Episode 74: Marcus Aurelius

Marcus Aurelius’ Meditations shows an intelligent emperor coping with the realities of an empire buckling under its own weight.

“”| Read Transcription | References and Notes |

| Episode Quiz | |

| Episode on Spotify | Episode on Apple Podcasts |

| Previous Show | Next Show |

The Life and Work of Marcus Aurelius

Hello, and welcome to Literature and History. Episode 74: Marcus Aurelius. This program is on the Meditations of Marcus Aurelius, a short work of ethical philosophy written during Marcus’ years as the Emperor of Rome, between 161 and 180 CE. While we will cover the Meditations in some degree of detail, breaking this fragmentary book into some different thematic categories, and discussing them separately, we’ll also talk about Marcus himself – his family history, his intellectual background, his work as emperor, and the wars that he found himself compelled to fight.Perhaps the first thing we should say about Marcus Aurelius is that at the moment, he happens to be very popular. As I record this, a number of the top thirty bestselling philosophy books on Amazon are print and audio versions of the Meditations, and stoicism has outstripped many of its rivals in ethical philosophy to emerge in the twenty-first century, to the bemusement and no doubt joy of classics professors, as a something of a mania. Its core tenets – the notion that one always has power over the private world of one’s ethical choices, that one ought to work for the betterment of humanity in general, that a single force controls the universe, and that the pursuit of virtue, reason and self discipline over hedonism and self indulgence should be the main goals of life – are things that we’ve discussed in previous episodes on Seneca and others. For its broad compatibility with Abrahamic religions and its generally uncontroversial stances on self conduct, stoicism is a sort of shredded wheat breakfast cereal of ethical philosophies, endorsing, as so many ethical philosophies do, moderation, self awareness, confidence in the sovereign order of the universe, and the power of human reason, perhaps bland sometimes, at others soggy and gloomy, but always dependable for a spoonful of healthy, reasonable advice.

Marcus Aurelius within the History of Stoicism

As Marcus Aurelius was an emperor respected by history, many busts of him survive, having the characteristic melancholy intelligence shown in this one.

If Seneca, then, is stoic philosophy’s homely black sheep, Marcus Aurelius, born a hundred and twenty years later, is its white knight. Exposed to every temptation Rome had to offer, not the least of which was simply aristocratic laziness, Marcus worked himself hard, spread himself thin, and though the Meditations sometimes shudder with pessimism, genuinely seemed driven to spend the time given to him in the service of others. The historian Edward Gibbon wrote that the dynasty that Marcus Aurelius capped off was “the period in the history of the world during which the condition of the human race was most happy and prosperous.”1 While this famous hyperbole is, in hindsight, absurd, we have enough information to say that the happiness and prosperity of the Roman Empire under Marcus Aurelius was due, in no small part, to the intelligence, political acumen, and solemn dedication to duty of the emperor himself. While Marcus Aurelius is often criticized for a stodgy dedication to the interests of the senate, and much more seriously for bequeathing the empire onto his son Commodus without offering Commodus the education Marcus himself enjoyed, even Marcus’ harsher critics admit that the last of the Five Good Emperors did a decent and honorable job keeping an empire together amidst two major invasions, an attempted coup, and the worst epidemic Rome had ever faced up to that point in history.2 During his exhausting and apprehensive years on the throne, the emperor turned again and again toward philosophy for respite.

Stoicism, under the pen of Marcus Aurelius, is a philosophy of self control and quiet dignity amidst the temptations and fluctuations of life. As the poet Matthew Arnold wrote,

It is impossible to rise from reading. . .Marcus Aurelius without a sense of constraint and melancholy, without feeling that the burden laid upon man is well-nigh greater than he can bear. . .The sentences of Seneca are stimulating to the intellect. . .the sentences of Marcus Aurelius find their way to the soul. I have said that religious emotion has the power to light up morality: the emotion of Marcus Aurelius does not quite light up his morality, but it suffuses it; it has not power to melt the clouds of effort and austerity quite away, but it shines through them and glorifies them; it is a spirit, not so much of gladness and elation, as of gentleness and sweetness; a delicate and tender sentiment, which is less than joy and more than resignation.3

While the Meditations is no doubt a beautiful book, in comparing Marcus Aurelius with Seneca we need to give the earlier philosopher his due. Seneca, quite simply, not having the duties of an emperor, produced a great deal more work. Marcus’ Meditations, while again hardly an objectionable piece of work, is little more than a brief, fragmentary self help manual, whereas Seneca wrote full-fledged studies on ethics, metaphysics, natural science, and political history. The earlier philosopher, however compromised his reputation was from the beginning, ultimately made far more technical contributions stoic philosophy; the latter, whose life demanded more action than contemplation, left behind a single book, and its brevity and simplicity make it more suited to modern tastes than most of Seneca’s works.

Marcus Aurelius’ Meditations, then, offers us stoicism light – a handbook of stoic ethics mostly uncluttered by metaphysics, epistemology, aesthetics, and other branches of philosophy perennially less popular with the general public. In a grand total of 488 short paragraphs and mini-essays, made up of imperative sentences addressed from the emperor to the emperor, Marcus Aurelius outlines how one ought to live and cope with the privations and disappointments of life, something which, as one of Rome’s unluckiest emperors, he knew plenty about.

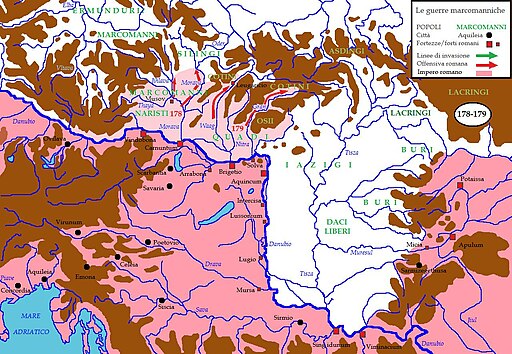

The Marcomannic Wars were all-consuming for Marcus during long periods of his time on the throne, an evolving series of conflicts northeast of the Adriatic that the emperor had to take breaks from in order to deal with other calamities. Map by Cristiano64.

But reading the Meditations alongside modern biographies of Marcus Aurelius, we get a sense of where his worldview came from, and a richer and more human picture of the emperor emerges. Naturally in frail health from birth, like Seneca before him, Marcus found that stoicism’s demotion of the corporeal world spoke to his own occasional infirmities. The emperor had a staggering round of daily duties, whether at home in the capital city or off directing a military campaign, and thus the general theme of the abnegation of pleasure and leisure that fills the Meditations is in no small part a result of its author’s perpetually overbooked schedule. And finally, when we look beyond the Meditations to read some of Marcus’ surviving correspondence, and other flotsam and jetsam that has survived about him in the historical archive, we encounter a much more three dimensional person – a man whose philosophy was not so much a dictative list of imperatives for self-improvement as it was a passionate and personal search for meaning and contentment in the midst of an inordinately demanding life.

There’s one logistical thing you should know about the Meditations before we get started, and that is that we have no evidence that this book was ever intended for publication and circulation. As scholar Christopher Gill notes,

Probably the work had no title and was not intended for publication but served as a purely private notebook for Marcus’ reflections. . .[Other than the first volume,] The. . .books show little of no sign of deliberate organization. It seems likely that Marcus simply wrote down one or two comments at moments of leisure, for instance, at the beginning or end of the day, and the resulting work is the sum of those comments.4

So, I’d like to begin the Meditations in Book 1, in which Marcus gives us an inventory of the people in his life who most influenced his career, and how they did so. Book 1 of the 12 books of the Meditations, as we heard a second ago, is the only one with a narrative that unifies it, this narrative being a sort of impersonal autobiography of how the emperor came to be who he was, and as we go through this important initial book, I’ll tell you about the Marcus’ early life up to the time he became emperor. Unless otherwise noted, quotes from the Meditations come from the Oxford World’s Classics edition, translated by Robin Hard and with an introduction and notes by Christopher Gill. [music]

Marcus Aurelius’ Autobiography in the Opening of the Meditations

Marcus Aurelius’ opening book of the Meditations is a mosaic of seventeen sections, each section being devoted to an important person in his life, explaining what he learned from each of them. The seventeen sections culminate in Antoninus Pius, Marcus’ adopted father and imperial predecessor, and thereafter the gods themselves. Let’s hear a sample of what Book 1 of the Meditations sounds like.

- From my grandfather Verus, nobility of character and evenness of temper.

- From the reputation of my father and what I remember of him, modesty and manliness.

- From my mother, piety and generosity, and to abstain not only from doing wrong but even from contemplating such an act; and the simplicity, too, of her way of life, far removed from that of the rich.

- From my great-grandfather, that I never had to attend the public schools, but benefited from good teachers at home, and to have come to realize that this is a matter on which one should spare no expense. (1.1-4)5

Antoninus Pius (86-161) stayed on the throne far longer than anyone anticipated, leaving Marcus Aurelius waiting in the wings until he was 40.

He tells us what he learned from Diognetus, his painting instructor, Quintus Junius Rusticus, who helped influence Marcus’ conversion to stoicism, Apollonius of Chalcedon, a stoic philosopher and orator, Sextus of Chaeronea, a prominent Platonist, Alexander the Grammarian, a literary scholar, Marcus Cornelius Fronto, a politician and orator whose correspondence with the emperor survives, Alexander of Selucia, another Platonist, Cinna Catulus, another stoic philosopher, and other figures still.6 Marcus thus offers shout-outs to a checkerboard of illustrious intellectuals, and we get an immediate sense that though popular history has pigeonholed him as a stoic through and through, Marcus’ education was eclectic and he respected all the philosophical traditions of his time. Biographers, including Cassius Dio, are keen to note that as emperor, Marcus restored instructor posts in Athens for the four main schools of his age – Platonism, Aristotelian philosophy, Epicureanism, and Stoicism. This was not the action of a narrow-minded partisan of stoicism. Like the henotheists of the early centuries CE, who worshipped mainly one god but acknowledged the vitality of others, Roman intellectuals of Marcus’ time period often preferred one school of thought, but didn’t necessarily see other schools as rivals.

In regards to his adopted father Antoninus Pius, Marcus has nothing bad to say. Antoninus Pius had been appointed by Hadrian as a stopgap between himself and Marcus Aurelius, Hadrian’s real choice for a successor. Marcus was not even 18 when Hadrian passed away, and so Pius, who was over 50 when he became emperor, and was not expected to live for very much longer, and he was seated as an interim figure to keep the throne warm for Marcus Aurelius. Antoninus Pius, however, lived far longer than anyone expected, ruling 23 years – the full duration of Marcus’ 20s and 30s, from 138-161 CE, leaving Marcus subordinate for much of his adult life. Old, eminently qualified, and reasonably capable, Antoninus Pius is the one member of Rome’s so-called Five Good Emperors about whom we know the least. General historical criticisms of his reign were that he was a bit too complacent, that his pacificism and non-interventionism punted foreign policy problems down the road for successors to deal with, and that in contrast to his globetrotting predecessor Hadrian, Antoninus Pius spent too much time in the marble halls of Rome and not enough dashing around the provinces, getting to know the subjects of his empire. However, considering that Romans had so recently had murderous narcissists on the throne in the previous century, and the interregnum of 69 CE had been even worse, the vast majority of people under Antoninus Pius were probably perfectly happy to have a drowsy and unconcerned middle aged gentleman in charge, and uncontested.

If Marcus Aurelius felt stifled and underused during his adopted father’s 23-year reign, it’s difficult to see any signs of frustration in what the younger emperor wrote about Antoninus Pius in the Meditations. Marcus writes, in the C.R. Haines translation,

From [Antoninus Pius], mildness, and an unshakable adherence to decisions deliberately come to; and no empty vanity in respect to so-called honours; and a love of work and thoroughness; and a readiness to hear any suggestions for the common good; and an inflexible determination to give every man his due; and to know by experience when is the time to insist and when to desist. (1.16)7

The long list of lessons learned from Antoninus Pius, while in close company with the older emperor, stretches several pages in length in this opening book of Marcus Aurelius’ Meditations, and in it we get a sense that Marcus, perhaps a little inclined to doctrinaire intellectualism in his late teens, learned how to be more compassionate, and more realistic, from working with the old senator-turned emperor for so long. A middle-of-the-road Roman man with no particular appetite toward ostentation, Antoninus Pius was too old and hardheaded to take public adulation very seriously, and he taught Marcus, by example, to understand the complexities of the senate, avoid the vulgarity and debauchery of the ultra-rich, and take the ebb and flow of popular applause with a grain of salt. And so while Marcus might have found his two decades in the older emperor’s shadow stifling, in the first pages of the Meditations we see that Marcus also understood that this period was key to his own development as a leader. As Marcus wrote later in the Meditations, “[T]he mind adapts and converts everything that impedes its activities into something that advances its purpose, and a hindrance to its action becomes an aid, and an obstacle on its path helps it on its way” (5.20). This is a very common idea in stoicism – that trials and tribulations are opportunities for growth and strengthening, and we can imagine Marcus taking the counsels of stoic philosophy and deliberately setting out to learn everything he could about imperial governance during his unexpectedly long apprenticeship under Antoninus Pius, rather than griping about not yet enjoying executive power.

On the whole, the first book of the Meditations, while little more than a distilled autobiography of Marcus Aurelius’ character traits, is a fitting introduction to his philosophy. If you are not familiar with the emperor’s unique strain of stoicism, the first book of the Meditations can seem kind of arrogant. In other words, Marcus creates a list of about a dozen and a half people, but says nothing about them other than what he has learned from them, and what he has learned is a long list of laudable character traits – fortitude, temperance, intellectual discipline, self reliance, social grace, and so on. Without understanding the strong element of collectivism which Marcus brought to stoic philosophy, and which Seneca’s works can so frustratingly lack, the opening book of the Meditations can seem like self-aggrandizement – a precursory introduction to the most important people in Marcus’ life who are only described insofar as they have helped form his character. As we’ll learn a little bit later in this episode, though, Marcus did not see himself as the central protagonist of his age, in the way that Caligula and Nero did in the century before him, and that Commodus would not long after ascending to the throne. While he can be viciously cynical, and see human relations at their grossest and most selfish and animalistic, Marcus also believed in the necessity of having others help form one’s character. And thus the opening book of the Meditations ought to be read not as a haughty catalog of all the great things he extracted from the people in his life, but instead a humble admission that Marcus Aurelius was the unwitting and fortunate product of a very specific set of social circumstances, and not some lone hero who figured it all out for himself. I think that the way Marcus conceives of the relationship between the self and society is his most profound and refreshing contribution to stoic philosophy, but again we’ll get into that a little later. For now, because it’s been a little while since we covered Seneca, let’s use the Meditations to look at a few places where Marcus rehearses some of the standard ideas of stoicism, and get stoicism 101 fresh in our minds. [music]

Marcus and the Stereotypically Stoic Parts of Stoicism

Stoicism, most stereotypically, tells us to be tough in the face of strife. This cardinal idea of stoicism isn’t about being resilient for its own sake, but instead about understanding how to rationally process one’s own hardships, and comprehend them as part of the unfolding of the interconnected, purposeful universe that is divinity itself. Don’t scream at the rock when you stub your toe, stoicism tells us – temper your kneejerk reactions to adversities and understand, even as the pain rages, that you and the rock are part of a great, rational unity. Stoic philosophers before Marcus Aurelius took up plenty of page space emphasizing this simple point – the need to see afflictions as part of a grand and logical order, and by extension, to use each endurance of a hardship as an opportunity to learn and improve oneself.To give a colorful example from Seneca, the earlier stoic philosopher wrote, “Misfortunes press hardest on those who are unacquainted with them: the yoke feels heavy to the tender neck. The recruit turns pale at the thought of a wound: the veteran. . .looks boldly at his own flowing gore.”8 Seneca often opted for extreme imagery when illustrating the astonishing forbearance of the stoic sage. Elsewhere, Seneca wrote,

For death, when it stands near us, gives [us] courage. . .to seek. . .the inevitable. So the gladiator. . .throughout the fight has been no matter how faint-hearted, offers his throat to his opponent and directs the wavering blade to the vital spot. . .[Outside the arena] an end that is near at hand, and is bound to come, calls for tenacious courage of soul; this is a rarer thing, and none but the wise man can manifest it.9

To Seneca, no analogy is too colorful to emphasize the toughness and serenity of the wise stoic under duress. Stoics, as courageous as dying gladiators, or disemboweled veterans looking bravely at their innards, are uniquely fortified to deal with any and all suffering that life throws at them, because they know that suffering is providential and cannot ever pierce the inviolable and interior worlds of their personal virtue and reason.

Marcus Aurelius, also writing on that cardinal stoic virtue of courage under fire, is characteristically milder than the fiery Seneca. Marcus writes in the Meditations, “On pain: if it is unendurable, it carries us off, if it persists, it can be endured. The mind, too, can preserve its calm by withdrawing itself, and the ruling centre comes to no harm; as for the parts that are harmed by pain, let them declare it, if they are able to” (7.33). In other words, when setbacks and pains come, withdraw into the serene cocoon of your own power of reasoning, and in all likelihood the crises and agonies of any given moment will appear less significant and become more bearable. Let’s hear another, longer quote from Marcus Aurelius on bearing adversity, this one from the tenth and second-to-last book of the Meditations.

Everything that happens either happens in such a way that you are fitted by nature to bear it or in such a way that you are not. If, then, it comes about in such a way that you are fitted by nature to bear it, make no complaint, but bear it as your nature enables you to do; but if it comes about in such a way that you are not fitted by nature to bear it, again you should make no complaint, for it will soon be the end of you. (10.3)

Seneca, whom we know well from our four episodes on him, had a far more grandiloquent and melodramatic style than Marcus Aurelius. The painting is Peter Paul Rubens’ The Dying Seneca (17th century).

Seneca and Marcus Aurelius, then, often communicate the same principles in very different styles. One of these principles is the most stereotypical tenet of stoicism – put simply, to grit your teeth and bear it. And to use another familiar colloquialism, a corollary of this central tenet of stoic philosophy might be the connected “What doesn’t kill you makes you stronger.” Or perhaps, “If you are rational and exercise control over your initial impulses, then what doesn’t kill you makes you stronger.” Marcus expresses this second standard stoic notion rather nicely at several points in the Meditations. He writes that a seaside cliff ought not to bemoan the waves crashing against it, but instead to be glad for the opportunity to show its fortitude, concluding, “So henceforth, in the face of every difficulty that leads you to feel distress, remember to apply this principle: this is no misfortune, but to bear it with noble spirit is good fortune” (4.49). Similarly, Marcus writes that just as Aclepius, the ancient god of medicine, prescribes treatments for people to endure, we should all accept our own trials as healthy and natural paths to personal betterment (5.8). Marcus is, as I said before, characteristically less bombastic than his stoic predecessor Seneca on the subject of self-improvement through suffering, but the gist of each writer’s thoughts on the subject are similar – misfortunes are opportunities for personal growth.

So these two tenets, likely more than any others, form the core of what most of us remember about stoicism – these notions that tell us that hardships must be understood as part of fate, and that strife can ultimately make us smarter and more resilient. Taken alone, these aren’t especially interesting ideas. It’s easy enough to understand that often passing miseries are transient in hindsight, that we all learn plenty from setbacks, and that there are some things you can’t change and just have to accept. If this really were all there were to stoicism, the philosophy would be little more than most of us learn by our senior year of high school – that sophomore year heartaches were, in retrospect, unimportant and ephemeral, that not making the cheerleading squad or football team was a blessing in disguise, and that, regrettably, the lot of us are dying slowly on a terrestrial planet filled with awful injustices, and very little can be done about any of it.

The stoics, however, were no pessimistic atheists who prescribed raising the shield of philosophy against the onslaught of a merciless universe. From the beginning, the stoics were part of a general trend toward monotheism that began in the historical record at the end of the Bronze Age, spread through the Hellenistic world through various cults, and by the second century CE was well on its way to displacing the old battle scarred polytheistic pantheons of the ancient Mediterranean. Stoics were what we call pantheists. Pantheism is the notion that god is the universe and the universe is god, and thus that everything that happens in the universe is part of a rational and providential process. This has been such a common idea in religion since early Christianity that it is exceedingly important that we realize that there was a time when the idea of universal divine providence was new – when the latent monotheism in Platonic dialogues like Timaeus uncoiled in Hellenistic philosophy over the final 300 years BCE and blended with various religions – Zoroastrianism, Judaism, and the henotheistic cults of Dionysus, Isis, and Cybele and had blossomed, by the second century CE, into ideologies that more and more emphasized a ubiquitous deity and divine providence. In the Gospel of Matthew, written about a hundred years before Marcus’ time on the throne, Jesus tells asks his disciples, “Are not two sparrows sold for a penny? Yet not one of them will fall to the ground apart from your Father” (Matt 10:29).11 Jesus here emphasizes the ubiquity of Christianity’s god – not a single sparrow falls from the sky apart from god’s providence. The authors of the New Testament, then, along with the stoics, lived their lives with the tempered comfort that the atrocities and hardships they saw in the world around them were all part of a godly agenda.

God and fate, although Marcus Aurelius discusses them in different terms than we’re used to in a world dominated by providential monotheism, are a cornerstone of his philosophy, and an issue that he returns to throughout the 12 books of the Meditations. So, now that we’ve gone through the most stereotypical aspects of stoicism in the Meditations, let’s explore what Marcus thinks about the forces at work behind the often harsh world he saw in front of him. [music]

Stoic Theology in the Meditations

In the ninth book of the Meditations, Marcus Aurelius very clearly sets out a dichotomy – specifically, the dichotomy between a universe animated by the reason of a single being, and a universe which is simply material collisions of atoms, or in paraphrase, whether or not god exists. The philosopher writes, “It is either the case that everything proceeds from a single intelligent source, as in a single body, and the part should not find fault with what comes about in the interest of the whole, or else there are simply atoms and nothing other than a random commingling and dispersal” (9.39). This, certainly, is a dilemma, and one still alive and well today. Elsewhere, Marcus reveals that in the dichotomy between divine providence and atomic materialism, he has a strong preference. In the C.R. Haines translation, Marcus writes,Either a medley and a tangled web [of atoms] and a dispersion abroad, or a unity and a plan and a Providence. If the former, why should I even wish to abide in such a random welter and chaos? Why care, for anything else than to turn again to the dust at last. Why be disquieted? For, do what I will, the dispersion must overtake me. But if the latter, I bow in reverence, my feet are on the rock, and I put my trust in the Power that rules. (6.10)

While he makes no protestation of faith or exhortation to share his belief, Marcus seems far more comfortable with the idea of a universe animated by godly reason than a universe that’s a mere demolition derby for atoms and everything made of them.

When fighting the Quadi in the southeastern part of the present day Czech Republic, and by all accounts not especially wanting to be there, Marcus Aurelius paused to jot down a longer rumination on the subject of divine providence. The basic message of this important entry in the Meditations is that the world pulses according to divine design, which gives everything we see in front of us significance and meaning. Marcus writes, again in the C.R. Haines translation,

Full of Providence are the works of the Gods, nor are Fortune’s works independent of Nature or of the woven texture and interlacement of all that is under the control of Providence. Thence are all things derived; but Necessity too plays its part and the Welfare of the whole Universe of which thou art a portion. But good for every part of Nature is that which the Nature of the Whole brings about, and which goes to preserve it. (2.3)

In Marcus’ view, a single god – a god which was the universe itself – was the animating spark or light behind everything we experience, and as we’ve seen in the past few quotes, without this unifying light of divine reason, the world is a drab billiards table of atomic collisions. Elsewhere Marcus emphasizes that everything in the universe is a part which serves the interests of the whole (8.19), that accepting one’s place in the universe’s agenda is a key to happiness (6.40, 4.40), and, perhaps in a moment of uncharacteristic optimism, that “All that comes about, comes about justly” (4.10). In an even closer parallel to Voltaire’s character Pangloss, Marcus reminds us to “[W]elcome whatever comes to us, even if it appears somewhat unpalatable, because it contributes to this great end, the health of the universe and the well-being and well-doing of Zeus” (5.8). I should note there that “Zeus,” by Marcus’ time, was in stoic circles no longer just the morally sketchy father of the Olympians, but instead a common name for the sovereign force that drove the universe.

From the time of Zeno of Citium (c. 334-262) onward, stoicism had been a religious philosophy, grounded in the idea of beneficent providence.

The historian Edward Gibbon, as we heard earlier, wrote that much of Marcus Aurelius’ century was “the period in the history of the world during which the condition of the human race was most happy and prosperous.” Admittedly, the fall of the republic two centuries prior, and thereafter the turbulence that would stretch between the death of Commodus in 192 and the ascension of Diocletian in 284 and involve some 30 emperors with an average reign of three years – all of these eras saw Romans killing more Romans then Marcus Aurelius’ did. But Marcus Aurelius’ dynasty nonetheless ruled over a populace crushed by income inequality and inflation, harrowed by high infant and child mortality rates, and for the final 15 years of Marcus’ reign, existentially threatened by a mysterious disease historians call the Antonine Plague. As is the case in so many civilized societies, a sect of cultured elites siphoned crippling amounts of money from those beneath them and lived opulent lives in urban centers, spending enough on a single or meal or garment to feed a village for a week. Rome’s historians seem justified in attesting to the popularity of, particularly, Trajan and Marcus Aurelius. But for the commoners and slaves who staffed farms, mines, and barracks – the critical mass of human beings we meet in the archaeological, rather than the literary record, the Nerva-Antonine dynasty was neither happy nor prosperous.

Biographer Frank McLynn, using an ensemble of sources, concludes that during the Nerva-Antonine dynasty,

The issue of the death rate is reasonably clear-cut. The life expectancy at birth for members of the senatorial class was thirty years and about twenty-five for others, though some authorities would downsize this to an average life expectancy of twenty-two for men and twenty for women. In Egypt the figure was 23.78 at birth, with the average age at death thirty-two to thirty-three; in other words, the death ratios in the Roman empire were comparable to those in England in the years 1200-1450 [, which include the Black Plague]. One-third of the population died by the age of twenty-eight months, and 40-50 per cent by the age of eight.

So during the 150s alone – just before he became emperor, Marcus Aurelius lost his mother, his sister, and six of his own children. Rome had, up until the time of Hadrian, been able to count foreign campaigns to help bring slaves into the empire and compensate for its high infant and child mortality rates. But the Antonine Plague, which raged from 165-180, killed somewhere between 10 and 18 million Romans, or around 1 or 2 in every 7 people.12 While the loss of life was catastrophic – especially in crowded areas and amidst the lower classes and slaves, the Antonine Plague also led to pernicious and far reaching economic problems. To simplify things dramatically, during his reign Marcus Aurelius saw the army depopulated, the workforce that staffed farms and mines and fed and paid for the army depleted, and fought a difficult, hardscrabble, expensive border war that yielded few payoffs in terms of looted treasuries and aristocratic palaces. Marcus’ adopted brother, the co-emperor Lucius Verus, had in the early 160s superintended a lackadaisical but in the end effective war with Parthia, sacking the wealthy metropolises of Seleucia and Ctesiphon at its climax. Marcus, whose war in the north was longer and more logistically debilitating, never got to bring home the glittering treasures of a foreign capital. Instead, his fate was to deal with the Antonine Plague his brother’s forces brought back from the east. Verus died in 169, leaving Marcus to deal with a set of problems that made almost anything any Roman emperor had faced up to that point look like a Christmas holiday.

Seeing a beneficent force ultimately animating the universe, then, helped Marcus trudge through some plague ridden years that may have looked, as they unfolded in the capital and the military camps along the Danube, like the end of the world. There is an optimism in the Meditations that is especially poignant considering the circumstances under which they were written, a sense that even as the emperor saw his subjects killed at the front, starved to death in the provinces, and dying by the millions from the plague, he tried to understand his grim tenure as emperor as part of something much larger. Stoicism, from its inception, was a philosophy built for harsh weather and meager harvests. Whatever we think of its ethics or its theology, it’s easy to see that stoicism could give a person like Marcus Aurelius a reason to keep his chin up and have hope in a better tomorrow.

An English edition of the Meditations from the Romantic period. Being a philosophical daybook, rather than a treatise like one of Seneca’s, Marcus’ Meditations has something for everyone, with all of the various moods it conveys. The Romantics, naturally, were drawn to the book’s assertive individualism.

The corollary of doing so, however, is oftentimes a denigration of the biological and material reality around us – the finite world of objects, our physical bodies, and the social worlds we inhabit. Stoicism’s optimism, put simply, comes with a cost, especially under the pen of Marcus Aurelius. Because while stoicism certainly got the emperor through some lean years, Marcus’ philosophy seems, from time to time, as though it may have preemptively sucked the sap out of his everyday peacetime life. Now, this is a commonplace and even trite criticism of stoicism – that its philosophical consolations require the disparagement of everyday joys, or that stoicism attempts, in D.H. Lawrence’s words, to “do the dirt on life.”13 But for a moment, let’s consider this criticism. So far we’ve seen Marcus’ philosophy in a threefold manner. It is a system that encourages forbearance and reason against strife, taking pains and setbacks as opportunities for personal growth, and having confidence that all perceived troubles and disasters are just parts of the unfolding of a great, interconnected, logical universe. Like turtles, stoics in the style of Marcus Aurelius always had recourse to a hard, protective encasement, but also like turtles, they carried this encasement with them, through fair weather and foul. Let’s look, then, at a few places in Marcus’ philosophy where his preemptively defensive psychological posture may well create the gloom and bleakness that it is built to help withstand. [music]

Stoicism’s Heavy Armor

The Book of Ecclesiastes begins with the words “[V]anity of vanities! All is vanity. What do people gain from all the toil at which they toil under the sun? A generation goes, and a generation comes. . .there is nothing new under the sun.” (Ecc 1.2-4, 9). These lines, avowing the cyclical and inconsequential nature of human life on earth, could have been written by Marcus Aurelius himself. Marcus writes in the Meditations, “There is nothing new, everything is long familiar, and swift to pass” (7.1). A couple of books later, Marcus repeats the same idea: “All things are ever the same, familiar in experience, ephemeral in time, foul in their material; all is just the same now as it was in the days of those whom we have consigned to the dust” (9.14). Dust in the wind may be our most colloquial metaphor for the impermanence of human existence nowadays, but it Marcus’ day it was autumn leaves. Alluding to the sixth book of Homer’s Iliad (6.146-9), Marcus writes, “Leaves that the wind scatters to the ground, / Such are the generations of men. . .And what are your children but leaves, and leaves too these people who acclaim you with such conviction and sing your praises, or, on the contrary, curse you, or reproach you in secret” (10.34).These ideas were fairly conventional in the second century CE and the thousand years beforehand. Marcus, who had lost so many of his own children, and seen so much death through war and pestilence, could abide by the assurance that the challenges he faced had been faced by those that had come before, and that individual human lives are fleeting amidst the gigantic, and ultimately orderly unfurling of the universe. We should pause for a moment and recall that the person writing these lines was no cloistered philosopher looking down on hordes of passerby, but instead the most powerful man in the Mediterranean world, and thus it is striking that a Roman emperor would tell himself, “Soon, very soon, you will be ashes or a skeleton, or simply a name, or not even that” (5.33). Elsewhere, Marcus vows to remember to “Think of substance in its entirety, of which you have the smallest of shares. . .and of the works of destiny, and how very small is your part in them” (5.24). Marcus’ humbleness here is less a result of personal self deprecation as it is a sense that actions by individual humans never have any far reaching consequences at all. Marcus writes, in the C.R. Haines translation,

Hippocrates, after healing many a sick man, fell sick himself and died. Many a death have [Babylonians] foretold, and then their own fate has overtaken them also. [Pompey] and [Caesar] without number utterly destroyed whole cities, and cut to pieces many myriads of horse and foot on the field of battle, yet the day came when they too departed this life. Heraclitus, after endless speculations on the destruction of the world by fire, came to [die, too]. And lice caused the death of Democritus, and other vermin of Socrates. (3.3)

Again, considering the tremendous egos of Rome’s Augustuses, Caligulas, Neros, and Commoduses, it is remarkable that Marcus understood his own place in history with such merciless clarity. The Meditations show us a military commander embroiled in a war he did not want to fight and that he refused to romanticize, and subsequently a person who must have found his duties at times crushingly depressing. At other times, however, Marcus’ general dismissal of earthly matters as ephemeral and inconsequential was a bulwark against assigning any special significance to the sufferings of any given day. Midway through the Meditations, Marcus writes, “Constantly reflect on how swiftly all that exists and is coming to be is swept past us and disappears from sight. For substance is like a river in perpetual flow, and its activities are ever changing, and its causes infinite in their variations, and hardly anything at all stands still” (5.23). He is thinking here of the Presocratic philosopher Heraclitus, who wrote that “It is impossible to step twice into the same river.”14 A river, so Heraclitus writes, constantly changes shape, and so one can never revisit exactly the same channel of water. And the corollary, as far as Marcus seems to be concerned, is that existence should encourage neither pomposity nor self-pity; neither great pride nor great self loathing, because each life is a mere particle in the billowing universe.

Dust in the wind, leaves on trees, water in an ever-changing river – these metaphors for human existence, since the Bronze Age, have been cautionary bumpers for us, telling us to be neither arrogant nor despondent, because we are small parts of something much larger. Like many who came before him in philosophical history, Marcus Aurelius often reminded himself of the transience of material existence. But he frequently took it a step further than this, joining a long line of thinkers in devaluing the world of the senses as something inferior, and even contemptible. It’s one thing to think of one’s species as leaves that only live for a season, but quite another to express disgust and aversion to the ultimately transitory world of one’s sensory experiences. Marcus does the latter early, and often throughout the Meditations.

He tells himself in the second book of his work, “[D]espise the flesh. . .just blood and bones and a mesh of interwoven nerves, veins, and arteries” (2.2). Later he describes “our senses dull, [and] the fabric of our entire body subject to corruption” (2.17). He worries intensely that “the more divine part of you has been overpowered and has succumbed to what is inferior and perishable in you, your body, and its gross pleasures” (11.19). And, in one of the more fiercely ascetic passages of the Meditations, Marcus writes, again in the Oxford Robin Hard translation,

When you have savouries and fine dishes set before you, you will gain an idea of their nature if you tell yourself that this is the corpse of a fish, and that the corpse of a bird or pig, or again, that fine Falernian wine is merely grape-juice, and this purple robe some sheep’s wool dipped in the blood of shellfish; and as for sexual intercourse, it is the friction of a piece of gut and, following a sort of convulsion, the expulsion of some mucus. (6.13)

This, and other passages in the Meditations, show that Marcus could be ruthlessly unsentimental about the niceties of life, reducing things to their basest function – the food on the table is a heap of corpses, the wine fermented juice, the fine garments merely animal fur dyed with extractions from other animals, and the sex afterward no more profound than that which would occur between a pair of mice or insects. The passage we just read is as depressing as it is logically unassailable, and suggests the emperor’s tendency to peel away the fictions and veneers of civilization and view humanity at its animalistic core.

Marcus Aurelius, like the stoics before him, subscribed to Plato’s notions that the mass of humanity is benighted but for a select few, and that a sacred divine providence is higher and more important than the transient sludge of the material world.

The first sentence of the philosophical portion of the Meditations is fiercely cynical. Marcus writes, “Say to yourself at the start of the day, I shall meet with meddling, ungrateful, violent, treacherous, envious, and unsociable people” (2.1). We have to remind ourselves that as an emperor, and an intelligent one, Marcus must have perceived a lot of pretense and disingenuousness in the court, and that as a military commander, he would have witnessed violence as extreme as the ancient world had to offer. However, Marcus’ preemptive assumption that the people he will meet with are, again, “meddling, ungrateful, violent, treacherous, envious, and unsociable people” shows that he was as capable as any stoic philosopher of demeaning the mass of humanity as benighted simians stuck in a lightless Platonic cave. These same people, Marcus tells us in his opening, “are subject to all these defects because they have no knowledge of good and bad” (2.1). The Meditations are filled with negative remarks about the average human being – toward the book’s end, in a single, brief entry, Marcus writes “They despise one another, yet they fawn on one another, they want to climb over one another, yet they grovel to one another” (11.14). Elsewhere, Marcus envisions those ignorant of virtue, “and what sort of scum they mix with; and accordingly, [the wise man] sets no value on praise from such people, who are not pleasing even to themselves” (3.4).

When we encounter contempt for humanity in ancient philosophy, whether in Ancient Egyptian proverbs, or Ecclesiastes, or elsewhere in the Bible, or Plato, or the stoics, misanthropic statements most often rely on an in-group and an out-group. The in-group is, of course, the practitioners of this or that philosophy or religion who know the secret handshakes and code words. The out-group is a vaguely imagined mound of everyone else – teeming hordes of benighted outsiders who don’t understand the full story. In the Meditations, Marcus Aurelius most often emphasizes this dichotomy in order to dismiss the importance of public opinion on the actions of a wise man. In Book 4, he marvels, “What ease of mind a person gains if he casts no eye on what his neighbor has said, done, or thought, but looks only to what he himself is doing. . .Do not look back to examine the black character of another, but run straight towards the finishing line, never glancing to right or left” (4.18). This is a familiar enough theme to sound like a platitude – “To thine own self be true,” says Shakespeare’s Polonius. “Trust thyself: every heart vibrates to that iron string,” Ralph Waldo Emerson advises us. In whatever century it shows up, the doctrine of self reliance seems to arise out of a desire for personal assertion against the centripetal motion of civilization.

To return more specifically to Marcus Aurelius, occasionally the Roman philosopher recommends an extreme, and unsettling degree of self reliance. At his milder moments, like most writers on the subject, Marcus reminds himself not to worry too much about what others think (2.6, 2.8, 4.20). Marcus makes the standard stoic maneuver when he writes, “Remember that your ruling centre becomes invincible when it withdraws into itself and rests content with itself. . .nowhere can one retreat into greater peace or freedom from care than within one’s soul” (8.48, 4.3). But sometimes Marcus takes things several steps further, emphasizing that a wise man needn’t pay any heed to anyone at all, and that a real wise man can simply follow his own dictates and what he perceives the nature of the universe to be. Marcus writes, “Consider every word and deed that accords with nature to be worthy of you, and do not allow yourself to be turned aside by the criticisms and talk that may follow. . .do not trouble yourself about that, but proceed directly on your course, guided by your own nature and by universal nature; for both of these follow one single path” (5.3).

These words, in my opinion, are a little bit dangerous. Following one’s heart, fighting for what one believes in, not worrying too much about conformist inertia of society, or maybe just getting an eyebrow ring or an eccentric tattoo – these are all within the gospel of self reliance. But what Marcus proposes at some of the more intense junctures of the Meditations is a bit more extreme – a wholesale disregard of society and the pursuit of one’s ideals according to one’s perception of the divine. The Meditations, at key moments, promote a gospel of diffusion – of loners who do not listen to one another, and perhaps more perilously, who collectively believe that their mental meanderings are consecrated by divinity. This extreme doctrine of aloof self-reliance, along with Marcus’ preoccupation with the shortness of life, and his ruthless disparagement of the enjoyments of the physical world, collectively suggest a man with a rather dark view of the universe – one who chose to put on chain mail and a thick metal helmet and squat down on the ground rather than venturing forth unarmored and risking disappointment and calamity.

But there is a lot more to Marcus Aurelius than grim asceticism and crabbed self reliance. What we have to remember when we read the Meditations is that it likely functioned as a sort of diary to the emperor, capturing his gloomiest moments as well as his most optimistic. He could be cynical and dour toward his species, and the physical world that he saw in front of him, as was so common in the ideological trends of the second century. But Marcus could also, incredibly, depart from the entire main line of ancient ethical philosophy, and write the following:

When you want to gladden your heart, think of the good qualities of those around you; the energy of one, for instance, the modesty of another, the generosity of a third, and some other quality in another. For there is nothing more heartening than the images of the virtues shining forth in the characters of those around us, and assembled together, so far as possible, in close array. So be sure to keep them ever at hand. (6.48)

From what you’ve heard so far, these sentences seem like they might have been written by a different person. Stoics in the line of Seneca are especially unlikely to warmly reflect on the virtues around them in contemporary society. At the heart of stoic ethics is the notion that pursuing virtue is the one unassailable thing that a person can do in an egregiously unjust world. Marcus himself, as we heard earlier, wrote that a wise person should “run straight towards the finishing line, never glancing to right or left” in the pursuit of virtue, as though the rest of the species were merely ambient noise. But frequently elsewhere – during his good days, perhaps – the emperor perceived society, and social interaction, to be happy and edifying. Let’s look at some of those passages – passages in which Marcus takes a few steps away from the stoic flock and advances the stunning theory that the people in the world around us may not just be worthless and irrelevant sacks of meat. [music]

The Lighter Side of Marcus Aurelius

We’ve heard a lot of Marcus Aurelius the sourpuss. At his darker moments, the philosopher could disparage society, obsess on the frailty of the human condition, and see central human joys like food and sex as slimy and bestial and unclean. And we’ve learned that he had a lot to be pessimistic about – his children dying, long wars in the north and the east, half his adult life spent under another emperor who was supposed to be a stopgap to his own reign, and a plague that killed millions of his people and permanently broke the foundations of the empire’s economy and military, not to mention the general scheming and disingenuousness of the Roman court. Had Marcus Aurelius left behind mere ire and pessimism in the Meditations, it would be easy enough to forgive him. Inasmuch as he was born to privilege, he must have felt something like a punching bag during much of his tenure on the throne, and the bleakest moments of the Meditations show a person who appears bitter, resigned, and alone.

Marcus’ daughter Lucilla. The Emperor’s correspondence with his teacher Marcus Cornelius Fronto show evidence of Marcus’ enjoyment of family life, however much the Meditations might lead us to conclude that he had no time for such a thing.

The eating, drinking, sociable Marcus Aurelius makes frequent appearances in the Meditations. Alhough elsewhere he warns his reader not to place any stock in the assessments of others, at several junctures Marcus reveals that he values good advice. He writes, “If anyone can give me good reason to think that I am going astray in my thoughts or my actions, I will gladly change my ways. For I seek the truth, which has never caused harm to anyone; no, the person who is harmed is one who persists in his self-deception and ignorance” (6.21). This is quite a different idea what we saw in earlier passages we looked at – passages in which Marcus says one should “not allow yourself to be turned aside by the criticisms and talk” and that one must “run straight towards the finishing line, never glancing to right or left.” The earlier passages endorse dogmatism and self-righteousness; the latter, listening to any and all opinions in the pursuit of truth and solutions to problems. On the surface, these are contradictory pieces of counsel, but perhaps Marcus understood, as we do, that there are times when you have to go your own way regardless of conventions, and there are times when you need to listen to input to guide your decisions, and everything in between.

Marcus is at his best and most beautifully eloquent when he ponders the sometimes contradictory mandates of a stoic philosopher and a Roman emperor. At one point in Book 4, Marcus tells himself, “You should always be ready to apply these two rules of action, the first, to do nothing other than what the kingly and law-making art ordains for the benefit of humankind, and the second, to be prepared to change your mind if someone is at hand to put you right and guide you away from some ill-grounded opinion” (4.12). Stoic philosophers might be read forever in the walled gardens of their personal ethics, but Marcus had an empire to run, and he couldn’t do it alone. In a dramatic departure from the more misanthropic moments of the Meditations, Marcus writes, “See that you never feel towards misanthropes as such people feel towards the human race” (7.65). In other words, forgive misanthropes – not even they deserve the scorn they pour on others. These pieces of self-counsel, in which Marcus tells himself to abide by his principles, but listen to those around him too – and to never let the things he sees make him hate mankind, are some of the more open hearted parts of the emperor’s book.

While some parts of the Meditations reflect very cynically on human civilization, and others actively encourage a self reliant ducking out of society, Marcus also, paradoxically, understands that if everyone behaved like a hermit, humanity would not be able to improve itself through interchange and constructive criticism. On this subject, in Book 5 of the Meditations, Marcus reminds himself how important it is to communicate with others when he sees room for improvement in their behavior. He writes, in the C.R. Haines translation,

If a man’s armpits are unpleasant, art thou angry with him? If he has foul breath? What would be the use? The man has such a mouth, he has such armpits. Some such effluvium was bound to come from such a source. But the man has sense [you think]. With a little attention he could see wherein he offends. I congratulate thee ! Well, thou too hast sense. By a rational attitude, then, in thyself evoke a rational attitude in him, enlighten him, admonish him. If he listen[s to your advice], thou shalt cure him, and have no need of anger. (5.28)

On one level, this is just common sense advice – we really ought to tell one another when our flies are down or there’s spinach in our teeth. On another level, though, this little aphorism on body odor is a profound departure from stoic philosphy. Stoics believed in the pursuit of virtue – in always having recourse to the bomb shelter of individual ethics in the event of calamity. In what we just heard, though, Marcus proposes that the pursuit of virtue is also a communitarian, collective process – that we all have blind spots in regards to our deficiencies and we need others to tell us about them. Humble and modest to the core, Rome’s philosopher emperor lived too public a life to believe that he could figure it out all on his own, and knew that society is mortared and strengthened through critique and advice. Disconcertingly, the idea of humanity as an interconnected organism that improves itself through the interchange of its parts was not common in what has survived from the philosophy of antiquity. Ancient philosophers who believed in innate ideas, absolute universal morals, and connections with the divine would have scoffed at the notion that humanity probabalistically works out truths as a collective. And while Marcus can occasionally come off as misanthropic and reclusive as anyone, he also seems to have understood that quietly resenting the foibles of others and then scurrying off to brood in solitude is not a good way of making the world a better place.

Maybe the most remarkable part of Marcus’ work is this. He loves the idea of stoic philosophers as romantic figures, unconquerable in their moral self-confidence. But at the same time, he knows that this is not who he is, and he finds peace and beauty in the imperfect and improvised world of human interaction. Marcus’ life was not an academic one. He spent his reign often quite literally in the trenches, collaborating with couriers, generals, military engineers, supply coordinators, diplomats, indigenous peoples, family, friends, and a bevy of politicians. The intensity of the burdens he shouldered, and the incessantly social nature of an imperial life led him to a more collectivistic view of humanity than stoicism had embraced up to that point. Seneca may have seen stoic philosophers as atomized seekers of virtue, cleaved from the crude herds due to their asceticism and staunch intellectualism. To Marcus, though – again in spite of the fact that he sounds awfully reclusive at points in the Meditations – there is something ultimately tragic about those who chose to remove themselves from society. He writes, near the end of the Meditations in the Haines translation,

A branch cut off from its neighbour branch cannot but be cut off from the whole plant. In the very same way a man severed from one man has fallen away from the fellowship of all men. Now a branch [of a plant] is cut off by others, but a man separates himself from his neighbour by his own agency in hating him or turning his back upon him; and is unaware that he has thereby sundered himself from the whole civic community. (11.8)

It’s a remarkable little passage for several reasons. Stoics, as we learned earlier, could be generally described as pantheists – those who believe that everything, and everyone, in an interconnected unity, is god, and that god is characterized by reason. To Marcus, then, a person who actually tried to disintegrate himself from society was committing a blasphemy against the generally adhesive forces of the universe. But there’s something else striking about Marcus’ tree and branches analogy for humanity and the universe, and that’s just how similar it sounds to a certain book that was just beginning to become a book during the second century – a slender volume we now call the New Testament. [music]

Stoicism and Early Christianity

In the Book of John, as Jesus bids farewell to his Apostles, he tells them, “I am the vine. . .you are the branches. . .Those who abide in me and I in them bear much fruit, because apart from me you can do nothing” (John 15.5). Plants and branches, wholes and parts – these metaphors for humankind and the universe in Marcus Aurelius, the Bible, and elsewhere, demonstrate that in the thousand or so years that elapsed between Homer and the end of the pax Romana in 180 CE, the ancient Mediterranean, whether in sacred writings or secular philosophy, was beginning to think big. Religious narratives of the Bronze Age covered in this podcast – the Epic of Gilgamesh, the Kumarbi cycle, the Ba’al cycle, the Enuma Elish, the Contendings of Horus and Set – these are pluralistic tales in which generations of colorful figures spar for sovereignty, and humanity is mashed and maimed as collateral damage. But Marcus Aurelius, like the authors of the Gospels, had a simpler, and perhaps more appealing explanation. Marcus wrote, “[T]here is one universe made up of all that is, and one god who pervades all things, and one substance and one law, and one reason common to all intelligent creatures, and one truth” (7.9). The quote again comes from Marcus’ Meditations, but it could have been written anywhere in the New Testament, or, for that matter, the Qur’an. So, too, could Marcus’ “In this world there is only one thing of real value, to pass our days in truth and justice, and yet be gracious to those who are false and unjust” (6.47), his doctrine of turning the other cheek not too different from Christianity’s. We already talked about the parallels between Senecan stoicism and key passages of the New Testament – especially Acts. It should thus come as no surprise that ideas from the Meditations crop up all over the Gospels and beyond. If we imagine Christianity emerging into a staunchly polytheistic world in the second century, we neglect to remember how much Greeks and Romans were trying out other options – salvation based cult religions, monist philosophies like stoicism, and moreover ideologies centered on rectitude in personal ethics, all of which had important similarities to Christianity.The extent to which Christianity itself directly catalyzed the fall of Rome has been a subject of interest since Edward Gibbon published the multivolume History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire in the 1780s. In a famous passage in Volume 3, Gibbon writes that as Christianity rose, “The clergy successfully preached the doctrines of patience and pusillanimity; the active virtues of society were discouraged; and the last remains of military spirit were buried in the cloister: a large portion of public and private wealth was consecrated to the specious demands of charity and devotion; and the soldiers’ pay was lavished on the useless multitudes of both sexes who could only plead the merits of abstinence and chastity.”15 Oh, those awful ancient Christians, choosing peace and charity over manly warmongering. Gibbon’s assessment of Christianity’s impact on Rome is more sophisticated than this, of course, but I’ll share a quote from scholar Frank McLynn to give you a more complete picture of all the things going on during Marcus Aurelius’ reign – again 161-180, and how the emperor dealt with them. Biographer Frank McLynn writes,

When faced with obvious threats to the empire, such as those from Parthia and the German tribes, Marcus acted decisively and probably wisely. . .But Marcus never saw beneath the surface of events. His defenders say that even if he had or could have done, the travails that assailed Rome by the end of his reign were those of ‘systemic failure.’ Rome, in a word, stopped getting bigger, better, more integrated, more complex, more meritocratic and more socially fluid, and simply ossified into changelessness. There is a considerable consensus that things started to go badly wrong during his reign, but that these lay beyond the scope and grasp of any emperor, no matter how far-sighted. . .Rome was not yet in the terminal stages of decline, as evidenced by the fact that the empire could absorb a Commodus and survive, as it would not have been able to do post-260. For a little while, too, military conquest and the subsequent import of looted wealth and new slaves could compensate for the lack of technological innovation and a stagnant economy. But the writing on the wall was there for those who chose to read it. Under Marcus the delicate equilibrium of the imperial system was disturbed: that between the power of frontier defence and barbarian incursion; between the exigencies of war and the resources of the state; between production and consumption and town and country; between the authority of the Senate and unbridled imperial power. . .[and] the increasing urbanisation of the empire was already producing those seemingly modern phenomena of rootlessness, anomie and anxiety, all exacerbated by natural and military disasters, the crisis of religious belief and population implosion in urban areas.16

Marcus Aurelius presided over a period when Rome was beginning to come apart at the seams. Perhaps those occasional, poignant moments we looked at in the Meditations – those moments when he urges togetherness and unity rather than atomization, were his most optimistic – moments where he hoped that just as a divine plan guided all creation, he might, in his much humbler way, try to help steer Rome back toward cohesive order in spite of a mass of empirical evidence that was beginning to show that it was coming apart. And while the optimistic portions of the Meditations show a figure capable of immense hope in the midst of calamity, the darker parts of the emperor’s philosophical daybook demonstrate that his life took a heavy toll on him, and that sometimes not even the consolations of stoicism could save him from horror at the things he had seen. And while most historians regard Marcus’ reign as reasonably successful, and intellectuals from Augustine to Boethius to Thomas More to Adam Smith, Kant, Darwin, Nietzsche, J.S. Mill – and the list goes on – revered various aspects of his philosophy, there is universal accord that Marcus committed one abominable act of failure upon his death on March 17, 180 CE. That failure, of course, was having set up Commodus as his successor. Because Commodus, as you may well know, turned out to be hell on Earth.

The Meditations show an emperor who, like so many of us, fluctuated between optimism and pessimism depending on the vagaries of any given day. As the 160s spilled into the 170s, and as the Marcomannic Wars dragged into their awful 13th and 14th years, Marcus seems to have increasingly realized that the luminous education of his youth – the one he details so carefully in the first book of the Meditations – had been no sound introduction to his actual duties as emperor. A troupe of tutors may have taught him the fine points of rhetoric, philosophy, and literature, but through the emperor’s mid-40s onward, his duties were largely military ones, and he must have thought back to his lavish education under Antoninus Pius with the sense that his intellectual training had ultimately been irrelevant to the hard knocks of his military career. And this realization, as the monotonous brutality Marcomannic Wars wore him down, affected the way that he raised his own son, Commodus. Born shortly after Marcus Aurelius ascended to the throne, Commodus spent his teenage years intermittently in and out of military camps, unlike his father, who had spent his early decades in Rome. Marcus Aurelius sought a practical education for Commodus – the boy had little need of a scholar’s education, if Marcus’ experience on the throne were any indication. Lacking the intellectual grounding of his father, though, and having not a shred of the modesty and compassion that fills the Meditations, Commodus was a monster who adored torturing, mutilating, and killing for pleasure. He was the first Roman emperor to be born the son of a Roman emperor, and his horrifying twelve years on the throne reminded Romans of all stamps that though the empire was now two centuries old and counting, and though it had enjoyed general stability beneath the Nerva-Antonine dynastry, with a single faulty succession, everything could change.

As Rome entered the roller coaster of the third century, then, multiple ideologies were available to the person on the street that promised her there was beneficent order at work behind the ostensible chaos and instability. And in the survival of the fittest of Roman religions, Christianity began outstripping its rivals over the course of the 200s CE, enclaves of believers polka-dotting the populous parts of the Mediterranean coastline more and more prior to Constantine’s passage of the Edict of Milan in 313. In the fifty years between 235 and 284, Rome had more than 25 men proclaim themselves emperor, and barbarians continued to chop away the extremities of the empire, and civil wars, peasant uprisings, new waves of plague, currency debasement, and economic depression dragged generations of Romans and others into a general search for hope and meaning. Stoicism had long promised that serenity could come through the pursuit of reason and virtue, and the careful control of emotion and passion. But Christianity offered more – a personal, patriarchal deity whose working class background and underdog status mirrored those of the generations who began to flock to him over the 100s and 200s, the promise of a blessed afterlife, and an inclusiveness and anti-elitism that spoke to commoners sick of a greedy and entrenched aristocracy. Christianity didn’t replace stoicism – under the pen of Saint Paul and others, Christianity simply consumed stoicism, repurposing its ethics of self control and virtuousness and modifying its pantheism into the theology practiced by so many today.

We seem, though, to be entering a period during which stoicism has began to have an appeal again. At its worst, stoicism can sound self-righteous, elitist, and woefully doctrinaire – I mean when Marcus Aurelius tells us that we should think of the death of our children as nothing more than leaves falling, or when Seneca tells us that a disemboweled soldier ought to watch himself bleed out with contentment – these pieces of counsel, for most of us, are absurd. But for quite a few more of us, perhaps, stoicism’s sense of unity – in Marcus Aurelius, stoicism’s notion that we are all in it together and we need to communicate and correct one another to serve the ultimate harmony of the universe – this aspect of stoic philosophy is a useful one in modern communities beset by increasingly brazen factionalism. And for more of us still, stoicism reminds us that while we may bemoan our sufferings and seek solace from others, there are times when it’s best to take a deep breath, remember our relatively small place in the cosmos, and walk it off. [music]

Moving on to Season 5 and the New Testament

Well, Literature and History listeners, this takes us very nearly to the end of our long sequence on Roman literature. The period historians today call Late Antiquity, or roughly 200 through 650 CE – sometimes 800, is next on the horizon, and historians of the era often begin the period with Marcus Aurelius himself, the last in the sequence of Rome’s Five Good Emperors. Late Antiquity, once stereotypically conceived in academia as a decline into superstition and warfare, is increasingly being understood with a lot more nuance. As we’ll see again and again in the next two seasons, the decline of the western Roman Empire was a very gradual one, and the rise of Christianity wasn’t so much the sudden sunburst of a new faith from the east as it was the synthesis of dozens of ideologies and worship communities, including stoicism. As Peter Brown, the foremost historian on the period, puts it,Some scholars emphasize the impact of alien ideas and of alien cults as primary causes of the end of classical pagan civilization and tend to present the religious changes of the third century as the final breaking through of intrusive elements that had built up in the Roman world over. . .centuries. In doing, they assume a rigidity and vulnerability in later classical paganism that exists more in their own, idealized image of such a paganism than in the realities of the second century A.D. . .the changes that come about in Late Antiquity can best be seen as a redistribution and a reorchestration of components that had already existed for centuries in the Mediterranean world.17

In the Greek language in which the New Testament was produced, stoicism was one of the Roman Empire’s ascendant ideologies. Today, it’s frequently simplified as an ethical philosophy prizing personal tough mindedness and self-reliance, and the philosophy’s association with monotheism and pantheism, unfortunately, gets underplayed. The stoic’s strength in the face of adversity, in the first and second centuries CE, came not merely from grim forbearance, but from faith in the implicit harmony of the universe, as ministered by a higher power. What remains of the primary texts of stoicism – Cleanthes’ Hymn to Zeus, and the works of Seneca, Epictetus, and Marcus Aurelius – collectively leads us to the understanding that stoicism was an intensely spiritual philosophy, and not some secular ethical rulebook. The tranquility of the ancient stoics – their grace under fire, was anchored in their faith in a prime deity. Marcus Aurelius, like his stoic forebears, was a deeply spiritual person, his confidence in an immortal divinity being at the core of what would otherwise be a rather hollow and severe ideology.

And just as the monotheism or pantheism at the heart of stoicism often gets downplayed, more generally, the spiritual side of Ancient Greek philosophy has been ignored or de-emphasized by historians who, whatever their reasons, wish to present the rise of Christianity as the beginning of something categorically different in the Ancient Mediterranean. Plato, who channeled the religious crosscurrents of the fifth century BCE to all posterity, synthesized the cult movements of his century into a philosophy. And Plato’s various colorful stories of creation, higher realms of consciousness, differentiated afterlives, initiated sects, and absolute reality belong to religious history as much as they do philosophical. With important exceptions, the philosophical history of the Mediterranean was not a godless and secular one, and so when we hear Peter Brown summarizing Christianity’s first centuries as “a redistribution and a reorchestration of components that had already existed for centuries in the Mediterranean world,” we need to remember that these components included stoicism, a philosophy that ultimately became one of the fibers of Christianity.

Next time, in Episode 75: Dusk and Starlight, we’re going to consider where we’ve been, and where we’re going, as we finally prepare to open the New Testament, and learn about the world that produced it. I will also be releasing not five but ten new bonus episodes – this content will take just a little longer to prepare, so expect Episode 75 and these other materials out in mid-April. I have a quiz on this episode on the website if you want to review what you’ve learned about Marcus Aurelius – to take the quiz, just open up the show notes or episode description in your app, and click the first link. For you Patreon supporters, I’ve recorded the entire second book of Marcus Aurelius’ Meditations for you to listen to from an out-of-copyright translation – I think the second book is representative of the entire collection and I also think it’ll be nice for you to hear a long duration of Marcus Aurelius in his own words – there’s a link to the Patreon page there in the show notes in your app, too, if you want to pledge a dollar per new show. If you want to hear a song, I’ve got one coming up, and if not, see you next time.

Still here? Well, Marcus Aurelius life and times aren’t exactly brimming over with potentially funny topics – I mean the guy had a pretty hard, demanding life, and I think most of us who read his biography wish we could go back in time and somehow see to it that he got more vacation. Anyway, one point that so many students of Roman history get hung up on is the question of why in the world Marcus Aurelius set his five year old son Commodus up in 166, on the track to imperial ascension. Marcus understood well enough that life was nasty, brutish and short and his philosophical works don’t really display any sense that he’s going to live forever. Additionally, he himself was the product of a tremendous education and imperial apprenticeship, and so for all of these reasons it’s pretty hard to imagine why Marcus decided to hand the throne on down to a little tadpole who was absolutely unqualified. In order to conjecture about this perennial question, I have written the following skit and song, which is called “Some Day My Son,” and takes a stab at understanding Marcus’ reasoning for bequeathing the empire to Commodus. I want thank my friend Nick Osbourne for helping me out with this song – he plays a couple of its characters. I hope you like this one, and we’ll be back soon with more.

[“Some Day My Son” Song]

References

2.^ On Commodus’ education see McLynn, Frank. Marcus Aurelius: A Life. De Capo Press, 2009, p. 426.

3.^ From Selections from the Prose Works of Matthew Arnold. Edited and with an Introduction and Notes by William Savage Johnson. Houghton Mifflin Company, 1913.

4.^ Gill, Christopher. “Introduction.” Printed in Meditations, with Selected Correspondence. Translated by Robin Hard and with an Introduction and Notes by Christopher Gill. Oxford University Press, 2011, p. viii, ix.

5.^ Aurelius, Marcus. Meditations, with Selected Correspondence. Translated by Robin Hard and with an Introduction and Notes by Christopher Gill. Further references in this transcription are noted parenthetically with Book and Section numbers.

6.^ See ibid, pp. 143-5.

7.^ Marcus Aurelius. The Communings with Himself of Marcus Aurelius Antoninus. Translated by C.R. Haines. William Heineman, 1916, p. 13.

8.^ On Providence (IV). Quoted in Delphi Complete Works of Seneca the Younger. Delphi Classics, 2014. Kindle Edition, Location 27667.

9.^ Epistulae ad Lucilium XXX.7. Quoted in Ibid, Location 8478.

11.^ Coogan, Michael, Michael D., ed. et. al. The New Oxford Annotated Bible. Third Edition. Oxford University Press, 2001, p. 22 New Testament.On the dating see p. 8 New Testament.

12.^ See McLynn (2009), p. 466.

13.^ Quoted in McLynn (2009), p. 67. McLynn’s own assessment of stoicism is much more nuanced, but not particularly favorable.

14.^ Robin Waterfield, Ed. The First Philosophers: The Presocratics and Sophists. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000, p. 41.

15.^ Gibbon, Edward. The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire. Delmarva Publications, 2013. Kindle Edition, Location 45915.

16.^ McLynn (2009) pp. 456-7.

17.^ Brown, Peter. The Making of Late Antiquity. Harvard University Press, 1978, pp. 7, 8.