Episode 79: The Pauline Epistles

Possibly the most influential theologian in history, Paul codified and clarified Christianity as it emerged into the diverse world of the Eastern Mediterranean.

| Read Transcription | References and Notes |

| Episode Quiz | Episode Song |

| Episode on Spotify | Episode on Apple Podcasts |

| Previous Show | Next Show |

The Letters of Saint Paul, c. 50-65 CE

Gold Sponsors

ML Cohen

John David Giese

Silver Sponsors

Chad Nicholson

Jaclyn Stacy

John Weretka

Lauris van Rijn

Michael Sanchez

Patrick Radowick

Sponsors

Alejandro Cathey-Cevallos

Alysoun Hodges

Amy Carlo

Angela Rebrec

Benjamin Bartemes

Caroline Winther Tørring

Chris Brademeyer

Daniel Serotsky

Earl Killian

Francisco Vazquez

Henry Bakker

Jeremy Hanks

Josh McDiarmid

Joshua Edson

Kyle Pustola

Laurent Callot

Leonie Hume

Lucas Deuterman

Mike Swanson

Oli Pate

RH Kennerly

Anonymous

Rod Sieg

De Sulis Minerva

Rui Liu

Sebastiaan De Jonge

Sonya Andrews

Susan Angles

Verónica Ruiz Badía

The letters attributed to Paul are addressed widely – all over Asia Minor, mainland Greece, and even to the island of Crete.1 The period of their composition stretches 15 or even 20 years from earliest to latest. The earliest of them, First Thessalonians, written from Corinth to the mainland region of Thessalonica, warmly greets Paul’s congregation there and discusses the afterlife as the earliest Christians were beginning to formulate it. Galatians, from this same period, is written to churches in the north-central Anatolian province of Galatia around 50 CE, and it shows Paul already working on one of the Apostolic generation’s central concerns – whether Gentile converts needed to follow the extensive Mosaic Law outlined in the first five books of the Bible. Paul’s latest and longest epistle, Romans, was likely produced some time around 60 CE, and it demonstrates Paul’s continuing dedication to creating an ecumenical, one-size-fits-all Christianity with a simple doctrine of salvation, and a courteous but firm dismissal of pagan religion and philosophy.

One of the most important things to keep in mind when dealing with the Pauline Epistles is that they are older than the Gospels and the Book of Acts. We might today have Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John, and Acts. We have no idea what Paul possessed in regards to records of the teachings of Christ, whom by all accounts he never met – a couple of episodes ago we discussed the possibility of a sayings book that was used in the production of the Synoptic Gospels Matthew and Luke, but the evidence for such a document remains conjectural. While Acts presents us with a wealth of information about Paul and his life, Acts was likely undertaken at least two decades after Paul’s death in the mid-60s, and so the Pauline Epistles have the distinction of being the earliest documents produced by the Christian world, and maybe the most reliable documents on what was actually happening in Christianity during its first couple of decades.

Looking at maps of Paul’s missionary journeys might be the quickest way to understand the context of the Pauline epistles. The Eastern Mediterranean between 50 and 65 CE was a slurry of cultures – Greek, Roman, Persian, Egyptian, and dozens of others – all, having assimilated to varying degrees (and in some cases scarcely at all) to Julio-Claudian rule.

The Pauline Epistles offer snapshots of Paul working to stabilize and standardize the earliest Christian communities of the Eastern Mediterranean. Let’s talk for a moment about the circumstances about some of the Pauline Epistles, just to give you a sense that at their inception these were often documents written to answer the needs of specific communities and historical situations. First and Second Corinthians, written to the Christian community of the bustling Greco-Roman metropolis of Corinth, show that Paul preached in and out of synagogues, winning converts from all walks of life. When the Corinthian Christian community fell under the spell of another religious leader – an Alexandrine Jew schooled in philosophy and rhetoric, appropriately named Apollos, Paul was ready with Christian arguments as well as easy familiarity with stoic philosophy, Corinth’s athletic Games, and a famous differentiation between Christian and pagan love. Against the Platonic doctrine of desirous sexual love, or eros, set out in the Symposium, Paul writes about agape, that Greek word used in the Bible for the exalted love between man and God, writing the famous verses “Love is patient; love is kind; love is not envious or boastful or arrogant or rude. It does not insist on its own way; it is not irritable or resentful; it does not rejoice in wrongdoing, but rejoices in truth” (1 Cor 13:4-6). The fact that Paul could write such a lyrical passage to arbitrate a leadership squabble that later became a standard part of Christian wedding vows, not to mention countless modern tattoos and wall plaques, is only one small testament to his ability to create striking rhetoric out of what was in his time the newborn and scarcely systematized doctrines of Christianity.

Other Pauline epistles, while they seem like carefully deliberated essays addressing universal Christian themes, were also written to meet the demands of precise places and times. The Book of Romans, while of course it has plenty to say on Christian theology, also seeks to ease tensions between Gentile and Jewish Christians in Rome (11:13-36), and to dissuade Roman Jews from civic uprisings that might result in violent clampdowns (13:1-7). The Book of Philippians, an affectionate letter to one of Paul’s dearest church communities in Northern Greece, speaks of a man named Epaphroditus, who has just visited Paul in prison and brought him gifts either in the Judean city of Caesarea or in Rome itself. The Book of Philemon, a book whose inclusion in the New Testament at all is a matter of some curiosity, asks its addressee to grant a favor to a slave who has been useful to the imprisoned Paul, and has converted to Christianity. So in short, unlike the narratives of the Gospels and Acts, parts of the Pauline Epistles are improvised to meet the circumstances that occasioned them, and often rather than making Paul’s letters seem like incidental documents tossed into the Bible, the improvised quality of his epistles give the New Testament’s reader the exciting sense of seeing Christianity being born in the Eastern Mediterranean during the reigns of the Roman emperors Claudius and Nero.

Not all of the Pauline Epistles demonstrate evidence of such specific addressees and historical situations. The more general Ephesians may have been circulated and recirculated in variant forms, and as a whole, the collection of Pauline letters that we have might be a distillation of some of his best theological work, partly redacted and compiled by Paul himself. But along the way, other editors and compilers were involved, because out of the fourteen Pauline epistles, only seven today are generally recognized as demonstrating the consistency of compositional quality and theological interests we now associate with Paul. These are Romans, First and Second Corinthians, Galatians, Philippians, First Thessalonians, and Philemon. Two more, Colossians and Second Thessalonians, are today debated as to whether or not they actually come from Paul. And five more are thought not to have been composed by Paul – these are Ephesians, Hebrews, First and Second Timothy, and Titus.2 That’s a lot of names, I realize, so let’s consider the Pauline Epistles by numbers. There are 100 chapters in the 14 Pauline Epistles. A majority of these chapters – 61, are attributed to Paul with some certainty. Seven more chapters are of questionable authorship. And the remaining 32 chapters are most likely from other, later sources. The gist of this analysis is that even though over 30% of the Pauline Epistles are probably later, pseudepigraphal contributions to the Bible, enough of the collection is Paul himself that we can still call the set “Pauline” and be relatively accurate. So let’s talk for a moment about our main guy for today. [music]

Paul and the Context of the Pauline Epistles

The personality of Christianity’s most famous missionary suffuses the 14 Pauline Epistles. Near the beginning of the collection Paul proclaims himself “a debtor both to Greeks and to barbarians, both to the wise and to the foolish” (Rom 1:14). The verse acknowledges that Paul thinks of his theological work as syncretic, making use not only of Christ’s teachings and ancient Jewish traditions, but also the abundant philosophical ideas and cultural practices of the pagan world. It also acknowledges that Paul didn’t think of himself as infallible. Four of the Pauline Epistles are prison letters – these are Ephesians, Philippians, Colossians and Philemon, and in his days spent on lockdown, after he’d settled in, and his followers had heard news of their leader’s various incarcerations, Paul had plenty of time during his later career to contemplate how things might have gone differently at various junctures. At the same time, though, in his darkest moments, his memories of the challenges that he had faced seem to have brought him strength, and confidence. In 2 Corinthians, frustrated with the fickleness of the young Christian community he’d helped establish there in Corinth, Paul singles himself out as a singularly qualified minister of Christ’s teachings. Paul writes, in the New Oxford Annotated Bible,But whatever anyone dares to boast of—I am speaking as a fool—I also dare to boast of that. Are they Hebrews? So am I. Are they Israelites? So am I. Are they descendants of Abraham? So am I. Are they ministers of Christ? I am talking like a madman—I am a better one: with far greater labors, far more imprisonments, with countless floggings. . .often near death. Five times I have received from the Jews the forty lashes minus one. Three times I was beaten with rods. Once I received a stoning. Three times I was shipwrecked; for a night and a day I was adrift at sea; on frequent journeys, in danger from rivers, danger from bandits, danger from my own people, danger from Gentiles, danger in the city, danger in the wilderness, danger at sea, danger from false brothers and sisters; in toil and hardship, through many a sleepless night, hungry and thirsty, often without food, cold and naked. And, besides other things, I am under daily pressure because of my anxiety for all the churches. Who is weak, and I am not weak? Who is made to stumble, and I am not indignant? (2 Cor 11:21-9)

The rhetoric establishing what we might call Paul’s “street cred” is colorful here – Paul’s self depiction of himself as starving, cold, and naked may take some poetic license. But the final, punchy questions, “Who is weak, and I am not weak? Who is made to stumble, and I am not indignant?” – these questions show that Paul felt accountable to the actions of his various satellite Christian communities, and that amidst a variety of persecutions and environmental hazards endemic to an ancient traveling minister, he carried an exhausting burden on his shoulders.

Andrea Vanni’s St Paul (1390). Paul is often depicted with a sword in Catholic art, due to two reasons – first, the martial language in passages in Ephesians 6:11-12, 6.:17 and Hebrews 4:12. Second, Paul was purportedly beheaded (in the Apocryphal Acts of Paul and Thecla) on Nero’s orders in Rome, though miracles that occurred during his final moments did much to convince the Roman Emperor of the verity of Paul’s faith.

Evidence from his own letters indicates that Paul was somewhat of a maverick, operating for the most part outside the main circle of earliest Christianity and relating only awkwardly to its original leaders. He may well have represented the wave of the future: since the middle of the second century those characteristic elements that it took all his formidable resources to establish and defend – full and equal membership for Gentile believers, no obligation to adhere to the law of Moses, and so on – have simply been taken for granted as basic elements of the Christian faith. But the very success of Gentile Christianity can serve to obscure the degree to which Paul’s mission represented radical innovation in its own day.4

The Pauline epistles, then, invite us to ponder the astounding possibility that the first phase of Christianity’s expansion and geographical transmission hung on the shoulders of one strange, iconoclastic, doctrinally idiosyncratic person who, in spite of imprisonments, corporal punishments, shipwrecks, and perilous journeys, just kept going, and going, and going. The Gospels, once again written after the Pauline Epistles, were produced by individuals in church communities that had in some cases been founded and guided by Paul himself, and in all cases, likely felt his influence in some way or another.

Paul’s authorship looms large over many of the Pauline Epistles. And while determining the exact authorship of all of the 14 Pauline epistles is a piece of unfinished business, so, too is the analysis of their theological contents – a project of interpretation 2,000 years in the making that shows no signs of slowing down. In the remainder of this program, I want to look at the Pauline Epistles in detail, although we won’t go through all 14 of them one at a time. Being a letter collection, this section of the New Testament is naturally repetitious in nature, the chronologically out of order epistles often making the same points and theological arguments at different junctures – I should note that they are organized based on length, from longest to shortest, in the New Testament. Anyway, rather than going straight through from Romans to Philemon, we’re going to divide the remainder of this episode into two major portions. The first, briefer section, will show the letters attributed to Paul outlining the architecture of a Christian community and identifying patterns of behavior that are acceptably Christian. While Paul is hardly interested in blasting out a rules list like the one in the Pentateuch, the Pauline Epistles do have some general directives for self conduct and community organization.

Once we get a sense of the overall ethical and social engineering Paul has in mind for the first Christian communities, we’ll dive into the heart of the Pauline Epistles, and that is his theological writings on salvation. From Augustine to Martin Luther and beyond, some extremely influential theologians have thrown themselves into the Pauline Epistles and found some very different ideas about the mechanics of salvation – whether it comes from free will and conscious ethical decisions, whether it comes from mere faith in Jesus Christ, whether it’s predetermined, whether it’s collective and corporeal, or individual or incorporeal, or some combination of the these. It was Paul’s task as the self-proclaimed “apostle to the Gentiles” to decide what to do with the Pentateuch’s sizable rules list, and what he did with these rules was instrumental to the conversion of the earliest Gentiles, and later, had far reaching consequences in the history of Christianity. The split between Catholicism and Protestantism has at its epicenter a mere dozen or two verses in the Pauline Epistles, most often in the Book of Romans, and while the magnitude and implications of this division are vast, understanding where, say, Augustine and Luther read Paul differently is pretty simple.

So let’s begin by discussing those portions of the 100 chapters of the Pauline Epistles that have to do with community structuring and self conduct. While Paul, once again, is indisposed to drafting a brand new rules list, once in a while he does set down instructions for what you can and can’t do in the tiny world of early Christianity. These regulations, housed as they are in the New Testament, haven’t exactly fallen by the wayside of theological history.

Ethical Regulations in the Pauline Epistles

1 Thessalonians, the earliest document to survive from Christianity, is a warm letter sent from Paul to the Christian community of Thessalonica in the Roman province of Macedonia, some time around 50-51 CE.5 We don’t know the demographics or size of this community. Scholar Philip Esler notes that “Recent research on the social structure of Pauline communities has tended to favour socially stratified congregations with wealthy members providing a house for the meetings of the community and virtually acting as patrons to the members.”6 Addressed, then, to an assortment of mostly Gentile converts in the northwestern Aegean, 1 Thessalonians makes it clear that key converts of Paul’s ministry clung fast to Christianity in spite of the risk of doing so. Some of the first lines of Christianity’s first surviving document show Paul marveling at the newly faithful – he writes, “you became imitators of us and of the Lord, for in spite of persecution you received the word with joy inspired by the Holy Spirit” (1 Thess 1:6-7). We learn in this book of the New Testament that Paul himself hadn’t had an easy time up until coming to Thessalonica – the city’s northeastern neighbor Philippi had initially been unkind to him. Paul writes, “You yourselves know, brothers and sisters, that our coming to you was not in vain, but though we had already suffered and been shamefully mistreated at Philippi, as you know, we had courage in our God. . .in spite of great opposition” (1 Thess 2:2). The letter’s audience is explicitly the formerly pagan converts of Thessalonica, as Paul makes clear a moment later: “For you, brothers and sisters, became imitators of the churches of God in Christ Jesus that are in Judea, for you suffered the same things from your own compatriots as they did from the Jews” (1 Thess 2:14). These three passages, from the outset of 1 Thessalonians, teach us some immediately important lessons about the Pauline Epistles.

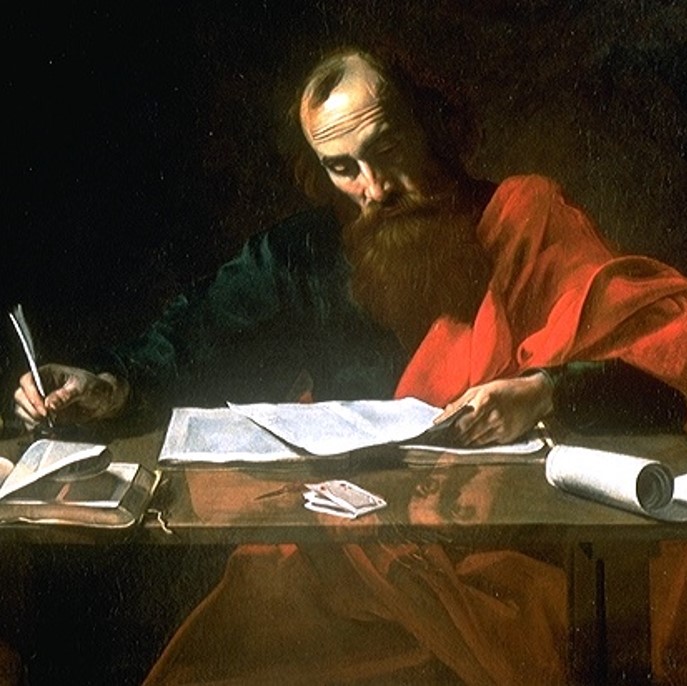

Guercino’s Saint Paul (sixteenth century). While Paul’s conversion on the Damascus Road has been a popular image for artists, along with the apostle standing with a sword, a number of painters chose to show the theologian at work reading and writing the Pauline Epistles, portraying Paul as a thinker and even poet just as much as a saint.

Paul, though once again not keen on setting up a huge new rules list, still peppers his letters with dos and don’ts from time to time. Paul writes in Romans, “Let every person be subject to the governing authorities; for there is no authority except from God, and those authorities that exist have been instituted by God” (Rom 13.1). Though this morsel of advice had a specific historical incentive – preventing the Roman Jews of the 50s CE from a possibly disastrous uprising – it is consonant with Christ’s teachings in the Gospels.8 Jesus, in Matthew, Mark, and Luke, advises, “Give. . .to the emperor the things that are the emperor’s, and to God the things that are God’s” (Matt 22:21, Mark 12:17, Luke 20:26), and in both of these cases, the New Testament recommends keeping one’s head down beneath the might of Rome’s officials.

So, what we’ve covered so far is fairly obvious stuff. Christianity emerged into a dynamic world that was at best indifferent toward the new religion, and Christ and Paul alike cautioned their flocks to stay in line, since so many Roman wolves raged beyond the sheepfolds. To move us toward some of the subtler aspects of the Pauline Epistles, we need to recollect some basic facts about Paul. Paul, once called Saul, was the son of a tentmaker, born in the southern Anatolian city of Tarsus in a very religious Jewish community. Earlier, in 2 Corinthians, we heard the extent to which Paul identified as a Jew even when ministering to Gentiles – he tells them in this letter that he is a Hebrew, an Israelite, and a son of Abraham. Paul reminds an assembly of hostile Jews in Jerusalem in the Book of Acts, perhaps with anger and emotion in his voice, speaking Hebrew, that in spite of all of his work with Gentiles, that he has nonetheless been “educated strictly according to our ancestral law, being zealous for God, just as all of you are today. I persecuted [Christians] up to the point of death by binding both men and women and putting them in prison” (Acts 22:3-4).

Readers of the New Testament are generally familiar with these aspects of Paul’s background, and there’s little mystery about it. To get a little deeper into the theology of the Pauline epistles, we need to consider the following – what we might call conundrum at the heart of Paul’s thinking. Simply put, though Paul was ready to allow Gentile converts to set aside the hundreds of law codes in the Old Testament, Paul’s background as a Pharisee – that especially scrupulous and legalistic sect of Second Temple Judaism – Paul’s background sometimes blinded him to the fact that Gentile converts needed at least some kind of regulatory ethical framework, lest they create very divergent strands of Christianity and populations that looked nothing like the initial Jewish Christians of the Apostolic generation. In other words, Paul, in passages we’ll soon look at, dismisses Jewish law codes again and again, telling his Gentile converts that they don’t need to be circumcised, or follow dietary regulations, or sacrifice anything. But he seems to forget that a total lack of regulations might well encourage Gentile converts to practice something like a pagan Christianity – believing in salvation through Jesus Christ but at the same time sacrificing to other gods and honoring their holidays, engaging in bisexual practices, caring naught for marital fidelity, wrestling nude in public gymnasiums, and in all other ways looking nothing like the Jewish Christian community that Paul had envisioned without really realizing the extent of his own Jewish cultural assumptions. As scholar Craig Hill puts it, “In practice, what Paul expects of his converts is a fairly typical Jewish morality, which he can assume for himself but which comes less naturally to his Gentile associates. Consequently, Paul is put in the awkward position of legislating rules of behavior ad hoc, since he no longer has the law to draw on for authorization. Therefore, he is forced, in effect, to reinstitute Jewish laws with Christian warrants.”9

The question of which broadly Jewish cultural practices made the jump from the Old to the New Testament is a fascinating one. With the exception of a few passages of the Gospels here and there, especially in the Book of Matthew, the Bible’s four stories of Jesus’ life depict him as pretty relaxed about the 613 Commandments of the Pentateuch. Memorably, at two junctures in the Gospels, Jesus tells his disciples that you most of all needed to love god and honor your neighbor (Matt 22:37-9, Mark 12:29-31), and that the rest of it is just a bunch of details. Following, perhaps, Christ’s nonchalant attitude toward Mosaic Law, from time to time Paul tries the same approach. In parallel to some of Christ’s statements in the Gospels, Paul writes in Galatians “For you were called to freedom, brothers and sisters; only do not use your freedom as an opportunity for self-indulgence, but through love become slaves to one another. For the whole law is summed up in a single commandment, ‘You shall love your neighbor as yourself’” (Gal 5.13-14).10 You don’t need to do the Sabbath thing, Paul tells the recipients of Galatians, or all the sacrifices and meat cutting, or eat this thing and not that other thing – that’s not what it’s about. You just have to have a warm and openhearted attitude toward your fellow human beings, and faith in Jesus Christ. It’s a nice doctrine – both in Christ’s words in the Gospels and Paul’s in Galatians. But it seems to have been problematically vague, because elsewhere, we find Paul being a bit more deliberate and clear about what his Gentile converts actually needed to do. [music]

Jewish Cultural Norms and Greco-Roman Society

Paul’s directives – his orders for self conduct – are scattered miscellaneously throughout the epistles attributed to him, but let’s look at a few of them. In 1 Corinthians, Paul entertains a hypothetical conversation between a Gentile convert and himself. The convert in this dialogue seems to take the position that Paul’s indifference toward law codes meant that anything was permissible, whereas Paul gently chastens him, fastening on some additional moral advice. This short dialogue begins with the pagan convert saying, “All things are lawful for me.” Paul replies “[B]ut not all things are beneficial.” And the former pagan again, “All things are lawful for me.” And Paul, “[B]ut I will not be dominated by anything.” The pagan, “Food is meant for the stomach and the stomach for food.” And Paul, “[A]nd God will destroy both one and the other. The body is not meant for fornication but for the Lord, and the Lord for the body” (1 Cor 6:12-3). In the short exchange, we see something happening that happens everywhere in the Pauline Epistles, and must have happened often in Paul’s career. Pauline Christianity’s official message was that the unwieldy law codes of the Torah were obsolete. But in reality, Paul had all sorts of tacit assumptions about self conduct – assumptions that bore the stamp of Jewish culture and that he slipped into the theology of the writings he left behind.One of these assumptions was the continued subservience of women. 1 Corinthians states that “As in all the churches of the saints, women should be silent in the churches. For they are not permitted to speak, but should be subordinate, as the law also says. If there is anything they desire to know, let them ask their husbands at home. For it is shameful for a woman to speak in church” (1 Cor 14.33-5). Three of the Pauline Epistles that are most likely erroneously attributed to Paul also make it clear that women ought not be outspoken leaders in the incipient Christian world. Ephesians states “Wives, be subject to your husbands as you are to the Lord. For the husband is the head of the wife just as Christ is the head of the church, the body of which he is the Savior. Just as the church is subject to Christ, so also wives ought to be, in everything, to their husbands” (Eph 5.22-24). The Book of Colossians, similarly, advises, “Wives, be subject to your husbands, as is fitting in the Lord” (Col 4:18). And a final pseudepigraphal Pauline letter follows along these lines. First Timothy proclaims, “Let a woman learn in silence with full submission. I permit no woman to teach or to have authority over a man; she is to keep silent. For Adam was formed first, then Eve; and Adam was not deceived, but the woman was deceived and became a transgressor. Yet she will be saved through childbearing, provided they continue in faith and love and holiness, with modesty” (1 Tim 2.11-15). Not all of these quotes, again, are definitely Paul, pure and simple, but collectively, they demonstrate that Paul and his colleagues were trying to replicate a system of monogamous marriages, sexual morality, and gender hierarchy that reflected the traditional Jewish practices of their homeland – a system not necessarily present in the urban centers of Anatolia and the Aegean coast.

John William Waterhouse’s Hylas and the Nymphs (1896). Heracles’ lover Hylas is abducted by water-nymphs toward the end of Book 1 of Apollonius’ Argonautica. The Pauline epistles, whose Jewish cultural values were set against those that pervaded the Mediterranean world, occasionally disparage extramarital and homosexual behavior.

To return to Paul and the rules he sets out in his Epistles, the social position of women, and the matter of who ought to have sex with whom, and what sort of sex is authorized, are all issues that Paul works to legislate to his readers. Another issue has to do with sacrifice. Throughout his letters, as we’ll soon see in a bit more detail, Paul assures his Gentile converts that they don’t have to worry about all of the sacrifice laws printed in Leviticus, Numbers, and Deuteronomy. What he neglected to make clear to at least one nascent Christian community was that they really needed to stop sacrificing to their pagan gods. Now, it’s kind of funny to think that after converting to Christianity, a zealous young pagan follower of Jesus might continue to make burnt offerings to Zeus and Apollo, but, these were polytheists, and Paul’s intractable followers in Corinth, at least, seemed to do just this. Paul writes in 1 Corinthians, I imagine with some incredulity in his epistolary voice, “I imply that what pagans sacrifice, they sacrifice to demons and not to God. I do not want you to be partners with demons. You cannot drink the cup of the Lord and the cup of demons. You cannot partake of the table of the Lord and the table of demons” (1 Cor 10:20-1). In other words, come on, folks, you’re Christians now, please stop those pagan sacrifices.

Perhaps a more learned subgroup of Paul’s Gentile converts weren’t so much drawn to continued polytheistic sacrifices as they were Greco-Roman intellectualism. This intellectualism, though Paul was no stranger to it, was also something he saw as a potential threat to the first tiny Christian communities. Paul’s letter to the Colossians warns, “See to it that no one takes you captive through philosophy and empty deceit, according to human tradition, according to the elemental spirits of the universe, and not according to Christ” (Col 2:8). 1 Timothy follows along these lines, advising, “Avoid the profane chatter and contradictions of what is falsely called knowledge; by professing it some have missed the mark as regards the faith” (1 Tim 6:20-1).11 Don’t go frittering away your time with pagan intellectuals at symposiums and agoras, the Pauline Epistles tell us, and don’t mistake cleverness for truth. And while Paul certainly didn’t want to lose any fresh converts to Plato or Aristotle, there are wide swathes of the Pauline letters that reflect ideas prevalent in contemporary Greek philosophy. So now that we have a sense of some of the baseline regulations that Paul sets out in his letters, and how many of these regulations aim to require some baseline Jewish rules on new Gentile Christian communities, let’s change gears for a moment. As much of Paul’s ideology was, naturally, based on his upbringing as a Jewish Pharisee, some of it seems to have been formed by being a Greek-speaking citizen of the Roman Empire. He may have warned the Colossians against a naturalistic view of the universe divorced from God. But a lot of Paul’s ideology, nonetheless, sounds like a fairly familiar mixture of stoicism and Platonism. Let’s talk about some of the distinctly Greek elements of the Greek language Pauline epistles. [music]

Mind-Body Dualism in the Pauline Epistles

A number of episodes ago we traced out the parallels between stoicism – especially Senecan stoicism – and Pauline ideology in the New Testament. A very old tendency in pagan theology and philosophy – one that began with Orphism and then Pythagoreanism, then later Socrates and Plato, and then later movements in the 300s and 200s BCE like Cynicism and Stoicism, preached a dualism between mind and body. In this conceptual framework, as you likely know, the mind is capable of weighing lofty, timeless matters and through will and meditation, insulating itself from the ups and downs of daily life. And the body is a fleshy encumbrance, its needs and passions a distraction from the loftier world of the mind. Christianity, through Paul himself, enthusiastically embraced mind-body dualism.

Raphael’s depiction of Pythagoras in The School of Athens (1509). Beginning in the sixth century BCE, we begin to have records of Mediterranean cult religions and philosophical movements emphasizing the existence of immortal souls, and how tempering one’s physical appetites through diet and cleanliness can lead to a better posthumous existence. Plato, and after him many major Greek philosophical movements followed this tradition, as did Christianity via the Pauline Epistles, although the Hebrew Bible, produced in a separate lineage, does not.

The New Testament, more broadly, takes this philosophical dichotomy between body and mind seriously. In one of the most heartbreaking scenes in the Gospels, as Christ awaits his execution in Gethsemane, agonized and unable to sleep, he laments in Matthew and Mark that “the spirit indeed is willing, but the flesh is weak” (Matt 26:42, Mark 14:38). When spoken by Jesus, this famous phrase is perhaps meant to contrast the dualism of Christ’s own unique, half-divine, half-human composition. But Paul, and after him Augustine, and many more in Christian theological history followed suit, and envisioned, like so many Greco-Roman thinkers had before them, that their snowy white spirits had, regrettably, been stuffed into fleshy lodgings. Extreme versions of mind-body dualism, as we’ll soon see, turned into full fledged Christian splinter groups – Gnosticism and Manichaeism. For now, though, let’s stick with Paul – and the canonical Christian ideas on mind and body.

In 1 Thessalonians, Paul lays out some standard stoic censures against the pleasures of the flesh. He writes, “For this is the will of God, your sanctification: that you abstain from fornication; that each one of you know how to control your own body in holiness and honor, not with lustful passion, like [those] who do not know God” (1 Thess 4.3-5). Along the same lines, in 1 Corinthians, Paul writes, “Shun fornication! Every sin that a person commits is outside the body; but the fornicator sins against the body itself” (1 Cor 6:18). With fornication being such an anathema, by extension, the Christian convert does best to not be married. Paul writes, “he who marries his fiancée does well; and he who refrains from marriage will do better” (1 Cor 7.38).

The aversion to sexual intercourse shown here, together with the general mind-body dualism scattered through Paul’s epistles, are familiar material, and certainly come up in Apocryphal Acts literature like the Acts of Paul and Thecla. But what we’ve considered thus far in this episode still leaves us with some big questions about Pauline theology. We’ve explored how he sets up some basic regulations for Gentile converts. And we’ve considered how these regulations were motivated by some combination of Jewish cultural norms and the sorts of Greek Platonic and stoic ideas that Paul’s contemporaries like Seneca were setting down in the same timeframe. What we haven’t done yet, and this is a whopper of a task, is to consider the cardinal issue that Paul may have spent his entire life trying to answer. This was the issue of how Christians were to be saved, and what, exactly, salvation was. [music]

The Apostolic Conundrum: Gentiles and Mosaic Law

When Paul wrote his epistles, he knew that for centuries, Jews had a clear theological path to follow – a path that had been outlined in the Pentateuch. They were to follow the laws of Moses and uphold their covenant with Yahweh, and eventually, according to various prophecies in books like Isaiah, Jeremiah, Daniel, Joel, and Habakkuk, the Jews would see much better days on earth.12 For Gentile converts, though – those not given the mandate to follow Mosaic Law, a different path toward salvation had to be set out. It would not, by and large, include the 613 commandments of the Pentateuch.Throughout the Pauline Epistles, Paul disabuses his readers of the notion that they need to honor the Pentateuch’s sizable rules lists. And while Paul spends a great deal of time in his extant writings defining what Christians might do to be saved, he also spends a lot of time elaborating on what Christians don’t need to do in order to be saved. In the Book of Galatians, whose main purpose is a discussion of Gentiles and Mosaic Law, Paul writes that “the whole law is summed up in a single commandment, ‘You shall love your neighbor as yourself’” (Gal 5:13-14). This is a core notion in the New Testament – it also comes up in two of the Gospels (Matt 22:37-9, Mark 12:29-31), in Romans (13:8-10). In the latter book, Paul draws a portrait of Jewish practitioners of Mosaic Law following the directives of their holy book without having faith themselves. The issue of Mosaic Law comes up early in the Book of Romans, with a long rhetorical question to a hypothetical Jewish person:

But if you call yourself a Jew and rely on the law and boast of your relation to God and know his will and determine what is best because you are instructed in the law, and if you are sure that you are a guide to the blind, a light to those who are in darkness, a corrector of the foolish, a teacher of children, having in the law the embodiment of knowledge and truth, you, then, that teach others, will you not teach yourself?” (Rom 2:17-21).

As to what the addressee of the question ought to teach himself, the answer is that following rules lists is no substitute for having true spiritual faith. Another famous Pauline verse, in 2 Corinthians, states that God “has made us competent to be ministers of a new covenant, not of letter but of spirit; for the letter kills, but the spirit gives it life” (2 Cor 3.6). In this case, the letter is legalism and formulaic liturgy – but the spirit is passionate, honest religious conviction. Spiritual faith, Paul writes in Galatians, has replaced the disciplined legalism of the Pentateuch. In Galatians, Paul argues that “now that faith has come, we are no longer subject to a disciplinarian, for in Christ. . .you are all children of God through faith” (Gal 3.25-6). Now that was a flurry of quotes, but they all add up to similar conclusions – the Law of Moses, when followed for its own sake, Paul seemed to believe, can be an ossified routine exercise, and what’s really important is genuine faith and spiritual conviction.

Paul’s point in these passages may have been that when you do something many times by force of habit you can forget the sometimes profound motivations that drove you toward it in the first place, and that this can occur at a cultural level, as well. He directs his readers, then, toward a more active, mindful spirituality than one of inherited customs and ceremonies. And sometimes, maybe due to an ardent desire to welcome uninitiated pagans off the Roman street and into Christianity, Paul can be especially dismissive toward the regulatory legacy of Judaism. This dismissiveness sometimes causes him to make striking statements – statements out of step with the mainline Jewish Christianity of the Apostolic generation. In Galatians, he writes, “Listen! I, Paul, am telling you that if you let yourself be circumcised, Christ will be of no benefit to you. Once again I testify to every man who lets himself be circumcised that he is obliged to obey the entire law” (Gal 5.1-4). It is possible that Paul had undergone such a turnabout from his long held Jewish beliefs that he no longer thought anyone should be circumcised for any reason, and we’ll talk about this a bit more later. To stick more closely for the moment to the subject of the anti-legalist ideology in the Pauline Epistles, let’s look at a few more of the Pauline passages on this same subject that are of questionable authorship.

The Book of Hebrews is very clear on the subject of animal sacrifice – it’s no longer necessary after Christ, so cut it out. Hebrews says that Jesus “has no need to offer sacrifices day after day, first for his own sins, and then for those of the people; this he did once for all when he offered himself. . . he entered once and for all into the Holy Place, not with the blood of goats and calves, but with his own blood, thus obtaining eternal redemption” (Hebrews 7:27, 9:12). Along these same lines, the Book of Colossians announces that Christians don’t need to bother about Jewish food and festival laws, stating, “do not let anyone condemn you in matters of food and drink or of observing festivals, new moons, or Sabbaths. These are only a shadow of what is to come, but the substance belongs to Christ” (Col 2.16-17). Laws, in the lines of these pseudepigraphal Pauline letters, were not only a distraction from the awesome power of Christ – they were also asinine. The Book of Titus advises its audience to “avoid stupid controversies, genealogies, dissentions, and quarrels about the law, for they are unprofitable and worthless” (Titus 3.9). The same book warns against “paying attention to Jewish myths or to commandments of those who reject the truth. To the pure all things are pure, but to the corrupt and unbelieving nothing is pure” (Titus 1.13-15).

Throughout the Pauline Epistles, then, both those considered genuine and those considered spurious, Christ’s coming has been the central historical event of the cosmos, upending all of Earth’s religious practices, including Judaism’s. To Paul, the longstanding ethical framework of the Pentateuch was now defunct – those who had a relationship with the one true God were no longer a single ethnicity with a single covenant, but instead the whole earth. And while various practices might persist, and while a blended Jewish Christianity had been born that would persist for centuries, Mosaic Law, according to what would soon be the New Testament, had been replaced by something else. [music]

The First Two Types of Pauline Salvation: Good Works and Faith

At the very heart of the Pauline Epistles, once one has dealt with the complex matter of their attitude toward the Mosaic Law, is the related subject of salvation. With the Pentateuch’s rules out of the picture – with animal sacrifice, and cleanliness regulations, and civic conduct rules all swept off the table, Paul still had to tell his new converts what it was that they needed to do. And what he wrote on this subject engendered some of the core parts of Christian theology – ideas still central to the basic structure of the religion’s many variants today – original sin, predestination, salvation by good works and salvation by faith, and Christian apocalypticism, to name just a few. Above all of these in importance is probably the issue of how salvation operates, a subject to which we can now turn our full attention.When we are young, perhaps, in countries with Christian and Islamic heritage, we learn that if we’re good, we go to heaven, and that if we’re bad, we go to hell. Zoroastrians, seated in modern day Iraq and Iran, taught a version of this as well, as had Ancient Egyptians since the Middle Bronze Age. For the entire duration that the Bible and Qur’an were being written, individual salvation and damnation, which Plato also develops a version of at the close of the Republic – individual salvation and damnation were out there. And for a lot of us, this is salvation in a nutshell. Flocks of theologians might draw some lace around the edges, but the notion that good behavior leads to heaven, and bad to hell is really what it says in the Bible. Right? No, actually. Not really. Not in the verses of the New Testament, at least.

Christianity has a complicated relationship with the notion that good behavior, or to use Christian terminology, good works, are the keys to God’s favor. At the roots of this complex relationship are Paul’s own writings about the Law of Moses in the Pentateuch. Most notably, in the Book of Galatians, Paul goes so far as to say that if following the Law alone and doing good works were sufficient, we wouldn’t have needed the sacrifice of Jesus Christ. Specifically, Paul writes, “[W]e have come to believe in Christ Jesus, so that we might be justified by faith in Christ, and not by doing the works of the law, because no one will be justified by works of the law. . .for if justification comes through the law, then Christ died for nothing” (Gal 14-15,21). The statement is pretty striking, but still pretty straightforward. If all we need is free will and a clear rules list, then salvation is a fairly simple piece of machinery that requires neither a compassionate deity at the top nor a genuine devotee at the bottom – merely the mechanistic protocol of rules and adherents.13

Some passages of the New Testament, then, are skeptical about the notion of good works leading to salvation. Other passages, though, give a thumbs up to good works. In Romans, Paul writes, “For [God] will repay according to each one’s deeds: to those who by patiently doing good seek for glory and honor and immortality, he will give eternal life; while for those who are self-seeking and who obey not the truth but wickedness, there will be wrath and fury” (Rom 2.6-8). The Book of Revelation describes salvation working by similar mechanics, its narrator, relating a vision of the afterlife, telling us, “And I saw the dead, great and small, standing before the throne, and books were opened. Also another book was opened, the book of life. And the dead were judged according to their works, as recorded in the books” (Rev 20:12). These passages confirm what we’re told when we’re young – you are judged based on an assessment of the amassed actions you’ve taken during your life. The situation is the same in the Bronze Age Egyptian Book of the Dead, in which the heart of the deceased is weighed against the feather of ma’at, and the same as in the Middle Persian Zoroastrian Viraf, in which a believer’s actions are evaluated on the Chinvat Bridge, and he is saved or damned based on his deeds.

Pelagius (c. 358 – c.418) had a more sanguine view of humankind than Christianity embraced after Augustine. Pelagius, adopting a more Platonic view, believed we were not sullied by original sin, and the exercise of will and reason would lead to good works and through them salvation. Augustine, whose view of humanity was not so positive, saw to it that Pelagius was excommunicated and condemned in 416.

For various reasons, then, passages of the Pauline Epistles that have to do with salvation do not clear a path for the doctrine of salvation by good works. To Paul as well as Augustine, if you had a clear rules book, you could simply keep a tight watch on your own self conduct without ever thinking much about God or the sacrifice of Christ – if you had rules to follow, you were all set to do it on your own. And about eleven hundred years after Pelagius’ teachings were condemned, an institutionally grounded form of Pelagianism had gained control over European theology, replacing good works with its own purchasable catalog of virtues, and mediating the relationship between Christ and believers with a thick layer of clerical functionaries. This, of course, was one of the more ignoble periods of the Catholic Church’s history, when the selling of indulgences had angered and alienated an energized grassroots of European Christians who would go on to begin the Protestant Reformation.

The theologian Martin Luther, who lived from 1483-1546, was one of the most important individuals to ever read the Pauline Epistles. And his take on them, and in some cases the way that he translated them, is that they do not at all support the notion of salvation through good works. So we’ve talked about how the Pauline Epistles are very iffy on the value of good works. Let’s look at some of the passages in the Pauline Epistles that contradict the notion of salvation through good works and introduce a different doctrine. This second doctrine is, as mentioned earlier, that salvation doesn’t come from anything other than faith, or, to use Martin Luther’s term sola fide, “by faith alone.” Here’s Paul, in the third chapter of Romans, in what is arguably the most influential passage in the entire New Testament outside the Gospels – this is once again the New Oxford Annotated Bible, NRSV translation.

But now, apart from law, the righteousness of God has been disclosed. . .For there is no distinction, since all have sinned and fall short of the glory of God; they are now justified by his grace as a gift, through the redemption that is in Christ. . .whom God put forward as a sacrifice of atonement by his blood, effective through faith. [God] did this to show his righteousness, because in his divine forbearance he had passed over the sins previously committed; it was to prove at the present time that he himself is righteous and that he justifies the one who has faith in Jesus. Then what becomes of boasting? It is excluded. By what law? By that of works? No, but by the law of faith. For we hold that a person is justified by faith apart from works prescribed by the law. (Rom 3.21-28)

Let’s hear that last line one more time. “For we hold that a person is justified by faith apart from works prescribed by the law.” Now, Martin Luther loved this line so much that he took the liberty of mistranslating it. He wrote – and I’m going to use a recording, because I don’t speak German – “So halten wir nun dafür, daß der Mensch gerecht werde ohne des Gesetzes Werke, allein durch den Glauben.”14 Or, in English, to the original line, “For we hold that a person is justified by faith apart from works prescribed by the law,” Luther added the word allein, or “alone,” so that it read, “For we hold that a person is justified by faith alone apart from works prescribed by the law.” Not quite what Paul wrote, but then, Luther was pretty pissed about the selling of indulgences and evidently willing to bend the rules a bit.

Lucas Cranach the Elder’s Martin Luther (1529). Luther’s deliberate mistranslation of Romans 3:28, one of the best known verses in the Pauline epistles, Luther’s’ detailed and highly motivated readings of the Pauline epistles, and more generally his doctrine of sola fide, were instrumental to the birth of Protestantism in the sixteenth century.

However, the doctrine of sola fide – that one must only have faith, while it has been useful to certain junctures of Christian theology, also has some issues. In the Book of Ephesians, an early Christian writer emphasizes that Christ “has abolished the law with its commandments and ordinances, that he might create in himself one new humanity in pace of the two, thus making peace” (Eph 2.15). As with so many moments of the Pauline Epistles, it’s a lovely passage, but one that leaves us with questions. If Christ demolished the commandments, why are the first ten still ubiquitous? In the once again key text of the Book of Romans, Paul writes, “now that you have been freed form sin and enslaved to God, the advantage you get is sanctification. The end is eternal life. For the wages of sin is death, but the free gift of God is eternal life in Christ Jesus our Lord” (Rom 6:22-3). This often quoted passage is as sonorous as it is ambiguous. After all, if sola fide is the doctrine, and genuine faith offers the free gift of eternal salvation, the broad issue of how Christians ought to conduct themselves on earth is left pretty unclear.15 Later epistles in the New Testament only muddied the waters further. The epistle of James, hauntingly, states that “Even the demons believe – and shudder” (Jas 2:19). In other words, demons could have faith in the primacy of the Christian God, so wasn’t something other than that required of the pious believer?

This is a pretty important issue in Christian theology, so let me repeat it. If we toss Mosaic Law into the waste bin, and proclaim that all we need for salvation is faith in Christ, then what’s to stop us from adopting radically different worship practices and vastly different ethical systems all called Christianity? This is a whopper of a question, and Paul himself seems to have thought about it during the latter part of his career. Paul writes, once again in Romans, “When Gentiles, who do not possess the law, do instinctively what the law requires, these, though not having the law, are a law to themselves. They show that what the law requires is written on their hearts, to which their own conscience also bears witness” (Rom 2:14-5). In other words, to Paul and other Christian theologians, the process by which one comes to experience genuine faith in Jesus, whether by a miracle or something more mundane, is concomitant with an instinctive understanding of a certain fundamental code of ethics. Put more briefly, the Pelagians held that good works led to salvation. But Paul, toward the end of his career, may have believed that faith made good works – whatever, exactly, good works meant – into a foregone conclusion, and thus faith was the only necessary precursor to salvation. It’s a certainly a dizzying logical leap, but nonetheless a common way to reconcile the rather different doctrines of salvation by faith and salvation by good works.[music]

The Second Two Types of Pauline Salvation: Predestination and Apocalypticism

An anonymous 16th-century Flemish school painting of the theologian John Calvin (1509-64). The French reformer was attracted to passages in the Pauline epistles that supported the doctrine of predestination.

At certain moments in the Pauline Epistles, then, God saves sinners through a process of selecting them ahead of time regardless of what they do on earth. Imagining his readers questioning this controversial doctrine, Paul writes, “who indeed are you, a human being, to argue with God?. . .How unsearchable are his judgments and how inscrutable his ways!” (Rom 9:20,11:33). Paul’s answer to the question of divine injustice here is the same one we find in the Books of Job and 2 Esdras – in a word, God is all-powerful, shut up.

While, as we’ve seen, the Pauline Epistles have passages that can potentially support salvation by good works, salvation by faith alone, and predestination, there is, incredibly, a fourth possibility for salvation in the Pauline Epistles, one that we might call apocalyptic, or general salvation. This fourth type of salvation, while it has always broadly been a part of Christianity, has distinctly Jewish roots. Redemption and deliverance in Judaism do not come at an individual level – the Old Testament does not have doctrines of heaven, hell, and individual salvation. What it does have are prophecies of a coming time of general corporeal resurrection and earthly justice for the Israelites. The Book of Daniel promises that “[A]t that time your people shall be delivered, everyone who is found written in the book” (Dan 12:2). And in Joel, Yahweh promises, to “restore the fortunes of Judah and Jerusalem. . .Judah shall be inhabited forever, and Jerusalem to all generations. I will avenge their blood, and I will not clear the guilty, for the LORD dwells in Zion” (Joel 3:1, 20-1). In this glorious and triumphant moment for the Israelites, spoken of throughout the Old Testament, the Book of Habakkuk proclaims, “the earth will be filled with the knowledge of the glory of the LORD, as the waters cover the sea” (Habb 2:14). And although the Israelites have had a tough time of it, the God in Jeremiah tells us, “I will turn their mourning into joy, I will comfort them, and give them gladness for sorrow. I will give the priests their fill of fatness, and my people shall be satisfied with my bounty” (Jer 31:13-14).

There are quite a few moments in the Old Testament’s Prophetic Books that sound like this. Christians have been most drawn to oracles in Isaiah – Chapters 9, 11, 25, 52 and 53, specifically – that mention a specific messiah, but from end to end the massive expanse of the Prophetic Books much more often foretell a coming period of earthly glory for the descendants of Abraham in covenant with Yahweh. In the centuries that they were written – generally the 600s and 500s BCE, the Prophetic Books’ visions of the future were fueled by the same desire to justify an inglorious present as the Historical Books were. Sure, it appeared on the surface, the Israelites had been conquered by the Egyptians, Syrians, Assyrians, Babylonians, and then ruled over by the Achaemenid Persians, the Greeks, and more. But it was all part of the agenda of their ethnic group’s God, to whom great nations were merely rooks and bishops and knights on the chessboard of fate, spinning around the central node of the Israelites, and who would eventually dash his fist downon the chessboard and elevate the Israelites into a position of superiority forever.

So this ancient doctrine of general salvation, like the 613 commandments, was something Paul had to deal with in the epistles he wrote. Paul intended to grow Christianity far beyond the province of Judea and its satellite communities of diasporic Jews, and so Old Testament prophecies that promised deliverance for the Jews, and only the Jews had to be modified. And so in 1 Corinthians, Paul writes, “I will tell you a mystery! We will not all die, but we will all be changed, in a moment, in the twinkling of an eye, at the last trumpet. For the trumpet will sound, and the dead will be raised imperishable, and we will be changed” (1 Cor 15.51-2). There is no sense here that the resurrection will be of Israelites only, but instead that in a blinding flash, he and the letter’s recipients and all like them will be transmogrified into eternal versions of themselves. Apocalypticism was at the center of Paul’s beliefs and drove his energetic urgency. According to Pauline scholar N.T. Wright, downplaying the apocalypticism of Paul’s ideology is a grave mistake. Scholar N.T. Wright argues that

The Western churches have, by and large, put Paul’s message within a medieval notion that rejected the biblical vision of heaven and earth coming together at last. The Middle Ages changed the focus of attention away from ‘earth’ and toward two radically different ideas instead, ‘heaven’ and ‘hell.’. . .Paul’s. . .gospel was then made to serve this quite different agenda, that is, that believing the gospel was the way to escape all that and ‘go to heaven.’ But that was not Paul’s point.16

Paul’s point was, in his own time, apocalypticism more than personal salvation. Apocalypticism was a common notion in the Ancient Mediterranean and Near East. The Jews had, by the time of Jesus, lived alongside Achaemenid and Parthian Zoroastrians for 500 years. These Zoroastrians, perhaps since the Bronze Age, had believed in a time of increasing decline, a final battle between good and evil, a prophesied son of a virgin called the Saoshyant, and an event called the Frashokereti that would redeem and purify the earth and make humankind immortal.17 Their apocalyptic narrative has a structure similar to the ones in Judaism and Christianity, and we’ll consider Zoroastrianism on its own soon.

But to leave the possibly Zoroastrian roots of the Pauline Epistles, let’s hear Christian apocalypticism as it’s written in the New Testament. The story of the world’s end begins, in 2 Timothy at least, with a general decline. 2 Timothy’s writer predicts, “For the time is coming when people will not put up with the sound doctrine, but having itching ears, they will accumulate for themselves teachers to suit their own desires, and will turn away from listening to the truth and wander away to myths” (2 Tim 4.3-4). 2 Timothy adds, “You must understand this, that in the last days distressing times will come. For people will be lovers of themselves, lovers of money, boasters, arrogant, abusive, disobedient to their parents, ungrateful, unholy, inhuman, implacable, slanderers, profligates, brutes, haters of God, treacherous, reckless, swollen with conceit, lovers of pleasure rather than lovers of God, holding to the outward form of godliness but denying its power” (2 Tim 3.1-5). This moral degeneration, according to other New Testament epistles, will invoke the fiery wrath of Christ.

The writer of 2 Thessalonians envisions a time “when the Lord Jesus is revealed from heaven with his mighty angels in flaming fire, inflicting vengeance on those who do not know God and on those who do not obey the gospel of our Lord Jesus. These will suffer the punishment of eternal destruction, separated from the presence of the Lord and from the glory of his might” (2 Thess 1.7-9). And at this time, “the lawless one will be revealed, whom the Lord Jesus will destroy with the breath of his mouth, annihilating him by the manifestation of his coming” (2 Thess 2.8). The Pauline Epistles – especially those no longer attributed to Paul – speak of a time when the meek, cheek-turning behavior that Christ advises in the Gospels will have to be set aside for Armageddon. The author of Ephesians writes – slightly longer quote here:

For our struggle is not against enemies of blood and flesh, but against rulers, against the authorities, against the cosmic powers of this present darkness, against the spiritual forces of evil in the heavenly places. Therefore take up the whole armor of God, so that you may be able to withstand on that evil day, and having done everything, stand firm. Stand therefore, and fasten the belt of truth around your waist, and put on the breastplate of righteousness. As shoes for your feet put on whatever will make you ready to proclaim the gospel of peace. With all these, take the shield of faith, with which you will be able to quench all the flaming arrows of the evil one. Take the helmet of salvation, and the sword of the Spirit, which is the word of God. (Eph 6.12-17)

The apocalyptic prophecies in throughout Pauline Epistles are diverse. Some envision a final deliverance and corporeal resurrection, undertaken by God, that happen as in a sudden flash of light, sorting out the injustices of the cosmos in an eye blink. Others depict a final war between good and evil. The Book of Revelation, the most important apocalyptic text in Christianity, involves a similar mashup of last judgments, sometimes instantaneous chronological narrative jumps between rotten present and glorious eternity, and at other times martial clashes between the forces of good and evil.

To return more generally to the subject of salvation in the Pauline Epistles, then, apocalypticism is the fourth and final means for the deliverance of the faithful in the New Testament. Those who want to be saved, we learn from Paul, might pursue their salvation by good works, or by faith alone, or by faith whose inevitable outcome is good works. Those seeking salvation might simply be predestined to salvation or damnation from the beginning of time. And at the end of time, whatever the intermediary mechanics of salvation are, those seeking salvation may experience some sort of bodily resurrection and eternal life, depending on either their good works, their faith, their predetermined fates, or some combination thereof.

The fourfold possibilities of salvation in the Pauline Epistles, then, have given theologians plenty to contemplate. In a way, the doctrine of judgment day and corporeal resurrection, originally a product of a Jewish ideology that had no doctrine of posthumous salvation, is redundant in Christianity. In other words, if we are judged, however exactly we are judged, after death, to the individual believer, who has already received her eternal rewards or punishments in the afterlife, a judgment day is superfluous. However, this sort of analysis is anachronistic. The doctrine of Christian salvation, as we’ve seen over the past hour or so, was in the Pauline Epistles in a state of flux and historical development, as too were the apocalyptic doctrines floating all over the Eastern Mediterranean. Parthian Zoroastrians taught that judgment day was on the way, just as some surviving Egyptian texts from around the time of Christ – like the Oracle of the Potter and the Prophecy of the Lamb sound pretty much like what the New Testament would have sounded like if it had been written in Egypt. One of these, the Prophecy of the Lamb, our surviving copy of which was copied around 7 BCE, states the following:

[And it will] happen in the time in question that the rich man will become a [poor] man. . .[. . .Falsehood will thrive] in Egypt. Men will not speak the truth. […] Many [evils(?) will be] in Egypt, inflicting injury. . .against their standing men. . .[Then] A man will go before [his companions]; he will say to them what is. . .in his heart. . .Truth will be manifest. Falsehood will perish. Law and judgment will occur within Egypt. The shrines of the Egyptian gods will be recognized for them at Nineveh in the district of Syria. When it [happens] that the people of Egypt go to the land of Syria, they will control its districts and they will find / the shrines of the Egyptian gods. Because of the good fortune that will happen in Egypt they will be speechless., The one abominable to god will fare badly. The one beneficent to god will receive beneficence from god.18

This prophecy, penned in the new Roman province of Egypt around the time Paul’s parents were teenagers, contains the various elements of Jewish and Christian apocalypticism – things will go downhill, but then the poor will be made rich and the rich poor, some sort of messiah figure will show up to speed things along, the good will be rewarded and bad punished, and our god or gods will be recognized as legitimate.19 This is what ancient Mediterranean apocalyptic writing sounds like, and we’ve found more and more of it in the Dead Sea Scrolls and Gnostic scriptures, and so we shouldn’t be surprised to find it in the Pauline Epistles, even if it sits adjacent to different, more individual-centric doctrines of salvation.

Before we move in, let’s review what we’ve talked about so far. We started by looking at the sparse peppering of ethical instructions in the Pauline Epistles. These instructions are nowhere near the size and detail of those in Mosaic Law, and we learned that Paul dismisses Mosaic Law, sometimes quite forcefully, often in the Pauline Epistles. We also learned that, while Paul provides a smattering of ethical instructions to his readers on various subjects, he more broadly embraces a mind-body dualism in his letters, complaining that his wayward body sometimes goes its own way in spite of the best efforts of his mind and spirit, and also recommending celibacy and avoiding wedlock as the best paths to spiritual fulfillment.

The rest of the present program has been on the issue of salvation in the Pauline Epistles. We considered those parts of the letters that seem to promote the idea of salvation through good works, and learned a bit about the legacy of interpreting the New Testament this way, which led to the Pelagian controversy in the early 400s. And then we looked at sections of the Pauline Epistles that have to do with salvation by faith, the importance of this idea during the Protestant Reformation, and how Paul may have believed that spiritual faith automatically led to the practice of good works. Finally, we considered the two other ways salvation gets discussed in the Pauline Epistles – first, the doctrine of predestination, or limited atonement, which comes up once or twice in Paul’s writings, and second, the doctrine of apocalypticism, that fourth and final idea about salvation that holds that at some final juncture at the twilight of time, all of the good will be rewarded and evil punished.

For especially my Christian listeners who know these texts well and perhaps have well-formulated but different takes on them, let me say that I appreciate your patience and apologize if I’ve failed to engage with the Pauline Epistles in ways that make them meaningful to you. This is a complex juncture of a complex book which humbles all of us, and I’m under no illusions that I can provide anything other than a general structural introduction. Still, before we move on to the other epistles in the next program, I do have one more thing I’d like to think about with you for a while – and I should add that this is driven by a personal interest in the New Testament Epistles. Here goes. [music]

Paul’s Blind Spot: The Theological Developments of the Late Second Temple Period

We all have different paths toward learning about the Bible, depending on our upbringings and our interests. I, personally, read the New Testament only after having read the Old Testament. And not just Genesis and a potpourri of Psalms – but the whole thing, together with Apocryphal literature stretching deep into the Second Temple period – the masterful Wisdom of Solomon and optimistic Book of Tobit, cut from Protestant canons, the book of Second Esdras, cut from all major bibles except the Slavonic one, and all the Maccabees and history of Jerusalem under Alexander’s successor kingdoms, followed by the Hasmonean and Herodian dynasties, under which the fascinating Books of 1 Enoch and Jubilees were written. While I’m not Jewish myself, I find often that my interests in the New Testament have to do with its Jewish heritage and the way that its authors, Jewish or Gentile or something in between, envisioned their new theology’s relationship with the older one already being practiced in first century synagogues.My interests drove the analytical portion of our program on the Gospels, in which we took a closer look at the Pharisees and the Sadducees, those largely faceless gaggles of individuals whom Jesus clobbers in arguments again and again in Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John. We learned that the Pharisees, while they were indeed associated with a punctilious devotion to written and oral law, also had a lot in common with first century Christians. The Pharisees believed in life after death. They believed that the Hebrew Bible was not the final word, but that more would be written. And unlike the aristocratic Sadducees, the Pharisees were popular with the commoners, just as Christianity would prove to be, century after century.

Julius Schnorr von Carolsfeld’s Ruth in the Field of Boaz (1828). Ruth, a postexilic narrative placed in the otherwise dark and gloomy Deuteronomistic History, exemplifies how Judaism and its writings were changing in the cosmopolitan and diasporic climates of the Persian and Hellenistic periods. One of Judaism’s evolutionary lines was of course the Pauline epistles, and through them, Christianity.

The Jewish writings that we have from the Second Temple period do not show a sterile, calcified, conservative culture prattling about Mosaic Law while the rest of the world evolves. During the Achaemenid, Hellenistic, and early Roman Imperial periods, Judaism, too, was evolving. Zoroastrian ideas glimmer in the Books of Daniel and Tobit. Greek philosophical idioms and ideas shine throughout the Books of Maccabees and the entire corpus of Second Temple literature produced during the late second and early first century CE. 1 Enoch is the most important apocryphal scripture on Earth, demonstrating that most of the ideas of the New Testament were already pinballing around Jerusalem a century before Jesus was born. The Dead Sea Scrolls, which fill nearly 700 pages of the standard Penguin translation of them, show a theological world in flux just east of Jerusalem – one at a cusp between Mediterranean West and Parthian East, with plenty of elements from both. During the life of Jesus, Judaism was already a faith that flourished on multiple continents, which had evolved into several different main sects.

Historical events altered the textual output of Second Temple Judaism. A lot of Second Temple period literature is sunnier and more optimistic than the older parts of the Hebrew Bible. The Pentateuch, Historical Books, and majority of the Prophetic Books were made in the often traumatizing crucible of the 600s and 500s. But as dawn broke on the Achaemenid period of Jewish history, and later the Hellenistic period, while these periods certainly brought new challenges, they also brought long stretches of tranquility and economic opportunity. The Book of Ecclesiastes shows us a world of almost wearisome commercial plentitude. Sirach offers a mass of often stuffy proverbs and directive to pursue wisdom in a book that often sounds more like the epistles of the Roman poet Horace than anything biblical.

The full version of Esther – with its Greek additions – is the tale of a resilient Jewish woman in a faraway land who, through her intelligence and her resourcefulness, helps secure the longevity of diasporic Jewish community in modern day Iran. The Book of Judith, while its internal historical knowledge is sketchy, is nonetheless another tale of a Jewish heroine – one who saves her small town from a marauding army and enjoys prosperity thereafter. In the folkloric Book of Tobit, another Second Temple period story, God helps a lovelorn girl marry an eligible suitor and heals the suitor’s father. Jonah, a late prophetic book, is the tale of a seemingly doomed city, Nineveh, receiving a warning from a reluctant prophet, repenting, and thereafter enjoying the kindly forgiveness of Yahweh. In all of these Second Temple period books, by all means pioneering works of prose narrative in addition to everything else, the doom and gloom of books like Numbers, Deuteronomy, and 2 Kings has dissipated. Israelites are largely able to take their fate into their own hands through the force of their own volition, Yahweh is much less furious and capricious, and at times – such as in the Book of Jonah – he is more than willing to let sinners repent for their misdeeds on earth once they’ve understood the nature of their transgressions and learned their lessons.

Toward the end of the Hebrew Bible is the Song of Songs, that ancient poem often dated to the Second Temple Period. While we often read this book today as an Ancient Near Eastern love poem that, for whatever odd reasons, made its way into the Old Testament, Jewish commentators have declared it an impassioned exchange of affection between Yahweh and the people of Israel. If there is something to this, then – and indeed Yahweh as a bridegroom and Israel as a bride surface often throughout the earlier Prophetic Books – then toward the end of the often dark Hebrew Bible we get the sense that Yahweh ultimately does love the Israelites, and taking into account other works of Second Temple literature, that Yahweh can forgive trespasses, that good things are happening to good people, and that life is quite a bit better than it was in the bygone days of Assyrian and Babylonian invasions. In short, there is a joy, and a lightheartedness in the patchwork of texts that make up Second Temple literature, some apocryphal, and some not, that we often forget when we read strictly within the confines of our Biblical canons, if we even bother much with the Old Testament in the first place.

The Pauline Epistles, broadly speaking, paint a starker portrait of Second Temple Judaism than what we actually see in books like Tobit and Jonah, as though all there is to Judaism is the Pentateuch’s rules and then a Hindenburg inferno of a failed covenant. In the words of scholar Craig Hill, writing on the Book of Romans, “The popular picture of first-century Judaism as a religion of sterile legalism, supercilious piety, and haughty self-righteousness is not supported by Jewish documents. When allowed to speak for themselves, first-century Jews are not heard advocating a religion of merit, the photo-negative of a uniquely Christian notion of salvation by grace. Functionally, [first century] Judaism and Christianity are quite similar: one ‘gets in’ by means of God’s gracious calling; one then is obligated (not least by gratitude) to obey the will of God, however defined.”20 This, then, to me, was what was puzzling about Paul’s doctrines of salvation. People had already been getting joyfully saved throughout the texts of the Second Temple period – the Ninevehites in Jonah, forgiven by God, the Persian diasporic Jews in Esther, the frightened Judahites in the Book of Judith, the good and pious believers in 1 Enoch, gentle old Tobit, in his book of the Bible, the unnamed Jerusalemites who are neighbors of the preacher in Ecclesiastes, eating, drinking, and being merry as the book advises. I think I had some questions about Paul’s doctrines of salvation in his epistles because to me, apocalyptic salvation had unquestionably been there all along in the Old Testament, and in addition to that, Second Temple texts were showing an increasingly gentle Yahweh, and connectedly, increasingly rosy portraits of Jewish life on earth. I am not the only one who has noticed this blind spot in the Pauline Epistles.

To quote scholar Craig Hill again,

Needless to say, the existence of any pre- or non-Christian Judaism in which one might find right relationship with God creates a severe problem for Paul. On the one hand, he wants to argue that God saves only in Christ and that Judaism, apart from Christ, is a way of ‘sin’ and ‘death’ (Rom 7:9-11); on the other hand, Paul feels compelled to cite precedents in Judaism for God’s saving [people]. The question is, can one have it both ways? Paul might have argued on the basis of essential continuity: the God of the Jews, always a God of salvation, has worked this saving purpose ultimately in Christ. . .Instead, Paul’s argument traces the line of essential discontinuity, which is precisely what Marcion and other despisers of Judaism have found congenial in his thinking.21

In that quote, we heard the name “Marcion.” Born a couple of decades after Paul died, Marcion was one of the most influential Christian theologians of the second century. Paul, as we’ve learned in this program, was ready to set aside some of the more elaborate and inconvenient aspects of traditional Jewish law to win Gentile converts. Marcion, however, and a certain lineage of early Christian thinkers, were willing to set aside Yahweh, the Old Testament, and all of Judaism. [music]

Two Early Christian Responses to Paul: Marcion and Chrysostom