Episode 64: Ovid’s Exile

For mysterious reasons, in 8 CE, Ovid was exiled from Rome. Ovid’s last works were composed an ocean away from Italy, on the western shore of the Black Sea.

| Read Transcription | References and Notes |

| Episode Quiz | Episode Song |

| Episode on Spotify | Episode on Apple Podcasts |

| Previous Show | Next Show |

Ovid’s Exile: Tristia and Epistulae Ex Ponto

Hello, and welcome to Literature and History. Episode 64: Ovid’s Exile. This episode is on two of Ovid’s late works, the Tristia, and the Letters from the Black Sea, written between 9-13 CE on the east coast of modern day Romania.1 While not nearly as famous as Ovid’s Metamorphoses or Art of Love, his late works have maintained a steady popularity in the past two thousand years. Exiled from Rome in 8 CE by Augustus himself, Ovid wrote bitterly about missing the capital, and petitioned his friends and family to help him return. The 96 poems that make up these two late works show Ovid running the gamut between despair and optimism – between dismal lamentations about the strange northern land of his exile, and idyllic fantasies about an imminent return to his home city.We’ll talk quite a bit about the historical circumstances of Ovid’s exile, and the contents of his later poems in a minute. I think maybe the best way to get an introductory sense of the overall tone and contents of Ovid’s exilic poetry is to hear a long excerpt from one of his later Letters from the Black Sea, written when the poet was in his mid-fifties, almost a thousand miles northeast of Rome, in the recently conquered province of Moesia.

O [Black] sea. . .O land never free from cruel enemies and snows, will a time ever come when I. . .shall leave you, bidden to an exile in a place less hostile? Or must I ever live in such a barbaric land, am I destined to be laid in my grave in the soil of Tomis? With peace from [you] – if any peace [you have] – O land of Pontus, ever trodden by the swift horses of a neighboring foe, – with peace from [you] would I say: [you are] the worst element in my hard exile, [you] increase the weight of my misfortunes. [You] neither [feel] spring girt with wreaths of flowers nor [behold] the reaper’s naked bodies; to [you] autumn extends no clusters of grapes; but all seasons are in the grip of excessive cold. [You hold] the flood ice-bound, and in the sea the fishes often swim in water enclosed beneath a roof. [You have] no springs except those almost of sea water; quaff them, and doubt whether thirst is allayed or increased. Seldom is there a tree – and that unproductive – rising in the open fields, and the land is but the sea in another guise. No note is there of any bird save such as remote in the forests drink the brackish water with raucous throat. Bitter wormwood bristles throughout the empty plains, a crop suited in harshness to its site. Add fears too – the wall assailed by the enemy, the darts soaked in death-dealing corruption, the distance of this spot from all traffic, to which none can penetrate in safety either on foot or by boat. (Ep III.1.1-28)2

Tomis in Augustan Age Roman Literature

The place of Ovid’s exile was a settlement called Tomis, now present day Constanța, Romania, a small city with the Black Sea to its east and the Danube about thirty miles to the west, situated on a fertile coastal flatland that juts out a hundred miles east of the Carpathian Mountains. Even before his exile to Tomis, Ovid might have read about the remote northeastern regions of Augustan Rome. Tomis was not, like Corsica, or Crete, or the Greek mainland, a place where exiles were sent for a temporary referendum. In scholar Emily Wilson’s words, “A ruler could modulate the expression of his rage by his choice of geographical location for the exile.”3 Tomis was where exiles were sent to be forgotten. For Ovid, the urbane epitome of metropolitan Rome, banishment to Tomis confronted him with the polar opposite of everything he knew and loved.Ovid’s predecessor Virgil, in the third Georgic, wrote of western shores of the Black Sea, and Ovid might have read these very lines in his youth, far before his exile. In the Penguin Kimberly Johnson translation of Virgil’s Georgics, Virgil imagines life in the distant northeast:

How different there, where Scythian tribes [lie],

and tousled the Danube spins its golden sands. . .

There penned in stalls they keep their herds, and no

green shows upon the steppe nor leaves in the trees,

but wide the earth slumps lumpen under mounds of snow

and mounts in deep ice seven cubits high.

Always winter, always the frosty wheezing of the northwind.

And the sun never dissipates the pale haze. . .

Sudden ice crusts cluster upon the brisk beck

and soon the water hefts the iron-clad wheel on its back –

once ships, now bulky wagons welcoming.

Brass buckles everywhere, clothes freeze

upon the back, they chop with hatchets their liquid wine,

whole ponds into solid ice transform,

and the jagged icicle glazes upon the uncombed beard. . .

[T]he Scythians hunt not with hounds unleashed, nor any snares. . .

The men themselves, in dug-out caves carefree and deep in earth

enjoy peace, rolling to the firepit whole elms,

heaped up trunks, committing them to the blaze.

Here they spool out the night with play, and merry they pretend

cups of wine by barming sour service-berries.

Such is this race of men unbridled, Hyperborean, pitched

beneath the Bear’s seven stars, buffeted by. . .easterlies,

their bodies bundled in the tawny pelts of beasts. (Geo III.349-50,52-7,60-6,71,76-83)4

Ovid’s impressions of the land of his exile, Tomis, and the territories around it are similar. A thousand miles northeast of Rome, Virgil’s successor found the land of his exile to be frigid, uncivilized, and perhaps worst of all, teeming with hostile natives always seemingly on the verge of breaking through the city walls. Ovid describes the tribesmen of the eastern Danube frequently throughout his exilic poetry, but maybe one image in the fifth book of the Tristia lingers most in one’s imagination after one finishes reading the poem. Thinking of the tribes who lived in the rugged interior portions of modern day Romania and Bulgaria, Ovid writes,

The horde descends, like birds, when you least expect it,

and, barely glimpsed, is away again with its spoils.

Often inside the walls, gates shut, their poisoned arrows

still reach us: we collect them off the streets.

Few dare to farm: the wretches that plough their holdings

Must do it one-handed (the other grasps a sword). (Tr V.10.19-24)5

The image of the lonely farmer, in the precarious and gloomy fringes of the Roman world, a sword in one hand and a plow in the other, encapsulates the way Ovid presents himself throughout his late poetry. Somewhere on the cusp between civilization and barbarity, the poet depicts himself as a man who undertakes literary work in spite of the perils and the benighted squalor around him. Rome, in Ovid’s late works, is the shining city of divine Augustus, where public processions and civic ceremonies dazzle the eye with warmth and color, and where literature and intellectual friendships all thrive. Tomis is something else altogether – an impossibly remote purgatory, a place of “human heads. . .employed as grisly offerings [and] acres of sea. . .turned to ice” (Ep IV.9.84,86), of cannibals (Tr IV.4.55-65) and murky plains and unending winter.

Tomis (upper right) was about as far away as an exile could be sent without actually being banished from the empire altogether, and the remoteness of Ovid’s exile evinces the extent of Augustus’ dissatisfaction with him.

Ovid’s impressions of the culture of Tomis were as negative as his impressions of the ecology, agriculture, and climate there. The seaside plain on which the settlement sat, according to Ovid, was flat, gray, and barren of vegetation. Worse than anything, it was cold in Tomis, with freezing winds and snow an annual reality, unlike in Ovid’s balmy Rome. The climate and unfamiliar culture of the settlement were deleterious to his health – Ovid’s late works make frequent references to various physical discomforts he suffered in exile.

The story that Ovid tells in his exilic poetry is a vivid mosaic of impressions, first through the anonymously addressed pieces in the Tristia, and then in the correspondence that makes up the Letters from the Black Sea. But Ovid’s exilic poetry is also full of mysteries. Most famously, the poet is ambiguous about the circumstances of his exile. He writes “It was two offences undid me, a poem and an error” (Tr II.207), and while he makes explicit that the poem was the Art of Love, his earlier seduction manual (see, for instance, Tr I.9.61-4, Tr III.14.6, Ep II.9.73-6, Ep II.10.11-13, Ep II.11.1-2), the error – or the actual crime against Augustus, remains unknown. Various theories about the error have been advanced, and we’ll talk about them a bit later. But perhaps an even greater puzzle about Ovid’s exilic poetry is its overall reliability. Much of the Tristia and the Letters from the Black Sea have a specific agenda behind them – to put it very simply, to convince friends, family, and powerful officials back in Rome to secure the poet’s return to his homeland, or at least to find him a more pleasant place of exile. Because so much of Ovid’s late poetry is written with an overall rhetoric of persuasion, readers have wondered how much he exaggerated his privations in Tomis. Was the settlement really a frozen wasteland, where tribespeople had ice in their beards and raiders harried guard towers with poisoned arrows? Was Tomis far beyond the pale of Greco-Roman civilization, or was Ovid able to keep company with an established Greek-speaking culture that had existed there since around 500 BCE?6 In a sentence, is Ovid’s late work the emotionally honest record of a heartbroken outcast, or is it a self conscious literary creation designed to garner attention for an aging poet?

The deeper we read the Tristia and the Letters from the Black Sea, the more we’re conscious of the mysteries of these texts. By the end of this episode, I hope to have given you an overview of the contents of Ovid’s principle late works, and a sense of some of the scholarly questions that still surround them today. But since we’re just getting started, let’s talk about the more basic historical background of the Tristia and Letters from the Black Sea. Through Cicero, Horace, Virgil, and Propertius, we’ve heard about the rise and ascendancy of Augustus. Through Ovid, we can learn about the twilight of Rome’s first emperor. [music]

The Diminishing Dynastic Hopes of Augustus

The background of Ovid’s exile begins about twenty years before it took place, when the poet was writing salacious poetry, neck deep in the high society of Rome. In 11 BCE, while managing a long campaign in the northern expanses of the Danube River in modern day Germany, Augustus’ right hand man Agrippa died. Agrippa was fifty-one years old, and already the father of four of the emperor’s grandchildren. It was a bitter moment for Augustus. Agrippa had been at his side through the emperor’s most perilous years, and had helped Augustus build Rome just as much as he had helped steer the emperor into absolute power decades earlier. Yet it was not an altogether devastating loss. In 12 BCE, the 58-year-old Augustus had a number of potential heirs, some of whom were the very sons of his recently departed friend Agrippa.

Lucius Caesar’s death in 2 CE was a huge blow to Augustus’ dynastic ambitions, and closely on its heels there followed the death of Lucius’ brother Gauis. Losing these two adopted grandsons after exiling their mother threw Augustus’ later years into deep and unexpected shade. Photo by the Fondazione Sorgente Group , ph. Luca Fazzolari.

Attending the funeral of his friend Agrippa in 11 BCE, Augustus surely felt wracked with uncertainty about the departure of such a stable partner. But with three biological grandsons, two stepsons, granddaughters, and a daughter who was only twenty-seven, and could be married again to produce more heirs, Augustus must have still seen a promising future on the horizon for his dynasty. He was in his late fifties, and if he continued to play his cards right, he would be able to set his best and brightest heirs up for a lasting sovereignty over the newly-made empire.

As the next ten years unfolded, however, Augustus’ hopes for his biological heirs were crushed by a series of familial calamities, some of them, unfortunately, of his own making. In 11 BCE, the same year that his best friend and son-in-law Agrippa died, Augustus compelled his daughter Julia to remarry – this time, to his stepson Tiberius, the future emperor. Tiberius was happily married at the time, and neither Tiberius nor Julia loved one another, nor wanted to marry. Bowing to the emperor’s wishes for a fecundity of legitimate offspring, however, Tiberius and Julia were wed. The marriage sputtered out after half a decade. Tiberius went to Rhodes, and Julia began, or had already begun a famous series of affairs with Romans of various stamps, including high profile patricians like Sempronius Gracchus and Iullus Antonius, scandalously, the son of Augustus’ one time rival, Mark Antony. Augustus, who had once passed legislation punishing marital infidelity and rewarding Romans who sought monogamous, child-bearing unions, heard increasing rumors between 6 and 2 BCE about his daughter’s sexual license. As Ovid worked on the third book of the Ars Amatoria and the Remedia Amoris, his great poems about the art of seduction, Julia enjoyed a series of affairs with all the unabashed zest that Ovid exhorted in his love poems.7

Even before Julia’s highly public affairs disgraced Augustus and his socially conservative agenda, Augustus had already experienced one major loss. His younger stepson, Drusus, the spearhead of many campaigns east of the Rhine River, died in 9 BCE after falling from his horse. Father of the future emperor Claudius, grandfather of Caligula, and great-grandfather of Nero, Drusus would contribute a formative legacy to the early empire, but Augustus didn’t know it at the time. The decade between 10 BCE and 0 CE saw Augustus reeling from the death of Drusus in 9 BCE and the massacre of the Teutoburg Forest that same year, coming to grips with his daughter’s sexual escapades, and finally, in 2 BCE, having Julia arrested for adultery and exiling her to the tiny island of Pandateria, about forty miles west of the city of Naples. If he hoped for reprieve from familial disaster in the next decade, however, Augustus got quite the opposite.

In 2 CE, the emperor’s biological grandson and adopted son Lucius Caesar died at about the age of 19 of a sudden illness. In 4 CE, his other biological grandson slash adopted son, Gaius Caesar, wounded after a series of successful campaigns in the east, also died. He had lived to 23, and been the emperor’s primary hope for a successful power transition. Augustus scrambled to act. One final son of his scandalized daughter Julia and his greatest general Agrippa remained alive, Agrippa Postumus. And in 4 CE, Augustus adopted both Agrippa Posthumus, along with Augustus’ remaining stepson Tiberius, as his heirs. Posthumus, however, at least as the ancient historians tell it, was intemperate, and perhaps even mentally unstable.8 It’s also possible that Augustus’ wife wanted Tiberius to be the future emperor, and thus plotted against the emperor’s biological grandson. Whatever the reason, Augustus exiled Postumus in 7 CE. Out of his once plentiful crop of biological heirs and eligible adoptees, Augustus was left with a single, chancy, reluctant successor – his 49-year old step son, Tiberius.

Tiberius had abdicated his public responsibilities and moved to the island of Rhodes in 6 BCE. He had been forced to divorce his beloved first wife and marry Augustus’ daughter Julia, who had flaunted her wide-ranging infidelity and publicly humiliated him. Neither a fool nor a ne’er-do-well, like some of Augustus’ other potential successors, Tiberius knew that he’d been put on the back burner by the emperor. And in 7 CE, even though Augustus was the most powerful person in the Mediterranean world, the 70-year-old emperor found himself scrambling to try and secure a stable succession through Tiberius.

This is the point at which we need to bring Ovid into the story. Because in 8 CE, Ovid himself was exiled by Augustus, later recording that “It was two offences undid me, a poem and an error.” The poem, as I said before, was in all likelihood The Art of Love, or Ars Amatoria, that text telling Roman men and women how to find and enjoy recreational sex in the city.9 As scholars Anne and Peter Wiseman write,

High society and the world of entertainment feed off each other. Both [Augustus’ daughter] Julia and Ovid, in their different ways, were the stars of the beau monde. It is not known exactly when the Art of Love was published, but it must have been quite close to the cataclysmic moment in 2 BC when Augustus finally understood what sort of life his daughter was leading and in fury banished her to the island of Pandataria; her lovers were executed or exiled, as if for treason. Witty, sophisticated Ovid, the playboy poet of Venus, was living on borrowed time.10

A 1644 printing of the Ars Amatoria. This book was written and published in reckless abandon of Augustus’ conservative legislation governing family relations, becoming popular just as Augustus’ own family was falling apart. It could not have endeared Ovid to the emperor.

We have heard, in recent episodes, several Augustan Age poets envisioning Augustus and the early principate as a sort of glorious end of all history. Horace told this story. Virgil, in the Eclogues, Georgics, and especially Book 6 of the Aeneid, praised Augustus as the summit of nearly 1,200 years of history that had begun with Aeneas fleeing Rome. And Ovid himself, albeit with a few subtle quips we looked at last time in the Metamorphoses, wrote of Augustus’ ascension as an event to cap off the mythological heritage of the ancient Mediterranean. When Virgil died in 19 BCE, the notion that Augustus was the capstone of Roman history may well have still seemed plausible. The emperor was at that point in his mid-forties, and had a growing brood of viable heirs. But in 8 CE, Augustus was 71, his pool of potential successors was empty but for Tiberius, and he must have looked back on the dissipations and the exile of his daughter Julia as an especially dreadful turning point in his family history. The great story that Virgil told – that Augustus was the apogee of the Mediterranean world, began to appear increasingly full of holes. Augustus had proved an adept leader, decade after decade. But what was next?

8 CE was thus a period of diminished dynastic hopes and general retrospection for the emperor, and in spite of Ovid’s turn to less controversial literary topics, Augustus banished him to the far northeast. The poet was 51 years old. He may have committed some recent infraction against the emperor. But even if there were no court intrigue, no sex scandal with an Augustan relative, or any other recent offense against the emperor, Ovid’s older love poetry might have seemed just cause for Augustus to exile him. The aging emperor’s vision of Rome had included stalwart, dutiful citizens who produced bushels of healthy children, not libertines and flâneurs whose reputations were built on sex manuals. And so in 8 CE, having finished the Metamorphoses and half of the Fasti partly in an attempt to broaden his thus far impertinent corpus of works, Ovid was forced to leave Rome, and settle in Tomis, a settlement only recently integrated into the empire that lay in the hinterlands of the Roman world. To begin talking about Ovid’s exilic poetry, I think we should start by talking about Tomis – what we know about it from the archaeological record, and what we can learn about the ancient settlement from Ovid himself. I’ll be quoting a number of passages from Ovid’s late poetry, and unless otherwise noted, quotes come from the Peter Green translation in a volume called The Poems of Exile, published by the University of California Press in 2005. [music]

Tomis: The Dark Muse of Ovid’s Later Years

Tomis, or modern day Constanța, Romania, was, as far as Augustus was concerned, an ideal place to exile a man who had disparaged Roman conservatism so energetically. As scholar Peter Green writes,Now the poet who had mocked the moral and imperial aspirations of the Augustan regime, who had taken militarism as a metaphor for sexual conquest, who had found Roman triumphs, Roman law, and the new emphasis on family values equally boring and provincial, was being made to suffer a punishment that in the most appallingly literal way fitted the crime. . .The choice of Tomis as Ovid’s place of enforced residence was a master-stroke. It cut him off, not only from Rome, but virtually from all current civilized Graeco-Roman culture. Wherever the intellectual beau monde might be found in AD 8, it was not on the shores of the Black Sea.12

Throughout the Tristia and Letters from the Black Sea, Ovid tirelessly bemoans the site of his exile. Early in the Tristia, Ovid recollects the lamentations of his household upon the moment of his departure (Tr I.3.17-24), and how unlike his journey to Athens during his boyhood years, this second grand voyage, this time during his middle age, was undertaken with heartbreak and uncertainty (Tr I.2.75-85). Even before he reached Tomis, according to the Tristia, at least, Ovid had a sense of the wildness of the Black Sea. “Ah misery!” he writes, “Gale-force winds black-ruffle the water, / sand, scoured from the bottom, boils up in waves that crash, mountain-high on prow and curving stern-post. . .the very keep groans at my woe” (Tr I.4.5-7,10). In the midst of his perilous voyage to Tomis, Ovid passed the time by writing. “Time and time again,” he recollects in the Tristia, “I was tossed by wintry tempests / and darkly menacing seas. . .yet my shaky / hand still kept writing verses” (Tr I.11.13-4,18).

Writing about Tomis, thereafter, often filled the last decade of Ovid’s life. Descriptions – almost always pejorative and very often repetitious – of Tomis’ fierce cold, its meager cultural resources, and its overall hostility litter his late works, the settlement acting as a sort of dark muse that threatened him with annihilation rather than filling him with inspiration. If you read the Tristia and Letters from the Black Sea back to back, by the time you venture into the latter book you are amply familiar with Ovid’s general impressions of Tomis. Let’s hear a long quote from the first book of Ovid’s epistles – a quote that’s representative of what he has to say about the land of his exile.

. . .Beset on all sides

by dangers I go my ways, in the midst of hostile natives

(as though with my country I’d also forfeited peace)

who, to double the chance of death in a grim wound, poison

their every arrow-tip with viper’s gall.

Thus armed, the horseman circles our nervous ramparts,

a wolf prowling round penned sheep:

his light bow, once it’s arched taut to its string of horsegut,

remains bent for all time, will not ever relax.

The rooftops bristle with a stubble of old arrows

and the gate with its heavy bar

barely holds off attack. What’s more, the land’s protected

by neither leaf nor tree: dead winter runs

into winter. Here, struggling with cold, with arrows,

with my grim fate, I’m drained

of strength by this fourth season: my tears flow uninterrupted

except when I pass out, when a sleep like death

stuns my senses. (Ep I.2.12-29)

These lines, written in the fourth year of Ovid’s exile, are a sort of gloomy stained glass window of Ovid’s perceptions of Tomis. We hear often of barbarians, and poisoned arrows, and Ovid himself being under direct physical duress from the warriors who live there. They are “Sarmatians, Bessi, Getae, names unworthy / of my talent” (Tr III.10.4-6) who nonetheless perpetually and perilously intrude on his existence there. They make the entire region “a barbarous coast. . .stalked ever by bloodshed, murder, [and] war” (Tr I.11.30-1). Plowmen, as you heard earlier, do their work with a sword in one hand, and the unlucky peasants who live beyond the town walls are perpetually vulnerable to pillaging and worse.

Ovid even reports having to help fight off raiders, telling a reader in the Tristia, “[N]ow, growing old, I strap on sword and buckler, / clap a helmet on my grey hairs – / The moment we’re warned of a raid by the guard in his look-out / I must, with trembling hands, go arm myself, / while the raiders, bows at the ready, arrows envenomed, / horses snorting, fiercely circle the wall” (Tr IV.1.70-8). And even though I’ve just read you a flurry of quotes from Ovid about the natives of Tomis, let’s hear one more – this one a general overview of the region’s culture, from the fifth book of the Tristia, again from the Peter Green translation.

Would you care to learn the nature of the local inhabitants,

find out amid what customs I survive?

They’re a mixed stock, Greek and native, but the natives –

still barely civilized – prevail.

Great hordes of tribal nomads – Sarmatians, Getae –

come riding in and out here, hog the crown

of the road, every one of them carrying bow and quiver

and poisoned arrows, yellow with viper’s gall:

harsh voices, fierce faces, warriors incarnate,

hair and beards shaggy, untrimmed,

hands not slow to draw – and drive home – the sheath-knife

that each barbarian wears strapped at his side. (Tr V.7.9-20)

Over the 94 poems that make up the Tristia and Letters from the Black Sea, Ovid unflaggingly bemoans the violence and cultural backwardness of the region. He finds no housing there to suit him, no food, no modern medicine, no one to speak with, physical illness, and bad water (Tr III.3.7-19). If Tomis itself is a grimy frontier town, what Ovid finds around it is worse – a stretch of tundra and wasteland on the fringe of the end of the world (Tr III.4B.47-52).

Ovid has a special fascination with the weather of the region. He imagines springtime in Rome, where vines burst with fresh flowers and blossoms appear in orchards, contrasting these visions with the chillier seasons of Tomis (Tr III.12.13-16). The cold there, he reports, is so deep that it nearly burns one when one goes outside (Tr III.2.7-11). Descriptions of ice, snow, and frozen waterways fill the pages of Ovid’s late poems, like this one in the third book of the Tristia.

[W]hen grim winter thrusts forth its rough-set visage,

and earth lies white under marmoreal frost,

when gales and blizzards make the far northern regions

unfit for habitation, then Danube’s ice

feels the weight of those creaking wagons. Snow falls: once fallen

it lies for ever, wind-frosted. Neither sun

nor rain can shift it. Before one fall’s melted, another

comes, and in many places lies two years,

and so fierce the gales, they wrench off rooftops, whirl them

headlong, skittle tall towers. (Tr III.10.9-18)

And that’s again the Peter Green translation, published by the University of California Press in 2005. If there is a main character in Ovid’s late poetry, other than the poet himself, it is Tomis. The hardscrabble frontier town that emerges in poem after poem after poem of the Tristia and Letters from the Black Sea haunts nearly every stanza of Ovid’s late poems, so that frozen swaths of sea, poisoned arrows, barbarian dialects, and frosty air ubiquitous within the verses he composed for a Roman readership from his exile.

On one hand, reading Ovid’s personal impressions of Tomis is intensely sad. The circumstances of his arrival there were disgraceful and humiliating. He was a very social person, who enjoyed a wide circle of intellectual and artistic friendships and was understood and contextualized by people who could appreciate the full extent of his linguistic brilliance. He lived in a place with a mild climate and moved to one with comparatively colder temperatures, and I think those of us who have moved from a warm climate to a cold one, or weathered some similar adjustment, have had the experience of watching the seasons pass in a strange place and dreaming of what it’s like at home. The darkness in Ovid’s late poetry is profound and almost never lets up, to the extent that the closing lines of the final letter of the Epistulae ex Ponto are “Malice, sheathe your bloody claws, spare this poor exile. . .There is no space in me now for another wound” (IV.16.47,52).

The culture of Tomis could not give Ovid the intellectual stimulation that he was accustomed to. He records his hopes that his later works will continue to be put into broad circulation, perhaps even within Rome’s eastern provinces (Tr IV.9.16-22). But at the same time, Ovid is keenly conscious of the fact that it can take a year for news and documents to travel between Rome and Tomis, and that over the course of any given year critical responses to his work can change, and fads can evolve, leaving him forgotten and oceans away from contemporary developments in Latin literature (Ep III.4.57-61, Ep IV.11.15-7). He tells an addressee that he’s hardly writing anything any more (Ep IV.2.22-6), and we can imagine that without access to Rome’s libraries and overall manuscript culture – a culture that had enabled him to produce the astoundingly erudite Metamorphoses and Fasti during the previous decade – he felt a sense of informational isolation, as well. Perhaps most extreme are Ovid’s descriptions of slowly losing his command of Latin itself. He writes that

This long endurance of troubles

has beaten down my talent, not one shred

of my old vigour survives. If, as now, I take my tablets

and try to force words to scan,

no real poems emerge – or only such as now reach you,

fit products of their master’s state, and place. (Tr V.12.31-6)

Isolation, exhaustion and strife have sapped his creative energies, and being surrounded by other languages and a lack of erudite Romans has eaten away at his abilities as a poet. He tells an addressee to be patient with his decaying phraseology, because it comes from a barbarian land (Tr I.3.17-18), that no one speaks Latin around him and he’s finding Latin difficult to recall (Tr V.7B.51-8), and that without Latin speakers and textual resources his speech and consciousness are slowly being infected with local dialects (Tr III.14.43-51).

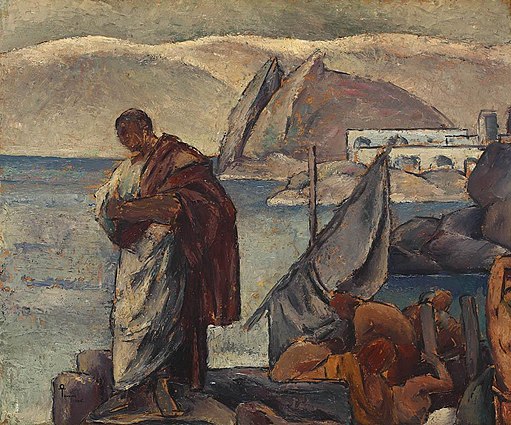

Eugène Delacroix’s Ovid Among the Scythians (1859) shows the poet in a clean white garment amidst armed figures and a drab landscape.

The bitterness of losing one’s home is a theme we’ve encountered before in Literature and History. The ancient Egyptian tales of “The Shipwrecked Sailor” and Story of Sinuhe chronicle expatriate Bronze Age Egyptian men’s anguish for their lost homelands. The Iliad, Odyssey, and lost Nostoi are peopled with characters who are oceans away from their homes, expatriated to fight in other people’s wars. Much of the exilic literature of the Bible – Jeremiah, Ezekiel, and the entire Deuteronomistic history – is poetry filled with a sense of deracination and cultural alienation. Closer to Ovid’s own time, the last Augustan Age poet might have encountered Cicero’s letters describing his brief exile to the Balkans in 58 BCE, or read Aeneas’ fraught remarks about missing Troy in Virgil’s Aeneid.The point of bringing up all of these literary analogs – particularly the Greco-Roman ones – is this. Ovid’s Tristia, and his Letters from the Black Sea, are, to some extent, an autobiographical recounting of one person’s ostracism and diaspora to foreign shores. But Ovid’s late works are also a literary performance – one in which the poet eagerly compares himself to legendary wanderers like Odysseus (Tr I.5, Ep IV.10), or his departure from his wife to Hector’s from Andromache (Tr IV.3) or his wife to Andromache and Penelope (Tr I.6). At one point Ovid mentions to his literary acquaintance Sevérus the prose correspondence that the two men have been keeping up (Ep IV.2.3-9), indicating that the elegiac stanzas that fill the Tristia and Letters from the Black Sea are a small, stylized excerpt of what he’s been producing abroad, rather than a representative swath of his real experiences in the provinces.

Now, the factual accuracy of Ovid’s late poetry is probably not an issue that you’re going to lose any sleep over, however much it’s one of the central questions of Ovidian scholarship. But the issue of the exilic poetry’s truthfulness invites us to consider something that must be universally human, and that is the discrepancy between our actual experiences and how we package these experiences to others in language in order to accomplish various kinds of goals. If you have moved somewhere, and you’re talking with friends back at home, you might, for instance, exaggerate the comforts of your new residence in order to justify your departure. You might magnify the discomforts of your new residence so as to let everyone who stayed behind know that you respected their decision to do so. Or, in Ovid’s case, you might dramatize the depths of your sufferings intensely and prolifically, over the course of dozens of published poems and a whole lost history of prose letters, in order to try and get back home. Scholar Gareth Williams, in a general assessment of the factual reliability of Ovid’s late works, writes the following:

Despite Ovid’s insistence on the sincerity of his exilic voice (cf. Trist. 3.1.5–10, 5.1.5–6, Pont. 3.9.49–50), recent scholarship has become increasingly alert to the exaggerations which aggravate his plight in Tomis, by his account a town located in a war-stricken cultural wasteland on the remotest margins of empire. Historical research tells a different story: Ovid’s Tomis is populated by the Thracian Getae, but there is no evidence to suggest that its Greek language and culture, originating from its Milesian foundation, were fatally eroded by the crude Getic presence which he describes; while inscriptional evidence indicates that Tomis was indeed threatened by sporadic attack in a still turbulent region (Moesia was brought under firm Roman control only late in the first century BC), Ovid clearly exaggerates the scale of the unrest; and other discrepancies abound, encouraging some modern sceptics to suspect that he never in fact set foot in Tomis and may even have invented the entire exile (an intriguing possibility, but the burden of proof remains with the doubters). True, Ovid’s readers in distant Rome, many of whom presumably had little or no direct experience of Moesia, might have been impressionable to an extent; on a practical level, greater sympathy for his plight might be won by exploiting Roman ignorance of a distant region.13

Thus, while Ovid’s remoteness from the Roman world was his chief source of complaint at the end of his life, this same remoteness allowed him to embellish and perhaps fictionalize the privations he endured in the distant northeast.

Now, we’ve covered some of the basic facts about the Tristia and Letters from the Black Sea. We learned a bit about the overall circumstances of Ovid’s exile, the general contents of his exilic poetry, and how his late works may take a great deal of poetic license in depicting Tomis as a wasteland at the earth’s end. Since the subject of fact and fiction in Ovid’s late poetry has come up, I want to talk discuss these poems just a bit more as rhetorical performances. Because if we read Ovid’s late work as a documentary record of his experience abroad, in many ways we miss the point. Ovid’s last poems are not tearstained diary entries, so much as they are carefully engineered productions, designed alternately to cajole, to mourn, to lambaste, to disparage, to hyperbolize, to brag, to vilify, and above all other things, to persuade. And their aim, nearly from end to end, regardless of how formulaic or repetitious they appear as a collection, is to regain the favor of Augustus and his subordinates, and get Ovid back to Rome.

Posturing and Inveigling in the Exilic Poetry

Ovid, especially in the later Letters from the Black Sea, is conscious of the repetitious nature of his late work, writing, “You must all be now bored stiff by these monotonous poems” (Ep III.7.3). He imagines a reader asking him “Will there never. . .be an end to these sniveling poems?” (Tr V.1.35). And yet at the same time, in a letter to his editor and literary agent Brutus, Ovid explains the repetitious quality of his final two books.[C]heerful, I [once] wrote cheerful verses; sad, I [now] write sad ones,

each phase has its matching work.

Of what should I write but the faults of this bitter region,

what pray for, but to die in a better place?

I write the same things so often, yet almost no one

listens: my words go nowhere, fall on deaf ears.

Yet though the words are the same, I write to different people –

one cry for help, but many addressees. (Ep III.9.35-42)

All of Ovid’s addressees, from close friends and family to more distant acquaintances, were likely to encounter the poet’s thoughts on Augustus. Rome’s first emperor looms over Ovid’s exilic poetry everywhere, the gatekeeper of Ovid’s hopes and dreams. In his youth, in the Art of Love, Ovid flouted Augustus’ social legislation and moreover had little to say about the emperor at all. During his exile, however, Ovid pivoted altogether, and laudations of Augustus are ubiquitous throughout his late poetry.

Ion Theodorescu-Sion’s Ovid’s Exile (1915). Artistic depictions of the banished poet take him at his word, showing a somber figure isolated and ruminating in bleak landscape. It’s important to remember, though, that Ovid kept himself busy, and that not the least of his activities was a constant epistolary effort to get back home – an effort that extended far beyond the letters that he published.

It is jarring, when one reads Ovid’s works in order, to move from the poet as a youthful rogue and ne’er-do-well to the poet as a sycophant and humble petitioner. Accustomed to Ovid as an irreverent cad, in his late works we frequently find him obsequious, and the transition is jolting and tragic as the final scenes of Rostand’s Cyrano de Bergerac. We look for traces of the panache and irreverence of Ovid’s youth, and instead, in the Tristia and Letters from the Black Sea, we find a virtuoso conquered by circumstance – a writer whose witty subversiveness has turned, all too often, into subservient groveling. As scholar Peter Green writes, Ovid “became querulous, repetitive, self-pitying and self-obsessed, humorless. The egotism that had been a lightweight joy in Rome’s enfant terrible of the boudoir became an embarrassing aberration. . .Tomis no longer let him be funny.”14 From time to time, there is evidence in Ovid’s late poetry of continued iconoclasm – that same iconoclasm that led Ovid to make fun of Julius Caesar’s male pattern baldness in Book 15 of the Metamorphoses while ostensibly praising Augustus’ lineage.15 But the poet’s subversiveness, in his exilic poetry, at least, is subdued by the overall motive of the collection.

Ovid’s lamentations, and his dozens of deifications of Augustus were employed for a purpose. And this purpose, again, of which the poet makes no secret, was either mitigating the terms of Ovid’s exile or actually securing his return to Rome. The poet wrote widely to anyone he could find connected with Augustus, asking a broad assortment of addressees to talk to Augustus for him, or one of Augustus’ relatives, to make his compunction clear to the emperor, and to tell all of Rome that he was alive and desirous of returning home. At one point, Ovid even asks his wife to speak with Augustus’ wife (Ep III.1.139-43), offering instructions on just how this meeting ought to be conducted. And thus, if there is tragedy in Ovid’s late works – the tragedy of a middle aged writer with no real power to better his plight, there is also strategy, and logic. The Tristia and Letters from the Black Sea are nothing if not thorough, exploring all possible avenues back to Rome, or at least the Mediterranean.

Further, while Ovid’s late work can be repetitious in its kowtowing to the emperor, Ovid also stands up for his work as a poet. Admitting his powerlessness does not lead Ovid to criticize his long and decorated career as a writer, and at a number of junctures he takes heart in the fact that he’s still a widely respected author. Thus, in the lengthy first poem in the second book of the Tristia, Ovid mixes praises and petitions to Augustus with words of self defense. The poem bows to Augustus as “our fatherland’s father” (Tr II.1.181), but not before attesting that Ovid himself isn’t going to be forgotten any time soon. Ovid writes,

They may say I misused my talent with youthful indiscretion –

but my name’s still known world-wide;

the world of culture’s well acquainted with Ovid, regards him

as a writer not to be despised. (II.1.117-20)

The Art of Love – that poem which was most likely part of the reason for Ovid’s exile – comes up often in his exilic poetry. At one point he calls it a poor joke of his youth (Tr I.9.61-4), and a piece of art that destroyed its artist (Tr III.14.6), and at other junctures acknowledges its controversial nature (Ep II.9.73-6, II.10.11-13, II.11.1-2). Yet at the same time Ovid stands up for even the most prurient passages in the Art of Love, telling Cupid himself that “I never troubled legitimate marriage-beds: / what I wrote was for women whose hair lacks the modest [attire], / whose skirts don’t reach their feet” (Ep III.3.49-52).

Thus, coming to his own defense in regards to even his most scandalous work, Ovid emphasizes that his youthful lines on love and courtship hardly constitute an act of treason. He might be reduced to frostbitten Tomis, but the somber circumstances of his present to not tarnish the luminous achievements of his past. And Ovid is perhaps never more optimistic, and rarely more emotive, than when writing to his wife.

Ovid was, according to his own account, married three times – first, to a feckless young woman when he himself was barely an adult, then, a more praiseworthy woman who for whatever reason didn’t remain his wife for long, and then finally, to his third wife, who remained loyal to him during his exile (Tr IV.10.69-74). While we don’t know her name, Ovid’s third wife seems to have been a divorcee or a widow with a daughter, who may have been a member of Ovid’s patron’s household and perhaps a relative of Ovid’s literary friend Aemilius Macer.16 Ovid’s third wife is a frequent presence in his exilic poetry. He praises her loyalty, affirming that she is his Penelope, and we get a sense that her steady support helped him bear the pangs of missing home. She may have even joined Ovid in Tomis in the last years of his life there.17 Whoever she was, and whatever the exact logistics of their partnership, Ovid’s wife inspires some of the more optimistic moments in his late poetry. The opening book of the Tristia promises her that “in so far as our words of praise have power / you shall live through these verses for all time” (Tr I.6.35-6). The closing book of the Tristia repeats this same sentiment, bundling literary self-aggrandizement together with praises of his wife’s overall fidelity.

How great a monument I’ve built you in my writings,

wife dearer to me than myself, you yourself can see.

Though Fortune strip much from their author, yet my talent

shall make you illustrious; as long

as I’m read, your legend and mine will be read together. (Tr V.14.1-5)

These last lines are eerily similar to Shakespeare’s “So long lives this, and this gives life to thee” in Sonnet 23. In both cases, and in similar egotistical love poems by writers from Catullus and Propertius onward, a male writer paradoxically praises a female addressee by promising her that she will be great due to his greatness. And while Ovid admits lewdness in his youthful work, in envisioning his luminous literary future – a future so bright that it will even immortalize his spouse – Ovid demonstrates that his artistic self-confidence ultimately didn’t falter during his long years abroad.18 [music]

Traces of Assimilation and Resignation in the Exilic Poetry

The modern reader of Ovid’s late poetry faces a certain challenge when reading the 96 poems as a set. Their sheer repetitiousness is perhaps the greatest impediment to enjoying them as a collection. Even a craftsman as talented as Ovid is at pains to make variants of the same story, and the same appeals engaging over dozens and dozens of iterations. Further, modern readers are less inclined to accept the Roman dichotomy between citizen and barbarian, or imperial capital and subjugated provinces, and thus we are liable to feel as sorry for the recently colonized natives of Tomis as we are the celebrity poet Ovid, who emphasizes repeatedly that he was able to retain his financial resources even though he was exiled. How bad, we wonder, does the fussy city-boy have it, living within in the walls of a major settlement, when the peasantry all around him is vulnerable to mounted marauders and Roman tax farming alike? At its worst moments, Ovid’s exilic poetry can feel like an overdone experiment in ethnocentrism and egocentric self pity, as the poet touts his own literary immortality, disparages the men and women around him, and spends nearly half a decade maundering about Rome and ignoring the potential friends and resources around him. However, throughout Ovid’s late poetry we do get the occasional sense that the poet has made some steps toward assimilation, suggesting a fascinating hidden story of the celebrity Latin writer’s immersion into cultures and languages largely lost to history. The story of this gradual assimilation is first evident in the earlier Tristia, when Ovid records,All round about me Thracian and Scythian voices

chatter away: I think I could write verse

in Getic. Believe me, I fear you may find my Latin

diluted with Black Sea usage, local terms infecting my work. (Tr III.14.43-51)

In context, these lines, addressed to Ovid’s patron, deplore the poet’s absence from his accustomed milieu and demonstrate his fear of not being able to function as a writer outside of the refined inner circles of Rome. Yet much later, after hundreds of lines bewailing the cold winters and taut bowstrings of the Danube, Ovid’s views on Tomis change slightly. Ovid’s fourth book of the Letters from the Black Sea contains the most evidence of the poet slowly becoming habituated to the culture of Tomis, and this collection is often thought to have been published posthumously.19 Tomis was no longer new to the poet at this point – he had spent a number of winters there, and however much he continued to try and write his way back into Rome, Ovid was no stranger to the shores of the Black Sea. He writes to his friend Graecinus that he does feel liked and appreciated in Tomis, and that the settlement’s citizens, at least, would prefer that he stayed there (Ep IV.9.97-101). Further evidence late in the Letters from the Black Sea suggests that Ovid may have developed an interest in the cultures and languages around him during his exile.

He writes to his friend Carus, a tutor in the imperial household of Rome, that he’s been composing works in Getic, a language spoken by a tribal people from Thrace, or the area where modern day Turkey, Greece, and Bulgaria come together. Specifically, Ovid writes,

. . .I blush to admit it, I’ve even composed in the Getic language,

bending barbarian patois to our verse:

among the uncultured natives I’m getting a reputation

as a poet. Congratulate me: I’ve made a hit. (Ep IV.13.18-22)

These are not, obviously, altogether complimentary words, but nonetheless they suggest that the poet may have become interested enough in Getic culture to spend time learning the language and bringing it over into elegiac couplets or dactylic hexameter. Even more telling is a set of lines in the third-to-last poem Ovid may have ever written – lines in which Ovid emphasizes that he likes the people of Tomis – just not the climate or the mounted raiders who terrorize the local countryside. Ovid, addressing the citizens of Tomis themselves, assures them that

. . .I’ve done nothing wrong, men of Tomis, I’ve committed

no crime: you I love, although I loathe your land.

Let anyone go through my work: there’s not one letter

makes any complaints about you –

the cold, the constant fear of raids from every quarter,

the enemy at the gate: it’s of these I complain;

and against the place – not its people – I’ve brought true charges. (Ep IV.14.23-9)

Again, Ovid’s motivations for writing these lines are as mysterious as they are fascinating. Had the poet been confronted by a neighbor about denigrating the land of his exile? Had he read something from his fellow correspondent that he felt went too far in maligning Tomis, and come to the settlement’s defense? Had he simply come to a point at which he knew and was friends with many non-Romans, and wanted it on record that he hated the weather and dangers of Tomis, but not his neighbors and confidants?

We don’t get a lot of personal records of interactions between Romans and non-Romans in most of what survives from this period Roman history. We have Tacitus’ Germania and Agricola, Strabo’s Geographica, and Pliny the Elder’s Natural History, but these were not written by expatriates who had left the Roman world and permanently settled abroad. Ovid did not encounter the citizens of Tomis as part of an ethnographic study – his interactions with them were local and long term, and sufficient enough, at least, to produce some meaningful linguistic and literary interchange.

It’s a stretch, however, to imagine that Ovid somehow went native at the end of his life and became adopted by the polyglot settlers of Tomis, leaving thoughts of Rome behind him and carrying on his literary and social careers in the languages of the northeast. I think there’s more evidence – late in the Letters from the Black Sea, at least – that he began to find writing home more a process of self-torture than one of catharsis. Nearly half a decade of repining about his exile, to a large and varied bundle of influential Romans, had brought him nothing. Eventually, Ovid seems to have realized that his poems about his exile were helping him neither logistically nor psychologically. And Ovid writes, in the older Arthur Leslie Wheeler prose translation,

[It’s] good to embrace a hope – though it bring no good and be ever in vain – and whatever you long for that you may deem will happen. The next stage is utterly to give up hope of salvation, to know once and for all with full assurance that one is lost. Some wounds are made worse by treatment, as we see: it had been better not to touch them. More merciful is his death who is suddenly overwhelmed by the waters than his who wearies his arms in the heaving seas. Why did I conceive it possible for me to leave the Scythian land and enjoy a happier one? Why did I ever hope any mercy for myself? Was it thus that I had come to know my fate? [Oh!] my torture is all the worse, and the repeated description of this place but renews and freshens the harshness of my exile. . .If only [Augustus’] wrath does not deny me this, I shall bravely die on the shores of the [Black] sea. (Ep III.7.21-40)20

Johann Heinrich Schönfeld’s Scythians at the Tomb of Ovid (c. 1640). Schönfeld, like others induces from Ovid’s poetry that a slowly increasing amity spread between the writer and his culturally unfamiliar neighbors.

There is no singular turnabout or epiphany late in the Letters from the Black Sea – no moment at which the fifty-something poet suddenly gives up and decides to make the best of his loss of home. But there is a sense that the poet experienced a gradual metamorphosis in his middle age. The other Augustan Age poets whose work has survived all viewed writing as a causeway to immortality, and considering how much time we’ve spent with them in this podcast, they weren’t especially wrong to do so. Yet Ovid, who lived longer than any of them, and produced more poetry, most clearly records the opposite – that writing, particularly extensive autobiographical chronicles – can trap one into an echo chamber of one’s own thoughts and presuppositions, or renew the ghosts of the past with every stroke of the pen. We today live in an age of many Ovids – many forced migrations and losses of home far more dire than Ovid’s own. And we know, as Ovid did, that home is always worth fighting for, and remembering, and recording for posterity, in all of its cultural richness and tantalizing detail. But at the same time, living in a world of memory, and squeezing oneself into ink on a page, day after day, is not always a path toward coping and moving on. And there is a lesson in the very last lines that we possess from Ovid – those indelible closing sentences of the Letters from the Black Sea that I briefly quoted earlier. Ovid writes, in the Wheeler translation,

So, Malice, cease to tear one banished from his country; scatter not my ashes, cruel one! I have lost all; life alone remains. . .What pleasure to [you] to drive the steel into limbs already dead? There is no space in me now for a new wound.21

I think those of us who love literature like to think of writing as a cathartic process – as a means of processing our own problems and doing our small part to help make the world a better place. But there are times, as Ovid seems to realize here, that enough has been said on a subject, when words torment wounds, when it’s time, insofar as one can, to try and let go. [music]

The “Error” of carmen et error

Augustus, the lynchpin of Roman history, died in August of 14 CE at the age of 75. Ovid, still in his fifties, survived for three more years abroad, but never returned. Earlier in this episode, we talked about Ovid’s own explanation of his exile – his statement early in the Tristia that “It was two offences undid me, a poem and an error” (Tr II.1.207). We talked about the poem – most certainly the Art of Love. The error, however, is something we haven’t discussed yet, and while I’m certainly no authority on the subject, I’d like to introduce you to one compelling theory. First of all, the Latin word error had a specific legal meaning in Latin – a “mistake made in ignorance,” rather than a wilful transgression.22 Ovid’s famous mention of his mysterious misdeed thus describes it as an breach of conduct made by accident. And elsewhere, in a couple of brief passages in the Tristia, Ovid he describes his error in just a bit more detail. Ovid writes,I said nothing, my tongue never shaped words of violence,

no seditious impieties escaped me in my cups.

Unwitting, I witnessed a crime: for that I’m afflicted:

my offence is that I had eyes. (Tr III.5.47-50)

That Ovid witnessed something, and said nothing, and thus became culpable of something, however ambiguous all of this sounds, is at the heart of modern theories on why the poet was exiled. A later poem in the Tristia sketches out Ovid’s error in a bit more detail. He explains, again in the University of California Press Peter Green translation,

To tell by what mischance

my eyes became accomplices to a deadly outrage

would take time. . .I’ll not

say more than this: I did wrong, but my wrongdoing

sought no recompense, no reward,

and if you want an appropriate description

for such a deed, the name of my crime should be

folly – and if I lie, then seek a yet more distant

place for my exile, call this a suburb of Rome! (Tr III.6.26-8,32-8)

There isn’t a great deal of detail here, obviously – we again get the sense that Ovid witnessed something and stayed silent about it, and that this was why Augustus booted him out of Rome. Maybe the Art of Love, published in its entirety a decade before Ovid’s exile, was merely a pretense, and the heart of his transgression was complicity in something that the emperor ultimately opposed. That, for the most part, is what we know about the crime for which Ovid was exiled, which, being a delicate subject, he doesn’t discuss much in his exilic poems.

One theory on Ovid’s exile with decent evidence to back it is that he became aware of a conspiracy by the Julian branch to struggle to primacy over the Claudian branch. But while he was aware of the conspiracy, he didn’t bring it to the emperor’s attention. Julio-Claudian family tree by Muriel Gottrop.

Ovid was in the center of the Roman world during this imperial horse race, and from his poetry, at least, he seems to have taken a side. The poet speaks highly of Augustus’ grandsons Gaius and Lucius, and just as loftily of Germanicus, Augustus’ grand-nephew through his sister Octavia, and the brother of the future dark horse emperor Claudius. Germanicus comes up frequently in Ovid’s exilic poetry, and Ovid, like so many Romans, seemed to see the popular war hero as the paragon of all Roman virtue. The emperor’s wife, however, did not share this sentiment.

There are records of two different Julian conspiracies against the Claudians – efforts, put simply, to invalidate Augustus’ stepsons’ claims to the throne and to pave the way for his grandsons and grand nephews.23 It is possible that Ovid was peripherally implicated in one of these plots – his poetry reveals no partiality to Livia’s sons, after all. And further, upon the emperor’s death, when Tiberius took the throne, we have no evidence that Ovid was invited back to the city. If Ovid had backed other claimants, then, Augustus’ wife Livia Drusilla, whose son Tiberius ascended to the throne, the emperor’s wife didn’t forget it.

It’s difficult to piece together the story behind Ovid’s exile – what I’ve just given you is a general modern theory that has some coherent evidence behind it, and maybe we can most safely say that the poet saw something that he shouldn’t have, and that whatever it was was enough to estrange him not only from the emperor, but from the emperor’s wife, and her son, as well. But whatever the reason for his banishment, Ovid never did get to go home. What survives of Augustan Age literature sputters out in the last lines of a crestfallen celebrity, a thousand miles from home.

As Ovid watched winter fall over Tomis in 15 CE, and then 16, and 17, and Tiberius launched his increasingly unpopular 22-year reign, Ovid must have had a sense of Rome’s dreadfully uncertain future. In his youth, Ovid had witnessed the emperor’s ascendancy, and brushed shoulders with veterans of the civil wars and diehards of the battered republican system of government. And while Augustus assumed the title of Princeps with a decade and a half of blood on his hands, few doubted his intelligence, or his shrewdness, or his sense of how to keep the empire operating. Tiberius, however, was an altogether different subject, whose rise to absolute power was imperial Rome’s first great dynastic roll of the dice. And so the last few years of Ovid’s life allowed him to see a pivot point in Roman history. He saw the beginning of the empire – the full reign of Augustus, and all the splendor that it entailed. But Ovid also saw the rise of Tiberius, a man who, for whatever reason, Ovid seems to have thought ought not to rule.

And Ovid saw something else, perhaps, gazing north along the chilly coastline of the Black Sea, or west, into the wintry riverside lands along the unmapped reaches of the Danube. He had thought, perhaps, with the Metamorphoses and the Fasti, that he had composed poems that synthesized the world’s myths and catalogued Rome’s own cultural heritage, to boot, bringing Roman literature to a crescendo in the same way that Augustus had brought Roman history to a summit. But Tomis dispelled the illusion. Beyond the settlement’s walls, in the unknown territories of central Europe, Germanic tribes were descending along the Rhine, the Elbe, the Vistula, the upper Danube, and beyond. In the city of Rome, in his thirties, as Augustus held sway over an ocean, Ovid might have shared Rome’s sense of manifest destiny and cultural primacy. But in the last years of his life, in Tomis, Ovid would have realized that succession would be the Achilles heel of the Roman Empire, and that in the dark heart of the European frontier, there were many unconquered peoples, and many poisoned arrows. [music]

Moving on to the “Silver Age” of Latin Literature

I want to thank Professor Matthew McGowan of Fordham University for reviewing this episode’s transcription before I recorded it. Professor McGowan is a Latinist whose first book, Ovid in Exile: Power and Poetic Redress in the Tristia and Epistulae ex Ponto is all about Ovid’s later works, so he was an ideal reader to take a look at this particular episode. This book explores how the poet’s late works analyze the evolution of Roman culture beneath the first emperor, and how Ovid’s unique position as the last and longest living Augustan Age poet allowed him to have a hindsight on Roman history unavailable to his earlier contemporaries. Professor McGowan supports classics podcasting so much that he helped put a panel on at this year’s Society for Classical Studies conference in January in San Diego, at which yours truly presented. Professor McGowan, as you know this isn’t the easiest or simplest juncture of Latin literary history, and I and all my listeners out there really appreciate your help.Well, everybody, these past fourteen episodes, a number of which have topped two hours, have been on Augustan Age literature, and after some 115 hours of episodes on ancient literary history, it’s time for us to move from BCE to CE, for the most part, for good. This is an interesting turning point in Roman literature, one which has often been called the end of the golden age of Roman literature and the beginning of the silver age. Generally writers like Cicero, Horace, Virgil, and Ovid are better known than their successors in the next two centuries – Seneca, Petronius, Lucan, Statius, Juvenal, and Apuleius not to mention later Latin poets like Nonnus, Ausonius, and Rutulius Namatianus. While I don’t necessarily agree that the deaths of Augustus and Ovid in 14 and 17 CE somehow ended an entire cultural and artistic period and gave rise to a new one, if you’re taking a course on Roman literature you generally get introduced to the concept of the golden and silver ages.

The golden age, so the story goes, stretches from Cicero to Ovid, and it’s characterized by boldness, fearless innovation, and spirited clarity. During the firestorm that ended the republic, and thereafter, during the stable prosperity and patronage system of the Augustan principate, two generations of astounding writers had the motivations and the resources to write tracts and poems that changed their culture forever after. During the first century CE, though, so the story goes, as Tiberius hosted grotesque sex parties on the island of Capri, as Caligula declared his horse a consul, and as Nero exhausted the financial resources of the empire to build himself a golden palace, Latin literature grew decadent, and more filled with frippery and mannerism than fiber and lucidity. An originator of this periodization of Latin literature – in other words that there was a golden age of Latin followed by a silver age, was the German classical scholar Wilhelm Siegmund Teuffel. Teuffel published a 2-volume set called A History of Roman Literature in 1870, and the second volume of this set covers the imperial period. Teuffel begins a memorable description of silver age Latin literature with the notion that Romans during the imperial period, unlike their predecessors, were compelled to live lives of dissimulation. Here’s a long quote from an English translation of Teuffel’s book – this will give you a good sense of how literary scholars have traditionally differentiated republican and Augustan age literature on one hand, and imperial period literature on the other. Teuffel writes that during the imperial period,

As it was impossible to display true character when all endeavoured to create the impression of being different from what they really were, the consequence was hypocrisy and affectation. Forced carefully to hide nature, people fell into artificial and unnatural ways. Always watched by spies, or at least thinking themselves to be watched, they always felt as if they were on a stage; they calculated what impression their conduct would produce on their contemporaries and posterity; they adapted themselves to certain parts and studied theatrical attitudes, they declaimed instead of speaking. . .The uncertainty of existence and possession, the continual apprehension, in which this period moved and breathed, caused a restless versatility, morbid irrationality and hurry. . .The general character of this age appears also in its style. Simple and natural composition was considered insipid; the style was to be brilliant, piquant, and interesting. Hence it was dressed up with much tinsel of sentences, rhetorical figures, and poetical expressions. But the same end was aimed at in different ways: the one dallying. . .with brief, cut-up sentences, the other with antique roughness or. . .with artificial obscurity; now effect was sought after by epigrammic points. . .now by glaring colours. . .some cultivated outward polish, even at the cost of the contents. . .others again endeavored to give the impression of profound thought. Manner supplanted style, and bombastic pathos succeeded to the place of quiet power. It is true that under Vespasian some became aware of having sunk into utter unnaturalness and intentionally endeavoured to regain the simplicity of thought and the rotundity of phrase peculiar to the Ciceronian age. . .But this is so little in harmony with the general tendency of the time, as to produce no further effect to be unattainable even to these men in its full extent. . .But on the whole, literature lost the sympathy of the nation at large; most emperors even intentionally widened the chasm between the educated and the great multitude, so that the latter were quiet, if not well-pleased, spectators of the maltreatment and spoilation of the higher classes.24

So, this a fairly representative take on the way Latin literature was once periodized by classicists in the past, and is still sometimes periodized today. Teuffel’s younger contemporary Charles Thomas Crutwell has a similar take in his omnibus history of Roman literature, published in 1886. He agrees that the silver age Latin writers traded substance for artificiality, and that ultimately during the imperial period, shorter quote this time,

The applause of the [private] lecture-room was a poor substitute for the thunders of the [public] assembly. Hence arose a declamatory tone, which strove by frigid and almost hysterical exaggeration to make up for the healthy stimulus afforded by daily contact with affairs. The vein of artificial rhetoric, antithesis, and epigram. . .owes its origin to this forced contentment with an uncongenial sphere. With the decay of freedom, taste sank. . .The flowers which had bloomed so delicately in the wreath of the Augustan poets, short-lived as fragrant, scatter their sweetness no more in the rank weed-grown garden of their successors.25

The rhetoric here is a bit overblown, but I’m sure you get the point. Golden age Latin literature was salubrious and free, silver age Latin literature was cramped and overripe. Today, we’re a bit more cautious about making such broad generalizations, and Siegmund and Cruttwell both exemplify the pitfalls assuming that history deterministically affects literature, but nonetheless these nineteenth-century literary historians invite us to remember that after Augustus, Roman literature was produced under the reigns of emperors – sometimes violent, erratic, and insecure emperors – and had to be written with more discretion than was used in the decades of Catullus, who could still call Julius Caesar a diseased pedophile and get away scot-free.

Peter Paul Rubens’ The Death of Seneca. Filthy rich, and deeply tied up in the imperial family for most of his life, Seneca was simultaneously powerful and helpless, and his philosophy and drama runs the gamut between stoic self certainty and intense, absolute horror.

We will do four programs on Seneca. The first will cover his life and his famous death and the history that he lived through. The second will be about Seneca and stoicism – the general history of stoicism leading up to Seneca, his own contributions to it, and the surprisingly pervasive influence of stoicism on the New Testament, which was being worked on from the reign of Claudius onward. And finally, we cannot ignore Senecan tragedy. The resurgence of Seneca’s gory and bleak plays, beginning with a showing of Phaedra in Rome in 1485, kicked off the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries’ preoccupation with blood splattered revenge tragedies, like Thomas Kyd’s Spanish Tragedy, John Webster’s The Duchess of Malfi, and Shakespeare’s Titus and Hamlet.26 While Seneca’s contradictions and the diversity of work he authored make him a difficult figure to study, he is more than worth four episodes. His life story is the tale of any Roman intellectual who tried to survive the extravagant rot of the Julio-Claudian dynasty. Seneca’s particular brand of stoicism, with its notion of the moral impregnability and tempered lifestyle of the wise man, was so evident in the Pauline epistles and New Testament more generally that generations of Christian writers – Lactantius, Tertullian, and Jerome, endorsed Seneca’s works. Seneca’s older brother Novatus is lauded in the Book of Acts for having rejected Jewish charges against the apostle Paul (Acts 18:12-16) – Seneca’s brother was serving as proconsul in the east at the time, and so the ties between Seneca, stoicism, and the authors of the New Testament, which we’ll discuss more before too long, run quite deep.27

So next time, we’re going to meet a brave new world of Roman history – a generation of men and women who never knew the republic firsthand, and whose writings, while not exactly the artificial tinsel described by the German literary historian Wilhelm Teuffel, necessarily had to be more cautious and conservative than those of their ancestors. For you Patreon supporters I’ve put up audio recordings of some more classics themed poems – Tennyson’s “The Lotos-Eaters” and “Ulysses,” both of which have to do with Homer’s Odyssey. “Ulysses” is a famous one about the restlessness of the hero once he returns home, and “The Lotos-Eaters” the dreamy and dark saga of Odysseus’ men arriving on an island and getting addicted to a mysterious drug. I also, just for fun, recorded one of my favorite poems in the universe – that’s Walt Whitman’s “Crossing Brooklyn Ferry,” a poem about the similarity of human experience over space and time. I think the world needs Whitman right now, and these audio recordings all have little introductions for you that should make understanding them easy if you’re unfamiliar with them. With all this work I’ve been doing in antiquity lately, sometimes I miss my home turf of the nineteenth century, and it’s a joy to share some of it with you guys who have pledged a dollar per new show. I have a quiz on this episode up at literatureandhistory.com if you want to test your retention of all things Ovid, and the later years of Augustus’ reign. Thanks for listening to Literature and History. If you want to hear a song, it’s coming right up, and if not, see you next time.

Still listening? I got to thinking – you know I’ve already written all the episodes on Seneca, as I mentioned earlier. Seneca also ended up exiled. Cicero, Ovid, and Seneca, then, all suffered from banishment, and all three wrote prolifically while in exile. And none of them exactly displayed stereotypical Roman grit under the duress of homesickness. While each man was allowed to retain his fortune and in Seneca’s case, even have his family and slaves with him abroad, each writer sniveled and whined to no end about missing Rome. Now I don’t want to diminish the extent to which homesickness can be cripplingly sad – especially for immigrants forced to move and others compelled to leave their home turf with little or no say in the matter. That said, considering that all three of these ancient Romans lived in a world of crucifixions, gladiatorial games, slavery, and mass starvation, from time to time the modern reader can’t help but cringe a little bit at the extent of unrestrained self-pity in Roman exilic writing. These three guys – Cicero, Ovid, and Seneca – they were exiled, sure, but they still had their titles, their fortunes, their stuff, and so sometimes hearing just how sorry they felt for themselves is astonishing. So I wrote this piano tune, in which Cicero, then Ovid, and then Seneca all enter and tell you about how incomparably awful it is to be a wealthy, propertied, famous man, and be ordered to leave Rome. This one’s called “The Exile Song.” Hope you like it, and in the next show, we’re going to begin our dive into the glittering, rococo world of the Julio-Claudians, and Silver Age Latin poetry.

References

2.^ Ovid. Tristia, Ex Ponto. Translated and with an Introduction by Arthur Leslie Wheeler. Harvard University Press, 1939, pp. 373,5.

3.^ Wilson, Emily. The Greatest Empire: A Life of Seneca. Oxford University Press, 2014, p. 82.

4.^ Virgil. Georgics: A Poem of the Land. Translated and with an Introduction by Kimberly Johnson. Penguin Classics, 2009, pp. 100-102.

5.^ Ovid. The Poems of Exile: Tristia and the Black Sea Letters. Translated and with an Introduction by Peter Green. University of California Press, 2005, p. 100.

6.^ See Green, Peter. “Introduction.” Printed in Ovid. The Poems of Exile: Tristia and the Black Sea Letters. Translated and with an Introduction by Peter Green. University of California Press, 2005. Kindle Edition, Location 389.

7.^ The Ovidian chronology here comes from Ovid. Heroides. Translated with Introductions and Notes by Harold Isbell. Penguin Books, 1990, pp. xxiii-xxiv.

8.^ See Velleius Paterculus 2.112.6-7 and Cassius Dio, Roman History 60.31-2.

9.^ The book was banned from Rome’s three public libraries, as Ovid attests in Tr III.1.59-82 and III.14.5-8. And in Tr II.1.7-9 he explicitly mentions the Ars as the text that offended the emperor, alluding further to the same poem in II.1.211-12..

10.^ Wiseman, Ann and Wiseman, Peter. “Introduction.” Ovid. Fasti. Oxford University Press, 2013, p. xxi. Peter Green writes that “[T]he Art of Love was published in the immediate wake of a scandalous and notorious cause célèbre directly involving the Princeps,” meaning the exile of Julia. See Green, Peter. “Introduction.” In Ovid. The Poems of Exile: Tristia and the Black Sea Letters. Translated and with an Introduction and Notes by Peter Green. University of California Press, 2005. Kindle Edition, Location 282.

11.^ The explanation is, of course simplistic. Peter Green points out that Ovid’s journey into epic and national history was at least in part driven by a desire for artistic development, and also that “the death of Ovid’s father and his third marriage both probably fell within the period of 2 BC-AD 1” (ibid, 297). Following these events, Ovid had access to his full patrimony, and additionally, evidence suggests, a marriage that may have changed his attitude about women, both of which would have opened the door to longer works beyond the scope of love elegy.

12.^ Green, Peter. “Introduction.” In Ovid. The Poems of Exile: Tristia and the Black Sea Letters. Translated and with an Introduction and Notes by Peter Green. University of California Press, 2005. Kindle Edition, Location 352.

13.^ Williams, Gareth. “Ovid’s Exile Poetry: Tristia, Epistulae ex Ponto and Ibis.” Printed in The Cambridge Companion to Ovid. Cambridge University Press, 2002, p. 235. A principal proponent of the exile-as-myth theory is A.D. Fitton Brown. (See Fitton-Brown, A.D. “The Unreality of Ovid’s Tomitan Exile.” Liverpool Classical Monthly 10 (1985), pp. 18-22.

14.^ See Green, Peter. “Introduction.” In Ovid. The Poems of Exile: Tristia and the Black Sea Letters. Translated and with an Introduction and Notes by Peter Green. University of California Press, 2005. Kindle Edition, Location 545.

15.^ Ibid, Location 565.

17.^ Ibid, Location 513.

18.^ On this note see also Tr IV.9.16-22.

19.^ See Green (2005), Location 830.

20.^ Ovid. Tristia, Ex Ponto. Translated and with an Introduction by Arthur Leslie Wheeler. Harvard University Press, 1939, p. 417.

21.^ Ibid, p. 489.

22.^ Thanks to Professor Matt McGowan for clarification on this point.

23.^ See Green (2005), Location 336.

24.^ Teuffel, Wilhelm Siegmund. A History of Roman Literature, Volume 2: The Imperial Period. Translated by Wilhelm Wagner. London: George Bell and Sons, 1873, pp. 3-6.

25.^ Cruttwell, Charles Thomas. A History of Roman Literature from the Earliest Period to the Death of Marcus Aurelius. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1886, p. 6.

26.^ See Wilson, Emily. The Greatest Empire: A Life of Seneca. Oxford University Press, 2014, p. 223.

27.^ Confusingly, Novatus is called “Gallio” in Acts 18 – Novatus had been adopted by an orator and poet named Gallio and followed the Roman custom of taking his adopted father’s name.