Episode 73: The Golden Ass

Apuleius’ The Golden Ass is Ancient Rome’s only novel to survive in full – a strange, often disturbing fairytale that had a huge influence on posterity.

| Read Transcription | References and Notes |

| Episode Quiz | Episode Song |

| Episode on Spotify | Episode on Apple Podcasts |

| Previous Show | Next Show |

Apuleius’ The Golden Ass

Hello, and welcome to Literature and History. Episode 73: The Golden Ass. This program is on one of the earliest full novels that has come down to us from antiquity, a rollicking adventure story called The Golden Ass, written by a Roman provincial author named Apuleius, likely some time in the 160s CE.1 In a sentence, the novel is about a strapping young adventurer named Lucius who wants to learn about magic and witchcraft, ends up being transformed into a donkey, has a long series of perilous adventures, and in the end, is able to change back into his human form through the aid of the goddess Isis. While the story of Lucius’ transformation and redemption is the main narrative thread of the novel, The Golden Ass is embroidered from beginning to end with dozens of inset narratives, the lengthiest of which, a 50 or so page long treatment of the myth of Cupid and Psyche, is a novella in its own right.

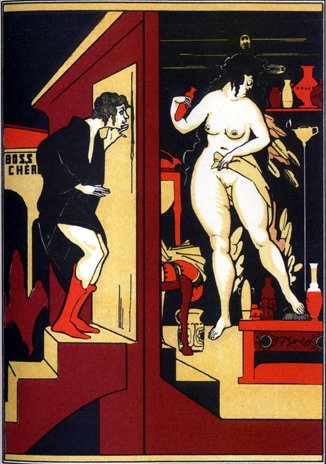

Apuleius is the central figure in this frontispiece to an 1866 edition of The Golden Ass, which also shows Pamphile changing into an owl (upper left) and Lucius as a donkey (lower right).

If there is a general unifying characteristic in all of these early novels, it is the story of young people, cast adrift in a dangerous world, who, after surviving a series of dire adventures, find happiness and security. Early novels often involve romances – couples who fall in love, become separated, and then, after braving long journeys, villainous adversaries, and navigating their way through strangers and harsh elements, are eventually reunited. As such, the earliest novels, following the paths of the romantic comedies of Plautus, Terence, and the mostly lost genre of Greek New Comedy, look far more like novels by Charles Dickens than the Homeric epics or Sophoclean tragedies. When we open Apuleius, specifically, although The Golden Ass is a long and frustratingly meandering book sometimes, all of a sudden we catch whiffs of literary genres thousands of years in the future – the Medieval dream vision, the miscellanies of Chaucer and Boccaccio, the picaresques of Daniel Defoe and Henry Fielding, and more.

There is something about the formal flexibility prose novel that, in itself, seems to encourage artistic evolution. The American author Henry James, in 1890, famously called the novels of his century “loose baggy monsters, with. . .queer elements of the accidental and the arbitrary.”2 Considering the enormous novels of Leo Tolstoy and Victor Hugo, Henry James marveled that genre could be as popular as it was lumpy and inefficient. But this lumpiness and inefficiency, whether in the nineteenth century or the first or second centuries, encourages excursions and experiments. Lacking the metrical constraints of poetry and the time constraints of drama, prose fiction is free to entwine stories within stories, creating tangents which spin off into entirely new genres. Diverse, large, and full of endless potential, novels have dominated literary history since the nineteenth century. But this was hardly always the case. If literature is a triptych, with poetry on the left panel, drama in the center, and prose fiction on the right, for most of recorded history, prose fiction has been a dark horse in the shade of the other two. Novels are too long to practicably copy without a printing press, they can’t really be staged publicly, and their baggy structure makes them more likely to be the entertainment of the solitary and unoccupied than the boisterous ensemble. The fact that they are to be consumed by solitary readers presupposes a literate reading public in the first place, and the history of the novel is braided together with the rise of broad based public education systems in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries and afterward. When we read the first surviving novels, then, as we’re doing today, we see literature’s ultimate sleeper hit – a form of artistic expression that goes back at least 2,000 years, and that suddenly, over the past 200, has burst forward to relegate poetry and drama to the domains of the initiated and the specialist.

A minute ago, I mentioned a number of Ancient Greek novels, mostly from the years between 50 and 250 CE. We will have an entire bonus series coming up on the genre of the Ancient Greek novel – a genre that to this day remains astonishingly unknown and understudied. These novels, though some of them indeed sound like someone sent Charles Dickens back in time and gave him a papyrus and an amphora full of mixed wine, were lost to much of literary history, influencing Byzantine prose works during the 1100s before gradually reemerging into Europe over the course of the sixteenth century. Apuleius’ novel The Golden Ass, however, is a different case, having been a constant presence in European literary history from the moment of its birth up until today. As we’ve learned, Latin became the sacred language of Europe, Greek manuscripts gradually fell by the wayside, and for over a thousand years, the works of even Silver Age Latin writers like Juvenal and Apuleius, peculiarly, were far better known than the Homeric Epics and the tragedies of ancient Athens. For many readers, then, The Golden Ass was the tap root of prose fiction, and the blueprint for how to write a long prose story.

But as you can imagine, being a Roman novel from the reign of Marcus Aurelius or thereabouts, The Golden Ass is hardly a piece of carefully orchestrated psychological realism like Henry James would write 1,700 years later. The Golden Ass is a circus of sex and violence, sprinkled through with witchcraft, prognostication, and so many stories within stories that at moments the main course of the novel is nearly shoved off the table by side dishes and garnishes. It is such a rambling book, and quite often such a bawdy book, that one of the central questions of its interpretation has been to decide whether it has any moral message to communicate at all. So in the remainder of this program, we’re going to learn all about the first Roman novel to survive in full – one which, because of the language of its composition and perhaps also because of the smutty nature of its contents, remained alive and well on monastery bookshelves right up until it began to be reprinted in early modern Europe. To begin our journey into this important novel, we should talk a bit about its author. [music]

Apuleius: North African Celebrity Scholar

Apuleius, like seemingly all famous Roman writers, was not from the city of Rome. He was born under the reign of the Emperor Hadrian, some time in the mid-120s CE, in a colony called Madauros, in the far northeastern part of modern day Algeria, about fifty miles inland from the southern Mediterranean. He is the second African author we’ve met in this podcast, provided that Terence was, in fact, from Carthage. Anyway, Apuleius’ father was one of the two leading officials of the colony, and his income allowed him leave Apuleius and Apuleius’ brother a sizable legacy – nearly two million sesterces. As a young man, Apuleius would have known both Latin and the regional language of Carthaginian – Apuleius’ education began at Carthage and continued later at Athens, and from the beginning, he seems to have been fond of philosophy. Living and working in Athens during a portion of his twenties afforded Apuleius fluency with Greek language and culture as well.

An ancient theater built in the Roman-Berber city of Madauros, in modern day Algeria – Apuleius’ home town.

So following his acquittal, Apuleius returned to Carthage, where, growing ever more famous as an author and orator, he taught until the late 160s, and possibly a while thereafter. He was sufficiently well known that a statue of him stood in Carthage, and similar sculptures of the author were put up in other cities.

As an intellectual, Apuleius seems to have been extraordinarily versatile and prolific. The wellspring of Apuleius’ output was a dedication to Platonic philosophy, and Platonism certainly informs the pages of his novel The Golden Ass. But in addition to Platonic philosophy and fiction, Apuleius also wrote lyric love poetry, literary criticism, religious hymns, and works on agriculture, medicine, trees, natural history, mathematics, music, and astronomy, not to mention a second romance in addition to The Golden Ass, which has not survived. Most of Apuleius’ output has not made it down to us, but a small set of works are still extant, other than The Golden Ass. We won’t cover these other works in Literature and History, but they are a fascinating little quintet of texts, so let’s quickly talk about Apuleius’ other surviving works before we take a deep dive into his most famous one.

Apuleius’ book Plato and His Doctrines is probably the least surprising of the set. Summarizing some aspects of Platonic philosophy and applauding the philosopher for the heroic life he led, Plato and His Doctrines is an important record of what philosophers call Middle Platonism – a period of Platonic philosophy from which not very much has survived. Along these same lines, Apuleius’ work On the World explores theological questions and theorizes about how the world’s creation may have occurred, arguing for the existence of a sort of stoic prime mover deity and praising this god’s many aspects.

A 15th-century French illustration of Apuleius offering advice on how demons might be used as intermediaries between humanity and the gods. Apuleius De deo Socrates, which survives, is a treatise on supernatural beings, demons included.

Finally, Apuleius’ De deo Socratis, or “On Socrates’ God” is the Greco-Roman world’s only surviving treatise on supernatural entities. Beginning with the souls housed in the bodies of humans, Apuleius then goes on to talk about sentient creatures who inhabit physical forms but are not human, and finally, disembodied entities epitomizing abstract characteristics – sleep, for instance, and love, and hunger. It’s a unique work in that it catalogs a wide range of beings that occupy the space between the human and the divine.

The historical record overall, then, invites us to understand Apuleius as a prolific celebrity intellectual – a wealthy North African polyglot who worked in several different disciplines and whose ultimate devotion to Platonism drove much of what he was able to leave behind. The scholar, poet and translator Robert Graves theorizes that Apuleius became interested in writing novels because, like other philosophers-turned-novelists in literary history, “pious, lively, exceptionally learned, [they] found the popular tale gave them a wider field for their descriptions of contemporary morals and manners, punctuated by philosophical asides, than any more respectable literary form.”3

So now that we’ve talked a bit about early novels in general, and more specifically Apuleius himself, we’re almost ready to begin taking a look at The Golden Ass. Let me just tell you a couple of more things ahead of time. At the outset of this novel, Apuleius tells us he has written a fabulum Graecanicam incipimus, or an adaptation of a Greek tale in Latin. The Greek tale’s original name was evidently Lucius or the Ass, tale which survives in Greek in a short story by the confusingly named Lucian of Samosata, roughly a contemporary of Apuleius. Generally, scholars believe that Apuleius took a short story or myth, like the many that Ovid repurposed in the Metamorphoses, and blew it up into a full fledged novel.4 And speaking of the Metamorphoses, manuscripts of Apuleius’ novel often call it Metamorphoses – we only suspect that Apuleius might have called it Asinus aureus, or The Golden Ass, because Saint Augustine writes that this was so, and it’s certainly easier to give it a name that doesn’t confuse it with Ovid’s most famous work. So, in summation, The Golden Ass, like so many works from antiquity, was repurposed from an earlier work, and it was so focused on a central theme of transformation that it occasionally bore the same title as Ovid’s Metamorphoses.

There’s just a couple of more things we should cover before we dive in – this would be more relevant if you were reading the novel yourself, especially in Latin – and this is Apuleius’ style. The style of The Golden Ass is, in brief, grandiose, full of obscure words, outright neologisms, consonance, assonance, and extensive puns. The archaic and bombastic prose, rather than being a trademark of his style in all of his works, is intended as appropriate to The Golden Ass, specifically. The opening sentence of the novel is “Okay, let me weave together various sorts of tales, using the Milesian mode as a loom, if you will.”5 This mode, the Milesian mode, was associated with popular storytellers – Greek-speaking public orators whose florid language was used to entice the public into listening to their stories.6 And so while The Golden Ass is not without its solemnity – most notably its eleventh and closing book – the opening page of the story advertises it as the offering of a sort of fairground huckster. Listen to a tale of marvel and wonder, Apuleius tells us, dressed up in ostentatious language, a story bedecked with dozens of other stories, and toss a penny my way if you have one. Adopting the language and decorum of a street bard, then, Apuleius promises amusement more than edification.

Lastly, before we get started we should meet Lucius, the protagonist and first person narrator. Lucius is a young man of some means who travels to Thessaly, in the central part of the Greek mainland. In the opening of the novel, Lucius reaches his destination and provides a letter of introduction to a wealthy man named Milo. Lucius is a plucky, curious young man, and we soon learn that he has ulterior motives for staying with Milo – namely, a desire to learn more about magic from Milo’s wife, Pamphile. And though The Golden Ass has many inset narratives, Lucius is its main thread, and Lucius’ adventures, and his personal growth, the central things to pay attention to – Lucius, Lucius, Lucius.

So all of that should get you ready to enjoy the story, and the inset stories of Apuleius’ The Golden Ass, perhaps the most influential novel to survive from antiquity. Unless I’ve otherwise noted, quotes come from the Sarah Ruden translation, published by Yale University Press in 2010. Oh, and – um – sorry I have to keep saying this lately, but this episode is going to have quite a bit of adult content in it, so it’s likely not suitable for all ages – The Golden Ass is a fairytale, but it’s a Roman fairytale, so it’s kind of a fairytale with sex and violence, sort of like Game of Thrones, only with more comedy instead of ice zombies. Anyway, respectful warning aside – let’s open this thing and read it! [music]

The Golden Ass, Book 1

Apuleius’ famous novel begins, in the Sarah Ruden translation, as follows:Okay, let me weave together various sorts of tales, using the Milesian mode as a loom, if you will. Witty and dulcet tones are going to stroke your too-kind ears – as long as you don’t turn a spurning nose up at an Egyptian papyrus scrawled over with an acute pen from the Nile. I’ll make you wonder at human forms and fortunes transfigured, torn apart but then mended back into their original state. . . Now to my preface. Who the heck am I, you’d like to know. (1)

The narrator Lucius goes on to say that he is thoroughly Greek, and adds that he must be forgiven if his Latin is rough – he’s new to the language. He’s not only Greek, but the story about to be told is Greek, as well. Lucius claims to descend from great stock, which includes Sextus, a tutor of the Emperor Verrus, and then Sextus’ uncle, the biographer, historian and philosopher Plutarch. And it is at this point, really, that the narrative part of the novel begins.

Thessaly-Bound Travellers and the Tale of Socrates and the Witch

Lucius came down from the mountains of Thessaly and got off of his horse. As his animal grazed, Lucius joined two other travelers on the trail. The travelers were engaged in a rapt conversation, one of them expressing incredulity at the other’s words. With little hesitation, Lucius threw himself into the conversation – he’d seen some incredible things, he said, including a sword swallower in Athens. Whatever the one fellow had said that had elicited skepticism in the other fellow, Lucius promised to listen and believe it – and if he didn’t believe it, he’d buy the man lunch. And so, the tale-telling traveler commenced his story – the first of the dozens of embedded stories in The Golden Ass.

Apuleius wastes no time getting straight to a lurid story – the traveler’s account of his friend involves witches cutting a man’s throat and urinating on him.

Socrates said he’d gone to see some gladiatorial games and was robbed of everything he had. Socrates had gone for help to a lusty old innkeeper, who’d taken him to her bed and fleeced him of the money he earned while working as a porter. The traveler (once again the man narrating at this point), hearing his acquaintance Socrates’ story, was disgusted. “You preferred,” said the traveler, “cavorting with an old leatherhide whore to your own home and children!” (5). And at these words, Socrates had appeared mortified. The old innkeeper, he said, was an extremely powerful witch. She could transform people into animals, make anyone lust after her, teleport people wherever she wanted, and invert the very air and sky.

The traveler – again the man telling this tale of Socrates to the main character Lucius – the traveler said that upon hearing Socrates’ scary warnings about the innkeeper, he was afraid and had trouble sleeping. In the middle of the night, the door of their room smashed open, and the traveler was hurled onto the floor, his cot falling onto him and covering him from what happened next.

Two elderly women suddenly appeared. They talked about what to do with Socrates and the traveler, discussing various potential punishments, until shockingly, the old innkeeper sliced into Socrates’ throat, reached into the wound, and pulled out Socrates’ heart. One of them stuck a sponge into Socrates’ wound, and the two witches urinated on the traveler before leaving. The traveler was terrified – not only due to the heinous murder, but also because he feared that no one would believe his story and that he’d be implicated in killing Socrates. The witches, he realized, had left him alive only so that he’d be tried for murder and crucified!

Oddly, in this moment of duress, the traveler said he thought of his cot at the inn – the only witness that could prove his innocence. The traveler looped his cot’s threads into a rope and tried to hang himself with it, but the rope broke, and suddenly, Socrates woke up. The traveler realized he was saved! However it had happened, he would not immediately be charged with murder. The traveler and Socrates, after leaving their room at the inn, discussed the previous night, both speculating separately that they’d had far too much to drink. But soon the traveler learned that everything he’d seen had been real, after all. Because after he and Socrates had breakfast, when the impoverished man leaned over to drink from a brook, the wound in his neck suddenly gaped open, and he fell down dead. The traveler said that he’d fled after this – he’d exiled himself voluntarily to a different land, and remarried. And that was the end of his story. Now, we wonder, did Lucius believe this tale?

The traveler’s companion certainly didn’t. But as for Lucius, Lucius said, in the P.G. Walsh Oxford University Press translation,

I consider nothing impossible. . .for I believe that people undergo all that their fates decree. My view is that you and I and the whole world experience many strange, almost impossible happenings which lose their credibility when recounted to one who is unaware of them. Not only do I believe our friend [the traveller] – indeed I do – but I am most grateful to him for distracting us with such an amusing and elegant tale, so that I have completed this rough and extensive lap of my journey without strain or boredom.7

It’s a funny response, as it emphasizes that Lucius valued the tale as an interesting diversion more than, perhaps, a veracious factual narrative, and Lucius parted company with the two travelers, continuing onward on what would prove to be a great journey indeed.

Lucius Arrives in Thessaly

Lucius thereafter went to an inn, in search of a man named Milo. Milo, we learn, was an extremely rich, extremely stingy landowner, and Lucius had a letter of introduction to him. Lucius went to the wealthy Milo’s house, and he was admitted into the tycoon’s surprisingly minimalistic dining room. Milo made Lucius feel welcome and gave him quarters to stay in, and the young man made himself comfortable.When Lucius was out running errands later that day, he encountered an old friend named Pythias – an acquaintance from his student days in Athens. Pythias reproached a fishmonger who had evidently overcharged Lucius for Lucius’ meal, and the two men parted ways after Pythias pointedly had his footman stomp the fish apart in front of the bewildered fish merchant. This left Lucius puzzled and hungry. And when Lucius returned to wealthy Milo’s house, the rich man strong armed him into a lengthy conversation, during which Lucius grew more and more tired, until he finally went to bed. [music]

The Golden Ass, Book 2

Lucius Meets His Aunt Byrrhena

Lucius awoke early the next morning, eager to see the central district of Thessaly where he was now staying. Witchcraft, he tells us, originated in Thessaly, and the story he’d heard the previous day from the traveler seemed to corroborate this. Out walking in town, Lucius had another unexpected run-in – he met his aunt Byrrhena – his mother’s sister. Byrrhena invited him to stay with her during his time in Thessaly, but he said he was committed to lodging with wealthy Milo for the moment. Nonetheless, aunt and nephew wound up at Byrrhena’s home, a palatial property rich with marble statues. And since she happened to have him at her home, Lucius’ aunt Byrrhena gave him an earnest warning.Milo’s wife Pamphile, aunt Byrrhena said, was a witch. Aunt Byrrhena warned that “Just by puffing at sprouting twigs and gravel and what have you [Milo’s wife Pamphile] can take the light of the universe from the swarm of heavenly bodies and drown it all in primordial Chaos at the bottom of Tartarus” (24). And Lucius’ aunt warned him that Pamphile had a pronounced taste for handsome young men – young men just like him.

Lucius’ Tryst with the Slave Girl Photis

Lucius’ private reaction to his aunt’s warning is a little surprising. He tells us that “The moment I heard the word witchcraft, representing my lifelong aspiration, I shrugged off any need to play it safe with Pamphile; far from it, I was actually eager to sign up as her apprentice and pay through the nose for it, to go right ahead and take that flying leap into the abyss” (24). Having learned that indeed he was staying in the house of a real witch, Lucius parted company from his aunt and hustled back to Milo’s house. He resolved that he would begin attaching himself to Milo’s household by having sex with his slave girl, Photis. Lucius was a stunningly handsome young man, after all, and Photis had already shown interest in him the night before.Lucius found the slave girl preparing a meal and ogled her thoroughly. After an overture and some sultry flirtation, the couple kissed passionately for a few minutes and resolved to meet after dark. Over a long lunch, thereafter that day, Lucius talked to his host Milo and his hostess, the witch Pamphile, about an oracle from Babylon currently residing in Greece. Eventually, Lucius took his leave of the dinner table to go and meet with Photis. The slave girl had already prepared the room – blankets lined the walls to dampen sound, and wine and food were available. They kissed and drank and finally Lucius drew down his tunic in order to show that he was under considerable sexual strain. Photis felt the same way and, taking off all of her clothes, she got on top of Lucius on the bed and they made love until both were satisfied. They had sex several more times that night, and on subsequent nights, too. [music]

Stories Over Dinner at Aunt Byrrhena’s House

A few days later, Lucius received an invitation to dinner at his aunt Byrrhena’s house. When Lucius arrived for dinner, he noticed that a large, opulent party had assembled for the banquet. The subject of witchcraft came up fairly quickly, and Lucius’ aunt Byrrhena asked one of her guests, a man named Thelyphron, to tell a story. Thelyphron did so. The story, a peculiar one even in the context of Apuleius’ novel, was about how Thelyphron had once been hired to guard a corpse in Thessaly – a place, evidently, where corpses were often mutilated and had parts stolen from them by local witches. You know, guarding corpses from witches. Just like we do today.Thelyphron was warned by everyone that guarding a corpse was no laughing matter. Taking his job seriously, Thelyphron nonetheless ended up falling asleep, although the corpse was undisturbed when he awoke again, and he gratefully accepted his paycheck for guarding it. Later, Thelyphron went to the dead man’s funeral. And at this funeral, a magician caused the dead man to come back to life for a moment, and asked the dead young man a pressing question. The young man had been murdered, and the magician wanted to know the identity of his killer. It was, the young man said, his wife who had done the deed! And then the young murder victim revealed something else. Witches had come after him, he said, while he lay dead the night before. But they had instead attacked his guard Thelyphron, and had cut off Thelyphron’s nose and ears. Thelyphron said that ever since, he’d kept his disfigurement carefully concealed. With Thelyphron’s story complete, the assembled guests burst into laughter, enjoying what was evidently intended as a tall tale – Thelyphron, after all, bore no evidence of missing a nose or ears.

Lucius tells us no more about this party at Aunt Byrrhena’s house – only that on the way home, from his aunt’s house, on a dark and murky night, he was assaulted by three street toughs, whom he killed with his sword before going to bed back at his host’s house. You know how that goes – brigands assault you in an alleyway, and you slaughter them with your blade, and then go home and get some rest. Just like we do today. [music]

The Golden Ass, Book 3

Lucius Is on Trial for Murder

Lucius awoke, realizing that he’d been so exhausted the previous night that he’d gone to bed smeared with the blood of his combatants. Just as he realized he might be in legal peril for killing them, Lucius’ host’s house was swarmed with officers and magistrates, and Lucius was dragged away to a murder trial. Lucius’ prosecutor spoke of the savagery of Lucius’ crime. The evidence seemed damning, and yet when Lucius was given a chance to defend himself, he offered a stirring – and partly fictitious speech. Lucius said he’d caught the men on the verge of breaking into a house, and had only intervened due to a feeling that a dutiful citizen must do so. Lucius had, he told the assembly at the trial, acted with valor and a desire to protect his host. When Lucius’ speech was finished, though, those listening burst into laughter. And the trial magistrate announced that indeed the murders had been so dire that they had to have been the result of a more widespread conspiracy. Lucius, it was decided, would be tortured so that the names of his co-conspirators would be brought to light. Lucius, terrified, was then compelled to drag the sheet off of the three murder victims, so that everyone could see the blush of youth on the dead men’s skin. But when Lucius did so, he found three leather bags – each covered with sword wounds where he remembered stabbing. Lucius was completely flummoxed. The assembly teetered, and broke into laughter. It was, Lucius learned soon thereafter, all a joke – an annual ritual in which a foreigner would be hazed and all of Thessaly could have a good laugh.Lucius was then told that it was actually a great honor to be roasted by the whole city as he’d been. A statue of him would be erected and he’d be declared a city patron. Later that evening Lucius’ new lover, the slave girl Photis, said it had all been her idea. Photis’ mistress, the witch Pamphile, had accidentally animated three goatskin sacks – Lucius had stabbed them and Photis simply took advantage of the situation. Lucius said he’d forgive his lover – but only if she’d help him watch the witch Pamphile at work. Photis said it would be very difficult to arrange this, but that she would try. [music]

The Transformation of Lucius

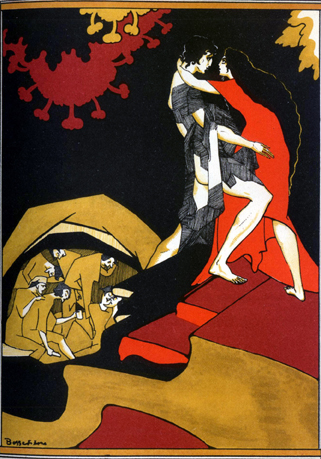

Jean de Bosschère’s 1947 illustration of Lucius spying Pamphile’s transformation into an owl (notice the feathers!).

It took some convincing, but soon Lucius gobbed the fluid all over himself. He flapped his arms once, expecting to burst outward with feathers. But instead, Lucius discovered, he had turned into a donkey. Photis apologized for the botched transformation, and said she’d bring him some herbs to help set him back to his human form in the morning. Specifically, Photis told Lucius, roses would restore him to human form – she just had to find some. And so Lucius plodded off to the stable, where he was first battered by his own horse, and thereafter by a young stable boy. Then things grew more dire – ruffians descended on the property. Lucius’ host Milo had so many valuables that Lucius and the other quadrupeds in the stable were loaded up with treasure to aid in the burglary. And soon thereafter, Lucius, transformed into an ass, was plodding away with the bandits, his future suddenly quite uncertain. This, by the way, ends the first portion of the novel, and begins the long series of frightening adventures that Lucius endures in the form of a donkey. [music]

The Golden Ass, Book 4

Lucius Falls in with Some Bandits

The company of bandits stopped at a farm to deposit some of their stolen treasures, and Lucius took the opportunity to devour a number of vegetables from the vegetable garden. Nearby he saw some roses – flowers which again would return him to human form. When he went to eat them, though, a youth tried to chase him off. Lucius kicked the young man, and soon the whole village set on him with dogs. The retaliating villagers might have ended Lucius’ life right there and then, but he vomited all over them.When evening came, Lucius the donkey was compelled to haul his treasures forth once more with the bandits. Another donkey collapsed in exhaustion and was killed by the bandits, prompting Lucius to shoulder his burden more resolutely. They made camp that night in the bandits’ den – a cave in a very rugged stretch of landscape – and Lucius was tied up near a gate. He observed the bandits greeting an old woman who’d stayed behind in their cave – a sort of den mother or custodian whom they treated none too kindly, and more bandits arrived, taking baths in the water the old woman had heated and devouring the food that she’d prepared.

A newly arrived group of bandits discussed a botched robbery that had occurred up in Thebes, prompting one of The Golden Ass’ many stories-within-stories – this one a picaresque about bandits scheming to rob people with varying degrees of success. First, the newly arrived group of bandits announced, they had tried to burglarize a solitary miser, but the man had proved much craftier than they expected. The bandits’ leader lost an arm in the escape, and later killed himself rather than live without his limb. Later, another bandit in their company, while in the process of robbing an old woman, fell from a roof onto a sharp rock and died. Following these disasters in Thebes, the bandits moved on.

In a town called Plataea, a man named Demochares was putting on a gladiatorial exhibition. This exhibition involved many bears, and the bandits got a hold of one of the bears, skinning it and making its skin into a disguise. Soon thereafter, a bandit wore the bear’s skin and was smuggled into the wealthy Demochares’ property. But once again for the bandits, thing went south, and guard dogs were set on the bandit disguised as a bear, and he died trying to escape. This was the end of the bandits’ story, and when it was finished, the bandits drank and ate dinner and Lucius munched on a piece of bread, disdaining the barley that had been set down for him. [music]

Lucius’ Co-Captive at the Bandit Camp

Lucius’ adventures in the cave of the bandits we not over yet. Some newly arrived burglars brought in a beautiful young woman with them – one which even as a donkey Lucius felt attracted to. The bandits told the young woman she was safe – they wouldn’t assault her, and merely were holding her for ransom, but still she wept at being in such a den of highwaymen and thieves. And then the kidnapped young woman shared her story.Prior to being kidnapped, the lovely young woman said, she’d been engaged to her cousin, a wonderful young man three years older than her. Just on the verge of being married, she’d been taken captive. And not long into her captivity, she’d had a dream – her beloved fiancé came after her, and one of the bandits killed him. The old den mother of the bandits said not to take the dream seriously. In order to prove her point, the old maidservant began her own story. This, by the way, is the story of Cupid and Psyche, the longest and most famous inset tale in The Golden Ass, which will go on through a couple of books, so we’re going to switch gears for a second and enjoy this novella-length tale. So clear your mind for a second and get ready for the long, inset tale of Cupid and Psyche. Here’s the story.

Cupid and Psyche: The Tale Begins

A king and a queen had three daughters. The older two daughters were good looking, but the youngest was extraordinarily beautiful – so beautiful that people would come from far away just to see her. The young princess was so lovely that she caused people to forsake the temples of Venus, as her adorers laid sacrifices to the princess rather than the goddess. Venus, of course, was not happy. She summoned her ne’er-do-well son Cupid to exact her revenge, telling Cupid to make the beautiful young princess fall in love with someone who was hideous and far below her station.Time passed, and the young princess was so beautiful that no one even tried to woo her. Her father began to suspect that she was cursed or blighted. He heard a prophecy that his daughter would unite with something grotesque – a vile serpent – and, following the words of his oracle, he decided his daughter would be sacrificed. The town prepared for the sacrifice, and the young woman herself was decked out in bridal attire. There was a general sense that something very wrong, and very wicked, was going on, but when the beautiful young princess’ parents delayed the sacrifice, she herself reproached them, telling them that her beauty had damned her and to get it over with. She was taken to a high crag of rock – perhaps to be abandoned to her death by exposure, but strangely, once she was left alone, and the wind bore her upward and carried her to a soft, green stretch of turf. [music]

The Golden Ass, Book 5

Cupid and Psyche: The Heroine Goes to a Strange House

This book picks up where the last one left off – the bandits have captured the main character Lucius, who has been turned into a donkey, and the bandit den mother is telling a story about a beautiful young princess, sacrificed by her parents but rescued by a mysterious wind. The young princess, whose name was Psyche, walked through a grassy meadow until she came upon an immense manor house. To give you an idea of Apuleius’ prose and sometimes extended set pieces, I’ll read you part of his description of this mansion – this is the Sarah Ruden translation, again published by Yale University Press in 2010.Psyche was lying comfortably on a stretch of delicate greenery, a veritable bed of dewy grass. With her immense agitation calmed, she fell gently asleep. But she was soon refreshed by an adequate dose of rest and got up again, peaceful within. She saw a grove planted with lofty trees, and a fountain with its glassy, pellucid fluid. In the heart of the grove, where the fountain rose, was a royal mansion, built with divine skill by superhuman hands. When you first entered it, you recognized this as the resplendent, delicious retreat of some god. The paneled ceiling was carved in intricate citron-wood and ivory relief and upheld by gold columns. All the walls were covered with embossed silver depicting wild and domestic beasts, who faced those entering the building. . . The very surface of the floor was subdivided and the pieces decorated with a contrasting array of pictures in precious stones. (92-3)

Being one of the world’s first few novels to survive in full, The Golden Ass shows attention to detail that would be a hallmark of prose fiction long afterward. Anyway, the beautiful, long-suffering princess Psyche found this exquisitely described manor house in the countryside, which seemed almost to be the abode of a deity. A disembodied voice told her that the house was hers, and invited her to take a bath and refresh herself. A lavish meal was mysteriously set before her, which she ate, and then she went to bed, feeling some apprehension that she’d be assaulted in the night. And indeed soon, someone did come in the darkness and stole away her virginity. He came the next night, and the night thereafter, until she yearned for his visits, though she never saw him.

Cupid and Psyche: The Heroine’s Sisters Become Jealous

Apuleius’ long inset tale of Cupid and Psyche is nearly as famous as the rest of the story of The Golden Ass, and has certainly inspired more works of art, like William-Adolphe Bouguereau’s The Abduction of Psyche (1895), shown here.

Now, Psyche’s two sisters, arriving back at home, were suddenly overcome with jealousy. They were the elders, after all, and they were surrogates in good old fashioned arranged marriages, and their little sister seemed to be in the middle of a real fairytale. Their husbands, after all, were old and ugly. The elder sisters talked, and talked, increasingly bitter – young Psyche had given them some baubles and then sent them packing. They decided to hide the news that their younger sister was still alive.

Meanwhile, in the magical palace, Psyche’s mysterious husband warned her that her sisters were turning against her. They would, he said, try to trick Psyche into ferreting out his identity. And – this was news to Psyche – Psyche was pregnant! If her sisters managed to discover the identity of her husband, Psyche’s baby would be mortal – otherwise, the baby would be divine. And the time of crisis was coming, said Psyche’s husband, because her sisters, now more fiercely jealous than ever, wanted to see her again. Psyche, assuring her husband that she was happy with things the way they were, said she still wanted to see her sisters.

The older two women arrived soon thereafter, now nothing less than villainous in their jealousy. The sisters spent an evening together that was pleasant on the surface, and Psyche, when asked, said that her husband was a rich merchant with a bit of silver in his hair. (She forgot, evidently, her earlier fabrication that he was a youth who liked hunting.) Her sisters noticed the conflicting stories and began speculating wildly – even wondering if Psyche hadn’t wound up married to a deity. Their jealousy came to a climax – they couldn’t possibly allow their younger sister to be the mother of a god! When the older sisters visited young Psyche a third time, they came with guns blazing. Who, the sisters asked, was her husband? An oracle, after all, had warned that she would be wed by a hideous monster – and perhaps Psyche’s husband was indeed a creature who would eat her and the baby once the baby was born.

Psyche, who is described as “a simple thing with an intellect like a tiny, delicate bud” (103), fell prey to her sisters’ strategy. She told them everything. She didn’t know, Psyche’s said, who her husband was – she’d never seen him in the light – indeed he might be just the monster that they warned of. And her sisters began to show the depths of their depravity. They told Psyche to sharpen a razor, and once her husband fell asleep, to slice his head off with it – thereafter, they’d carry Psyche off and she could be married to a human husband.

Cupid and Psyche: Venus Becomes Aware of her Son’s Transgression

And so that night, after her husband fell asleep, Psyche lit up a lamp, gripped her razor, and got a good look at her husband. He was. . .gorgeous as he lay there sleeping, his hair golden and curly, small wings on his shoulders, and she realized she’d married Cupid himself. She touched one of his arrows and, looking on the sleeping god, fell doubly in love with him. Just then, a drop of oil fell from the lamp onto Cupid’s shoulder. He awakened and, angry at being betrayed, he flew upward without a word. She tried to hang on to him, and eventually he addressed her. He had betrayed his mother Venus for her, he said. He’d been ordered to make her fall in love with something hideous but instead, he himself had fallen in love with her. But she’d betrayed him. He would abandon her. And for their vile plotting, Cupid continued, Psyche’s sisters would have to be punished. Psyche herself was swept off, drifted down a river, and, lost and lovelorn, decided to exact this revenge herself.Psyche went to one of her older sisters’ kingdoms, and she told this sister a partial truth. She’d married Cupid, she said – and Cupid had been so mad at having his identity uncovered that he said that he would marry one of Psyche’s sisters in order to punish her – the older sister just had to jump off of a crag and allow the wind to bear her to his kingdom. The older sister leapt from the crag, expecting a divine wind to spirit her to her godly husband. Instead, she plummeted to her death, and her corpse was devoured by wild animals. Psyche repeated the process with her other older sister.

Meanwhile, Venus had caught wind of odd things going on with her youthful son – namely, that he had a lover. Cupid, singed by the oil from Psyche’s lamp, was convalescent in the home of his mother, and Venus began to try to root out who had been sleeping with her cherished boy. A sea bird told Venus he had heard that it was Psyche. Venus, who had been jealous of Psyche’s beauty to begin with, became very, very angry – especially since her son had betrayed her for the sake of the lovely mortal girl. And as we’ve learned from the entire Epic Cycle and beyond, from the Apple of Discord in the lost Cypria all the way to the Aeneid, when Venus gets angry, anguish and death loom on the horizon. Venus rushed to where young Cupid was recuperating. She insulted her son elaborately, angry that he’d been such a difficult baby, that he’d chosen the backward Psyche as a mate, that he’d made her pregnant – and Venus said she would use Psyche to humiliate Cupid, storming out the door.

Once outside, though, Venus encountered Ceres and Juno – the Roman versions of Demeter and Hera, and the other two goddesses told Venus to settle down. Cupid was a young male deity – it only made sense that he’d go after a beautiful young woman. It was all love, after all, said Ceres and Juno, and Venus was the goddess of love. Venus, however, interrupted them and stormed off, bent on pursuing her revenge. [music]

The Golden Ass, Book 6

Cupid and Psyche: Venus Pursues and Sets Trials for Psyche

While the union between Cupid and Psyche has attracted many artistic depictions, Psyche’s subsequent struggles with the furious Venus also make up a long portion of the narrative. The painting is Edward Matthew Hale’s Psyche at the Throne of Venus (1883).

Meanwhile Venus went to Jupiter and asked for his help, borrowing the deity Mercury. Mercury was enlisted to distribute fliers with reward notifications – the reward – we learn, would be seven kisses from Venus herself – one of which included tongue. The whole scheme of putting out the pamphlets, however, proved unnecessary, because Psyche turned herself in. And Venus, finding the young woman under her control, did not prove very mild or forgiving. Psyche was tortured. Venus railed over the fact that she would be a grandmother if Psyche indeed carried her baby to term. It wouldn’t be an issue, though, said Venus – there had been no real wedding and so the baby was illegitimate. Venus beat Psyche severely, tearing out her hair and smashing her head. Then Psyche was ordered to sort a huge pile of seven different kinds of beans and seeds before nightfall. Venus stormed off and Psyche, grievously injured and barely alive, stared at the heap of beans and seeds, unable to even think.

At that moment, an ant saw poor Psyche and took pity on her. There was no way the battered girl could accomplish the task set for her. But ants, however, could. The ant summoned an army of his comrades, all of whom found Psyche’s story tragic, and the little arthropods threw themselves into the task of sorting the pile, so that by nightfall, it was flawlessly sorted. Venus, in the evening, returned, drunk from a banquet and she expressed doubt that Psyche had been the one to sort the seeds, saying that Cupid must have helped somehow. She gave Psyche a bread ration and retired for the evening.

The next day Venus had another punishing task for Psyche to perform – Psyche was to go into a dense forest and retrieve fleece from some ferocious rams. When she was released to begin her search, Psyche first planned to simply drown herself in a river and end her sorrows. She didn’t want to have anything to do with angry rams in a dark forest. But the river gave her a tip. Just wait, the river said, until the late afternoon, hang out by a specific tree, and collect fleece off of some of the low hanging branches. Psyche did so, and when she brought Venus an armful of fresh fleece, the angry goddess said that Cupid must have helped her with this, too. Venus gave her another dreadful task – water welled up from the top of a perilously high and steep crag of rock – Psyche was to climb to the very summit and gather some water there and bring it back down to Venus. And so Psyche went to the foot of this tower of rock. And as Apuleius writes, in the Oxford P.G. Walsh translation,

A rock of huge size towered above her, hard to negotiate and treacherous because of its rugged surface. From its stony jaws it belched forth repulsive waters which issued directly from a vertical cleft. The stream then glided downward, and being concealed in the course of the narrow channel which it had carved out, it made its hidden way into a neighboring valley. From the hollow rocks on the right and left fierce snakes crept out, extending their long necks, their eyes unblinkingly watchful and maintaining [an] unceasing vigil.8

Psyche stood there, looking upwards, and her hope of survival left her once more. However, again unexpected aid came to her. An eagle, who told her that even the gods feared the dire waters she’d been directed to collect, offered his help, returning soon thereafter with the little vial full of the mountain waters.

When Psyche unexpectedly completed this third impossible task, Venus was undaunted. She said Psyche must be a witch – and added that Psyche’s trials stillweren’t over. Psyche was to take a box, go to the underworld, and meet with Persephone herself, requesting some of the goddess of the underworld’s loveliness. Venus departed, and Psyche realized that this was it – she was actually just being told to die. Psyche climbed a tower in preparation to take her own life. But the tower told her to do differently. She didn’t have to die, the tower said. There was an entrance to the underworld in Sparta – Psyche just needed to bring a cake in each hand and carry two coins in her mouth. In general, it’s always a good idea to bring a couple of cakes when you go to a dangerous place – perilous situations can often be resolved by frosting and sprinkles. The tower gave Psyche the following advice – give a coin to the ferryman Charon on the way into the underworld, give a cake to the three-headed dog Cerberus, act modestly before Persephone even if Persephone offered lavish gifts, get the treasure from her, and then on the way out give Cerberus and Charon the remaining cake and coin, respectively. Psyche did exactly as the tower had advised, but for one change. Psyche became curious about the treasure that she’d been sent to retrieve from Persephone – a morsel of the goddess’ borrowed beauty. Psyche opened up the box, intending to give herself a little dollop of the beauty, but the little box was instead just filled with the essence of sleep, and Psyche dropped into a deep slumber.

Meanwhile, Cupid had finally recovered from his wound. It was only a little dribble of oil from an ordinary lamp, but Cupid was, we can gather, not the most robust of deities. Anyway, Cupid was feeling better. He flew to where Psyche lay sleeping and awakened her, lovingly admonished her for her curiosity, and told her to complete her errand. And while Psyche did this, Cupid hurried to Jupiter. He threw himself at Jupiter’s feet, asking Jupiter to petition Venus for him, and Jupiter, after grumbling a bit, agreed to do so. Thereafter Jupiter convened a meeting of the gods – a sort of senatorial gathering in which Jupiter first admitted that Cupid was far from perfect, but then added that Cupid had found a woman he loved, and deserved to be married to her.

Jupiter then brought Psyche up to heaven and had her drink a cup of ambrosia so that she would become divine – that way Venus wouldn’t feel slighted that her son had married a mortal. Thereafter the gods pulled out all the stops to put on an extravagant divine wedding. And after a time, Psyche gave birth to a daughter – the goddess Pleasure. [music]

The Main Story of The Golden Ass Resumes

And that concluded the story that the old bandit den mother told to the kidnapped and ransomed girl to cheer her up – a sprawling narrative nearly 50 pages in length that stretches through multiple books of Apuleius’ The Golden Ass. Immediately thereafter, poor Lucius, still in the form of a donkey, was dragged out of the cave and forced to carry treasures elsewhere, one of his legs and hooves injured. The bandits resolved to hurl him off of a cliff once he had finished his journey with them. And when they were all off, in a desperate bid to survive, Lucius the donkey booted the old den mother with one of his hooves. A moment later, unexpectedly mounted by the beautiful ransomed girl, who also wanted to escape the bandits, Lucius galloped off toward freedom. The girl was exultant, telling Lucius the donkey that he would be immortalized for helping abet her escape, but when they came to a fork in the road she demanded that he go in the wrong direction, leading the two of them headlong into the bandits, who were at that moment returning.Things quickly became grim back at the bandit camp. The bandits discussed various ways the escaped girl would be maimed and killed. They were mad at the donkey, too. And eventually they came up with an elaborately brutal punishment – the donkey would have his innards cut out, the girl would be sewn up inside of him, and they would both be tied up to perish in the sun. It would all take place the following day. [music]

The Golden Ass, Book 7

Lucius and the Girl Escape from the Bandits

The next morning, a bandit newly arrived from Thessaly showed up at the camp. He had, he said, pillaged the home of Milo, where Lucius had been staying, and everyone blamed the robbery on this Lucius! (Lucius himself, present in the form of a donkey, cringed inwardly at this new morsel of terrible news.)At that moment, another a new bandit arrived – a brawny young tower of a man named Haemus. He said he was indeed dressed in rags, but had once led a powerful band of robbers, and his story impressed the bandits so much that they at once elected him their leader. They had a feast to celebrate, at which the new leader Haemus learned of the nasty execution of Lucius the ass and the girl who’d tried to ride him to safety the previous day. Haemus said it was a waste – she could be sold to a brothel for good profit, and serving as a prostitute would be punishment enough. The other bandits agreed, and a moment later, the girl was informed of the grim fate that lay ahead. She reacted. . .unexpectedly at the news that she’d be sold into prostitution. She seemed overjoyed, and Lucius and the bandits realized that the girl that had been kidnapped had hardly been the virginal princess she’d pretended to.

Jean de Bosschère’s Charite Embraces Her Lover (1947). Lucius realizes that the beautiful young woman the bandits have captured is more than a damsel in distress in this memorable scene in the novel.

Lucius the donkey had some time to recuperate, gorging on all of the foods livestock loved the most, until the pasture overseer was directed to let him free. But rather than freeing Lucius the donkey, the pasture overseer took Lucius to his own farm, where Lucius was yoked and compelled to work. In the evenings, he was pastured with horses and bullied by stallions. Later, Lucius was forced to haul wood down a mountain by an especially harsh and pitiless young man who whipped him through the duration of his workday. This young man was actually sadistic, whipping Lucius raw, sitting on him during precipitous sections of the trail, clubbing him, and tying his tail with a rope of thorns. The boy tried to set Lucius on fire, and Lucius dashed into a muddy pool, but the boy then blamed Lucius’ burns on Lucius himself.

Then the boy did something just as wicked. He lied and said that Lucius the ass tried to have sex with every attractive human being he saw, and his audience discussed chopping Lucius into pieces and feeding his innards to the dogs and eating him. Another man suggested an alternative – Lucius could simply be neutered. This man said he’d be happy to perform the operation the in the next few days.

Hearing all of this Lucius the donkey was distraught. He was taken up to cut wood with the sadistic boy, who tied him to an oak tree. But a bear emerged from a cave, startling Lucius so much that he tore his tether from the tree and tumbled down the mountainside. A shepherd found him and led him off, but Lucius and the shepherd quickly fell on ill luck. Men from the farm where Lucius had been working discovered them, put Lucius back into captivity, and the shepherd was blamed for the death of the wood hauling boy, who had been torn to pieces by the bear. Lucius was again in imminent peril – he was not only to be neutered the next day, but the wood hauling boy’s mother tortured him in his stable stall until he defecated all over her. [music]

The Golden Ass, Book 8

The Bad Fate of Charite and Tlepolemus

On the verge of being neutered, Lucius the donkey had the opportunity to hear a story about someone he’d met earlier in the novel. This someone was called Charite – she had been the kidnapped woman he’d met at the bandit camp – the one who’d been freed. Charite had indeed married her valiant suitor Tlepolemus, who’d rescued her from the bandits. But wicked crimes ensued – because another man loved Charite, as well. His name was Thrasyllus, and during a boar hunt, he murdered Tlepolemus and made it look as though the boar had done so.Thereafter Charite mourned extensively. And Thrasyllus hardly hesitated to press his suit to the grieving widow. She was disgusted. Then she was angry. And then, after the ghost of her dead husband Tlepolemus came to her and told her the truth, Charite began to plan her revenge. She told the wicked Thrasyllus that she would indeed marry him – only he would have to wait a year’s time. Meanwhile, though, said Charite, if he wanted to have sex with her, it would have to be done in secret. The news of Charite’s willingness drove Thrasyllus into distraction. This was what he had wanted all along. She told him to come to her house in secret, to meet her nurse, and to be ushered into her bedroom in the dark – there would be no lamplight to illuminate their illicit encounter. And Thrasyllus agreed.

When he arrived, he was given drugged wine, and soon thereafter passed out. Charite, after a long speech, gouged his eyes out with a hairpin and then removed them. Thereafter she ran through the city, her husband’s sword in hand, and, standing at the tomb of her dead husband, stabbed herself to death. The malevolent Thrasyllus killed himself soon thereafter.

Lucius’ Continuing Adventures; The Followers of Sabadius

Now, this story actually had a direct bearing on Lucius himself – after all he was a donkey in the herds of Charite and her dead husband, and so the herdsmen employed by this unfortunate couple decided it was time to light out and make a living elsewhere, since their employers were dead. Lucius, therefore, once again escaped a dire fate – rather than being neutered, he was freighted with household goods and he began a journey elsewhere. But Lucius, as usual, was not rescued from peril – the journey with the recently unemployed herdsmen immediately proved to be dangerous. The route that they were taking, they soon learned, was often plagued by wolves. Though the traveling party ignored local counsel to do otherwise and traveled at night, no wolves attacked them. Instead, the band of herdsman and animals, when they passed an estate some time later, were mistaken as brigands. The heads of a local estate set a pack of dogs on them, and Lucius and his traveling party were in grave danger until they managed to explain that they were just traveling herdsman with their families.Later, the farmers and herdsmen were washing their wounds in a creek after the skirmish. An old man saw them taking a break, hobbled down to their camp, and asked for help. His grandson, he said, had fallen into a pit of brambles and needed to be rescued. Couldn’t they help? One healthy young herdsman sped off to help the unfortunate old grandfather. But later, Lucius’ party found that it had been at trap – the young herdsman who had volunteered to help was discovered partially eaten, a dragon perched on him, chewing his flesh. Rather than investigating or seeking vengeance, Lucius the donkey and the herdsman he now traveled with fled, arriving safely that night at a village.

Recently, at this village, a slave had been executed in a gruesome manner – by being covered with honey and then eaten alive by ants. Learning this, Lucius and his party moved on. Soon they came to a good sized town, and auctioned off their livestock. No one wanted to buy Lucius, and he was given away for a very small sum to a religious zealot named Philebus. Philebus, whom Apuleius depicts as a decadent homosexual, was the head of a band who worshipped an eastern deity called Sabadius. A procession soon began, the worshippers of Sabadius playing music loudly and then some engaging in self mutilation as Lucius the ass bore the deity’s effigy in the parade. As the afternoon lengthened, the homosexual acolytes of Sabadius swindled people out of money and had an orgy with a well-endowed peasant man.

Lucius, overwhelmed by the sight, brayed loudly, causing some locals to burst in on the scene of the all-male religious orgy. The troupe who worshipped the goddess Sabadius, which had perhaps never been particularly revered, was now exposed as a mob of swindling hedonists. The acolytes of Sabadius abandoned the village and punished Lucius severely. And soon yet another peril threatened him – one which Lucius in hindsight calls “the greatest peril of my life” (183). What happened was that a hunter had killed a stag and the stag’s leg had been cooked. The stag’s leg, however, had been stolen by a dog, and the hunter didn’t know it yet. It was proposed that Lucius the donkey’s leg be used as a substitute. The hunter would never know the difference. [music]

The Golden Ass, Book 9

Lucius Falls in with the Baker and His Wife

Lucius’ adventures grow increasingly harrowing and degrading as the novel progresses, as this eighteenth century French manuscript illustrates.

The next day, Lucius and the roving priests lodged at a city that had fallen on hard times. And there, Lucius heard a brief story about the lusty wife of a poor man – a story that could have come from Chaucer or Boccaccio. Anyway, the priests of the goddess Sabadius set up camp there in the new town and began swindling people out of their money. But it wasn’t long before they were arrested and led off to jail, and Lucius the donkey was put up in an auction and sold to a baker. Lucius’ new job, it seemed, was to be yoked to a grinding wheel. After his first day at work, Lucius took a good long look around at the slaves and livestock who were part of the mill’s operations, all in awfully poor conditions.

It was a tragic sight – the emaciated men and animals, their bodies showing signs of chronic abuse and fatigue. In the midst of looking around the slave quarters, Lucius had the strange thought that at least his time as a donkey had brought him a wide range of experience – he reflected that “I [could] now even feel a gracious gratitude toward my past as an ass because while [in] his form . . . I could be drilled in many different contingencies and rendered well rounded, if not wise” (194).

While enslaved at the mill Lucius the donkey discovered that the baker’s wife was not only an alcoholic and a brutal person, but also an adulteress. Lucius tells us that while being a donkey was generally awful, he did enjoy terrific hearing, which helped him stay apprised of what people were trying to hide from one another. And he heard a story from the lips of the baker’s wife’s old nurse – one of The Golden Ass’ dozens of inset tales. In this story, a jealous husband left a slave to watch over his wife’s chastity when he went off on a journey. Of course, any jealous husband in any story from 0-1,500 AD is going to get cuckolded. The man’s wife had a lover, the lover paid the slave some gold, and the tryst was arranged and took place. The husband came home early, none the wiser, and the lover escaped, but for leaving his shoes behind. And when the husband discovered the lover’s shoes, he went to the town square with his disloyal slave to look for their owner. The lover, however, berated the slave for stealing his shoes at the baths, and the husband believed the story, and so the slave, wife, and lover all escaped from the affair unscathed, as the husband felt so relieved that he forgave what he believed to be only his slave’s petty theft.

Now, this was the story Lucius heard the baker’s wife hearing from her old maid, and soon the baker’s wife embarked on her own extramarital adventure while her husband was away visiting a friend. The baker’s wife dined with her lover. Her husband returned home early. She hid her lover under a storage container. And following two stories about extramarital affairs, and in the midst of another story of an extramarital affair, Apuleius folds in a fourth story about an adulterous wife – this one told by the baker himself, as his own wife is standing there with her lover from him. In the baker’s story, the baker’s friend’s wife and his lover were having sex. They were interrupted and she hid him in a smoky cage. He coughed, and was discovered, and the affair brought to light.

As Lucius the ass heard the baker telling his wife this story, he would have been conscious of the irony that Apuleius surely intends, because the baker’s wife is, at this exact moment, hiding her lover from the baker beneath a trough. The baker’s wife condemned the adulterous woman, and at the same time urged her husband to go to bed so that she could get her own lover out of his hiding place. Lucius was disgusted, and soon he had the opportunity for revenge. He was brought to the trough to drink, he saw the lover’s fingers protruding from a gap, and stomped on them, breaking them all. The baker’s wife’s lover was outed, but the baker didn’t exactly exhibit the response Lucius had anticipated. The baker promised clemency to the handsome young lover, along with – and you’re hearing this correctly – a threesome with his wife. Before the threesome, however, the baker first had sex with the young man, then had him whipped the next morning, and, I gather, changing his mind for whatever reason, divorced his wife.

Anyway, the baker’s wife wasn’t happy about having her sexy beefcake boyfriend stolen and then getting dumped. She went to a witch for help. And soon thereafter, having had frightful visions, the baker hung himself. Let me pause the story for a second and comment that Lucius the donkey fell into company with some very – uh – memorable individuals. [music]

Lucius Changes Hands Again

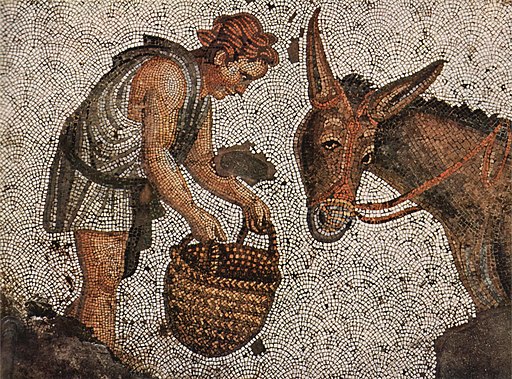

A 5th century Byzantine mosaic from Istanbul showing Lucius being fed. Though the protagonist encounters occasional instances of kindness and comfort, in the main his journey through the ancient world is harrowing and difficult.

The traveler staying with them for the night was a local landowner with three sons. The omens, as it turned out, were of the deaths of his sons – his sons had perished fighting a small war against a pernicious local landowner who was working to squeeze everyone out of their property, and hearing this, the landowner dining with Lucius’ master cut his own throat.

After this bloody incident, the poor farmer who owned Lucius the donkey was riding Lucius to town when a legionary suddenly confronted them, announcing that he needed to confiscate the donkey to do army work. The moneyless farmer protested, was assaulted, and eventually fought back so fiercely that the legionary was nearly knocked unconscious. Thereafter the poor farmer hid, and the legionary went back to his camp and gathered up some fellow soldiers. And it wasn’t long before they were found and Lucius changed hands once again, becoming the property of the legionary. [music]

The Golden Ass, Book 10

The Journey to Corinth and the Worst of Lucius’ Debasements

And so Lucius was led off bearing the luggage of a soldier. While owned by this soldier Lucius heard a sensational tale about a wicked stepmother who lusted after her stepson. Finding him resistant, the stepmother decided to poison him instead. Only, accidentally, she poisoned her own biological son whom she’d brought to the marriage. Displaying neither grief nor compunction, she blamed the poisoning on her stepson. And as in the tale of Phaedra and Hippolytus, Anteia and Bellerophon, and Joseph and Potiphar’s wife, the lusty stepmother in Apuleius’ story falsely said her stepson had pursued her.

This mashup illustration shows the final incidents in Lucius’ adventures as a donkey, including, finally, his galloping down to the seashore near Corinth.

Having offered us this version of the familiar tale, Apuleius returns us to the story of Lucius the donkey, now the property of a legionary. Never one to tell the same story for more than four seconds, Apuleius changes the scene again – Lucius the donkey was given to some slaves, whose food he filched, day after day. The slaves and their master wondered where all the human food was going until they caught him in the act. Rather than punishing him, they found the sight of the donkey eating human food to be hilarious. Lucius was brought forth at a banquet to eat all sorts of meaty delicacies, to the delight of an assembled crowd. He was purchased by a new master, who staged him at banquets for show.

Lucius was taken back to Corinth, where his anthropomorphic antics made him a local celebrity. And in one of The Golden Ass’ more memorable episodes, a Corinthian woman became infatuated with Lucius the donkey, and he was hired as a sort of animal prostitute. Apuleius writes a lengthy and very detailed sex scene from the perspective of Lucius the donkey about how the interspecial fornication went down – I guess I can just say that it was thorough, and mutually enjoyed. Whether we’re in Apuleius, Juvenal, or the Bible, ancient writers seemed to have a thing for woman-on-donkey sex scenes. Anyway, finding that his peculiar donkey indeed enjoyed sex with willing human women, Lucius’ new owner decided to stage a sex show.

Unfortunately for modern sensibilities – or perhaps any human sensibilities, period, the woman sent to Lucius to be part of the newly opening donkey-human sex show was sent to him as punishment for her misdeeds. The woman was, as we learn, a pretty awful person. Jealous of her husband, and under the mistaken supposition that he was having sex with his own sister, the convicted woman had killed her sister-in-law by shoving a burning torch up the other woman’s vagina. The convicted woman had also poisoned her husband, and poisoned the doctor who’d sold her the poison. Then the convicted woman killed the doctor’s wife, and then her own daughter. The doctor’s wife, however, managed to alert a governor as to what was going on, and this was how the woman was convicted and sent to Lucius the donkey to receive her public sexual punishment.

As for Lucius, he didn’t want anything to do with such an awful person. In general, when people are being sent to have sex with you as a form of public punishment, I don’t think it’s very good for your ego, and with Lucius it was hardly any different. Games and festivities were set up. Apuleius describes, with enthusiastic detail, the nude youths dressed as deities who peopled a stage during a pastoral procession with music and dancing, at the center of which were Venus and the Trojan hero Paris. Other pantomimes followed this, and soon a couch was brought out, on which Lucius realized he was intended to have sex with the convicted woman. As preparations were made for the sex show, Lucius felt terrified, disgusted, and ashamed. He couldn’t do it. This was too much. He snuck off – everyone thought he was just a tame ass – and he galloped off six miles to the seashore near Corinth. [music]

The Golden Ass, Book 11

Lucius Prays for Deliverance and the Prayers are Answered

The climax and resolution of The Golden Ass, in a 1787 French printing, shows Lucius transformation and the beginning of his new life as a devotee of the goddess Isis.

Almost immediately, though, a deity came him out of the seawater. And Apuleius here offers us one of the longer descriptions of the Egyptian goddess Isis to survive from antiquity. This is the S. Gaselee translation, first published by Loeb in 1915 – again the Egyptian goddess Isis, one of the most popular deities in the Roman Empire, who takes center stage toward the end of Apuleius’ novel.

First [Isis] had a great abundance of hair, flowing and curling, dispersed and scattered about her divine neck; on the crown of her head she bare many garlands interlaced with flowers, and in the middle of her forehead was a plain circlet in fashion of a mirror, or rather resembling the moon by the light that it gave forth; and this was borne up on either side by serpents that seemed to rise from the furrows of the earth, and above it were blades of corn set out. Her vestment was of finest linen yielding divers colours, somewhere white and shining, somewhere yellow like the crocus flower, somewhere rosy red, somewhere flaming; and (which troubled my sight and spirit sore) her cloak was utterly dark and obscure covered with shining black, and being wrapped round her. . .under her left arm to her right shoulder in manner of a shield, part of it fell down, pleated in most subtle fashion, to the skirts of her garment so that the welts appeared comely. Here and there upon the edge thereof and throughout its surface the stars glimpsed, and in the middle of them was placed the moon in mid-month, which shone like a flame of fire; and round about the whole length of the border of that goodly robe was a crowd or garland wreathing unbroken, made with all flowers and all fruits. Things quite diverse did she bear: for in her right hand she had a timbrel of brass, a flat piece of metal curved in manner of a girdle, wherein passed not many rods through the periphery of it; and when with her arm she moved these triple chords, they gave forth a shrill and clear sound. In her left hand she bare a cup of gold like unto a boat, upon the handle whereof, in the upper part which is best seen, an asp lifted up his head with a wide-swelling throat. Her odoriferous feet were covered with shoes interlaced and wrought with victorious palm.9

The goddess Isis greeted Lucius, calling herself, in the Ruden translation, “the mother of the universe, queen of all the elements, the original off-spring of eternity, loftiest of the gods, queen of the shades, foremost of the heavenly beings, single form of gods and goddesses alike” (250). The goddess said that although she was variously called Venus, Diana, Ceres, Juno, Hecate, and other names, only the Egyptians called her by her correct name – Isis.

Isis gave Lucius instructions on how to return to his human form, and promised him that for his sufferings, he would be blessed by her personally. And, Isis added, “if with compliant diligence and pious observance and determined chastity you conciliate my holy will, know that I, and I alone, am permitted to grant you a term of life beyond what your fate decrees” (252). Hearing this, Lucius fell asleep once again.

The Beginning of Lucius’ Life in the Isiac Cult

When he awoke the next morning, it was warm and sunny, as though the day itself were rejoicing. Birds sang and leaves bloomed as Lucius made his way toward an ornate procession of performers and actors. A hodgepodge of priests came forward, bearing the talismans and effigies of various religions. And Lucius saw what Isis had told him to look for – a priest, bearing a garland of roses. He went up and ate one of them and finally, following month after month of silent suffering, changed back into a human being. The crowd was astonished – the priest gave Lucius a garment to wear, and then addressed him by name. He said, following the knowledge that had come to him in a dream, that Lucius’ sufferings had been considerable, but that if he joined the worshippers of Isis, he would know peace and be safe.Lucius didn’t hesitate. He joined the parade. Later, he purchased a house on the temple grounds of Isis. Lucius’ relatives, and many other people, heard his astonishing story. But while his fame spread, Lucius wanted only to worship Isis – to undertake her sacred mystery rites, and keep himself as clean and pure as her most chaste priests. The day his consecration was to begin arrived. He had a sacred bath. He began a strict dietary regimen. Apuleius records Lucius’ ecstatic conversion speech in its entirety, which ended with the resolution, “I will take care to do the only thing in the power of a man assuredly reverent yet poor. I shall picture to myself and guard forever within my heart’s inmost shrine your divine countenance and your most holy godhead” (268).

Following his cult initiation, Lucius travelled to Rome, and prepared for the associated initiation rites of the god Osiris. While Lucius’ resources were wearing thin, he stuck it out and soon attended the mystery rites of Osiris, as well. Soon, Osiris appeared to Lucius in his sleep and urged Lucius to take up the practice of law, being open about his religious persuasions. Lucius did so, and, for the rest of his days, never shied away from being open about his adherence to the Isis cult. And that’s the end. [music]

The Renaissance Revival of The Golden Ass

So that was the story of The Golden Ass, an ancient Latin novel, likely written around the 160s CE. Long after the end of antiquity, The Golden Ass was first printed in Italy in 1469, and began to show up all over Europe within the next 100 years, being translated into English and printed in London in 1566, when Edmund Spenser was 14, Philip Sidney 12, and William Shakespeare and Christopher Marlowe both just two. Reproduced in the vernacular languages of Europe as the Renaissance reached its full flowering, features of The Golden Ass begin emerge everywhere starting in the fifteenth century – the paintings of Caravaggio, Rubens, Titian, and Velasquez, in Spenser’s Faerie Queene, Shakespeare’s Midsummer Night’s Dream, Marlowe’s Hero and Leander, and later Milton’s Comus. Like other works of Latin literature we’ve encountered that re-emerged into European history during the renaissance, The Golden Ass offered stories and imagery a far cry away from Christianity’s scriptures and martyr tales – a window into a spellbinding lost world of Roman culture at its apex for several generations of European readers.From the beginning, when Christianized Europe revitalized Apuleius, it was critical to some that the second century Latin author was recognized as a man with beliefs broadly consonant with the teachings of the New Testament. For William Adlington, the writer who published the first, and perhaps still most influential English translation of The Golden Ass in 1566, reading a generally Christian morality into Apuleius’ story was a serious concern. Shakespeare, Marlowe, and others, might have read Adlington’s note to his readers in the translation that Adlington published, which announced,

I intend, God willing, as nigh as I can to utter and open the meaning [of this book] to the simple and ignorant, whereby they may not take the [book] as a thing only to jest and laugh at. . .but by the pleasantness thereof be rather induced to the knowledge of their present. . .state, and thereby transform themselves into the right and perfect shape of men. . .Verily under the wrap of [Lucius’] transformation is taxed the life of mortal men, when as we suffer our minds so to be drowned in the sensual lusts of the flesh and the beastly pleasure thereof. . .that we lose wholly the use of reason and virtue, which properly should be in a man, and play the parts of brute and savage beasts. . .But as Lucius. . .was changed into his human shape by a rose. . .so can we never be restored to the right figure of ourselves, except we taste and eat the sweet rose of reason and virtue, which the rather by mediation of prayer we may assuredly attain.10

To Adlington, then, The Golden Ass is not just a bundle of amusing episodes – it is a story that promotes the pursuit of reason and virtue as the only real alternative to the otherwise benighted and debased sensualism of the human condition.