Episode 34: The Traditions of Our Forefathers

Euripides’ The Bacchae, one of the darkest and bloodiest works of Ancient Greek tragedy, is about the spread of cult religions during the late Peloponnesian War.

| Read Transcription | References and Notes |

| Episode Quiz | Episode Song |

| Episode on Spotify | Episode on Apple Podcasts |

| Previous Show | Next Show |

Euripides and the Background of the Bacchae

Hello, and welcome to Literature and History. Episode 34: The Traditions of Our Forefathers. This program is on the Bacchae, an ancient Greek tragedy first performed in the city of Athens in 405 BCE, written by the playwright Euripides, and staged about a year after his death. The Bacchae is often proclaimed as Euripides’ masterpiece. It is the eighth and final work of Ancient Greek tragedy we’ll cover, and probably the darkest and most enigmatic of all of them.Literature is a restless thing. One generation’s masterpiece is the next generation’s punchline, and new styles arise to meet the tastes of changing times. Although all of the Classical Athenian theater that we now possess is from a single century, between the first staging of Aeschylus’ play, The Persians in 472 BCE, and the premiere of our play for today, Euripides’ Bacchae, in 405, the tastes of Athenian theatergoers and playwrights had evolved. We have read the work of Aeschylus, Sophocles, and Euripides in our show so far, and all of them are as admired today as they were two and a half thousand years ago. At the same time, though, Aeschylus, Sophocles, and Euripides are very different writers, each one having left behind a rather different body of work.

Out of the three of them, Euripides occupies a strange position. On one hand, Euripides seems to have been somewhat out of step with his own times. A religious iconoclast, and an unconventional interpreter of ancient Greece’s mythological cycle, Euripides often lost theatrical competitions to playwrights who wrote more orthodox adaptations of the mythological canon. Euripides’ plays, even for ancient Greek tragedies, are often grim, and as we learned last time, their depictions of violence, misery, and loss seem to have not always sat well with contemporary audiences. On the other hand, though, far more Euripides plays have survived from the 400s BCE than have survived from Aeschylus or Sophocles. We currently have nineteen surviving plays from Euripides, and from Aeschylus and Sophocles, just seven each. In ancient literary history after the 400s BCE, in both theater and later, ancient novels, Euripides was easily the most influential classical playwright, and he’s a figure we’ll keep coming back to as we move forward into the Hellenistic period, Roman history, and Late Antiquity.

Euripides, then, was simultaneously a black sheep and a bustling innovator, winning, in later literary history, what he lost in competitions with his contemporaries. While Euripides made tragedy darker than tragedy had ever been, he also forged paths forward to new genres, and asked touchy questions that challenged the norms of the faltering Athenian empire over the course of the Peloponnesian War.1 The 19 surviving plays of Euripides show an enormous range. While we could cover many of them in this series, and indeed many had different kinds of influences in later literary history, the Bacchae, for many reasons that you’re about to learn, is a play that we can’t pass over.

To begin the story of the Bacchae, very likely the last play that Euripides ever wrote, we need to discuss its central character. This central character is an Ancient Greek god. You’ve probably heard of him, and seen a painting of him. He was one of the oldest Greek deities – possibly worshipped even before Zeus himself.

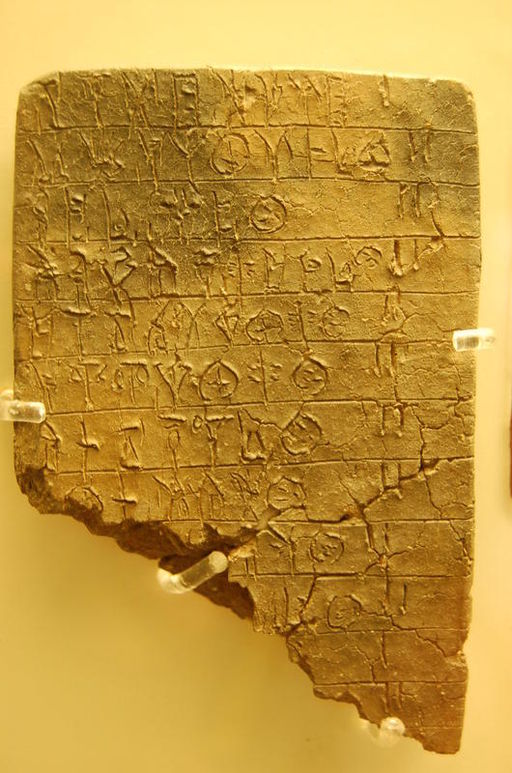

A thousand years before Euripides lived, and far away on the other side of Greece – in the southwestern Peloponnese, there was a settlement that is today called Pylos. Before the Bronze Age Collapse of the 1100s BCE, the Peloponnese was ringed with coastal civilizations that we call Mycenaean – this era of Ancient Greek history came long before the famous democratic period of Classical Athens. Homer calls it “sandy Pylos” or “rocky Pylos,” and Odysseus’ son Telemachus travels to Pylos in the Odyssey. In this city, archaeologists discovered a tablet written in an ancient Mycenaean script today called Linear B. On this tablet were the syllables di-wo-nu-so-jo.2 Now, Linear B tablets frequently mention gods that were extinct by the lifetime of Euripides – Zeus, Hera and Poseidon appear together with strange names like Manasa and Drimios.3 But the name di-wo-nu-so-jo, found at Pylos – this god was not at all extinct during the spring of 405 BCE, in the city of Athens. In fact, the entire town was gathered in his honor in the theater on the southeastern slope of the Acropolis. His name wasn’t, by 405 BCE, di-wo-nu-so-jo. It was Dionysus. [music]

The Many Dimensions of Dionysus

Recognizable variants of the name Dionysus have been discovered throughout the pre-classical world – in Knossos on the island of Crete, and other city-states of late-Bronze Age Mycenaean Greece. Dionysus was an old god – in the archaeological record, at least, far older than Yahweh in neighboring Canaan. And in order to understand Euripides’ most critically regarded play, we need to know a bit more about di-wo-nu-so-jo, later known as Dionysus.

A Mycenaean Linear B tablet. The decipherment of this Bronze Age script has demonstrated how old, dynamic, and multifarious the world of Greco-Roman polytheism was, long before Eurpides’ Bacchae. Photo by Gautier Poupeau.

Now, all of that sounds pretty benign. The god of wine likes to celebrate and have fun. When you first meet the ancient Greek pantheon, it can seem deceptively straightforward. There’s the lightning guy, the ocean guy, the jealous wife woman, and the harvest girl, and that kind of thing – each deity has his or her own central attribute and tagline, and they go about hurling thunder, or controlling the tides, or bringing wheat and barley to the masses, and so on. But in reality, ancient Greek polytheism is a religious tradition that stretched thousands of years – from Bronze Age tablets on the island of Crete, all the way down to Late Antiquity and the slow Christianization of Rome. Because of its enormous lifespan and geographical distribution, the Olympian pantheon of ancient Greece was not a static group of twelve stalwarts who stood their ground for thousands of years doing the same thing. You can think of it this way. Christianity has hundreds of branches, though it only has one God. Imagine if Christianity had dozens of Gods, and demigods – and certain regions particularly favored one god, or one variation of one god, while only paying lip service to others – and – that these regions didn’t frequently communicate with one another. You would have a lot of Christs, a lot of Yahwehs, a lot of Marys, a lot of Holy Ghosts, and on and on. This was what happened with Ancient Greek religion. Ancient Greek archaeological sites are often like giant merry-go-rounds – you’re likely to see a Hera, or an Apollo, for instance, but dozens of other figures are likely to show up based on how where the wheel has stopped turning, often strange figures whose names who have been lost for thousands of years.

So like all figures in the Ancient Greek pantheon – Dionysus has his tagline – the god of wine. Artists – the most famous being Caravaggio and Velazquez – artists depict Dionysus as a youth, scantily clad, sallow in complexion and with a dissipated face, while others depict Dionysus as a little cherub or chubby boy slurping wine. And this is how Dionysus has come down to us – the celestial purveyor of alcohol, the heavenly underachiever whom you worship at parties and festivals, the harmless tubby god of drunks and ne’er do wells.

But Dionysus has some variations – some dark and violent variations that are the keys to Euripides’ Bacchae. Dionysus wasn’t just the god of wine. He was also the god of madness – of rituals that led to temporary insanity and ecstasy – not uncommonly, nocturnal rituals that took place beyond the bounds of city walls. Dionysus has many nicknames – throughout much of the Bacchae, he’s called “the roaring one,” an epithet that bespeaks his animal side, as though beneath the veneer of the boyish god of wine there is an old monster waiting to tear its way free and live without the constraints of civilization. In antiquity, Dionysus was frequently described as having horns, and could supposedly take the form of a lion, or a bull, shedding aside his human exterior in an instant. And in the archaeological record, the name Dionysos Omestes exists, which means “Dionysus the eater of raw flesh,” suggesting the kinds of practices rumored to occur in cult rituals devoted to the god of wine.

And among all of these traditions, there is another legend about Dionysus. In this legend, Dionysus went to the distant east, through Mesopotamia, through Arabia, and into India, fighting wars and spreading the sacred rites of wine and Dionysian worship. In fact, the last surviving epic of Greco-Roman antiquity is called the Dionysiaca. Nearly as long as the Iliad and Odyssey combined, the Dionysiaca was written about 800 years after Euripides’ Bacchae, though the central legend that it chronicles is older than Euripides himself. And in this much later Dionysiaca, Dionysus is the lord of mayhem as much as he is the amicable god of wine – a genocidal, lusty, wrathful and jealous god with an army of centaurs, satyrs and nymphs who butchers all opposition he encounters and force-feeds alcohol to foes as well. The Dionysiaca, from the 400s CE or so, is a weird story – I’ve read it and we’ll cover it later in this show – a bloody, psychedelic epic in which what feels like a military full of ecoterrorist wiccans go around dismembering people with tree vines in order to spread the gospel of getting hammered and eating raw meat. As late as the Dionysiaca was written in antiquity, though, again, the story of Dionysus’ journey east was a very old one. Importantly for our purposes today, there was a famous scene in ancient art related to this legendary eastward journey that Dionysus took. In this scene, Dionysus leads what’s called his thiasus, or ecstatic retinue, back home from the distant east, triumphant and likely not sober, having spread the gospel of wine all the way over to the Asian side of Eurasia. When Dionysus rolls up onstage in the Euripides’ play, the Bacchae, this is what he’s been doing – proselytizing, with murder and alcohol, on his own behalf.

So to sum up, Dionysus may have been the god of intoxication, but as the god of intoxication Dionysus was also lord of many things associated with intoxication – lunacy, fertility and orgiastic coupling, and above all of these, transmutation – the change of grapes into wine, and equally, the transformation of a sober citizen of a polis into a fanatic making blood sacrifices beneath the moon and trees. Dionysus, to the Greeks of Euripides’ time, could take a nice, upright citizen of a polis and put him into the throes of wild ecstasy and madness, eating the raw flesh of animals in an obscure cave or dark fire pit, far beyond the torchlight of the city assembly or marketplace. And Dionysus could take a seemly, rational woman, and make her one of the Bacchae, or female priests of the God of wine, dancing and cavorting in the wilderness under the influence of his maddening spell. That name, by the way, “Bacchae,” or female priests of Dionysus, is important, since it’s the name of the play we’re about to spend some time with. So Euripides’ Bacchae, again first produced in Athens in the year 405 BCE, has for its main character the god of wine, and the play is named after the female zealots who worshipped Dionysus – women who actually existed and attended ritual celebrations of the god of wine during Euripides’ lifetime.

Euripides’ Bacchae, as you will learn over the next hour or so, is a play about the power of religion. It’s a play about religion’s capacity to form and influence individuals regardless of their state and even familial allegiances. It’s a play about how religion can cause both reverence and piety, as well as violence and depravity. In Euripides’ time, political systems and regional alliances were shifting. The Bacchae came out during the final months of the Peloponnesian War, when much of the Greek world had been demolished by almost thirty years of conflict. But amidst all of this tumult, Euripides knew, certain religious traditions were unfathomably old, and rooted deeply into ancient, fire hardened clay tablets just as much as they were embedded in human culture and customs. And so Euripides’ final, and most shocking play, as fleets of ships sunk in the Aegean and mass executions were carried out inside the walls of captured cities, Euripides’ final play asks us this: is religion a force that can help bring people together – a deeply rooted set of customs that supersede our current wars and technologies and state systems? Or is religion a force of disintegration, causing us to form into factions and deepening the differences that we feel we have from one another? Euripides doesn’t have the answer to this riddle. But in the Bacchae, he asks the question. [music]

Thebes, Cadmus, and Semele: Dionysus’ Origins in the Bacchae

So we’ve talked about Dionysus, and we now know he’s an old god, and that in addition to being the god of wine, he was the god of ecstasy, and madness, and that his ritual celebrations involved varying degrees of sex and violence. And we now understand that a central theme of Euripides’ Bacchae is going to be the volatile power that religions have over us – especially, ancient religious traditions with obscure origins. There’s just one more thing we need to do before we start the Bacchae, and that’s talk about the events leading up to the opening moments of the play. Let’s start with the play’s setting – the city of Thebes.

Francesco Zuccarelli’s Cadmus Killing the Dragon (1765). Thebes, the setting of the Bacchae, like Athens, Corinth, and many other Ancient Greek city states, had many legends about its inception.

Thebes was founded by a legendary dragonslayer. His name was Cadmus, and by the time the Bacchae begins, Cadmus is old. As the curtains of the Bacchae open, Cadmus already has many children, and has passed kingship down to his grandson. From beginning to end, the story that’s going to fill the next hour is about a fierce feud between two of Cadmus’ grandsons. One of these two grandsons has been made king of Thebes. His name is Pentheus. Pentheus, the grandson of Cadmus, is young, but at the same time, austere and set in his ways. Pentheus, the recently appointed king of Thebes, has little patience for religious sentiment, or the worship of powerful gods. But regal young Pentheus doesn’t know something. What Pentheus doesn’t know is that his cousin is the god Dionysus. And Euripides’ Bacchae is about a fierce, and eventually very bloody disagreement between confident, skeptical King Pentheus, and Dionysus, the god of wine, ecstasy, and transmutation. Pentheus versus Dionysus. Sometimes time authors map out ideological disputes in their works by having one character embody an idea and another character embody another idea, and in the Bacchae this is certainly the case, with the chilly religious skepticism of young king Pentheus on one side, and the primal, wine guzzling, religiously orthodox Dionysus on the other.

Pietro della Vecchia’s Jupiter and Semele (17th century). The story of Dionysus’ virgin birth and subsequent salvific relationship with mankind, which became increasingly widespread during the tumultuous Hellenistic period, was an important forerunner to Christianity.

At this juncture, baby Dionysus, still a fetus, evidently survived the awful incident. Zeus picked up the baby, and the father of the gods sewed the fetal Dionysus either up into his thigh, or into his scrotum, until the baby was ready to be born. Dionysus then came into being, born from his father’s thigh or testicles, and headed out to the east to begin his fun, wild life as the god of wine, madness and orgies. I guess when you’re born in that – unique fashion – you’re probably not going to be the god of wisdom or chastity – the booze and group sex thing just seems to fit well. Anyway, in spite of Dionysus’ miraculous and strange birth, back in Thebes, things weren’t going so well. The poor mortal Theban princess Semele had three sisters, and they began spreading scurrilous rumors about her. Semele hadn’t actually been bedded by a God, her sisters said. No, no. It had been a mere mortal – an ignominious sexual act – and Semele was a despicable, fallen woman. Semele’s sisters said that Semele had burst into fire as punishment for lying about her pregnancy. One of these sisters – and remember that these are all the daughters of Cadmus, founder of Thebes – one of poor Semele’s sisters was the mother of Pentheus, the heir to the throne. And so the central conflict in the play – cold, rational king Pentheus versus the god of carousing Dionysus – this central conflict was preceded by an earlier conflict, when Pentheus’ rather cruel mother accused Dionysus’ deceased mother of harlotry.

So that’s a fair bit of back story, I know. But now, actually, Euripides’ play the Bacchae should be quite straightforward. Just remember that its central story is a violent feud between Dionysus, who has just returned to Thebes, and his cousin Pentheus, the coldly rationalist Theban king whose mother has slandered Dionysus’ mother.

Unless otherwise noted, quotes from the Bacchae in the remainder of this program will be from the John Davie translation, published by Penguin in 2005. And everybody, I hope you like this one. I won’t say I saved the best ancient Greek tragedy for last – I love all of the ones I chose for the podcast, but holy smokes, the Bacchae is quite a story. Exciting transition music! [music]

The Bacchae‘s Beginning: Dionysus Explains His Return to Greece

Just outside the royal compound at Thebes, there stood a tomb. Smoke wafted out of it, blowing slowly back into the heart of the city, and around this tomb, ivy clung to an old fence. It was quiet there, at first – only the sound of birds overhead along with the occasional crackle from the tomb fire fell over the outskirts of the palace grounds. A drama had already unfolded, and a new one was beginning.A man appeared near the tomb. He might have been young, or old – it was impossible to tell – but in the modulations of his voice, and the slow movement of his hands, there was something green and vinous, like the ivy twining through the nearby fence and already touching the base of the new tomb.

The stranger said, “Newly arrived in this land of Thebes, I am Dionysus, son of Zeus” (128). The tomb, Dionysus said, was the tomb of his mother, Semele, the deceased princess of Thebes. Semele had been seduced by the great god Zeus, and then, she had died giving birth to Dionysus. And in memoriam, Dionysus had already sent beautiful tendrils of vines around his dead mother’s tomb in a wreath, so that the poor departed princess of Thebes would be remembered.

Dionysus said that he was on the verge of completing a great journey. He had been in the golden fields of western Anatolia, and in the mountainous meadows of central Asia Minor. He had seen the bright steppes of Persia, and the buttressed cities of India. He’d seen the bleak high country of the Medes, and the gorgeous wealth of Arabia, and everywhere he’d gone, whether there were Greeks or barbarians, he left people dancing with passion and ecstasy, people who would worship him long after his departure.

He had only recently come back to Greece, he said. And Dionysus had come back to Greece for good reasons. Court women of the city of Thebes – in fact the very sisters of his beloved mother Semele – these princesses had said that their sister’s pregnancy was not due to any deity. Semele’s sisters had alleged that Dionysus’ poor mother had lost her virginity to some mortal, that the story of divine impregnation was all false, and that Dionysus himself was nothing more than a bastard. These sisters said Semele had died not due to having witnessed the true form of Zeus, but as punishment for falsehood. But, Dionysus said, he was already making them pay. [music]

The Dionysian Frenzy of Thebes

Dionysus announced that he’d struck at the heart of Thebes by driving its women into madness. Dionysus proclaimed, “First I have made this city of Thebes resound to women’s cries, dressing them in fawnskins and putting the thyrsus in their hands, my ivy-bound spear” (128). This “thyrsus” was a staff, made of a stalk of fennel woven over with ivy and topped with a pinecone. The thyrsus was the emblem of Dionysus in antiquity – an emblem of growing vines, of pulsing life, and gushing seeds. The sisters of his mother Semele, said Dionysus, had been driven mad as they clutched their thyrsus staffs. Dionysus said that all the womenfolk of Thebes, including the libelous princesses, “have the mountain as their home and their wits have deserted them. . .they sit beneath green firs, on rocks open to the sky” (129).

William-Adolphe Bouguereau’s The Youth of Bacchus (1884). While modern depictions of Dionysus tend to show him as a fun-loving purveyor of wine, to the ancient Greco-Roman world Dionysus had a dark, violent side, and an increasingly central role in the Hellenistic pantheon.

Driving the Theban women into a frenzy, however, was only part of Dionysus’ payback. His grandfather, Cadmus, was the founder of Thebes, and its most prominent citizen in times of legend. And Cadmus had another grandson – a grandson named Pentheus. Pentheus, the son of one of the princesses who had maligned poor Semele, had just been awarded with leadership over all of Thebes. But, impiously, and sacrilegiously, King Pentheus had entirely ignored the god Dionysus. The young new king Pentheus had offered Dionysus no sacrifices, and said no prayers to him. And so, Dionysus said, soon he would reveal his identity to the city of Thebes. If he weren’t welcomed, said Dionysus, he would lead his frenzied women, his Bacchae, or his maenads, into battle against the Thebans.

These Bacchae, also called maenads, or ecstatic worshippers of Dionysus, began to file in, and in the remainder of this play these women will serve as the chorus – hence the fact that the play, the Bacchae, is named after them. The maenad women of the chorus, or the Bacchae, beat their drums and thronged around the walls of the palace. They sang of Dionysus as the Roaring One – because their lord could take the form of a lion or a bull. They described how Dionysus had been born prematurely from the womb of his dead mother, and how Zeus had sewn the baby up in his thigh, and when the baby was ready to be born, Zeus “gave birth to a god with bull’s horns and crowned him with a garland of serpents, whether it is that maenads entwine in their hair wild serpents they have caught” (130). Having sung of their lord’s birth, the Bacchae of the chorus voiced a prayer. They told the Theban citizens to twine ivy in their hair, along with oak leaves and pine needles, and to wear animal skins, because up in the mountains, people were dancing to Dionysus. They said that up in the mountainous areas where Dionysus was worshipped, milk, wine, and honey flowed freely, and the balm of incense hung in the trees.

As the chorus fell into silence, an old man shuffled onto stage. His name was Tiresias, and he was a prophet. You may remember Tiresias from the Sophocles plays Oedipus the King and Antigone as well as Homer’s Odyssey. If you were writing a play in the 400s, and needed a prophet character, you probably used Tiresias. So, Tiresias, himself dressed like a maenad, or worshipper of Dionysus, said that he had come to visit the retired King Cadmus. Old King Cadmus, said the prophet Tiresias, knew why he had come.

Old King Cadmus appeared from the Theban palace. And like Tiresias, King Cadmus was dressed in the clothing of a Dionysus worshipper – wild garments, including buckskins woven with ruffs of wool. Cadmus, like the maenad women, clutched a thyrsus staff, and the old king said that the ecstatic worship of Dionysus had made him forget his age. The two old men said that they’d dance to Dionysus, their hair bound with ivy. The kingdom had been entrusted to Cadmus’ grandson, Pentheus. There was no need for governance, the old men thought. Old Cadmus and Tiresias felt that they could now show unrestrained, joyous piety to their god Dionysus. Cerebral young Pentheus could do what he wanted, but, to the retired king Cadmus and the prophet Tiresias, the sacredness of religious traditions would never bow to rationalism.

Tiresias vowed, “We do not chop logic when speaking of divinity. The traditions of our forefathers that we have inherited, as old as time, shall not be overthrown by any clever argument, though it be devised by the subtlest of wits” (132). Young and old, the two venerable men agreed, regardless of standing, were all united in the worship of Dionysus – the dancing, the spontaneity, and the passion that the god demanded. But a moment later, a man arrived who felt very, very differently. [music]

Pentheus Appears and Castigates the Worship of Dionysus

His name was Pentheus. Pentheus was the grandson of old Cadmus, and Pentheus had recently been appointed the King of Thebes. Unlike his forefathers, and unlike his mother, Pentheus was not a religious person. Pentheus said he had heard that grotesque things were happening in Thebes. The women, Pentheus said, had been cavorting in the shady glens of mountains, and drinking wine, and sneaking off with men. It was, Pentheus summarized, all in the name of some novel deity called Dionysus, but as far as he, Pentheus, was concerned, the Theban women were serving Aphrodite, and acting on their lusts and basest impulses. Pentheus said he’d hunt down the revelers and put an end to their unrestrained revelry.As for Dionysus, said Pentheus – Pentheus had indeed heard that some strange conjurer had arrived from the east, flush with wine, and seducing women into mysterious rites. But this man was no son of Zeus. Pentheus vowed to execute this interloper. Pentheus groused and harangued about Dionysus and the disintegrating social order of Thebes, and then, suddenly, King Pentheus saw the old king, Cadmus, and the prophet, Tiresias. Pentheus was shocked to witness such respectable men dressed in the garments of the cult of Dionysus, wearing deerskins, and ruffs of wool, and ivy.

The newly appointed king Pentheus castigated his grandfather Cadmus, and the prophet Tiresias. What, Pentheus said, were these old men doing practicing wild rites to a false god? Pentheus said that if the two graybeards weren’t so old, he’d punish them with all the other worshippers of Dionysus.

Before either of the old men could reply, the leader of the chorus interjected. Pentheus, the chorus leader said, was the one guilty of sacrilege. And then, in a long speech, the prophet Tiresias explained the indubitable importance of Dionysus. Tiresias said, in the Penguin Davie translation,

This new god whom you mock will achieve a greatness I cannot describe throughout Greece. Men enjoy two great blessings, young man: firstly, the goddess Demeter, the Earth – call her by whichever name you will – who sustains mankind by means of dry foods; then there is he who came afterwards, Semele’s son, who invented the liquid draught of the grape to match her gift and introduced it to mortals. This it is that puts an end to the sorrows of wretched men, when they get their fill of the flowing vine, this that confers sleep on them and forgetfulness of daily troubles. There is no other antidote to suffering. He, a god himself, is poured out in honour of the gods, so that he is the cause of man’s blessings. (134)

The prophet Tiresias elaborated further. Zeus, the prophet Tiresias said, had indeed delivered Dionysus from his thigh. Dionysus, and wine, filled people with sudden and intense visions – with panics and passions. And yet Dionysus wasn’t simply an arch-seducer of women. The chorus leader – one of the celebrants of Dionysus – told stern King Pentheus that women could full well perform the rites of Dionysus and be chaste and honest. Thus, the chorus leader told Pentheus, it was only natural that the former king Cadmus would bow to this new, powerful, dynamic god, and young King Pentheus would be wise to do the same. And Cadmus reached forward with a crown of ivy, preparing to place it on the head of King Pentheus.

Pentheus, however, was disgusted. He drew back. He told them he didn’t want any part of their idiocy. And Pentheus ordered his men to find this so-called Dionysus, to tie him up and bring him to Thebes to be stoned to death. With this proclamation, Pentheus stormed off. [music]

Pentheus Meets the Disguised Dionysus

Tiresias gawked at the blatant blasphemy of young King Pentheus. Tiresias and Cadmus promised to hold one another up and continue to revere Dionysus. And once the two old timers had gone slowly off together, the chorus of maenad women began another song. The Bacchae of the chorus also balked at the unholy words of harsh young King Pentheus. The women reeled at the notion that anyone could hate Dionysus, when Dionysus’ role was “to make men dance together as one, to rejoice at the sound of the flute, and to put an end to care, when the liquid gleam of the grape enters the feasts of the gods and in the ivy-wreathed feasts of men the wine-bowl casts its veil of sleep over them” (137). They said that Dionysus loved feasts, and peace – that wine brought joy to the rich and poor, and that when all of humanity bowed to a god, one had to respect the wishes of his fellow people.

A red figure bell crater, dated to about 440 BCE, showing Dionysus holding a thyrsis staff (center), a maenad (left) and a satyr (right). The iconography would have been familiar to the original audience of the Bacchae.

Pentheus was unmoved by this miracle. He studied the captive stranger, and he said that the man was indeed handsome. Pentheus asked Dionysus about his background. The disguised Dionysus said that he had been brought up in the east – that Dionysus himself had initiated him in the secret rites of wine, and dancing, and song. Pentheus wanted to know about these rites – what were they? And why was Thebes becoming infected with this plague of intoxicated fervor? But Dionysus said that the rites were secret. Everyone, the disguised god said – all the countries beyond Greece, were practicing the rites of Dionysus. The two men argued intensely, Dionysus always serene and unperturbed – one step ahead of Pentheus’ angry dogmatism, until Dionysus concluded, “You do not know what your life is, or what you do, or who you are” (140). Pentheus could not bear this insult, and ordered the infuriatingly serene youth away to a dark stable, resolving to sell his female followers into slavery, or to make them his own servants. The disguised Dionysus nodded. He said, “I will go, for I do not have to suffer what is not to be. Be sure, however, that this insolence of yours will be punished by Dionysus, whose existence you deny. When you wrong me, you are leading him off to prison” (141).

Pentheus did not pick up on this rather strong clue that the disguised Dionysus offered him. You’d think maybe Pentheus would note that the female priestesses of Dionysus had spontaneously been magically freed when the handsome and unworldly easterner had been brought in. Perhaps Pentheus would say, “You know, stranger, you seem a bit ethereal yourself – how about we go in the palace and have some cookies, rather than me rampantly disrespecting you in front of everyone?” But this, alas, did not happen. The Theban king was obstinate and fierce in his anger, and the disguised young god was led off to the dark stalls where the horses were kept.

Dionysus’ Grip Tightens

The chorus sung an interlude – asking the central river of Thebes, and the citizens of the city why they would even in part reject the coming of Dionysus. Yet suddenly, the voice of Dionysus was heard. He told the maenads of the chorus he was present in Thebes, and they were ecstatic to know that their god was there on the scene. Then, the maenad women prophesied doom for King Pentheus. And presently, doom seemed to come. The palace shook – the stone lintels suspended above doorways rattled, and lighting exploded over the grave of Dionysus’ mother Semele, and then, suddenly, Dionysus appeared. He was still disguised as a youth, but this time, he appeared from the palace, and not the dark stables.Dionysus’ followers asked the disguised Dionysus how he had managed to escape, and the god offered them an amusing story. As Pentheus had tried to bind him, he said, he’d deluded the king into trying to tie up a bull. And then, Dionysus had begun the fire on his mother’s tomb, and the earthquake, and created a phantom in the courtyard that Pentheus had tried to stab. In the end, Dionysus had rattled and cracked the structure of Pentheus’ palace, and left the young king exhausted.

Just as the disguised Dionysus offered this explanation, out of the palace appeared Pentheus himself, in a state of rage and consternation. Pentheus demanded to know how the strange eastern youth had escaped, and Dionysus told him that he’d had help from – of course – Dionysus. Just then, a messenger arrived from the mountains to the northwest. Now remember, messengers in Ancient Greek tragedy are important. Because scenes almost never change, it’s up to messengers to deliver often lengthy accounts of what’s happened elsewhere.

This recently arrived messenger from the high country to the northwest began his story. He said that the maenads had sped forth from Thebes, and that Pentheus’ mother, Agave, was one of them. The messenger was a mountain herdsman, and said he’d seen the maenads sleeping peacefully in a field. Then, he’d seen the women awaken, rubbing their eyes and tightening their dappled fawnskins and hides together with bands made of snakes – snakes that licked the women’s cheeks.

In some of the women’s arms were baby deer and wolf cubs, and all women who could do so nursed these critters with milk from their breasts. A woman struck her thyrsus staff against a rock and water splashed out of it – in another place, a staff made wine gush out of the ground. The messenger continued his story. He said that he and other villagers and herdsmen had sought to capture Agave – again Pentheus’ mother – and bring her back to Thebes. So the herdsmen hid in a bank of leafy bushes, and prepared to spring. When they ambushed the maenads, though, things went terribly wrong.

Everything started moving. All the wild animals, and leaves and even the mountain began to shudder and shake, and the maenads went into a violent frenzy. The maenads went after a herd of cattle, and then things became gruesome. The herdsman reported that,

One of them you might have seen using her hands to wrench asunder a young heifer with swollen udders – how the creature bellowed! Others were rending and tearing apart full-grown cows. You might have seen ribs or cloven hooves flung everywhere; and bloodstained pieces hung dripping from the pine-branches. Bulls that had been proud creatures before, with anger rising in their horns, were wrestled to the ground, dragged down by the countless hands of young women. They were stripped of the flesh they wore faster than you could have closed those royal eyes of yours. (146-7)

After feasting on the raw flesh of the herd of cattle, the maenads hurried down into a village. There, they stole children. Their hair burned, but it did not singe them. The maenads fought off a defensive line of men and then, with their new initiates, they sped back up into the mountains. Once they reached their spring of wine, the herdsman said, “they washed off the blood, while snakes licked clean the gory stains from their cheeks” (147). [music]

Pentheus Plans to Spy on the Maenads

To Pentheus, the implications of this dire story were clear. Thebes was going to have to go to war. Young king Pentheus told his shield bearers, and his cavalrymen, and his archers that it was time to march against the maenad women. Women, Pentheus grumbled, ought not to behave in such a fashion.And then Dionysus began to execute his plot – a plot to cause the downfall of King Pentheus. The disguised Dionysus warned Pentheus that the king should do otherwise, because engaging the maenads in combat would bring the Theban army to a bloody end. Pentheus and Dionysus, after some back and forth, came up with a compromise. Pentheus wanted to see the maenads for himself. And Dionysus said this was easily possible – but Pentheus would need to be disguised as a woman, because the maenads did not take kindly to men spying on them. Pentheus, after some further debate, consented. He would let the strange eastern youth dress him, and then escort him to see the maenads in their own element. Pentheus went into the palace.

And then, with the king offstage, the disguised Dionysus and offered the chorus a speech. Pentheus, said the god of wine, would go to the maenads and be killed, as was fitting. Only, to make the stern king more vulnerable, he would be made to go slightly mad, and thus clad as a woman, and in a state of insanity, Pentheus would be led through Thebes. The Thebans would see their sacrilegious leader, cowed and ridiculous, being led to his execution, and thereafter, there would be no doubt as to the power, and the primacy, of Dionysus. [music]

The Befuddlement of King Pentheus

With Dionysus and Pentheus in the palace, the chorus of maenad women sung of how they wished they could join their brethren in the forest. Tradition, they said, was all that counted – bowing to ancestral customs and worshipping the gods was the best thing that one could do. The chorus said, “It is no great expense to accept that power lies with the divine – whatever the divine may be – and that what has become accepted through long ages is everlasting and grounded in nature” (151). As the chorus finished their song, Dionysus came out of the palace with Pentheus.The god asked Pentheus to stand before him. Something about the Theban king was different, even beyond his change of clothes. Pentheus had lost his senses. The Theban king was seeing double, and he exclaimed that the disguised Dionysus was no youth at all, but instead a great bull. Pentheus had Dionysus adjust a lock of his hair, and then Pentheus asked about the hem of his dress, and how to hold his thyrsus staff. In the midst of his insensibility, Pentheus revealed how badly he wanted to see those maenads who worshipped Dionysus – to hide and watch their sensual rites. Dionysus spoke to him patiently, telling the muddled king that he would have all of Pentheus’ desires satisfied, and, in asides to the audience, intimating that the horror of Pentheus’ looming death would serve as an example to all mortals. The arrogant young king of Thebes, now humbled, exited the stage to go and meet the devotees of Dionysus in the wilderness.

Now the chorus of maenads burst into song again. They said they hoped that Pentheus’ mother Agave would find the king and do violence to him. The Theban king, they said, had committed a sin in questioning orthodoxy. Returning to a theme from their previous song, the maenads emphasized that accepting divine decrees without questioning was the key to happiness. After more sentiments for this sort, and more violent curses laid on the head of the hapless King Pentheus, the chorus was silent. An indeterminate time passed. And then a messenger appeared onstage to tell of what had happened up in the dark glades of the mountains. [music]

The Bad Death of King Pentheus

This messenger was an attendant of King Pentheus. He faced the chorus of maenad women, and began his story. Pentheus, he said, had been killed. The chorus responded with such ecstatic delight that the messenger was startled, and cautioned them against rejoicing in an act of murder. Then, he began the detailed part of his tale.

Pentheus being dismembered by the maenads, the climactic scene of the Bacchae. Roman fresco from the Casa dei Vettii in Pompeii.

And then the maenads came for Pentheus. They flung stones at him, and hurled wooden staffs, but their projectiles didn’t make it to the treetops. They cut furiously at the pine tree’s roots, but still it stood. But finally, the women stood in a cluster and uprooted the tree with their bare hands. Pentheus fell into the throng of berserk maenads. His mother, Agave, was the first to attack him. Pentheus desperately removed his disguise so that his mother could see his face, but she showed no signs of recognizing him. In fact, the messenger said, “Agave, foaming at the mouth and rolling distorted eyes, her senses gone, was in the grip of Bacchus and deaf to his entreaties. She grabbed [Pentheus’] left arm below the elbow, set her foot against the doomed man’s ribs and tore out the shoulder, not by strength but by ease of hand that was the gift of the god” (157). Another maenad ripped off Pentheus’ other arm. The carnage intensified as Pentheus tried to muster enough breath to scream. The messenger saw a Maenad go by carrying an arm, and another with a foot – the king’s ribs had the skin ripped off of them, and the fervid worshippers of Dionysus tossed Pentheus’ flesh back and forth like children’s toys.

His body lay everywhere in the wilderness. His head, the messenger said – Pentheus’ head was now impaled at the top of his mother’s thyrsus staff, and Agave was coming to Thebes. And the messenger, though he had seen the massacre committed in Dionysus’ name, nonetheless closed his story with a remark the chorus had already made. The messenger said, “To be virtuous in one’s life, and show the gods reverence is the noblest course; it is also, I think, the greatest wisdom a man can possess” (158). With that, the messenger left the chorus alone. [music]

The Return of Agave and the Chastisement of Thebes

The chorus of maenad women held a celebration alongside the battered walls of the Theban palace. And into the frolic and singing came Agave, the mother of Pentheus, bearing the severed head of her son. She was greeted cordially enough by the chorus, and bragged that she had met a mountain lion cub and killed it. And then, holding the bloodied head aloft, she invited the women of Thebes to eat with her. Only this time, they recoiled. Agave said she was exultant – she and the maenads had embarked on a great hunt, and their prey had been far from ordinary. But the chorus bade Agave to show the city of Thebes the trophy of her kill. Agave announced it – they had taken the young mountain lion with no weapons – they’d torn the mountain lion apart with their hands – where was her father Cadmus, said Agave? She wanted to show him the severed head. And where was her son, Pentheus? Pentheus could mount the head high on the city walls!Just then, old Cadmus appeared. He had with him the various gory scraps that had been his grandson. He said he had followed a bloody trail through the wilderness, and that he’d heard his daughters were hurrying back to Thebes. Agave saw her father there, and she exultantly told the old man that she and her sisters were fine daughters, indeed. She showed him the severed head, telling him to take it, and to prepare for a feast.

Old Cadmus immediately saw what had happened, and was devastated with sorrow. And yet at the same time he saw that it had been a punishment from Dionysus – that the sacrifice had been fair, gasping “he has destroyed us, the god. . .justly but excessively” (160). Agave did not understand. She told him to come closer and see the fruits of her hunt. Cadmus asked Agave to calm herself. He said to look up into the sky, and to take a moment. Agave did so, and her faculties of reason slowly seemed to return. And then Agave looked down and saw that she was holding her son’s head, and that it had been torn off. Cadmus told Agave that she and her sisters had committed the murder.

And he revealed something else. Agave and her sisters, who had disrespected their sister Semele, and Semele’s divine son Dionysus – these impious sisters had been driven into a frenzy. Everything that had happened had been orchestrated by Dionysus. Cadmus said that his beloved daughter Agave had once been one of his chief sources of pride – Agave had, after all, more than anyone kept his palace and affairs in order. Disrespecting Dionysus and his mother, however, had been a fatal error. Old Cadmus said, “[N]ow. . .it is sorrow for me and misery for you, pity for your mother and misery for her sisters. If there is anyone who holds [the] deities in contempt, let him consider this man’s death and believe in the gods” (162).

Dionysus then appeared atop the palace, no longer in disguise. He said that Cadmus would be changed into a great serpent and lead barbarian forces in war against Greece. This would be Cadmus’ punishment for not honoring Dionysus. Cadmus begged Dionysus to reconsider, but the god said, “Too late you [have come] to know me; when you should have, you did not” (163). Cadmus pleaded with him, saying, “you come upon us with a hand too heavy. . .Gods should not be like mortals in temper” (163). Dionysus only said that these events had been decreed long ago by the will of Zeus.

And so the fates of the impious Thebans were decided. Cadmus was to be exiled to a barbarian land. And Agave and her sisters had to live with the horror of their murders. And, as Agave left the stage in one direction and Cadmus the other, the chorus voiced a final three cryptic, irresolute sentences. The chorus sang, “many are the forms taken by the plans of the gods and many the things they accomplish beyond men’s hopes. What men expect does not happen; for the unexpected heaven finds a way. And so it has turned out here today.” And that’s the end. [music]

The Bacchae: An Orthodox, or Iconoclastic Story?

So that was the story of Euripides’ Bacchae. The Bacchae is the eighth ancient Greek tragedy we’ve read in our show, and what makes it unique among those we’ve been through is that its foremost character is a god. Athena and Apollo show up as arbitrators in Aeschylus’ Eumenides, but the Bacchae, from end to end, focuses on Dionysus, and the worship of Dionysus is the central subject of the play. Because the Bacchae is such an idiosyncratic story among the other ancient Greek tragedies that we’ve read, let’s begin very simply, and try to get a sense of the main theme of Euripides’ last play.On the one hand, all of the Bacchae is like a parable straight out of the Old Testament. A group of nonbelievers remain obstinate, and refuse to honor a deity. The deity prepares a gory and spectacular punishment for the nonbelievers, and the subsequent bloodbath is a lesson for anyone in future generations who dares to display religious dissent. The tale of Bacchus and Thebes is the tale of Yahweh and the Pharaoh in Exodus. In one sense, then, The Bacchae is a religious allegory, pure and simple. Honor Dionysus, or suffer dire consequences. This seems to be the interpretation of Euripides’ brief choral song at the end – fate turns unexpectedly, and the gods are the ones who turn it.

It’s possible that there’s nothing more to the Bacchae than this. The play, after all, premiered at the festival of Dionysus, in the Theater of Dionysus, in a city in which there were cults to the god of wine and madness and ecstasy. Maybe the Bacchae is a highly orthodox cautionary tale that encourages us to worship our ancestral gods, abide by generations-long conventions, and keep our heads down, or otherwise face divine wrath. In the story, wise old Tiresias says, “The traditions of our forefathers that we have inherited, as old as time, shall not be overthrown by any clever argument, though it be devised by the subtlest of wits” (132). And the chorus also encourages yielding to inherited customs. The chorus proclaims, “[A]cceptance without protest of what the gods decide, and to abide by the mortal lot, means a life free of sorrow” (154). Perhaps the Bacchae won Euripides one of his few first prizes in the city Dionysia in the spring of 405 because it is basically just a conventional cautionary tale.

But let’s consider the other side. In the play you just heard summarized, Dionysus and his followers aren’t exactly kind, or orderly, or equitable. When people are getting torn limb from limb, and raw flesh is being gobbled down, and babies are being stolen, and wolf cubs are being suckled from the nipples of human females, you either have heavy metal music, or a theological hierarchy that looks a bit confused. It is, of course, the theological hierarchy of the god of wine and madness, so would expect the theology of the Bacchae to look a bit riotous. But Dionysus isn’t just wild. In the Bacchae, we have a central figure whose thirst for blood begins to seem totally out of step with his otherwise beneficent quest to spread a spirit of celebration and revelry throughout the known world.

To put it simply, there is a tension in the Bacchae’s finale. As the curtains close, there is some sense that practitioners of impiety have been punished. Pentheus is an egotistical and unappealing character – one of ancient Greek tragedy’s many mortals who don’t respect the gods. At the same time, though, as the play ends, there is also a sense that Dionysus’ punishment of his dissidents, in its gory totality, was vastly excessive in proportion to the crimes that have warranted it. Not everyone wants to strip down to forest-themed underwear and get plastered in the woods. Some of us, like Pentheus, have significant responsibilities.

So, we’ve heard the play. And we’ve talked about its two sides – how Euripides’ Bacchae can be read as an endorsement of Dionysus, and also as a story that’s wary of religious fervor. What we’re going to do now is to talk a bit more about history. We will begin by discussing some Ancient Athenian religious traditions that would have affected the way that Euripides’ original audience watched the world premiere of the Bacchae in 405 BCE. And then, we will talk about cult movements that, by the end of the 400s, were proliferating all over the ancient Aegean world – cult movements involving Dionysus and other figures. And at the end of this episode, once we’ve contextualized the Bacchae with its historical milieu, I am going to tell you something else about Dionysus that not too many people know, and something that I think you’ll find rather astounding. But to begin, let’s learn a bit about the religious traditions of Ancient Greece. [music]

The Thesmophoria

The main characters of the Bacchae are men – Dionysus, Pentheus, Cadmus and Tiresias. Behind and surrounding these central figures, however, are women. There are the maenad women of the chorus. There’s the tragic figure of Dionysus’ mother Semele. And beyond the walls of Thebes are the women who have been driven mad by the magic of Dionysus – Pentheus’ mother Agave and her sisters, the ill-fated women who slandered their departed sister. In fact, throughout the Bacchae, it’s almost as though Dionysus is a warlock and the wild women out in the mountains are his coven – witches who ignore the conventions of society, eat wild, strange foods, and steal children.Real women in classical Athens, as we learned a number of shows ago, were not out despoiling the countryside, unsupervised, and suckling wild animals. Real Athenian women – especially noble ones, were carefully superintended by their husbands and fathers. The freedom of mobility, and social and sexual intercourse granted to male citizens were largely denied to women. And so a play about a flock of unsupervised female religious zealots – some of them noblewomen, was a work of imaginative fiction.

Or, for the most part, a work of imaginative fiction. There was one festival in which women took a central, and exclusive role. It was an old ritual – a relic, like Dionysus himself, from the Bronze Age or even before. This festival was called the Thesmophoria. It took place in mid-October, and it honored the goddess of the harvest, Demeter, and the remarkable story of her daughter Persephone. Persephone – eventually – was the goddess of the underworld. She wasn’t always this way, though. Initially, Persephone was a deity of nature, picking flowers in a field. But the god of the underworld abducted her. Hades kidnapped Persephone, and Persephone’s mother Demeter was enraged. Being the goddess of the harvest, Demeter was not defenseless. She stopped all the plants from growing, and the world grinded to a standstill, until the gods told Hades he had to give Persephone back to her mother. The god of the underworld complied. But Hades also knew that Persephone had already eaten pomegranate seeds in the underworld – seeds that tied her, inevitably, to the realm of Hades. And so every year, Persephone spent the winter months underground with her husband. But in the growing season, she came to earth, and the miracles of crops and wildflowers and growing vines were all hers. And that’s the story of Persephone in a nutshell. There are other stories of Persephone we’ll explore later in our podcast, but that one will do, for now. Depictions of Persephone, the goddess of the underworld, are everywhere in ancient Greek art. When you see a tumultuous kidnapping scene, with a pale woman thrown over the shoulder of a brawny dark god, it’s Persephone and Hades, and it’s almost impossible to go to an exhibition of classical Greek art without seeing this very scene, one of the most common illustrations in black figure pottery.

So the holiday that I mentioned – the Thesmophoria – took place in mid-autumn. It was the most widespread festival of Ancient Greece. We know that the Thesmophoria was quite widespread because a very specific sacrificial practice took place in sanctuaries to Demeter and Persephone during the Thesmophoria festival. Specifically, women dropped pigs to their deaths into chasms dug into the earth, and then drew them up again – a ritual honoring the descent of Persephone into the underworld and her arrival back on earth, year after year. Following the pig sacrifice, subsequent days of the festival involved fasting and eating pomegranate seeds, but most importantly of all, during the Thesmophoria, women performed their ceremonies in exclusively female groups, staying out all night together.

For obvious reasons, the controlling husbands of Athens and other cities were wary about their wives and daughters spending unsupervised holidays in Demeter sanctuaries. Just as Dionysus warns Pentheus that the wild women in the Bacchae don’t like to be seen by men, during the real Thesmophoria, women were supposed to have privacy. Various violent urban legends survive about women bathing in blood during the Thesmophoria, castrating an intruding king, and kidnapping other intruders.4 Archaeological remnants of the pig chasms in Demeter temples, however, don’t show any evidence of spontaneous seasonal violence toward men. The men, it is much more likely, stood around the cities and grumbled worriedly about just what the women were doing out there beyond the limits of masculine regulation. They fretted that their wives and daughters were doing something beyond merely honoring Persephone and the changing seasons.

That Demeter and Persephone story, if you think about it, must have resonated with the confined women of Classical Athens. It’s a story about an unbreakable bond between a mother and daughter, and about a girl who, before she is ready, is snatched up into a marriage and suddenly confined in a claustrophobic space – a myth, sadly enough, that was the true story of the tens of thousands of real women who attended Thesmophoria rituals, year after year in the ancient Aegean world. Largely deprived of unregulated social interaction, the women who attended the Thesmophoria each autumn may have seen the festival as their single week of escaping the upper rooms of their homes, and being resurrected into the social freedoms they’d once enjoyed as girls. They were the Persephones, enjoying an all-too-brief season of unmediated togetherness with other women. Ancient Greek men were fascinated, and even haunted, by the Thesmophoria – by the idea that women had, for a short span, a small degree of social freedom. Six years before the Bacchae, Aristophanes’ play Thesmophoriazusae (or, women celebrating the Thesmophoria) premiered alongside his more famous Lysistrata – both of these are about groups of women banning together to wage campaigns against male domination.

So knowing all of this, let’s reconsider Euripides’ Bacchae. There were certain festivals in Ancient Greece that predominantly involved women – the Thesmophoria is the most famous one. These festivals, at the end of the 400s, had made the spectacle of, and the fear of women running rampant a preoccupation of the theatergoing public of Athens. The people who attended Euripides’ Bacchae in 405 had already thought about women getting together and doing questionable things, and dangerous things. And so when they heard the Bacchae’s chorus – those fanatical maenad women who so unwaveringly supported Dionysus, and when they heard of the roving band of bloodthirsty women in the countryside, Athenian theatergoers, especially male ones, might have thought of the Thesmophoria, troubled by the notion of unfettered groups of women.

But Euripides’ audience in 405 BCE, when they saw those volatile female Dionysus worshippers onstage, would have thought about more than just the Thesmophoria. Euripides’ original audience might have had another culturally conditioned reaction to the women in the play rampaging through the Theban countryside. It was not only a spectacle of unrestrained women. It was also a spectacle of people, apart from their polis or city state, whose primary loyalty was to a single god, and who would do anything – including committing murder, for their single god. To a patriotic Athenian of 405 BCE, as the city buckled and groaned in the awful final year of the Peloponnesian War, the spectacle of religious enthusiasts dancing underneath trees, and murdering their own king, might have seemed especially absurd and unspeakable. Loyalty to the polis, and fidelity to the city and its ships had been characterizing mantras of Athens for several generations. But the popularity of cult religions, by the late 400s, meant that Athenian leaders had to contend not only with Spartan allies abroad, but with religious factions within their own walls.

Let’s take a few minutes to learn about cult religions in antiquity. This subject will come up a lot in future episodes of Literature and History, and 405 BCE is a perfectly good time to get a panoramic sense of what cult religion was in the ancient Mediterranean. [music]

Pythagoreanism, Orphism, and the Dionysian Cult

Every major religion today began as a cult – a little group of people united around a single purpose or figure. Religious cults thrive and grow during periods of social disintegration – during difficult times, we seek a sense of belonging, and answers to tough questions, and religious cults can help fulfill both of those at once. And while religious cults offer community and hope to their participants, they are often troubling to established societies. After all, unregulated convocations of people – lower class, upper class, men, and women, all gathering together for rituals and the exchange of new ideas – might decide to go their own way, regardless of the norms of their parent civilizations.Many religious cults flourished during the thousand-year period of Greek and Roman civilization’s ascendancy. They ranged from transient associations that only involved a few people, to intercontinental religious movements with many adherents. If you’ve heard of Mithraism, for instance, or Isiac religion, meaning the worship of Isis, or the cult of Magna Mater, or the great mother Cybele, you’ve heard of some of the major cults of Mediterranean antiquity. We often hear that Greeks and Romans worshipped Zeus and Jupiter and the Olympians. Some of them did. Others worshipped cult deities, and in this and later episodes of our show, we’ll learn a lot about ancient Greek and Roman cult religions, as eventually, a Greco-Jewish cult religion called Christianity became very impactful indeed.

For now, let’s stick with the classical period, and discuss cult religions around Athens as Euripides would have known them. During the late Peloponnesian War, three cult religions are documented as being present in Athens. The first of these three was the Pythagorean cult.

Pythagoras, who lived in the mid-500s BCE in southern Italy, is now of course known for A2 + B2 = C2, the Pythagorean theorem. But although we think of him as a mathematician, Euripides and his contemporaries thought of this earlier Greek as a cult leader. At the core of Pythagoras’ beliefs was the doctrine of reincarnation, and the immortality of souls. To the Pythagoreans, the human soul was deathless, or athanatos, or immortal – a word in Homer that’s used only alongside the gods.

Because they believed in reincarnation and the immortality of souls, Pythagoreans had a very careful and conscientious mode of self-conduct. They observed strict dietary regulations. They saw not only in animals, but in all things, a possibility that any given scrap of ash, or mote of dust had had a past life. They were famous for not even eating beans. Like any new age cult of any age, the Pythagoreans were sometimes maligned as weirdoes, but nonetheless, their otherworldly beliefs, their careful eating, and their mindful self-conduct didn’t exactly make them seem like a threat. So the Pythagoreans are the first of three cults documented as extant during the Classical period. Let’s consider another cult movement during the life of Euripides.

Often associated with the Pythagoreans was a sect called the Orphics. Throughout the 400s BCE, a poem, allegedly written by the mythical musician Orpheus, was in wide circulation. The great Orpheus poem told the story of the creation of the universe. Beginning even earlier than Hesiod’s Theogony, the Orphic creation poem stated that elemental night, rather than Gaia and Ouranos, was the beginning of all things. This Orphic creation poem, and other sacred Orphic writings, have been lost, but we know that sacred scriptures and the interpretation of them were central parts of what we now call Orphic religion. The notion that religion could come from scriptures – even if it were just to the literate minority, still – the notion that religion could come from scriptures was in Euripides’ century something otherwise unattested, and perhaps something unsettling.

The Orphics had a lot in common with the Pythagoreans. They also believed in reincarnation, the immortality of the human soul, and self-regulation. Orphics were vegetarians, and they ate no eggs, and they never partook in alcohol. In the dialogues Cratylus and Phaedo, Plato writes that the Orphics led a life of repentance, and expected little happiness from earthly existence. To Orphics, each person’s body was a phroura, or a guard post, or garrison – a fortress that locked in a soul until it had paid its due. Orphics made themselves content with lives of poverty and contrition, confident that their immortal souls would some day transmigrate into something beyond their present lives.

So the Pythagoreans, and then the Orphics were two major cults in classical Greece, having much in common, but not everything. And this takes us to the third major cult. This was the cult of Dionysus. Athens had a state festival in honor of Dionysus – the city Dionysia, which we’ve been talking about for nine episodes, now. But Dionysus had other rites and rituals, too – secret rites and rituals, involving drunkenness, and sex, and, as is occasionally mentioned in the archaeological record, the eating of raw flesh.5 These celebrations often took place at night, and they were not, like classical Greece’s public and civic rituals, overseen by dynasties of priests and priestesses. They were not in state temples, but often in caves, and scenic glades – places unsupervised by civic authorities. At cult celebrations to Dionysus, adherents went through initiation rituals.

What these rituals were surely varied over the decades, but a surviving text from the 400s BCE suggests the purpose of such initiation rituals. This text says that initiates of Dionysus – those worshippers who had joined the Dionysian cult and completed sacred rites – would be able to take a secret path. They would be able to find a white cypress tree towering over a treacherous pool of water, and – because they had been initiated – they’d be able to speak a secret password, which would lead to their glorification in the afterlife.6 At least some Dionysian initiates, then, in the obscure caves and hollows where they performed their rituals, believed that they had found the key to exclusive, immortal life. [music]

Civic Religion, Cult Religion, and the Bacchae

Eventually, in the final few centuries CE, salvific cult religions pervaded the ancient Mediterranean. Again, in future episodes, we will explore the sea change through which monotheization, and religions focused on the exaltation of the self slowly overtook more fatalistic belief systems with multiple gods.

Gregorio Lazzarini’s Orpheus and the Bacchantes (detail) (c. 1710). Orpheus, much like King Pentheus in the Bacchae, died a grisly death at the hands of intoxicated celebrants of Dionysus.

And theologically speaking, it was equally significant that the cult religions of Ancient Greece invited initiates to think that maybe – hopefully – their humdrum lives in their imperfect polis were only drab preludes to something better. If they didn’t like Thebes, or Athens, or Corinth, it was no matter. They would transmigrate, or possibly take the narrow way of the white cypress in the afterlife, and all of the affairs of their cities and governments would be forgotten soon enough. Just as importantly, they didn’t have to worry about the previously all-important goddess Themis, the upholder of divine order, or the Moirai, the goddesses of fate who ruled over even Zeus. With the right cult initiations, and, for the Pythagoreans and Orphics, a life of dietary regulation and moderation, anyone could usurp the threads of fate and determine her own posthumous existence. That’s the bottom line, really. With these new cult religions, you can see the Homeric worldview, in which we have little control over our fates, and no unchanging immortal essence, giving way to religions like Christianity, in which we have sovereignty over our fates, and eternal souls.

Euripides didn’t know that all around the walls of Athens, the people who were getting tanked and having orgies in caves were part of a slow evolution. He didn’t know that this evolution had begun with the Middle Kingdom of Ancient Egypt – with our Episode 4’s Book of the Dead, where we first see a doctrine of human immortality, and heaven, and a terrible alternative, in the written record. What Euripides witnessed was the early years of monotheization, and the dawn of salvific religions. Euripides concerns himself with Ancient Greek cults in the Bacchae, and also in his earlier play Hippolytus. The cults of Ancient Greece were a real, volatile social issue, warranting commentary by every major writer of the period, and later Plato and Aristotle.

So, knowing all of this, what do we make of Euripides’ Bacchae? Is the play an indictment of cult religion? Is it the opposite – an endorsement of the worship of Dionysus, who reigns supreme at the play’s end? Who is the good guy – coldly rationalistic Pentheus, or wild, subversive Dionysus?

I’m not sure there’s a great answer to this question. Ancient Greek theater generally subverts our expectations of good guys and bad guys, and happy endings and tragic endings. Neither arrogant young Pentheus, nor tyrannical Dionysus, are very appealing characters. Euripides himself had a reputation as a religious iconoclast, and so it’s possible to read the Bacchae as a broadside against religion. In the play, young and old alike are caught up in a cultish fervor, bedecking themselves with ivy and speaking with increasing ecstasy about the ascendancy of their god. Pentheus is an arrogant young man, but his death is so grisly that Dionysus, in demanding it, becomes a distinctly tyrannical and unappealing figure. At the same time, though, wrathful gods and hubristic mortals are the bread and butter of ancient Greek tragedy, and so it’s equally possible to understand the Bacchae as a fairly standard story of a vaunting king who doesn’t pay heed to divine power. The story premiered at a festival of Dionysus, and thus it would have been a strange showcase for anti-Dionysian sentiments.

The Bacchae contains both religious conservatism and religious skepticism. In doing so, the play chronicles a real historical phenomenon. There were accepted civic holidays and rituals in Athens that honored the Olympians and their descendants. And then there was edgy stuff – cult stuff, where participants got together in private, and underwent rituals focused on the individual more than the civilizational collective. The Bacchae doesn’t valorize disbelief in the gods. But the play is also pointedly squeamish about the spread of cult religions like that of Dionysus, religions that, regardless of state regulations and social norms, were everywhere spreading out of control. [music]

Dionysus Zagreus, Saviors, and Communion

Now, I have one final thing to offer in this program – that thing I said I thought you might find astounding – that final anecdote about Dionysus, or, as he was called in a Bronze Age Linear B tablet, di-wo-nu-so-jo. There was a religious tradition alive and well during Euripides’ time – and it was alive in Orphism as well as the worship of Dionysus. And this tradition was that the main cult figure of each religion, whether Orpheus or Dionysus, had died in a particularly gruesome way. According to a lost play by Aeschylus, Orpheus, the demigod of music, had scorned Dionysus, instead worshipping Apollo. As punishment, Dionysus sent a swarm of maenad women to Orpheus, and Orpheus was torn to shreds, just as Pentheus is murdered in the Bacchae. So, one of the reasons that Orphics had such strict dietary regulations was their sense of guilt and loathing toward the material world, because the material world had murdered their muse.Orpheus, then, was a demigod who had had a horrible death. And Ancient Greek religion deals with the death of another god – this one Dionysus himself. Now, I know we’ve been at it for a little while, but still – this part may be the most fascinating and memorable of the show for you. The story of Dionysus’ mother Semele being killed and then Dionysus being born from Zeus’ thigh or scrotum wasn’t the only tale of Dionysus’ birth. There was another story – a version of the story that began proliferating, we think, later in Ancient Greek history, in a lost text called the Rhapsodies.

The other legend of Dionysus’ birth is as dark and bloody as anything we’ve heard today. This other legend tells of a version of Dionysus called Dionysus Zagreus, or sometimes just Zagreus. And in this alternate legend, the Theban princess Semele is not Dionysus’ mother. In this second origin legend, Zeus raped his mother, Rhea. Rhea gave birth to Persephone. Zeus then raped his sister slash daughter. Persephone then gave birth to Dionysus, who was Zeus’ son, and grandson, and nephew. Zeus then handed over control of the earth to young Dionysus Zagreus. After these events, Hera was jealous that another woman had borne Zeus a son. And so Hera had titans trick young Dionysus into being inattentive, and then young Dionysus, like Pentheus, and like Orpheus, was torn to pieces. Dionysus was then boiled and eaten by the titans. Zeus, when he found out about the awful crime, became so furious that he struck the violent titans with a thunderbolt, and from the ashes and cinders came mankind – whose birth was made possible by Dionysus’ divine sacrifice. Dionysus Zagreus wasn’t gone for good, however. A few bloody scraps survived the ravages of the titans, and those scraps arose again to become Dionysus, reborn. This myth was well-known by the 200s BCE, and evidence exists suggesting that it was already in circulation as early as the late 500s BCE, a story about a god, who was the son of a god, who died so that mankind could live, and then was resurrected.7

The story of the death of a divine son was an old one during the classical period. The ancient Egyptian tale of Osiris, a god torn to pieces and reconstituted by his sister and wife Isis, had existed since the 2000s BCE. The tale of the death and rise of Inanna’s husband Dumuzi was the Mesopotamian version of the same story. And just as dead savior gods returned to life were a very old story, so, too, were rituals honoring those dead savior gods. In antiquity, a ritual existed by the time of the ancient historian Diodorus of Sicily, a man who lived a few decades before the Common Era. By this time, say, 30 BCE in the ancient Mediterranean, the myth of Dionysus’ death and resurrection was pervasive enough that rituals to Dionysus invoked wine as the blood of Dionysus. Initiates in the Dionysian cult drank the blood of Dionysus at his annual rituals – especially the springtime Anthesteria festival, to honor Dionysus’ horrible pain, and his sacrifice. If men and women believed the old story of Dionysus, then drinking the blood of Dionysus was a way of honoring the sacrifice that he had made, so that they, too, could rise from the ashes of the titans.

A group of Catholics take communion at a mass in Summit, New Jersey. The practice of eating and drinking consecrated food and wine has roots in the Bronze Age.

Moving on to Aristophanes

Well, folks, I think eight Ancient Greek tragedies is enough for now. Out of the 32 or so great Athenian tragedies that survive – seven by Aeschylus, seven by Sophocles, and eighteen by Euripides, we’ve covered eight – just a quarter of them, but quite a good quarter to cover. The Oresteia, the three Theban plays, and then Medea and the Bacchae – these have been very influential tales over the past 2,400 years. After tragedy comes, of course, some comedy. And in the next show, we’re going to read the first of two plays by the comedic playwright Aristophanes, possibly the most famous funnyman of the ancient world. Aristophanes’ play The Clouds is a rip-roaring satire about certain strange intellectual fads that were blazing through Athens at the end of the 400s. And one of its main characters is a certain obscure, seldom mentioned ancient Greek philosopher named Socrates. So join me in Episode 35 for The Clouds, a play with fart jokes, grotesque x-rated humor, fake penises, no holds barred satirical beat downs, and – amidst all of this – a surprisingly rich portrait of the intellectual culture of wartime Athens. Thanks for listening to Literature and History. There’s a quiz on this program if you’d like to do a quick review – just check the notes section of your podcast app. If you want to hear a song, stay on for just a moment longer, because I’ve got a good one for you, and if not, Aristophanes and I will see you soon. Still listening? So I got to thinking. I got to thinking about Dionysus, and I’ve been listening to a ton of old school hip hop lately. And I wondered what it would sound like if Dionysus were given a job interview, and this job interview were spontaneously interrupted by a hip hop anthem, in which Dionysus, god of wine and madness and ecstasy, took it upon himself to offer a discourse on his life philosophy. Got to thinking about all that, and I wrote this song – it’s called “Interview with Dionysus.” Hope you like it, and again I’ll be back soon with Aristophanes’ Clouds.References

2.^ See Chadwick, John and Ventris, Michael. Documents in Mycenaean Greek. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1974, p. 127. The authors note the source of this name as fragment Xa06.

3.^ See Burkert, Walter. Greek Religion: Archaic and Classical. Maiden, MA: Blackwell Publishing, 1988, p. 44.

5.^ Ibid, p. 291.

6.^ Ibid, pp. 293-5.

7.^ For a longer discussion of this see Burkert (1988) pp. 297-8.