Episode 96: The Last Pagan Epic

The last epic from Greco-Roman antiquity that survives in full, Nonnus’ fifth-century Dionysiaca tells of the wine god Dionysus’ journey eastward, to India.

| Read Transcription | References and Notes |

| Episode Quiz | |

| Episode on Spotify | Episode on Apple Podcasts |

| Previous Show | Next Show |

Nonnus’ Dionysiaca, Books 1-24

Gold Sponsors

Andy Olson

Bill Harris

Jeremy Hanks

John David Giese

ML Cohen

Silver Sponsors

Alexander Silver

Boaz Munro

Chad Nicholson

Francisco Vazquez

John Weretka

Lauris van Rijn

Michael Sanchez

Murilo César Ramos

Anonymous

Patrick Radowick

Steve Baldwin

Sponsors

A. Jessee Jiryu Davis

Anonymous

Aaron Burda

Alysoun Hodges

Amy Carlo

Angela Rebrec

Ariela Kilinsky

Benjamin Bartemes

Bob Tronson

Brian Conn

Caroline Winther Tørring

Chief Brody

Chloé Faulkner

Chris Brademeyer

Chris Guest

Chris Tanzola

David Macher

Earl Killian

Ellen Ivens

Ethan Arsht

EvasiveSpecies

Henry Bakker

Jason Barger

Joe Purden

John Barch

Joran Tibor

Joshua Edson

Kyle Pustola

Laura Ormsby

Laurent Callot

Leonie Hume

Mark Griggs

Mike Swanson

Mr. Jim

Oli Pate

Anonymous

Anonymous

Riley Bahre

Robert Baumgardner

Rod Sieg

Ruan & Nuraan

Ryan Walsh

De Sulis Minerva

Sonya Andrews

Steven Laden

Sue Nichols

Susan Angles

Tom Wilson

Valentina Tondato Da Ruos

Verónica Ruiz Badía

When we think about the first few decades of the 400s CE – if we think of these decades at all, Greek epic poetry isn’t the first thing that comes to mind. This period encompassed many of the great works of Saints Jerome and Augustine, and following the death of Saint Ambrose in 397, popes and bishops had successfully politicked their ways into Roman imperial courts. The first few decades of the 400s also encompassed the beginning of the western Empire’s death spiral, with Visigoths and Vandals in particular sweeping through the territories of Italy, Gaul, and later, North Africa. So when we think about these decades, we think of Jerome finishing the Vulgate, of Augustine writing the City of God, of Alaric the Visigoth sacking Rome, of Britannia and then Gaul slipping out of Roman control. We do not think about Homer, or Greek myths. We don’t think about these things, but Late Antique Greek poets still continued to.

Nonnus – our author for this and the next episode – was a Greek speaking Egyptian writer, based in a town called Panoplis. Panoplis was located in modern day Akhmim, Egypt, a city roughly halfway down the Egyptian Nile, seventy or so miles north of Luxor, where the river meanders eastward and westward and is lined by a belt of irrigated flatlands that’s over ten miles wide in places. Egypt, as the 400s opened, was and would continue to be a territory administrated by the eastern, or Byzantine Empire. And within the territories of both halves of the Roman Empire, over the 200s, the 300s, and 400s, Greek and Latin epic literature continued to be produced. Leading up to the poet Nonnus, we have records of numerous long works of mythology – Scopelianus’ Gigantius, Dionysius’ Bassarica, the works of Nestor of Laranda, Pisander of Laranda, Triphiodorus of Panoplis, Quintus of Smyrna, Soterichus, Claudian, and the Orphic Argonautica.3 Almost all of this late epic poetry has been lost, and, but as we open the front cover of Nonnus’ Dionysiaca in a few minutes, it will be important to remember that our poet for today wasn’t just some weirdo stubbornly clinging to Archaic and Classical Greek traditions, but instead part of a very old movement in literature that had continued uninterrupted for over a thousand years. In fact, rather than calling the Dionysiaca “the last pagan epic,” as this episode’s title has, it would be more appropriate to call the Dionysiaca “the last surviving pagan epic.” Around 500 CE, we know that another Greco-Egyptian writer named Coluthus composed epic works about the abduction of Helen of Troy and the legendary Calydonian Boar hunt. In essence then, during the 300s, 400s and perhaps even 500s, in Egypt and the Greek-speaking east, a literary culture around epic poetry continued to flourish. Nonnus, however, has the distinction of being the final poet of pagan antiquity to have left behind a major epic, and because of the vastness of the Dionysiaca, and the fact that in it, Nonnus isn’t simply revisiting the familiar opera of the Trojan War Cycle, he should by all means be included in literary history like ours.

Let’s talk about Nonnus for a moment. Scattered references tell us that Nonnus was from that town called Panoplis, along the central Egyptian Nile, but we know almost nothing about him besides this. From reading his works, it’s clear that he was exceptionally educated. While the Dionysiaca is Nonnus’ most famous work, Nonnus also wrote a paraphrase of the Gospel of John, something we’ll discuss at the close of the next episode, meaning that fascinatingly, Nonnus was as happy to retell Christian narratives as he was the old Greek myths.4 Having read both of Nonnus’ surviving works and some modern scholarship on them, I will tell you here at the outset of our shows on Nonnus that he was a person who loved details – obscure myths and alternate versions of myths, epic conventions and variations of those conventions. With a prodigious memory, and a knowledge of 1,200 years of Greek and Latin poetry that included an additional four centuries of material that Virgil and Ovid never read, Nonnus was well positioned to write one of the most ambitious works of literature that the ancient world ever produced. The Dionysiaca, as it survives today in a 3-volume, 1,500 page Loeb edition, will perhaps always be an obscure work, glittering with a galaxy of proper nouns, too long and complex for most armchair enthusiasts, and like so much of Late Antiquity, not especially well at home either in Classics or Medieval Studies departments. But our epic for today is also, in spite its occasional density and narrative meanderings, quite simply one of the most singular and unforgettable works in all literature. Love it, or hate it, once you read the Dionysiaca, you never, never forget it.

I want to get into the story pretty quickly in a moment here – as I said this is quite a long work, and even in just exploring the first half of the epic together in this first of two shows, we’ll be covering a lot of ground. Before we do that, though, I want to offer you some mythological background. Most of us know that Dionysus was the Greek god of wine – but he has a surprisingly long and complex back story that’s worth quickly reviewing before we jump into the Dionysiaca. [music]

The Many Dimensions of Dionyusus

Nonnus is not a concise writer. If he can think of anything to add in, he will add it in – variants of legends, lineages, embedded narratives, long speeches – the Dionysiaca is as much a mosaic as it is a single narrative, at once a Metamorphoses as well as an Aeneid. Still, the book’s main subject is one guy – the wine god Dionysus – the circumstances leading up to his birth, his infancy and childhood, his great quest to bring wine to the world, and eventually his ascendancy into the Olympian pantheon, so let’s spend a moment thinking about Dionysus. In past episodes, we’ve learned a bit about the complexity of Dionysus in ancient Greek mythology. Dionysus was certainly the wine god, the darling of numerous ancient Greek festivals and annual traditions, and much-loved fountainhead of alcohol and the positive things we still associate with it today – fun, togetherness and a temporary respite from worries and cares. But Dionysus had two other sides we should consider prior to moving forward.

Carvaggio’s Bacchus (c. 1598). European painters depicting Dionysus have generally depicted a gentle sommelier or cherub figure, rather than the horned and roaring wine god we often meet in ancient Greek poet.

While the amicable wine god Dionysus thus had quite a dark side, as well, there’s another thing about him we should get in our heads before beginning Nonnus’ Dionysiaca. This is that there were two different legends about Dionysus’ birth. In the first, Zeus raped his daughter slash niece Persephone to give birth to his son slash grandson slash nephew, who was called Dionysus Zagreus, or just Zagreus. The goddess Hera, by way of revenge for her husband’s infidelity, got a mob of titans to eat Dionysus Zagreus, after which Zagreus, in some versions, of the story seems to have been reincarnated, or humanity was made from his remnants.5 This first origin story of Dionysus was associated with a classical Greek religion called Orphism, a cult religion focused on the worship of Dionysus, sacred texts, mindful living and dietary restrictions, and various lost narratives that we have scraps in writers like Plato and Plutarch as well as grave goods from Macedonia and southern Italy attest to the worship of a primeval, lost Dionysus.6 Our poet for today Nonnus is familiar with this legend, and he puts it close to the outset of his epic.

There was another origin story of Dionysus as well, which Nonnus also recounts in the Dionysiaca. Dionysus was the patron deity of the city of Thebes, the mainland Greek town at the heart of Sophocles’ Oedipus cycle, and Euripides’ Bacchae, and Statius’ Thebaid. Thebes had a rich web of myths surrounding it, and at the outset of the Dionysiaca Nonnus tells us the story of Cadmus, the founder of Thebes. And the second origin story of Dionysus was that he was the grandson of Cadmus, founder of Thebes, born after Zeus tracked down Cadmus’ daughter Semele and raped her. After the rape of Semele, Zeus’ ever-jealous wife Hera tricked Semele into asking to see Zeus in his true form, and when Semele did this, Zeus appeared as a thunderous burning deity, Semele was incinerated, and Zeus had to carry the fetal Dionysus to term by sewing Dionysus up in his thigh. Weird, surely, but also a story we’ve heard before. Nonnus retells this second tale of Dionysus’ origins as well, as we’ll hear soon. So, to recap, the main point of all of this is that by the year 400 CE or so, anyone who wanted to write an epic about Dionysus had a lot of material to draw from – a god with multiple aspects, and multiple origin stories. When Nonnus sat down to write the Dionysiaca, he leveraged a lot of preexisting narratives – from literature that’s still extant, like Euripides’ The Bacchae and Ovid’s tales of the founding of Thebes, but also, from texts that we no longer have. Prior to Nonnus himself, a poet called Dionysius (and yes, his name was Dionysius) had already written an epic poem about Dionysus called the Bassarica around 200, and later, around 300, a poet called Soterichus had also written an epic about Dionysus, and so Nonnus was working comfortably within a very long tradition about a very complex deity.

With a good sense of the manifold nature of Dionysus out the outset here, I think there’s just one more thing we need to do before we actually begin reading the Dionysiaca. We need to talk about India in the poem – I should say “India” with quote marks. To repeat, a whole lot of Nonnus’ Dionysiaca is about a war between the forces of Dionysus, and those of India. This war begins, oddly, in western Anatolia, 2,700 miles northwest of present day India, and Dionysus advances eastward through Syria and Mesopotamia, fighting Indian forces along the way. To put it simply, to Nonnus, “India” seems to mean “people from the distant east who challenged Dionysus in the ancient mythological past.” When Nonnus was living and working, the Gupta Empire in India was flourishing, a generally prosperous and religiously tolerant empire that fostered the literary renaissance that canonized the Mahabharata and Ramayana. Nonnus doesn’t reveal any knowledge of this contemporary imperial Indian world, and he’s even sketchy on the geography of the Indus and Ganges rivers. He mentions Brahmins at one juncture, but he definitely believed that Indian people looked like sub-Saharan African people, and for whatever reason that they were allied with Ethiopians. We can get into Nonnus and India later – it’s always interesting to see how one culture writes about another culture that’s foreign to them – but for now it will suffice to say that when Nonnus describes India, he is envisioning a mythical culture from the legendary past, rather actual Indian folks from the 400s CE practicing Hinduism and Buddhism and writing Sanskrit texts. Generally, in the Dionysiaca, the Indians are just broadly distributed easterners.

So all of that should get us rolling as we turn to the first page of the longest surviving epic from Greco-Roman antiquity. There is still, to my knowledge as of late 2021, only one English translation of the Dionysiaca – this is again a massive poem and its range of subjects and vocabulary make it quite a task to translate – and the text I’m using is the W.H.D. Rouse translation in three volumes, published by Loeb in 1940. So here comes the first half of Nonnus’ Dionysiaca. [music]

The Dionysiaca, Book 1

Nonnus’ 48-book epic opens, as ancient epics tend to, with an invocation to the muse. Nonnus writes,Tell the tale, Goddess. . . the gasping travail which the thunderbolt brought with sparks for wedding-torches, the lightning in waiting upon Semele’s nuptials; tell the naissance of Bacchos twice-born, whom Zeus lifted still moist from the fire, a baby half-complete born without midwife; how with shrinking hands he cut the incision in his thigh and carried [Bacchos] in his man’s womb, father and gracious mother at once. (1.1-9)7

The reference here, as you can see from what we discussed earlier, is to the birth of Dionysus, or Bacchus, salvaged from the burning remains of his human mother Semele, and carried to term in Zeus’ thigh. Nonnus asks not only for help from the muses in general, but also from the god Proteus, or as Nonnus puts it, “Proteus of many turns, that he may appear in all his diversity of shapes, since I twang my harp to a diversity of songs” (1.14-15). The epic, Nonnus acknowledges here, will be an enormous one, and will require some shape shifting on his part as a narrator. Asking for help with the many different parts of the epic to come, Nonnus begins his epic in the ancient past, some time before Dionysus ever came along.

Europa with Zeus in bull form, from a red-figure stamnos done around 480 BCE. Her story lies at the outset of the Dionysiaca.

By this point, Europa’s brother Cadmus had already gone after her, trekking overland through Anatolia, where he found a passage called the cave of Armia. Armia, according to legend, was where the great primordial monster Typhoios lived. And Typhoios, at this juncture of early history in the Greek myths, had stolen Zeus’ thunder and other powers. The creature was stomping and marauding all over the world, and smashing constellations into the earth and sea. Gods and demigods fought back against the raging titan, as the monster switched from attacking the starry skies to smashing at the ocean, which didn’t even reach his thighs. Typhoios then reached down and picked up an island with one enormous hand, and he flung it up toward Olympus.

Zeus, in response, fortified himself with his trademark thunderbolt. But high overhead, where the massive torso of Typhoios loomed above, there were no clouds, and Zeus’ weapon was powerless. Zeus, however, had a plan. First, he had sex with the girl Europa, eliciting an angry monologue from the ever-jealous Hera. And yes, the chronology here is weird – as to why Nonnus decided to juxtapose the Europa riding Zeus as a quadruped story and then the rape of Europa with the cataclysmic ravages of Typhoios in a literally overlapping timeframe, I am not sure. But anyway, Zeus raped Europa and then put his pants on and prepared to deal with the mile-high giant currently threatening Mount Olympus by throwing whole islands at it.

The plan to avert the end of the world involved young Cadmus himself. Cadmus, brother of the girl Zeus had just raped and future founder of the city of Thebes, was instructed by Zeus to dress up like a shepherd and play pipes for the giant monster Typhoios. Cadmus, Zeus said, would be rewarded with a glorious marriage and kingship. Cadmus agreed. Cadmus played his pipes, and Typhoios wandered out of a cave in which he’d been staying, leaving Zeus’ weaponry behind. Typoios loved what he heard, and he promised Cadmus great rewards as well if Cadmus would be the titan’s minstrel. Cadmus pretended to agree, and Cadmus asked giant Typhoios for Zeus’ special weaponry back as a guarantee. The monster Typhoios, being truly bewitched by Cadmus’ musicianship, surrendered the armaments of Zeus, evidently having more brawn than brains. [music]

The Dionysiaca, Book 2

Cadmus continued to play music a short while longer for the titan Typhoios, but soon Zeus, cloaked and unseen, retrieved his weapons, and then caused Cadmus to become invisible. Typhoios erupted into rage. He found that the divine weapons he had taken from Zeus were now missing from their hiding place, and vented his anger on the world, devouring animals and smashing the ground so hard that geysers of water burst upward from the earth’s crust. Various spirits and demigods were at a loss as to what to do – a dryad, or tree spirit, considered her options.

Zeus (left) aims a thunderbolt at Typhoios in this black-figured hydria, circa the 530s BCE. The fight occurs toward the outset of the Dionysiaca.

The battle between Typhois and Zeus began, rattling trees in half and shaking not only the four corners of the known world, but also the universe far beyond. Zeus wielded lighting and thunder, and Typhoios seized armfuls of water from winter rivers to cool the blazes. High overhead, the warring pair hurled crags and promontories of land at one another, and for a long time they appeared evenly matched, even with Zeus having regained his lightning. Soon, though, Zeus began to have the upper hand, the persistence of his white-hot lightning scorching the snakes atop Typhoios’ heads, and then the great titan’s eyes, then his hands, then his shoulders. Whirling winds and blasting bolts scoured the monster’s skin with hail and flecks of flying stone. At last, Typhoios crumpled down, limp, to the earth with a giant boom, and Zeus stood over his fallen enemy and mocked the dying titan.

Slowly, order returned to the earth, and it healed, nature sealing rifts and chasms in the earth, and the stars twinkling back into alignment. And Zeus, vaunted by all, did not forget his promise to Cadmus. He told Cadmus that Cadmus’ brothers would all go on to have honorable fates – as for Cadmus’ sister Europa, she would be a queen on the island of Crete. Cadmus himself would marry a woman named Harmonia, and, bringing us a few steps closer to the story of Dionysus, Cadmus would soon found the city of Thebes.[music]

The Dionysiaca, Book 3

Triumphant after successfully helping Zeus best Typhoios, Cadmus disembarked from Anatolia. Nonnus’ narration of the voyaging ship here is lovely in the Loeb Rouse translation:The intertwined ropes whistled with a shrill hiss, the forestays hummed in the freshening wind, the sail grew big-bellied, enforced by the forthright gale. The restless flood was cleft, then fell back to its place; the water swelled and foamed, the ship sped over the deep, while the keep struck the boisterous waves with a resounding splash, and the end of the steering-oar scored the white-crested billows where the ship’s wake divided the curving back of the sea. (III.23-30)

After ten days out, Cadmus and his crew reached the island of Samothrace in the northeastern Aegean. The crew, tired after the voyage, settled in to sleep, and in the morning, they were awakened by a group of Corybants – or ritual worshippers of the goddess Cybele.9 Cadmus made his way through the noisy din of the new arrivals – the dancing and tamed animals and crowds of worshippers, to find the house of Harmonia, the woman he was to marry. Not a romantically experienced person, Cadmus made his way shyly through the house of Harmonia’s mother, the goddess Electra, not to be confused with Agamemnon’s daughter Electra in The Libation Bearers. The goddess Electra’s house on the island of Samothrace was lovely and profuse with interwoven plants, shady gardens, golden statues, figs, pomegranates, myrtles and laurels. Cadmus, intimidated, accepted Electra’s invitation to feast. Cadmus had been told by Zeus that he would marry Electra’s daughter Harmonia, but it seemed that the onus of impressing his future in-laws was still Cadmus’ to bear.

Over dinner, then, Cadmus told Electra and her household his origin story. Curiously omitting the part about how, just eleven or so days ago, he had helped Zeus himself save the universe from the cataclysmic ravages of Typhoios, Cadmus went into some detail about his lineage, and said he was just outbound, searching for his sister, who’d been kidnapped by a swimming bull. Electra replied that she, too, had been bandied about by fate, and that that was how things went sometimes, but that Cadmus should feel free to make a home for himself in a new land, as his father had once done before him.

As it turned out, Zeus did have a plan to help Cadmus woo Harmonia, after all. Zeus sent Hermes to tell Harmonia’s mother Electra to allow Harmonia to marry Cadmus. Cadmus, said Hermes, wasn’t just some wandering nobody from the Phoenician coast. He had saved the world with his music, Hermes explained, and the gods, and Zeus himself.

The Dionysiaca, Book 4

Evelyn De Morgan’s Cadmus and Harmonia (1877). In some versions of the founding of Thebes story, Harmonia is attacked by the dragon that lives there, and Cadmus rescues her. In the Dionysiaca, Nonnus deals with the dragon and dragon’s teeth story fairly quickly.

The goddess Aphrodite, at this juncture, intervened. She disguised herself as a local Samothracian girl, and as a Samothracian girl from the neighborhood, she pretended to be absolutely smitten by young Cadmus. She sung all sorts of praises for Cadmus, comparing him to Apollo and saying that the young man was as good as pure gold. Cadmus, the disguised Aphrodite said, was better than any divine husband. Pulling out all the stops, the disguised Aphrodite envisioned all of the steamy things she’d like to do to young Cadmus, and have young Cadmus do to her. Aphrodite even ventured to say that if Harmonia decided to marry Cadmus, then Aphrodite – or the local girl Aphrodite was disguised as – would demand at least one night of passion with the handsome easterner.

Hearing all of this, then, Harmonia, conflicted, upset, and suddenly very horny, began to change her mind about Cadmus. She would marry him after all. And she would go wherever it was that her future husband was headed. Not long after, she told her mother the same thing. And so it was that the previously reluctant Harmonia kissed her native soil of Samothrace farewell, and was soon seated beside Cadmus in his vessel, westward bound to the Greek mainland among various other travelers who’d tagged along for the voyage. When the betrothed couple arrived on the mainland, they went to Delphi, to see the oracle of Apollo. And the oracle had advice for Cadmus. Give up the chase after Europa, the oracle said. It was time for Cadmus to move on with his new wife, and to found a city – a city named Thebes like the one along the Egyptian Nile, only a Thebes in mainland Greece.

So Cadmus and Harmonia, together with a band of those loyal to them, came eastward down out of the mountains to the future site of Thebes. Thebes, though, was home to a ferocious dragon, and this dragon killed some of their entourage. Soon, it wound itself around Cadmus, but before it could eat the hero, Athena appeared and offered him heartening instructions and council. Cadmus, afterward, smashed the dragon’s head with a stone and cut its throat, and, abiding by Athena’s instructions, he tore its teeth out and planted them. Giants appeared, and Cadmus fought them off, in the end compelling them to fight and destroy one another. And that story, built with many prefabricated elements from Homer, Ovid, and Apollonius of Rhodes, together with some of Nonnus’ own touches, is the story of how the ground was cleared for the foundation of Thebes, which would later be the city of Oedipus, Antigone, Creon, Polynices, and Eteocles, and soon in Nonnus’ epic, the city of Dionysus. [music]

The Dionysiaca, Book 5

Now, Cadmus, as you may know, was the maternal grandfather of Dionysus, and the next part of the Dionysiaca deals with how Dionysus’ parents’ generation came about. It all began with the actual founding of Thebes, instantiated with a public animal sacrifice performed by Cadmus himself. Cadmus fought some territorial wars, and then the foundations were laid for Thebes, the city’s famous seven gates a part of its initial design. With all of this taken care of, it was finally time for Cadmus and Harmonia’s wedding. Plenty of illustrious divine guests were in attendance, and the music and festivities were second to none. With the union being ordained and blessed by Zeus himself, the couple received some fine gifts from the gods, including an elaborately described necklace with two intertwined serpents, given by Aphrodite to Harmonia. And at this point, the narrative picks up in speed a bit more.Cadmus and Harmonia had five kids – four daughters and one son, and these five kids dominate the next five books of the Dionysiaca. The four daughters, from oldest to youngest, were Autonoë, Ino, Agauë, and Semele, and the youngest of the lot was the boy – Polydorus. With the five kids having come of age, Cadmus soon took it on himself to make sure they wound up in advantageous marriages. His oldest daughter Autonoë married a man named Aristaios, known for pioneering various arts associated with the wilderness and cultivation. Autonoë and Aristaios were the parents of Actaion, Cadmus’ firstborn grandson. But Actaion, as fans of the Greek myths know, came to an awful end. Out hunting, Actaion saw the nude Artemis and her virginal huntress companions bathing. As punishment, Artemis transformed Actaion into a young stag, and afterward Actaion was ripped to bloody shreds by his own hunting hounds. When the Theban royal family heard about it, the tragedy rocked the royal household, and when the poor boy’s mother went to find him, she never found a human body. Actaion, however, came to his father in a dream and explained what had happened, and following this, the dead boy’s parents were able to find the remains of the young stag into which he’d been transformed. That, then, is the story of Cadmus’ firstborn daughter Autonoë, her husband Aristaios, and their poor son Actaion.

Cadmus and Harmonia’s third eldest daughter was Agauë, and with her husband, she became the mother of Pentheus, a future king of Thebes and important figure much later in the epic we’re reading – Pentheus and his mother Agauë are also the central characters in Euripides’ play The Bacchae. Cadmus and Harmonia’s youngest daughter was Semele, a young lady with stunning beauty, and one destined, as we’ll soon see, to be the victim of Zeus and mother of Dionysus. Now we haven’t actually been through the full catalog of Cadmus and Harmonia’s kids yet – we’ve skipped the second eldest, Ino, and then the very youngest – the son, Polydorus. But at this point in the narrative, Nonnus dives into the ancient history of the Orphic Dionysus – that second and primeval Dionysus I mentioned at this episode’s outset – a fascinating little saga, if you haven’t heard it before. To be very clear, because this is confusing, once again Dionysus had two different birth stories in antiquity, and Nonnus is going to offer both of them to us, starting with the lesser-known tale of Dionysus Zagreus. In Nonnus’ poem, Dionysus Zagreus is an ancient ancestor of the main Dionysus who is the star of the epic, a sort of Dionysus version 1.0.

Nonnus begins the dark story of Dionysus Zagreus by telling us that when Zeus saw the beautiful Semele, youngest daughter of Cadmus and Harmonia, “Zeus ruling on high intended to make a new Dionysos grow up, a. . .copy of the older Dionysos; since he thought with regret of the illfated Zagreus” (5.563-5). And the story of Zagreus, which Nonnus now offers as Book 6 of the epic in a flashback sequence, all started with the goddess Persephone.

The Dionysiaca, Book 6

Frederic Leighton’s The Return of Persephone (1891). Persephone is the mother of Zagreus in the Dionysiaca and elsewhere. A central figure in the Eleusinian Mysteries and one very common in vase paintings, Persephone was one of most important figures in ancient Greek religion.

But none of these evasive maneuvers deterred Zeus, lord of the unstoppable quote unquote thunderbolt. Zeus disguised himself as a dragon, and in dragon form, he raped the hidden Persephone. The result of their union was the elder Dionysus – as Nonnus describes, “Zagreus the horned baby, who by himself climbed upon the heavenly throne of Zeus and brandished lightning in his little hand, and newly born, lifted and carried thunderbolts in his tender fingers” (6.165-8). This is a memorable little description, as Zeus sires countless illegitimate children in the Greek myths, but we never really hear of a Zeus junior, wielding lightning just like his father.

To continue this flashback sequence, young Dionysus Zagreus was not fated for a long and happy life. Zeus’ wife Hera, ever severe in her revenge against her husband’s manifold infidelities, could not countenance baby Dionysus Zagreus waddling around. She summoned titans, who disguised themselves and then attacked the baby deity with knives. In the short struggle that followed, Zagreus took many shapes – Zeus himself, then the titan Kronos, then a downy-faced youth, then a lion, a horned snake, then a tiger, and then a bull, but in the end the titans were too strong, and little Zagreus was chopped to pieces.

Zeus was intensely angry. Persephone hadn’t just been a weekly fling – he had been drawn toward her, and their son’s death was awful to him. He scorched the offending titans and slammed them in prison of Tartarus, and scoured lands to the distant east and west with fire. The ocean itself was dismayed by the great heat, and so Zeus made it rain instead, thinking to souse the blazes and wash away the ashes all caused by his wrath. It rained and rained, and the oceans and lakes rose and rose, such that fish swam through mountains and dolphins looked into the eyes of alpine boars. Soon there was hardly any land left at all, and the sun’s chariot carried only a faint fire as it swung through the sky. Before the whole earth was consumed and destroyed by the water, though, Poseidon smashed a crack down through the earth, and water rushed down into the emptiness below it, allowing the seas to resume their former level. The sun then dried out the lands, and humans came into their former dominions, making their cities stronger and more soundly built than before. And that concludes Nonnus’ flashback story about the elder Dionysus – Dionysus Zagreus. [music]

The Dionysiaca, Book 7

The timeframe of the Dionysiaca now flashes forward once more to the present – Typhoios has been defeated, the city of Thebes has been founded, and Cadmus and Harmonia have had a crop of children. But, Nonnus tells us, all was still not well. The poet writes that:sorrow in many forms possessed the life of men, which begins with labour and never sees the end of care: and Time his everlasting companion showed to Zeus Almighty mankind, afflicted with suffering and having no portion in happiness of heart. For the father had not yet cut the threads of childbirth. . .to give mankind rest from their tribulations; not yet did the libation of wine soak the pathways of the air and make them drunken with sweetsmelling exaltations. (7.7-14)

The meaning of that passage is that Zeus’ beloved son Zagreus, the subject of the previous book, has not yet been resurrected. The opening of Book 7, here, though, sounds faintly Christian – we have a fallen world, due to an as-yet unborn divine son, and as we move forward we’ll talk a bit more about Nonnus and Christianity. For now, let’s move forward with the epic, which takes us to the subject of Dionysus’ birth – or second birth – in Thebes.

Zeus spoke with Aion, the deity of time, and Zeus resolved to make everything better in the world through the rebirth of Dionysus and the gift of wine to humanity. As the epic has indicated thus far, and Nonnus’ original audience would have known, the mother-to-be of Dionysus was Semele, the beautiful youngest daughter of King Cadmus and Queen Harmonia of Thebes. Semele, one day, was out walking and witnessed strange signs – a tree consumed by pure fire. She made sacrifices to appease Zeus, and later, while she was washing the sacrificial blood away on an altar, nude alongside her attendants, Zeus caught sight of her. And at just that moment, he was hit by an arrow from Eros, intensifying his desire. He flew down to the river in which she bathed, leering at her naked body, and a water nymph recognized the voyeuristic deity, though Semele did not see him. Zeus planned to rape Semele. Night fell, and a long and sickening sex scene proceeds in which Zeus transformed into various creatures while he violated the princess, at one point winding around her breasts as a snake and licking her neck. As the rape took place vines and flowers blossomed around the Theban princess’ bed. Afterward, Zeus congratulated her on being raped by a god, telling her that while her sisters and her sisters’ children would fade into obscurity, the child that they had just conceived would give an eternal gift to humanity. [music]

The Dionysiaca, Book 8

Sebastian Ricci’s Jupiter and Semele (c. 1695). One of the Dionysiaca‘s numerous rape stories, this juncture of the epic chronicles its main character’s actual birth, after having told the tale of Zagreus’ birth.

In disguise, then, Hera went to speak with Semele, and Hera told Semele that of course, everyone was talking about the Theban princess’ mysterious pregnancy. Hera asked Semele – had it been Ares, or Hermes, or Apollo? Had it been Poseidon? If it had been Zeus, said Hera, then indeed Semele had been triumphant – there was just one more thing to do to cement Semele’s triumph, and that was for Semele to see Zeus in his true form, armed with lightning, just as Hera herself did. Rather than saying, “Thanks, mysterious old nursemaid woman, now get the hell out of my bedroom please,” Semele took these words to heart. After Hera left, Semele wondered if Zeus even still had his thunder – he had recently lost it during the incident with Typhoios. Semele became fixated on the issue – she wanted to see Zeus in his true, thunderous form, and thus be an amorous equal to Hera. When Semele and Zeus met once again, Semele told Zeus that she wanted to see him armed with his thunders. Zeus conceded, and lightning exploded all over Semele’s room, burning her to ash, but not harming the fetus that was Dionysus. The ill-fated Theban princess ascended to be with the gods on Mount Olympus, and as for Dionysus, the next book of the epic tells us of the fate of the unborn deity. [music]

The Dionysiaca, Book 9

In one of the weirder episodes of Greek mythology – not unique to Nonnus’ Dionysiaca, by the way – Zeus lifted the unharmed fetus of Dionysus from the charred remains of his mother, cut an incision into his own thigh, and inserted the fetal god into his own thigh. After this, he sewed Dionysus up, and carried the youngster to term. When the time came, Zeus cut the stitches from his thigh, and Dionysus had a third birth – the first being his arrival as Dionysus Zagreus, the second his emergence from his burnt mother Semele, and the third, from the thigh-womb of Zeus, hence the fact that one of Dionysus’ epithets is thus “thrice-born Dionysus.”The baby, just as Zagreus had been, was born with horns, and upon his birth the seasons crowned him with an ivy circlet. In a lovely little description, Nonnus tells us that as an infant, “the boy lay on his back unsleeping, and fixt his eye on the heaven above, or kicked at the air with his two feet one after another in delight; he stared at the unfamiliar sky, and laughed in wonder to see his father’s vault of stars” (9.35-6). As cute as he was, though, Dionysus still had vengeful Hera after him, and so he was taken to be raised by his aunt Ino (this was Semele’s second eldest sister, at that point married and conveniently already nursing a baby). Aunt Ino and her handmaiden together raised the baby Dionysus, having been told to keep him carefully out of sight. But as hard as they tired, the baby wine god exuded a divine light, and the goddess Hera, looking everywhere for her husband’s latest illegitimate child, saw this light, and came after him. Dionysus’ brother Hermes came to the rescue, spiriting the baby away, and through subterfuge and speed, Hermes and the baby Dionysus escaped from Hera, until Dionysus was in the care of his grandmother, Rhea.

Rhea was a titan, and one of the oldest and most powerful figures in Greek mythology, and so she proved to be a sturdier guardian than either Dionysus’ aunt Ino, or his half-brother Hermes. Little Dionysus was thereafter raised in the territories of the Anatolian goddess Cybele, surrounded by her wild and ecstatic dancers, and given a chariot of lions to drive. At nine years old, Dionysus was already hunting in the mountains, and as his teenage years passed, the wine god became the tamer and frequent companion of wild beasts in the wilderness of the Aegean’s eastern shore.

Up in the heavens, seeing Dionysus’ healthy, happy teenage years, Semele – now a goddess herself – taunted Hera. Hera, Semele said, hadn’t been able to prevent what had happened – Semele had birthed a powerful and a beloved god. Needless to say, the taunts didn’t make Hera any happier. Dionysus might be out of reach, but his aunt Ino, who had briefly nursed the baby – Hera could still go after her. Hera did so, and Ino fled, and she vanished. To make her plight even sadder, her husband Athamas decided to marry a new wife. And at this point, the poet Nonnus launches into a nearly book length story about the ex-husband of Dionysus’ aunt Ino, because, you know, if you’re going to write the longest Greek epic ever, you don’t want to leave anything out. [music]

The Dionysiaca, Book 10

The central subject of this book of the Dionysiaca is Dionysus’ aunt Ino, so let’s get her in our minds. Around the time Dionysus was a teenager, Ino fled the persecutions of Hera. Meanwhile, once again, Ino’s husband remarried. But in mutual fits of madness, Ino’s husband Athamas and his new wife became great threats to their children. One wonders where old, reasonably sensible King Cadmus was as all of this went down, but anyway, when Ino returned home four years later, she discovered that her husband Athamas had remarried and that he and his new wife were in the midst of taking up child murder as a pastime. Athamas’ new wife, thinking in her madness to murder her stepchildren, inadvertently killed her own children from a previous marriage. As for Athamas, he killed his and Ino’s son Learchus, he was about to cook his and Ino’s second son Melicretes in a cauldron, but, arriving just in the nick of time, Ino saved her second son, diving into the ocean while pursued and praying for solace. The ocean gods granted poor Ino’s wishes, and Ino was able to continue on as a sea nymph, along with her surviving son. Weirdly, Ino’s sister Semele, now installed in heaven as a goddess, insulted the recently departed Ino, saying that Ino’s dominion was the ocean, but that Semele dwelt in the heavens above. Strange words, considering that Semele’s sister Ino had taken in Semele’s baby son Dionysus in his hour of need, and that it was for this crime that poor Ino had lost her home and family.Anyway, at this point in the epic we’re finally going to rattle out of the bloated 10-book long exposition and Theban palace drama, and begin concertedly focusing on the star of the show, Dionysus. Dionysus, at this point, was still living out in the sticks of Anatolia. He grew tall and handsome, and bathed in fresh river water, and he fell in love with a satyr named Ampelos, whose name means “vine.” Dionysus thought of Ampelos day and night, dreamt of him, and worried that the satyr would somehow be taken from him. While the tale of Dionysus and the satyr Ampelos is certainly a love story about one of Dionysus’ early affairs, Ampelos’ name, associating him with wine, also makes the episode a narrative about Dionysus’ awakening love of wine. Dionysus exclaims, “If I can have [Ampelos] to play with me. . .I wish not to be translated into the sky, I would not be a god. . .I want no ambrosia! I care nothing, if Ampelos loves me, even if [Zeus] hates me!” (10.282-7). On one hand these are the words of a lovestruck young person, and on the other, words of devotion toward earthly wine over heavenly ambrosia and deification.

In a prayer to Zeus, Dionysus said Ampelos was lovelier than Zeus’ male lover Ganymede, and Dionysus prayed that he might simply be left on earth to be with the satyr. And so their romance blossomed. Dionysus wrestled with Ampelos in the shallows of a warm river, Nonnus describing their loving horseplay in some truly beautiful lines (10.339-72). The young pair also enjoyed footraces, competing in athletic games among the horned and shaggy satyrs of the forest, Dionysus occasionally using his divine powers to aid his young lover in the contests. [music]

The Dionysiaca, Book 11

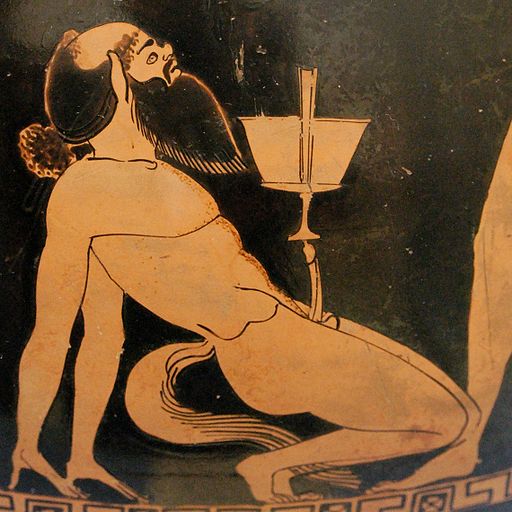

A satyr balances a wine cup on his penis in this red-figured psykter, done around the 490s BCE. Satyrs are everywhere in the Dionysiaca.

Soon enough, the frightening prophetic vision began to come true. A goddess, sent by Hera, met with Ampelos as Ampelos wandered through the woods. The goddess told Dionysus’ lover Ampelos that there was something Ampelos could do that would truly impress Dionysus and win his favor even further – Ampelos could ride a wild bull! On cue, a wild bull appeared, a magnificent creature drinking water from a stream. Excited and obviously gullible, the satyr Ampelos first made himself a goad from some nearby plants and then bedecked the bull with leaves and rushes, roses and daffodils. Then, tossing a spotted skin onto the bull’s back, he jumped astride the creature. But things took a turn for the worse. In a moment of braggadocio, Ampelos said that he was a horned satyr on top of a horned bull, and asked who could beat this. The moon goddess – and in Greek mythology the crescent moon is often said to have horns – the moon goddess became irritated at this claim, and sent a gadfly to bother Ampelos’ bull. The wild bull dashed ahead, and Ampelos realized he was doomed, begging the bull to stop and hoping that Dionysus would lament his passing. Soon, atop nearby mountains, the bull bucked, and Ampelos flew off, breaking his neck and only moments later being gored by the animal’s hooves and horns.

Another satyr found the tangled remains and brought word to Dionysus. Dionysus draped a fawn skin over his lover’s body, along with fresh flowers. He put a thyrsus staff – that pinecone-topped, ivy-woven staff which was the emblem of Dionysus in the Greek world – Dionysus put a thyrsus staff in Ampelos’ hand, lamented extensively, and vowed to avenge his death. Dionysus wished that he had not been born a god, so that he could follow his love to Hades, and then his thoughts turned once more darkly to revenge. But the satyr Silenus came and offered the bereaved Dionysus a story – a tale about two other male lovers. These were Carpos and Calamos – in a swimming competition, Carpos drowned, and in his lamentation, Calamos drowned himself and then turned into a bank of reeds, reeds which sung their requiem whenever breezes passed along the shoreline. The tale certainly didn’t cure Dionysus of his grief, but after it was told, the autumn winds carried the season’s passing to the house of the sun god Helios, and for the first time, something new in the world began. [music]

The Dionysiaca, Book 12

As Dionysus mourned Ampelos, deities converged in the house of Helios to determine how the first wine would be made, and who would be involved. Consulting ancient oracles, the council saw a prophecy that just as corn and grain would be the dominion of the goddess Demeter, wine would be that of Dionysus. A goddess went to tell Dionysus just this.The wine god – or very-soon-to-be wine god – was at this juncture still lamenting his dead lover Ampelos. The messenger goddess told Dionysus not to be sad, for Ampelos, whose name once again means “vine,” had great things in store for him. Ampelos, she said, would prompt Dionysus to crown himself with vines, and afterward, to “dispense a drink, the earthly image of heavenly nectar, the comfort of the human race” (12.157-9), because this drink would soon be a delight to every corner of the world. And it was then that Ampelos transformed. He lengthened, his body planting itself, his limbs elongating, and everywhere, vines and runners and grapes of every hue burst out of him. This was only the beginning, though, as a whole vineyard followed, stretching as far as the eye could see. Dionysus crushed some of the new grapes into a drinking horn and savored the thick mixture, proclaiming it on par with heavenly ambrosia. Under the effects of the drink, Dionysus quickly proclaimed that his gift to humanity was better than Demeter’s grain, because wine made people savor foods at the table and lose themselves in dancing.

Under ecstatic inspiration, Dionysus changed his thyrsus staff into a sickle and harvested bunches of grapes, placing them into a hole in the ground – a makeshift wine press. Then, Dionysus and his satyr friends danced all over the pulpy masses of grapes, dipping their drinking horns down into the resulting mixture. Some form of instantaneous fermentation had taken place, because the satyrs quickly began showing signs of inebriation – one or two stumbling, and one or two suddenly chasing after water nymphs and nearby women. As for Dionysus, he gloatingly entered the cave of his grandmother Rhea, showing her the miraculous new creation of wine. Unlike all of the staggering satyrs, Dionysus was protected from inebriety, because his grandmother Rhea had given him an amethyst crystal – the Greek word αμέθυστος coming from the roots α, or “not” and μεθύσκω, or “intoxicate” – amethyst in the ancient world was a talisman designed to prevent drunkenness. I’ve tried that, by the way – wearing amethyst to prevent drunkenness. Totally works. Totally [hiccup] works. [music]

The Dionysiaca, Book 13

At this point – a quarter of the way through the Dionysiaca, by the way, the long epic’s exposition concludes and its rising action begins in earnest. Book 13 opens with the following words:Father Zeus sent [the messenger goddess] Iris to the divine halls of Rheia, to inform. . .Dionysos, that he must drive out of Asia with his avenging thyrsus the proud race of Indians untaught of justice: he was to sweep from the sea the horned son of a river, Deriades the king, and teach all nations the sacred dances of the vigil and the purple fruit of vintage. (8.1-6)

Zeus, in other words, wanted Dionysus to lead a military campaign into India, to teach the Indians and their king about sacred Greek rites as well as wine. While I’m not convinced that a military campaign is strictly necessary to share cultural rituals and certainly not to introduce people to alcohol, which is quite a self-explanatory substance, Dionysus’ great eastward mission through Anatolia, Syria, Mesopotamia, Central Asia, and down into the western part of the subcontinent is hereafter the main subject of the remainder of the epic.

Once the news of Dionysus’ looming campaign was delivered to the young god and his grandmother Rhea, Rhea and her lieutenants began gathering an army for Dionysus. The troops hailed from all over. There were satyrs and centaurs. Troops came from all over Boeotia, from Phocis and the territories around Delphi, Euboea, Crete, Attica and the islands of the Saronic Gulf, Arcadia, Sicily, Libya, Samothrace, Cyprus, Lydia, Phrygia, and more. In epic tradition, following Book 2 of Homer’s Iliad, there is a convention called “the gathering of armies,” in which the epic poet enumerates a list of heroes and their forces hailing from all over the place. To the modern reader, such catalogs are bewildering – the 13th book of the Dionysiaca assaults us with hundreds of proper nouns involving places, heroes, and heroic lineages. In the Iliad, at least, the Homeric Catalog of Ships in Book 2 of the Iliad gives us a sense of Archaic Greece’s conception of geography – modern scholars study the Homeric catalog of ships to understand what ancient Greeks knew about the world around 700 BCE. However, 1,200 years or so later, Nonnus’ catalog of Dionysus’ armies in Book 13 of the Dionysiaca is an odd anachronism – a faux-antique catalog of archaic Greek heroes, seeded with ancient names and places stemming more from thousand-year-old poetic traditions than the geographical knowledge of Nonnus’ contemporary Byzantine world. [music]

The Dionysiaca, Book 14

Now that Rhea had marshaled troops to fight for Dionysus – troops from all over the Aegean and western parts of Anatolia, she moved on to her next task. It wasn’t just human heroes who would fight on behalf of Dionysus – Dionysus also needed semi divine forces. These powerful auxiliaries included creatures from the ocean, cave dwellers, cyclopes, powerful satyrs and horned centaurs – side note, Nonnus seems to really love centaurs, as his catalog of them is extensive. Anyway, continuing on the powerful non-human forces Rhea gathered for her grandson Dionysus, there were also powerful forest dwelling beings shagged over with ivy and snakes, and a general to lead them – a creature called Eiraphiotes, armed only with a thyrsus, mug of wine, and a crown of leaves.

A fresco of the centaur Chiron offering instruction to the young Achilles in a first century Roman fresco from Herculaneum. Centaurs, a frequent fixture of visual art featuring Dionysus, are everywhere in the Dionysiaca.

To continue with the plot of the Dionysiaca, every epic needs a divine antagonist. The goddess Hera, for the tangential reason that Dionysus was the offspring of her husband Zeus’ four hundred thousandth rape, decided that as much general revenge killing as possible was in order, and she stirred up the Indian forces against those of Dionysus. Specifically, Hera spurred on a powerful Indian leader named Aristaëis, an important Indian leader in the early part of this epic.

The Indian leader Aristaëis thus rallied his forces against those of Dionysus on the shore of a lake called Lake Astacid, putting his army into a defensive formation and awaiting the wine god’s attack. An important part of Dionysus’ forces were his Maenads – in ancient Greek culture a group understood as female celebrants of Dionysus whose ecstatic bouts of drunken revelry often descended into violence and the eating of raw flesh. These warriors spearheaded the first confrontation between Dionysus’ army and the army of the east, and Dionysus’ army dominated the enemy forces. The sound of the syrinx, or pan flute, rang over the battlefield and the blood of Dionysus’ enemies coursed into the nearby lake.

Dionysus, perhaps not a warrior in the core of his being, felt sorry for his massacred enemies, and so he changed Lake Astacid into wine. An Indian aristocrat who had survived the initial battle drank deeply from the lake, and he raved about the sensations that he was experiencing as a result. It was the first step in Dionysus’ long, weird quest to get the eastern world drunk through a violent military campaign. [music]

The Dionysiaca, Book 15

Curious about the wine in the lake, Indians ringed around the waterway and all tried it. Collectively, they became inebriated, some simply falling asleep, and other becoming so confused that they thought local animals were the forces of Dionysus, and variously attacked cattle and goats. Some of the drunken easterners picked olives, while others danced, and still others unsuccessfully tried to rape a stray Maenad. But gradually, sleep overtook more and more of them, until, staring out over the drunken stupor of his enemies, Dionysus laughed. He told his forces to tie up the enemy forces, and soon the whole enemy army was bound and defenseless.And at this point in the narrative, a new character is introduced – one important to this juncture of the story. She was a huntress, and a virgin nymph, and her name was Nicaea. As Nonnus writes, the virgin huntress Nicaea did not “care for perfume: rather than honey-mixed bowls she preferred watery draughts from a mountain brook, as she poured out cool water; lonely cliffs with nature’s vaulted roof were the maiden’s inaccessible dwelling” (15.188-90). A standard- issue beautiful sylvan virgin huntress, then, Nicaea enjoyed companionship with animals over people. One day, an oxherd saw Nicaea – a young man named Hymnos. Hymnos, grazing his herd on the edge of the forest, saw the beautiful Nicaea, and he fell deeply in love with her, conniving to steal glimpses of her uncovered legs as she dashed through the forest and the wind lifted her robes aloft. With none-too-subtle innuendo, Nonnus puts these lines into the lovelorn Hymnos’ mouth, as the rural oxherd stares at the beautiful huntress Nicaea – young Hymnos says, “O that I were a shaft. . .O that I were a beast-hitting lance, that she might carry me in her bare hands” (15.258-60). Young Hymnos spoke longingly of the beautiful Nicaea for a page or so, and then he worked up his courage to steal her hunting gear, kissing her armaments with breathless devotion.

And then, finally, he told Nicaea how he felt, and he played her a wedding song on his shepherd’s pipes. Beautiful Nicaea, not being interested in a union with the lusty herdsman, gripped her lance. But the display of resolve only drove young Hymnos into further depths of passionate desperation – he told her that indeed she would kill him if she rejected him, and so to take his life right there and then. After two pages of Hymnos’ flowery rhetoric, Nicaea took him at his word, and shot him in the throat to shut him up, and he died.

It’s quite an unexpected ending, and in my opinion very amusing in a darkly humorous way, but Nicaea’s neighboring forest spirits were displeased that she had simply executed the young man who had so desperately attempted to woo her. Wood and water nymphs of all stamps, and soon Eros himself weighed in on what was to be done, until even Artemis, the grand dame of virginal woodland huntresses, felt a little sorry for the lovesick and departed Hymnos. [music]

The Dionysiaca, Book 16

Still reeling over the death of Hymnos and callus rejections of Nicaea, several divine beings sprang into action. And the god Eros – or Cupid – shot an arrow at our hero Dionysus. After being struck, Dionysus caught a glimpse of the lovely maiden Nicaea, and, unable to resist the whims of lust, he began to pursue her. As rapturous amatory monologues seem to be a compulsion of those pursuing virginal forest huntresses, Dionysus loosed a soliloquy several pages in length as to his newly awakened feelings for Nicaea. He reviewed all of the fine gifts that he could give her, and chased her, calling out, “Wait, maiden, for Bacchos your bedfellow!” (16.145-6). Presumptuous lines, certainly, and Nicaea deemed them so, too, telling Dionysus to get lost, and to definitely keep his grubby hands off of her gear, and in more clever innuendo, she told him, “I keep the bow, you the thyrsus” (16.165-6). Even if she wanted a man, said Nicaea, it wouldn’t be the soft-skinned wine god Dionysus.Dionysus, however, persisted, following and chasing the annoyed huntress until she became parched with thirst. Eventually, Nicaea came to a strange river, and she drank from it. It seemed that crafty Dionysus had worked some of his magic, because the river was wine, and Nicaea was soon seeing double – there were two rivers, two lakes, and a hill became two hills, like a pair of breasts. Nicaea, a stranger to alcohol, passed out, and Dionysus leaned over the unconscious girl. As he did so, a grape arbor grew around them, and Dionysus raped her in her sleep. In the realm between dream and consciousness, the departed herdsman Hymnos taunted the just-deflowered girl who had murdered him, and then he vanished into the underworld.

When Nicaea awakened, she was stricken, tearing at her cheeks and hitting her thighs in rage, then crying and contemplating taking her own life. She fired arrows upwards, hoping that one of them would find its way to Dionysus, and even swore furiously at the river. She was also pregnant, and in due course gave birth to a baby girl. Near where these events had happened, Dionysus built the city of Nicaea – being the famous Late Antique city of Nicaea, about 60 miles southeast of modern-day Istanbul. [music]

The Dionysiaca, Book 17

In Book 17 of the Dionysiaca, the title character gets on the move. Dionysus and his forces packed their bags and tromped eastward through the great cities of Anatolia. The hero’s first major stop was in an obscure spot in the countryside. Dionysus paused his march at the hut of a country dwelling fellow named Brongus. Brongus was a shepherd, and he regaled the visiting Dionysus with all of the country fare he could muster up. Brongus even ingratiated the wine god by playing him some music on shepherd’s pipes, until Dionysus decided to give Brongos the gift of wine. The wine god showed the countryman how to plant and tend to a vineyard, but not long after this, Dionysus had other things to deal with.If you’ll remember, Dionysus had earlier fought an Indian leader named Aristaëis. This Aristaëis had fled eastward to the river Orontes in Syria. There, the number two leader of all of the Indian people lived – he was a prince, and his name, somewhat confusingly, was Orontes. Aristaëis told Orontes about Dionysus plunging eastward into their territory through Anatolia. And Aristaëis told the Indian Prince Orontes about wine – how Aristaëis himself had not had any, but how those Indians who had partook of wine had become feeble and had their heads become clouded. Just as the Indian Prince Orontes became agitated with the news, Dionysus’ armies arrived, and a new battle broke out.

Dionysus’ satyrs attacked furiously, using their great strength to tear enemy troops to pieces. But Prince Orontes was no shrinking violet. He killed two full grown centaurs, and then more of Dionysus’ forces, until the Indian prince and the wine god squared off against one another in a showdown of leaders. A glancing blow to Dionysus’ horned head did nothing to slow him down, but Orontes was undaunted. He taunted Dionysus, telling Dionysus that the god was no burly martial deity, but instead a weak leader of a motley tribe. In response, Dionysus tapped a bunch of grapes on Orontes’ armor, and Orontes’ armor broke and flopped off with a clangorous thud, leaving the Indian prince completely naked! Humiliated, and suddenly aware of his defenselessness, Orontes gave a short speech, and then impaled himself on his sword before tumbling into the river, which is how, according to Nonnus, the river Orontes gets its name. Dionysus taunted his fallen adversary, but in spite of the Indian prince’s defeat, the battle raged on along the banks of the Syrian river, with Dionysus’ armies managing a victory after a fierce day of fighting. [music]

The Dionysiaca, Book 18

News quickly spread of the swift eastward incursions of Dionysus’ armies, and soon, the cities of Assyria heard word of the strange god from the Aegean. In case your antique geography isn’t crystal clear, Assyria was a large ancient civilization centered in the northern part of modern-day Iraq. So, thus far in the Dionysiaca, using the names of modern-day countries for ease of understanding, Dionysus was born in Thebes on the Greek mainland, came of age and fought initial military engagements in western Turkey, hustled down about 500 miles to the southeast, to the Orontes River in Syria, and then traveled eastward into northern or central Iraq.Anyway, the Assyrians, and their king and prince, were absolutely on board with Dionysus, his entourage, and his trademark beverage, and they pulled out all the stops in terms of hospitality. Nonnus describes the Assyrian palace in a passage that could have come from the French decadent movement:

The walls were white with solid silver. There was the lychnite, which takes its name from light, turning its glistening gleams on the faces of men. The place was also decorated with the glowing ruby stone, and showed winecoloured amethyst set beside sapphire. The pale agate threw off its burnt sheen, and the snakestone sparkled in speckled shapes of scales; the Assyrian emerald discharged its greeny flash. Stretched over a regiment of pillars along the hall the gilded timbers of the of the roof showed a reddish glow in their opulent roofs. The floor shone with the intricate patterns of a tessellated pavement of metals. (18.72-83)

In this lustrous palace hall, Dionysus was treated to feasts, and the city broke out in celebrations of the visiting stranger. Palace guests danced jubilantly, and the revelers drank all day long, through twilight and then torchlight and deep into the night.

In the early hours of the morning, Dionysus had foreboding dreams of a lion assaulting him and his forces. Later, once everyone was awake, it was time for the wine god and his forces to set out for the day. The Assyrian king gave Dionysus parting gifts and bade him a very fond farewell for the day. The Assyrian king told Dionysus that Dionysus would be as mighty as Zeus and accomplish similar feats of strength. And with these royal blessings, Dionysus set out – it seems, just to march around the Assyrian capital offering his signature gifts of wine and revelry. After a long day of dashing around the Assyrian heartland and converting the locals to wine, Dionysus returned to his host’s palace. Once there, though, it was clear that something was wrong. The news, as it turned out, was dire indeed. The friendly King of Assyria, who’d played such a good and kindly host to Dionysus, had died.

The Dionysiaca, Book 19

Now, there are conventions in the tradition of the Greek epic. One is the catalog of armies, as we saw earlier. Another is ekphrasis, or very extensive descriptions of objects and works of art, as we’ll see soon. And a third is funeral games – athletic competitions for prizes in the wake of a fallen character, such as we see in Book 23 of the Iliad, when the whole momentum of history’s greatest epic sputters to a weird stop so that we can watch Ajax and Odysseus slip on singlets and sweat on the wrestling mat together. Funeral games, then, the fifteen-minute unaccompanied bass guitar solo of literature, are a narrative convention that allowed poets to write about athletic competitions in ways that they believed would impress other poets also indoctrinated heavily into the epic tradition. Nonnus, in Book 19 of the Dionysiaca, offers us a book full of funeral games for the recently departed minor character, the King of Assyria. I am tempted to simply say, “Funeral games, boom, done,” to summarize this entire book, but to give you your money’s worth, let me offer a quick summary paragraph of Nonnus’ particular iteration of this staple of the epic tradition.Setting forth a bull and a goat next to the tomb of the departed Assyrian king, Dionysus began the affair with a musical contest. In this contest, the father of Orpheus was able to beat an early Athenian king, and the prizes were appropriately doled out. Next up was a dancing competition, during which a pair of prominent satyrs performed pantomime dances, which Nonnus describes in exhausting detail, down to the ancient satyr Silenus twirling and clicking his hoofed feet together. Following the lengthy dancing and pantomime competition, prizes were distributed appropriately, after which Nonnus gets his vast tale back on track. [music]

The Dionysiaca, Book 20

Following the splendid funeral games for the Assyrian king, Dionysus and his great army spent a final evening in the environs of the Assyrian capital. And that night, after further festivities, Dionysus had another prophetic dream. The goddess Eris, or Strife, came to the wine god in his sleep. It wasn’t time to repose by the Assyrian citadel, Eris told Dionysus. The great Indian king Deriades was as yet undefeated, and the goddess Hera was mocking Dionysus’ laggard progress. Other gods, too, were talking, and saying that maybe Dionysus was just indisposed to battle. What kind of a son of Zeus was Dionysus, as he had scarcely garnered any martial victories at all?Dionysus took this speech to heart. He awoke with a sudden cry, and put on his most formidable accoutrements. His army, too, broke camp and began their journey onward. And their ranks were swelled, now, with new Assyrian forces – fighters who voluntarily joined them as they marched onward, further to the south. Passing through what is today Syria and Jordan, the army arrived in the territories of Arabia. Now, Dionysus and company had enjoyed a warm reception in Assyria, but in Arabia, their coming was not met with any friendly fanfare. A king called Lycurgus ruled there. Lycurgus was a bit of a psychopath. He liked to torture and kill for pleasure, and had even imprisoned his adult daughter for life, just for fun. His palace gates were decorated with severed heads and other body parts, and severed hands and feet ringed the doorways of his castle. He also enjoyed collecting scented candles. Just kidding, made that up.

Into the bloodstained halls of the cruel Arabian King Lycurgus came the news that Dionysus had arrived. The goddess Strife appeared disguised as Ares, promising King Lycurgus great things if Dionysus and his forces were defeated. And Strife also appeared to Dionysus, promising Dionysus – falsely – that King Lycurgus might be a valuable ally. And so Dionysus went to the palace of King Lycurgus, and, evidently not put off by the severed body parts stapled all over the place, had an audience with the stranger. Lycurgus, for his part, was immediately hostile. He attacked Dionysus and his forces with a poleaxe. Dionysus’ party, unarmed as they had expected a friendly reception, were caught off guard. His escort scattered, and Dionysus himself hurried away and hid in the waters of the Red Sea. The sea nymph Thetis comforted Dionysus. It wasn’t his fault, she said – Lycurgus had caught him unarmed, and Lycurgus had been aided by Hera herself. Meanwhile, far above the depths of the ocean, Lycurgus roared in anger at the ocean, telling fishermen to drag the water with nets to retrieve Dionysus. At this point, though, Zeus had to say something, warning the violent Arabian monarch to take it easy on the blasphemy and murderous attempts on the wine god’s life. [music]

The Dionysiaca, Book 21

Book 21 of the Dionysiaca opens with Dionysus still hidden underwater in the Red Sea, and Lycurgus chest beating about his partial victory over the wine god. Lycurgus attacked some of Dionysus’ maenads. But persistence and sheer violence beat Lycurgus back, until his armor was torn off and he was wound with vines and leaves. Backed only by Ares, and facing the full brunt of Zeus, Poseidon, Rhea, Dionysus, and more, Lycurgus was undaunted, and he prayed that he might burn his way into the ocean to attack Dionysus directly. Before Lycurgus could get himself in any more trouble, though, Hera came to his rescue.

Cornelius de Vos’ Triumph of Bacchus (17th century). While not exactly a warmongering deity like Mars, Nonnus’ Dionysiaca certainly isn’t the flabby sybarite shown here.

As all this action was happening on the Arabian Peninsula, a courier had gone from Dionysus’ camp over the Hindu Kush to meet with the Indian King Deriades. Deriades, henceforward, will be the central antagonist of the epic, alongside Hera, so Deriades is a name to remember. King Deriades of India took a careful look at the satyr who had come to him on behalf of Dionysus, and mocked the satyr’s appearance. Still, Dionysus’ emissary delivered his message. He told the Indian King Deriades that Dionysus was coming, and that Dionysus “commands the Indians to accept the wine of his care-forgetting vintage, and to pour libations to the immortals, without war, without battle” (21.224-5). While I think a vast majority of us would concede to having a little wine in order to avoid a catastrophic war, the Indian King Deriades felt differently, and he scoffed at the notion of doing this. He wouldn’t pour out libations to Greek gods, he said – to him there were just two gods – earth and water. And if that sounds familiar, it’s because in Herodotus, earth and water are the two things that the Greeks are told to pay as tribute to the Achaemenid Persians in order to avoid war with them.10

King Deriades, then, was uninterested in any peacemaking with Dionysus’ envoys. He told the satyr that the poor satyr would stay with him and be forced to fan him with the creature’s great ears, and King Deriades dispatched a message to Dionysus that Dionysus would now have to face him in battle. The grim message, when it reached Dionysus’ camp, found the army of the wine god in a festive mood. Because Dionysus had finally arisen from the ocean and rejoined his forces. The celebrating Dionysus was soon greeted with the message from beyond the Hindu Kush. Perhaps not wanting to be surprised again in the way that the Arabian King Lycurgus had surprised him, Dionysus again had his forces prepare for travel, and the armies built a fleet of ships, while Dionysus himself sped eastward overland. The Indian King Deriades, no mere blowhard, prepared for the western army’s arrival. Along the banks of the Jhelum River, where the northern parts of India and Pakistan come together today, Deriades prepared an ambush – one carefully concealed by the close trunks and dense leaves of a silent forest. [music]

The Dionysiaca, Book 22

Dionysus and his forces arrived at the Jhelum River to face off against those of the Indian King Deriades, and the environs of the waterway broke out into celebration. Wine emerged from rocks, and honey appeared in streams, as animals began dancing, and tigers and elephants pranced about. The hidden Indian army watched all of these strange things happening, and quaked with fear. It was perfectly clear to them that the forces of Dionysus were no mere marauding foreign army, and that something strange and divine had come. They prepared to offer supplications appropriate to a visiting deity, but the goddess Hera urged them instead to fight. Before the Indian armies could pursue their ambush, though, a stray nymph from the river Jhelum saw the Indian forces, and rather than supporting the armies of her own territories, she hurried to tell Dionysus of the planned ambush.The next day, just after dawn, battle broke out. A powerful Indian leader named Thureus commanded the forces from the east, while Dionysus himself commanded his motley battalions. Aiming his thyrsus staff into Indian ranks, Dionysus scattered them, and one of his lieutenants, the father of Orpheus, also distinguished himself in that day’s combat. Borrowing widely from the standards of epic war poetry, Nonnus treats us to several epic similes, exceedingly violent deaths and dying men’s teeth gnashing the bloody turf, the aristeia, or invincible battle frenzies, brief confrontations between prominent captains, and nearby waterways becoming clouded with blood. And once again borrowing from the standards of earlier epic poetry, eventually the nearby river, in this case again the Jhelum, became so clouded with blood that the local spirits and indeed river itself elected to rise up against those making war on its shores. [music]

The Dionysiaca, Book 23

Dionysus and his lieutenant Aiacos fought enemy forces fiercely in the reddening waters of the river Jhelum. Enemy forces slogged through the mud, sinking to their ankles and then feet and then torsos, and lower still. As the hours went by, Nonnus tells us, “The carnage was infinite; [the River Jhelum] covered the dead with his reluctant flood, and became their tomb” (23.76-8). But the river itself became furious – its banks were becoming completely clogged with swollen corpses, and with armor, weaponry. And living warriors also churned in the rivers – cavalrymen mounted on horses, foot soldiers, chariots and elephants.The river struck back. It amassed its water on the land and threw a cataract of fluid at Dionysus and his forces. Dionysus, undaunted, taunted it in return, and the river prepared to drown the western army altogether. But Dionysus fought water with fire, drawing flames from a nearby embankment and pressing an inferno directly into the river itself. It was an extreme move, this hurling a burning blaze into a river, and various water deities balked at Dionysus’ attack on the river Jhelum, including the water gods Tethys and Oceanos. The latter, in particular, planned a severe counterattack against Dionysus – they couldn’t have water being burned with fire, for goodness sake! – and Oceanus summoned the great water deities, including Poseidon himself, to destroy Dionysus and his armies with a catastrophic flood.

The Dionysiaca, Book 24

Fortunately for everyone, a global flood was prevented. The River Jhelum asked Dionysus to relent with Dionysus’ blazing assault against the waterway. In a lengthy monologue, the river told Dionysus that it was not opposed to the wine god, and that it had once even washed Dionysus Zagreus, the wine god’s primal progenitor, in bygone times. Hearing the river’s appeal, Dionysus relented, and so Dionysus and his armies were finally able to traverse the River Jhelum, and cross more deeply into Indian territories. There, they made themselves at home, hunting and foraging and making their way further eastward.And speaking of eastward, the Indian King Deriades heard word of his forces’ defeat at the River Jhelum. One of Deriades’ captains gave him the terrible news – Dionysus himself had fired leaves in volleys at the Indian army, and through shaking his thyrsus staff, he had beaten legions of the eastern king’s forces. Sorrowful, and yet resolved, Deriades went to consult with some of his Brahmins, and Nonnus’ use of this word, as scholar H.J. Rose writes in a note, is “The first indication that Nonnos knows anything of India.”11 Anyway, so, King Deriades retreated to an Indian city, leading his elephants away from the war torn banks of the Jhelum. Hearing news of India’s defeat in battle, citizens of the city lamented and wept together, wives and brides-to-be consoling one another, some of them vowing not to come near the River Jhelum again, as it had been the site where those they loved were massacred.

Meanwhile, Dionysus and his army guzzled endless amounts of wine and celebrated their victory. They sang songs, and one minstrel from Lesbos offered an 80-line song about a weaving contest between Aphrodite and Athena which, while not strictly relevant to the events of the story nor thematically appropriate to the solemn aftermath of an awful battle, was most certainly – um – a song performed in Nonnus’ ever-digressive Dionysiaca. As uneven as some of the Dionysiaca is sometimes, though, Nonnus concludes book 24, the halfway point in the epic, with some rich and haunting lines that demonstrate the strange beauty of the story. Nonnus says of Dionysus’ army that:

when they had surfeit of this table so well furnished with liquor, they fell on their beds in the wilderness spluttering wine: dropping on dappled fawnskins, or on spreads of leaves, or just spreading goatskins on the ground amid the deep dust. Some stretched their armoured bodies in the soldier’s sleep, and held traffic with battlerousing dreams. . .Tribes of leopards and wild packs of lions and hunting-dogs took turns in guarding Dionysos in the wilderness with sleepless eyes; all night they kept vigil in the mountain forest. . .Long lines of torches flashed up to Olympos, the lights of the dancing Bacchants which had no rest. (24.330-6, 342-7)

And that concludes the first half of Nonnus’ epic. [music]

Nonnus’ Unique Style in the Dionysiaca