Episode 86: An Introduction to Late Antiquity

Once pervasively described as a period of fall and decline, today Late Antiquity is often understood as a period of cultural flowering and economic revolution.

| Read Transcription | References and Notes |

| Episode Quiz | |

| Episode on Spotify | Episode on Apple Podcasts |

| Previous Show | Next Show |

Late Roman Imperial History and its Aftermath, c. 200-700 CE

Gold Sponsors

Jeremy Hanks

John David Giese

ML Cohen

Silver Sponsors

Chad Nicholson

Francisco Vazquez

John Weretka

Patrick Radowick

Anonymous

Steve Baldwin

Mike Swanson

Sponsors

Alejandro Cathey-Cevallos

Alysoun Hodges

Angela Rebrec

Benjamin Bartemes

Brian Conn

Chloé Faulkner

Chris Tanzola

Daniel Serotsky

David Macher

D. Broward

Janet Y.J. Chen

Joshua Edson

Kyle Pustola

Laura Ormsby

Laurent Callot

Leonie Hume

Mark Griggs

Natasha Worle

Oli Pate

Anonymous

Anonymous

Riley Bahre

Rob Sims

Robert Baumgardner

Rod Sieg

De Sulis Minerva

Sebastiaan De Jonge

Sonya Andrews

Steven Laden

Sue Nichols

Susan Angles

Tom Wilson

Tray Davis

Verónica Ruiz Badía

As exciting and pivotal as these events sound, Late Antiquity has never been a very popular period of history to study. The emergence of Christianity into the Roman world produced a complex marbling of old and new religion, just as barbarian migrations forged compound, situational identities and alliances within and beyond the bounds of the empire. With the disintegration of the western empire over course of the 400s, and even before that, the Crisis of the Third Century and the rise of Diocletian Tetrarchy at the close of the 200s, Rome, its wars, and its ruling dynasties cease giving us a central cable that we can use to understand the greater web of ancient history. Suddenly, in the 200s CE and after, things start getting quite busy, and we begin to have the Visigoths, the Vandals, the Huns, Ostrogoths, Franks, Lombards, and more, and among them, more pervasive century after century, the Catholic clergy, itself diverse and restless as well. Late Antiquity is a period of history that may lend itself better to specifics than generalizations – to case studies more than broad overviews. Sometimes, looking at a couple of handfuls of sand tells us just as much as trying to memorize miles of ever-shifting dunes. So I think that over the next twenty episodes or so, as we study works of mainly literature and theology from Late Antiquity, and learn about the circumstances that produced them, we should become fairly well oriented within this period, even if we don’t acquire the panoramic expertise of professional historians on the subject.

Still, this initial program is a general overview of Late Antiquity, and in order to introduce the period as a whole, I want to quote from the great historian Peter Brown, whose 1971 study The World of Late Antiquity more or less inaugurated modern scholarship on the period. Here’s an excerpt from the first page of Peter Brown’s influential book.

To study [Late Antiquity] one must be constantly aware of the tension between change and continuity in the exceptionally ancient and well-rooted world round the Mediterranean. One the one hand, this is notoriously the time when certain ancient institutions, whose absence would have seemed quite unimaginable to a man of about AD 250, irrevocably disappeared. By 476, the Roman empire had vanished from western Europe; by 655, the Persian empire had vanished from the Near East. It is only too easy to write about the Late Antique world as if it were merely a melancholy tale of ‘Decline and Fall’: of the end of the Roman empire as viewed from the West; of the Persian, Sassanian empire, as viewed from Iran. On the other hand, we are increasingly aware of the astounding new beginnings associated with this period: we go to it to discover why Europe became Christian and why the Near East became Muslim. . .Looking at the Late Antique world, we are caught between the regretful contemplation of ancient ruins and the excited acclamation of new growth.1

So Peter Brown’s work there was part of a general revisionist approach to history during the twentieth century – a movement to reconsider the years between 200 and 700 not as some regrettable descent from Roman unity into fractious superstition, but instead as a period cultural synthesis and economic revolution. Almost anyone who has taken a course on European history over the past generation has benefited from changes in historiography championed by scholars like Peter Brown – changes which have led to the term “Dark Ages” being cast aside in favor of “Middle Ages” and “Medieval Period.” When we talk about the study Late Antiquity today, a point of contrast is often Edward Gibbon’s multivolume set The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, completed in 1788, a work that has a generally negative perspective on the rise of the Catholic Church, and at one juncture describes a thousand years of intellectual history as “the rubbish of the dark ages.”2

Changing Approaches to Early Medieval History

The Italian Humanist Petrarch (1304-74) is the earliest known source of describing the Middle Ages with the term tenebrae, or darkness, thus inaugurating the way that Late Antiquity has customarily been understood.

Today, roughly speaking, we use the terms Early Middle Ages for the period from 500-1000, High Middle Ages from 1000 to 1250, and Late Middle Ages, from 1250 to 1500. Out of these three general periods, the Early Middle Ages are by far the longest period – five centuries rather than two and a half. To return to our central term for today, “Late Antiquity,” this term, and its intended focus on the years between 200 and 700, were somewhat gimmicky at their inception, being more of a shift of emphasis, chronology, and attitude than an attempt to study things never before studied. But as a historical period, Late Antiquity has stood the test of time. The discipline emphasizes the continuity of classical traditions, deep into the Christian period. Focusing on Late Antiquity on the historical timeline, and bracketing Classics to the left and Medieval Studies to the right allows us to concentrate directly on how the seeds of modern European state systems were sown, and how Catholicism arose as an institution. Studying the trees, rather than the forest of Late Antiquity, I think that by the end of this season we’ll understand it as an epoch more characterized by geographical movement, economic reorganization, and cultural amalgamation than continuous collective catastrophe. Because while pandemics, and turbulence wrought by population migrations did cause the moneyed and literate classes of the late Roman empire to surrender some of their resources to new groups of immigrants, the average Roman citizen and slave of the 200s, 300s, and 400s, unless their city was being sacked, likely experienced far less trauma and bewilderment than older works of history once led us to believe. The Roman Empire, while it was never the morally rancid quagmire that some Christian historians claimed it was, was still a plutocracy, and oftentimes a ruthless one. Wealthy scholars of the Renaissance and Enlightenment, like Petrarch and Edward Gibbon, indeed saw lucent reflections of themselves in the golden texts of the Greco-Roman past. But as we’ve learned in previous episodes of this podcast, even during the shining summit of the Pax Romana, during the Nerva-Antonine dynasty of 96-192, life for the vast majority of human beings in the Roman Empire was still nasty, brutish, and short. Thus, as the aforementioned historian Peter Brown puts it in a later book, during Late Antiquity, “if, for certain classes at certain moments. . .‘the epoch turned black,’ this may mean no more than that it turned a slightly deeper shade of the ever expected grey.”5 Put simply, for the vast majority of humanity during Late Antiquity – the agrarian masses who worked the fields of Europe in 200 CE, and worked the same fields in 500 CE, the fabled decline and fall of the Roman Empire would have scarcely been noticeable, as they had never enjoyed any pedestal to decline and fall from in the first place.

Still, with all of that said, of course the cities and cultures ringed around the Mediterranean in the year 700 were of a very different makeup than those same cities and cultures had been back in the year 200. The story of how this happened is something we’ll explore over the next twenty programs. But to begin – to get our bearings in this often neglected era of history, let’s talk for just a bit longer about historical methodology and Late Antiquity, as boring as these words might sound when applied to such an exciting period of history. Put simply, a number of the main scholarly approaches to this era, like Gibbon’s, while they have motivated strong scholarship, have also had some sizable blind spots, and worse, some very pernicious prejudices. [music]

Late Antiquity and Historiography

Revaluing the Barbarians: the Monumenta Germaniae Historica

Late Antiquity – those complex centuries between 200 and 700 – has traditionally been understood as a period of clashes between diametrically opposed groups. We hear, conventionally, of Romans and barbarians. We hear of Christians and pagans. We hear of breakaway imperial usurpers, and rightful Roman dynasties. These traditional dichotomies invite us to understand Late Antiquity as a period of solidified groups with irreconcilable differences, in competition for religious dominance or natural and monetary resources, playing a zero sum game for victory. In the history of historical studies, these conventional oppositional pairs –Romans and barbarians, Christians and pagans – these pairings have often led historians to project their own identities and cultural agendas into the past. As we heard a moment ago, Petrarch and Gibbon looked back into Late Antiquity and, identifying themselves with what they perceived as the splendor of Classical Greco-Roman culture, understood both Christianity as well as barbarian migrations as things that had terminated a now lost golden age.

A Monumenta Germaniae Historica volume from 1872, part of a nineteenth century effort to create an omnibus on one barbarian group’s experiences during Late Antiquity.

Thus, broadly speaking, from the early romantic period, or late 1700s onward, earlier generations of especially German and French revisionist historians attempted to pinpoint the roots of their nations in the strapping populations of the bygone Goths and Franks, romantic nationalism’s fascination with the Middle Ages being part of romanticism’s general turn from Enlightenment emphases on progress, rationality, and classical learning.6 Gibbon, in the 1780s, had drawn a portrait of the Roman Empire’s last centuries as a tragic descent from the Classical past. But, as you just heard, later generations of continental scholars saw the western empire’s twilight as the glorious curtain rise of their own ethnic populations on the world stage. The Goths, Vandals, Huns, Franks, and others, then – they’ve been yanked back and forth in a historiographical tug-of-war, alternately valued and devalued depending on who’s been pulling the rope.

While all of that is fairly interesting for its own sake, I think the most important thing to remember is that for centuries, scholars studying Late Antiquity have felt like they have stock in one side or another of a perceived dichotomy – a lost golden age of the Classical Mediterranean, or the arrival of vigorous new migratory groups from the north that supplanted an aging Roman empire. Both of these approaches have problems – in Gibbon’s case an often harsh prejudice against Christianity combined with an occasionally absurd idolization of certain eras of Roman culture, and in the case of the Monumenta Germaniae Historica, needless to say, worldviews rooted in any kind of racial supremacy have tended to have horrible and catastrophic results for our species.

Christians and Pagans: Changing Historical Approaches

So that is the first oppositional pair that is usually brought to bear to understand Late Antiquity – Romans, and barbarians. We will spend much of the rest of this episode talking about barbarian migrations, so for now, let’s move onto the second oppositional pair – Christians and pagans. For centuries and centuries prior to Edward Gibbon’s Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, the main framework leveraged to understand Late Antiquity – in historical texts that have survived, anyway, was a contest between Christianity, and everything else. We can see this framework appear on the historical record from second century patristic apologies onward – this notion that Christianity was a single thing with expansionism at its core, a burgeoning force that caused ideological standardization against the maelstroms of both pagan opposition and various forms of Christian heresy. And as historian Averil Cameron writes, “Unfortunately, modern criticism still largely polarizes the [period] by starting from the assumption of a great divide between Christian and pagan; this has the effect of obscuring the real issues by implying that everything. . .is to be explained in terms of ‘conflict.’ By contrast, as anthropologists and indeed theologians have realized in recent years, translating from one cultural system into another is not a straightforward process; it embraces many shades of relation, from outright conflict to near-total accommodation.”7

The Empress Aelia Eudocia (c. 401-60) flourished in a late antique world during which Christianity and paganism coexisted comfortably, her surviving texts evidence of syncretistic approaches toward religion and literature during the fifth century.

Thus, while we will study, in a lot of detail, the growth of Christianity during Late Antiquity, it’s important to remember right here at the beginning that Christians and pagans weren’t necessarily concretized or oppositional groups. They were neighbors, friends, co-workers, intellectual colleagues, and more. And while certain Christian tracts by Tertullian, and Augustine, and John Chrysostom have their moments of staunch intolerance, and while law codes like those of Theodosius and Justinian show chilling prejudice against the unconverted, Christianity still grew organically as a novel ideological force in a diverse world, often as a supplement to paganism, rather than a replacement for it.

So, to wrap up these introductory remarks on methodology and Late Antiquity, this period of history has often been understood as an era of sparring between opposing and categorically different groups – Romans, and barbarians; Christians, and pagans. Those who have written about the period have seen themselves in the past in some way or another, celebrating the triumph of Christianity, or the triumph of imagined ancient German ancestors, or bewailing the fall of classical Mediterranean splendor, or pagan diversity. Over the next twenty episodes, we will not do this. We will look at some of the most important documents of Late Antiquity – mainly literary ones – and see what we find there. These primary sources, I think, will to some extent let the period tell its own story, a story full of fusions, and compromises, and many deeply admirable people of all sorts, with a surprising number of laughs and oddities, and more broadly quite a few delightful back corners and lessons for the ages.

Before we get into this documentary history of Late Antiquity, though, we need to do something else. We need to meet the barbarians – to learn about who the main groups were, and how, where, and when they emerged on the historical scene. Today, scholars are still a little queasy about using the word “barbarian.” It goes without saying that barbarian is a derogatory term, and to a lesser extent that an interpretatio romana, or “Roman interpretation,” still heavily colors our knowledge of the peoples who percolated the borders of Roman civilization in various places, times, and ways. Still, we do need a catch-all term for the itinerant, non-Roman groups who were some of the main movers and shakers of Late Antiquity, and “barbarian” remains the word that most scholars use. Now, I realize that many of you listening are familiar with the general events of the late Roman empire – the combination of civil wars and population migrations that had broken Rome’s western half into fragments by the end of the fifth century. But, so that we’re all on the same page, the remainder of this episode will introduce you to the main migratory and military events that happened during the first centuries of Late Antiquity. In later episodes in this same sequence, we will talk much more about the inception of the Catholic Church and Christian developments over the period, and we will eventually steer heavily into the sixth and seventh centuries. But for the present, we need to lean over a timeline of the 200s, 300s, and 400s – to learn about who showed up in the Mediterranean world during these centuries, and what happened when they did. So let’s start today’s story in the year 208, in a place far distant from Rome, north of that famous bulwark called Hadrian’s Wall, in a territory then called Caledonia, within the borders of modern day Scotland. [music]

208-211: The Severans in Caledonia

Between 208 and 211, the Roman Emperor Septimius Severus spearheaded a military campaign north of Hadrian’s Wall. After the Civil War that had followed awful reign of the Emperor Commodus, Severus had emerged as victor back in 193, a military man to the core, who perhaps just wanted to spend his last years in the field. The Caledonian campaign, as far as we can tell, was not prompted by any major recent offensives or raids. It was a conquest of the old Roman ilk, as when in the bygone days of the Republic, blue blooded Roman men made names for themselves by marching legions into barbarian territories and returning with spoils and triumphs. Septimius Severus, being an old and decorated military man, had little to prove on the battlefield, and the Roman historian Cassius Dio describes the aging emperor being borne across the territory of modern day Scotland in a litter.9 The Caledonian tribes proved to be judicious tacticians, the guerilla resistance that they waged being successful to such an extent that Severus was there much longer than he had expected to be. He had brought with him his sons, the future Emperors Caracalla and Geta, so that the volatile and decadent young playboys could get a better sense of the Roman martial spirit that had led their father to the throne. But due to Caledonian defensive maneuverings and delay tactics, Severus was unable to bring the Caledonians to heel. Enraged, the old general-turned-emperor planned a campaign of ethnic cleansing after the Caledonians broke a peace treaty, but before he could finish his mission, he fell ill and died in the city of Eboracum, or York, in the year 211. Severus’ older son Caracalla went through the motions of continuing the Caledonian campaign, but soon lost interest, and he returned to the pleasures of the Roman capital. Roman garrisons retracted south of Hadrian’s Wall, and Caledonia was never invaded by Romans again.

Septimius Severus’ Caledonian campaign, a generation before the Crisis of the Third Century, did not bode well for the empire’s future efforts to wage war on barbarian outsiders for the duration of Late Antiquity. Photograph by Katolophyromai.

By 235, old Septimius Severus’ dynasty had grinded six more emperors in less than a quarter of a century, ending on a high note with the competent rule of Severus Alexander and his mother Julia Mamaea. But three years later, in 238, Roman civilization was rattled by no less than six claimants to the imperial throne. These included the burly Maximinus Thrax, who’d decapitated the Severan dynasty in 235 and afterward proved a harsh and loathed emperor, the Roman senators Pupienus and Balbinus, with silver-tongued promises of making the rich relevant again, and the African Proconsul Gordian and his son, who rose up in spite of themselves in the wake of Maximinus Thrax’s assassination. The so-called Year of the Six Emperors, again 238, marks the beginning of Rome’s Crisis of the Third Century, a familiar term to students of Roman history. Modern historians now understand the Crisis of the Third Century as somewhat less “Crisis-y” than previously reported. But with 28 emperors backstabbing and warring for the throne from 238-284, the deadly Cyprian Plague oozing through the years between 249-262, and the first major state sanctioned persecution of Christians in 250, the Crisis of the Third Century still merits its traditional title. Let’s return to 238 CE, though, the Year of the Six Emperors that kicked this crisis off.

The spring of 238 saw chaos at the heart of the Empire not seen in a generation. Gordian and his son were killed in Carthage by Maximinus Thrax’s supporters. In the capital, strife between supporters of Maximinus Thrax and those of Pupienus and Balbinus caused destruction and discord in the streets of Rome, and Thrax was soon murdered by his own troops just outside of the northeastern Italian city of Aquileia. Later, in the summer of 238, senatorial emperors Pupienus and Balbinus were dead, too, killed by the Praetorian Guard, and the boy emperor Gordian III, not yet 13, ascended to the throne, an unlikely candidate who, squished between Senatorial backers and the Praetorian Guard, didn’t last long. It’s worth noting, by the way, that for a few months during the spring and summer of 238, one of the most powerful people in the world was indeed actually named Pupienus. Surely many of our names will sound funny to future generations too. Anyway, in addition to the mighty Pupienus ascending to the throne, something else happened in 238 CE – something up in modern day Romania, that was as important as any of this. At the mouth of the Danube, in Rome’s northeastern province of Moesia, there was a Roman fort at a site called Histria. The fort at Histria, in 238, was sacked and taken by a band of people called the Capri, who thereafter used it as a foothold for further conquests in the western part of the Black Sea. The Capri were not the first barbarians to appear in Moesia. Moesia, and Dacia – these provinces to the extreme northeast of the Roman Empire, had long had dealings with barbarian tribes. The Capri deserve special mention here because they were a part of that historically consequential barbarian group called the Goths, a group whose name emerges onto the historical record in precisely 238, at the opening moments of Rome’s Crisis of the Third Century. [music]

The Northern Barbarians in Late Antiquity: An Introduction

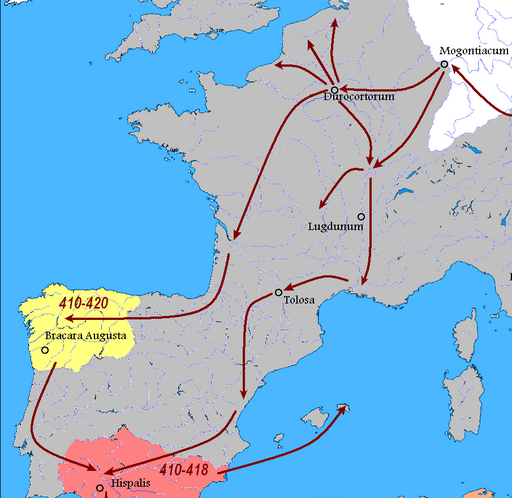

If you’re looking for big picture history of the barbarian migrations during Late Antiquity, you could do worse than staring at this map for a while – the movement of the Visigoths and Vandals is especially broad ranging and pivotal to late imperial history.

The story of Rome’s encounters with northern barbarians is a 600-year-long play with three overlapping acts. In the first act, Romans fought these groups as individual tribes, and Romans tended to prevail. In the second act, these tribes began form coalitions and gradually adopted Roman technology and military practices, and the two groups were more evenly matched. In the third act, northern and central European migrants along the borderlands had broadly adopted Roman technology and culture, Rome’s armies were frequently made up of barbarian troops and commanders, and Christianity had blurred the lines between Roman and barbarian further. The finale of the drama was the Italian peninsula becoming the kingdom of the barbarian Odoacer in 476. This changeover, however, was much less dramatic than it sounds. Odoacer, of barbarian extraction, and like so many others with barbarian roots, was a Roman military man, and not some stranger wearing skins and dashing down from the frosty north with a battleaxe. Odoacer had by the 470s become a fixture in the Italian military. Promising Roman soldiers better fortunes than the flagging Western Empire had been able to provide them, Odoacer fought off his military rival, invaded Ravenna, then the capital of the Western Empire, and deposed Romulus Augustulus, traditionally the final Roman Emperor in the west, in the year 476. The deposition of Romulus Augustulus was actually regarded as positive news by the Byzantine Emperor Zeno, who had not recognized Romulus Augustulus as a legitimate emperor to begin with. And Odoacer thereafter interacted with Constantinople as a Roman client king. The official terminus point of Rome’s imperial dynasty in the west, then, in 476, resulted from a relatively small scale military coup, such as Rome had experienced dozens and dozens of times in the past, rather than strange warriors in skins charging down from the Alps. A number of famous European leaders of the fifth and sixth centuries – Alaric, Odoacer, Theoderic, Gundobad, Clovis – these were people cut from the same hybrid cloth. They were largely culturally Roman, high level operators in the Roman military, comfortable in Latin, and often students of high Roman culture. But at the same time, due to various combinations of prejudice, being used as cannon fodder or otherwise treated unfairly by Roman emperors, and sometimes just trying to survive, the crossbred military leaders of the 400s and 500s also remembered their roots as immigrants, or the children or grandchildren of immigrants, and they looked out for the needs of their families and people, too.

That, then, is the long tale of Rome and the northern barbarian tribes in a paragraph, the story of two paint buckets banged against one another for so long that by the late fifth century, there were no longer two colors, but only variations of a single composite mixture. Still, though, the details of how this happened offer us much of the story of Late Antiquity, so we should review some of the main flashpoints of conflict between Rome and barbarians from beyond the Danube and Rhine, leading up to 476.

Rome and the European Interior: The Longer History

Even by the year 238 CE, a generation after old Septimius Severus failed to subdue the Caledonians in modern day Scotland, when the Roman fort at Histria was sacked by a subgroup Goths, and the Crisis of the Third Century began, Romans had already been fighting with northerners for centuries. Ages before, the Cimbrian War of 113-101 BCE saw the Roman general and military reformer Gaius Marius soundly defeating the Cimbri, but not until they’d secured a foothold on the Italian peninsula. A generation later, Julius Caesar clashed swords with a group from east of the Rhine called the Suebi in 58 BCE, and another called the Nervii in 57, during his long campaigns up in Gaul. After the republic imploded and re-emerged as an empire, the first Emperor Augustus, between 12 BCE and 16 CE, funded wars against tribes seated in modern day Germany, most famously losing a force of 20,000 soldiers in 9 CE at the Battle of the Teutoburg forest, and not quite living long enough to see Romans wage successful campaigns of retaliation later, in the year 16. After the Julio-Claudians had run their course, the Flavian Emperor Domitian found himself crossing swords with northerners often, first in a self-aggrandizing campaign in 82, and later, with tribes in Dacia, whom the Emperor Trajan continued to fight during the first decade of the 100s. The next major conflicts between Rome and its northern neighbors were the Marcomannic Wars, which, between 166 and 180, took up much of the conscious life of the Emperor Marcus Aurelius and saw Roman troops fighting all along the Rhine and Danube frontiers. Though the Romans suffered a crushing defeat at the Battle of Carnuntum in 170, for the next five campaign seasons they pummeled the three main groups that had opposed them during the Marcomannic Wars, with Marcus Aurelius stopping only because a rebellion flared up in Syria.So, to put it in simple terms, between the great Cimbrian War, which ended in 101 BCE, and the Third Marcomannic War, which wrapped up in 182 CE, when Romans fought adversaries from beyond the Rhine and Danube – Romans tended to win. The victories often came at heavy costs. There were rebuffs and defeats on the Roman side, as well as various unsound peace agreements and compromises. But in all of the cases I just described, whether on the Italian Peninsula, or far more often, in the marchlands to the north and east of the Mediterranean, Rome triumphed against the northern armies arrayed against it. The major clashes seemed to have taken place every two generations or so – long enough for northern tribes, or Dacians or Sarmatians to lick their wounds, regroup, form new alliances, and have another go at annexing Roman turf.

Barbarian Invasions during the Third Century Crisis

The first time the Goths made a serious breach of the eastern Danube frontier was during invasions between 250 and 251, certainly a preview of how multiple waves of population migrations would happen in the century and a half to come, and for the remainder of Late Antiquity. Map by Dipa1965.

Barbarians from east of the Rhine and north of the Danube continued their advancement southward as Rome’s Crisis of the Third Century wore on. From the central part of modern day Bulgaria, where they’d beaten the Romans in 251, the Goths set their sights on one of the jewels of the Aegean Sea – the city of Thessalonica. In the year 254 or a little after, Thessalonica came under siege, but Roman militia forces were able to defend it. Seeking softer targets, the Gothic forces wandered southward along the east coast of the Greek mainland, pillaging what they could. The Goths were stopped at the pass of Thermopylae, where Greek and Latin speaking militiamen defended the hot gates 734 years after King Leonidas and his Spartans held it during the Greco-Persian Wars. Following this latter-day battle of Thermopylae, throughout the later part of the 250s and much of the 260s, Gothic forces poured through the opening along the Thracian Danube and they made themselves comfortable.

If the Roman Crisis of the Third Century – again from 238 to 284 – had a crisis within it, this was the years from 259-270. The early 250s had shown the Goths to be a formidable force. Gothic invasions during the early 250s had caused Rome to concentrate its Danube and Rhine troops heavily in the northeast. But in 259, to the northwest, another threat appeared in the form of the Alemanni. One of the many northern coalitions that rocked the Roman Empire during its final centuries, the Alemanni crunched through the thinly defended Rhine fortifications and poured south, making it all the way to the modern day city of Milan, where they were defeated in 259 at the Battle of Mediolanum. Notwithstanding this victory, the year 260 dawned bleak for Rome. A Roman Emperor had died in battle for the first time back in 251, and in the year 260, a different Roman Emperor – this was Valerian, was captured by Persian forces in the southeastern part of modern day Turkey. Valerian’s son, the Emperor Gallienus, tried to hold things together. But in addition to Goths stomping around freely in the ruptured northeast, Persians gobbling up Anatolia, and still Alemanni audibly angry on the other side of Rhine following their defeat, Gallienus, who ruled from 253-268, had to face a number of imperial usurpers.

Historical sources are quite murky for this period. It’s commonplace to remark incredulity that Rome survived the 250s and 260s. The German frontier, or Limes Germanicus, became thin and frayed, and coalitions formed by the Goths to the northeast and Alemanni to the northwest showed barbarians from the north organizing on a greater and greater scale. One simple explanation for why Rome survived has to do with the Cyprian Plague. This pandemic swept through the Empire from around 249-62. Whatever it was – and modern hypotheses commonly include smallpox or influenza – the Cyprian Plague was part of what thinned the military and economy of Rome just as invaders came down from the north. It’s not unlikely that as these same invaders brought the plague back to their homelands, and that the Cyprian Plague struck barbarian territories a little later than it did Rome. Because at the end of the 260s, in a flurry of major battles, Rome fought ferociously to reestablish its Limes Germanicus.

By 267, Rome’s northeastern provinces around the Danube and Black Sea had seen nearly two decades of Gothic boots on the ground. With footholds in modern day Bulgaria and Romania, Goths could sail ships out through the mouths of the Dniester and Danube and into the Black Sea. And between 267 and 269, more Goths poured down through the Hellespont and Dardanelles, raiding the coastal cities of the Aegean often with impunity. In 269, though, Rome struck back against northern incursions on several fronts. The Goths, after pushing southward into the Aegean, suffered a major defeat at the Battle of Naissus in 269 in the southeast of modern day Serbia. Several years later, the Emperor Aurelian officially abandoned Roman claims on certain northern territories along the eastern reaches of the Danube, which helped settle the emergency in the northeast. The northwest, however, was a different story.

As the 260s wore into the 270s, Rome fought a barbarian tribe called the Juthungi, successors to the Alemanni in the northwest. Barbarian troops who crossed the Rhine and western Danube presented a more immediate threat than Goths and Dacians harrying the more outlying provinces of Thrace and Dacia. Thrace was 700 miles east of Rome, across the Adriatic and rugged Balkans, and not a particular concentration of either Roman wealth or population. The gap between the Rhine and Danube – which was a weak point in the Limes Germanicus or German frontier, was less than 500, and in order to attack wealthy urban centers in the Po Valley in the north of Italy, the Alemmani and Juthungi had to march less than 300 miles. This was precisely where Rome fought the Juthungi in 268 – on the shore of Lake Garda, then in 271 near Piacenza, then far down the coast at Fano, and then near Pavia, until finally, thanks to the efforts of the emperor Aurelian, northern Italy was safe for a couple of decades.

Aurelian, though only emperor for five years between 270 and 275, was easily one of Rome’s greatest leaders. He beat the aforementioned Juthungi in northern Italy. He charged into the Balkans, chased Gothic forces back to the north of the Thracian Danube, killed their leader, and restored that part of the river as a fortified border. With unusual foresight, Aurelian fortified Rome with new walls, and then trekked eastward and crushed the forces of a regime based in Palymra, in the central part of modern day Syria – a regime that had speedily gobbled up Rome’s coastal territories in southeastern Anatolia, Syria, the Levant, and Egypt between 270 and 273 while Rome dealt with its problems to the north. Having fended off threats in an astonishing clockwise arc centered in the north of Italy, modern day Bulgaria, and modern day Syria and Egypt, Aurelian then turned his attention to Gaul and Britain, which had broken away in the 260s, and, for good measure, recovered these territories as well. For what may have been the most extraordinary string of victories in Roman military history, Aurelian, in 274, earned the title Restitutor Orbis, or “Restorer of the World.” With the Emperor Diocletian, who came to the throne in 284, the Crisis of the Third Century receives its traditional ending point, although it was Aurelian who held Rome together through the worst years of the crisis. Diocletian’s reign, from 284-305 is most often the traditional beginning of the period we now call Late Antiquity.

The Western Empire, with this ascension of Diocletian in 284, still had two more centuries on its clock. Within those remaining two centuries, the years between 284 and 356, by the standards of the later Roman Empire, were relatively smooth ones, in spite of the immediate failure of the Diocletian Tetrarchy after his death and resulting civil war from 306-324. Civil wars, by the fourth century, were there to stay. The house could divide against itself, and still stand again. But when civil wars were coupled with massive barbarian invasions, when the house divided against itself, outsiders tended to seize rooms and outbuildings. This was what happened increasingly in and after the 370s, with the great Gothic Wars of the 370s, the Visigothic Wars of 402-10, and the Vandal Invasion of Africa in 429.

To zoom out for a moment before we move forward, let’s make a common sense observation. In the Roman empire, during the 200s, 300s and 400s, civil wars and barbarian invasions exacerbated one another. Naturally, civil wars weakened Roman military strength and caused frontier garrisons to become neglected and depopulated, which encouraged northern tribes to push westward over the Rhine and southward over the Danube. In turn, military emergencies led to hasty appointments of unqualified officers with little experience, and of foreign conscripts whose allegiance to Rome was questionable. Rome’s military was always its greatest strength and its greatest weakness, and the more legions were slapdashed together out of disparate elements, the more they were likely to have allegiance to their generals, rather than the unstable political entity staked to the Italian Peninsula. The third century, whose crisis years we’ve just quickly gone through, was filled with what we call “barracks emperors” – generals turned statesmen who seized power with encouragement from their troops. Nearly every important Roman emperor following the Crisis of the Third Century was a barracks emperor, or controlled by a shadowy equivalent of a barracks emperor. Third century barracks emperors like Diocletian, Constantine the Great, Valentinian I, and Theodosius I gave way to fourth century shadow emperors like Stilicho, Flavius Aëtius, Ricimer, and Odoacer, many of them of barbarian extraction. While I want to get into the great Gothic Wars and Vandal Invasion a little later in this program, at this point we can make a very simple observation about fourth and fifth century Roman history. These were centuries whose main events were steered by warlords. Some warlords were Roman generals who’d seized power to become emperors. Some were capable generals wielding de facto power behind the scenes. Others were barbarian generals. Others still were barbarian-Roman hybrids with allegiances to both sides. The word “Rome,” then, begins to be an approximation over the course of the fourth century. More often than not, barbarian tribes from the north, rather than fighting a consolidated political entity, found themselves fighting what we might call Roman tribes beneath an ever-more fragmented patchwork of military leaders. [music]

Barbarians in the Western Empire, 306-370

Earlier in this program, beginning with Septimius Severus’ curtailed campaign in Caledonia, we learned about how Rome’s Crisis of the Third Century created regional power vacuums that northern invaders hurried to fill. The fourth century, which saw Roman Christians enjoying new freedoms and prerogatives in the Empire, also saw nearly continuous strife with barbarians from the other side of the Limes Germanicus. At the epicenter of all of this strife, from 306 to 336, was Constantine the Great. The first Christian emperor’s military career, following campaigns in Britannia with his father, began on the Gallic frontier against Alemanni and Franks between the years of 307 and 310. Civil Wars interrupted Constantine’s campaigns for several years, during which many of Constantine’s newer recruits were made of Celts and northern tribesmen. Thereafter, having won the famous Battle of the Milvian Bridge in 312, between 313 and 315 Constantine was back at the Rhine Frontier, fighting Alemanni and Franks once more. Further victories in civil wars between 316 and 317 increased Constantine’s power, as well as his responsibilities, as he now had to defend the vast territory of Illyricum and Danube frontier, and from 317-323, Constantine fought Sarmatians and built new fortifications south of the Danube. With Sarmatian invasions thwarted, Constantine then turned his attention to the Goths, who continued to cross over the easternmost stretches of the Danube, and in pursuing the Goths, in the year 323, Constantine crossed over into the territory of his co-emperor Licinius. Halting his barbarian campaigns a third time for a civil war, Constantine dispatched the last of his imperial colleagues in the year 324, becoming the sole Emperor of Rome.

A statue of Constantine in York, where Constantine was proclaimed Emperor in 306. He is today most often remembered for a conversion to Christianity, though, like so many of his imperial colleagues during Late Antiquity, a criticial mass of Constantine’s time and energy went into campaigns along the Limes Germanicus.

The mid-330s – maybe – might have marked the restoration of the Empire. The holes in the northern border had been plugged, a new dynasty had been established, no plagues ravaged the provinces, and normal friction with Persians to the east resulted in nothing other a trio of failed sieges in the Roman border stronghold of Nisibus. But the Roman Empire, even as Constantine refashioned it during his long thirty year reign from 306-337, was still living on borrowed time. For one, the barbarian populations east and north of the Rhine and Danube were still growing, and moving, and much of the northern rim of the Empire had accommodated several generations thick of barbarian settlers, invaders and auxiliary troops – in many ways Romans, but in many ways not. And for two, Constantine bequeathed his kingship to his three sons, subdividing it into west, center, and east, and this sort of thing, whether in fable or history, just doesn’t seem to work out very well. Constantine’s eldest son made war on his youngest son in the year 350, and son number one was killed during a campaign against number three rather speedily. Smelling blood in the water, a usurper rose up and killed son number three, making a bid for imperial power. Son number two, the only one who survived at this point, had to fight the usurper, and by the time these two had their showdown in the southeastern part of modern day France in 353, wrapping up the civil war, word had got round among the northern barbarian tribes that Rome was a mess once more, and it was time to invade.

In Gaul, between 355 and 357 what happened next was a paint-numbers invasion and retaliatory campaign, and the star of the show was Rome’s final pagan emperor, Julian. An intellectually and militarily sturdy fellow, Julian the Apostate was a relative of the sole surviving son of Constantine the Great, and after some back and forth in the mid-350s, he was able to swat a large Alemanni invasion out of Gaul toward the end of the decade. A decade later, the Alemanni returned to Gaul, being emboldened by the death of this same Emperor Julian during his campaigns in Persia. But Valentinian I, father of the Valentinian dynasty, was able to beat them in 368. Also in 368, in the extreme northwest of the Empire, a rebellion flared up that nearly destroyed Roman Britain. Tribes from modern day Scotland, Ireland, and Saxons from modern day Germany poured into the towns and villas of Roman Britannia, pillaging the northern and eastern regions of the province. A considerable population of disaffected Roman soldiers and others had turned mutineers and perhaps helped coordinate the uprising. And a general named Flavius Theodosius, father of the future Emperor Theodosius, sorted out the situation over the course of 368.

During 360s, then, Rome focused its attention to the north and northwest – modern day France and England. Elsewhere, though, a thousand miles south and east of the heart of Gaul, and thousands of miles beyond this still, a new wave of population migrations was taking place. And this wave of migrations would break Rome’s sovereignty over the Mediterranean for good. [music]

The Roman-Gothic War of 376-382

Some time around 370, a migration of uncertain proportions and origins happened in the central part of the Eurasian land mass. This migration may have begun as far away as modern day Mongolia, and it streamed westward through Central Asia, it crested the Caspian Sea and avalanched over the Volga before reaching the flatlands of modern day Ukraine. From there it pressed down into modern day Moldova, Romania, Slovakia and Hungary, exerting pressure on the inhabitants of these lands to migrate further to the southwest, into the territories of the Roman Empire. The effect of this double migration was like a hammer and a wedge in these northeastern provinces. The hammer was the Huns, and the wedge was the Goths.The immediate effect of the great Hunnic migration was that a dual population of Goths, the Thervingi and the Greuthungi, showed up on the eastern Danube as refugees in the warm months of 376. The eastern emperor Valens, picturing oodles of brawny new military recruits, allowed the Thervingi to cross the Danube at the eastern end of the border between modern day Romania and Bulgaria, but the Greuthungi were denied entry. Regrettably for all involved, the Romans hadn’t thought through how tens of thousands of refugees might be fed, housed, and gainfully employed, and so the Thervingi, soon starving, desperate and ready to fight, were steered southward to the city of Marcianople in the far central east of modern day Bulgaria. The armed escort that accompanied them necessitated the Danube to lower its guard, and as a result the other large Gothic tribe, the Greuthungi, was able to cross over into Roman territory, and they headed south to join their Thervingi counterparts.

Down at Marcianople, friction between the refugee population of Thervingi Goths and the inhabitants of the city led to the Battle of Marcianople in 376, in which the Romans were defeated. Not having been given much in the way of fair treatment or even basic sustenance, the Gothic refugees pillaged the countryside, cascading south down the Black Sea coast to the city of Adrianople and gathering their possessions into wagons. This was the beginning of the Roman-Gothic war of 376-382. Over the next few years, Roman and Gothic armies clashed numerous times in and around the southeastern part of modern day Bulgaria, fighting to a bloody draw at the Battle of the Willows in 377. The next year, at the famous Battle of Adrianople of 378, near where modern day Turkey, Bulgaria and Greece meet, the Goths beat Roman forces fielded to repel their settlement in Thrace, and the Eastern Emperor Valens, for whom the Goths surely had no love, was killed. Afterward, the Goths laid siege to the cities of Adrianople and Constantinople, though they were unsuccessful. Historical sources become conflicting on what happened next, but however it took place, a population of Goths was permitted to settle within the borders of the Roman Empire, in the northeastern provinces they’d more or less taken by force. The Goths were not, like other peoples settled within the empire, compelled to disband in a specific fashion, and as a result, they became a semiautonomous barbarian principality within the borders of Rome. The wedge that the Huns had driven, then, by 382, was settled in the north central part of the Empire, and a new generation of Goths came of age in the final decades of the 300s, making their homes in a swath of land that sweeps down from modern day Romania, through Bulgaria and perhaps into Macedonia.

It’s worth pausing for just a moment here in roughly the year 382. It is precisely with this generation of Goths born within the borders of the Roman Empire in the 380s and 390s that the distinction between “Roman” and “barbarian” really starts to blur together. Troops of Gothic extraction, henceforth, would be a major presence at all levels of the Roman military, as would Vandals soon thereafter. Northern barbarians had always been yoked into the Roman military, and the empire had become increasingly addicted to them. But in the second half of the fourth century, as Goths emerged victorious in their efforts to settle within the empire, the mass production of a newer type of Roman military man began – one from Roman provinces, who spoke Latin, who wore Roman military insignia and used Roman weapons and tactics, but who also spoke Gothic and had ties to others like him in unassimilated communities in the empire.

Historians have grappled with how to narrate the military history of Rome, even at a high level, after this point. The approaches of scholars like Peter Heather and Adrian Goldsworthy have predominantly understood barbarians and Romans as locked into two sides of a competition for resources around a frontier area. This is easy to understand and the approach works well for, say the Dacian and Marcomannic Wars of the second century. But for later periods, there is a much less clear cut line between Roman and barbarian, and historians like Guy Halsall have explained the catastrophic territorial contraction of the western empire during the 400s as more of a result of systemic political failures, incoherent settlement policies, and scatterbrained provincial governance.10 When you’re a Roman emperor or a provincial governor hosting a large immigrant commune within your borders, made up of people quite willing to move in and assimilate further, but kept subordinate and disadvantaged due to prejudice and demagoguery, it’s kind of your fault when they start looking out for themselves economically and militarily.

Late Antiquity’s Conflagration: The Italian Peninsula, 402-410

Joseph-Noël Sylvestre’s Sack of Rome by the Visigoths (1890), an iconic image from the late antique period. Perhaps the gentleman ascending the sculpture thought he’d be a bit lighter and able to climb better if he removed his clothing in its entirety.

The Italians, on the other hand, had no opportunity for respite. In 405 and 406, a different population of Goths laid siege to Florence, led by a king named Radagaisus. A contingent of Italian forces was able to boot them out – though this contingent itself was made up of a mixture of Romans, Goths and Huns. As Italy winced and paled at the sight of multiple barbarian armies in 406, Gaul was living out its last years as a Roman territory. The tribes headquartered in modern day Germany and Poland, now schooled in Roman technology and military tactics, had not forgotten that all sorts of bounty and opportunity existed on the west side of the Rhine, and a confederation made up of Vandals, Alans, and Suebi crossed over the river, according to one Roman record, on December 31, 406. And while the Visigoths, over the next decades, would pillage Italy and trawl along the Aegean and Mediterranean seacoast, the Vandals would strike a course west through Gaul, southwest through Spain, and then, after crossing the Strait of Gibraltar, eastward into the provinces along the North African coast.

After 406, then, there were multiple autonomous militarized forces operating freely within the borders of the Roman Empire – most importantly the Visigoths, rooted in the northeast Balkan Peninsula, and then the Vandals, initially seated in Gaul. Between 409 and 410, Alaric the Visigoth conducted his historically famous campaign in modern day Italy, which resulted in the sack of Rome in August of 410. Though Ravenna was the capital of the western empire by this time, 410 was the first time the city of Rome had been sacked in ages, and theologians like Saint Jerome wrote about the sack as an event of apocalyptic proportions. It’s important to remember, though, that Alaric’s most famous invasion of the Italian peninsula was a Roman civil war, and not a bunch of bearded musclemen suddenly appearing in furs with war hammers. As he sacked the city, Alaric would have worn the Roman insignia of a magister militum – something like a Chairman of a Joint Chiefs of Staff, and he sacked the city because he sought back pay for the Roman-Gothic army that he led. Two years of fraught negotiations with the Emperor Honorious had been unsuccessful, and so Alaric, according to many sources acting with incredible restraint, breached the city walls and removed its choicest valuables, sparing lives and allowing residents refuge in city churches. As Alaric and the Visigoths struck at the ancestral heart of the Empire, Vandals, who’d been ravaging the Gallic provinces for several years, crossed over the Pyrenees in 409, fighting Roman-led consortiums in the Iberian peninsula for the next two decades before moving into North Africa in 429.

A small snapshot of Vandal movements through Gaul and Hispania following the Visigothic sack of Rome in 410, demonstrating how quickly barbarian settlers were moving through Roman territories by the early fifth century, as Late Antiquity’s centuries wore onward.

The Huns Beneath Attila

The Huns were horse archers. Scholarship on their origins today is inconclusive, as well as whether they thought of themselves as an ethnic group, or whether the term “Hun” simply served as a formal title signifying allegiance to a diverse organization of nomads. Whoever they were, wherever they’d originally come from, they showed up around 370. As the Goths dug into the northeastern Balkans, and Germanic tribes crossed the Rhine into Gaul, beginning in 395, the Huns thundered into the Eastern Empire, battering Armenia and parts of northern Anatolia, then down into Syria. You may have noticed as we reviewed some of the history of the great migrations that as Rome suffered the invasions of Goths and other Germanic tribes from 370-430, things were rather quiet on the eastern frontier with the Sasanian Persians. This quietude was partly due to the Huns, equal opportunity invaders who found Persian gold just as shiny as Roman gold, and ventured into the Sasanian Empire at multiple points during the fifth century, giving the kings of Persia plenty to deal with.

The Huns’ center of operations during the life of Attila (d. 453) and the core of some of Late Antiquity’s most famous invasions. Map by Slovenski Volk.

Twenty years later, the jig was up for trans-Mediterranean Roman leadership. By 476, the Visigoths had settled in Spain and southwestern France. The Vandals held North Africa, Corsica, and Sardinia. Italy had become a transient monarchy under the barbarian slash Roman usurper Odoacer. Modern day England, by 476, was home to a splash of Angles, Saxons, and Jutes who’d crossed over during the fourth and fifth centuries. Modern day France, again in 476, had become a patchwork of tribal territories – Burgundians, Franks, Saxons, and Alemanni. But in this same year, the Eastern Empire still held strong, with the southern and eastern Balkans, Anatolia, Syria, the Levant, Egypt and Libya still under the control of Constantinople.

We will talk about the early Byzantine Empire in a moment, as this season of the podcast will also deal extensively with the 500s and 600s. But before we do, we should make some common sense observations about all of the historical events we’ve just discussed. Between the 200s and 400s, the Western Empire collapsed due to two recurring and very obvious problems. The first was that by the end of the 200s, the empire had completely dispatched with the old republic’s system of checks and balances for executive power. It first devolved into a hereditary monarchy, and then decomposed further into a long sequence of military coups led by warlords whom in hindsight we’ve historically called emperors. The second was that ongoing population migrations rooted in northern and eastern Europe and Central Asia pressed southward and westward into the Mediterranean during the 200s and 300s – migrations persistent enough to overwhelm the empire even when it was at its best. These factors – not Christianity, nor pagan decadence, nor the fresh brawn of barbarians mastering an overripe civilization, were what led to the major demographic and political shifts in the organization of Mediterranean civilization commonly shorthanded as the fall of Rome. [music]

The Byzantine Empire During Late Antiquity

With the collapse of the western empire in the fifth century, and the contraction of Roman imperial governance to a much smaller region in the eastern Mediterranean, seated in Constantinople, we will need to readjust our strategy for learning Late Antique history between 500 and 700 CE in the remainder of this program. Beginning in Constantinople, in the rest of this show we’ll concentrate on four geographical areas pertinent to this podcast’s coverage of literary history toward the end of Late Antiquity. These areas will be the Byzantine Empire in the east, and then territories that today lie within North Africa, Italy, and France, and we’ll try to get a sense of what happened in each region during and after the 400s, up to about 700. So let’s begin with the Eastern, or Byzantine Empire.The history of the Byzantine Empire, in a sentence, is that it rose up between about 300 and 500 as the eastern half of the Roman Empire, gradually embraced Greek over Latin, became the heart of Eastern Orthodox Christianity after 1054, and persisted as a continuous political entity, incredibly, until 1453 – nearly a thousand years after the fall of the western empire. Its heart was the strategically located city of Constantinople, which is of course modern day Istanbul. Before the spread of firearms, Constantinople was one of the most militarily defensible spots in the world, a narrow isthmus of land to its northwest, churning seawater on all other sides, a river running into it, multiple harbors, and excellent fortifications all around. While military defensible, the city was also located on one of the most important waterways on earth – the Bosporus Strait, where shipping traffic from the Black Sea winds into the Mediterranean, and ultimately, where trade routes from Asia could most efficiently move into Europe prior to steam power. The Emperor Constantine, in the year 330, declared the city as the new capital of the Roman Empire. Over the third and fourth centuries, the Empire was increasingly subdivided between co-rulers on an official level before the western empire collapsed and the eastern empire persisted at the end of the 400s.

The Byzantine Empire in 555 CE, after the campaigns of Justinian and Belasarius, at the maximum extent of territory it would cover. This famous summit of Roman power during Late Antiquity was to be quite short lived. Map by Tataryn.

In the crucial century of the 400s, Constantinople had some other advantages. Theodosius I, upon his death in 395, had bequeathed the Empire to two sons – Honorius in the west, and Arcadius in the east. While both sons had to deal with major crises, the ones plaguing the east were much more successfully contained. The Theodosian dynasty in the west, which ended in 455, saw the Italian Peninsula clobbered like a punching bag by Goths, barbarian armies slicing through Gaul and Spain, and Vandals conquering North Africa, not to mention a daisy chain of imperial usurpations, giving way to a final sputtering of nine western Emperors in 21 years. In contrast, the Theodosian dynasty in the east, which ended in 457, saw the Huns having run out of steam, relative peace with the Sasanian Persians, and the famous Theodosian Walls erected around Constantinople – walls which would prove useful again and again in coming centuries. What followed this dynasty in Constantinople was the Leonid Dynasty of 457-518, the Justinian Dynasty of 518-602, and then the Heraclian Dynasty of 610-695.

Perhaps the single most important thing that can be said about the Byzantine Empire at the end of Late Antiquity is that though it fought harrowing wars and suffered usurpations, it remained one thing, seated in one place. While maps of Central and Western Europe begin to look like amorphous watercolors between 500 and 700, the Byzantine Empire knuckled down in Constantinople, expanding once, thrillingly, under Justinian, such that by 555 much of the old Roman Mediterranean rim had been recovered. But just as dizzyingly, the Byzantines had lost nearly all of their territory by the time of the second Arab Siege of Constantinople in 717. Even after this, though, Constantinople retained control of most of Anatolia and a smattering of Aegean and Adriatic ports, later recovering territories that it had lost to the Caliphates over the next couple hundred years. A seemingly indestructible knot of eastern Christianity, the Byzantine Empire was the long distance runner of European history.

It also remained an intellectual and theological powerhouse, even when turbulent decades rocked western and central Europe. The Byzantine Emperor Theodosius II founded the University of Constantinople in 425, and his law codes later became the basis for the Emperor Justinian’s law codes a century later, which in turn had a long lifespan in later European history. The scriptoriums and libraries of the Byzantine Empire hummed with activity for centuries, leading to the preservation of much of the Ancient Greek literature and philosophy we still possess today. And while the curation of Greek manuscripts was one of the Byzantine Empire’s greatest gifts to posterity in the long run, in the short term, during Late Antiquity, a lot of crucial theological activity took place within the boundaries of the Byzantine Empire that shaped the future of Christianity. In fact, every single one of the first seven ecumenical councils of Christianity took place in the east, with three of them in Constantinople itself, and six of seven of them in Anatolia. The center of the Monophysite and Monothelitist controversies – theological controversies about the nature of Jesus – was Constantinople, and Constantinople’s bishops and emperors played formative roles in shaping Christian doctrines, especially during the tail end of Late Antiquity.

So, that will have to do for a very quick introduction to Constantinople and the Byzantine Empire during the latter half of Late Antiquity – a geographical region that once again expanded and contracted dramatically at different points between 500 and 800, but managed to continue being Christian and Roman even as the social fabric of the Mediterranean and Middle East transformed all around it. Let’s move on, now, to North Africa. [music]

North Africa and Late Antiquity

As of the year 476, when the western empire officially collapsed, two powers held sway over what had previously been a string of North African provinces along the southern Mediterranean Coast. The Byzantine Empire continued to reign in Egypt and a northeastern coastal stretch of modern day Libya. But the fertile stretch of coastline that extends from Carthage in modern day Tunisia over to the border of modern day Algeria and Morocco, along with Corsica, Sardinia, and the Balearic Islands had become Vandal territory. As a side note, it is a little funny to imagine Vandal barbarians coming down from modern day Germany and getting sunburns on the sandy beaches of Ibiza and palm groves of Tunisia, but Late Antiquity presents us with stranger sites than this one.

The Vandal kingdom in Late Antiquity, having reached the fullest geographical extent that it ever would, in the 470s. Map by Hannes Karnoefel.

Over the course of the past hour or so, as we’ve reviewed the major population migrations and military conflicts that led up to the fall of the western empire, you’ll have noticed that North Africa hasn’t come up too often. The Roman Empire certainly had no safe, utopian provinces, but over the 200s, 300s, and some of the 400s, the African provinces were spared foreign invasions and major wars, though of course plagues, economic crises, and the poaching of young men for military service affected everyone. As a result, the African provinces became a powerhouse of religious activity, nourishing Christianity, Gnosticism, and Manichaeism, and producing, most famously, the church fathers Tertullian and Augustine, about whom we’ll have much to say in future episodes – a whole lot of Late Antique intellectual history is anchored in North Africa.12

Anyway, the Vandal invasion of North Africa began in 429 with the crossing of the Strait of Gibraltar, and again crescendoed a decade later with the annexation of Carthage in 439. While it was as disruptive as any foreign conquest and subjection of a native population, the invasion had an especially malignant dimension to many of the region’s Christians. The Vandals, like the Visigoths and Ostrogoths, were not Nicene Christians, but instead most often Arian Christians. As a quick reminder, Arians had a subordinationist ideology – that Jesus was younger than, and lesser than Yahweh, whereas Nicene Christians held the Trinitarian view that the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit were consubstantial and coeternal. Christian theologians had been encamped on either side of this Christological schism since roughly 300, and the Council of Nicaea in 325 led to the promulgation of Nicene Christianity as official Catholic doctrine. Anyway, with the Vandals being Arians, and a critical mass of North African communities, like the bishopric of Saint Augustine, being Nicene, unfortunately after 429 the Nicene-Arian rift often turned violent, with Vandal rulers prosecuting Nicene subjects.

Treating subjects poorly was one of the reasons the Vandal kingdom didn’t last very long. The most famous event of the 500s might be the Byzantine Empire’s reconquest of the west under the Emperor Justinian and his general Belisarius, a vast military campaign that stretched from 533 until 555. This campaign began with the successful ouster of the Vandals from North Africa in 533. The Byzantines knew that the North African territories were, as ever, an agriculturally productive region that, once conquered, could be easily held by a naval power. Sweeping up North Africa first, over the 530s, 540s and 550s the Byzantines advanced into Corsica, Sardinia, Italy and the rim of the Adriatic, and eventually took back a part of Spain. Amazingly, while all of this was taking place during Justinian’s reign, a sequence of catastrophes struck the Late Antique world that seem Biblical in their proportions. Between 535 and 536, massive crop failures occurred. Contemporary historical accounts record eighteen months of feeble sunlight and atmospheric haze, likely caused by a volcanic eruption. Wherever the eruption occurred, famine and recession rattled civilization on a global scale as a result. And the famine of the mid-530s gave way to something much worse in the 540s – the Justinian Plague.

Justinian I (482-565), one of the most influential people in Late Antique history, in the famous mosaic in the Basilica of San Vitale in Ravenna.

But to return to the subject of North Africa, after the year 533, the Vandal kingdom was brought beneath Byzantine sway, but this territorial acquisition happened right on the eve of the aforementioned disasters, such that any benefits Constantinople experienced from snatching up African farm fields must have been severely hampered by the climatological crisis and famine of 535-6, and the plague of the next decade. Not long after Justinian and his general Belisarius gained control of North Africa, the region became an Exarchate, or a semiautonomous provincial territory beneath Byzantine sway, and it remained as such up until the end of the seventh century. The Byzantine Exarchate of Africa, which lasted from 533-698, was a relatively peaceful and prosperous place and time in Late Antiquity. No hostile neighbors to the south, excepting occasional friction with Berber tribes, together with homegrown food, meant the North African coast could defend and feed itself more easily than other regions of the Byzantine Empire.

The most famous event to unfold in relation to the Byzantine Exarchate of Africa was the rise of a new dynasty. The long Justinian Dynasty, which lasted from 518-602, gave way to a usurper named Phocas. Before Phocas could start putting heirs on the throne, however, the Byzantine Exarch of Africa revolted in 608. His name was Heraclius the Elder. Seated in Carthage, Heraclius the Elder knew he and his son had excellent advantages. The Byzantine capital of Constantinople was mired in a grim juncture of the 30-year Sasanian-Byzantine War, which lasted from 602-628. In contrast, Carthage, where the Exarch of Africa Heraclius the Elder was seated, was more isolated, defensible, and it produced its own food. Between 609 and 610, Heraclius the Elder made a bid for executive leadership of the Byzantine Empire, and the usurper emperor Phocas, seated in Constantinople, battered by war with the Sasanians and deprived of African foodstuffs, was executed in the autumn of 610. This revolt, which began the Heraclian Dynasty of 610-695, seated Heraclius the Elder’s son Heraclius on the throne at Constantinople, where the younger Heraclius would remain for three decades.

The younger Heraclius’ schedule was consumed for a long time by the Byzantine-Sasanian War of 602-628. This war came to its conclusion in 627 with the Battle of Nineveh, which Heraclius the Younger won, using his advantage to press more deeply into Sasanian territory over the next year. The emperor did not, however, get much of a chance to enjoy territories retaken from the Sasanian Empire. The Byzantine-Sasanian War coincided with the ministry and rise of the Prophet Muhammad, who, by the year 629, had unified much the Arabian Peninsula into a military body beneath central leadership. In the year 629, Muslim armies marched up into Byzantine and Sasanian territory, and later that year had crossed swords with the Byzantines for the first time at the Battle of Mu’tah, in the west-central part of modern day Jordan. As for the Sasanian Empire, pummeled by thirty years of war with the Byzantines, it fell to Muslim armies in 651 after nearly two decades of territorial and military losses. Arab incursions into North Africa commenced in 647, and they culminated with the Muslim sack of Carthage in 698. The Byzantines would not recover North Africa again.

In the long run, then, North Africa played quite an important role in the early history of the Byzantine Empire. Once seized from the Vandals in 533, the Exarchate provided Constantinople food to eat and wealth to help support defense of its more fractious frontiers. Though it was the source of a coup from 608-610, this coup ended up being the mechanism that changed the Justinian Dynasty, which ruled in Constantinople for most of the 500s, to the Heraclian Dynasty, which ruled in Constantinople for most of the 600s. Through the Byzantine-Sasanian War of 602-628, and then the Arab conquests of Byzantine Syria, Egypt, Libya and the rest of North Africa, while they held it, the Byzantine Exarchate of Africa was a reliable source of food and tax revenue for the empire. It’s no coincidence that the next imperial entities that held North Africa, the Umayyad Caliphate, and especially the Abbasid Caliphate, had enormous staying power, holding sway over a large stretch of territory up until the thirteenth century. Like the Romans before them, they found the fertile belt of coastland that stretches from modern day Tunisia in the west to the Nile in the east well worth the effort it had taken to conquer it. [music]

The Italian Peninsula and Late Antiquity After 476

With the Late Antique history of the Byzantine Empire and North Africa quickly reviewed, let’s move on to talk about what happened on and around the Italian Peninsula after the western empire collapsed in 476. In a sentence, it became the kingdom of a barbarian named Odoacer from 476 to 493, then a part of the Ostrogothic kingdom from 493 to 553, the tail end of this period being consumed by the Byzantine-Gothic War of 535 to 554 under the Emperor Justinian, and finally, beginning in the 560s, most of the peninsula fell under the control of a tribe of people called the Lombards up until 774. Let’s go through these major phases of Late Antique history in Italy in a bit more detail, though.As mentioned a second ago, a barbarian king named Odoacer, likely with some roots in modern day Germany, ruled Italy from 476-493. The most famous thing Odoacer ever did was to depose a child emperor named Romulus Augustulus and then send the Byzantine Emperor Zeno an embassy that included the western Roman Emperor’s insignia, with the message that the west no longer required an emperor. This event is a perfectly logical place to mark the end of the western empire, but in context, it was more of an attempt to conciliate the Byzantine Emperor and ensure him that business as usual would continue in Italy than it was a roar of barbarian independence. Due to his tactful conduct toward the Byzantine Emperor, Odoacer was decreed a patrician, and he enjoyed backing from the Roman Senate, carrying forward the operations of the western empire’s state system that still survived in the late fifth century.

Odoacer was no mere Byzantine puppy, though. While he deferred to Constantinople on paper, and even propped up a western emperor named Julius Nepos, who had been deposed back in 475, Odoacer was still doling out land to his people. In 480, after Nepos was murdered, Odoacer directed his forces into the province of Dalmatia, along the central eastern Adriatic shore, in order to get revenge on the conspirators. Odoacer ended up making himself comfortable there, conquering some of the province and expanding his territory. This act, probably together with other affronts lost to history, set off the alarm bells of the Byzantine Emperor Zeno, who decided to employ one of Rome’s oldest and most successful strategies – getting threatening enemy forces to kill one another.

By the fall of the western empire in 476, one branch of Goths, the Visigoths, or “western Goths,” had settled in what is now southwestern France and large parts of Spain. The other branch, the Ostrogoths, or “eastern Goths,” had been settled in a province called Pannonia, in and just east of modern day Slovenia, where they maintained a cohesive and independent body within the empire’s borders. In the early 480s, when the Byzantine Emperor Zeno began to sour on Odoacer and Odoacer’s potentially expansionist desires, Zeno knew that the Ostrogoths were parked right between Byzantine territories, with the central and eastern Balkans to their east, and the Kingdom of Odoacer to their west. The Byzantine Emperor Zeno made overtures to the Ostrogoths by contacting a man named Theoderic. Theoderic the Great, an Ostrogothic noble who’d received a Roman education as a hostage in Constantinople, was another one of Late Antiquity’s remarkable hybrid creations. Ten years spent in the eastern court had given Theoderic a patrician’s education, and Theoderic enjoyed Latin poetry as well as Christian theological debates. Thus, like so many Late Antique quote unquote barbarian monarchs, Theoderic was essentially Roman in many ways. Recognizing Theoderic’s talents, the Byzantine Emperor Zeno sent him to gain control of Italy. By 493, Theoderic had defeated and killed Odoacer and made Italy into Ostrogothic territory. We’ll meet Theoderic and his world at great length in a future program on the philosopher Boethius. For the present, it will suffice to say that Theoderic proved a force to be reckoned with for the Byzantines, expanding Ostrogothic operations in the northwestern Balkans, and securing control of the Visigothic kingdom.

Fluent in the cultural worlds of both the Byzantines and the Goths, at the height of his power, Theoderic ruled territories from the Atlantic Coast to the central Danube. Upon Theoderic’s death in 526, however, the delicate balance he’d struck to hold the Byzantine and Gothic worlds together began to unravel, as the Visigothic kingdom to the west came under the sway of one of his grandsons, while the Ostrogothic kingdom to the east became the territory of another. Theoderic’s daughter Amalasuntha tried to carry her father’s deft balance between Byzantines and Goths forward, but times were changing. For one, the Byzantines, less than a year after Theoderic’s death, were under the reign of Justinian I, that ultra-expansionist monarch set on restoring the Roman Empire of old. And secondly, as Justinian made his first efforts at doing so, ordering expeditions into Vandal Africa, many of the Ostrogothic citizens of Italy and Sicily winced at the sudden resurgence of the Byzantine Empire into the central Mediterranean. Key barbarian aristocrats of Odoacer’s and Theoderic’s generations had clearly believed that a Gothic regime could flourish and could continue Roman governmental operations, cooperating with Constantinople. These optimistic Goths were ultimately disappointed. Over the next generation, the Byzantines made war on their previous Ostrogothic allies in Italy, expansionism and nostalgia supplanting the previous generation’s pragmatism.

Italy beneath the Lombard monarch Agilul (c. 600). The Byzantine Exarchate of Ravenna still cut a Roman stripe through the center of the Peninsula at Late Antiquiy’s end.

Not long after the Byzantine-Gothic War of 535-554 was over, a northern confederation called the Lombards showed up in northern Italy, flanked by allies that included Saxons, Bulgars, and Ostrogoths. They began conquering cities in the Po Valley to the north in 569, including the onetime capital of Milan. City after city followed over the next few years. By the mid 570s, Lombards held many of the interior portions of the peninsula, with Ravenna and Rome, and a little corridor between them, still held by the Byzantines. This territory was called the Byzantine Exarchate of Ravenna. As the 500s and 600s stretched forward to the 700s, the Byzantines also managed to cling onto Sicily, Corsica, Sardinia and little pockets of the Italian coast and Adriatic coasts. The Italian Peninsula, however, after 570, was often a factional checkerboard of duchies, with Arianism, Catholicism, and paganism exacerbating regional and ethnic differences, and clashes with outsiders like the Franks, Slavs and Byzantines destabilizing the old Roman heartland even more.