Episode 97: Blood and Ivy

The Dionysiaca, Part 2 of 2. The last surviving Greek epic of antiquity draws to a close with Dionysus fighting wars far to the east, in India.

| Read Transcription | References and Notes |

| Episode Quiz | |

| Episode on Spotify | Episode on Apple Podcasts |

| Previous Show | Next Show |

Nonnus’ Dionysiaca, Books 25-48

Gold Sponsors

Andy Olson

Bill Harris

Jeremy Hanks

John David Giese

ML Cohen

Silver Sponsors

Alexander Silver

Boaz Munro

Chad Nicholson

Francisco Vazquez

Hannah

John Weretka

Michael Sanchez

Anonymous

Steve Baldwin

Sponsors

A. Jessee Jiryu Davis

Anonymous

Aaron Burda

Alysoun Hodges

Angela Rebrec

Ariela Kilinsky

Benjamin Bartemes

Bob Tronson

Brian Conn

Chief Brody

Chloé Faulkner

Chris Tanzola

DOUG’S BIGGEST FAN

Ellen Ivens

Eric Carpenter

EvasiveSpecies

Jason Barger

Joe Purden

John Barch

Joran Tibor

Joshua Edson

Kyle Pustola

Laura Ormsby

Laurent Callot

Leonie Hume

Maria Anna Karga

Mark Griggs

Mike Swanson

Mr. Jim

Oli Pate

Anonymous

Anonymous

Riley Bahre

Robert Baumgardner

Rod Sieg

Ruan & Nuraan

Ryan Walsh

De Sulis Minerva

Sidsel Vinge

Sonya Andrews

Steven Laden

Sue Nichols

Susan Angles

Tom Wilson

Valentina Tondato Da Ruos

Verónica Ruiz Badía

Vika

The Dionysiaca is a 48-book-long epic poem about the god Dionysus’ journey to the east, to bring wine to foreign nations and to subdue them militarily. Dionysus, as we learned last time, was not just a plump spokesman for wine in the ancient Greek imagination, but also, a deity associated with transformation, insanity, and animalistic violence – some his epithets can be translated as “roaring,” “howling,” and “eater of raw flesh.” And in addition to this surprising dark side to the familiar wine god, there was a secondary Dionysus, as well, worshipped by the Greek Orphic cult – Dionysus Zagreus, a primordial son of Zeus who’d been massacred before he could even come of age. So the deity Dionysus, in the epic that we’re currently reading, was a god with several different faces – jovial, certainly, but also terrible and savage, and even having a mysterious link to an older version of himself who died an awful death back when the world was still young.

The protagonist of our epic for today was thus complex, as too, is the epic itself. The Dionysiaca, as you hopefully recall, began with a lengthy preamble that told us about Zeus fighting the monster Typhoios, about the founding of Thebes, the births of the two different Dionysuses, and the early years of the wine god. Dionysus, the product of one of Zeus’ many illicit affairs, was the object of the goddess’ Hera’s jealousy, and throughout the Dionysiaca, Hera is the main antagonist, hounding her husband’s illegitimate son in book after book. While Hera is Dionysus’ most consistent opponent in Nonnus’ Dionysiaca, Dionysus also faces a human enemy – the Indian King Deriades.

As we learned last time, the Dionysiaca tells us about Dionysus’ conquest of India. But India in the epic poem shouldn’t be thought of as the actual subcontinent in south Asia. Indians in the Dionysiaca are simply people who live east of Mesopotamia. Nonnus’ Indians have Greek names. They’re familiar with Greek gods, and the Greek myths. They are, rather than citizens of the historical Gupta Empire flourishing during Nonnus’ lifetime, imaginary easterners from the mythological past. Nonnus himself didn’t invent the tale of Dionysus going to the distant east – this was at least a thousand-year-old legend by the time he came along.1 But Nonnus does offer a very long, detailed, and extensively ornamented version of it. And speaking of ornamentation, let’s review a couple of things about Nonnus’ style.

Nonnus’ style is perhaps the opposite of minimalist. He has been called “baroque” and “jeweled” and more.2 His 20,000-line epic contains thousands of allusions and proper nouns, and represents the culmination of hundreds of years of ancient Mediterranean poetry written, to a large extent, for poets and scholars rather than for the general public. Dense, florid, and adorned with dozens of long speeches, stories within stories, and narrative digressions, the Dionysiaca can be as frustrating as it is absolutely unique. And though Nonnus has suffered no small amount of criticism for his elaborate style, ultimately the story that he tells still manages to engage the reader, sometimes just due to its sheer, exuberant strangeness, book after book after book.

So, where we last left off, Dionysus has reached the River Jhelum in the eastern reaches of modern day Pakistan, and he has emerged victorious from a major engagement with eastern forces there. The armies of India, or we should say quote unquote “India,” are still out there, led by the enemy monarch Deriades, together with his powerful son-in-law, Morrheus. Dionysus, as we open Book 25 of the epic, has made progress, but at the same time he has been hindered due to the opposition of his stepmother Hera and the god of war Ares, who both support the Indian side of the conflict, and so the second half of the Dionysiaca opens with the wine god facing both human and divine enemies in a strange land, though he is ultimately backed by Zeus and a magic army full of satyrs, centaurs, dryads, and water nymphs. So let’s jump back into the story – the edition I am occasionally quoting from today is the W.H.D. Rouse translation, published by Loeb in 1940, and as of 2022, still the only full English translation of this poem available. [music]

Nonnus’ Dionysiaca, Book 25

The war between Dionysus and the armies of India, Nonnus tells us, had begun in earnest with that first major engagement on the banks of the Jhelum. The poet Nonnus, halfway through his immense story, invokes the muse once more, but writes that being inspired by Homer, he will only tell of the seventh and final year of the great conflict between the armies of Dionysus, and those of the east.

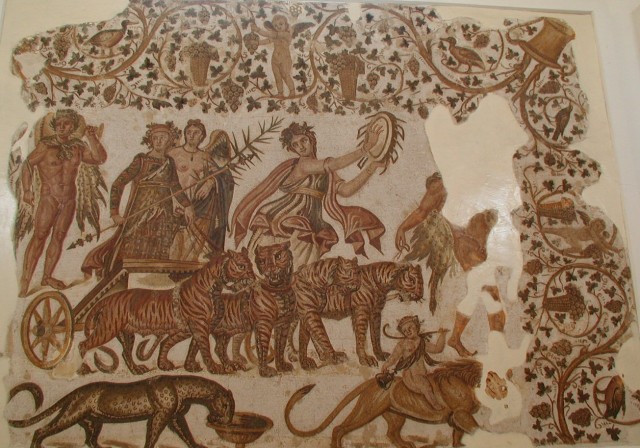

Achilles’ shield in a 1720 engraving that accompanied Pope’s Iliad. Ekphrasis is one of the many epic conventions Nonnus emulates in the Dionysiaca.

Following this preamble to Book 25, Nonnus takes us to the seventh year of the epic poem’s central war. Dionysus, by this time, was used to living in his military camp in the forests of India. As for King Deriades of India, he was despondent and fretful, having seen the campaign against him continue for so long. Nonnus writes that one morning, seven years into the conflict, “The [Indian] people spent the night on the lofty towers in fear, and the guards of the highcrested citadel lined its wall with their shields. On the hills, Dionysos often angry reproached Hera, that she had again checked his battle with the Indians for jealousy” (25.300-3).3 Frustrated as Dionysus was, his angst was only deepened when he met with a deity called Attis, son of the goddess Cybele. Attis asked Dionysus why on earth it was taking so long for Dionysus to wrap up the military campaign, and Dionysus burst out that his stepmother Hera was against him, and that Ares, the god of war, fought on behalf of the Indians, too. The deity Attis told Dionysus to take heart, though, promising Dionysus that the young wine god would, eventually, prove successful. Attis said that Dionysus’ grandmother Rhea would support his side of the great military conflict, and he gave Dionysus a fine shield.

Having delivered his message to Dionysus, the god Attis sped away, leaving Dionysus and his compatriots to marvel at the wine god’s shiny new shield. Now, one of the conventions of epic poetry is ekphrasis, or the extremely detailed literary description of a work of art – Homer describes Achilles’ shield in the Iliad, Apollonius describes Jason’s cloak in the Argonautica, Virgil describes Aeneas’ shield in the Aeneid, and all of these descriptions go on and on for pages. So, nothing if not a thorough imitator of all epic conventions, Nonnus throws himself into a multi-page description of Dionysus’ shiny new shield, telling us about its general design and all of the things depicted on it – the earth and sea, the constellations, the city of Thebes and its prominent citizens, Zeus and his cupbearer, various other deities, an entire inset narrative of a Lydian heroine named Moria, her brother, tragically killed by an enormous serpent, and how Moria convinced a giant to help her get revenge on the serpent, how the giant squished the serpent’s head with a tree and then the serpent’s wife came and lamented his death, and how Moria brought her brother back to life. Nonnus informs us that Dionysus’ shield also depicted the titan Rhea herself tricking her husband Kronos into eating a rock, rather than eating Zeus, which had been Kronos’ plan, and then that the shield also featured Zeus’ father Kronos vomiting up the rock. And with precisely 178 lines expended in telling us about the nice artwork on the wine god’s splendid new shield, complete with its doubtless impressive vomiting scene, Nonnus wraps up his ekphrasis dutifully, and moves on to say that night fell over the encampment of Dionysus, and everyone went to sleep. [music]

Nonnus’ Dionysiaca, Book 26

That night, the goddess Athena came to the Indian King Deriades, again the human antagonist of Nonnus’ epic. Athena disguised herself as one of Deriades’ former commanders, and visited Deriades in a dream. Deriades, at this point, had sworn off the war, but Athena, who was on Dionysus’ side, told Deriades that the king ought to throw himself back into the fray to get revenge for the sake of those fallen during the conflict. I’m not sure precisely how this action of Athena’s was good for anyone – Athena could have simply told the crestfallen King Deriades to surrender, and have a couple of glasses of wine with Dionysus so that everyone could peacefully go home, but as we’ve seen so many times in past episodes, in ancient epics Olympian deities aren’t very rational or expeditious in anything that they do.The next morning, then, newly resolved to continue fighting, the Indian King Deriades summoned his forces, and Nonnus offers a catalog of easterners from faraway destinations along the Ganges and Indus Rivers, as well as southern Afghanistan, Kashmir, and elsewhere. And a quick side note here. As we noted at the end of the previous show, it’s very safe to say that Nonnus’ knowledge of India and its geography came from books, rather than personal experience, and that these books were works of factually iffy ethnography. Nonnus seems to have been an energetic, but gullible fan of ancient works of geography, from Herodotus onward, ancient books that weave reasonable enough sounding history and geography with absurd sounding myths. Thus, when Nonnus mentions a people and a place in south Asia not attested in any history book, for instance, no one really knows if he’s referencing some ancient group otherwise lost to history. When, however, Nonnus assures us that a people called the Uatocoitai marched to help Deriades, and that these people had ears so gigantic that they slept on them (26.94-6), or that river horses with special black hooves paddled through the waterways of what’s now eastern Pakistan (26.236-7), we can be confident that Nonnus is reading old and silly works of ethnography and repeating their stories in his own epic.

One of the more toweringly ridiculous passages of the often strange Dionysiaca occurs in Nonnus’ catalog of eastern troops right here in Book 26, when Nonnus tells us about how some Ethiopians served in the Indian army. First of all, Ethiopians fighting for India is odd – the regions aren’t exactly neighboring, and Nonnus supposedly lived along the central Egyptian Nile, so it isn’t as if didn’t know Ethiopian people, or where Ethiopia was. Anyway, here’s the passage – this one is not for an age, but for all time. Nonnus writes,

The Ethiopians follow a peculiar and clever fashion in battle. They wear the top of a dead horse’s head, hiding in this disguise the true shape of their faces. Thus they fasten another face on the human head, and join the dead to the living. So in the battle they startle the unwitting foe with this bastard head; and their chieftain lets out a deceitful sound from his mouth, and gives vent to a horse’s neigh with his manly voice. (26.339-49)

There’s some back story to this – Herodotus had once written about Ethiopian military dress, and Virgil had once written of a nefarious Italian king who’d bound the bodies of the dead and living together, so Nonnus seems to be shooting for some sort of a multi-layered allusion.4 But warriors capped with rotting horse heads and making horsey sounds while going into battle is perhaps a less intimidating image than Nonnus intended to convey. And with his colorful, and abusively pedantic book-long inventory of quote unquote Indian primary and auxiliary troops complete, following on the heels of an equally pedantic ekphrasis of Dionysus’ shield, the poet Nonnus finally gets the second half of his epic in motion. [music]

Nonnus’ Dionysiaca, Book 27

The morning after Athena came to Deriades, Zeus caused a rain of blood to patter down onto Indian soil, heralding the dark events that would soon unfold. A ways north of modern day Islamabad, around the headwaters of the Indus, the Indian King Deriades prepared his troops for the coming resumption of hostilities. Deriades told his forces that they could by all means beat centaurs and satyrs in battle. And Deriades addressed Dionysus, telling the wine god he wasn’t afraid of Dionysus’ divine birth, nor his special new shield, nor the gods who supported Dionysus. Once Deriades wrapped up his 113-line, allusion spangled motivational monologue, Deriades led his army down to the lowlands to face Dionysus and company. Dionysus’ armies, heartened by a comparable speech by their leader and broken down into four main companies, were scattered broadly over the northeastern and western parts of modern-day India, and they also prepared for the impending resurgence of the war.Meanwhile, up on Mount Olympus, the gods met and had a chat. Perhaps chat is the wrong word, as the meeting in question involved Zeus offering a long speech about the war that was about to unfold, in which Zeus inventoried which deity was on which side – Hera and Hephaestus planned to fight on behalf of the Indians, whereas Zeus himself, Athena, and Apollo would all campaign in Dionysus’ behalf. And so, with multiple catalogs of armies, multiple ekphrases written, funeral games checked off, and I am going to realistically estimate 1,000 allusions and esoteric proper nouns by the close of Book 27, the great war that is the climax of the Dionysiaca finally began. [music]

Nonnus’ Dionysiaca, Book 28

The armies of Dionysus threw themselves into battle. They wielded conventional weaponry, but also unique armaments powered by their god – ropes of ivy that slashed human flesh, thyrsus wands, leaves, and twigs. They rode panthers, bears, and lions, and their buckskins and leafy accoutrements were all in sharp contrast to the more conventional armor of the Indians. A Dionysian archer managed to take down the elephant King Deriades was riding, but missed the monarch himself.As with the Iliad, Aeneid, and more, warfare in Nonnus’ Dionysiaca, when it breaks out, is narrated with gruesome detail, the poet offering gory inventories of how this and that warrior on each side died. An Indian was speared to death; a Dionysian had his arm and entire shoulder severed by a sword blow; cavalrymen killed cavalrymen, and as weapons struck them and their mounts, they tumbled dead and mortally injured into the dust. Soon, powerful forces rumbled to the aid of Dionysus’ army – the Cyclopes, making war on behalf of Zeus. One of the Cyclopes, a giant armed with burning logs, smashed his foes, and another, who wielded lightning, shot barbs of electricity into the enemy army. A third Cyclops wielded a giant iron hammer on behalf of Dionysus, and flung a huge chunk of earth at King Deriades, bowling the enemy monarch over. More Cyclopes appeared, one wielding a giant crag as a shield and another using a fir tree as his spear and club, and another still brandishing a 30-foot sword and smashing enemies into the ocean.

The Cyclopes weren’t the only power that aided Dionysus during this battle. Scores of Corybants – those zealots associated with the wild rites of the Anatolian goddess Cybele – Corybants, too, threw themselves into combat for Dionysus, their manifold weaponry slamming against the arms and armor of their foes. The general clamor of the battle – cries of Cyclopes and humans, wild animals and the booming of crushed rocks – the sound was so intense that it was audible on Mount Olympus, and the seasons themselves quaked in apprehension. [music]

Nonnus’ Dionysiaca, Book 29

The war that day, so far, had favored the forces of Dionysus, much to the goddess’ Hera’s disfavor. And so Hera heartened the faltering King Deriades, and Deriades himself rushed through his ranks to steel their courage. At this point in the narrative, Deriades’ son-in-law appears as a major character. This son-in-law’s name is Morrheus, and he’ll be a big presence for a number of books. Deriades’ son-in-law Morrheus sprang into action first by killing a number of powerful satyrs.Although the Indian forces were rallying, the Dionysian army continued its all-out assault. A warrior named Hymenaios, a beautiful young man of whom Dionysus himself was quite fond, launched arrows into enemy ranks, and Dionysus promised him that if he hit the enemy king, he’d win victory, and the heart of Dionysus himself. Meanwhile, though, a very skilled Indian archer, spurred on by divine power, took aim with a long arrow, planning to kill Dionysus. Zeus, however, caused the arrow to swerve, and it hit handsome young Hymenaios instead. The wine god’s companion was wounded in the thigh, and Dionysus quickly ushered him off of the battlefield. Tending to Hymenaios’ wound, which proved to be non-lethal, Dionysus offered a long speech – he had already lost his beloved satyr Ampelos, he said – he couldn’t stand to lose another adored male companion. With prayers and invocations, Dionysus then used his ivy and his wine to heal the thigh wound of his beloved compatriot, and Hymenaios hurried back into battle, this time shadowed by Dionysus.

The forces of Dionysus fought with wild abandon, former forest hunters pursuing their enemies like animals, Aegean islanders thundering around the battlefield in chariots, Corybants slamming their hands onto skin drums to frighten their foes, Maenad war maidens firing viny arrows into foes. A Dionysian priestess shot ivy vines and leaves into enemy ranks and tore apart steel armor; another female devotee of Dionysus danced and spun and killed with her thyrsus while clashing cymbals together. Still, though, the enemy forces fought hard in return, severely wounding centaurs and other allies of Dionysus, and the wine god himself intervened to attend to the sources of their injuries and to heal their wounds.

The battle continued with hauntingly strange and distinct imagery. Throngs of Corybants continued to throw themselves into the fray to the beating handheld cymbals and the noise of pan flutes; a satyr lashed out with his goat feet, tearing open the midsection of an enemy archer, and Dionysus swelled in size up until his top was in the clouds. While the forces of Dionysus were already quite successful in this climactic battle of the war’s seventh year, soon divine help abetted their victory even more.

Dionysus’ grandmother, the titan Rhea, hurried to where the god Ares was sleeping. And Rhea told Ares that Ares had to leave the battlefield to attend to something. Ares, Dionysus’ grandmother Rhea said (and she was lying, by the way) ought to be advised that Ares’ former lover Aphrodite was once again sleeping with Hephaestus (Hephaestus was Aphrodite’s former husband).5 However false and of questionable significance this dispatch was, the dream convinced Ares that he absolutely had to do something, and when he awoke, he sped away to find his ex-girlfriend Aphrodite, because how dare she sleep with her ex-husband? – even though no one was sleeping with anyone and Ares had just been fooled. Then, in an innuendo laden description that closes Book 29, Nonnus writes, “Then [Ares] left. . .and rose into the heaven, [so] that spear in hand he might arouse battle for [Aphrodite] among the [Olympians]” (29.376-9). As to the poor Indian King Deriades and his people, this departure left them with one less key strategic ally. [music]

Nonnus’ Dionysiaca, Book 30

With Ares out of the picture, Dionysus continued to fight enemy forces fiercely, the wine god taking the right wing of the army and his chief lieutenant Aristaios taking the left. These assaults were noted, however, by the aforementioned Morrheus, son-in-law of the great Indian King Deriades. Morrheus, seeing Dionysus’ forces “fighting with leaves and flowery shafts” (30.14), wondered what on earth was going on, exclaiming, “My warriors fall, struck with a thyrsus [wand] or rubbishy leaves” (30.17). Morrheus said that the Indians’ steel and bronze were useless against the strange weaponry of Dionysus’ armies, but, heartened by his father-in-law King Deriades, Morrheus fought back as hard as he could. He wounded a powerful Dionysian warrior, and was about to kill this same warrior and his brother, but they were sons of the god Hephaestus, who protected them.Following this divine intervention, the Indian prince Morrheus fearlessly pressed his attack, killing a prominent Dionysian warrior, engaging a group of satyrs, and then, in a dramatic scene, pursuing and slaying one of Hephaestus’ sons, after all – a warrior called Tectaphus. The Greek war goddess Enyo then stirred the fighting up to even more intense levels, and the Indian prince Morrheus killed more Dionysian forces, including eight maenads – those female devotees of Dionysus.

The goddess Hera, trying to salvage something out of another day that seemed to be going against her armies, caused King Deriades to appear with blinding brightness in a corona of fire, and the sight of him terrified not only Dionysus’ armies, but also the wine god himself. Just as Dionysus fled, though, his allied goddess Athena came to him with words of inspiration. Athena said he ought not be afraid, for many reasons, not the least of which was that their father Zeus had fought the titans themselves. Dionysus, said Athena, absolutely had to get himself back into the fray – when he did, she’d join in, too, and Athena reminded him she was no shrinking violet. And so Dionysus rejoined the combat, as Nonnus writes, “He slew a round hundred of his enemies with destroying thyrsus, and he wounded many in many ways, striking with spear or bunches of twigs or clustered branches, or throwing stone, a rough missile” (30.298-30). Under the dual assault of Dionysus and Athena, then, the Indian army buckled, and the Dionysians won the day once more. [music]

Nonnus’ Dionysiaca, Book 31

Hera had used various forces at her disposal against the wine god Dionysus, opposed to him always because he was the illegitimate product of her husband’s affair with the Theban princess Semele. But now, it was time to try a new route – the route of subterfuge and trickery. Never one to reinvent the wheel, Nonnus recycles a narrative from Homer’s Iliad – Hera decided that she would seduce Zeus so that Zeus would fall asleep for a while, his energies expended in lovemaking, and then advance her agenda down below on the battlefield, unhindered by the father of the gods.Prior to the seduction part of Hera plan, Hera went down to Hades to meet with Persephone, the queen of the underworld. If you’ll remember from about 400,000 pages back, Persephone had once been the mother of Dionysus Zagreus – the first Dionysus, the fully divine entity who seemed to have such a glorious future. Hera, in her clandestine mission to Hades, told Persephone that that the new Dionysus, the half-breed son of Semele and Zeus, would soon become a lord in Olympus, overshadowing the tragically departed Dionysus Zagreus, the real, fully divine Dionysus. Hera asked Persephone for help – Persephone didn’t want her beloved Dionysus Zagreus forgotten, did she? Wouldn’t Persephone loan Hera a certain piece of military grade weaponry currently resident in Hades, so that Hera could defeat the upstart half breed newfangled Dionysus? Persephone, hearing all of this, was convinced. Persephone consented to loaning Hera the services of this weapon – the powerful fury Megaira.

As a quick side note, I wonder what Nonnus was thinking when he wrote this underworld scene. Because the reason that Dionysus Zagreus – Persephone’s child and the first Dionysus – had been cut to pieces by titans was none other than Hera herself. Hera’s appeal is thus akin to, “Hey Persephone, remember when my husband raped you, and then I had your baby ripped to pieces? Well, I need your help.” Without belaboring the point, as we’ve often noted, the Olympians in Greek epics behave with all of the mental clarity of monkeys on PCP.

Anyway, so, Hera secured the help of the fury Megaira, who accompanied her to India to await further instructions. As for Hera, in a copy and paste sequence taken from the Iliad, Nonnus tells us that Hera also enlisted the help of the goddess Iris. Iris then went to the realm of the ancient deity Sleep, and secured Sleep’s support in making Zeus zonk out for a day. Hera herself went to Aphrodite. Hera told Aphrodite that Hera was worried that she would be set aside in Olympus for the sake of Zeus’ latest fling, Semele, and his darling new son Dionysus. Wouldn’t Aphrodite help her mother-in-law twice over, Hera? Wouldn’t Aphrodite loan Hera Aphrodite’s special tools of seduction? [music]

Nonnus’ Dionysiaca, Book 32

Aphrodite said that she would indeed help Hera. Aphrodite took off her sexy girdle, and handed it to the other goddess. With this girdle in her possession, Hera made further preparations for her upcoming romantic evening, arranging her hair nicely and putting on alluring garments. Part of Hera’s strategy of selecting the most seductive accoutrements, in Nonnus’ words, was as follows, “the embroidered robe she wore was her oldest, still bearing the bloodmarks of maidenhead left from her bridal, to remind her bedfellow of their first love when she came to her brother a virgin” (32.31-4). I’m not even sure what to say about that passage, other than that at least once in every book of Nonnus’ Dionysiaca there’s a sentence so bizarre and unique that you have to stop and read it several times, just to make sure that you yourself haven’t been drinking too much wine. Anyway, so, wearing Aphrodite’s magical girdle, with her hair arranged just right, bedecked in lovely jewels and adorned in a gown with bloodstains around the crotch, Hera hurried to begin her steamy evening with Zeus.After a short conversation, Zeus said that he found Hera alluring indeed – more alluring than a number of other women he had copulated with. Zeus then spun a cone of golden clouds around them to serve as a shelter, right out in the open, and behind its walls, the couple made love. Flowers blossomed all around – irises and anemones, and afterward the pair reposed on a magical couch that Zeus had caused to appear, Zeus himself falling asleep. With Zeus out of action, then, it was time for Hera’s plans to begin.

The fury Megaira went to where Dionysus was. She rattled her rattle and cracked her whip in front of the wine god, unleashed poison into the air and appeared as a gory lion. The fury Megaira filled the air around Dionysus with sparks and droplets of poison, and suddenly, shockingly, Dionysus lost his mind. In doing so, Dionysus became very dangerous to his allies. He killed the great pythons who loved him, slaughtered lions and broke the masts of trees, chased water nymphs out of the river and made his satyr brethren hide from him in the ocean.

As Dionysus reeled under the influence of divine madness, the Indian King Deriades threw himself into an attack. Just then, Ares, too, rejoined the war on the Indian side, and the female warriors of Dionysus were encircled by steel. It became a massacre. The Indian Prince Morrheus, who had held his own even when Dionysus was in command, was especially deadly, slaughtering his foes with spears and jagged stones. Dionysus’ army fell into panic. His commander Aristaios was struck by an arrow in the shoulder. Some Dionysians and fought, but most fled. Water nymphs hid in the depths, and dryads concealed themselves among the branches and leaves, and they reeled in shock that their dauntless commander was suddenly deranged. [music]

Nonnus’ Dionysiaca, Book 33

The Indian Prince Morrheus was at this point chasing a Dionysian war maiden. Her name was Chalcomede, and she’ll be a major character for a couple of books here, so let’s get this in our minds – Morrheus, son-in-law to the Indian King Deriades, as Book 33 opens, is dashing through the forest after the warrior maiden Chalcomede, one of Dionysus’ warriors. A minor goddess, flying through the area, saw the despoliation of Dionysus’ army – the fleeing satyrs and dead centaurs, the terrified nymphs and dryads, and the poor maiden Chalcomede, fleeing from the powerful warrior Morrheus. And this minor goddess flew up to Aphrodite, and told Aphrodite the news – Aphrodite’s brother Dionysus was in trouble – his army was being routed! Aphrodite heard all of these details, and then she summoned her son Eros, or Cupid.Cupid was, at that point, goofing around and playing games on a mountaintop with Dionysus’ lover Hymenaios, but when Cupid heard that he was needed he quickly went to his mother’s court, where he learned the situation. Dionysus and his forces were in grave danger, but no one in the universe was a match for the bow of Eros – wouldn’t Cupid get down there, and start making people fall in love with one another, in a fashion advantageous to the faltering Dionysus? Cupid said he would, and, wasting no time, he fluttered down to the battlefield. Eros saw the aforementioned Indian Prince Morrheus chasing the damsel in distress Chalcomede, and, dramatically steadying his bow against the neck of the maiden herself, Eros shot the marauding Morrheus in the heart. [lyre plays Bon Jovi’s “Shot Through the Heart.”] Just making sure you’re paying attention. Causing Morrheus to fall in love with Chalcomede, evidently, was help enough, as far as Cupid was concerned, as he presently left the battle field and returned to his previous diversions.

The great warrior Morrheus was now smitten, and the maiden Chalcomede knew it. She pretended to return his affections, and told him a sultry story of the god Apollo pursuing the nymph Daphne. Chalcomede, seeing that her pursuer was stalled and dizzied with love, looked for Dionysus, hoping to restore him to his right mind. As for Morrheus, he renounced warfare and the god Mars and said as far as he was concerned, he wanted to be enslaved to Chalcomede and bow to the yoke of her lord Dionysus. In the evening, by starlight, Morrheus’ ardor grew in leaps and bounds, and he looked up at the constellations and soliloquized that he wished he had the form of a satyr so that he could more easily seduce Chalcomede. As for the Dionysian maiden herself, Chalcomede feared that her evasive tactics would fail, and the lusty Morrheus would force himself on her. Looking out over the ocean, Chalcomede, too, loosed a soliloquy, asking for guidance from earlier heroines, and revealing that she planned to throw herself into the ocean rather than suffer the lusts of Morrheus. The ocean nymph Thetis came to Chalcomede, though, and said Chalcomede should not commit suicide – Dionysus’ forces needed Chalcomede alive to continue to distract the love struck Morrheus – otherwise Morrheus would continue to decimate the Dionysians. Thetis promised that the anxious Chalcomede would preserve her virginity, and Thetis concealed Chalcomede in a cloud so that the maiden wouldn’t be apprehended by Indian forces and brought to Morrheus. [music]

Nonnus’ Dionysiaca, Book 34

Meanwhile, Morrheus himself was deliberating about his next course of action with Chalcomede. The Indian prince Morrheus, again the son-in-law of the Indian king and main antagonist Deriades, was incredulous at his own feelings, and admitted that this was the case to one his acquaintances. He dreamt of beautiful Chalcomede, and awoke in the morning thinking obsessively of her once more. And as distracted as the powerful Morrheus was, Dionysus’ army was also distracted, and anxious about their leader. The wine god’s Bacchants, or female celebrants and warriors, were no longer berserk in the ecstasy of battle and warfare, but instead forlorn and uncertain. The satyrs and pans, too, had stopped their customary rites and rituals, having lost the heart for warfare.In contrast, the Indian King Deriades prepared for a crushing assault. His son-in-law Morrheus captured a bundle of Bacchants and gave them to the king as slaves. Seeing that the tides of battle had turned, King Deriades was exultant. He said beating Dionysus in India would only be the beginning – he’d gather his armies and take them across the continent and chase the Dionysians out of Anatolia, destroying them, finally, in their capital of Thebes. Envisioning his looming total victory, Deriades executed some of his war prisoners, hanging them, and burning them alive, and drowning them. The Dionysian forces were rounded up, corralled and driven behind the walls of a city.

As these catastrophes unfolded, Chalcomede continued doing her best to distract Morrheus. Chalcomede looked at him flirtatiously from far off, standing on the city walls where the Dionysian army was now contained. Morrheus chased Chalcomede around, staring at her, and tried to coax her with words of devotion. He was defenseless before her, he said. His weapons were of no use. He would defect and serve Dionysus if she asked him to. Her deerskin garments made him hate his armor.

And though Prince Morrheus was thusly distracted, King Deriades was not. King Deriades drove more and more Dionysian warriors behind the city’s walls, and Dionysus’ female warriors suddenly had their martial spirit fall away from them. Weakened, uncertain, and now trapped behind city walls, the Dionysian forces were at rock bottom, and King Deriades prepared to finish them off. [music]

Nonnus’ Dionysiaca, Book 35

King Deriades smashed his way into the city, killing his enemies with spear and sword, resolved to steal victory from the jaws of defeat. The streets of the city became slick with blood, although King Deriades forbade any of his men to rape their female adversaries. One of Deriades’ warriors was overcome with lust for a fallen Dionysian maiden whose clothing had come off, and considering but ultimately deciding against an act of necrophilia, he let loose a forty-line monologue in which he wished she could be healed and brought back to life so that he could have sex with her. This weird little soliloquy, however, was an exception to the general violence that exploded in the city as Indian forces clashed with those of Dionysus.The maiden Chalcomede, as these events unfolded, continued to try and perform damage control by keeping Morrheus out of the fighting. She lured Morrheus away from the battle and, catching a glimpse of her nude body beneath her flowing robe, Morrheus became desperate to be with her. Chalcomede then pulled out all of the stops. She said she would marry Morrheus, sure – she would even abandon Dionysus and assume the cultural rites of the Indians – but could Morrheus please take off all of his armor, and take a bath? Morrheus said he sure could, and tossed his spear and gear to the side. And up above, on Mount Olympus, Aphrodite made fun of Ares, telling the war god that his burly fighter had surrendered to love, and that love was a more powerful force than war.

Prince Morrheus, then, thinking he was about to finally get together with Chalcomede, bathed in the sea, washing all of the dust and blood off of himself and putting on a linen robe. Morrheus escorted Chalcomede to a flat place in the sand and prepared to rape her there, but, as Chalcomede had been promised, an enchanted snake protected her, twining out of her bosom and hissing in Morrheus’ face. In another Nonnian sentence that’s just too odd to not quote, the poet tells us that Chalcomede’s snaky “defender terrified the man of war [Morrheus]; [the snake] curled his tail round the man’s neck in twisted coils, with his wild mouth for a lance, and many a snaky shaft came darting poison against him, some darting through her uncoifed hair, some from her snakeprotected loins, some from her breast” (35.217-22). I’m not sure of how this worked, exactly, but anyway, snake venom launched out of Chalcomede’s hair and bosom and privates, and hit her assailant Morrheus.

In spite of this important victory over the warrior Morrheus, the Dionysians were still trapped and being exterminated by their enemies, and the god Hermes flew down to help. He made darkness cover the Indian forces, and escorted the battered army of Dionysus out of the city to safety. Not long after the illusion faded, King Deriades saw with fury that he had been deprived of victory, and heard Dionysus’ forces, suddenly beyond the walls, out of reach for the moment and taunting him.

Around this same time, Zeus woke up. Remember, he had been seduced and afterwards eased to sleep by Hera. So, Zeus woke up, and he saw everything that had happened. Initially incensed, Zeus put his underpants back on, gained control of his temper and confronted Hera. Zeus said she couldn’t just keep punishing Dionysus – that Hera’s vendetta had gone long enough. And he asked Hera to go and breastfeed the befuddled Dionysus. This act would not only cure Dionysus of his madness, but it would also would formally signify that Hera was adopting the young deity into her family. Hera would be rewarded for doing so, Zeus promised, as follows: “I will place in Olympos a circle, image of that flow named after Hera’s milk, to honour the allfamous sap of your saviour breast” (35.307-10). Also, Zeus said, he would be furious if Hera refused. And so, convinced by the combination of Zeus’ promise of a special breast milk sculpture and his threats of wrath, Hera hustled down to where Dionysus was, relieved her breasts of their constraints, and offered the wine god a peacemaking mouthful of holy milk, not being happy about any of it. When the battlefield nursing process was complete, Hera hurried back to the heavens to avoid the sight of Dionysus’ forces rallying with the recovery of their leader.

Dionysus himself, restored to his strength and senses thanks to the breast milk of his aunt slash stepmother told his army that he was back and ready to finish things off. They had lost many, Dionysus said, and it left him with a heavy heart. But he would not stop, Dionysus said, until he had beaten Deriades, who was in his mind responsible for so many casualties. [music]

Nonnus’ Dionysiaca, Book 36

Just as Dionysus finished his speech to his diminished but war-hardened troops, up above, in Olympus, a battle also broke out. You may remember in Homer’s Iliad that at the epic’s climax, in Books 20 and 21, Olympian deities also begin going toe-to-toe with one another, and in Nonnus’ Dionysiaca, the same thing happens – the Greek gods momentarily abandon their proxy war among the humans and engage directly with one another. In a series of one-on-one duels, Athena bested Ares using her trademark spear, though her Gorgon-decorated armor was gouged in the contest. Hera fought Artemis, shielding herself against the huntress’ arrows with a fistful of clouds, then knocked Artemis down with masses of hail. Hera taunted Artemis, telling the virginal huntress goddess to get lost – go back to the forest and hunt rabbits with her little bow, go help women in childbirth, and stop trying to fight the more powerful gods.

The Roman Lycurgus Cup, showing Dionysus armed with thyrsus staff. Photo by the British Museum.

Human fighting raged on as the gods contested with each other. On the battlefields of India, Deriades prepared to continue his assault. Deriades told his troops to destroy all of the strange weaponry of the Dionysians – their viny spears and thyrsus staffs, and to behead all of the satyrs. Before the sun set, Deriades vowed, he would have Dionysus in chains, and soon songs would be sung about the victory of Deriades. And with these resolutions voiced aloud, Deriades began a new day of fighting against Dionysus.

With the wine god having rejoined his forces, the Dionysian army was as powerful as it ever had been. A new contingent of female warriors who fought by throwing snakes at their adversaries appeared. Indian elephants fought Dionysian lions and war dogs. Terrified at the commotion, horses killed their riders, and a Bacchant war maiden killed a giant Indian with a sharp piece of rock. The dead were so plentiful that Hades had to open the gates of the underworld more widely, and flotillas of the dead choked the river Lethe.

Climactically, King Deriades fought Dionysus, too. The wine god transmogrified again and again as they battled – Dionysus was living fire, then water, then a lion, then bundles of fruit, then a sapling, then a tree, a panther, a burning log, and a boar. Deriades met him blow for blow and asked why Dionysus wouldn’t face him as himself, and leapt into his chariot. Pressing his attack, Dionysus shot grapevines at Deriades, and soon the Indian King was wrapped thoroughly in vines and leaves. Deriades struggled and writhed, but couldn’t breathe, letting loose a muffled cry, then a faltering hand, and then, tears. Dionysus, for whatever reason, relented, though, removing the confining vines, and moments later Deriades was growling about how he’d be victorious over his hated adversary.

Night fell, and the battle slackened. Dionysus ordered that his army build him a fleet of ships. We are not sure why. The enemy forces responded to this development enthusiastically. The Indian prince Morrheus, who had evidently survived the snake venom shooting out of Chalcomede’s crotch and breasts, told an assembly of Indians that if Dionysus wanted sea battles, he could have them. The Indians, Morrheus said, were adept at naval warfare, after all, and moving the theater of the war to the ocean would confer strong advantages to them. But before this happened, the armies called a mutual truce – a truce of three months so that the dead could be gathered and given their appropriate funeral rites and burials. [music]

Nonnus’ Dionysiaca, Book 37

As the Indian army buried their dead, so, too did the army of Dionysus. And early one morning, Dionysus himself set out to commemorate a fallen warrior, opening a second book of the Dionysiaca almost entirely dedicated to funeral games. We’ve already had a funeral games book back in Book 19. A minor character – the King of Assyria, who briefly hosted Dionysus and company, served as the occasion for Nonnus to dutifully imitate the epic convention of funeral games. But Nonnus, always willing to bring the sputtering locomotive of his plot to dead stops to for the sake of poetic excursions, stops his epic once again, in Book 37, in which we have another full funeral games book, this one for Opheltes. Who is Opheltes, you ask? Why, that’s an excellent question. He’s been mentioned twice up to this point in the story (32.187, 35.374, 378), one of a number of Dionysian warriors killed by the Indian King Deriades, but otherwise, it’s anyone’s guess.6 The funeral games chapter that proceeds in Book 37 is a careful imitation of Book 23 of Homer’s Iliad, in which Achilles stages funeral games for his companion Patroclus – games that include human sacrifices. So, here’s a summary of the second round of funeral games in the Dionysiaca.Whoever exactly Opheltes was, a great number of trees were cut down to serve as his pyre, and locks of hair, too, were set on the departed warrior’s remains. Twelve Indian people had their throats ritually slashed, along with oxen, sheep, and horses. With some difficulty, a fire was started, and after it had run its course, Opheltes’ bones were put in a large tomb. Then, and again this is copied and pasted from Homer, Nonnus tells lengthily of chariot races. For 366 lines, Nonnus racers’ darted around, overtaking and speechifying with one another in characteristically allusion-speckled verse, until one of them was victorious. Chariot racing, as you may know, was the singular obsession of the urban Byzantine world, and so we can safely theorize that chariot racing scenes were of intrinsically greater interest to Nonnus’ original readers than they might be to us.

A surprisingly violent boxing competition followed, and after this, a sweaty and mostly nude wrestling match. Next was a footrace, then an equivalent of a shot put competition, then an archery competition that’s taken partly from the Aeneid, and finally, a non-lethal sparring competition with real weapons. And this last contest wraps up Book 37 of the Dionysiaca, one of the longest books in the epic, by the way. [music]

Nonnus’ Dionysiaca, Book 38

With the games wrapped up, the satyrs and pans returned to caves and grottos, and Dionysus’ human companions made their way back into the forest. The peace of the armistice continued for a while longer, but then Dionysus saw strange signs – first an eclipse at noontime, concomitant with rain and thunder, and flecks of fire falling from above. Then Dionysus saw something else – an eagle with a snake clutched in its talons, which dropped the snake into the river Jhelum. It was a positive omen, the Dionysians agreed. Hermes came to Dionysus and gave him an interpretation – the sun coming back out after the eclipsed signified Dionysus’ victory over the dark-complexioned Indian army. Hermes mentioned the story of Phaëthon, the sun of the chariot driving sun god Helios, and Dionysus said he’d like to hear the story.What proceeds in Book 38 of the Dionysiaca is the embedded tale of young Phaëthon. We’ve heard the full version in Ovid’s Metamorphoses, so I’ll retell it pretty briskly here. The great sun god Helios fell in love with a nymph named Clymene. The two had a baby son named Phaëthon. Nonnus writes a wonderful description of Phaëthon’s childhood, telling us that when Phaëthon was a boy, his grandfather, the Ocean, liked to set the youngster in his belly and then exhale, so that Phaëthon flew up in the air and did turns and somersaults, until the Ocean would catch Phaëthon again and toss him upward, so that the son of Helios was like a kid on an enormous trampoline. As a child, too, Phaëthon liked to imitate his father’s chariot driving. Phaëthon wanted to drive the actual chariot of the sun, and through much pleading and intercession on the behalf of his mother, Phaëthon was allowed to give it a shot. Father Helios gave young Phaëthon a long speech as to what to expect when high above the earth, but in his heart, Helios knew that things were going to end quite badly.

So, up Phaëthon went into the air high above, dizzied at the sudden gulf of air below him and frightened at the rattling and quaking of the chariot. Phaëthon rose high up into the constellations and saw the physical forms of the astrological signs, but he became wildly out of control, causing chaos all over the world below. Zeus, having no choice, had to knock Phaëthon out of the sky with a thunderbolt, and set the world back on course once more. Helios again was at the helm of the chariot of the sun, and the seasons were back in order. As for Phaëthon, he fell into a river and died, and his sisters ringed around him and turned into trees. And that is Nonnus’ version of the story of Phaëthon and the chariot of the sun, one of Greek mythology’s greatest hits, and really told quite nicely in Book 38 of the Dionysiaca. [music]

Nonnus’ Dionysiaca, Book 39

Hermes finished his tale of Phaëthon and Helios just as the armistice agreement came to an end. And the Indian King Deriades saw something foreboding – a fleet of Arabian ships coming to serve as Dionysus’ armada. The Indian King was angry, but resolute – it was indeed a formidable navy, but Deriades said he would still defeat Dionysus. As for Dionysus, he gave a motivational speech to his troops, as well, telling them that he had many powerful allies all over, including in the ocean. Trumpets and pipes were sounded, and a prominent Dionysian lieutenant voiced a long and dire oracle about the impending fate of the enemy army, and then another one prayed for victory for himself and his allies. And then, the battle began.Dionysus’ troops from seafaring cultures fared especially well. His Cyclopes sloshed along the shorelines, hurling boulders and enemy ships. There were many casualties – waves surged with gore and the sea churned with bloodstains. While some perished of battle wounds, others, weighted by heavy weapons and corselets, sank into the seawater as vessels smashed together. The ocean deities Nereus and Poseidon watched the ocean fill with a slurry of dead bodies – bodies that were gobbled up by hungry fish and sank into the mud of the seabed far below. Arrows darted back and forth between ships, some finding their targets and some thunking into masts and cutting through sails, or hitting passing fish. As the fighting intensified, Morrheus, the Indian King’s son-in-law, appeared, darting between ships and attacking people. And while it was no means a one-sided battle, eventually the Indian fleet retreated and beached their ships. King Deriades, although furious, made his way inland from the shoreline, away from the press of Dionysus and the wine god’s waterborne assault. [music]

Nonnus’ Dionysiaca, Book 40

Before the fleeing King Deriades could escape, though, Athena intercepted him, disguising herself as the King’s son-in-law. In this disguise, Athena reprimanded King Deriades for fleeing the battle and told him he could no longer count on having the prince as a son-in-law if the king indeed fled. King Deriades was ashamed, but he explained himself. How could anyone fight Dionysus? Dionysus changed forms – he was human in form, then a panther, then a lion, then a snake, then a bear, then living fire, a boar, a bull, a tree, or a waterspout! How could anyone fight all of these things? But, Deriades said, he wouldn’t give up. He charged back into battle, and believing that his son-in-law Morrheus was at his side, attacked Dionysus.7The wine god was, as ever, undaunted. He transformed into a giant version of himself, pursuing Deriades to a riverbank, where he shot sharp ivy vines at the Indian King, and Deriades, grazed by the strange weapons, dove into the water for safety. But it was too late. Deriades was mortally wounded, and Nonnus concludes Deriades’ extensive presence in the epic with the following cryptic sentence: “Struck with the mandestroying ivy bunch [Deriades] slipt headfirst into [the river], and bridged all that water himself with his long frame” (40.94-5). Suddenly, then, with the help of the goddess Athena, Dionysus had killed the leader of the enemy forces.

Deriades’ queen, and his daughters mourned the Indian King’s passing, pulling out their hair and tearing their garments. In lengthy and allusion-peppered soliloquies, the king’s family gave voice to their grief, anticipating dark days ahead. As for the armies of Dionysus, the wine god forestalled the predictable celebrations briefly in order to build a great collective tomb for the final battle’s casualties, and then to appoint a provincial ruler to replace the defeated Indian King. With this done, the Dionysians broke out into celebrations, naturally, drinking wine, dancing, reeling wildly in great circles, and singing songs of celebration in many languages. In the aftermath of the war, the armies of Dionysus took slaves and booty from their defeated enemies, turning westward with new captives in tow, glittering treasures and strange birds.

Now, a note to you out there listening about the closing books of the Dionysiaca. We are currently about halfway through Book 40, and this epic has 48 books. The central action of the epic – the war between Dionysus and the armies of India, has just been concluded. But there are two more main things that are going to take place. The first sequence of events that will take place will be in modern day Lebanon, in the coastal cities of Tyre and Beirut – these events will take us from our present place in Book 40 up to the end of Book 43. Then, from Books 44-48, we will finally be back in Dionysus’ home city of Thebes in mainland Greece. So, onward to modern day Lebanon for a couple of books.

Dionysus traveled to the fabled city of Tyre, the land of his human grandfather Cadmus. Dionysus admired the beautiful promontory on which the city rested, where the noises of the ocean and ship rigging blended with the rustling of shoreline leaves and grazing animals. Then the wine god explored the city streets, admiring its mosaics, its fountains and streams, and came to a temple of the Heracles. Dionysus voiced hymns to the Greek hero, and abruptly Heracles appeared, and shared a meal with the wine god. Heracles told Dionysus of the origins of Tyre – how it had come about from a primordial people that had risen out of the earth. This same population, Heracles said, had crafted the first ships, and been the first to ever discover Tyre. This people, given prophetic guidance by Heracles himself, had also made appropriate sacrifices upon their arrival to the important city. Heracles also told Dionysus of how the fountains of the city of Tyre had come about. And, grateful for being educated and entertained by the burly Greek hero, Dionysus gave Heracles a special bowl, and the two parted company. [music]

Nonnus’ Dionysiaca, Book 41

Dionysus planted vines throughout the coastal areas of Lebanon, and at this juncture in the epic, Nonnus takes us on a side track to discuss the city of Beroë, or modern day Beirut. Beroë, Nonnus says, also a majestic and lovely city, was home to a unique contingent of early humanity, back when Zeus was a child. In some of the earliest days of the region, there also appeared a nymph – a nymph so ancient that humanity didn’t even exist yet at the moment of her inception. And the city of Beroë, Nonnus writes, was the oldest of all cities. Some, Nonnus tells us, said that Venus was the mother of beautiful Beroë, and the hero Adonis her father, and Nonnus offers some background on this legend. However she came about, Nonnus tells us, the beautiful Phoenician nymph grew up, and so, too, did the central Olympian gods. Zeus wanted to have sex with Beroë, but by this time he had already turned into a bull and raped the Phoenician princess Europa – a story that began Nonnus’ epic 635,000 pages back, and so this wasn’t going to work. There were other things in store for lovely Beroë, and her mother Venus worked to find out the destiny of the nymph, learning that she – meaning in this case the city of Beroë, would have an impressive destiny during the centuries of the Roman Empire, following Augustus’ victories over Mark Antony and Cleopatra in 31 BCE. As a side note, by the way, this little Phoenician coast interlude of Nonnus’ epic lets him sing praises to what were during the fifth and sixth centuries some of the more cosmopolitan and strategically important cities in the Byzantine Empire. A huge amount of the Dionysiaca alludes to or is rooted in old poetic traditions, but here in Book 41, with his origin story of the cities of Tyre and Beroë, Nonnus may well be writing original material to praise some of the coastal gemstones of the early Byzantine Empire. [music]Nonnus’ Dionysiaca, Book 42

A terracotta lekythos from about 440 BCE showing Poseidon. Nonnus’ tale of Dionysus fighting Poseidon is one of the unusual features of the Dionysiaca.

The woodland deity Pan, seeing Dionysus so lovestruck, offered him some counsel. And, charged with advice, Dionysus approached Beroë again, telling her he was just a countryman from Lebanon, and asking – wouldn’t Beroë take him on as a laborer? In a series of not-at-all transparent sexual innuendoes, Dionysus promised Beroë,

The furrows are teeming, when dew falls on the land. . .Take me as planter. . .that I may plant that lifebringing tree, that I may detect the half-ripe berry. . .I can join the male palm happily with the female. . .I have no need of wealth – my wages will be two apples and one bunch of grapes. (37.289-90, 299-300, 305-6, 311-13)

Dionysus’ romantic overture, however, did not inspire Beroë with any affection in return, as the naïve nymph didn’t understand its double entendres. Dionysus tried other approaches, endeavoring to get to know Beroë’s father, and then later simply appearing before her in his own form and telling of his great victories in the east. Dionysus said he’d renounce everything – his divinity – to be with Beroë. Dionysus said he was a lot better catch than Poseidon – Dionysus had wine – what was Poseidon going to bring her? Saltwater? Continuing his innuendoes, Dionysus said she’d much more enjoy a thyrsus staff than the prong of a trident. He enumerated reasons she ought to be with him, but Beroë wasn’t interested.

Then Poseidon voiced his appeal to the nymph, offering her the boundless ocean as her home. But Beroë rejected Poseidon, as well. Aphrodite decided to intervene, proposing a contest between the two lovers. Dionysus and Poseidon agreed – there would be a battle to decide who would marry Beroë, the Phoenician nymph and mother deity of modern-day Beirut. [music]

Nonnus’ Dionysiaca, Book 43

The maiden nymph Beroë preferred Dionysus out of the two captains who would now go to war over her. This, regrettably was not relevant to the two gods involved in the love triangle, who marshaled their troops for battle, Dionysus armoring himself with ivy vines and brandishing his trademark thyrsus staff, and Poseidon hefting his trident. Dionysus then voiced his umpteenth pre-battle motivational speech in the epic, promising that he would win, and that he would be generous and let Poseidon sing at the wine god’s wedding with the nymph Beroë. Then, Poseidon offered his own rousing monologue predicting his own victory and cautioning Dionysus, and as Nonnus puts it, Poseidon “shook with his trident the secret places of the sea, roaring surf and swelling flood flogged the sky with booming torrents of water” (43.192-4). The lieutenants of Dionysus and Poseidon also prepared to battle one another, and soon, the fighting began in earnest.Naiads fought with dryads. Bacchants fought with nereids. Satyrs sparred with the forces of Poseidon, and bodies of water smashed together. Elephants fought with seals. Seeing all of the sudden chaos, a sea nymph prayed to Zeus to stop the Olympian civil war before things got any severer. And fortunately for everyone, Zeus heard the prayer, and he stopped the war. Zeus said that the nymph Beroë would marry Poseidon. And Dionysus, crestfallen, but steeled with courage by a special trumpet blast from Zeus, rallied himself.

Poseidon and Beroë were then married. And I should repeat that this whole ridiculously extraneous sequence of events in modern day Lebanon was likely written so that Nonnus could sing praises to the ancient city, which by his lifetime was the site of an important Roman law school.8 In the closing of the lengthy sequence on the city of Beroë, the deity Cupid, in order to console Dionysus, told the wine god that Dionysus would have a wonderful wife soon – just not Beroë, and, evidently comforted, Dionysus turned westward. And finally, after a full 27 books abroad, the wine god made his way back into the Aegean world. [music]

Nonnus’ Dionysiaca, Book 44

In antiquity, ancient Greek writers and artists really liked the theme of Dionysus returning from the east with a retinue of exotic warriors and attendants, a group called the thiasus. The tale of Dionysus’ return is one we’ve heard before in our podcast. The wine God’s return to Thebes is the main narrative of Euripides’ play, the Bacchae. In the Bacchae, Dionysus arrives home, he is disrespected by the impious Theban king Pentheus, also Dionysus’ cousin, and Pentheus ends up being killed by Dionysus’ followers. This return story, or homecoming saga, or nostos, to use the ancient Greek word, is also the plot of Homer’s Odyssey – a powerful leader arrives back at home, he is disrespected, and then he reasserts himself with extreme violence. So, just as the last three books of the Dionysiaca – Books 41-43 – branched off into a miniature saga about the nymph Beroë in Lebanon, the books we’re about to cover, and these are Books 44-6, retell the events of Euripides’ play the Bacchae, a work written around a thousand years earlier.So, again, Dionysus had come back to his home country of Boeotia on the Greek mainland – specifically, the country around Thebes. And as celebrants of the wine god honored his arrival back on native soil, the prideful King Pentheus, son of Dionysus’ aunt Agauë, armed a city militia and barred the town gates against the returning hero. Soon, the wine god’s Bacchants and satyrs were stalking around the perimeter of the walls, and the city rumbled in anticipation of dark events to come. King Pentheus’ mother Agauë, who had seen her son usurp the Theban throne from her old father Cadmus, was especially uneasy. Pentheus himself vaunted about his impending victory, promising that he would burn Dionysus to a crisp just as Zeus had incinerated Dionysus’ human mother Semele.

These harsh and distasteful threats were not lost on Dionysus, who said prayers to Zeus and Semele, and the wine god’s requests for divine aid did not fall on deaf ears. The first to offer tangible aid was none other than the queen of the underworld Persephone, such that a host of furies rushed out of Hades to infiltrate the palace at Thebes. There, rather than instigating direct violence, the furies assailed the minds of King Pentheus’ aunt and his mother. [music]

Nonnus’ Dionysiaca, Book 45

The blasphemous King Pentheus’ mother was again named Agauë, and Agauë dashed out of the Theban palace in a frenzy toward the nearby mountains, set on rebelling against her son, stoked to madness by the prompting of the furies. Agauë announced that she would now pay due heed to Dionysus. And as it turned out, the women of Thebes weren’t the only ones to fall under sudden enthusiasm for Dionysus. The elderly prophet Tiresias, along with old King Cadmus, had also twined ivy in their hair, much to King Pentheus’ ire. Pentheus expressed his disapproval, but the prophet Tiresias reprimanded Pentheus in turn. You had to honor Dionysus, said Tiresias, offering a story about Dionysus overpowering an entire Phoenician fleet. But Tiresias’ words of caution and counsel did not convince the fearsome Pentheus to adopt a more welcoming attitude toward the returning Dionysus.Instead, the blasphemous Theban king ordered his army to scour the woods and return with Dionysus in chains, along with Pentheus’ mother Agauë. The Theban army thundered into the countryside around the city and captured many of Dionysus’ female worshippers, bringing them back into the city and putting them in dungeons. Then, in a curious sequence, the captured Maenads began to twirl and move in rhythm, and they shook off their shackles and actually danced their way to freedom. While that particular scene sounds like it could have come from The Sound of Music, a moment later, Nonnus’ tale takes a different turn. Dionysus’ ecstatic followers, having danced their way out of Thebes, threw themselves into beast hunts in the local pastures and wilderness, killing animals and tearing them apart with their bare hands, kidnapping children, and variously making wine blossom and gush from all over the uplands of Boeotia. The city of Thebes shook with the distant thunder of the celebrants in the hills, and Dionysus came for King Pentheus.

Fire roared up all over Pentheus’ quarters, raveling around his garments in ropes. The King tried to get his servants to quench the flames, but water only made the flames burn more intensely, and soon the whole Theban palace was engulfed. [music]

Nonnus’ Dionysiaca, Book 46

King Pentheus of Thebes, his palace roaring in flames, and the environs of his capital city having erupted into chaos, knew he was in trouble. But still, Pentheus was unrepentant. The Theban King and the god of wine sparred with one another verbally for a time. And slowly, Dionysus took over the Theban king’s mind. Dionysus convinced Pentheus to dress as a Maenad – to wear a female celebrant’s robe and veil, to put on women’s shoes, to seize a thyrsus wand and hurry out into the hills to join the celebrations. What followed next was not pleasant for the arrogant Theban king.Pentheus first saw the celebrations taking place around the city. Pentheus was prodded around the walls of his city. He was affixed to the top of a fir tree compelled to dance himself. And then his mother and her associates saw Pentheus. Maddened under the influence of Dionysus, they mistook Pentheus for an animal, and when he came back down to the ground, in spite of his remonstrations, King Pentheus’ mother Agauë and the other Maenads tore him to pieces. Thinking that they’d successfully killed a lion, Agauë and her companions brought the remains of Pentheus back to Thebes, where old grandpa Cadmus, shocked, understood what had happened. Afterward, Nonnus writes, “Dionysus was abashed before the hoary head of Cadmos and his lamentations; mingling a tear with a smile on that untroubled countenance, [Dionysus] gave reason back to Agauë and made her sane once more, that she might mourn for Pentheus” (46.270-3). It’s quite an odd narrative moment – Dionysus has just caused his cousin to have a horrifying death and his aunt to be the killer, and as we look for a hero or even simply any moral coherence at all, at this extremely late moment of the epic, we only see several different traditions ham-handedly stitched together into one narration.

Poor Agauë was devastated at what Dionysus had made her do, wishing for madness again, or some consolation for the horror that she now faced. Her sister Autonoe comforted her but said she’d prefer death, as well, rather than live with the atrocity they’d committed. Dionysus, who always had recourse to one trademark tool, gave them some wine to make them forget their troubles. And then, having – uh – heroically caused his aunts to dismember his cousin and then splashed some wine their way to make them forget the blood splattering tragedy, Dionysus continued his westward course, and went to Athens. [music]

Nonnus’ Dionysiaca, Book 47

The last couple of books of the Dionysiaca allow Nonnus to share a few final legends about the wine god that were out there by the fifth century CE – most importantly Dionysus’ marriage to the Cretan princess Ariadne. These are also extremely long books by the epic’s standards, and ones filled with many events, so sit tight for just a little while longer and I’ll tell you the predictably long coda to this already long story.Dionysus and his throng burst into the city of Athens in full color. Athens erupted into song and dance, and both the ancient Zagreus and his new incarnation Dionysus were celebrated. As festivities broke out, Dionysus gave wine to an old Athenian named Icarios. As the days passed, old Icarios shared the gift of wine further, and other Athenians wondered where the miraculous wine had come from. The Athenians drank and drank, until finally, overtaken by alcohol and suddenly made violent, they seized Icarios and butchered him with weapons and tools. When the drunken Athenians awoke later, they repented the murder and buried him. Icarios’ ghost visited his daughter, and learning of her father’s awful fate, she mourned him desperately, until, at a loss for anything else to do, she hung herself. Her dog circled her dead body afterward, and when some passerby happened upon her and buried her, the dog helped dig her grave. Zeus, pitying the girl, made her into a constellation.

After giving Athenians the – somewhat sketchy – gift of wine and drunkenness, and continuing his general pattern of leaving carnage and loss behind him, Dionysus ventured forth from Athens to the island of Naxos. There, he found the abandoned Cretan princess Ariadne. As you may know, in a separate myth cycle, Ariadne is the Cretan girl who helps the Athenian hero Theseus get through the labyrinth on the island of Crete and defeat the minotaur, after which Theseus, northward bound back to Athens, leaves Ariadne behind on the Aegean island of Naxos. Whatever you make of that legend, it was connected to another legend of Dionysus finding Ariadne there, abandoned and forlorn on Naxos and marrying her – and it is to this second legend that Nonnus hitches his epic for a moment.

So, Dionysus came to the island of Naxos, and saw the abandoned Ariadne there. Exclaiming voluminously on the beauty of the girl before him, Dionysus became so garrulous that he woke Ariadne up. Ariadne realized she’d been abandoned by Theseus, and looked for his ship. She bewailed her abandonment and wished again for sleep, and after a speech of a mere hundred lines, Dionysus finally had to curtail Ariadne’s lamentations, step in, and say something. Dionysus promised Ariadne a marriage second to none, and eternity in the constellations above, and Ariadne intuited that this would indeed be quite a nice match, and so she accepted, and they were married.

Then the narrative takes a quick turn. On the mainland, a certain population of Greeks in Argos weren’t paying proper heed to Dionysus. Angered, the wine god caused them to become insane, and Argonian mothers began butchering their children and babies. Now, Argos was traditionally the home of the very ancient Greek hero Perseus, and Hera was one of Argos’ major deities. And even though back in Book 35 Hera had suckled Dionysus with her breastmilk and promised to let bygones be bygones, most of the way through Book 47, Hera proved that she still hated the young wine god since her husband had raped Dionysus’ helpless human mother. Hera, then, rallied the Argonians and their native hero Perseus against Dionysus. As to why Hera did not also hate Perseus, who himself was the son of the human woman Danae, whom Zeus had also raped, Nonnus does not elaborate. The armies of Dionysus and the city of Argos squared off, and the two half-brothers Dionysus and Perseus sprayed one another with threatening prefatory speeches.

Once combat began it was clear that Dionysus was the more powerful of the two heroes, and Perseus flapped off with his flying shoes and went and attacked Dionysus’ wife, turning Ariadne to stone with the head of Medusa – one of Perseus’ signature weapons. Before the scale of the violence could escalate any further, though, the god Hermes forestalled the fighting, encouraging the half-brothers Dionysus and Perseus to sheathe their weapons. The forces of Dionysus and those of Argos undertook peacemaking rites, and the war was stopped before it could really begin. [music]

Nonnus’ Dionysiaca, Book 48

Well, I wish I could tell you that in the final book of the Dionysiaca, Nonnus writes some tremendous, symphonic closing that helps draw the disparate epic together. But as a matter of fact, it’s quite the opposite – Book 48 of the epic is a frantic, incongruent mishmash of closing episodes, almost a thousand lines in length, that I’ll go through quickly now.The goddess Hera, 48 books into the Dionysiaca, still had it in for Dionysus, and she summoned some giants to pursue and kill the wine god. And so up from the earth rumbled a population of giants, and Dionysus fought with them, attacking with vines. [short music]

A Pompeian painter’s depiction of Hera shows a complex and ambiguous expression in a detail of the Marriage of Zeus and Hera.

Off Dionysus sped for more adventures. He had learned of a beautiful nymph who was ignorant of all things related to love, who, like so many other virginal huntresses and hunters in Greco-Roman mythology, dashed around in moccasins killing animals but was not interested in romance. Her name was Aura. One warm afternoon the huntress Aura took a snooze by a laurel bush and had a dream – a disconcerting dream that inasmuch as she valued her rugged woodland independence and chastity. The latter, at least, she learned from her dream would soon be a thing of the past. Some time later, the nymph Aura bathed in forest pool with the most famous of all virginal huntresses, the goddess Artemis. And the nymph Aura, who’d perhaps spent a bit too much time skinning things and not talking to people, proved less than diplomatic in her words to the chaste Artemis. Looking at the goddess Artemis’ evidently large and full breasts, Aura said Artemis certainly didn’t look chaste – Artemis’ bosom looked motherly. Young Aura showed off her leaner and more sinewy form, indicating that she – Aura – was really pulling off a better version of the virginal huntress look than Artemis was.

Artemis, we learn later, couldn’t just smite the impolite youngster, since Aura was the offspring of Titans, so Artemis went to the dark goddess Nemesis and asked for help – wouldn’t Nemesis turn the impertinent young Aura to stone? Nemesis said she couldn’t do this, but that she could make sure Aura lost her virginity. Nemesis saw to it that Dionysus was shot by an arrow from the god Eros, and off Dionysus went, discoursing to himself on the subject of unrequited love and soon finding himself tromping through a flowery meadow. There, Dionysus fell asleep, and he dreamt of Ariadne. Ariadne asked him if he’d forgotten about her, and said he’d inherited his father’s trademark lust. Still, Ariadne volunteered to help Dionysus court Aura by giving him a weaving spindle to give to the huntress. In a replica of events that took place back in Book 16 of the Dionysiaca with a different virginal huntress nymph, Dionysus made a stream change from water to wine, and when Aura fell into intoxicated slumber, Dionysus raped her. It’s actually worse than that, as the god Eros helped Dionysus find the unconscious Aura, and Eros emphasized that Dionysus should violate her while she was unconscious, after which Dionysus actually tied Aura’s hands and feet together and then raped her. Afterward, Dionysus untied the nymph and abandoned her, rejoining his satyrs.

Aura awoke, both furious and sickened at what had happened. And she went on a rampage, killing various local herdsmen, workmen and vintners – anyone tangentially connected with Dionysus. Then Aura attacked an altar to Aphrodite, and later, back in the forest, she railed against all of the gods. She wanted to die, or at least to end the nightmare of her pregnancy, even if the results were gruesome. But things grew worse instead. Artemis came to her and taunted the pregnant girl, making fun of the way she looked, of the fact that she was raped – even that Dionysus had just abandoned her.

Some time afterward, in mountain peaks, Aura cursed both Artemis and Athena, and in turn Artemis made Aura’s childbirth long and painful. The huntress nymph Nicaea, whom again Dionysus also had raped while she was unconscious back in Book 16, came to the poor nymph Aura and comforted her with fellow feeling, but Artemis continued her taunts brutally, even as Aura gave birth to twins. Dionysus then appeared and congratulated both the huntresses on being raped in their sleep by him, and he asked if Nicaea might take care of the twin boys, since Aura was likely to just murder them. As it turned out, though, Aura put her twins in a lion’s den to be eaten, and when the lions wouldn’t touch them, she tossed one of them off of a cliff to his death. The other baby was seized by the goddess Artemis, and as for Aura herself, she threw herself into a waterway and was transformed into a fountain.

The other baby was nursed by Dionysus’ remaining victim Nicaea, and this boy grew up as Iaccus, being a resident thereafter of the pilgrimage site of Eleusis. Iacchus, by the way, was an important figure in the ancient Greek Eleusinian mysteries – we’ll come back to that a little later – and Nonnus writes that following the child’s arrival at Eleusis, “the Athenians beat the step in honour of Zagreus and [Dionysus] and Iacchos all together” (48.966-7). Dionysus’ final act before being made a fully-fledged citizen of Olympus was making a constellation for Ariadne, and following this, as Nonnus writes, “after the banquets of mortals, after the wine once poured out, he quaffed heavenly nectar from nobler goblets, on a throne beside Apollo, at the hearth beside [Hermes]” (48.974-8). And the epic here closes with Dionysus, having completed his long and frequently sketchy adventures, being formally made one of the Olympians. And that’s the end. [music]

Challenges for Readers in the Dionysiaca: Allusiveness