Episode 69: Rome’s Comic Novel

Petronius’ Satyricon is a contender for history’s first novel, a picaresque filled with sex, misadventures, and details about daily life.

| Read Transcription | References and Notes |

| Episode Quiz | |

| Episode on Spotify | Episode on Apple Podcasts |

| Previous Show | Next Show |

Petronius’ Satyricon

Hello, and welcome to Literature and History. Episode 69: Rome’s Comic Novel. This program is about the Satyricon, a comedic work of mixed prose and poetry, produced by the Roman poet Petronius in the early 60s CE. The Satyricon is an episodic narrative about the misadventures of a former gladiator as this gladiator treks through mansions and brothels in the resort country southeast of Rome. The Satyricon, as it survives today, was once part of a much longer work – a vast first person narrative that traced its protagonist’s excursions throughout the late Julio-Claudian world. Believed to have been produced sometime around 63-65 CE, the Satyricon is filled with gaps and puzzles, and its author is just as mysterious as the text he left behind.1 The Satyricon’s author, Gaius Petronius, often called Petronius Arbiter, was a noble of some distinction who served in Nero’s court, but who perished in the same purge that killed Seneca. His title, arbiter elegantiae, or “style expert,” suggests that he was consulted on matters of taste. But the contents of the Satyricon suggest a writer who understood far more than court finery. A broad array of characters and idioms populate Petronius’ book – rich tycoons and common prostitutes, professors and priestesses, and slaves and pimps and performers of all stamps. What makes the Satyricon an entrancing read, century after century, is that unlike nearly the entire prehistory of literature that predated it, Petronius’ book is not about gods, or heroes, or even aristocrats, but instead, a colorful cross section of delinquents, hustlers and buffoons straight out of the streets and back alleys of first century Rome.

Rome’s decadence, such as we see in Petronius’ Satyricon, had fascinated Romans themselves since at least the time of Cato the Elder in the mid 100s BCE. By the period of the late Julio-Claudians and afterward, authors like Petronius, Tacitus, and Juvenal catalogued the excesses of wealthy Romans with a mixture of bemusement, scorn, and incredulity.

There are elements of the Satyricon that we can’t get in translation. Petronius had an ear for poetic diction and colloquial speech alike, and the novel shines with Latin puns and clever poetic adaptations that don’t come across easily in English. The nature of some of Petronius’ jokes is enigmatic – we often wonder if the writer is referencing some lost element of Julio-Claudian culture, or more simply one of the fragments of the Satyricon that we no longer possess. Nonetheless, regardless of what we miss when we read the Satyricon in English, I think that even in translation, and even in podcast form, this book is required reading within Rome’s literature. With is expansive cast, its picaresque adventures, its deft mixture of prose and poetry, and its decadent and surrealistic scenarios, the novel is simply unforgettable, and I think we should begin our journey into the Satyricon by discussing the basics – its structure, its characters, and its plot. [music]

Petronius’ Satyricon‘s Structure and Characters

At a little under 100,000 words, the Satyricon is about the length of a modern novel – a work of 200 to 300 pages if printed according to the conventions of contemporary fiction publishing. The length, according to scholar Helen Morales, is about a tenth of the work’s original size, which would have put it on par with the Old Testament, New Testament, and Apocrypha all together in one volume.2 The ancient world certainly prized prolific output – Petronius’ contemporary Seneca was fortunate enough to have the majority of his works survive, but nonetheless the fact that Petronius wrote a single comic novel that was the length of the entire canon of Christian scripture is astonishing. Petronius’ sexually dysfunctional protagonist once traipsed through an epic longer than the Iliad, Odyssey, Argonautica, and Aeneid combined, and if what survives of the Satyricon is any indication, Encolpius’ travels might have spanned much of the Roman world.What we have today, however, is a small portion of the book – a swiss cheese of tasty prose and poetry pocked with missing information. The surviving Satyricon takes place in Campania and the Bay of Naples, and then later on the southern coast of Italy, in a warren of flophouses and baths and banqueting halls that allow Petronius to introduce a surprisingly broad array of stock characters from Neronian Rome – the nouveau-riche buffoon, the stuffy rhetorician, the predatory madame, the randy old tutor, and in the Satyricon’s protagonists, at least, a trio of buccaneering ne’er-do-wells as likely to betray one another as they are to somehow slide from adventure to perilous adventure, generally unscathed. In talking about the Satyricon’s structure then, the first thing one needs to know upfront is that the book that survives today was once part of a substantially longer story. The second thing that one learns in any introduction to the Satyricon’s structure is that the book is a mixture of prose and verse. There is a name for this sort of comic style in classics, and that is Menippean satire, named after the third century BCE writer Menippus of Gadara, who frequently used his works to make fun of Epicureans and stoics. Menippean satire, or more generally prosimetric writing – writing that mixes prose and verse – are useful terms for preparing to read Petronius’ Satyricon. What we have today in Petronius’ novel is predominately prose – Petronius’ first person speaker Encolpius generally tells his story without meter. But from time to time, most often, another character will ascend into flights of verse, allowing Petronius to alternately make fun of certain verse styles, or ritual occasions in which poetry is traditionally used.

So far, then, we’ve established that Petronius’ Satyricon is a fragmentary novel made up alternately of prose and verse. As you can imagine, the novel’s structure occasionally makes it a challenging read – from the very beginning we’re thrown into the Satyricon right in the middle of an unfolding episode, and the book breaks off nearly in midsentence, having taken us in the meantime through all sorts of combinations of prose and verse. For that reason, I think we should introduce some of the book’s main characters before the story begins.

The Satyricon’s narrator and protagonist, again, is called Encolpius. His name means “In-crotch,” or perhaps just “crotch,” and a great deal of the novel concerns the deeds and aspirations of Encolpius’ private parts.3 While we learn at one point that Encolpius is an ex-gladiator, he’s hardly a brawny and commanding figure, striding unafraid through the palaces and dregs of provincial Rome. Instead, Encolpius is a sort of comic layabout, picking up free food and sex where and when he can, committing crimes when he needs to, and running for his life when the occasion demands. To a modern reader, Encolpius’ perspective is part of what makes the Satyricon so surreal. We tend to pause at passages involving sex with teenagers, or shockingly decadent wealth, or abrupt orgies, but Encolpius takes almost all of it in stride. While the figures and places Encolpius encounters appear with a sort of dreamlike strangeness to the modern reader, the intrinsic nature of his relationship with the book’s other two main characters is also something that should be explained upfront.

One of Encolpius’ traveling companions is another man perhaps his same age. This man is called “Ascyltus,” whose name can be translated as “undisturbed,” or “unharassed.”4 Ascyltus joins Encolpius in the protagonist’s thieveries, freeloadings, and sexual expeditions, but seems to fade off camera from time to time when Encolpius gets in trouble. Further, Ascyltus’ name, “undisturbed,” is likely also a reference to his fully functional anatomy – Encolpius may be unable to achieve an erection, but Ascyltus is not disturbed by this problem. And there is a source of friction between the two men – a source of friction that has to do with their other traveling companion.

Encolpius and Ascyltus, throughout the Satyricon, are roving through Campanian streets and gutters in the company of a third companion. Attractive, youthful, and willing, Giton, whose name means “mate,” is a source of constant tension between Encolpius and Ascyltus. A teenage boy, Giton is with Encolpius one moment, and the next with Ascyltus, and while Encolpius enjoys an array of hookups and attempted hookups with a variety of lovers in the Satyricon, his primary affections are for his traveling companion Giton. So, it’s good to know those three characters upfront – the flaccid protagonist Encolpius, his adult friend Ascyltus, and the object of their rivalry, the handsome teenager Giton.

The Satyricon begins with these three going on a short series of adventures that culminate in an erotic evening at a brothel. Instead of jumping right into the first episode of the Satyricon, though, I want to tell you a bit about the book’s overall plot. A relatively brief series of opening misadventures lead to the book’s longest scene. This scene is a feast. It’s a feast at the home of a very distinct character – a nouveau-riche freedman named Trimalchio. Trimalchio, a former slave, has become ridiculously rich in the years since he’s been freed. Trimalchio possesses all of the wealth of the uppermost aristocracy, but has neither their education nor pedigree, and so his household is a surreal combination of staggering opulence and utter buffoonery – Trimalchio is, essentially, a boor with limitless money. Trimalchio is a character that most readers recall from the Satyricon. F. Scott Fitzgerald planned his own nouveau-riche tycoon, Jay Gatsby to be a similar character – a man of vast wealth and a mansion at West Egg who nonetheless just didn’t have the pedigree of neighboring aristocrats, and Fitzgerald’s original title for The Great Gatsby was Trimalchio at West Egg. While Encolpius, Ascyltus, and Giton are our main tour guides in the Satyricon, then, their most famous stop is at the mansion of Trimalchio, a man with laughable pretensions of education and class whose decadent displays of wealth can’t quite compensate for his lowbred background and oafish personality.

While the feast at Trimalchio’s is the Satyricon’s centerpiece, in its aftermath, Encolpius ends up continuing his journey further – on down the Italian coast and to an aging former Magna Graecian colony populated with roughs, swindlers, and horny women. As incomplete as it now stands, the Satyricon is nonetheless a boisterous romp of a book, and a tour through first century Rome far different than anything available in the historical archive. At the end of this program, I’ll tell you a bit about Petronius himself, and the historical reception of the Satyricon. For now, though, let’s jump right into the story. Unless otherwise noted, I’m quoting from the popular J.P. Sullivan translation, published by Penguin books in 2011 in an excellent edition that includes an introduction and notes by scholar Helen Morales. And one final warning – we’re heading into the secret honeycombs of Rome’s brothels here – every conceivable kind of sex and nudity in the world is going to be on display, along with a fair amount of pedophilia, incest, scatological humor, and that kind of thing. I don’t feel the need to use much profanity myself in this show, but when authors do, I don’t censor it, so, with respect for your tastes and preferences, be forewarned.

Petronius’ Satyricon‘s Opening: Encolpius and the Orator Agamemnon Discuss Oratory

Encolpius in a street scene, from illustrator Norman Lindsay’s 1910 illustrations to Petronius’ Satyricon.

Great oratory, Encolpius argued, wasn’t pedantic or baroque. It was intrinsically beautiful. Rome was being infested with the prolix styles of the east, and the styles of Asia Minor had lost the virility of Sophocles and Pindar. The man with whom Encolpius was talking, after listening carefully, offered his perspective. This man, again, was a teacher of rhetoric named Agamemnon.

Certainly, said Agamemnon, teachers of rhetoric pandered to their students. Their students wanted showiness, and complexity – but even more than the students, the parents of students wanted this. Parents were too ambitious for their children, said the professor Agamemnon. Parents threw their children into the study of oratory at a ridiculously young age – before their children had ever even read anything! Subsequently, adolescent boys pranced around with the affectations of great orators but didn’t really know anything of substance. Yet (changing the tenor of the conversation suddenly) Agamemnon said he wasn’t at all above a bit of flashy poetic improvisation – indeed, said Agamemnon, he’d follow his predecessor, the Roman satirist Lucilius, and riff some verses.

The verses in question were, essentially, a call for a return to a purer and more genuine poetic tradition – one divorced from aristocratic splendor and the decadence of Neronian public performance culture. Contemporary theater and oratory, said Agamemnon, were things young writers ought to stay away from – instead they should read the ancients and write with the same fiber and sincerity as they did.

And it should be noted that this whole opening scene is satirical – Encolpius and Agamemnon both throw themselves into the florid excesses of Silver Age Latin rhetoric while simultaneously attesting to its inferiority to a lost past, thus undermining their entire diatribe. The satire of the Satyricon, then, from its very beginning, is self conscious and reflexive. One of the more prominent early scholars on Silver Age Latin, Wilhelm Siegmund Teuffel, wrote that the Latin of Petronius’ generation “was dressed up with much tinsel of sentences, rhetorical figures, and poetical expressions. . .Manner supplanted style, and bombastic pathos succeeded to the place of quiet power.”5 And Petronius, well aware of his own generation’s rhetorical excesses, uses his generation’s rhetorical excesses in order to satirize them. [music]

Encolpius Looks for Ascyltus and Finds him in a Bordello

To continue the story of the Satyricon, Encolpius didn’t listen to the rhetorician Agamemnon’s entire speech. Encolpius noticed that his friend Ascyltus had gone off somewhere, and fretted, because he didn’t know where they were staying during their visit to Naples. Encolpius wandered away from the colonnades of the rhetorical school and, at a loss for what to do, simply asked an old woman where his friend Ascyltus was staying. It was an odd question, but she didn’t seem to think so. The old woman brought him to a removed place and drew back a curtain to reveal some aged prostitutes. Encolpius, not wanting to be at a brothel just then, went straight through. As he wandered through, he was surprised to see that his friend Ascyltus was there, after all. Encolpius asked Ascyltus what the other man was doing in a low class bordello – Ascyltus said he’d been led there by another man who had clearly been planning on having sex with him – only superior physical strength had saved him from sexual assault.Later, however, Encolpius heard a different story. A teenage boy was traveling with Encolpius and Ascyltus – a boy that each man desired sexually, and his name was Giton. And Giton told Encolpius that Ascyltus’ story about the brothel had been false. Ascyltus, in fact, had attempted to rape Giton. Encolpius was furious, and the two men, although they tried to laugh off the incident, decided that they would part company after going to a dinner they’d planned for the next day.

Thereafter Encolpius enjoyed a tryst with his teenage lover Giton in their room. And Ascyltus, jealous, barged in on them and correctly accused Encolpius of jealousy, and of hogging the handsome young man all to himself.

Later that day, when dusk was falling, the three men had stolen a cloak from somewhere. The cloak, however, had been misplaced, along with some money they’d left in it. The men were trying to get it back, and in the process got into a dispute about the cloak, nearly incurring the attention of law enforcement. In the end, they got their garment and money back and hurried back to the room they’d rented, locking the doors. [music]

The Party and Orgy with Quartilla

The next part of the story is fascinating but just a bit confusing, so let me offer you some background. Evidently, at some point in the past, Encolpius and his companions had stumbled into a ritual led by a woman named Quartilla – a ritual surrounding the erotic rites of the god Priapus. It was a secret ritual, and after witnessing it, Encolpius and company had left the scene. Quartilla, a sort of erotic madame-slash-priestess figure, was not happy about this, worrying that Encolpius would report witnessing the scandalous rites – perhaps some sort of orgy – to the authorities. And so Quartilla tracked the three men down.That night, after the cloak incident and after dinner, the three travelers heard an insistent knock at their room’s door. They opened the door to discover a maid – the maid of the erotic priestess Quartilla. The maid burst into speech, saying they couldn’t possibly expect to witness the illicit rites of Priapus and walk away from it. And just then Quartilla herself appeared. They had committed a dreadful sin, the erotic priestess exclaimed, and she feared that the travelers would make public what they’d seen. She cried on Encolpius’ bed, and he comforted her and said her secrets were safe.

A none-too-modest illustration of Quartilla, from illustrator Norman Lindsay’s 1910 illustrations of Petronius’ Satyricon.

Young Giton began fooling around with Quartilla’s attendant. Encolpius and Ascyltus were tied up and smeared with aphordisiacs. A male prostitute arrived and had sex with both Encolpius and Ascyltus. Not to linger on the pornographic details, but just so you know how explicit Petronius gets, the description of this male-on-male sexual encounter is as follows: “He pulled the cheeks of our bottoms apart and banged us, then he slobbered vile, greasy kisses on us” (16). Not a lot of ambiguity there. Following the encounter with the male prostitute, both Encolpius and Ascyltus vowed to one another that they’d never speak of it again.

More of Quartilla’s attendants arrived. They untied Encolpius and Ascyltus and rubbed them with oil. The travelers enjoyed some appetizers and a great deal of wine. The inn was still locked, the hour was growing late, and the oil of the lamps was running out – everyone seemed to be drowsing with intoxication. At one point, some Syrian thieves arrived and prepared to steal some valuables, but ended up falling asleep, too. However, later still, the lamps were refilled, and people started drinking and carousing again. A male prostitute, powdered and perfumed, came in and sang a song and then attempted to arouse Encolpius by groping at the other man’s crotch. Encolpius begged to be left alone, and so the male prostitute turned his attentions to Ascyltus with more success.

What happens next is foul even by the debased notions of Neronian Rome. Quartilla decided that her young attendant should lose her virginity to Encolpius’ teenage companion, Giton. The thing is, this attendant, as Encolpius describes her, was “quite a pretty thing who appeared no more than seven years old” (18). This, to Encolpius, was far too young for such things. Quartilla, however, encouraged Encolpius by saying that that had been about her age when she’d lost her virginity, and so with some fanfare, and admittedly no opposition from the young couple, Giton and the little girl were ushered into a private chamber, where the audience is led to assume they had sex. The evening thereafter degenerated into a general orgy.

The next day, conscious of the extent of their dissipations there at the inn, the travellers had every intention of vacating the premises. However, a slave came by and reminded them of something. They were to have dinner at the home of an astonishingly rich man – one of the main characters of Petronius’ Satyricon – a man named Trimalchio. The travellers went to some local baths, and soon enough, they had their first glimpse of this Trimalchio. A bald, elderly man, Trimalchio was tossing a ball with some good looking boys. A pair of eunuch attendants stood by, and when Trimalchio snapped his fingers, one of the eunuchs rushed forward with a bottle so that Trimalchio could urinate into it without interrupting his game. Thereafter, Trimalchio wiped his fingers into the hair of one of his young slaves. Dinner, it seemed, had begun. [music]

The Feast at Trimalchio’s: The Early Part of the Evening

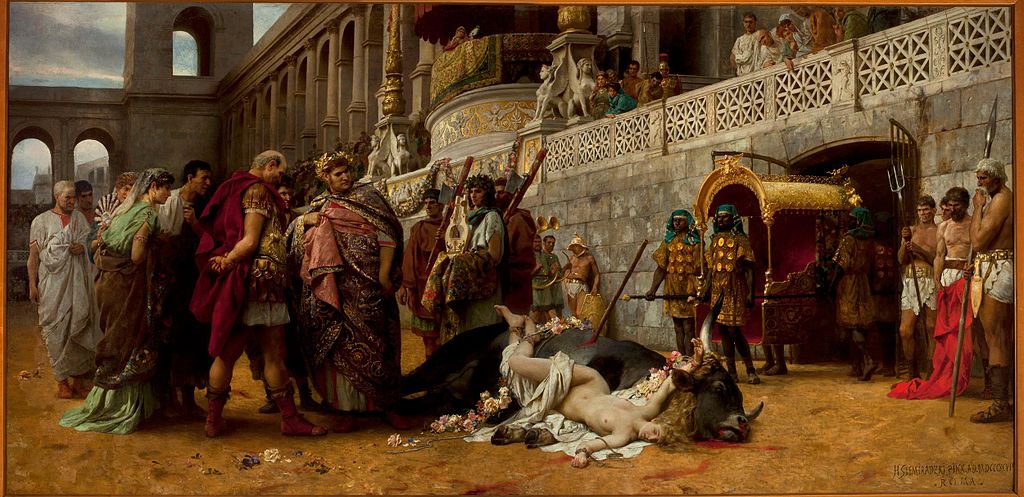

A nineteenth century French frontispiece showing the decadent feast at Trimalchio’s, which makes up the longest episode in the surviving parts of Petronius’ Satyricon.

As they followed Trimalchio and his litter-bearers into his house, they passed a sign which read, “ANY SLAVE LEAVING THE HOUSE WITHOUT HIS MASTER’S PERMISSION WILL RECEIVE ONE HUNDRED LASHES” (21). Trimalchio, a former slave, clearly had little sympathy for others in the circumstances which had once been his. Encolpius, following Trimalchio, was startled by a trompe l’oeil painting of a large dog and then gaped at a mural of a slave market. The travellers passed a procession of spectacles – runners, silver statues, and a marble sculpture of Venus with a golden casket which, Encolpius was told, held the shavings of Trimalchio’s first beard.

Everything the travelers saw attested to Trimalchio’s vast ego – his extreme decadence and self aggrandizement. Trimalchio was picky on deportment – the travelers were compelled by slaves to step into the dining hall with their right feet first. They took seats on lavish couches around the dining table – Trimalchio himself had not yet arrived. The guests had ice water poured on their hands – their feet were washed and their toenails trimmed while Alexandrian boys sung songs – as Encolpius reflected, “It was more like a musical comedy than a respectable dinner party” (23). Then, the appetizers were served.

The feast scene in Petronius’ Satyricon – the central part of the story that survives today, is replete with incredible detail – Encolpius’ initial description of the dishes on which the appetizers were served is a good example of the decadent minutiae of the rich freedman’s dinner. Here’s a short piece of the J.P. Sullivan translation describing the appetizers served.

The dishes for the first course included an ass of Corinthian bronze with two panniers, white olives on one side and black on the other. Over the ass were two pieces of plate, with Trimalchio’s name and the weight of the silver inscribed on the rims. There were some small iron frames shaped like bridges supporting dormice sprinkled with honey and poppy seed. There were steaming hot sausages too, on a silver gridiron with damsons and pomegranate seeds underneath. (24)

As the guests began enjoying the first course of dinner, Trimalchio himself appeared. His appearance caused the guests to laugh – his head was shaved like that of a freedman, his purple striped napkin was a self-conscious imitation of the senatorial class, and his gold rings looked like ones the equestrians wore – clearly, he had more money than style, and it was evident to everyone present. Trimalchio brought tiny, exquisitely prepared hens’ eggs out of body of a wooden hen carried by an opulently dressed slave boy and distributed them to his guests.

After the appetizer, dishes were picked up with commotion and orchestral accompaniment, Trimalchio congratulated his guests on the fact that he was now serving them 100 year old wine, although, editor Helen Morales tells us in a footnote, since wine was not kept in glass bottles during this period, this would have been impossible. So Trimalchio proudly and ignorantly announced the vintage of his wine, to the amusement of his wiser guests. A fake silver skeleton was brought in just after the opening of the wine, and Trimalchio took the opportunity to offer his guests a bit of meditative doggerel – in the William Arrowsmith translation,

Nothing but bones, that’s what we are.

Death hustles us humans away.

Today we’re here and tomorrow we’re not,

So live and drink while you may!7

Trimalchio’s slaves then carried in a curious dish – a circular platter printed with the twelve signs of the zodiac, with a dish for each sign – a lobster for Capricorn, a steak for Taurus, and so on. A slave sung a tawdry song, and then the extravagant absurdity intensified – dancing waiters removed a covering from a dish to reveal plump game birds, the udders of pigs, and – most ridiculously – a rabbit with meat wings attached in an attempt to make it look like the Pegasus. Delighted at the spectacle he had bankrolled, Trimalchio told one of his slaves to carve up the dishes and distribute them. And Encolpius, already stuffed with food and astonished at the events of the evening thus far, turned to the man next to him and asked what in the holy hell was going on. [music]

The Feast at Trimalchio’s: Conversations with Other Guests, the Evening Lengthens

Considering Petronius’ official post of the arbiter elegantiae for the Emperor Nero, the infamous last of the Julio-Claudians lurks behind the most excessive moments of Petronius’ Satyricon, even though he makes no appearance in what survives of the story.

Trimalchio interrupted the general conversation to make a speech in which he attempted to showcase his erudition. He had a little bit to say about each of the twelve astrological signs on the dinner dish, telling his guests about the nature of each one, and his guests applauded politely at their boorish host’s basic knowledge of astrological symbolism. And then suddenly, it was time for next part of the celebration.

Abruptly, the guests were draped with blankets embroidered with hunting scenes. Just as suddenly, hunting dogs were released into the room. And a spectacle unfolded that is as surrealistically bizarre as anything else in Petronius’ Satyricon. A roasted giant boar was brought in wearing a freedman’s cap. Around its nipples were tiny piglets made out of cake, intended as party favors. A slave sliced open the boar, and thrushes flew out of the wound – but the little birds were seized, killed, and given to the guests.

Encolpius asked his chatty neighbor why the boar was wearing a freedman’s cap. What a silly question, the guest said. The boar had been enslaved, but now, killed for supper, it was freed! Encolpius wondered why the explanation hadn’t occurred to him.

The weirdness continued to escalate. A good looking young man dressed as Dionysus entered and began singing – Trimalchio told him to behave as a freedman, and the youth plucked the freedman’s cap off of the dead boar and put it on. Satisfied, for a moment at least, Trimalchio arose and went to the bathroom, leaving his guests to converse amongst themselves. [music]

The Feast at Trimalchio’s: The Host Displays Increasing Boorishness

When we read Plato’s Symposium, the most famous story about a drinking party from the ancient world, the story requires no small suspension of disbelief. There’s no way, we think, that partygoers get together and swig wine and discuss philosophical ideas with such mellifluous profundity. Surely, even the most elegant dinner parties involve some slurs and malapropisms once the booze gets flowing. Well, unsurprisingly, Petronius’ dinner guests in the Satyricon are hardly as eloquent or erudite as Plato’s in the Symposium. In the Satyricon, the guests that Encolpius hears talking are earthy, uncouth, and inarticulate, giving us fascinating sound bytes from the Julio-Claudian middle and lower classes – their gossip, their folkways, their figures of speech, and their transparent pretences.It had been cold recently, we gather, and Trimalchio’s guests talked about drinking warm beverages, about how often they bathed. They gossiped about a wine merchant who’d recently passed away – how much wealth he’d left behind, how he’d carried his age well, how he liked to have sex with little boys. Another man complained a drought and the dearth of corn, then of how everyone was impious in contemporary society and had given up praying and feasting. Another man discussed wealthy politicians who put on gladiatorial games, and the games themselves. Now, Agamemnon, the rhetorical tutor with whom Encolpius was talking at the opening of the Satyricon, was also there in attendance, but Agamemnon remained silent as the more churlish attendants of Trimalchio’s party shot the breeze, and one of the attendants said his son, Agamemon’s pupil, was a bright young man excelling in his Latin and Greek, and if the young man could put aside his silly interest in poetry and birds, he’d make a fine lawyer.

Trimalchio, just then, reentered from his bathroom break. He admitted that he’d been suffering from constipation, and said that if any of the other guests needed to use the toilet over dinner, they should think nothing of it. Then, the orchestra struck up a tune, three live white pigs were brought in, decorated with bells, Trimalchio asked his guests which one they would like to eat, and then without waiting for a response, he said they’d eat the older one.

As this next course was prepared, Trimalchio struck up a conversation with the orator Agamemnon – that same rhetorician Encolpius had been chatting with in the Satyricon’s opening scene. Trimalchio pretended great knowledge of mythology, recalling reading about Hercules’ twelve labors in Homer, and how the Cyclops tore out Odysseus’ eye. Which are certainly interesting statements, since Homer does not write of Hercules, and the Cyclops does not harm Odysseus’ eyes in the Odyssey. Trimalchio went on and on with his pretensions of literary knowledge and then the next course was brought in. After a brief farce in which a slave pretended to have forgotten to gut the large pig Trimalchio had selected earlier, the pig’s belly was slit open to reveal cooked sausages.

Trimalchio then took it upon himself to tell Encolpius of how Corinthian metalwork began – in other words, where metal housewares from Corinth came from. What had happened, Trimalchio attested, was that when Hannibal captured Troy, all the metal odds and ends were removed from the city and melted down. Only, of course Hannibal was at work a thousand years after the events at Troy, and so the story only further showcases Trimalchio’s buffonery. As Trimalchio gabbed on and on about his silver and gold finery, he told garbled stories about the Trojan princess Cassandra, confusing her with Medea. He got his facts wrong telling the story of Queen Pasiphaë and the minotaur.

Trimalchio’s mealtime entertainments, as Nero’s are said to have, involved dangerous acrobatic performances. From Norman Lindsay’s 1910 illustrations of Petronius’ Satyricon.

Next in the evening’s entertainments were acrobatic performances, an entertainment simple and spectacular enough for even Trimalchio to understand. A young male acrobat, unfortunately, fell onto Trimalchio’s couch, but rather than punishing the young athlete, Trimalchio decided to free him, much to everyone’s approval. Thereafter, Trimalchio hosted a predictably dilettantish conversation about literature, comparing Cicero to a contemporary lowbrow poet and thereafter attesting that literature really was the most challenging of professions. Trimalchio then philosophized about which animals were the most important, and in the midst of his monologue, presents were brought out for the guests.

Encolpius’ companion Ascyltus laughed so hard at the amusing gifts that one of Trimalchio’s freedman friends took offense, and accused Ascyltus of mocking freedmen in general. The teenager Giton, then, also broke into laughter, earning the scorn and anger of Trimalchio’s freedman acquaintance. The angry freedman got so worked up that Trimalchio had to tell him to simmer down, and, with his acquaintance placated, Trimalchio announced, it was time for the evening’s next entertainment – recitations from Homer. [music]

The Feast at Trimalchio’s: Artistic Pretensions and Hedonism End the Evening

Some actors came into the room and recited some scenes from Homer in Greek. Trimalchio, being the host, took it upon himself to explain the scenes, getting well known elements of the Homeric epics laughably wrong. He confused Iphigenia with Helen, and didn’t even understand the most basic facts of the Iliad. In the middle of the performance a boiled calf was brought in and sliced apart by a mummer dressed as the Greek hero Ajax.Thereafter, prompted by his host, one of Trimalchio’s freedman guests told a bizarre story about how he’d been out with an acquaintance. The acquaintances had urinated in a circle around himself and then transformed into a wolf. While ravaging some local livestock, the werewolf had taken a spear through the neck and – Trimalchio’s friend concluded – he’d seen his werewolf friend back in human form later, getting his neck wound attended to. Then Trimalchio himself added his own story.

Once, Trimalchio said, his former master had a handsome young slave – and this slave died. When he died, some witches appeared and began screaming. A burly slave stabbed one of the witches, but later, he went insane and died. As for the handsome young male slave that Trimalchio was talking about, his body was transformed into straw. This, said Trimalchio, really had happened. After trying to elicit more stories from his guests, Trimalchio looked for his own pet slave boy. And in one of the strangest back corners of the Satyricon, Petronius writes,

Trimalchio. . .looked round for his little pet, whom he called Croesus. The boy, however, a bleary-eyed creature with absolutely filthy teeth, was busy wrapping a green cloth round a disgustingly fat black puppy. He put half a loaf on the couch and was cramming it down the animal’s throat while it kept vomiting it back. (51)

Again in sheer strangeness of imagery, this ranks pretty high. So this overstuffed puppy ended up getting into a barking match with a much larger dog, but nothing came of it, and Trimalchio was soon serving a vast course of wine to the guests, who were already inebriated.

A man named Habinnas arrived late to the party – a noted stone mason. Being prompted by Trimalchio, Habinnas described a fulsome recent meal he’d consumed. Thereafter one of Habinnas’ slaves put on a farcical and dreadful little performance, much to the satisfaction of his master.

The lowbrow entertainments and intense gluttony continued thereafter. A pair of slaves pretended to fight, but when they broke each other’s jugs, oysters and scallops poured out and were served to the guests. The guests’ feet were slathered with sweet cream by slave boys. Trimalchio, growing maudlin, told the assembled company that he would free all of his slaves when he died – indeed the plan was already in his will, which he had read to the guests. Then he read his epitaph, bursting into tears at the end, and causing his guests to do the same. Trimalchio proposed that all the guests head to the bath house. Encolpius and his two companions briefly tried to make a break for it, but after being lost and redirected they ended up joining Trimlachio in the bath house anyway.

When the bath wound up, it was dawn, and Trimalchio undertook superstitious rituals at the sound of the crowing cock. As dawn broke, the party soured somewhat. A handsome slave boy came in and Trimalchio grabbed him and began kissing him. Trimalchio’s wife objected, but he sloshed his glass in her face. He said he’d freed his wife – he could do whatever he wanted. The declaration prompted a longer story about Trimalchio’s rise in fortunes. Trimalchio had been promoted only after his master died – his master had left him with half of his master’s fortune. Immediately financially successful, Trimalchio thereafter got into the shipping trade. He waxed on about his eventual financial goals and then, as before, began to drunkenly ramble about his own death, having some horn players come in and asking them to play him the sort of thing they would play for his eulogy. The horn players were so loud that a local firefighting team mistakenly thought Trimalchio’s home was ablaze, and as firemen crashed into the house, Encolpius and his companions, though drunk and disoriented, managed to skulk out of the house and get back to their inn. The travelers settled into their beds, and Encolpius awoke distressed to discover that Ascyltus had taken advantage of Encolpius’ inebriation to take young Giton to his bed for the night.

A Scuffle for Giton, An Afternoon at the Museum

The feud over handsome young Giton, which has been in the background of the Satyricon for the previous few chapters, suddenly became pressing. Encolpius and Ascyltus were at one another’s throats. Swords were drawn. Giton begged them to stop, and Ascyltus proposed a solution. Giton himself would choose which man would be his lover. Encolpius said this was fair. He had no doubt as to whom the young man would select. And sure enough, once the decision was made to let Giton decide, Giton rose and went immediately to. . .Ascyltus.Encolpius was heartbroken. He went to an inn and wallowed in sorrow for several days. He’d been a gladiator, he said – he’d taken great risks and led a difficult life, and now, after everything, he was going to just give his lover up to a rival? Encolpius went out with sword in hand and vengeance in mind, but soon enough a soldier saw him and told him to go home. And in the end, Encolpius was glad no one had been hurt.

Art and artistic production are common themes throughout Petronius’ Satyricon, even when pretenders to artistic expertise are revealed as imbecilic. The painting is Kristian Zahrtmann’s A Roman Plasterer (1886).

The tutor’s x-rated seduction story heartened the morose Encolpius, and the two men turned to more academic subjects. The old tutor, looking at a painting of Troy’s fall, recited a poem about it – a poem that recounted the second book of Virgil’s Aeneid about the traitor Sinon convincing the Trojans to open their walls to the fateful Trojan Horse. The tutor, however, was chased out of the museum for reciting too much poetry, and later Encolpius agreed that the old pedant had really overdone it.

When Encolpius returned to his hotel, he saw Giton there. The youth looked sad and crestfallen, and he told Encolpius that he regretted his decision to choose Ascyltus. Later, Encolpius and Giton had a teary reunion. The old tutor from the museum, joining them for dinner, told them of how he’d been assaulted in the bathhouse for reciting poetry, and how also in the bathhouse, he’d seen Ascyltus. Ascyltus, himself now brokenhearted over the loss of the mercurial Giton, was wailing about his missing lover. Fortunately for Ascyltus, he had such an enormous penis that it wasn’t long before he found some other people interested in taking him home for the night, and so he had at least a decent night, after all.

Having finished his story about Ascyltus and his serendipitiously large penis, the old tutor began reciting poetry. Encolpius furiously told the tutor to cool it with the verse recitations, already. And the old tutor, shortly thereafter, locked Encolpius in his room and hurried off to find handsome young Giton. At a loss for anything else to do, Encolpius prepared to hang himself, but Giton returned just in time and prevented Encolpius’ suicide. Chaos broke out. Giton pretended to kill himself with a blunted razor. The property manager appeared and got into a fight with the old tutor from the museum. Encolpius and Giton hid in the room while the old tutor was beaten and kicked around. Young Giton asked Encolpius to help the old tutor, and Encolpius, jealous of the old tutor as a rival, instead punched Giton in the head to silence him.

The old tutor’s fortunes suddenly changed for the better – one of the men at the hotel said the old man might write satirical verses about his wife. And simultaneously, Encolpius and Giton’s fortunes suddenly changed for the worse. Ascyltus had returned to the inn with some police men, and he was offering a reward of a thousand sesterces for information on the whereabouts of young Giton. Encolpius’ room was searched, and Giton was discovered there. After some commotion unfolded, Encolpius, the old tutor, and Giton found themselves aboard a very perilous ship – a ship bound for far away. [music]

The Voyage to Croton

Now, some context is necessary, some context about the ship on which Encolpius and Giton have just ended up. There seems to have been an episode in the Satyricon in which Encolpius really, really did wrong to a man named Lichas. Encolpius seduced Lichas’ wife. He had sex with Lichas’ prostitute. And Giton, Encolpius’ current male lover, had formerly been Lichas’ prostitute’s slave. For many reasons then, when Encolpius and young Giton and the old tutor found themselves aboard Lichas’ ship, Encolpius was aware that he had made a big mistake.Encolpius and the old tutor discussed how they might sneak off of the ship. The old tutor said he’d shave the hair and eyebrows off of Encolpius and Giton and emblazon their faces with the marks of criminals. And soon enough, it was done. When the ship’s owner Lichas saw the two ostensible slaves, the old tutor had them whipped to add to the false story that the disguised Encolpius and Giton were criminals. Yet Lichas and his prostitute, as Encolpius and Giton were whipped, recognized the pair. Giton’s cries of pain and his body gave him away. And Lichas took one look at Encolpius’ penis and realized who was aboard his ship.

A general fight erupted, and the only one who didn’t participate was the ship’s navigator. There were no fatalities, and afterward the old tutor had everyone aboard sign a peace treaty. Giton and Encolpius were given wigs and fake eyebrows so that they wouldn’t look so odd. With the ship now reconciled, the old tutor told everyone a story. The story was about a singularly loyal wife who went for five days without food after the death of her husband. A soldier, stationed nearby, had been directed to keep an eye on some men who had been crucified. And instead, the soldier took it upon himself to try and get the moribund widow to eat something. She did, finally, and soon thereafter she also succumbed to his attempts at seduction, and they made love several nights in a row behind the closed doors of her husband’s tomb. Meanwhile, one of the crucified men whom the soldier had been stationed to guard was taken down and buried by his parents. That meant that the soldier was in trouble – surely he’d be punished due to the missing body. And so the widow, not wanting to lose her new lover as well as her husband, had the soldier put her husband’s corpse up on the cross to stand for the missing criminal. And this story, believe it or not, elicited great laughter aboard the decks of Lichas’ ship. Nothing funnier than a tale involving voluntary starvation, graveside sex, and a hilarious crucifixion body swap, in my opinion.

Shortly after the old tutor’s hilarious slash offensive yarn, a storm rose over the ocean. Lichas, again the ship’s owner to whom Encolpius had done wrong at some point, was blown off of the ship and went under the ocean. Then the whole ship came apart in a chaotic flurry, and when the storm subsided, fisherman picked through the debris and discovered the survivors. [music]

Landfall in Southern Italy

After the shipwreck, Encolpius, Giton, and the old tutor who had fallen in with them found themselves in a fisherman’s cottage. Encolpius was saddened to discover the remains of his former foe Lichas had floated to shore. He delivered a long, overblown eulogy to the dead man, the general thrust of the speech being the hackneyed sentiment that fortune raised people up and lowered them, and no one was immune. After Lichas was cremated, Encolpius and his companions sought high ground to try and determine where they’d washed up.They saw a small city and learned from a local farmer that it was called Croton. Croton, the farmer said, was no place for people with real ambition – it was a place of hacks, tricksters and thieves – a place of total vice and where there was nothing good to be found. Croton, by the way, is on the toe of the Italian boot and it had once been an important Magna Graecian city, but had fallen by the wayside by the time of the late Julio-Claudian dynasty.

Eumolpus’ Poem

Now, at this point, the old tutor who has joined Encolpius becomes a full-fledged character in his own right. His name, Eumolpus, is confusingly similar to Encolpius’ name, so we’ll call him “the tutor Eumolpus.” The tutor Eumolpus and his companions, including Encolpius, began to plan an elaborate ruse on the way to Croton – missing passages make the details puzzling. But on the way there, the tutor Eumolpus offered a characteristically long recitation of a poem about the civil wars that had ended the republic.In his long poem, old Eumolpus painted a picture of the late republic as effete and electorally corrupt. In the midst of this degeneration, the tutor Eumolpus said, greed had increasingly taken hold, and military forces had become increasingly independent and powerful. At the core of the old tutor’s fatalistic account of the republic’s death is a story about the god of the underworld Pluto giving a report to the goddess Fortune. Pluto said, in the Sullivan translation,

O mistress of all divine and human things,

Hater of all security of power,

Lover of the new, forsaker of triumphs,

Art thou not crushed

By the weight of Rome?

Canst thou raise higher that doomed mass?

The new generation frets at its strength,

Burdened by accumulated wealth.

See, everywhere rich pickings of victory,

Prosperity raging to its ruin.

They build in gold and raise their mansions to the stars.

The seas are dammed by dykes of stone

And other seas spring up within their fields –

A rebellion against the order of all things.

The tunneled earth yawns under insane buildings;

Caverns groan in hollowed mountains. (113)

The goddess fortune, hearing these remarks, said that she recanted her blessings on the Roman republic and would follow them with harsh punishments, foreseeing bloody fields at Philippi and great carnage at Actium.

Soon thereafter, said the old tutor Eumolpus in his poem, Caesar came back from Gaul, and the whole earth rumbled as he began the civil war. The poem describes Caesar stalking down from the icy peaks of the Alps with melodramatic allusions. And as Pompey, too, geared up for war, Eumolpus narrates, “a great infection spread even to the skies, / The timorousness of heaven set the seal on flight. / And through the world a gentle host of gods, / Abominating earth’s madness, abandoned earth, / Avoiding the armies of the doomed” (120). The old tutor Eumolpus kept up his spirited narrative until the civil war got started in earnest and the travelers reached the city of Croton. Stylistically, Eumoplus’ poem is a satire on the excesses of bad poetry – melodramatic, pretentious, and bromidic. While his style undermines the gravity of his story, Eumolpus’ story is a laughably unfitting piece of poetry within the greater Satyricon – nearly 450 lines of epic verse that take us to the verge of the crisis, and thus the arrival at a small lodging house in Croton is pointedly anticlimactic.

Now, the plan in Croton was for the old tutor Eumoplus to pose as a very rich man with a company of slaves – a very rich man who was ailing and possibly looking for legacy hunters. There’s a gap in the manuscript, and suddenly Encolpius is talking with the maid of a wealthy woman named Circe. Now, Encolpius is dressed as a slave in this scene, and this wealthy woman Circe has a thing for sex with husky slaves and laborers. After first attempting to flirt with Circe’s maid, Encolpius asked the maid to bring him to the mistress, and soon found himself standing in front of a ravishingly beautiful woman.

Encolpius’ Tryst with Circe

There was some verbal foreplay. Circe told him he could keep his male lover on the side – she didn’t mind. Encolpius said that wouldn’t be necessary – he would be devoted to her exclusively. The couple began making love in a grassy clearing. But there was a problem – Encolpius wasn’t having any luck getting an erection. Circe wondered if she’d done something wrong. Giton showed up later and told Encolpius he appreciated Encolpius never going all the way with him, revealing that impotence has been a problem for Encolpius for a long time.Later, Circe wrote to Encolpius. She told him she was offended, but still interested in sex with him. She recommended that he not sleep with Giton for a few days, and then come back to her and give it another try. Encolpius didn’t hesitate to reply. He told her that he, too, was disgraced by the incident, adding the euphemism that “The soldier was ready, but had no weapons” (128). He offered her more conjectures about why he’d been unable to perform, and asked for opportunity to try again.

Encolpius’ Anatomical Problems

So, that evening, Encolpius ate foods purported to increase virility. He drank moderately and avoided his lover Giton. The next day, Encolpius went to try and have sex with Circe again. Circe’s maid brought with her an old woman who cast a sort of virility spell on Encolpius, which successfully resulted in a substantial erection. Encolpius met with Circe thereafter, but in a confusing episode probably caused by missing manuscript lines, Circe was soon furious at him once more, and Encolpius found himself back in his hotel, alone with his uncooperative penis. Encolpius considered resorting to drastic measures. In a poem, he records contemplating cutting off his treasonous member. As William Arrowsmith translates, Encolpius reports,Three times with razor raised I tried to lop;

three times my trembling fingers let it drop,

while he, as limp as cabbage when it’s boiled,

with prickish fright my purpose foiled.

For, cold as ice, he shrank, too scared to watch,

and screwed his crinkled length against my crotch,

so cramped along my gut, so furled and small,

I could not see to cut at all. (163)

What a terrific translation. Since he found he couldn’t cut his own penis off, Encolpius decided to turn his verbal wrath on the offending organ. In the Sullivan translation, Encolpius looks at his penis and says,

What have you got to say?. . .You insult to mankind, you blot on the face of heaven – it’s improper to give you your real name when talking seriously. Did I deserve this from you – that you should drag me down to hell when I was heaven? That you should betray me in the time of life and reduce me to hell when I was in heaven? That you should betray me in the prime of life and reduce me to the impotence of the last stages of senility. . .[and later Encolpius tells us] Once this vile abuse was finished, I too began to feel regret – for talking like this – and I blushed inwardly at forgetting my sense of shame and bandying words with a part of the body that more dignified people do not even think about. (131)

It had all, Encolpius said, been normal, though, hadn’t it? People got mad at offending parts of their bodies. Encolpius later asked Giton if Ascyltus had had sex with him, and Giton said indeed, they had not had sex.

Now, you might think that this episode, with beautiful Circe and Encolpius’ flaccid penis, has drawn to an almost-endearing close. It hasn’t. Things are about to get weirder. Earlier, Encolpius was given a brief sexual therapy session by an old woman employed by Circe. This woman suddenly showed up again, talking as she entered. “Were they witches who enervated you?” she asked. “Did you tread on some shit in the dark at a crossroad? Or a corpse. You haven’t even rescued yourself from the boy. Instead, you’re soft, weak, and tired, like a cart-horse on a slope; you just wasted all this effort and sweat” (134). Encolpius was then led into a different room, thrown on a bed, and whipped.

The Elderly Priestess Tries to Arouse Encolpius

An indeterminate period of time later, after a manuscript break, Encolpius was confronted with a new challenge. This challenge was that an elderly priestess of the fertility god Priapus planned to sleep with him. She vowed that she would have no problem making Encolpius’ sex organ function in its intended manner. The old priestess recited an incantatory verse first, and then got down to business, kissing Encolpius on the bed for a while and then beginning some ritual preparations. In order to prepare for the sexual encounter, the priestess got a kettle, a piece of pig leather, and some beans. She instructed Encolpius to peel the beans. Nothing says foreplay like peeling beans in the bedroom with a senior citizen fertility priestess, of course, but Encolpius was a little too slow, and so the priestess took over the job for him.

The arrival in Croton takes Encolpius and his companions to the periphery of the Italian Peninsula, but Croton is no aristocratic hideaway like the one shown here – instead it’s a grimy hive of swindlers and opportunists. The painting is Gustave Boulanger’s Theatrical Rehearsal in the House of an Ancient Roman Poet (1855).

The old prietess demanded to know where the beans were. Encolpius told her – geese had attacked him, he said! They’d stolen the beans, but he’d slain one of them. The priestess was appalled and incensed – the goose was the god Priapus’ favorite, she said! Encolpius should be crucified. The priestess tried to decide what to do, but Encolpius set down some money in order to smooth things over. And indeed Encolpius’ sudden payment had a remarkable effect. The old woman was pacified. She cooked the goose. She gave Encolpius strong wine. But the old priestess of Priapus wasn’t entirely placated by Encolpius’ largesse. On the contrary. While he was under the influence of drink, the priestess got a leather dildo, oiled it and covered with pepper and nettle, and stuck it up Encolpius’ behind. She sprayed his genitals with a similar skin irritant. Soon, the demoralized Encolpius was dashing away for his life, the priestess chasing him for a few blocks. And when he got back to his inn, Encolpius was distraught to discover that Circe’s maid, for whatever reason, now desired him, and wouldn’t take no for an answer.

The final connected fragment of the Satyricon continues the narrative in Croton. Encolpius and his companions are pretending to be the attendants of a wealthy old tycoon. A local mother – a former prostitute, we gather, made money through the work of her son and daughter, and these she dropped off at the quarters of the old tutor Eumolpus, who is pretending to be the wealthy old tycoon. This is going to get nasty and X-rated for a moment, so bear with me. Eumolpus wanted to have sex with the girl, but he was also pretending to be old and suffering from a mobility problem in his loins. And so he had the girl climb up on him while both were naked while the girl’s brother, under the bed, moved the old tutor Eumolpus’ hips by pressing his legs up under the mattress beneath Eumolpus’ pelvis. The tutor Eumolpus enjoyed sex with the girl a few times in this way. Encolpius, ever the gentleman, was amused at the spectacle, and decided to have sex with the brother, but persistent erectile dysfunction prohibited him from doing so. That, effectively, ends the Satyricon as it stands today as a connected narrative – there are a few more verses that seem to be about the old tutor Eumolpus’ pretensions as an elderly rich man, and Oscar Wilde wrote his own brief wrap up to the story that we’ll talk about later, but with an incestuous threesome and a persistently flaccid hero, the Satyricon comes to a perhaps fittingly bizarre and anticlimactic end. [music]

The Author Petronius as He Appears in Tacitus

And that, folks, was the Satyricon. Love it or hate it, there’s nothing else like it in Roman literature. Before we call it a day, there are a few things we should discuss in regards to this remarkably distinct book. One of them is the book’s author. And the other, which we’ll get to in a minute, is the book’s literary influence. Just as Senecan drama didn’t get to enjoy its day in the sun until perhaps 1,500 years after its composition, the Satyricon came into the mainstream in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Scholar Helen Morales unambiguously calls the Satyricon “the most controversial work in the classical literary canon,” and while some in the past century and a half have found Petronius’ book unredeemable smut, others have seen Petronius as a pioneer to be revered and emulated.8

In large part our general sense of Rome as decadent and hedonistic comes most from Petronius’ generation and the one that came after it. Christian authors like the ones who wrote Revelation, alongside Tacitus, Petronius, and Juvenal saw Nero’s Rome as a vast, rotten thing, either fallen from a glorious past or soon to be overtaken by a purer and more pious future. The painting is Wilhelm Otto Peters’ Nero at the Circus (1900).

Petronius was more than this, however – more than a shrewd dandy filling a niche in the court of an egomaniac. Petronius was, as the historian Tacitus tells us, a real aristocrat who, notwithstanding his elegance and refinement, met his death with a chilly indifference that would have made his contemporary Seneca envious. Most introductions to the Satyricon offer you two paragraphs from Tacitus’ Annals on the subject of Petronius and his life – I’ll quote those two paragraphs in full for you now. Long quote, and this is the John Jackson translation, published by Delphi Classics in 2014.

Petronius calls for a brief retrospect. He was a man whose day was passed in sleep, his nights in the social duties and amenities of life: others industry may raise to greatness — Petronius had idled into fame. Nor was he regarded, like the common crowd of spendthrifts, as a debauchee and wastrel, but as the finished artist of extravagance. His words and actions had a freedom and a stamp of self-abandonment which rendered them doubly acceptable by an air of native simplicity. Yet as proconsul of Bithynia, and later as consul, he showed himself a man of energy and competent to affairs. Then, lapsing into the habit, or copying the features, of vice, he was adopted into the narrow circle of Nero’s intimates as his Arbiter of Elegance; the jaded emperor finding charm and delicacy in nothing save what Petronius had commended. His success awoke the jealousy of [another aristocrat] against an apparent rival, more expert in the science of pleasure than himself. [Petronius’ rival] addressed himself, therefore, to the sovereign’s cruelty. . .

In those days, as it chanced, [Nero] had migrated to Campania; and Petronius, after proceeding as far as Cumae, was being there detained in custody. [Petronius] declined to tolerate further the delays of fear or hope; yet still did not hurry to take his life, but caused his already severed arteries to be bound up to meet his whim, then opened them once more, and began to converse with his friends, in no grave strain and with no view to the fame of a stout-hearted ending. He listened to them as they rehearsed, not discourses upon the immortality of the soul or the doctrines of philosophy, but light songs and frivolous verses. Some of his slaves tasted of his bounty, a few of the lash. He took his place at dinner, and drowsed a little, so that death, if compulsory, should at least resemble nature. Not even in his will did he follow the routine of suicide by flattering Nero. . .or another of the mighty, but — prefixing the names of the various catamites and women — detailed the imperial debauches and the novel features of each act of lust, and sent the document under seal to Nero. His signet-ring he broke, lest it should render dangerous service later. (An 16.181-200)9

It’s a fascinating little section of Tacitus’ Annals. Amidst the mass casualties of Rome in the mid-60s CE – the deaths of St. Paul and Peter, the imperial purges that resulted in the suicides of the great writers Seneca the Younger and his nephew Lucan, Tacitus offers us a short account of an elegant courtier’s last hours. Whatever its historical accuracy, there is something remarkably brave and iron willed about Petronius’ suicide as Tacitus tells it – the arbiter of taste, refusing to be humbled by his murderous emperor, died just after sending Nero a catalog of the emperor’s turpitudes to remind the last Julio-Claudian of who and what he was. Seneca’s suicide was tragically botched – an attempt by a stoic to be a sort of performance art piece on how stoics met death with brave equanimity that was interrupted by imperial proclamations and drawn out to a gruesome extent. Petronius, who to our knowledge never voiced any pretensions of manly philosophical hardihood, cut his wrists, had dinner and wine as he always did, and offered Nero a letter reminding the emperor that he was a perverse buffoon, and that everyone knew it. Of the two deaths as Tacitus tells them, Petronius’ demise seems a far more efficacious example of psychological resilience under duress.

The story of Petronius must have been the story of generations of educated aristocrats who had to somehow make a living under the Julio-Claudians after Augustus. Petronius’ readers have noticed a number of compelling parallels between Nero and Petronius’ character Trimalchio. Both, odd as this sounds to us, kept the trimmings of their first beard in a box made of gold. Both wear gold bracelets. Nero, like Trimalchio, had a ceiling that opened to dump presents on dinner attendees. Nero, like Trimalchio, had an acrobat tumble down on him, an incident which Suetonius recollects.10 Nero, like Trimalchio, was an imbecile with enormous power and wealth, grasping for artistic and literary legitimacy with his scandalous stage performances. Nero sung and acted and raced and played his lyre, just as Trimalchio pretends a knowledge of Greek poetry only to reveal that he has the facts laughably wrong. As Nero’s arbiter of taste, then, Petronius was in the ultimate position to satirize the emperor’s pretensions of culture. Trimalchio might attempt to quote a few lines of Greek poetry here and there, but at heart, he is a dimwit who suffers from constipation and wipes urine in his slave’s hair. Nero, by extension, with his dictatorial power and his dearth of real intelligence or education, was every bit as vulgar.

If the central scene in Petronius’ Satyricon is a satire of Nero on one hand, it is much more obviously a disparagement of Rome’s flashy parvenus. Newcomers to wealth, Petronius reminds us, might command formidable fortunes – but they lack the sheen of real bluebloods – of old consular families like, perhaps, Petronius’ own. When we see Petronius satirizing Trimalchio, then, as hilarious and spectacular as the great feast scene indeed is, we also see a fundamentally conservative impulse at work. Newcomers to wealth, if they’re anything like Trimalchio, are an unbearable lot, drinking so much and eating such fine cuisine that they choke on their own pretentiousness. While admittedly, Trimalchio, like his successor Jay Gatsby, has his own kind of curious attractiveness, he is by and large an abject and absurd figure – a man who wants to appear a self-made magnate and polymath, but instead appears a constipated old imbecile.

Petronius, then, like many aristocrats of the first century CE, found themselves pressed from above by the Julio-Claudians and their lackeys, and pressed from below by new money upstarts trying to buy their way into the old aristocratic order. For centuries during the republic, Rome had been governed by an oligarchy, and not a dictatorship, and the institutions, and connections that turned the motor of this oligarchy persisted through much of the imperial period. The educational institutions, and clans, and careful intermarriages of Rome’s old order continued to operate while at the same time it became clear that emperors, and warlords, and capitalists were the new rulers of Rome. And while we needn’t subscribe to Petronius’ disparagement of new money, it’s hard not to feel a little bit of pity for the Silver Age aristocrats who saw their rich old culture disintegrating. As an imperial arbiter of taste, Petronius was at worst a court fop – on the surface a coxcomb catering to the emperor’s appetites and lusts, and as such he had fallen far from the days when former consuls governed provinces and wielded legislative power from the benches of the senate. Yet at the same time, Petronius survives today as a powerful documentarian and social critic. Amidst the heady court culture of wine and sex, Petronius kept his wits about him, writing about Roman luxury and vice with prolific detail, and authoring a huge story that was at once an offbeat picaresque and at the same time an indictment on the excesses of his own times. [music]

Petronius’ 19th-Century Proponents

When we study Roman literature, we generally reach Petronius late in the game, some time after the blockbusters of Cicero, Virgil and Ovid, and if we’re not careful, the great Silver Age Latin satirist can seem like an endnote to his predecessors. Yet, as we learned in our recent programs on Senecan drama, sometimes, works not very famous in their own age can nonetheless resurface in a later period of literary history and suddenly take on a great importance. Now, if you come to classics with a path like mine – in other words through later Anglophone literature – you’re likely to first encounter the name of the Satyricon in a novel that’s totally unavoidable for the modern English major. Extra points if you know where this quote is coming from – my hint is that the novel was published in 1890.For while he was but too ready to accept the position that was almost immediately offered to him on his coming of age, and found, indeed, a subtle pleasure in the thought that he might really become to the London of his own day what to imperial Neronian Rome the author of the ‘Satyricon’ had once been, yet in his inmost heart he desired to be something more than a mere arbiter elegantiarum.11

The quote comes from the pen of an author who translated Petronius’ Satyricon. His translation of the Satyricon, published in 1902, was the first English translation to be issued in some 150 years, and it didn’t censor the book’s notorious sexual episodes.12 The 1902 translation was published under the pseudonym of Sebastian Melmoth. Sebastian Melmoth was the pseudonym of Oscar Wilde, and the novel I quoted was his Picture of Dorian Gray. There are obvious reasons why Wilde would publish an unexpurgated version of the Satyricon toward the end of his life. He had spent two years in prison for his illicit relationship with the younger aristocrat Lord Alfred Douglas. The Satyricon, as you saw today, unmistakably shows that homosexual relationships were a pervasive and accepted part of ancient Roman culture, rather than some newfangled modern fad, and thus the Satyricon deserves its place, in scholar Helen Morales’ words, as “in the modern world, a classic of gay fiction.”13

Petronius and the 19th-Century Decadent Movement

Charles Baudelaire (1821-67) championed artifice over nature, influencing a whole artistic movement that prized the extravagant lacquer of civilization over the raw materials of mountains and forests.

When this generation of late-nineteenth-century writers looked back into antiquity, they found, in Silver Age Latin, a period of literature that spoke to them. Baudelaire did not share William Wordsworth’s appetite for grassy clearings and the undiluted purity of childhood. Nor, as it turned out, would Romans of the early empire have. The child mortality rate of the later Nerva-Antonine dynasty was quite high. Four to five in ten Roman children did not make it to the age of eight.14 As a result, in particular elite Romans, whose children were cared for by wet nurses and slaves, were less likely to try and develop close relationships their young children. Additionally, the fact that they could always adopt heirs made genetic lineage through childbearing much less of a central cultural issue than it has been in different places and times in history. Scholar Frank McLynn, after summarizing the child mortality rates of the early empire, describes “a general Roman cast of mind – anti-Wordsworthian, one might say – whereby childhood was thought to contain nothing of value. [Emperors] and Romans in general were uninterested both in their own childhood and in the world of the child.”15 A lack of interest in children and the usual tropes of innocence and purity that they bring in literary history freed moneyed Romans of Petronius’ generation from familial roles, if they wanted to be freed, to pursue the sorts of intrigues, pleasures, and self-fashioning that Baudelaire praised as the highest aims of humanity.

A generation after Baudelaire, one of the most fascinating and unique figures in 19th-century European literature began to take earlier French poetry’s ideas to their logical conclusion. His name was Joris-Karl Huysmans, and between 1880 and his death in 1907, Huysmans wrote some of the most influential and astoundingly crafted novels Europe ever produced. I want to tell you a bit about Joris-Karl Huysmans, now – again, a French writer active in the last couple of decades of the 1800s, because, as we’ll see, Huysmans was instrumental in bringing the Satyricon back to life at the turn of the 20th century, and awakening a popular interest in the Silver Age Latin literature we’re currently studying together.

Huysmans’ Des Esseintes Opines on Latin Literature

The first person speaker of Joris-Karl Huysmans’ most famous novel, À Rebours (1884), was a whole new archetype in literary history. The first person speaker of Huysmans’ 1884 novel, whose name is Jean des Esseintes, is the paradigmatic aesthete – a shut in, misanthropic character whose lack of adventurousness is matched by his superhuman erudition. Little happens in Huysmans’ famous novel – his protagonist meanders through various readings and artistic projects and recollects some torrid affairs from earlier in his life. But in spite of a lack of captivating plot in the traditional sense, À Rebours was extremely well received, its most famous fan, perhaps, being Oscar Wilde himself. As Wilde biographer Richard Ellman writes, while Wilde, in the mid 1880s, had not yet broken with social conventions in the way he eventually would, Huysmans’ novel became his bible, and invited him to be himself at any cost. The title À Rebours, after all, is often translated as “against the grain,” or “against nature.” And a growing intellectual and artistic tradition – one that Charles Baudelaire had spearheaded in the previous generation – a tradition that denied the notion that nature was most true and most beautiful, was becoming central to the aesthetes of the 1890s. Huysmans’ speaker, at one point, remarks, “Nature. . .has had her day; she has finally and utterly exhausted the patience of sensitive observers. . .what a monotonous store of meadows and trees, what a commonplace display of mountains and seas!”16 This notion – again, that artifice is more beautiful than nature, is central to the decadent movement in literary history, a movement that scholar Robert Baldick describes as “characterized by a delight in the perverse and artificial, a craving for new and complex sensations, a desire to extend the boundaries of emotional and spiritual experience.”17 Oscar Wilde’s character Dorian Gray, who reads and reveres Huysmans’ À Rebours just as much as Wilde himself did, is literature’s ultimate decadent character – one whose famished cravings for new sensations ultimately rot him to the core.In moving from the Satyricon, to Wilde’s translation of it, to Wilde’s favorite book, it may seem we’ve gone a bit far afield from Petronius, but actually, we haven’t. Because it was Huysmans who introduced Wilde’s entire generation not only to Petronius himself, but to the period of later Latin literature that we’re currently studying in our podcast. Golden Age Latin literature, to Huysmans, was a marionette show of outworn figures and tropes – Achilleses and Medeas whose unending franchises had to be cut off for something literarily new to happen. After Ovid, though – to Huysmans, at least – Latin literature reached a point of sophistication and fermentation that made it a truly rich and vibrant subject of study. Now, I want to read you a couple of long quotes from Huysman’s novel À Rebours, or Against Nature – quotes that have to do with works of Roman literature that we’ve studied. The first is a long and entertainingly disparaging account of Virgil and his immediate predecessors, and remember that the main and really the only character of this 1884 French novel is called Jean des Esseintes. This is the Robert Baldick translation, published by Penguin Classis in 1959.

Among other authors, the gentle Virgil, he whom the schoolmastering fraternity call the Swan of Mantua, presumably because that was not his native city, impressed [Des Esseintes] as being one of the most appalling pedants and one of the most deadly bores that Antiquity ever produced; his well-washed, beribboned shepherds taking it in turns to empty over each other’s heads jugs of icy-cold sententious verse, his Orpheus whom he compares to a weeping nightingale, his Aristaeus who blubbers about bees, and his Aeneas, that irresolute, garrulous individual who strides up and down like a puppet in a shadow-theater, making wooden gestures behind the ill-fitting, badly-oiled screen of the poem, combined to irritate Des Esseintes. He might possibly have tolerated the dreary nonsense that these marionettes spout into the wings; he might have excused the impudent plagiarizing of Homer, Theocritus, Ennius, and Lucretius. . .[Des Esseintes] might have put up with all the indescribable fatuity of this rag-bag of vapid verses; but what utterly exasperated him was the shoddy workmanship of [Virgil’s] tinny hexameters, with their statutory allotment of words weighed and measured according to the unalterable laws of a dry, pedantic prosody; it was the structure of the stiff and starchy lines in their formal attire and their abject subservience to the rule of grammar; it was the way in which each and every line was mechanically bisected by the inevitable caesura and finished off with the invariable shock of dactyl striking spondee.

Borrowed as it was from the system perfected by Catullus, that unchanging prosody, unimaginative, inexorable, stuffed full of useless words and phrases, dotted with pegs that fitted only too foreseeably into corresponding holes, that pitiful device of the Homeric epithet, used time and again without ever indicating or describing anything, and that poverty-stricken vocabulary with its dull, dreary colours, all caused [Des Esseintes] unspeakable torment.

It is only fair to add that, if his admiration for Virgil was anything but excessive and his enthusiasm for Ovid’s limpid effusions exceptionally discreet, the disgust [Des Esseintes] felt for the elephantine Horace’s vulgar twaddle, for the stupid patter he keeps up as he simpers at his audience like a painted old clown, was absolutely limitless.18

So much of what you just heard checks the boxes of decadent prose – long sentences with multiple dependent clauses, dense and carefully selected diction, erudition and restless dissatisfaction – I mean Des Esseintes spends this entire novel being furiously dissatisfied with most of what he encounters and then finding one or two things, however unlikely and unexpected, that satisfy him. And again, while Des Esseintes, again the character of the French writer Huysmans’ 1884 novel, finds Virgil and Horace pitiful, and Ovid only slightly better, he finds Petronius, on the contrary, much to his liking. After bashing the Augustan Age poets, and then deeming Cicero, Caesar, Sallust, Livy, Seneca, and Tacitus nearly worthless, Des Esseintes identifies Petronius’ Satyricon as a work of altogether different quality. Here’s the great decadent protagonist Des Esseintes – another long quote and this is again the Robert Baldick translation.

J.K. Huysmans (1848-1907), one of the most original and erudite figures of nineteenth-century European literature, had a fascinating and unique perspective on classics, presenting some of his viewpoints through his character Des Esseintes in the 1884 novel À rebours. The novel discusses Petronius’ Satyricon.

The author [that Des Esseintes] really loved. . .was Petronius.

Petronius was a shrewd observer, a delicate analyst, a marvelous painter; dispassionately, with an entire lack of prejudice or animosity, he described the everyday life of Rome, recording the manners and morals of his time in the lively little chapters of the Satyricon.

Noting what he saw as he saw it, he set forth the day-to-day existence of the common people, with all its minor events, its bestial incidents, its obscene antics.

Here we have the Inspector of Lodgings coming to ask for the names of any travelers who have recently arrived; there, a brothel where men circle round naked women standing beside placards giving their price, while through half-open doors couples can be seen disporting themselves in the bedrooms. Elsewhere, in villas full of insolent luxury where wealth and ostentation run riot, as also in the mean inns described throughout the book, with their unmade trestle beds swarming with fleas, the society of the day has its fling – depraved ruffians like Ascyltus and Eumolpus, out for what they can get; unnatural old men with their gowns tucked up and their cheeks plastered with white lead and acacia rouge; catamites of sixteen, plump and curly-headed; women having hysterics; legacy-hunters offering their boys and girls to gratify the lusts of rich testators, all these and more scurry across the pages of the Satyricon, squabbling in the streets, fingering one another in the baths, beating one another up like characters in a pantomime.