Episode 57: The World Grows Dim and Black

Virgil’s Aeneid, Books 10-12. The end of Rome’s great epic is about something Romans of Virgil’s generation knew very well indeed. War.

| Read Transcription | References and Notes |

| Episode Quiz | Episode Song |

| Episode on Spotify | Episode on Apple Podcasts |

| Previous Show | Next Show |

Virgil’s Aeneid, Books 10-12

Hello, and welcome to Literature and History. Episode 57: The World Grows Dim and Black. This is the fourth of four programs on Virgil’s Aeneid, an epic written in the 20s BCE and left incomplete when the poet died in 19 BCE. If you’re just jumping in, the story of the Aeneid begins back in Episode 54.Up to this point, we have heard of how Aeneas escaped Troy, wandered the Aegean for seven years, and landed in the north African kingdom of the Carthaginian Queen Dido. We learned how Aeneas and Dido fell in love, and how, after leaving her, Aeneas went to the underworld to converse with the spirit of his departed father. Last time, we saw the goddess Juno stirring up trouble in central Italy, Aeneas sneaking out of the Trojan camp near the mouth of the Tiber to find more help, and the confederated Italian forces making their first assault on the Trojan base camp. It is a particularly exciting juncture of the story to jump back into. Juno knows she cannot stop the founding of Rome, but she wants to inflict as much pain and death as possible in the meantime. Aeneas, pressed by his divine destiny, finds himself having to fight a seemingly impossible war. And down below the Trojan walls, the Italian champion Turnus and his sadistic lieutenant Mezentius are eyeing the battered Trojan fort and determining how they’re going to get in. The last three books of the Aeneid are about a full scale war – a war in which humans and gods fight alongside one another to determine the future of ancient Italy, and by extension, the future of Rome and the Mediterranean world.

Since the work of Harvard School interpreters in the early 1960s, such as Adam Parry, Wendell Clausen, and Michael Putnam, readers have noticed a pacifism and compassion for Mediterranean citizens of all social echelons even in the violent later books of the Aeneid. The painting is Amos Cassiolini’s Cherries (19th century).

Then, there are the Italians. The Italian champion, Turnus, seems to have been a fairly stand up guy before Aeneas inadvertently stole his fiancé, and Juno stirred Turnus up with bloodlust. But Turnus’ lieutenant, the former Etruscan King Mezentius, conversely, has always been regionally detested. Mezentius, we learned a couple of books ago, is a sadist – a torturer who once enjoyed sewing the bodies of the living to the bodies of the dead, and it is largely because of Mezentius that Aeneas is able to get so many Etrurians to join with him in the war. Mezentius has a son called Lausus, whom Virgil emphasizes is nothing like his father, and deserves better than a deposed psychotic king for a dad, and Lausus shows up in Book 10, as well.

So those are the two conglomerations that oppose one another as the Aeneid comes to a climax – two patchwork quilts of allies, each knit together by a combination of necessity, divine intervention, and occasionally, old animosities. Virgil has many names for each quilt of allies, commonly calling the Italians “Rutulians” and the Trojans “Dardans” or “Teucrians,” but for simplicity’s sake I’m going to call the people on Aeneas’ side “Trojans,” and the people on Turnus’ side “Italians.”

So let’s plunge back into the Aeneid. Unless otherwise noted, my occasional quotes will come from the Frederick Ahl translation, published by Oxford in 2007. [music]

The Aeneid, Book 10

Jupiter, Venus, and Juno Hold a Meeting

Italy had erupted into chaos, and there was no end in sight. The recently arrived Trojans were ringed on all sides by foes, and the native Italians, stirred by the wrath of Juno, sought to destroy the recently arrived strangers who had appeared on their shores. Looking at the tumult unfolding in Italy, Jupiter called for a meeting of the Olympian pantheon. The gods met in a long hall, and Jupiter asked the assembled deities why a war had begun in Italy. He said he had forbidden the war. And he added that there would come a time for another war – long, long after the Aeneas and his people settled in central Italy, and that this war would be between Rome and Carthage. And just for clarification, the events of the Aeneid are supposed to have taken place in the mid 1100s BCE, whereas the Punic Wars happened long afterward – from 264-146 BCE. So Jupiter essentially told the Olympians to save their strength for the real war ahead and stop expending their energy inciting feuds in Italy.

Juno remains a thorn in the Trojans’ side up until the very last seconds of the Aeneid. The painting is Joseph Paelinck’s Juno (1832).

When Venus finished her long petition, Juno began one of her own. Juno emphasized that Aeneas hadn’t even gone to King Latinus in person – he’d sent ambassadors. Sure, Aeneas had gone to Italy at the directive of the gods. But once there, Juno said, he’d kind of done his own thing, sending ambassadors to Latinus and then leaving his inexperienced young son in control of the fort while he sped off to try and round up more men. Further, Juno said, who could blame the Italians for trying to defend their territory against the new settlers? By the way, the reasoning Juno is offering here is somewhat duplicitous, as she has had a central role in getting the war started. Anyway, Juno ended her speech by deflecting blame for present the conflict in Italy to Venus. Venus, said Juno, had started the Trojan War in the first place seventeen years earlier by stirring up a romance between Helen and Paris. It was all Venus’ fault.

Jupiter, having listened to both sides of this argument, spoke up. He said that that day, the gods would not intervene in the fighting. That day, said Jupiter, men would succeed or fail based on their own efforts. And he added the interesting promise that “King Jupiter’s wholly impartial; / Fates will discover a way” (10.112-13).2 The line calls to mind the discussion that we had at the end of the previous episode on fate and the gods, and leads us to ask who’s at the divine steering wheel in the Aeneid – Jupiter, the fates, or something else altogether? Whatever the exact force driving events in this part of the poem, Jupiter swore on the underworld that he would keep his promise that day, and that the war being fought below would be determined, for a time at least, without the interference of the Olympians. [music]

Aeneas Travels South and Arrives with Reinforcements

Down at the Trojan camp, things were going badly for the long-suffering easterners. Italian forces were attacking all the gates at once, and the Trojans hefted spears, boulders, and flaming barrels down on their adversaries, nocking arrows and firing them down into the sea of attackers. Even Aeneas’ son Iulus was out with the other defenders.

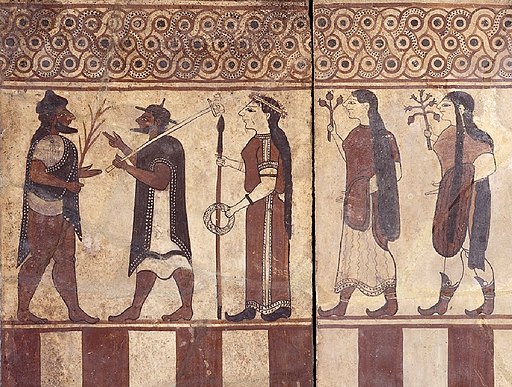

Aeneas enlists with Etruscans, a people who were as historically formed by Greek culture as the Romans. These Etruscan plaques, from 560-50 BCE, show Elcsantre (Paris Alexandros); Turms (Hermes); Menrva (Athena); Uni (Hera); and Turan (Aphrodite).

Aeneas and the Etruscans, as they sailed south along the coast, made quite a spectacle. Virgil offers an inventory of the many Etruscan heroes who enlisted with Aeneas, along with the size and nature of the armies that accompany them. Amidst these armies was the force of Manto, a hero from Virgil’s own hometown Mantua, five hundred strong and united in their hatred of the enemy King Mezentius. All told, Aeneas had found thirty ships full of men to enlist with him – a diverse set opposed, for various reasons, to the consortium that had amassed against the exhausted Trojans.

As Aeneas’ new fleet advanced southward, they were joined by thirty nymphs to match the hero’s thirty ships. The leader of these nymphs told Aeneas what was happening back at the Trojan siege camp. Some of the Trojan allies, she explained, had arrived. But the Italian hordes, knowing full well that the Trojans had reinforcements coming, were working hard to make sure that Aeneas’ auxiliary forces couldn’t get to his fortress. The nymph told Aeneas that at first light the next morning, he would need to fight hard. And with this advice, the nymph and her sisters grabbed the sterns of Aeneas’ ships and pushed them through the ocean like the javelins. So much, by the way, for Jupiter’s pledge to a day without divine intervention.

On the deck of his nymph-propelled ship, Aeneas said a prayer and the fleet splashed onward, warriors arming for battle on their speeding decks. It wasn’t long before Aeneas’ ships drew near the Trojan siege camp. The Trojans saw the new arrivals first, cheering mightily at their leader’s return. Then the Italians saw them – an entire fleet, rolling on the ocean. When the ships landed, Aeneas, clad in his divine armor, seemed to glow with molten heat. This was not a war that he had wanted. But fate had destroyed his beloved homeland and driven him across oceans, and now, whatever his desires might have once been, he had to fight.

The Italian champion Turnus watched Aeneas and others setting out gangplanks and climbing down oars and even just jumping off and swimming to the shore. Turnus said it was time to strike – now – before Aeneas’ auxiliary force had time to form up. The Italians hurried toward the seashore, and the battle began. Aeneas killed two Italians, then three, then four, the fourth a giant man wielding a club and crushing his way through Aeneas’ forces. Aeneas speared a man through the mouth who was at just that moment taunting him, and as a bevy of Italians hurled javelins at him Aeneas’ armor, and his mother’s divine protection, kept him from being injured. Aeneas began throwing more javelins – he killed a man and then nearly managed to kill the man’s brother.

The Italians, naturally, struck back. One, a Sabine man, inflicted heavy casualties on the Trojans, until Virgil writes, “Just so the Trojan front and the [Italian] front, as they battled, / Fought, foot jammed against foot, dense packed, man pitted against man” (10.360-1).

Turnus Fights Pallas

As much as Aeneas and his reinforcements had bolstered the general Trojan hopes, the Italian army was still gigantic. In a nearby dry riverbed, Aeneas’ young friend Pallas saw allied cavalrymen retreating and being forced into hand-to-hand combat. The young man urged his countrymen to redouble their efforts. He said there was nowhere to retreat – this moment was it – they had to hurl themselves into the thick of the fray.And leading by example, young Pallas charged into a thick knot of Italian fighters. Pallas speared a man through the midriff, stabbed a man through the lungs with a sword, then killed two more. He slaughtered a pair of twins, decapitating one and severing the hand of the other. Pallas speared an Italian passing by in a chariot, and gradually, his fury and courage inspired his allies around him to follow suit. Pallas impaled another Italian, but soon, an important Italian fighter took note.

This fighter was called Lausus, and he was the son of the wicked Mezentius, although Virgil makes clear that Lausus did not share his father’s sadism or corruption. Lausus saw the Trojan ally Pallas chopping through his troops and struck back furiously. These two commanders were the younger generation involved with the war, and they threw themselves into the battle. Before the two young men could square off and face one another, however, the champion Turnus steered his chariot into the fray, protecting his young ally Lausus.

Turnus wanted to fight Pallas. And as is often the case in ancient Greco-Roman epic, the general tumult of battle halted and cleared way, for a moment, so that giant Turnus could face courageous young Pallas. Virgil writes, in the Ahl translation, that Pallas

Pulled back, shocked stock-still by his first sight of Turnus. His eyes moved,

Scanning the giant body, assessing its strength at a distance,

Glaring defiance. He fired back words in response to the tyrant’s

Own volleyed [threats]: “Either way, [said Pallas,] I’ll have glory: the Spoils of Distinction

Or a heroic death. My father accepts either outcome.

Cut out the threats.” (10.446-51)

Turnus jumped down off of his chariot. Pallas knew he couldn’t match his adversary in strength, and so he prayed to Hercules that his javelin would reach Turnus, but Jupiter would not allow any divine intervention in this particular contest. Pallas’ javelin struck Turnus’ shield hard, along with some of his armor, cutting one of the Italian champion’s shoulders. But Turnus was undaunted. Turnus, voicing one of the goofier lines of the Aeneid, growled, “Look, and see whether the weapon I wield cannot penetrate deeper” (10.481). Turnus hurled his own javelin, and, passing through young Pallas’ shield and armor, the weapon became lodged in his ribcage. It was a mortal wound. Young Pallas crumpled, dropping his weapons, until he was gnawing at the ground in agony. What happened next is important for the closing book of the poem. Turnus looked around in victory, and told young Pallas’ people that the warrior’s corpse could go home to his father, but that Turnus would take Pallas’ belt, since Pallas and his father Evander had allied with Aeneas.

It doesn’t seem like such a crazy thing to ask – victorious epic villains have certainly done far worse, and nothing about the fight seems to have been dishonorable. Further, unlike Achilles and Hector in the Iliad, Turnus offers to return the body of his foe to young Pallas’ family, rather than dragging it around in a chariot and degrading it in other ways, as Achilles does to Hector’s. However, in spite of Turnus’ relative clemency, Virgil emphasizes that the theft of young Pallas’ belt had dire consequences. Virgil writes, in the Vintage Classics Robert Fitzgerald translation:

The minds of men are ignorant of fate

And of their future lot, unskilled to keep

Due measure when some triumph sets them high.

For Turnus there will come a time

When he would give the world to see again

An [unplundered] Pallas, and will hate this day, Hate that belt taken. (10.701-7)3

All I can say is that that must have been one hell of a nice belt to elicit such commentary and consequences. For the record, the belt is described at one point as a masterwork of art, so we’re not talking about a piece of leather cord here, but nonetheless Pallas’ belt becomes perhaps the most important object in the final three books of the Aeneid. So, Pallas, who had passed away, was carried on his shield back into camp. And Aeneas, who had taken a liking to the young man, heard the dire news of his death. He had not only been fond of Pallas – Aeneas also valued Pallas’ fighting prowess, and knew that the young man’s loss might tip the scale against the Trojans. And so in a furious rush, Aeneas began trying to cut his way to the Trojan camp, thus joining his countrymen with his newly arrived reinforcements. [music]

The Rage of Aeneas

Aeneas, thinking of his dead comrade Pallas, killed four young Italians as he made his way back to his base camp. Aeneas hurled a spear at a man called Magus, who ducked. Knowing that he stood no chance against Aeneas, Magus asked Aeneas to please spare his life – he had a son just as Aeneas did. What was more, he’d surrender all of his things to Aeneas at the war’s end – couldn’t Aeneas just let him go home? And Aeneas gave the following speech:“Spare these multiple masses of silver and gold that you’ve mentioned,

Save them for your own sons. This commercial aspect of warfare

Turnus was first to suspend just now by his killing of Pallas.”

That’s what Anchises’ ghost has declared – and so has Iulus.”

[And Virgil continues] This said, [Aeneas’] left hand grasps Magus’ helmet, and, though he’s still begging,

Bends back his neck. Then [Aeneas] plunges the blade hilt-deep in his suppliant. (10.531-4)

Evidently, Aeneas thought that because Turnus had looted a belt from his adversary, who had actually tried to kill him, then Aeneas could kill a defenseless man, because of a declaration made by Anchises’ ghost and young Iulus, a declaration that has not actually been made by either person. Anyway, continuing his rampage, Aeneas executed the defenseless Italian warrior Magus, and pressed on. Aeneas’ next martial achievement – also a questionable achievement – was chasing down a priest of Apollo on the Italian side, slaughtering the priest when the priest tripped, and stealing his things. After killing the priest, Aeneas killed a Volscian [VOLE-ski-ahns] warrior, then decapitated another Italian fighter who begged for his life at the last moment, cursing him to remain unburied. Aeneas then surveyed the field and sought out the strongest fighters on Turnus’ side. He became a monster, killing and killing, so frightful that he scared a chariot driver’s horses into the sea. Another chariot driver approached and taunted Aeneas, who impaled him with one of a seemingly inexhaustible supply of javelins. The chariot driver’s brother begged for his life, and Aeneas killed him without hesitating. He is, at this point, in Virgil’s words, “Out of control, like a torrent in flood, like a raging tornado / Black in the sky” (10.602-3). And however dreadful and unscrupulous Aeneas’ general massacre had been, he almost singlehandedly broke the siege on the Trojan camp. Because a moment later, Iulus and other young Trojans burst out of the camp’s gates.

Aeneas’ berserk frenzy of killing at this moment in Book 10, to many interpreters, shows a critical change coming over Virgil’s central character. Throughout the Aeneid, Aeneas is described as “pious,” and “dutiful.” Aeneas faces difficult decisions in the first nine books of the epic, and, usually with a heavy heart, he chooses the lesser of two evils. In Book 10, however, Aeneas, the distinctly Roman hero who almost always acts with his people, and his duties in mind, consistently becomes a bit more like the earlier Homeric hero Achilles. Achilles, however magnificent he is, is only out for himself, spending most of the Iliad watching his allied Greeks get killed on the battlefield. And as the Aeneid progresses into its final three books, Aeneas is consistently motivated less by the great responsibility of serving his people, and more by that central characteristic of Achilles – the very first word of the Iliad – rage.4 [music]

Aeneas Fights Lausus and Mezentius

Now, if you remember, this was supposed to be a day with no divine intervention. But, as we learn in a scene in which Jupiter is talking to Juno, Venus has been helping the Trojans along all day. Which is strange, both because Jupiter imposed a moratorium on divine intervention, and also because he has been ignoring Venus’ disregard of his orders, and also because of what he says to Juno. Jupiter told Juno that if she wanted to spirit away her beloved Turnus, she could. And Juno thereafter threw herself down toward the battle in Italy.

Increasingly, Aeneas acts with the sort of indiscriminate bloodlust of Achilles. The obvious literary analog for Aeneas’ wrath is that of Achilles upon the loss of Patroclus, although Aeneas’ relationship with young Pallas has been considerably shorter. The painting is The Shadow of Achilles Appearing to the Greeks, by François-Léon Bënouville (c. 1840s).

The illusion then vanished, and Turnus was distraught. He was no deserter, he said! He prayed to Jupiter to let him rush back into the fray, and help his warriors. Turnus wanted to die, but Juno kept him on the ship, and guided him gently back to a different area of the coastline.

Turnus’ absence meant that the most fearsome Italian still on the battlefield was the vicious Mezentius. Everyone hated Mezentius, and dozens of Trojan spears were aimed at him, but somehow he withstood the assault. Mezentius then struck back, killing several Trojans and Trojan allies. As much as opposing forces tried to take Mezentius down, they couldn’t. He was tough, and he knew it, and no one quite had the nerve to face him alone.

As the battle continued, many were falling on both sides, and the gods looked on pityingly. Mezentius carved his way through the ranks of the Trojans and their friends, until finally, Aeneas saw him. Aeneas launched a javelin at Mezentius so hard that when the other man deflected it, the weapon still killed an Italian warrior. Aeneas then threw a spear, and this spear cut through Mezentius’ shield and sliced into his groin. Aeneas unsheathed his sword and hurried to finish off this second strongest of the Italians. But Mezentius’ son Lausus, seeing his father injured, put himself in Aeneas’ way, parrying some of the Trojan hero’s attacks until the Italians were able to cluster together and get Mezentius out of the way. Aeneas then had to seek shelter beneath a rain of arrows and other weapons.

Aeneas told Mezentius’ son Lausus that his devotion to his father had made him do something very dangerous, and following these words, struggling through the opposing soldiers, Aeneas smashed his sword through Lausus’ shield and killed him.5 Yet, seeing the youth dying such a painful death, Aeneas thought of his devotion to his own father, and he felt sorry for the poor young man. And in order to comfort young Lausus, Aeneas said, in the Penguin W.F. Jackson Knight translation,

O, piteous boy, what shall Aeneas the True give to you to match your high feat of arms and your great goodness? Keep for yourself the arms which gave you so much joy; and I release you to join the spirits and ashes of your ancestors, if such a freedom can concern you. But even in disaster you at least have some consolation for your grievous death in knowing that you died by the right hand of mighty Aeneas. (10.820-6)6

I’m sure that this sympathetic slash egotistical speech was a real balm to the young man’s departing spirit. Meanwhile, not far off, Mezentius caught his breath and shook with pain at the wound Aeneas had inflicted. He asked his men where Lausus was, and gradually intuited that the boy had been killed before Lausus’ remains were brought to him. The death of Mezentius’ son made him sick at himself, and his actions. He said his own wickedness and his crimes had sullied his son’s future and caused the end of his life. He, Mezentius, should have been dead – dead a thousand times – but not young Lausus. Mezentius said he wasn’t finished yet. The wound in his groin hindered his mobility, but he could still ride his stallion.

And so Mezentius mounted up, grabbed two fistfuls of javelins, and charged into battle. Even during his assault he felt heartsick – a combination of disgust at himself, and grief, unquenchable anger and resolute courage. Mezentius screamed Aeneas’ name, and Aeneas heard. Mezentius said he had come to die, but not before giving Aeneas a gift, and with these words the Etruscan king began flinging javelins at the Trojan hero. Aeneas crouched under his shield as Mezentius’ weapons thundered into it. The attack was so fierce that he could barely move – he needed to do something to make the fight proceed on more equal terms. And so, recklessly moving his shield to the side, Aeneas threw a spear – not at Mezentius, but at his stallion – and the spear went straight into the horse’s head.

Mezentius went down. His arm popped out of its socket. Aeneas stalked to where Mezentius had fallen and stood over him. “Where,” said Aeneas, “is the fierce Mezentius now?” (10.897). Mezentius fought to breathe. He told Aeneas not to gloat. He had, after all, come to die. He asked to be buried with his son, and offered his throat to Aeneas. A moment later, rivulets of blood were flowing over his armor. [music]

The Aeneid, Book Eleven

A Temporary Armistice

Temporary armistices toward the end of the Aeneid enable Virgil to write poignant scenes of pastoral peace, such as he had years earlier when he wrote the Eclogues. The painting is Claude Lorrain’s Landscape with Goatherd (1632). Lorrain also painted scenes from the Aeneid.

Aeneas went to where young Pallas lay dead in his quarters. Which is odd, because Aeneas and Pallas have just arrived the previous afternoon and immediately started fighting, and Pallas was killed before he could have established any quarters. Anyway, seeing the young warrior dead in his prime, Aeneas voiced a long tearful soliloquy for Pallas, feeling what Virgil describes as “a grief so immensely / Huge” (11.62-3), which is also strange, because he’s only known Pallas for about 48 hours. We’ll talk more about some of these issues later.

With his lamentation for Pallas complete, the young warrior was given a casket made of twigs of oak and arbutus. Aeneas draped a cape over Pallas that Dido had made for him in Carthage, along with weapons and armor looted from defeated Italians. Soon, a full funeral procession was formed – one which included horses, and a group of captured enemies whom Aeneas intended to sacrifice, and chariots. With the victims prepared for sacrifice, and young Pallas suitably honored in a grand cavalcade, Aeneas turned and went back into the Trojan fort.

Later that day, negotiators from the city of King Latinus visited the Trojans and requested the right to bury their dead. Aeneas said that they certainly could. He said he didn’t even want to be fighting them – they were the ones who’d pursued violence against him, after all – and his real enemy was Turnus. Aeneas said he’d fight a duel with Turnus at any moment to end the war – and in the mean time, they were welcome to bury their dead.

One of King Latinus’ ambassadors seized what looked like an excellent opportunity. He said they would carry the news of Aeneas’ clemency and willingness to negotiate over to King Latinus, and that hopefully Aeneas could actually meet the man who had briefly been his future father-in-law. The ambassador proposed a twelve day truce, and both sides agreed to it. Soon enough, the native Italians were walking freely among the Trojans and their allies, retrieving their dead and cutting down nearby trees to build litters for them.

Latinus Considers Curtailing the War

Meanwhile, in the city of King Evander, news of Pallas’ death had arrived. The ruler ran out of his palace when the funeral procession arrived, crouching at the side of the dead boy’s litter and crying at the sight of his dead son. His words, peculiarly, echoed Mezentius’ upon the death of Mezentius’ son. Old King Evander said he shouldn’t have outlived his son. But he said that young Pallas had died well, and that it was time for the Trojans who’d brought Pallas’ body back to return to the war. Turnus, after all, was still out there, and old King Evander asked the Trojans to avenge young Pallas’ death.Back at the Trojan camp, the Trojans built funeral pyres for their dead along the beach and undertook the rituals and sacrifices of funerals. The native Italians, too, mourned their dead, carrying fallen soldiers home when they could, and burning the rest. In the city of king Latinus, lamentations rang loud, and news of a keen disappointment was carried through the Italian army. An embassy sent to the Greek hero Diomedes – who had once bested Aeneas during the Trojan War – had been unsuccessful. The Italians were on their own. Diomedes had said that the Greeks had committed enough atrocities during the Trojan War and were still suffering as a result, wandering and lost, like Odysseus, or butchered, like Agamemnon, in the wake of the earlier conflict. Diomedes said he had no feud with the scattered remnants of the Trojans.

Hearing that they’d receive no aid, King Latinus shook his head in despair. “Citizens,” he said, “we are engaged in a war we can’t win with a people / Born of the gods, men no battles can tire” (11.305-6). Latinus said that he personally owned a swath of hilly land up in Etruria. He said he would be willing to give the whole thing up to the Trojans for settlement. And he added that if the Trojans merely wanted to leave and begin a conquest elsewhere, then the Italians could build ships for them to do so. The war as it had been going could not be allowed to continue, Latinus emphasized.

Some of the Italians were not happy about this decision. One man, Drances, replied to Latinus’ plan with a long speech, a speech that urged Turnus to fight a duel with Aeneas. Turnus accused Drances of bluster. And he gave a rhetorically clever speech to old Latinus. Turnus said that if the native Italians were so feeble that a single loss in battle convinced them to capitulate to the Trojan presence, then the Italians should indeed give up, because they were useless. But – said Turnus – if the Italians had any fiber in their muscles, they owed it to themselves to keep fighting. And, Turnus added, if it was a duel that Aeneas wanted, Aeneas would get his duel. [music]

Camilla Enters the Fray

Back at the Trojan camp, Aeneas’ men were stirring. They ventured forth from their camp and began amassing in the open for the first time, much to the disconcertion of the native Italians there to see. Turnus, hearing of the Trojan saber-rattling, began preparing for a renewed outbreak of war.This time, the battle would be fought closer to King Latinus’ citadel – so close, in fact, that Italians began digging trenches in front of the gates and tightening up various other defenses. The queen and her daughter Lavinia were taken up to the heights of the palace, and Italian mothers prayed that Aeneas would fall in battle.

Turnus was hoping for the same thing. He put on his armor and weapons. But even more eager to begin fighting was a woman named Camilla – the queen of a people called the Volscians. Camilla promised that she’d be instrumental in helping Turnus that day – she that she would personally charge and engage with Aeneas’ cavalry, and she would do so all by herself. Rather than asking her whether or not she was sane, which is perhaps what most of us would have done, Turnus told her that her bravery was welcome, and gave her some slightly more specific instructions.

Turnus then went to a shady passage in the mountains he thought Aeneas would pass through, and prepared for an ambush. The warrior queen Camilla also prepared for an assault, but before she did so, the goddess Diana gave a short speech about Camilla’s life and devotion. Once, said Diana, when Camilla was a newborn, her father had been in the midst of a dire battle. Camilla’s father, to save his daughter’s life, had tied her to a javelin and thrown the javelin to safety. Camilla’s father won the battle, though, and little Camilla was raised in the wilds, suckling a mare and learning how to shoot a bow and throw spears at a very young age. As Camilla grew older, though many sought a marriage with her, she remained chaste, and a devotee of the goddess Diana. But unfortunately, said Diana, Camilla’s time to die had come. As tragic as this was, though, Diana said, those who gave Camilla her death wounds would in turn be killed by the goddess Diana herself. Which makes you wonder why Diana doesn’t just help her beloved virgin warrior in the first place, but, as always, the gods in Greco-Roman epics collectively don’t make the most rational decisions.

Books 11-12 of the Aeneid tell of battle after battle, with Camilla, Queen of the Volscians arriving on the scene and dying in a breathtaking sequence not quite long enough to be tragic. The painting is Guiseppe Cesari’s Victory of Tullus Hostilius (1601).

Seeing the tide of battle turning to favor the Italians, Jupiter intervened, and one of the Etruscans suddenly began berating his comrades for wilting before the assault of a woman. As the Trojans began fighting back, another one of their men – an Etruscan named Arruns – began stalking the deadly Camilla, following her and keeping his spear point focused on her. And Camilla, so intent on catching a large and finely armored Trojan in the distance, did not notice the threat that lay closer at hand until it was too late. Young Arruns voiced a prayer to Apollo and then flung his javelin with all his might. For a second, all seemed quiet, and Camilla looked around, unaware that a weapon had been loosed against her. And then the javelin pierced her breast through the nipple. The assassin Arruns, seeing he’d felled the great Camilla, turned and ran. Camilla gripped the spear and tried to remove it, but it was too late. Camilla turned toward one of her female lieutenants, and said, in the Penguin W.F. Jackson Knight translation, “An agonizing wound destroys me; and around me the world grows dim and black. Make your escape. And deliver this my last message direct to Turnus: let him move up into battle and fend the Trojans from the city” (11.824-7).7 With these last words, she died.

Seeing Camilla’s demise, the Trojans fought harder than ever. But as for Arruns, the young man who’d killed Camilla – his hours were numbered. A nymph called Opis was watching him closely. She drew a bow back so far that the ends of it touched, and loosed an arrow. As soon as he heard the twang of the bowstring, Arruns was struck. His comrades watched him writhe and die, but the nymph who had murdered him to avenge Camilla’s death had already soared back to Olympus.

The Trojans were now gaining ground and pushing the Italians once again back to King Latinus’ citadel. The city gates were closed, and those stray Italians left outside were executed by the Trojans. Turnus, at this point, was up in the woods nearby, watching. He had been planning on ambushing a contingent of the Trojan army that had not yet arrived, but could not stand by as the Trojans reached the walls of Latinus’ city. Turnus ran down to the plain. And as soon as he did, Aeneas and his men appeared in the woods, directing their course toward the main part of the fighting.

The two champions saw one another. But the day had grown long, and the sun had fallen into a dark red. Aeneas and his men built a fortified camp down below the city. And everyone – Trojans and Italians alike – prepared for the battle that would end the war. [music]

The Aeneid, Book 12

Juturna Sabotages the Duel of Aeneas and Turnus

From the citadel of King Latinus, the Italian champion Turnus looked out over the retreating Italian armies, fuming with anger. He said it was time for him to fight Aeneas. A treaty could be drawn up, and the two champions would decide the outcome of the war. King Latinus was listening, and he said indeed Turnus was a brave man. Latinus admitted to Turnus that he’d never wanted his daughter Lavinia to get married. But, Latinus said, he loved Turnus, and the Queen loved Turnus, and so the decision had been made. Latinus regretted betraying poor young Turnus, when he promised Lavinia to Aeneas. Latinus said, “I broke all bonds of agreement, / Took back my son-in-law’s promised bride, took up arms in unrighteous / Conflict” (12.30-2). Which is a strange thing for Latinus to say, since he actively opposed the war. Latinus’ speech then grew stranger. While standing in conversation with Turnus, Latinus said that if Turnus were dead – if he could betray Turnus, somehow, it would be good for everyone. Turnus, naturally, was not comforted by this bizarre monologue. He said he still wanted to fight Aeneas.

The sabotaged duel between Aeneas and Turnus calls to mind the interrupted dual between Paris and Menelaus in the Iliad. Both interruptions were divinely prompted, and both caused the continuation of an otherwise unnecessary war. The painting is Johann Heinrich Tischbein’s The Duel of Menelaus and Paris (1757).

With this proclamation, Turnus sped off to ready himself. He checked his horses and buckled on his armor. He whirled a huge spear and prayed that it would help him crush Aeneas the next day. Turnus stalked and glowered, so angry and eager for a showdown that sparks seemed to fly from him.

Meanwhile, Aeneas had heard the other champion’s challenge. He told his fellow Trojans what was happening and he sent men to King Latinus to agree to the trial by single combat. At dawn, both armies gathered beneath the walls of Latinus’ city. Captains and soldiers alike wore their finest. When the signal sounded for combat to begin, men sunk their spears and shields into a great circle. High up on the walls and towers of the city, old men sat and looked down to watch the competition.

Juno was there, too. And she addressed the sister of Turnus, who was a goddess called Juturna. Juno flattered the lesser goddess, and then added that Turnus was going to need divine protection in the upcoming contest. And the ever-lovable Juno said that the single combat should be forestalled or interrupted – that way, full scale war could break out again.

Latinus and Turnus rolled out of the city in glittering chariots. Aeneas, clad in his divine armor, prayed to Jupiter and Juno, Mars, and the mysterious forces that kept the sky and ocean separate. Aeneas said that if he won, he’d never favor Trojans over native Italians. He’d never try to subjugate anyone, least of all Latinus, and the Trojans would take care of themselves.

Both combatants voiced their support of the peace agreement, and sacrifices were made to consecrate the impending single combat. All seemed to be set, but some of the native Italians eyed Turnus with apprehension. He was young. And he looked pale – evidently he was a less formidable sight than the more hardened veteran Aeneas. And into the Italian army’s anxious survey of their champion came the goddess Juturna – Turnus’ sister. She flew all around and told the Italians it was not right to leave the whole war on Turnus’ shoulders. The Trojans were all out there, Juturna said – a pitched battle could be fought honorably. And, Juturna emphasized, Aeneas had said he wouldn’t enslave anyone – but how could they know this for sure? Juturna caused an omen to be seen – a solitary eagle attacked a swan – but just afterward many flocks of shorebirds turned on the eagle and chased him off into a fogbank. The symbolism was that Aeneas, the fierce eagle, might be chased off of Italian shores if they worked together.

One Italian acted on the omen. He let loose a war cry and threw a javelin. And as the javelin flew, the war cry broke out all through the assembled Italians. The javelin killed a young Arcadian warrior, whose brothers unsheathed their swords. Soon, fighting broke out all over, and spears were going through bodies and heads were being split open. Aeneas saw the chaos and shouted for everyone to stop, but as he shouted, a stray arrow wounded him.

Turnus saw Aeneas being escorted off the battlefield, and the Italian champion, now unmatched, threw himself into fighting. He ran over Trojan warriors with his chariot, the unfortunate men crushed by his horse’s hooves. He impaled a far off assailant and taunted the man before killing him, and then Turnus killed six more men. The Italian champion’s charge was so fierce that he scattered whole columns of Trojans. For a moment, a Trojan charioteer had slightly better luck with Turnus, but after a short fight, Turnus decapitated him. [music]

Aeneas Recovers and Returns to the Battle

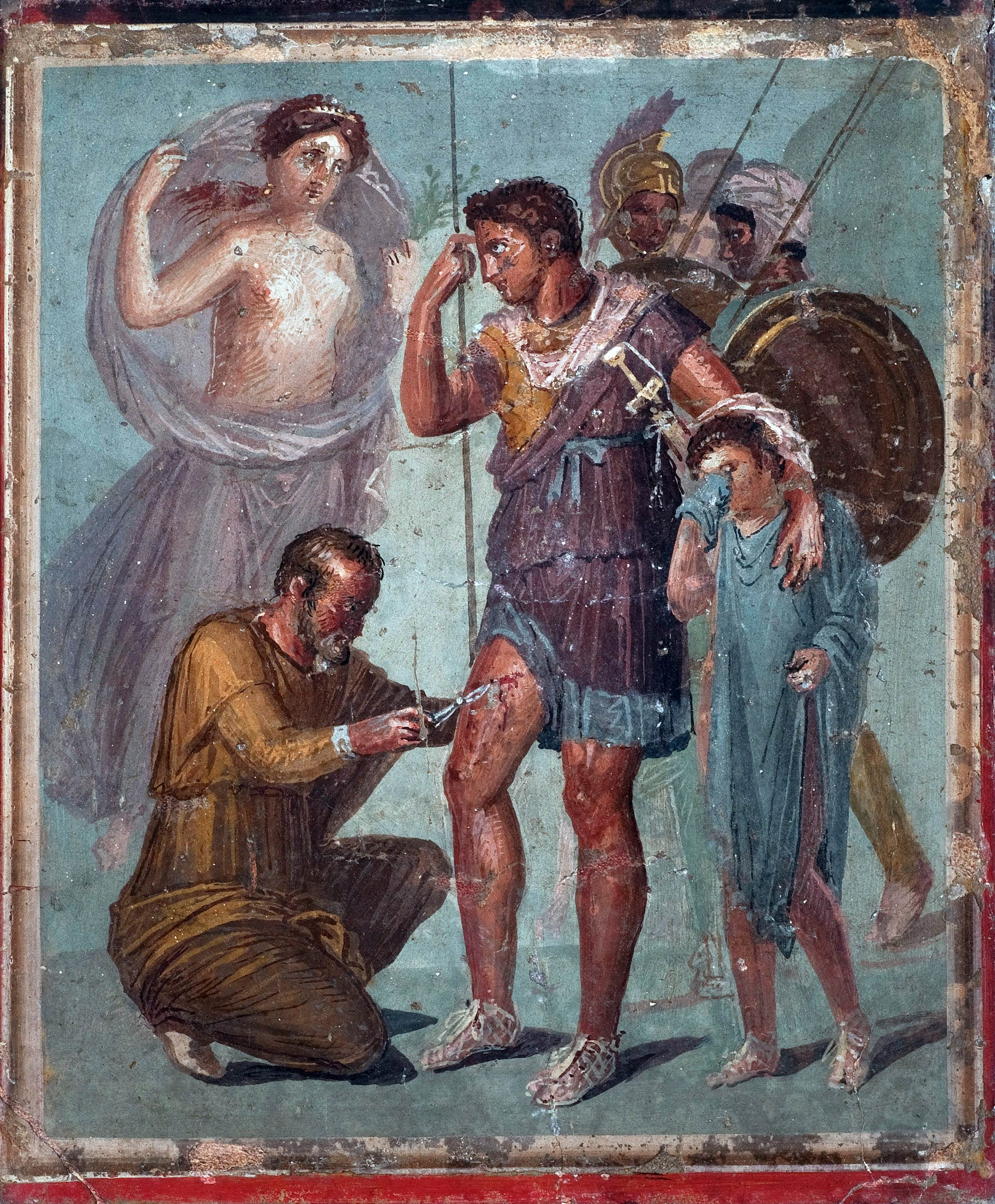

Aeneas, by this time, had been escorted back to the Trojan camp on the shoreline by his son and his old friend Achates. Aeneas wanted to be mended as soon as possible so he could throw himself back into the fray. A healer called Iapyx was on the scene to help. As the healer saw how deep the iron arrowhead was lodged into Aeneas’ flesh, sounds of screams and calamity came from the battlefield. Aeneas’ mother Venus helped the healer Iapyx make a special curative concoction, and moments later, the arrow was out, the wound was mended, and Aeneas was again ready for combat. As Aeneas prepared for more fighting, the healer marveled that it had not been him who’d patched Aeneas up.

Iapyx removing an arrowhead from Aeneas in a wall painting from Pompeii. That this relatively minor scene found itself into first century CE Roman wall art shows the sheer ubiquity of the Aeneid in the Roman imagination by this time!

Aeneas was ambushed by a tough Italian warrior as Turnus careened around the fighting. A vicious assault cost Aeneas nothing more than the plumes of his helmet, but even this small loss made his ever-increasing rage swell further. As Aeneas waded into the Italian army, Turnus killed Trojans from his chariot, attaching severed heads to its side. Aeneas killed four Italians. Turnus killed a pair of Trojan brothers, and then a young Trojan who’d never wanted to fight. Aeneas tore a huge rock from the earth and spun it around to kill a boastful Italian swordsman. Turnus speared a Trojan through the brain. Aeneas killed an Italian in spite of the Italian’s attempts to block his blows.

At this point, all pretenses of peacemaking were abandoned. Every faction of each army committed itself to fighting. And Aeneas, looking at the unguarded citadel of King Latinus, gathered his men around him.

These are my orders, [says Aeneas in the Oxford Frederick Ahl translation]. I want no delays. Here Jupiter stands firm.

No one must slacken his pace because plans have been shifted abruptly.

That city, cause of the war, very heart of Latinus’s kingdom,

This day, unless they concede to defeat, to our yoke, to obedience,

I will destroy, and I’ll level its heights to the ground and to ashes. (11.565-9)

It’s a surprisingly pitiless little sequence of lines, given that Aeneas himself has been on the receiving end of a siege and seen his home city fall. But, then, Aeneas is at this moment livid that he didn’t get to end the war by fighting Turnus, which was his original intention. The Trojans swarmed forward, straight for the city walls. Aeneas was screaming that the Italians had broken their treaty – he did not want to fight or subdue them – only to beat Turnus and stop the war. The statements had a divisive effect on Latinus’ city; indeed, some Italians thought Aeneas was justified in his attack.

Queen Amata watched Trojans spilling over the wall and onto the city’s rooftops. She blamed herself for what appeared to be the fall of her city, and, not wasting any words, she hung herself. Her daughter Lavinia found out about the suicide, and as the Trojans cut their way into Latinus’ city, so, too, did the news of the queen’s death spread. King Latinus wandered the city streets aimlessly, smearing dirt and dust into his white hair.

Out on the plain below the city, Turnus chased Trojan stragglers around in his chariot, but suddenly he saw it. The fighting was now raging inside the city. Warriors were cutting one another down up on the ramparts. At that moment Turnus’ sister spoke to him. The nymph said it was time for Turnus to flee – to rally new forces against the Trojans who were at that very moment taking King Latinus’ citadel. Turnus said that he wouldn’t. He knew who she was, he said. He knew she’d ruined the treaty. But he wouldn’t stand by while more of his friends were killed in combat. Another of Turnus’ comrades, just then, was struck in the face by an arrow. And this comrade – his name is Saces – gives what I imagine must be the longest speech in literature ever spoken by a man with an arrow stuck in his face. The dying Saces told Turnus of Aeneas’ great power – of how the queen was dead – of how only a few Italian captains still stood to deflect the wrath of the rampaging Trojan army.

Hearing this grim report, Turnus jumped down from his chariot and abandoned his sister. He ran toward the men fighting in the city like a giant boulder loosed from a mountainside. And, seeing how thick the blood ran at the base of the walls, Turnus screamed that it needed to stop. He said the treaty had been broken. But it was time for him to fight Aeneas. [music]

Turnus Prepares to Face Aeneas

Aeneas heard Turnus’ summons. For the second time that day, Trojans and Italians gathered around and found places to sit and stand to watch the champions fight. This was it. The clash took place not in the city, but on the plain below it. Before Aeneas and Turnus even came together they were trying to finish one another, each warrior’s javelins deflected by the other’s shield. And then they joined combat like a pair of goring bulls, the sounds of their swords and shields immense over the bloodied men standing to watch them. Turnus held his sword high overhead and delivered a powerful down stroke. But his sword shattered. He had had a sword forged by Vulcan, but in his haste to fight Aeneas, he’d left it behind.Realizing he was more or less unarmed, Turnus wheeled and fled. But he was wreathed by barriers – the Trojan army – the city walls – a thick marsh. Turnus screamed for his men to bring him his sword – Aeneas in response said that anyone who came close to the combat forfeited his life. The Trojan champion chased the Italian champion around the haphazard arena. Aeneas tried to free a javelin he’d thrown from a stump, but Turnus’ prayers to the god of the woods caused the javelin to be stuck fast. Soon, however, Turnus did have some help. His sister Juturna sped out in a chariot and brought Turnus his real sword. Yet again, the champions prepared to fight one another.

The Gods Plan the Duel’s Outcome

Only, at this juncture, Jupiter spoke to Juno privately. He said Juno had played a hell of a game. She’d made the Trojans’ lives truly awful up to this very moment, and in her desire for vengeance had spilled a lot of blood. But, Jupiter said, the game was up. Juno shouldn’t have got Juturna involved. Aeneas was, after all, fated to land in Italy, and that was it. He told her he vetoed any further actions against them.Juno said that she understood. She was done interfering. She only asked that when Aeneas won, and when Aeneas married Lavinia, that Latium could continue being the main culture on the central peninsula – that Italians continue to rule, and that Romans to be the heirs of Italian courage and fortitude. Jupiter, hearing these wishes, conceded everything. Jupiter said, in the Vintage Classics Robert Fitzgerald translation:

I grant your wish. I yield, am won over

Willingly. [Italian] folk will keep

Their fathers’ language and their way of life,

And, that being so, their name. The [Trojans]

Will mingle and be submerged, incorporated.

Rituals and observances of theirs

I’ll add, but make them Latin, one in speech.

The race to come, mixed with [Italian] blood,

Will outdo men and gods in its devotion,

You shall see – and no nation on earth

Will honor and worship you so faithfully. (12.1130-40)8

Painter Luca Giordano is careful to paint Turnus’ stolen belt in this famous seventeenth-century painting of Aeneas preparing to execute his defeated nemesis.

Upon the agreement being sealed, Jupiter had two agents of Tartarus appear on either side of his throne. One of the demons went straight for Turnus’ sister Juturna. Or more specifically, it went for Turnus, transforming itself into a bird and cawing and scratching in the Italian champion’s face. Juturna saw this and understood what it meant. Jupiter had decided who would win. The demons of Tartarus would be his enforcers. She couldn’t help her brother any longer. She did not want to live, and could not die, and so she tossed herself into the ocean.

Aeneas raised his spear and called to Turnus. He said it was time to stop running. Turnus nodded. He would fight Aeneas, but in that moment, Turnus added, it was Jupiter who was his real foe. Turnus picked up a huge boulder, and ran with it, and flung it toward Aeneas. But the boulder never reached its target. The demons sent by Jupiter had ravaged Turnus’ strength, and he had the sensation of being in a nightmare, his muscles feeble, his eyes rolling around in desperate futility. He looked at his allied armies and the city of Latinus. No one else was coming to help him. Turnus watched Aeneas cock his arm back and hurl a javelin. The weapon threw like a lightning bolt – like a tornado, cutting through Turnus’ shield and sinking into his thigh. The Italian champion went down onto a knee. He dropped his weapons and held a hand out, knowing it was over. And he said to Aeneas, in the Frederick Ahl translation,

I’ve deserved this,

Nor am I begging for life. Opportunity’s yours; and so use it.

But, if the love of a parent can touch you at all (for you once had

Just such a father, Anchises), I beg you to pity [my] aged

[Father], and give me, or if you prefer, my sightless cadaver,

Back to my kin. You’ve won; the [Italians] have witnessed the vanquished

Reaching his hands out to make his appeal. Now Lavinia’s your wife.

Don’t press your hate any further. (12.931-8)

Hearing these words, Aeneas stopped and hesitated. But a moment later, he saw that the great Turnus still wore young Pallas’ familiar belt. Back in Book 10, Turnus had killed Pallas, a youth whom Aeneas had only known for a day or two. And in spite of Turnus’ humble plea for his life, once Aeneas saw that belt, he made his decision. “You,” he growled, “dressed in the spoils of my dearest, / Think that you could escape me? Pallas gives you this death-stroke, yes Pallas / Makes you the sacrifice, spills your criminal blood in atonement!” (12.947-8). And with this imprecation, Aeneas stabbed Turnus in the heart. The Italian champion shuddered, sunk down with a groan, and died. [music]

The Aeneid‘s Famous Ending

I usually say, “And that’s the end” to close a grand story like this. These words give us closure and a sense of a text having finished transmitting its message. But in the case of Book 12 of the Aeneid, saying “that’s the end” would create a sense of culmination and completion that simply isn’t there in the poem. The last trio of lines in the Aeneid are hauntingly, and famously abrupt. Aeneas tells Turnus he’s killing Turnus for Pallas’ sake, “And, as [Aeneas] speaks, he buries the steel in the heart that confronts him, / Boiling with rage. Cold shivers send Turnus’ limbs into spasm. / Life flutters off on a groan, under protest, down among shadows” (12.950-3). The Aeneid ends with a hero killing a hero, with Aeneas in many ways becoming the murderous foreign invader he once fought during the Trojan War. And while I can’t properly give you a sense of just how hastily, and unexpectedly the Aeneid ends, I can tell you a bit about some responses to the poem’s famous ending.

This wonderful anonymous nineteenth-century portrait of Virgil captures the author’s simultaneous austerity and compassion, the high cheekbones and strong nose contrasting with surprisingly gentle eyes and delicate hair. It’s not too far from what I imagine the poet looking like, if people could look like their writing!

The story, like all ancient biographies of Virgil, is suspect. It’s almost certain that patches of the Aeneid are rough. The poem contains what we call “half lines,” or fragmentary lines that don’t fit with Virgilian meter.10 It has enough internal self contradictions in plot to suggest that indeed Virgil would have done well to iron out oddities involving, especially, King Latinus and his sentiments on the war, the exact role of fate in the story, the curiously unelaborated friendship between Aeneas and young Pallas, and other elements that have puzzled readers over the past two thousand years.

The ending of the Aeneid, particularly, has elicited a mixture of praise, criticism, and speculation. Scholar Joseph Farrell calls the summary execution of Turnus “surely one of the most sublime passages and most effective conclusions in all literature.”11 Many readers disagree. The Iliad comes to its climax with Achilles yielding to old King Priam’s heartbroken request for Hector’s body. The Iliad is about the wrath of Achilles – once this wrath is broken by a defenseless old father’s plea for his son’s remains, the whole arc of the 24-book long story draws to a logical, and even humanistic and optimistic conclusion – people from opposing factions can come to understand one another at a basic human level, and we are not doomed to suffer the sort of tribalistic violence that drove the entire Trojan War. The ending of the Aeneid is a different case altogether. Aeneas has a chance to let Turnus live, and to show clemency in front of the amassed population of Italians in front of him. Virgil’s reader understands that neither Aeneas nor Turnus wanted to go to war – not Latinus, nor King Evander, nor hardly anyone other than the diabolical Mezentius, who is already dead. And although Virgil’s reader knows that the entire war was divinely prompted by Juno, and although Turnus, throughout the epic, is only defending his homeland, as Aeneas did for ten years at Troy, Aeneas plunges his sword into the pleading man’s heart at the epic’s sudden conclusion. The ostensible reason is because Turnus has killed young Pallas, the son of Aeneas’ ally King Evander. But Aeneas and Pallas had only known one another for a day or two when the young man died a fair and normal combat death at the hands of Turnus, and so Aeneas’ bloodlust isn’t very easily accounted for.

Historical Reactions to the Aeneid‘s Ending

Since the Renaissance and before, many people have tried to make sense of the Aeneid’s bumpy ending. The ancient scholar Servius, writing around 400 CE, argued that Aeneas would have acted with piety in sparing Turnus, but that Aeneas also acted with piety in killing Turnus.12 Servius’ contemporary Tiberius Claudius Donatus came to a similar conclusion – Donatus wrote, “Notice, how, insofar as he wished to excuse. . .Turnus, the [piety] of Aeneas’ character is conspicuous. Also conspicuous is his devotion to Pallas, because his killer did not escape.”13 In both of these interpretations, Aeneas was in a double bind, with an obligation to be merciful to the helpless Turnus, but also an obligation to avenge the dead Pallas.

Dante matched his favorite poet Virgil’s discipline, erudition, and ingenuity as a poet. He did not, however, follow Virgil’s tenderness or concern for humanity. The portrait is Sandro Botticelli’s Portrait of Dante Alighieri (1495).

So, two ways early interpreters dealt with the Aeneid’s ending was to emphasize that the execution was as honorable as clemency might have been, and to emphasize that the execution was justified due to the historical events that it ushered in. But during the Renaissance there was another way that interpreters dealt with the Aeneid’s sudden ending. And this other way was rewriting it.

Fifteenth- and sixteenth-century Europe produced a number of add-ons to the Aeneid. The most popular of these by far was that of Maffeo Vegio, a fifteenth-century Italian poet who composed in Latin. Vegio’s thirteenth book of the Aeneid, completed in about 1428, was widely circulated and often included in manuscripts of Virgil’s Aeneid during the Renaissance. Vegio’s additional thirteenth book narrates the funeral rites of Turnus, and tells of the wedding banquet and marriage of Lavinia and Aeneas. After a flash forward, Vegio’s epilogue describes Aeneas’ death. Borrowing from Book 14 of Ovid’s Metamorphoses, Vegio’s sequel describes how Aeneas drowned in a river and then transformed into a deity. Vegio’s additional thirteenth book is meticulous in its efforts to replicate Virgilian Latin, and to depict Lavinia as a superior alternative to Dido. Lavinia never really makes an appearance in Virgil’s Aeneid, other than briefly showing up and saying nothing at the beginning of Book 12, and so Vegio takes care to depict Lavinia as a dignified maiden, with a quiet composure far different than Dido’s passionate imperiousness.

On one hand, Vegio successfully adds a denouement to the sudden and disconcerting ending of Virgil’s Book 12 – a sense of closure and continuity that Virgil’s epic lacks. On the other, it is a distinctly Renaissance, and not classical ending – an ending that scholar David Scott Wilson-Okamura calls “maybe perverse.”18 Renaissance epics, after all, feature romantic love to a considerably greater extent than Greco-Roman ones, and so Vegio’s passages about Aeneas blossoming with love for the demure maiden Lavinia are wildly out of place for a story written in the 20s BCE. However, again, Vegio’s additions were quite popular, and for readers of the generations of Ariosto, Tasso, Spenser and Sidney, the added book, with its culmination in a happy marriage, helped make the story’s ending more palatable. If you’re interested in learning more about this surprisingly influential thirteenth book of the Aeneid, I’ve created a free bonus episode all about it, and I’ll tell you how to get a hold of it at the end of this program. For now, let’s continue talking about the Aeneid’s end.

Twentieth-Century Responses to the Aeneid

In the twentieth century, early analysis of the Aeneid did not find it to be so problematic. Scholars, chief among them in the Anglophone world, T.S. Eliot, found the epic to be optimistic at its core – a validation of Augustus and his regime, and a poem ultimately about the triumph of order and civilization over war and primitivity.19 Eliot famously called Virgil a “universal classic. . .Our classic, the classic of all Europe” and a writer so great that Virgil proved “A classic can only occur when a civilization is mature; when a language and a literature are mature.”20 Other scholars agreed, concurring that Virgil’s original ending, while sudden, marked the necessity of European history’s grand march forward.As the twentieth century wore on, though, and particularly as America became divided over the Vietnam War, interpreters of the Aeneid began to wonder about Virgil’s own sentiments toward war in general. What we call the “Harvard School” of Virgil criticism, an important movement that began picking up speed in the 60s, saw the Aeneid as considerably more ambivalent toward war than the epic had traditionally been interpreted. Scholar Adam Parry, in 1963, argued that the Aeneid was written with a pair of very different voices – a voice of public admiration for Augustus and before him Aeneas, and then a voice of personal loss and lamentation at the tragedy of war.21 Following Parry’s influential essay, the next year classicist Wendell Clausen demonstrated that the ostensible message of victory emblazoned throughout the Aeneid is counterbalanced by a widespread sense of loss and failure.22 The year after – in 1965 – scholar Michael Putnam read Aeneas’ killing of Turnus at the poem’s climax as a tragedy – or, at best, a tragic victory.23 Collectively, this new school of interpretation considered the Aeneid’s ending both in the context of the early Augustan regime and in the context of the American 1960s and 70s.

I don’t often give critical histories like this – they seem to me to belong more in a graduate seminar than an introductory podcast. But there has been, for 2,000 years, now, a general sense that the Aeneid’s ending is problematic and jarringly sudden, and various writers have tried to make sense of it. Some have said that Aeneas’ execution was honorable and necessary to justify his acquaintance’s death. Others have said that Turnus had to die to turn the motor of European history. Others still have augmented the poem with novel endings that speak to their own cultural expectations. And today, following the Harvard anti-war school of the 1960s, a common assessment is that the ugliness of the Aeneid’s ending is Virgil’s own, genuine, coldly equivocal statement about Augustus and the totalitarian peace he instigated in the years that the Aeneid was being composed. As the Aeneid draws to a close, just as was happening in the 20s BCE, a long period of ugly and often preventable carnage had come to a conclusion. A ruthless victor had butchered a man who had opposed him. History had grinded forward at the expense of countless innocent lives. And in spite of the new peace, and the clear culmination of an awful war, the average citizen of the Italian peninsula, while Virgil was writing the Aeneid, might have seen Augustus just as ambivalently as we see Aeneas in the closing lines of the poem.

In Book 6, when Aeneas is in the underworld meeting with his father, old Anchises tells Aeneas what it means to be a Roman, describing the characteristics that Aeneas’ descendants will have. Anchises tells his son that Romans will be characterized by “Mercy for those cast down and relentless war upon proud men” (6.852-3). The two directives in this line – mercy for the vanquished and war upon the proud, give Aeneas contradictory orders in the closing seconds of the Aeneid. He is supposed to offer clemency to defeated foes. He is also supposed to attack proud foes relentlessly, and Turnus is frequently described as “proud” throughout the epic. With more impetuosity than careful forethought, then, with a traumatized anger borne of almost two decades of warfare and diaspora, Aeneas follows one of his father’s orders while ignoring the other. He could not have done both. And though he has become a ruthless killer by the Aeneid’s conclusion, circumstances and sufferings have driven Aeneas to this dark end, far more than Greek heroes like Diomedes, Ajax, and Achilles, who kill for personal glory more than home and family.

The “Slaughter-Bench” of History and the Virgilian Worldview

Virgil ultimately never lost sight of the plight of the common person over the 51 years of life that he lived between 70-19 BCE. His mythological opera, as readers have noticed since the mid twentieth century, contains inescapable undertones of sadness in every book, and in the general order of events. The painting is Jean-Léon Gérôme’s Cave Canem (1881).

The German philosopher G.W.F. Hegel, in his Philosophy of History, once asked, “[R]egarding History as the slaughter-bench at which the happiness of peoples, the wisdom of States, and the virtue of individuals have been victimized – the question involuntarily arises – to what principle, to what final aim these enormous sacrifices have been offered.”24 To Hegel, if you happen to know his work, this final aim is the geist, or world spirit working out its all-governing agenda through the machinery of the dialectic. Blood might be spilled, but, as this famous line of nineteenth-century German philosophy directs us to believe, the slaughter-bench of history, with great men like Caesar and Napoleon wielding the meat cleavers, guides humanity ever forward through increasingly advanced phases of historical development. Reading Hegel, Virgil might have thought of the stoic logos, or cosmic reason that drove the unfolding of world events, and in some ways Hegel’s theory of history is little more than an elaborate nineteenth-century rehearsal of stoic historicism, deployed for an era of Christian constitutional monarchies. But to return to Virgil himself, and the shocking closure of the Aeneid, through Aeneas Virgil is able to tell Augustus’ story, and to sanction the emperor’s dominion as unassailable. And yet at the same time, Virgil wants us to remember, in passage after passage, that the Roman Empire was born out of war and contradiction; out of cutthroat egotists and frenetic turmoil, and not at all the graceful advance of fate, whether this fate is Jupiter, or the stoic logos, or icy rationalism of the Hegelian world spirit. A great student of philosophy himself, Virgil nonetheless refused to dismiss the human cost of Roman warmongering as grist to the mill of history. While readers like Dante, and Tasso, and T.S. Eliot have read the Aeneid favorably as a piece of providential nationalism, and while twentieth-century critics often reviled the propagandistic elements of the poem, we have to remember that the Aeneid comes to its shattering climax with a severely critical portrait of Augustus. The emperor, Virgil admits, is resourceful, large, and in charge. But he is also no different than anyone who opposed him; he is a traitor to Roman virtue just as much as he is the embodiment of the new era, and he is stained down to the soles of his shoes with the blood of those who opposed him, and those who supported him. [music]

Loose Ends in the Aeneid‘s Second Half

From this ery brief reception history of the Aeneid, we could call it a day. My analysis above – that Virgil overall communicates ambivalence about the birth of the Empire, is a fairly standard contemporary take on the poem’s ending – one that wouldn’t surprise any modern classicist. What I want to do now is look at a smattering of loose ends from the later books of the poem. I think that the suddenness with which the story ends was no accident – that Virgil wrote the finale that he wanted. But nonetheless, to a careful reader, there are many other moments late in the Aeneid that perhaps would have benefited from a bit more authorial reworking.

At certain moments of relentless fighting late in the Aeneid, the fervor for violence and simultaneous desire for peace, even considering the actions of Allecto in Book 7, seem difficult to understand. The painting is Peter Lastman’s Battle of the Milvian Bridge (1613).

We just talked about how various generations have tried to salvage the ending of the Aeneid, either by excusing Aeneas’ execution of Turnus, actually rewriting the ending, or interpreting the poem’s ending as an anti-war statement. In fact, throughout our four episodes on the Aeneid, we’ve spent a lot of time looking at what we might call the problems of the poem. One of these was the strange and horrendously written narrative of how Aeneas lost his first wife on the way out of Troy. We looked at the many moments in Books 1-6 at which Virgil shapes Aeneas’ journey to Carthage, and Aeneas’ journey to the underworld in order to offer hat tips to Augustus. Just last time, we discussed the slovenly way the Aeneid references fate – sometimes it is the will of Jupiter, sometimes it is something that Jupiter must bow to; sometimes it is avoidable, and sometimes not; sometimes, it is heroism to try and break the manacles of fate, and at other times, it is impious. These are not problems that we bring to the epic with our modern sensibilities – they are internal lumps and often glaring, distracting inconsistencies that slow even a patient and forgiving reader’s progress through Rome’s most famous story, regardless of that reader’s generation.

And they come to a climax in the closing three books of the Aeneid. The war story that dominates the epic’s end is often so unevenly delivered that it is often hard to discern the most basic motivations of the story’s principal characters. To me, in a sentence, one of the most perplexing aspects of the last three books of the Aeneid is the utter precipitousness with which the war begins, climaxes, and concludes. The war in Italy, a month in duration at maximum, has no long history behind it, and almost no human motivations. It’s stirred up by Juno, merely because she wants to cause pain and suffering to the men and women who live almost a thousand years before the Punic War whose distant descendants will beat Carthage. Books 7, 8 and 9 unfold in an ugly murk of divinely prompted animosity, and Books 10, 11, and 12 show mass murder rushing through central Italy with all the gore and fury of the Iliad. The problem is never with the surface of Virgil’s poetry, which is reliably sonorous and beautiful. The problem that increasingly manifests itself in the second half of the Aeneid is that there is a level of ferocity and violence that is incommensurate with the events that have supposedly prompted it. Let’s look at an example.

Turnus isn’t the first helpless Italian that Aeneas brutally executes. An earlier Italian fighter – this one called Tarquitus – is beaten down until he begs for his life at the feet of the Trojan hero. Declining to be merciful, Aeneas slices off Tarquitus’ head. We haven’t heard much of Tarquitus, and neither has Aeneas. He doesn’t seem to have done anything to warrant such an unmerciful killing. Nonetheless, after decapitating his foe, Aeneas growls,

Figure of terror, now lie where you are. Your wonderful mother

Won’t ever bury your limbs in the family tomb. You’ll be either

Left here as food for the carrion birds or flung to the surging

Seas where your wounds will be nibbled by starving fish as your corpse drifts. (10.557-60)

Now, any Latinist would remind us that the name Tarquitus, to Virgil’s Roman readers, would call to mind the name of Lucius Tarquinius Superbus, the last king of Rome, an execration to the entire republican system of government. But they are not, by a long shot, the same person – the hated Roman king lived twenty generations or so after Aeneas did, and so when Aeneas chops the stranger’s head off and delivers an Achilles-like death curse to him, we wonder what the stranger has done to deserve such an awful summary execution. You could explain it away by saying that maybe Virgil is trying to differentiate Augustus from Tarquinius Superbus – an new king with an old king – by showing Augustus’ ancestor Aeneas murdering Tarquinius’ ancestor Tarquitus. But that doesn’t explain the fact that amidst the events that have taken place in the story, Aeneas has no discernible motivation for killing a helpless man begging for his life.

The Death of Camilla (1879) by Bartolomeo Pinelli. Camilla’s entrance and rather hasty foreordained death seems a clunky set piece in Book 11, as we’ve heard nothing of her before and are immediately told what will happen to her.

Midway through Book 10, just after Pallas’ death, Virgil addresses Turnus directly. “[I]n a rage,” Virgil writes, “[Aeneas] seeks you out, Turnus, / Proud of your latest slaughter. It’s all there: Pallas, Evander / Clear in his mind’s eye; the first bread they broke when he came as a stranger; / Handshakes of treaty and friendship” (10.514-7). It’s all there, Virgil emphasizes –from the moment he came to know the young man, after a vast acquaintanceship of – uh – one or two days. Virgil does give Aeneas a friend very early in the epic – in Book 1 Aeneas’ Trojan friend Achates accompanies him from the ships to the city of Carthage. But Achates is hardly onstage thereafter, making occasional appearances here and there. Pallas, on the other hand, ends up being the epic’s inexplicable pivot – the reason Aeneas throws himself into the war with unstinting brutality, and the reason he kills the relatively inoffensive and likable antagonist, Turnus. Pallas gets an incredibly long funeral sequence at the beginning of Book 11. He is, more than young Iulus, or Dido, or Lavinia, or Latinus, or the foundation of Rome, increasingly the only thing Aeneas thinks about as the epic rumbles toward its abrupt climax – this Greco-Italian youth with whom the hero spent just a couple of days.

There are some explanations for why Pallas takes on such a sudden importance to Aeneas. One is that the two men became lovers, although there isn’t any clear textual evidence for this. Another explanation is that Pallas is an analog to Augustus’ nephew, Marcellus, who is mentioned toward the end of Book 6, when Aeneas sees him in the underworld. Both young men showed great promise and died young, leaving behind them kingdoms with no clear path of succession. Another still is that typologically, Virgil is imitating the central sequence in the Iliad, in which the death of Patroclus spurs Achilles into his final and famous rage, although Achilles and Patroclus have a lot more history than Aeneas and Pallas. Whatever explanation we try to fasten onto Pallas’ sudden centrality in Aeneas’ imagination, the fact remains that the two men could have hardly known one another.

Notwithstanding the rough spots of the poem’s closing books, which likely could have benefited from some editorial work on the part of Virgil if the poet had lived longer, the story remains captivating up to its final, startling lines. As I said earlier, by the 20s BCE, writing a Homeric epic was a difficult enterprise. Virgil’s world included the old Olympian pantheon in addition to the advanced philosophy of Aristotle, the stoics, and the Epicureans. His literary influences included the epics of Homer and Apollonius of Rhodes, but also the condensed neoteric poetry of Catullus, and before him Callimachus. Virgil’s obligations as a servant of a patron were to mythologize and validate the monarchy of Augustus; his obligations as a poet were to tell a great story. And since he’d almost lost his family estate in 40 BCE during the Second Triumvirate’s land grabs, throughout the course of his decades-long acquaintance with Rome’s first emperor, Virgil must have extremely complicated feelings for Augustus. Seven years older than the emperor, and having witnessed his younger contemporary’s entire life and violently ambitious career, it’s hard to imagine that Virgil wholly bought into any notion that Augustus was the savior of Rome.

In setting out to write the Aeneid, then, Virgil had an almost impossible task. He had to weld the story of Aeneas together with the one of Romulus and Remus, tales that came from independent traditions and took place over four hundred years apart from one another. He had to flatter the man who bankrolled his project, somehow taking the life of a first century BCE autocrat and relating it to a legendary war that had taken place almost 1100 years prior, and stapling this story to the one that Livy tells in his history of Rome, which begins not with the Trojan War, but instead 400 years later, in 753 BCE. He had to follow the Homeric traditions of using the Olympian pantheon, even though newer doctrines like stoicism and Epicureanism denied the intervention of the deities in the human world. He had, as I said before, to write an extremely long narrative poem when most of his experience had come from writing short works. That he was able to create something out of this jumbled pile that was loved in the Roman world and endured long afterward is a testament to his great tenacity.

In Angelica Kauffman’s Virgil Reading the Aeneid to Augustus and Octavia (1788) the poet stands on the margins, fragile and vulnerable to the Princeps’ whims. The scene depicted here is Virgil reading a reference about Marcellus to the royal family and upsetting the dead boy’s mother, but really every hexameter in the poem may have been subjected to imperial scrutiny.

In coming to the end of the Aeneid in this program, we have actually finished every surviving work that Virgil wrote. And having spent the some time with his work over this past year – biography, history, secondary scholarship, and of course the Eclogues, Georgics and Aeneid – I want to leave you with an image of the writer as we move forward, before too long, into the Middle Ages.One of the things we admire today in artists – particularly since the Romantic period – is originality and departure from conventions. We appreciate artists who turn a corner from an evolutionary line, who create something fresh and novel, who fly in the face of tradition with their confident innovations. This way of thinking about an artist’s role is relatively new. And as I’ve researched and written a number of shows on the Augustan Age poets – from Horace to Ovid, I’ve been struck at the extent to which, throughout most of literary history, what has been sought after the most hasn’t been novelty so much as it has been recombination. From Virgil’s first eclogue to the last verses Ovid wrote while exiled at the end of his life, Augustan age poems are often like bird’s nests – careful weaves of repurposed materials, with an original strand here and there, certainly, but always a mesh of innovative and reprocessed elements.

The Aeneid will always be divisive. The fact that it was written for a patron and at several junctures celebrates that patron’s bloody victories and lust for power is a hard pill for the modern reader to swallow. Some of the poem’s internal discrepancies, particularly in the second half, might have benefited from a tidying up that Virgil was never able to perform. But to me, the Aeneid, especially as a flawed poem, is a perfect and fitting record of the birth of the Roman Empire. This empire was born at the cost of a catastrophic number of Roman lives. Its promise, peace, came at the betrayal of the one thing that the republic had always cursed – monarchy. Its early leaders had lost fathers and brothers in twenty years of civil war, and as they bowed to their new overlord, they remembered their relatives who had died for Pompey, who had died for Caesar, and then Cassius and Brutus, then Sextus Pompeius, then Antony, a procession of land and sea battles that whittled Rome into a battered nub while Octavian greedily gathered the wood shavings. During the 20s BCE, Virgil knew that Augustus had brought with him peace. But he also knew that this peace came at the cost of a two decade long military coup that had successfully broken Rome’s leadership and usurped it. It’s no wonder, then, that all of Virgil’s poetry is a chiaroscuro of hope and bitter darkness. The singing herdsmen of the Eclogues tramp through dewy grass, but their songs are often raw and dejected. The orderly, graceful fields of the Georgics are overhung with a sense that work is futile, and nature and civilization are equally unstable. And the Aeneid, most of all, is a mirror of the times in which Virgil lived. It is a story where past, present, and future don’t quite line up. It’s a story in which the wise, the passionate and the vulnerable – Anchises, Dido, and Pallas, are steamrolled by the stoic forward march of autocracy – Aeneas, and over him Jupiter. It’s a story with tragic turns and disappointments, which begins with a storm and ends with a dispassionate overlord standing bloody and unopposed over the corpses of his foes. The Aeneid, much like Augustan poetry, is a bird’s nest of tropes and personages twined together through poetic expertise. But the Aeneid is also a lamentation, the cracks and fissures in its foundation perhaps serving as evidence that even Rome’s most famous poet could not make sense of, or justify the dark and grim history that he had endured. [music]

Moving On to Propertius and Latin Love Elegy