Episode 116: The Life of Muhammad, Part 3: Conquest

Between 622 and 628, Muhammad and the first Muslims made a home from themselves in Medina, fended off assaults from the Quraysh and others, and changed the course of history forever.

| Read Transcription | References and Notes |

| Quiz | |

| Episode on Spotify | Episode on Apple Podcasts |

| Previous Show | Next Show |

Episode 116: The Life of Muhammad, Part 3: Conquest

Gold Sponsors

David Love

Andy Olson

Andy Qualls

Bill Harris

Christophe Mandy

Jeremy Hanks

Laurent Callot

Maddao

ml cohen

Nate Stevens

Olga Gologan

Steve baldwin

Silver Sponsors

Lauris van Rijn

Alexander D Silver

Boaz Munro

Charlie Wilson

Danny Sherrard

David

Devri K Owen

Ellen Ivens

Evasive Species

Hannah

Jennifer Deegan

John Weretka

Jonathan Thomas

Michael Davis

Michael Sanchez

Mike Roach

rebye

Susan Hall

Top Clean

Sponsors

Katherine Proctor

Carl-Henrik Naucler

Joseph Maltby

Stephen Connelly

Chris Guest

Matt Edwards

A Chowdhury

A. Jesse Jiryu Davis

Aaron Burda

Abdul the Magnificent

Aksel Gundersen Kolsung

Alex Metricarti

Andrew Dunn

Anthony Tumbarello

Ariela Kilinsky

Arvind Subramanian

Basak Balkan

Bendta Schroeder

Benjamin Bartemes

Brian Conn

Carl Silva

Charles Hayes

Chief Brody

Chris Auriemma

Chris Brademeyer

Chris Ritter

Chris Tanzola

Christopher Centamore

Chuck

Cody Moore

Daniel Stipe

David Macher

David Stewart

Denim Wizard

Doug Sovde

Earl Killian

Elijah Peterson

Eliza Turner

Elizabeth Lowe

Eric McDowell

Erik Trewitt

Francine

FuzzyKittens

Garlonga

Glenn McQuaig

J.W. Uijting

Jacob Elster

James McGee

Jason Davidoff

Jay Cassidy

JD Mal

Jill Palethorpe

Joan Harrington

joanna jansen

Joe Purden

John Barch

john kabasakalis

John-Daniel Encel

Jonah Newman

Jonathan Whitmore

Jonathon Lance

Joran Tibor

Joseph Flynn

Joshua Edson

Joshua Hardy

Julius Barbanel

Kathrin Lichtenberg

Kathy Chapman

Kyle Pustola

Lat Resnik

Laura Ormsby

Le Tran-Thi

Leonardo Betzler

Maria Anna Karga

Marieke Knol

Mark Griggs

MarkV

Matt Hamblen

Maury K Kemper

Michael

Mike Beard

Mike Sharland

Mike White

Morten Rasmussen

Mr Jim

Nassef Perdomo

Neil Patten

Nick

noah brody

Oli Pate

Oliver

Pat

Paul Camp

Pete Parker

pfschmywngzt

Richard Greydanus

Riley Bahre

Robert Auers

Robert Brucato

De Sulis Minerva

Rosa

Ryan Goodrich

Ryan Shaffer

Ryan Walsh

Ryan Walsh

Shaun

Shaun Walbridge

Sherry B

Sonya Andrews

stacy steiner

Steve Grieder

Steven Laden

Stijn van Dooren

SUSAN ANGLES

susan butterick

Ted Humphrey

The Curator

Thomas Bergman

Thomas Leech

Thomas Liekens

Thomas Skousen

Tim Rosolino

Tom Wilson

Torakoro

Trey Allen

Troy

Valentina Tondato Da Ruos

vika

Vincent

William Coughlin

Xylem

Zak Gillman

In the previous two episodes, we learned about how Muhammad went from being an orphan and laborer in the Hijaz caravan circuit, to being a respected trading agent, a husband and father, a reluctant recipient of divine revelations, and then a prophet, a polarizing preacher, an outlaw, and after the Hijra of 622, the leader of an exiled community, a legislator, and a general. His story is a long and complex one, often made more so by the massive quantity of writings set down about him, especially during the 800s. Though the source materials we have on Muhammad are complex, and though they were set down centuries after he lived, they demonstrate two overarching facts about the Prophet of Islam. Muhammad was a person of considerable intelligence and will. And he saw the tribal power blocs into which Arabia had been organized since time immemorial and imagined a different future for the Peninsula, and for the world.

For this episode, as with the previous two, our source materials are a number of different biographies, some modern and academic, and others from the early medieval period, as well as hadiths, those short prophetic narratives capturing sayings and deeds of the Prophet Muhammad. The Muslim scholars who recorded the events of Muhammad’s life, especially during the 800s, were people of faith. They were also, however, reasonably academic by the standards of antiquity, citing sources for stories, and frequently calling into question the more miraculous elements of prophetic biography. Thus, over the next two hours, you will hear some miracle stories and some narratives involving magic and the supernatural. I do not personally know whether, for instance, Muhammad brought water out of the dry ground near Mecca during an attempted pilgrimage in 628, nor whether he faced off against a sorcerer in Medina later that year – we’ll hear these stories momentarily. I do know, however, that these narratives are a part of Islamic tradition, and as cultural history is this podcast’s domain, it is my job to present them here. If you’re curious about any element of prophetic biography that comes up, the transcription for this episode, available in your podcast app, has notes on sources, and I invite you to take a look at the sources for yourself, too.

If you want to hear Muhammad’s story from the beginning, we started it two programs ago in Episode 114. As for the present episode, let’s jump right back in to about April of 627. In April of 627, the Meccan-led confederation that besieged and attempted to destroy Yathrib was unable to take the city. Following the Battle of the Trench, and its bloody aftermath, Muhammad had a dream. He dreamt that he entered the Kaaba of Mecca during the annual pilgrimage there, with his head shaved, and in this dream, Muhammad held the key to the Kaaba.1 This dream prompted Muhammad to make an announcement. Although the Quraysh tribe that ruled over Mecca had just made war on the mu’minun, or believers of Islam, Muhammad would go to Mecca. There, safeguarded by the city’s sacred customs of nonviolence toward pilgrims, he would undertake a pilgrimage. The Prophet’s companions, hearing the announcement, however unexpected it was, and although it involved no small amount of risk, prepared to join him. [music]

The journey to Mecca would be a dangerous one, and everybody going along knew it. The future caliph Umar suggested that they bring weapons, but Muhammad refused. And so, bareheaded and dressed in the simple garb of a pilgrim, the Prophet led the way southward. Those who had left Mecca hadn’t seen home for almost six years. All told, about a thousand believers from Yathrib made their way south to Mecca in March of 628, and the news of their departure caused no small consternation for the Quraysh Meccans who had so recently faced them in battle. If the mu’minun came to Mecca as pilgrims, the Quraysh leaders thought, if the Muslims peacefully entered the city to perform the religious rites customary in Mecca, then the Quraysh oligarchy would face two setbacks. First, Muhammad and his followers would enter their city freely, while the Quraysh themselves had not been able to enter Yathrib. Second, if the Muslims peacefully undertook the customary rituals of the pilgrimage, then it would be harder to vilify them as impious interlopers.

The journey south was a harrowing one. The Quraysh leaders who opposed the Muslims set up a force of 200 cavalrymen to intercept Muhammad and his followers, but, taking a circuitous route, the mu’minun wound up through the dry hills, and a miracle story survives about Muhammad getting his companions plentiful fresh water to drink from the stagnant hollows of this high country. The Prophet learned that the Quraysh planned to bar them entry from Mecca. He said that the mu’minun had come only to pay their respects as pilgrims. They would fight the Quraysh if they had to, but first, Muhammad said, the Muslims would give the Quraysh opposition time to reflect and come up with a decision.

As the hours passed, and the Quraysh sent emissaries to the believers, the Quraysh found their standing quickly deteriorating. Muhammad’s mere presence in the region around Mecca was a threat, even if he just camped there on the city’s outskirts, talking to people and being himself. Everyone who went to speak with Muhammad – a Bedouin envoy named Ahabish, for instance, and a tribesman named ‘Urwah – came away with a singularly favorable impression of him. The Muslims, awaiting the Quraysh’s verdict on whether or not they could enter Mecca, sent their own envoy to the Quraysh, and he was nearly killed. Then the believers decided to send the future caliph Uthman. Uthman, a man with power and wealth, was an esteemed figure whose highborn stature gave even the hostile Quraysh pause, and the Meccans offered to let Uthman enter the city and perform his pilgrimage rites. Uthman refused, though, out of solidarity with the other believers still stationed outside of the city.

The Quraysh, finding that barring the mu’minun from entering would be as untenable as allowing them to perform their pilgrimage rites in Mecca, decided on another option. They sent a leader named Suhayl ibn Amr, and after some negotiations, the believers and the Quraysh entered into what is today known as the Treaty of al-Hudaybiyah. This treaty was a peace pact. Both sides pledged nonviolence for a period of ten years. The mu’minun agreed to go home, on the contingency that they could come the following year to make their pilgrimage, during which the Quraysh would leave the city. There was another agreement as well, and it was less symmetrical. The parties decreed that anyone who defected from the Quraysh without permission from guardians – any minors, for instance, who went to join Muhammad in Yathrib – would be sent back to Mecca. However, by accordance of the treaty, any believers who left Yathrib to join the Quraysh would not be sent back to Muhammad.

Though inequitable in its terms, the treaty was still, ultimately, advantageous to Muhammad and his people. The agreement meant that the Quraysh were treating the Muslims as an equal regional power. But a crisis immediately unfolded. The son of Suhayl ibn Amr, that Quraysh chief with whom Muhammad had just negotiated, wanted to go with the mu’minun. There was some gray area as to whether the young man was allowed to join the Muslims, but Muhammad opted to honor the terms of the recent treaty, and he sent the young man back to Mecca. Stationed there, outside of Mecca, and being unable to enter, some of the Muslims were distinctly unhappy with the situation – going all the way to Mecca and signing an inequitable treaty had not been their goals when they had dressed as pilgrims, and the future caliph Umar, especially, was piqued. Morale, as the pilgrims headed home back to Yathrib or Medina, was low in the ranks of the believers, but they shaved their heads there in the countryside outside of Mecca, as was the custom for an actual pilgrimage, and they began making their way back up to Yathrib. Umar, penitent that he had expressed dissatisfaction with Muhammad, was worried when the Prophet had a revelation on the road home. But the revelation was a general reassurance rather than any condemnation of those who had questioned him. The revelation, as printed in Surat al-Fath in the Qur’an, is as follows: “Truly We have opened up a path to clear triumph for you [Prophet]. . .God was pleased with the believers when they swore allegiance. . .under the tree. . .you will most certainly enter the Sacred Mosque in safety, shaven-headed or with cropped hair, without fear!” (48.1,18,27).2

Peace and War: The Treaty of al-Hudaybiyah and the Northern Conquests of 628

Bilal ibn Rabah atop Kaaaba in 628 in a medieval Turkish illustration. This would have been a very tense moment, though it was also a triumphant one in Islamic history.

The Prophet soon exploited another gray area in the treaty. Women had not been mentioned in it. A convert – the half-sister of the future caliph Umar – wanted to come up and live in Yathrib, and Muhammad decided that she would stay. The Quraysh allowed this to pass. For the mu’minun, then, the real victory after the peace treaty of 628 was that the communities of Yathrib and Mecca could meet and intermingle more freely. As they did so, more and more Meccans became interested in Islam, and the community of the mu’minun, in just two years time, following the peace treaty, soon doubled.3

In fact, this – and we’re in the spring of 628 – this was the moment at which, in the ninth-century historians and those who followed them, Islam began to expand far beyond the date orchards of Yathrib, or Medina, and the rocky slopes and valleys around Mecca. Muhammad’s horizons, during the opening months of the treaty, had widened in scope. He learned that his cousin in Axum, over in Ethiopia, had passed away, leaving behind him a wife named Umm Habiba. Umm Habiba was a Muslim, and the daughter of the Quraysh leader Abu Sufyan. The Prophet proposed marriage to Umm Habiba via a letter over the Red Sea, and she accepted, becoming Muhammad’s ninth wife in a ceremony at which the Prophet himself wasn’t actually present. Afterward, a number of the prominent mu’minun who lived in Ethiopia came to live in Yathrib, including Muhammad’s new wife Umm Habiba.

Muhammad, at this time, also dispatched a letter to Khosrow II, the Sasanian king, urging the Persian monarch to accept Islam. This dispatch to the Sasanian Empire, at least, seems to have been received. Yemen, at that point, was ruled by a Persian viceroy. Khosrow II, who had heard that a new regional power had grown in Medina, sent emissaries from his Yemeni governor to meet with Muhammad. According to tradition, Muhammad had a vision that Khosrow II had died. Muhammad told the Yemeni envoys of his vision. The Persian envoys went home to Yemen, and when the vision was confirmed to be true, the governor who ruled Yemen on behalf of the Sasanian empire was stunned. As the historian al-Tabari tells us, “When [news of Khosrow II’s death] reached [the governor of Yemen], he said, ‘This man is indeed a messenger,’ and he became a Muslim, and. . .those from Persia who were in Yemen. . .became Muslims with him.”4 This story, by the way, is told very briskly in the early biographies as an almost foregone conclusion, it’s chronology is suspicious, and the Sasanian empire was in the midst of utter chaos in 628, so it seems doubtful that Khosrow II or any Sasanian grandees would have time to parley with the modestly sized new theocratic state in Medina.5 But however it really happened, with Islam expanding as it was, some conversions in Yemen, perhaps some high profile ones, started bringing the commercially important heel of the Arabian Peninsula into Muhammad’s sphere of operations.

The Sasanian Empire at its absolute apex, just as Heraclius began clawing back territory in an incredible reversal of fortunes. While the traditional Islamic sources likely exaggerate the Yemeni Persian government’s ready conversion to Islam, the Persian state was, in the 620s, more fragmented than this map might indicate, and after Khosrow II lost the war in 628, the empire dissolved into feudal regions that became ripe for Islamic conquest during the next decade.

With Labid thus neutralized, Muhammad could turn his attention elsewhere. Mecca, which had been the most existential threat for the believers of Medina, was now under a truce. Further to the south, the territory of Yemen was now allied with the believers. But closer at hand, to the north, was the oasis town of Khaybar. Khaybar was about 90 miles north of Medina. Khaybar had, during the second half of the 620s, become a place where some of Muhammad’s more powerful adversaries congregated. Specifically, the Jewish Nadir tribe had taken up residence there. Muhammad had exiled them from Medina in the summer of 625, and following their ouster, in the years since, they had continued to work against the Prophet, wrangling their northern allies, including the Quraysh, to attack the Muslims of Medina in the spring of 627 at the Battle of the Trench. It was now the spring of 628, and Muhammad decided to take advantage of the armistice to the south in order to campaign against foes in the north.

Khaybar would prove to be an important, but dangerous conquest. Muhammad himself set some unusual rules for the campaign to the north. Some Bedouin allies of the mu’minun had refused to go on the pilgrimage down to Mecca, as the pilgrimage would not be a lucrative mission. Muhammad announced that only those believers who had gone on the pilgrimage would be allowed to go on the northern campaign to sack Khaybar. This meant that the northbound force would be a small one. In spite of the relatively small size of the northbound army, the news of the impending attack worried the Jews who still lived in Medina. They feared that any Muslim who owed them money would refuse to pay it back if Khaybar fell.7 At the same time, they suspected that the Muslims would have a hard time sacking Khaybar. One Jewish man of Medina warned the Muslims, “Do you think that fighting Khaybar is like fighting among the Arabs? By the Torah, in it are ten thousand warriors!”8 Indeed, the general consensus of the Jewish community of Medina was that Muhammad would run into trouble up in the oasis town, which had ten thousand armored men, mountaintop fortresses supplied with fresh water, and Bedouin allies, too.

These were menacing warnings, as they survive in the very early historian al-Waqidi, but as we read of the campaign in the biographies of ibn Ishaq and al-Tabari, the Muslims seem not to have faced a particularly unified enemy at first. Khaybar’s Bedouin allies became worried that they were being attacked from the rear, and so they didn’t show up to the battle. In fact, let me read you what the ninth century historian al-Tabari writes on the subject.

It has been reported to me that, when [the Arab] Ghatafān [tribe] heard that [Muhamad] had been encamped near Khaybar, they assembled because of him and set out to aid the Jews against him. Having traveled a day’s journey, they heard a sound behind them in their possessions and families. Thinking that the enemy had come at them from behind, they turned back and stayed with their families and possessions, leaving the way to Khaybar open to [Muhammad].9

That’s the story about the major Arab ally of the Jewish tribes of Khaybar – the Ghatafan tribe was going to go and fight the Muslims of Medina, but then they – they heard a noise, and so they didn’t make it. You can and should read into, and second guess the primary texts of the ninth century historians – I only quoted that passage to remind you once again that Muhammad’s story comes down to us via a very broad and uneven tapestry of texts and traditions. So, let’s learn what happened when the Muslims attacked Khaybar, as best as we can from the surviving texts.

Map of the regions of Arabia, by Goran_tek-en. The Khaybar oasis is right where the word “Hijaz” is on the map just north of Medina. Medina’s central location in the west made it vulnerable to attacks from multiple directions, including, importantly, the Najd to the east, whose inhabitants Muhammad had to deal with deftly over the course of his career.

One major stronghold remained. It was the stronghold of the exiled Banu Nadir – the tribe that Muhammad had forced out of Medina three years prior. With the rest of Khaybar now under Muslim control, and Bedouin allies nowhere to be seen, the Jews of the Nadir tribe felt that they had no choice but to negotiate. Muhammad, when it was proposed, said that the Jewish tribe’s lives would be spared, and they and their families could flee elsewhere. The chief of the Nadir tribe said that the Muslims could take all of their property. Muhammad added a clause to this agreement. If it were discovered that the Nadir tribe were hiding possessions as they made their way out of Khaybar, then the nonviolence pact was forfeit. Everyone agreed to the armistice.

As it turned out, though, the Jewish tribespeople, under the direction of their chief, did end up hiding some wealth away, and soon their secreted riches were discovered. Muhammad had the Nadir chief put to death, together with the chief’s cousin, and their families became the Muslims’ captives. The fall of the Nadir tribe’s fortress broke the back of Khaybar’s resistance. There were other fortresses, but they were smaller. The Jewish tribespeople of the oasis town brokered agreements with Muhammad, telling the Prophet that their expertise was necessary to best run their plantations, and asking if they might remain on their land, paying him half of their income as a tax. Muhammad agreed, with the stipulation that he could banish them at any time. The Muslims had planned to turn their conquest north after this, to a small neighboring oasis. But the inhabitants of this second oasis, also Jewish orchard owners, preemptively told Muhammad they’d just pay him half of their income in order to avoid any violent confrontation, and Muhammad agreed to these terms. Another Jewish settlement nearby, when the Muslims marched toward them, capitulated under the same terms.

Following the incredible success of their conquests in and around Khaybar, the Muslims turned back toward Medina. On the way there, Muhammad married his tenth wife. Her name was Safiyyah, and she was a beautiful Jewish girl and the widow of the Nadir chief whom the Prophet had just ordered executed. She was also the daughter of a former head of the Jewish Qurayza tribe, a man Muhammad had also ordered executed. Safiyyah was at first given to Muhammad as a slave, but when he offered her the opportunity to be free and be his wife, she accepted. The girl’s plight – marrying the man responsible for her husband’s and father’s deaths – does not sound like an enviable one. But there’s some evidence that Safiyyah was unhappily married and perhaps even interested in Islam prior to the Muslim conquest of the Khaybar oasis. The historian al-Tabari tells us that, before Muhammad showed up, Safiyyah dreamt of a moon falling on her lap, and her husband gave her a black eye, telling her she was dreaming of Muhammad.10 The historian ibn Sa’d emphasizes Muhammad “gave [Safiyyah] her liberty as her dowry.”11 Whatever Safiyyah’s exact thoughts were, she became Muhammad’s tenth wife, and the couple consummated the marriage on the road back to Medina. [music]

628-9: Complexities in the Prophet’s Household

Upon returning to Medina, Muhammad brought the Jewish beauty Safiyyah into a household that included seven other wives. (Remember that the Prophet’s wives Khadija and Zaynab had passed away by this point – in other words out of the ten that he’d married, eight were still left) Also, somewhat awkwardly, the Prophet’s ninth wife, Umm Habibah, whom he’d married by proxy in Ethiopia, had come to join him, too, and this was their first meeting as husband and wife. For the most part, Muhammad’s wives were a harmonious social unit. They were mostly Meccans, and kinfolk, and had known one another for a long time. Only Safiyyah, among them, was a pariah. First, she was Jewish, though she had converted to Islam. Second, she was really beautiful. Only Aisha was younger than her. As time passed, though, Aisha and Safiyyah became friends, and the eight wives socialized with one another politely enough according to age group and natural chemistry. Aisha, who was sixteen at that point, left behind many hadiths, and she said that the only wife toward whom she really felt any jealousy was Muhammad’s first wife, Khadija.12Aisha, according to tradition, was generally understood to be the Prophet’s favorite wife. A hadith survives in which Muhammad said he only had revelations while in bed with Aisha.13 Though there were various jealousies and factions in his large household, Muhammad did his best to be diplomatic, trying to lavish attention on each wife, and always doting on his grandchildren. Muhammad may have been able to spend a bit more time at home after the Khaybar campaign, as the Muslims’ resources had grown, and the Prophet’s principal lieutenants were becoming adept leaders in their own right.

The future caliphs Umar and Abu Bakr led campaigns to help clear the lower Hijaz roads of highwaymen and raiding parties. Muhammad stayed in Medina for nine months, and 628 gave way to 629. Although he had some respite during this period, with peace and relative prosperity, there also came new challenges as a leader. Scarcity and frequent emergencies had, prior to the Khaybar conquests, made Muhammad very frugal in the way that he managed his household. With some surplus income, though, the Prophet bought gifts for wives, children, and grandchildren, and buying a present for one meant that an equitable present for all the rest had to be procured. The future caliph Umar heard that Muhammad’s wives were being rather pert and presumptuous with the Prophet. Umar, who was the father of one of Muhammad’s wives and the cousin of another, confronted his cousin, and she said that indeed, Muhammad’s wives spoke their minds to him, and that Umar shouldn’t come between the messenger of God and his wives. The future caliph decided he’d take his cousin’s advice, and Umar butted out.

A more severe household crisis than this soon ensued, though. Muhammad had some time ago sent a letter to the leader of Egypt, likely a Byzantine governor, introducing himself and urging the governor to accept Islam. No reply had arrived for some time, until a shipment of generous gifts arrived, including two beautiful Coptic Christian slave girls. Muhammad particularly liked one of the slaves, a girl named Mariyah, and began spending a great deal of time with her. Just to be clear, by the way, sex slavery was pervasive in Late Antique Arabian society, just as it would be during the caliphates. Muhammad’s wives, though, resented him disrupting his regular rounds of spending time with each in order to devote so many nights to a Christian slave girl. His young wives Aisha and Hafsa were especially resentful, and toward these wives, according to some traditions, Muhammad had the following revelation. As Surat al-Tahrim in the Qur’an says,

Prophet, why do you prohibit what God has made lawful to you in your desire to please your wives?. . .If both of you [wives] repent to God – for your hearts have deviated – [all will be well]; if you [wives] collaborate against him, [be warned that] God will aid him, as will Gabriel and all righteous believers, and the angels too will back him. His Lord may well replace you with better wives if the Prophet decides to divorce you. (66.1,4-5)14

These were harsh words – an ultimatum, telling his outspoken wives to let him do the things that God had decreed were lawful – or else he would divorce them. The statement nearly caused a catastrophe. Muhammad’s entire octet of wives became convinced that the Prophet was divorcing all of them. But when the future caliph Umar came to talk with Muhammad, he learned that this was not the case, and soon, Muhammad reconciled with his wives. It may have been on this occasion that another Qur’anic revelation came to him: “Prophet, say to your wives, ‘If your desire is for the present life and its finery, then come, I will make provision for you and release you with kindness, but if you desire God, His Messenger, and the Final Home, then remember that God has prepared great rewards for those of you who do good’” (33.28-9).15 Muhammad’s wives, it seems, chose the latter. [music]

The Muslims Enter Mecca Under Armistice with the Quraysh

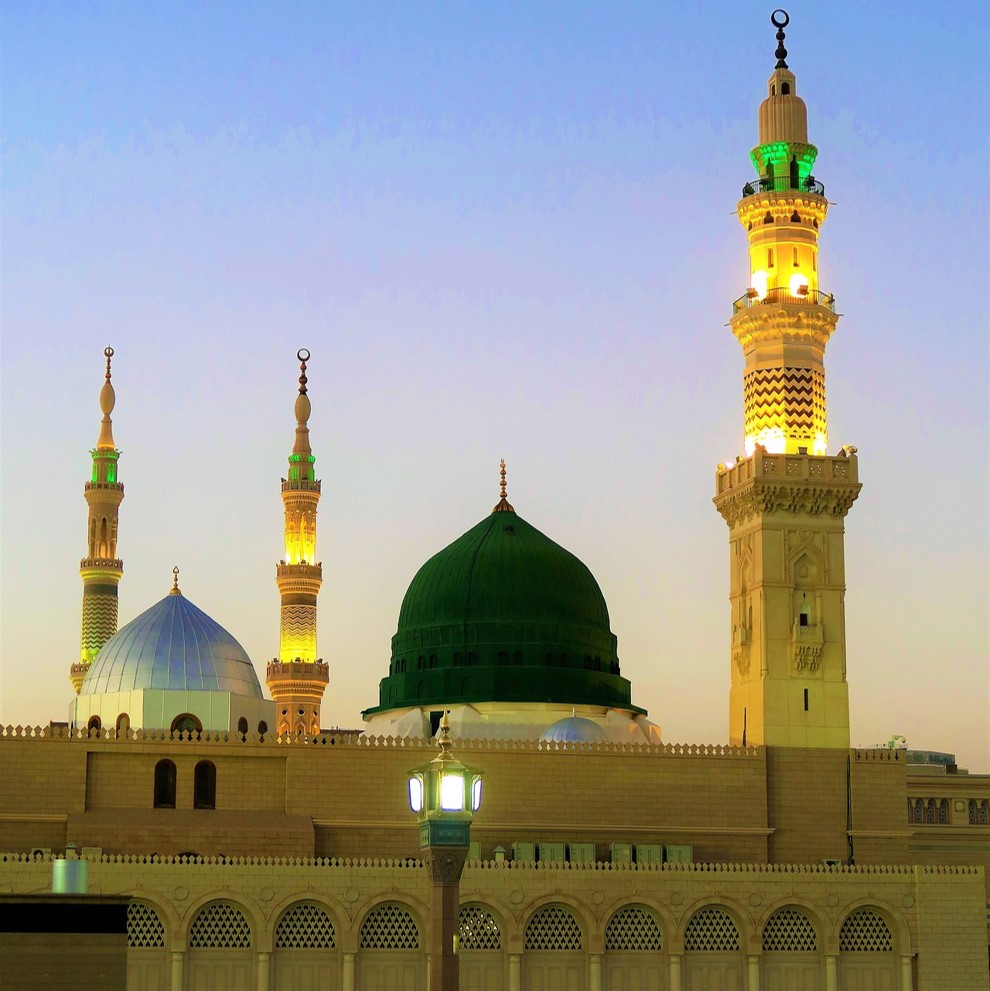

It had been about a year, now, since Muhammad had gone down to Mecca as a pilgrim, and then agreed to return to Medina and postpone his Meccan pilgrimage. Thus, according to what the Quraysh had agreed, he and his fellow Muslims could now perform their pilgrimage rites. Clad in the simple white garb of pilgrims, the believers then made their way south from Medina to Mecca, and the Quraysh chiefs saw them approaching from a long way off. Unobstructed this time, the Muslim pilgrims made their way to the Kaaba, and the Prophet, not having dismounted from his trusty camel Qaswa, touched the sacred Black Stone and undertook his seven circuits around the shrine.Muhammad then wanted to enter the Kaaba. He had dreamt, the previous year, of entering the shrine with the shorn hair and white garments of a pilgrim, and now expected to do so. The Quraysh, however, told Muhammad that entering the shrine was not permissible. The keepers of the Kaaba had authorized the Prophet’s pilgrimage, but not the special prerogative of entering the building. And so rather than entering, the Muslims had their muezzin Bilal ascend to the roof of the Kaaba and then announce the call to prayer. The Quraysh were deeply displeased at this. Bilal was black, and a former slave. And the words of the call to prayer, “I testify that there is no god but God. I testify that Muhammad is the messenger of God,” the same in March of 629 as they are today, were sacrilegious by the standards of the polytheistic Meccan establishment. Muhammad, the Quraysh leaders understood, had enjoyed a significant victory even as an unarmed pilgrim, proclaiming Islam from the roof of the Kaaba itself.

The Muslims spent three days in Mecca, and numerous joyous reunions were possible as a result of their time there. Many of the believers were Meccan to begin with, and so they were able to see friends and family from whom they’d been separated for a long time. Muhammad got to spend time with a paternal uncle, Abbas, who, although a Muslim, had been able to live in Mecca. Abbas told Muhammad that Muhammad ought to marry Abbas’ widowed sister-in-law. Her name was Maymunah, and she became the Prophet’s eleventh wife. The exact number of women Muhammad married is something about which historians are uncertain. Especially with Muhammad’s concubines Rayhana, the Jewish girl he’d taken as a prize after the massacre of the Qurayza in 627, and then Mariyah, the Coptic Christian slave girl from Egypt sent to him as a present in early 629, some traditions hold that he married one or the other or both, and some, that they remained slaves. The marriage to Maymunah in Mecca was probably a strategic one, in part, as it gave him a connection to the leader of a powerful enemy clan.16

All told, the three days that the Muslims had been permitted to spend in Mecca passed by quickly, and soon, the Quraysh made it clear that it was time for Muhammad to go back to Medina, as per the treaty both parties had signed. Though the Quraysh chiefs made sure that Muhammad kept up his bargain and left the city, among the leaders of Mecca, fissures were beginning to show in regard to opinions about the Prophet. Muhammad, after all, wasn’t some stranger. He was one of them – a Meccan. By blood and marriage he was thoroughly connected with Mecca’s power brokers. Apart from his unorthodox religious ideas, Muhammad was a considerate, diplomatic person, politely asking after old friends and family whom he hadn’t seen in a while, and as his success increased in the north and south alike, it was becoming harder and harder for the Meccan establishment to dismiss him as a swindler or heretic. A powerful cavalryman named Khalid ibn al-Walid, though he’d been instrumental to Muhammad’s defeat at the Battle of Uhud, was no longer so diametrically opposed to the Prophet as he’d been before, and after a dream, Khalid decided to defect from Mecca and head up north to join Muhammad – Khalid, as I noted last time, would soon be one of the greatest generals in world history.

A terrific photo of the door of the Kaaba with the Mecca Royal Clock Tower in the background, by the Saudi Press Agency. Muhammad was barred from entering the sacred shrine in 629.

With these gains for the Prophet, there came a loss. His oldest daughter Zaynab passed away. She was in her early twenties, and so her death hit him hard. Around this same time, though, Muhammad had a son. His slave and possibly wife, the Egyptian Christian girl Mariyah, gave birth to a baby boy. This was a big deal. Muhammad had an adopted son, Zayd, and a revered son-in-law, Ali. He had two grandsons, Hasan and Husayn, but in spite of having many wives, he’d never had a son who’d lived to adulthood. Everyone knew that if Muhammad passed away without a clear male heir, things could get complicated, and so, as of the spring of 629, the Medinans looked with great favor on Mariyah for giving the Prophet a son. [music]

Muslim Encounters with the Byzantines and Axumites in 629

In the summer of 629, with so much of the Hijaz under Muhammad’s control, he turned his attention north, toward what is today southern Syria. A peaceful contingent of fifteen Muslims were sent up to Syria to inform the region about Islam, but they were attacked and nearly massacred. Another messenger was captured and killed. Muhammad, in response, mustered an army of 3,000 men, commanded by his adopted son Zayd.

A map of the Heraclius’ campaigns at the close of the Byzantine-Sasanian War of 602-628, done by Mohammad Adil. The troop numbers in the traditional Islamic sources for the Battle of Mu’tah are almost certainly exaggerated, but, considering how absolutely battered and exhausted the Byzantine forces must have been by 629 (after all of the arrows on this map!), it’s certainly possible that Muslims won an underdog victory against some unprepared Romans.

In the aftermath of this engagement, Muhammad was heartbroken. He’d lost an adopted son, and he’d known and trusted Ja’far for decades. But the Prophet had a consolation. He had a dream in which he saw those who had died in the battle enjoying the pleasures of paradise, having been martyrs to the cause of Islam.

The Battle of Mu’tah was the beginning, and not the end, of what would prove to be a great many military conflicts that early Islamic armies would fight up in what is today Jordan and Syria. Muhammad’s military presence in the Hijaz region was becoming difficult to ignore for the Byzantines. The Byzantine Emperor Heraclius, as of the final months of 629 when the Battle of Mu’tah took place, was riding high. The Byzantine Emperor Heraclius had, in the last days of the Byzantine-Sasanian War of 602-628, obtained a relic called the True Cross from the Sasanians, and brought it back to Jerusalem. It was around this time that the Byzantine Emperor Heraclius, at least according to Islamic historians writing two centuries after the fact, had a dream. The next morning, as Heraclius reported to his officials “I was shown in a dream last night that the kingdom of the circumcision will be victorious,” according to the Islamic historian al-Tabari.19 Heraclius was soon brought to the conclusion, after speaking with a Bedouin, that an Arab Prophet would be at the center of this coming victory.

As it happened, Muhammad’s long-time enemy, Abu Sufyan, was in Jerusalem on business at this juncture. The Byzantine emperor Heraclius, learning that a prominent Arab of the Hijaz was available, brought Abu Sufyan in for questioning. The emperor Heraclius asked Abu Sufyan about Muhammad. The Quraysh chief took the opportunity to slander the Prophet, criticizing everything about Muhammad, from Muhammad’s lineage, to his conduct as a leader, to the community that Muhammad led in Medina. Abu Sufyan’s slander of the Prophet, however, backfired. The historian al-Tabari, at work very roughly around 900, wrote that the Byzantine emperor Heraclius, in the year 629, after hearing all of this defamation, said the following:

I asked you [, Abu Sufyan], whether [Muhammad] had any authority among you, of which you stripped him, so that he brought this discourse, seeking thereby to regain his authority; and you said no. I asked you about his followers, and you stated that they were the weak, poor, juveniles, and women; but such have been the followers of the prophets in every age. I asked you about those who follow him, whether they love him and adhere to him or fall out with him and abandon him, and you stated that no man follows him and then abandons him; but such is the sweetness of faith. It does not enter the heart and then depart from it. I asked you whether he acts treacherously, and you said no. And so, if you have told me the truth about him, he shall surely wrest from me this very ground under my feet. Would that I were with him that I might wash his feet! Depart to your business!20

The scene is almost Shakespearean in its turnabout, though of course it’s quite hard to believe that the Byzantine emperor Heraclius, at the top of his game, would preemptively genuflect to a thus far middleweight regional leader. There’s more in the historian al-Tabari on the subject – Heraclius, according to tradition, received a letter from Muhammad and became convinced that Muhammad was the legitimate prophet of God, and that though Heraclius started to tell his administration just this, the Byzantine Emperor decided to keep the news to himself.21 These are well told stories in later works of Islamic history, and maybe they’re true, but they also sound an awful lot like the hagiographic legends of a devout community.

To turn back a little more closely to history proper, while Muhammad’s attention had been focused on faraway Syria, something more immediately pressing occurred close to home. The Muslims and the Quraysh were still under the terms of a peace treaty. But then, one of the Meccan Quraysh clans raided one of the Medinan Muslim clans. A Muslim was killed. Muhammad’s old rival, Abu Sufyan, had just returned to Mecca from his business trip up to Jerusalem, and Abu Sufyan hurried up to Medina to do some damage control on behalf of the Quraysh, and smooth over the breaking of the treaty. The Meccans did not want war with the Muslims. The Meccans wanted the truce to hold. Abu Sufyan, upon arriving in Medina, found Muhammad taciturn and standoffish. Muhammad was married to Abu Sufyan’s daughter, Umm Habiba, but she was similarly cold in her reception, calling her father an idolator. Abu Sufyan went to speak with other acquaintances in Medina, but to no avail. Muhammad seemed to have made his mind up about something. That something was, finally, a Muslim attack on Mecca. [music]

The Muslim Conquest of Mecca

The truce between the Muslims and Meccan leadership, as far as Muhammad was concerned, had been broken. The Prophet contacted allies. The original emigrants who had come to Medina were joined by thousands of Medinan converts. Allied Bedouin tribes, too, joined the attack force departing from Medina, and another tribe joined the southward march. Only Muhammad knew the exact strategy that would be used. The Muslims positioned themselves ambiguously, staged to attack Mecca, or possibly the nearby city of Ta’if, an important pagan worship site.The Meccans watched the vast Muslim force encamped outside their city, and when Muhammad had campfires lit, his already sizable attack force looked even larger than it was. The Quraysh hoped that Ta’if was the target of the Medinan army. But they also knew that Muhammad considered their peace treaty broken. Thus, trying to mitigate an attack for which they were unprepared, the Quraysh sent emissaries to speak with Muhammad – leading Quraysh men who had dealt fairly with him in the past. Among them was, once again, Abu Sufyan, the Prophet’s onetime nemesis, with whom the Muhammad had just met up in Medina. The future caliph Umar proposed cutting off Abu Sufyan’s head straightaway, but Muhammad said he wouldn’t do this. Instead, Muhammad and his nemesis Abu Sufyan spoke.

The Quraysh plot against Muhammad in a miniature from the late 16th century (note Iblis / Satan in the background). While some Quraysh hardliners perished in conflict with the Muslims in the 620s, after the conquest of 630, most converted, including Muhammad’s longtime opponent Abu Sufyan.

The next morning the Prophet had his army’s tents loaded, and the military standards unfurled, and the Muslim fighting force marched right past Abu Sufyan. Abu Sufyan saw many former acquaintances passing by among the Muslims, and when one recent convert said that God was great, the entire army roared the same in affirmation. Among the Muslims were numerous troops from far off tribes – tribes beyond the Quraysh’s sphere of operations, and tribes that had formerly been Muhammad’s enemies. In the rear guard were Muhammad and the Medinans closest to him, heavily armored and ready to fight – so much so that the Prophet had to take the Muslim battle standard from one chief and give it to another, because the first chief was too eager to fall immediately into battle. Abu Sufyan, having just uttered the profession of faith for the first time himself, must have known that he was looking at the future as Muhammad’s army passed, because he ran back into Mecca and told the other Quraysh leaders that the game was up. There were ten thousand believers heading their way, armed to the teeth, war-hardened, and bent on taking the city.

Muhammad’s forces entered Mecca from multiple points at once, finding it undefended but for one idiosyncratic spurt of resistance. The Muslim fighting forces honored Muhammad’s promise. Meccans stayed in their homes, and they were left alone. Muhammad intervened in a tricky situation involving one of his cousins, counseling all present to keep the peace. Then, the Prophet went to the Kaaba. He went to the Black Stone, that cornerstone of the cube shaped shrine, and he touched it with his staff. He circled the House of God seven times. What happened next is especially famous. To quote the very early historian al-Waqidi again,

Around the Ka’ba were three hundred idols. Sixty idols were of lead. Hubal was the largest of them. It was facing the Ka’ba at its door. [Other statues of gods] stood at the place of slaughter and sacrifice of the sacrificial camels. Whenever the Prophet passed one of the idols he pointed at it with the staff in his hand saying, Truth came and throttled the false, indeed the false are destroyed, and the idol fell to the ground on its face.23

In this fashion, according to tradition, Muhammad destroyed the idols around the Kaaba. The Prophet then went to drink from the revered Zamzam well, which was the rightful prerogative of his own Hashimite clan. As for who would be the guardian of the Kaaba, Muhammad said that the Meccan clan that had traditionally guarded the Kaaba, the Banu ‘Abd ad-Dar, would continue to guard it, and he gave it to a member of this clan named Uthman ibn Talhah, who had recently converted to Islam. Then, Muhammad and a select group of followers went into the House of God.

The interior of the Kaaba at that time was decorated with many paintings of the region’s deities. Looking at all of them, Muhammad ordered most, or all of them erased. I say “most, or all” because in the historians al-Waqidi and ibn Ishaq there are stories about Muhammad preserving one or two paintings in the Kaaba. Muhammad, according to al-Waqidi, didn’t particularly like a painting of the patriarch Abraham that was in the Kaaba, but, seeing a painting of the Virgin Mary, Muhammad placed a hand on it and told his followers to erase all of the pictures except for the one of Abraham.24 According to ibn Ishaq, there were two pictures of Jesus and then Mary, and Muhammad ordered everything erased except for those two.25 Later Islamic scholarship has generally found the stories of Muhammad preserving certain paintings in the Kaaba to be dubious, and what exactly the Prophet did that day inside of the shrine has been debated for a long time.26 To me, all of the accounts make sense and seem in accordance with Qur’anic teachings. That Muhammad would erase all of the artwork in the Kaaba would be logical. That Muhammad would preserve images of Abraham, Jesus and Mary within the Kaaba, all of whom are spoken of respectfully in the Qur’an, would have also been logical.

Following the destruction of the idols around the Kaaba, Muhammad ordered all of the city’s household idols destroyed. And soon, Meccans were coming to him in great numbers to convert. Among those who professed faith was Hind, the wife of Abu Sufyan who had some years ago mutilated Muhammad’s uncle on the battlefield. Muhammad welcomed her, and many others into the new religion. Holdouts remained in their houses even as the city by and large went all in for Muhammad, but as time passed, more and more converted to the religion, and the conquest didn’t feel like so much of a conquest after all. [music]

The Muslims Fight the Hawazin Confederation

As peaceful as the Muslim conquest of Mecca had ultimately been, it still sent shockwaves through the region. Mecca wasn’t some small settlement, but a large trading town, famous throughout the Peninsula. Its conquest signaled the rise of a serious new power player in the region. And in addition to conquering Mecca, Muhammad had sent out smaller forces to destroy a local temple to the goddess al-‘Uzza. A major tribal confederation banded together to oppose the Muslims, led by a tribe called the Hawazin. The Hawazin military commander had ordered something unusual – the families, and the livestock of the Hawazin army would all be mustered along with their warriors, in order to compel troops to fight harder. What happened next is known as the Battle of Hunayn.When the Muslim army went to face the Hawazin confederation, the Hawazins attacked first, and fiercely at that. The Muslims were driven back, and nearly routed straightaway. Muhammad could barely be heard over the noise of the fighting, but he managed to rally his troops. Then, after voicing a prayer, he flung a handful of pebbles at the opposing forces, and suddenly the tide of the battle turned. There is a Qur’anic revelation about the Battle of Hunayn, which is as follows:

God has helped you [believers] on many battlefields, even on the day of the Battle of Hunayn. You were well pleased with your large numbers, but they were of no use to you: the earth seemed to close in on you despite its spaciousness, and you turned tail and fled. Then God sent His calm down to His Messenger and the believers, and He sent down invisible forces. He punished the disbelievers – this is what the disbelievers deserve – but after this God turns in His mercy to whoever He will. God is most forgiving and merciful. (9:25-7)27

Whatever exactly happened in the year 630 on the battlefield, the Muslims beat the tribal confederation that had amassed to attack them. Because the enemy Hawazin troops had brought their families and livestock, the Muslims were able to seize slaves and property, and a number of enemy troops sought shelter in the nearby fort of Ta’if. The Muslim army laid siege to this city, but, finding it well-defended, decided to concentrate their energies elsewhere.

In the aftermath of all this fighting, Muhammad had a reunion with someone he’d known a very, very long time ago. The Prophet, now about sixty, hadn’t seen his foster sister Shayma for half a century. He had known her ages ago, when he’d been under the care of a Bedouin wet nurse. Although she was seventy, now, she showed him a scar from where he’d bitten her when he was a baby. Muhammad invited Shayma to join Islam, and she said indeed she would, but that she would prefer to continue to live with her own tribe. Muhammad said that of course this would all be fine.

The spoils from the recent battle were, once inventoried, considerable. There were tens of thousands of camels, and even more sheep and goats, not to mention six thousand women and children. Muhammad himself was to receive a fifth of the spoils, according to Qur’anic revelation. He used his newfound property strategically, giving camels by the hundreds to important Meccans, some of them recent converts, and some on the verge of conversion, likely to show them that partnership with the new Muslim state system would not be without economic advantages, such as they were accustomed to as Quraysh leaders. This largesse worked, bringing several important Meccan men into the Muslim fold, including Muhammad’s longtime enemy Suhayl ibn Amr.

Muhammad’s gift giving after the Battle of Hunayn thus endeared some important power players from Mecca to him. But soon, there arose problems. The other four fifths of the spoils from the battle – the spoils that Muhammad had not taken – were supposed to go to the troops. These spoils included thousands of slaves. As it turned out, though, when Hawazin enemy commanders came to parley with Muhammad, they offered their allegiance in exchange for their wives and children back. Muhammad was willing, but the exchange meant that his own soldiers would receive far less wealth for their efforts in the battle. These soldiers, after the Hawazin slaves went back to their families, confronted Muhammad. What was the deal? The Muslim troops asked, many of them Medinan converts who had been at his side for a long time. Muhammad was giving Quraysh noblemen hundreds of camels, while they – the Muslims who had literally been in the trenches with him at Medina, were only being given a tiny part of the spoils – a few camels and sheep and goats. Muhammad asked his soldiers, in the historian ibn Ishaq, “Are you disturbed in mind because of the good things of this life by which I win over a people that they may become Muslims while I entrust you to your Islam?”28 It’s not a bad comeback, all things considered, this statement that Muhammad’s bottom line was spreading Islam, rather than enriching anyone, and it seemed to diffuse the situation with his troops.

The Prophet returned to Mecca not long after these military engagements. Then, he made his way up to Medina. In Medina, Muhammad doted on the baby boy to whom his Christian concubine Mariyah had given birth. For six months, the Prophet stayed in and around Medina, delegating small military expeditions to his most capable companions.

Further Islamic Territorial Expansion in 630

The road leading into Ta’if. The smaller neighbor of Mecca, in 630, still held out against Islamic conquest.

The Muslim army, when it reached the town of Tabuk, near the Gulf of Aqaba, found that the rumors of a Byzantine army marching on them were untrue. Still, the believers camped their force in the area for twenty days, making a peace treaty with some local Christians and Jews who lived up on the Gulf, and then, they turned their camels and horses back to Medina, having fought no major battle with the Romans, after all.

Following the saber rattling at Tabuk, Muhammad returned to find that his daughter Umm Kulthum had passed away. After mourning the loss of his daughter, Muhammad had to turn his attention again to matters of state. The city of Ta’if, a pagan stronghold thirty miles southeast of Mecca, had managed to withstand Muslim assaults early in the year 630, and the city wanted to negotiate. Ta’if was home to a sacred shrine of the Arabian goddess al-Lat. The city’s envoys knew that Muhammad wanted all of al-Lat’s idols destroyed and they asked if they might have a stay of execution for three years. The Prophet was ultimately unyielding, only compromising insofar as telling them that they didn’t have to destroy their own idols – his people would do it.

While Muhammad was stern about the pagan worship sites of Ta’if, in dealing with delegates from other tribes, tribes from as far off as Yemen, he was a bit more flexible. Some sheikhs from the south had already met Muslims, understood the new religion, and found its message appealing. The southern territories of the Arabian Peninsula, just like the Hijaz, had commingled tribal populations of Christians, Jews, and polytheists, and as these groups gradually embraced Islam, Muhammad sent messengers there to collect taxes. The general obligations of converted territories, according to an important passage in the historian ibn Ishaq, were that they:

Do well and obey God and His apostle and perform prayer, and pay alms, and God’s fifth of booty and the apostle’s share and selected part, and the poor tax which is incumbent on believers from land, namely a [tenth] of that watered by fountains and rain; of that watered by bucket a twentieth; for every forty camels a milch camel; for every thirty camels a young male camel; for every five camels a sheep; for every ten camels two sheep; for every forty cows one cow; for every thirty cows a bull calf or a cow calf; for every forty sheep at pasture one sheep. This is what God has laid upon the believers. . .If a Jew or Christian becomes a Muslim he is a believer with a believer’s rights and obligations. . .[If a Jew or Christian] holds fast to his religion. . .He must pay the poll tax – for every adult, male or female, free or slave, one full dinar. . .or its equivalent in clothes. He who pays that to God’s apostle has the guarantee of God and His apostle, and he who withholds it is the enemy of God and His apostle.29

These, then, were the general obligations of areas of the Peninsula that joined Muhammad – a fifth of any booty from raids, a poor tax from agriculture, and a modest share of livestock in exchange for security guarantees with the Medinan state. Jews and Christians had an additional tax to pay. This basic financial structure – Muslims paid alms and annual goods, and Christians and Jews paid alms and annual goods plus a poll tax – this structure would survive Muhammad, and be the financial engine of the Caliphates for a long time to come. It’s easy to see that those who joined the rapidly expanding monotheist coalition in the Hijaz would have had some advantages for doing so, not the least of which were stability and preempting a Muslim conquest on down the road.

Muhammad, at some point, had a revelation relevant to these financial laws. The Arabian Peninsula was a sprawling and diverse place, and Muhammad understood that many who declared their faith in Islam were secretly on the fence, or altogether faking it, and this revelation seemed to explain and justify the Arabian Peninsula’s size and heterodoxy in 630 CE or so. The Qur’anic revelation was, “We have assigned a law and a path to each of you. If God had so willed, He would have made you one community, but He wanted to test you through that which He has given you, so race to do good; you will all return to God and He will make clear to you the matters you differed about” (5:48).30 It’s a rich verse in the Qur’an, acknowledging the world’s religious diversity and emphasizing that this diversity was part of God’s plan, and further, that the disputes that believers have about God will be clarified in the afterlife. Perhaps it’s the revelation of an older person, and one who sees that the world tends toward a state of religious disorder in spite of a great many efforts to the contrary.

Yet Muhammad also had another revelation around this time, this one not so resigned about the old pagan traditions of the Hijaz. It was the time for the annual pilgrimage, and the Prophet wanted polytheistic rites around the Kaaba and its environs prohibited. A Qur’anic revelation came to him that says, “Believers, those who ascribe partners to God are truly unclean: do not let them come near the Sacred Mosque after this year” (9:21).31 In other words, that year’s pilgrimage would be the last pilgrimage of the old sort, and after that year, only Muslims would be permitted near Mecca’s Kaaba. The future caliphs Abu Bakr and Ali went down to Mecca that year to superintend the final heterodox pilgrimage. Muhammad remained in Medina. [music]

The First Exclusively Muslim Pilgrimage

The city of Yathrib, or Medina, had been the Prophet’s home now for nine years, and as he entered his tenth there, he was hit with another loss in his family. Little Ibrahim, the Prophet’s baby son with his concubine Mariyah, passed away in Muhammad’s presence. The loss must have stung the Prophet keenly, as he was Muhammad’s third son to die. But all the same, 631 and 632 were incredibly successful years for the Prophet’s community. So many delegations were coming in from the Peninsula’s tribes that some of Muhammad’s followers proposed simply hanging up their arms and armor. Islam was now catching on organically by its own merits, and between the ideology’s intrinsic appeal and the advantages of joining the expanding coalition based in the Hijaz, many populations on the Arabian Peninsula were becoming involved with Islam and the Medinan state to various extents.There are many hadiths from the final year or two of the Prophet’s life – hadiths that discuss what he foretold about the future of Islam. These hadiths record what Muhammad said to Ali and the other future caliphs, and to his immediate family, regarding how highly he regarded them.32 Hadiths dated to the end of Muhammad’s life record his speculations about Islam’s future, and his sense that Muslims wouldn’t always follow the right path, including the bleak sounding prediction that “Islam began as a stranger and will become once more as a stranger.”33 The hadiths about Muhammad’s later prophecies also include the hadith scholar Abu Dawud’s report that Muhammad foresaw the coming of a messianic figure called the Mahdi – a figure who would arrive in later days, at a time of evil and moral turpitude. Abu Dawud, at work during the late ninth century, wrote that Muhammad prophesied that “The Mahdi is of me. He has a high forehead and a prominent nose. He will fill the world with fairness and justice as it was filled with wrongdoing and injustice, and he will rule for seven years.”34 Other eschatological prophecies are recorded in other hadith collections, and these oracles ended up being extremely important in later Islamic history, but that’s a story for a later episode.

These prophecies of a coming judgment day are some of the last tales that Islamic biographers set down about Muhammad’s life. The Prophet, according to another hadith, suspected that his time was drawing to a close when something unusual happened to him at the mosque at Medina. Muhammad told his daughter Fatima, in the hadiths of al-Bukhari, that every year, the angel Gabriel would come to him and recite the entire Qur’an to him to make sure that the Prophet had it memorized. This year, however, Gabriel had recited it twice, which led Muhammad to suspect that he wouldn’t be around much longer.35

In late 631, it was the time for the annual pilgrimage to Mecca. This was a special pilgrimage, because it was the first time that only Muslims would visit the city and its sacred shrine. The textual records of this pilgrimage are also important, because they have been central in establishing how the hajj was to be carried out, both in antiquity as well as today. Thirty thousand believers set out from Medina, led by the Prophet himself, who made the customary rounds of the Kaaba and prayers in its vicinity. He did not spend the night in Mecca, though, which had been the tradition while the Quraysh controlled the city. Instead, Muhammad went to a rocky hill about 11 miles southeast of the Kaaba – a hill known in Islamic history as Mount Arafat, and the other pilgrims followed him. The Prophet announced that henceforth, a stop at Mount Arafat would be a part of the pilgrimage to Mecca. And standing atop the rocky mound, Muhammad delivered what is often called the Farewell Sermon.

Mount Arafat during the hajj. Note the pilgrims covering the promontory’s slopes! Muhammad’s farewell sermon of 631 took place atop this mountain. Photo by Amalia.

Not all of Muhammad’s followers were in Mecca for this pilgrimage. Ali had been down in Yemen on matters of state, and when the future caliph headed back up north to perform pilgrimage rites, he was leading hundreds of cavalrymen. These cavalrymen had in their possession a great deal of fresh linen they had accepted as spoils from a recent campaign. Ali had ordered them to save it for the Prophet, but, approaching Mecca as they were, and wanting to be clad appropriately for the pilgrimage, they had dressed themselves in the linens. Ali told the cavalrymen to take it off, and they did, though with plenty of grumbling. Later, it was with some difficulty that Muhammad mollified the cavalrymen’s ire toward Ali, telling them that a friend of Ali was a friend of his, and a foe of Ali was a foe of Muhammad’s, and this proclamation silenced them. This speech, by the way, sometimes called the Sermon of Ghadir Khumm, and what Muhammad said and meant there in regards to Ali, is one of the central points of contention between Sunnis and Shiites today, and we’ll come back to it in a later episode.

When Muhammad returned to Medina, his attention was required for several pressing matters of state. A number of other prophets had declared themselves as messengers of God. From the eastern peninsula, a man named Musaylimah had arisen from a Christian tribe and deemed himself a figurehead tantamount to Muhammad. Two other tribal chiefs also claimed that they had had revelations, as well as a woman named Sajah. Though their ministries were heretical to Muhammad, and he made this known, he did not act against any of them right away. Instead, he focused his attention on the Ghassanid and Byzantine north, directing a campaign there to be led by the Usama, the son of his adopted son, Zayd.

Muhammad’s Decline and Passing

As the spring of 632 continued, Muhammad, though he looked hale and bright eyed, came down with a fever, and a headache. He led prayers in the mosque, one day emphasizing his special love for his old friend Abu Bakr, telling the congregation that “if I were to take from all mankind an inseparable friend he would be Abu Bakr – but companionship and brotherhood of faith is ours until God unite us in His Presence.”38 Tired after his sermon, and suffering from a headache, he went to the house of his wife Maymunah. There, he heard that young Aisha was also suffering from a headache, and the two commiserated, with Muhammad’s remarks tending toward the morbid. As the days went by, Muhammad could no longer stand to lead prayer, and so he sat in the mosque to do so, telling his congregation to do the same. Afterward, it became clear to all of his wives that he wanted to spend time with Aisha, though he was not appointed to stay with her until some days later, and the allotted wives ceded their days to Aisha.Soon, Muhammad couldn’t walk unaided, and so his family helped him. Some criticism had come in for his choice of the expedition leader. Critics were saying that Usama was way too young. Muhammad wanted to defend his choice, but he had developed a fever, and wasn’t getting any better. He had water poured on him, and then a cool cloth placed on his head, and when he went to the mosque after the call to prayer to lead the congregation, he told them that Usama would be a worthy commander, and that naysayers shouldn’t doubt the man on account of his youth. Then Muhammad went back to Aisha’s quarters to rest, announcing that Abu Bakr was to lead the congregation in his absence.

Time passed, and Muhammad’s illness grew worse. Aisha kept him close, and other wives helped care for him. It was early June of 632, according to tradition, June the 8th. Muhammad’s fever slackened, and he was able to go to the mosque after the morning call to prayer. Abu Bakr heard the Prophet coming, and prepared to cede his place to Muhammad, but Muhammad told his old friend to keep leading the congregation, and he took a seat to Abu Bakr’s right. The Medinans were heartened to see Muhammad up and about, and everyone was asking hopefully after Muhammad’s health.

But the Prophet was faring poorly again. He returned to Aisha’s apartment, and he rested his head on her lap. He lost consciousness for a while, alternately showing signs of consciousness and vitality. On one occasion, Muhammad saw someone enter with an implement called a siwak, essentially a natural toothbrush, and, though the Prophet couldn’t speak, he signaled that he wanted the toothbrush. Aisha, in the pages of historian ibn Sa’d, is recorded as saying, “The Apostle of Allah, may Allah bless him, looked at his hand in a way that I knew he wanted it. So I said: O Apostle of Allah! do you wish that I should give you this [siwak]? He said: Yes. So I took it, chewed it till I softened it, then I gave it to him. He cleansed his teeth much more than he used to do before.”39 This is a moment of piercing tragedy in the ancient biographer ibn Sa’d – this scene in which one of history’s most important people, dying, suddenly wants to clean his teeth, and his family does all they can to accommodate him, in his pain, and confusion, and resilience. It’s such a strange, specific story, with no ring of hagiography or theological polemic that, like so many other curious minor junctures of Muhammad’s life, it’s easy to believe that it actually happened, just as ibn Sa’d described it.

The same historian – ibn Sa’d – describes the Prophet’s final moments as spiritual ones. The historian records how Muhammad, in the agony of his illness, spoke with the angel Gabriel, who introduced the Prophet to the angel of death. Gabriel told Muhammad that the angel of death “never sought permission from any human being before you and he will never seek permission from any one after you.”40 The angel of death, then, told Muhammad that the Prophet could command him to leave Muhammad’s soul in his body, or take it out. Gabriel told Muhammad that God was eager to see him, and so Muhammad, with this consolation, gave his permission, and after an earth-shaking 61 or 62 years on this planet, he passed away in the arms of his wife.

There are many deathbed stories about Muhammad in the biographies and hadiths. They recall things that he said, directives that he issued, events that he predicted, and pronouncements that he made on this or that family member. What he decreed at the end of his life was, of course, important to posterity, both in the immediate aftermath of his death in June of 632, and in all of recorded history since. The stories range from the secular and mundane, as we heard in the story of the toothbrush, to the hagiographic, as we heard in the tale of Muhammad negotiating with the angel of death. And while different sects of Islam have emphasized different accounts of his passing, they all agree on something very important. Muhammad died surrounded by friends and family who loved and revered him deeply – who knew him as a person, as well as a Prophet. [music]

Abu Bakr, Ali, and the Beginning of the Rashidun Caliphate in 632

Following Muhammad’s death, the expedition northward to Syria was halted. The future Caliph Umar, outside of the Prophet’s Mosque, told a crowd that Muhammad was only gone for a little while – his spirit would surely return. Abu Bakr went to see his daughter Aisha. Abu Bakr drew back the cloak that had been used to cover Muhammad, and gazed sadly on his departed friend, telling the Prophet that though Muhammad had died, he would never die again. Then, Abu Bakr went to where Umar had been speaking, and he took over. Abu Bakr told the throng that they had heard correctly. Muhammad was gone. But then, Abu Bakr quoted a very appropriate passage from the Qur’an. The Qur’an says, “Muhammad is only a messenger before whom many messengers have been and gone. If he died or was killed, would you revert to your old ways? If anyone did so, he would not harm God in the least. God will reward the grateful” (3.144).41 It was just the right thing to say. The crowd quoted the verse, and quoted it again, and passed it on. And Abu Bakr, according to a famous hadith, said something else that was perfect for the moment. He said, “[W]hoever amongst you worshipped Muhammad, then Muhammad is dead, but whoever worshipped Allah, Allah is alive and will never die.”42 This remark, along with the Qur’anic verse Abu Bakr had quoted, was just what the distraught believers needed to hear.

The map displays Islamic conquests that took place in 632 – conquests fought against self-styled prophets whom the new Muslim state declared heretics. Note the relatively small size of the Rashidun caliphate in 632, right after Muhammad’s death. (It wouldn’t be small for very much longer!) Map by Mohammad Adil.

Almost all of the native Medinans were convinced. At dawn, the next day, Abu Bakr stood up at the front of the mosque, while Umar spoke up on his behalf. Umar told the congregation that Abu Bakr had always been by Muhammad’s side, through thick and thin, even at that terrifying moment back in the summer of 622 when Muhammad and Abu Bakr had hidden in a cave while Meccan patrols had searched for them. Wouldn’t those in the congregation pledge their allegiance to Abu Bakr as the Khalifat Rasul Allah, with Khalifat, or Caliph, meaning “deputy,” or “successor?” The audience said that they would, with everyone there pledging allegiance to Abu Bakr, save one person. According to the hadith scholar al-Bukhari, Muhammad’s son-in-law Ali was reluctant to swear allegiance to Abu Bakr right away. In terms of propinquity, after all, Ali had as good a claim to being a successor as Abu Bakr did. Ali was Muhammad’s longtime companion, and son-in-law; the husband of Muhammad’s beloved daughter Fatima, and the father of Muhammad’s grandchildren, Umm Kulthum, Zaynab, Hassan, and Hussain. However, again according to the hadith chronicler al-Bukhari, Ali eventually, some months later, confronted Abu Bakr about the succession, emphasizing that he (meaning Ali) had been blindsided by Abu Bakr’s sudden promotion after Muhammad’s death. Abu Bakr, rather than revealing insecurity or anger, wept and he told Ali he loathed the idea of any disunity among Muhammad’s interior circle. Soon after this, Abu Bakr and Ali reconciled in the Prophet’s Mosque.43 Abu Bakr was about sixty years old, and Ali, a generation younger, about thirty.

This story of how Abu Bakr became first caliph, rather than Ali, a story which I’ve just told very quickly, is at the center of the Sunni and Shia split. In case you’ve never heard this division explained, let me lay it out for you. Around 85-90% of Muslims today are Sunnis, and 10-15% are Shias. Their basic theological difference is as follows. Sunnis, while they revere Ali, believe that Abu Bakr was the rightful first caliph, and moreover, that although Muhammad’s biological descendants deserve suitable respect, Islamic leadership belongs to whoever is pious and educated enough to merit it. Shias, on the other hand, believe that Ali should have been made caliph in 632, that Islamic leadership should be, and should always have been, in the hands of the descendants of Ali, and that at some future point, the Mahdi, a descendant of Ali and savior figure, will come to earth and lead righteous Muslims to victory. Different sects of Shiism have different doctrines about judgment day. But all Shias, in contrast to Sunnis, believe that in 632 CE, Muhammad’s friend Abu Bakr should not have become caliph, and that Ali should have. 632 thus marked the birth of the Shi’at Ali, or “party of Ali,” or the Shiites, which, during Ali’s life, were simply those who believed in the young man and thought that he should rule. The Shi’at Ali, again just “supporters of Ali” initially, were first distressed when Abu Bakr became caliph in 632, and then Umar in 634, and then Uthman in 644, such that poor Ali waited 24 years before becoming a caliph himself in 656, thereafter having a tragically short and fraught period on the caliphal throne.

To turn back to the immediate aftermath of the Prophet’s death in June of 632, Muhammad’s family washed his body to prepare it for burial. There was some debate about where he should be buried, but in the end, it was decided that he’d be buried in the ground in Aisha’s chamber, right near where he’d passed away. Before the burial, many pious citizens who had known him passed by to offer their farewells, their prayers, and their love. Among the companions, the feeling of loss was immense. No one doubted that Muhammad had gone to a better place. At the same time, all believed that Muhammad had been in communication with heaven itself, and without him, things would never be the same. Still, they remembered his words, as captured in a hadith by the scholar ibn Majah: “What have I to do with this world? I and this world are as a rider and a tree beneath which he take[s] shelter. Then he go[es] on his way, and leave[s] it behind him.”44 And so Muhammad left the world, and his grave now lies beneath the Green Dome of the Prophet’s Mosque in Medina, where millions pay their respects every year to honor the person whose story you’ve just heard. [music]

Muhammad’s Life and Related Historiography: A Retrospective

So that was the story of the Prophet Muhammad, as best as I could tell it, with ibn Ishaq, al-Waqidi, ibn Sa’d, and al-Tabari, on one side of my desk, as many modern biographies on the other side, and some hadith compilations on a table behind me. It is a long, complicated story, and it should sound like one, at least for grown-ups.I wanted to tell you about Muhammad’s life at some length because, first of all, his was one of the most influential lives ever lived. But I also wanted to give you an idea of the vastness of Muhammad’s story – the millions of pages written about him – the oral traditions, then the early biographies and hadith collections, and everything set down after the ninth century, too. Muhammad’s biography is a saga with hundreds and hundreds of names – the names of the Prophet’s ancestors, his clan and tribe, the names of other clans and tribes, of towns and settlements, of chieftains and rulers, both far away and close at hand. Understanding his biography means understanding Late Antique Arabia. And learning about Muhammad’s life as it’s come down to us also requires understanding the later intellectual history of the early caliphates – the way that the oral traditions of the Rashidun and Umayyad caliphates evolved into the written traditions of the Abbasid caliphate, and what was lost and gained during this long evolution. Learning about him, as we’ve done over the past six hours, invites us to adjust our scope and polarity, to leave behind the ancient Mediterranean world where we’ve been rooted for so long, and to settle in somewhere else.

Arabia during Muhammad’s lifetime was a place unlike any other that we’ve encountered in our podcast. In some ways, the term al-Jahiliya applies to it. It was a porous place, where coalitions of tribes agglomerated and dissolved, where wars were frequent and noncommittal, and where commercial partnerships were subject to clan vendettas and family feuds – more like Merovingian France than the Roman Empire under, say, the Nerva-Antonine dynasty. But Muhammad’s Arabia was also a place that crackled with real and potential dynamism. Business was booming there. The Hijaz had been a center of commerce for a long time. As the 500s turned to the 600s, Byzantine and Sasanian client kingdoms were hiring more and more Arab auxiliaries, and sending money and commercial influences down into the outlying areas of the Peninsula at unprecedented rates. As the two ancient empires north of the Peninsula ravaged one another from 602-628, Muhammad would have sensed opportunity in the air, though the early biographies say little about this great war. The Prophet’s lifespan, even if he had never had a revelation, was still a time of transition for Arabia.

Arabia, to the early caliphates, was the world’s fulcrum. Historian Tamim Ansary wrote that during the early Medieval period,

To Muslims, everything between Byzantium and Andalusia was a more or less primeval forest inhabited by men so primitive they still ate pig flesh. . .[Muslims] knew that an advanced civilization had once flourished further west: a person could still make out traces of it in Italy and parts of the Mediterranean coast. . .but it had crumbled. . .before Islam entered the world, and was now little more than a memory.45

As the Romans had once done, Muslims regarded the world beyond the civilization and glitter of their empires to be a frosty waste, populated with fetid barbarians. To Abbasid Muslims, the heartland of Islam wasn’t middle, or east of anything. It was the junction between Europe, Asia, and Africa, just as it had been during the life of Muhammad. It was the place where all of the ideological momentum of the ancient world had collaborated to produce the final, and perfect, Prophet of God, and after him, a new and advanced civilization.

Muhammad should be a much more familiar figure to many of us than he is today. As a leader, he had something of the Roman emperor Augustus, whose motto was festina lente, or “make haste slowly.” Muhammad was patient, practical, resolute, perceptive, intelligent, and capable of working with whatever tools he had. In a tribal world where trust and personal expertise were more important than institutions and bureaucracies, Muhammad must have had incredible instincts for deciding whom to trust, and whom to hold at arms’ length; who was solid, and who was sketchy.

There are many different Muhammads, depending on which hadiths we read, depending on whether we read Classical Islamic biographies or orientalizing western ones; whether we hear dogmatic teachings about Muhammad growing up in Muslim countries, or similarly purblind teachings growing up elsewhere. In Islamic history, the doctrine of ‘Ismah is the notion of the moral infallibility of certain figures, foremost among them Muhammad – the notion that Muhammad was incapable of error. On the absolute opposite end of the spectrum, Dante Alighieri imagined Muhammad in the ninth circle of the bottom of hell, enduring the most graphic and gruesome punishment in the entire Inferno for being a schismatic, or sower of discord.46 Between the absolutely infallible on one hand, and the reprobate damned on the other, though, there was a person – a person who, in spite of the hagiographic miracle stories that stud the ninth century biographies – never himself alleged to be anything but a messenger.