Episode 89: The Aethiopica of Heliodorus

Heliodorus of Emesa (3rd/4th century CE) wrote the longest novel to have survived from antiquity, an adventurous romance that reemerged into Europe in the 1500s.

| Read Transcription | References and Notes |

| Episode Quiz | Episode Song |

| Episode on Spotify | Episode on Apple Podcasts |

| Previous Show | Next Show |

Heliodorus’ Aethiopica: Antiquity’s Longest Surviving Novel

Gold Sponsors

Andy Olson

Jeremy Hanks

John David Giese

ML Cohen

Silver Sponsors

Alexander Silver

Chad Nicholson

Francisco Vazquez

John Weretka

Lauris van Rijn

Michael Sanchez

Anonymous

Patrick Radowick

Steve Baldwin

Mike Swanson

Sponsors

Aaron Burda

Alysoun Hodges

Amy Carlo

Angela Rebrec

Ariela Kilinsky

Benjamin Bartemes

Brian Conn

Caroline Winther Tørring

Chloé Faulkner

Chris Brademeyer

Chris Guest

Chris Tanzola

Daniel Serotsky

David Macher

D. Broward

Earl Killian

Ethan Arsht

Henry Bakker

Joshua Edson

Kyle Pustola

Laurent Callot

Leonie Hume

Mark Griggs

Murilo César Ramos

Natasha Worle

Oli Pate

Anonymous

Anonymous

Robert Baumgardner

Rod Sieg

De Sulis Minerva

Sebastiaan De Jonge

Sonya Andrews

Steven Laden

Sue Nichols

Susan Angles

Tom Wilson

Tray Davis

Verónica Ruiz Badía

The Aethiopica is part of a body of ancient Greek novels and novellas that survive from roughly 50 to 300 CE. These novels and novellas are often called “romances” – both in the sense that they generally contain love stories, but also, in the medieval sense that they are fantastic adventure sagas. In the pages of these novels, brave and beautiful heroes and heroines navigate their ways through unjust and threatening worlds, their virtue and love for one another the only constants in shifting landscapes of villains and perils, and from time to time, kindly and supportive allies. The standard anthology of all of these works, scholar B.P. Reardon’s Collected Ancient Greek Novels, contains what survives from this genre – nineteen works in total, six of them complete, and the rest in various states of fragmentation. Of all of these, the one we’re reading today, again Heliodorus’ Aethiopica, is the longest, and once it reemerged into European literary history after the sixteenth century, it became one of the most influential. To be clear here at the outset of this show, the other romantic adventure novels that survive in Greek in complete form from the period are Chariton’s Callirhoe, from the mid first century, Xenophon of Ephesus’ Ephesian Tale, from the mid second century, Achilles Tatius’ Leucippe and Clitophon, from the late second century, Longus’ Daphnis and Chloe, from some time in the second century, and then our book for today, Heliodorus’ Aethiopica.2 I will take the liberty of guessing that the vast majority of those out there listening haven’t heard of these. When literature people like me talk about the first novels, oftentimes, we do it with a certain myopia, our histories of long prose fiction beginning around the time of Cervantes’ Don Quixote in 1615, our assumptions being that seventeenth-century pioneers gave rise to a tradition that flowered in the eighteenth century. The more adventurous of us might cite the Japanese classic The Tale of Genji, an eleventh-century saga set at the end of classical Japanese history. And while Don Quixote and the Tale of Genji are marvelous, important works, to say that either of them is the first novel, or even an early novel, is demonstrably false.

Long form prose fiction emerged in the pre-Christian world, likely in the last two centuries BCE.3 The earliest novellas and novels are now lost. The genre, as we saw last time, was perhaps a confluence of theatrical New Comedy plots together with the fanciful elements of prose works of history and geography. Roman playwrights like Plautus, by 200 BCE, were already staging romantic comedies about virtuous young people adrift, and virtuous young people adrift are the subjects of most of the earliest novels that have survived. In a separate tradition, as early as Herodotus, ancient historians were liberally fusing fact with fiction, and ancient works of geography and travel narratives offered sizable helpings of fairytales about fantastic creatures and societies in faraway India, Arabia, sub-Saharan Africa, and beyond. Long before 200 BCE, antiquity had already produced oodles of what we would today consider fiction – the Iliad, Odyssey, Argonautica, and on and on. But these were works in verse, and not prose, and they were works that were considered to have some basis in fact, even if that fact was heavily embroidered by poetic mythmaking. In contrast, the first novels would have been understood explicitly as fiction – a sophisticated, but overall recreational body of texts for a readership who appreciated erudition and a clever turn of phrase, and wanted something a bit more modern than Homer.4

Long before Victorian era Anglophone fiction about innocent young people finding their way in the world, like Dickens’ Oliver Twist (1838), by Heliodorus’ time in the 200s or 300s, a well-established tradition already existed of long prose works about orphans, foundlings, and naive youths making their ways through perilous worlds.

To those of us, then, who mention Don Quixote or The Tale of Genji as the inaugural novel, the very existence of Ancient Greek novels comes as something of a surprise. The ancient prose romance was so established and well known that by the mid-300s, the Roman scholar-emperor Julian wrote of novels as blasé and frivolous. Julian wrote, in roughly the early 360s CE, “But for us it will be appropriate to read such narratives as have been composed about deeds that have actually been done; but we must avoid all fictions in the form of narrative such as were circulated among men in the past, for instance tales whose them is love, and generally speaking everything of that sort.”5 By the year 400, then, the romantic adventure novel was not only not novel – it was a relic, and a literary tradition that had already come and gone. Prose fiction was exploding in other genres – hagiographies, apostolic acts stories and apocryphal gospels, but these were written with the intention of having theological heft or even a grain of inspired truth, whereas ancient Greek novels, as a general rule, were clearly set down just for fun.

It’s astonishing, then, that Heliodorus and other ancient novelists like him aren’t better known even within the circles of specialists. While the ancient Greek novels have become better known over the past three decades, they have long been a sort of dark horse of classics – a genre considered the decadent product of an overeducated Greek underclass, too modern to be set adjacent to Golden Age Latin or Classical Greece, and too ancient and Byzantine to be wrangled into studies of the European Middle Ages. Yet ancient Greek novels are far too interesting and important to be omitted from any literary history. They were not only part of a major literary movement in the first few centuries CE. When Heliodorus and other ancient Greek novelists appeared in Renaissance translations in the sixteenth century, a number of them went on to exercise a formative influence on writers of the Early Modern period. Shakespeare alludes to Heliodorus in his play Twelfth Night.6 Philip Sidney based his prose epic, the Arcadia, on Heliodorus. Aphra Behn’s Oroonoko yanks plot and character liberally from Heliodorus. And speaking of Cervantes, Cervantes’ final novel, The Travails of Persiles and Sigismunda is itself largely modeled on Heliodorus’ Aethiopica. The ancient Greek novel that we will read in a moment, when it emerged into European literature in French in 1547, then Latin in 1551, and English in 1587, was part of a watershed epoch in literary history.7 A century of once-lost Latin and Greek texts had already flooded into the literate circles of Europe. The lush prose and exotic settings of Heliodorus, his tableaus of a lost pagan world, his outrageously complex plots, his wickerwork of familial and past connections lost and found again – it was all a treasure trove as dawn broke over the seventeenth century. These things had been made available prior to Heliodorus’ reemergence, but in the nearly 300 pages of Heliodorus’ Aethiopica, Shakespeare and his generation found a lost world in a single volume, and what they did with their findings changed literature forever. [music]

The Background of Heliodorus’ Aethiopica

Before we get into the Aethiopica, let’s spend a moment going over what we know about this novel, starting with its author. On this subject, we basically know nothing. He calls himself Heliodorus in the novel’s final sentence, and identifies himself as “a Phoenician from the city of Emesa.”8 Emesa was modern day Homs, Syria, which would make Heliodorus a provincial from the farthest eastern territories of the Roman Empire, like the star of our previous two shows, Lucian of Samosata. That’s about as much as we know for certain. From the Aethiopica itself, we can tell that Heliodorus is quite well versed in Ancient Greek literature, and that he’s also comfortable with a variety of textual sources on the subject of Ancient Mediterranean geography. The plot of the novel takes place mostly in Egypt and Ethiopia – Ethiopia and its monarch come across very positively, overall, and so Heliodorus may have had some personal ties to the region, though there’s certainly no way to tell for sure. As a writer, Heliodorus shows himself inexhaustible with plot innovations and talented in his language – translator J.R. Morgan explains that “Heliodorus wrote wonderful Greek. . .The style is florid and artificial, but exuberant and alive, employed with a zest and love of words and the games that can be played with them.”9 And that’s about all we can say about Heliodorus of Emesa for certain. A fifth century church historian tried to claim that Heliodorus of Emesa, author of the Aethiopica, was the same person as a Greek bishop, but there’s no whiff of Christianity in the Aethiopica, and so this particular claim seems doubtful.10

This map displays all the main locations featured in the Aethiopica – the northwestern Nile Delta, Memphis, Syene (Aswan, just north of the first cataract), and Meroe (at the very bottom of the map. Map courtesy of Jeff Dahl.

Now, before we begin, let’s go over a few must-know things in the novel. First, let’s meet the heroine and the hero – the anchors of the story. These two characters are called Charikleia and Theagenes. Charikleia, the heroine, is the center of the book – she’s a beautiful young woman, seventeen years of age, and her inordinately complicated past only gets revealed about halfway through the novel. Her lover is Theagenes, a Greek youth from Thessaly, about the same age, athletic, virtuous, and, like Charikleia, blindingly good-looking. There are two other characters I want to introduce to you upfront, because the Aethiopica actually has quite a large cast. The other two characters include a young Greek man from Athens named Knemon – he is involved with the adventures of Charikleia and Theagenes for several books. And the final one to know is an Egyptian high priest named Kalasiris. Kalasiris, we learn in a long flashback in the novel’s first half, was instrumental to beautiful young Charikleia’s upbringing at a certain point. So that’s the heroine, Charikleia; the hero, Theagenes; the Athenian guy whom they meet early in the novel, Knemon; and then Kalasiris, the Egyptian high priest who offers a huge swathe of history about the heroine and hero of the novel.

And speaking of flashbacks, Heliodorus’ Aethiopica begins in the middle of things, with a pretty spectacular opening. Soon, the novel doubles back to let you know how events unfolded prior to Page 1. While the novel wiggles a bit between past and present at its outset, its overwhelming focus is on Charikleia and her lover Theagenes. While the Aethiopica was written during the 200s or 300s CE, the book was set quite a bit further back than that – some time in the 500s BCE. That brings us to the subject of the novel’s setting – where it physically takes place.

This book basically takes place in a scattering of settlements along the Nile. Its opening scene is the spot where a northwestern channel of the Nile Delta empties into the Mediterranean, where Charikleia and Theagenes have shipwrecked. A long flashback scene pretty soon thereafter recollects events that took place mainly up in Delphi, Greece, and this flashback scene takes place in a merchant’s house in a village along the Nile. A pivotal part of the novel’s action then unfolds in the Egyptian city of Memphis, ten or fifteen miles south of what’s today downtown Cairo. And the closing episodes of the novel take place further still to the south along the Nile, in modern day Sudan, back then the kingdom of Ethiopia. While Egypt is a fairly straightforward location, there’s just one other complexity to be familiar with ahead of time. The Aethiopica is set during a period in which a Persian imperial regime was ruling over Egypt. The Achaemenid Persians took over much of Egypt in 525 BCE, and they ruled there until the end of the next century, and so in the pages of the Aethiopica, we often read about Persian ruling officials tramping their boots over Egyptian soil. The novel comes to a climax at the moment when the Persian regime currently ruling over Egypt tries to go a little further to the south, and comes into conflict with the formidable might of the Ethiopian army to the south.

Well, with all of that background, I think we’re ready. Unless otherwise noted, quotes in this program will come from the J.R. Morgan translation, published in that terrific anthology Collected Ancient Greek Novels by the University of California Press in 2019. [music]

Heliodorus’ Aethiopica, Book 1

A Shipwreck and a Battle

Heliodorus’ Aethiopica begins, like the Homeric epics, in the middle of things. Here’s the opening of the novel, in the Moses Hadas translation.Day had begun to smile and the sun was shining among the hilltops when a band of armed pirates scaled the mountain which extends to the mouth of the Nile called the Heracleot, where it empties into the sea. They halted for a little to survey the waters which stretched before them. Out at sea, where they first directed their attention, not a sail was stirring to whet the pirates’ appetite for plunder; but when they turned to look at the coastline nearby their eyes encountered a strange spectacle. . .A merchant ship lay moored by its hawsers, bare of crew but heavily loaded, as was easy to conjecture, for its weight pressed the ship down until the water reached its third loading line. The beach was strewn with fresh carnage; some of the victims were dead, of others the limbs were still quivering; obviously the battle had been recent.12

Adrien Manglard’s Shipwreck (1715). Adventure narratives of the Roman Empire (including the canonical Book of Acts!) are replete with shipwrecks – Heliodorus begins his novel by using this plot staple right away.

An extraordinarily beautiful girl stood over the fallen form of a handsome youth. He was still alive, and the fraught conversation between the two was interrupted by the arrival of the bandits. The girl leapt up, appearing suddenly even more magnificent and formidable. She told the bandits that if they were not ghosts, they should just kill her and her companion, but the bandits left her under guard and began plundering the beached ship. To everyone’s surprise, a second group of bandits suddenly arrived on horseback, and these chased off the first. These bandits, too, were awestruck by the young pair’s beauty and resoluteness in the face of whatever tragedy the two had endured. Nonetheless, they abducted both the beautiful young girl and her companion, and led them westward along the shore.

Soon, the bandits and their captives arrived at a sprawling wetland settlement centered on a deep lake – the veritable capital, Heliodorus tells us, of all the bandits of Egypt, ringed with thick reeds and other natural barriers unnavigable to any but the brigands themselves. The beautiful girl and her companion were neither abused nor disrespected – in fact, they were put in the company of another captive who also spoke Greek. Thus given the dubious security of lodgings in the bandit city with another Greek prisoner, the two prisoners settled in for the night as darkness fell over the marshlands. [music]

Knemon Reveals his Back Story

In the lightless confines of their quarters, the recently captured pair discussed their grim fate. The girl’s name was Charikleia, and the boy’s name was Theagenes. And the young Greek whom the bandits had lodged with them, overhearing their conversation, told them his name was Knemon. When prompted, with some reluctance, Knemon explained how he’d come to be the captive of the bandits.Knemon’s story was an erotic and sensational one. Young Knemon was from Athens. His father had remarried, Knemon explained, and his stepmother began lusting after young Knemon. Knemon refused, and stepmother accused stepson of being the sexual predator, though it was the other way around. Knemon’s father was furious. The intrigue had then deepened. The stepmother’s slave had convinced her stepson Knemon that the stepmother was having a real extramarital affair. When this slave led young Knemon into catch his stepmother in the act, the man making love to her was none other than Knemon’s own father, and so it appeared that he had indeed been trying to murder his own father out of sexual jealousy, a scene which, unfortunately, offered evidence to the stepmother’s malicious accusations against Knemon. Knemon was afterward condemned before an Athenian court.

The young Greeks Charikleia and Theagenes, having little else to do since they were all prisoners of the bandits, wanted to know more – what had happened to Knemon’s stepmother? Knemon told them. While he was leaving Athens – for he had been exiled – young Knemon was delayed for a few weeks at the port. There, from an acquaintance, he learned that his stepmother had met a bad end. The death of the stepmother, told in a tale within a tale within a tale, involved one of her loyal slaves turning on her and revealing her gross misconduct to her husband, after which Knemon’s stepmother killed herself by diving headlong into a sacrificial pit. Knemon’s father, then, had eventually learned of Knemon innocence, but not until after the young man had left Athens. And concluding his story for the present, Knemon told the young lovers Charikleia and Theagenes that his road since leaving Athens hadn’t been easy, either. The young couple wept in sorrow for what Knemon had endured, thinking also of their own misfortunes. These misfortunes were not to abate any time soon.

Because elsewhere in the bandit camp, the bandit chief had a dream about the beautiful Charikleia, and his interpretation of the dream was that he would take his alluring young captive’s virginity. The bandit chief, however, we soon learn, was no mere savage. He summoned his young Greek captives to a meeting, along with all of the other robbers. The bandit leader said he was a person of good stock – the son of the high priest of the city of Memphis, though he’d been usurped by his brother, and as a bandit leader, he’d always been fair with the dispersal of booty. He had always treated their captives well and never mistreated the women they’d captured, but instead ransomed them profitably. But still, the bandit king said, he wanted Charikleia as his wife – she had a priestly bearing to her, too. The bandit king asked for his men’s approval, and they gave it. Then, being an unusually respectful bandit chieftain – he was again the son of a priest – the bandit chief asked for beautiful Charikleia’s consent, as well.

Now, Charikleia and Theagenes didn’t speak Egyptian, and so all of the information being exchanged in the present scene had to be relayed back and forth by the other Greek captive Knemon, who knew both languages. From Knemon’s translation, the bandit leader learned that Charikleia appreciated being asked her consent in the matter, and not being treated like property. She then asked leave to tell her story. And just to be clear, the story that you’re about to hear is not true – we actually aren’t going to learn about who Charikleia and Theagenes really are for a little while still. [music]

Charikleia’s Spurious Biography and a Battle at the Bandit Camp

Beautiful young Charikleia, spinning a tall tale to save her skin, told the bandit assembly that Theagenes was her brother, and that they were from Ephesus, in the eastern Aegean. She was a priestess of Artemis, and her brother, a priest of Apollo. They had been put out to sea in a ship full of sacrificial offerings – one of the regular rituals of Ephesus, but before they could return they’d been swept out to sea and had later wrecked in the western Nile Delta, where their party had been slaughtered. Charikleia told the bandit king that, understanding her position, she would be fine with marrying him – he was the son of a high priest, and likely her best option. Charikleia simply asked if she and her brother could have a chance to renounce their priesthoods, and so it was decided the wedding would be postponed until Charikleia, her new fiancé the bandit king, and her quote unquote brother Theagenes could travel down to Memphis and take care of their religious and marital duties properly.We soon learn, however, that Theagenes was not Charikleia’s brother, but, as certain cues offered to us throughout the novel thus far have indicated, that the pair were actually lovers, though their love was unconsummated. Theagenes wanted to know what lovely Charikleia’s plan was, and Charikleia said that she had bought them time – a couple of days’ time, and that they should keep their true situation secret even from their fellow Greek Knemon, who might seek favor from the bandit leader by betraying the clandestine lovers.

Knemon, though, at that moment, had other concerns. He’d seen a vast party of armed men approaching the bandit camp, and alerted the bandit chief, who told Knemon to hide Charikleia away in the settlement’s secret treasure cave. Knemon did just this, and soon Charikleia was installed in a secret grotto beneath winding tunnels beneath a secret chamber, distraught at her unforeseen separation from her lover Theagenes. The battle soon broke out, with massive forces quickly overrunning the swampy bandit city. The bandit chief, seeing his settlement falling into ruin, could only think of his unconsummated lust for Charikleia, and distraught at the notion that anyone else would ever have sex with her, he hurried to the treasure cave. There, he heard a woman speaking Greek in the darkness, and he stabbed her, thinking that this way, his fiancé would be his if only in death.

The battle aboveground thereafter intensified, the young Greeks Theagenes and Knemon retreating away from the worst of the fighting. The bandit chief, however, threw himself into the worst of the fighting, thinking that he’d lost his fated love, and had no reason to live any more. Rather than being killed in battle, though, the bandit chief, son of a high priest and failed pursuer of lovely Charikleia, was soon himself captured. He was captured, in fact, by forces commissioned by his younger brother, the high priest of Memphis, who was uncomfortable with having the legitimate heir alive and well and leading a large band of brigands in the north. As the bandit chief was led off, the marshland bandit camp soon became engulfed in flames. [music]

Heliodorus’ Aethiopica, Book 2

The Battle’s Aftermath; The Protagonists Split Up

Following the battle, the Greek captives Knemon and Theagenes made their way through the devastated bandit camp, and, with Theagenes frantic with worry about his lover, they went to the entrance of the secret treasure cave. There, it seemed, Theagenes discovered the worst – a woman was dead at the cave’s threshold. Theagenes soliloquized and bemoaned the loss of his love, but he soon realized he’d been mistaken. The dead Greek girl was not, in fact, Charikleia, but instead the Greek slave girl from Athens whom Knemon had once known, who had come to help him. While the poor slave girl was indeed dead, Charikleia was still alive, deep within the bandit caves, and naturally she and Theagenes shared a few minutes of mutual joy that the other had survived the events of the past couple of days. As for the poor dead Greek slave girl, Knemon told them a little more about her – her story was that of a servant who’d aided a mistress in crimes, had tried to atone for her wrongs by betraying her mistress, and in the end been blamed by everyone. She had once been Knemon’s lover, but, not smarting too badly at the news of her death, the young Athenian proclaimed, “Thisbe. . .I am glad you are dead, that you were yourself the messenger who brought us word of your misfortunes” (449).As it turned out, Thisbe had, in a separate chain of events, also come to be a captive in the bandit camp, and been made the chosen bride of the bandit camp’s second-in-command, who’d hidden the Greek slave girl in the cave where the bandit chief had found and accidentally killed her. The bandits’ second-in-command soon learned from the Greeks hidden deeper in the cave that his boss had unintentionally killed his lover, and the second-in-command collapsed on the body of the dead Greek slave girl Thisbe.

The three living Greeks fell asleep, exhausted. Charikleia had a nightmare about losing an eye, and when the other two awoke they tried to interpret it. Soon thereafter, the Greeks decided it was time to get out of the bandit settlement. They formulated a plan – Knemon would go off with the bandit chief’s second-in-command, who was still, inconveniently, present on the scene and weeping over his dead lover Thisbe. As for Charikleia and Theagenes, they would depart for a nearby riverside village along the Nile – one safely beyond of the sphere of the bandits’ influence. Heliodorus first tells us how the young Athenian Knemon fared in the company of the bandit lieutenant and second-in-command.

Knemon’s immediate goal was to ditch his bandit chaperone, and he was able to do so by feigning bad diarrhea after they shared a meal together. The bandit lieutenant, who’d been planning on killing Knemon, was conveniently bitten by a viper, which forestalled his pursuit of the young Athenian. Knemon, not knowing that no one was pursuing him, fled desperately eastward through the upper delta toward the main channel of the Nile. He soon happened upon a man wearing Greek garb. This stranger offered Knemon a place to rest – not his own house, he admitted, but the house of a kindly merchant who’d taken him in. Speaking with the stranger, Knemon soon heard the other man’s story. And within moments, young Knemon was astonished to learn that the old man knew both Charikleia and Theagenes. The old man’s name was Kalasiris, and in addition to the young lovers Charikleia and Theagenes, and the Athenian youth Knemon, Kalasiris, an old Egyptian priest, is one of the most important characters in the novel. [music]

Knemon Meets Kalasiris, who Recalls How He Met Charikleia

So old priest Kalasiris, the young Athenian Knemon learned, knew the lovers Charikleia and Theagenes. Kalasiris didn’t immediately clear up the background of Charikleia and Theagenes. Instead he filled young Knemon in on another mystery. The giant war party that had attacked the bandit camp, old Kalasiris said, had been a Persian war party. They had been dispatched on behalf of the very same rich merchant in whose house old Kalasiris and young Knemon were presently conversing. This merchant led campaigns into bandit territories from time to time, but this particular campaign had been led because the merchant was the lover of Thisbe, the now-dead slave girl who had also been Knemon’s lover back in Athens. Knemon, tactfully, didn’t mention all of this, and because it’s a pretty tangled thicket of the story, let’s move on and hear what the old man Kalasiris had to tell young Knemon about the story’s main characters Charikleia and Theagenes.

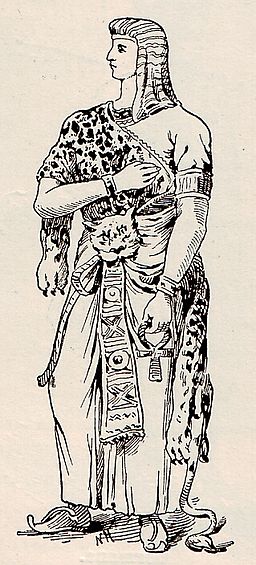

An Egyptian priest of the Third Intermediate Period from a turn-of-the-century German textbook. Heliodorus’ character Kalasiris, who speaks more than any other character in the novel, is the pander figure in Heliodorus’ Aethiopica.

Old Kalasiris said he’d fled – he had fled and gone to the faraway highlands of Delphi in Greece. His reception there was very friendly, and he found the Greeks very curious about all things Egyptian. As an Egyptian Grecophile, old Kalasiris happened to meet a Greek Egyptophile, and this man’s name was Charikles, which, yes, indeed, sounds like the name Charikleia. Charikles told old Kalasiris that he’d lost his wife and child, and then Charikles told old Kalasiris his story, a tale-within-a-tale that will reveal Charikleia’s origins. Wandering widely in his bereavement, Charikles traveled far south along the Nile. And there, Charikles met an ascetic wandering priest from Ethiopia. This wandering priest was in a hurry, and he made Charikles an offer that, though it was highly suspicious sounding, Charikles couldn’t refuse. Offering Charikles a small pouch of exceedingly valuable treasures, he asked Charikles if he would become the guardian of an extremely beautiful seven-year-old girl. The girl had been abandoned as an infant with this pouch of treasures, and it was imperative, the wandering ascetic said, that she got out of Ethiopia. He had been observing Charikles, and he knew that the other man was honorable, and by the way he had to go in a hurry, so it was fine if Charikles became the adopted father of an inexplicably pale skinned Ethiopian girl and accepted an extremely high payment, right?

Well, Charikles, not having a whole lot going on in his life at that particular juncture, accepted the proposition, and soon, very happily, became the father of the girl, who, of course, was the novel’s protagonist Charikleia. The mysterious Ethiopian wandering priest, who was supposed to meet Charikles the next day to tell him more about the little girl, never showed up, thus sealing Charikles’ fate as the adopted father of Charikleia – the two went to Charickles’ hometown of Delphi, where they settled, young Charikleia’s earliest origins remaining a mystery lost to time.

There was just one problem, Charikles had told old Kalasiris in this flashback narrative. Charikleia, upon growing into a woman, went the route of chastity and resolved to never marry. Charikles had asked old Kalasiris to use Egyptian spell craft to convince Charikleia to renounce the chastity thing and consider marrying. Before old Kalasiris could get out his spell book, though, though, a party of magnificent Greeks from Thessaly arrived, intent on partaking in the religious rituals at Delphi. And in the midst of old Kalasiri’s back story about how he knows of the protagonists Charikleia and Theagenes, the novel breaks into Book 3. [music]

Heliodorus’ Aethiopica, Book 3

Kalasiris’ Story Continues: The Old Priest Plays Matchmaker

Book 3 of the Aethiopica opens with the old priest Kalasiris telling the story of how he first met handsome young Theagenes. Theagenes, Kalasiris told the young Athenian Knemon, was the leader of the Thessalians who’d come to Delphi, and Theagenes was so handsome he took everyone’s breath away. In fact, Heliodorus spends no less than two full pages describing just how Theagenes and Charikleia looked upon their first meeting, down to the wind blowing in their hair, the smallest details of their clothing. Sparks flew between the young pair, and Charikleia’s adopted father Charikles exulted in his daughter’s beauty. Beautiful Charikleia was clearly affected by passion for Theagenes, and Charikles and the old priest Kalasiris discussed the young couple with pseudoscientific ancient Greek theories on how passion worked. Charikleia’s passion, as it turned out, was reciprocated, for at a feast that night, handsome young Theagenes could scarcely concentrate on anything, though he was warm and cordial to the old priest Kalasiris once he learned the stranger was an Egyptian priest.That night, old Kalasiris recounted, Apollo and Artemis had come to him in a vision and asked him to take care of Theagenes and Charikleia – to take them, in fact, down to Egypt. Kalasiris was rather surprised. The next morning, young Theagenes came to him, looking troubled. Kalasiris, knowing full well that young Theagenes was infatuated with Charikleia, because it had been obvious the previous day, nonetheless made a show of consulting with the gods before telling Theagenes that the young man’s only ailment was that he was in love. Hearing this, Theagenes was awestruck at the old priest Kalarisis’ capacity to point out the utterly obvious.

At that point, beautiful young Charikleia’s adopted father Charikles summoned old Kalarisis to come and talk with him in the temple at Delphi. When Kalasiris saw Charikles, it was clear that something was wrong. Charikles said that his daughter was not well – she was supposed to arbitrate some festivities that day at Delphi, but was in no condition to do so. Charikles asked Kalasiris to help – couldn’t the old Egyptian use his magic to cure the ailing Charikleia? Leaving Kalasiris with the lovelorn Charikleia, Charikles also repeated his earlier entreaty – couldn’t Kalasiris also make Charikleia renounce her vows of chastity? Kalasiris, looking at the lovesick young woman, said he could probably help out. [music]

Heliodorus’ Aethiopica, Book 4

Kalasiris’ Story Continues: Matchmaking and Uncovering Charikleia’s Past

Book 4 of the Aethiopica continues the lengthy story-within-a-story in which, in the novel’s present day, the young Athenian Knemon has escaped the bandit camp with the heroine and hero Charikleia and Theagenes, wandered over to the Nile, and met an old Egyptian priest named Kalasiris. Kalasiris, who had once been the guardian of the hero and heroine, has now been speaking for upwards of forty pages about how he first met them, and he continues his narrative at the outset of Book 4.

The amphitheater at Delphi, where Heliodorus’ character Theagenes was victorious at the Delphian games. Looks like the dog in the foreground is ready for some racing, too!

It was the morning of the Delphian Games. In spite of her illness that morning, Charikleia had been able to roll out of bed – likely stirred by the prospect of seeing handsome Theagenes, because she was to award the wreathes of victory to the participants of a footrace. Theagenes indeed was there, and though he hadn’t been planning on running, when he saw that Charikleia was to award the victory prizes, he decided to strap on his running sandals, even though he was warned that what he was doing was highly unconventional. Predictably, handsome young Theagenes’ performance in the race was spectacular, and in the end he outstripped his closest rival by several yards, falling into the arms of Charikleia and kissing her hand.While the victory was spectacular, and certainly seemed to intimate the coming together of the two lovers, custom nonetheless kept them apart, and that evening Charikleia’s impassioned ardor worsened. Kalasiris consoled her, however, and that same evening he spoke to Theagenes, as well, telling Theagenes that he’d help the young man overcome all the hurdles in the way of marrying Charikleia. The biggest hurdle was actually a pretty problematic one. Charikleia’s adopted father Charikles wanted her to fall in love, and to be married – for all this he had enlisted the help of old Kalasiris. But Charikles wanted her to be married to someone else – her cousin, in fact – and he’d had this idea in his mind for a long time.

Visiting Charikles, Kalasiris learned that the hopeful father had brought Charikleia’s cousin to her. The young lady suddenly seemed dewy eyed and susceptible to romance for the past 36 hours – perhaps now was the time. When Charikleia saw her cousin, however, she screamed in disgust and tried to strangle herself. This might have been the part of the story at which old Kalasiris just told Charikles that his daughter wasn’t interested in her cousin – screams of disgust aren’t often signs of love interest, after all. But instead, Kalasiris took a different route. He said he knew that Charikles had received some tokens upon adopting Charikleia years earlier – generally these ancient foundling stories involve the mysterious baby coming with some odds and ends that later prove their identity. This was the case with Charikleia – she had been given up for adoption with a thickly embroidered band, which her adopted father gave to the old priest Kalasiris to study.

The band, as it turned out, was embroidered thickly with writing in the sacred Ethiopian language, known to the priestly caste, and Kalasiris could read it. The embroidered script, which Heliodorus quotes in full in the novel, forms about a page and a half of text, and in it, we finally learn who Charikleia actually was. Charikleia, we finally learn, was the daughter of an Ethiopian queen, and a descendant of the famous Ethiopian princess Andromeda. Charikleia’s mother had been unable to conceive for the first decade of her marriage, but then, one day, she was making love to her husband and finally conceived. The problem was, the queen was staring at a portrait of the heroine Andromeda while they had sex, and Andromeda, though an Ethiopian princess, had allegedly had very pale skin, and so the baby that the queen had become pregnant with had also had pale skin. There are two weird things about that sentence. The less weird thing is that the legendary Andromeda had very pale skin even though she was from an East African family – but – you know, it’s a myth so, fine. The weirder thing about the story of Charikleia is that it relies on an ancient medical theory called “maternal impression.” In this ancient theory, things that the mother is looking at during the moment of conception have a formative effect on the baby’s development within the womb. So, if you conceive while looking at some curtains, or a lava lamp, or Budweiser on the nightstand, you might run into a bit of trouble nine months later in the delivery room. Anyway, that was why Charikleia ended up having pale skin – because her mother had looked at a painting of the pale-skinned Andromeda at the moment of conception.

When little baby Charikleia was born, her mother the queen was naturally very apprehensive. The baby did not look like its mother or its father, and Charikleia’s skin, the queen predicted, might be the cause of her demise. That was why the queen had hidden Charikleia away and then set her out with a few tokens indicating her birth. These tokens, the old Egyptian priest learned, while reading the aforementioned embroidered letter, also included a ring that had once belonged to the Ethiopian King.

With Charikleia’s mysterious background finally cleared up, Kalasiris went back to talk to Charikleia. Cutting to the chase, he told Charikleia that it was perfectly obvious she was in love with Theagenes and ought to marry him. Charikleia blushed and broke into a sweat – her secret was out with one person, at least. And since secrets were coming out, Kalasiris told Charikleia everything he had learned about her from the letter. There was even more than this. Old Kalasiris actually knew the Ethiopian Queen, and indeed had heard the story of Charikleia’s birth before – from the Queen herself, in confidence.13 Kalasiris said that his directive now was to get Charikleia happily married to Theagenes, and get them back to Charikleia’s mother in Ethiopia.

Evidently a man fond of keeping secrets, old Kalasiris said they needed to keep everything they’d learned to themselves. And further, Kalasiris told Charikleia that she needed to pretend to consent to a marriage with her cousin. Charikleia said she would rather not do this, but Kalarisis offered her the following extremely sketchy assurance. He said, “Events will reveal all. When a plan is disclosed to a woman in advance, it can sometimes cause her alarm, and often an enterprise is executed more boldly if it is carried through without forethought. Just do as I say” (510). If those words don’t inspire confidence, I don’t know what does.

Anyway, old Kalasiris went to Charikles, and in a roundabout fashion convinced Charikleia’s adopted father to bedeck his daughter with all of the jewelry that had been left with her when she was an infant – this would make her more seductive to her cousin, Kalasiris said. And Kalasiris went to handsome young Theagenes, and told Theagenes to hold tight and wait for a sign from him, even though the other Thessalians were leaving. Kalasiris met some friendly Phoenicians that evening and secured a southbound vessel to take him and the young couple away from Delphi.

Late that night, Kalasiris’ plan sprang to life in full. A band of Theagenes’ countrymen broke into Charikleia’s quarters at night, and she was abducted. Charikleia evidently had been informed that they were coming, and while the Thessalians headed north through the mountains, Charikleia and Theagenes went to where Kalasiris was staying, throwing themselves completely into the mercy of the old Egyptian priest’s care. To give you an idea of the rather melodramatic style of Heliodorus’ novel, at the moment Theagenes reunited with old Kalasiris, Theagenes gasped, “Save us! Now our persons are mortgaged to fortune, bound by the chains of a chaste love, cast into an exile self-imposed but innocent. On you depends our only hope of deliverance” (514). Kalasiris, understanding in full the vulnerability of the young couple and the chance they’d taken on him, didn’t take the young man’s words lightly.

The old priest Kalasiris prepared to go off and execute more of his plans, but Charikleia stopped him. He shouldn’t leave her alone with Theagenes, she said. Such a thing would be bad for her reputation! The guy was a hunk, certainly, and she was smitten with him, but also, she didn’t really know him that well, and so could Kalasiris make Theagenes swear to behave honorably? Kalasiris said he could, and the swearing took place.

Then Kalasiris hustled off to talk to Charikles, father of the now presumably abducted Charikleia. Inexplicably, old Kalasiris stirred Charikles and the Delphians into a rage – Thessalians had invaded their temple quarters and stolen from them – were they going to take that sitting down, or fight back? The bereaved Charikles gave a prolonged and self-pitying speech, and soon the Delphians were stirred into a martial frenzy, and there was talk of banning all Thessalians from Delphian games, and even of impalements. [music]

Heliodorus’ Aethiopica, Book 5

The Narrative Returns to Present Day: Charikleia Arrives at Nausikles’ House

Leaving the territory of central Greece to unnecessarily fall into a regional war that he himself had needlessly caused, the old priest Kalasiris jostled the hero and heroine onto the ship he had secured the previous day, and the lovers and their pander were off, bound through the Gulf of Corinth. At this point, though, Kalasiris broke off his story to young Knemon – he has now been speaking for 55 pages. Kalasiris broke off his story because the owner of the house where they were staying had returned home, and he offered them news that was very surprising to Knemon. The Athenian slave girl Thisbe, who had been Knemon’s lover up in Greece, and then betrayed him but then sort of redeemed herself before coming to Egypt to find him, was actually alive!Heliodorus himself fills us in on the plight of the not-actually-dead slave girl Thisbe. If you’ll remember, before Kalasiris’ giant story about how he’d met Charikleia and Theagenes, in the main plot of the novel, the hero and heroine had gone their separate ways while Knemon snuck off with one of the robber lieutenants. Heliodorus tells us that Charikleia and Theagenes had taken a little make out break in the underground treasure burrow – but is very clear to assure us that all they did was make out. After their restrained subterranean hookup, the hero and heroine established various clandestine ways they might communicate and find one another in the event that they were captured and or separated, and then they set out.

Emerging from their hidden cave, Charikleia and Theagenes suddenly saw armed men in the near distance. In a scene that may or may not be intentionally funny, the two debated about what to do in abstract philosophical terms, Theagenes saying they should throw themselves into the warriors’ hands, Charikleia that they should sneak back into the cave. The debate went on way too long and they were spotted. Persian soldiers suddenly surrounded them. These were the same Persian soldiers who had been hired by the merchant Nausikles, the guy who had the house over by the Nile where Kalasiris was telling young Knemon his life story. Nausikles, in the party of the Persian soldiers, saw Charikleia and convinced her (in whispers) to pretend that she was his lover Thisbe, and she did so. This saved Charikleia from the Persian war band, but Theagenes was led away as their captor.

Charikleia was then taken by the merchant Nausikles back to his house, where young Knemon and old Kalasiris were both overjoyed to recognize her. Nausikles, being an opportunistic merchant, asked if he could have some payment for his recently acquired supermodel captive, and so old Kalasiris gave the merchant one of the lavish rings that Charikleia had been abandoned with as a baby. That evening they had a feast, and at the feast, Kalasiris, when prompted, continued his earlier narrative about how he had first met the two young lovers Charikleia and Theagenes. [music]

Kalasiris Concludes His Story: How the Lovers Came to Egypt

Kalasiris, Charikleia, and Theagenes had embarked with the Phoenicians, Kalasiris said, and after some tricky coastal navigation, had to stop on an island off the northwest Peloponnese for the winter. Kalasiris and the young lovers found lodgings at the home of an old fisherman. Among the Phoenician sailors who had brought them there, the captain developed a passion for Charikleia and sought to marry her, and then, more pressingly, a band of savage pirates from the Ionian Sea, the leader of whom had also developed a passion for Charikleia, were planning on attacking the Phoenician merchant ship that had carried the protagonists on their journey thus far. Fortunately, the hero, heroine, and their guardian were able to escape with the Phoenician merchants, and went far to the southeast, to the island of Crete, though their ship was damaged in a storm on the way there.The ship was repaired, and they headed south down to Libya, as had been their intention, but they were dismayed to discover that the Ionian Sea pirates from earlier were now tailing them. These pirates boarded the Phoenician ship, and their leader told Charikleia he wished to marry her. Charikleia, turning the situation to her advantage, said that would be fine, but could he save her quote unquote brother Theagenes and her quote unquote father Kalasiris? The pirate leader said he would, and the Ionian pirates took charge of the Phoenician merchant ship. However, the pirates didn’t really know how to pilot such a large vessel, and a big storm blew in, and they ended up drifting southeastward to Egypt.

When they beached there, the Ionian pirates were still in control of the Phoenician vessel. Charikleia was now to be married to the pirate leader in a weird boatside ceremony as the pirate crew helped themselves to all the goodies they’d pillaged from the merchant ship. But Kalasiris conceived a new plan – a deliciously diabolical one. Kalasiris told the Ionian pirates’ second-in-command that Charikleia loved him, and not the pirate chief. As the day lengthened and the wine flowed, the second-in-command confronted the pirate captain, and soon the factions that supported each of these men attacked one another ferociously. Charikleia found a bow and, standing on the deck of the ship, shot arrow after arrow at pirates, regardless of whose side they’d taken. Theagenes was able to defend himself, and the young couple rejoined one another among the freshly killed pirates. As for old Kalasiris, he had been hiding, and he was separated from the hero and heroine because he saw the Egyptian bandits coming down the shoreline, those same bandits whose arrival at the shipwreck is the first scene in the Aethiopica. This, then, finally, at the halfway point of the novel, fills us entirely in on all the events that had happened to lead up to the scene with which Heliodorus opens his book. [music]

Heliodorus’ Aethiopica, Book 6

Kalasiris and Charikleia Plot to Recover Theagenes

The next day, after Kalasiris told his 70-page story, Knemon, Kalasiris, and the merchant Nausikles embarked on a short journey to meet with the Persians who now had handsome young Theagenes as their captive. They quickly learned, however, and much to their chagrin, that heroic Theagenes was no longer the captive of the Persians, but had become the prisoner of another group. The rescue party planned what to do next, and headed back upriver. When the trio returned to Nausikles’ house, Charikleia was crestfallen to see that Theagenes wasn’t with them.At this point in the story, Kalasiris and Charikleia planned to head back over to where they believed Theagenes was to try and recover him. As for young Knemon, the Athenian, in the 36 hours or so that he’d been staying at the merchant Nausikles’ house, had evidently made quite a good impression, because Nausikles betrothed Knemon to his daughter. Knemon was onboard with it, and soon, wedding festivities began taking place.

As preparations for the wedding began, Charikleia languished and pitied herself, desperately missing Theagenes. Old Kalasiris found her crying, and reproached her for being so pessimistic. The two then discussed the plan to recover Theagenes. As we learned earlier in the wicker basket of this novel’s plot, in which everyone is somehow related to everyone else in a labyrinth of past events, old Kalasiris was the father of former swamp bandit leader Thyamis. For this reason, Kalasiris said, they likely had a pretty good chance of getting handsome Theagenes back, as they had been told that Thyamis was in charge of the group that had control of Theagenes. Charikleia was skeptical, relating how Thyamis, like seemingly everyone else, had tried to marry her in her brief time as his captive. They planned and plotted, and Charikleia and Kalasiris decided to dress up as beggars.

Kalasiris and Charikleia then said goodbye to all those at Nausikles’ house, and made their way toward where they believed they’d find Theagenes, disguised as moneyless wanderers. They discovered the scene of a terrible battle at one village, and learned that a Persian military band had been ambushed by an unexpectedly burly population of villagers. An old woman whose son had been killed told them about the violence between Egyptians and the Persian colonists that had unfolded, and Kalasiris and Charikleia settled in for the night. Charikleia, who couldn’t sleep, saw a disturbing scene – the old woman who’d given them information on what had happened, in a diabolical midnight ritual, brought her son back to life and began asking him about her other son. You know how awkward that can be – when you’re trying to get some sleep in a corpse-littered village and then people start resurrecting their children. Things soon grew more awkward still. The resurrected corpse chastised his mother for reanimating him, and warned her that at that moment, her necromancy was being spied on, alluding to Charikleia’s presence nearby before dropping dead once more. The old sorceress, then, irritated at having her black arts discovered, began prowling around looking for whoever had observed her, but she ended up falling and impaling herself on her own sword. I’m telling you, these ancient Greek novels are 10/10, solid gold. [music]

Heliodorus’ Aethiopica, Book 7

The Heroes Arrive in Memphis; Arsake Appears Onstage

Book 7 opens with Kalasiris and Charikleia heading to the old priest Kalasiris’ hometown – the city of Memphis, about a dozen miles south of the center of modern day Cairo. Memphis was where one of the high priest Kalasiris’ sons had usurped the other son. And at just that moment, Kalasiris’ older son Thyamis, former leader of the swamp bandits, was leading a war party to besiege Memphis, and with him was handsome Theagenes, whom he had captured during the battle at the village a little ways to the north, where Kalasiris and Charikleia had spent the previous night.

The archaeological museum at Memphis, Egypt, showing some artifacts from the ancient city, where Charikleia and Theagenes run into bad luck in Heliodorus’ novel.

The forces squared off to face one another, and fortunately, without any major fighting breaking out, Thyamis confronted his younger brother who had wronged him. The two brothers were about to fight, but their father Kalasiris appeared and, throwing off his beggar’s disguise, told them not to quarrel any more. Theagenes, who had been arrayed for whatever combat lay ahead, was surprised when an extremely filthy vagrant woman jumped on him in a smelly embrace, but a moment later he realized it was Charikleia. It was all a pretty joyous end to a day that had not long before appeared ominous indeed. The inhabitants of Memphis poured out to welcome the estranged high priest Kalasiris and his legitimate son Thyamis back, just as other citizens of Memphis thronged around the young supermodel couple Theagenes and Charikleia, the latter of whom had evidently undergone a wardrobe readjustment at some point.

Everyone in the city seemed quite content indeed, though in a sad scene, old Kalasiris passed away, happily reunited with both of his sons at last. Everyone was content at how things had unfolded – everyone, that is, except for the Persian satrap’s wife and exotic seductress Arsake, who, having watched Theagenes all day, had decided she wanted to have sex with him. Arsake, that afternoon or evening, lay in her bedchamber, writhing around with passion and then consulting with one of her servants about how to get into Theagenes’ pants. This servant, who had helped Arsake with her adulterous affairs before, comforted the lovelorn noblewoman, telling her that indeed Theagenes’ current lover Charikleia was no match for the beauty of Arsake.

Arsake’s handmaiden went and invited Charikleia and Theagenes to the Persian palace, where the handmaiden interviewed them. Having been kidnapped at least four hundred times together, Charikleia and Theagenes knew enough to be a little bit wary of strangers, and so they told the Persian handmaiden their usual tall tale about being brother and sister. Shortly afterward, Charikleia and Theagenes were locked into a room in the Persian palace. The Persian handmaiden’s son, unfortunately, saw them there, and he developed a passion for Charikleia, at the same time, realizing he’d seen Theagenes before. If you’ll remember, among Theagenes’ bouncing around between different captors, he had briefly been the prisoner of some Persians, and the Persian handmaiden’s son, whose name was Achaimenes, recognized Theagenes. To pause for just a moment, remember that this novel is set in the ancient past – the 500s BCE, when Achaemenid Persia ruled over Egypt, and so that’s why we have Persian folks in the city of Memphis, Egypt, ruling over everyone and telling them what to do.

Anyway, with a new set of people wanting to have sex with them, Charikleia and Theagenes were brought into an audience with the Persian satrap’s wife. It was custom for Greeks to prostrate themselves beneath their Persian colonial overlords, which was what the satrap’s wife Arsake and her court clearly expected, but Theagenes did not even bow. Over the next few days Arsake slowly tried to seduce Theagenes through extensive use of the handmaiden who served as pander between them. The handmaiden, however, pretty quickly intuited that Theagenes wasn’t interested. The handmaiden had a private audience with Theagenes and Charikleia and told Theagenes that Arsake was a powerful woman and wanted to have sex with him – there was really no way around it, and when compelled, Charikelia, grinding her teeth (remember she was masquerading as Theagenes’ sister) agreed that her quote unquote brother really ought to just give the highborn Persian lady what she desired.

Theagenes still held out, however, and soon the old handmaiden was in despair. She told her son Achaimenes that she was at her wit’s end, and Achaimenes proposed an arrangement – he could guarantee the lustful satrap’s wife Arsake sex with Theagenes, provided he was promised marriage with Charikleia. Soon the plan was set into motion. The old handmaiden’s son Achaimenes knew that Theagenes had been a Persian prisoner, but had escaped. He told the lustful Arsake this. And Arsake, realizing Theagenes was her property, dropped all pretenses of treating him with deference. He would be a servant, and needless to say, he would minister to her sexual needs.

The hero and heroine, learning of all of this, were naturally distraught. In desperation, Theagenes professed to the satrap’s wife Arsake that Charikleia was his wife, and thus her planned marriage with the handmaiden’s son was null. Arsake agreed that this was the case, although this slight improvement still didn’t liberate the young lovers from their captivity. Still, Theagenes had a plan. The hero and heroine in the novel, while repeatedly depicted as alabaster and innocent, sometimes show a surprising capacity to connive and manipulate others, and such was the case with Theagenes’ plan in the Persian court in Memphis. Theagenes knew that the handmaiden’s son Achaimenes would be furious that his marriage plans had been steamrolled. And, openly working himself into Arsake’s good graces in front of the outraged Achaimenes, Theagenes didn’t have to work too hard to set the mistress and her subordinate against one another. Soon, the old handmaiden’s son Achaimenes decided he would retaliate. The sexually thwarted Achaimenes went to the south, where Arsake’s husband, the mighty Persian satrap Oroondates, was engaged in a military campaign against Ethiopia. [music]

Heliodorus’ Aethiopica, Book 8

The Hero and Heroine Held Captive by Arsake

There was, at this juncture, a war going on between Persian-controlled Egypt to the north, and independent Ethiopia to the south. The handmaiden’s son Achaimenes hurried down to speak to the Persian satrap of Egypt, and he told this satrap that the satrap’s palace was a mess. In the imperial capital of Memphis, after all, the high priesthood had been swapped, with a new leader coming in, possibly not under the sway of Persian control, and, to boot, the satrap’s wife Araske was at that moment engaged in a serious flirtation with a sexy Greek man whom she was currently holding prisoner. The satrap, not pleased by any of this news, dispatched a letter demanding that our heroes Charikleia and Theagenes be brought to him presently.

A central walkway in Persepolis. The Achaemenid Persian presence in Egypt looms large in several of the later books of Heliodorus’ Aethiopica, Egypt’s powerlessness beneath the Persians is analagous to Theagenes and Charikleia’s powerlessness as they continue to be bandied about by various captors.

Arsake, the satrap’s wife, soon found herself in a bind. The new high priest of Memphis, the bandit chief Thyamis, who’d regained the throne his brother had usurped, was now pressuring Arsake to release Charikleia and Theagenes to him. Arsake was also upset that her handmaiden’s son had disappeared, presumably to tattle on her to her husband. Arsake’s handmaiden, however, did not recommend penitence. She said Arsake needed to be more aggressive with Theagenes if Arsake wanted to have sex with the hunky young Greek hero. The handmaiden recommended whipping and torture, and soon, Theagenes was starved and otherwise made miserable, though naturally, his loyalty to Charikleia was undaunted.Theagenes’ continued resistance only stirred Arsake and her pander into greater depths of depravity. They decided that they would kill Charikleia. They needed an excuse. The handmaiden planned to poison Charikleia during a dinner with her, but a sympathetic Greek slave switched their cups, and so the scheming handmaiden suffered the awful death she’d planned for Charikleia. Charikleia, at this point convinced that she would never see Theagenes again, decided to do everything she could to bring her life to an end. She confessed to the poisoning, and soon thereafter was sentenced to be burned at the stake.

Charikleia was thereafter led out beyond the city walls, where a pyre had been prepared. Before her execution, Charikleia called out to all those present, avowing her innocence and the adulterous guilt of the satrap’s wife Arsake. And then, in the J.R. Morgan translation “Charikleia climbed onto the pyre and positioned herself at the very heart of the fire. There she stood for some time without taking any hurt. The flames flowed around her rather than licking against her; they caused her no harm but drew back wherever she moved towards them, serving merely to encircle her in splendor and present a vision of her standing in radiant beauty in a frame of light, like a bride in a chamber of flame” (614). Following this miraculous spectacle – a spectacle we see in Christian martyr tales from the same period – the populace of the city of Memphis gathered to watch the execution cried out in rage – clearly Charikleia was favored by the gods! – but Charikleia, once she came down from the pyre, was seized by the Persian guard and led back to prison.14

That evening, Charikleia and Theagenes were imprisoned together, and they discussed their sad fate, though they still felt heartened by Charikleia’s survival and by some past oracles that they heard and remembered. They predicted that Charikleia had survived the flames due to a magic ring that she’d been wearing – one she’d been abandoned with as an infant.

As the night lengthened, more unexpected events unfolded. The Persian satrap, though engaged in a campaign against Ethiopia to the south, had ordered an intervention on the ugly intrigues unfolding in the palace at Memphis. The satrap’s men arrived at Memphis and snuck Charikleia and Theagenes away in the darkness. Thinking that they’d soon be executed, the young couple braced themselves, but were soon surprised when instead they were simply carried farther and farther away – south along the Nile away from Memphis and toward the city of Thebes. They sheltered with their Persian escort in a verdant area during the hot afternoon the next day. A messenger arrived at the improvised day camp and informed their Persian escort that Arsake had killed herself – good news in some ways for the hero and heroine, notwithstanding the fact that Charikleia and Theagenes had no idea of where they were being taken.

Their escort was attempting to lead them to the Persian satrap, as he’d been ordered. However, the territory around Thebes and south of it had degenerated into a general war zone, with Persians and Ethiopians coming into conflict with one another. What was worse was that a third party had become involved – a group called the Troglodytai. These were a mythical population of cave dwellers who lived on the southern Egyptian coast – they could run supernaturally fast and were adept at navigating the wilderness of southern Egypt. The Persians were able to fend off the Troglodytai, but when they engaged with a larger group of Ethiopians, the little Persian escort band was not so lucky. Soon, after a multilingual exchange in which Theagenes managed to communicate with the Ethiopian leaders, it was decided that the hero, heroine, and the Persian eunuch who’d been escorting them southward would all be taken to the Ethiopian king. Charikleia and Theagenes, having changed hands many times over the course of the novel, were now under the control of the Ethiopians. [music]

Heliodorus’ Aethiopica, Book 9

The Battle for Syene and its Aftermath

The scene shifts at this point in the novel to the ancient city of Syene, or modern day Aswan, a city three quarters of the way down the Egyptian Nile. The Ethiopian army had besieged the city of Syene, and the Ethiopian king, seeing the Egyptian prisoners and Persian escort brought to him, felt that it was a good omen to his war effort. And just to be clear, Charikleia is the Ethiopian king’s daughter, though he doesn’t know it yet. In fact, the Ethiopian king was so far from knowing that the young Greek woman was his daughter, that he planned to offer Charikleia and Theagenes as blood sacrifices to appease the Ethiopian gods.

Aswan, Egypt, the site of Syene. The sack of Syene by means of flooding the walls may have been inspired by accounts of the siege of Nisibis (350 CE) recorded by Heliodorus’ fellow Syrian Ephraem, though the tale of flooded city walls may have been a standard fixture of pseudo-historical military narratives.

The besieged Persians and their Egyptian subjects had no choice but to surrender to the Ethiopians, and the Ethiopian army caused the rising ring lake to lower by cutting an outlet for all the water they’d let in. The Persian satrap and his military forces escaped under the cover of night. This put the poor Egyptian subjects into a pickle – they didn’t want their Ethiopian adversaries to think they’d abetted the Persian escape. The Ethiopian King, seeing that the Egyptians were helpless, chose not to vent his wrath on mothers carrying babies and moreover the average Joes and Janes of southern Egypt. The Ethiopian King’s business, after all, was with the colonial overlords – the Persians.

The Persian satrap had fled and reorganized with a sizable body of Persian troops nearby. The Persian imperials had a substantial and very heavily armored cavalry. The armies squared off against one another, with the Persians being outnumbered and putting their backs to the river so they couldn’t be encircled, and the Ethiopians marshalling elephants armed with giant slings toward the Persian cavalry. Heliodorus describes the battle in vivid detail, and at its culmination the Persians were defeated, their satrap leaping onto a horse and speeding off to escape.

Soon, though, the Persian satrap was captured, and brought to the Ethiopian king. The Ethiopian king treated the satrap courteously, and the satrap essentially said he had been following orders of the Persian king of kings – orders which any Persian official couldn’t ignore if he wanted to live. The Ethiopian king sent the Persian satrap to be cared for, and then went into the conquered city of Syene, where the townspeople greeted the Ethiopian king warmly.

With the Ethiopians settling into Syene and its environs, it was time for Charikleia and Theagenes to be brought to the Ethiopian king – remember they’d been captured by Ethiopians before the siege battle had broken out. Prior to being presented to the Ethiopian king, Theagenes and Charikleia had a conversation. It was Theagenes’ opinion that they ought to just tell the Ethiopian king the truth and show him Charikleia’s birth tokens straight away. Charikleia said they should wait until her mother the queen was around – her mother would be able to back up the unusual story of her birth and upbringing abroad. Theagenes said that this would be fine.

With some heavy-handed foreshadowing on Heliodorus’ part, when the Ethiopian king first saw Charikleia and Theagenes, he remarked he had dreamed of having a daughter just like Charikleia, and come to think of it, he’d love to have a son like Theagenes. The Ethiopian king then announced the terms of his military victory. The cataract of the Nile that was at Syene, he said, had always divided Egypt from Ethiopia. The Persian imperialists had overstepped this traditional boundary, and, the Ethiopian king said, it was now restored. The Ethiopian King asked that news of the restoration would be brought to the Persian king of kings, and said that Syene and another city that had been impacted by the war would receive ten years with no tribute penalty imposed, in order to help them recover, and that he expected the Persians currently ruling Egypt to do the same thing. The Persian satrap, wounded but grateful at having been spared, enthusiastically said that Syene and the lands around the first cataract would be left alone and he would see to it that Persians honored the armistice terms of the generous Ethiopian king. [music]

Heliodorus’ Aethiopica, Book 10

Charikleia and Theagenes on Trial

The Ethiopian king headed southward, to the capital of Meroe, dispatching letters to his wife on the way. Meroe, by the way, was in the east central part of modern day Sudan on the east bank of the Nile. The Ethiopian queen heard word of her husband’s imminent arrival back home. Though at the end of Book 9 we were left with the sense that the mild-mannered Ethiopian king might treat Charikleia and Theagenes well, we learn pretty quickly in Book 10 that this will not be the case – the heroine and hero, as it turns out, are to be killed as a sacrificial offering.When the Ethiopian king arrived back in his capital, his wife and people greeted him enthusiastically, some of the public present clamoring for the blood sacrifice that everyone knew was going to take place. The Ethiopians, according to Heliodorus’ narrative, would sacrifice two virginal young people to their sun and moon gods when military victories transpired in order to show their gratitude. Charikleia and Theagenes were brought out, and the Ethiopian king and queen looked over the pair, the queen feeling especially reluctant to kill Charikleia. Wasn’t there some way out? the queen asked. The king said that if it were made known that Charikleia wasn’t a virgin, then she wouldn’t have to be sacrificed, although this would of course dishonor her reputation. The queen said she’d rather have Charikleia declared unchaste and saved than killed for being a virgin, but before any plan could be executed, the next part of the ceremony unfolded.

A magical grid – some sort of golden floor that people could walk on – was brought out. The magic of the grid was that it burned you if you weren’t a virgin. A few of the other victims destined for sacrifice walked on the magic grid, some virgins, and some not. The crowd was surprised when handsome Theagenes, walking over the grid, was proved to be a virgin. Then Charikleia, dramatically taking her hair down, strode onto the platform, looking ravishing and, as Theagenes had, demonstrating her chastity.

At this point, a group of ascetic priests associated with the king’s court said they had seen enough – they weren’t into the whole human sacrifice thing. They went on their way, though they begrudgingly admitted that the Ethiopian king should do what his people demanded. But Charikleia interrupted their exit. One of departing Ethiopian priests had been the very same man who’d given her to her adopted Greek father Charikles for safekeeping when she was a child. One by one, Charikleia produced the baubles that she’d been left with as a little girl, until the priest was wholly convinced as to her identity. The priest then explained the extraordinary circumstances of Charikleia’s conception, including the portrait of pale-skinned Andromeda and her mother. If you’ll remember from earlier, Charikleia was white because her mom had looked at a painting of Andromeda at the moment the queen became pregnant. These details, for whatever reason, were thought fit discussion for a public trial, and so the portrait of Andromeda was brought out, and sure enough, her skin was the same hue as Charikleia’s, which corroborated the odd story about why Charikleia was so pale skinned. This further proof, together with a birthmark on Charikleia’s arm, finally won everyone over, and the Ethiopian king hurried forward to embrace Charikleia and cry, his wife doing the same, reunited at last with their long-lost daughter.

However, the Ethiopian king said, he was still going to kill her. It was the law, after all, and his people’s compassionate understanding of the princess’ arrival home only made the Ethiopian king love them more and want to do what was best for the public welfare – and this, in his mind, was honoring the gods’ benefactions by means of the previously planned blood sacrifice. As it turned out, though, the Ethiopian king’s speech was a piece of public theater – one which he knew his people would have none of. The citizenry of Meroe wasn’t about to let a princess, seemingly returned to them by a miracle, be sacrificed on their behalf. The issue of Charikleia’s sacrifice was thus closed, but there was still one other thing to be decided.

Theagenes in Peril

Who, the king asked his daughter, was Theagenes? He couldn’t be her brother, because the queen hadn’t given birth to twins. At this question, Charikleia blushed, and it was decided that Theagenes himself would explain who he was. But there was a hiccup before this could happen. The Ethiopian king still intended for Theagenes to be burned alive, along with all of the other captives. This, Charikleia made clear, wasn’t going to work. She would die if Theagenes died. Or no – she said – she would be the one to kill him. After some back and forth, the Ethiopian king said that he thought Charikleia’s wits had become discombobulated – she should, he said, go and take five minutes to collect herself.With the queen and newly unearthed princess away for the moment, the Ethiopian king summoned emissaries who had come to visit him. One of them was his nephew, a tall and handsome young man whom the Ethiopian king had more or less accepted as a son. The relationship between the king and his nephew made Theagenes’ position all the more perilous – for the Ethiopian king joyously announced that with the recovery of his long lost daughter, his nephew would now be able to marry his cousin, the-weirdly-pale-skinned, possibly-mentally-unsound, and until-only-four-minutes-ago-thought-deceased Charikleia. The king’s nephew blushed. He gave the Ethiopian king a gift – a giant man and formidable fighter, who knelt before the king, with a clear sense of superciliousness due to his immense size. The king, with some sense of humor, gave his new super-sized warrior an elephant as a present.

As a sequence of emissaries then visited the king, the Ethiopian king received gifts, and gave gifts back in return. One of these emissaries brought the Ethiopian king a giraffe, an animal which no one in the court had ever seen before. The giraffe caused such a stir that some sacrificial bulls shook loose from their confines and began running around – one of them got away. This escape caused heroic young Theagenes to spring into action. The hero, who’d meekly been awaiting his execution, jumped onto the back of a nearby horse, and rode in pursuit of the fleeing bull. In a dramatic chase all around the assembled Ethiopians at the capital, Theagenes was able to jump onto the bull, and then, by holding onto its horns and kicking at its legs, cause it to fall over and knock itself out.

Theagenes was brought to the Ethiopian king, but the assembled populace, whose appetite had been whetted by unexpected spectacles, said that they now wanted to watch the fearless young Theagenes fight the giant Ethiopian warrior the king’s nephew had brought to the court. The king said that this would be acceptable – they would wrestle – that way Theagenes would still be suited for a sacrifice. Theagenes squared off against his much larger opponent. What nobody knew was that Theagenes, conveniently, was a crack shot wrestler. After pretending to take a couple of blows from his opponent harder than he’d really felt them, Theagenes systematically destroyed his opponent, until the Ethiopian giant was facedown and pinned in the dirt.

Charikles Arrives; The Novel’s Denouement

In spite of Theagenes’ multiple unexpected victories, though, the Ethiopian king still planned to sacrifice him and marry Charikleia off to her cousin. The young couple was being exceedingly reluctant to reveal the romance between them, though finally, off camera, Charikleia told her mother the queen about her romance with Theagenes. And, piling the plot twists thick in his novel’s final scene, Heliodorus adds one more unexpected occurrence. An old Greek man arrived in the Ethiopian capital of Meroe – we learn that he’s there to look for his daughter. When this old Greek man’s identity was revealed, he proved to be Charikles, the man who had taken care of Charikleia between the ages of 7 and 17 and had given her his name. Charikles, seeing Theagenes, was incensed. Charikles attacked Theagenes, dragging him away from the altar area, and saying that Theagenes had abducted his daughter (and by the way, for all we know, this is what Charikles thinks). Soon, however, Charikleia saw her Greek adopted father there, and rushed down to embrace him, and the Ethiopian king and queen realized that Charikles was the man they to whom they were indebted for raising their estranged daughter.And at last, the protracted finale of the Ethiopia begins to draw to a close. The queen, who’d learned Charikleia’s secret, told the king that their daughter was betrothed to the handsome young man who’d wrestled a bull and clobbered a giant. The Ethiopian priest present said that from everything he’d seen, it was pretty clear that the gods weren’t interested in any human sacrifices that day. The Ethiopian priest then began tidying things up properly. Enough with the human sacrifices, the priest said – they shouldn’t do that anymore, period. He said Charikleia and Theagenes ought to be given the public’s blessing for marriage and everything that it entailed, and those present roared in approval. And he said there would now be an animal sacrifice to honor their union. The Ethiopian King and Queen removed their priestly headdresses, and gave these to Charikleia and Theagenes. The young couple then made the sacrifice, and rode together into the city in a chariot. Theagenes sat next to the king, the priest sat next to Charicles, and Charikleia sat next to her mother, and Heliodorus tells us that a wedding of suitable magnificence followed very soon thereafter. And that’s the end. [music]

Young People Adrift: A 2,500 Year Old Narrative Staple