships with legal bonds. To state the obvious, then, in Terence’s play The Brothers, while Aeschinus’ adoption by his uncle Micio seems a bit odd by modern standards, this adoption, and the resulting bickering about child rearing between biological and adopted parents, wouldn’t have raised any eyebrows. These days, we send our kids to college to be refined and prepared for entrance into society. And in Republican Rome, while patrician youths were certainly educated in schools and gymnasiums, they were also, particularly if they were up and coming young men, given in adoptions that would be advantageous to them.

There is some hard-headed logic to the Roman practice of giving up children for adoption. In any era, when conducted rightly, adoption is an unsentimental way of setting a young person up for success that would otherwise not be available to him. While Roman adoption helped certain young people up the social ladder, it had a broader effect on Roman society as a whole. The widespread practice of adoption actually helped the aristocracy and executive leadership of Rome be more meritocratic. If you were a rich, powerful patrician, you were not forced to rely on the coin toss of whether or not your own children would be suited to a position of power. If you happened to see some brilliant and competent young person eligible for adoption, you could simply adopt that person and rely on his or her existent talents to further your family’s fortunes or ambitions. Sometimes, people were even adopted at rather advanced ages. This mechanism of power transferring due to competence, rather than power transferring due to genetics, gave Rome some of its most successful leadership, even at the imperial level. Four of the Five Good Emperors, between 96-180 CE, who included Trajan, Hadrian, Antoninus Pius, and Marcus Aurelius, were all chosen based on personal abilities, rather than bloodline.

Let’s get back to the subject of Terence. Terence was probably one of a flood tide of North African slaves transplanted into Roman society in the early 200s BCE. In the society in which Terence found himself, the arrangements that existed between parents and children were more fluid than the ones that exist in our society. We, unlike the Romans, have in our culture broad moral and institutional biases favoring the genetically linked nuclear family. While heritage and ancestry were always important in Rome, too, the mechanisms of exposure and adoption allowed for family trees to be sawed off and grafted back together according to family patriarchs, in ways which did not survive the end of antiquity. The mechanisms of adoption, to a slave like Terence, or someone lowborn like Plautus, for that matter – the mechanisms of adoption, to the very lowest rung of the social ladder, were full of opportunity. Before the golden age of Roman literature began in the middle part of the last century BCE, “many of the literary figures [active] were of low birth.”23 This is a peculiar moment in literary history, by the way, and a century and a half later it was over, but during Terence’s lifetime, rather than literature being the exclusive purview of the landed elites, literature was the jurisdiction of whoever had the linguistic background and guts to write a play, get it up on a stage, and compete with strippers and gladiators. Now oratory and historiography were, from the beginning, the domain of wealthier men, but stage shows were a unique opportunity for talented writers of modest backgrounds to begin ascending the Roman social ladder. The best of these often lowborn innovators, with a few strokes of luck, might be scooped up into the boughs of a patrician family tree, and become associates of the rich and powerful, as Terence did.

Okay. We’ve talked about the social engineering of Republican Rome, and how it affected the life and career of Terence. The practice of adoption is prominently featured in Terence’s play, with all of its possibilities and problems. But adoption is actually relevant to Terence’s play The Brothers in a third and equally important way. I want to tell you the story of where and when The Brothers was first staged. [music]

Terence, Scipio, and His Associates

Terence, in the 160s, as I said before, had fallen in with a wealthy man of about his same age named Publius Cornelius Scipio Aemilianus. Let’s focus on this guy for a second – Terence’s dear friend Publius Cornelius Scipio Aemilianus, hereafter, Scipio Aemilianus. Scipio Aemilianus had a role in shaping and abetting Terence’s career – if the prologue of The Brothers is taken seriously, then Aemilianus may have actually helped Terence write some of his plays. Ancient sources describe Scipio Aemilianus as at the center of a literary and intellectual group – his friends included a satirist called Gaius Lucilius, a stoic philosopher named Gaius Laelius, and later, the great historian Polybius.24Speaking some cocktail of Latin, and Greek, and perhaps a dash of Carthaginian from Terence, Scipio Aemilianus’ little circle was a group of cosmopolitan young intellectuals who knew how to goof off and have fun. Over a century after Terence’s death, the poet Horace wrote bemusedly of this bygone literary circle, imagining how “when they vacationed from the crowded public scene, / valiant Scipio and wise and kindly Laelius . . . in their retreats . . . They joked together while the cabbage cooked.”25 In other words, Scipio Aemilianus and his friends, Terence included, fooled around until the cows came home. A patron of Greek culture and an all around golden boy, Scipio Aemilianus was just the sort of person you wanted to have as your friend, and he was evidently fun to hang out with, too.

A bust of the famous general Scipio Africanus, the adopted grandfather of Terence’s friend Scipio Aemilianus.

In all of Roman history, before Rome started gnawing on itself during the civil wars and triumvirates of the first century BCE and became its own worst enemy – in all of Roman history, until maybe the Visigoths, nothing was scarier to Rome than Hannibal of Carthage. Scipio Aemilianus’ adopted grandfather, Scipio Africanus, had defeated this great Carthaginian general, and with his flamboyant looks and maverick ethics, he had become the most famous Roman of his generation. So, lest we get confused amidst a bunch of long ancient Roman names and battles, let’s put this simply. Our writer for today, Terence, was best buddies with a guy whose dad had beat a powerful Greek nemesis to the east, and whose adopted grandpa had beat a terrifying North African nemesis to the west. Through his dear friend Scipio Aemilianus, Terence had connections with the pinnacle of Roman society.

In the year 160 BCE, when The Brothers was first staged, Scipio Aemilianus would have been in the audience, because the play had been commissioned for the funeral games of Scipio Aemilianus’ biological father. As scholar Matthew Leigh writes, “Nowhere do the content and performance context of a Roman comedy enter into so suggestive a relationship as in the case [The Brothers].”26 Unlike Terence’s other comedies, which were staged at a springtime religious festival called the Megalesian Games as well as the autumnal Ludi Romani, Terence’s The Brothers was staged at a very important funeral.

Good old stalwart Lucius Aemilianus Paulus Macedonicus, whose funeral it was, who had done everything a great Roman patrician could do – including giving both of his sons up to socially advantageous adoptions – the man who’d beaten the Macedonians had died, and his two sons put on funeral games for him. A centerpiece of these games, Terence’s play The Brothers has obvious ties to Terence’s friend Scipio Aemilianus and his family. Terence’s friend Scipio Aemilianus, like the play’s central figure Aeschinus, had been raised by two fathers. These two fathers were probably quite different from one another – the biological father was a famous general, and the adopted father the son of a famous general, who never sought a military career for himself. There’s probably more specific parallels between Scipio Aemilianus’ two fathers, and the two fathers in Terence’s play, and I think delving into that subject would probably get us lost pretty quickly in podcast form. For our purposes, I think it will suffice to say that Terence’s play, staged on the occasion of the death of his friend’s biological father, is a play about a biological father, Demea – a man who is tough, smart, morally upright, and ultimately deeply likable. The conclusion of Terence’s funeral play, which indicates that both sorts of fathers – biological and adopted – have a place in a son’s life, is thus a gentle eulogy for his friend Scipio Aemilianus’s father, and a confirmation that Scipio Aemilianus was well raised, whatever disagreements his two fathers might have had. [music]

Micio and Demea as Embodying the Philhellene and Roman Traditionalist

Now we’ve been at it for a while here, but The Brothers is such a rich play that I think we should explore one final aspect of it. That aspect is the way that this play depicts a sea change going on in Republican Roman culture in the first half of the 100s BCE. Rome fought Macedon a number of times between 214 and 148. The decisive victory against Macedon happened in 168 BCE, and the man who beat the Macedonians was the very same man at whose funeral Terence staged The Brothers. Even twenty years before this, though, Rome had defeated the Seleucid Empire in 188 BCE, opening up much of modern-day Turkey to Roman settlement. Essentially, by 168 BCE, modern-day Macedon, as well as much of Turkey belonged to Rome. The entire eastern Mediterranean, accepting Egypt and a few tough confederations in mainland Greece, belonged to Rome – it was, quite literally, a sea change.This sea change brought boatloads of slaves back to the Italian Peninsula, as we’ve been discussing over the last few episodes. But this sea change also brought boatloads of stuff over. Greek stuff. Foods, drinks, textiles, pottery, architectural techniques, weapons, armor, nautical technology, books, livestock, and of course an unprecedented volume of talented Greeks of all castes – aristocrats who observed which way the wind was blowing and moved to the Roman capital, all the way down to educated slaves who believed their knowledge and their capacities as teachers might enable them to make lives for themselves in the west. Greek culture had always been a part of Roman culture, and as we learned a couple of shows ago, the Roman conquest of Magna Graecia and the aftermath of the First Punic War had spurred the first Greco-Roman stage shows in the 240s BCE. But in the 160s, Greeks were leasing Roman apartments and unpacking their bags there at unprecedented volumes. The new tidal wave of Greek culture, which would eventually wash over the whole Italian peninsula, was often met with skepticism and resistance.

Scipio Aemilianus – that’s again Terence’s friend – Scipio Aemilianus’ biological father was one of the skeptics. Old Lucius Aemilianus Paulus Macedonicus, who had subdued Macedon, was a bit iffy about Greek culture suddenly imperializing Roman society, just as Rome was colonizing various Greek-speaking societies. The man for whom The Brothers was staged was a Roman of the tough, leathery old stamp. To people like Lucius Aemilianus Paulus Macedonicus, a bit of cultural comingling was a reasonable thing for Rome to do as it expanded, but the extent to which Greek culture was expanding into even the city of Rome itself, by the 170s and 160s, had become troubling.

The two fathers in Terence’s play The Brothers are often understood as embodying the respective sides of this cultural dichotomy. Old Demea, rural and apart from the city, represents the hidebound, nativist, agricultural, morally disciplined progeny of Rome’s founding fathers. Micio, on the other hand, urban, acquiescent, fond of finery and easy living, is closer to Roman stereotypes about Greeks and those who love Greek culture, or philhellenes. As the 100s BCE deepened, and the Latin traditionalists squared off against the open-minded philhellenes throughout the city of Rome, the growing Republic experienced something like our modern binary between conservative and liberal, with everyone, to some extent, compelled to take a side.

Terence’s friend Scipio Aemilianus was in the middle of this split. His father was the Roman-to-the-bone left fist of the Republic that had knocked out Macedon. But his adopted father, Publius Cornelius Scipio Africanus, son of the great Scipio Africanus, was an intellectual, a priest, a writer, and a lover of Greek culture.27 So Terence’s friend Scipio Aemilianus was right in the middle of that divide between Roman conservatives skeptical about Hellenization, and Roman liberals who embraced it with open arms. Scipio Aemilianus knew Greek intellectuals like the historian Polybius. And he knew Roman salt of the earth conservatives like Cato the Elder, a man who was so obstinate about Roman culture that he refused to speak Greek to Athenians directly, and used an interpreter, instead.28

Knowing what we now do about Terence’s final play, we can of course see that The Brothers is a skilled piece of literary craftsmanship that uses double plots, dramatic irony, and dynamic characterization. But additionally, knowing a bit more about Terence and the circumstances of the play’s first staging, we can see The Brothers as an attempt to set Terence’s friend Scipio Aemilianus at peace – to validate both his adopted and his biological father, to show respect and reverence for the tsunami of Greek culture splashing through port cities and simultaneously the more provincial Romans doubtful about the cultural changes of the mid-100s BCE. Terence’s The Brothers attempts to inscribe and understand all of these changes, cautioning the Roman nationalists that the die had been cast, and the numbers were showing, and Greek culture was there to stay. But at the same time, honoring Scipio Aemilianus’ departed father, Terence ultimately depicts the indispensability of old Roman virtue and discipline. Terence was an immigrant, a North African, and thus a distant outsider to the already ancient and complex alloy of Greco-Roman culture, and he could, and did see that the Mediterranean would never be Greek, nor Roman, nor Carthaginian, but instead a synthesis of every person who had lived on its shores and sailed its waters. [music]

Homo sum; humani nil a me alienum puto.

Some time around 160 BCE, unbeknownst to Terence or anyone he knew, 1,500 miles southeast of Rome, someone was writing the Aramaic portions of the Book of Daniel. The Maccabean revolt had wound up successfully, and Jerusalem, after butting heads with the ailing Seleucid Empire a few more times, would soon spend a century as a sovereign kingdom.The Aramaic portions in the Book of Daniel culminate in a series of ecstatic visions of Jerusalem’s triumph and the triumph of Daniel himself in the courts of Babylonian and Persian kings. Daniel survives a blasting furnace and a den of lions unscathed, and the advisors of the Persian King Darius, along with their families and children, are torn to pieces by lions. Daniel’s dream visions and the visions that he interprets all suggest that all other phases of history will fall away and the worshippers of Yahweh will reign supreme over the earth, with no complexities or compromises. In the euphoria of the Maccabean triumph in Jerusalem in 160 BCE, all of this may have seemed a possibility.

Around the same time, perhaps a few decades after Terence lived, an Essene community near an archaeological site we call Qumran today was copying the massive Book of Isaiah into a single scroll – the most complete of all the Dead Sea Scrolls. Isaiah, as we saw back in Episode 24, has a small handful of visions of a coming Messiah, whether this Messiah is Moses, or King Josiah, or, as Christians believe, Jesus. But Isaiah, as much as anything, is a vicious rant against Jerusalem’s enemies – Babylon, Assyria, Moab, Damascus, Ephraim, Egypt, and the cities on the Phoenician coast. The babies of Babylon will be torn to pieces, and the women of the city will be raped, Isaiah tells us (13:14-16). The stench of dead Edomites will cloud the sky (34:2-3). The blood of butchered Egyptians will ascend to the slopes of mountains (32:5-6) and at some point, just as the Book of Daniel predicts, at some point, the bedraggled Jerusalemites will rise again like radiant dew coming up from dust (26:19).

None of this has anything to do whatsoever with Terence, and that’s precisely the point. The texts from antiquity that continue to circulate most widely among us today, chief among them the Old Testament, of course, tend to be drenched with blood and doom. Here are the Homeric epics, celebrating the gory futility of human existence and the insane capriciousness of the gods. And there are the tragedies of Sophocles and Euripides, in which, if anyone learns anything, it is almost inevitably the hubris of man and the fierce retributions of the gods. And here is the Aeneid, beginning with a grand tale of diasporic adventure and devolving into a heap of carnage. Terence writes in the second prologue to his play The Mother-in-Law about losing an audience because they were more interested in watching gladiatorial combat. He has been losing audiences for this reason for over two thousand years.

Yet in 160 BCE, as the Aramaic speaking scribe who wrote the central part of the Book of Daniel rehashed the standard Jerusalemite prophecies about slaughtered enemies and glorified friends, as the ascetic Essenes at Qumran learned how to write austere prophecies on sheep skin, as Roman elites watched gladiatorial bloodlettings and fell in love with Homer, as Virgil’s great-great-grandfather came of age, one slight-framed North African man who didn’t even make it to the age of 26 was doing something else. Terence wasn’t interested in the old song and dance about combat prowess and glory and doom, nor the rape and murder of enemies nor the eternal triumph of this or that theology, culture or ethnicity. Terence wrote about how to live life in civilized society, with all of its twists and turns, and all of its moral complexity, how to raise children, how to move forward from familial problems, and how to feel complete in the midst of all of this, no matter how the dice happen to fall.

The title of this episode is Homo sum, which is actually the first two words of what is probably Terence’s most famous quote: Homo sum; humani nil a me alienum puto.29 This line is translated variously, as “I’m a man; I don’t regard any man’s affairs as not concerning me,” or “I’m human, so any human interest is my concern.”30 The line – again, “I’m human, so any human interest is my concern,” which appears near the beginning of a play Terence staged in 163 BCE, is often taken to be a manifesto of the playwright’s universal interest in depicting humanity, regardless of social class, race or gender – perhaps something like Walt Whitman’s “Clear and sweet is my soul . . . and clear and sweet is all that is not my soul.”31 Now, as many classicists will tell you, the Terence quote – Homo sum, etc., is usually presented out of context. It’s actually a line from a character called Chremes near the opening of a play called The Self-Tormentor, and it’s not really about Chremes’ egalitarian concern for all of humanity across the board. In context, “I’m human, so any human interest is my concern” is a statement made by a puffed-up meddler – a kind of self-conscious explanation as to why his nose is in everyone’s business at the moment.

Anyway, while the quote, ‘I’m human, so any human interest is my concern” isn’t actually an artistic manifesto, voiced by Terence himself about his literary creations, I still think it’s a fitting quote for the end on our show on this giant of Roman literature. Terence, by the end of his short life, wasn’t from anywhere. He had migrated, and moved – he’d gone from slave to promising freed man to a master playwright, and had seen in himself and in his friends the social fashioning processes of the Roman Republic, and over all of it, the relative insignificance of individual people in the midst of great global forces. This set of experiences made him who he was – a human, concerned not with the triumph of a single individual, ethnicity, or theology, but instead concerned with how to get along with dignity and happiness in a ceaselessly changing world.[music]

The First Seeds of Decay

Terence’s friend Scipio Aemilianus, a figure relentlessly at the center of Roman history during the early and mid 100s BCE, not only knew Terence himself, but also a set of generals and military men who drove the spectacular expansion of the Roman Republic over the course of this century. Scipio Aemilianus, who commanded the final conquest and destruction of Carthage in 146 BCE, was said to have stood on the walls of Carthage as it burned, wept for its fall, and quoted the Iliad, musing darkly that the same thing could just as well have happened to Rome. Perhaps, if there’s any truth to this story about the remorseful general, and if Scipio Aemilianus’ friend Terence really had hailed from Carthage, Scipio Aemilianus was thinking about his brilliant young long lost Carthaginian friend, and seeing tens of thousands of young Terences burned in their homes and sold into slavery.

Sculptor Eugéne Guillaume’s The Gracchi (1853). Photo by Sailko.

If we think of the next hundred years of Roman political and military history as an avalanche, Tiberius Gracchus, his persecution of his fellow tribune, and his subsequent murder, were the first, tiny stone to begin tumbling down hill. Roman history up to Tiberius Gracchus had not been a picnic. From the battles with Pyrrhus in 280 BCE all the way down to the eradication of Carthage in 146, Rome had been almost continuously at war. But Rome had been immune to major civil wars and succession disputes that plagued the successors of Alexander to the east – the toxic process of power transfer that had kept, especially, the Seleucids from a state of stability and prosperity. What happened in 133 BCE – while Tiberius Gracchus may indeed have had generous motivations for bending the rules of law – what happened in 133 BCE was the beginning of the end of the Roman Republic.

Moving On to Lucretius

A few episodes ago we talked about the cultural changes wrought during the Hellenistic period. Alexander’s campaigns, especially in the eastern Mediterranean and Turkey, resulted in quick successions of wars and the mass enslavements that funded them. We talked about how everyday people during this rocky period of history began to seek answers in the form of individual-centered cult religions – old ones like Pythagoreanism and Orphism, but increasingly the cults of Dionysus, Cybele, and later Mithras and Christ – religions that guaranteed the individualized attentions of a deity, and posthumous comfort and joy as a rewards for enduring the hardships of a chaotic world.In the next show, we will talk about one of these cults, one of the most misunderstood philosophical movements in world history – a movement that we call Epicureanism. For centuries, the Roman writer Lucretius’ poem On the Nature of Things has been one of our main sources for learning what Epicureanism is – what the Greek philosopher Epicurus taught, and what his devotees actually thought and practiced. Today, Epicureanism is synonymous with hedonism and gluttony, an association that is radically off the mark from what Epicurus and Lucretius actually taught. Their philosophy – one of atomic materialism, religious iconoclasm, moderatism and withdrawal from the cacophony of public life – was one of the most important intellectual trends that existed in Roman culture.