Episode 59: Early Ovid

The love poetry of Ovid (43 BCE-17 CE) was standard Latin curriculum for hundreds of years, but it was also the product of a very specific historical moment.

| Read Transcription | References and Notes |

| Episode Quiz | Episode Song |

| Episode on Spotify | Episode on Apple Podcasts |

| Previous Show | Next Show |

Ovid’s Amores and Heroides

Hello, and welcome to Literature and History. Episode 59: Early Ovid. This is the first of five programs on the Roman poet Publius Ovidius Naso, who lived from 43 BCE until 17 CE, and whose most famous work is the Metamorphoses. In this show, we’re going to learn about Ovid’s early works – the Amores and the Heroides.

Etorre Ferrari’s statue of Ovid in Constanța (1887) shows that eastern Romania takes pride in the Roman poet’s residence there, long after he wrote the Amores and Heroides, notwithstanding Ovid’s disparagement of Tomis throughout the Tristia and Letters from the Black Sea. Photo by Romeo Tabus.

For ten episodes, now, we’ve been exploring this literature, with Catullus forming a prelude, Horace and Virgil serving up an expansive main course of odes, satires, epistles, pastoral poetry, didactic poetry, and epic, and the love elegists Propertius and Tibullus offering multiple collections of diverse short works, often on the theme of love, but ranging widely to other subjects, as well. Literature was burning brightly in Rome during the careers of these writers, and evolving quickly as they studied one another’s works alongside a huge catalog of earlier Latin and Greek authors.

In some ways, Ovid was at a disadvantage. He was a child while Virgil and Horace were making names for themselves in the 30s, and a teenager when Virgil was writing the Aeneid. By the time Ovid reached his mid-20s, accomplished love poets had already mastered the elegy, Virgil had completed Rome’s great epic, and Horace had shown that he could write a huge range of poetry, from grave and serious odes, to rambling and kooky satires. Ovid thus arrived late to the variety show, after some absolutely dominating performers had already taken the stage. But like many of literature’s most thunderous geniuses, Ovid was not discouraged by his distinguished milieu. He saw it as a new baseline from which he could innovate and modify.

The experience of reading Ovid after reading Horace, Virgil, and Propertius, as we are doing in Literature and History, is a bit like this. You’re watching a violin concerto competition. All the musicians are technical powerhouses. They understand the music intuitively, and their performances are spot on – so good, in fact, than when the final violinist takes to the stage, your ears are just a little tired, and you wonder what this final person can possibly do that will top what’s come before. The last musician takes the stage, and plays an opening movement powerfully – everything is normal, except, maybe, that he has a peculiarly amused expression on his face. And then, in the middle of the second movement, just at the moment he seems to be giving his competitors a run for their money, something happens. He switches his violin and bowing hands, and starts playing left handed, and he’s just as good this way. And then he hops up on the piano bench and starts dancing a jig for each crescendo. And in the last moments of the final movement, he lights his instrument on fire, still playing the final gushes of 16th- and 32nd notes faultlessly, still looking faintly, distantly amused, as though none of it is particularly difficult for him. That, to me, is what reading Ovid is like. He is easily a match for any other Augustan Age poet, but he also has a panache and playful self consciousness that make him who he is. He is a sort of Mozart to Virgil’s Rachmaninoff, every bit as brilliant, but almost always with less gravity and earnestness.

Throughout his career, as Ovid bent the customs of genres and invented new genres altogether, he saw poetry not so much as a means of telling stories to the public, but instead as a giant and often self-referential game. If love poets had written of the cycles of their infatuation and heartache before, Ovid would write tongue-in-cheek stanzas to a likely nonexistent addressee that mocked the enterprise of love poetry in general. If poets of the past had penned great didactic works like the Georgics and On the Nature of Things, Ovid would create earthy, absurd treatises on seduction and women’s facial cosmetics. Ovid was not a jokester through and through. But over the course of his many works, he never hesitated to call attention to poetry itself, and how poetry was a fundamentally mediating, and fundamentally human creation, and not some blazing gift from the gods.

More than any of his predecessors, Ovid believed in language’s power to constitute and alter reality. I want to read a quote from Ovid – one that exemplifies what he thought about poetry. This is the Grant Showerman translation of some lines near the end of Ovid’s third book of Amores, or love poems. Ovid writes,

’Twas we poets made Scylla. . .’tis we have placed wings on [Hermes’] feet, and mingled snakes with [Medusa’s] hair. . .our song made. . .the [Pegasus]. We, too. . .gave to the viperous dog [Cerberus] three mouths. . .and the heroes snared by the voice of the [Sirens]. We shut in the skins of [Odysseus] the East-winds of Aeolus; made the traitor Tantalus thirst in the midst of [Hades]. . .’Tis due to us that. . .Jove transforms himself now to a bird, and now to gold, or cleaves the waters a bull with a maiden on his back. Why tell [the legends] of Proteus, and those Theban seeds, the dragon’s teeth; that cattle once there were that spewed forth flames from their mouths. . .Measureless pours forth the [creativity] of [poets], nor [hinders] its utterance with history’s truth. (Am 3.12.21-42)2

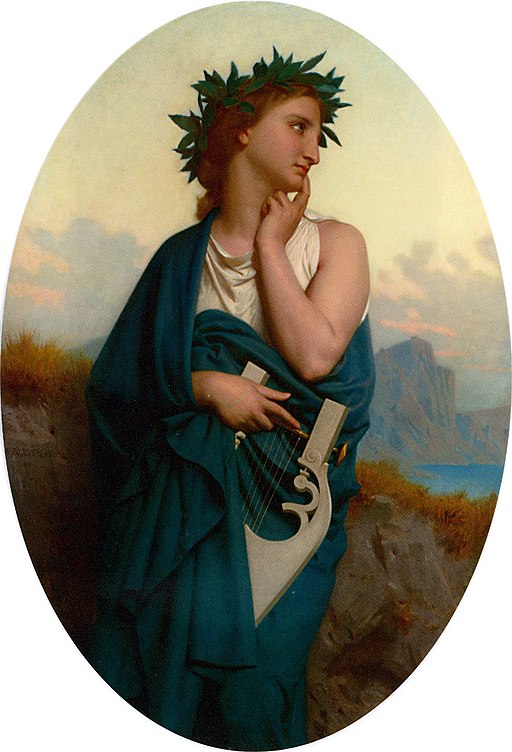

William-Adolphe Bouguerau’s Philomela (1861) captures one of the more prominent figures in Ovid’s Metamorphoses. As we see in the quote above, Ovid had no pretensions of writing factually accurate history anywhere in his broad corpus of works, from the Amores and Heroides onward.

This is an unconventional idea. We tend to like our love poets heartbroken and sincere, and our epic poets earnest and inspired by muses. Classicist Philip Hardie writes that for a long time, Ovid’s “works were to become a byword for a playful detachment from the serious business of life, and as a result went into a critical eclipse during the nineteenth and much of the twentieth centuries.”3 In other words,generations of critics and readers found Ovid’s playfulness, and his constant focus on the mechanics of his own poetry evidence of an unfortunate emotional hollowness – he was, to many, a craftsman and tinkerer and not a man who ever felt anything. These days, however, Ovid’s reputation has recovered so fully that even his obscurer works are being studied and reissued. And what once seemed most disquieting about Ovid – his constant awareness of poetry as an artificial reality – now seems one of his most appealing qualities.

So today, again, we’re going to learn about Ovid’s early works. The Amores are three books of love poems, poems that follow sequences by Catullus, Tibullus, and Propertius, in that they are all dedicated to the same addressee. The Heroides, which we’ll cover fairly quickly toward the end of this show, are epistolary poems, or poems written in letters. The Heroides are a collection of fictional letters, mostly written from famous mythological heroines to their departed lovers – Penelope to Ulysses, Dido to Aeneas, and Medea to Jason, to name some whose stories we’ve covered in this podcast. But before we get into Ovid’s early works, I think we should talk for a moment about Ovid himself – who he was, where he was from, and why he took such an individualistic and distinct path at the end of Latin literature’s golden age. [music]

The Life of Ovid

Our most important source on Ovid’s biography is Ovid himself. Various scraps here and there in his poetry tell us a bit about him, but a long letter in verse that Ovid wrote later in life is the source that we inevitably make use of when we talk about his biography. Let’s take a look at this letter – I’m going to quote about twenty lines from it, and this is the Peter Green translation, published by the University of California Press in 2005. Here’s Ovid, talking about his early life.Who [is this] you read, this trifler in tender passions?

You want to know, posterity? Then attend: –

Sulmo is my homeland, where ice-cold mountain torrents

make lush our pastures, and Rome is ninety miles off.

Here I was born, in the year both consuls perished

at Antony’s hands; heir (for what that’s worth)

to an ancient family, no brand-new knight promoted

just yesterday for his wealth.

I was not the eldest child: I came after a brother

born a twelvemonth before me, to the day

so that we shared a birthday, celebrated one occasion

with two cakes. . .We began

our education young: our father sent us to study

with Rome’s best teachers in the liberal arts.

My brother from his green years had the gift of eloquence,

was born for the clash of words in a public court;

but I, even in boyhood, held out for higher matters,

and the Muse was seducing me subtly to her work.

My father kept saying: ‘Why study such useless subjects?

Even Homer left no inheritance.’ Convinced

by his argument, I abandoned [poetry] completely,

struggled to write without poetic form;

but a poem, spontaneously, would shape itself into metre –

whatever I tried to write turned into verse. (Tris 4.10.1-12,14-26)4

This is only the beginning of Ovid’s self-presentation in this letter. He recalls how just as he and his brother were on the verge of beginning their careers, his brother died. Ovid was just nineteen, and he recollects how “from then I lost a part of myself” (4.10.32). Ovid then began some sort of a public career – one that led to the Senate. But, Ovid tells us, “For such a career I lacked both endurance and inclination: / the stress of ambition left me cold” (4.10.37-8).

Ovid spent the end of his life in Tomis (shown in this map as Tomi), in the periphery of the Roman world, decades after writing the Amores and Heroides.

Next, Ovid tells us, he was married. His first wife, he says, was “worthless and useless” (4.10.70). His second wife was better, but, for whatever reason, also didn’t work out. His third, however, was a keeper. She made him a father, and then his daughter made him a grandfather. Ovid’s parents lived a long time – his father until the age of ninety. Now, a famous factoid about the end of Ovid’s life is that Augustus ended up exiling Ovid to a place called Tomis, in modern day Romania on the coast of the Black Sea. We don’t know why this happened and it’s one of the great mysteries of Roman literature, but by this point Ovid was a very popular author. He writes in his autobiographical letter that “although our age has produced some classic poets, / Fame has not grudged my gifts renown. / There are many I’d rank above me: yet I am no less quoted / than they are, and most read throughout the world” (4.10.125-8).

So that’s the story of Ovid’s life as we have it in the historical record. He was born in the central part of Italy about seventy-five miles east of Rome as the crow flies. His father expected him to have a political vocation and enter law. The death of his older brother scarred him and may have affected his decision to go into poetry. And for whatever reason Ovid chose a literary life, he found himself in an advantageous place and time to write, surrounded as he was by public recitations and famous authors.

Elsewhere in his poetry, Ovid remembers the moment when he chose poetry over law, and how his family reacted to this decision. “You call my verse the work of wit misused,” he writes in one of his Amores, perhaps addressing his father or another family member,

And claim my youth disdains our Roman fathers’ ways,

Spurning to chase the soldier’s dusty bays.

You say I won’t learn verbose legalese, or sell

Myself as thankless Forum mouthpiece? Well,

This “work” you want will die some day. The work I do

Will live in deathless verse, the whole world through. (Am 1.15.1-8)

He sounds a bit like a puffed up and shrill teenager until you remember that Ovid actually did become one of the most heavily circulated Latin poets for a thousand years. This seems to have been his aim. In one of his poems he recollects how just as Verona gave rise to Catullus and Mantua gave rise to Virgil, Sulmo would one day be famous for having produced him (Am 3.15.7-8). Ovid understood himself as having taken a prominent, specific place in the evolution of Roman literature. Scholar Richard Tarrant notes that Ovid’s “references to other writers, and to his work in relation to theirs, are more numerous than those of any other Roman poet.”5

Pieter Bruegel the Elder’s Landscape with the Fall of Icarus (c. 1558). Icarus’ tale appears in Book 8 of Ovid’s poem, and this particular painting and scene have an added significance in Anglophone literature, as W.H. Auden’s Musee des Beaux Arts is about this painting, and Icarus’ rather minor and incidental appearance in its periphery.

The rhetorician Quintilian, born about a hundred years after Ovid, had a high opinion of a lost work by Ovid – his tragedy Medea. Quintilian wrote, “[T]he Medea of Ovid shows, in my opinion, to what heights that poet might have risen if he had been ready to curb his talents instead of indulging them” (Ins 10.1.98).7 Ovid did indulge his talents a bit too often in Quintilian’s opinion, however – the ancient critic observed that “Ovid has a lack of seriousness even when he writes epic and is unduly enamoured of his own gifts, but portions of his work merit our praise” (Ins 10.1.89). Another source on Ovid – Ovid’s contemporary Seneca the Elder – wrote that the poet showed excellent promise in oratory before turning to poetry instead (Cont 2.2.8), and that oratory formed a strong base for Ovid’s literary efforts.

Now, a minute ago I mentioned that Ovid produced a version of Medea, and that this tragedy was extremely highly regarded in Rome, although it’s now lost. Even though we’re just covering two of Ovid’s early works today, I want to introduce you to the full scope of his work upfront. There’s a general consensus that accurately dating Ovid’s works is pretty much impossible, so much of what I’m going to tell you is going to be estimations, and they’re taken from Harold Isbell’s translation of Ovid’s Heroides, published by Penguin Classics in 1990.

First of all, Ovid appears, unlike Virgil, to have often been at work on several projects at once, and several very different projects, at that. Between the ages of about 23 and 33, Ovid was working on his love elegies, the Amores, and also the Heroides – those love letters between mythological characters. You’ll know that material by the end of today. At some point before the age of 40, he wrote a version of the tragedy Medea, which was highly regarded. Also likely while in his 30s, Ovid wrote a trio of satirical didactic works, the Ars Amatoria, a manual on seduction for the modern Roman, the Remedia Amoris, or “cure for love,” a sort of companion piece explaining how to get over heartache, and the mostly lost Medicamina Faciei, a work about women’s facial cosmetics.

Just as Virgil began the Aeneid around the age of 40, Ovid began two major works at about the same age. The Metamorphoses was a sprawling compilation of myths having to do with transformation, while the lesser known Fasti is a catalog of Rome’s festivals and how they fit into the astronomical calendar. This takes us up to about 8 CE, the year that Ovid was exiled. Ovid’s exile interrupted the composition of his Fasti, which stands as only half complete. And while living up on the shore of the Black Sea, Ovid continued to write. As he neared the age of fifty, Ovid wrote the Tristia, poems lamenting his exile and trying to find a way back home. His Ibis, also written in exile, is a long tract against one of his enemies in Rome. And finally, the Epistulae ex Ponto, which he wrote just before and after turning fifty, are letters to friends back home, asking them to help him find a way to return.

From tragedy to love poems; from epistles to didactic manuals; from a catalog of national holidays to a full scale epic and numerous other autobiographical materials, Ovid was nothing if not prolific. At the beginning of his career, however, the part that concerns us today, a single poetic structure seems to have captivated him more than any other. This structure is called the elegiac couplet, and it’s long past time that we explored it in detail. [music]

Elegiacs and Elegiac Couplets

I’m going to give you a definition of elegiac couplets, and then we’ll look at some examples from Ovid. This is a subject that’s simultaneously really, really fun and difficult to explain, but once you understand it you will understand why elegiac couplets are such a delightful part of the history of poetry.First, most simply, a point of clarification. In English, elegy most commonly means a solemn speech or poem lamenting the dead, or moreover some tragedy or unfortunate turn of events. Let’s get that out of our heads. Elegiac couplets are something different – when classicists talk about love elegies like the ones Propertius and Ovid wrote, they simply mean poems written using elegiac couplets – it has nothing to do with bewailing something sad or anything like that.

With that clarification established, let’s start with the textbook definition of elegiac couplets. An elegiac couplet, being a couplet, is of course a pair of lines. Each line is made up of a hybrid poetic meter. It would be bewildering to explain this meter using the relatively esoteric language of poetic scansion alone. Here’s what they sound like in Latin, thanks to my friend Lantern Jack from the Ancient Greece Declassified podcast for reading this bit out with particular attention to meter.

Arma gravi numero violentaque bella parabam

edere, materia conveniente modis.

par erat inferior versus—risisse Cupido

dicitur atque unum surripuisse pedem. . .

Sex mihi surgat opus numeris, in quinque residat:

Ferrea cum vestris bella valete modis!

Cingere litorea flaventia tempora myrto,

Musa, per undenos emodulanda pedes!

It is an exotic sounding meter, its initial line longer than its subsequent line. And aside from letting you hear it in Latin, I thought maybe the best way to explain elegiac couplets was to use elegiac couplets to do so.

ELL-uh-giac COUP-lets-be GIN-with-five DACT-yls-then FIN-ally-a SPOND-EE

THEN a line THAT’S shorter AND / SOUNDS kind of TERSE and un PLANNED.

THE-first-line’s LONG-er-and DRAWN-out-it SETS-up-a GRAND-i-ose SPI-RIT

NEXT comes a SHORT line of VERSE / VERy com PACT, even TERSE

PO-ets-like OV-id-en JOYED-el-e GI-acs-be CAUSE-they-sound PLAY-FUL

ONE line is LONG then one’s CURT / PERfect if YOU need to FLIRT

DACT-yls-are FEET-that-go LONG-short-short THIS-line-has FIVE-then-a SPOND-EE

THEN-this-weird HY-brid-in STEAD / CON-cludes and STICKS-in-your HEAD.

So the meter is,

LONG short short LONG short short LONG short short LONG short short LONG short short LONG LONG

LONG short short LONG short short LONG / LONG short short LONG short short LONG

If we were reading in Latin, this is the point where we’d look at Ovid in his original language. Any Latinists listening right now are probably tearing their hair out, because even in that fairly elaborate explanation I’ve simplified things – the feet in each line line aren’t necessarily dactyls. But, English speakers that we are, we have to rely on translations that approximate elegiac meter, and for our purposes the most important thing to remember is that the first line of an elegiac couplet is long, and the second is short and snappy.

Now, I tracked down a really terrific translation of Ovid’s Amores by a poet named Len Krisak, published by the University of Pennsylvania Press in 2014. Krisak’s translation actually adapts elegiac couplets into English to try and give a sense of what Ovid is actually like in Latin. Let’s look at a pair of elegiac couplets – four lines total. Now these lines are not true Latin elegaics – in other words they don’t go replicate the exact syllabic structure of Latin elegiacs. Instead, Krisak uses iambic hexameter, followed by iambic pentameter – because dactyls are a pain in the neck to handle in English. And by the way these lines will not only replicate the lopsided feel of elegiac couplets, but also offer a crash course on Ovid’s amusingly cynical perspective on love and romance. Ovid writes,

You’re beautiful, so I expect you to give in,

But please don’t tell poor me your every sin.

I’m not your censor. You’re unchaste, and I’ll abide it.

I’m only asking you to try to hide it. (Am 3.14.1-4)

Now both of those couplets went from iambic hexameter to iambic pentameter – from six to five – forgive me if this is pedantic but I’m going to lightly tap my microphone for each metrical foot, and you should hear six beats, then five beats, then six beats, then five beats.

You’re beautiful, so I expect you to give in,

But please don’t tell poor me your every sin.

I’m not your censor. You’re unchaste, and I’ll abide it.

I’m only asking you to try to hide it. (Am 3.14.1-4)

Again, it’s not an exact replication of Latin elegiac meter, but what Krisak recreates is that cockeyed, asymmetrical feel – a long line, and a shorter line. And note, by the way, that the rhymes in this translation are an Anglophone invention – Ovid’s own lines don’t rhyme.

Anyway, as you probably felt there, the alternating cadence of elegiac couplets creates a very distinct feel. An initial line seems to set up an expansive statement using a protracted meter, but the subsequent line is shorter, curtailing the expected rhythm in a way that is often anticlimactic, funny, flirtatious, or self-consciously succinct. Because almost every elegiac couplet is a self-contained statement, they are genuinely easy and fun to read, each pair of lines its own kernel of information, couplet after couplet, without long sentences that span many lines. Ovid loves the form so much that he not only uses it extensively in his poetry, but also writes about it, as well.

Here’s Ovid, in a charming little passage from the Amores about how he came to enjoy writing elegiac couplets.

Below [the] forest roof, while walking fro and to,

I wondered what my Muse would have me do.

Then Elegy arrived, perfumed and coifed for sport;

One foot was long though, and the other short.

Her face beamed love; her form was fine; thin was her dress.

Yet one foot-fault made extra loveliness! (Am 3.1.5-10)

Here, using couplets that alternate structurally between the first and second lines, Ovid recollects getting to know the elegiac couplet for the first time, and likens the form to a beautiful woman with one leg shorter than the other, beautiful precisely because of her asymmetry.

Elegiac couplets were so central to Ovid as a poet early in his career that he begins the Amores by talking about them in a way that very deliberately distances himself from Virgil. Virgil had begun the Aeneid with Arma virumque cano, or “I sing of arms and a man.” Ovid begins his Amores with the same word: Arma, writing, Arma gravi numero violentaque bella parabam / Edere, materia conveniente modis, or, as Len Krisak translates it, “Prepared for war, I set the weapon of my pen / To paper, matching meter, arms, and men” (Am 1.1.1-2).8 Ovid prepared for a great epic in hexameter, he tells us, only something quite unexpected happened.

Prepared for war, I set the weapon of my pen

To paper, matching meter, arms, and men

In six feet equal to the task. Then Cupid snatched

A foot away, laughing at lines mis-matched. . .

He bent that reflex bow of his against one knee,

Saying what burden he had meant for me:

“Receive this barb, my bard.” Well, Cupid is the best

Of archers, so that bolt burns in my breast,

While six feet rise and five pronounce my clear decline

In elegiacs. Farewell, epic line. (Am 1.1.1-4,23-8)

It’s a funny, intensely self conscious story. Ovid tells us that the epic hexameter line tempted him, but from the get-go, he preferred the playful, anticlimactic form of the elegiac couplet, a form associated with love and romantic banter rather than gods and warfare. And throughout the Amores Ovid deploys elegiac couplets with charm and mastery, creating some of the most magical pairs of lines in Latin. It’s little wonder that as he reached the age of fifty he could look back on his career and brag about being one of the most quoted men of his day – his elegiacs are eminently quotable. Here’s some quick examples. He tells his lover in one pair of lines, “Your face makes for desire, but your deeds, disgrace, / And in this war, the winner is your face” (Am 3.11b.11-12). In another poem, Ovid regrets that “My one-time love, who started up with only me, / I see is now Rome’s common property” (Am 3.12.5-6). In couplet after couplet, moving from six feet to five feet again and again, Ovid uses the elegiac form to set up grand statements, only to finish them off with something funny, or flippant, or cynical, each couplet its own capsule of information.

Now, Latin love elegy is never simple. Ovid’s predecessors mix their poems of devotion together with poems of bitterness, and often seem more interested in writing love poetry than actually winning over their mistresses or enjoying the fruits of their courtships. But Ovid himself, in the Amores, writes to a mistress who was probably fictitious in the first place, and his poems toward her are so charged with irony, so studded with literary references to other poets, and so filled with puns and quips that they are clearly more literary diversions than romantic entreaties. The elegiac form was the ideal vehicle for these diversions, sounding at once magisterial and anticlimactic, a clubfooted structure that allowed Ovid to subvert his reader’s expectations in almost every other line.

Alright, well so far, we’ve discussed Ovid’s biography a bit. And now you know that elegiac couplets are couplets in which the first line is longer and more grandiose than the singsong second lines, and that they’re generally logically self contained. With this background established, I think we’re ready to look at our first work by Ovid, the collection of love poems that he called the Amores.

Tongue-in-Cheek Romance: An Introduction to Ovid’s Amores

We’ve already read some Latin love poetry in this podcast. In the relationship between Catullus and Clodia, we watched a poet go from boyish infatuation, to consummation, to being betrayed and responding to this betrayal with bitter anger, to moving on and coping with his heartbreak. We saw Propertius in a fraught relationship with his lover Cynthia, generally seeking a stable relationship but never getting it, and in his final book of elegies, giving up to write about other subjects. Neither Catullus nor Propertius are entirely loyal to their mistresses, and each lashes out in frustration. Nonetheless, the two earlier poets did seem to find the elegy a form that allowed them to convey at least some sincere emotion, whether love or spite; a form they could use to transpose the private world of their romantic experience into a world of poetry.During the Renaissance, what writers like Petrarch admired about Latin love elegy was its potential to convey sincere romantic emotion. Seeing the smitten stanzas of writers like Catullus and Propertius, Renaissance poets sought to imitate their infatuation and lonely ardor. Ovid, however, if the Amores can serve as evidence, was far more interested in poetry itself than in using poetry to find love. His three surviving books of love elegies, while not without moments of devotion and sincerity, pervasively seem to see the exercise of writing love poetry as a particularly fun game, or as one scholar puts it, “the poetic cart, so to say, is put before the amatory horse.”9

In his first book of love elegies, Ovid makes a comparison that’s not uncommon in Latin poetry, exploring the parallels between a young man in love and a young man at war. Propertius had done this (2.14), and concluded that his amorous triumphs were better than military ones. Ovid, however, is less earnest in his comparison of love to war. Ovid writes, in the Len Krisak translation,

The spirit captains seek in soldiers is the same

Young women want in those who play love’s game:

Men who’ll watch all night, and sleep on ground that’s hard;

At bedroom door, or camp, they’ll stand their guard. . .

And who but lovers will, like soldiers, stand the chill

Of night, or sleet that bores down like a drill?. . .

Always it’s yearning lover’s, soldier’s, sacred duty

To penetrate the lines that guard great booty –

Or beauty. (Am 1.9.5-8, 15-6,30-2)

The comparison is ridiculous, and Ovid seems to know it. A young lover waiting by his mistress’ door is nothing like a soldier on campaign, and Ovid sets up the comparison with such deft satire that we can’t help but laugh at its outrageousness.

Elsewhere, Ovid pokes fun at other specific conventions in love elegy. One of these has to do with mourning the death of a beloved’s pet. Catullus’ third poem laments the death of his lover’s sparrow, recollecting how pleasing the little bird was for her, and how now the bird will make a journey into the underworld. Catullus’ sparrow poem sits on the line between tragic and just a little bit silly. It is, of course, sad for anyone to lose a pet, but the vehemence of Catullus’ lamentation is perhaps more than one would imagine is strictly called for. Ovid almost certainly read Catullus’ sparrow poem, because Ovid writes a similar poem, only on the loss of his beloved’s parrot. And while Catullus’ sparrow poem is certainly a little bit sad, Ovid’s parrot poem doesn’t seem to have a grain of seriousness in it. Ovid writes,

Her parrot, feathered mime from India, has died.

Come crowd his grave, birds; come from far and wide,

Devoted fliers. Beat your breasts with wings. Come, bands

Of birds, and scar your cheeks with crooked hands. (Am 2.6.1-4)

The best die young, by greedy hands; they are the first

To go, while years and years attend the worst. (Am 2.6.39-40)

[And Ovid remembers the tragic circumstances of the parrot’s death, and addresses the deceased parrot.]

Then came the seventh dawn, with no more dawns behind it;

You watched Fate stop her spindle, then unwind it.

And yet your weakened palate wouldn’t let words die;

Your weak tongue said, “[Mistress], it’s good-bye.”

Beneath a hill, black ilex stands. Elysian trees –

And earth – grow vibrant green eternities.

Believing doubtful things, we hear, “Good birds go there.”

(Dead dirty birds get sent some otherwhere.) (2.6.45-52)

Ovid’s parrot poem, an overblown eulogy, treats the death of his imaginary lover Corinna’s bird as a great modern tragedy. A hat tip to Catullus, the poem serves as a good introduction to the way that Ovid wrote love lyrics in general. Love poems, to Ovid, were not so much pieces of persuasive rhetoric designed to woo mistresses. They were contributions to an existing and increasingly crowded genre, and the more they showed conscientiousness of the history of that genre, the better. [music]

The Narrator and Romantic Morality of the Amores

By the time you find yourself about halfway through the second part of Ovid’s Amores, it’s clear that you’re reading a work of fiction, written by a caddish speaker as a series of unfolding dramatic monologues. In one poem, Ovid is defending himself against his mistress’ accusations that he’s been sleeping with the slave who does her hair. Ovid is indignant at the accusations, and asks his lover why in the world he’d seek a slave girl’s love, and then adds,Besides, her only job’s to dress your hair – a task

She pleases with. That’s all that you could ask.

So why would I seduce your more-than-faithful maid,

Only to end up spurned and then betrayed? (Am 2.7.21,23-6)

The lines have all the resentment of a dedicated lover who has in truth not strayed from his mistress. Only, the opening of the very next poem reveals that Ovid has indeed been sleeping with the slave in question, after all. He tells the slave hairstylist,

You ought to dress the hair of goddesses, Cypassis!

Skilled in a thousand styles no maid surpasses,

You’ve made me see you’re far from dull at furtive love,

Deceiving one whom you’re the mistress of.

But who’s the snitch who pointed out this little fling,

Tipping Corinna to our trafficking? (Am 2.8.1-6)

We can look for the monogamous, lovelorn poet in Ovid’s Amores and find something else – a freewheeling Casanova fond of unexpected turnabouts who is pervasively more interested in pursuit than consummation. For instance Ovid tells the husband of a woman he’s pursuing, “Guard her for me, if not for you; bolt her door, / You dolt. That way, I’ll want her all the more. . .I’m warning you! If you don’t lock her in a vault, / My interest in her crashes to a halt! ” (Am 2.19.1-2,47-8). Notwithstanding the disquieting reference to women being imprisoned at home here, the message is clear. Ovid isn’t looking for love everlasting. He’s looking for a fun pursuit.

One of the funniest poems in the Amores is the final poem in the second book, a lengthy piece in which, amidst other things, Ovid tells a new lover how to keep his interest. His message for her is hardly that she should submit to his entreaties and allow him to make love to her. Instead, Ovid writes, in some particularly delicious elegiac couplets, in the Len Krisak translation,

Now you, my newfound dear who’ve won my wandering eye,

Pretend some fear. . .and when I beg, deny.

Please let me stretch out on your threshold. Let me feel

The cold nights; bind me on their frosty wheel. . .

But girls who mean to rule for long should learn to cheat. . .

Though spare me, clement gods, from such deceit.

Whatever happens, then, the easy’s not for me:

What flees, I follow; what follows, I flee. (Am 2.19.19-22,33-6)

In these lines we come to understand that Ovid, or we should say the speaker of Ovid’s love elegies, enjoys the thrill of pursuit, and the sport of courtship. Love poetry is not a means to an end, but an end to itself, and thus Ovid seeks not so much a consummated relationship as a situation which will encourage the further production of love poems.

Now, this isn’t to say that Ovid’s poetic persona is that of a virginal artist. The fifth poem in his first book of love poems explicitly describes sex with Corinna – sex that borders on the violent. Ovid was not the first love elegist to write torrid accounts of violent sex – Propertius had done the same, but Ovid’s early recollection of making love with Corinna is more drawn out than Propertius’ accounts of sex with Cynthia.10 Let’s look at Ovid’s lengthiest sex scene, fairly tame for what it is.

Then came Corinna in her tunic cinched and sheer;

Her fair neck felt her parted hair fall clear.

I snatched that tunic from her, and it caused no harm,

But still she fought me for it in alarm.

She fought like one who fought a battle not to win,

But struggled weakly, only to give in.

And as she stood, a sweet disorder in her dress,

Her body showed no fault; my eyes said yes.

Such arms I saw and touched – soft, lean and strong, yet fine!

Her round breasts fit two hands – and they were mine! (Am 1.5.9-20)

I don’t think too much analysis is necessary there – a male speaker recollects a possibly not-entirely-consensual sexual encounter with a lover, at the climax of which he exultantly recalls touching her naked body.11 In the next episode on The Art of Love we’ll talk more about Ovid and the issue of consent, but let’s stick with the Amores for now. Elsewhere in the Amores, Ovid makes it clear that his relationship with Corinna was – quite thoroughly – consummated. A poem in the third book of the Amores recollects an embarrassing episode of erectile dysfunction when sleeping with a different and new lover, but then, in the speaker’s defense, recollects how once he satisfied Corinna’s desires nine times in a row (3.7.23-6). Whether or not Corinna was a real person, then, and whether or not the Amores chronicle a real relationship, the speaker of the poems fancies himself a poetic and sexual juggernaut – one who takes pride in both his literary creativity as well as his virility. [music]

The Concision and Blunt Realism of Ovid’s Amores

What’s most remarkable about Ovid’s Amores isn’t that the poems tell a compelling love story, nor that they strike out in revolutionary new directions. The poems in the book are instead remarkable for their style, their concision, and their knack for reworking scenarios found in earlier love elegists. As scholar Philip Hardie observes, “Many individual poems of the Amores contain ironizing rewritings of elegies of Propertius and Tibullus, and the originality of the collection as a whole consists in the novel slant it gives to well-worn themes.”12 Ovid’s predecessors had already given posterity a wide array of love elegies that ran the gamut between elated and heartbroken – Ovid’s contribution to the elegiac form was bringing a new brio and sophistication to it.This brio and sophistication often appear in the way that Ovid tells stories in the Amores. At one point in the second book of the Amores, he tells the entire narrative of an attempted and failed seduction in just four lines. Ovid writes,

I saw; she pleased. I said “I want you” in a note.

In shaky script, “I can’t,” is all she wrote.

I sent back, “Why?” But her note, not to be out-quicked,

Shot back, “The watch he keeps is far too strict.” (Am 2.2.5-8)

That’s the whole story Ovid offers on the subject, an archetypal situation he obviously felt required no further elaboration. Ovid’s Amores paint a picture of adultery and illicit courtships as casual and commonplace, where jealous husbands can never quite keep their sexually adventurous wives under control, and where a small army of lusty poet-scoundrels wait around dinner tables to ply their wares on willing women. In this world, flirtation is a great art form, a subtle craft that allows men and women to lead one another on through a series of clandestine signs and displays. Attempting to seduce a married woman, the speaker of one of Ovid’s poems tells her that he knows she has to go to her husband, but

[W]hen he lies down on the couch, go modestly,

[And] brush against my foot in secrecy.

And watch my subtle looks, my eyes, communicate;

Catch all my hints. . .and then reciprocate. (Am 1.4.15-8)

In Ovid’s delicate craft of courtship and seduction, the smallest performances can reveal willingness or unwillingness, lust or rejection, and everything in between. But notwithstanding the intricacy of the erotic world depicted in the Amores, Ovid’s main concern in the collection is the enterprise of poetry itself. And some of his most impassioned moments come not from frustrations with reluctant mistresses, but instead frustrations with writing itself.

At one moment, having sent poetic romantic entreaties to his addressee Corinna, Ovid receives rejections from her (Am 1.12.7-8,13-14). He focuses not on his bitterness to Corinna, but instead the wax tablets that she sends him, wishing them tossed into a public thoroughfare and crushed by wagon carts. In this, and many other moments, sexual rejection is secondary to the sting of literary rejection. Sex and love might be pleasant by-products of writing love elegies, but the real goal is literary notoriety.

Elsewhere, toward the end of the last book of the Amores, Ovid reflects on the enterprise of love poetry in general, and how his elegies have lifted their addressee out of obscurity, but done little comparable for him. “In fact,” he writes, “the folk thought more of you because of me: / My love made others love you, don’t you see?” (Am 3.11a.1-4,17-20). Two poems later, Ovid develops this idea quite a bit further, and acknowledges the fact that his poetry has done his mistress far more good than it has him. He writes, again near the very end of the Amores,

Why did I proclaim her form and face

Until my verse became her marketplace?

My pandering means she pleases louts procured by me.

Her gate lies open; all the world can see.

So. . .verse? I have my doubts; it doesn’t do much good

For me – at least not what I wish it would. (Am 3.12.5-14)

We don’t exactly feel sorry for the Ovidian speaker here. He’s hardly presented himself as Corinna’s tireless devotee. Nonetheless, in this poem we do see him coming up against the limits of what poetry can accomplish. Dozens of marvelously coy poems, evidently, have made Ovid’s addressee into a legend, and left him in obscurity.

Ary Scheffer’s Orpheus Mourning the Death of Eurydice (1814). Ovid’s experience writing love poetry in all its permutations at the outset of his career helped prepare him for the many romantic stories that appear in the Metamorphoses.

From what I’ve told you about the Amores so far, they may sound like the work of a purely selfish cynic. Earlier, we heard scholar Philip Hardie’s summary that for a long time, “[Ovid’s] works were to become a byword for a playful detachment from the serious business of life.” Love poetry, during and after the European renaissance, in the lines of poets like Petrarch, Philip Sidney, and Edmund Spenser, was a serious, profound business. The courtly love literature inherited by the Renaissance, too, painted romantic love as the central absorption of the European gentry, its Tristans, Lancelots, Percevals, Erecs, and Yvains embarking on sequences of adventures that center on often heartbreaking romantic experiences. While these generations never stopped enjoying Ovid’s Metamorphoses, his Amores were out of step with the romantic ideology of the Early Modern period.

But before we leave Ovid’s Amores entirely, let’s have one final thought about these poems. I think we can easily read Ovid’s early love poems as exercises in cynical self aggrandizement – dizzyingly brilliant in their composition but at the same time pathologically insincere. This is often how they have been read – as literary exercises that ultimately reveal Ovid’s pessimism and emotional sterility. They may do just this from time to time. But they also reveal a level of intelligence and hardheaded realism that sets Ovid’s elegies apart from thousands of years of love poetry. The Amores are not love poems for fourteen-year-olds with tearstained sleeves. They are love poems for grown ups, who realize that although love is a central and defining part of human experience, it is not the only part.

There is an extremely famous poem by one of Shakespeare’s contemporaries that I think concisely illustrates the differences between Ovid and many of those who came along after him. John Donne’s “The Sun Rising” is one of those poems that English majors read to their girlfriends or boyfriends at the age of eighteen, when we first start discovering voices in the literary canon that speak to our emotional experiences. “The Sun Rising” is a truly lovely poem, and I’ll quote some of it for you. The English poet John Donne, in the early 1630s, wrote about walking up with his lover, presumably after a night lovemaking, and feeling sad that the sun had to rise and their night together had to end. Donne wrote,

Busy old fool, unruly sun,

Why dost thou thus,

Through windows, and through curtains call on us?

Must to thy motions lovers’ seasons run?

Saucy pedantic wretch, go chide

Late school boys and sour prentices,

& Go tell court huntsmen that the king will ride,

Call country ants to harvest offices,

Love, all alike, no season knows nor clime,

Nor hours, days, months, which are the rags of time.

Thy beams, so reverend and strong

Why shouldst thou think?

I could eclipse and cloud them with a wink,

But that I would not lose her sight so long.

Well, it’s a terrific poem, and it goes on for a couple more stanzas. Donne ultimately describes love as the center and pivot of the world, and emphasizes that his relationship is something loftier than the deeds of nations, kings and princes, and that time seems to be standing still in the incandescent moment of their coming together.

Ovid has a very different poem involving a rising sun – one that’s funny and refreshingly different than the main line of European love poetry. While Donne brags that by closing his eyes he can eclipse the sun and be lost in the breathless moment of his new love, the rising sun in Ovid’s poem isn’t so easily overcome. Ovid writes,

So many times I prayed that Night should not give way

To you [, sun]; that stars might see your face, yet stay.

I prayed so often winds would smash your axle and

Your cloud-crashed team would plunge into the land. . .

My rant was done, and oh, she blushed at what I’d said.

Still, at six sharp – not nine – the day broke red. (Am 1.13.27-30,45-6)

There’s nothing cynical about these lines, really. It’s just that Ovid refuses to do anything but tell the truth. We may spend wonderful nights with one another, but in the morning, the sun comes up, and quite promptly at that. While the Amores can be outright pessimistic about love, sometimes their cynicism, and their staunch pragmatism is their most endearing quality. Life, after all, does not stop after a romantic consummation, nor should heartbreak ever drive us to self-destruction. In the midst of European poetry’s often stale potpourri of impassioned courtships, revelatory unions, and devastating losses, Ovid’s levelheaded realism about human relationships often makes him seem more modern than his Renaissance heirs, rather than the other way around. A Dante, or a Petrarch could write of love as the fulcrum of their emotional and spiritual lives, but Ovid’s world was more complex. In the Amores, love exists in many gradients, from the sacred and sincere to the smutty and carnal. Ovid’s elegies show love as the pursuit of innocent youths, but just as often the recreation of married adults seeking titillation or more in their leisure time. And perhaps more than any other love poet, Ovid in the Amores is open and honest about his literary ambitions. He does not, after all, try to have it both ways, seeking literary laurels and sexual conquests side by side. He is a poet, first and foremost, and he seeks literary innovation over and above whatever effects his lines happen to produce in the real world.14 It is true, as one scholar noted above, that for a long time Ovid was seen as detached and chillingly insincere. But if we read the Amores carefully, we see something more than frivolity and literary ambition. Ovid shows an expansive and unsentimental grasp of human love in all its permutations, a compelling portrait of how the Roman aristocracy spent their leisure time, and an ambitious writer who refused to pretend to be anything but. John Donne and his predecessors during the Renaissance might have found Ovid’s early love poems too slippery, and too disingenuous to capture the seriousness of human love, and adapted Ovid’s archetypes to early modern culture.15 But Ovid was quite serious nonetheless. In Ovid, after all, love can be wonderful, but the sun, regardless of our fantasies, always comes up in the morning. [music]

Forlorn Lovers Gazing Out to Sea: The Heroides

Ovid probably released the Amores in two separate installments, the first around 20 BCE, and the second a decade later, which would mean he was writing them between the ages of about twenty and thirty-three. During this same period – perhaps around 15 BCE, Ovid released a collection called the Heroides, or “the Heroines,” a set of fifteen imaginary letters written from famous mythological heroines to their lovers and husbands.16 At some point, he added six additional letters in which heroes respond back to their heroines, allowing Ovid to capture the interior emotional experiences of both sides of his mythological romances. Let’s talk about the Heroides a bit.

Etty William’s Hero and Leander (1828). Ovid’s presentation of this pair’s story is perhaps their most prominent appearance in literature.

I want to start with a simple example, an example which involves a pair of lovers we haven’t encountered before in Literature and History – a pair called Hero and Leander. Hero and Leander live on the opposite sides of the Hellespont, which today we call the Dardanelles, where a channel of seawater that connects the Mediterranean with the Black Sea narrows to about a mile just west of what today is Çanakkale, Turkey. Hero, the girl, is a priestess of Aphrodite who lives in a tower on the west side of the Hellespont, and her lover, Leander, is a young man who lives on the other side of the channel of water. In the central part of the myth, Leander falls in love with Hero, and he swims across the channel to go and visit her, and she leaves the light on in her tower so that he can see where to swim. Eventually, while he’s attempting to swim the strait in a winter storm, he gets lost and drowns, and Hero, seeing her lover’s corpse float up on her side of the Hellespont, throws herself from her tower to her death so that she won’t have to live without him. This simple, elementary tale of love found and lost shows up all over literary history, and Ovid was one of the earlier writers to come along and give it a more extensive treatment.

Hero and Leander show as one of Ovid’s three pairs of lovers – in other words unlike most of the relationships in the Heroides, we get to hear both sides of the story in his dual letters of Hero and Leander. Let’s hear Leander’s recollection of one of their trysts – this is the Harold Isbell translation, published by Penguin in 1990.

. . .Going to you [Leander remembers,]

I swam in strength and ease; leaving you

I swam exhausted, tired, like a man shipwrecked.

I tell you, it seems now that I am

always gliding toward you but my return is

across a steep slope of dead water.

Unwillingly, I come back to my own land;

unwillingly, I wait in this town.

Why are our souls joined while the waves divide us?

We are of one mind but of two lands.17

It’s a simple, elemental picture – a pair of lovers separated not only by their different nationalities, but also by a formidable geographical barrier, and Ovid’s twenty-one Heroides are filled with such impediments to happy relationships. While Leander reminisces on their courtship and the arduous labor of swimming across the Hellespont to see Hero, Hero worries about him. At one point, she imagines a place where they might come together, writing, “Let us / then meet midway and exchange kisses / on the cresting waves before returning both / of us to the towns from which we came” (197). But she knows that such a fanciful meeting is implausible, and the correspondence between the two lovers ends with a foreboding sense of Leander’s death. Hero tells her lover that she’s dreamt of a dolphin that washed up dead on the shore next to her, and yet the ominous dream does not stop her from telling him, “Now the surf begins to be weary, I hope / this means that a calm will soon be here. / Part its gentle ways with every strength that you / can summon to your aid, come to me” (198). As is often the case in classical retellings of myths, the audience knows how the story ends, and the unfortunate characters do not.

Angelica Kauffman’s Ariadne Abandoned by Theseus (1774). The Heroides are filled to the brim with heroines courageously and articulately trying to make sense of being left behind.

So even so far, this has been a long catalog of forlorn and abandoned female speakers. Eighteen of the twenty-one Heroides are letters from women to absent lovers. Generally speaking, from the powerless Hero to the formidable Medea, Ovid’s heroines suffer heartache with no real recourse to justice. Even the letters themselves have uncertain fates. Penelope writes to Ulysses, Ariadne writes to Theseus, Phyllis writes to Demophoon, but in these cases and others the heroines would have had no idea of where to send their letters. In some ways, then, the principal speakers of the Heroides are impotent scribblers, railing against wayward lovers and cruel fate in a long series of documents that lay bare their emotional worlds.

But while the titular characters of the Heroides are often powerless, by virtue of writing the epistolary collection Ovid nonetheless worked to draw attention to the female side of Greco-Roman myth, and to a series of stories in which male adventurers march forth to glory on the backs of female helpers. As scholar Alison Sharrock puts it, “More than any other non-dramatic ancient poetry, male-authored as it overwhelmingly is, Ovid’s work gives space to a female voice, in however problematic a manner, and to both male and female voices which reflect explicitly on their own gendered identity.”18 Ovid’s female speakers, notwithstanding their powerlessness, nonetheless possess, and make use of their rights to express themselves in writing, an act which at least memorializes their experiences, if nothing else. Sometimes, this act of memorialization is particularly powerful, as it is in Ovid’s letter from Hypermestra to Lynceus.

Hypermestra and Lynceus, while they were familiar to Ovid’s audience, are not quite so well known today outside of classics, so let me quickly retell you their story. Once, an Egyptian king had two sons. Having two heirs, he had a tricky situation on his hands. After all, eligible male heirs tend to go to war with one another. Weirdly, both of the princes ended up having fifty children each – one prince, Aegyptus, had fifty sons, and the other prince, Danaus, had fifty daughters. When the old Egyptian king died, Danaus, the guy with the daughters, inherited all the king’s African territories, while Aegyptus, the guy with the sons, inherited all the king’s Arabian territories.

The two sons of the dead king scratched their heads and tried to figure out what to do with their father’s newly bifurcated territory. Aegyptus, who had fifty sons, wanted his boys to marry the fifty daughters of Danaus, which would effectively give Aegyptus and his sons all of Danaus’ property, since males controlled the property of the women they married. Danaus was reluctant, but eventually he agreed. Only, Danaus did something devious, and told all of his daughters to kill all of their male cousins on their wedding nights. One daughter, Hypermestra, would not do it. She may have actually been in love with her male cousin Lynceus, and she may have just been grateful that he didn’t hurry to take her virginity on their wedding night – accounts differ. Because Hypermestra did not kill Lynceus, she was imprisoned, and her letter to her husband allows Hypermestra a chance to vindicate herself and expose the morally disgusting situation into which she was thrown. Hypermestra writes,

Because I was

faithful I am confined in this house,

bound tightly with heavy chains. My hand could not

thrust a steel blade into a throat so

I am charged with a crime; if I had done it,

I would be praised as a heroine. (125)

Hypermestra’s letter allows her to have the last word, as well. Hypermestra remains proud up until the very end that she wouldn’t commit murder, and in the closing lines of her letter, she writes her own epitaph.

Entomb [, she writes]

My bones when you have wet them with tears

and let these few words be carved above that place:

‘Hypermestra, in exile, suffered

the sad death she saved her brother from dying,

an unjust reward for piety.’ (129)

Hardly triumphant in life, then, Hypermestra’s letter does seem to promise some comeuppance to posterity. As classicist Duncan Kennedy notes, the Heroides collectively possess “a poetics of ‘writing in isolation’ which has at its heart a cry, destined to be repeated, demanding. . .an adequate response.”19 Hypermestra’s letter, while it does not save her from undeserved misery, is at least an act of self-expression that has the potential to survive her tragic demise.

It’s hard to see the Heroides as a concerted piece of proto-feminism, but not quite so hard to see Ovid’s epistolary collection as a modest step forward toward bringing the psychological experiences of women into literary history. Ovid’s heroines are a compromised, often disgraced lot who nonetheless refuse to be silent and fade away. One of Ovid’s near contemporaries was the historian Livy, whose women are far more likely to exit the stage hushed and outright murdered. In the story of the Oath of the Horatii, an unfortunate Roman girl has been engaged to one of Rome’s enemies. When she mourns his death, her Roman brother kills her with a knife, and the family patriarch emphasizes that the killing is justified (1.26). In Livy’s tale of the overthrow of the Roman monarchy, a chaste Roman matron named Lucretia is raped by the wicked prince Sextus Tarquinius, and thereafter kills herself out of shame (1.58).20 A similar yarn in Livy is the tale of Verginia, her father Virgilius, and the decemvir Appius Claudius. Appius Claudius wants to rape young Verginia, and her father murders her to protect her chastity (3.44-58). These stories of murders done to innocent Roman girls, written in the same decades Ovid was producing the Heroides, form a point of contrast to Ovid’s collection of fictional letters. Ovid’s heroines suffer all the indignities of abandonment and infidelity, familial and national betrayal, but they also form a broad kaleidoscope of distinct personalities, from the sad and helpless Hero to the toweringly enraged Medea. If Ovid is following a literary tradition in the Heroides, it is not Livy, but perhaps the lost work of a woman named Cornelia Gracchus. Cornelia, mother of Tiberius and Gaius Gracchus, was one of the paradigmatic icons of Roman womanhood, and her letters were still in circulation in Ovid’s day.21

Ultimately, whatever their roots, and whatever they told the median Roman reader about feminine experience, the Heroides are a literary creation, drawing from writers like Euripides, Apollonius of Rhodes, and Virgil – writers who did not shy away from the creation of psychologically complex heroines. The Heroides reveal a nascent desire to imagine a broad counter-narrative to the largely masculine world of ancient Mediterranean epic, and they may simply have been a literary experiment that allowed Ovid to inhabit female perspectives as he tried his hand at various genres in his twenties and thirties. Today, along with the Metamorphoses, the Heroides remains a valuable reference work on Greco-Roman mythology, with letters written not only by famous heroines, like Penelope and Dido, but also a small cast of characters seldom found elsewhere in ancient literature. [music]

Moving on to Ovid’s Didactic Love Poetry

I want to thank a few people for helping with this episode. To Professor Aven McMaster of Thorneloe University, thanks for your help editing this episode and several others on short Latin poetry. As delightful as the short poetry of Catullus, Horace, and Ovid is, it’s also rather challenging material, and Professor McMaster, who also hosts a podcast called The Endless Knot has helped me navigate a pretty dense period of literary history. Thanks again to Lantern Jack of the Ancient Greece Declassified podcast for recording the occasional Latin for me and for pronunciation help with every new program I’ve been releasing. And thanks also to listener Kevin Woodson for providing the album art for this episode. Kevin Woodson is a painter who enjoys listening to educational podcasts while he’s at work in the studio. Ovid is one of his favorite poets, and we decided that his painting Epic Garden, an Idyll of Flowers would be a great cover for this program on Ovid’s early works. You can see more of Kevin’s art at http://kevinwoodson.com/.Well, to return to Ovid, in considering Ovid’s early works, the Amores and the Heroides, we meet a writer who developed very quickly, and very early. By his mid twenties, Ovid already had a broad command of the Greco-Roman literature that had led up to him, together with the masterful technique and marvelous command of Latin that characterize his entire career. If he seems a trifle less grave than Virgil, and less inclined to autobiographical disclosures than Horace, perhaps Ovid’s levity and irreverence sprung from being the product of a later generation who spent more of its life under the peaceful reign of Augustus than the decades of the two triumvirates. Horace, however much he makes light of the issue, did fight in the civil wars, and he and Virgil both nearly lost their family properties and legacies to land seizures. No such threats confronted Ovid, however, and the Battle of Actium happened when Ovid was just twelve, and so in many ways the youngest Augustan Age poet was able to enjoy the prosperity of the early empire without having had to witness the bloodshed that engendered it.

Thomas Cole’s The Consumation of the Empire (1836). Ovid watched Augustus changed Rome from brick to marble. Most of his life was spent amidst a period of peace and prosperity that generations of Romans before him had not known.

Ovid’s Amores, which we spent the most amount of time with in this episode, were a definitive and final moment in Roman love poetry. From Catullus, to Catullus’ successor Cornelius Gallus, to Gallus’ successors Propertius and Tibullus, to Ovid himself, Latin love elegy evolved quickly over the course of two very different generations. We would perhaps expect to find the first and second centuries CE to be filled with elegiac sequences addressed to powerful dominas by poets who idolized them, but after the turn from BCE to CE, Latin poetry did not continue to chronicle courtships the way it had in the previous century. The reason for this, according to scholar E.J. Kenney, was largely Ovid himself. “After the Amores,” Kenney writes, “it was simply no longer possible to write love-elegy: Ovid had dealt the genre its death-blow.” And Kenney continues a moment later, “Ovid. . .finished off. . .love-elegy. He had not finished writing elegiac verse about love. In the Amores he had explored and mapped, tongue well in cheek and bucket of cold water at hand, the world of the elegiac lover-poet and, the exploration complete and the romantic mystery exploded, put the genre behind him, its literary usefulness exhausted.” It’s a testament to Ovid’s influence, and his vigor as a writer, that a set of poems he wrote in his early twenties ended up being the capstone volume of several generations of poets, a book that brought the love elegy form to a moment of climax and fermentation, and, in Latin, at least, ended the genre.

Not many writers write an epoch-breaking book with their first collection, and the Amores was only the beginning of Ovid’s remarkably robust contributions to literary history. In the next program, we’re going to look at some of Ovid’s didactic poetry. His Medicama Faciei, or “Women’s Facial Cosmetics,” is a comedic treatise on the application of makeup on Roman women. But far more influential than this text is the Ars Amatoria, or “Art of Love,” a full scale manual of seduction, explaining when, where, and how to get people to go to bed with you. Now it seems to me that if you’re standing in line in a grocery store – and I have the most experience with American grocery stores – if your eyes wander over to the magazine rack, whether you see a Men’s Health or a Cosmopolitan, you will see some sort of a glossy tagline that promises to reveal the secrets of seduction. You might see, “98 tricks to drive him wild in bed,” or “15 tips for first dates,” or “36 women reveal what they really want” or “112 ways to blow his mind in the bedroom.” Evidently, there is something about Americans that makes us want to learn how to seduce the opposite sex while we’re waiting in line to purchase tomatoes and fabric softener. Anyway, thousands of years before all of these periodicals, Ovid wrote history’s first surviving manual of sex and seduction, a long poem that is simultaneously filthy, funny, disturbing, and occasionally, weirdly astute and wise. So next time, we’ll look at Ovid’s three poems having to do with love and courtship, with Ars Amatoria being the inevitable centerpiece. And after Episode 60: How to Seduce a Roman, I can guarantee that if you ever go back in time and try to get laid in Augustan Age Rome, you’re going to stand a hell of a lot better chance. I have a quiz on this episode at literatureandhistory.com if you’re interested in seeing what you remember about Ovid’s life and his early works. Got a comedy song coming up if you want to hear it. If not, thanks for listening to Literature and History, and I’ll see you next time.

Still listening? Well honestly, it’s pretty tough to try and be funny, or clever, after an episode on Ovid. What I thought I’d do for this show’s final little flourish is to actually compose a song in elegiac couplets, filled with lines that sound like they could have been lifted from the Amores or the Ars Amatoria. It’s a moderately funny song, but I thought more than anything that it might be useful to students studying this subject for the first time on down the road. So this is a short one in waltz time, due to all the dactyls necessary – it’s called “Ovid in Elegiacs” – and it tries to capture the mischief, and churlishness, and fun of Ovidian love poetry. Hope you like it, and next time it’s going to get even steamier as we move into Ovid’s great manual of seduction, The Art of Love.

References

2.^ Ovid. Heroides and Amores. Translated by Grant Showerman. New York: The Macmillan Company, 1915, pp. 495, 7.

3.^ Hardie, Philip. “Introduction.” Printed in Hardie, Philip, ed. The Cambridge Companion to Ovid. Cambridge University Press, 2002, p. 1.

4.^ Ovid. The Poems of Exile. Translated and with an Introduction and Notes by Peter Green. University of California Press, 2005, pp. 79-80. Further references to this text noted parenthetically.

5.^ Tarrant, Richard. “Ovid and Ancient Literary History.” In Hardie, Philip, ed. The Cambridge Companion to Ovid. Cambridge University Press, 2002, p. 13.

6.^ See “Approaches to the Poet: Historical and Literary Sources of Ovid’s Vita” in Holzberg, Niklas. Ovid: The Poet and His Work. Cornell University Press, 2002, p. 21.

7.^ Quintilian. Delphi Complete Works of Quintilian. Delphi Classics, 2015. Kindle Edition, Location 11134.

8.^ Stephen Harrison writes that “Generic issues are foregrounded and contested right from the start of the Amores. 1.1 begins by repeating the first word of Virgil’s Aeneid, arma, ‘arms,’ creating the expectation of epic.” Printed in Harrison, Stephen. “Ovid and Genre: Evolutions of an Elegist.” In Hardie, Philip, ed.The Cambridge Companion to Ovid. Cambridge University Press, 2002, p. 80.

9.^ Kenney, E.J. “Introduction.” In Ovid. The Love Poems. Oxford University Press, 1998, p. xiv.

10.^ The relevant passages in Propertius are 2.15.1-6, 2.15.17-20 and connectedly 2.8.25-9 and 2.25.17-20.

12.^ Hardie, Philip. “Introduction.” Printed in Hardie, Philip, ed. The Cambridge Companion to Ovid. Cambridge University Press, 2002, p. 20.

13.^ It’s unlikely that any of Ovid’s marriages were undertaken due to mutual affection, but nonetheless the solitary lover figure he affects in Amores is ultimately the disingenuous fiction of a married man.

14.^ He retained this egocentric honesty toward the end of his life, writing to his third wife in Tr V.14.1-5, “How great a monument I’ve built you in my writings. . .as long / as I’m read, your legend and mine will be read together.” Quoted in Ovid. The Poems of Exile: Tristia and the Black Sea Letters. Translated and with an Introduction and Notes by Peter Green. University of California Press, 2005, p. 105.

15.^ It’s worth noting that Donne’s aubade may have been influenced by Ovid’s, and also acknowledge Donne’s sincerer version as a literary innovation of its own.

16.^ For the chronology see Ovid. Heroides. Translated with Introductions and Notes by Harold Isbell. Penguin Books, 1990, pp. xxiii-xxiv.

17.^ Ovid. Heroides. Translated and with Introductions and Notes by Harold Isbell. Penguin, 1990, pp. 183-4.

18.^ Sharrock, Alison. “Gender and Sexuality.” Printed in Hardie, Philip, ed. The Cambridge Companion to Ovid. Cambridge University Press, 2002, p. 95.

19.^ Kennedy, Duncan F. “Epistolarity: the Heroides.” Printed in Hardie, Philip, ed. The Cambridge Companion to Ovid. Cambridge University Press, 2002, p. 220.

20.^ Ovid tells this story in Fasti 2.685-852. Lucretia is certainly no ireful Medea, but Ovid does focus the story on Lucretia’s own terrible experiences.

21.^ See Pomeroy, Sarah. Goddesses, Whores, Wives, and Slaves: Women in Classical Antiquity. Schocken Books, 1975, p. 150.