Episode 58: She Caught Me with Her Eyes

Propertius (c. 50-1 BCE) took the Latin elegiac form to new heights of complexity and passion, even weaving subtle satire throughout his work.

| Read Transcription | References and Notes |

| Episode Quiz | Episode Song |

| Episode on Spotify | Episode on Apple Podcasts |

| Previous Show | Next Show |

The Poetry of Propertius

Hello, and welcome to Literature and History. Episode 58: She Caught Me with Her Eyes. This episode is on the Roman poet Sextus Propertius, who was born in about 50 BCE and died some time before 1 BCE – the exact chronology is uncertain. Propertius was one of the younger Augustan Age poets. Today, he is most famous as a love poet – a more tempered successor to his predecessor Catullus, with a wide variety of poems written to a single addressee, but lacking, for the most part, Catullus’ ferocity and profanity. And like Catullus, Propertius wrote more than love poems. Propertius’ four books of poems, put into circulation between 29 and 15 BCE, include a wide assortment of themes and topics – Roman history, for instance, contemporary social norms, mythology, and literary theory, to name just a few.1The Life of Propertius

Propertius was born just before Julius Caesar’s civil war erupted in 49 BCE. Virgil, who was born in 70 BCE, and Horace, born in 65, were among the last Roman poets to have been alive while Rome’s republican government was still operational. Propertius, however, and after him Ovid, grew to adulthood during Rome’s civil wars – Caesar against Pompey, then Octavian and the Senate against Antony, then Octavian and Antony against Brutus and Cassius, then Octavian against Fulvia and Lucius Antonius, then Octavian against Sextus Pompeius, then Octavian against Antony and Cleopatra. Propertius’ first two decades were witness to all of these conflicts, a bloody and morally murky period during which, as we have seen in the poetry of Horace and the Eclogues and Georgics of Virgil, the average citizen of the central Mediterranean was just trying to keep his head down and survive. Propertius spent his twenties in the 20s BCE – the first decade Rome was under Augustus’ leadership. The majority of Propertius’ poetry is calculatedly apolitical, but a number of important poems that Propertius wrote do engage, often subversively, with Augustus’ reign and his policies.Before we get into the complexities of Propertius and what he made of the history he lived through, let’s go over the biographical information we have about him. Propertius was from the north central part of the Italian peninsula, about fifteen miles southeast of modern day Perugia, and about seventy miles north of Rome as the crow flies.2 He was, like Virgil, Horace, Catullus, and Cicero, a provincial, and he shared Cicero’s status as an equestrian. When Propertius was about nine, something happened which also affected Virgil and Horace, and this was the property confiscations that Octavian undertook in 41 BCE. What happened – and maybe you’ll recall this from prior episodes – what happened was that following the violent campaign seasons of 43 and 42, Octavian needed to settle his military veterans. Italy was all blocked up, though. And rather than settling his veterans in the provinces, Octavian took the extremely controversial step of deporting citizens from at least eighteen towns throughout the Italian peninsula. Whole populations of townspeople were forcibly uprooted. Virgil, at this point, was about 30, and Horace about 23, and the intervention of one of the consuls of 40 BCE helped insulate the two young poets from the financial disaster of losing their family estates. Propertius was in a slightly different condition.

First of all, Propertius was only nine or ten when these land grabs took place, and thus he was not in any position to try and broker a deal with anyone to try and safeguard his parents’ land. While he was only a child in 41 BCE, the experience of having his family property threatened was still with him 25 years later, when he released his fourth book of poems. In this book, one of Propertius’ speakers tells the poet himself to recollect how, in the Oxford World Classics Guy Lee translation,

Too young for such gathering you gathered your father’s bones

And were yourself reduced to hard-up [circumstances].

Though many were the steers that ploughed your country estate

The ruthless rod annexed your landed wealth.

Anon, when the golden locket left your callow neck

And you donned freedom’s toga before your mother’s Gods,

Apollo then dictate[d] you fragments of his song

Forbidding you the Forum’s verbal thunder. (4.1.127-34)3

In these lines, Propertius recalls the death of his father and the dissolution of his family estate, and how he felt the calling of a poet early in life, rather than the thunderous oratory of the Roman forum. The land grabs of 41 BCE affected different poets in different ways. Horace, who was the son of a freeman, seems to have been struck more catastrophically than Virgil or Propertius, who were equestrians and may have had other means of income than agricultural production. A line from Propertius’ second book of poems describes his social and financial situation around 25 BCE when the poet was in his mid twenties. Propertius wrote, “Consider me, the heir to a modest patrimony, / With no ancestral Triumphs in past wars” (2.34.55-6). In other words, Propertius didn’t have any great military or political heritage, but he had an annuity that he could fall back on if all else failed.

While we don’t have much more biographical information on Propertius than what I’ve just told you, what we know about him invites us to pause for a second here and consider the financial production of Roman literature in a bit more detail. Back in episodes 42-4, we met the earliest Roman writers – Livius Andronicus, Quintus Ennius, Gnaeus Naevius, Plautus, and Terence. Rome’s early authors were not aristocrats – they were a mixture of former slaves and foreign polyglots who were able to transpose Greek literature into Roman scrolls and stages. While Terence may have enjoyed some aristocratic patronage, Plautus seems to have been a professional writer through and through, making money only for his productions. Horace, looking back on Plautus about a hundred and seventy years after the playwright’s career, made fun of Plautus for living from play to play. Horace writes in one of his Epodes, “[H]ow loosely [Plautus]. . .careers over the stage; for he can’t / wait to put the coins in his cash-box, not worried after that whether / his play falls flat or stands on firm footing” (Ep 2.1.175-6).4 It’s an interesting quote, this snippet from Horace, and it shows that by the 20s BCE, even the humblest Augustan Age poet thought that it was vulgar to openly write for money. To Horace, you could make admiring remarks about your patron, and your patron might now and again do something nice for you. But the interchange of cash for literature, when Propertius came of age, was no neat one-to-one process.

Propertius and Virgil, and before them Catullus, were men with respectable backgrounds and patrimonies, and generally over the course of the first century BCE we begin to see the production of Roman literature as an upper class activity. The poets of this century certainly had financial incentives to flatter patrons – I don’t mean to say that patrons like Memmius, Cornelius Nepos, and later on Maecenas and Messalla didn’t offer generous material rewards for poets whose work they found agreeable. But even a writer with an independent income, like Propertius, stood to benefit from paying lip service to a powerful patron like Maecenas. Because even if Propertius didn’t need a paycheck from Maecenas, Propertius could still benefit from Maecenas’ network. In public readings at Maecenas’ house and a number of other venues in Rome, a poet could gain prestige and circulation. And also, in such public readings, a poet could appear distinguished and glamorous, winning for himself new friends and lovers. Earlier, we heard Propertius ask an addressee to “Consider me, the heir to a modest patrimony, / With no ancestral Triumphs in past wars.” The next line is “How I am king among the many girls at parties” (2.34.57). Propertius, however stable his income was, still found that cultivating friendships with Rome’s aristocracy allowed him access to all sorts of advantages and pleasures, not all of them financial.

Rome’s patronage system was complex, and involved exchanges of all sorts of favors and opportunities on all sides. There was never a phase in the first century BCE when poets glorified their patrons through and through for cash – and by the Augustan age, each major poet’s corpus is a mixture of patriotism and subversion, gratitude for the peace Augustus ushered in but also horror at the price paid for that peace. In Virgil’s Eclogues and Georgics we see violence and gloom haunting the periphery of the poet’s rural landscapes, and in the Aeneid, generations of readers have found evidence of the poet’s loathing for war and monarchy.5 In Horace’s work, we find laudations of Augustus back to back with diatribes against the wars that Augustus waged. Augustan age poetry is often like a bright fountain covered with an oil slick – a joy at the wealth and stability of the present often stained with murky memories of the recent past.

Because Propertius was born nearly a generation after Virgil and Horace, and because his memories of the civil wars and land grabs of the 40s and 30s were less vivid and complete, Propertius’ oeuvre of work has a slightly different sense of contemporary history. As classicist Oliver Lyne writes, Propertius’ “family was equestrian in his own time – very possibly senatorial in the next generation – and there is no sign that the poet was ever burdened by the need to earn a living. His spirit was naturally independent and irreverent, but it was buttressed by the confidence that money and class tend to bring.”6 Horace and Virgil witnessed Octavian’s rise and the wars that made him Augustus, losing friends in these wars and enduring the systemic instability of the dying republic during the two Triumvirates. Propertius, on the other hand, would have heard of Julius Caesar’s death and Octavian’s ascension when he was just six. While he shared the older poets’ dismay at Octavian’s shocking violence and greed, Propertius continued – although subtly – to write about Octavian’s political and legislative activities well after Octavian became Augustus – in the 20s and 10s BCE.

What I want to do now is tell you a bit about Propertius’ political work. It’s kind of an odd place to start, as Propertius is generally known as a love poet. But I think if we begin by getting a sense of what Propertius thought about the time in which he lived, we’ll be better equipped to understand why this younger Augustan age poet spent so much time devoting his energies to love poetry in the first place. [music]

Propertius and the Massacre at Perusia

When Propertius was about nine, he had a front row seat for one of the more gruesome events in the civil wars that killed the republic. This event was the end of what we call the Perusine War. The Perusine War began in 41 BCE. Although Octavian, Mark Antony, and Lepidus had formed the Second Triumvirate back in 43, Mark Antony, and particularly his wife, Fulvia, thought that Mark Antony ought to be the sole ruler of Rome, and not share power with anyone. To this end, Fulvia and Mark Antony’s brother, Lucius Antonius raised legions in Italy and marched on Rome.7 They held the city briefly, but were beaten back by Octavian, who drove Mark Antony’s wife and brother north, to the city of Perusia. Mark Antony himself was in the east during this period – first in modern day Syria, and then later in Egypt.What happened in Perusia was a black mark on Octavian’s reputation for the rest of his life. There was a siege during the winter of 41-40 BCE. Young Propertius, who lived about 15 miles to the southeast, would have heard of this siege.8 The siege of Perusia ended in 40 BCE due to the starvation going on behind the city walls. Octavian pardoned Mark Antony’s wife Fulvia, and Antony’s little brother Lucius Antonius. But Octavian ordered a general massacre of the citizenry of Perusia. Following the slaughter of Perusia’s inhabitants, on March 15, 40 BCE, the four year anniversary of Julius Caesar’s assassination, Octavian had 300 Roman senators and equestrians who’d been involved in the war on the opposing side rounded up and ritually executed in front of an altar to Julius Caesar.9 It was an egregious retribution even in the context of the late republic’s civil wars, this joint killing of citizens, equestrians and senators – an act of sickening mass slaughter that Julius Caesar would likely not have condoned. Following the killing of 300 senators and 2,000 equestrians that had taken place in late 43 and over the course of 42, the homicide in the early spring of 40 BCE showed the general population of the Italian Peninsula that the new wave of Roman strongmen had no regard for innocence or guilt, and that no one was safe from mass murder at the hands of an aspiring king. Human sacrifice – of Roman citizens, no less – was a new low.10

Propertius, as I said, lived just fifteen miles away from the site of this atrocity. And two of his more famous and historically anchored poems deal with the siege of Perusia in detail – poems that Propertius had completed by around 29 BCE. In the first of the two poems, Propertius takes on the voice of a man named Gallus – a man who may have been his brother-in-law.11 This Gallus was involved in the campaign at Perusia on the side that opposed Octavian. Let’s hear Guy Lee’s translation of this poem, again in which Propertius is assuming the voice of a soldier killed at Perusia.

“You who hurry to avoid a kindred fate,

Wounded soldier from the Etruscan lines,

Why at my groan do you roll those bulging eyes?

I am your closest fellow-campaigner.

So may your parents celebrate your safe return;

Let your sister learn what happened from your tears:

That I, Gallus, rescued from the midst of [Octavian]’s swords,

Failed to escape from hands unknown;

And of all the scattered bones she finds on Etruscan hills,

Let her know that these are mine.” (1.21.1-10)

Whoever this Gallus was, real or imaginary, he suffered a harrowing fate, escaping the purge and human sacrifice of Octavian but dying anyway. It’s a cryptic poem in some ways, a soldier’s record of a failed campaign, and a description of the turf around Perusia being littered with human remains. The poem’s speaker, like Propertius himself, was Umbrian, and from the lowlands southeast of Perusia. While the poem makes no explicit statement about Octavian’s mass executions, at the least we can imagine the twenty-year-old Propertius thinking back to events that had taken place a decade before and realizing how close he’d come to being a casualty of Octavian’s bloody ascent to power.12

The very next poem in this same collection – in fact the final poem in Propertius’ first book, also ruminates on the Perusine War. And in this second Perusine War poem, Propertius speaks with his own voice to his acquaintance Tullus, who has evidently asked to know more about the poet’s background. Here’s Propertius’ second poem related to the Perusine War, in the H.E. Butler prose translation this time.

Tullus, [you ask] ever in our friendship’s name, what is my rank, whence my descent, and where my home. If [you know] our country’s graves at Perusia, the scene of death in the dark hours of Italy, when civil discord maddened the citizens of Rome (hence, dust of Tuscany, [you are] my bitterest sorrow, for [you have] borne the limbs of my comrade that were cast out unburied, [you shroud] his ill-starred corpse with never a [covering] of earth), know then that where Umbria, rich in fertile lands, joins the wide plain that lies below, there was I born. (1.22)13

The poet can’t seem to think anyone will recall anything about Perusia other than the violence that unfolded there in the spring of 41 BCE. To Propertius, the siege and executions of Octavian were the definitive event that marked his homeland. I think it’s significant that, in an initial book of poetry generally made up of love poems to an aloof mistress, Propertius concludes with a recounting of his homeland’s most horrific hour. The opening poem of his second book also recollects the barbarities at Perusia – Propertius recollects “the overthrow of the hearths of the old Etruscan race” (2.1.29) as one of Augustus’ doings. Propertius, as he wrote his first two books, knew that he might have survived, and made it to Rome to flirt at parties and pursue a dazzling courtesan. But he never forgot the bones of his dead provincial neighbors, nor the events that had put them there. [music]

Augustus’ Political Changes During the First Principate

In our programs on Augustan Age poetry we’ve talked far more about the history of the 40s and 30s than the history of the 20s, 10s, and beyond. Since we’re covering Propertius in this episode, and Ovid in the next six, and since these two men spent the majority of their lives under the reign of Augustus, it’s worth talking about the emperor’s actual reign, which lasted for an astonishing period of almost 45 years, from the victory at Actium in 31 BCE up until his death in the summer of 14 CE.

Augustus changed the engineering and operations of the Roman senate tremendously over the course of his 40+ years in power. The painting is Cesare Maccari’s Appius Claudius Caecus in the Senate (c. 1881-8).

One of the most effective ways that Augustus gathered power during his reign was refashioning the personnel and operations of the senate. The civil wars of the 40s and 30s cut down and in some cases eradicated a number of powerful senatorial families, and Julius Caesar had shocked Rome by adding men from Cisalpine Gaul and regions even further afield to what had previously been a more regionally and ethnically insular senate. Augustus continued the trend, adding senators from present day Spain and France to the senate’s roll sheets. By 30 BCE, the senate had swelled to a thousand men, and over the course of the 20s, Augustus raised the required wealth for senatorial rank from 400,000 sesterces to 1,000,000 sesterces. He also cut 300 men from the senate over this same decade, earning animosity while at the same time making sure that the main political body of Rome was loyal to him. As the opening decade of his rule drew to an end, Augustus became the main gateway to the senate, taking for himself the right to award senatorial and patrician status.

So much power concentrated in the hands of one person changed the way that the senate operated. In Cicero’s day it was a free-for-all of rich men generally trying to become richer and more powerful. In Augustus’, senators competed not so much for the passage of laws as they did for the favor of the emperor himself. Because so much was to be gained by kowtowing for Augustus’ good will, the emperor was able to restructure the governing body in ways that streamlined his control over it. He created an inner senatorial commission made of him, his right hand man Agrippa, the year’s two consuls, a praetor, an aedile, a quaestor, a tribune of the plebs, and fifteen handpicked senators. Lower ranking officials from this commission were swapped every six months, and the commission became a powerful instrument for overriding any challenges to measures Augustus wanted ratified. And by 5 BCE, Augustus took the astonishing step of requiring four consuls per year – two for the first half and two for the second half. On one level, doubling the quantity of consuls ensured that more aristocratic men would have the mark of highest office on their resumes. At the same time, however, shortening consular terms made it much more difficult for Rome’s consuls to get anything done. By hand picking who was in the senate, shortening consular roles, and using a powerful inner commission to undertake his political operations, Augustus increasingly made the republic’s ancient offices into a set of meaningless nametags that were written, bestowed, and removed, exclusively by him.

Since we’ve heard about the land grabs and the human sacrifices at Perusia that happened in the late 40s, and just now about how he tweezed power away from the senate during the first two decades of his reign, it’s important to also emphasize some of the actions Augustus took that were more generally for the public good.

Infrastructural Changes Under Augustus

Before he took the mantle of Augustus, Octavian had already had frantically busy career. He had enjoyed an excellent education, travelled widely, gained experience at many different tiers of military command, and he had a strong understanding of the Roman economy, Rome’s provinces, its enemies and allies, its infrastructure, and its politics. While in 27 BCE, he set out to consolidate his own absolute power, he also put himself in a position to govern Rome with a singular and systematic approach that had not been possible during the more fractious centuries of the republic. A census taken in 28 BCE found 4,063,000 Romans registered as citizens. By 14 CE, at the end of Augustus’ astonishing four decade reign, that number had grown by almost a million.15

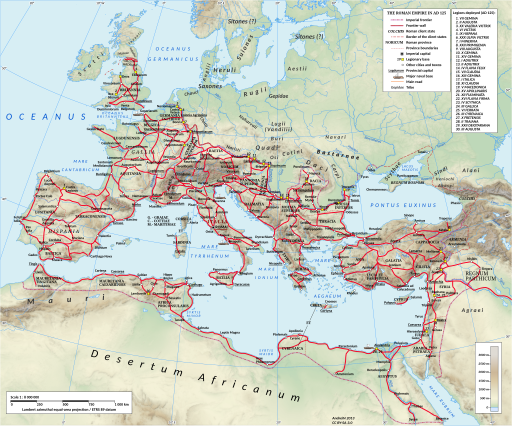

This map shows Rome’s road system under Hadrian (c. 125 CE), a road system that had been spurred along with great energy and success by Rome’s first emperor Augustus. Map by DS28.

Augustus, from the beginning, was not just thinking about roads – he was thinking about what lay at the ends of those roads – namely, provinces – some old and culturally Romanized, and others abutting quarrelsome and unfamiliar frontiers. In our shows on Cicero we learned about how provinces were governed during the late republic – former consuls or former praetors, at the end of their terms in office, headed out to a province to govern it for a year. There, they worked with tax farming corporations in order to extract money from the populace, sometimes acting in a sustainable and equitable fashion, and at other times wrecking provincial economies with dreadfully high taxes and interest rates. Augustus understood that this was a fundamentally unstable system, and that new policies were needed.

Immediately stripping the Roman senate of their lucrative right to post-office governorships would have been doing too much too fast, and so Augustus compromised. Ten provinces continued to be governed by former consuls who were in charge of taxes there. All the other provinces, however – thirteen by the end of Augustus’ reign, were ruled by what were called legates – or Legati Augusti pro praetori – envoys of Augustus acting as praetors. These provincial rulers were all accountable to Augustus himself. And because Augustus knew that tax collection was a complex and volatile process, in all of the provinces ruled by his legates, Augustus had a different set of officials superintend tax collection – officials from the equestrian order, initially recruited by him, and, like the legates, ultimately accountable to him.

The result of all these new and better maintained roads, way stations, and better provincial management was a more stable life for the millions of Romans who did not live in Italy. They were much less likely to be victimized by a greedy or financially desperate politician. If Augustus heard of chaos in one of his legates’ provinces, he now had politicians he could hold accountable. And unlike in the land grabs of 41 BCE, as his reign lengthened Augustus made it a practice to settle veterans abroad – in modern day Spain, France, Croatia, Albania, Greece, Turkey, Lebanon, Crete, Algeria, and Morocco, thus seasoning these areas, a number of them recent additions to the Roman empire, with strategically decentralized former soldiers.

Not all of Augustus’ reforms were quite so massively far reaching. Many had to do with the infrastructure of Rome itself. In addition to funding countless temples and other public buildings, the emperor superintended three groups of 500 men each who operated as a police force in the city. By 6 BCE, Augustus had created a fire department with seven groups that consisted of either 500 or 1,000 slave firemen, depending on where they worked. That same year saw the creation of an office called the praefectus annonae, or the food prefect specifically in charge of the flow of food into the city. Augustus also created offices designed to maintain the water infrastructure. Agrippa, who had been in charge of this, died in 12 BCE, and Augustus turned his responsibilities for pipes, aqueducts and fountains over to a trio of senators who were responsible to him.

Now, you might well know these bullet points of Augustan Age history – that, in a word, Rome’s first emperor surprised everyone by being less of a bloody tyrant and more of an energetic system-builder. His reign was hardly a peaceful one – expansionism often drove his foreign policy and led to a diverse set of conflicts with the Parthians in modern day Syria, the Marcomanni in Germany, and most famously the coalition led by Arminius responsible for the Teutoberg Forest massacre in 9 CE. But again, through much of Augustus’ reign, Rome found itself entering a period of unforeseen stability – one characterized by infrastructural improvements, an expanding economy, and a marked cessation of civil wars.

Augustus’ Marriage and Adultery Laws

In the Augustan Age poetry we’ve discussed so far – the work of Horace and Virgil – we have two poets who spent more of their lives under the republic than the empire. For Propertius and Ovid, the situation was the opposite, and I think that the weight of years these younger poets spent living in the splendor and security of Augustan Rome had a formative effect on the poetry that they wrote.

Augustus’ marital laws of 18 BCE affected the private lives of elite Romans in formative ways, and Propertius’ poetry suggests that these new regulations were not taken seriously by some. The painting is Amos Cassioli’s Das Venusopfer (c. 1875-8).

In addition to passing the adultery law in 18 BCE, Augustus passed another regulation – one that invaded the personal lives of Romans to a much greater extent. This second law was the Lex Iulia de maritandis ordinibus, a measure that required elite Romans to marry. Men between ages 25 and 60 were required to be married. So, too, were women between 20 and 50. If you were in these age groups, and you divorced, or your spouse died, you were required to remarry by law. Those who did not marry lost their rights to pass down inheritances – their money, upon death, went to the state treasury. The first version of this law even included a provision that prohibited unmarried people from visiting the theater and the circus.16

In addition to wanting elites to be secured in monogamous marriages, Augustus also wanted elite marriages to produce children. Any ambitious Roman man who wanted to ascend the cursus honorum would have a year cut off of the minimum age requirements for offices for each child he’d fathered. Similarly, women who had three kids of a certain age earned what was called the ius trium liberorum, or “right of three children,” which entitled her to certain legal rights that were otherwise unavailable.

We don’t know exactly what motivated Augustus to take these measures. Perhaps he recalled Caesar’s son with Cleopatra, a young man who, before Augustus had him killed, posed a serious threat to his credibility, and despised the thought of illegitimate offspring like the youth who’d once threatened his position. Maybe he simply wanted more stability at the aristocratic level, and a restoration of the upper class’ population. He seems, according to ancient sources, to have affected an appearance of plain living, his wife Livia and sister Octavia weaving clothing that he wore during public appearances.17 Whatever combination of strategy and personal temperament drove his laws on marriage and adultery, these laws were a source of contention for many Romans, including Propertius himself.

Propertius and the Augustan Regime

The most common subject in Propertius’ poetry is his love for a woman named Cynthia. We aren’t sure who she actually was. The later Roman writer Apuleius, in the mid 100s, wrote that “Propertius. . .speaks of Cynthia, but means Hostia,” although this isn’t particularly helpful.18 The most common theory is that she was a courtesan – as we’ll see later on, Propertius’ Cynthia is a glamorous woman, talented in speech and music and writing, untrammeled by marriage and free to spend evenings with whomever she wants and accrue gifts and artistic tributes as she goes along.19 Because she was likely a courtesan, and moreover because Propertius’ relationship with Cynthia was definitely not a monogamous marriage that produced offspring, this relationship would have been threatened by Augustus’ marriage legislation. And in his second book of poems, Propertius celebrates the failure of a law related to marriage – possibly the ones passed in 18 BCE, but more likely ones with which Augustus experimented a bit earlier on, in the mid-20s.20 Here’s Guy Lee’s translation of one of Propertius’ more famous and politically outspoken poems.Cynthia, how pleased you were when that law was withdrawn

Whose issue some time since caused both of us to weep

Long, lest it part us – though to separate two lovers

Not even Jove has power against their will.

‘And yet Caesar is great.’ Yes, Caesar is great in war.

But conquered nations mean nothing in love.

I’d sooner let this head be parted from my shoulders

Than lose love’s torches at a bride’s behest [in a conventional marriage]

Or as a bridegroom pass your closed door, looking back

At my betrayal with tear-filled eyes.

Ah, to what slumbers would my wedding-flute then play you,

Flute mournfuller than funeral trumpet!

Why should I breed sons for our country’s Triumphs?

From blood of mine shall come no soldier. . .

Cynthia, I love you only, may you love only me;

Such love is worth even more than fatherhood. (2.7.1-14,19-20)

On one level, it’s yet another love poem in which a speaker attests fidelity to a mistress. On another level, though, it is a statement of outright mockery toward Augustus. Augustus, Propertius attests, has no power to legislate who loves whom in Rome. Propertius emphasizes that Augustus will have no sons of his to serve in the legions on campaigns. The conventional, monogamous marriages so central to Augustus’ ideology, to Propertius, lack passion and vitality, and thus the emperor’s entire social program is clumsy and unwarranted.

The idea that Augustus’ military and legislative efforts are trivial alongside the great power of love surfaces elsewhere in Propertius’ poetry. Midway through Propertius’ second book, after a whole spectrum of love poems to Cynthia that run the range from hopeful to despairing, we find a poem that celebrates the consummation of their relationship. Near the end of this poem, Propertius writes that “To me this victory [in love] means more than Parthia conquered, / Than booty, captive kings, triumphal chariot” (2.14.23-4). It’s a simple couplet, and a politically pointed one. Augustus had been engaged in negotiations with Parthia throughout the 20s, and had recovered military standards lost by Crassus back in 53 BCE. This recovery took place in 20 BCE, and it was one of Augustus’ signal achievements early on. If you’ve seen the most famous statue of Augustus, the Augustus of Prima Porta, at the center of this statue’s breastplate is the Parthian king on the left returning a lost standard to a Roman on the right. The return of the lost standards was thus central to Augustus’ iconography and propaganda. And so when Propertius wrote that “To me this victory [in love] means more than Parthia conquered, / Than booty, captive kings, triumphal chariot,” he was rather clearly equating his own amorous enterprises with the emperor’s contemporaneous activities overseas.

So far, we’ve discussed the basics of the Augustan Age – that for the median Roman it must have been a bittersweet period in which the prosperity of the present was haunted by memories of the civil wars of the past. We’ve looked at just four of Propertius’ poems – two poems that refuse to forget the atrocities Augustus committed at Perusia, and two more that disparage Augustus’ efforts to control the private and familial lives of his subjects. These are famous poems within Propertius’ body of work, because they are some of our only surviving evidence of a culture of dissent that may have persisted in the Augustan Age’s artistic community over the course of the first emperor’s reign. But they are also idiosyncratic within the collection. Propertius, like Catullus, lived for love and literature far more than he did political activism, and I think we should turn to look at some of his more representative work. [music]

Propertius’ Love Elegies: The Basics

Love, to Propertius, is indeed a vast undertaking – one in which a participant experiences everything from jubilation to despair, and from confidence to jealousy. It is not uncommon in his poetry for him to attest that his love is as grand a thing as a Roman military expedition, or a Homeric epic – as grand a thing, or even grander. The opening lines of his second book of poems exemplify this idea – the idea that his love for Cynthia is his epic, and to me they’re some of the best lines in all Latin love poetry. Here’s the Guy Lee translation of some of Propertius 2.1.You [all] ask me how it is I write so often of love

And how my verses come soft on the tongue. . .

My only inspiration is a girl.

Suppose she steps out glittering in silks. . .

Suppose I spot an errant ringlet on her brow,

Praise of the lock makes her walk taller.

Suppose her ivory fingers strike a tune on the lyre,

I marvel at her hand’s deft pressure.

Or if she closes eyelids exigent for sleep

I have a thousand new ideas for poems.

Or if, stripped of her dress, she wrestles with me naked,

Why then we pile up lengthy Iliads.

Whatever she may do, whatever she can say,

A saga’s born, a big one, out of nothing. . .

The sailor talks of squalls, the ploughman of his oxen;

The soldier counts his wounds, the shepherd sheep:

But we engage in battles on a narrow bed.

We should all rub along in our own way. (2.1.1-16,39-46)

It’s a particularly lovely way of saying that Cynthia is the most important thing in his life, and that the smallest things she does, whether playing the lyre or closing her eyes for sleep, fill him with inspiration. To Propertius, the struggles of the Iliad were a mere story, and making love to Cynthia was a real, physical epic, every time.

Their relationship was hardly a smooth one, however. An earlier artistic manifesto that Propertius wrote – in his first book – also emphasizes that the poet isn’t interested in writing martial epics – not so much because Cynthia fills him with such joy and inspiration, as we saw in the previous poem, but because he is too consumed by pain and longing, and wants his poems to be useful to future people in similar situations. Here’s Propertius 1.7, in the H.E. Butler prose translation.

While [you sing, fellow poet,] of Cadmean Thebes, and the bitter warfare of fraternal strife, and – so may heaven smile on me, as I speak truth – [you] rival Homer for crown of song. . .I, as is my wont, still ply my loves, and seek for some device to o’ercome my mistress’ cruelty. I am constrained rather to serve my sorrow than my wit and to bemoan the hardship that my youth endures. This is my whole life passed: this is my glory: this the title to fame I claim for my song. Let my only praise be this, that I pleased the heart of a learned maid, and [often] endured her unjust threatening. Henceforth let neglected lovers read diligently my words, and let it profit them to learn what woes were mine. (1.7.1-14)21

Now, as we’ve learned, Augustus evidently asked all the Augustan Age poets whose works survive to write an epic about him. Propertius, Horace, and Ovid had to scramble to explain why they didn’t want to do so, and a standard Latin poetic trope called the recusatio, or recusal is common in their poetry. But Propertius’ explanations tend to be particularly self-assertive. Although Propertius certainly knows the Homeric and other epics well, and alludes to them often, at key moments he emphasizes that they are pompous fairytales next to the much more real and vital substance of his love for Cynthia.

The identity of Cynthia and the actual course of Propertius’ romantic life remain a mystery to us. Depictions like Auguste Vinchon’s Propertius and Cynthia at Tivoli invite us to picture a genuinely romantic relationship, but for all we know the poet’s addressee might be a wholesale fiction.

One of his poems calls his entire relationship with Cynthia “familiar bondage” (1.4.4). The equation of love to slavery is not an uncommon one in any generation of poets, and nor is the equation of love to madness and mania. The title of this episode, Episode 58, “She Caught Me with Her Eyes,” comes from the first poem in Propertius’ first book. Propertius writes that “Cynthia first, with her eyes, caught wretched me / Smitten before by no desires. . . And now for a whole year this mania has not left me, / Though I am forced to suffer adverse gods. . .And you, friends, who (too late) call back the fallen, / Seek remedies for a heart diseased” (1.1.1-2,7-8,25-6). Mania and a diseased heart are some of the darker elements of Propertius’ love poems, which occasionally become almost masochistic. “Love,” write Propertius late in his second book, “[is] not worn away by an accusing mistress; / Love stays and puts up with her unjust threats. / When scorned he asks again. Though wronged he takes the blame, / And back he comes, if on reluctant feet” (2.25.17-20). These lines paint a bleak picture of the poem’s speaker, a figure who will put up with abuses and return, time after time, to his abuser.

While we might think these elements in Propertius’ poetry are so commonplace as to not warrant consideration, I think we should remember how early Propertius came along. If you’ve read the European love poetry that begins with Petrarch and runs up to the eighteenth century, or before that, the medieval courtly love tales of Marie de France, Chretien de Troyes, Thomas Malory, and the early Dante, then the image of an aristocratic lover with tearstained sleeves seems trite and unmemorable. A Lancelot, or a Petrarch, or a Philip Sidney resigns himself to the self-imposed tragedy of unrequited love and gushes forth with prattle magnifying his lover’s slightest gestures, and some of it is beautiful, some rather pathetic, and most of it amply precedented in poetic tradition. What makes Propertius’ love poetry interesting, though, is that may have occurred near the outset of this tradition.

One of Propertius’ sources of contention with Cynthia stems from his cynicism about money. In a poem unrelated to his mistress, he writes that in Rome, “Gold drives out honesty, justice is sold for gold. . .Proud Rome is rotten with her own prosperity” (3.15,60). Cynthia is a part of this process of degeneration. Propertius writes that “Cynthia’s not one to follow rank or care for honours; / She always weighs up a lover’s purse” (2.16.11-12). In other words, Cynthia cares about money, not ancestry nor office. Later in the same poem, Propertius voices the following wish: “If only there were no rich men in Rome, and even / Our leader lived in a reed hut! / No girl-friend then would ever sell herself for gifts / But grow old with one lover” (2.16.21-2).

To me, these are especially interesting lines. Propertius is combining two very different strands of Roman thought here – first the short love lyric that Catullus had brought in from Sappho, but secondly also the much more distinctly Roman rural conservativism that began a century and a half earlier with the work of Cato the Elder. Put simply, Propertius wonders whether if he’d lived in an earlier, earthier period of Roman history, and not one so infected with avarice and excess, his mistress would love him. In an odd way, although he made fun of Augustus’ family values, Propertius occasionally shares elements of the emperor’s conservativism. In his fourth book of poems Propertius imagines Rome’s simple past and its homegrown religious traditions, writing that “No one then was keen to seek out foreign Gods / When the awe-struck crowd hung on their fathers’ ritual” (4.1.17-18).22 During such times, the poet implies, men and women trusted one another, and were more loyal to one another, than in the decadent present. In the real Rome that Propertius inhabited, however, mistresses were covetous and venal. A poem in Propertius’ second collection describes Cynthia’s appetite for finery, and how it’s bringing the poet to ruination.

Sometimes she wants a fan made of proud peacock’s feathers

And a cool crystal ball to hold in her hands

And sometimes wants me to bid for ivory dice

Or some flashy gift from the Via Sacra.

Oh I’m hanged if I grudge the expense, but now I’m ashamed

To be the butt of a deceitful mistress! (2.24A.11-16)

These lines are an interesting twist on the conventional trope of the unrequited lover that dated at least back to Catullus. Propertius’ frustrations are not just with Cynthia. They are also with the decadent civilization that made a person like Cynthia possible. She is not, in his poetry, merely an independent agent acting on her own whims, but instead a creature of her environment – an environment that encourages her greed and capriciousness. And this greed may have been something that manifested itself in the time that Propertius knew her. In an earlier poem, Propertius promises, “[W]hile I’m alive, you’ll always be most dear – / So long as you’ve no taste for wretched finery” (1.2.31-2). She may have developed this taste, however, and it may have been one of the things that definitively came between them.

Alright. We’ve seen how Propertius’ complaints against Cynthia are occasionally intermingled with castigations of contemporary Roman life. These are some of the more distinct elements of his love poetry, and there are others. In contrast to his predecessor Catullus, Propertius offers us a lot of details on Cynthia – what she looked like, her personality, her hobbies, and even what sex with her was like. Catullus was certainly not shy about the nitty gritty of sex and anatomy, and yet the earlier poet’s lover Lesbia is a much less distinct, and less physical presence than Propertius’ Cynthia. Let’s look at some moments in Propertius’ poetry when he gets specific about his lover, what he adored about her, and the carnal aspects of their relationship. [music]

Propertius’ Complex Relationship with Cynthia

Propertius’ Cynthia is no ghostly, silent, ephemeral mistress. He describes her as having “red-gold hair, long hands, big build – she moves like / Juno, fit sibling for Jove himself” (2.2.5-6). He recollects specific sexual experiences he had with her, reminiscing, “What talk we had by lamplight! / What battles in the dark! / Breasts naked, she would wrestle with me – then / Stall by covering up” (2.15.1-6). The poem takes a dark turn a moment later, Propertius adding that “If you insist on going to bed clothed / I shall use force and tear your dress. / Indeed, if anger pushes me beyond the limit, / You’ll have bruised arms to show your mother” (2.15.17-20). Whether these lines are describing rough sounding, but consensual foreplay, or something far worse, we have no way to tell – but the point here is that Propertius gets more detailed about Cynthia’s physicality than Catullus ever does about Lesbia’s. Propertius also gets more detailed about Cynthia’s personality, too.Cynthia, also, was evidently a poet, and also a musician and a delightful conversationalist. In his first book of poems Propertius tells Cynthia that “Phoebus gladly grants you his poetry / And Calliope her Aonian lyre, / And your delightful talk discloses unique grace” (1.2.27-9). Early in their relationship, evidently, she cared more for literature than for finery – Propertius remembers how “I could not move her with gold or mother of pearl, / But only with devoted verse” (1.8B.39-40). Reading the first two books of Propertius’ poems, we find tendrils of a connected story – a poet, in his twenties, meets a mesmerizing, educated woman, perhaps a courtesan, perhaps a freewheeling aristocrat. They share genuine interests – music, and literature, and they find one another’s conversation rich and stimulating. Perhaps, for a time, their relationship was monogamous and consummated. However, Cynthia became interested in other men, and – according to the poems, at least – began to enjoy the material acquisitions she could acquire through her lovers. Hundreds of the lines that Propertius left behind show the poet coping with what he perceived to be Cynthia’s refusal to love him exclusively.

The absolute darkest of these lines occur in the eighth poem in Propertius’ second book, in which he threatens her with murder. “[Y]ou shall not escape,” Propertius threatens. “[Y]ou have to die with me. / The blood of both shall drip from this same blade. / Though such a death for me will be dishonourable, / I’ll die dishonoured to make sure you die” (2.8.25-8). This is a ugly quartet, and generally the poet is far milder in coping with Cynthia’s rejections, either steeling himself to stay strong or remain loyal, or, in other instances, actually shrugging her off and urging her to do what she needs to do. In fact, let’s look at a couple of what we might call Propertius’ coping poems – poems in which he consoles himself about the unavailability of his lover.

One of these is thoroughly conventional – something that might show up in hundreds of years of medieval courtly love poetry or renaissance sonnets. Propertius writes,

I am used to bear timidly all your decrees,

Not to lamenting shrilly at what you do,

And in return am given sacred springs, cold cliffs,

Hard resting on rough paths;

And every tale of woe I have to utter

Must be told in solitude to shrill birds.

Yet, be as you will, the woods for me shall echo Cynthia

And the lonely rocks repeat your name. (1.18.25-32)

A lover, sitting solitary in the forest and bemoaning his mistress’ absence might appear in Chrétien de Troyes’ Lancelot, Edmund Spenser’s Amoretti, or the notebook of the high school sophomore who lives down the street from you. It was certainly not so hackneyed an image in Propertius’ time, and Propertius tried to cope in his poetry through different means, as well.

There is an element of wry humor in some of Propertius’ coping poems, as though he realizes, to some extent, the futility of pursuing someone who cannot be won over. “[H]owever badly you treat me, traitress,” he writes in his first book of poems, “[N]ever, my life, shall other women tempt me / To end my just complaining at your door” (1.8A.17,21-2). Along the same lines, a famous couplet from this same book proclaims, “My fate is neither to love another nor break with her: / Cynthia was first and Cynthia shall be last” (1.12.19-20). These lines, like the image of the poet in the forest, are conventional, avowing loyalty at all costs. In another poem Propertius writes that Cynthia nearly ignored him when he was dreadfully ill, and only came to visit him belatedly – but that he forgives her for it (1.15.29-32). While Propertius wrote plenty of poems about remaining faithful to a faithless mistress, he wrote other poems that indicate that he realized what was going on between them was a sort of game, and no real matter of life and death.

After reading so many descriptions of his steadfast faithfulness, we are surprised when we reach the 22nd poem in his second book, in which Propertius tells us that really he always operates by having two lovers at once – one might spurn him but the other will dally with him one week, and then the opposite the next. Two poems later, Propertius says that neither Roman aristocrats nor courtesans are very ideal lovers – the best are prostitutes, who can be dealt with directly, and immediately, and with fewer complications. And in the next poem, Propertius echoes his sentiment about his penchant for prostitutes. “[I]t’s no wonder,” he writes, “that I’m looking for cheap girls: / They cause less scandal. Surely a sound reason” (2.24A.5-10). Toward the end of his second book, just as Propertius has admitted he’s not so faithful to Cynthia after all, he tells his lover he doesn’t expect her loyalty either. He references the myths of Pasiphae, who slept with a bull to produce the minotaur, and Danae, who was seduced by Zeus and then gave birth to the hero Perseus, and says that if Cynthia wants to sleep around a bit, it’s fine by him.

Great Minos’ wife, they say, was long ago seduced By the beauty of a wild white bull. Danaë too, though shut in by a wall of brass, Couldn’t be chaste and say No to great Jove. So, if you’ve done the same as Grecian girls and Latin, My verdict is Long life to you – and freedom! (2.32.57-61)

These are surprising sentiments to find in a book of love poems. In a number of other places in Propertius’ body of works he admits to jealousy and insecurity (2.9.1-2, 2.9.30-5, 2.16.21-2), but halfway through his poetic career, he could look back and confess that he wasn’t actually crying in the wilderness all the time, and that neither he nor Cynthia had even come close to being loyal to one another, and that female sexual misadventures had been normal since time immemorial.

The poem that wishes Cynthia good luck in her future trysts, however, isn’t the end of the story. As Propertius became older, and as, we presume, he ultimately failed to gain Cynthia’s loyalty, as he wrote his third and fourth books of poetry, his poems about her return to bitter retrospection. But they also become more artistically self-conscious. Let me explain, because I think this is fascinating.

There is an implicit narcissism in a great deal of love poetry – even supposedly self-debasing love poetry. Shakespeare’s most famous sonnet begins with the lines, “Shall I compare thee to a summer’s day? / Thou art more lovely and more temperate” (18.1-2). While the poem seems to be a promise of love to an addressee, it is really about Shakespeare himself, through and through. The sonnet ends with the lines,

[T]hy eternal summer shall not fade Nor lose possession of that fair thou ow’st; Nor shall Death brag thou wander’st in his shade, When in eternal lines to time thou grow’st; So long as men can breathe or eyes can see, So long lives this, and this gives life to thee. (18.9-14)

The “this” in the final line references Shakespeare’s poem itself, and so the main statement of the sonnet is that the addressee will be beautiful for all time, but only thanks to the poet’s unparalleled ability, an ability so extraordinary that it can bestow immortality. Ovid felt the same way about his addressee, Corinna, who may have not even been a real person – Ovid tells his mistress in the Amores, published around 20 BCE, “Rich cloaks will shred, and gems and gold will all decay, / But in these lines you’ll never fade away” (Am 1.10.61-2).23 Love poetry, then, is often backhanded self-aggrandizement. However debased and abject we may find the speakers in the poems of Catullus, Propertius, Petrarch, Sidney, Shakespeare and others, these writers were ambitious craftsmen seeking to secure their own legacies in the unfolding tradition of European love poetry. And similarly, many of the poems that Propertius wrote to Cynthia are, when given more than a precursory reading, more about Propertius than they are about Cynthia.

For instance, the poet promises Cynthia that her “beauty shall be made world-famous by my books” (2.25.3), nearly an identical statement to the one Shakespeare makes at the end of his most famous sonnet. Along the same lines, in his third book Propertius declares that “[A]ge will not destroy the name achieved by talent; / Talent’s glory stands – immortal” (3.2.25-6). According to Propertius, then, Cynthia’s path to immortality lies through Propertius’ pen. Most explicitly of all, the last poem in Propertius’ second book indicates that whatever Propertius actually made of his fraught relationship with Cynthia in the real world, he was confident that his poems about Cynthia would install him amidst other Latin love poets, poets like Catullus, who had written of Lesbia, Calvus, who had written of Quintilia, and Gallus, who had written of a woman named Lycoris. Thinking back on this growing tradition of love poetry, Propertius writes, in the H.E. Butler translation,

Such are the [poems] that. . . Catullus wrote, whose Lesbia is better known than Helen. Such passion also the pages of learned Calvus did confess, when he sang of the death of hapless Quintilia; and dead Gallus too, that of late laved in the streams of Hell the many wounds dealt him by fair Lycoris. Nay, Cynthia also has been glorified by Propertius – if Fame shall grant me a place mid such as they. (2.34.87-94)24

At this and other moments, Propertius seems to be more interested in his own poems about Cynthia than Cynthia herself. And in fact, Propertius’ third and fourth books are filled with an increasing degree of artistic self-consciousness. I want to finish our introduction to Propertius’ poetry by looking at some of his later work – work that demonstrates that as the 20s gave way to the 10s BCE, and Augustus increasingly dominated all aspects of Roman life, Propertius bore deeper and deeper into ancient literary history, moving away from love altogether. [music]

Propertius and Callimachus

An important figure lurks behind Latin poetry of the first century BCE. We’ve talked about him before, but it’s been a while. In the third century BCE, in the city of Alexandria, in the same place and time that Jews were translating the Hebrew Bible into the Greek Septuagint and Apollonius of Rhodes was writing Jason and the Argonauts, an influential Greek poet named Callimachus was making a name for himself, as well. Callimachus lived two centuries before Catullus, Horace, Virgil, Propertius, and Ovid, but he influenced all of them. And he influenced them, specifically, to write short, dense, heavily allusive poetry, and not – as had been the main tradition – sprawling narrative epics like the Iliad and Odyssey.While most of Callimachus’ work has been lost, in the first century BCE his lines were all over Rome, and he influenced multiple generations to eschew long works and instead write compressed, complicated short poetry. Latin poetry of this period, then, even when you read it in an English translation, often still feels like it’s in a foreign language. Let me give you an example, from Propertius – a love poem so embroidered with allusions that it is incoherent to almost any modern reader.

As the girl from Knossos, while Theseus’ keel receded,

Lay limp on a deserted beach,

And as the Cephéan Andromeda in first sleep rested,

From hard rocks freed at last,

And as a Maenad, no less tired by the ceaseless dance,

Swoons on grassy Apídanus,

So Cynthia seemed to me to breathe soft peace,

Leaning her head on relaxed hands. (1.3.1-8)

If you don’t share Propertius’ cultural and literary heritage, or are otherwise inexperienced with Greco-Roman literature, the triple simile here is impenetrable.25 To Callimachus, this was not at all a bad thing. The earlier Greek writer wrote “I hate the cyclic poem, nor do I take pleasure in the road which carries many to and fro. . .I drink not from every well; I loathe all common things.”26 Callimachus favored a short, dense style of poetry, one that Romans of the late republic and Augustan Age found enchanting.

By the time Propertius sat down to write his fourth book of poems, he had begun to call himself the Roman Callimachus. The opening poem of this fourth book, referencing Propertius’ home region of Umbria, announces, “Umbria, birthplace of Rome’s Callimachus! / Whoever sees her hilltops climbing from the valleys / Should rate those ramparts by my genius” (4.1.64-6).27 From attesting that he would make Cynthia live forever in his second book of poems, in Propertius’ third and fourth books of poems he begins to appear buoyantly confident that literary immortality is already his. “[W]hat the envious crowd withholds from me in life,” he writes in the first poem of his third book, “Honour will pay me after death at double interest. / Everything after death is magnified by age: / A name beyond the grave sounds greater in the mouth” (3.1.21-4). And in the very next poem, Propertius makes perhaps the most arrogant claim of all:

Orpheus, they say, bewitched wild animals and held

Back rushing rivers with his Thracian lyre. . .

What wonder, by the grace of Bacchus and Apollo,

If girls in plenty worship my words?

Lucky the girl who is celebrated in my book;

Each song will be a reminder of her beauty. (3.2.1-2,9-10,17-18)

Bidding modesty a decisive farewell, Propertius compares himself to a god and emphasizes, as Shakespeare later would, that his poetry is a path to immortality to any woman fortunate enough to make an appearance in it. Increasingly, then, as Propertius advanced from his twenties to his thirties, the chief subject of his love poems became not Cynthia, but himself.

Catullus, Horace, Virgil, and Propertius are still, largely, biographical mysteries, and most of what we know about them can only be tentatively extrapolated from their poems. Catullus appears an impetuous and erratic libertine; Horace, a more modest craftsman, fond of easy living; Virgil, bashful and enigmatic. Propertius never had Catullus’ venom, but, particularly later in his career, he shunned Horace’s humbleness and Virgil’s reticence and began to trumpet his poetic ideals and vocation with great confidence. We know almost nothing about his later years or how he died – only that a line Ovid published in 1 BCE indicates that Propertius had passed away by that time.

Propertius’ legacy was a complicated one, intertwined with the legacies of his contemporaries. A quartet of lines discovered in the graffiti of Pompeii is a fusion of both Ovid and then Propertius, the first two lines from Ovid’s Amores and the second two from Propertius’ fourth book.28 In total, the graffiti reads,

Let your portal be deaf to prayers, but wide to the giver;

let the lover you welcome overhear the words of the one you have sped.29

The doorman must wake for givers; when the empty-handed knock

Let him dream on, deaf, with the bolt shot to.30

This fusion of Ovid and Propertius, cut into a wall at Pompeii some time in the first century of CE and preserved by the eruption of Vesuvius in 79, shows how the sentiments of Augustan love poetry were circulating in the Roman world a century after it was written. The Latin word for love, amor, is the inverse of the Latin word for Rome, roma, and as Virgil cemented the emperor’s lineage to Aeneas and Venus, he played with this pun in the Aeneid. The statue of Augustus I mentioned earlier, the Augustus of Prima Porta, does bear an image of the Parthian standards being returned, a martial image central to the first emperor’s iconography. But this same statue also features a small secondary figure, Cupid, beside the emperor’s right knee. Aeneas, and long after him Augustus, were the sons of Venus, and roma came from amor, and in the age of Propertius and afterward, love poetry slowly became engraved in the Roman imagination. [music]

Social and Literary Change in the First Century BCE

In a poem that Propertius probably wrote in the late 20s BCE, he mused on old age. The poem attests that there are many things that he still wants to learn, and that in his old age, he hoped to study things in the natural world – rainbows, the sun, the sea, and how the seasons change. The poem ends with the lines, “For me life’s outcome shall be this, but you to whom / Wars are more welcome, bring Crassus’ standards home. (3.5.47-8). We’ve heard this idea before from him – this notion that ambitious men can fight out their campaigns and seek their glory, but his horizons are smaller. Earlier, it was Cynthia who formed the horizon of Propertius’ hopes and dreams, but, as the poet approached his 30th birthday, knowledge became an end unto itself.

Propertius writes near the beginning of a tradition that would later lead to writers like Philip Sidney (1554-1586), the great English poet whose sonnet sequence would chronicle his own roller coaster ride of romantic experiences.

We began our foray into Greco-Roman literature with Hesiod and Homer, poets who lived during a time when oral tradition was the main way literature travelled between generations. By the age of Plautus, a culture of publicly performed literature was still alive and well on the Roman stage. By the time of Propertius, this period of literary history was closing its gates. Propertius’ idol Callimachus, two hundred years earlier, had worked in the Library of Alexandria, cataloging and indexing the institution’s thousands and thousands of scrolls. And the erudition of writers like Callimachus, and Virgil, and Propertius would not have been possible without access to printed texts. Rome had its libraries and bookstalls by the Augustan Age, and the period’s most famous writers used them. The thousands of proper nouns that pepper the pages of Catullus, Virgil, Propertius, and others are evidence of a burgeoning print culture that valued broad learning and bookish allusions.

It’s curious that while literature moved to being an elite domain over the course of the first century BCE, other artistic trades remained the work of anonymous craftsmen. We know the name of Augustus, of course, and the Augustus of Prima Porta remains the quintessential image of Rome’s first emperor. But as to who carved this masterpiece, we don’t know. Thus, as Propertius and his contemporaries climbed the steps of new public temples and libraries, as they recited their poems to one another and gazed up at the crown molding and intricate designs on the ceilings of Roman bathhouses, they were content to let the names of an army of sculptors, engravers, and painters fall by the wayside. This isn’t even to mention dancers, actors, and musicians, of course, an underclass of anonymous servants who never had respectable reputations in Roman history.

Many ancient Roman sources attest to the grandeur and intelligence of Augustus. A much smaller set, though, and Propertius is among them, recorded dissatisfaction and even derision toward some of the emperor’s legislative efforts.

One solid answer that we have evidence for is that Catullus proved such an original writer, and an effective champion of Sappho that he brought her ideas into the Roman world, where they proliferated after his death in about 54 BCE. This isn’t impossible, but let me propose an addition to it. Propertius’ generation, literarily speaking, were in a curiously contradictory situation. All of them knew Homer. Most of them knew Apollonius. They knew lost epics from Archaic Greece which had once wreathed the Iliad and Odyssey. They knew the Roman epics of Naevius and Ennius. They would have encountered Livius Andronicus’ Latin translation of the Odyssey. A gigantic portion of their literary diet was epics. And yet Callimachus, and later Catullus, taught Propertius and his generation that epics were outdated. One response to this conundrum was Virgil’s – to write an epic in an almost Callimachean style, so dense with allusions, so littered with a scrollwork of puns and wordplay, that it is a sort of fusion of all the contrary literary styles popular during the Augustan Age. Another response, however, was that of Propertius, Tibullus, and Ovid, and that was to write autobiographical love poetry covered over with a wicker of erudition, so that a single declaration of affection to a mistress might carry with it a thousand years of literary history.

But there’s another, far simpler reason why Propertius and his contemporaries may have turned to love poetry, and that was that romantic pursuits were a reliably engrossing pastime in an increasingly totalitarian Rome. A generation or to earlier, Cicero could still break through the glass ceiling of his equestrian status and climb the social ladder to become consul. But in Augustan Rome, one person could terminate a public career at any time, at the slightest provocation. By the time he became emperor, Augustus was no sadist, like Caligula would soon turn out to be, nor even a testy authoritarian, like Domitian. He was, however, ultimately in charge, and this must have radically changed the potential career options of energetic and ambitious Romans. Beneath his rapidly evolving regime, a small group of poets found autobiographical love poems a worthy vehicle for their literary creativity. Romantic relationships, to Propertius’ generation, could be a welcome distraction to civic powerlessness, and writing about them, doubly so. Propertius died in the same decade that Jesus Christ was born, in an evolving Mediterranean world where the once rousing public life of the city state had been smashed by the birth of the intercontinental empire – first Alexander’s Macedonian balloon, and then the Diadochi kingdoms, and then the Roman republic and empire. Propertius’ contemporaries may have had generational memories the pluralistic era of the city state, where public participation in government and religious ritual were a cornerstone of each citizen’s life. After Alexander, and then Augustus, however, vast, centrally controlled empires made the lives of citizens into ball bearings in a giant machine, and perhaps no one in history did more to effectively centralize a state than Rome’s first emperor.

And so when we see a Propertius, or an Ovid, turning to write love poetry, we can understand this literary evolution in part as a response to the empire’s rapid and dizzying consolidation. Propertius had no clear path to being a statesman. His poems show that he was still haunted by the atrocities Augustus had committed against his countrymen. And yet in the small and sparkling empire of Propertius’ courtship, and the poetry that he wrote about it, he had a chance to find happiness and perhaps make a name that would last beyond his own time. No wonder, then, in the opening of his third book of poems, as he saw the Augustan regime hardening and expanding all around him, he wrote, “[W]hat the envious crowd withholds from me in life, / Honour will pay me after death at double interest.” Posthumous deliverance was the main attraction of the Hellenistic cult religions, and Propertius, like his contemporaries, sought it through his poetry. [music]

Moving on to Ovid

Any public reading or salon gathering in Rome in 23 BCE might have been attended by some particularly illustrious writers. Visitors might have met self-effacing and amicable Horace, then writing his odes and epistles and slowly becoming Augustus’ go-to source for short poetry. Attendees might have met the more reserved and by this time renowned Virgil, who was known to be writing an epic to rival the Iliad. They might have met Propertius, who was gaining a name for himself, or his slightly older contemporary, Tibullus, also an accomplished love elegist. Attendees to a Roman salon in 23 BCE might have encountered any number of ancient Roman writers whose works have been lost, in these strange opening years of the Augustan regime, the new and ominous serenity of the first principate, as brick changed into marble.

The poetry of the Augustan Age suggests an elite world of private readings and literary gatherings – events geared to set poets and patrons up with one another and allow both classes opportunities for various recreational social relationships, as well. The painting is Stepan Bakalovich’s At Maecenas’ Reception (1890).

Ovid mastered, subverted, and destroyed the genre of Latin love elegy in the first phase of his career. No sentimentalist, Ovid next produced the Art of Love, an unapologetic manual on seduction, and tongue-in-cheek companion pieces about women’s cosmetics, and how to recover from heartbreak. While at work on this body of subversive love poetry, Ovid was also writing the Heroides, a series of generally tragic love letters that show – even for an Augustan Age poet – an advanced level of erudition, erudition which would blossom fully in the Metamorphoses, which the poet wrote in his forties. Excepting the Hebrew Bible and New Testament, the Metamorphoses, a 12,000-line behemoth containing over 250 stories, was the most influential text from antiquity on the European Renaissance, a spellbinding and titillating portal to the ancient pagan past. And while writing the Metamorphoses, itself a sort of pan-Mediterranean bible of the region’s entire literary history, Ovid also wrote a more distinctly Roman poem called the Fasti, a history of Rome’s sacred traditions. Late in his life, in 8 CE, Ovid was banished to Tomis, in modern day Romania, a site so far removed from the imperial capital that the poet felt like he’d been relegated to death. Even in exile, though, he continued to write – he produced a book of poems lamenting his exile, another volume of letters to acquaintances back home, and a curse poem execrating an unknown addressee for offenses against him. In addition to all of this work that survives, Ovid also wrote a lost tragedy about Medea, that breathtaking heroine with whom nearly every Greco-Roman author, at some point or another, had to engage.

We will have six episodes devoted to Ovid, covering most of the works that he wrote in their entirety. And next time, we will begin with Episode 59: Early Ovid, on Ovid’s Amores and Heroides. In the literary salons of Augustan Rome, love elegists, like Propertius, were all the rage. And love poetry was a logical entry poet for a young poet into the world of Roman letters, being short and manageable, in addition to having the practical side effect of potentially attracting sexual partners. Ovid, who was only sixteen years old when Augustus declared himself princeps, threw himself into the genre with gusto, but from the beginning, Ovidian love poetry is bemusedly ironic. Where Propertius and Catullus are passionate in their ardor, Ovid is tactical; where his predecessors are heartbroken and angry, Ovid is nonchalant and unimpaired. And because Ovid led a long life, and left behind such a broad and diverse corpus of poetry, throughout the love lyrics that make up the Amores and the lovelorn soliloquies that make up the Heroides, we get the sense that Ovid is not only uncommitted to any of his addresses, but that he’s also not even committed to the genre of love poetry at all. So next time, get ready to hear the story of Ovid’s life, and learn about the fun, racy, exquisite short poetry he wrote at the beginning of his career.

Quick note here. I’ll be giving a talk at Harvard in early November – about a month from this episode’s release date. The talk will be part of a conference and festival called Sound Education, an event that’s all about educational podcasting and educational radio. Basically, a lot of geeks with microphones are getting together to share our love for teaching through audio and trying to create better partnerships and pathways between radio, academia, and DIY podcasters like me. If you listen to my show, it’s not unlikely that you know the work of Dan Carlin, who will deliver the keynote address at the festival, and also Kevin Stroud of The History of English, Patrick Wyman of Tides of History, and a whole host of people from Radiolab, Radiotopia, PRX, and NPR who help host or produce educational programs. Check out the conference’s website at soundeducation.fm – there are dozens of us independent podcasters who will be there participating in some capacity. The main date to remember is Saturday, November 3, 2018 – if you’re in New England it might be a nice time for a trip down to Boston. Also, the prior day – that’s Friday, November 2, there’s a slightly different event geared toward not the listening public, but instead educational audio producers themselves. If you’re interested in getting into educational podcasting or radio, or you’re already involved, Friday’s event is a series of around twenty panels where you can hear some top folks in the industry talking about their craft and fielding questions from the audience. I’ll be moderating some panels that day, including one on classics. So the site again is soundeducation.fm – check out the site, see if you’re interested, and I’d love to meet more of you in person.

I have a quiz on Propertius and the Augustan Age at literatureandhistory.com if you’re interested. Thanks for listening to Literature and History. If you want to hear a song, I’ve got one coming up. If not, Ovid and I will see you next time.

Still listening? Well, for this episode’s comedy song, I was thinking about that oddly narcissistic side of love poetry that came up in this program. I got to thinking about all those generations of love poets who believed they could both woo a mistress and simultaneously secure literary immortality for themselves – I mean it seems like such a silly combination of self-abasing flattery on one hand and egotistical grandstanding on the other. I’ve written some love songs in my day, but they’ve never included the added provision that they’ll make the addressee live forever. Until this one. This one’s an emo or alt rock tune called “Arrogant Love Song,” and it rather overtly attempts that combination of flattery and self-aggrandizement that we see in Propertius, Ovid, and Shakespearean sonnets. I appreciate you staying on to listen to these, and next time we’ll begin our journey through the works of Ovid.

References

2.^ A description of his home in 4.1.121-34 leads Guy Lee to conclude the poet’s home was near modern day Bevagna. See Lee (1994) p. 185.

3.^ Propertius. The Poems. Oxford: Oxford World’s Classics, 1994, p. 106. Further quotes from Propertius’ poetry come from this text, unless otherwise noted.

4.^ Horace. Satires and Epistles. Translated by John Davie. Oxford: Oxford World’s Classics, 2011, p. 98.

5.^ The previous episode of this podcast talks about the reception history of the second half of the Aeneid, and the Harvard School of interpretation to the poem.

6.^ Lyne, Oliver. “Introduction.” Printed in Propertius. The Poems. Translated with Notes by Guy Lee, with an Introduction by Oliver Lyne. OUP, 1994, p. ix.

7.^ Fulvia’s role in the war, and her sway over the senate is famously recorded in Cassius Dio’s Roman History 48.4.1-6.

8.^ For the geography see n. 2, above.

9.^ See Eck, Warner. The Age of Augustus. Blackwell Publishing, 2007. Kindle Edition, Location 242.

10.^ The sacrifice Aeneas makes of eight captives to Pallas (Aen 10.517-20) may reference this event, though Virgil may simply be following Il 23.190-3.

11.^ See Lee (1994), p. 140.

12.^ The impact of wars on marriages continued to be an interest to the poet up to his final book – 4.3 is a wife’s doleful letter to her soldier husband.

13.^ Propertius. Propertius. Translated by H.E. Butler. New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1917, p. 59. Hard brackets indicate places where I’ve done away with the King James English.

14.^ See Eck (2007), locations 620-3.

15.^ See Eck (2007), Location 1030.

17.^ See Wood, Susan E. Imperial Women: A Study in Public Images, 40 BC-AD 68. Brill Academic Publishing, 2000, p. 77 and Suetonius Augustus 17.

18.^ Apuleius. Delphi Complete Works of Apuleius with the Golden Ass. Delphi Classics. 2015. Kindle Edition, location 11948.

19.^ Her social status is debatable. 1.16 implies that she came from distinguished stock.

20.^ The chronology is a bit puzzling. Guy Lee writes that the opening three lines of the poem “are the only evidence for the law in question” (145). If Propertius’ second book of poems was released in 25 BCE, then it predated the marriage laws of 18 BCE by at least seven years.

21.^ Propertius. Propertius. Translated by H.E. Butler. New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1917, p. 19. Hard brackets indicate places where I’ve done away with the King James English.

22.^ More evidence of this conservatism can be found in (2.6.27-30).

23.^ Ovid. Ovid’s Erotic Poems: Amores and Ars Amatoria. Translated by Len Krisak, with an Introduction and Notes by Sarah Ruden. University of Pennsylvania Press, 2014, p. 44. See also Am 1.15.7-8.

24.^ Propertius. Propertius. Translated by H.E. Butler. New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1917, p. 173.

25.^ It’s also not very good poetry. Ariadne had been abandoned by Theseus and in the myths, either died or was swept up by Dionysus, and so it’s a mystery to me why Propertius would choose to compare the peaceful Cynthia to the stricken Ariadne in her most awful moment.

26.^ Callimachus and Lycophron. Translated by A.W. Mair. London: William Heinemann. New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1921, p. 157.

27.^ Similarly, see (3.1.1-4).

28.^ Specifically Am 1.8.77-8 and Propertius 4.5.47-8. See Milnor, Kristina. Graffiti and the Literary Landscape in Roman Pompeii. OUP, 2014, p. 152.

29.^ Ovid. Am 1.8.77-8. Printed in Heroides and Amores. Translated by Grant Showerman. New York: Macmillan, 1914, p. 353.

30.^ Prop 4.5.47-8. Quoted in Lee (1994), p. 115.

31.^ White, Peter. “Poets in the New Milieu: Realigning.” Printed in Galinsky, Karl, ed. The Cambridge Companion to the Age of Augustus. Cambridge University Press, 2005. Kindle Edition, Location 5885.