Episode 98: The Life and Works of Saint Jerome

Polyglot Jerome (347-420) had a gigantic impact on all subsequent Christian history, leaving behind a huge body of works, including the Latin Bible.

| Read Transcription | References and Notes |

| Episode Quiz | Episode Song |

| Episode on Spotify | Episode on Apple Podcasts |

| Previous Show | Next Show |

The Life and Works of Saint Jerome

Gold Sponsors

Andy Olson

Bill Harris

David Love

Jeremy Hanks

John David Giese

ML Cohen

Olga Gologan

Silver Sponsors

Alexander Silver

Boaz Munro

Chad Nicholson

Francisco Vazquez

Hannah

John Weretka

Le Tran-Thi

Michael Sanchez

Oscar Lamont

Anonymous

Steve Baldwin

Sponsors

A. Jessee Jiryu Davis

The Hillguardian

Aaron Burda

Alysoun Hodges

Angela Rebrec

Ariela Kilinsky

Basak Balkan

Benjamin Bartemes

Bob Tronson

Brian Conn

Carl Silva

Chief Brody

Chloé Faulkner

Chris Tanzola

Chuck

Cody Moore

Deanna Bowman

Derick Varn

DOUG’S BIGGEST FAN

DOUG’S BIGGEST FAN

Ellen Ivens

Eric Carpenter

Euripides

EvasiveSpecies

Garlonga

Jason Barger

Joe Purden

John Barch

Jonathan Thomas

Jonathan Whitmore

Joran Tibor

Joseph Maltby

Joshua Edson

Kyle Pustola

Laura Ormsby

Laurent Callot

Leonie Hume

Lisset Salazar

Maria Anna Karga

Marieke Knol

Mark Griggs

Mr Jim

Murilo Ramos

Oli Pate

Riley Bahre

Rod Sieg

Ruan & Nuraan

Rui Liu

Sonya Andrews

Stephen Connelly

Steven Laden

Sue Nichols

Susan Angles

Tom Wilson

Valentina Tondato Da Ruos

Vika

Vladimir Visnjic

One of these ways was the monastic movement. Monasticism, and religious desert hermits, or eremites, had become sources of intense interest to Christians by the middle of the 300s. When the most famous of all of these desert hermits died in about 356, a distinguished bishop wrote a biography about him, and the book in question, Athanasius’ Life of Antony, became widely popular. Jerome discovered this biography at a formative time during his intellectual development, and as a result, Jerome himself wrote three different biographies of other desert hermits. In the mid-370s, Jerome even tried his hand at living an ascetic lifestyle in the desert for a couple of years – an area called Chalcis, near modern day Aleppo, Syria.

While the 300s saw Christian zealots like Jerome homesteading in the deserts of Egypt and Syria, this same century also saw monastic activity springing up in Roman metropolises. Blue blooded Christian converts, if their devoutness had reached a certain pitch, were converting mansions and estates into meeting houses and priories – enclaves where pious and likeminded believers could read sacred literature, discuss doctrines, and lead lives that they felt were consonant with Biblical teachings. Such urban sanctuaries were a large part of Jerome’s world in the 380s when, fresh from his time in the Syrian desert, he traveled to Rome to offer aristocratic patrons his services as a counselor, minister and scholar.

Saint Jerome led a colorful, eventful life, sometimes made more eventful by the fact that he had an extremely strong personality, which from time to time landed him in hot water. This strong personality, which comes across amply over the many tracts and letters he left behind, has led to Jerome having a checkered reputation in later Christian history. Martin Luther, who was ambivalent about some of the accomplishments of Jerome’s generation, wrote the following on Saint Jerome: “I cannot think of a doctor [of the church] whom I have come to detest so much, and yet I have loved him and read him with the utmost ardour.”1 Luther also famously concluded that Jerome was “obviously in need of a wife since with a female companion he would have written so many things in a different way.”2 It is an especially funny jab if you know the basics of Saint Jerome’s writings, which you will by the end of this program. Central to Jerome’s ideology is a very negative attitude toward sex, and a connected idolization of virginity and chastity – something that he shared with many in his generation of Christians. Martin Luther, knowing this, invites us to imagine that Jerome might have been a somewhat more relaxed and compassionate theologian if he had shared his life, and bed, with a loving spouse.

On the whole, since the fourth century Jerome has inspired ambivalent responses like the one from Martin Luther we just heard – absolute respect for the visionary translation work that Jerome undertook, and his encyclopedic knowledge of scripture and patristic history on one hand, and on the other hand, apprehension at Jerome’s abrasive personality, his fixation on sex and chastity, and his sanctimoniousness. Saint Jerome was a translator and exegete second to none, but he could also enter theological debates with the savagery of an ancient Roman muckraker, and seemed to have no trouble telling regular workaday Christians that he, a chaste scholar who had devoted his life to the church, was a cut above them. While Jerome’s austerity and elitism can make us wince from time to time today, his energy, individualism, and ingenuity led him to do work that was tremendously useful to posterity. So let’s focus for a moment here at the outset of this program, and spend about a minute learning about what Saint Jerome is famous for.

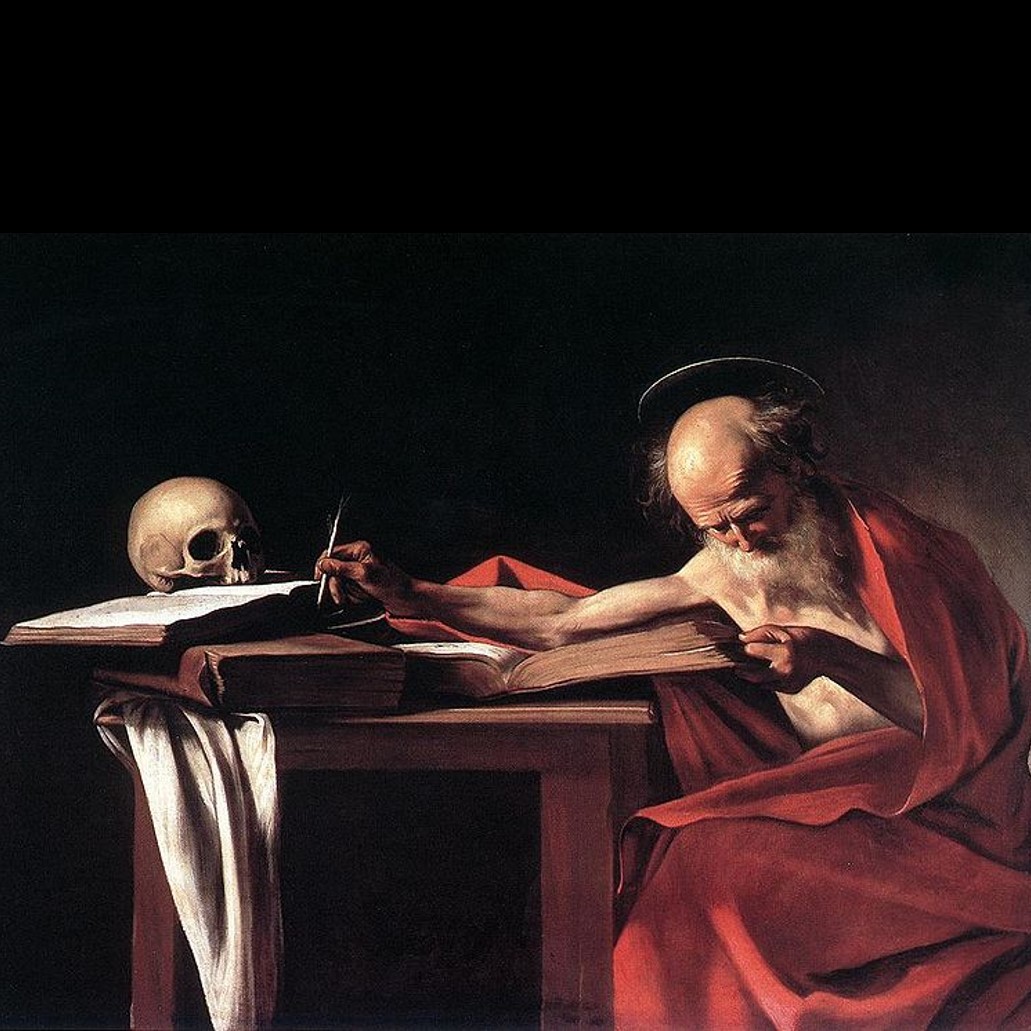

Giorgio Schiavone’s Saint Jerome (c. 1456-51) shows a stooped and bookish theologian worn with the cares of a busy career.

To stick with Saint Jerome for now, Jerome’s life is a window into a revolution within Christianity itself that happened during the late 300s. While we approach Late Antiquity with the general sense that Christianity was always getting bigger and bigger, learning the basics of Jerome’s biography helps us understand how, and where it was getting bigger, and how it was evolving as it grew during the crucial fourth century CE. Though he was above all things a bibliophile and linguist, Jerome was also a gutsy and ambitious networker, seeking out and forming professional relationships with major metropolitan bishops and even the Pope, not to mention falling into the occasional acrimonious rivalry. So let’s begin today’s program by spending thirty or forty minutes learning about Jerome’s life – not only the biography of the Latin church doctor himself, but also the cultural sea changes of the 300s happening within Christianity, how Roman patronage networks were evolving to support house ministers and churchmen, how rifts in the church were fueling regional antagonisms and theological works, and how all of this fits into the story of the late Roman Empire. [music]

Saint Jerome’s Early Life and Education

Saint Jerome was born around the year 347.3 He spent his early years in a small community called Stridon, somewhere in the eastern reaches of modern-day Slovenia or northwestern part of Croatia. This region, on the border between the Roman provinces of Dalmatia and Pannonia, was fairly close to the Limes Germanicus, but during Jerome’s youth, the Empire’s major confrontations with northern barbarians were happening against the Alemanni in Gaul, rather than around the northern Adriatic rim.4 Jerome’s parents were wealthy Christians, and in one tract Jerome later recollected “the memories of my childhood: how I ran about among the offices where the slaves worked; how I spent the holidays in play; or how I had to be dragged like a captive from my grandmother’s lap to the lessons of my [tutor].”5

Joachim Patinir’s The Penitence of Saint Jerome (c. 1512-15) in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Saint Antony is the figure in the panel on the right, being tormented by monsters as he often is in portraiture. The scenery, perhaps more striking than any figure in the triptych, offers a sense of the many places in which the theologian lived and worked.

While Jerome disliked the notoriously harsh and repetitious aspects of early childhood education as it existed in the Roman Empire, his basic tutelage in grammar, literature, and oratory as a young man were only the beginning of his long education. Whatever Jerome’s parents did to earn their living, they were evidently wealthy enough to send the young man to Rome, where he studied alongside several other youths from his region in some of the empire’s finest schools. As had been the case in the ancient world for over eight centuries of recorded history, a literary and philosophical education were foundational to any up-and-coming Roman who wanted success and employability, and so Jerome and his friends would have mastered the extant canon of Latin literature while being trained in all the fine points of grammar and usage by a famous scholar called Aelius Donatus. Jerome, though a Christian, learned plenty about pagan culture during these early years. Some of Jerome’s surviving works reveal a dizzying knowledge not only of Latin classics, but also ancient Roman literary scholarship.6 In a later work, Jerome admits that it wasn’t all studiousness during his teenage years in Rome – he also enjoyed the entertainments of the capital, but, being Christian, he went on Sundays to apostolic shrines and monuments to martyrs. And in addition to honing his capacities as a reader and writer of the finest Latin, and generally being a young Christian student in Rome, Jerome also, as the 350s stretched into the 360s, made some powerful friends – senators who were also Christian intellectuals, and other noblemen involved with the church to varying degrees who would serve as important connections on down the road.Some time during the 360s – perhaps around the age of 20 – Jerome’s ambitions led him to make his way to the city of Trier, in the western part of modern-day Germany, near the border with Luxemborg. At first glance, this seems like an odd place for a young man to go to make a career, being a spot in the northeast of the Gallic provinces, in a territory where Rome had just wrapped up a major war against the Alemanni. Trier, though, was during the 360s one of the more important cities in the Empire, having been the seat of one of the tetrarchs since the time of Diocletian, and its continued strategic importance made it a center of military operations over the 360s and 370s. The Roman emperor Valentinian, after 367, spent a great deal of time in Trier, and it was likely Jerome’s intention to obtain an academic or bureaucratic post in the region, thus securing an income and the cachet of an imperial appointment. But instead, something else happened.

Joos van Craesbeeck’s Temptation of St Anthony (c. 1650). Saint Jerome, like so many others in his generation, was electrified by the story of Saint Antony’s tenure in the desert – his staunch asceticism, his temptations by Satan, and his ultimate triumph.

For Jerome, the decision to abandon the plush career of a Roman Christian aristocrat and to embrace a more monkish and scholarly existence came at a heavy price. Jerome not only gave up a certain degree of job security and various career paths. He also resolved to relinquish reading and revering some of the pagan authors he had adored over his teenage years. Jerome himself, in a letter he wrote to a Roman noblewoman called Eustochium as an older man – we’ll hear more about her later – wrote about deliberately changing his reading habits in his early twenties. Jerome’s 22nd epistle describes how even after he resolved to practice a more zealous and self-denying form of Christianity, it was difficult for him to part ways with his beloved pantheon of classical authors – he reports fasting and then binging on Cicero and Plautus, and finding the biblical prophets drab and uninteresting by comparison. Ashamed at his lack of resolve, in this same letter Jerome records falling ill and then having a vision, the climax of which was a resolution to never read any pagan authors again, on pain of damnation and torture. This whole story, by the way, was an exaggeration told to ingratiate his pupil and patron – Jerome actually continued to read and cite classical pagan literature throughout his theological career. While he may not, then, have momentously sworn off Cicero for Christ, as he alleges doing in this important letter, it’s still very safe to say that some time in his early 20s – around the year 370 or thereabouts, Jerome transitioned from being a workaday Roman Christian, with an evenhanded interest in pagan as well as Christian culture, to embracing a more intense and exclusionary form of his parents’ religion. [music]

Saint Jerome’s Growing Interest in Monasticism

After 370, Jerome, then, became swept up in a broad cultural movement within fourth-century Christianity. As we learned a few episodes back, desert hermits, toward the end of the 200s and the outset of the 300s, had begun to inspire imitators and whole monastic communities, first in Egypt and then, increasingly, elsewhere. By 362, the influential bishop Athanasius of Alexandria had published his famous Life of Antony, an exceedingly popular and important volume in fourth century Christian history. But not everyone idolized Christianity’s monks and ascetics. A generation after Athanasius’ famous book about the pious Antony, in 417 – a few years before Jerome died – the Roman poet Rutilius Namatianus recorded sailing past the island of Capraia, between Corsica and Italy, and he castigated the monks who lived there, asking “What silly fanaticism of a distorted brain is it to be unable to endure even blessings because of your terror of ills?”8 Christian monasticism, put simply, didn’t impress everyone when it first began to proliferate. It was a subset of Jerome’s own generation, then, in the half century between 370 and 420, who endorsed and embraced the nascent Christian monastic movement, throwing themselves wholesale into ascetic and exclusionary Christianity while the rest of the world, both Christian and pagan, looked on with curiosity and sometimes outright scorn.Following his conversion from regular old Christian to extreme ascetic Christian, Jerome left Trier in the early 370s, hungry for the zealous asceticism that was sweeping through various enclaves of Christianity during the late 300s. His first stop was northern Italy, where small monastic cells, often based in households, had become fashionable in Christian circles in Vercelli, up near Milan, and in communities on the north rim of the Adriatic, like Aquileia. Common to the monastic movement, from Saint Antony onward, was a commitment to Nicene Christianity over Arian Christianity, the most important theological controversy of the fourth century. In other words, the ascetic Christians of Jerome’s generation weren’t just generic Christians – the monastic movement had at its heart the Trinitarian and consubstantialist doctrines of the council of Nicaea, rather than the Arian notion that Jesus was younger than and lesser than Yahweh. Enforcing Nicene Christianity over Arian Christianity, then, was one of the propellants of the monastic movement. The Christian ascetics of Jerome’s generation were a sect apart not only because of their austere lifestyles, but also because they subscribed to what they understood as the only correct form of Christianity. As Jerome’s biographer Stefan Rebenich puts it, after Jerome’s religious awakening in Trier, “All those not willing to endorse his interpretation of a Christian life were ostracized, [including] the rustic inhabitants and lukewarm Christians of his hometown of Stridon.”9 While Christians had always rankled pagan critics due to Christianity’s plucky assertion that it, and only it, was correct, Christians like Jerome went double or nothing, imagining their sect of the religion, and their ascetic self-conduct, as the only correct Christian path within Christianity itself.

Northern Italy, as it turned out, would not satisfy Jerome’s newly awakened passion for a monastic lifestyle. He packed up his heterogeneous library and headed eastward, intending to join other would-be Christian ascetics in Jerusalem. Before reaching Jerusalem, though, he arrived in Antioch. There, Jerome had a formative and fateful meeting. In Antioch, Jerome made the acquaintance of a man named Evagrius, whom scholar Megan Hale Williams calls Jerome’s “literary and ascetic surrogate father.”10 Evagrius was rich and well-educated, having been the person who’d undertaken the Latin translation of Athansius’ Life of Antony – the same translation that had likely reached Jerome a few years earlier. Jerome evidently got along well with Evagrius, taking advantage of his patron’s library and learning more Greek and more about the theological disputes of the eastern bishoprics. While Jerome’s sanctimoniousness could be as revolting during his own lifetime as it can to us today, he seems to have been an absolute whiz kid with languages, and furthermore had the capacity to consume and remember works of theology at a massive scale. In Antioch, his patron Evagrius helped young Jerome put these considerable talents to use. And after his stay in the city of Antioch, fortified with a greater education and religious zeal than ever before, Jerome jumped onto the monastic bandwagon in earnest, and undertook his own foray into desert asceticism. He was in his mid-twenties in the early 370s, and the next few years would be among the most formative in his life. [music]

Saint Jerome’s Years in Syria and Constantinople

Initially, Jerome had intended to spend his time as a desert hermit closer to Jerusalem. But the location that Jerome opted for, under the influence of his new patron Evagrius, was called Chalcis. About 15 miles southwest of modern-day Aleppo, and 50 miles inland from Antioch, Chalcis was likely the most isolated spot Jerome had inhabited up to that point in his life. But in comparison to say, the Inner Mountain of Saint Antony, Chalcis was a sort of entry-level hermitage, relatively close to the city of Beroea (again, modern-day Aleppo), which was a large Roman town with a bishop and all the amenities of imperial Roman civilization.

The archaeological remains of Kellia, or “the cells,” showing multiple structures honeycombed with rooms for monastic habitation. This was a very early monastic settlement in Egypt, and it demonstrates how desert monks lived and worked together sustainably. Photo by Geo24.

Whatever Jerome’s actual accommodations near modern day Aleppo were like, ambitious networking wasn’t his only pastime. By his late 20s, Jerome had also begun something instrumental to his later career, and this was learning Syriac and Hebrew. But eventually, in spite of all the learning he was doing there, Jerome soured on rural life during his tenure in the Syrian countryside. As Jerome networked with key theologians of the 370s, his positions on Christian doctrine became firmer and more strident, sometimes alienating him from more relaxed Christian neighbors who shared neither his exclusionary Nicene doctrines, nor his inclinations toward religious tribalism. Rifts with locals eventually drew Jerome away from the Syrian interior, and, his rather tame hermitage reaching its conclusion, Jerome returned to the eastern metropolis of Antioch.

In the city Antioch, Jerome was formally made a priest, and following his lifetime passion for learning, he attended the lectures of a theologian named Apollinaris of Laodicea. It was around this time – in the mid to late 370s – that Jerome may have discovered a second passion – a passion for scriptural exegesis. For theologians like Jerome and Augustine, if Biblical verses contradicted their theology, it was easy enough to argue that such verses meant something else, in much the same way that modern literary scholars sometimes read texts against the grain for the sake of making certain kinds of arguments. The exercise of interpreting biblical verses, to an energetic and combative intellect like Jerome’s, would prove a stimulating arena for criticizing other theologians and hardening his own ideology throughout the next three decades of his life. Ordained as a priest, then, and partnered with his powerful patron Evagrius, Jerome might have simply remained in Antioch, living in relative security under the sympathetic patronage network he’d found there. But in 380, when Jerome was in his early 30s, one of the most important events in Christian history occurred. This was the passage of the Edict of Thessalonica, ratified by the emperor Theodosius and his colleagues on February 27th, 380 CE – an edict that declared that only Nicene Christianity was correct and permissible, and that all other forms of the religion were heretical.

This edict was good news to Jerome. Following the passage of the Edict in 380, Jerome traveled to Constantinople, probably to politick on behalf of a Nicene bishop whom he had known in Antioch, and whom he believed would benefit from the Nicene-friendly Edict of Thessalonica. And beyond standing up for his former bishop in Constantinople, once arriving at the Roman Empire’s number two city, Jerome threw himself into ecclesiastical and court life there. As with much of the Roman Christian world in around the year 380, Nicene Christology and rigid personal ethics had swept many of the churches and households of Constantinople. Additionally, Rome’s age-old frameworks for patronage were being adjusted to support clergymen, in addition to artists. In almost every way, then, the eastern capital was an ideal setting for Jerome’s inclinations and interests as he reached his intellectual prime.

By the early 380s, Jerome had written his Life of Paul – that novella about the supposed progenitor of the desert hermit movement, again intended to one up Athanasius’ celebrated Life of Antony. And as Jerome’s time in Constantinople lengthened, he began another project, and this was translating works of Christian theology and history that had been written in Greek into Latin. Jerome issued translations of some of the works of the theologian Origen, and followed these with a translation of the church historian Eusebius, augmenting it with original work on Christian history over the past five decades since Eusebius’ death. The resulting historical tome was Jerome’s Chronicle, a milestone volume of Christian world history, tailored to western Latin readers, and the first of its kind available in Latin to the western church. It was a revisionist history, and one that paid heed to the current craze about asceticism and doggedly promoted Nicene ideology over Arianism. These projects, and others, undertaken in Constantinople on the heels of the Edict of Thessalonica, demonstrate Jerome finding grander ambitions than simply enjoying aristocratic patronage or praying in the desert. While scholar Philip Rousseau once wrote that Jerome was “Probably the most unpleasant Father of the Church,” by his early thirties Jerome had decisively accrued the skillset that made him as useful to his contemporaries as he eventually was to posterity.14 And naturally, as it turned out, even Constantinople wasn’t enough for the determined young man. With his translations and original works percolating through the Latin speaking west, and with Nicene Christianity formally proclaimed and asceticism still very much in vogue, in the year 382, Jerome packed up everything he had, and everything he could do, and he brought it to Rome. [music]

Saint Jerome’s Return to Rome

An ordained minister, now, and one with confidence bolstered by a strong intellect, by whatever modest foray he’d actually made into the Syrian desert as a quote unquote hermit, and the success of his recent writings done in Constantinople, Jerome’s first agenda in Rome was to use his various connections to secure patronage in the capital. Arriving in the city with an entourage of several other theologians, Jerome quickly distinguished himself by becoming useful to the Pope. Pope Damasus I, Bishop of Rome from 366-384, needed an insider’s perspective on Constantinople and the politics and theology of the Greek speaking east. And Jerome, whose translations and various residences had made him a bridge between the Mediterranean and Bosporus, was just the person to help out. The Pope also wanted a fresh translation of the Gospels from their original Greek to Latin, a formidable task, but one that Jerome undertook with the absolute professionalism and attention to detail he always brought to bear as a translator.15 Beyond finding Jerome a useful cultural bridge to the Greek Christian world, Damasus also found in Jerome a kindred spirit. Both were captivated by the growing clerical fixation on celibacy and asceticism. The Pope’s own sister had embraced abstinence, and it was likely through papal connections that Jerome made formative acquaintances with a number of wealthy Roman women who would be patrons and friends for much of his life. Let’s talk about these Roman Christian women for a moment.

Saint Jerome with Saint Paula and Her Daughter, Saint Eustochium (1638-40), by Francisco de Zurbarán. Saint Jerome’s energetic patrons have long been acknowledged in Catholic history not only as pious Christians, but also as instrumental to Jerome’s scholary projects.

For Roman Christian women – women like Lea, Marcella, Paula and her daughters, a communal and abstinent lifestyle was likely less somber than it might sound to us today. Since Pythagoras had allegedly encouraged female congregants to participate in his communes way back in the 500s BCE, cult religious activities had given women in the ancient Mediterranean world freedoms, communities, and opportunities for personal fulfillment often not readily available in the patriarchal societies around them. Unwelcome in the traditional academic settings of the Roman Empire, Rome’s Christian women, including Jerome’s patrons, could in various mansions and townhouses converted into religious centers, nonetheless actively participate in theological and intellectual discussions in which they were taken seriously. Their vows of chastity, if and when taken, exempted them from a culture of sexual relations in which Roman noblemen had always done nearly anything they’d wanted to with anyone, and Roman noblewomen were expected to keep their togas carefully tied unless they were bearing children for their husbands. In summation, then, we might see the Christian ascetic women of Rome’s fourth and fifth centuries as conformists adhering to a well-trod path. But in the early 380s, when Jerome returned to Rome, celibate communes of women in the capital were in many ways a countercultural movement in which women renounced sex and marriage for self-determination and intellectual activeness.

Jerome, then, shared many of the values of Rome’s Christian ascetic enclaves. To households like Paula’s, he made himself out to be an authentic desert hermit, and a counselor on all things related to chastity and asceticism. Jerome’s 22nd letter – this one written to Paula’s daughter Eustochium in 384 – is one of Jerome’s most famous. In this letter, we see Jerome ministering to his wealthy patrons, extolling their vows of personal austerity, and talking extensively about desert hermits – especially himself. While, once again, Jerome’s residence in the Syrian desert was in all likelihood not an actual hermitage, he wrote about himself in this letter in very much the same way that Athanasius had imagined Saint Antony in Egypt. Jerome describes himself to his virginal patroness as “living in the desert, in the vast solitude which gives to hermits a savage dwelling-place, parched by a burning sun.”20 It isn’t long in this same letter before Jerome is laying it on quite thick – I’ll read some excerpts to give you an idea of how he presents himself to his young patroness. Jerome wrote:

Sackcloth disfigured my unshapely limbs and my skin from long neglect had become as black as an Ethiopian’s. Tears and groans were every day my portion. . .my bare bones, which hardly held together, clashed against the ground. Of my food and drink I say nothing: for, even in sickness, the solitaries have nothing but cold water, and to eat one’s food cooked is looked upon as self-indulgence. I do not blush to avow my abject misery; rather I lament that I am not now what I once was.21

What follows in the rest of this 384 CE letter a sermon against the pleasures of the corporeal world – against alcohol (8), against lavish food (9-10), and most of all against female sexual immorality (13-23), Jerome’s advice to Eustochium climaxing with the advice to “Let your companions be women pale and thin with fasting. . .Be subject to your parents. . .Rarely go abroad, and if you wish to seek the aid of the martyrs seek it in your own chamber.”22 Presenting himself as an authentic desert hermit, then, Jerome offered his Christian female patrons a combination of moral validation and words of caution. His attitude toward virginity is perhaps best summed up by a pair of sentences from this same letter – Jerome writes, “I praise wedlock, I praise marriage, but it is because they give me virgins. I gather the rose from the thorns, the gold from the earth, the pearl from the shell.”23

What Jerome became between 382 and 385 in the city of Rome was something like a life counselor or independent contractor for a very specialized audience. There were other Christian ministers looking for patrons and patronesses, but Jerome’s already prodigious learning, along with his more disingenuous self-presentation as a desert hermit, helped endear him to chaste Christian women like Eustochium and her mother. These Roman noblewomen, who wouldn’t necessarily have received equality and intellectual validation in a marriage, could at least find a male minister who took them seriously, even if his presence required a small stipend.

But Jerome was far more than a household minister and papal affiliate in Rome. He continued producing a prodigious amount of work. Translations and analyses of the earlier church father Origen, exegetical texts, and correspondence and extemporized tracts designed for public circulation swelled his reputation in the city. But inconveniently for Jerome, what made Jerome and his ideology attractive to the stringent intellectual Christians of the city made him revolting to everyday Christians, not to mention pagans and wealthy nobles who didn’t want to hear that they were scumbags just because they had inherited a couple of farms or had made love to their spouses. There were also Christian clerics of all stamps who, unlike Jerome, used their patronage networks for personal enrichment. Some of them, to Jerome’s fury, enjoyed luxurious lifestyles, operating not unlike some of today’s more unscrupulous televangelists.

The Christian theological atmosphere of Rome during these years – again 382-5, was intensely disputatious. While I don’t want to subject religious history to economic determinism, some of the theological disputatiousness in the city at this time was likely driven by a competition for financial resources. There were only so many aristocratic households that would open doors and wallets to the various professional and self-styled Christian clergymen plying their ideological wares in the city. In an era during which the complex doctrines of Nicene Christianity were still new, Jerome was in active competition against Gnostics, Manichaeans, and other branch movements that may have sounded equally interesting and appealing to wealthy Christian patrons. Thus, part of Jerome’s sectarian venom stemmed from trying to control the cashflow of the Christian nobility. Heretics, once labeled as such in the ideological market economy of Rome, were no longer financial competition. We get a glimpse of him imagining his competitors in that same 22nd letter – to chaste young Eustochium. Jerome describes other Christian house ministers as “others – I speak of those of my own order – who seek the presbyterate and the diaconate simply that they may be able to see women with less restraint. . .[Speaking of a typical corrupt minister, Jerome writes,] Chastity and fasting alike are distasteful to him. What he likes is a savory breakfast.”24 The picture Jerome paints of other aspiring ministers to aristocratic women is of vain manipulators who hurry to the bedrooms of aristocratic women to opine on their pillows and mooch finery from them. It’s a surprisingly tame passage – it was likely written to a teenage girl – but the meaning is clear. Other Christian professionals who do not share Jerome’s ideology are predatory fops, and only he and those like him are legitimate professionals worthy of respect and economic sponsorship. To Jerome’s credit, of course there probably were some creeps prowling around and using all sorts of religious messaging to swindle money and more out of Roman households led by widows. On the other hand, though, an honest Christian teacher who didn’t necessarily share Jerome’s obsession with virginity and asceticism, while he certainly would have been Jerome’s competition, nonetheless sounds like a pretty benign person by the standards of fourth century Roman history.

Eventually, the fierce elitism that Jerome broadcast in Rome had consequences, and Jerome himself was shouldered out of the city for his mixture of belligerent rhetoric and offensive doctrines. By 385, he had spent years dashing around the capital and inviting Roman matrons and girls to buck the traditional patriarchal structure of Roman culture. Jerome had penned criticisms of men and women of all stamps who’d pursued ideologies doctrinally different from his, and he had circulated tracts and epistles against everyday Christians and pagans for insufficiently ascetic and chaste conduct. Two events seem to have turned the tides against him in particular. First, his friend and collaborator Pope Damasus died at the end of 384. Second, and more problematically, his patron Paula’s daughter Blesilla had converted to Jerome’s severe form of Christianity shortly after the death of her husband, embracing abstinence and allegedly fasting. The young woman, tragically, had died three months later, Jerome reporting in a letter that at her funeral, the public made remarks of disgust at the religious extremism in the city – extremism that Blesilla might have been forced into by her mother and her self-appointed minister, Jerome.25 Following the young woman’s death, the new papal administration that rose in the city did not see it fit to protect Jerome’s tenure there, and midway through the year 385, he left, never to return to the capital. [music]

Saint Jerome’s Later Years in Palestine

In 386, with an entourage of patrons and servants, Jerome set up shop in Bethlehem. His patrons Paula and her daughter Eustochium came with him, and in Bethlehem they set up a Christian compound that included a hospice, a convent and a monastery. There, Jerome continued intellectual work on all fronts – translations of Origen and scriptures, novellas about more desert hermits, and biographies of prominent Christian scholars he perceived leading up to him. He wrote vicious tracts against a rival theologian named Jovinian, who had dared to declare that virginal Christians were not better than normal Christians. But then, in 393, in his mid-40s, Jerome got a taste of his own medicine.

The Departure of Saints Paula and Eustochium for the Holy Land (c. 1737-85), by Guiseppe Bottani. Paula and Eustochium continued to help fund Saint Jerome’s projects, both scholarly projects as well as a small Christian commune.

In addition to parrying attacks from capable critics during the 390s and 400s, Jerome was already at work on what would ultimately be his most famous project – this was creating an authoritative Latin bible, later known as the Vulgate, directly from original biblical languages. What we usually hear about Jerome is that he lived abstemiously in the Palestinian desert, moiled over Hebrew and Greek manuscripts, and created an authoritative Latin Bible out of them, and kaboom, that was it – the Vulgate was born and met with open arms by the Catholic clergy. The reality of what happened was quite a bit messier, though. First of all, not everyone wanted an Old Testament revised from the Septuagint. Just as some of today’s Christian worship communities insist on using the King James translation in the Anglophone world, many Christian theologians around the year 400 were fine with the Septuagint – that translation of the Old Testament from Hebrew to Greek that had been undertaken way back in the 200s BCE, allegedly under divine inspiration. Today, we would hardly want to read an English translation of a Japanese translation of, say, Tolstoy. But in 400, Jerome’s decision to go directly to the source, and translate Hebrew into Latin, was seen as more radical than common sense.

Jerome worked on the Vulgate piecemeal for many years. Scholarship has gone back and forth on how much Hebrew and Aramaic he could actually read, and Jerome made use of many other works of Greek and Latin scholarship as he created his new translation. He also, residing in Bethlehem, was smart enough to consult extensively with Hebrew speakers and scholars, hiring one in particular to help him with his work. The resulting Latin Bible that Jerome eventually completed wasn’t actually accepted by the Catholic church until the 800s, and older Latin translations continued to circulate among the clergy throughout the Middle Ages.26 And rather than acclamation, during his own lifetime Jerome was sometimes criticized for his scrupulous attention to the Hebrew original. We have on record serious disputations about the fourth chapter of Jonah, in which Jerome translated the Hebrew word kikayon as “ivy” rather than “gourd,” as it had customarily been translated. Jerome’s rendering is a more accurate representation of the Ricinus plant referred to in the original Biblical Hebrew, but to readers accustomed to hearing it otherwise, it was Jerome who seemed to be the unorthodox one.

Underlying the opposition to Jerome’s Hebrew translation efforts was something a bit more sinister than the inertia of inherited customs. By the year 400, the Greek Septuagint was the Mediterranean Christian world’s Old Testament, itself more than six hundred years old. Since the apostolic age, the Jewishness of Christianity had been a volatile issue for the younger religion, as we’ve seen in earlier episodes. For some of Jerome’s theological opponents, a Latin translation of the Hebrew original was impious in that it made the Old Testament more explicitly Jewish. Jerome’s one-time friend Rufinus accused him of being overly influenced by Jewish connections in Bethlehem, asking Jerome, “What other spirit than that of the Jews would dare to tamper with the records of the church which have been handed down from the Apostles?. . .[I]t is they who are hurrying you into [the] abyss of evil.”27 It’s an idiotic and bigoted criticism, obviously, and one that would have disgusted Peter and Paul alike as much as it does us today. Jerome, when we read some of his letters and polemical tracts, can come across as unlovely and vicious. But in his apologies for translating directly from Hebrew – for consulting with actual Jewish people about Jewish scriptures – Jerome comes across, very endearingly, as a single sane person in an insane world.

By the year 405, Jerome had wrapped up the lion’s share of his new translation. At this point in his life, in his late 50s and having been going full throttle in Christian theology and exegesis for decades, he had made himself into a tremendous scholar. Parts of his career – the exile from Rome in 385 and the Origenist controversy in the 390s, had seen Jerome scrambling to stay afloat in hostile waters, but in the main, he had acquired an admirable work ethic, and a literary and linguistic education that had begun in his early childhood years had given him a nearly unique command of Christianity’s history and sacred writings. In the last fifteen years of his life, Jerome remained in Bethlehem. With secure patronages and a solid, if imperfect reputation, he used his knowledge of Hebrew and Aramaic to write commentaries on the Bible, as comfortable in the theology of the Greek east as he was the Latin west; with decades old training in pagan philosophy and literature; and with a command of Hebrew that allowed him to second-guess five century old mistranslations and resulting misinterpretations still widespread in his world. He passed away in 420, in his early 70s. And in 420, the Roman world was in free fall. Jerome had lived to hear of the Visigothic sack of Rome, and the barbarian takeovers of Gaul and Britannia. But the work that he did – the direction that he envisioned for the future of Catholic orthodoxy and the personal ethics of its clergy proved to mostly be on the winning side of history. And it is to this volume of work that I want to turn our attention during the second half of this program. [music]

An Overall Consideration of Saint Jerome’s Work

Saint Jerome was one of the most prolific Christian theologians who ever lived. Over the next 45 minutes or so, we will by no means cover all of his works, and barely even mention his voluminous commentaries. What I do hope to do, however, is to give you a high-altitude tour of his output. Doing so will give us a sense of Jerome’s singular style, and take us more deeply into the crosscurrents of Christian history in roughly 400 CE. The crescendo of Jerome’s career was the very moment at which the Roman state ceased being the adhesive that held much of Europe together, and the Catholic Church began to take its place, solidified and buttressed with the new orthodoxies of the fourth century. In the pages of Jerome’s works, we get a sustained look at the professional theologians involved in this important transition, and how Nicene Christianity, with an increasingly celibate professional clergy at its helm, became the dominant cultural institution in European history for the next thousand years. Throughout his writings about Arianism, about Pelagianism, about chastity, and in is scriptural commentaries, Jerome was instrumental in mapping out the path that the Roman Catholic church would take in the fifth century and long after.As a writer, Jerome is a person with many dimensions and contradictions. In one letter, as I mentioned before, he disparages all of pagan prehistory and its textual output, growling, “How can Horace go with the psalter, Virgil with the gospels, Cicero with the apostle. . .? [W]e ought not to drink the cup of Christ, and, at the same time, the cup of devils.”28 In another letter, though, he says the exact opposite, telling an orator named Magnus that it’s more than alright for a Christian theologian to widely cite pagan sources, and that Saint Paul had done so, not to mention dozens of major church fathers.29 Though he was fiercely anti-Arian, from an early point in his career, Jerome staked out a more moderate and forgiving position on bishops who had wavered from Nicene Christianity during the tumultuous moments of one of Constantine’s son’s reigns – a more moderate position than that of a Sardinian bishop with the confusing name of Lucifer whose works were influential in the 360s and 370s.30 Jerome was anti-Arian, then, but unlike this contemporary, Bishop Lucifer, Jerome also realized that in moments of crisis and persecution, church leaders had to do what they could to get along. Jerome’s realism also comes across in his writings about how professional clergymen should conduct themselves. While Jerome can be extremely harsh in his assessments of rival theologians, in a letter to a young churchman named Nepotian, Jerome lays out rules for clerical conduct that feel timeless in their prudence and pragmatism. Don’t chase after wealth, Jerome advises his younger colleague (52.5-6). Give sermons that common folks can understand and learn from (52.9). Don’t dress with a lot of finery, nor try to look overly somber (52.9). Realize that a lot of what you say isn’t going to be broadly popular (52.13). Be cautious when serving as a house minister to single women, because people gossip (52.5). And be abstemious with food and dutiful with fasting, but don’t go crazy and make a spectacle of it (52.12). And speaking of fasting, while Jerome’s novellas about hermits show heroic men alone and malnourished in the desert wastelands, Jerome had a far more realistic and compassionate attitude toward Christian women who wanted to nurture their piety in the cities and towns of the Empire. Offering advice to one of his female patrons on how to raise a baby girl, Jerome wrote that the child should eat what her body required and grow strong in the process (107.8), that she should be shown love and affection by all of her family (107.4), and that she should receive an education as expansive as what Aristotle had offered to Alexander the Great (107.6). While he was certainly fixated on the subject of female virginity, Jerome also broadly supported women’s education, in no small part due to the intellectually formidable Christian women who had helped prop up his career.

Chastity and Promiscuity in the Ancient Mediterranean

As a thinker, then, Jerome is often more measured and balanced than he gets credit for when we read short excerpts of his work on this or that subject. If we find Jerome adopting a dogmatic and intolerant position at one point in his oeuvre of works, elsewhere, we can often find him hedging away from that same position and exploring a different one. He lived until his seventies, wrote a lot, and like anyone, his perspectives on certain issues evolved over the decades of his life. On one issue, though, Jerome pretty fairly consistent – the issue of his generation of leading Christians, and this issue was chastity. And so to begin our discussion on Jerome’s writings in a bit more detail, we need to talk about sex – what Jerome wrote about it, and what occasioned these writings. It was a curious turn of world history that a professional association of male virgins and celibates held sway over the ideological history of Europe for a thousand years. The other two Abrahamic religions – Judaism and Islam – do not have celibate rabbis and imams, respectively, and while today’s Hindu and Buddhist monks generally practice abstinence, Roman Catholicism, from Jerome’s life onward, went all in on clerical celibacy in a manner largely unique in world history, requiring not just monks in monasteries, but all priests and bishops in cities and towns to remain celibate, as well. How this happened is a story worth knowing.

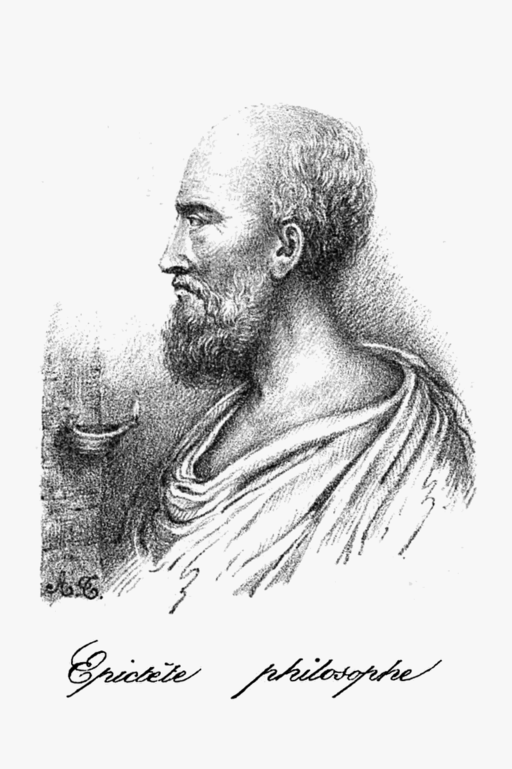

The stoic philosopher Epictetus in an 1826 edition of his works. Ancient Mediterranean culture, before Christianity and after, had its fair share of endorsements of staunch sexual self-regulation, and so Jerome’s generation’s drive toward abstinence had very ancient pagan roots.

Abstinence, then, from the earliest surviving works of world literature, was always given respect and reverence in certain texts. But so, too was romance and lovemaking. In the Sumerian text called The Descent of Ishtar or Epic of Inanna and Dumuzi, the great Mesopotamian goddess Inanna enjoys a ten-page sex scene with her lover, at its crescendo crying out “plow my vulva, man of my heart! / Plow my vulva. . .My sweet love, lying by my heart, / Tongue-playing, one by one, / My fair Dumuzi did so fifty times.”32 This very sexually requited heroine, Mesopotamia’s goddess of war and sex, goes on epic adventures thereafter, being many things, but never, certainly, an alabaster virgin. And some prominent Old Testament patriarchs are also hardly virgins or monogamous husbands, with Jacob siring tribes from a whole household of women, King David having a bevy of wives and concubines, and making sure that Bathsheba’s Hittite husband is killed so that he can have sex with her, and most infamously, Solomon enjoying the company of seven hundred wives and three hundred prostitutes. While the legends and tribal narratives of the Ancient Near East, then, have plenty of characters with considerable sexual resumes, more obviously, Greek and Roman theology and fiction is profuse with gods and mortal heroes raping and dallying with women of all sorts. By the time we get to Petronius’ Satyricon in the first century CE, and Apuleius’ Golden Ass in the second, the early Roman Empire, from the pages of these picaresque novels, comes across as a rather debauched place, though of course we shouldn’t accept these novels as documentary realism any more than we should Defoe’s Moll Flanders as accurately depicting eighteenth-century England or Zola’s Nana as accurately depicting nineteenth-century France.

The point of all of this prefatory discussion is really simple. From the beginnings of recorded history, we have on record cultures, cultural movements and individuals that adopted a variety of perspectives on personal sexual conduct, from the puritanical to the promiscuous and everything in between, including Biblical patriarchs with warehouses full of prostitutes, and contrastingly, bygone Greek sages who preferred celibacy over sex and symposiums. When Jerome’s generation buckled their chastity belts in the late 300s, they were not valorous Christian men and women leading an unprecedented charge against pagan sexual vice. They were part of a movement within fourth century Christianity itself, intensely interested in sex and personal integrity – indeed more interested in sex and chastity than the Apostolic generation had been.

The Fourth-Century Drive to Clerical Celibacy

Jerome and his generation knew exactly what the New Testament had to say on clerical celibacy. As we learned in previous episodes, Saint Paul wrote in 1 Corinthians that it’s a little easier to concentrate on religious matters if one is unmarried and has no family. While Paul’s two paragraphs on the subject at the close of the seventh chapter of 1 Corinthians were a crucial passage for Jerome’s generation, Paul’s statement is also a commonplace within the pagan ethical philosophy of the period. Paul’s contemporary, the Roman philosopher Seneca, expressed apprehension about the effect of passionate marriage on one’s philosophical equipoise, and in the next generation, another pagan stoic philosopher, Epictetus regarded marriage with the same wary hesitancy as Saint Paul.33 Saint Paul’s writings on clerical marriages, then, rehearse formulaic ideas in the Mediterranean ethical philosophy of the Apostolic generation – being married is fine, but if you get married, you’re not going to have as much bandwidth to work and contemplate. And while Saint Paul and his pagan contemporaries agree on this moderate position, a different passage in the New Testament explicitly states that churchmen should be married. 1 Timothy, attributed to Paul but probably by someone else, says that a church leader ought to have a wife and be a good father (1 Tim 3.1-4).34 This passage, in the opening paragraphs of the Bible’s Pastoral Epistles – in other words the Bible’s letters on how church leaders ought to conduct themselves, has stood at loggerheads with clerical celibacy for a long time. In another important scriptural passage related to clerical celibacy – this is the Book of Matthew, Chapter 19 – Jesus tells disciples that divorce is never allowed (19:9), that marriage was mandated by God in the Book of Genesis (19:4-5), and then importantly, “[T]here are eunuchs who have made themselves eunuchs for the sake of heaven. Let anyone accept this who can” (19:12).35 It is an ambiguous statement, on one hand emphasizing that anyone who wants to castrate themselves for religious purposes may do so, but, coming on the heels of a long discussion of how God mandated marriage toward the beginning of creation, it doesn’t exactly demand the existence of a neutered professional clergy, either.I introduce all of this to you to make extremely clear that the drive of Jerome and Augustine’s generation toward clerical celibacy was an institutional and cultural development that gained momentum over the 200s and 300s, a development that was neither inevitable, nor biblically mandated. Jerome’s generation were by no means the first Christians to promote clerical celibacy. Jerome’s early hero Origen of Alexandria had allegedly actually castrated himself on the basis of that passage we just heard in the Book of Matthew.36 The Ante-Nicene church fathers at work before 325 CE vary in their perspectives on sex and virginity, and early Christianity absolutely had married bishops and priests.

The Christian clergy, then, up until the fourth century, had followed the general patterns of other cult religions in the ancient Mediterranean. Jesus and the Apostles came from a world in which Jewish priests married, and in which Greek neighbors and their religious officials married. A century after Jesus, if the Bible is any authority on the subject, a clergy was coming together that looked like the clergies that had existed before it, led by men, often married, sometimes not, who regulated their sexual desires according to greater ancient Mediterranean rules on personal deportment, and because they were public figures and community leaders who sought to set examples of honorable and orderly social behavior. This workaday decency, however, was not radical enough for Saint Jerome and those like him. Jerome’s perspective isn’t quite the untenable notion that sex should globally grind to a stop. But his loathing of human sexuality is in line with the severer tracts of Gnosticism, Manichaeaism, and apocryphal Acts books in its advancement of one very controversial idea – the idea that chaste Christian people are purer, higher, and better than the rest of the species, and that in the afterlife, will be given greater rewards than others who were Christian, but did not practice abstinence. [music]

The Perpetual Virginity of the Blessed Mary

Luca Signorelli’s Saints Eustochium, Mary Magdalene and Saint Jerome (c. 1498). Since the sixth century, Saint Jerome has been strongly associated with female chastity, as in the left panel of this altarpiece, originally installed in a church in Siena but now in the Staatliche Museum in Berlin.

Jerome did not invent the idea of Mary’s perpetual virginity. An apocryphal Gospel of the second century, often called the Proto-Gospel of James, had invented narrative workarounds for Jesus having brothers and sisters – namely that Mary had wed Joseph at a point when Joseph had already been married and had a number of children.38 Other apocryphal Gospels – the Infancy Gospel of Thomas and the History of Joseph the Carpenter, followed this revisionist narrative in and after the 400s.39 Generations of theologians had weighed in on the subject, and by the time Jerome joined the debate, again around 383, most of what could be said on the subject had already been said.40 But Mary’s perpetual virginity was still a disputed topic the year that Jerome wrote his tract. The immediate circumstances of Jerome’s essay “On the Perpetual Virginity of Mary” were a pamphlet written by a rival theologian named Helvidius. Helvidius, reading the New Testament literally, had written that Mary, after Jesus’ immaculate conception, had, via regular old conception, given birth to Jesus’ siblings.

The argument ruffled Jerome’s feathers in numerous ways. At the axis of his ideology is the elitist doctrine that virgins and the unmarried are superior to everyone else, and the notion that Mary had ever been anything but the Virgin Mary was dismaying to him. Thus, in the essay, via argumentative gymnastics and interpretive razzle-dazzle, Jerome rehearses the revisionist argument that Jesus’ siblings were either Joseph’s kids from a previous marriage, or that they were actually Jesus’ cousins, at one point doubling down sufficiently to state that Joseph, too, had remained a virgin for life.41 To be fair to Jerome, his close reading skills are strong, and brought to bear on a topic in which he is obviously passionately invested. And after his careful revisionist exegeses of key New Testament verses, Jerome gets to the core of his argument with his rival Helvidius. Helvidius, evidently, had written that Abraham, and Isaac, and Jacob were all married – that God himself made children in an act of holiness, and that Jesus had entered the world by means of a vaginal birth. The latter claim set off alarm bells for Jerome, who was loath to imagine the newborn son of God coming into the world along with a placenta and amniotic fluid (20). And in terms of Old Testament patriarchs and their wives, Jerome rehearses a standard argument that the New Testament changed the rules for self-conduct, and thus we needn’t trouble ourselves about older verses in scripture that contradict newer Christian doctrines. Married women, Jerome ultimately concludes, are categorically inferior to virgins, as he emphasizes in this testy paragraph:

Do you think there is no difference between [a virgin] who spends her time in prayer and fasting, and one who must, at her husband’s approach, make up her countenance, walk with mincing gait, and feign a show of endearment? The virgin’s aim is to appear less comely; she will wrong herself so as to hide her natural attractions. The married woman has the paint laid on before her mirror, and, to the insult of her Maker, strives to acquire something more than her natural beauty. Then come the prattling of infants, the noisy household, children watching for her word and waiting for her kiss, the reckoning up of expenses, the preparation to meet the outlay. . .Tell me, pray, where amid all this is there room for the thought of God? Are these happy homes?43

That passage from Jerome is not very appealing It bifurcates women into two classes. In Jerome’s imagination, there were holy virgins, and then there were compromised women, minxing around with painted faces for their husbands, their spiritual integrity fractured by the sometimes inelegant ruckus of home life. A moment later, confident that he’s made his case, Jerome claims that only chaste women are holy (23). [music]

Saint Jerome’s Perspective on Chastity and His Female Patrons

This extreme position, which Jerome had adopted by his mid-30s, was evidently palatable to his female patrons in the 380s, because it shows up often in his letters to them. Jerome’s student and patron Eustochium, that chaste daughter of his older patron Paula, was a woman he knew likely through her 20s, 30s, and 40s, and Eustochium was the recipient of a number of letters from Jerome. The most famous of these – Jerome’s 22nd epistle, is a long dictum on the superiority of chastity. We already heard an often-quoted statement from this letter earlier – Jerome’s proclamation that “I praise wedlock, I praise marriage, but it is because they give me virgins. I gather the rose from the thorns, the gold from the earth, the pearl from the shell.” The statement isn’t exactly ambiguous – virgins are the real treasures, and the rest of us are just rubbish. While Jerome’s imaginary hierarchy of a chaste minority shimmering over the lower masses of sexually active drudges is probably clear by this point, it’s still worth our time to read some of what he wrote to Eustochium in his lengthy 22nd letter.Jerome begins his letter with the assurance that “I write to you thus, Lady Eustochium (I am bound to call my Lord’s bride lady), to show you by my opening words that my object is not to praise the virginity which you follow, and of which you have proved the value, or yet to recount the drawbacks of marriage, such as pregnancy, the crying of infants, the torture caused by a rival, the cares of household management, and all those fancied blessings which death at last cuts short.”44 Although he avows that he will not say much on these topics, the letter does exactly this. At the slightest hint of feeling passion, Jerome tells Eustochium, she must cry out in prayer and ignore the impulses of the flesh (22.6). Jerome tells his young patroness that she must never have wine, as wine only intensifies sinful impulses toward sensuality (22.8). Eve, Jerome tells Eustochium, was cursed with motherhood and exiled from Eden, and cursed, as all sexually active people are cursed, to work and drag briars out of their crops, but Mary and Jesus, who were virgins, were much purer and higher, just like virgins on earth (22.18-9). In an what I assume is an unintentionally sensual description, Jerome writes that “no gold or silver vessel was ever so dear to God as is the temple of a virgin’s body” (22.23).

On one hand, a dozen paragraphs into the letter it begins to feel predictable and even innocuous – a chaste man’s smug ovation to chastity, written for a chaste reader. On the other hand, the sheer fierceness and venom of Jerome’s words on virginity are often startling, as in this slightly longer passage. Jerome writes to Eustochium:

Ever let the privacy of your chamber guard you. . .Dinah went out and was seduced. . .You will be wounded and stripped, you will lament. . .Jesus is jealous. He does not choose that your face should be seen of others. . .You may be fair, and of all faces yours may be the dearest to the Bridegroom; yet, unless you know yourself, and keep your heart with diligence, unless you avoid the eyes of the young men, you will be turned out of My bride-chamber to feed the goats, which shall be set on the left hand. . .All. . .efforts [toward virginity] are only of use when they are made within the church’s pale; we must celebrate the Passover in the one house. . .Such virgins as there are said to be among the heretics and among the followers of the infamous Manes must be considered, not virgins, but prostitutes. (22.25,38)

It is a dark, and vicious passage, beginning with threats of sexual violence couched in allusions to Genesis and Ezekiel, likening mild Jesus to the furious Yahweh of the Book of Numbers, and finally, concluding that non-Christian virgins are prostitutes. Jerome’s most famous letter is full of such intense flights of rhetoric, and it culminates in the pithy statement that “Death came through Eve, but life has come through Mary” (22.21). I’m sure you get the tenor of his message, but it’s still interesting to consider his letter in the greater context of Rome’s fourth century. Jerome’s letters show a genuine respect for women’s intellectual capacity, and for their energy and dynamism in a changing world. His distinct reverence for the Virgin Mary, although it relies on weird interpretative horseplay, has at its core real awe at the virgin mother as well as the divine son. But inasmuch as his ideology did promote respect for the acumen and agency of Christian women, in hindsight, he can come across, rather clumsily, as a product of his times. Jerome lived in an age when Apostolic Acts literature – the Acts of Paul and Thecla, the Acts of Peter, the Acts of John, the Acts of Thomas, and more – Jerome lived in an age when Apostolic Acts literature was telling story after story about women leaving consummated marriages with their husbands and throwing themselves at the feet, sometimes literally, of the Apostles, transferring control of their sexuality from their pagan husbands to their Christian teachers. In many cases, including those with Jerome and his female patrons, such transitions may have been an improvement. But Jerome’s instincts, in his epistles to his female patrons, aren’t categorically different from those of his male pagan forebears. Do this and not that, he tells his female readers, that and not this; do what I say with your body, and if you slip up and have forbidden sex, you will never, never be the same.

To zoom out a bit, beyond the little archive of letters Jerome wrote to Christian widows and virgins, Jerome and those like him turned dour countenances toward human sexuality. The author of 1 Timothy might have stated that churchmen ought naturally to be married, and Jesus himself reminded his disciples that humanity had been told to be fruitful and multiply, but as the fourth century turned toward the fifth, and clerical celibacy and the doctrine of Original Sin blazed into Late Antique Christianity, a new age had dawned for the religion. Two centuries later, Late Antique Catholicism had widely absorbed the doctrine of Mary’s perpetual virginity. The Frankish historian Gregory of Tours, as he gave a basic definition of his own Catholic faith in the 570s or 580s, declares in his famous History of the Franks, “I believe in the Blessed Mary, who was virgin before the birth, and was virgin after the birth.”45 Chastity, then, by the early Merovingian period, was all the rage.

Saint Jerome’s Against Jovinianus

As we discussed in an earlier episode, clerical celibacy had been under discussion at the First Council of Nicaea in 325, two decades before Jerome’s birth.46 It had come up at other councils before, and as the decades of the 300s passed, in Christian history we find various authorities weighing in on the subject. But the voices in favor of clerical celibacy appear to have been the most strident, pushing against the customs of pan-Mediterranean culture in favor of what to many Christian priests and bishops felt was an extreme position. We heard in a past program about how the churchman Synesius of Cyrene, in 409, didn’t want to take a vow of chastity with his wife or remain childless upon assuming his holy orders, and was still able to become a bishop even at this relatively late point. It was certainly more difficult to find priests and bishops willing to take vows of chastity, and for outlying dioceses and provincial parish churches, Catholic authorities didn’t always have long lines of qualified abstinent candidates lining up to assume office. But against the considerable cultural inertia for Christian clerics to behave basically like other religious clerics, a vociferous core, over the 300s and 400s, took over a critical mass of ecclesiastical offices and they changed Catholic history forever. There was no toggle switch to click, by which a pope, bishop, or council could suddenly implement the change. Many bishops and priests of Jerome’s generation were still married, and had assumed vows of celibacy within marriage or simply remained sexually active. Priestly concubines and courtesans, prostitutes, and genuine romantic relationships of all sorts have always been tucked away beneath the flying buttresses of the church, because people are people, and we like to get busy with one another. Nonetheless, doctrinally speaking, the most formative Christian culture wars around clerical celibacy took place during Jerome’s generation and the two that bookended him. And as he grew older, he grew even fiercer on the subject.Jerome never pulled punches with theological rivals. And one of the voices against clerical celibacy was that of a theologian named Jovinian. We don’t know much about Jovinian – almost everything we know comes from Jerome’s tract against Jovinian. But if Jerome is a reliable source on this rival theologian, Jovinian was basically a democratic moderatist who saw all Christians as equal, regardless of their chastity and asceticism, and this egalitarianism infuriated Jerome. For Jerome, gaunt desert hermits and unwed women were a higher order of Christians than faithful worshippers with wives, husbands, and families. Any theologian who contradicted this hierarchy made Jerome’s own celibacy and lifelong zeal toward asceticism meaningless, and so he could not pass over them in silence.

According to passages Jerome quotes in his tract against Jovinian, the following was the core of Jovinian’s argument against the asceticism and celibacy that had come into vogue in Nicene Christianity over the 300s. Jerome tells us,

[Jovinian] says that virgins, widows, and married women, who have been once passed through the [purification] of Christ, if they are on a par in other respects, are of equal merit. He endeavors to show that they who with full assurance of faith have been born again in baptism, cannot be overthrown by the devil. His third point is that there is no difference between abstinence from food, and its reception with thanksgiving. The fourth is that there is one reward in the kingdom of heaven for all who have kept their baptismal vow.47

In the year 393, then, Jerome, in his mid-40s, objected to the notion that all Christians were equal, regardless of chastity. He objected to the notion that eating according to the natural cadences of one’s needs for food was as worthy a thing to do as fasting. And he objected to the notion that all Christians were treated equally in heaven. Jerome was not the first to do this. Back around year 200, also bucking the staunch egalitarianism of Jesus’ words in the Gospels, Tertullian had invented the idea that martyrs were fast tracked directly to heaven after death. For Jerome and Tertullian, then, there were Christians, and then there were better Christians. On one hand, it’s understandable that Jerome and Tertullian would hierarchize the afterlife in this way. It’s an awful thing to die as a martyr. It’s hard to take a vow of celibacy, and stick with it. And it’s nice to think that people who have been through such trying experiences will eventually receive fitting compensation. But on the other hand, perhaps Christianity’s greatest appeal during its early centuries was that it disregarded pedigree, ethnicity, wealth, and social class, and it sought to bring everyone together under the same tent. Jerome pictured a pedestal in this tent, and himself standing over and above other Christians, on top of it.

Jerome, then, has personal stake in the clerical chastity controversy. Some of his arguments against Jovinian are highly relevant and detailed engagements with 1 Corinthians, which contains Paul’s most important writings on the subject. But one of the reasons Jerome often gets called unpleasant is the aggressiveness and the sheer brutality with which he goes after his ideological adversaries. Jovinian’s egalitarian ideas are not misguided, in Jerome’s estimation – they are “the hissing of the old serpent. . .the dragon [that] drove man from Paradise” (1.4). Jovinian’s work is, in Jerome’s estimation, “nauseating trash. . .the devil’s poisonous concoction. . .the Syren’s fabled songs” (1.4). Jovinian calls Jovinian himself “the most voluptuous of preachers” (1.4), and Jovinian’s interpretation of a key verse in 1 Corinthians (7:25-6), according to Jerome, is “his strongest battering-ram with which he shakes the wall of virginity” (1.12), a phallic image if there ever were one. Jovinian’s temperate idea that married folks are about as good as virginal folks drives Jerome to such flights of anger that Jerome advances bizarre and nonbiblical propositions, such as when he growls that a “virgin who has once for all dedicated herself to the service of God. . .should one of these marry, she will have damnation” (1.13). To Jerome – although Jesus had told Peter that 77 times was not too many to forgive a wayward Christian (Matt 18:21-2) – to Jerome, sex was the ultimate and final transgression – one that made most of humanity into a lower caste of human beings and damned consecrated virgins who slipped up, just once, to hellfire.

To say just a few more words about Jerome’s important 393 CE tract against Jovinian, often in this vehement essay it is Jovinian whose occasional quotes sound like the voice of reason in the midst of Jerome’s rancor. Jerome quotes Jovinian as having written the following: “I do you no wrong, Virgin: you have chosen a life of chastity on account of the present distress: you determined on the course in order to be holy in body and spirit: be not proud: you and your married sisters are members of the same Church” (1.5). We read these words and see a theologian who understood that some Christians would naturally desire to be married, just as others would opt for a celibate life, and all were equally welcome, respectable members of the church. This equality, in Jerome’s more fanatical perspective, was not acceptable. He cites the Book of Proverbs to argue that women’s passion is “insatiable; put it out, it bursts into flame; give it plenty, it is again in need; it enervates a man’s mind, and engrosses all thought except for the passion which it feeds” (1.28). Thus, to Jerome, a man who marries, at best, weds a woman whose “love is compared to the grave, to the parched earth, and to fire” (1.28) – in other words, things with bottomless appetites.

Loathing of Sexuality: The Greater Fourth-Century Picture

Jerome did not invent the timeworn misogynistic notion that women are either virtuous virgins or vile vixens. He didn’t invent the idea, which dates back to Hesiod and ancient Egyptian instructional literature, that women have insatiable sexual appetites and enervate the energy and mental clarity of men. He didn’t invent the idea that a single and celibate life affords a person with extra time to devote to spiritual and intellectual pursuits, which is, some important factors aside, objectively true. But what he did do was to hurl himself into the promotion of all of these ideas, and in his writings on the perpetual virginity of Mary, his letters to Roman women, and most of all his long tract against Jovinian, his outstanding talents as an exegete are used to pinpoint scriptural passages that contradict his extremist viewpoints on sex and marriage, and find ways to scuttle around these same passages. An immense amount of the work that Jerome does in his dictum against Jovinian is expended in making elaborate arguments about the Biblical verses that Jovinian had used to underscore the equality of all Christians. And while Jerome’s obsession with sex, and his anti-egalitarian ideology haven’t aged particularly well, his attention to chapter and verse is stalwart, his interpretive work cogent enough, and his knowledge of the Bible and Christian history leading up to him are generally unimpeachable.Still, in the works of John Chrysostom, and more famously Jerome and Augustine, we see Christianity decisively hardening after the Edict of Thessalonica in 380. The imperial proclamation outlawing non-Trinitarian Christianity had ignited the interests of certain Christians for more strictures, and a religion that was more tightly controlled, and imposed more rigid control onto its laity. While Christianity had certainly never trafficked in the free love ethics of Petronius’ Satyricon or Apuleius’ Golden Ass, it had also had congregations led by married bishops and priests. It had its celebratory Song of Songs and as well as its ireful words against placing stock in love and worldly things. It had its kindly Book of Ruth as well as its occasional ravings against marriage and miscegenation. But oddly, although the church fathers shrieked curses against Gnosticism and Manichaeism, which were at their crescendo during the lives of Jerome and Augustine, Gnosticism and Manichaeism passed something onto Late Antique Catholicism in the fourth century – a scathing disgust of the material world counterbalanced with faith in a celestial world – a disgust specifically rooted in a loathing of human sexuality.

Gnosticism and Manichaeism, long before Jerome and Augustine did, were Christian movements that had also singled out sex as the enemy of the pious believer. The Gnostic Secret Book of John had recorded that the demiurge Yaldabaoth raped Eve, just as the Manichaean creation story held that the base muck of the material world was fashioned from the semen and aborted fetuses of dark angels. As wacky as these narratives were, their dual emphasis on a sex act as the moment that the world went astray may have actually influenced Jerome, and was certainly an influence on the former Manichaean Augustine. Jerome, in his tract against Jovinian, argues that “as regards Adam and Eve we must maintain that before the fall they were virgins in paradise. . .the Devil. . .did seduce Eve; and. . .after displeasing God she was immediately subjected to [Adam]” (1.16, 27). Though commonplace, this is quite a strange interpretation. Genesis says nothing at all about Eve’ s virginity in Eden, and indeed God tells the pair in the first chapter of the Bible to “Be fruitful and multiply” (1:28) long before the incident with the apple, indicating that Eden, in the actual Bible, was not some Christian chastity camp.48 As we know, the exile from Genesis narrative is analogous to contemporary Greek stories of Pandora’s box and Promethean fire – it is not, as Jerome implies, the story of a sex crime, but a tale about the pursuit of forbidden knowledge, a trickster narrative about an unnamed snake, and an etiology about why the snake crawls on its belly. But in the fourth century, Gnostic and Manichaean doctrines were in the air, and their strong disdain for sex may have intensified an older demotion of the material beneath the spiritual that had been a part of Christianity since the beginning. In so many cult ideologies of the ancient Mediterranean – Pythagoreanism, Orphism, Stoicism, early Christianity, Gnosticism, and Manichaeism, there is a dichotomy – a dichotomy between saved and blighted; between enlightened and unaware. And Jerome and his generation created a new dichotomy within Christianity itself. As the theologian wrote in 393, “Marriage replenishes the earth, virginity fills Paradise” (16). The old material-spiritual dualism of Plato here was given a new flavor – a flavor of ascetic Christianity blended with Gnostic and Manichaean loathing of sexuality. It was no longer enough to be a Christian. Marriage and sex spun the meat grinder of the material world, and the Christian virgin, and the chaste cleric – these, and only these could attain the highest levels of salvation. [music]

The Historical Context of the Push Toward Clerical Celibacy