Episode 68: Love Means Sin

Seneca’s Phaedra (c 50s CE) is the story of an illicit passion, a stoic cautionary tale and simultaneously vivid character study.

| Read Transcription | References and Notes |

| Episode Quiz | |

| Episode on Spotify | Episode on Apple Podcasts |

| Previous Show | Next Show |

Seneca’s Phaedra

Hello, and welcome to Literature and History. Episode 68: Love Means Sin. This program is on the play Phaedra, written by the Roman author Seneca the Younger some time around the 40s or 50s CE, likely during the reign of Claudius or Nero. The exact chronology of Phaedra’s production, and whether the play was ever staged at all during Seneca’s lifetime, remain uncertain. But we do know that this was one of the earliest pieces of classical theater to be staged during the European Renaissance – perhaps the earliest of all. In 1484, the play was performed at the Saint George Palace in Rennes, France.1 The next year, in 1485, Phaedra premiered in Rome, an event that scholar Emily Wilson describes as “the starting point of early modern drama.”2

The play’s four central characters from left to right – a burly Theseus, regal Phaedra, percipient Nurse, and unexpectedly timid Hippolytus. 18th-century German, author unknown.

As a play, however, Phaedra seems an unlikely piece to set in motion the more sensational and violent plays of the Early Modern period. In a sentence, Phaedra is a play about a stepmother who falls in love with her stepson, and the catastrophic impact that her illicit passion has on the family. The tale of a neglected housewife and stepmother, Phaedra is, for Seneca at least, a slow burn, lacking the explosive violence of Thyestes and the extremes of Seneca’s Medea and Agamemnon. But tales of neglected housewives have caused literature to turn corners at some very important junctures. The adult Medea, on whom nearly every tragedian in the ancient world seems to have written a play, could be described as one such figure. Bored housewives litter the pages of Chaucer and Boccaccio, their sexual misadventures delightful and sometimes awkward counterpoints to the righteous martyr stories of The Canterbury Tales and the Decameron. Gustave Flaubert’s character Emma Bovary, who helped usher in a new epoch of French literary realism, is the victim of a stale marriage. Henrik Ibsen’s Nora Helmer, in 1879, scandalized late-nineteenth-century Europe and kicked off an era of naturalist theater about contemporary domestic life. And in this population of tremendously influential female leads, from semidivine Medea to Chaucer’s lusty carpenter’s wife Alisoun, we need to place Seneca’s Phaedra, a woman whose passions, and whose energies, are the spurs to her story’s central actions.

In past episodes we’ve talked about an archetype in ancient Mediterranean literature called the “helpful princess,” a female figure who aids a male adventurer in his quest and then, generally, gets left behind.4 Common examples include Homer’s Calypso, Nausicaa and Circe, Virgil’s Creusa and Dido, and a host of figures out of Ovid’s Heroides – Phyllis, Oenone, Briseis, Hypsipyle, and Hermione. This list of heroines has a corresponding list of male counterparts – adventurers and warmongers and adulterers who leave lovers and wives behind due either to necessity or merely a restless search for novelty. And as we open the pages of Seneca’s Phaedra, we need to meet a new adventurer – one who spent his boyhood in obscurity in the eastern Peloponnese, but eventually rose to become the King of Athens, and one of the more prominent figures in Greek mythology. This hero was called Theseus. [music]

The Background of Seneca’s Phaedra: The Theseus Myth Cycle

I recorded an 18,000 word piece on Theseus in my bonus series Rad Greek Myths – it’s in Volume 1, and it tells his entire story, so if you want the full Theseus saga, from his violent boyhood, to his meeting with his father Aegeus, to his journey to Crete, cooperation with Ariadne, and defeat of the minotaur, to how the Aegean gets its name, to his journey to the land of the Amazons, the inset story of his second wife Phaedra, and then his death, the tale of Theseus is bundled together with that of his counterpart Perseus on my Bonus Content page for $1.99. The next volume, which is related, tells the tale of Daedalus, another prominent figure in the stories surrounding the labyrinth of Crete. I understand you’re here for Seneca’s Phaedra, though, and for the purposes of understanding Phaedra, we just need to go over some basic parts of Theseus’ later biography.

Phaedra’s mother Pasiphaë fell in love with a bull on the island of Crete. The engineer Daedalus built a special statue that Pasiphaë could climb into so that she could mate with the bull. The painting is Jean Lemaire’s Daedalus and Pasiphaë (17th century).

The minotaur that Theseus killed was the half-brother of Ariadne and Phaedra. Their mother Pasiphaë, a fascinating figure in ancient mythology in her own right, was cursed to conceive a depraved passion for a beautiful white bull. The architect Daedalus created a hollowed out cow for Pasiphaë to crawl into, with her backside against the cow’s backside, the bull was released, and this was how Pasiphaë became pregnant with the minotaur.

We don’t know exactly what King Minos of Crete was up to during this famous act of bestiality – he was a busy conqueror with a large navy to take care of, so it’s easy to imagine he was away on a campaign. But when he returned, the Cretan king did not kill off wife’s his half human, half bull offspring. Instead, Minos had the architect Daedalus construct a labyrinth to house the minotaur.

Phaedra’s mother Pasiphaë gave birth to the Minotaur, afterward housed in a labyrinth on the island of Crete. Athenian youths were sacrificed to it, and Theseus was able to defeat the creature with help from Phaedra’s sister Ariadne. The painting is George Frederic Watts The Minotaur (1885), a human-handed and perhaps sentient version of the creature that looks off into a horizon, in contrast to some of the more monstrous ways the Minotaur has been depicted in art history.

This is where Theseus enters the story and becomes the star of the show. Theseus was the estranged son of Aegeus, King of Athens. Under Aegeus, Athens had killed the Cretan prince, lost a war with Crete, and then endured a recurring tribute of human sacrifice to Crete. When Theseus showed up at the Athenian court, however, and once Theseus became recognized as the Prince of Athens, Theseus made it clear that he would disguise himself as a sacrificial victim. He did so, and with the Cretan princes Ariadne’s help, he killed her half-brother the minotaur. Likely in fear of her family’s retribution, after the minotaur was killed Ariadne joined Theseus on his voyage home to Athens. But for unknown reasons, halfway there, he dumped her off on the island of Naxos, after, it is usually assumed, the two had become lovers.

Theseus then returned to Athens. His father, King Aegeus, had killed himself on the mistaken assumption that Theseus had died down in Crete, and so Theseus arrived in Athens to take up his father’s crown. Theseus’ reign, by many accounts, was either characterized by long periods of absence, violent purges, or both. The mythographer we call Pseudo-Apollodorus, roughly a contemporary of Seneca, writes that Theseus killed a fifth of his subjects who opposed his rule. Other sources attest that Theseus instituted Athenian democracy and then served as mostly a military ruler. A third possibility is the Theseus we meet in Sophocles’ Oedipus at Colonus – a benevolent and wise monarch who helped adjudicate the ugly situation at Thebes.

To list all the Theseus myths would take a long time, but to put it briefly, on the scale of heroes with generally benevolent and family-minded figures on one side, like Perseus, and violent, conceited scoundrels like Agamemnon on the other, Theseus falls in the middle and likely just a bit closer to the violent scoundrel side. At some point in his career, Theseus ended up on an expedition to land of the Amazons – a fabled territory to the northeast of the Black and Caspian Seas. There Theseus took it upon himself to kidnap the Amazonian queen, sometimes called Hippolyta, and others Antiope. Following his martial campaigns in the far northeast, Theseus brought the Amazonian queen back home to Athens and married her. The queen didn’t last long there in Athens – in some versions, including Seneca’s, Theseus himself kills her – but the queen survived at least long enough to bear Theseus a son – a son who is one of the central characters in the play we’re about to read. Theseus’ son by the Amazonian queen was called Hippolytus.

After enjoying Ariadne’s help, and perhaps her physical favors as well, Theseus cast aside Phaedra’s sister Ariadne on the island of Naxos on the way back to Athens from Crete. The painting is Evelyn De Morgan’s Ariadne in Naxos (1877).

Even more seriously, as the young Amazon prince Hippolytus grew up, Theseus and Pirithous made other poor marital decisions. Pirithous announced that he would marry Persephone, the queen of the underworld. Theseus, evidently wanting to preemptively one-up his friend’s bizarre resolution, abducted Helen of Troy when Helen was only a child with the intention of marrying her. Helen’s divine brothers Castor and Pollyx rescued her, though, and poor Helen was returned home. While divine intervention thwarted Theseus’ attempts at child abduction, Theseus nonetheless failed to learn the lesson of leaving ineligible spouses alone. He went with his friend Pirithous down to the underworld, the two beefcakes intending to carry out Pirithous’ mission of marrying Persephone. Persephone’s husband Hades, however, balked this ridiculous quest easily enough. Pirithous stayed a prisoner in the underworld forever, and it was only through the intervention of Hercules that Theseus was freed and brought back to Athens to continue his reign over the Athenians.

The stories of Theseus’ early life are a briar patch of sometimes contradictory yarns that generally paint a portrait of a brawny, but scatterbrained and egotistical adventurer who may have never been fit to be a king. I wanted to tell you these stories before introducing the tale of Theseus and Phaedra, because the mythological background is important to understanding the situation that Phaedra walked into when she married the middle aged and morally suspect King of Athens. In this myth cycle so far, Phaedra has remained in the background. One of Minos and Pasiphaë’s many children, she would have known of her mother’s coupling with a bull, and her grotesque half-brother’s acts of cannibalism. She would have known of her sister Ariadne’s treachery against the kingdom, and perhaps also that Ariadne had been abandoned by Theseus. For many reasons, then, Phaedra seems like an unlikely person to marry Theseus. Anyone who knew anything about the Athenian king could not have forecast happiness and fulfillment for the poor Cretan princess, whose groom was so inclined to treating women as disposable and perhaps even laying waste to his own subjects.

So the situation at the outset of Seneca’s play Phaedra is as follows. Phaedra has been married to Theseus for some time. She is his second or third wife – we don’t know if Theseus ever formally wed Phaedra’s sister Ariadne, although he certainly wed the Amazon Queen who’d born him Hippolytus. Hippolytus, the prince of Athens, is likely in his late teens or early twenties – old enough to be sexually desirable to his stepmother Phaedra. But Hippolytus, to the dismay of Phaedra and all those who expect him to take a conventional path, shows interest in little except for hunting and the outdoors. Having inherited, maybe, the regal wildness of his Amazon mother, Hippolytus is fiercely independent, and it is perhaps precisely the young man’s chilly, morally pure self-sufficiency that attracts his stepmother to him, as Theseus himself is so compromised and freighted with emotional baggage.

Well now you know the three named characters in Seneca’s Phaedra – the husband, Theseus; the stepmother, Phaedra; and the son, Hippolytus. As the play opens, Theseus is down in the underworld trying to help his friend Pirithous kidnap Persephone, and Phaedra and Theseus are in Athens. And with this background, we’re ready to dive into this important play. Unless otherwise noted, I’m quoting from the Emily Wilson translation, published by Oxford in 2010. [music]

Seneca’s Phaedra, Act 1

Hippolytus, the son of King Theseus of Athens and an Amazonian queen, was a strong, beautiful, austere young man. One morning, he stood in the palace with a company of his huntsmen and hunting dogs, and surveyed his companions. It was to be a day spent outdoors, as all of Hippolytus’ days were – and he directed his various companies of hunters to spots on the Greek mainland. They would scatter widely over the countryside around Athens and beyond – over white capped peaks, and down into lush valleys where flowers breathed in the scent of the west wind. They would hurry down into ravines, past swift moving rivers, and make their way carefully along high crags. And they would hunt wild sheep, and boars, birds, oxen, and larger, fiercer animals, still. Their dogs, a force of nature in their own right, would lead a victory procession afterward with bloodied muzzles. And at the end of a long speech to his hunters, Hippolytus concluded, “Come, Goddess, show me your favour!. . .I am called to the woods. / This way, this way, I shall go / where the path makes a long journey short” (81-4).5Hippolytus’ speech before departing was full of boundlessness – of visions of distant slopes and churning water – the excitement and adventure of unbridled exploration. Once he wandered offstage, though, his stepmother Phaedra appeared and gave quite a different speech. First, Phaedra described the ships of her homeland – Crete. So many ships, Phaedra said, disembarked from Crete to range all over the world – anywhere there were oceans. And Phaedra asked her homeland of Crete,

Why do you force me to spend my life in tears and pain,

given as hostage to household gods I hate, and married

to an enemy? See, my husband has run away. He is gone.

Theseus shows his bride his usual faithfulness.

What a hero! (89-93).

It was digust, rather than heartache, that Phaedra felt toward Theseus, her husband who was at that point in the depths of the underworld, trying to help his friend seek out forbidden love and sex. But all the same, Phaedra did feel heartache – a swollen, burning, volcanic pressure that kept her from all the normal course of things that Athenian women did. She had no interest in temples, devotional sacrifices or rituals, nor weaving and the staid rites of the goddess Athena. Phaedra wanted wildness and animalism. She wanted to hunt. Drawing a parallel between herself and her mother Pasiphaë, Phaedra admitted,

what I like is to rouse wild beasts, and chase them, and hunt them down,

and to hurl stiff javelins from my soft white hand.

Where are you going, my soul? Mad thing, why yearn for the forest

I recognize the fateful trouble of my poor mother.

For us, my mother and me, love means sin in the woods.

Mother, do you pity me? Unspeakable evil

seized you, and rashly you fell in love with the savage leader

of a wild herd. (109-17)

Phaedra said that she had all the misguided lust of her mother, and no help; further, that the women of Crete were doomed to such gross and improper fervors.

Phaedra’s nurse was there listening. The other woman told her that it wasn’t too late to live a decorous life. Phaedra could still quench the flames of her sexual desires. In a passage that could have come from Seneca’s Letters to Lucilius, Phaedra’s nurse told the queen, “Whatever will be, whatever fortune sends. . .bear it” (137). And her nurse continued, in the Penguin E.F. Watling translation,

To choose the good is the first rule of life,

And not to falter on the way; next best

Is to have shame and know where sin must stop.

Why, my poor mistress, why are you resolved

To heap fresh infamy upon your house,

With sin worse than your mother’s? Wilful sin

Is a worse evil than unnatural passion;

That comes by fate; but sin comes from our nature. (139-44)6

Just because Theseus was at that moment on a quest in the underworld, the nurse said, did not mean that Phaedra was free to do whatever she wanted. Even if Phaedra could get away with adultery, the nurse argued, Phaedra would still suffer the awful pangs of her own conscience. Phaedra could not share a father’s bed with his son, said her nurse – women of Crete, like Pasiphaë, had already given too much free reign to their perverse desires, and the abomination that had been the minotaur was already too much.

Phaedra considered what her nurse had said and admitted that the other woman’s reasoning was sound. Nonetheless, Phaedra said, in the Frank Miller prose translation,

I know, nurse, that what [you say] is true; but passion forces me to take the worser path. With full knowledge my soul moves on to the abyss and vainly seeks the backward way in quest of counsels sane. Even so, when the mariner urges his laden vessel against opposing seas, his toil goes for naught and the ship, vanquished, is swept away by the swift-moving tide. What can reason do? Passion has conquered and now rules supreme, and, a mighty god, lords it [over] all my soul.7

She could do nothing, Phaedra said. Cupid could control the whims of Jupiter, Mars, Vulcan, and Apollo – what could she possibly do against the god of love? Phaedra’s nurse disagreed. There was no god of love, said the nurse. Cupid was a fiction – an excuse that people used to justify their basest impulses. People who had too much finery, said the nurse, only sought further finery. The nurse reminded Phaedra that Phaedra was a queen. The nurse said, “Those who have too much power want no limits on their power. . .Think what befits you” (215-6). And the nurse reminded Phaedra that Theseus would be back.

Phaedra wasn’t so sure. No one came back from the underworld, she said. But the nurse countered, advising Phaedra to have confidence in her husband. Phaedra said that if Theseus could descend to the underworld and come back by forbidden paths, then perhaps he’d understand her unconventional passions. The nurse was doubtful. Theseus, the nurse reminded Phaedra, had killed his previous wife – a chaste Amazonian woman. And further, Hippolytus himself had all the sexless austerity of the Amazons in him, shunning women and marriage. At the mention of Hippolytus, Phaedra lost her composure – she wanted Hippolytus – she’d crawl through snow for him and jump down barefoot onto crags. The nurse remained dubious. She asked Phaedra why Hippolytus would put aside his dislike of women to go to bed with his stepmother, of all people. And in a passage featuring stichomythia – that rapid back and forth dialogue for which Seneca was so well known and which influenced renaissance drama, Phaedra and her nurse argued about Phaedra’s stepson. Here’s the Frank Miller prose translation of some fantastic back-and-forth, starting with Phaedra, then the nurse, then Phaedra, and so on.

PHAEDRA: Wild is he; but wild things, we have learned, can be [overcome] by love.

NURSE: He will flee away.

PHAEDRA: Though he flee[s] through the very seas, still will I follow.

NURSE: Remember [your] father.

PHAEDRA: My mother I remember too.

NURSE: He shuns the whole race of women.

PHAEDRA: Then need I fear no rival. (240-6)8

The nurse warned Phaedra that Theseus would come home. Phaedra said that Theseus was no moral paragon – at that very moment he was trying to help his friend steal someone else’s wife. The nurse warned Phaedra that Phaedra’s father would come. Fine, Phaedra said – old King Minos of Crete had let his daughter – and Phaedra’s sister – Ariadne abscond the island with Theseus. In the end, the nurse begged Phaedra to check her reckless passion, and Phaedra said she would try. She would take her life – it was the only way.

Her nurse remonstrated, but Phaedra calmly enumerated the ways she might take her own life – hanging – falling on a sword – perhaps jumping from a great height. And then, seeing the fact the only way to save Phaedra’s life was to help the stepmother seduce her stepson, the nurse changed the tenor of her rhetoric. The nurse said, in the Penguin E.F. Watling translation,

[H]ear me: is your heart heavy

With this immoderate passion? Then ignore

The tongue of reputation. Reputation

Takes no account of truth; it often harms

The innocent, and treats the guilty well.

This is what you must do, try out the strength

Of that perverse austerity. I’ll do it;

I’ll speak to the young savage presently

And bend the stiffness of his stubborn will. (267-72)

It’s an interesting moment in Seneca’s play – the moment at which the nurse goes from being the block to Phaedra’s illicit passion to actively enabling this passion, and we wonder indeed if maybe Phadra would have merely continued to impotently moon over young Hippolytus without her nurse’s sudden turnabout. In any case, the Senecan chorus began its song to wrap up the act.

The chorus sung of the pernicious power of Cupid’s arrows, ignoring what the nurse had earlier said about the chubby god of love being a myth. Cupid, the chorus sung, ripped the world apart with his arrows and pulled the gods down from the heavens. Phoebus and Jupiter had done strange, disgusting, desperate things on behalf of their passions. Cupid’s arrows had undone Hercules and they could pierce to the blackest depths of the ocean. Even docile animals – bulls and deer and elephants, were filled with the destructiveness of passion. Nothing could resist the torrent of love’s power, the chorus concluded, adding in a closing pair of lines, “What more can I say? Love conquers / even the fiercest creatures: stepmothers” (356-7). [music]

Seneca’s Phaedra, Act 2

Act 2 sees the crucial meeting in which Hippolytus finds about his stepmother’s feelings. The painting is Jozef Geirnaert’s Phaedra and Hippolytus (1819).

Phaedra, decked in silk and jewelry, suddenly said she wanted none of it. She wanted no perfumes or pearls or elaborate hairstyles any more. She wanted loose, wind-blown hair, and a quiver and a spear. She would dress like an Amazon, and ride into the woods. Phaedra’s nurse did not advise her to do otherwise. On the contrary, the nurse prayed to the goddess of magic and witchcraft, Hecate, to help them soften the resolution of Hippolytus and make the arrogant youth feel the love that his stepmother felt for him. Just then, the nurse saw Hippolytus praying to a statue. Side note, by the way – no stage directions survive from Seneca’s plays, and so we can perhaps assume that this is a sacred statue somewhere in the palace, perhaps stage left or stage right from where Phaedra has risen from her sofa. Anyway, the nurse spotted Hippolytus praying to his preferred cult statue, and Hippolytus saw the old woman looking at him.

Young Hippolytus asked the nurse why she had trekked out to see him and his cult statue, wondering whether everything was alright. The nurse said certainly, everything was fine – her only worry was Hippolytus himself – the young man was far too austere and drove himself along too arduously. He lost much of life in asceticism. The nurse said Hippolytus ought to be having fun. He should be drinking and carousing, and enjoying the pleasures of Venus. Instead, he spent his weeks in chilly discipline, begrudging himself the normal joys of youth. Without Venus, the nurse said, the world would be silent and unpopulated. Hippolytus ought to follow the dictates of his natural impulses.

Hippolytus, unsurprisingly, was not swayed by the nurse’s entreaties. He said he would give up his free, sinless life for nothing. Articulating some of the principles of Senecan stoicism, Hippolytus said, in the Oxford Emily Wilson translation:

Anger, lust, and greed do not set fire to the heart

of the innocent man whose home is on the mountain tops.

The winds of the faithless mob leave him unswayed,

unmoved by their perverted hate and brittle love.

He is no slave to established power, wants none for himself.

He does not pursue the futile goals of fame or fleeting wealth.

He is free from hope and free from fear. Black, biting envy

does not pursue him with mean grasping jaws. (486-93)

The innocent, Hippolytus continued, didn’t need to equivocate, or grasp for riches, or make lavish sacrifices. Instead, he wandered the wilds, hunted and trapped, bathed in snowmelt, slept with his head in the grass. Eschewing the finery of the court, said Hippolytus, the innocent man ate wild fruit and drank clear water from his cupped hands. Hippolytus said that this was how men once lived in an earlier epoch. They had lived simply, ignorant of wealth, warfare, and long oceanic expeditions, and eating the natural bounty of the earth.

Hippolytus then went on to tell the Ages of Man story – that story of a descent from gold to iron that seemingly every single ancient Mediterranean poet told. From their early utopian past of living simply and enjoying natural bounty, said Hippolytus, humanity had grown violent and warlike, and families turned on one another, and amidst the murders of parents by children and children by parents; husbands and wives at one another’s hands, “I will not talk of stepmothers – beasts are more kind” (558). Women, Hippolytus added, were the root of all malevolence – the catalysts of wars, enslavements, sieges and the ends of kingdoms. He concluded his long speech with a resolution that is as follows in the Frank Miller translation:

I abominate. . .all [women], I dread, shun, curse them all. Be it reason, be it instinct, be it wild rage: ’tis my joy to hate them. Sooner shall you mate fire and water, sooner shall the dangerous [waters] offer to ships a friendly passage, sooner shall [dusk] from her far western shore bring in bright dawn, and wolves gaze on does with eyes caressing, than I, my hate o’ercome, have kindly thought for woman. (566-73)

Now, this isn’t exactly an ambiguous position to take. Other listeners, hearing Hippolytus’ unequivocal disinterest in love and sex, might have returned to Phaedra and suggested that she look elsewhere for her prospective fling, or maybe even take up swimming or pottery. Phaedra’s nurse, however, steered the course. She reminded Hippolytus that even the Amazons had sex – Hippolytus himself was proof of that. And Hippolytus replied with a memorable riposte. He said, “My only comfort for my mother’s death, / is that I am now permitted to hate all living women” (578-9).

These words, at last, shook up the nurse’s resolution. Phaedra approached the scene of the conversation just as the nurse was reeling with uncertainty. But seeing Hippolytus there, Phaedra determined to say what she had to say to Hippolytus. After confirming that no one was around to hear other than Hippolytus, Phaedra temporarily found herself at a loss for words. But then, slowly working herself up to it, and wincing when Hippolytus called her “mother,” Phaedra said that she would do anything for Hippolytus. And she said that Theseus, in all likelihood,would never return from the underworld, and that Hippolytus would have to pity his father’s widow.

Hippolytus said that if there were any justice in the world, Theseus would return to them. But if indeed the king was gone, Hippolytus said, Phaedra could count on him to be a father figure to her. At this Phaedra winced again. Hippolytus asked her what was amiss. Phaedra replied, in the Penguin E.F. Watling translation, “Madness is in my heart; / It is consumed by love, a wild fire raging / Secretly in my body, in my blood, / Like flames that lick across a roof of timber” (640-4). Hippolytus, obviously clueless, asked if she were talking about her love for Theseus. Phaedra said yes – in a way – she was thinking of Theseus when he was young – when he was firmer and brighter – in fact, when he looked like Hippolytus himself. As a matter of fact, Phaedra added, Hippolytus was better looking than Theseus ever was – he had the beauty of the Greeks and the Amazons together. And then, Phaedra cast her die. She said to Hippolytus, in the Emily Wilson translation,

Look, I beseech you,

begging at your knees – a royal princess,

I am untainted, pure, untouched by stain, and chaste:

only for you I changed. I have stooped to prayer, and I know

this day will end my pain, or end my life.

Have mercy on me. I love you. (666-71)

This, finally, got through to Hippolytus. He realized what was going on, and his response, predictably, was not reciprocal passion. Quite the opposite. Hippolytus called on Jupiter to strike the earth with lightning. Hippolytus himself wanted to be struck by a bolt – he was befouled by his stepmother’s lust. Phaedra, said Hippolytus, was worse than her mother Pasiphaë – while Pasiphaë had only fouled herself and the bull that had impregnated her, Phaedra had pulled her stepson underneath the ugly umbrage of her lasciviousness. Phaedra, said Hippolytus, was even worse than Medea.

Phaedra was steadfast in the midst of her stepson’s condemnations. She would follow him anywhere, she said, and was still kneeling before him. Hippolytus seized her by the hair and prepared to kill her with a sword – yes, said Phaedra – this was even better – she would die unpolluted. But Hippolytus refused. He threw away the sword that he had been prepared to kill her with. Rivers, and even the great ocean, could not clean him from the taint with which she’d sullied him. With these words, Hippolytus exited the stage.

Phaedra’s nurse, still, evidently, on the scene, began thinking quickly. Phaedra was doomed now, unless they acted fast. The nurse began shouting. Hippolytus had assaulted them, she said! Hippolyus had tried to rape them – and there was the cruel young man’s sword, left behind. Phaedra’s countenance and her torn hair offered evidence to the allegations – the nurse told all present to spread word of the crime, and told Phaedra to rouse herself – Phaedra was innocent, at least.

With this, Phaedra and the nurse left the stage, and the chorus was left alone again to philosophize. Phaedra, they said, was a storm. She was as beautiful as the moon, and Hippolytus was beautiful, too, but beauty, they said, was transient. It faded with age, and in distant forested places, was vulnerable to the assaults of nymphs and satyrs. Hippolytus, the chorus said, so majestic, and so masculine, was nonetheless imperiled by the same forces that imperiled all human beauty, and Hippolytus would be lucky if it were age that stole his good lucks, and not something far worse. [music]

Seneca’s Phaedra, Act 3

The chorus, as Act 3 opens, is onstage, and begins by offering some exposition. Phaedra, the chorus said, was planning a dreadful crime – with all the powers of deceit that she possessed. Yet in the midst of describing this impending crime, the chorus paused. Someone new had arrived – a pale man with a gaunt face and matted, filthy hair. It was Theseus. He had returned from the underworld. He had been down in the depths, he said, for four years – so long that his eyes could scarcely tolerate the light. Hercules, he said, had saved him – but he’d left his strength and vigor in the underworld forever. Theseus, though his senses were dulled, was suddenly conscious of something amiss in Athens. He asked what it was he was hearing – far off crying? Was it real, or just an echo of his long exile in Hades?Phaedra’s nurse explained. Phaedra, said the nurse, was on the verge of suicide. She was not elated that her husband had returned, but instead petrified. Theseus was puzzled. Phaedra, the nurse elaborated, had a dark secret – one that she planned to die with. Theseus couldn’t believe it. He demanded that the palace doors be flung open, and when they were, he saw his estranged wife, a sword, indeed, in her hand. Phaedra said she wanted to be left alone to die. And in another scene featuring some of Seneca’s influential stichomythia, Phaedra and her husband Theseus went back and forth with some intense dialogue. This is an older translation in Elizabethan English, done by Ella Isabel Harris. Theseus said,

THESEUS: What reason urges thee to die?

PHAEDRA: [Phaedra replied] The fruit of death would perish if its cause were known.

THESEUS: None other than myself shall hear the cause.

PHAEDRA: A virtuous wife dreads but her husband’s thoughts.

THESEUS: Speak, hide thy secret in my faithful breast.

PHAEDRA: That which thou wouldst not have another tell, tell not thyself.

THESEUS: Death shall not have the power to touch thee.

PHAEDRA: Death can never fail to come to him who wills it.

THESEUS: Tell me what the fault [t]hou must by death atone.

PHAEDRA: The fault of life.

THESEUS: Art thou not affected by my tears?

PHAEDRA: The sweetest death is one by loved ones mourned.

THESEUS: Thou wilt keep silence? Then with blows and chains [t]hy aged nurse shall be compelled to speak. (871-83)9

Phaedra, however, spoke first. She had suffered an assault, she said. And, drawing out Hippolytus’ sword – a sword which had once been Theseus’, she indicated that the rapist had been Hippolytus. Theseus was sickened. Their family blood, he said, had been tainted by blood from the distant east. “That madness,” he said, “is typical of the warrior race: / first despising sex, then whoring out / that long-preserved virginity” (909-11). Theseus thought of his son with increasing disgust. The young man had been so proud and arrogant – such a romantic wanderer on the heights, but his solitary nobility had been a farce. Theseus said he was glad he’d killed Hippolytus’ mother – otherwise, perhaps, Hippolytus would have tried to seduce her.

Hippolytus could run, said Theseus – he could run far off – to the far and icy reaches of the north, but Theseus would find him. He said that he would pray to his divine father Neptune that Hippolytus would not live out another day. And yet the waves remained still, and no winds churned to rip the stars down from the sky. The chorus, at this point, took to the stage to end the scene. Why, the chorus asked, did nature lavish such attention on the seasons? Why did winter take exquisite care to line trees with frosts and pour shadows into forests? Why did summer warm the wheat fields? Why did the world turn in such a vast orbit, and leave mankind so often neglected and forgotten? And in a closing lament, the chorus, voicing lines that are part stoic isolationism and part pure despair, said in the Oxford Emily Wilson translation,

Fortune rules chaotically over human life

she scatters her gifts without looking, preferring the worse.

Wicked desires win, good people lose,

deceit is king in the lofty palace.

The people give power to corrupt politicians,

they cultivate people they hate.

Self-discipline and goodness win no prizes.

Poverty afflicts the faithful husband,

while crime helps lecherous cheats to gain control.

Chastity is useless, a false idol. (979-88)

Seneca’s Phaedra, Act 4

Theseus remained onstage, perhaps glowering and stalking, and he was joined by a messenger. And as is often the case in premodern tragedy, this messenger had a long and grim story to tell. The messenger got straight to the point. Hippolytus, said the messenger, was dead. Theseus said Hippolytus had already been dead, as far as he was concerned, but nonetheless asked for the details. The messenger told his story.

Hippolytus, dragged to death behind his chariot after a tsunami and oceanic bull frighten his horses. The painting is Lawrence Alma-Tadema’s The Death of Hippolytus (1860).

The oceanic bull charged Hippolytus, but the young man was unafraid. Suddenly Hippolytus’ horses lost their composure, though, and he tried to keep control of his chariot. The giant bull menaced the chariot and its horses and driver and Hippolytus tried to keep control. But in the end, Hippolytus’ horses were too terrified by the apparition from the ocean. The young man was thrown from his seat. He tumbled into a tangle of reigns and ropes. And his suffering thereafter was awful. Dragged, torn, and broken by the speeding chariots, he was finally impaled by a burned branch, leaving behind him a gory trail.

Theseus, hearing of his son’s excruciating death, could not help but mourn Hippolytus. And Theseus said, “I think the pinnacle of misfortune / is to be forced by chance to want things one should loathe” (1119-20). Hearing Theseus philosophize on the death of his son, the chorus took the stage to close out Act 4 with their thoughts on the events that had unfolded so far.

The meek, said the chorus – the meek and the humble, who lived in huts – they didn’t suffer the buffetings of fortune as much as prominent and ambitious people. Analogously, thunder struck the high places, and not the low. A dark symmetry had unfolded that day, said the chorus, because having been deprived of Theseus, the underworld now had his son, Hippolytus. [music]

Seneca’s Phaedra, Act 5

There was weeping in the palace, the chorus said – and Phaedra was dashing around with a sword in her hand. Theseus, seeing his wife thus armed, demanded to know what she was doing. Nearly mad with grief, Phaedra told Theseus that he always brought death and destruction with his coming. And Hippolytus, said Phaedra – beautiful Hippolytus was dead. She would die, Phaedra said – she would die to avenge Hippolytus’ death, and join him in the underworld. She could not go back to the life that she’d lived marred by the guilt of her beloved’s death. Death alone would deliver her from her insurmountable sadness and shame. And then Phaedra told the truth. She said, in the Penguin E.F. Watling translation,. . .O Athens; hear this, father –

But more malevolent than any stepmother –

I told you lies, alleged untruthfully

The offence on which my own mad heart was set.

You, father, punished where there was no need.

The innocent boy, charged with inchastity,

Lies dead, untouched by sin, untouched by shame.

Hippolytus, be vindicated now!

My guilty breast awaits the avenging sword. (1191-7)

And with these words, it is generally assumed, Phaedra killed herself. (We’re not sure, as there are no stage directions.) Theseus, finally understanding the calamity that had unfolded, said he should have never come up from Hades, and wished to be covered by the dark waters of the underworld’s rivers. Or, failing that, he wished the vast oceans would subsume him in their depths.

Theseus had once, as a youth on the way to Athens, trekked along the Peloponnese, killing bandits in various abominable ways, and wondered what sort of violent retribution he himself deserved. He deserved the punishment of Sisyphus, and that of Tantalus – to have his liver ripped out like Tityos, to be spun on a wheel of fire, like Ixion. Envisioning all of these punishments, Theseus begged the gods to let him die, but found that they would only help him commit crimes.

The chorus counseled Theseus to at least get control of himself long enough to bury his son, and Theseus gathered up the beautiful young man’s mangled remains and held them close. Poor Hippolytus had been torn to pieces, and Theseus gently set them together in the way they’d once been – the boy’s strong left hand, which had controlled the reigns of his horses, and another part which was torn beyond recognition. There were missing parts, said Theseus, scattered along the place the young man had fallen from his chariot – multiple burials would be needed. And he concluded, in the Emily Wilson translation,

Open the house: it stinks of death. Let all the land

of Attica ring loud with piercing funeral cries.

You, make ready the flame of the [funeral] pyre,

and you, go out and seek the missing parts of the body

scattered in the country. And as for [Phaedra] – bury her,

and may the heavy earth crush down her wicked head.

And that’s the end. [music]

Seneca’s Phaedra, 5th Century Athenian Drama, and the Lost World of Roman Tragedy

The play that you just heard, performed in the northwest of France in 1484, and then again in Rome in 1485, was one of the main catalysts of Renaissance drama. Seneca’s intense and tightly focused tragedy on a stepmother’s lust for her stepson, with its extreme rhetoric, and its window into the volatile world of human passions, invited European dramatists of the 1500s and 1600s to write plays in which ferocious confrontations brought out the lowest depths of human depravity. While Seneca was dismissed in subsequent centuries as an undisciplined hack, it was precisely the darkness of his plays, and the amplitude of his rhetoric that drew Shakespeare’s generation to the Roman tragedian’s work. As Polonius puts it in Shakespeare’s Hamlet, “Seneca cannot be too heavy” (2.2.368). In other words, the excess, and the bombast of the earlier Roman dramatist were what made him magical and mesmerizing to the early modern period. While Seneca was European drama’s ancient tragedian par excellence for perhaps two centuries, and while today his reputation as a dramatist is on the rise once more, for most of the two thousand years we’ve been reading Seneca’s tragedies, they’ve been disparaged as inferior to the Greek drama that came before them and the European drama that came after. I want to talk for a bit about why that is.Seneca, like all Roman writers, really, has often been considered a middling imitator of the Greek authors who predated him. With few exceptions, so the story goes, Greek tragedy has a solemnity and composure, a self control and sense of universal order, and moreover a formal melodiousness that Seneca’s lacks. The endings of Greek tragedies offer moral orientation, even if the lesson is so often a monotonous caution against hubris; the endings of Senecan tragedies, on the other hand, are bloodbaths that seem to break off in midsentence with no effort at moral instruction. While the intrinsic features of Seneca’s plays have long been criticized, Seneca’s historical reputation as an avaricious hypocrite and his role in the courts of the Julio-Claudians have hardly helped the prestige of the plays that he left behind.

We have eight tragedies from Seneca, and in most cases we have classical Greek analogs for each. Seneca’s Oedipus is often set alongside Sophocles’ play of the same title. Seneca’s Phoenissae deals with the aftermath of Oedipus’ tragedy, as does Aeschylus’ Seven Against Thebes, and Seneca, like Aeschylus, wrote a play about the Homeric Greek king Agamemnon. Most of all, Seneca followed the path of classical Athens’ most influential tragedian, Euripides. Both dramatists wrote plays about Hercules, and Medea, and Thyestes, and the Trojan Women. And both wrote plays about Hippolytus and Phaedra.

Let’s talk about Seneca’s and Euripides’ version of the Phaedra story. Euripides’ play Hippolytus is a tragedy covering the same characters and events as Seneca’s Phaedra. It was an old story. Lusty wives who pursue forbidden men and then accuse these men of rape appear in various places and times in the Ancient Mediterranean – the Ancient Egyptian “Tale of Two Brothers” which appears in a manuscript from the twelfth century BCE, tells this story. So does the tale of Bellerophon, pursued by a lusty queen named Anteia who later accuses him of sexual assault. And perhaps most famously, late in Genesis, young Joseph is sold to a master named Potiphar, whose wife makes sexual advances on Joseph, and later tells everyone that the young slave has tried to rape her. There are different lessons that can be extracted from this archetypal tale, and Euripides takes a pretty different path than Seneca.

This frescoe from Pompeii depicts Phaedra dazzled by a none-too-subtle display of full frontal nudity from her stepson. Seneca himself might have seen the frescoe, but authors had been devoting themselves to the tale of Hippolytus since Euripides back in 428 BCE.

I think we can enjoy the works of classical Athens and the tragedies of Seneca for different reasons. I personally read Senecan tragedy prior to reading ancient Greek drama – I’d had a seminar on Shakespeare one spring semester and was piqued that so many footnotes kept coming up referring to various Seneca plays, and so that summer I got the old Penguin E.F. Watling translation I quoted a couple of times in this and the previous show and read it cover to cover. When I read Greek tragedy a few years later, it was never with a sense that Euripides and his contemporaries were somehow more majestic and profound than Seneca, but rather that Seneca was from a more cosmopolitan and heterodox place and time – that his aim was not so much to communicate a sense of civic order anchored in orthodox polytheism as it was to explore some of the extremes of human experience.

When we compare Seneca to Eurpides and company, it’s a bit like comparing 1990s grunge music to 1950s doo-wop – not to parallel either author to either musical genre. What I mean is, the styles are very different, and we can say a lot about their differences. But grunge wasn’t really responding to doo-wop. A whole parade of genres and works had existed in between them – folk rock, 60s psychedelia, metal, prog rock, punk, post punk, glam rock, new wave – a succession of five decades of evolutions that all went into the birth of grunge music in the 1990s. Between Seneca and Euripides there weren’t five decades, but five centuries, and over the course of those five centuries, all sorts of tragedies were being written. To quote scholar Christopher Trinacty,

Recent work has highlighted that Seneca’s literary antecedents were primarily Roman and that the Greek works that did contribute to Seneca’s concept of tragedy were probably Hellenistic and not the tragedies of fifth-century Athens. Republican tragedies by Ennius and Accius were vital intermediaries to Seneca’s dramaturgy, as were his famous Augustan precursors: Ovid’s Medea and Varius’ Thyestes. Seneca’s Medea is more indebted to the various representations of Medea found in the works of Ovid than to Euripides’ play, and his Hercules Furens can be seen as a response to the Aeneid rather than to Euripides’ dramatization of the myth. The detailed commentaries to the plays, however, do indicate numerous potential intertexts to the Greek sources, and one should not put possible moments of [emulation] past Seneca.10

So, when we compare Seneca to Euripides, or Sophocles, or Aeschylus, while we can be confident that Seneca likely was familiar with their works, we sometimes forget that Seneca knew a whole lost history of Ancient Mediterranean tragedy that’s no longer extant. As we saw in prior episodes, through Menander and then Plautus and Terence, we now possess some links in the chain that stretches between, say, Aristophanes and Horace’s Satires – not many links, but at least some samples of Hellenistic period comedy. Between Euripidean tragedy and Senecan tragedy, though, nearly nothing survives. For whatever reason, the tragic works of writers like Ennius, Accius, Varius, and Ovid, famous and in circulation at the beginning of the first century CE, were not ultimately selected for preservation. And while classics is a more finite field than, say, my own period of nineteenth-century Anglophone literature, when we consider all the tragic works written between the end of the Peloponnesian War in 404 BCE and the death of Seneca in 65 CE, and realize that from this huge period we have a miniscule eight plays – all by Seneca himself, we’re invited to remember that antiquity produced a mountain of literature, and we only have a few dozen of its rocks. [music]

Stoic Philosophy, Senecan Tragedy, and Sublimation through Rhetoric

Before we leave Senecan tragedy, I want to talk a little bit more about stoic philosophy and the plays that Seneca left behind. As we’ve learned in prior episodes, once, readers believed that Seneca the philosopher and Seneca the playwright were different figures. The philosopher believed in an orderly universe governed by divine reason; moreover, in the stoic sage’s capacity to be unassailable within his self-reliant shell of rationality. The tragedian wrote volubly of lust, vengeance, rape, dismemberment, and incest. Why would such a staid and restrained intellectual write such gory, prurient plays? Why would Rome’s most prominent stoic moonlight as the impresario of a bunch of bloody and nihilistic operas?

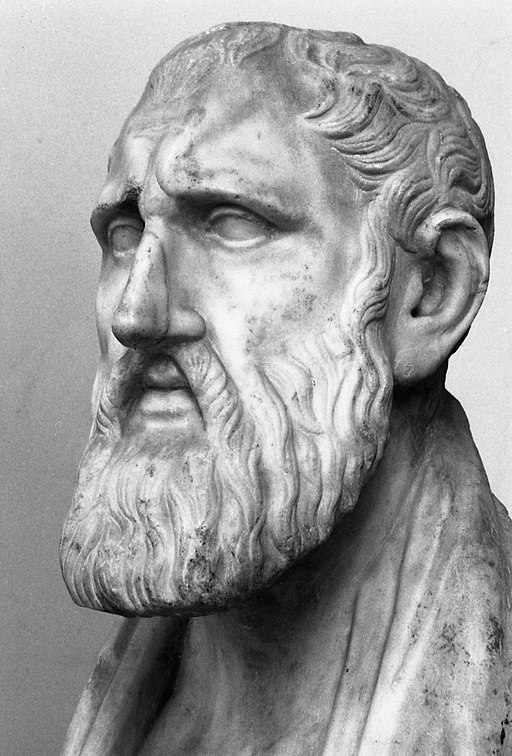

Zeno of Citium (c. 334-262), stoicism’s founder, might have scrunched up his lips at the lavish rhetoric of Senecan drama, but Seneca was clearly trying to work out stoic themes in Thyestes and Phaedra – especially in choral interludes and in scenes in which palace hirelings try to dissuade out-of-sorts aristocrats to temper their passions. Photo by Paolo Monti.

The simplest explanation for Senecan tragedy is that the life Seneca ended up living did not, particularly, suggest to him that a benificent providence was at the helm of the cosmos. In On Anger, Seneca might calmly pinpoint the dangers of excessive emotionality; in his later moral epistles, Seneca might avow his steadfast dedication toward stoic principles. But year after year, under the Julio-Claudians, Seneca came to understand that the world at large did not practice the philosophy that he preached. The tragedies, then, are at a simple level a sort of spillway for Seneca’s frustrations with what he saw around him in the Roman world. Caligula and Nero might have been capable of abhorrent things, but in his plays, Seneca could do far worse, creating villains that made even the basest evils of the Julio-Claudians seem drab and prosaic. The rulers and aristocrats of Rome, half a century after Augustus’ marriage legislation, might have hurled themselves into licentious excess with an army of sex workers – slaves, prostitutes, and courtesans, but Seneca could write plays that revealed passion at its most incestuous and destructive. His philosophy, in short, promulgated an optimism that he did not find evidence for in the world around him, and his tragedies can be understood as a reactive scream in frustration.

Shortly before the end of the play Thyestes, the chorus wonders, “Will the last days come in our time? / We were born for a cruel lot. . .we, poor things, have lost the sun” (878-90). As biographer Emily Wilson writes, “Seneca has a far stronger obsession than any Greek tragedian with the possibility that the whole universe may be at a point of crisis, and a far greater interest in transgression and physical disgust.”11 His pessimism was perhaps the pessimism of a generation – the generation of Seneca and Peter and Paul and Christ in the Roman world. This generation, weaned on the Pax Augusta and the Augustan Age, had their own distinct experience of decline from a golden age. The narrative of a fall from a lost utopia is one of the most common stories in the Ancient Mediterranean, as we’ve heard again and again, but Seneca’s generation, especially those who lived in the capital, watched their polity’s executive leadership steadily decline from the brilliant first emperor to the clownish and yet mortally dangerous Nero. Augustus, they knew, was in the rear view mirror, as were Ovid and Virgil, and before them Caesar and Cicero. To a literary culture already inclined to various theories of social degeneration, the reigns of Caligula and Nero must have seemed ample evidence that a great past was gone, and modernity meant suffering in the claustrophobic meaninglessness of autocracy. Centuries before, Aeschylus’ play The Eumenides, staged as the great Athens-led Delian league was reaching its ascendancy in the spring of 458 BCE, celebrated Athens’ new law courts and the rise of a fairer criminal justice system. This, to put it mildly, was not Seneca’s world, and so perhaps we shouldn’t fault Seneca for omitting the moralizing or the tempered optimism of his ancient Athenian forebears.

One answer, then, to the question of why Seneca the philosopher was also Seneca the tragedian is that his plays were an outlet for the anger and the pessimism that his philosophy told him were impermissible. Another answer, though, and I think a richer one, is that Seneca’s plays are actually full of explorations of stoic themes. Thyestes and Phaedra can easily be read as cautionary tales about giving way to the extremes of vengeance and desire. If the garden variety fifth-century Athenian tragedy showed character after character falling victim to hubris against the gods and prophecy, Seneca’s cardinal sin is passionate excess, and it’s possible to read his tragedies as works that anatomize this transgression in all sorts of ways.

In the two Senecan tragedies we’ve read, ideas from Senecan philosophy pop up often in cautionary speeches made by minor characters – most commonly in advice given to Atreus by his attendant in the play Thyestes, and then early cautionary remarks given to Phaedra by her nurse that we read in this episode. The wise unnamed characters of these two Senecan tragedies, as well as the choruses, are humble proponents of moderatism. While these second string figures are ignored and overruled, their admonishments to each play’s central figures nonetheless form philosophical counterpoints to Atreus’ thirst for vengeance and Phaedra’s desire to seduce her stepson.

Let’s look at a couple of examples of Senecan stoicism popping up in Thyestes and Phaedra, starting with Thyestes. The chorus of Thyestes is often appalled at the increasingly grim events of the play. In the speech that closes Act 2, the chorus proclaims that in contrast to the volatile Atreus, “A king is a man without fear, / a king is a man without desire” (388-9). Resisting the pull of one’s baser desires is straight out of stoicism’s playbook, and if there’s a tragic stoic hero in Thyestes, it’s the title character. The doomed and deposed king of Argos is told by one of his sons that he can be king, after all – he’s returned. Thyestes replies, “I can, since I can die” (443), emphasizing that he, Thyestes, like a stoic sage, has sovereignty over his emotions – indeed over his life and death.

In contrast, the more destructive figures in the play Thyestes avow their dedication to violence and unchecked desire. The fury that opens the play proclaims, “Let there be nothing out-of-bounds for anger. . .[L]et blood drench every land, and let Desire / conquer the mighty leaders of the people” (40,45-6). And as Atreus stalks up and down the stage, speechifying about his impending revenge, time and time again he emphasizes that there is nothing that he can do – nothing that he can even imagine, that will satiate his craving for grisly revenge. Atreus seems doubly damned, then, since he has been privy to the warnings of his attendant and the chorus alike, and still rushes ahead to seek his revenge. And Seneca’s Phaedra, as we heard in this episode, also hears warnings, and also ignores them.

In Phaedra, throughout Act 1, Phaedra’s nurse offers the counsel of the stoic in the face of Phaedra’s licentiousness. The nurse tells Phaedra that even if her desires are consummated, Phaedra will still have to live with the pangs of a guilty conscience (160-3). Cupid, says the nurse, is a myth – the truth is that people personify their sensualism in order to excuse it (195-7). Moreover, the nurse argues, again parroting ideas that pervade Senecan philosophy, covetousness and satiation, whether for sex or money, are a hollow and self-perpetuating cycle, and Phaedra should steer clear of this cycle (204-8). Before Phaedra’s nurse turns pander to her planned love affair, then, the nurse, like Atreus’ attendant in Thyestes, is at times a conduit for stoic ideas – ideas which are ignored to tragic and violent consequences.

These details might be a bit hard to absorb in podcast form, so let me zoom out and reiterate. As gruesome and dark as Senecan drama is, Seneca’s plays can be read as a whole as cautionary stories showing the consequences of unrestrained hunger. His tragic heroes do not live in vacuums – indeed they hear good advice, and they hear it delivered respectfully and diplomatically, and they deliberately override and ignore the counsel offered to them. Stoic principles sparkle around the dark vortexes of Senecan tragedy, offering glimpses of order and peace, and yet again and again they are ignored, at great cost to the figures in each play.

So while some generations theorized that Seneca the philosopher and Seneca the tragedian were different writers, the barest minimum of consideration can show us that Seneca’s tragedies are from time to time effective vehicles for him to advance his stoic ideas. But still, there is an obvious hiccup for Seneca’s tragedies as vehicles for stoic ideology. Plays in which stepmothers want to have sex with stepsons, and in which uncles slice nephews apart and feed them to brothers are unlikely vehicles for philosophical teachings that counsel self-restraint. Pervasively, in his plays Seneca is more interested in depicting sins and sinners in full, R-rated color than in actually laying out stoic doctrines or making his philosophy seem robust and appealing. We don’t remember the attendant in Thyestes – we remember the murdered children; comparably, we don’t remember Phaedra’s nurse’s brief flashes of lucidity, but instead the story of a lusty stepmother and the awful death of a falsely accused son. Put briefly, the faint mesh of moralizing that appears from time to time in Seneca’s tragedies is no match for the locomotives their bloody plots.

Jonathan Edwards, like so early American theologians, wrote imagistic sermons in which bombast and hyperbole are at work far more than syllogism and deduction. He shares with Seneca both a capacity to use fire and brimstone imagery for the sake of philosophical persuasion, and, perhaps, a tendency to sublimate repressed energy into wildly declamatory prose.

To Shakespeare and his contemporaries, rhetorical excess wasn’t a fault on Seneca’s part. It was exactly what they loved about him. Even early on, Seneca’s inflated oratorical qualities were among his most appealing to students who followed him in Roman literary history. The Roman rhetorician Quintilian wrote that during his own youth, “Seneca’s works were in the hands of every young man. . . But [Seneca] pleased them for his faults alone, and each individual sought to imitate such of those faults as lay within his capacity to reproduce.”12 These faults – namely an overwrought and amplified style – are his most distinct feature as a dramatist. The most gruesome crime in Greco-Roman literature – Atreus’ murder of his brother’s children, and his feeding Thyestes the flesh of Thyestes’ sons – this crime is not enough for the amplitude of Seneca’s imagination. Atreus exclaims, exulting over his brother’s unwitting cannibalism, “Even this is too little for me. / I should have poured hot blood into your mouth / direct from their wounds, to make you drink them alive. / My impatience cheated my rage” (1053-6). Seneca’s dramatic rhetoric is full of escalations like this one – in the play that we read today, Hippolytus feels so befouled by his stepmother’s lust that neither rivers, nor ocean have enough water to wash him clean; later, Theseus is so angry at Hippolytus that he wishes for a storm so great that it tears the stars from the sky; later still, Theseus is so compunctious that not only the darkness of the underworld is needed to cover his transgressions, but all of the rivers of Hades, too. Throughout his tragedies, Seneca reaches for hyperbole with insatiability, an insatiability that Shakespeare’s generation emulated with gusto.

Scholar Stephen Greenblatt, in the introduction to The Norton Shakespeare, calls the English playwright “The supreme product of a rhetorical culture, a culture steeped in the arts of persuasion and verbal expressiveness.”13 Sixteenth century English schoolchildren, whether they followed George Puttenham’s guidebook The Art of English Poesie or the Dutch humanist Erasmus’ rhetorical handbook On Copiousness, were systematically trained in linguistic embellishment, practicing drills on metaphor, metonymy, synecdoche, irony, anaphora, epistrophe, alliteration, dubitatio, apophasis, hyperbole, and more. Greenblatt writes of Shakespeare that, “What is most striking is not the abstruseness or novelty of Shakespeare’s language but its extraordinary vitality, a quality that the playwright seemed to pursue with a kind of passionate recklessness” (63). The same can be said of Seneca, both in his philosophical as well as his dramatic work.

Senecan tragedy appealed to renaissance dramatists, then, for the obvious reason that he was a Latin writer available from antiquity who had selected and retold eight of the Ancient Mediterranean’s bloodiest and most sensational tales. But more than this, the decadence of Silver Age Latin resonated with the increasingly ostentatious rhetoric of sixteenth- and seventeenth-century Europe. Seneca’s characters stalk the stage while growling horrid resolutions and voicing imprecations that stretch the bounds of linguistic imagination. Though they are trapped in their perverse pathologies, the Atreuses and Phaedras of Seneca’s plays possess a limitless capacity to paint pictures with words, to curse, to regret, to hate, to machinate, to use language to describe the outer reaches of human experience and beyond. Seneca’s style, then – his ravenous search for heightened hyperboles and more ornate figurative language, so out of step with his personal philosophy of moderatism – Seneca’s style exploded into early modern Europe, the dark horse Roman playwright unexpectedly becoming, for a couple of centuries at least, the main gateway into the extraordinary world of ancient tragedy. While he’ll always be remembered as as a philosophical mountebank – a man whose life never lined up with his philosophy – Seneca’s tragedies are nonetheless tremendous works, and early modern drama, and all literary history thereafter, might have taken a very different turn without them. [music]

Moving on to Petronius and the Satyricon

Well, I hope you enjoyed these four programs on Lucius Annaeus Seneca. I didn’t expect we’d have so much to say about him, but his life and works simultaneously offer us a tour of the Julio-Claudian dynasty, an introduction to the philosophical background of the New Testament, and some damned good plays that later proved pivotal to European drama. On the latter subject, let me recommend the Oxford Emily Wilson edition, which features Thyestes and Phaedra, as well as Seneca’s Oedipus, Medea, The Trojan Women and The Madness of Hercules. For all the flak Seneca has caught over the past two thousand years, in my opinion his plays are fun to read, and an often ignored missing link leading up to early modern drama.Well folks, we’ve been at this Roman literature thing for a while, now, and we have half a dozen shows to go before we switch it up a bit and cover the New Testament proper. As we move forward from Seneca, we begin to enter a century where biographical information and in some cases complete works are difficult to come by. Nonetheless, the ones that we have are as important and influential as almost anything we’ve covered in Literature and History, and the first of these is the Satyricon of a poet generally identified as Gaius Petronius, likely written during the late Julio-Claudian dynasty, or the 50s or 60s CE. The Satyricon is a contender for the earliest surviving novel in history, an alternatingly prose and verse narrative about the deeds and misdeeds of a burnt out gladiator called Encolpius as he treks around the porticoes and flophouses of Rome. It’s a funny, remarkable book. At times it seems like it could have come from the picaresque fiction of eighteenth-century England or the carefully polished first person narratives of fin-de-siècle France. And while the Satyricon is fragmented and often puzzling, it’s one of our most valuable cultural documents about what the masses of ancient Rome actually did with their time

After four shows on the gravely earnest Seneca, I think we’ll find Petronius a refreshing change of pace. Petronius died in the same purge that killed Seneca, but even in his death, according to Tacitus, at least (16.19), Petronius found very little around him that was to be taken seriously. So next time, in Episode 69: Rome’s Comic Novel, we’re going to laugh it up with one of history’s archetypical satirists, explore how Roman satire was changing during the early imperial period, and learn about the roots of prose fiction novels in the ancient world – roots which, during Petronius’ lifetime and just after, seemed to be appearing everywhere all at once. Thanks for listening to Literature and History. I have a quiz on this program if you want to see how much you remember about Senecan tragedy and the background of the Theseus myth cycle. For you Patreon supporters, I’ve recorded three poems by the seventeenth-century English poet Andrew Marvell – “The Mower’s Song,” one of his more conventional love pieces, “The Garden,” a far less conventional statement about love, and finally his “A Dialogue Between the Soul and the Body,” a stunning existentialist statement some 300 years ahead of its time. Marvell lived and wrote at a time when generations of English poets had absorbed the influence of works of classical Latin literature we’ve been reading lately – Ovid, Horace, Plautus, Virgil, and Seneca – and Marvell’s unique imaginative scope owes much to the alternate culture and morality he discovered when he read the writings of his ancient Roman forebears. For everybody, comedy song, coming up if you want to hear it. If not, thanks for being curious about Seneca – class dismissed.

Still listening? I got to – cogitating – about Hippolytus. Not just Hippolytus, really, but the general figure of the virginal, sylvan hunter slash huntress in Greco-Roman mythology. The devotees of Artemis – or in her Roman form, Diana, eschew all the comforts and norms of civilization for a chaste life of hunting wild animals and taking group baths in forest pools from time to time. Ovid’s Metamorphoses alone is full of these figures – the hunter Actaeon accidentally sees the goddess Diana bathing with her virgin squad, and makes him die an awful death. The virginal huntress Atalanta kicks ass in the Calydonian boar hunt, and later surrenders to the wiles of the persistent young swain Hippomenes. In the story we heard today, Hippolytus is a hunky nature boy who wants everyone to stay out of his business, but he’s also a really harsh, mean person in some ways, too. I got to thinking about all these woodsy virgins, dashing around in chastity belts and spearing boars and stags, and decided that I found it all to be pretty silly. And so I wrote the following song, which is called “Let’s Go to the Woods.” Hope it’s good, and Petronius and I will be bringing some more satire your way next time.

[“Let’s Go to the Woods” Song]

References

2.^ Wilson, Emily. The Greatest Empire: A Life of Seneca. Oxford University Press, 2014, p. 223.

3.^ The Palladis Tamia describes Plautus and Seneca as being the comedian and tragedian par excellence from the Latin world, and Shakespeare as both in contemporary England.

4.^ See de Luce, Judith. “Reading and re-reading the helpful princess.” In Hallet, Judith P. and Van Nortwick, Thomas, eds. Compromising Traditions: The Personal Voice in Classical Scholarship. London and New York: Routledge, 1997, pp. 25-6.

5.^ Seneca. Six Tragedies. Translated and with an Introduction by Emily Wilson. Oxford University Press, 2010, p. 4. Further references noted parenthetically with line numbers.

6.^ Seneca. Four Tragedies and Octavia. Translated by E.F. Watling. Penguin Books, 1966, p. 104.

7.^ Seneca. Delphi Complete Works of Seneca the Younger. Delphi Classics, 2014. Kindle Edition, Location 1617.

9.^ Seneca. The Tragedies of Seneca. Translated by Ella Isabel Harris. Oxford University Press, 1904, pp. 205-6.

10.^ Trinacty, Christopher. “Senecan Tragedy.” Quoted in The Cambridge Companion to Seneca. Cambridge University Press, 2015, p. 43.

11.^ Wilson, Emily. “Introduction.” In Seneca. Six Tragedies. Oxford World’s Classics, 2010, p. xx.

12.^ Quintilian. Institutes (126,7). Printed in The Complete Works of Quintilian. Delphi Classics, 2015. Kindle Edition, Location 11221.

13.^ Greenblatt, Stephen. “General Introduction.” In The Norton Shakespeare, ed. Stephen Greenblatt. et. al. W.W. Norton and Company, 1997, p. 61. Further references noted parenthetically.