Episode 62: A Curious Passion

Ovid’s Metamorphoses, Books 6-10. In the middle portion of Ovid’s great poem, psychological transformations become as gripping as physical ones.

| Read Transcription | References and Notes |

| Episode Quiz | Episode Song |

| Episode on Spotify | Episode on Apple Podcasts |

| Previous Show | Next Show |

Ovid’s Metamorphoses, Books 6-10

Hello, and welcome to Literature and History. Episode 62: A Curious Passion. This is the second of three episodes on the Metamorphoses, an enormous collection of Ancient Mediterranean myths dealing with transformation, completed by the Roman poet Ovid some time around 8 CE. More than any other work, Ovid’s Metamorphoses served as a window into antiquity for readers during the middle ages and early modern period. A constellation of famous writers relished Ovid’s versions of ancient myths, in part simply due to the massiveness of Ovid’s poem.With 12,000 lines and more than 250 seamlessly interconnected tales, the Metamorphoses is the omnibus of Ancient Mediterranean literature, and the summit of Golden Age Latin poetry. The collection embodies much of what characterized Roman literature up to Ovid’s time – a thoroughgoing familiarity with Greek poetry, a penchant for showy displays of erudition, an affection for careful craftsmanship, and an ambivalence toward long narrative epic. Virgil’s Aeneid is certainly Rome’s most famous story, but the Metamorphoses is a far more Roman work, with its emphasis on synthesis, inclusiveness, appropriation and rearrangement, rather than sheer originality. Ovid and the generation of poets that preceded him expected poets to double as scholars, and as scholars, they sought to collect and process centuries of texts that had come before them.

Last time, we heard dozens of myths from the first five books of the Metamorphoses – myths that took us from the chaos that preceded the creation of the world all the way up to a time when heroes began to figure prominently into events on earth. And in this program, we’ll hear more of Ovid’s stories about humans – humans often surprised to discover that everything in the world, including their bodies and identities, is subject to sudden change. The myths that you’ll hear through your speakers or headphones in this episode have been in continuous circulation for two thousand years, from the desks of early imperial readers, to the shelves of Byzantine storehouses and later medieval monasteries, the libraries of renaissance collectors, the canvases and sculptures of baroque galleries, the satchels of neoclassical poets, the secret nooks of Victorian mansions to the metal stacks of contemporary libraries. Toward the end of this program, we’ll talk a bit about the Metamorphoses as a whole, and whether any ideology governs the epic other than an omnipresent love for literature. But first, let’s enjoy these stories, beginning with the first tale in Book 6, and ending with the last tale in Book 10.

I’ll be using several translations for this episode, but unless otherwise noted, for books 6 and 7 I’m occasionally quoting from the Charles Martin translation, published by Norton in 2004, and for Books 8-10, the David Raeburn translation, published by Penguin Classics, also in 2004. And the opening stories that we’ll hear today relate to a theme – a very familiar theme if you know any Ancient Greek literature – the theme of human hubris, and gods who don’t take especially kindly toward it. [music]

The Metamorphoses, Book 6

The Story of Arachne and Minerva

The first story in Book 6 of the Metamorphoses is the tale of Arachne, a mortal girl famous for her weaving, whom Ovid describes as “a girl renowned not for her place of birth / nor for her family, but for her art” (VI.10-11).1 Nymphs would go to Arachne’s humble abode not only to observe her finished products, but to watch her work as well. And Ovid’s Arachne was a rather arrogant girl, proclaiming that she was every bit as good a weaver as Minerva herself.

Peter Paul Rubens’ Arachne (1636/7) shows that however hubristic Arachne is in Ovid’s Metamorphoses, Minerva’s jealousy and brutality are hardly any more appealing.

The goddess Minerva’s tapestry featured the Athenian Areopagus and the Olympians standing proudly around it. In the corners of Minerva’s tapestry were portraits of mortals who had been sufficiently unwise to challenge the deities in the past – mortals who had suffered mutilations and transformations in the past for doubting the primacy and power of the gods.

But Arachne’s tapestry was quite different. It featured perhaps a dozen tableaus of gods – but they were gods far different from Minerva’s proud and magisterial ones. Arachne wove portraits of gods raping and hurting human beings – Jupiter, in various disguises, raping defenseless girls, and Neptune and Apollo doing the same thing. Arachne’s creation was an ugly defamation of the Olympians and a vivid history of their worst crimes, and naturally, Minerva was not pleased. In one of the nastiest scenes in the Metamorphoses, Minerva, furious at Arachne’s success, smashed her weaving shuttle into Arachne’s face, strung her up from the ceiling, and, claiming that she was doing so for the sake of clemency, changed Arachne into a spider. [music]

The Story of Niobe and Latona

The news of Arachne’s awful demise spread all the Aegean world. Arachne had an acquaintance called Niobe, and Niobe was disgusted at Arachne’s fate. Like Arachne, Niobe also had a hard edge of pride. The source of Niobe’s pride was her great love for her children, whom she idolized above all else. Niobe was so proud of her family and her lineage that she disparaged people for making offers to gods – her children, after all, had divine blood in them through their father – and shouldn’t people make offerings to gods they could see, and not distant, far off ones?The goddess Leto, whom Ovid calls Latona, is at the source of Niobe’s criticisms. Latona only had two children – Diana and Apollo, whereas Niobe herself had fourteen – seven boys and seven girls! Niobe demanded that the worshippers of Latona stop their sacred rites.

News of this blasphemy reached Latona in the heavens, and Latona deployed her son Apollo to go and punish Niobe’s family for her hubris. In a series of short, gory vignettes, Apollo killed all of Niobe’s seven sons with arrows. Niobe then addressed the goddess Latona, saying that Latona had indeed wounded her deeply – but that she was still greater than Latona, because she still had seven daughters left. Niobe was – uh – clearly not particularly intelligent. Predictably, then, Niobe’s seven daughters, grieving for their seven murdered brothers, all dropped dead, the youngest dramatically dying in her mother’s arms. As for Niobe, the proud matriarch changed into a statue – a statue that was entirely motionless but for the tears that fell from its eyes forever after. [music]

The Story of Latona and the Peasants

Latona, the goddess who had enjoyed her vengeance on the proud matron Niobe, had not always been so powerful. Once, after she had become pregnant with Jupiter’s twins, Apollo and Diana, Latona had been banished from earth by the jealous Juno. Wandering widely, poor Latona came upon a pool of water. Latona was dreadfully thirsty, but when she went to drink, the peasants there spurned her by stirring the water up and causing mud and muck to rise to the surface. And Latona, not entirely powerless even at this point, cursed them all. She said that if they liked their precious mucky pond so much, they could stay there forever. And she changed them all into frogs. [music]The Story of Apollo and Marsyas

Arachne, Niobe, and the selfish peasants in the previous tales are all stories about humans unwisely disparaging deities, and Book 6 of the Metamorphoses continues on this theme with the tale a satyr called Marsyas. Marsyas had challenged Apollo to a contest of pipes, having lost the contest, Apollo skinned the poor satyr, and Ovid describes the skinless creature in horrific detail. The country people who knew the unfortunate Marsyas all wept for him – and they cried so profusely that their tears became a river in western Turkey.After briefly mentioning the tale of Pelops, served by his father as a meal to the gods and then reconstituted but for a chip of ivory along his shoulder, Ovid continues Book 6’s pattern of rather violent and tumultuous tales. And the next story is one of the more famous in the entire collection – Ovid’s narrative of Tereus, Procne, and Philomela – the longest version of this tale to survive from antiquity. [music]

The Story of Philomela, Procne, and Tereus

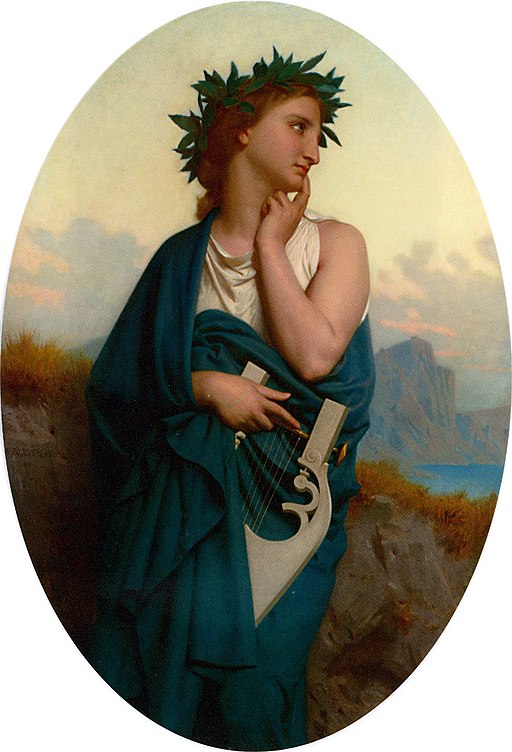

William-Adolphe Bouguereau’s Philomela (1861), one of the most memorable characters in the Metamorphoses.

The couple moved to Tereus’ homeland of Thrace, and had a son. Five years passed. Procne missed her sister, and wanted to see her. Procne’s sister, still living in Athens, was called Philomela. And so King Tereus was sent to Athens to pick up Philomela and take her up to Thrace to see her sister Procne. Upon arrival, Tereus was struck by his sister-in-law’s great beauty, and passion consumed him as quickly as fire rushes over dry leaves. King Tereus ran through the possibilities of how he might have sex with her – seduction? Bribing her maidens? Making war on Athens?

For the moment, Tereus stuck with the original plan. He was there, he told the king and princess Philomela, to take Philomela to visit her sister in Thrace. Everyone thought it was a perfectly natural arrangement. That night, a banquet was held, and Tereus couldn’t keep his eyes off of Philomela, watching her body and imagining her naked. The next morning, the Athenian king told Tereus to take care of his beloved daughter – he couldn’t wait to have her back, because having one daughter living abroad was already difficult enough.

When poor Philomela was finally aboard his boat, Tereus knew he had won what he wanted. He waited until they had reached Thrace, and then, Ovid writes, in the Norton Charles Martin translation,

Their journey done, the ship is brought to shore:

Tereus drags the daughter of the king

to an upland hut, deep in those ancient woods,

where pallid, trembling, utterly in terror,

she tearfully asks where her sister is;

he locks her in and openly admits

his shameful passion and his wicked plan,

then overwhelms the virgin all alone.

In vain she cries repeatedly for help

from father, sister, from the gods above.

And after he was done with her, she shuddered

like a young lamb, broken by an old grey wolf

and flung aside, who cannot yet believe

that she is safe; or like a wounded dove,

her plumage brightly stained with her own blood. (VI.746-59)

Unlike many of the rape victims in the Metamorphoses, Ovid’s Philomela doesn’t just go away or die after suffering an assault. She condemned Tereus for betraying her sister and her father. She said that everyone would know about his sick crime, from people to the highest gods. Tereus, however, revealed even deeper depths of wickedness. He unsheathed his sword and cut Philomela’s tongue out. And then he raped her again, even as her tongue still writhed on the floor of the remote shack.

Having committed these awful crimes, Tereus returned to his wife Procne. He told Procne a rehearsed story – Philomela had suffered a tragic death, he said, actually crying as he spoke – and Procne put on black clothing and built a tomb that no body would ever fill. Meanwhile, poor mutilated Philomela lived under guard in the remote hut. Though Philomela could no longer speak, she had plenty of time to think, and someone had given her a loom to pass her long hours of solitude. And with her loom she wove a portrait of the crime that had been committed against her, and she slipped this portrait to a slave boy.

Procne received the portrait and understood its import immediately. But like her sister, she was able to keep calm and collected in the face of dreadful calamity. Procne waited, and she thought of one thing: revenge. Procne waited until a festival of Bacchus, at which time Thracian women gathered to partake in the chaotic and wild rites of the god of wine. And during these wild celebrations, Procne broke into the hut where her sister was being held, recovered Philomela, and brought her back to the palace.

The two sisters embraced for a long time, Procne making it clear that they were mutual sufferers, and that they would not be parted again. While Philomela was mute, Procne could not control her rage. In one of my favorite lines in the Metamorphoses, Procne growled, “No weeping now – it is time for swords, / or for whatever else surpasses swords: / my sister, there is no abomination / that I am unprepared to undertake” (VI.884-7). They could burn Tereus alive, Procne said, or tear out his tongue or eyes, or slice off his penis. Yet Procne’s son came to her, then, and wrapped his little arms around his mother, and she knew what she would do.

The sisters took the child into a room deep in the palace basement. And they cut him to pieces. In a cauldron and grill, they made a broth and briskets out of his remains. Procne summoned her husband, then, for a meal – a special meal, she said, served directly to him by his wife, a custom of the Athenians. Tereus consented, and he ate plentifully, and, glutted by meat, he asked his wife to bring their son in to share in the occasion. Procne said he was already there. Tereus was puzzled. He asked again where his son was. And suddenly Philomela, who had been hidden, burst into his sight, still wet with blood and gore from the butchery of Tereus’ son, holding the little boy’s severed head. Tereus screamed – he invoked the furies – he wanted to vomit but could not, and he began chasing after the sisters. But he never caught them, because Procne changed into a swallow, and Tereus into a hoopoe. And Philomela, having been denied the power of speech in the last year of her life, transformed into a nightingale, thereafter able to sing her lamentation for all to hear.

Peter Paul Rubens Tereus Confronted with the Head of his Son (1636-8). There is a level of mutual horror on all three of the story’s main characters in this painting, as though the sisters are also sickened at the depths to which they’ve sunk. The figure watching from the rear doorway is particularly intriguing. The horror of the scene is – um – slightly undercut by the sisters’ inexplicable bare chests. In general, Renaissance painters imagined the fronts of female gowns to be exceedingly flimsy and unreliable.

And Ovid’s version of this story, by the way, was Shakespeare’s source for much of the plot of his play Titus Andronicus. [short music]The Story of Orithyia and Boreas

One more story closes the violent sixth book of the Metamorphoses. Procne and Philomela had a niece. Her name was Orithyia. And she was desired by the north wind, Boreas. Boreas knew that subtlety was not his strong point. His way was the way of force – to make war with the other winds in the vast dome of the sky until fires rose up from their collisions. Boreas abducted her and compelled her to marry him. And Orithyia later became the mother of the Boreads, or the powerful sons of the north wind. [music]The Metamorphoses, Book 7

The Story of Medea’s Concoctions

Good old Medea, cooking up some drugs, certainly made it into the Metamorphoses. Frederick Sandys’ Medea (1866-8) also features her trademark Colchian dragon (shadowed to the right), the Golden Fleece (upper right), and the Argo that took her on her fateful journey to Greece (upper left).

Ovid picks up Medea’s story at the moment when Jason is already in her kingdom, and has found herself in love with the western adventurer. Like Apollonious’ Medea, Ovid’s Medea cannot understand why she has been overcome with yearning for a stranger, and a dramatic monologue of about a hundred lines opens Book 7, in which Medea ruminates on her strange feelings and tries to determine what to do. Ovid then retells the story of how Medea helped Jason plow fields with fire breathing bulls, helped Jason sow serpents’ teeth into a field and fight off warriors that arose afterward, and then recover the Golden Fleece from the dragon that guarded it.

Ovid also tells of some parts of Medea’s adventures not covered by Euripides or Apollonius of Rhodes. Apollonius’ epic breaks off just before Jason and the Argonauts reach Jason’s homeland if Iolcus. Ovid describes what happened next.

Jason was happy to arrive back in his homeland, but he was depressed at the sight of his aging father Aeson. He wished that years of his life could be subtracted and added to his father’s. Medea explained that this was impossible, but said perhaps she could do something to prolong Aeson’s life. And that very same night, the ever-useful and industrious Medea got to work. Medea was the priestess of the goddess Hecate, the patron deity of magic, the nighttime, and crossroads, and so at dusk, Medea headed out to begin her ritual. Ovid’s description of her setting out is just terrific – he writes, in the A.D. Melville translation,

Medea, barefoot, her long robe unfastened,

Her hair upon her shoulders falling loose,

Went forth alone upon her roaming way,

In the deep stillness of the midnight hour.

Now men and birds and beasts in peace profound

Are lapped; no sound comes from the hedge; the leaves

Hang mute and still and all the dewy air

Is silent; nothing stirs; only the stars

Shimmer. Then to the stars she stretched her arms,

And thrice she turned about and thrice bedewed

Her locks with water, thrice a wailing cry

She gave, then kneeling on the stony ground,

‘O night’, she prayed, ‘Mother of mysteries,

And all ye golden stars who with the moon

Succeed the fires of day, and thou, divine

Three-formed Hecate, who knowest all

My enterprises and dost fortify

The arts of magic, and thou, kindly Earth,

Who dost for magic potent herbs provide;

Ye winds and airs, ye mountains, lakes and streams,

And all ye forest gods and gods of night, Be with me now!’ (VII.186-212)2

With a long prayer, Medea boarded her chariot, drawn by dragons. For nine days and nine nights Medea scoured the countryside for herbs and other ingredients. And when she returned, she began mixing them, combining the herbs with the blood of a sacrificed sheep, lukewarm milk, a goblet of honey, roots, sand, frost, the wings of an owl, the skin of a water snake, a stag’s liver, the head of a cow, and some werewolf guts. These, and countless other ingredients were combined in a great pot, and when Medea put a dead stick into the pot to stir it, the stick suddenly turned green and sprouted leaves, indicating that her efforts had been a success. The ailing Aeson, father of Jason, was then brought to Medea. Shockingly, she sliced old Aeson’s throat. Having drained him of blood, she replaced his blood with her concoction. And sure enough Aeson was restored to live in a younger version of himself, forty years having been taken off of his life. [short music]

The Story of Medea’s Later Life

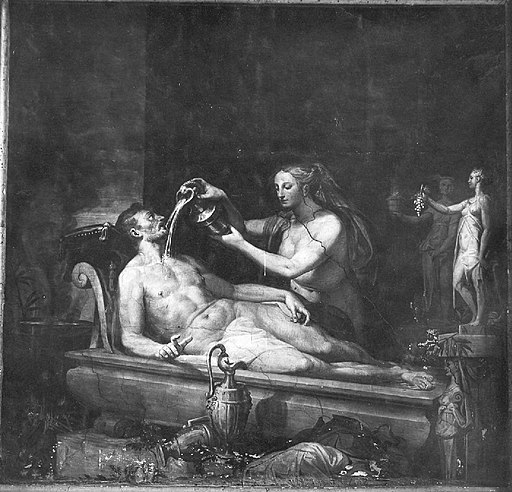

Pellegrino Tibaldi’s Medea Rejuvenating Aeson (16th century). Nothing like a ewer full of dubious sludge poured on your sternum to make you feel young again.

Naturally, King Pelias’ subjects wanted their ruler’s life preserved, and so they agreed to comply with Medea’s instructions. She told them that Pelias would first have to be drained of blood. And she made a different concoction this time – one that had no real power. After King Pelias’ daughters stabbed him, Medea slashed his throat and threw him into her cauldron. Not wishing to remain amidst the people she’d betrayed, Medea then hurried to her flying chariot and took off.

She flew widely and, some time later, wound up with her husband in Corinth. Corinth is where the events of Euripides’ play Medea take place – and Ovid retells these events quite speedily – Jason was too stupid to realize that he had the most powerful and loyal wife in the entire universe, he tried to marry a Corinthian princess, Medea killed the princess and her father, and then she killed the two sons she’d had with Jason. Next, Ovid’s Medea soared off to Athens.

She met with King Aegeus there, being first his refugee, and soon thereafter, his wife. And Queen Medea and King Aegeas were surprised when, some time after their marriage, a stranger arrived in Athens. His name was Theseus. He was the son of King Aegeus, but King Aegeus did not know this. And so thinking the strapping young man a threat to his power, King Aegeus consented to Medea’s offer to poison the young Theseus. Just as Theseus lifted his wine goblet to drink, however, King Aegeus noticed Theseus’ sword. Long ago, after a one night stand with a woman who lived across the Corinthian Isthmus, Aegeus had left a sword with her, beneath a large stone. He had told the woman that once their son was strong enough to lift the stone and recover the sword, he would be allowed to come to Aegeas as an heir. And so when Aegeus recognized his sword on the young man’s waist, he stopped his son from drinking the poison. The reunion between father and son caused the whole city to break out in celebration. [short music]

The Story of the King of Aegina and the Myrmidons

Not all was well in the city of Athens, however. Minos, the King of Crete, was leading a retaliatory expedition toward the city, for his son had been killed in an Athenian hunt. To make matters worse, the king of Aegina, an island just fifteen miles southwest of Athens, reported that an awful plague was ravaging his island, transforming even the healthiest animals into grotesque corpses. Even divination was impossible, because the guts of animals had all turned to fluid. The symptoms of the plague on humans were excruciating and hideous.The King of Aegina prayed to Jupiter for help. He saw ants carrying seeds to an oak tree, and prayed that all of his dead subjects would be replaced so that he would Aegina would have a citizenry to rule over again. And soon enough, the ants that had marched to the oak tree fell to the ground and transformed into people – people who were thereafter called the Myrmidons, Myrmidon coming from myrmex, the Greek word for ant. The Myrmidons would later be Achilles’ people in the Illiad, a group well known for their capacity as soldiers. [short music]

The Story of Cephalus, Procris, and the Magic Javelin

Athens, which has come up again and again throughout Book 7 of the Metamorphoses, continues to be a subject in the closing tale of the book, a story about a Greek prince called Cephalus. Cephalus had a magical javelin that struck any target at which it was thrown, and then boomeranged back into the hands of the person who threw it. Some new acquaintances asked Cephalus how he came to have such a magnificent weapon, and Cephalus was temporarily overcome with emotion.

Alexander Macco’s Cephalus and Procris (c. 1793). Sylvan scenes and landscapes featuring these two figures from the Metamorphoses show the tragedy taking place in a variety of natural settings.

Cephalus worried intensely that Procris had not been loyal to him while he’d been away. He did not return to her immediately. The dawn, Aurora, helped disguise Cephalus as another man. And while disguised as another man, Cephalus sought to test his wife’s fidelity. He courted her endlessly and tenaciously, offering her a fortune even just to spend a single night with him. Procris was steadfast, even though her husband had been missing for some time. However, when Procris finally hesitated, and seemed to consider one of her disguised husband’s offers of seduction, Cephalus erupted in rage.

Procris was ashamed. She left the city and joined the cult of Diana. As for Cephalus, he realized that he’d done his wife a terrible wrong. He went to her and apologized, telling her that he might have done the same thing in her circumstances, and the two were happily reconciled. Eventually, Procris gave him the magical javelin which had prompted him to tell his story. She also gave him a magical dog. The dog had been able to catch anything that it pursued, until it pursued a sly fox that could never be caught, and two of them turned to stone.

Notwithstanding the loss of his dog, Cephalus explained, he had been exceptionally happy with his wife Procris. He told his listeners of how he would hunt, and sing to the breeze, calling it “Aura,” just a nickname he’d come up with. Unluckily, however, someone heard him singing to the breeze, “Aura,” and a false rumor spread that he was having an affair with this Aura. Procris heard and was devastated. Procris never told her husband, and wasted away with grief. And more misfortune fell on the couple. Cephalus was out hunting. He heard a rustling sound in the bushes nearby, and flung his javelin at it. Tragically, the rustling noise was his wife Procris in the nearby foliage, and his javelin had pierced her breast. Her dying wish was that Aura, the woman she believed Cephalus was bedding, would not become his new wife. Cephalus was able to disabuse Procris of her jealousy and suspicions, and she died in his arms, content, at least, that she had not lost her husband to another woman. [music]

The Metamorphoses, Book 8

The Story of the Princess Scylla and King Minos

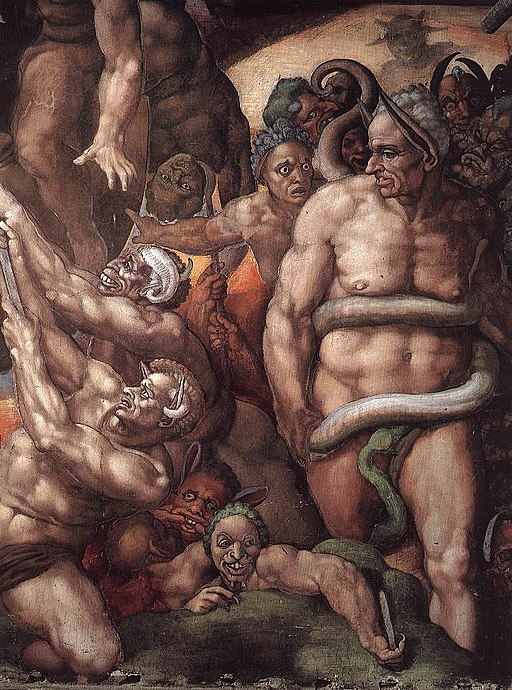

A detail of Michelangelo’s Last Judgment (1536-41) shows Minos condemned to damnation. Ever a fearsome figure, whether persecuting Athens or judging the damned in Dante’s Inferno, the story of Scylla and Minos introduces us to the Cretan King as an object of a princess’ romantic desire.

Scylla was the daughter of a king called Nisus. Scylla’s father eventually wound up in a full scale war against Minos of Crete, and Scylla would climb the towers of her city to watch the battles unfold. King Minos fascinated her. Though he was the enemy king, his strength and speed were breathtaking to behold, and she dreamt of becoming his hostage and thereby ending the war. They would wed, and her kingdom would be her dowry, and there would be no more fighting. It was just that escaping from her father’s citadel was a difficult affair.

There was one thing that could help her in her efforts. Her father had a magical lock of deep red colored hair, which was the source of his power, and the power of his kingdom. In an episode a bit like the Samson and Delilah story in the Book of Judges, Scylla stole into her father’s bedroom and cut his magical hair off. Absconding from her city, Scylla found King Minos and offered him the magic talisman.

Minos recoiled. He accepted the talisman, and conquered the city, but as for Scylla herself, Minos was disgusted. He wanted no part of her, he said. Crete would not be home to such a foul traitor.

Scylla, having sold out her kingdom for another kingdom that did not want her, was left alone with her rage. She excoriated King Minos – he was no son of a god, she said, but instead a wretch whose wife had cheated on him with a bull. She waded into the ocean and screamed at the shapes of the receding Cretan ships. Her father Nisus, who had changed into a falcon, drove his beak into her, and Scylla, too, transformed into a bird. [music]

The Story of Daedalus and Icarus

After besting his foes, including King Nisus and his daughter Scylla, King Minos returned to Crete. And in a compressed space of about thirty lines, Ovid retells the story of the labyrinth being built to house the minotaur, how the Cretan princess Ariadne helped the Athenian prince Theseus navigate the labyrinth and slay the minotaur, and then how Theseus abandoned Ariadne on the island of Naxos.Ovid pays considerably more attention to the story of Daedalus, the architect who had designed and constructed the labyrinth. Daedalus knew that Minos was the most powerful king in the Aegean, and that he would not be able to escape over land or sea. His only route away from the kingdom of Crete would be through the air. And so painstakingly, Daedalus used wax and feathers to create a giant pair of wings. Daedalus had a young son named Icarus, and Icarus was included in his father’s escape plan.

In an episode a bit like the one involving Phaëthon and Phoebus earlier in the Metamorphoses, Daedalus then told his son Icarus not to fly too high or too low. He cautioned the boy to follow him closely. At first their escape seemed as though it would go smoothly. A fisherman saw them, and then a shepherd, and then a plowman, and all three gawked at the sight of the soaring humans. Soon, though, Icarus became overzealous. In one of the most famous passages in the entire Metamorphoses, Ovid writes in the David Raeburn translation that,

[Icarus] ceased to follow his leader; he’d fallen in love with the sky,

and soared up higher and higher. The scorching rays of the sun

grew closer and softened the fragrant wax which fastened his plumage.

The wax dissolved; and as Icarus flapped his naked arms,

deprived of the wings which had caught the air that was buoying them upwards,

‘Father!’ he shouted, again and again. But the boy and his shouting

were drowned in the blue-green main which is called the Icárian Sea.

His unhappy father, no longer a father, called out, ‘Icarus!

Where are you, Icarus? Where on earth shall I find you? Icarus!’

he kept crying. And then he caught sight of the wings in the water.

Daedalus cursed the skill of his hands and buried his dear son’s

corpse in a grave. The land where he lies is known as Icária. (VIII.224-35)3

Ovid adds a short episode at the end of the tale of Daedalus and Icarus, in which a partridge reproaches Daedaus at his son’s grave. This partridge, we learn, is a boy that Daedalus once knew. Jealous of the boy’s ingenuity, Daedalus had thrown him off of the Athenian Acropolis. Conveniently, the boy had managed to transform into a bird halfway down. Daedalus, Ovid tells us, eventually wound up living in Sicily. [music]

The Story of Atalanta, Meleager, and the Calydonian Boar Hunt

Following the victory of Theseus over the minotaur, great celebrations were held in Athens. The Athenians, after all, had been forced to pay a tribute of seven youths per year to feed King Minos’ malformed son. With the creature dead, this annual tribute was annulled. However, all was not well on the Greek mainland. To the west, a giant boar with tusks as big as an elephant’s was laying waste to the countryside. The great Calydonian boar hunt is a common subject of Greco-Roman myths, and Ovid throws himself into telling an extensive version of it with characteristic zest and erudition.

Peter Paul Rubens’ Meleager and Atalanta (c. 1635). The pair’s most famous appearance in literature is in the Metamorphoses.

The boar initially steamrolled all attempts to wound it, its frightful charge leading Nestor to have to use his spear to vault up into a tree. First blood was drawn by the huntress Atalanta, and all of the males with her tried to explain away why they’d been beaten by a girl. One warrior, a braggart with a double-headed axe, said Atalanta had only wounded the boar, but that he’d finish the creature off. “My friends,” he announced, “let me show you how far the arms of a man outclass a mere woman’s. Leave this to me!” (VIII.392.3). For his braggadoccio, the man took a tusk to the groin and died almost immediately.

Ill luck and caution hindered other attempts to kill the monstrous boar. But finally, young Meleager was able to take it down with a timely throw. Hardly a chauvinist like the arrogant axeman, Meleager called to the huntress Atalanta and said she must share in the victory. He gave her gifts – the head of the boar and its skin. And obviously, now as well as then, nothing says love like the slimy, bristly hide of a freshly killed boar.

Some of the other men were not so comfortable with such great honors being given to a woman. They seized the skin and head from Atalanta. And things got ugly. Meleager was so angry that he killed his uncle.

Meleager’s mother, preparing her son’s victory feast, was devastated to hear that Meleager had murdered her brother. Meleager’s mother had a magical log, hidden away – a sort of voodoo doll log that she had been told was fated to have the same lifespan as her son. If the log burned, she knew, then young Meleager’s life would end. For a long time, Meleager’s mother debated to herself about what to do, but in the end she tossed the log into the fireplace.

Meleager felt scorching pain almost instantly, and he began to grow insubstantial until he drifted up into the air like ashes. The kingdom of Calydon reeled at the tragedy, and Meleager’s mother killed herself with a sword. Meleager’s sisters mourned his death, and the goddess Diana caused most of them to transform into birds. [music]

The Story of the River Achelous

The next story is comparatively more tranquil, containing no murder, suicide, groin impalements, or voodoo logs. Theseus and his friends were heading back to Athens from the Calydonian boar hunt, when they found their way barred by a river, Achelous. The river told them it was a bit swollen and perilous at the moment, but that they were welcome to enjoy shelter in a nearby cave until the rains subsided. The adventurers accepted the river Achelos’ offer, and while they ate and drank together, the river told them the history of some nearby islands. They had once been water nymphs, he said, but they’d changed into islands. One of the larger ones had once been his lover. The brief story was admittedly strange. In fact, one of Theseus’ friends remarked that gods couldn’t actually transform people. But one of Theseus’ other friends said of course they could, and he began the story of Baucis and Philemon, one of warmer and more beloved tales in the Metamorphoses. [short music]The Story of Baucis and Philemon

Jan van den Hoecke’s The Peasants Philemon and Baucis visited by Jupiter and Mercury (1640s). The moral of this story in the Metamorphoses is to offer hospitality to strangers, particularly if the strangers are shirtless and wearing shiny and unusual headgear.

The elderly couple said of course the travelers could come in. And with loving detail, Ovid describes the minutiae of their home – the low doorframe, the kindling used to start the fire, the cabbage, and bacon cooked, and the way a three legged stool was unlevel and had to be propped up with a piece of pottery. Baucis and Philemon went to the utmost efforts to make their guests comfortable, laying a cushion on their bench, warming water for the guests to wash with, and even rubbing the dinner table with fresh mint to create a pleasant odor.

The old couple did their best to lay a banquet for the travelers with what humble fare they had, and the result was a truly pleasant evening. Only, Baucis and Philemon noticed that their wine jar kept magically refilling itself. Worried that they had not given their absolute best to their guests, the old timers went to kill the single goose that they had, but they were too slow and feeble to catch it. Jupiter and Mercury then revealed themselves as gods, and told their old hosts that it was time for the whole town to be punished – the entire town, that is, except for Baucis and Philemon.

What happened next was considerably more spectacular than a fireside dinner. Jupiter flooded the entire settlement, and the only thing left standing was Baucis and Philemon’s home. Only, it had been transformed into a beautiful temple. Jupiter told the old folks that they were good, good people, and that he would like to grant them a wish. The couple discussed it. And the announced that they would like to serve as priests in the new temple there, and, when the time came for them to die, they would like to die at the same time, so that they would never have to live without one another.

Just as they had asked, for the rest of their lives Baucis and Philemon were priests at the temple of Jupiter. And when they passed away, they simultaneously transformed into two trees – an oak and a linden, trees which remain on that spot to this very day. [short music]

The Story of Erysichthon and Ceres

The final tale in Book 8 is the story of a king called Erysichthon. Erysichthon ruled in the east central part of the Greek mainland. He got into trouble with the gods when he cut down an enormous oak tree sacred to the goddess Ceres. Erysichthon was evidently a bit of a buffoon, because even though the tree grew pallid as he approached with his axe, and even though it bled when he chopped into it, and even though it spoke to him and told him he would suffer great horrors if he persisted in his efforts, Erysichthon chopped down the tree.The local wood nymphs mourned, and they went to Ceres to tell the goddess the news. Ceres was not pleased. She devised a punishment. Erysichthon, she decided, would suffer from eternal hunger. And in order to make this happen, Ceres sent an emissary to the spirit of Hunger, who dwelt in far off Scythia. Ovid’s description, in the Penguin David Raeburn translation, is very striking. Ovid writes,

The spirit [of Hunger] was plucking with nail and tooth at the scanty herbage.

Her hair was tangled, her eyes like hollows, complexion pallid,

her lips grimy and grey, her throat scabrous and scurfy.

Her skin was so hard and fleshless, the entrails were visible through it;

her shrunken bones protruded under her sagging loins;

her belly was merely an empty space; her pendulous breasts

appeared to be strung on nothing except the cage of her backbone;

her leanness had swollen all of her joints; the rounds of her knees

were bulbous; her ankles were grossly enlarged to a puffy excrescence. (VIII.800-8)

When Hunger was made aware of Ceres’ request, Hunger went to the palace of King Erysichthon, breathed onto his throat, and chest, and all over his mouth, and cursed him to be eternally famished, regardless of how much he ate.

When King Erysichthon awoke the next morning, he discovered that the more he ate, the hungrier he became. Food fed his hunger like flames feed a fire. Weeks passed, and Erysichthon ate so much that his kingdom’s resources became depleted. At last, Erysichthon only had his daughter left, and he sold her into slavery. The girl, whose name was Mestra, was understandably distraught.

She prayed to Neptune to take her life. She could not live as a slave, and so she hurled herself into the sea. However, Neptune stopped her descent and made her appear like a fisherman. The girl’s master, seeing a fisherman rather than his slave girl, was befuddled. He asked the fisherman if he had seen the slave girl he’d just purchased. And Mestra said she hadn’t seen anyone there at all. The slaveowner, having no reason to doubt the stranger, wandered off.

Mestra then found that she could transform into anything. For a time, her newfound ability funded her father’s last-ditch efforts to save himself from eternal hunger. King Erysichthon would sell his daughter Mestra to someone, and she would transform and escape, and he would sell her to someone else, and so on. But eventually, the king’s hunger grew too great to bear, and he ate himself. [short music]

The Metamorphoses, Book 9

The Story of Hercules and the Horn of Plenty

Hercules wrestles the river god Achelous in the form of a bull in Cornelis van Haarlem’s Hercules and Achelous in one of the Metamorphoses‘ many combat scenes.

Now Deïanira at that point was a hot commodity, being sought after by many suitors, including Hercules. All of her other suitors, seeing that the Hercules and the river god Achelous both sought Deïanira in marriage, dropped away, and it was thereafter a contest between Hercules and Achelous. Hercules said that he was the son of a god, and had completed his great labors. Achelous said that he was a god, and that Juno had never hated him the way she hated Hercules. Additionally, said the river god Achelous, Hercules wasn’t even the legitimate son of a marriage.

Hercules was not thrilled to be reminded of his sketchy parentage. He said he’d at least beat Achelous up, even if he lost their debate. They squared off for a bout. At first, the river Achelous had the upper hand, his truly enormous size thwarting Hercules’ best attempts to wrestle him to the ground. But eventually, Hercules wriggled around behind the river god Achelous and forced him to the ground. Achelous turned into a watery snake, but Hercules laughed and said he’d beaten a lot of snakes and serpents, and Hercules defeated Achelous in snake form. Then Hercules defeated Achelous when Achelous turned into a bull. Hercules snapped one of the horns off of the bull that Achelous had changed into, and this horn was filled with fruit and flowers. Finishing up the story of his defeat, the river god Achelous then brought out the broken horn before Theseus and his companions, explaining that the horn was filled with the spirit of plentitude, and this is Ovid’s origin story for a legendary Mediterranean artifact called the Cornucopia, or the horn of plenty. [short music]

The Story of Hercules Deïanira

So Hercules married Deïanira. And early in their marriage, they had an untoward run-in with a centaur called Nessus. On the way back home from his marriage, Hercules came to a swollen river. He knew he could swim across it, but worried that his new bride might be hurt in crossing the swiftly flowing water. The centaur Nessus appeared and offered to help – he’d carry Hercules’ wife right across, he said, and Hercules could swim.Hercules agreed, and paddled across to the other shore. When he climbed out, though, he saw that the centaur Nessus was galloping away with poor Deïanira. Hercules shot the centaur right through the torso with a poisonous arrow as it tried to escape. Dying, the centaur Nessus sopped up some of his poisoned blood in a tunic, and he promised Deïanira that the tunic would cause her groom to love her more deeply than ever when he put it on. And everyone knows that a dying centaur who has attempted to kidnap you, and whom your husband has just shot is entirely trustworthy when he hands you a bloody tunic.

In any case, Deïanira filed the bloody tunic away somewhere, and some years passed. Hercules became ever more famous, and as he was off conquering and murdering people, Deïanira heard a false rumor that Hercules had fallen in love with a foreign princess. Deïanira, distraught, considered her options, including cutting the foreign princess’ throat. But in the end, she remembered that the centaur Nessus had given her a mystical shirt that, according to the centaur’s words, at least, would make Hercules burn with passion for her.

An emissary delivered the shirt to Hercules, and when he put it on, he felt a burning sensation. The garment began eating away at his skin and muscles and tendons, and he screamed to Juno to just kill him and end his long agony and arduous life. He enumerated all of the twelve labors he’d completed. He saw the servant who had delivered the awful shirt to him and heaved the man into the sea, the servant turning to stone on the way there.

Strong even in the deep agony of his final moments of life, Hercules built his own funeral pyre, and even the gods looked on with awe. Jupiter promised them that although the mortal part of Hercules would indeed disintegrate, the immortal part of him would live on. And sure enough, with the mortal part of him burned away, Ovid writes that Jupiter “swept him up through the hollow / clouds in his four-horsed chariot, home to the glittering stars” (IX.271-2). [short music]

The Story of Hercules’ Birth and His Mother Alcmena

Hercules’ mother Alcmena was devastated at the death of her famous son, and the end of his difficult, tragic life. Alcmena recollected giving birth to the massive infant Hercules – he had certainly performed labors, but her labor had lasted seven agonizing days and nights. Now, Juno did not want Hercules to be born, and she prevented the goddess of childbirth, Lucina, from helping Alcmena give birth to Hercules. Sitting somewhere fairly close to where Alcmena was in labor, the goddess of childbirth Lucina kept her legs crossed and arms folded, symbolically preventing an easy birth.One of poor Alcmena’s crafty servants, however, saw what was afoot. Her name was Galanthis. Galanthis went to Lucina, goddess of childbirth, and congratulated her on Hercules being born, although the baby had not yet actually been born. Lucina was so stunned that she jumped up, uncrossing her arms and legs, and at that moment, Alcmena was able to give birth to Hercules and end her torment. Alcmena was naturally overjoyed. Her servant Galanthis was exultant, but the goddess of childbirth Lucina was enraged at having been fooled. Lucina thereafter changed the crafty servant Galanthis into a weasel, symbolizing her duplicity and deceit. [short music]

The Story of Dryope

Hercules’ mother Alcmena was sad that her servant had been changed into a weasel. I’m sure those of us who have had a trustworthy hireling suddenly transmogrify into a weasel can relate perfectly well. And indeed, one of Alcmena’s relatives, a granddaughter-in-law, offered her a comforting story about her sister, Dryope.Dryope, a lovely girl, had been raped by Apollo some time in the past. Though she’d lost her virginity out of wedlock, she’d found a husband and thereafter enjoyed a happy marriage. One day, while Dryope was out picking flowers with her baby, she was frightened to see that the flowers that she picked had begun to bleed from the stems. And, joining Daphne, Baucis, and Philemon, Dryope became one of a number of people in the Metamorphoses who transforms into a tree – a lotus tree.

This tree still had Dryope’s face, however, and the Dryope, now mostly tree, wept and said that she had done nothing wrong – certainly nothing to deserve her ugly transformation. She begged her relations to take her baby from her branches, and to bring him under her canopy to play and drink his milk. Additionally, Dryope asked that her baby son be taught never to pick a flower – ever, and that he be taught to assume that all bushes, shrubs, and hedges were the sacred abodes of deities. And after voicing these requests, Dryope finished transforming into a lotus tree.

Following the story of Dryope, Ovid includes a number of short tales concerning humans who have had their youth restored, and tells how the deities debated on whether mortals deserved such a favor, with Jupiter eventually asserting that such a thing was impermissible. [short music]

The Story of Byblis and Her Brother Caunus

The Metamorphoses so far has included all sorts of nasty crimes – rape, murder, torture, cannibalism, mutilation, and the like, and in the next tale introduces a relatively new theme: incest. In the eastern Aegean, there lived a pair of twins. The girl was called Byblis, and the boy was called Caunus. Byblis’ romantic feelings for her brother Caunus grew rather slowly. Ovid writes, in the Penguin David Raeburn translation, that,At first she did not understand the growing passion inside her.

She saw nothing wrong in kissing him on the lips rather often,

or tenderly throwing her arms round Caunus’ neck to caress it.

For long she deluded herself this feeling was perfectly natural;

but natural affection was slowly subverted. To visit her brother

she’d dress herself up and was over-keen to display her charms;

she was jealous of anyone else who was more attractive than she was. (IX.457-63)

As time passed, Byblis was compelled to admit to herself that she was in love with her brother. It could never be consummated, she thought, but she could at least allow herself to dream about it.

These resolutions, however, were slowly eroded by her torrid desire. Byblis thought of all the deities who had married one another, and who were siblings – Jupiter and Juno, the Ocean and Tethys. There were other examples of divine incest that she could call to mind, too, but then, different codes of conduct applied to gods and humans, didn’t they?

William-Adolphe Bouguereau’s Byblis. The painting shows Byblis just on the verge of her transformation into a mountain spring.

When her brother Caunus received the letter, he blanched with anger, and didn’t even finish reading it. He condemned the messenger, and the news of his vicious rejection reached Byblis. She became miserable. She should have tested out the waters first, she thought – she ought to have given hints. But she’d gone and put everything into one overweening and misguided attempt. If only she’d voiced her desires in person – she might have been able to convince him!

In the end, though Byblis was deeply wounded, she resolved to continue her efforts. She still thought that her story might have a happy ending. And the letter – sending the letter meant that Byblis had already crossed the point of no return. The only way was forward.

Yet in spite of unflagging persistence in her efforts to seduce her brother, Byblis was unsuccessful. Eventually, Caunus left their home city and founded a settlement further inland on the Anatolian land mass. His departure sent Byblis into a frenzy. She wandered all over the western part of modern day Turkey, finally collapsing on a mass of fallen leaves. Nymphs tried to console the heartbroken girl, and Byblis wept and wept, her tears sinking into the groundwater until she changed into a mountain spring, which, Ovid says, has remained there to this day. [short music]

The Story of Iphis and Ianthe

Around the same time that Byblis changed into a mountain spring, a baby was born under unusual circumstances. Before this baby was born, its father told his pregnant wife that he needed a boy at all costs – if the infant were a girl, she would have to be killed. The baby’s mother prayed and prayed, but when the baby was born it was indeed a girl. However, the baby’s mother and her nurse lied to everyone, saying that the child was male, and they named the child Iphis.Iphis, a girl who had to live as a boy, was engaged at the age of thirteen to a girl called Ianthe. They had known one another since childhood, having gone to the same school, and were in love with one another. Iphis, however, knew that her secret would soon prove a problem. As Ovid writes, in the Raeburn translation,

. . .Their innocent hearts

were aglow with similar fire, but their expectations were different.

Ianthe looked forward with joy to the wedding night they’d agreed on

and thought that the lover she took for a man was her man to be;

but Iphis loved without hope of ever enjoying her loved one,

which made her passion the stronger – a girl in love with a girl!

Almost in tears, she sighed: ‘Oh, what will become of me now?

I’m possessed by a love that no one has heard of, a new kind of passion. (IX.720-7)

Iphis brooded on the strangeness of her feelings, noting that cows never desired cows, nor mares mares. She compared her desire to that of Minos’ wife Pasiphaë, who’d lusted after a bull and produced the monstrous minotaur. She wondered if Daedalus, the great architect of the labyrinth, who’d been able to fly, might be able to change her into a man, or Ianthe into a man.

At least, Iphis said, she was still relatively free – it was just that at the end of the tunnel she could never expect to be with the woman she loved. Meanwhile Iphis’ mother, who knew her daughter’s secret, delayed and postponed the wedding again and again. When the occasion could be put off no longer, Iphis’ mother prayed for some kind of deliverance. And sure enough, Iphis was changed into a man. The wedding day dawned bright and sunny, and the couple were married. [music]

The Metamorphoses, Book 10

The Story of Orpheus and Eurydice

Ary Scheffer’s Orpheus Mourning the Death of Eurydice (1814). As much as we know about Orpheus, Eurydice is a mostly enigmatic character in the mythological record, including the Metamorphoses

Beginning Orpheus’ story, as he often does, in the middle of things, Ovid tells of how at the wedding of Orpheus and Eurydice, smoke from the customary wedding torches was drifting everywhere. Orpheus’ bride, taking a walk with her attendants, was bitten by a snake, and she died.

Orpheus, unprepared to lose the woman that he loved, went down into the underworld and spoke with Proserpina. The great musician explained his situation. He said that he had tried to bear the loss of his wife, but had been unable to do so. Mortals, Orpheus said, all ended up in the underworld at some point or other – what difference did it make if Eurydice got a bit more time above? And besides, Orpheus told Proserpina, if they wanted to keep Eurydice down below, he’d just stay there, too. Orpheus’ case wasn’t hurt by the beautiful music that he played while voicing his entreaty, and even the Furies broke into tears.

Pluto and Proserpine agreed to grant Orpheus’ wish. Eurydice was brought out, and the gods cautioned Orpheus that he could lead her up into the light, but only on the condition that he not look back. And so Orpheus led her upward and upward, until real daylight fell into one of the underworld’s exits. There, mortified that he had lost his beloved Eurydice, he looked back and saw her, breaking the vow that he’d made to the gods. She filled his vision only for a second, before suddenly being retracted back into the darkness and uttering one faint word – “Farewell.”

Losing his wife for a second time was even more dreadful for the great musician. Three years passed, and Orpheus shunned the company of women, no matter how many fell at his feet. In fact, Ovid tells us just before the end of the story in a cryptic trio of lines,

Orpheus even started the practice among the Thracian

tribes of turning for love to immature males and of plucking

the flower of a boy’s brief spring before he has come to his manhood. (X.83-5)

Whatever Orpheus’ sexual preferences were after losing his wife, one day, he was playing his lyre on a grassy plateau, his music so beautiful that he brought living trees to come and listen to him. One of these trees, the cypress, prompts the next tale in Book 10. [short music]

The Story of Cyparissus

Once, there was a boy called Cyparissus. The boy Cyparissus loved a stag – a famous animal with gold tipped horns, a jeweled collar, and a silver ornament on his forehead. Universally beloved on an island not far off the coast near Athens, the stag liked people and enjoyed making the rounds in the villages there. One day, Cyparissus accidentally speared his beloved stag, and he saw that the animal was dying. First Cyparissus wanted to die, and then he asked Apollo if, rather than dying, he might be allowed to mourn until the end of time. Cyparissus was changed into a cypress tree, which thereafter became the traditional tree associated with mourning in the Mediterranean world. [short music]The Story of Apollo and Hyacinthus

After this brief aside on the cypress tree – one of the many trees that came to hear Orpheus play, Orpheus began a song. And he said,. . .Let my song be of boys

whom the gods have loved and of girls who have been inspired to a frenzy

of lawless passion and paid the price for their lustful desires. (X.152-4)

First, Orpheus told the brief tale of how Jupiter once fell in love with an eastern Aegean boy named Ganymede. Jupiter changed into an eagle and kidnapped Ganymede, who later became Jupiter’s cupbearer. A similar short tale involves Apollo’s love for a Spartan boy named Hyacinthus. Apollo loved Hyacinthus desperately, following the boy all around the Peloponnesian countryside and helping Hyacinthus hunt. One day, Apollo and Hyacinthus stripped off their clothes, slicked themselves with oil, and had a discus throwing contest. One of Apollo’s discuses, tragically, ricocheted and struck Hyacinthus in the face, and in spite of Apollo’s best efforts, he couldn’t revive his lover. From the blood that had spilled from Hyacinthus there grew an extraordinarily beautiful and richly colored flower – the hyacinth. [short music]

The Story of Pygmalion and Galatea

After telling a very short yarn about some inhabitants of Cyprus who refused to honor Venus, and were turned to stone as a result, Orpheus turns to the story of a man called Pygmalion, who lived on the island of Cyprus and once saw their statues.Pygmalion was a sculptor, and he lived in a world of ideals. He did not want any real, mortal woman, and remained unmarried for a long time. Instead, Pygmalion fashioned a woman out of white marble, and worked on the statue so lengthily and carefully that finally, Pygmalion fell in love with it. He would run his hands all over it, and kiss it, and imagine that it was kissing him back. He whispered to it and brought it pretty shells and pebbles from the beach. He put clothing and jewelry on his statue, and became fond of calling the statue his mistress.

Venus was the patron deity of Cyprus, and the time of her festival had arrived. As sacrifices were made all around the island, Pygmalion voiced a solemn prayer that he would some day be able to marry a woman that looked like the statue he had created. Venus understood Pygmalion’s secret message, and a fire burning on Pygmalion’s altar flickered up three times. Breathlessly, Pygmalion went over to the statue. He kissed it, and thought he felt a faint warmth. He stroked its breasts, and gradually the stone turned to flesh. H realized she had come to life – she had veins, and a pulse, and she was soft, and real! As for the woman, who had come to life, she was initially bashful, but under the blessings of Venus, Pygmalion married the woman he had created, and soon they had a daughter.[short music]

The Story of Myrrha and Her Father

The next story in this sequence involves a girl called Myrrha, who was the granddaughter of Pygmalion and his living statue. And Ovid warns his reader here, that Myrrha’s is a gloomy tale – one hardly fit for fathers or daughters.Myrrha was a lovely girl, and she had many suitors in her homeland of Cyprus. But Myrrha had an affliction, an affliction not caused by an arrow from Venus, but instead, as Ovid tells it, from the viperous venom of the furies. Myrrha knew that her passion was perverse, and that it went against the laws of family and nature. But she could not change the fact that she was deeply in love with her own father.

Myrrha ruminated on it constantly. Animals, she reminded herself, coupled with their parents and children. She had heard of far off places where mothers could sleep with sons, and fathers with daughters. But she had not been born in such a place. And she could not, Myrrha resolved, betray her mother and her brother.

Her dark musings could not continue indefinitely. A small population of suitors were waiting to try and seek a marriage with her. Myrrha’s father came to her and asked which one she’d like to marry, and she said she wanted to marry the one most like him. He was touched, and told her she was a good, dutiful daughter. That night, Myrrha lay awake in torment. Here’s Ovid’s description of her feelings at this crucial juncture in the story, in the Norton Charles Martin translation this time:

[Myrrha]. . .lies tossing, consumed by

the fires of passion, repeating her prayers in a frenzy;

now she despairs, now she’ll attempt it; now she is shamefaced,

now eager: uncertain: What should she do now? She wavers,

just like a tree that the axe blade has girdled completely,

when only the last blow remains to be struck, and the woodsman

cannot predict the direction it’s going to fall in,

she, after so many blows to her spirit, now totters,

now leaning in one, and now in the other, direction,

nor is she able to find any rest from her passion

save but in death. (X.450-60)4

This is, by the way, one of a number of moments in the books we’ve read today in which Ovid takes a person suffering from an illicit desire and humanizes them, showing the mechanics of their interior psychology rather than preemptively condemning them, and we’ll talk a bit about that toward the close of this show.

Anyway, having decided that she was in an impossible situation, poor Myrrha prepared to hang herself, but her nurse stopped her from doing so. Myrrha’s nurse intuited that the girl was dying of passion, and volunteered her help. She said Myrrha was in love – and that she could facilitate the affair, and Myrrha’s father would never know! This, however, was no help to the distraught girl – quite the opposite, in fact. She told her nurse to get out, but her nurse determined to help at all costs, until eventually, the truth came out. Myrrha’s nurse realized that Myrrha was in love with her father.

The nurse tried to dissuade Myrrha, but her efforts were in vain, and at last the nurse said that it was better to live – to survive – as her father’s lover than to waste herself entirely in death.

Some time after this pivotal conversation took place, the festival of Ceres came to the island of Venus. Part of this festival was that wives would not be intimate with their husbands for nine nights. And during one of these nights, while Myrrha’s mother was out of the house and her father drunk, Myrrha’s nurse went to Myrrha’s father and said a young maiden – about his daughter’s age – desired him. After hesitating and delaying every step of the way, Myrrha was then led to her father’s darkened bedchamber. By the time morning came, she was pregnant with his child.

They repeated their transgression for the next two nights in a row, until Myrrha’s father brought a light in, and saw whom he’d been having sex with during his wife’s absence. He drew his sword immediately and prepared to kill her. But Myrrha fled. Over the next nine months she wandered and prepared to have the baby. She no longer knew what she wanted – neither life nor death suited her, and so she prayed for something in between. And sure enough, her toes suddenly sank down into the dirt and changed into roots, her blood turned to sap, her skin to bark, and her tears into droplets of liquid myrrh, as she had changed into a myrrh tree.

When the appointed time came, the tree split open, and out came a baby – an unexpectedly lovely boy, who would eventually be known as Adonis. [short music]

The Story of Venus and Adonis

Young Adonis grew from a healthy baby into a beautiful man. One day, as Cupid was embracing his mother Venus, one of his arrows accidently pricked her breast. And this arrow, soon enough, caused Venus to ignore all other matters on her home island of Cyprus, and to cling obsessively to the handsome young Adonis. Venus went everywhere with him, abandoning her customary routines of dressing carefully and manicuring her beauty, trekking after her beloved with her skirts hiked up.She only asked him to please be careful around more dangerous animals, as she could hardly bear to lose him. Particularly, said Venus, be careful around lions – creatures which she detested more than anything. Adonis, in the first flush of youth, was puzzled at the thought that he could ever be harmed, and he asked his lover why she hated lions so much. The couple settled down in the shade, and Venus began the second-to-last story in Book 10. [short music]

The Story of Atalanta and Hippomenes

There was once, Venus said, a woman called Atalanta. This is the same Atalanta who participated in the Calydonian boar hunt whom we heard about earlier – that powerful huntress whom no man had ever managed to marry. Atalanta was strong, and fast – so fast, in fact, that she told her throngs of suitors that she’d only marry the man who could outrun her. A bevy of men lined up to make the attempt. One, Hippomenes, was initially skeptical of all the dufuses lacing up their running sandals, but when he saw Atalanta, he suddenly understood. He knew that he had to have her. And he determined to win her at all costs. First, he watched her easily outrun a gaggle of suitors. Ovid offers a dazzling description of Atalanta in the race – this is the Raeburn translation:To [Hippomenes] she seemed to be running as fast as an arrow

fired from a Scythian archer’s bow, but her beauty astonished

Hippomenes even more; indeed her running enhanced it.

He saw the bright-coloured ribbons attached to her knees and her ankles

fluttering gaily behind her, while over her ivory shoulders

her hair streamed back in the wind. The white of her girlish skin

was all suffused with a rosy glow, as a marble hall

will be steeped by the sun in counterfeit shade through a purple awning. (X.588-96)

After Atalanta won, Hippomenes hurried forward and intrepidly challenged her, telling her he was a grandson of Poseidon. Atalanta was indeed impressed by the new competitor’s looks and dauntless courage. She said that if she ever did want a husband, and fate hadn’t ordained her obdurate chastity, she would have indeed considered him. But he had asked, and so he would have his race.

Hippomenes prayed to Venus. And Venus gave him three golden apples, and told him what to do during the race. When the trumpets sounded, then, Atalanta and Hippomenes took off, fast as light skittering over the surface of the ocean. Atalanta was reluctant to leave him – even his beautiful eyes slowed down her athletic efforts, but at last she pressed forward, and Hippomenes, out of breath, began to fall behind. That was when he heaved the first of his apples. Atalanta had to have it – she reeled off course to recover it. She soon caught up with her competitor, but a second golden apple slowed her again. When, just near the finish line, Hippomenes heaved the third golden apple, Atalanta hesitated, but Venus compelled her to go and recover it, and thus Hippomenes won the race, and the powerful huntress’ hand in marriage.

The story, however, did not have a happy ending. Venus, who is telling the story to Adonis, said that Hippomenes never thanked her for the help – no incense – no nothing. The newlywed couple stopped near a forested temple to make love in a cave. It was actually an ancient shrine to the goddess Cybele, and Cybele changed both of them into lions. And that, said Venus, was why she hated lions. She hated lions because another goddess had happened to arbitrarily change a man who had once wronged her into a lion. Whether in Homer, Virgil, or Ovid, the Venus whom we meet in ancient literature belongs in a white rubber room. [short music]

The Story of Venus and Adonis, Concluded

Having finished her story to her lover Adonis, Venus headed off to run an errand, leaving Adonis alone. Adonis went hunting a boar, and the creature managed to dislodge a spear thrown into it and drive its tusks into Adonis’ groin. Moments later, he was dead in a puddle of his own blood. Venus heard him die and came to the scene immediately. She tore at her dress and hair. She castigated the fates for their cruel whims. She said his tragic death would be honored in an annual festival. And from the deep crimson of Adonis’ blood there rose a fragile flower – the anemone, a blossom as beautiful, and with as tenuous a hold on life, as Adonis himself. And if the names of Venus and Adonis together as a pair sound familiar, that’s because Shakespeare’s first poem, Venus and Adonis, published in 1593, and likely the first piece of work the poet ever published, was based on the very story that you just heard. [music]The Metamorphoses and Authorial Intention

Well that was quite a dense little cluster of stories, and it takes us two thirds of the way through the Metamorphoses. Near the end of what we just finished, Ovid is telling the story of Orpheus telling the story of Venus telling the story of Atalanta. The long poem often proceeds in this way, with tales containing other tales and overlapping them, like a flower with petals that cover and overrun one another in every conceivable way. The Metamorphoses transforms constantly, multiple layers of narrators giving way to Ovid, who in turn weaves further layers of narrators into a seemingly inexhaustible patchwork of tales about transformation. Even hearing a summary of it in podcast form, as you have over these past two episodes, I think you have a pretty strong and accurate idea of how Ovid’s most famous book works. What I want to do now is talk a bit more about the poem as a whole, like we did last time.There is a fairly obscure word that I often find useful when thinking about texts like the Metamorphoses, and that word is “thetic.” Most simply it means, “pertaining to a thesis.” In the English classes that we take in high school and college, we’re taught to make a thesis statement, and then, thereafter, to move forward with points which support that thesis statement. Argumentative essays are thus expected to be thetic – to have a central assertion, and to seek to prove that assertion. And some literature is far more thetic than other literature.

Frontispiece to a 1478 manuscript of The Canterbury Tales. Ovid, Chaucer, and more generally the medieval miscellany culture share a desire to present a diversity of narrative material without advancing an overarching argument, staging variety shows rather than exhortations.

There is a central thetic element to the Metamorphoses that is quite obvious – Ovid is compiling an ocean of stories, picking out the bits related to transformation, and retelling these bits with panache. But beyond this research agenda, Ovid doesn’t particularly endorse or disparage any ideology, or individual, or organization. Perhaps, at best, we could say that cosmic impermanence is the central motif of the stories in the Metamorphoses, but as a thesis, cosmic impermanence readily undermines itself. In other words, if everything changes, then the fact that everything changes probably changes, too. And so because the Metamorphoses has such a slippery and self-annihilating thesis, we read the Metamorphoses as an imbricated series of stories that have common features, but not, particularly, a book with an argument. Ovid is happy to invite you into the many glass cases of his mythological museum, but as a guide, he’s content to say almost nothing and let you draw your own conclusions about what you see. His aim is to design the exhibits, and not to how to interpret the curiosities there.

Even the creation story that opens the Metamorphoses is casual and nonpartisan, rather than emphatic and dictatorial. The moment of creation in the Metamorphoses isn’t important so much because it springs from the directive of an authoritative deity, but instead because what came before creation was boring. Ovid describes the chaos that preceded creation as “a crude, unstructured mass, / nothing but weight without motion, a general conglomeration / of matter composed of disparate, incompatible elements” (I.7-9). Before creation, then, Ovid emphasizes, nothing was really going on. All of the interesting things that would eventually be whirling and evolving and metamorphosing were gummed together in a static block. But then something happened.

Book 1 of the Metamorphoses, like many other creation narratives from antiquity, tells of how the earth was initially created from the stasis that preceded it. Only, Ovid is pretty glib about who, exactly performed the miracle of creation. He writes, in the Raeburn translation,

When the god, whichever one of the gods, had divided the substance

of Chaos and ordered it thus in its different constituent members,

first, in order that earth should hang suspended in perfect

symmetrical balance, he moulded it into the shape of a great sphere. (I.31-4)

In other words, Ovid says, some god or other – let’s not sweat the details – made the earth. That is not, by any means, something that you hear in ancient Mediterranean creation narratives, many of which Ovid would have had access to. From the Babylonian tale of Apsu and Tiamat, to the Egyptian chronicle of Atum, to the Judahite one of Elohim or Yahweh, to Hesiod’s take, involving Gaia and Ouranos, when writers talked about the world being created in antiquity, they were pretty damned explicit about who did the creating, because that was largely the point of the narratives they were delivering. Ovid, however, perhaps because he lived in a more pluralistic society, and he actually knew that there were many creation narratives, throws up his hands and says he doesn’t know who, exactly, squished the earth into a sphere and got all the elements spinning around. And just sixty lines later, Ovid’s astonishing indifference to precise religious doctrine shows up again.

All of the cultures I mentioned above – the Babylonians, Egyptians, Judahites, the Archaic Greeks, and of course far more, had explanations of how humanity was created, and the standard theory was that at some point somebody scooped up some dirt, squashed it into humanoid figures and then worked some magic, and there we were. Ovid follows this story loosely, but again he’s unforgettably relaxed and evenhanded about the details. Ovid writes, in the Norton Charles Martin translation, “[N]ow man was born, / either because the framer of all things, / the fabricator of this better world, / created man out of his own divine / substance – or else because Prometheus / took up a clod. . . / and mixing it with water, molded it / into the shape of the gods, who govern all” (I.107-12,115-16). Ovid seems to have no impulse here to be doctrinal on the rather important story of how humankind was created. Instead, he tosses out a couple of alternate accounts, assumes one is as good as the other, and continues his saga.

Ovid’s creation story is thus unabashedly generic. He proposes no definitive explanation for which god actually made the earth, and presents alternate accounts of how humankind was made. His nonchalant attitude toward these all-important details seems peculiar, considering the confidently authoritative tones of the texts like the Theogony which he emulated. But in presenting multiple explanations for singular phenomena, Ovid was following a philosophical practice that, in the ancient world, was called pleonachos tropos, or “multiplicity of explanations.” Scholar Pramit Chaudhuri defines pleonachos tropos as “a practice. . .according to which a writer offers multiple plausible explanations for phenomena while remaining agnostic about the correct one.”5 And if Ovid were transported to the twenty-first century, and he applied pleonachos tropos to our creation stories today, he might say, “Some of these folks say that the world was created through a series of astronomical collisions stemming from a general outward moving expansion of cosmic debris. Others say that some sort of anthropomorphic deity or deities did it. I don’t know which is correct, folks; anyway, let’s move on.” So, pleonachos tropos, or again the “multiplicity of explanations,” is essentially a means of acknowledging multiple traditions and politely tipping a hat to all of them without identifying any of them as correct. Throughout the Metamorphoses, Ovid is happy to entertain multiple narrative traditions, admitting that although he’s told a story a certain way, others have told it another way. In the million-citizen-strong metropolis of Augustan Rome, one of the most theologically and intellectually diverse places and times in history, it was particularly uncouth to offer a single account of something without acknowledging that many other accounts were out there. [music]

Physical and Psychological Transformations in the Metamorphoses

In our analysis of the Metamorphoses thus far, last time we talked about the ancient compilations and doctrines that may have fed into Ovid’s most famous poem. And this time, we’ve discussed how in his initial creation narrative, Ovid creates something quite different than any of the creation stories we’ve seen so far – an account that’s brisk and casually inconclusive; that rehearses some standard elements and seems to think that one explanation is as good as another. What we haven’t done yet is look at any of the stories very closely. What I’d like to do now is pick a few out for some extra consideration – three stories with common themes that I think show Ovid at his most brilliant, right in the heart of the Metamorphoses.

A 1493 German woodcut of Ovid. The poet’s nonpartisan religiosity and general suspension of judgement on characters’ actions has helped the Metamorphoses‘ popularity along through some very different centuries.

One of the more memorable tales in the Metamorphoses is that of Myrrha, which we spent some time with earlier. Myrrha was that girl who fell in love with her father, ended up having sex with him with aid from her nurse, was exiled as a result, turned into a myrrh tree, and gave birth to baby Adonis. Ovid begins Myrrha’s story with lines that sound like a picaresque novel, or execution pamphlet. He warns the reader,

It’s a shocking story. Daughters and fathers, I strongly advise you

to shut your ears! Or, if you cannot resist my poems,

at least you mustn’t believe this story or take it for fact.

If you do believe it, then also believe that the crime was punished. (X.300-3)

These lines sound like they are introducing quite a condemnatory story – one in which perverse and twisted crime will be committed, and the criminal sentenced to dire suffering. And while this is indeed the form of the story that ensues, Ovid’s tale of Myrrha’s deviant passion is hardly a cut and dry narrative about a depraved villain.