Episode 84: Manichaeism

After 300 CE, Manichaeism spread quickly from its origins in modern day Iraq and Iran. Recent archaeological discoveries have finally allowed us to learn about it firsthand.

| Read Transcription | References and Notes |

| Episode Quiz | Episode Song |

| Episode on Spotify | Episode on Apple Podcasts |

| Previous Show | Next Show |

Manichaean texts from Turpan and the Faiyum Oasis

Gold Sponsors

John David Giese

ML Cohen

Silver Sponsors

Chad Nicholson

Francisco Vazquez

John Weretka

Lauris van Rijn

Patrick Radowick

Steve Baldwin

Mike Swanson

Sponsors

Alejandro Cathey-Cevallos

Alysoun Hodges

Amy Carlo

Angela Rebrec

Benjamin Bartemes

Brian Conn

Caroline Winther Tørring

Chloé Faulkner

Chris Brademeyer

Chris Tanzola

Daniel Serotsky

David Macher

Earl Killian

Henry Bakker

Janet Y.J. Chen

Jeremy Hanks

Joshua Edson

Kyle Pustola

Laurent Callot

Leonie Hume

Mark Griggs

Natasha Worle

Oli Pate

Anonymous

Anonymous

Rod Sieg

De Sulis Minerva

Sebastiaan De Jonge

Sonya Andrews

Steven Laden

Sue Nichols

Susan Angles

Tom Wilson

Verónica Ruiz Badía

If the contemporary world’s major religions were an asterisk that stretched through space as well as time, Mani, who spent most of his life just down the Tigris River from modern day Baghdad, would be at its center. Mani lived and worked at the exact moment that Christianity was beginning to explode in growth and diversify into different branches of Gnosticism, while it simultaneously solidified in the tracts of early Catholic bishops. Mani lived when a new Persian regime was continuing to nurture the old Central Asian mainstay of Zoroastrianism, when trade and general population expansion were bringing Silk Road goods from ancient commercial hubs in the northwestern part of present day China, through Samarkand, then through the Mesopotamian capitals, and into the eastern provinces of the Roman Empire, and from there, all over Europe and the Mediterranean. Mani declared himself to be the final prophet of God, nodding in deference to earlier figures like Jesus, Buddha, and Zarathustra, and he did all of this a little less than four centuries before Muhammad, after doing some considerable cleanup work to what we might call generic Eurasian monotheism, did the same thing 800 miles to the southwest, in Mecca.

Mani, then, was working at the intersection of all of the dominant world religions today, just as they were in the process of slowly assuming their present forms. Manichaeans encountered early Christians of all variations – most famously, Saint Augustine was a Manichaean prior to becoming perhaps the most famous theologian in Christianity after the Apostolic period. But Manichaeans also brushed shoulders with Buddhists and Hindus in the east, they lived and worked alongside with Zoroastrians throughout the vast stretches of the Persian Sasanian Empire, and later, they shared marketplaces, wells, and foodstuffs with the earliest Muslims. If we think of the transmission of theological ideas not in the ancient way – in other words this man had this true complete revelation, and passed it onto this man, who passed it onto these two men – if we put that aside, and think of the transmission of theological ideas in terms of chemistry, then, in Mani’s lifetime, history drove an unprecedented variety of religious reagents into the same place during the same centuries. Some of the solutions produced by this general mixture – Catholicism and Islam – crystallized through the operations of religious institutions, but while everything was swirling together, Manichaeism itself perhaps represented the most inclusive and generic version of what was in the beaker of third century Eurasian theology. As we’ll see later in this show, this was exactly what Mani intended to do – to fuse the theology of Europe, North Africa, Central, and East Asia into one complete system.

Manichaean Primary Sources

Much of what we learned about Gnosticism in the previous program is as true about Manichaeism. Both are as remarkable and important as they are seldom understood or discussed today. Both, for a long time, were mostly known by means of the partisan tracts of Christian chroniclers. But both, fortunately, through archaeological discoveries, yielded up large masses of primary texts during the twentieth century – Gnosticism most famously the Coptic language texts discovered at Nag Hammadi in 1945, and Manichaeism, through German expeditions in northwestern China between 1902 and 1914, and discoveries in Egypt in 1929. Scholars were certainly interested in Manichaeism prior to the archaeological discoveries of the previous century, but their main source beyond the Christian commentaries was a tenth-century compendium produced by a scholar named Ibn al-Nadim during the early Islamic Golden Age in Baghdad. However, this was an academic and bibliographical source, rather than one written by a practitioner of the religion.1 So what made the excavations and discoveries of Manichaean texts so significant during the twentieth century was that these were our first opportunity to hear what Manichaeans themselves had to say about their beliefs.However, Manichaean texts discovered in the previous century and a half have not had a speedy journey into modern printed translations. The German Expedition of 1902-1914 took place at a site near the town of Turpan in China’s autonomous region of Xinjiang, a vast and arid region of the country in the extreme northwest, whose name means “new frontier.” Xinjiang, which borders Kazakhstan, Kyrgystan, Tajikistan, and parts of the unstable borderland between India and Pakistan, is home to the world’s largest Uyghur population, not to mention a number of other ethnic groups semiautonomous within the region. And in ancient times as well as in the present, Xinjiang, and Turpan, where a Manichaean library was discovered, sit on the cusp between larger regional powers, absorbing their resources and influences, but also, due to the area’s remote location and in places impassible terrain, being often left alone to develop their own cultural identity. It’s not too surprising, then, that the Manichaen texts discovered during what archaeologists call the Turfan Expeditions, were written in a variety of ancient languages – Middle Persian, Parthian, Sogdian, Tocharian, and Uighur. While these languages had been deciphered by the twentieth century, they were nonetheless obscure territory compared to, say, Koine Greek or Biblical Hebrew, which anyone in a divinity school in 1910 with a decent bowtie could translate for you. When it came to Middle Persian, and Parthian, and other ancient languages of Central Asia – these were, and still are, highly specialized territory.

In the inter-war period, though, another trove of Manichaean documents emerged – these from a site much more commonly associated with Early Christianity. In 1929, in the Faiyum Oasis, 250 miles north of Nag Hammadi, and just 70 southwest of downtown Cairo, some workmen digging for fertilizer unearthed a chest full of papyrus manuscripts, still safely covered and preserved by the dry climate of the region. Like the Nag Hammadi library, the texts were in Coptic, but just as the Nag Hammadi Coptic texts were largely translations of Greek originals, the manuscripts found in the Faiyum Oasis were Coptic translations of Syriac originals. Syriac, a dialect of Jesus’ own Aramaic language, was the language spoken by the prophet Mani himself, and the one in which he wrote his scriptures. Scholars date these Egyptian texts to around 400, making them a bit younger than the manuscripts of the Nag Hammadi library, but it’s likely that their burial and preservation by ancient Egyptian Manichaeans was intended to protect them from Catholic efforts to destroy other branches of Christianity and consolidate hegemony in the aging Roman Empire. Unfortunately, while a few of these early Manichaean texts were processed and translated prior to 1940, they were subdivided between Berlin and London from the beginning, and World War II delayed their being printed and translated for forty years.

There were other Manichaean codices discovered in Egypt, too – a remarkable and tiny manuscript called the Cologne Mani-Codex with handwritten letters just a millimeter in height, which was once worn as an amulet and became available in published translations in the 1980s. Elsewhere, in an ancient Roman settlement about 200 miles west of Luxor and the Valley of Kings, researchers working during the 1990s began uncovering Manichaean manuscripts that had been used in a community in the 300s, allowing them to see Manichaeism in action in a Roman province. This fourth body of texts, from the Dakhla Oasis, at the geographical center of modern day Egypt, included letters and other miscellaneous documents, providing a view of how Manichaeans lived and worked alongside other Christians as Catholicism continued to take shape in the later Roman Empire.

The story of scholarship on Manichaeism, then, is a bumpy one. Everyone wanted to know about this ancient theology. And everyone understood what I told you earlier – that it had been a pervasive religion, born in the early 200s near Baghdad, that pervaded the Roman Empire and Middle East until later push backs from Catholicism and Islam. But the difficulty of the primary sources discovered between 1904 and 1914, followed by the flare ups of the World Wars, caused the Manichaean texts from Turpan to continue to be off limits to curious academics and general readers, and it has only been in the past three decades or so these many of these materials have been made accessible in responsible translations. While we have quite a few Manichaean primary texts now, Manichaeism remains a subject that most of us pass through on our way to something else, rather than studying extensively for its own sake. And in this episode, I’m happy to say, we’re going to look at some Manichaean primary texts in detail. But first, I think it will be helpful to have a general overview of Mani himself and the religion that he promoted. So let’s begin our journey into Manichaeism at the most logical point we can – with the prophet Mani, who is thought to have lived from 216 until about 276. [music]

The Life of Mani

Mani’s Youth

Mani, the architect of Manichaeism, is said to have been born on April 14, 216 in Ecbatana, or modern day Hamedan, Iran. Ecbatana, a city that sat at over 6,000 feet above sea level, was at this point the capital of the Parthian Empire, an Empire nearly 500 years old by the year 216. To the west, in Rome in 216, the Severan dynasty was at its rocky midpoint, with the Emperor Caracalla on the throne. As the future prophet Mani took his first breaths, the Roman Emperor Caracalla was in the midst of spearheading a large scale but lackluster campaign against the Parthian Empire. Between 216 and 217, Caracalla’s forces made their way through the northern fringes of Parthian territory, attacking communities and strongholds up near the far north of the Tigris, but not venturing toward the real Persian seat of power in the highlands beyond the Zagros Mountains. The Roman Emperor Caracalla, spending the winter of 216-217 in Anatolia, wrote to the senate that he had defeated Parthia. Parthia disagreed. After Caracalla was assassinated in April of 217, his successor Macrinus had to deal with the fall out of Caracalla’s unwise hostilities. During the summer of 217, Macrinus fought the armies of the Parthian king Artabanus IV at the Battle of Nisibis, near where modern day Syria, Turkey, and Iraq come together. The Romans lost, and Macrinus had to pay sizable reparations to the Parthian King, only to be killed the next summer as the next Roman Emperor, Elagabalus, came to power through the efforts of his supporters. The leaders of Rome’s Severan dynasty tended not to die of natural causes.As this next Roman emperor, Elagabulus, unpacked his boxes in the Roman capital and made himself comfortable in the throne room, the prophet Mani was about two years old. And in young Mani’s home territory of Parthia, all was not well. The Parthian Empire, while it had defeated Rome, had nonetheless suffered heavy casualties during the summer of 218. Parthia, too, had not been without succession disputes, the Parthian King Artabanus IV having usurped the throne from his brother Vologases VI. While the Parthian King Artabanus IV had defeated the Roman invasions, he still ruled over an unstable kingdom, made all the more unstable by a charismatic leader, 400 miles to the southwest in the satrapy of Fars. This leader was Ardashir, or as he would later be called, Ardashir I. As the 220s progressed in modern day Iran, Ardashir went all in on a bid for supreme executive power, and in the spring of 224, Ardashir’s forces met Artabanus IV’s forces at the battle of Hormozdgan. The Parthian King Artabanus IV lost, and the year 224 would forever after be marked as the year that ended ancient Iran’s Parthian dynasty – by that point nearly 500 years old – and began its Sasanian dynasty, which itself would last 400 years, and in the early part of which, Mani himself would have a major role to play. If you learn just one date in this program, by the way, 224 CE is a good one to walk away with – the year in which the Parthian Empire ended and the Sasanian Empire began.

By the time the prophet Mani was eight, then, he had lived to witness one of the most pivotal occurrences in world history – the twilight and fall of the storied Parthian Dynasty and the beginning of the Sasanian Dynasty, which would endure until 637, and its greatest extent, balloon to nearly the size of the Achamenid Empire under Darius the Great. Mani witnessed the very beginning of his epoch of Persian history, and scholars think Mani’s family likely had kinship with the defeated Parthian royal dynasty rather than the new and ascendant Sasanian one.2 Whatever his family’s reason for doing so – and it may have been for purposes of political security, Mani and his parents moved to Ctesiphon, the traditional winter capital of the Persian heartland, about 20 miles south of Baghdad along the Tigris, where Parthian and Sasanian aristocrats could duck out of the harsh weather of the Iranian steppe and enjoy Mesopotamia’s milder versions of January and February.

Over in balmy Ctesiphon, Mani’s father became involved with a sect of Jewish Christians called the Elcesaites whose creed included vegetarianism, the abstention from alcohol and sex, and other ascetic behavioral regulations. And at about the age of four, Mani himself joined this group, where he remained for the next twenty years, presumably soaking up an Eastern flavor of Jewish Christianity with elements of Gnostic mysticism. We learned in the previous program that one strand of the Gnostic movement was highly interested in twins. This strand is what scholars call Thomas Christianity, and it centers on that notion that each of us has a celestial twin which is the true, spiritual version of ourselves that we might meet after death and at moments of divine inspiration. Mani reported having seen his celestial twin at the ages of 12 and 24, and he seems to have had a degree of theological individualism too unruly for the Elcesaites’ sect.3 A fragmentary autobiography attributed to Mani records how while he lived in the Elcesaite commune, “I was protected through the might of the angels. They also brought me up by means of the visions and signs they showed me, which were short and very brief such as I could bear.”4 Mani’s visions, once shared with the rest of the commune, reportedly impressed some members while alienating others, even leading some of the other members to attack him.5

Mani Begins the Religion

Mani’s later departure from the Jewish Christian faction his father had joined was spurred by a falling out due to Mani’s personal evolution in beliefs. As you know if you’ve listened to the present season on Early Christian history, one of the main dilemmas of the new religion – meaning Christianity – was how close it ought to be associated with and related to its Jewish roots, and the scrolls of the Old Testament. This schism shows up in the New Testament Book of Galatians (2:11-14) with a fierce confrontation between Peter and Paul in Antioch, with Paul upbraiding Peter for holding himself aloof from Gentiles. By the time Mani came of age two hundred years later, a wide variety of Christian perspectives had emerged on the religion’s Jewish roots, from the outright rejection of Judaism evident in a number of Gnostic texts, to the commonplace sects of Jewish Christians, like that of Mani’s father, and everything in between. Mani, by the age of 25, had taken a position on this debate, and he sided with the Gnostics in his desire for a version Christianity mostly unhitched from Judaism.6 For this reason, and out of what seems to have been an unusually ardent desire to travel and proselytize, Mani left his Jewish Christian sect at the age of 25, and his father came with him. The Parthian Kingdom had turned into a Sasanian one, and Rome, gnawing away at itself in the heart of the Crisis of the Third Century, was no longer harrying the western and northern fringes of Persian territory. To energetic young Mani, it must have seemed a time in which anything was possible.Mani, his father, and a few likeminded spiritualists crossed back over the Zagros Mountains and went to the far northwest of modern day Iran, near the Armenian border. There, in a town called Ganzak, they met with the founding Sasanian Emperor Ardashir I, who seems to have been persuaded that Mani was a person of considerable spiritual gifts. Ardashir may have given Mani an endowment or some other offering that aided Mani’s ability to travel, because the next portion of Mani’s biography involves a great deal of globetrotting. He went through the Central Asian region of Turan to India, where he became familiar with Buddhism and, according to scraps of biography that survive about him, where he held various rulers and locals spellbound with his teachings. An autobiographical summary of his travels during this period paint a picture of a figure who is half Jesus Christ and half Saint Paul, dashing around from land to land and separating light from darkness just as he debates with adversaries of various regions and formalizes the creeds and practices of his new religion.7 In the year 242, when the first Sasanian Emperor Ardashir passed away, and his son Shapur I took the throne, Mani returned to Persian territory, and then went on to Babylon, and from there, downriver to the towns and settlements along the lower Tigris and Euphrates.

Like so many successful religious leaders, Mani knew the importance of political alliances, and he made a very fruitful one with the second Sasanian Emperor Shapur I. As scholars Iaian Gardner and Samuel Lieu write,

Shapur I intended to expand the Iranian Empire in all directions and to strengthen it internally at the same time. Mani seemed to him to be the very man for this purpose. His belief was especially suited to the East because of the elements which either came from Buddhism or were confirmed by it. The syncretistic self-awareness which was characteristic of Mani’s perception of himself, and which made him consider himself to be the perfection and fulfillment of the three great religions, Buddhism, Zoroastrianism and Christianity, would allow him to appear as a spiritual cement for the Iranian Empire.8

If the partnership between Mani and Shapur I is accurate, we have here a fascinating example of a Persian king’s farsightedness. Zoroastrianism was the ancient faith of modern day Iran – it was in some ways the logical choice of a newly minted regime that wanted to flourish and expand. Mani presented Shapur I with a unique opportunity to fund a religious functionary who understood and could pay deference to the Zoroastrian, Christian, and Buddhist ideologies all resident in his empire. In turn, Shapur provided ambitious young Mani a willing imperial patron to validate his brand new religion. Manichean historians themselves recorded the exchange between the Emperor Shapur I and Mani as a triumph for the Mani. A 10th-century Islamic source, attests that “[W]hen [Shapur] saw [Mani] he was impressed and Mani grew in his estimation. (Indeed) [Shapur] had been resolved to having Mani slain, yet when he met him he was overcome by admiration and delight, asking Mani what had brought him to him and promising a further audience with him.”9 We have no idea if this story is true – tales of prophets and philosophers mesmerizing slack-jawed monarchs were common in the ancient world – but it may indeed record a cordial working relationship between the Sasanian throne and the leaders of Manichaeism by the mid-200s.

Mani’s Later Years

Shapur I was on the throne for thirty years – between 240 and 270, during which Mani’s home base was Ctesiphon – again just a day’s march southeast of modern day Baghdad along the Tigris. Mani was a part of the king’s court, where one imagines a shrewd pragmatism must have driven his theology just as much as spiritual vision. We’ll talk about this theology a great deal in a moment here – but for now let’s finish up with Mani’s biography. Though Mani sought to convert the emperor himself to his new religion, Shapur I resisted, remaining a Zoroastrian until his death in 273. The next Sasanian king only ruled for a year, but his successor, Vahram I, did not prove as friendly to Mani as previous Sasanian rulers had. Vahram I seems to have taken objection to Mani’s claims to being divinely inspired. Additionally, while we don’t have much to go on in terms of Mani’s final years, Vahram I may have simply been mistrustful of the founder of a new religion occupying a position of political power in the Sasanian Empire to begin with. Mani, over the course of his thirty years under Shapur, had established priesthoods and an entire institution with its own sphere of influence and financial activities, and that institution had as much in common with the alien ideologies of Christianity and Buddhism as it did with good old Persian Zoroastrianism. According to one Manichaean source in Middle Persian, Mani was objectionable to the new Sasanian emperor because Mani pacificism and monkish behavior were out of step with what was expected of any self-respecting nobleman, who hunted animals and fought wars when it was required of him.10 More probably, the new Sasanian king felt threatened by the dauntless old prophet. A text called the Šābuhragān, attributed to Mani himself, doesn’t exactly suggest that Mani was a humble or self-effacing person. Let’s hear some of what Mani himself purportedly had to say about his faith – this is from a book called Manichaean Texts from the Roman Empire, published by Cambridge University Press in 2004. In this text, Mani professes that,This religion. . .chosen by me is in ten things above and better than the other religions of the ancients. Firstly: The older religions were in one country and one language; but my religion is of the kind that it will be manifest in every country and in all languages, and it will be taught in far away countries. Secondly: The older religions. . .when the leaders had been led upwards, then their religions became confused and they became slack in commandments and pious works. . .However, my religion will remain firm through the living (. . .tea)chers, the bishops, the elect and the hearers; and of wisdom and works will stay on until the end. . .[M]y wisdom and knowledge are above and better than those of the previous religions.11

Mani presents Vahram I with a drawing in this 16th-century painting by Ali-Shir Nava’i from Tashkent.

Mani was imprisoned, and after about a month, he died in confinement, in either the year 276 or 277.12 A Manichaean elegy that records his death draws a portrait of a thoroughly vulnerable, human victim, weeping and bidding farewell to friends, family, and followers, resolute but nonetheless tragic in his early demise.13 Earlier, we talked about the variety of manuscripts we have recording the Manichaean tradition – a panorama of texts generally in Coptic and Syriac in former European and North African sites, and in Middle Persian, Parthian, Sogdian, Tocharian, and Uighur in modern day China. A later text, written in Parthian but discovered in China, uses discernibly Buddhist terminology to describe Mani’s passing, telling us that Mani “left the whole herd of righteousness. . .orphaned and sad, because the master of the house had entered parinirvana.”14 This realm – parinirvana – is in Buddhism that state of transcendence from the wheel of reincarnation, a doctrine that we also find in Pythagorean, Orphic, and Platonic texts starting in the fifth and fourth centuries BCE. And the reference to entering parinirvana, I think, is a fitting end to our recap on Mani’s life – making him the only major religious figure I know of who partook in a Jewish and Christian prophetic tradition, centered his religion on a Zoroastrian dualism, and wound up in a Buddhist and Hindu afterlife. In the Manichaean calendar, the prophet’s death was a revered holiday, during which effigies of Mani were set up on a five-tiered platform called a bema, and he was worshipped as a martyr.15 [music]

Manichaeism and Gnosticism

Now that we’ve talked about Mani’s life, and how his religion was a product of the early Sasanian Empire during decades between 230 and 270, let’s talk about the religion itself. Manichaeism had a long and complex life, parts of its theology emerging later in Islam and then in the European Middle Ages, but we should begin by getting a sense of the religion as it emerged as an autonomous system during the life of Mani. Mani seems to have had both evangelical zeal as well as a capacity for theological system building that together created a complete religion that was doctrinally finished by the time he died. Manichaeism was, in a sentence, a fusion of Zoroastrianism and Christian Gnosticism, with a spirit of proselytism and emphasis on good works more like those that characterized early Christianity. Thus, as complicated as Manichaeism is to the newcomer, if you’ve reached this show having heard this past season on the New Testament, then Zoroastrianism, and then Gnosticism, Manichaeism should follow fairly easily.

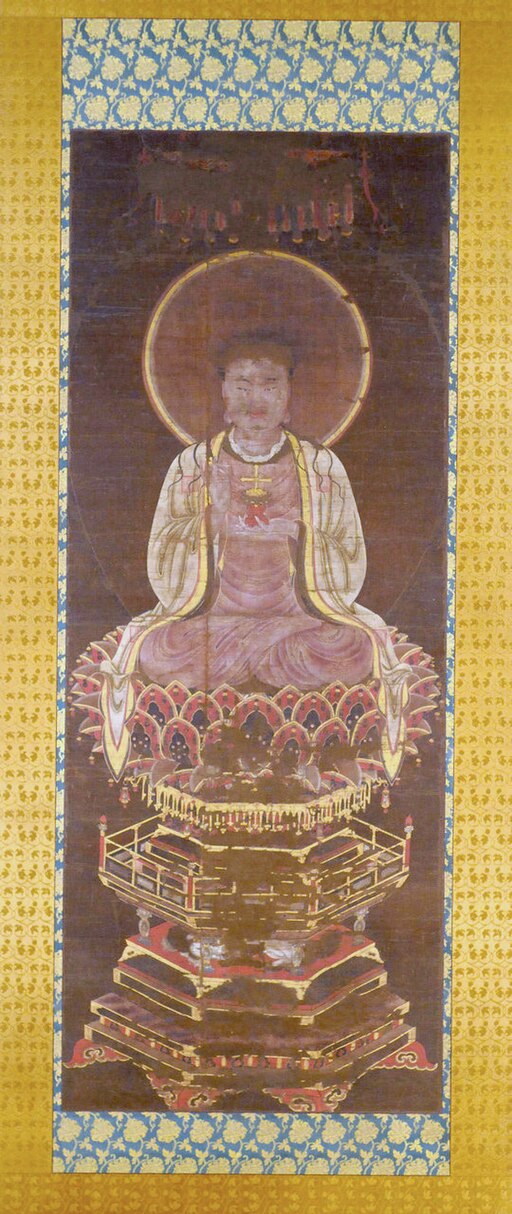

A detail from a 13th-14th century Yüen Dynasty painting of the Manichaean heavens (the full painting is featured later in this transcription). Manichaeans and Gnostics shared an affection for elaborately detailed writings and visual artwork on the subject of the heavens and those who dwelt there.

While Manichaeism has syncretic religious roots, it’s important to understand that a large part of the pie chart that makes up Manichaean ideology comes from Gnostic sects – sects that had a hundred or so year head start on the prophet Mani. Mani often, in the surviving Manichaean literature, describes himself as an apostle of Jesus Christ, and in so many of the Gnostic Nag Hammadi texts we looked at in the previous show, written in the second century CE, and the third, when Mani lived, dozens of apocryphal texts purport to be various gospels and testaments of Christ, using, as the ancient world so often did, a revered and beloved speaker to give voice to novel ideas. Mani, following the Gnostic belief in heavenly twins, believed that he’d received his own revelations from his celestial counterpart. The Manichaean doctrine of the twin, or didymus, or spouse, or syzygos in Greek, was a major part of its system. This doctrine, which itself seems to have been common in Syrian Christianity by the second century, was popularized not too far from where Mani lived most of his life in Mesopotamia. And in addition to a preoccupation with twins, Manichaeism shared Gnosticism’s penchant for creating elaborate catalogs of divine beings. The Manichaeans, like the Gnostics, proposed that a battalion of aeons, (more or less angels), and aeons of aeons surrounded the highest god. In general, if you’re reading an ancient Eurasian religious text which describes five things, each of which have five things, each of which themselves have five things (the number could be three or seven or whatever), you’re reading something with more Eastern and Zoroastrian than Greco-Roman DNA. The Book of Revelation, with its apocalypticism and its seven churches, seven lampstands, seven stars, seven spirits, seven torches, seven seals, seven trumpets, seven bowls, etc. etc., belongs to this eastern tradition, as we learned a few episodes ago.

Anyway, Manichean texts, following Gnostic writings like The Secret Book of John and the Three Forms of First Thought, propose that God’s first creation was a female archangel – one called the Mother of Life in Manichaean literature. This Mother of Life, like Gnosticism’s archangel Barbelo, then created a son – the eldest son of God, and thus Manichaeism shares a Trinitarian structure with Gnosticism. But Gnosticism was only one of the two pillars of Mani’s belief system.

While Christianity and its branches were a relatively new presence in the aging Parthian Empire, Zoroastrianism was old and well established, dating back to at least the sixth century BCE, if not centuries before this. And from Zoroastrianism, Mani took another cornerstone of Manichaeism – the old Zoroastrian notion of two primary gods – one good, and one evil. In our past two episodes we have seen two different kinds of theological dualism – what we call vertical dualism, and horizontal dualism. In vertical dualism – like Zoroastrianism’s – there are good and evil deities, and everything – the spiritual world and material world alike, are sundered down the middle into forces that are good, and forces that are evil. That’s vertical dualism. In horizontal dualism – like Gnosticism’s – the spiritual realm is higher and better than the material realm, which is debased and spurious, and a horizontal line divides the two. Manichaeism is a system that uses both forms of dualism – vertical, and horizontal. At Manichaeism’s core is the Zoroastrian notion that good and evil are vying with one another, and that in the end, good will emerge triumphant. Because Manichaeans believed in both spirit vying with matter and good vying with evil, then, Manichaeism is a religion invested in the idea of conflict at virtually every tier of the cosmos, including the very elements of light and dark that make up every human being.

So, we’ve gone over some of the Gnostic and Zoroastrian elements of Manichaeism – to simplify things greatly, the way in which Manichaeism harvested both a horizontal and vertical dualism from these earlier religions. It’s important to understand that in Ancient Iraq during the 200s CE when Mani lived, all of these ancient theologies were in flux, alongside others. If we diagram the creation stories and apocalyptic doctrines of the various strands of Christianity, Gnosticism, Zoroastrianism, and everything in between that we find in ancient texts, we have an almost infinite variety of celestial org charts, prophecies of clashes between dark and light, hundreds of different versions of Jesus, dozens of different doctrines of salvation, and as many interpretations of what the crucifixion meant – a colorful mandala of religious activity resulting from the fusion of Mediterranean and Eastern belief systems and the intensely scribal and bookish culture of Second Temple Judaism and beyond. As endlessly complicated as all of these hybrid theological systems can be, in a way there is something incredibly simple about them. The Ancient Mediterranean and Near East had always been syncretistic, mixing and matching deities and rebranding them as immigrations and emigrations took place. Hesiod’s Theogony can be read as an allegory for just this process – a new generation of gods usurps an old one, uncountable gods and demigods springing up, their divine fertility a metaphor for the fecundity of the ancient imagination of the Eurasian and North African land masses. Against this relaxed syncretism, though, there came a newer force – the desire to institutionalize and codify doctrines. We see this in Christian history from its very earliest documents – the Pauline epistles. What distinguishes Mani is that he seemed to possess both tendencies we see throughout the Fertile Crescent during this long period – in other words not only the desire to be a visionary, but also to crystallize and institutionalize doctrines. So now we’ve talked about Manichaeanism’s right and left legs – Gnosticism and Zoroastrianism. And before we get into some of the main surviving Manichaean texts, then, I want to review, as best we can, using a whole lot of different sources, the history of the universe according to Manichaeism. [music]

Manichaean Cosmic History

The First Age

The central story of Manichaeism was often summarized by the phrase “of the two principles and the three times.”16 The two principles were good and evil, or light and darkness. That part’s easy. The three times, however, will need some explanation. The three times of Manichaeism were: first, the period at the very beginning, during which good and evil did not know one another and first came into conflict; second, the middle period, as the earth was created and the conflict continued; and third, as the conflict continued further and humanity was created. Let’s talk about these so-called “three times” of Manichaean theology – the three central epochs of cosmic history that in ancient sources are attributed to Mani himself. I’m going to try and tell this as a short story, by the way – we’ll look at some of the texts a little bit later, but I think it will be useful for us to all get an amalgamated version of the central story of Manichaeism in our heads before we start exploring the history of the religion after the third century. So here is the story of Manichaeism.In the first epoch – the first of the Manichaean three ages – initially, the main Manichean god, or “Father of Greatness,” reigned in a dimension of pure light. This dimension was an effluence of the Father himself. With him, there in the realm of light, were various subdeities – the father was made of four attributes, which themselves were made of five elements. And the Manichaean father deity ruled over 12 aeons, three in each of the cardinal directions, each of whom ruled over an additional 12 aeons, forming a symmetrical blossom of divine light. Elsewhere, though, to the distant south, lived the King of Darkness, who himself reigned over five worlds, five dark kings, and five dark elements. While the light elements were light itself, wind, water, fire, and the living air, the dark elements were smoke, darkness, fire, water and wind – the churning components of falseness, lust, and strife. These were the two realms, and they did not know of one another. As a fragment of a lost Manichaean scripture tells us in regards to the dark and the light, “Each of them is uncreated and without beginning, both the good, which is the light, and the evil, which is darkness and matter.”17 Note, by the way, that is doctrine of the eternality of evil is Manichaeism’s main theological difference from Gnosticism, in which the evil demiurge Yaldabaoth is created as an accident, long after the central Gnostic deity called the Great Invisible Spirit – in Manichaeism, by contrast, good and evil gods both exist from the outset.

A Yüen Dynasty painting of the Manichaean heavens (13th-14th centuries.

Anyway, as time wore on, in this first age of Manichaean cosmic history, the realm of darkness, regrettably, became aware of the realm of light, and sought to invade it. Manichaeans wrote elaborate taxonomies about the architecture of the dark world and all of its subcomponents – in one text a cobweb of five storehouses, five rulers, five spirits, five bodies, and five states, ruled by the King of Darkness – a being with the head of a lion, the hands and feet of demons, his shoulders the heads of eagles, his belly like a dragon’s, and his tail like a fish’s.18 If you’re interested in demonology, by the way, and who isn’t? – Gnostic and Manichaean scriptures have a whole encyclopedia of lion-faced, snake-tongued, etc. etc. monsters to choose from. That’s an idiosyncratic feature of Manichaean texts – the catalogs or inventories of the dark world and the light world. But anyway, to return to the narrative of the three ages, and we’re still on the first., once the dark world had begun its great campaign against the forces of light and goodness, the Manichean light god then created the archangel called the “Mother of Life,” who in turn created a being called the “First Man,” the three being a Holy Trinity like that of Gnosticism’s Great Invisible Spirit, Barbelo, and anointed Son. And this “First Man,” in Manichaeism understood as the first born son of the highest god, was armed with five shields, or five sons, and he led the battle against the forces of darkness. In the resulting clash, all of the firstborn son’s own sons, or shields, were destroyed, and the son of god became devoured and enveloped by the darkness, so that the realm of dark was shot through with the shards of light. In the primal early history of the central Manichaean narrative, then, the figure called the First Man, or firstborn son of God, sacrificed himself to hinder the forces of darkness from swarming into the realm of light, and in doing so, he himself became entangled with darkness, and in turn caused a burst of fragments from the light world to pass into the realm of darkness. This, then, was the end of the first epoch – a finale which ended with the firstborn son of God, devoured in the world of darkness, but at the same time, poisoning that darkness with his divine radiance. Pretty awesome cliffhanger ending, if you ask me. From this crisis, the second era of cosmic time opened in the Manichaean story.The Second Era

The second era of cosmic Manichaean history began with new deities, and a rescue mission. The rescue mission was to recover the First Man and his five defeated sons from the realm of darkness. And at the helm of the rescue mission was a being called the Living Spirit. The Living Spirit, who is the son figure of this second era of Manichaean cosmic history, called out to the lost First Man, trapped in the realm of darkness. The lost first man responded back, and the great call and response which yoked the first two eras of Manichean history together themselves became gods. Knowing that the First Man of the first era was still alive, then, though lost in darkness, the Living Spirit – again the son figure of the second Manichean age – strapped on his arms and armor, and with the Mother of Life – that archangel figure of the first age – they descended into the abyss of the dark realm. There, the forces of light fought the forces of darkness, and as the forces of darkness were unsuccessful, their giant bodies toppled to the ground and became the physical matter of the universe.The Manichean account of the material universe’s creation, then, is the result of the violent contention in the depths of the dark realm, from which there fell the carcasses of monsters and demons that became the material world. This is quite similar to the creation story as we read in the Enuma Elish – Marduk defeats Tiamat and the materials of her corpse are used to build the world, and Ancient Babylon and its theological heritage were certainly part of Mani’s region. But the Manichaean tale of the earth’s ignominious creation was also driven by a desire to trace out the evil essence of the material world – we have to remember that horizontal dualism was a part of Manichaeism just as much as vertical dualism, and so the story of the earth being created from the cadavers of demons and monsters was also a means of explaining why the material world was so fallen and debased. Anyway, let’s continue with the Manichaean cosmic history of the three eras – we’re in the middle of the second era, with the rescue of the Firstborn Son from the dark realm, and the war out of which resulted the world’s creation.

The Living Spirit, once again the Trinitarian son of the second Manichaean period of the cosmos, fashioned ten heavens and eight earths out of his defeated foes, using his own five sons to bind the manifold realm of material creation together. These five sons each had territories to govern, variously ruling their share of the ten heavens and eight earths. In the Manichaean imagination, the sun and the moon were luminous entities made from the same essence as the world of light, whereas the stars and other planets were created from the darkness. The astronomical aspects of Manichaean thought – their beliefs in the sun, moon, and stars, are relevant to the third and final era of Manichean cosmic history.

The Third Era

One might think that with the world of darkness pummeled during the second era – with the dead remains of its demons and monsters tumbled down and turned into the world of matter, that light had triumphed, and time had come to its fruition with the victory of the forces of good. But in fact, the third period of Manichaean history was still to come, and this third epoch would result in further clashes between light and dark. At the outset of the third Manichaean era, the Manichaean deity created some more exalted gods – this time, a herald that dwelt in the sun and announced the third epoch of the cosmos, and a female deity called the Virgin of Light, who dwelt in the moon – a figure common in Manichaean iconography. And between these two new deities, straddling the span between the recently created sun and moon, was Jesus, or a figure who in Manichaeism is called Jesus the Splendor. And then followed the next – memorably weird – event in Manichaean cosmic history.

The Virgin of Light and her entourage in a 13th-century Yüen Dynasty painting. This figure, and her comrade the Ambassador of the Sun had a large role to play in the third cosmic age of Manichaeism.

In Manichaean cosmic history, from the fallen abortions of the female archons there came various beings on the earth, and later, Adam and Eve. Adam and Eve, in Manichaeism, are the son and daughter of a pair of demons called Saclas and Nabroel.20 But in Manichaeism, as in Gnosticism, humanity is not fundamentally evil. Though Adam and Eve were the children of a male and female demon, prior to their intercourse, the male and female demon had eaten the aborted fetuses that had showered from the female archons above, fetuses which had been engendered by the demons’ glimpse of the divine sun and moon, and so the gestation of Adam and Eve was filled with light, just as it was filled with darkness.21 In the third era, then, after the creation of Adam and Eve, Jesus, the bridge between the Ambassador of the sun and the Virgin of the moon, went to Adam to awaken him and tell Adam that he was not doomed to perish altogether in a world of falsehoods and greed and lust. But Adam was a product of his dual natures, and so he had intercourse with Eve, from which there descended the population of humanity, beings forever after in danger of entirely forgetting their divine essences. Mani’s own account of his birth in a codex attributed to him is consistent with this greater narrative about the tragedy surrounding humanity’s origins – the text records how Mani, in a divine vision at the age of 24, learned “how I was born into this fleshy body. . .and by whom I was begotten. . .how that came about, and who is my Father on high or in what way I was separated from him and was sent according to his will, and what command and instruction he gave to me before I clothed myself with this frame, and before I fell into error in this loathsome flesh, and before I put on its intoxication and its habits.”22

This, then, was the beginning of the human condition as it was understood in Manichaeism – both at a cosmic level with Adam and Eve, and at the individual level, with everyone ever born. We have a capacity for good and evil, like so many cartoon characters with an angel on one shoulder and a devil on the other. But we not only have a choice to make between righteousness and wickedness. Righteousness and wickedness are part of the fabric of our being, and the cultivation of righteousness means understanding our heavenly origins and resisting the pull of carnality. The prophet Mani himself claimed that he was the final Apostle, and that his revealed teachings would be the final edict of truth for all humanity, believing, as the Apostolic generation did, that he lived on the very cusp of the end times.

And speaking of end times, these three great eras of Manichaean time were thought, by Mani’s generation, to be just about over, with a combination of collective judgment and then apocalypse just down the road. The Manichaean doctrine of end times is as follows. Very bad people will be damned forever. Medium people will given a second chance via reincarnation. Good people will ascend upward into the Milky Way. Then time will end. Surviving Manichaean texts have variations of how this will happen, some fairly concise about the end times, others with extensive prophetic visions. A Manichaean homily called “The Sermon of the Great War” tells of an impending apocalypse like the ones we read about in Zoroastrian scriptures, Old Testament Prophetic Books, the Book of Revelation, the Qumran War Scroll of the Dead Sea Scrolls, and a dozen other pseudepigraphal books of the Bible – a colorful catalog of blood and explosions and angels and demons standard to Ancient Near Eastern apocalyptic writings.23 This sermon includes a trumpet sounding, swords being drawn, flesh being annihilated, the sun rising over corpse fields, the wicked punished and the good rewarded, and more of apocalypticism’s greatest hits, after which, as is also standard in apocalyptic texts, all lands will be joyously yoked under the teachings of the one true church and the one true god, and – in an apocalyptic passage more distinctly Manichaean, the material bodies of all humans will dissolve.

So that is the main cosmic history of Manichaeism – the story “of the two principles and the three times,” the two principals being good and evil, and the three times involving a series of rumbling and spectacular confrontations between them. Mani’s life was an addendum to this cosmic history, because when Mani died, the prophet’s passing came to mark the most important date on the Manichaean calendar, and his death was thought to be a substitution for Christ’s – a stopgap sacrifice until the real return of Christ, which would catalyze the aforementioned final judgment.

An abridged version of much of this entire narrative is set down in a psalm in a fourth-century collection discovered in central Egypt in 1929, an important primary Manichaean source on the religion’s story of the cosmos. Over the previous century, numerous recently translated primary texts have given more variants of this central story.24 Other, more traditional sources have been an anonymous Christian account, also from the fourth century, called the Acta Archelai, which adds a long description of Manichaean reincarnation and how it works. The most famous source on the religion has traditionally been Augustine, who, as a former Manichaean, was a capable, if not unbiased, source of information. These different sources I’ve just mentioned have some important variances, and a fourth-century Manichaean text found in Central Egypt, often called the “Prayer of the Emananations” is so open-ended, pluralistic, and polytheistic that it invites us to ask how much the religion was ever actually codified. And speaking of codified, we should take a moment to consider the Manichaean primary texts as they survive today, that broad, multilingual mass of mostly fragmented materials excavated mainly from western China and two different sites in Egypt – a body of scriptures that show literary traditions as diverse as the syncretic ideas they contain. [music]

The Now Lost Manichaean Canon

A Sogdian-language Manichaean text showing a pair of female musicians (9th-13th century) from Turpan.

The first of these scriptures was called something like “The Gospel and the Treasury of Life” or “The Living Gospel.” In it, Mani announced himself as an apostle of Jesus, emphasized that his was a religion of peace, and that his ideology was from divinely inspired visions that came directly from God. Surviving passages of this first Manichaean scripture emphasize the religion’s ecumenical nature, describe Mani’s union with his astral or heavenly twin as a guide who awakened Mani’s true visions, and they declare the religion of Manichaeism to be immortal and tantamount to the greatest Christian Gospels. Saint Augustine quotes extensively from what might be this same scripture, in a strange passage relating to how Mani’s god lures wayward and lustful sinners aboard a shining ship of salvation by having handsome youths and beautiful maidens to entice them on their way.

A second Manichaean scripture, often called the Pragmateia, offers some of the cosmic history we heard summarized before. This text lays out the eternality of both the goodness of light, and the evil of darkness. Like certain Gnostic scriptures, the Pragmateia describes two trees – the tree of life and the tree of death, and how, also as in Gnosticism, shards of holy light were left in the material world to serve as polestars up toward the heavens for humans to find.

A third Manichaean scripture, possibly a book of Psalms, is known mostly from Augustine, who talks about a poem called the “Song of the Lovers” Mani may have written. The poem evidently envisioned Mani’s god, “forever scepter-bearing, crowned with flowers and possessing a fiery countenance,” and reveling with his twelve aeons or chief angels.26 Augustine, angrily recalling the joyous scenes of heavenly celebration in Mani’s psalm, wrote that the prophet who had written this piece of scripture had no proof that the heavenly scenes and floral celebrations of his religion existed, and that Mani had more likely been deceived by demons.

In addition to these three Manichaean scriptures, Mani also collected his epistles, the titles of which are catalogued in a 10th-century Arabic source. One of these epistles, a letter to the Syrian city of Edessa, emphasizes Mani’s divine inspiration. Another describes Mani’s recent illness and his having recently authored ten proverbs. In another of Mani’s epistles, with a melodramatic self-importance that seems to characterize Mani’s writings, the prophet compares his own suffering and achievements to Christ’s, and bemoans his followers’ various infidelities as akin to Judas’ betrayal of Jesus. Another lengthier epistle, fragments of which survive in the works of Saint Augustine, records that basic architecture of the Manichaean cosmos – a light realm, which is good, and a dark realm, which is bad. This Manichaean Epistle, which Augustine calls the “Fundamental Epistle” and records as having been a common text in North African Manichaean circles, is about the overall genesis of Adam and Eve. The epistle, which Augustine evidently knew well, is as kooky as anything we’ve heard in ancient theology – a congregation of light beings mated with one another and created a second generation. Thereafter, the ruler of the dark realm ate this second generation. Then he mated with a female being from the dark realm, and their offspring – comingled beings of light and darkness, were the first humans – this was an alternate Manichaean take on how humanity was created – a different one than we heard a moment ago.

Several other texts were attributed to Mani in antiquity and the Middle Ages – a picture book, apocalyptic treatises, a collection of parables and mysteries, and the aforementioned Šābuhragān – that index of Manichaean teachings that Mani himself wrote in Middle Persian so that his Sasanian patron could learn about the new religion. With hundreds of Manichaean texts now available in a dozen ancient languages, some of which are truly specialist territory, the study of Manichaeism is still fairly young, and will doubtless develop in new directions over the next few decades. But just as a sufficient amount of information about Manichaeism has survived to give us a sense of the religion’s overall cosmic history, enough information has also survived to teach us a bit about the Manichaeans themselves – their worship practices – what they did, and why they did it. [music]

Manichaean Ethics

The Prophet Mani lived out his formative years in a Jewish-Christian religious commune, and this third century commune, like the Essenes of Christ’s time, emphasized self-renunciation and asceticism to an extent that early Christian bishops did not.27 While ascetic separatist communes show up variously in the texts and archaeology of the Ancient Mediterranean and Near East, the Manichaeans received special attention from Christian heresiologists, who found some of the worship practices of the Manichaeans to be peculiar, if not sinful.Manichaeans, believing that the world itself held shards of the divine heavens, had a reverential attitude towards fruit and vegetables as vessels holding holy light from the world above. They were apprehensive about farming and craftsmanship, the thought of tools gouging the earth, or even tools used to make goods and weapons, making them anxious about harming the divine substance. And underlying their ethical ideology was the notion that heavenly light scattered over the dark materials of the world was like a luminous cross – a holy substance sacrificed, but recoverable to judicious mortals who upheld the right practices. These practices involved a spiritually motivated vegetarianism. Vegetarianism had been around in the Ancient Mediterranean and beyond since at least the sixth century BCE – purity cults like the Orphics and Pythagoreans purportedly practiced it so as to not consume the flesh of people reincarnated into animals, and the Manichean ethics on food were not too dissimilar. The Manichaean ethic toward food was that in the debased material world, meat was the heaviest, darkest, and most carnal food – the most intensely material of foods, whereas fruits and vegetables contained more heavenly light. Melons and cucumbers, for instance, light in color and porous and watery in substance, seemed in the Manichaean imagination to be a little closer to heaven than meat and alcohol. And by eating foods filled with shards of light, Manichaeans believed that they could liberate these light particles. Some Manichaean texts show an almost Jainist sense of the sacredness and animism of all life, including plant life, and considering Manichaeism’s well-known ties to India and China, this is hardly surprising. Part of an ancient codex attributed to Mani himself tells the story of the prophet climbing a palm tree to cut its wood and then having the tree speak to him, instilling him with a sudden sense of awe and penitence about what he was about to do.28

Saint Augustine, involved with a North African Manichaean sect in the 370s, confirms primary Manichaean sources on the subject of the sacredness of certain foods. Augustine writes in the Confessions that as a Manichaean “Gradually and unconsciously I was led to the absurd trivialities of believing that a fig weeps when it is picked, and that the fig tree its mother sheds milky tears. . .[that] bits of the most high and true God. . .remained chained in that fruit.”29 It is certainly an odd sounding doctrine to our ears, but, like so many ideas and practices related to the sect, belief in the sacredness of vegetable life doesn’t sound like an especially malevolent or harmful idea.

Now, in this discussion of Manichaean ethics so far, it sounds like we are talking about the Palestinian Essenes, or Buddhist Monks, or some sort of isolationist sect – a separatist group living along the sandbars of the Tigris, eating cantaloupe and praying all the time. This isn’t really the case, though. The Manichaeans had a clergy and a laity – groups Augustine calls the “elect and auditors.”30 The clergy was also carefully structured, and its permanent seat was between the cities of Ctesiphon and Seleucia on the east bank of the Tigris, just fifteen miles downriver from modern day Baghdad. After Mani himself died, a chief authority assumed his position, called the archegos or imam, under whom twelve magisters led the religion’s bishops, who in turn led the elders. Augustine adds that this central council of thirteen had a workforce of 72 bishops, under whom priests and deacons were ordained as functionaries.31 The structure I’ve just described was one of the most important differences between Manichaeism and Gnosticism in the third, fourth and fifth centuries. While Gnosticism is a general term for a number of different and amorphous associated movements, with varying doctrines of salvation, and different emphases placed on figures like Seth and the archangel Barbelo, Manichaeism was more organized and codified early on.

Manichaeanism, Ritualism, and Early Persecution

Manichaeism’s publically visible rituals and organizational structure, we can gather from some fragmentary Manichaean primary sources, made the religion a clear target. A Manichaean homily describes how adversaries of the Manichaeans “seized the [Manichaean] bishops. . .[the] treasuries. . .They put armour on some (and made them go into competition) with she-bears [and lionesses]. . .in their iniquity, they. . .crucified the youths, the children (and. . .) eunuchs. They sawed up some [of]. . .them boasting.”32 Christian martyr stories, as we’ll soon see, are filled with lions and torture and fountains of gore, and so there’s some possibility that this is standard rhetoric ultimately rooted in texts like the Book of Daniel. However, minority religious groups in large empires are prone to disenfranchisement and prosecution, and the earliest Manichaeans were indeed corralled and punished alongside their Christian brethren, and later, by their Christian brethren. In Rome, at least, the persecution called the Diocletianic Persecution, or Great Persecution, lasted from 303-311, being especially ferocious in the eastern provinces. Half a century before, the Decian Persecution of 250 has gone down as perhaps the second most infamous Roman massacre of Christians, and the time period bookended by these infamous persecutions – 250-311 CE, I mean – roughly aligns with that of Mani’s successor Sisinnios, reported as a martyr in a different Manichaean text. Sisinnios, however, was purportedly killed by the Sasanian king Vahram.33 Let’s not get lost in the weeds here with Sasanian Kings and Manichaean church leaders – the main point to remember is that Manichaeans, like their Christian contemporaries, were being persecuted in the Roman and Sasanian empires during the third and early fourth centuries, because their creeds appeared potentially seditious to emperors and provincial governors. These persecutions were recorded in a textual tradition that likely took some poetic license, as works of ancient history tend to, but the persecutions took place nonetheless.After Mani and the first Manichaean imams passed away, Manichaeism washed westward into Egypt and Syria during the late 200s, and when Constantine passed the Edict of Milan in 313, Manicheans could claim themselves as members of a reform sect of Christianity. Within the Roman Empire, as the 300s opened, Manichean centers included Antioch, and Lycopolis in central Egypt, and from there, the religion spread westward into the Christian epicenter of North Africa including parts of modern day Algeria and Tunisia, where Saint Augustine grew up. Augustine, born about 75 years after Mani died, left the religion fairly early in his career, never having assumed an office in the Manichaean clergy. Augustine’s defection from Manichaeism, chronicled throughout his works, took place in the 380s, or when the theologian was in his 30s. These years – again the 380s – were the same decade that the emperor Theodosius and his colleagues made Nicene Christianity the official religion of the Roman Empire. Manichaeism’s days were thereafter numbered in the Roman Empire. A century later, the early Catholic Church’s partnership with the Roman Empire had positioned itself to destroy other branches of Christianity in the Mediterranean, through a mixture of preferential laws, the destruction of religious texts, and sometimes, executions.

Now that we’ve talked a little about Manichaean practices – what the Manichaeans did – and a bit about the first century and a half of the religion’s history, I want to talk a little about the fate of Manichaeism and its slightly older brother Gnosticism – what eventually happened to these religions in the Greco-Roman world. The Roman Emperor Constantine issued the Edict of Milan in 313, and the Emperor Theodosius, the Edict of Thessalonica in 380. The first made Christianity legal in the Roman Empire, and the second made a specific strand of Christianity – again Nicene Christianity – official state religion. In 303, Christians of all stamps in Rome were running scared under the Diocletianic Persecution, or Great Persecution – the most existential threat the religion ever faced. By the 380s, suddenly, Christians were persecuting other Christians, with the first Christian state-sanctioned execution of another Christian person having taken place in 385, with the killing of the heretic Priscillian. Laws survive from the reign of Theodosius that show the newly Romanized church turning its crosshairs onto Manichaeans and their practices. In the span of two generations, then, the church joined the state, and over the next century, often in response to the centrifugal nature of early Christian sectarian groups like Mani’s, Roman Catholicism sought to standardize and centralize worship of Christ within the bounds of where Christianity was practiced. [music]

Manichaeanism and Christianity After 380

The Roman Catholic pushback against Manichaeism, at its helm none other than the formidable Saint Augustine himself, had components that were as old as the Apostolic generation. The Gospels and Epistles of the New Testament are most often skeptical of Mosaic Law, with Jesus himself, and thereafter Saint Paul taking a fairly concerted stance against all the rules and regulations printed in the Pentateuch. In other words, according to Christ and Paul, it wasn’t about splashing turtledove blood out on a Tabernacle altar, lighting the incense at the right moment, eating this but not that, or even being circumcised. Jesus and his most influential Apostle made it clear that anyone who wanted to join them could do so without agonizing over the 613 Commandments of Mosaic Law.This simplification made attracting Gentile converts easier, and in our study of Early Christianity we have seen how second- and third-century Christian theologians went in all sorts of directions afterward. Some, like Marcion and various Gnostics, were ready to toss out Judaism and its scriptures altogether; others, like Mani’s own youthful Elcesaite sect, practiced a hybrid form of Jewish Christianity, and a great many in between took various stances on just how Jewish Christianity ought to be. By Augustine’s age, with Nicene Christianity having been accepted by the Roman state system, the young church had already developed something approximating its current stance on the Hebrew Bible and the rules lists therein – a respect at their vintage and ancient majesty together with a pragmatic sense that actually following the Mosiac behavioral codes would be difficult for any individual, let alone institution, to put into practice and sustain. When Nicene or Trinitarian Christianity was finally given an imperial rubber stamp in Rome in 380, then, roughly the time Augustine left Manichaeism, I suspect that any educated Christian cleric who’d been through a codex of the Bible, and had stood in front of a congregation would have regarded Manichaeism’s novel rules lists with particular skepticism. Christianity had already been down that road – Peter and Paul had quarreled about it, and so there was no need to hurl into the fray a bunch of new regulations mandating vegetarianism and promulgating that cantaloupe held heavenly light. Augustine engages with Manichaeism’s dietary rules lists at a couple of points in his writings, and his exasperation with these novel statutes is palpable.

More seriously than rules governing food consumption, though, was something much more obvious. Mani had declared himself a prophet or apostle of Jesus Christ, claiming direct visions from God. He was not the first to do so in Christian history – the Phrygian prophet Montanus, of Mani’s grandparents’ generation, had caused a stir when he made the same claim in the late 100s, and the church father Tertullian, controversially, had followed the same path in the 200s. Augustine and his generation of bishops had all sorts of reasons to decry self-proclaimed Christian prophets, not the least of which was the sheer arrogance of claiming a direct connection with the Christian god. A section of Mani’s autobiography that’s thought to be genuine tells us that “according to the will of our lord, I left. . .in order to sow his most beautiful seed, to light his brightest candles, to redeem living souls from subjection to rebels, to walk in the world after the image of our lord Jesus, to throw on to the (earth) a sword, division and the blade of the spirit.”34 This passage, embroidered with Christ’s words from the New Testament, is one of the more arrogant things ever penned by a theologian, and to Mani’s Christian skeptics, Jesus Christ had been quite good enough as a savior figure, thank you – there really was no need for some guy from the banks of the Tigris to hustle in and perform an encore.

Additionally, as the church matured as an institution, increasingly its officials could not tolerate the idea of further divine revelation beyond the elected clergy. It was bad enough to have maverick self-proclaimed prophets out there wasting good papyrus yakking about there being gazillions of angels and aeons. Perhaps even worse, though, was the general idea of latent heavenly remnants in all humans giving everyone a direct cable to the divine. In a Manichaean text chronicling a vision of Shem, son of Noah, Shem tells us, “I was thinking about in what manner all works came to be. And while I was considering, suddenly, the living (spirit) seized me and (took me) with great (force and) set me (on the top) of a (very) high mountain (and) spoke to (me) saying. . .give glory to the greatest king of honour.”35 Shem is admittedly a Biblical patriarch, but more generally the widespread Manichaean and Gnostic notions that each of us – even everyday people – is filled with a small pocket of heaven, and that we could come to cultivate and understand this pocket of heaven, to bishops of Augustine’s generation, threatened to dissolve the barrier between the clergy and laity. You couldn’t have men and women out there eating melons and cucumbers and reflecting on the copious beauties of a flawed, but still miraculous world, after all. Such freewheeling dreamers, as history had shown, would be liable to stop coming to church and to generate their own grab bags of religious texts.

This central Gnostic and Manichaean notion of shards heaven scattered on earth, enshrined in humans and glittering in the plants and natural world around us, began to hit a brick wall in the 370 and 380s. First, and we’ll talk a bit more about early Roman Catholic religious laws later, the Christian emperors Valentinian, Valens, and Theodosius issued various statutes encouraging the persecution and murder of Manichaeans. And in fact, especially Augustine himself, the main architect of the doctrine of Original Sin, could not abide by the Gnostic and Manichaean idea that people shimmer with light as much as they palpitate with darkness. Augustine countermanded this notion furiously toward the end of his life in 428 or 9 in his book On Heresies. Augustine wrote that “As a consequence of [their] ridiculous and unholy fables, [Manichaeans] are forced to say that both God and the good souls, which they believe have to be freed from their admixture with the contrary nature of evil souls, are of one and the same nature. Then they declare that the world has been made by the nature of the good, that is, by the nature of God.”36 A theologian more intensively focused on the debased nature of humanity, Augustine had a special intolerance toward the Manichaean idea that we might be something other than wayward and meritless sludge.37

While some aspects of the traditional Catholic criticism of Manichaeism seem a little harsh by modern standards, others are easier to relate to. Ever since the sixth century BCE Greek philosopher Xenophanes made fun of Pythagoras’ writings on reincarnation, we have on record a pretty diverse bunch of skeptical and conservative voices dissenting against various New Age cult groups. In Xenophanes’ day, it was the Pythagoreans and Orphics; six centuries later, in Philo of Alexandria’s, the Therapeutae and the Essenes and perhaps the earliest Christians; and a thousand years later, in Augustine’s, it was the Gnostics and Manichaeans – Christian sects with colorful ideologies that were growing like weeds in spite of the best efforts of more cautious and conservative individuals and institutions. Augustine and his early Roman Catholic peers didn’t like Manichaeans for reasons mentioned above, but it was also because these newcomers to the religious scene seem to have had the same self-important sanctimoniousness that earlier purist cult groups had had long before them – complex and extensive dietary restrictions, an indisposition toward traditional forms of employment like agriculture (in the Manichaeans’ case, because they didn’t want to harm plants), and unusually restrictive norms governing sexual behavior, even in marriage. Catholic assessments of Manichaeism from Late Antiquity call out Manichaeism’s heresies, but they also paint Manichaeans as hypocrites, full of cant, bluster, and hubris. I think if anyone starts an environmentally conscientious, vegetarian purist sect oriented around spiritual self-improvement and novel deities in any age, they’re going to meet with exasperated skepticism, as Earth seems to have always already had quite enough gods and creeds.

There were also, more simply, aspects of Manichaeism that were just too strange and longwinded to be intelligible to a typical congregation. In the previous episode we heard some Christian church fathers gawking at the cavernous heavenly realm of Gnosticism, with its hundreds of heavenly beings, and their malevolent counterparts down on earth. And as we saw last time, Christian critics like Irenaeus and Tertullian are often refreshingly clear and balanced in their assessment of Gnosticism – it wasn’t so much that Gnosticism was diabolical and its adherents were going to burn in a lake of fire as it was that Gnosticism was nutty and overgrown and out of control. For the relationship between Christianity and Manichaeism, we have plenty of primary Catholic sources, including, of course Augustine. But one especially interesting source – written by the Neoplatonist philosopher Alexander of Lycopolis, likely during the 300s, stands out – a sort of compare and contrast analysis of Manichaeism and proto-Orthodox Christianity, written by a third party not involved with either group. Alexander of Lycopolis first tells us his thoughts on Christianity. Christianity, the Neoplatonist philosopher Alexander of Lycopolis proclaims, is a simple philosophy. It has definite advantages – he writes that “The masses who listen to [Christian church leaders] make, as can be seen from experience, great progress in moderation, and their actions are stamped with a distinctive mark of piety; [Christianity] rekindles the moral sense which such customs strengthen, and leads it progressively towards a desire for the good.”38 This is all pretty positive, obviously, but Alexander of Lycopolis also had some criticisms of Proto-Orthodox Christianity. He tells us that it’s a bit too vague about what God is, and a little too iffy on what actually constitutes virtue, and how to pursue it. Platonists, obviously, could spin their wheels for centuries about the pursuit of virtue, so it’s not too surprising one of them would choose this bone to pick with early Christianity.

But Alexander of Lycopolis had considerably more to say about Manichaeism – Lycopolis once again was in central Egypt and one of the seedbeds of Manichaeism during the 300s, so Alexander of Lycopolis he knew a lot about it. The philosopher deemed that Christian ideology as he had seen it had been characterized by “the efforts of each person to out-do his predecessor through the novelty of his ideas. . .An example is given by the man known as Mani: He was of the Persian race, and, to my mind at least he surpasses all his rivals in the extravagance of his proposals.”39 What follows is a 26-chapter assessment of those proposals – incidentally an important source on Manichaeism in itself – that attempts to understand the Manichaean worldview, often getting hung up on various parts of the labyrinthine three-part history of the Manichaean cosmos that we discussed earlier. [music]

Manichaeism’s Later History

A Yüen Dynasty (13th-14th century) painting of the Manichaean universe. When early church fathers wrote about Manichaeanism’s relative Gnosticism, the assessment was often that the religion’s elaborate architecture and plurality of deities marked it as ridiculous and unsoundly constructed. However, as the church stabilized its doctrines, Gnosticism and Manichaeaism were vilified more on the basis of their foreignness and otherness than their actual ideological architecture.

Two hundred years later, a Catholic historian named John Malalas was working out of Antioch. John Malalas, toward the end of the 500s, took a severer and more discernibly Roman attitude toward heresy than his more mild predecessors Irenaeus and Tertullian. Malalas wrote that Manichaeans were from “the Persians – a nation hostile to us [and that] they are perpetuating many evil deeds, disturbing the tranquility of the peoples and causing the gravest injuries to the civic communities. . .they will endeavour, as is their usual practice, to infect the innocent, orderly and tranquil Roman people. . .with the damnable customs and perverse laws of the Persians. . .We order that the authors and leaders of these sects be subjected to severe punishment, and, together with their abominable writings, burnt in the flames.”42 The basis for torturing Manichaeans to death, according to this sixth-century church historian, was that “It is indeed highly criminal to discuss doctrines once and for all settled and defined by our forefathers.”43 Malalas’ line of reasoning here is as familiar as it is disquieting. Neither Mani nor Jesus Christ, whose most emphatic commandment is to love thy neighbor, would have approved of Malalas’ ethnocentrism, nor his bloodlust.

There are ample textual sources that show an increasingly violent and intolerant attitude toward Manichaeanism and other forms of Christianity crystallizing in the church between the imposition of Nicene Christianity in 380 and the Muslim conquest of Egypt in the 640s, an event that gave the church a much more forceful source of theological competition to contend with. A Greek text from the Levant, dated to about 400, describes a Manichaean practitioner named Julia as a “pestilential woman” whose religion has “mixed the venom from various reptiles to make a deadly poison capable of destroying human souls.”44 It isn’t a very late text, nor an especially condemnatory one – the bishop Saint Porphyry prays for the loquacious Julia’s silence, and she suddenly falls into an ecstatic quietude, and dies. Rather than defiling the corpse of the woman he perceives to be a heretic, Saint Porphyry buries her, having let God’s will do its work. It’s one of the milder Catholic tractates to have survived about Manichaeism, and yet it perfectly exhibits the Roman-ness of the Roman Catholic Church’s early centuries. The church and state had fused, and the state with which the church had fused had a centuries long record of vilifying cultural others, especially from the east – the Cleopatras, the Zenobias; more generally the Parthians and Sasanians, and even before them, the Greeks.

Roman laws that survive from the early life of Augustine and afterward begin to show a chilling effort to destroy Manichaeanism within the Empire. A law of Theodosius passed in 381 proclaimed that Manichaean children could not inherit their parents’ property unless they disavowed their family religion. The Abbasid Caliphate, a few centuries later, would do something similar, modifying property inheritance laws to try and eradicate Zoroastrianism from the Middle East and Central Asia. While such regulations are baldly discriminatory efforts to hurt theological groups out of step with state leadership, the Byzantine Empire had issued much severer ones earlier on. Around 500, the Byzantine Emperor Anastasius I proclaimed that all Manichaeans were prohibited from life in the empire, and that if they were discovered, they were to be executed.45 The Emperor Justinian, a quarter century later, also issued a blanket declaration demanding the deaths of all Manichaeans, not only in the Byzantine Empire, but everywhere. The proclamation says that Manichaeans “wherever on earth appearing, ought to be subjected to punishments to the extreme degree.”46 With a death warrant out for all Manichaeans, and also, property inheritance laws in place that demanded that their property could not be passed down to heirs, but would go to the public treasury, Byzantine enforcers had an added financial incentive to what had become a general free-for-all against the once widespread and unfettered ranks of the Manichaeans. [music]

The Long Term Significance of Manichaeism