Episode 80: The General Epistles

The later epistles of the New Testament show early Christian theology expanding and evolving in the ancient Mediterranean.

| Read Transcription | References and Notes |

| Episode Quiz | |

| Episode on Spotify | Episode on Apple Podcasts |

| Previous Show | Next Show |

The New Testament General Epistles of James, John, Peter and Jude

Gold Sponsors

ML Cohen

John David Giese

Silver Sponsors

Chad Nicholson

Jaclyn Stacy

John Weretka

Lauris van Rijn

Michael Ellis

Michael Sanchez

Mike Swanson

Patrick Radowick

Sponsors

Alejandro Cathey-Cevallos

Alysoun Hodges

Amy Carlo

Angela Rebrec

Benjamin Bartemes

Caroline Winther Tørring

Chris Brademeyer

Daniel Serotsky

David Macher

Earl Killian

Francisco Vazquez

Henry Bakker

Jeremy Hanks

Josh McDiarmid

Joshua Edson

Kyle Pustola

Laurent Callot

Leonie Hume

Lucas Deuterman

Oli Pate

RH Kennerly

Anonymous

Anonymous

Rod Sieg

De Sulis Minerva

Rui Liu

Sebastiaan De Jonge

Sonya Andrews

Susan Angles

Verónica Ruiz Badía

Christianity has never been just one thing. In the mid 200s, the Christian theologian Origen admitted that there were as many sects of Christianity as there were within pagan philosophy.2 Several of the Church Fathers are equal parts doctrinal and heretical by modern standards. A century before Origen, the Christian theologian Justin Martyr was so interested in the idea of the logos written of at the beginning of the Gospel of John that he seemed at times to believe in a separate god, different than the Old Testament Yahweh. Origen himself, central as he was to early Christianity, developed an idiosyncratic and elitist means of biblical interpretation which was later broadly rejected. Also in the early to mid 200s, another heavyweight Christian theologian Tertullian, near the end of his career, joined a heretical sect called the Montanists and as a result was never canonized as a saint. Over the 100s and then 200s and 300s, Gnosticism and Manichaeism proliferated, both being Christ-centered religions, but ones that were utterly different than what we call Christianity today. Put simply, all sorts of Christ-related worship practices, theology and philosophy were being undertaken during the first three centuries of Christianity, and through the proving grounds of debate and controversy, the raw materials of the New Testament were slowly worked into different branches of official ecclesiastical doctrine.

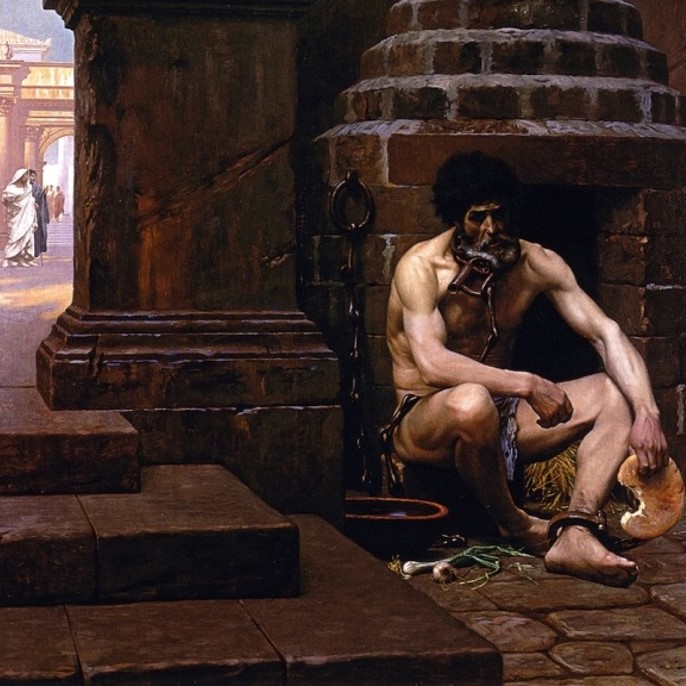

Rembrandt’s Apostle Paul (c. 1633). The Gospels, Acts, and Pauline Epistles did not settle doctrine in Christianity, as the later general epistles attributed to James, John, Peter and Jude demonstrate.

Roman Catholicism’s drive toward orthodoxy, and toward a consistent canon of scriptures, came in response to a cyclone of divergent trends that nearly splintered into several equally legitimate branches of Christianity in the immediate three centuries after Jesus lived. Through the Gospels and Acts we’ve already learned about how the Apostolic generation had to decide what to do with Mosiac Law. The Pauline Epistles deal with this same question, in addition to laying out four different doctrines of salvation which have been hotly debated for almost two thousand years: salvation by good works, salvation by faith, predestination, and apocalyptic salvation. But beyond just Mosaic Law and the issue of how salvation actually worked – beyond major alternate Christianities like Gnosticism and Manichaeism – the second, third, and forth generations of Christians fanned out into an array of movements seldom discussed outside the realm of early Christian theology – Marcionism, the Valentinian movement, the Montanists, and initial sectarian disagreements about the exact nature of Christ that would last a full six hundred years and rattle the church through six ecumenical councils. Had Christ been an uncreated part of God for all eternity? Was Christ born a human, and then filled with the spirit of God? Was he born half human, half God, or was he born all God, and if he were an uncreated god, his death on earth was meaningless, wasn’t it? If he were half human, half god, how did his two natures co-exist, and how did his two wills coexist? All these questions were not semantics or splitting hairs for Christianity’s often intensely philosophical first seven hundred years – answering them was the central work of major councils, theologians, essays and commentaries.

It is within the general epistles of the New Testament – the ones we’re going to read today – that we can begin to hear the first waves of Christianity break on the pagan world, and wash back with all sorts of flotsam and jetsam – questions, skepticism; converts, certainly, but converts who in some cases didn’t feel quite right to those who had been practicing the religion for a little while. By the time the general epistles that we’ll look at in this show were written, the Apostles were gone. The actual teachings of Christ had developed within a wide array of documents and orally transmitted precepts. Early Christian writings existed, including ones now rejected from most canons, but even the most ardent practitioners lacked a standard omnibus of works considered sacred. In the Pauline epistles, we witness Paul installing and stabilizing the first Christian churches. But the general epistles are products of later generations – authors who lived after the Apostles wrote letters with apostolic names on them, and did their best to reconcile the teachings of their progenitors with the messy realities of Christianity in the wild west of the Roman Empire.

So in the remainder of episode, I’d like to do two things. First, we should talk about the books of James, Peter, John, and Jude in detail, and consider the parts of them that have been of special interest to Christian theology and church history. And second, because these books show traces of some of Christianity’s earliest evolutions and engagements with Greek religion and philosophy, we can use these epistles to discuss why various Christ-centered worship practices expanded in the Mediterranean world throughout the first three centuries – a giant question, certainly, but one to which these general epistles offer us a nice little introduction. We should begin with an issue left unresolved last time – that complicated and thorny subject of salvation. What, the Apostle Paul’s readers have asked for centuries, does salvation require? Good works? Faith? Does one lead to other? Is one possible without the other? On this subject, the author of the Book of James, sometimes thought to be the brother of Christ, and more often, a later pseudepigraphal author, famously added his thoughts.

Good Works vs. Faith in the General Epistles

The issue of salvation by faith versus salvation by good works has been a perennial concern in Christianity, coming up most famously in the first decades of the 400s, with what historians call the Pelagian controversy, and then once again in the first decades of the 1500s, with Luther’s Ninety-Five Theses and the beginning of the Protestant Reformation. Let’s consider this dichotomy for just a moment – this issue of salvation by faith versus salvation by good works, reviewing some stuff we covered last time.Initially, to the earliest Jewish Christians seeking conversions from a Gentile population, the notion of salvation by works was tied into Mosaic Law. One of the things that drew the Apostle Paul to differentiating salvation by faith and salvation by works was a desire to show prospective and existing Gentile converts that no matter what Jews and Jewish Christians told them, they could indeed be saved by Jesus, even without circumcision and attention to the long list of regulations written in the Pentateuch. The Apostle Paul, in a verse that Martin Luther loved so much that he purposely mistranslated it, wrote, “For we hold that a person is justified by faith apart from works prescribed by the law” (Rom 3:28). To theologians like Luther and Calvin, this verse meant that no matter what you did, no matter how many ecclesiastical loopholes you jumped through, no matter how much cash you gave to the church, worldly actions would not affect your salvation. Paul also wrote that “[W]e have come to believe in Christ Jesus, so that we might be justified by faith in Christ, and not by doing the works of the law, because no one will be justified by works of the law. . .for if justification comes through the law, then Christ died for nothing” (Gal 14-15,21). This is an extreme statement, and it comes up up centuries later in one of Christianity’s early ecumenical councils. The Pelagian heresy, which emerged around 400 CE, stemmed from the British theologian Pelagius’ notion that believers had the sovereignty to follow a set of rules, using discipline and the exercise of free will, and to some extent, determine their fates in the eyes of God. Contemporary history has reevaluated Pelagius’ teachings as more orthodox and less heretical than they were once received, but in Pelagius’ own time, thinkers like Augustine accused him of being an arrogant schismatic who had elevated the following of law and good works to far too high a pinnacle, and in doing so, minimized the role of God in the mechanics of salvation. Later, Martin Luther read Paul’s statements that minimized the importance of good works as evidence that the Catholic Church’s selling of indulgences was not only greedy, but also in direct opposition to the teachings of the Apostles.

In a word, then, the Pauline Epistles have been the central battleground over which the debate between salvation by faith and salvation by good works has been fought.3 And most commonly in Christian history, whatever Paul actually believed, he has been read as a supporter of the idea that faith is ultimately all that’s necessary for salvation. If there is an opposite perspective espoused in the New Testament, that perspective is most clearly expressed in the first of the later epistles we’ll cover today, the Book of James, which should perhaps be called “the six page document of James.” Really, in fact, we’re a ways past the point at which these brief later sections of the Bible ought to be called books. Anyway, again, if there is a portion of the New Testament that draws a line in the sand and supports the notion that good works are more important than faith, this is the Epistle of James, which states, famously that “Even the demons believe – and shudder” (Jas 2:19). In other words, anyone can have faith in the primacy of God and the salvation of humankind by Jesus Christ, even devils, and so faith alone is meaningless.4 The Epistle of James, however, goes on for some time in its discussion of salvation by good works, perhaps in response to Paul’s more lax attitude toward the necessity of following rules and commandments. Let’s hear a section of the Epistle of James, a book of uncertain authorship and chronology, of which we can probably only safely say that it was written some time in the second half of the first century. James writes, in the New Oxford Annotated Bible:

What good is it, my brothers and sisters, if you say you have faith but do not have works? Can faith save you? If a brother or sister is naked and lacks daily food, and one of you says to them, “Go in peace; keep warm and eat your fill,” and yet you do not supply their bodily needs, what is the good of that? So faith by itself, if it has no works, is dead. But someone will say, “You have faith and I have works.” Show me your faith apart from your works, and I by my works will show you my faith. You believe that God is one; you do well. Even the demons believe—and shudder. Do you want to be shown, you senseless person, that faith apart from works is barren? Was not our ancestor Abraham justified by works when he offered his son Isaac on the altar? You see that faith was active along with his works, and faith was brought to completion by the works. Thus the scripture was fulfilled that says, “Abraham believed God, and it was reckoned to him as righteousness,” and he was called the friend of God. You see that a person is justified by works and not by faith alone. Likewise, was not Rahab the prostitute also justified by works when she welcomed the messengers and sent them out by another road? For just as the body without the spirit is dead, so faith without works is dead. (Jas 2:14-24)

That’s a big chunk of text, but the main idea is that faith without good works to actualize it is not meaningful. Other later epistles in the New Testament echo James’ emphasis on following commandments and pursuing good works. 1 John puts it simply: “For the love of God is this, that we obey his commandments” (1 John 5:1). More emphatically, 1 John states, “Now by this we may be sure that we know him, if we obey his commandments. Whoever says, ‘I have come to know him,’ but does not obey his commandments, is a liar, and in such a person the truth does not exist” (1 John 1:3-4). So, to many interpreters, the Pauline and non-Pauline epistles seem to take the sides of a royal rumble on the issue of salvation, with Paul saying that faith is what you need for salvation, and the others that good works will do the trick. While Paul also emphasizes the importance of good works, and the non-Pauline epistles also emphasize the importance of faith, generally speaking there are more statements about salvation by good works in the epistles of James, John, Peter and Jude.5

Between Paul’s work in the 50s, then, and the later letter writers of the 80s, 90s, and 100s CE, there seems to have been an increasing need to emphasize that at least some sort of regulatory framework was needed in addition to mere faith. Paul’s converts, as we learned last time, included at least some and possibly a great many “god fearers,” those Gentiles familiar with, and sympathetic to Jewish culture and tradition. As Christianity swelled in the urban centers of the Eastern Mediterranean, though, and thoroughbred Gentiles came into the fold, a code of laws beyond mere faith seems to have been called for, and we hear this call go out in books like James and 1 John. According to church historian Henry Chadwick, conversion to Christianity didn’t necessarily bring with it the prudence and restraint that we associate with Christianity today. Chadwick writes,

It is not surprising that in some cases the impact of Christianity was to produce emotional excitement and [lawlessness]. . .and misunderstood Pauline language about freedom from the law and the inheritance of the sons of the kingdom might easily make things worse. It was in answer to such dangers of anarchy that a strongly moralistic emphasis appeared in Christian writings of the second century, which it is all too easy to disparage as a falling off from the first vigour of the apostolic age. Round about A.D. 100 it must have seemed that new converts of Gentile origin needed no kind of instruction so urgently as clear moral rules and exhortations to good works.6

Not just in the year 100, but in all recorded phases of Christianity, there has been a continuum with highly emotive and expressive forms of worship on one side, and more solemn and restrained forms on the other side. We can see this spectrum in modern Christianity with, say, Pentecostalism on one side and Lutheranism on the other, although of course individual churches within denominations vary in their practices. At times, such as during the First Great Awakening, the continuum has closely resembled what we might imagine existed in the world of early Christianity around the year 100 – the American 18th century saw rock star preachers like George Whitefield and Gilbert Tennent gaining groundswells of followers through camp meetings while more restrained theologians like Jonathan Edwards grinded their teeth and worried that converts were mistaking mere emotion and adrenaline for genuine religious experience. Since long before Christianity, surely, there have been those of us for whom religion is a matter of demonstrative and animated public experience, and those of us for whom religion is a more solitary, temperate affair.

The American theologian Jonathan Edwards (1703-58), like the author of the Book of James and other writers of the general epistles, worried about mere religious enthusiasm being mistaken for genuine piety underscored by action and self-conduct.

To understand the takeaway from all of this, we need to return to the issue of salvation by faith versus salvation by good works, and make some basic conclusions. Various eras of, and fissures within Christianity have taken sides on this dichotomy, cherry picking verses from Paul, or the general epistles, in order to argue that you need to do stuff to be saved, rather than just having faith, or the other way around. What we actually see if we put all of the New Testament epistles on our desk, in the loose chronological order that biblical scholarship has been able to establish, is that an initial generation of proselytizers, chief among them Paul, emphasized the possibilities of salvation by faith, after which a second and third generation, chief among them the authors of the epistles James and 1 John, backpedaled a bit and wrote that good works were at least as important as faith. There were historical reasons for this that we’ve discussed – as early Christianity burgeoned beyond the neighborhoods of synagogues and into the greater Roman world, new converts had to be wrapped on the knuckles for acting out of line with the implicit behavioral expectations of their ministers. This story – the story of two or three different generations of proselytizers having to respond to different demographics of converts – may be all there is to the New Testament’s fairly diverse statements about how salvation works. Several different major disputations within Christianity have gone toe to toe on good works versus faith alone, but even the book of the Bible that most emphasizes the importance of good works, which is the epistle of James, has statements about the importance of faith, just as the book of the Bible that most ardently emphasizes the importance of faith, Romans, also emphasizes the importance of good works.7

So, I realize that to those who are not Christian, the issue of salvation by faith and salvation by good works is perhaps not the most spellbinding topic. Additionally, I think that to modern Christian communities, the notion is that faith and good works dovetail to make a Christian, and so maybe even to Christians the history of theological quibbling over faith versus good works is a pretty dry topic, as engrossing as it was to several important generations of theologians. So let’s move on to another, and actually much simpler issue, related to the New Testament epistles – something that we can call the issue of how to be a Christian in Roman provinces that were, at best, indifferent to Christianity, and at worst, quite awful to Christianity. In our program on the Book of Acts, we reviewed some of the Roman world’s early records of Christianity – Tacitus on Nero’s persecutions after the Great Fire of 64, Pliny the Younger on Christians south of the Black Sea and Trajan’s response back to him in the year 112, and Cassius Dio and Eusebius on the Emperor Domitian’s persecutions that began in 303. These historical sources give us Rome’s perspective on early Christianity. But in the New Testament’s general epistles, we get to hear the other side of the story – how the earliest Christian worship communities dealt with the pummelings of a hostile world, and how these pummelings affected the religion’s ideology. [music]

The General Epistles on How to Be a Christian

The general epistles of the New Testament tell Christians how to live and work in the larger Greco-Roman world. If there is a central message on how to do this, it might be summed up best by a line in English poet John Milton’s defense of free speech, a tract called the Areopagitica that the author wrote in 1644. Milton states, “I cannot praise a fugitive and cloistered virtue, unexercised and unbreathed, that never sallies out and seeks her adversary, but slinks out of the race. . .that which purifies us is trial, and trial is by what is contrary.”8 In context, this statement is about the necessity of being exposed to potentially prurient and incendiary printed material for the sake of understanding the difference between good and evil. But more broadly within Christian history, the idea that tribulation only makes faith stronger is a common one. The idea may have come partly from Greco-Roman stoicism, in which a common sentiment is that the stoic sage’s hardy self-sufficiency is forged and tempered through adversity, but really the notion that strife fosters strength is probably as old as the hills.

Jean-Léon Gérôme’s The Christian Martyrs’ Last Prayer (1863-83). While the painting is likely inspired more by the Book of Daniel and apocryphal writings on Paul than actual persecutions of Christians, its general message of grace under fire is by all means similar to what we find in the New Testament general epistles of James and Peter.

The general epistles do not, however, merely depict the experience of being a Christian as hunkering down and quietly becoming stronger in an inhospitable world. Enduring the pummelings of misfortune, the authors of the later epistles told their recipients, resulted in substantial rewards. The Epsitle of James assures its reader, “Blessed is anyone who endures temptation. Such a one has stood the test and will receive the crown of life that the Lord has promised to those who love him” (Jas 1:12). The pains of the earth, James and Peter in particular emphasize, are merely a prelude toward the pleasures of the afterlife for an abiding Christian, even though patience is required. James puts it into a nice metaphor: “Be patient, therefore, beloved, until the coming of the Lord. The farmer waits for the precious crop from the earth, being patient with it until it receives the early and the late rains” (Jas 5:7). And even though Christians must patiently bear the pains and disadvantages of being an often persecuted minority, these later epistles tell us, in a Christian’s suffering there is something divine. Specifically, as 1 Peter puts it, “Beloved, do not be surprised at the fiery ordeal that is taking place among you to test you, as though something strange were happening to you. But rejoice insofar as you are sharing Christ’s sufferings, so that you may also be glad and shout for joy when his glory is revealed” (1 Pet 4:12-3). Christians, then, in the New Testament’s later letters, were not only made stronger and purer by their trials, but also, in the depths of their sufferings, they took on the semblance and even the burden of their god.

The idea that, once again as Milton put it, “that which purifies us is trial, and trial is by what is contrary,” has been a powerful one in Christian history – this notion that even if all Christians can do is put up a hard defensive shell between themselves and persecutors, doing so fortifies and strengthens their faith. But the later epistles of the New Testament do more than telling Christians to be stalwart and Christlike amidst their tribulations. These portions of the New Testament also work to vilify and debase the non-Christian world as a benighted and ultimately sinful morass. As 1 John puts it, “We know that we are God’s children, and that the whole world lies under the power of the evil one” (1 John 5:19). And while 1 John is relatively mild in comparison to other later epistolary authors, 2 Peter and Jude lay into the pagan world with same fury and ferocity as the Old Testament prophets. A long quote from 2 Peter tells us that non-Christians

are like irrational animals, mere creatures of instinct, born to be caught and killed. They slander what they do not understand, and when those creatures are destroyed, they also will be destroyed, suffering the penalty for doing wrong. They count it a pleasure to revel in the daytime. They are blots and blemishes, reveling in their dissipation while they feast with you. They have eyes full of adultery, insatiable for sin. They entice unsteady souls. They have hearts trained in greed. Accursed children!. . .These are waterless springs and mists driven by a storm; for them the deepest darkness has been reserved. For they speak bombastic nonsense, and with licentious desires of the flesh. . .They promise them freedom, but they themselves are slaves of corruption. (2 Pet 2:12-19)

2 Peter, thankfully, spares us the Old Testament rhetoric about infants dashed apart on rocks and pregnant women being torn open, but the general notion of a blessed in-group, and an out-group that would really just be better off dead is still cut from the same cloth as Jeremiah and Ezekiel. The sentiments of the letter of Jude aren’t too far off from this. In another long quote, the Book of Jude describes pagan outsiders as

dreamers [who] defile the flesh, reject authority, and slander the glorious ones. . .these people slander whatever they do not understand, and they are destroyed by those things that, like irrational animals, they know by instinct. Woe to them. . .These are blemishes on your love-feasts, while they feast with you without fear, feeding themselves. They are waterless clouds carried along by the winds; autumn trees without fruit, twice dead, uprooted, wild waves of the sea, casting up the foam of their own shame; wandering stars, for whom the deepest darkness has been reserved forever. . .These are grumblers and malcontents; they indulge in their own lusts; they are bombastic in speech, flattering people to their own advantage. (Jude 1:8,10,12-13,16)

There are some identical notions in the two long quotes we’ve just heard – in both cases, an out-group is described as a bestial lot dwelling in a world of murky instincts, and depicted in various nature similes as fruitless, parched, lost, and damned to eternal darkness. Just as these New Testament condemnations of enemies echo similar sentiments from the Old Testament, 1 Peter takes a final step in the direction of the ethnocentric exclusivity of the Prophetic Books, stating, “[Y]ou are a chosen race, a royal priesthood, a holy nation, God’s own people, in order that you may proclaim the mighty acts of him who called you out of darkness into his marvelous light” (1 Pet 2:8-9). The line, with its sense of exclusivity and racial supremacy, might have come from Deuteronomy, and is noticeably out of step with the more ecumenical messages of the Pauline epistles. More generally, Christ’s teachings as we read them in the Gospels – judge not lest you be judged (Matt 7:1), why look at the speck in your neighbor’s eye and ignore the much larger thing in your own eye (Matt 7:4), let he who is without sin cast the first stone (John 8:7) – these and other sentiments at the beginning of the New Testament, likely produced a little earlier in Christian history than the later epistles, show that maybe the authors of the letters of James, Peter, John, and Jude lived in a world a little bit more wary of, and hostile to Christianity than the authors of the Synoptic Gospels did, and that these later authors, rhetorically, at least, were aiming to hit back.

So far, we’ve heard instances of the later epistles encouraging believers to let their trials bring them strength, and instances of the later epistles disparaging the pagan world as a gross and ignorant. In a more active and positive response to the outside world’s hostility and indifference, verses of the later epistles also endorse a third response to dealing with pagans, and this, in a word, is setting positive behavioral examples as Christians. The subject comes up from time to time throughout the latter parts of the New Testament, but most pronouncedly in 1 Peter. 1 Peter shares its generation’s general take on the wicked waywardness of Gentiles, telling its readers that pagans “are surprised that you no longer join them in the same excesses of dissipation, and so they blaspheme. But they will have to give an accounting to him who stands ready to judge” (1 Pet 4:4). But more memorably than the Ancient Mediterranean’s standard refrain that the good will be rewarded and the bad will be punished, 1 Peter also exclaims, “I urge you as aliens and exiles to abstain from the desires of the flesh that wage war against the soul. Conduct yourselves honorably among the Gentiles, so that, though they malign you as evildoers, they may see your honorable deeds and glorify God when he comes to judge” (1 Pet 2:11-12). In other words, be a good role model, and maybe those churlish and dangerous pagans will come around at some point.

The later epistles, then, show three different sorts of rhetorical strategies in dealing with the non-Christian world. First, grit your teeth and bear it, because in doing so you become a better Christian. Second, they’re all a bunch of untaught blasphemers who ought to just die, so don’t worry, they’ll get what’s coming to them. And third, that by being a good, prudent Christian, you might just inspire them to do the same. These three recommended strategies for coping with the indifference and hostility of the greater Roman world are based on a general dichotomy – Christians, and not-Christians. But, to move us on to the next section of this program, the world of the later epistles wasn’t just a simple world of us versus them – Christians against everyone else. From the beginning, it seemed, Christianity had doctrinal divergences. And if the central boogeyman in the epistles of Peter is the hostile Greco-Roman world beyond the cloisters of Christian communities, the main concern of the epistles of John is the factionalism within Christianity itself. [music]

Christology: The Main Issues and Gospel Sources

The Book of Acts and the Pauline epistles give us a sense of at least one schism in the Apostolic generation – the question of whether Christians ought to follow Mosaic Law, and if so, how much. This early controversy, already in the first century, was characterized by those who emphasized salvation by faith, those who emphasized salvation by good works, and then those who emphasized various combinations of the two. By the time the later epistles were written, however, a new controversy had come about – one which dominated Christianity for a thousand years. And it is to this central controversy – in a word, Christology – to which I finally want to turn our full attention for a little while.There are two parts to the Christology controversy. The first is the tricky question of how, in a monotheistic religion, God can have a son. In time, the most popular answer to this question was the Holy Trinity. The Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit are floating around in various passages of the New Testament, occasionally showing up in the same verses as a team, most importantly in one of the closing lines of the Book of Matthew, when Jesus tells his disciples, “Go therefore and make disciples of all nations, baptizing them in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit” (Matt 28:19).9 But while this and other verses have been cited as evidence that the New Testament implicitly endorses a tripartite God, trinitarianism came together slowly, showing up as doctrine in the written record for the first time in the pages of the church father Tertullian, who wrote “For we, who by the grace of God possess an insight. . .do indeed definitively declare that Two Beings are God, the Father and the Son, and, with the addition of the Holy Spirit, even Three, according to the principle of the divine economy.”10 This statement was written in the early 200s, and neither before nor immediately after it was written did the Christian world have its key doctrine of a tripartite God worked out, and so the New Testament’s epistles were all written before the Holy Trinity started showing up in texts as a way to explain the sovereign power of Christianity.

The earliest Christian theologians, then, had to figure out what the divine throne room of Christianity looked like. They also had to deal with a second, and equally tricky question – one which I mentioned earlier. This question was, what, exactly, Christ was. Was he half man, half god, or was he a man filled with the spirit of a god, or was he just an unusually inspired man, and if he had been half man, half god, how did his human and his divine aspects coexist? The umbrella term for the theological discussion of Christ’s nature is Christology, and Christology occupied Christianity’s theologians for a long time, giving way to a dictionary of polysyllabic terms for schools of thought on the subject – Arianism, Apollinarianism, Nestorianism, Eutychianism, Miaphysitism, Monophysitism, Dyophysitism, Monothelitism, and on and on. The central question of all of these schools – the central question that motivates what we again call Christology – is what Christ was, and by extension, what his sacrifice actually meant, and the controversy was as long and as complicated as it was because there was no easy answer.

Julius Sergius von Klever’s Christ Walking on the Waters (c. 1880). The Gospel of John’s Jesus is a serene, enigmatic, imperturbable figure – not a son born at the annunciation, but a being co-equal and co-eternal with the Old Testament God. John’s Jesus, more than Mark’s, influenced what became Nicene Christianity in the fourth century and long afterward. Some general epistle authors objected to this version of Christ.

This is certainly an unconventional take on the crucifixion. While we find some radically different depictions of Jesus from the second, third and fourth centuries in the Gnostic Nag Hammadi Library and Manichaean scriptures and elsewhere, the New Testament itself offers some surprisingly different statements about who and what Jesus was. The varying ways Christ is depicted in the four Gospels did little to settle the Christology controversies of the religion’s first millennium. In the Gospel of Mark, the proponents of the human Jesus found evidence in the crucified Christ crying out in agony, “My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?” (Mark 15:34). In the Gospel of John, the proponents of the divine Jesus noted that after sipping a bit of wine on the cross, he merely said, “It is finished” (John 19:30), a tragic moment, no doubt, but one also lacking the raw and human horror of the Book of Mark. Now, I don’t have an answer to the great questions of Christology, and many of us don’t have a horse in this particular theological race, but I hope I’ve at least explained the central debate decently – that the earliest Christian theologians sparred with one another energetically over the nature of Jesus.

With this background in our minds, let’s return to the subject of the later epistles. We will not go very deeply into either trinitarianism or Christology in this podcast, as important as these subjects are. But since we have the Books of James, John, Peter and Jude open on our desks, we can at least use them to broach the subject of just how early and thoroughly sectarian debates emerged in Christian history.

The Johannine School and the General Epistles

So let’s focus on the epistles of John for a moment. There are again three of them – 1 John, with five chapters, and then 2 and 3 John, with just one chapter each. We should differentiate the Epistles of John from the Gospel of John. In antiquity, predictably, the belief was that the Apostle John, a fisherman who’d become a follower of Jesus, wrote every single line of the Gospel of John, along with all three of the Epistles of John. Today, while scholarship will likely never reach a consensus on who wrote these documents, a common theory is that these documents may have been written by followers of the Apostle John some time after his death – about 90 CE in the case of the Gospel of John, and the Epistles of John a decade or more later.12 If you remember from a couple of episodes back, John is the non-Synoptic Gospel – in other words, the Gospel that doesn’t share verses with Matthew, Mark, and Luke, and also the Gospel that sounds the most Gentile of all of them. Often, as we learned a few episodes ago, the Gospel of John doesn’t call Jesus’ conversational sparring partners “Pharisees” or “temple priests,” but instead just “Jews.” So, due to its highly literary Greek style and a general sense that Jews were non-Christian others, modern scholars suspect that the sections of the New Testament attributed to John likely were not written by a Jewish, Aramaic speaking Galilean fisherman who’d known Jesus, but instead other writers, a bit later in the history of Christianity.To continue with the background on the Gospel of John and Epistles of John just a bit further, historians of early Christianity frequently discuss something called the “Johannine School,” a pronounced ideology within the pages of the New Testament that exists in the corpus of work attributed to John. The Jesus Christ in the Gospel of John is the stoic, thoroughly divine figure who merely says “It is finished” upon the moment of his death. The Johannine School works feel more compositionally elaborate, and more Greek in orientation. The Gospel of John begins with the rather philosophical statement that “In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God” (John 1:1), a verse that might have come out of Plato or the stoic philosopher Cleanthes – a verse that sent early Christian theologians down all sorts of rabbit holes to try and define what this “Word” thing was. More than its idiosyncratic creation narrative, though, the Johannine School is known for a widespread, and in my opinion very endearing, emphasis on the importance of love – the love of God, and the love of Christian brothers and sisters for one another. Two of the New Testament’s most famous verses come straight out of the Johannine school’s emphasis on love – John 3:16’s “For God so loved the world that he gave his only Son,” and the epistle 1 John’s “God is love” (1 John 4:8). Dangerous words, I know, but there was some pretty terrifying stuff going around in those Christian communities in the first century.

Anyway, the Johannine School was at once Greek in literary and philosophical background, and it also placed an extremely strong emphasis on love. The love that the Johannine School most often emphasizes is the love from God to Christian believers, and Christian believers for one another, rather than the universal property of human love out there in the world. 1 John is a bit milder than Peter and Jude, never calling pagans insentient animals, but 1 John does emphasize that non-Christians miss out on the celestial rewards of Christians. 1 John advises, “Do not be astonished, brothers and sisters, that the world hates you. We know that we have passed from death to life because we love one another. Whoever does not love abides in death” (1 John 3:13-4). Along these same lines, another verse in 1 John says essentially the same thing: “The children of God and the children of the devil are revealed in this way: all who do not do what is right are not from God, nor are those who do not love their brothers and sisters” (1 John 3:10). The ideas here are utterly familiar, of course – the bad folks are from the devil, the good, loving folks are from God. The Johannine epistles can sometimes state the earth-shatteringly obvious, as in this little tidbit of wisdom “Everyone who does what is right is righteous” (1 John 3:7). A profound statement, no doubt. However, 1 John’s main concern is not the Greeks and Romans who don’t worship Jesus, and their unrighteousness, or lack of love, but instead nominal worshippers of Jesus who are leading other credulous Christians down false and dangerous paths.

The Johannine School and Sectarian Conflicts in the General Epistles

So now that we’ve learned a bit about the Johannine school of belief, let’s return to that subject of the disputations of early Christianity. We’ve talked a lot in this series about the issue of Mosaic Law, and the issue of salvation by good works versus salvation by faith. As we peer into the Johannine school ideology, which produced the Gospel of John and Epistles of John, in addition to a highly philosophical and literary style, and an emphasis on love within Christianity, we also see the evidence of a third controversy, and this controversy is the issue of who and what Jesus was. The epistles of John often label other professed Christians as schismatics, or antichrists, a term first introduced at this juncture of the New Testament. Now, “antichrist” is a pretty heavy word, and its historical genesis is thus a subject of intrinsic interest. The word “antichrist” seems to have arisen during out of disagreement between the Johannine school, and an alternate school, a Christological debate in which the Johannine school backed the notion of a thoroughly divine Jesus, and their opponents backed the idea of a thoroughly human Jesus. This early Christological debate unfolded around 100 CE, when all of the Pauline epistles were sailing around the Mediterranean and the Gospels were likely all wrapped up.At this juncture – again, roughly 100 – there seems to have been at least one prominent disagreement in the Christian fold about what Jesus had been while he was on earth. This disagreement was between the Johannine school, and a teacher named Cerinthus, a Christian thinker at work in the same timeframe most of the New Testament was written – in other words about 50-100 CE. Cerinthus, according to the early Christian bishop and theologian Irenaeus, had some iffy ideas about Jesus – specifically, that Jesus was just a human being, temporarily filled with the spirit of God, which left him at the time of the crucifixion.13 Let’s hear a quote from the theologian Irenaeus on the subject of this heretical teacher Cerinthus. Irenaeus, roughly around the year 180 CE, wrote that a century earlier, the heretic Cerinthus had

represented Jesus as having not been born of a virgin, but as being the son of Joseph and Mary according to the ordinary course of human generation, while he nevertheless was more righteous, prudent, and wise than other men. Moreover, after his baptism, [the divine spirit of] Christ descended upon [the human Jesus] in the form of a dove from the Supreme Ruler, and that then he proclaimed the unknown Father, and performed miracles. But at last [the spirit of] Christ departed from [the human] Jesus, and that then Jesus suffered and rose again.14

The idea of Jesus being a mere human, to early Christians, was an anathema – after all, without his being the son of God, his sacrifice on the behalf of mankind lost some of its meaning. To the Johannine school, especially, whose aloof Jesus merely says, “It is finished” at the moment of his death, the notion of a human Christ was way out of line.

So, it’s possible that when the epistles of John differentiate between a loving inner community of Christians on one hand, and a delinquent outer world of antichrists on the other, this severe dichotomy was fueled by a contemporary theological crisis.15 According to that same source – the early Christian bishop Irenaeus, the Apostle John knew about the heretic teacher Cerinthus. Irenaeus tells a story in which “John, the disciple of the Lord, going to bathe at Ephesus, and perceiving Cerinthus within, rushed out of the bath-house without bathing, exclaiming, ‘Let us fly, lest even the bath-house fall down, because Cerinthus, the enemy of the truth, is within.’”16 It’s a colorful story, and, goodness knows whether or not it’s true, but on the whole it’s safe to assume that Christianity was moving in very different directions in the generations after Christ’s death, and that sectarian tension influenced what was eventually canonized as the New Testament.

John’s third epistle also attests to the rifts between early Christian bodies of worshippers, complaining to its recipient that a man named Diotrephes is slandering him and his congregation, and refusing them hospitality. John writes, “I will call attention to what [Diotrephes] is doing in spreading false charges against us. And not content with those charges, he refuses to welcome the friends, and even prevents those who want to do so and expels them from the church” (3 John 1:9-10).17 Whether slandered by other early Christians, or refused hospitality by them, or finding their teachings utterly heretical, the author of the epistles of John did not live in a world of unified Christian spirituality, and the texts that he left behind reflect a theologian working to legitimize his own sect against other competing ones. What comes up most emphatically is John’s opposition to specific divergences from his own strand of Christianity – divergences like the one associated with the very early heretic Cerinthus. Perhaps thinking of Cerinthus’ denial of the human Jesus’ divine parenthood, 2 John states that

Many deceivers have gone out into the world, those who do not confess that Jesus Christ has come in the flesh; any such person is the deceiver and the antichrist. Be on your guard, so that you do not lose what we have worked for, but may receive a full reward. Everyone who does not abide in the teaching of Christ, but goes beyond it, does not have God; whoever aides in the teaching has both the Father and the Son. Do not receive into the house or welcome anyone who comes to you and does not bring this teaching; for to welcome is to participate in the evil deeds of such a person. (2 John 1:7-11)

We can notice a couple of simple things there – the Johannine school author, contra the teachings of Cerinthus, makes it explicitly clear that those who deny that divinity has come to earth through Jesus are blasphemers. Further, while 3 John gripes about a man refusing hospitality to other Christians, 2 John tells its readers to refuse hospitality to any Christians who are doctrinally different – Christians, we might guess, who shared Cerinthus’ notions of a human Jesus.

There are two things to take away from this fairly detailed discussion of the Johannine school and its treatment of rival varieties of Christianity. The first, once again, is simply that rival varieties of Christianity existed by 90 or 100 CE, and they were shutting their doors to one another. The second is that it is a mistake to think that some central, doctrinally tabulated species of Christianity existed at this juncture of history. We need to remember that the doctrine of the trinity hadn’t been established yet. The doctrine of personal, merit based salvation, which we’ve discussed in this and the previous program, was not yet fully developed. Most importantly, as the differences between the Gospels of Mark and John demonstrate, Jewish Christians and Greek and Roman Gentiles worshippers had some pretty different takes on what, exactly, had happened with Christ’s coming to Earth.

Church historians, past and present, reterojecting their own ideology back into Christianity’s early centuries, have too readily employed the terms “heretic” and “orthodox” in order to differentiate between ideologies that fell by the wayside, and those that persisted. But return to the early scuffle between the Johannine school and Cerinthus, evidence in the New Testament exists to support both approaches. And while Cerinthus is maligned as one of Christianity’s many heretics, his human, but divinely inspirited Jesus, who cries out in Aramaic, “Eloi, Eloi, lama sabachthani” at the moment of his death, sounds a bit more like a carpenter’s son from Galilee than the Greek speaking immortal of the Johannine school. In contrast, from the beginning, the Gospel of John presents a different figure. The latest Gospel begins with “In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God.” In Koine Greek, the verse “ἐν ἀρχῇ ἦν ὁ λόγος, καὶ ὁ λόγος ἦν πρὸς τὸν θεόν, καὶ θεὸς ἦν ὁ λόγος” uses the word logos for God, the same word used in the stoic phrase logos spermatikos for the creation of the universe, and used in stoic philosophy for stoicism’s pantheist god. Of the two different ideological schools, then, with Cerinthus’ divinely imbued human and the Johannine school’s philosophically and temperamentally stoic deity, as of the year 90 CE there was no orthodoxy or heresy. One group of interpreters saw the fragile human figure cast aside by God at the climax of the Book of Mark and concluded that Jesus had been a person filled with a divine spirit. A second group of interpreters, steeped in Greek literary culture and philosophy, wrote of Christ as an impassive figure, and God as indistinguishable from stoic providence. The point isn’t that the New Testament portrays Jesus in variant ways – anyone who reads the Gospels notices this. The point is that when we label third, and second, and especially first century Christian sects as heretical, we assume the existence of an orthodox center of gravity in Christianity that, historically speaking, took hundreds of years, a lot of councils, and a lot theologians to put together. [music]

After the General Epistles: Growth in Christianity Between 100-250

The general epistles, as we’ve seen, are a great set of texts to study in order to learn about the complexity of very early Christianity. So far, we’ve learned that especially the Book of James, maybe responding to Paul’s general emphasis on salvation by faith, more often emphasizes the importance of good works. Looking at the later epistles as a mass, we’ve also seen how they envisioned and described the median Christian’s plight in a largely non-Christian world – that a Christian’s faith could be strengthened and purified through adversity, that Christians might inspire pagans through righteous conduct, that great rewards came from piety, and that pagans were misguided and ignorant, and would not get such rewards. We also learned just a moment ago that the Johannine epistles, in particular, reveal evidence of a pitched battle with a rival school over the exact nature of Christ, and had a quick introduction to the long history of Christological debates – again debates on the exact nature of Christ. What I want to do not is change topics a bit, and move from the New Testament to a more general consideration of early Christianity’s expansion over the late 100s, the 200s, and the 300s CE.

Origen in the Nuremberg Chronicle (1493), a student of key ideological strands in the general epistles. The theologian lived to witness Christianity providing for basic needs and services as the Roman Empire underwent various leadership disputes over the first half of the third century.

During the lifetime of the church father Origen Adamantius, who lived roughly from the 180s until the 250s, Rome had 17 emperors, beginning with the psychotic Commodus and coming to crisis point in the late 230s and throughout the middle of the century, when emperors seemed to be coming and going via a revolving door and often leaving trails of destruction in their wake. Origen’s work is a product of Rome’s crisis years, the Year of the Five emperors, in 193, occurring during his childhood, and the Year of the Six Emperors in 238, when Origen was in his 50s. Origen, while his record isn’t spotless in Christian theological history, was well known for his ideas on allegorical interpretation of the Bible, his exposition on the principles of Christian theology, and his production of the first critical edition of a Hebrew Bible. He also wrote a famous apology, or defense of Christianity, the title of which was Contra Celsum, or Against Celsus, a tract that defended Christianity against what had evidently been the thoroughgoing accusations of Celsus’ book On the True Doctrine, which had been written in the 170s – shortly before Origen’s birth. Origen’s book Against Celsus, again written around 250, is one of the most important works of early Christian theology that survives. The book Against Celsus sees Christianity on the defensive. The pagan critic Celsus had said Jesus was merely the bastard child of an unknown Roman soldier, that no deity had come down to earth, that Christianity’s Jewish origin stories were filled with genital mutilation and ignominious betrayals, and that Christians took part in sketchy and illegal pre-dawn rituals.18 And in his rebuttal against Celsus, the Christian theologian Origen, confident that all of these charges were ignorant or heretical, comes to his religion’s defense, chapter after chapter. And one of the more memorable moments in Origen’s defense of Christianity is his emphasis on the incredible extent to which it had grown by the mid 200s. Origen, on this subject, writes,

Any one who examines the subject will see that Jesus attempted and successfully accomplished works beyond the reach of human power. For although, from the very beginning, all things opposed the spread of His doctrine in the world, – both the princes of the times, and their chief captains and generals, and all, to speak generally, who were possessed of the smallest influence, and in addition to these, the rulers of the different cities, and the soldiers, and the people – yet it proved victorious, as being the Word of God, the nature of which is such that it cannot be hindered; and becoming more powerful than all such adversaries, it made itself master of the whole of Greece, and a considerable portion of Barbarian lands, and [converted] countless numbers of souls to His religion.19

By 250, then, Christians were not only conscious of their religion’s rapid growth, but they also cited this rapid growth as evidence of divine providence at work.

Now, as to whether or not Christianity spread due to divine providence, I am not qualified to say. What I can do, however, is tell you a little bit about the general scholarship on this subject – certain factors that historically catalyzed the spread of Christianity in the time between the Pauline Epistles in the 50s CE, and the writings of Origen two hundred years later. Writers on this subject often begin by citing a number of factors – the general preponderance of salvation-based cult religions leading up to Christianity, for example, and the instability of portions of the Roman Empire, caused not only plagues, financial mismanagement, imperial assassinations and succession disputes, but also by turbulence on the eastern front between Rome and the Parthian and Sassanid empires – all of this, for reasons we’ve often discussed, led to salvation-based cult religions looking pretty appealing to the average peasant, townsman, and slave. In our podcast, we have watched this general movement from indigenous community religions to salvation-oriented religions happening since the fourth century BCE.

Christianity’s Most Overlooked Reason for Expansion

The writings of Philo of Alexandria (c. 20 BCE – 50 CE) show another Ancient Mediterranean monotheism, but one without the call for worldwide conversion, quite unlike what we see in the general epistles.

The idea that one religion will devour all others and then the world will end is a familiar one from Christianity and Islam. But this was a notion that appeared definitively on the historical record, together with its appended call to proselytize, only in the first century, in the New Testament. As a point of contrast to the closing commissions of Mark and Matthew, let’s take a look at a couple of passages from Jewish intellectuals of the first century, just to get a sense of how other Mediterranean monotheists sounded during the generations of Jesus and Peter and Paul and their successors – namely, how different some of these Jewish writers sounded from the earliest Christians. We can start this comparison with Philo of Alexandria, an older contemporary of Jesus whose metropolitan roots in modern day Egypt afforded him a more diverse set of neighbors than the Aramaic-speaking hinterlands of Galilee might have. Philo is a sort of high water mark of the synthesis of the Hebrew Bible with Greek philosophy, a Platonist whose writings on God and the logos show Greek writers speculating about the word of God a couple of generations prior to the Book of John.21 And part of Philo’s brilliance as a philosopher is that he can at once espouse the universalism of Platonism, and at the same time hold a view of religion as a cultural force determined by regional and institutional factors. The Jewish philosopher Philo writes – fairly long quote here –

[S]ince there are some persons and things removed from other persons and things, not by a short distance only, but since they are utterly different, it then follows of necessity that the perceptions which occur to men of different things must also differ, and that their opinions must be at variance with one another. And since this is the case, who is foolish and ridiculous as to affirm positively that such and such a thing is just, or wise, or honorable, or expedient? For whatever this man defines as such, some one else, who from his childhood, has learnt a contrary lesson, will be sure to deny. . .[E]ven. . .the multitude of those who are called philosophers, pretending that they are really seeking for certainty and accuracy in things, being divided into ranks and companies, come to discordant, and often even to diametrically opposite [directions], and that too, not about some one accidental matter, but about almost everything, whether great or small, with respect to which any discussion can arise. (De Ebrietate 196-8)22

Here, we see Philo of Alexandria acknowledging the impact of geography and culture on belief system, and while he’s at it, emphasizing that the ruckuses and disputations of philosophy don’t exactly suggest that there’s one universal path to the truth. Elsewhere, Philo takes his relativism one step further, stepping nearly into the territory of sophism, as Philo proclaims,

[S]ince we are found to be influenced in different [matters] by the same things at different times, we should have nothing positive to assert about anything, inasmuch as what appears has no settled or stationary existence, but is subject to various, and multiform, and ever-recurring changes. For it follows of necessity, since the imagination is unstable, that the judgment formed by it must be unstable likewise; and there are many reasons for this. (De Ebrietate 170)

Now, as such, what we’re seeing here from Philo of Alexandria – again a Greek speaking Jew who lived from about 20 BCE to 50 CE – what we’re seeing here isn’t philosophically unique. Radical relativism had existed before in philosophical history, and it dominates postmodern philosophy and humanities scholarship today. The reason these quotes in Philo of Alexandria are worth knowing about is that they show that another Jewish monotheist, a little older than Jesus, Peter, and Paul, who worked in the intellectual capital of Alexandria, just three hundred miles from modern day Israel, taking a completely different route than the authors of the Gospels. The authors of the Gospels wanted everyone in the world to believe what they believed. For Philo, the possibility of such a thing happening would have seemed outrageous.

If Philo of Alexandria presents us with a modest and farsighted Jewish philosopher at the beginning of the first century, the historian Josephus, toward the end of the first century, offers us a Jewish perspective amply informed by experience in the larger Roman world. Now, the Alexandrian philosopher Philo was himself no stranger to Rome – we know he went on an embassy to meet with Caligula in about 40 CE. But Josephus had spent so much of his life with Romans that by the end of his life he had become a sort of cultural ambassador for Jews to Rome – one who sought to heal rifts and false suppositions caused by the Jewish-Roman war of 66-73.

In the preface to his book Jewish Antiquities, Josephus, who had been treated courteously by Titus and Vespasian, emperors central to the First Jewish-Roman War, politely explains why he set out to write Jewish history for the greater Mediterranean world. Maligned as a turncoat by his own and later generations, Josephus makes clear that his intention is a clear presentation of Jewish history from an insider, “as thinking it will appear to all the Greeks worthy of their study; for it will contain all our antiquities, and the constitution of our government, as interpreted out of the Hebrew scriptures.”23 Accustomed to the position of cultural intermediary, Josephus later wrote the book Against Apion, a firm defense of Judaism against a Greek sophist. In this book, we see Josephus debunking his argumentative opponent’s false stories about Jewish history and instead presenting Jews as a people with an immense history – one substantially longer than that of their Greek friends and neighbors in the Hellenistic world. While Josephus speaks firmly as a Jew, and with thoroughgoing familiarity of Jewish law, culture, and history, the gist of the book is never to convince the broader Hellenistic world of the ascendancy of Yahweh – merely of the vintage of Judaism and the consistency of its beliefs and practices over the ages.

So the main point, once again, of considering Philo and Josephus here is to draw a contrast between the Great Commission of Christ in the Gospels, and the more conscientious pluralism of the diasporic Jewish intelligentsia on the other. Philo and Josephus hardly represent all Jewish worshippers of the first century – obviously the First Jewish-Roman War of 66-73 was fought over a theologically charged nativism in conjunction with generational resentment of Roman greed. But Philo and Josephus do represent the Mediterranean world’s educated religious class, a body of writers who, as we’ve heard before, found Christianity objectionable on the basis of its exclusivity more than its – by that point in history, anyway – widespread notions of a son of a god, savior figure, posthumous salvation, and coming end of times.

So the first, and most important reason for Christianity’s immediate expansion may have been, once again, simply that it wanted to expand. The Dionysian parties that Euripides worried about in his play The Bacchae back in 405 BCE, those private gatherings with initiation rituals and secret promises of transcendence, were gradually gaining ground over the lifespan of Classical Greece, alongside other cult religious rites. But we do not possess, on record, anyone saying all in conjunction that Dionysus is the son of God, his religion is the sole religion in the world, and anyone who isn’t getting hammered in a torchlit cave every Thursday evening at 6:00 PM is going to get punished in Hades. Such a text might have existed. But in the written record, at least, Christianity comes on the strongest in its emphasis that it, and only it, had exclusive access to truth, divinity, and salvation. [music]

Early Christianity’s Main Turbines: Egalitarianism and Charity

So far, in this discussion of Christianity’s early expansion we’ve mostly talked about doctrine – the notion that Christianity expanded, first and most simply, because it wanted to expand. Doctrine is one of the ways that we understand a theological movement. But another way, to borrow the term “behavioralism” from anthropology, is to consider what sorts of actions a religion engenders in its adherents, regardless of that religion’s gods, goddesses, and other ideas. In addition to its doctrines, and maybe more importantly than its doctrines, Early Christianity inspired actions in its adherents. And one of the most important aspects of what Christianity did out there in the world, from the beginning, was charity. To quote church historian Henry Chadwick again,The practical application of charity was probably the most potent single cause of Christian success. . .Christian charity expressed itself in care for the poor, for widows and orphans, in visits to brethren in prison or condemned to the living death of labour in the mines, and in social action in time of calamity like famine, earthquake, pestilence, or war. . .Hospitality to travellers was an especially important act of charity: a Christian brother had only to give proof of his faith to be sure of lodging for a period of up to three nights with no more questions asked. The bishop had the prime responsibility of providing such hospitality, especially for travelling missionaries. The bishop accordingly controlled the church revenues. . .It was always recognized that the prime responsibility of the church treasury was to provide for the needs of the poor, and bishops who preferred to spend money on rich adornments and splendid churches were generally disapproved; in any event, there was no question of such elaboration before the time of Constantine. [Chadwick describes the work of the satirist Lucian of Samosata, who was quite critical of early Christianity, and then adds that Lucian nonetheless] knew that the Christians were unbelievably generous with their money and preferred to be open-handed rather than inquire too closely into the recipients.24

Charity, then, even to the point of somewhat indiscriminate handouts, was the center of early Christianity’s engine. We talked about the Great Commission of Jesus in the Gospels a moment ago – that mandate for worldwide proselytization. This proselytization happened during the 100s and 200s and beyond through the energy and diversity of Christian missionaries. Christian missionaries worked in local vernacular languages. They wrote songs and hymns in these languages so that the predominately illiterate laity could be introduced to the central ideas of Christianity. To slide back into doctrine for just a moment, the Book of John shows Jesus washing the feet of all of his Apostles, and then saying, “if I, your Lord and Teacher, have washed your feet, you also ought to wash one another’s feet. For I have set you an example, that you also should do as I have done to you” (John 13:14-5). Early Christian ministers seem to have taken this directive seriously. In the plutocratic Roman Empire, egalitarianism was a positively magnetic idea. Portions of the general epistles that we didn’t look at emphasize that the poor are rich in faith (Jas 2:5), and that the rich will be brought down like dying flowers (Jas 1:9-10), sentiments which surely appealed to moneyless converts tired of being regarded as untouchables.

Having read so much leading up to Christianity, we can draw some contrasts. The warriors of Homeric and Virgilian battlefields square off with long, vainglorious recitations of their formidable genetic and divine lineage. The emperors and kings of the ancient world, in their public messaging campaigns, often did something similar, Assyrian kings cataloging their brutal military victories, Macedonian warlords trumpeting the legitimacy of their newly minted dynasties, and Roman Emperors telling the world of their divine backgrounds and unprecedented grandeur. Religious officials of the ancient world, as well, could live in cocoons of privilege. The Delphic Oracle and the compound at Eleusis, the high priesthood of Jerusalem and the Roman Pontifex Maximus – these were positions that were either passed down by families, appointed by a ruling magistrate, or both, and they carried with them a cachet of exclusivity and entitlement. Christianity, at its inception, sought dissolve inherited privilege, horded wealth, and personal pomposity and reduce all humanity to an equal status as subordinate to a single god.

This new, emphatic egalitarianism spoke, with piercing clarity, to the Roman world. In the Gospels, in one of the greatest short narratives ever written, Jesus tells a group of temple officials about to execute a woman, “Let anyone among you who is without sin be the first to throw a stone at her” (John 8:7), his words simultaneously a statement about human fallibility and a razor sharp challenge to anyone conceited enough to stick their neck out. The words of Peter, according to tradition Christianity’s first Pope, are milder in the Book of Acts, Peter simply saying, “God has shown me that I should not call anyone profane or unclean” (10:28), Peter’s words underscoring the uniformity and essential dignity of every human being.

Whatever passage we choose out of the New Testament to counsel us toward modesty – and there are many – the actual ecumenism of Christian missionary work had a far reaching effect in the first century. A conversion, suddenly, could exalt an individual believer to a status the same as that of any other believer. As historian Peter Brown writes, conversion

opened a breach in the high wall of classical culture for the average man. By ‘conversion’ he gained a moral excellence which had previously been reserved for the classical Greek and Roman gentleman because of his careful moral grooming and punctilious conformity to ancient models. By ‘revelation’ the uneducated might get to the heart of vital issues, without exposing himself to the high costs, to the professional rancours and to the heavy tradition of [an] education in philosophy.25

Ancient Greek texts describe wealthy people as chrestoi or beltistoi – in English, “good ones,” or “best ones.” They describe the poor as poneroi or kheirous – “bad ones” or “worse ones,” with clear moral values attached to different income brackets. Christianity worked to smash these associations.26 As conversion and revelation could happen to anyone, anywhere, suddenly the provinces were as likely a seedbed of great religious teachers as the capital. The province of Cappadocia, the mountainous region where the Anatolian peninsula attaches to Syria, was a backwater during most of Roman history. But with the spread of Christianity, Cappadocia was as good a place as anywhere to be from, and over the course of the fourth century, it produced some of Christianity’s most famous bishops. Christianity washed away some of the classical world’s old hierarchies of provenance and prestige. And in its earliest days, the tiny core of two or three dozen Jews who spread its messages did something that other sectarian groups within Judaism – like the Pharisees, Sadducees, and Essenes – had never done. This was teaching the earliest Jewish Christians that in spite of their storied genetic lineage, they were still just human beings like everyone else – human beings that would be wise to operate carefully in the dangerous Roman world, and in the mean time, to open the church doors to anyone who wanted to come in.

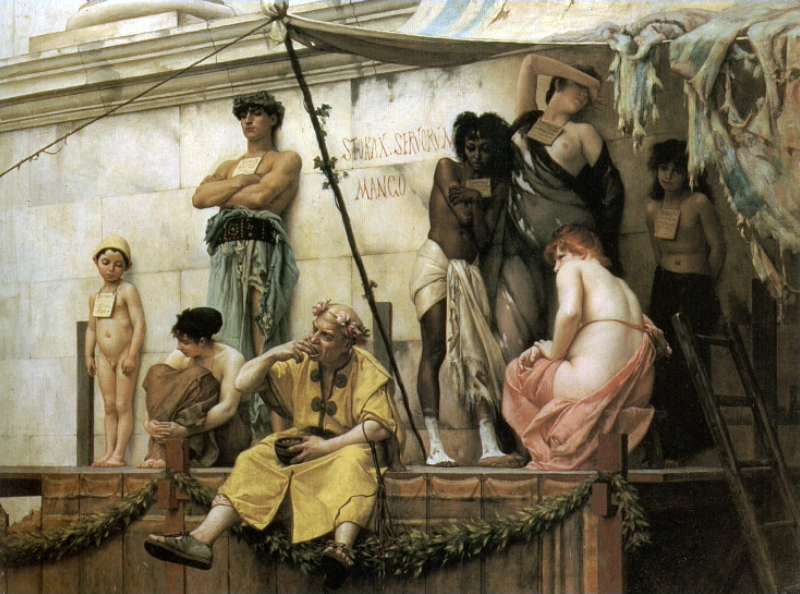

Gustave Boulanger’s The Slave Market (1886). Early Christianity’s egalitarian attitude toward slaves and legitimization of slave marriages was one of the new religion’s most farsighted and astounding contributions to history. This democratic sensibility pervades the general epistles and greater New Testament.

The year 250 CE has come up a couple of times in this episode – it was around this year that Origen, an older man, was writing his famous defense of Christianity, Contra Celsum. The year 250 was a low point even within Rome’s long third century crisis, as leadership disputes and various external forces nearly destroyed the empire. The Emperor Decius, a well known persecutor of Christians, was on the throne, and in fact this emperor’s torture of the theologian Origen is thought to have led to the end of the theologian’s life. But in terms of causing human suffering, the minority persecutions of Decius paled in comparison to the importance of what historians call the Cyprian Plague, an epidemic that wrecked the Roman economy and military between about 249 and 262, dissolved much of the frontier garrison structure, limited the longevity of all Romans, including emperors, and thus invited a greater whirl than ever of would-be rulers to war with one another for the throne. It’s a platitude to say that a hard rain brings people into church, though it’s worth emphasizing that inhabitants of the Ancient Mediterranean must have badly needed a warmhearted worship community and hope for transcendence in the 250s, as plague victims rotted in streets and ragtag factions fought one another for the sake of this or that would-be emperor. But Christians were busy with far more than singing hymns and praying for deliverance at this juncture of history. They were doing stuff. A lot of stuff.

In the year 251, when the Emperor Decius was killed in battle up in modern day Bulgaria, his son Hostilian began a very short reign of less than six months. Before many statues could go up to the new emperor, if any did at all, he died – likely of plague, and his co-emperor didn’t survive him by much longer. As the Cyprian plague grew, the simplest operations of the Roman emperor – elevating and sustaining an emperor, had broken down. But throughout the provinces, and especially in the City of Rome, Christian organizations had built an infrastructure for charity work that seems to have been highly resistant to the calamities that the empire faced. In 251 – again the second year of Cyprian Plague, and yet another year of multiple, short-lived emperors on the throne, the Christian church organization in the city of Rome alone had an impressive financial framework. From its common treasury, according to records, it supported a bishop, “46 presbyters, 7 deacons, 7 subdeacons, 42 acolytes, and 52 exorcists, readers and doorkeepers.” The financial support of a professional clergy is to be expected, of course, but what’s more striking is what else the Roman church was able to do – it fed and supported a population of 1,500 widows and those unable to work, and the number of wards of this church grew as a flood of persecuted bishops came in from overseas, having been threatened or harmed by the Emperor Decius’ persecutions.28

Over the course of the third century, this stable, ideologically motivated charity work, without a doubt, was one of the greatest reasons for early Christianity’s growth. By the third century, which saw Christianity growing at an even greater rate than before, the Christian churches had been set up as charitable institutions for a long time already. The Carthaginian theologian Tertullian, around the year 197, wrote a work called Apology for the Christians which endeavored to lay out, in Latin, the basics of what Christianity was all about. In this book, Tertullian writes,

I shall at once go on, then, to exhibit the peculiarities of the Christian society, that, as I have refuted the evil charged against it, I may point out its positive good. We are a body knit together as such by a common religious profession, by unity of discipline, and by the bond of a common hope. . . Though we have our treasure-chest, it is not made up of purchase-money, as of a religion that has its price. On the monthly day, if he likes, each puts in a small donation; but only if it be his pleasure, and only if he be able: for there is no compulsion; all is voluntary. These gifts are, as it were, piety’s deposit fund. For they are not taken thence and spent on feasts, and drinking-bouts, and eating-houses, but to support and bury poor people, to supply the wants of boys and girls destitute of means and parents, and of old persons confined now to the house; such, too, as have suffered shipwreck; and if there happen to be any in the mines, or banished to the islands, or shut up in the prisons, for nothing but their fidelity to the cause of God’s Church, they become the nurslings of their confession.”29

Few writers, either Christian or pagan, believed that this was a faultless system.30 But what Tertullian records here, theology entirely aside, is a remarkable and robust charity organization, something that I think is of intrinsic interest in and unto itself. Christianity did not invent charity, nor charitable organizations. One of the more famous public acts of charity in antiquity was that Roman Emperors had spurted out donatives to their troops and thrown games and parties upon ascensions with various giveaways, but that practice was sporadic. Charity is widely advised in the texts of the Ancient Mediterranean and Near East – of course it’s always been around, and we’ve seen admonitions for charity from Ancient Egyptian wisdom literature onward, with Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics and Cicero’s On Duties offering especially emphatic instructions for charitable giving.31 In Imperial Rome, public works projects like aqueducts, roads, fountains, libraries, and the grain dole were all free or highly discounted, and various scaled payment plans existed for hospitals, baths and toilets, with soldiers and slaves often paying nothing. Private philanthropic organizations also helped people with burials, food, and cash handouts, and economic largesse, both public and private, was a part of Roman society before and after Christianity.32 Granted, the provinces were at times at the mercy of rapacious Roman governors, but it’s still important to acknowledge that however much Roman society could be stratified, some resources for basic sustenance were available to the poor and needy in many of the Empire’s main thoroughfares.

In emphasizing that charity was a principal part of Christianity’s reason for expansion, then, we shouldn’t imagine that Christian worship centers were solitary beacons of light and giving in an otherwise entirely pitiless world. Instead, to return to the awful decade of the 250s, it’s better to say that the more dysfunctional the Empire became, the more Christian alms-giving became an important potential resource to the average poor person on the street. If this poor person happened to convert, then this swelled the ranks and coffers of the Christian philanthropy engine, which in turn offered a greater reach toward more converts and contributors. In this way, Christian conversion was directly encouraged by the social and welfare systems of the Roman Empire grinding to a halt. And it didn’t hurt that the church’s canonical rhetoric encouraged the power of endurance through strife – as we heard earlier, the later epistle of James advises, “whenever you face trials of any kind, consider it nothing but joy, because you know that the testing of our faith produces endurance” (Jas 1:2-3). As the third century lengthened, just as the individual Christian grew in conviction beneath the adversity of a skeptical world, the broader church only became stronger as state institutions decomposed under the press of leadership disputes and pandemics. To a devout believer, it all must have seemed pretty providential. [music]

The General Epistles, Theological Polemics, and the Formation of Roman Catholicism