Episode 91: The Passion of Perpetua and Felicity

In Carthage, in 203 CE, a Roman noblewoman and her retinue were butchered in an amphitheater. Learn her story, and the earliest history of Christian martyrs.

| Read Transcription | References and Notes |

| Episode Quiz | Episode Song |

| Episode on Spotify | Episode on Apple Podcasts |

| Previous Show | Next Show |

Perpetua, Felicity, and Second Century Christian Martyrs

Gold Sponsors

Andy Olson

Bill Harris

Jeremy Hanks

John David Giese

ML Cohen

Silver Sponsors

Alexander Silver

Boaz Munro

Chad Nicholson

Francisco Vazquez

John Weretka

Lauris van Rijn

Michael Sanchez

Murilo César Ramos

Anonymous

Patrick Radowick

Steve Baldwin

Mike Swanson

Angela Rebrec

Sponsors

Aaron Burda

Alysoun Hodges

Amy Carlo

Ariela Kilinsky

Benjamin Bartemes

Brian Conn

Caroline Winther Tørring

Chloé Faulkner

Chris Brademeyer

Chris Tanzola

Daniel Serotsky

David Macher

D. Broward

Earl Killian

Haya

Henry Bakker

Joshua Edson

Kyle Pustola

Laura Ormsby

Laurent Callot

Leonie Hume

Lisa Pazer

Mark Griggs

Mr. Jim

Natasha Worle

Oli Pate

Anonymous

Anonymous

Riley Bahre

Rob Sims

Robert Baumgardner

Rod Sieg

De Sulis Minerva

Sebastiaan De Jonge

Sonya Andrews

Steven Laden

Sue Nichols

Susan Angles

Tom Wilson

Tray Davis

Verónica Ruiz Badía

When we picture martyrs, whoever they are, and whatever their reason for being persecuted, we imagine vulnerable individuals pitted against the predations of a powerful group or organization. In early Christian history, the individuals are the followers of Christ; and the prosecuting authority, generally, various officials appointed by the Roman Empire. But Christian martyr tales continued to be written centuries after the western Roman empire collapsed during the 400s. In scene after scene of Christianity’s martyr tales, from the second century onward, brave, devout men and women refuse to recant their faith in the face of execution, humiliation and torture, facing punishment with courage, attaining posthumous rewards and justice unavailable to them in the world of the living, and sometimes, inspiring others to adopt their faith precisely due to the fortitude and certainty with which they embrace death. There are many variants of the Christian martyr tale. Some chronicle the tragic fates of heroic individuals – apostles, bishops, and church and community leaders. Others record the incarceration and abuse of whole Christian communities. Out of the sizable body of early Christian martyr tales spanning over a thousand years, a few, for various reasons, are standouts, and one of these is our story for today, The Passion of Perpetua and Felicity, a text compiled and set down some time between 203 and 209 CE.

The Passion of Perpetua and Felicity is, again, not by any means the earliest Christian martyr story – a number of similar narratives precede it. Nor is it a particularly long or detailed text, being less than 6,000 words and broken up by several prophetic visions. Modern scholars have no illusions that it’s a historically reliable account from end to end, secular readers finding its miraculous occurrences dubious, and those schooled in Roman history identifying elements of the narrative that are inconsistent with otherwise well documented aspects of Roman law and social norms. Yet while The Passion of Perpetua and Felicity is by no means a historically faultless primary source, the text is nonetheless now one of the most celebrated and heavily studied documents produced by the early Christian world. Let’s talk about why.

As tragic as they are, a lot of Christian martyr tales are morally crystal clear. Bishops, monks, nuns, and consecrated virgins, untrammeled by familial connections, go bravely to their deaths, and afterward, to heaven. But Perpetua’s story is different than this. The document that we’ll look at today invites us to remember something about the real Christian martyrs who died during the various persecutions of the Roman Empire prior to the Edict of Milan in 313. The Passion of Perpetua and Felicity reminds us that Christian martyrs were not cultural outsiders, airlifted into amphitheaters to be the casualties of public blood sports and executions. Our story today invites us to remember that real Christian martyrs were inhabitants of the communities that murdered them – that their arrests, indictments, and executions tore apart religiously hybrid families, leaving children without parents, and survivors stained by the ignominy of their relatives’ punishments. Further, the story of Saint Perpetua, made up largely by a first person account of a 22-year-old wife and mother of an infant, illustrates the especially difficult plight of Christian parents facing state prosecutions. For those without strong familial attachments – the bishops and monks and nuns at center stage in so many Christian martyr tales, braving an execution for a perceived greater good was already a horrific fate. For those like Perpetua, though – a woman with a baby, and other family members asking her to recant and keep her head down, the circumstances of an arrest and prosecution could be more agonizing, and far less morally clear cut. Perpetua’s story is a messy one, and as such, in spite of its miraculous occurrences, likely far more realistic than so many other works of the same genre that have come down to us.

So, our main goal in today’s program will, once again, be to read and understand some of the history behind a text called The Passion of Perpetua and Felicity, a martyr story produced during the first 10 years of the 200s, and written about a persecution that took place in the North African city of Carthage in spring of 203. To get to Perpetua’s story, though, we’re going to have an unusually long preamble, a preamble that will take up the next thirty or so minutes. Martyr tales, as you may know, were one of the main genres of European literature for over a thousand years, and so I think this will be a good time to learn about some of the less famous martyr narratives leading up to Perpetua’s, and get our bearings in the second half of the 100s CE, where we last left off with the church fathers Irenaeus and Clement of Alexandria in the previous program. [music]

Emperor Severus (r. 193-211) and Roman Policies on Christianity Up to 200

Our sources on the The Roman Emperor Septimius Severus’ (r. 193-211) policies toward Christians are contradictory, with the Historia Augusta and Eusebius recording harsh persecutions, but Tertullian writing of Severus’ clemency toward the new religion.

Rome’s Year of the Five Emperors was 193, and out of the fracas between Pertinax, then Didius Julianus, then Pescinnius Niger, then Clodius Albinus, a 48-year-old African general named Septimius Severus emerged as victor. Severus, originally from the north central part of what is today Libya, was a seasoned, well-traveled and educated Roman by the time he came to power. Severus had held many posts and positions of responsibility in spite of the chaos wrought by the Antonine Plague on his career, among them proconsul, senior military officer, and provincial governor. All told, Septimius Severus would rule for nearly 18 years. Today, Severus is perhaps best known for cultivating a mutually advantageous relationship with the military, and ignoring everything else – especially the Senate – a tendency that many barracks emperors who followed him would successfully imitate. And in the story that we’ll hear today, Severus is ultimately the guy in charge of Rome, a veteran of many Roman offices, weathered by war and travel, hardheaded and unsentimental about holding onto power.

Severus had two sons who are relevant to our program today, as well – these were Caracalla, the older, and Geta, the younger. In March of the year 203 – the month that the events of The Passion of Perpetua and Felicity likely took place – the Emperor Severus was 57 years old. His oldest boy, the future Emperor Caracalla, was almost 15. His younger son, Geta, was turning 14, and it was, in fact, precisely Geta’s 14th birthday on which Perpetua and her companions were most likely killed in a Carthaginian amphitheater. The trio – meaning Severus, Caracalla, and Geta, may have actually been in Carthage to watch the gladiatorial games and Perpetua’s execution take place – historians are fairly certain that the imperial trio were down in North Africa during this period – but unsurprisingly, we haven’t been able to track down the daily calendar of the Severan trio. So, within the colorful realm of Roman imperial history, the saga of Severus and his sons Caracalla and Geta is a spellbinding one – the story of a calculating and hardened old Roman and two debauched heirs, one of whom eventually killed the other. But our episode today is about Perpetua of Carthage, and not the Severans, and for that reason, we need to delve into a very specific part of the Emperor Severus’ imperial policy. This is the Emperor Severus’ policy on Christianity in the Empire, if Severus even had one.

Even those of us with scarcely any knowledge of ancient history know that Christians were persecuted under the late Roman Empire. But understanding how, where, and why these persecutions took place has proved challenging to historians. First, minority social groups are persecuted in different kinds of ways. Sometimes, sporadic outbreaks of clannish fervor can lead to conflict, oppression and mistreatment. At other times, persecutions are carried out from the top down, due to central state policies. Second, while early Christian historians report both sorts of persecutions taking place, along with everything in between, some of these historians contradict one another, or are contradicted by pagan historical sources. Thus, the written history of early Christian martyrs, as we now possess it today, is an archive full of heroes, villains, loose ends, and historical implausibilities, altogether giving us the sense that while awful things happened to practitioners of the new religion during its early centuries, martyr tales were still often heavily embellished, and sometimes just made up. As historian W.H.C. Frend puts it, the earliest Christians, practicing a forbidden religion, “expected alienation from surrounding provincial society and subjection to persecution.”1 The question that we need to sort out is the extent of this subjection and persecution during the religion’s first two centuries.

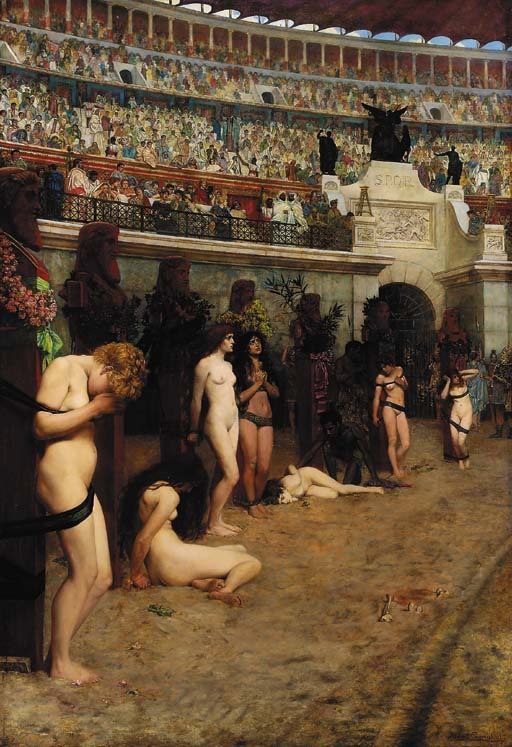

Henryk Siemiradzki’s Nero’s Torches (1876). Inspired by a few lines from Tacitus, the painting depicts Christians being burned alive after Nero scapegoated them for the Great Fire of Rome in the summer of 64 CE.

In past episodes of this podcast, we have occasionally considered anecdotal evidence in ancient Roman historians for persecutions of Christians during the religion’s first two centuries – a paragraph in Tacitus here, a few letters exchanged between the Emperor Trajan and Pliny the Younger there. We have some evidence that in late July of 64 CE, the Emperor Nero laid some of the blame for the Great Fire of Rome on the city’s tiny population of Christian citizens. We have other evidence that the Emperor Domitian, in the 90s, wasn’t taking kindly to Christians. We have other evidence still that the Emperor Trajan, around 111 or 112, was fine with provincial governors prosecuting open practitioners of Christianity with the death penalty, although Trajan emphasized that such criminals deserved the opportunity to recant, and that in such serious cases, no persecutions ought to take place according to hearsay and rumor.4 These three anecdotes from pagan sources, chronicling events under Nero in the 60s, Domitian in the 90s, and Trajan in the 110s, certainly don’t give us any sense that Christians lived safely and securely. At the same time, they’re not records of active, large scale persecutions, either. The first major, proactive state sanctioned persecution of Christians took place much later, under the reign of Decius, beginning in January of 250, and greater persecutions still unfolded under the Diocletian tetrarchy from 303 until 312, up until the Emperor Constantine passed the Edict of Milan in February of 313.

For the first three centuries of the Christianity’s history, then, Christians fell under the crosshairs of various persecutions. These persecutions varied in scope, organization and leadership. The records that we have of Christianity’s early martyrs vary in source and reliability. But it is to some of those records that we now need to turn. The full background of The Passion of Perpetua and Felicity – both the historical as well as the literary background, is now lost to us. But by learning about other Christian martyr stories that have survived that led up to The Passion of Perpetua and Felicity – beginning with narratives in the New Testament itself – we can understand the extant roots of one of the most influential genres of European literature. [music]

Christianity’s Earliest Martyrs

The Gospels of the New Testament present four versions of the same martyr narrative – the tragic death of Christ for the salvation of humanity. To state the obvious, the entire New Testament is a martyr narrative. But Christ is only one of the book’s tragic victims. The Gospels tell of the martyrdom of John the Baptist. The Book of Acts then recounts the martyrdom of Saint Stephen, and in the next century, apocryphal Acts books told of how the Apostle Paul was beheaded by Nero and how Peter was crucified upside down in the bloody years of the 60s CE. Christianity eventually produced thousands of martyr stories, some them products of real historical persecutions, others colorful fictions, and everything in between. The plots of these tales, to some extent, have widespread commonalities. Beleaguered individuals, either voluntarily or through coercion, are faced with death, and yet in the face of death, they are undaunted and courageous. Their deaths, usually attended by preternatural miracles, become tangible proof to prosecutors and spectators alike that Christianity is the sole correct religion on Earth, and frequently mass conversions follow. That is the Christian martyr story in a nutshell, one that can be found in variants in scores of languages, thousands of sculptures, stained glass windows, and altarpieces, and hundreds of millions of manuscripts, sovereign among them, once again, the New Testament itself. The Carthaginian theologian Tertullian, a contemporary and neighbor of Perpetua who will come up a lot in this episode, closed his great Apologeticus for Christianity with the assurance that “The blood of martyrs is the seed of the church,” a somewhat bleak statement, but nevertheless likely one informed by things that Tertullian had known and seen firsthand.5 And while Christian martyrdom all starts with the Gospels, in the mid second century, we begin to have stories of latter-day martyrs who came along after the Apostles. Let’s talk about some of these – in other words, the surviving narratives about Christian martyrs produced between the 150s and 180s CE. This is going to be a lot of proper nouns and information thrown at you, by the way, but our goal over the next few minutes will simply be to establish how and when the narrative structure of the Christian martyr tale first appears in the historical record, and what these martyr stories might tell us about how and where Christians were actually being persecuted during the 100s CE.Polycarp of Smyrna

The theologian and Apostolic Father Polycarp of Smyrna allegedly died in an amphitheater, being one of the earliest Christian martyrs on record.

Once in the amphitheater, a villainous proconsul tried to make Polycarp renounce his faith, but the old bishop refused, not being cowed by even the most heinous threats (IX-XI). The text lumps heathens and Jews together as equally reviling Polycarp for his avowal of being a Christian, and the letter emphasizes that Jews in particular were eager to gather up fire so that Polycarp could be burned alive (XII-XIII). Old Polycarp, during his last moments, looked around the arena and told all those present to watch closely, because he was going to be able to stand in the flames and feel nothing whatsoever (XIII). Old Polycarp voiced a prayer (XIV), and when the fire was ignited, rather than burning him, it rose around him in a corona, making him appear golden and silver, and giving off a sweet odor (XV).

Unable to kill Polycarp by burning him alive, Polycarp’s assailants instead stabbed him. But as the dagger entered the bishop’s body, a dove suddenly came forth, and then so much blood that all of the fire around him went out (XVI). With this, Polycarp passed away, and his disciples, who wanted to recover their teacher’s body, had to watch it burn afterwards (XVIII). The letter closes with an exhortation to the greatness of Polycarp, and also adds that Polycarp was the twelfth Christian to be killed in such a fashion in the city of Smyrna (XIX).

And that is Christianity’s first recorded martyrdom of a non-biblical individual. The text that tells this story, once again, is a short one of about 3,700 words, and like so many other documents from early Christianity, the narrative survives in much later manuscripts with some variations from one another. Scholars not only have no idea how much of it is true – it’s difficult to even tell precisely when the martyrdom took place, in spite of the text’s references to the city’s proconsul, although the mid-150s seem the most likely date. Almost all of the elements of the Christian martyr story are contained in what you’ve just heard – a steadfast Christian protagonist, antagonistic pagans or Jewish people, an unexpected immunity to pain or even invincibility on the part of the martyr that eventually gives way to a frequently gory death, then praises for the martyr’s bravery in the face of strife. The only additional trope missing is a subsequent mass conversion, a frequent feature of Christian martyr stories and hagiography – in other words a flock of skeptical unbelievers suddenly bowled over in the face of overwhelming supernatural evidence of the primacy of Christianity.

Ptolemaeus and Lucius

Around the same time of the martyrdom of Polycarp, another Christian text chronicled a dual martyrdom during the reign of Antoninus Pius, whose reign ended in 161.6 This second narrative, while it doesn’t exhibit the archetypal martyr story features of Polycarp’s, is interesting for different reasons. During the second and third centuries, Christian writers were drafting what we might call Apostolic seduction stories. The Acts of John, the Acts of Paul and Thecla, and Acts of Thomas all feature tales of Apostles converting beautiful married women to Christianity, incurring the wrath of those women’s husbands once the women committed to a life of celibacy, and suffering the ire of sexually frustrated pagan spouses.7 It’s an odd tale, and more than a little erotic, and precisely the one that we find in another second century Christian martyr tale set down in the pages of the very early Christian theologian Justin Martyr.

Justin Martyr wrote of Christians dying in Rome in the 150s prior to being executed himself in the 160s, the early church father being the victim of a vindictive pagan intellectual rival.

So, we’ve just looked at two very short Christian martyr stories from the 150s CE, again, the earliest to come down from us from the historical record not associated with biblical figures. While Polycarp’s death in the amphitheater in Smyrna is the quintessential martyr tale, the short anecdote about the Christians Ptolemaeus and Lucius is an excellent one to think about for a different reason. Christians could run into trouble with Roman authorities for not formally renouncing their faith, or refusing to sacrifice to the Roman Emperor, these being the most common causes for punishment in Christian martyr tales in general. But sometimes, the story is murkier, with Christians being persecuted due to class conflicts, ethnic tensions, general xenophobia and even petty everyday rivalries over family and property – in Ptolemaeus’ case, because of a jealous husband. None of this is surprising, but it’s still useful to know that Christianity’s first two martyr stories concern first a theologically motivated execution, and then multiple executions rooted in a lover’s quarrel. Christian martyr stories generally fit beneath one or the other side of this binary – in some of them, Christians destroyed by Death Star like states bent on taking down all Christians, and in others, Christians killed by villainous neighbors who use state laws to further personal vendettas. With that – not exactly cheery – pair of stories from the 150s completed, let’s move forward to the 160s.

The Martyrdom of Justin Martyr

The theologian Justin Martyr, who gives us the story of poor Ptolemaeus and his friend Lucius, ultimately executed out of husbandly jealousy, was later himself executed. The circumstances of Justin Martyr’s execution in roughly the year 165 are related in a couple of different sources. The historian Eusebius wrote that a philosopher named Crescens, of the Cynical school of Greek philosophy, set his sights on having Justin executed after wrangling with the intellectually resourceful Christian in public debates, and not doing very well.10 Subsequently, according to a text called the Acts of Justin and Companions, a prefect named Rusticus cross examined Justin and then his companions, asking them if they were Christians, and whether they were really sure they wanted to die rather than just offering a sacrifice to the Roman gods. Justin and company refused, and the prosecuting officer Rusticus, in the end, proclaimed, “Let those who have refused to sacrifice to the gods, and to yield to the command of the emperor, be scourged and led away, suffering the penalty of decapitation according to the laws.”11 This short narrative offers no lurid or dramatic execution scene, merely telling us that poor Justin was beheaded for being a Christian. This state sanctioned decapitation, again, would have taken place in the mid-160s, and while the exact history it records may be a bit wobbly, we can still imagine that executions of Christian intellectuals like Justin Martyr were indeed sometimes spurred on by sorts of professional rivalries like the one Eusebius records. Stoics and cynic philosophers could dig into one another for years to no avail, but Christian people, while clearly allowed to grow and spread their beliefs below the radar, could suffer dire fates if they dared to stick their necks out.Let’s look at just a couple more very early Christian martyr tales from the second century. Justin Martyr, again, is thought to have died in the mid-160s, and from the next decade, roughly the year 177, we have another martyr tale from Christian annals probably based on real events. This is a text called the Letter of the Churches of Lyons and Vienne, an epistle about 5,000 words in length that the historian Eusebius quotes in full at the outset of the fifth book of his Ecclesiastical History. So far, our martyr tales briefly covered in this program have been out of the easternmost Aegean Sea and Rome, but the Letter of the Churches of Lyons and Vienne, as the name implies, records events from Gaul – specifically, the east-southeast region of modern day France. In the 170s, Lyon, then called Lugdunum, and its smaller neighbor Vienne, just ten miles to the south along the Rhône River, were already home to Christian institutions. Let’s hear what the letter that Eusebius quotes in full has to say – a 5,000 or so word text once again about a persecution that took place in about 177 in and around Lugdunum, which, though Marcus Aurelius is not mentioned in the letter, remains one of the uglier marks on the record of his imperial tenure. [music]

The Massacre at Lyons and Vienne

The Letter of the Churches of Lyons and Vienne was written by a Christian person who personally suffered from the persecutions that took place in Gaul – in other words it uses the word “us” to indicate the Christian community, and opens with a description of how Satan got his sights set on the Christians around Lugdunum.12 The letter says that first, gradually, Christians were barred from the cities’ baths and marketplaces, and eventually, that Christians were not allowed to be seen in public. The letter describes what Christians endured – “the injuries heaped upon them by the populace; clamors and blows and dragging and robberies and stoning and imprisonments, and all things which an infuriated mob delight in inflicting on enemies and adversaries” (V.1.7).13 Eventually, these sporadic outbreaks of prejudice culminated in a mass-imprisonment of the region’s Christians, who were rounded up and incarcerated to await the arrival of the provincial governor, who would formally sentence them. A devout and well-reputed local Christian attempted to intervene on behalf of his brethren, but he was also imprisoned.

The Amphitheatre Trois Gaules in Lyons, where Christian commoners were massacred in 177. Photo by arno.

And yet in spite of all of this, the Christian prisoners kept up good spirits, some even thinking of their chains and bonds as marks of special distinction, and others falling into a more grim quietude. More executions proceeded, with the three most brazen and undaunted of the Christians taken to the city amphitheater to be mangled by animals. This trio, for a time, survived the awful tortures of the arena, not satisfying their persecutors with cries of agony. While two were killed, the third, the slave woman Blandia, was hung on a stake to be eaten, but no wild animal would come near her, and so she was tossed back into prison. Stuck back in jail, then, the Christians of Ludgunum rallied one another. It soon became clear that a final death sentence would be imposed, as “Caesar commanded that they should be put to death, but that any who might deny should be set free” (V.1.47). Evidently, none of the local Christians did recant, because the citizens among them were beheaded, and the noncitizens were sent to be mauled by animals in the arena. There, one Christian dramatically refused to disavow his faith while being burned in an iron chair. The poor slave Blandia, who’d already endured torture in the arena, was finally executed after suffering more physical punishments. Dogs were loosed to eat the bodies of Christians who had died in the prison, and the severed heads of Christian citizens were stacked along the charred remains of those who had perished in the amphitheater. Eventually, the ashen remains of the once tidy Christian community of Lugdunum were kicked into the Rhône River.

So that was a summary of the shocking events recorded in the famous Letter of the Churches of Lyons and Vienne, which itself is preserved in the fifth book of Eusebius’ Ecclesiastical History, events that in some form or another occurred in and around modern day Lyons, France in 177 CE. In addition to Tacitus’ historical account of Christians being blamed and punished for the Great Fire of Rome in 64 CE, the later letter from Lugdunum is the earliest historical record we have of a mass persecution of Christians in the Roman Empire. Now I do want to make some summary remarks about all of these early martyrdom accounts, especially because as you’ve seen, the texts recording the deaths of Polycarp, those of Ptolemaeus and Lucius, those of Justin Martyr and his companions, and those of the Gallic Christians of Lugdunum – in these texts persecution breaks out in different ways and with different causes. But first, I want to look at one more Christian martyr story from the second century, and this one will really complete a full inventory of the genre’s main works from this period.

The Scillitan Martyrs

The last martyr story I want to look at prior to The Passion of Perpetua and Felicity is the story of the Scillitan Martyrs. Scillium, where they lived, was a city in what’s now the western part of modern day Tunisia – today, the city of Kasserine. The text that we have about them is called the Acts of the Scillitan Martyrs, and it may have just been a court document. This document is the earliest text to record the presence of Christianity in North Africa – sad that that’s the case, by the way, since it’s a martyr story. Anyway, the Scillitan martyrs were a group of twelve Christians executed in 180 CE, just a few years after the persecution at Lugdunum back in 177. The document records a confrontation between a provincial governor named Saturninus, and some of the Christians in question. In a scene similar to some we’ve already heard in this program, a Roman authority asked the Scillitan Christians a few questions – wouldn’t they simply keep their heads down like everyone else and offer a sacrifice to the emperor? Wouldn’t they swear by emperor’s name, attain his mercy, and go on with their lives? But outspoken members of the Scillitan Martyrs declined to do so, one emphasizing that he acknowledged no authorities on earth, another, a little more diplomatically, saying that she respected Caesar’s authority on earth, but that it was only the Christian god that she feared. The prosecuting governor then asked if the Scillitan Christians would like thirty days to think over their decision. The Christians declined, and they were immediately sentenced to execution and beheaded. The entire surviving text about them is just over 500 words.As short as the Acts of the Scillitan Martyrs is, though, it still rounds out our overview of second century Christian martyr stories and brings us into the neighborhood of Carthage, where we will be for the remainder of this episode. Before we continue on to The Passion of Perpetua and Felicity, though, let’s think about what we’ve learned up to this point from the primary sources. From a literary perspective, we’ve learned plenty. The story of Polycarp, that of Ptolemaeus and Lucius, that of Justin Martyr, the victims of the massacre in Lugdunum in 177 and the executions near Carthage in 180 – these narratives all offer the core elements of the Christian martyr story. The superstructure of the Christian martyr story likely has roots in stoic philosophy. Stoic philosophy, burning brightly over the first two centuries CE in the pages writers like Seneca, Epictetus, and Marcus Aurelius, prized courage and mental equipoise in the face of calamity and death. Around time the Paul was situating various stoic ideas into his epistles, an unknown Jewish writer was authoring 4 Maccabees, an apocryphal martyr story of a family of Jews brutally tortured in front of one another all told to demonstrate, in the words of the book’s author, that “the emotions of the appetites are restrained, checked by the temperate mind, and all the impulses of the body are bridled by reason” (4 Macc 1:35)14 From a strictly literary perspective, then, by the time the 100s CE began, Christians writing in Greek and Latin inhabited a world in which facing death with unapologetic courage was an idea widespread in manuscripts and public lectures all around them – from celebrated pagan philosophers like Seneca, to Jewish intellectuals, to the towering and impassive figure of Christ in the Gospel of John.

All that said, though, the five martyr stories we’ve recounted thus far, chronicling events between 150 and 180, aren’t just words on pages, influenced by other words on other pages. Somewhere behind these early narratives is the historical reality of how Christians were actually perceived and understood by their neighbors during these decades, and how they were legally processed during the late Nerva-Antonine dynasty if they ran afoul of authorities. In a sentence, the evidence that we have from this period suggests that Christians were vulnerable to outbreaks of persecution like the nightmarish events that Eusebius quotes as having unfolded at Lugdunum in 177, but that these persecutions were rooted in local communities and regional authorities, and thus their scale and severity were limited by the patchwork nature of Roman provincial administrations. And I think at this point, the best way get a little closer to the largely lost history of second century Christianity is to take a long, careful look at The Passion of Perpetua and Felicity, a text once again written some time before 209 about events that took place in March of 203 in the city of Carthage. [music]

Carthage and Christianity in Severan North Africa

By the beginning of the 200s, Carthage had become one of the more influential cities in the Roman Empire. A breadbasket and port city with hundreds of thousands of citizens, Carthage and its environs also had the distinction of being the home region of the aforementioned Septimius Severus, who again ruled Rome from 193-211, being the first Roman Emperor from Africa. The ancient Latin Historia Augusta tells us that the stingy old Severus himself was “regarded by the Africans as a God” (13.8), and that in the whirlwind of damage control missions that consumed the front end of his career, at one point Severus returned to his North African homeland to stabilize territory there (18.3), and that Severus continued to have a Punic accent until the end of his life.15 In the city of Carthage, Greek, Latin, and Punic were used among the population. The arable flatlands to the west of the city, where the Medjerda River still flows today, were home to crop plantations whose bounty propped up the local aristocracy – men and women like Perpetua’s own family. Now, the story of Christianity’s expansion throughout the Roman Empire in the second century is a vast one, but the African provinces seem to have been an area particularly rife with conversions from an early point. As scholar Aula Fredriksen puts it, “North Africa was the ‘Bible belt’ of the Mediterranean. At once severe and enthusiastic, fundamentalist and traditional in their biblical orientation and proud of their origins as the ‘church of the martyrs,’ North African Christians gave the Latin church its earliest acta martyrorum,” the latter term meaning “acts of martyrs” or texts about martyrdoms.16 And among these early texts was The Passion of Perpetua and Felicity.

Roman North Africa during the second century CE. Map by Sting

By the time Perpetua died in the year 203, the Carthaginian Christian church father Tertullian was middle aged. Back in 197, Tertullian reminded the Christians of Carthage that they were “spread all over the world.” Addressing the unconverted people of the Empire more generally, Tertullian wrote that “[Christians] are but of yesterday, and we have filled every place among you – cities, islands, fortresses, towns, market-places, the very camp, tribes, companies, palace, senate, forum, – we have left nothing to you but the temples of your gods” (Apol 37).17 We’ll talk a bit more about Tertullian later, but in any case, his proud remarks about the swelling ranks of Christianity, written in North Africa as the second century gave way to the third, attests to the prevalence and health of Christianity in the region. Christianity’s vitality in the African provinces, surprisingly, was not hindered by the events of the later 200s CE. Students of Roman history are familiar with the great Crisis of the Third Century, that series of imperial usurpations that stretched from the end of the Severan dynasty in 235 until the reign of Diocletian in 286. This famous period of turmoil impacted the Empire asymmetrically, leaving entire regions, like Britain, largely serene and untroubled. The Crisis of the Third Century, according to historian Roger Collins, “was also a period of considerable prosperity for the cities of Roman Africa, which show fewer symptoms of urban decline that could be detected in many other regions of the Empire.”18 With plenty of practicing Christians already alive and well in North Africa by 197, according to Tertullian, we can imagine that the general prosperity of North Africa over the third century, and the social harmony generally fostered by economic plentitude, only aided the spread of Christianity in modern day Egypt, Libya, Tunisia and Algeria while so much of the rest of the Empire fell on hard times.

Ruins of the Antonine Baths in Carthage. These would have been built during the lives of Perpetua’s parents, and are the largest archaeological remnants of Roman baths on the African continent.

But there are problems with this assessment. The first is that the Historia Augusta, though our only source on large chunks of imperial Roman history, is notoriously unreliable, as is Eusebius’ History, both being products of later centuries. The second is that Tertullian himself, a Christian person alive in Severus’ home turf for the entire duration of Severus’ reign, has only good things to say about the austere graybeard Emperor Severus. Tertullian writes that “Severus himself. . .was graciously mindful of the Christians. . .Both women and men of highest rank, whom Severus knew well to be Christians, were not merely permitted by him to remain uninjured; but he even bore distinguished testimony in their favour.”21 This assessment doesn’t conclusively prove that Severus had a blanket policy of tolerance for all Christians, but it’s a very strong data point contradicting later claims that Severus had it in for Christianity.

So now, with this substantial background out of the way, I think we’re ready to hear the story of Perpetua and Felicity. This martyr narrative takes us into the secret byways of Carthaginian Christianity at the dawn of the third century. Its protagonists, a noblewoman, companions, and slaves – all recent converts to the religion, were likely ushered into the Christian fold in house churches. Cult religions in the Ancient Mediterranean – those practiced out of sight of public temples and governmentally appointed functionaries – cult religions like Christianity not only offered converts like Perpetua comforting messages and community. By 203, the clandestine shared meals and back room meetings of Christianity also allowed women and slaves freedom of expression and spiritual equity that Roman society more broadly denied them. In house churches throughout the Empire, early Christians could form friendships that crossed social boundaries, and pursue learning and connections beneath the radar of local authorities. But when an aristocratic Roman matron converted – a person considered by her society predominantly as a mechanism for creating male heirs and transferring wealth, patriarchs and civic authorities saw a dangerous crack in the social order. This was Perpetua’s plight, and what makes her story especially tragic, even if you don’t share an iota of her religious beliefs – she seems to have been an energetic person attracted to a countercultural movement that promised something more than being another brick in the wall of Roman Carthage. And for her dissidence, as we will now see, she incurred awful punishments. [music]

Perpetua‘s Opening: The Redactor

As we open the actual pages of The Passion of Perpetua and Felicity, the first thing we need to understand is that this text is something of a chimera – a hybrid work built from different parts. In all likelihood, the document had multiple authors, considering the different prose styles of its different sections. We’ll consider these sections as we get to them, beginning with the first one. The initial section is the work of some sort of redactor – editor Thomas Heffernan simply calls this person “R,” for “redactor.” The redactor of this martyr tale writes long, erudite Latin sentences with intricate clausal relationships.22 The redactor is interested in framing the interior portions of the narrative, allegedly by the martyrs themselves, and presenting them to the reader in such a fashion that explains and amplifies their importance. We’ve heard five other tales of earlier martyrs in this program – again Polycarp of Smyrna, Ptolemaeus and Lucius, Justin Martyr, the massacre at Lugdunum, and the Scillitan Martyrs, but none of these earlier tales commence with the careful posturing that The Passion of Perpetua and Felicity does. Whoever edited and framed Perpetua’s story wanted it to be received in a very specific fashion. The text’s redactor thus begins the martyr tale with a formal philosophical question. Let’s hear that question – this is the R.E. Wallis translation – the first words of The Passion of Perpetua and Felicity:If ancient illustrations of faith which both testify to God’s grace and tend to man’s edification are collected in writing, so that by the perusal of them, as if by the reproduction of the facts, as well God may be honoured, as man may be strengthened; why should not new instances be also collected, that shall be equally suitable for both purposes, – if only on the ground that these modern examples will one day become ancient and available for posterity, although in their present time they are esteemed of less authority, by reason of the presumed veneration for antiquity? But let men look to it, if they judge the power of the Holy Spirit to be one, according to the times and seasons; since some things of later date must be esteemed of more account as being nearer to the very last times, in accordance with the exuberance of grace manifested to the final periods determined for the world. (I.1-2)23

In its opening moments, the text admits to being a new and squeaky clean story. At the same time, Perpetua’s editor asserts that although Christianity has tended to favor texts and heroes from bygone centuries, present will one day be past, and just as Christianity first blossomed from Christ’s manifestation on earth, an equally holy time of deliverance eventually coming, and every subsequent generation that lives lies closer to this final period of grace and justice. In two long sentences, then, Perpetua’s redactor opens by telling us that no time in Christian history is holier than another time, and that the present, and recent past should be revered just as much as the Apostolic age nearly two centuries before. A moment later, the text again asseverates the importance of the present as well as the past, writing, “[W]e. . .honor the new prophecies and new visions as well. . .lest any person who is weak or despairing in their faith should think that only the ancients received divine grace” (I.5).24 These are very important claims – around 200 CE, the subject of whether latter-day Christians could receive direct revelation was a hotly debated subject, and one which we’ll talk about later. In any case, with his prefatory remarks complete, the redactor then offers us some background on the story’s main characters.

In Carthage, in March of 203 CE, an arrest took place.25 Five people in total were arrested. Among them were two slaves, Revocatus and Felicity, who was pregnant. There two freemen, and their names were Saturninus and Secundulus. And arrested alongside them, as the text tells us, “was also Vibia Perpetua – a woman well born, liberally educated, and honorably married” (II.2). Perpetua was around 22 years old, and had an infant son with her at the time of her arrest. All of those arrested were of a group called catechumens, or literally, “those being instructed” or “those receiving catechesis.” Catechumens, in this and other periods of Christian history, means Christians who have converted and are in the process of learning the religion’s doctrines, but who have not yet been baptized. And with this background established, the author of the short frame narrative announces that he will now let Perpetua’s diary speak for itself, as “from this point there follows a complete account of her martyrdom, as she left it, written in her own hand and in accordance with her own understanding” (II.3). [music]

Perpetua’s Narration of Her Indictment and Captivity

Perpetua’s own prose is different than the redactor’s. Her sentences are shorter, and her diction more full of colloquialisms. We don’t know if the section allegedly written by Perpetua is genuine – we can get into that later – I just wanted to emphasize that if you were reading this text for yourself right now, you would notice a stylistic difference when you jumped from the redactor’s section to Perpetua’s own. Perpetua’s actual prison diary begins by recounting a dramatic scene that took place while she and her fellow catechumens were being prosecuted. Her father, whom the narrative never identifies as a Christian, did not want his daughter to be butchered on account of her religion. But when he asked Perpetua if she’d recant her faith to save her life, Perpetua said this wasn’t going to happen. Perpetua gestured to a nearby pitcher, and asked him if it could be anything other than a little pitcher. Perpetua’s father said it was certainly stuck being what it was – a pitcher. Perpetua said the same was the case with her – she was a Christian, and would not affect to be otherwise.26 Her father, enraged, lunged at her with the intention of gouging her eyes out. Side note, yes, that’s awfully strange, but let’s just go with it – her dad reasoned with her to recant, and when she refused, he abruptly went berserk.Anyway, following this ugly incident, Perpetua felt that she had been tested and emerged triumphant. Within a few days, Perpetua and the other converts were baptized. It seems that even though Christians were being persecuted in Carthage, Christian religious rites were still permitted for convicts, and Perpetua may have been on something more like house arrest than locked behind bars at this point in the narrative. Whatever her exact quarters, and legal status in the days following her trial, shortly after her baptism, Perpetua and her fellow converts were taken to an actual prison. I’m going to read a short section of the older R.E. Wallis translation – this passage is on the subject of Perpetua’s initial incarceration. She writes,

After a few days we are taken into the dungeon, and I was very much afraid, because I had never felt such darkness. O terrible day! O the fierce heat of the shock of the soldiery, because of the crowds! I was very unusually distressed by my anxiety for my infant. There were present there Tertius and Pomponius, the blessed deacons who ministered to us, and had arranged by a means of gratuity that we might be refreshed by being sent out for a few hours into a pleasanter part of the prison. Then going out of the dungeon, all attended to their own wants. I suckled my child, which was no enfeebled with hunger. In my anxiety for it, I addressed my mother and comforted my brother, and commended to their care my son. I was languishing because I had seen them languishing on my account. Such solicitude I suffered for many days, and I obtained leave for my infant to remain in the dungeon with me; and; and forthwith I grew strong and was relieved from distress and anxiety about my infant; and the dungeon became to me as it were a palace, so that I preferred being there to being elsewhere. (III.5-9)

Perpetua’s initial fear and trepidation, then, were mollified when she was able to feed her baby and had made sure that he would be cared for after her probable execution, and, with his fate secure, her imprisonment seemed much more bearable.

Soon, Perpetua’s brother visited her, and told her that she was very much admired, and that she should try to gain a vision of things to come. Perpetua, confident indeed that she could speak to Christ, soon had a dream about the future. This is what she saw.

Perpetua’s First Vision: The Ladder to Heaven

In Perpetua’s vision, she saw a bronze ladder stretching almost infinitely upward to the heavens. It was a perilous ladder. All along its sides were iron weapons – daggers, hooks, and swords, which could tear the skin off of anyone who climbed too hastily. And at the bottom of the ladder there waited a giant snake – a snake that threatened anyone from even trying to climb the ladder in the first place, and was there to devour anyone who fell off of the ladder. Perpetua first saw her thus far unmentioned Christian instructor, Saturus, not to be confused with Saturninus, a freedman Christian convert with whom Perpetua had been arrested. The Christian teacher Saturus, she writes, had been the reason the rest of them had converted, and when Perpetua and company had been apprehended, Saturus had turned himself in, proving his devotion not only to Christianity, but to those catechumens who had followed him in their conversions. In Perpetua’s vision, Saturus summited the ladder first, and encouraged her to follow. Steeled by Saturus’ presence, Perpetua stepped on the head of the giant snake at the bottom of the ladder, this being her first step upward to heaven.Her vision then fast forwarded to the ladder’s top. There, she had a vision of heaven, one fairly standard to second and third century apocalyptic literature. Perpetua saw a vast garden, and a large, snowy-haired man milking sheep and surrounded by people wearing white. The shepherd then fed Perpetua a dollop of cheese, and all of the celestial assembly proclaimed, “Amen” (IV.9). And this was the vision that Perpetua had – when she awoke from it, she still had the taste of the dream cheese in her mouth. She told her brother about the vision, and said it led her to conclude that she and the other Christian prisoners now had to resign their hopes in the material world.

Perpetua and Her Baby

If Perpetua’s brother respected his sister’s Christianity to some extent, Perpetua’s father continued to obstinately try and convince her to recant and live out her life like a normal Roman wife and mother. When we first meet Perpetua’s father in the diary, he comes across as rather monstrous, in that he literally tries to gouge his daughter’s eyes out. In his second appearance, however, Perpetua’s father is a teary Roman patriarch, asking his daughter to recant because he loves her, and because if she perishes in such an ignominious fashion it will hurt the family. Here’s a scene in which Perpetua’s father tries to change her mind in the Wallis translation. And then my father came to me from the city, worn out with anxiety. He came up to me, that he might cast me down, saying, ‘. . .Have pity on your father, if I am worthy to be called a father by you. If with these hands I have brought you up to this flower of your age, if I have preferred you to all your brothers, do not deliver me up to the scorn of men. Have regard to your brothers, have regard to your mother and your aunt, have regard to your son, who will not be able to live after you. Lay aside your courage, and do not bring us all to destruction; for none of us will speak in freedom if you should suffer anything.’ (V.1-4) In addition to the words of his hopeful petition, Perpetua’s father also threw himself at her feet, kissing her hands. Perpetua tells us she felt sorry for him, because “he alone of all my family would not rejoice in my suffering” (V.6). Though she tried to comfort her father with an assurance that she was under the care of the divine, her father was still clearly devastated. Perpetua was given other chances to save her life, and the life of her baby. Her lunch in prison was interrupted on one occasion when an assembly retrieved her and brought her out into the city forum. In the public square Perpetua was taken out and placed on a platform. She was asked to make a sacrifice for the sake of the Roman Emperor’s health. Perpetua refused. The ruling Roman official present, a procurator called Hilarianus, asked if Perpetua were a Christian, and she said indeed she was. Perpetua’s father begged her to make the sacrifice for the Emperor’s health, and for his interruption of the proceedings, he was then beaten while Perpetua watched. Perpetua admits that she felt bad for the old man. It was at this juncture that the small Christian company’s sentences were formally pronounced. They learned that they were to be killed by animals in the gladiatorial arena. Following the proclamation of their death sentence, Perpetua tells us, “we descended the platform and returned cheerfully to prison” (IV.6). Perpetua then tried to have her baby sent to her to nurse, but her father refused. Miraculously, thereafter, the baby no longer needed Perpetua’s breast milk, and she stopped lactating. [music]Perpetua’s Second Vision: Her Deceased Brother

As her days on death row dragged by, Perpetua thought of her thus far unmentioned dead brother. His name was Dinocrates. She tells us “never before then had his name entered my mind” (VII.1), a confusing little smudge of prose, considering the fact that he was her departed brother, and that she must have, in a literal sense, realized that she had a sibling. What I believe the text intends to say, based on what comes after, is that it was while Perpetua was in prison, following the issuance of her execution sentence, that as a Christian she pondered her departed brother’s fate for the first time. Her brother Dinocrates, she tells us, had died at age seven of some awful form of cancer that had caused facial disfigurement. And there in the penitentiary, she had a vision of her dead brother – he was stuck in a lightless, crowded place, parched with thirst, still grossly mangled by his illness. Perpetua’s brother Dinocrates’ torment, in her vision, was like that of the Greek hero Tantalus – little Dinocrates was adjacent to a pool full of water, but, being a little boy, he couldn’t reach it to drink.Seeing her brother’s awful posthumous torture, Perpetua prayed and prayed for him, even as she and her fellow prisoners were moved to a military prison just prior to their execution. She was gladdened, after they relocated, to have a new vision of little Dinocrates – this one a happier one. Evidently her prayers had gone through, because in Perpetua’s second vision of her departed brother, Dinocrates’ face had healed, and the he could easily reach the water. In fact, the youngster had not only reached it – he had been drinking it from a golden cup, and was playing and laughing in the water the way that all little kids did. [music]

Perpetua’s Third Vision: An Arena Fight

Jean-Léon Gérôme’s The Christian Martyrs’ Last Prayer (1863-83), a haunting image inspired by martyr narratives like Perpetua’s.

The day prior to her execution, Perpetua saw her deacon in a vision – the third of Perpetua’s three visions in the narrative. In this third vision, the deacon brought her along strange and rugged trails that ended in the amphitheater, and then he brought Perpetua into the center of the sands and told her that he would be with her and share what was to come. Her vision then continued – all the animals she had expected to consume her do not do so. And as Perpetua’s narrative of her final vision continues, it gets quite odd. An Egyptian warrior was deployed to fight her in the arena. But Perpetua was suddenly flanked by handsome youths. She was stripped naked, transformed into a man, and oiled in preparation for combat. Then in the vision another man appeared – this one enormous in size, simultaneously a sort of Christ figure and master of the gladiatorial games, and the giant said that Perpetua would now fight the Egyptian. Perpetua did so, and after a somewhat awkward sounding bout of hand-to-hand combat, Perpetua was victorious, and she was given a sacred branch as her reward. As she interpreted her dream, the next day she would indeed die in the gladiatorial arena, but her fight wouldn’t be with any wild animals or bloodthirsty gladiators – it would be with Satan himself.

Now, Perpetua up to this point in the narrative has had three visions while incarcerated – the ladder to heaven, the dead brother, and then fighting the mysterious adversary in the arena. But at this point, the text is going to change gears a bit, and give us quite a long narrative of another vision – this vision belonging to Perpetua’s companion Saturus. Saturus, we are told earlier in the text, was a teacher instrumental to Perpetua’s own conversion to Christianity, and also a man who volunteered to go to prison with those he’d converted, so in Perpetua’s diary he’s certainly a Christian of conviction and a person who feels strong accountability for his actions. So let’s hear about the vision of Saturus, a lengthy insert in this longer martyr story. [music]

The Vision of the Christian Teacher Saturus

Saturus’ section was probably written by a third author – it is highly literary, and swarms with allusions to scriptures.27 In Saturus’ vision, he foresaw himself and his companions dying, and then being escorted eastward by four angels, going upwards and upwards. Before them opened a vast garden, and there were rose trees and other trees with leaves that always fell. In the celestial garden, four more angels were there to meet the new arrivals. Other recent martyrs were there, but before Perpetua’s company could make conversation with them, they were brought in to meet Christ. In Saturus’ vision, Christ was an old man with a youthful face, and they kissed him before being dismissed to go and explore the garden outside.The Christian teacher Saturus’ vision continued. Once he and Perpetua and their companions were left to explore the florid grounds of heaven again, Perpetua and Saturus talked with some prominent Christians they knew – a bishop and a priest. In the midst of their conversation, angels came and rebuked the bishop, telling the bishop he should try and forestall the factionalism among his Christian subjects down on earth. This would have been tricky affair, since the bishop was dead, but at any rate, we hear no more on the subject, and, after Saturus explains that he and Perpetua met other Christians there and other martyrs, and that it smelled wonderfully in heaven, the narrative of Saturus’ vision ends.

At this point in the narrative, we learn a little more about those incarcerated alongside Perpetua and her teacher Saturus. One of these was the slave Felicity, eight months pregnant, and, according to the text, “in agony, fearing that her pregnancy would spare her (since it was not permitted to punish pregnant women in public)” (XV.2). To spare Felicity from not being executed in the gladiatorial arena, her fellow inmates held a prayer meeting, and through their ardent supplications, they were able to make Felicity give birth. Jailors, watching the affair, remarked on how much Felicity was suffering during the premature birth of her baby, but she told them she was unafraid – when the time came, Christ would take her sufferings on his shoulders. The narrator tells us that as for Felicity’s newborn baby, “a certain sister brought [her] up as her own daughter” (XV.7).

As the hours before their executions dwindled, Perpetua importuned a tribune in charge of the military prison for special treatment. She said she and the other Christians were the highest ranking nobles scheduled to be killed the following day for young Emperor Geta’s birthday celebration. Shouldn’t they be able to have a nice meal and be refreshed prior to their public executions, so that they’d look their part? Shouldn’t they also be able to meet with guests? Evidently Perpetua’s plea for special treatment was heeded, because Perpetua and her companions were indeed allowed to have guests.

They also had a final meal – some sort of a public meal – prior to the execution, because a mob was there, watching the Christians furiously. Rather than remaining meek and mild, though Perpetua and her companions told the spectators that God would punish them, and Saturus, offering a milder rebuke, told the crowd that the looming executions should satisfy their rancor. Some of the ill-willed onlookers, at that point, abruptly converted. [music]

The Execution of the Christian Prisoners

The next day, the Christian prisoners were led from the prison to the Carthaginian coliseum to be killed. Here’s one last long quote from that older R.E. Wallis translation:The day of their victory shone forth, and they proceeded from the prison into the amphitheatre, as if to an assembly, joyous and of brilliant countenances; if perchance shrinking, it was with joy, and not with fear. Perpetua followed with placid look, and with step and gait as a matron of Christ, beloved of God; casting down the luster of her eyes from the gaze of all. Moreover, Felicit[y], rejoicing that she had safely brought forth, so that she might fight with the wild beasts; from the blood and from the midwife to the gladiator, to wash after childbirth in a second baptism. And when they were brought to the gate, and were constrained to put on the clothing – the men, that of the priests of Saturn, and the women, that of those who were consecrated to Ceres – that noble-minded woman [Perpetua] resisted even to the end with constancy. For she said, ‘We have come thus far of our own accord, for this reason, that our liberty might not be restrained. For this reason we have yielded our minds, that we might not do any such thing as this: we have agreed on this with you.’ Injustice acknowledged justice; the tribune yielded to their being brought as simply as they were. (XVIII.1-6)

Perpetua then began singing a hymn. Her companions shouted threats up to the stands, and told the Procurator who’d sentenced them that they would be judged by Christ. The crowd cried out, enraged, and asked for their punishment to be hastened.

What follows in the narrative is an inventory of how each Christian present died on the sands. Each Christian, we learn, had prayed for a certain kind of death based on their personal preferences. As for the teacher Saturus, he had wished to be killed by animals. A boar that was supposed to gore and kill him instead killed its handler. A bear that was supposed to eat Saturus refused to leave its cage.

As for Perpetua and Felicity, they were to be killed by a wild cow. The pair were stripped naked and draped in nets. Seeing the pitiful duo out actually out on the sands, the assembled spectators felt sudden remorse – these were helpless people, obviously, and one of them – Felicity – was lactating. So that the brutal execution would be done in better taste, evidently, Perpetua and Felicity were then dressed in loose robes. What happens next is one of the stranger passages even in the often bizarre annals of Christian martyr stories – this is the new gold standard Thomas Heffernan translation, published by Oxford in 2012.

So [Perpetua and Felicity] were called back and dressed in unbelted robes. Perpetua was thrown down first and fell on her loins. Then sitting up, she noticed that her tunic was ripped on the side, and so she drew it to cover up her thigh, more mindful of her modesty than her suffering. Then she requested a pin and she tied up her tousled hair; for it was not right for a martyr to suffer with disheveled hair. . .Then she got up; and when she saw Felicity crushed to the ground, she went over to her, gave her her hand and helped her up. (XX.3-6)

A lot to unpack there, obviously, and for now it will suffice to say that whoever wrote and compiled this text had a very clear, valorous, and even cinematic image that they wanted to convey of what a martyrdom looked like, and also thought that fixing one’s hair and requesting a replacement hairpin would be on the mind of someone suffering a horrifying public execution. For now let’s continue – I don’t want to interrupt the climax that that the narrative has been building toward.

Perpetua and Felicity had been roughed up by the wild cow, but they were still alive, and they were brought over to the side of the arena, to an area of relative safety. There, we learn, Perpetua was in a state of religious ecstasy so intense that she didn’t even remember being attacked by the wild cow. She summoned her brother over and told him to be steadfast.

Now, as for Saturus, who had foreseen his own death by a beast, he was indeed mortally wounded by a leopard, which delivered a killing blow in a single bite. While it was a deathblow, Saturus still had a chance to tell a soldier to have faith and to let what he had seen strengthen him – Saturus even asked the soldier to borrow his ring for a moment, which Saturus dipped in his own death wound before handing it back to the officiating soldier as a token of remembrance.

It was normal, after such gruesome public executions, for those maimed and wounded to be finished off beyond the view of the spectators. According to this text, however, the crowd present at Perpetua’s execution wanted to see the final finishing off, and at their behest, miraculously, the battered and mangled Christians were all able to walk on their own into the arena. They kissed one another, and were silent and unmoving as Roman executioners ran them through with swords. Only Perpetua screamed in agony, we are told, because she wanted to feel some of the pain of it all, and when the gladiator killing her hesitated before cutting her throat, she guided his hand to finish the job. As the narrator puts it, “Perhaps such a woman, feared as she was by the unclean spirit, could not have been killed unless she herself had willed it” (XXI.10).

The Passion of Perpetua and Felicity ends with the same emphasis it began, telling us that these later Christian martyrdoms are just as honorable and exemplary as any event that has happened in Christianity’s history. And that’s the end.

The Historicity of The Passion of Perpetua and Felicity

In the time that we have left in this program, I want to talk about two main things. The first is, put plainly, whether anything you just heard in that narrative actually happened, and in particular, whether a 22-year-old Roman noblewoman, a class not associated with literacy or learning due to social customs, could have actually penned a visionary prison diary in the week or so before her death. While I don’t want to spend too much time on the nitty gritty of the text’s legitimacy, I do want to go through the basic evidence for and against the narrative being genuine. So let’s jump right into that, let’s consider evidence for it being a primary source, with parts actually written by the martyrs Perpetua and Saturus themselves.

Herbert Gustave Schmalz’s Faithful unto Death (1888). The most curious feature of The Passion of Perpetua and Felicity may be Perpetua’s own execution in the Carthaginian amphitheater – Roman honestiores, or nobles, were killed by execution, rather than being massacred in an amphitheater, when state law demanded it.

While the unusual structure of the text hints at the strong possibility of earlier, primary sources being partially or fully leveraged by what we read today, there are nevertheless significant reasons to doubt the document’s historicity. Perhaps the strongest is Perpetua’s actual execution in the amphitheater. Roman aristocrats, or honestiores, were executed by being beheaded, and not by animals in an amphitheater, or damnatio ad bestias. An earlier martyr narrative we looked at – the Letter of the Churches of Lyons and Vienne, describes the Christian citizens of Lugdunum being beheaded – only the Christian slaves are tortured and killed in the amphitheater. The very nature of Perpetua’s death in the text, then, is one of the strongest pieces of evidence that whoever compiled it was taking substantial artistic license.

Additionally, there is an issue related to Perpetua’s child. Modern readers of the text might wince at Perpetua’s willingness to abandon her infant for the sake of a martyrdom. But to Roman readers, scenes featuring Perpetua and her baby would have been troubling for different reasons. In Roman aristocratic marriages, children were legally the property, first, of a woman’s husband, and thereafter, his male relatives.28 Perpetua’s husband is not mentioned in The Passion of Perpetua and Felicity – she may well be a widow – but from a Roman legal standpoint, a blueblood female criminal on house arrest and then in a prison would not retain care or feeding of her baby – that child would become the property of his or her father, or uncle, or grandfather.

The third major oddity with Perpetua’s story concerns her relationship with her father. He is a major character in the narrative, imploring her to recant, begging her to save the family, crying before her in a public forum, and at one point being so enraged that he physically attacks her. Their power dynamic is unusual in the cultural history of Rome. While a loving father might remonstrate with a Christian daughter to please just do what it took to stay alive, a father abasing himself before his incarcerated and disgraced daughter in public would have been highly unusual. The two characters are clearly close – in Perpetua’s version of events her father tells her “I have preferred you to all your brothers” (V.2), suggesting that she is indeed the apple of his eye. But in any case, the repeated trope of a weeping father pleading before his obstinate daughter sounds more like a scene from Greek tragedy than one depicting the hardnosed financial pragmatism that more broadly governed the familial relations of the Roman nobility.

Finally, there is the curious matter of the porous nature of Perpetua’s various imprisonments. Historians now know a fair bit about Roman prisons, which were intended as brief holding areas to cage the accused while sentences were being hammered out, rather than long term confinement facilities, like today’s penitentiaries.29 Evidence suggests that indeed families did bring food to those accused, as we see in The Passion of Perpetua and Felicity. However, there is also a lot of Christian activity going on in and around the prison, not the least of which is two deacons, named Tertius and Pomponius, visiting the prisoners to offer them spiritual counsel. If Christian conversion, and refusal by Christians to offer sacrifices to the emperor were indeed punishable by death in the city of Carthage in the spring of 203, it is exceedingly strange that Christian functionaries were being allowed in and out of the city lockup to do Christian stuff with prisoners.

Clearly, then, The Passion of Perpetua and Felicity, to some degree, is playing fast and loose with the facts. But the argument can also be made that the very strangeness of some of these facts might validate the document’s authenticity. In other words, if you were a Carthaginian Christian trying to create a streamlined martyr story in the year 205 or so, why on earth would you write about an aristocratic woman being executed like a slave? Why would you add unrealistic details, like her retaining possession of her infant after her being accused, or her having an unconventionally warm relationship with her pagan father? Why would you Frankenstein a document together, in which an unusually educated Roman woman is the primary narrator? The extremely idiosyncratic nature of The Passion of Perpetua and Felicity, then, might actually speak to the text’s credibility. As scholar Thomas Heffernan puts it, while it’s hard to take Perpetua’s story at face value altogether, the text we’ve read in this episode may indeed be “a document that preserved a memory of an actual event, an event which [has] surely changed through transmission but at whose core [is] a historically verifiable reality.”30 The oddness of this early martyr story, then, is one of the things that makes it interesting and juicy.

But there’s one more thing working against The Passion of Perpetua and Felicity being a careful record of a historical event. A big thing, and one which takes us to the second subject I wanted to cover in the closing portion of this program. Early Christianity was thrumming with energy, its basic doctrines blossoming in all sorts of worship communities like the house churches in and around Carthage. As this happened, though, naturally the religion evolved, mutating into radically different relatives like Gnosticism and Manichaeism, and closer cousins like Arianism and Priscillianism, countless subsets of the religion increasingly vilified after the consolidation of orthodoxy in the fourth century, but variants that, in their own time, flourished and accrued many adherents. As we move through the remainder of this and then the next few episodes, we will learn that the Christian genres of martyr story and hagiography, or saint’s life, are to some extent, timeless narratives that promote some of the core values of the New Testament. But we will also learn that individual works within these genres were written and engineered for specific historical junctures, and intended as contributions to contemporary theological debates. To use a familiar example, for Americans, at least, Arthur Miller’s play The Crucible, staged in 1953, was about a persecution that took place over 250 years before in Salem, Massachusetts. But this same play was written with an acute consciousness of the Red Scare and McCarthyism of the 1940s and 50s, that much maligned witch hunt for communism among American politicians that had all of the frothing fanaticism and idiocy of the events in Salem in 1692. In just the same fashion, Christian martyr stories and hagiographies, while they’re anchored in real historical events, also sidestep to engage with the contemporary controversies of their respective eras. This is the case with The Passion of Perpetua and Felicity, and will absolutely be the case with the Saint’s lives we’ll read in the next two programs.

To stick with The Passion of Perpetua and Felicity, this martyr tale, in its opening statements, stakes a position in a theological controversy endemic to the late second century. This was the so-called Montanist controversy. And while most surviving martyr stories and saint’s lives align themselves with beliefs that later became orthodox Catholicism, whoever wrote The Passion of Perpetua and Felicity seemed very friendly with beliefs that later theologians would revile as heretical. [music]

Montanism and The Passion of Perpetua and Felicity

The Passion of Perpetua and Felicity opens with a question, which, with some clauses snipped out, is as follows: “If ancient illustrations of faith. . .may be honoured. . .why should not new instances be also collected?” (I.1). A moment later, the text’s redactor writes, “[W]e. . .honor the new prophecies and new visions as well. . .lest any person. . .think that only the ancients received divine grace” (I.5). At first glance, these sentences seem there simply to serve as a prologue to Perpetua’s story, and tell us that new saints and martyrs are as valid as old ones. However, the text’s redactor explicitly uses the words “new prophecies,” words that in the beginning of the 200s referred to a theological movement called Montanism.Montanism, soon to be condemned as one of the heretical Christian sects, was alive and well in Carthage in the spring of 203, but it had begun decades earlier, in the mid to late second century – the 150s, 160s, and 170s. Montanism first appeared in west central Anatolia in the region historically called Phrygia, a rugged inland area whose remoteness kept it somewhat insulated from the homogenizing forces of Greek and Roman culture. Montanism’s founders were a prophet named Montanus and two of his female colleagues, Prisca and Maximilla. These three founders of Montanism claimed to be able to apprehend divine visions directly from the Holy Spirit. Let me read you a passage about this movement – a passage that comes from the church historian Eusebius, writing about 150 years after the Montanist movement began. Eusebius tells us that:

There is said to be a certain village called Ardabau in that part of Mysia, which borders upon Phrygia. There first, they say, when Gratus was proconsul of Asia, a recent convert, Montanus by name, through his unquenchable desire for leadership, gave the adversary opportunity against him. And he became beside himself, and being suddenly in a sort of frenzy and ecstasy, he raved, and began to babble and utter strange things, prophesying in a manner contrary to the constant custom of the Church handed down by tradition from the beginning. Some of those who heard his spurious utterances at that time were indignant, and they rebuked him as one that was possessed, and that was under the control of a demon, and was led by a deceitful spirit, and was distracting the multitude; and they forbade him to talk, remembering the distinction drawn by the Lord and his warning to guard watchfully against the coming of false prophets. . .But others imagining themselves possessed of the Holy Spirit and of a prophetic gift, were elated and not a little puffed up; and forgetting the distinction of the Lord.31

The basic idea of Montanism, then, was that latter-day Christians could be chosen to receive divine prophecy and speak with the authority of the Holy Spirit. Montanism also seems to have embraced women as vessels for prophetic message, giving them important leadership posts in congregations.32 In addition to claiming that their leaders could receive divine revelation, and allowing women into prominent positions, the Montanists were known for asceticism – they promoted new fasts and placed a special emphasis on chastity. The Christian prophet Montanus and his followers believed in an imminent second coming and corporeal resurrection as described in the Book of Revelation, spreading the prophecy that the New Jerusalem spoken of in the Bible’s last chapters would appear in between a pair of second century Phrygian villages.

Michaelangelo’s fresco of the prophet Isaiah on the Sistine Chapel cieling. Montanus and his followers believed that they had access to new prophecies and a direct connection with the divine. Their ideology, even by 160 or 170, was out of step with the proto-orthodox notion that bishops held church authority due to Apostolic Succession.

By the time The Passion of Perpetua and Felicity was written, the Carthaginian theologian Tertullian had, to some extent, embraced some of the main tenets of Montanism. Tertullian wrote, in a passage that bristles with Montanist ideas, “But yet Almighty God, in His most gracious providence, by pouring out His Spirit in these last days, upon all flesh, upon His servants and on His handmaidens, has checked these impostures of unbelief and perverseness, reanimated men’s faltering faith in the resurrection of the flesh, and cleared from all obscurity and equivocation the ancient Scriptures. . .by the clear light of their (sacred) words and meanings.”34 These are, again, Montanist ideas – Tertullian’s emphasis is that Christians of his own age can and should receive spiritual revelations, and that such revelations revived a purer and more genuine form of Christianity, with which would come a stronger intuition of the religion’s sacred writings. But while Tertullian responded to the movement open mindedly, many other Christian theologians saw it as a dangerous heresy.