Episode 32: Trees Bending to the Torrent

Sophocles’ Theban Plays, 3 of 3. Antigone is a timeless and dark story about a clash of wills. But it’s also fascinating snapshot of the philosophical brawls of 5th-century BCE Athens.

| Read Transcription | References and Notes |

| Episode Quiz | Episode Song |

| Episode on Spotify | Episode on Apple Podcasts |

| Previous Show | Next Show |

The Background of Sophocles’ Antigone

Hello, and welcome to Literature and History. Episode 32: Trees Bending to the Torrent. In this program, we’re going read Antigone, the third of Sophocles’ three Theban plays, likely produced during the spring of 441 BCE in the city of Athens. If you’re just jumping in and you want to hear the story from the beginning, you can learn about the first and second of the three Theban plays in Episodes 30 and 31. You should, however, be able to enjoy Antigone without knowing the other two plays, and I’ll also give you some background upfront so you’ll know exactly what’s going on from the very first scene onward.Antigone is one of a small handful of ancient Greek tragedies that still get staged relatively often, and that, in the English-speaking world, we sometimes read in high school and college literature courses. Its central motif of one strong-willed person who will not back down or compromise her beliefs has resonated with many generations, for many different reasons across the past two and a half thousand years. But even in 441 BCE, the story of Sophocles’ Antigone was not an original one.

Often, in literature, it takes many people, and many generations, to tell a single story. The events that took place at the city of Troy that inspired the Iliad and the Odyssey were one such occasion – these epic poems were crafted over long periods of time. The story of the Israelites in the Pentateuch and the Historical Books of the Tanakh is another example – the composition of these texts spanned hundreds of years and multiple phases of ancient near eastern history. But another example of a tale taking hundreds of years to be told was an Ancient Greek story that spanned several generations back during the age of heroes – a story that took place in the city of Thebes.

Today we’re going to return, once again, to Thebes, that ancient city located about thirty miles or fifty kilometers northwest of Athens on the Greek mainland. Many ancient Greek writers concerned themselves with two generations who lived at Thebes – the generation of the doomed King Oedipus, which we learned about in the previous two episodes, and then Oedipus’ children – the boys, Polynices and Eteocles, and then the girls, Ismene and Antigone. While there are different versions of Antigone’s story, by far the most famous is the one written by the Athenian dramatist Sophocles, and staged, again, probably in 441 BCE. And by the end of this show, you’re going to know that story well. [music]

The Three Theban Plays and the Civil War at Thebes

Before we delve into the play Antigone, let’s talk about the three Theban plays thus far – just their basic plot lines. In the first one, the King Oedipus discovered that he’d killed his father and married his mother, and, disgraced and broken, he gouged his eyes after his poor wife and mother Jocasta took her on life. In the second one, old, broken Oedipus travelled from Thebes to the outskirts of Athens, where, after feuding with his former brother-in-law and cursing his son, Oedipus died. Now, the play that we’re going to explore today is about Oedipus’ daughter Antigone – the play Antigone is about Oedipus’ daughter going back to the city of Thebes, and what happens to her there.

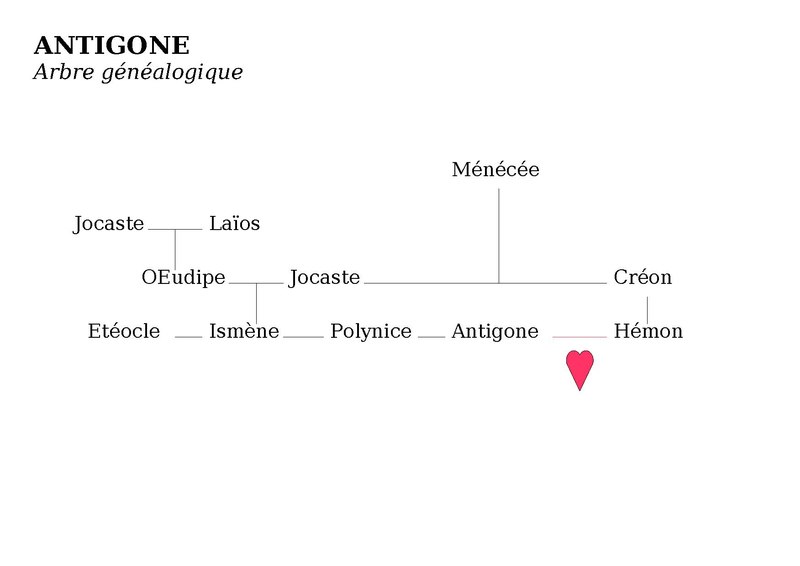

Antigone’s family tree. The bulk of the play is about the opposition between Antigone, her uncle Creon, and her beloved cousin Haemon, who tries to play the role of a mediator.

The epic war in question was fought by the sons of Oedipus, Polynices and Eteocles. Each son wanted to be king. They could not compromise. And so they fought. The war at Thebes is likely the second most famous war in ancient Greek literature, behind, of course the Trojan War. Although Sophocles didn’t – to our knowledge – write a play about the epic war at Thebes, his predecessor Aeschylus did. In fact, Aeschylus’ play Seven Against Thebes, staged in 467 BCE, was all about the epic war that had unfolded at Thebes. Aeschylus and Sophocles weren’t the only Athenian playwrights to deal with Thebes, and the family of Oedipus. Two decades after Antigone won Athens’ City Dionysia festival, in 423 BCE, Euripides’ play The Suppliants retold the story of the great war at Thebes, and fifteen years after that, in 408 BCE, Euripides’ The Phoenician Women retold the story of the war at Thebes yet again, this time focusing on Jocasta, who in Euripides’ version never commits suicide. The details of all of that are hard to remember, but the following is not. Decade after decade, during the height of Classical Athenian civilization, Athenians went to the theater to see plays about Oedipus and his children – tellings and retellings with variations, a patchwork quilt of productions about the same small group of events and people.

And that wasn’t the end of it, either. The Roman poet Statius, 500 years after Sophocles died, wrote an entire epic about the legendary war at Thebes – Statius finished his Thebaid around 92 CE, and when we get to later Latin literature, we’ll spend a couple of episodes on Statius’ epic, which, in my opinion, is fantastic and quite underrated. For now, though, it’s enough to understand that not only Greeks, but also Romans, for centuries and centuries, told stories about the fateful civil war at Thebes.

What I want to do is take the time period between Oedipus’ death, and Antigone’s arrival at Thebes, and fill in the gaps for you a bit, using a general mural made up of the plays of Aeschylus and Euripides, and the epic of the later Roman writer Statius. That way, when we get Sophocles’ Antigone in a couple of minutes, you will know exactly what’s happening, and why, in this most famous of ancient Greek tragedies.

We’ll need to begin by shifting our focus to Oedipus’ children. When Oedipus was disgraced – when his ugly secrets came to the surface, he abdicated his throne. He gave his throne to his two sons, Polynices and Eteocles. The plan was simple. After a period of stewardship by the dead queen’s brother, Creon, one of Oedipus’ sons would rule one year, and the other son would rule the next, and so on. Polynices was to be the first of the two sons on the throne, and having established the rules for his succession, Oedipus left town, heading down to Athens in the southeast, evidently confident that his boys would continue his fair-minded rule, and share the kingship between them.

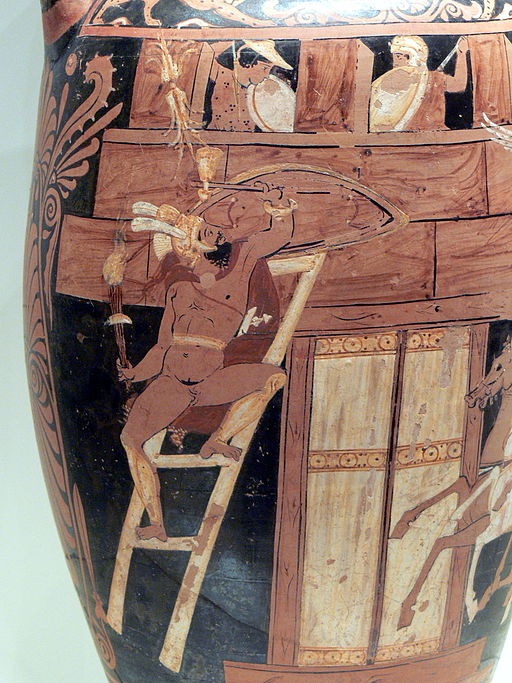

A Campanian red-figure amphora, dated to about 340 BCE, of a hero named Capaneus scaling the walls of Thebes during the legendary Theban war fought between Oedipus’ two sons. This is a major part of the Oedipus cycle not dealt with in Sophocles’ Oedipus plays. Photo by Xenophon.

So here’s a synopsis of the famous civil war that took place at Thebes. First, to repeat, one of Oedipus’ sons came to the throne – his older son, Polynices. And unfortunately, rather soon, Oedipus’ younger son, Eteocles stole the throne from his older brother in a violent coup. Polynices decided that rather than throwing up his hands for the general good of the population, he would go down to the city of Argos, round up an army, and make war on his hometown and his brother.

Around the time that Polynices was brainstorming this plan, he traveled down to Colonus, near Athens, where his father Oedipus was. There, Polynices asked old Oedipus for his blessing, in order to make war on their home city and kill his brother. As you likely remember from last time, in the play Oedipus at Colonus, Oedipus, distraught at the news that his two sons were feuding, told Polynices he hoped Polynices and his brother Eteocles would kill one another and both go to hell.

In spite of his dad’s curse, and his sister Antigone’s measured and rational counsel to do otherwise, Oedipus’ son Polynices went forward with his planned assault on the city of Thebes. He, and six other champions from the allied city of Argos marched on Thebes – this is where Aeschylus gets the title Seven Against Thebes. Seven champions of Argos marched up to the seven gates of Thebes and made war on seven Theban champions. Antiquity sure loved numerical symmetry. And at the climax of the Theban War, Polynices finally fought his brother Eteocles. And just as Oedipus had prayed, the brothers slaughtered one another. And that was the end of the epic war at Thebes. In the hands of Aeschylus, and as we’ll later see, Statius, it’s an enthralling and tragic war story – but for today’s purposes we just needed to get those events on the table. As the curtains of the play Antigone open, there has already been a war. One brother was defending the city, the other was assaulting the city, both were morally besmirched by their lust for power, and they have just killed each other. That’s the tragic, messy situation that titular character of Antigone is walking into at the outset of the play. If we were Athenians watching this play in 441 BCE, and the musicians were warming up down around the stage, we would know all of this ahead of time.

Now, before we start Antigone, let’s talk about some key characters. As Antigone begins, there are four characters about whom you need to know. The heroic, ill-fated Oedipus is gone. His similarly unlucky wife and mother Jocasta is dead. His belligerent sons have just finished taking each other out. So who’s there left to write a play about, anyway?

First, of course, there’s Antigone herself. If you remember from the second of the three Theban plays, Oedipus at Colonus, Antigone was the child who stayed with her dad, and the youngest daughter of Oedipus and Jocasta. Above all else, Antigone’s most distinguishing characteristic is likely her loyalty to family. But there’s more to her than this. Antigone also has a dark side. This dark side is a stubborn resolution not uncommon in Ancient Greek tragedy – an indisposition to compromise, regardless of the counsel of everyone around her. Now, surely you know stubborn people, and you’ve thought about stubbornness. And if you know stubborn people, you know that stubbornness is a strength as well as a shortcoming – it’s certainly admirable to stick to one’s guns, but at the same time adaptability and a willingness to negotiate are pretty useful character traits, too. Antigone’s most salient character trait, alongside her loyalty to her family, is a certain tragic relentlessness that is as laudable as it is dangerous. So that’s Antigone.

Creon (left) confronts Antigone (right). The Theban king’s descent into violent totalitarianism makes Antigone a character study about Creon just as much as it is about the titular character.

Antigone and her uncle Creon may have different ideological positions – Antigone for her family, and Creon, on the surface at least, for the state. But they both share a very memorable, and very dangerous quality. Both characters have an unbudging self-certainty – that stubborn resolution that can be a strength as well as a shortcoming. And because Creon, throughout the play, is in a position of power, his self-certainty is far more dangers Antigone’s. The core of the play Antigone is the showdown between these two equally unyielding characters.

So you know about willful, family-loving Antigone, and willful, state-loving Creon. Let’s meet the two other principal characters of the play. One of them is Antigone’s older sister, Ismene. Ismene is an appealing character. She is a survivor, and a pragmatist. Though she lacks the fierce willfulness and gravelly one-liners of her sister, Ismene has a perceptiveness and an adaptability that make her stand out among the many fierce individualists who populate Sophocles’ Theban plays. Ismene isn’t as famous as her three siblings, but if all the kids had been like Ismene, there would have been no war at Thebes, no brothers killing brothers, and history might have continued on reasonably smoothly after Oedipus’ tragic secrets were uncovered. So that’s Ismene, the older sister.

So we’ve met Antigone, her uncle Creon, and her older sister Ismene. There’s just one more person you should meet before we begin this play, and that’s Creon’s son, Haemon. Haemon’s name, by the way, is transliterated H-A-E-M-O-N into English, and to be perhaps overbearingly clear, his name has nothing to do with the body part that has a similarly sounding name. So, when we get to Haemon, we come to a bit of a hiccup in the plots of the three Theban plays of Sophocles. Haemon doesn’t come up in Oedipus the King, nor does he appear in Oedipus at Colonus. Basically, Haemon just kind of shows up out of thin air in Antigone. Haemon is Antigone’s fiancé. And he’s a good person. Haemon, again Antigone’s fiancé and Creon’s son, finds himself between a rock and a hard place when trying to negotiate with his willful fiancé Antigone and his equally unbending father Creon. As old king Creon becomes increasingly entrenched and dogmatic, Haemon works, heroically and articulately, to try and reason with him.

So to review, there are two unyielding characters – Antigone and her uncle Creon. And there are two flexible realists – Antigone’s older sister Ismene, and her smart and diplomatic fiancé Haemon. The core of the play’s plot is that Creon and Antigone are going to go obstinately, uncompromisingly head-to-head with each other, and that Ismene and Haemon are intermittently going to try and get the uncle and niece to be more reasonable

So now you know the situation and main characters of Sophocles’ famous and frequently staged play, Antigone. As before, unless otherwise noted, I’m quoting from time to time from the E.F. Watling translation, published by Penguin Books in 1974. [music]

The Opening Scene: Antigone and Ismene

The play Antigone, like Oedipus the King, takes place on the steps of the palace at Thebes. If you had been in Athens at the City Dionysia in the spring of 441 BCE when Antigone premiered, that’s what you would have seen. The grand doors of the palace at Thebes stood imposingly over these steps. In this same place, at the threshold of the Theban palace, once, citizens had complained to king Oedipus that they were dying of the plague. On these steps, Oedipus had sought, against all counsel, the answer to the dark mystery of his birth. And on these same steps, and from these same doors, Oedipus had emerged and bemoaned his fate with bloody eye sockets after seeing the hanged body of his wife and mother Jocasta. The play Antigone, which takes place some years after these events, is set in this same fateful location, and the story’s crisis emerges almost immediately.Ismene and her younger sister Antigone came out through the palace doors, and Antigone turned to her sister. Antigone told Ismene, “There is no pain, no sorrow, no suffering, no dishonor / We have not shared together, you and I. / And now there is something more. Have you heard this order, / This latest order that the king has proclaimed to the city?”1

Who was this king whom Antigone described? Hadn’t the male line of Oedipus been extinguished? Hadn’t Eteocles and Polynices killed one another, and Polynices’ allies from Argos withdrawn from Theban territory? The king whom Antigone mentions in this early line of the play was their uncle Creon. Creon had seen the cursed line of Oedipus embroil the city of Thebes with a plague, and then nearly destroy the city with war. And so Creon had taken power for himself.

Tense and distraught, Antigone looked at her sister. Creon had done something awful, Antigone said. Their brother Eteocles had died defending the city whose throne he refused to share with his brother Polynices. And Eteocles had been given a fine funeral and honored burial. But Polynices, who’d attacked the city in an effort to take regency from his brother – Polynices would have no burial. King Creon intended that Polynices be eaten by carrion birds. If anyone tried to bury Polynices, Creon had proclaimed, it would be deemed an act of disobedience to the state. Antigone added that anyone who tried to bury Polynices would be stoned to death. Antigone told Ismene, “So now you know. And now is the time to show / Whether or not you are worthy of your high blood” (127). What did Antigone mean when she told her sister Ismene that it was time for Ismene to prove her worth? Antigone wanted her sister to help her defy the new king Creon’s orders by securing Polynices’ body and giving it a proper burial.

Ismene was hesitant to agree with her sister’s oath. Their parents had died, Ismene said. Their brothers had died. Now, it was just the two of them left. They were women, Ismene told Antigone, and their power against the state was minute. It would be a dreadful folly to rebel against Creon, and the power that he represented in Thebes.

Antigone did not berate her sister for these words. Antigone, nonetheless, said that she intended to bury her brother. Her only crime would be reverence, and besides – life was short, and the eternity that one spent with the dead was what really counted. The sisters then shared a famous series of remarks. Here they are, in the Penguin Robert Fagles translation this time:

ISMENE:

Oh Antigone, you’re so rash – I’m so afraid for you!

ANTIGONE:

Don’t fear for me. Set your own life in order.

ISMENE:

Then don’t, at least, blurt this out to anyone.

Keep it a secret. I’ll join you in that, I promise.

ANTIGONE:

Dear god, shout it from the rooftops. I’ll hate you

all the more for silence – tell the world!

ISMENE:

So fiery – and it ought to chill your heart.

ANTIGONE:

I know I please where I must please the most.

ISMENE:

Yes, if you can, but you’re in love with impossibility.

ANTIGONE:

Very well then, once my strength gives out

I will be done at last.

ISMENE:

You’re wrong from the start,

you’re off on a hopeless quest.

ANTIGONE:

If you say so, you will make me hate you,

and the hatred of the dead, by all rights,

will haunt you night and day.

But leave me to my own absurdity, leave me

to suffer this – dreadful thing. I will suffer

nothing as [terrible] as death without glory.2

Following this exchange, Ismene went back into the palace, and Antigone hurried off to begin her perilous errand. [music]

Creon’s Opening Appearance and Speech

With the daughters of Oedipus offstage, a chorus of Theban elders – who will be a frequent presence for the remainder of the play – a chorus of Theban elders climbed up the palace steps. The perspective of the chorus was different from that of either sister – they were the voice of the median citizen of Thebes. The old men of the chorus praised the dawn – the bright golden sunlight that had come up over the river, almost as though the sun itself were responsible for chasing off the invading army of Polynices. The old men of the chorus had been terrified at the sight of Polynices and his thousands of men, and they briefly recollected the events of the war. Above all else, they thanked the gods that the war was over, and announced the coming of Creon.King Creon looked familiarly at the elders of Thebes. He said he’d called them together because he knew that they’d always been loyal subjects to Oedipus, and Creon made a lengthy speech in which he explained his ruling philosophy and his decisions about the feuding brothers Eteocles and Polynices.

Creon proclaimed that he’d come to the throne because he was next of kin. He realized, Creon said, that being a ruler was the greatest test of a person – a test that would bring out his mettle and true colors like nothing else would. Perhaps because he knew the difficulty of his new position of sovereign, Creon said that any king who did not seek advice was damned to failure. Having established all this, Creon told the Theban elders of the political philosophy that would inform his reign.

The state, Creon said, came before everyone. It came before friends, and friendships could not exist without the auspices of the state. Creon went so far as to emphasize that the state was life itself. Having said this, Creon explained his decision about the recently deceased sons of King Oedipus. Eteocles, Creon said, had died defending his city. Oedipus’ younger son would enjoy the graces of a state burial and funeral. But Oedipus’ older son, Polynices, who had led an army against his home city – Creon said – Polynices would not be buried, and dogs and birds would eat his remains. Creon said that whether men were dead or alive, their rewards, and their punishments, would be dictated by the state.

A further exchange between Creon and the elders of Thebes revealed that Creon had established a guard over the dead body of Polynices. Anyone who tried to lay it to rest – anyone who allowed it to be moved, would be sentenced to death. [music]

Antigone’s Disobedience: The Crisis Unfolds

Just then, a sentry rushed in. After catching his breath – and with great hesitancy, the sentry delivered his news to Creon. Somehow, the sentry said, someone had reached the dead body of the traitor Polynices, and buried it, scattering dust over it, and thus giving it the rites of a sanctified burial.Creon demanded to know more. The sentry said he and the other guards were perplexed. There had been no signs of the culprit – no signs of digging, nor wheel ruts, nor tracks. The men who had been guarding Polynices’ body were terrified – they accused one another, drew lots as to who would tell the king, and then, the sentry said, he had been selected to deliver the news to Creon. The chorus of Theban elders said that perhaps the burial had been an act of the gods, but Creon didn’t think so. No, Creon said, some insurrectionists were hiding in the city – bribery had taken place. Far too many people, snarled Creon, were corruptible under the sway of money.

And then a darker side of Creon emerged – a side so fanatically tied to the interests of the state that it made him willing to sacrifice individuals to what he perceived as the greater wellbeing. King Creon said to the poor sentry that if the perpetrator weren’t brought to him, then the sentry would be tortured until more truths emerged, and that this torture would make the poor sentry, in Creon’s words, “a living lesson against infamy” (134). The sentry protested – he hadn’t done anything. But Creon didn’t listen. Money, Creon said, could drive anyone into duplicity. With these words, Creon wheeled and went into the palace.

With Creon gone, the sentry fled. The chorus of old Thebans sung a song of meditation on the dominion of mankind on earth, and as it came to a close, they saw someone approaching. By the way, evidently some time elapsed during this choral song, because a couple of events have taken place. It was Antigone, under the guard of Theban soldiers. Antigone, soldiers said, had been the one who’d buried Polynices. Creon, having been alerted that his niece had been apprehended, stormed out of the palace. The sentry whom King Creon had threatened earlier explained what had happened. The sentry had returned to his post, terrified of the king’s threats. The guards who had been watching Polynices’ body tore the dirt off of it, so that the dead man lay naked under the blazing sun again. Then, the guards had gone to a hiding place, behind a hill and away from the stench of the decomposing body.

Sure enough, they’d seen her. Antigone had come, and, after screaming at the sight of her brother’s unburied corpse, she had begun his burial rites again. The guards had apprehended her at just this moment. But upon being arrested, Antigone had shown no fear.

Creon, seeing Antigone apprehended, asked Antigone to confirm the story. She confirmed it, and the sentry and other guards were freed from blame. Creon asked Antigone to explain herself – why had she contravened the king’s orders? Antigone’s explanation was clear and concise. Creon, Antigone said, was merely a man. His orders were the ephemeral instructions of a single human ruler. The mandate to bury one’s own dead family, on the other hand, was the timeless instruction of the gods. She had followed the latter, and she asked Creon, pointedly, whether she had been acting foolishly, or he had. Creon was not impressed. Creon said, in the Penguin Watling translation,

Ah, but you’ll see. The over-obstinate spirit

Is soonest broken; as the strongest iron will snap

If over-tempered in the fire to brittleness. . .

This girl’s proud spirit

Was first in evidence when she broke the law. . .

But, as I live. . .She shall not flout my orders with impunity.

My sister’s child – ay, were she even nearer,

Nearest and dearest, she should not escape

Full punishment – she, and her sister too,

Her partner, doubtless, in this burying. (139)

And with this unexpected added accusation, Creon ordered Ismene to be fetched from the palace. While Ismene was being fetched, Antigone told Creon she didn’t fear death. She said that all of Creon’s subjects agreed with her about the fact that Polynices deserved to be buried, although Creon’s subjects were too afraid to say anything. Creon shook his head. His subjects, Creon said, were on his side – the side of the state!

Antigone and her uncle Creon argued about what had happened, and Creon maintained his position stolidly. Polynices had been an enemy of the state of Thebes. Creon said enemies of the state remained enemies of the state, even after their deaths. Antigone said she was sharing love and forgiveness, and not hate, and at this, Creon had cutting words. He said “Go then, and share your love among the dead. / We’ll have no woman’s law here, while I live” (140). [music]

The Apprehension of the Sisters and the Intercession of Haemon

A moment later, Ismene was brought out of the palace. Oedipus’ older daughter was crying, and Creon criticized her bitterly, accusing her of treachery. Ismene then lied. She said yes, she had been in league with Antigone, and had planned the seditious act with her sister. But Antigone denied it. She didn’t want Ismene to die with her. Ismene, after all, had chosen life. Seeing the two sisters arguing, Creon said neither of them would be choosing anything – Antigone, after all, was as good as dead.Now, for the first time in the play, the subject of Antigone’s fiancé Haemon – remember that this is Creon’s son – came up. Ismene demanded to know of Creon would be so brutal as to murder his own son’s fiancé. And Creon, who is the speaker of an increasingly vicious series of one-liners as the play progresses, said the following. “Oh, there are other fields for [my son Haemon] to plough. . .No son of mine shall wed so vile a creature” (141). Having made it abundantly clear that he no longer wanted his son Haemon to plough his niece Antigone, Creon told the girls to get themselves into the palace, which was where women belonged.

With the sisters gone, Creon mused darkly to the chorus. The house of Oedipus, Creon said, was cursed. A curse on a house was as ineluctable as a great wave filled with a slurry of black sand. Creon’s gloomy meditations, however, were soon interrupted by the arrival of his son Haemon. Haemon had heard the bad news. Haemon had heard that his father had ordered the execution of his fiancé. Creon invited young Haemon to speak on the matter, and Haemon said he abided by his father’s decision. Creon approved, and treated his stricken son to a long speech about how women could be wily and deceptive, and that he had to uphold the interests of the state at all costs. In fact, king Creon said, the person who was appointed to lead the state must be obeyed at all costs – whether that person’s mandates were right, or wrong. Thus emphasizing that the power of the state was immutable and absolute, regardless of its morality, Creon concluded that he wouldn’t betray the state at any cost, least of all for a woman.

Haemon heard all of his father’s words. He said he knew that Creon was publicly unopposed. But he also said that everywhere there were whispers of pity for poor Antigone. People felt sorry for the bereaved sister of misguided Polynices. Haemon’s advice to his father Creon was diplomatic and perceptive, suggesting, as other moments in Sophocles’ Theban plays do, that at least some among the younger generation had the potential to overcome the obstinate self-certainty of the older generation. Young Haemon said to his father Creon, in the Penguin Watling translation,

Let not your first thought be your only thought,

Think if there cannot be some other way.

Surely, to think your own the only wisdom,

And yours the only word, the only will,

Betrays a shallow spirit, an empty heart.

It is no weakness for the wisest man

To learn when he is wrong, know when to yield.

So, on the margin of a flooded river

Trees bending to the torrent live unbroken,

While those that strain against it are snapped off. . .

I think, for what my young opinion’s worth,

That, good as it is to have infallible wisdom,

Since this is rarely found, the next best thing

Is to be willing to listen to wise advice. (145)

The chorus concurred that Haemon had made good points. But in the exchange that followed, Creon revealed, increasingly, that he was not a selfless champion of the collective, but instead a vengeful autocrat who would persecute anyone who questioned his decisions.

Because when Haemon again emphasized that the sympathies of the Theban people were generally with the poor, distraught Antigone, Creon growled that he didn’t care what the Theban people thought. Creon said he was the king, and was accountable only to himself. Would Haemon notice the paradoxical nature of his father’s political statements, and accuse Creon of unapologetically labeling his own personal prejudices and interests as those of the state? Why yes, actually, Haemon would do just this!

Haemon said that his father was no longer representative of the state of Thebes – he was just becoming a solitary autocrat, and would only be considered a good king on a deserted island, where he had no subjects. Now this is one of those moments at which, confronted by ironclad reasoning and clarity, you would hope that Creon might say,

You know what, son? There have been a lot of stubborn blowhards strutting around Thebes lately. You’re right. In trying to serve my state, I’m becoming as bad a demagogue and tyrant as anyone. You’ve helped me see that. Let’s get Antigone, and Ismene. I’m going to treat everyone to sandwiches, and some iced tea. It’s a good thing I’m capable of compromise, bec – [record scratch]

But no, Creon did not say this. What Creon actually said was that his son was a villain and a coward, and that his will was as feeble as a woman’s. Creon was on the verge of having Antigone brought out and executed right there in front of Haemon, but Haemon, cursing his father, strode off. [music]

Antigone’s Condemnation and the Coming of Tiresias

Creon’s wrath against Antigone was unabated, in spite of young Haemon’s earnest efforts. And Creon came up with a new plan. Antigone wouldn’t be immediately executed, he said. Instead, she’d be taken to an isolated spot in the desert and walled up inside a cave. Antigone would be given enough food to last a little while – Creon wanted this to happen so that his complicity in her death would be minimized in the eyes of the commonwealth of Thebes. Because – uh – I guess if you bury someone alive with a couple of hoagies and a juice box then you’re less guilty when they suffocate slash starve to death. Right. Well – that was Creon’s reasoning, anyway. After voicing this iffy plan, Creon strode offstage.Alone onstage again, the chorus mused on the power of love – love’s capacity to affect all, gods and men, righteous and unrighteous. Aphrodite, the chorus agreed, in some ways held sway over everyone. Then the chorus saw a sad sight. Antigone had emerged from the palace doors. The young woman told the chorus that she was on the way to her grave. The chorus attempted to console her, telling Antigone she was at least dying beautifully – that she had the prerogative of going to her grave by choice, which had a certain kind of nobility to it.

But Antigone said it was meaningless. The old Thebans of the chorus warned her that her death was a worthy homage to her brother and parents before her. But the chorus also told Antigone that “authority cannot afford to connive at disobedience. / You are the victim of your own self-will” (149). Antigone didn’t counter them.

Creon emerged from the palace and announced that it was time to carry out the sentence. Antigone said that at least she’d have the consolation of being with her great father Oedipus in death. And Antigone added that she’d done what she’d done for Polynices because a brother was a unique thing. She could, after all, have another husband, if a husband died. She could have another son, if a son died. But with Oedipus and Jocasta gone to their graves, she’d never have other brothers. Antigone asked the assembly of Theban elders what she had done wrong, and how she could have been saved, when she had only done what she had done out of devotion to her family. After a few more words, Antigone was led away.

In Antigone’s absence, the chorus of Theban elders reflected on the fates of other people who’d been imprisoned – Danae, the mother of Perseus, whose father had imprisoned her due to a prophecy that she’d bear a deadly grandson. A king called Lycurgus had tried to end the worship of Dionysus and been imprisoned for it. The chorus recollected the sufferings of a hero called Phineus – ancient strange legends of far-off places, and then an old man, a seer, arrived onstage.

His name was Tiresias. He has made an appearance in the play Oedipus the King – the great prophet who was a fixture in Greek mythology from Homer onward. Tiresias hailed King Creon, and said he had grave words for the ruler.

Tiresias told Creon, “[Y]ou stand on a razor’s edge” (152). He told Creon that in the midst of visions, he had suddenly heard the sounds of birds – birds killing each other. He’d heard a strange language, and the sound of tearing talons. Tiresias had attempted a sacrifice, but it would not burn – it only dripped filth into the ashes, but the flames would not accept it. It was a message, Tiresias said, that a blight was falling over Thebes, due to the continued abuse of poor Oedipus’ son Polynices, and the old seer Tiresias gave King Creon the following warning. Tiresias said:

Mark this, my son: all men fall into sin.

But sinning, he is not for ever lost

Hapless and helpless, who can make amends

And has not set his face against repentance.

Only a fool is governed by self-will.

Pay to the dead his due. Wound not the fallen. (153)

Creon, as before, was unmoved. Creon said that Polynices would be left to rot – even if the eagles themselves bore Polynices’ remains up to Mount Olympus, Polynices would still be left behind to decompose. Creon, as Oedipus had once done, accused Tiresias of voicing prophecies to benefit himself. But Tiresias denied it, and he offered Creon a final oracle. Creon, said the seer Tiresias, would answer for both the unburied corpse of Polynices, and the live burial of poor Antigone. The gods did not condone him, or his actions, and the Furies would tear him to shreds. Creon would not escape. Tiresias took his leave. [music]

Creon Finally Caves

The chorus warned Creon that Tiresias was never wrong, and Creon admitted that indeed Tiresias’ prophecy had seemed dire. The chorus asked permission to make a suggestion. Might it be that after having been warned by every living person in the city of Thebes, and having heard the dire portent of the most famous and most infallible prophet in all of Greece, that Creon would see reason and bury the remains of Polynices, and let poor Antigone out of her tomb? Could he maybe do this? Yes, actually, said Creon. Yeah, it was probably time to back down. Those words about hell and furies and the will of gods finally broke through to the budding dictator. As a matter of fact, Creon said, he couldn’t follow their advice soon enough.Creon personally grabbed shovels and spades, and he gathered some other Thebans. First, they would dig Polynices a proper grave. And then, he would join his countrymen in freeing Antigone. Which – uh – you would think he’d get the buried alive girl out first, rather than dealing with the dead guy, but as you’ve seen, Creon was sort of – dumb as [censored]. Thus disclosing his plan, Creon left the elders of Thebes onstage a final time. The chorus said a prayer to Dionysus, the patron deity of Thebes. An undetermined period of time passed. And then a messenger arrived onstage. Whatever had happened, the chorus knew – whatever had happened with Creon, and Antigone, and Haemon – they would hear of it from this newcomer.

The Horrors and Humiliation of Creon

Now, remember, when really intense things happen in Ancient Greek plays, they usually happen offstage, and they’re reported from a herald or messenger. That’s precisely the case in this particular scene of the play Antigone. The messenger who went to poor Antigone’s tomb said that Creon’s fate had fallen fast. Haemon was dead – he had taken his own life. Creon’s wife emerged from the palace. Slow down, she said. What had befallen her son? She wanted to know. The messenger told everyone what had happened. Polynices, who’d been partially eaten by dogs by this point, had been washed and then immolated over a blaze on fresh branches – his ashes had been carefully buried.Then, Creon and his men had gone to the rock chamber where Antigone had been entombed. He’d heard calamity from within, and, breaking through the already disturbed bricks that had walled up the tunnel, he’d seen something that would haunt him forever. Antigone had hanged herself with a rope “woven [of the] linen of her dress” (158). It was a scene unmistakably like Antigone’s mother’s death – Jocasta had also hung herself, and Oedipus had seen the corpse in just this same fashion. Creon, seeing young Haemon mourning the death of his fiancé, asked why young Haemon had come to see the tomb of his condemned fiancé.

Haemon turned to his father, his eyes dark and baleful, and spat in Creon’s face. He tore his sword out of his scabbard and went for Creon, but the king fled. With Haemon’s love dead, and his father thus violently estranged, Haemon had felt like he had no recourse. He’d fallen on his sword. As he bled to death, he staggered over to the suspended corpse of Antigone, his blood gushing over her linens and darkening her pale cheeks. And so, the messenger summarized, “Two bodies lie together, wedded in death, / Their bridal sleep a witness to the world / How great calamity can come to man / Through man’s perversity” (159). Hearing the news, Creon’s wife went silently back into the palace.

After a moment, the messenger and the old men of the chorus present in front of the palace remarked on the queen’s absence. The messenger went through the doors to check on her.

Just then, Creon arrived from the scene of his son’s death, carrying young Haemon’s body. Creon’s earlier sense of personal infallibility had been shattered by his losses. He had deserved the tragic loss, he said, acting wickedly – the punishment had been a divine one. But, even though he knelt there with his son’s blood all over him, Creon didn’t yet know all of it. The messenger from earlier reemerged from the palace, and Creon saw the bloody remains of his wife.

She had killed herself at the altar with a freshly sharpened knife, the messenger said. Her last words had been a violent curse against Creon. And Creon’s last words in the play, in contrast to the grandiloquent, self-assured monologues he voiced earlier, were fragmented and faltering. The failed king merely mumbled that he didn’t know what he would do, and that fate had crushed him.

The chorus of Theban elders, exhausted at the recent trauma of the Theban War, the feud over Polynices’ body, the violent obstinacy of the king, and the death of his niece, and wife and son, could only brokenly conclude that “This is the law / That, seeing the stricken heart / Of pride brought down, / We learn when we are old” (162). And that’s the end. [music]

Interpreting Antigone

So that takes us to the conclusion of Sophocles’ three Theban plays – one of the most famous dramatic cycles in literature. There are other versions of the story of Oedipus and his unfortunate children, but you’ve just heard the most famous one.

Charles Jalabert’s The Plague of Thebes (1842). The painting shows Antigone and her father going through Thebes while the city is still stricken by plague, perhaps on the way to Colonus.

In the previous two episodes, you heard a bit about how the other two Theban plays can be understood in the context of the Peloponnesian War. But the Peloponnesian War wasn’t the only thing going on in Athens in the late 400s. There was also an intellectual movement taking place – one of the most influential movements in philosophical history. This movement was called sophism. And although reading Antigone as a feminist tale, or as a timeless story about hubris chastened by fate is a great start, I also think that understanding Antigone within its contemporary intellectual context can help us understand how classical Athenians might have interpreted the play when it was first staged back in 441 BCE.

Sophism’s Background: Presocratic and Socratic Philosophy

I want to start by giving you a simple introduction to sophism. At a high altitude, sophism is really easy. Here goes. Ancient Mediterranean philosophy commonly begins with a group of philosophers called the Presocratics. There are many of these philosophers, and we’ve met some of them, but broadly speaking, what they had in common was that they came about before, or slightly before, or in some cases were roughly contemporary with the life of Socrates. The idea of Presocratics, and then Socrates, and then everything afterwards is a bit like the Christian one of BC and AD – in both cases a singular, pivotal figure is the fold around which history is understood.The historical Socrates lived from about 470-399 BCE. Socrates was about 25 years younger than Sophocles, and the play Antigone would have premiered around Socrates’ thirtieth birthday. It’s not unlikely that the philosopher Socrates might have seen the great playwright Sophocles’ award-winning play at the city Dionysia in 441 BCE, and as with all Greek tragedy, Antigone was a play that explored contemporary philosophical questions vital to classical Athens.

Socrates, however, with his famous snub nose, bulging eyes, and distinctly homely face, would not have been the only philosopher present in the theater in the spring of 441 BCE. In 441, Athens was an imperial powerhouse, with rivers of silver flowing into its coffers and novel construction projects rising up on the Acropolis. In addition to architects, and financiers, and opportunists of all sorts, the city was also filled with intellectuals. Some of these intellectuals were philosophers whom posterity would nickname “sophists.” Let’s talk about those sophists.

If you’ve taken a Philosophy 101 course, and you remember just one thing about Ancient Greek philosophy, it’s probably that the philosopher Plato wrote dialogues in which his teacher, Socrates, engaged in long debates with other thinkers, that Socrates’ method of debate was to pose questions to his fellow conversant, and that this style of argumentation is called the Socratic method. So Socrates lived first, and when Socrates was about 45, his pupil Plato was born, and a huge amount of Plato has been preserved, through which we have most of what we know about the philosophical climate of Athens in the mid to late 400s.

I have a feeling that if you’re the kind of person who seeks out educational podcasts, and regularly listens to this show, all of this is old news to you and you’re nodding and saying, “Yup, I got that. Socrates was Plato’s teacher, he taught with the Socratic method, gotcha.” So let’s take it up a level. The Platonic dialogues show Socrates talking to a lot of different people, on a lot of different subjects, generally winning them over with his persistent and inventive and sometimes annoying questions. But who were these people? Who is Socrates having discussions with page after page, dialogue after dialogue?

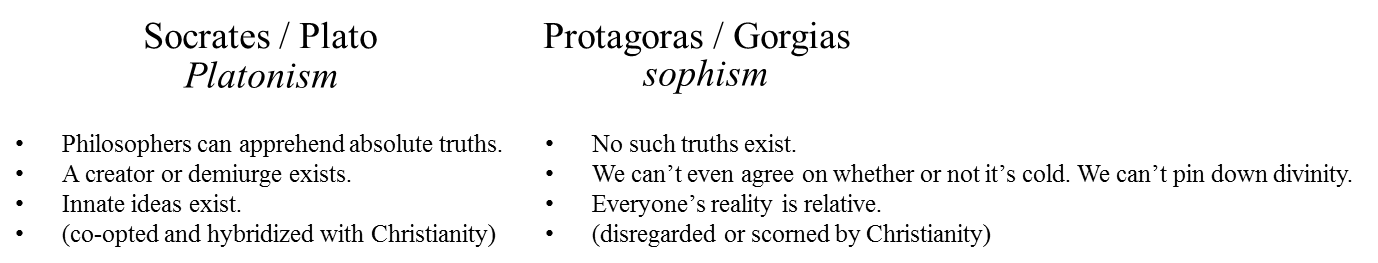

Many of Socrates’ fellow conversationalists – not all of them, but many of them, were sophists. These men had philosophical ideas that were disagreeable to Socrates, although it would really be more appropriate to say that they had ideas that were disagreeable to Plato, because the Socrates that we now have is a fictional character in the dialogues of the later philosopher Plato. So let’s do something we haven’t done in a little while. Let’s build a T-chart. On the left-hand side is Socrates/Plato. And on the right-hand side are the sophists. We’re going to nail down the biggest differences between them – again, Socrates and Plato on the left, sophists on the right.

Left hand column. The philosophy of Plato and Socrates valued discipline, and temperance, and mind over matter. Plato sought out eternal truisms for ethical self-conduct, the organization of the state, and the organization of the universe, arguing, famously, that an extrasensory realm of forms exists, and that this world beyond the senses is the paramount tier of reality. The willing death of Socrates at the hands of the Athenian state in 399 BCE is unmistakably the story of a martyr perishing for his beliefs, and it resonated with generations of Christian intellectuals who read it and copied it throughout Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages. Of all the hundreds of ancient philosophers who might have made it down to us, it’s not a coincidence that so much Plato was copied in the scriptoriums of the Middle Ages. Plato and his philosophical successors have been co-opted and spliced with Christianity for two thousand years.

Salvator Rosa’s Democritus and Protagoras, c. 1663. Had theological history gone differently, Socrates and Plato might be awkward footnotes to Democritus and Protagoras, who generated theories of atomic materialism and subjectivity in the 5th century BCE.

Sophist, originally, just meant “professor.” And the sophists were a group active in the Greek speaking world – especially in Athens, as professors of rhetoric and argumentation. In the Athens of the philosopher Socrates and the playwright Sophocles, rhetoric and argumentation were among the most important tools at the disposal of an ambitious person. The city’s most famous and successful men – Themistocles, and Pericles, and later Alcibiades – were frequently also its most capable orators. Oration, and rhetoric, and public speaking were supremely important in classical Athens, because if you could stand up in front of thousands of people and persuade them to cast a vote on something – purely through the power of speech, you had a whole lot of political clout. Connectedly, if you wanted your son to have a future in Athenian politics, you asked around town, and you found the best sophist you could afford, and got some weekly tutoring sessions going.

So the sophists were instructors who professionally taught speech and rhetoric to the wealthy youth of Athens. So far, that doesn’t really seem like it could be objectionable to anyone. The problem for Socrates and Plato was that the teachings of some of the more prominent sophists were directly contradictory to many of the core tenets of Platonic philosophy. Let’s talk about some of those teachings. Now, I know we’ve taken two turns away from Sophocles’ play Antigone. But remember that Antigone was staged for a specific audience, and that within that audience there would have been a group of professional instructors – again sophists, who were the most respected intellectuals of the day. Sophism was one of the main ideological forces at work in the Athens of Sophocles, and so I think it’s worth taking just a moment longer to explore the teachings of sophist philosophy, as it relates to Sophocles’ play, Antigone. [music]

Plato and the Sophists

There are about ten sophists on whom we have information from various sources – mostly Plato, but also Aristotle, the Roman historian Plutarch, and the third century CE historian Diogenes Laertius. All of them are worth studying in detail. But let’s focus on the sophists with whom Plato deals most extensively in the Socratic dialogues.Sophistry, today, is a fairly esoteric word, but it means using fallacious arguments that seem plausible on the surface in order to achieve a goal. You might tell your mom that all of the other kids were eating all of their Halloween candy, and so you thought that was what you were supposed to do, as well. Or, more pertinent to the play Antigone, you might tell your niece that she has to die in order to serve the interests of a state that did not actually want her to die. Generally, the word “sophistry,” to us today, means the assembly of logically unsound arguments, and we do see a few of these arguments throughout the play Antigone.

The reason that we have this word – again, “sophistry,” and that the word has negative connotations, is Plato. Plato’s Socrates, page after page, dismantles the philosophical systems of various contemporary thinkers – Hippias, Callicles, Thrasymachus, and Cratylus. Down they go, round after round, taken apart by the Swiss Army knife of the Socratic Method. And so it seems, through long stretches of the Platonic dialogues, that the sophists were a homogenous mob of interchangeable graybeards, all spinning a lot of flimflam and hullabaloo. Only, they weren’t. They definitely weren’t.

You only have to know one thing about Plato, and one general fact about the sophists, to understand why we need a T-chart for them. Let’s start with Plato. Particularly in the dialogues Cratylus and Theaetetus, and then in Book 7 of the Republic, Plato works out his most famous allegory – maybe the most famous allegory in all philosophy. This allegory is that most of us are trapped in a world of false impressions, like imprisoned people watching the shadows of things on a cave wall and believing that those shadows are reality. To Plato, though, a certain kind of person – a philosopher, of course – can escape from this illusory, lower form of reality, and go out into the nobler daylight of real trees, and the moon, and the sun. This lucky philosopher, because of his unique makeup, can perceive and understand the real essences of things – not just the hundred million imperfect tables out there in the world, but the ideal, original table, from which all other tables are made. The philosopher, in short, in Plato’s mind, has access to the world of forms – the world of original templates from which all imperfect earthly things are made. Love it, or hate it, that’s the core of Platonic philosophy. And the most important thing to remember about it, as far as the sophists are concerned, is that Plato did believe that a privileged section of people could comprehend a level of truths that were absolute and universal. Again, Plato believed in absolute and universal truths.

That takes us to the sophists, on the right side of the T-chart. The sophists, generally, did not share Plato’s belief that a realm of absolute reality exists beyond our senses. In fact, against Plato’s metaphysical system-building approach to philosophy, the sophists generally preached skepticism, and subjectivity. The sophists were fascinated by the fact that reality is radically different from person to person. Being rhetoricians and orators, they understood that even in the center of the civilized world – the assembly of Athens, in their opinion, truths could meld, and evolve, and turn on their heads. Any argument, the Sophists knew, had an inverse, and within the malleable realm of the human brain, truisms, and ethics, and even sensory perception all had a high capacity to change. What, the sophists wondered, was anyone doing talking about gods, or universal truths when we couldn’t even agree on whether or not a wind was cold? What were we doing talking about an unchanging eternal reality when we couldn’t even agree on which soup was tasty, and which one was yucky?

So now you have that T-chart in your mind – Plato on the left, sophists on the right. You know that Plato believed in a two-tier reality, with a sort of sludge of everyday people and false sense impressions on the bottom tier, and a shiny realm of philosophers and true forms on the top tier. And you know that sophists, who were generally skeptical of any universal truisms, would have dismissed Plato’s allegory of the cave and theory of forms as really silly if their actual writings had survived. So assuming that a 30-year-old Socrates was there at the Theater of Dionysus in 441 BCE when Antigone was first staged, we can also assume that a certain sophist was there, too. This sophist was a fixture in Athenian society – a well-funded teacher who had prepared countless youths for careers in politics. Just three years earlier, he had personally worked with the city’s de facto ruler Pericles on the constitution of a new colony in Southern Italy.3 He would have been about 49 years old. And his name was Protagoras. [music]

Protagoras and Sophist Relativism

Socrates, at this point still young and hungry, would have looked at the older Protagoras as a man with an established civic and philosophical reputation. As the first lines of Antigone were spoken – that dialogue between Ismene and Antigone – we can imagine Socrates staring across the orchestra at the wealthy and reputable Sophist philosopher Protagoras and maybe concocting some of his own ideas – those famous Socratic virtues of moderation in diet, the relinquishment of material possessions, and physical hardihood. These were exactly the kinds of virtues that might entice a hungry young intellectual like Socrates, as he looked at the older philosopher Protagoras. The whole of Platonic philosophy might have been born right there in 441 BCE at the premiere of Antigone.To return to the facts, though, whether or not Socrates and Protagoras attended Antigone in 441, and whether they knew about one another at that juncture, we do know a bit about Protagoras’ philosophy from several different sources.

An absolutely wonderful illustration of Ismene (left) and Antigone (right) with the younger sister’s tortured resolution captured in her posture and countenance. From Character Sketches of Romance, Fiction and Drama (1892) by Ebenezer Cobham Brewer.

This quote – “Man is the measure of all things,” is probably the most famous quote in all sophist philosophy. And it’s certainly the heart of what we know about Protagoras. Protagoras was, famously, an agnostic, evidently believing that if he couldn’t even trust his own sense perceptions, there was little cause to feel any confidence about the existence of divine beings. And, also famously, Protagoras was, according to one ancient source, “the first to claim that there are two contradictory arguments about everything.”6

For the record, I seriously doubt that Protagoras was probably the first human being to ever point out that there are multiple takes on things and that truth is at least somewhat relative. Ever since one cavewoman proclaimed that wearing a bear pelt was itchy and her friend said she thought bear pelts were comfortable, humans have understood that objective truth can be slippery. To return to classical Athens, though, and the philosophy of Protagoras, sophists like Protagoras were a major influence on the educational climate of the city.

It was a common rhetorical exercise in the 400s BCE to argue something, and then create a counterargument of equal weight. This rhetorical exercise helped budding young politicos prepare for their careers in the public sphere. But also, when practiced in great quantity, arguing something, and then arguing against it, had an effect on the two or three generations of sophists who practiced this technique. Beyond surely being excellent intellectual calisthenics, arguing, and then counterarguing, had the effect of making any spoken statement seem like little more than a nicely arranged bundle of words – and these words and literary devices could be used to manipulate human subjectivity into believing anything, at any time. In a political culture that made decisions based on the rhetoric of powerful speeches, and not based on data, or quantitative analysis, the power of speech must have seemed something almost supernatural.

In fact, another sophist, Gorgias, who was five years younger than Protagoras, thought a lot about the power of speech. Gorgias, just like Protagoras, might have also been at the world premiere of Sophocles’ Antigone. Gorgias famously argued that Helen of Troy was under no circumstances responsible for the Trojan War. Helen, said the sophist philosopher Gorgias, might have just been kidnapped or compelled by the gods to leave her Greek husband for a Trojan prince. But, the sophist philosopher Gorgias adds, even if Helen of Troy were just persuaded by spoken word – even if Helen just bowed beneath the power of her foreign lover’s rhetoric – she was still not guilty. Because the spoken word, to the Sophists, had a compulsive power that, when wielded by certain hands, could not be denied.

So there you have some of the very basic facts about sophism. It’s a philosophy that endorses relativism, and skepticism, and pays especially close attention to the power of language to form and distort our perceptions of reality. To the sophists, we can’t ever apprehend any timeless, omnipresent truths, because our reality is just shifting curtains of sense perceptions – curtains that can be manipulated by skilled orators and wordsmiths.

Sophism and Platonism: A Central Philosophical Divide

Let’s back up and look at that T-chart again, just for review. On the left-hand side is Socrates/Plato, Plato’s allegory of the cave, his theory of forms, and his notion that eternal unchanging truths exist and that philosophers can understand eternal truths. On the right-hand side are Protagoras and his fellow sophists, with their notions that there are no eternal truths, that language manipulates subjective reality, and, also by extension, that sophists themselves are uniquely powerful, because they are rhetorical superheroes. Both sides of the T-chart, you can see, were a bit self-important. Anyway, as the 400s BCE began to wind down, and Socrates began to have pupils, you can see that his pupils would have had some significant disagreements with the workaday sophist instructors who were out there, teaching the Athenian youth about how to argue.It’s important, before we jump back into Antigone, to pause for just a moment longer, and ponder those sophists on the right hand side of the T-chart, and their beliefs. Sophism, over the past two thousand years, has generally had an iffy reputation. After all, Plato and Christianity ended up emerging dominant, and Islam also shares most of Plato’s and Christianity’s core convictions – that there is an unchanging, divine reality, that this reality is understandable to certain select individuals, and that certain speech is divinely inspired, and immortally true. These ideas have been commonplace for a long time. But when we put Protagoras’ most famous idea – that “Man is the measure of all things” – next to them – all of a sudden, we’re confronted with the vertigo-inducing idea that all speech, and all writing, is simply the ductile and slippery outgrowth of human subjectivity.

Plato spars with sophism in dialogue after dialogue. But in spite of its seemingly radical skepticism, sophism, once in the hands of a thinker like Descartes, began to catalyze the scientific revolution. And the idea that language shapes our reality has been mainline in humanities scholarship, from the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis through the largely French postmodernism that pervaded the 1980s, 1990s, and later, my own graduate program. Sophists, then, far from being a bunch of feeble, nihilistic scribblers, as Plato often depicts them, were powerful thinkers whose ultimately simple and reasonable ideas about subjectivity have pervaded history since the Enlightenment.

So we’ve taken a little aside from Antigone, but I think it’s been a practical and useful one. During our little aside, we’ve built a T-chart that embodies two warring belief systems that were alive and well throughout much of the lifespan of classical Greek theater. And now it’s time to open up Antigone once more. We already know that in its closing moments, it is explicitly a play that criticizes hubris, or excessive pride. What I want to show you now is how this criticism embodies the intellectual currents of Athens in the 440s. If Socrates, and the sophist Protagoras really were there on that spring afternoon of 441 BCE, I think they would have found plenty to talk about after watching Sophocles’ play Antigone. [music]

Sophism and Self-Certainty in Sophocles’ Antigone

Antigone is, in many ways, a play about what happens when people stick to their convictions against all advice to the contrary. The play opens with Ismene trying to tell Antigone to please not throw her life away just so some dirt can be scattered over Polynices’ corpse. It comes to a climax when the frighteningly inflexible Creon, ignoring the eloquent counsel of his own son and the general sentiments of the Theban townspeople, buries his niece alive. In both the case of Antigone and the case of Creon, a certain stern, inflexible dedication to principles comes to the forefront.The obduracy of each of these characters is identical, although their temperaments and wishes are different. Stuck between a rock and a hard place, at a crucial turning point in the play, Antigone’s fiancé Haemon is trying to convince his father to show mercy on Antigone. Young Haemon tells his father,

It is no weakness for the wisest man

To learn when he is wrong, know when to yield.

So, on the margin of a flooded river

Trees bending to the torrent live unbroken,

While those that strain against it are snapped off. (145)

This dichotomy – of trees that bend within a storm, and survive, and then trees that remain rigid – this dichotomy runs through the play. Early on, Ismene tells her doomed sister that “[There is] [n]o sense in starting on a hopeless task” (29). Antigone does not object to the charge that her fixation is insane. She tells her sister, “Leave me alone / With my own madness. There is no punishment / Can rob me of my honorable death” (129). Although Ismene begs her sister to think of all who are still alive, Antigone doesn’t listen. From the opening scene in the play, Antigone refuses to bend to the torrent.

Ironically – and the ancient Greeks loved dramatic irony – the person who best articulates Antigone’s inflexibility is Creon himself. Creon observes Antigone’s unyielding desire to bury her brother, and remarks, “The over-obstinate spirit / Is soonest broken; as the strongest iron will snap / If over-tempered in the fire to brittleness” (128). And after Creon says this, bizarrely, he proves to be the most obstinate of all. Against the counsel of the Theban elders, against Antigone and Ismene, against the prophet Tiresias, and finally, against his own son, Creon remains adamant. And a line that we heard before – one that Creon’s son Haemon delivers to him near the play’s climax – this line might have been spoken by a Sophist.

I think, [Haemon says] for what my young opinion’s worth,

That, good as it is to have infallible wisdom,

Since this is rarely found, the next best thing

Is to be willing to listen to wise advice. (145)

This exactly what Creon needs to hear. But as the play continues, too many rely on what they perceive as their own infallible wisdom, and too few listen to advice. Proud Antigone hangs herself. Haemon kills himself in a fit of grief, as does his mother, and at the end it, Creon vaguely mumbles about having been overtaken by fate. Almost everyone dies, and almost no one learns anything. It is an ending about hubris, obviously. But more specifically, all of Antigone is a play about the grave perils of self-certainty.

We generally think of self-certainty as a good thing. Various creeds of all stamps invite us to have faith, and to trust in an extrasensory world of beings and principles, and, against the counsel of others, to have, in Ralph Waldo Emerson’s words, “Self-Reliance.” But self-reliance, as Sophocles’ Antigone demonstrates, has its limitations.

To a Sophist – to Protagoras, or Gorgias, as they sat there in the theater of Dionysus, Antigone’s morbid obstinacy, and Creon’s imperious stubbornness would have seemed especially idiotic. Because Protagoras, Gorgias, and the other sophist philosophers Plato so disliked did not believe in absolutes, or the possibility of certainty. The sophists believed in the limitless fallibility of the individual. The sophists believed that people can become ensnared by lofty sounding rhetoric and subsequently begin harboring outlandish and dangerous ideas, and even worse, acting on these ideas. The sophists had little confidence in the existence of divine beings, and so to them, Antigone’s morose march to her own death would have seemed unnecessary, rather than an act of heroic individualism, as it’s often interpreted today.

Today, we tend to think of sophism, and any philosophical system that endorses skepticism and relativism – we tend to think of all of these philosophical systems as irritating dead ends. After all, if we really can’t know anything, and are prisoners of our fallible subjectivity, then what the hell is the point of anything, and how can we even know that we don’t know anything? This is the analysis that Plato makes of Protagoras in the dialogue Theaetetus, and Aristotle also reaches in Metaphysics.7 Both philosophers came to the conclusion that radical skepticism is a dead end, and their philosophical system building can be understood as a response to the frightening black pit dug by the sophists. The same tug-of-war happened later in philosophical history, when Kant responded to Hume, and more recently, when Alan Sokal and Jean Bricmont responded to Lacan, Derrida, and Kristeva, and other postmodern thinkers, if you happen to be into later twentieth-century philosophy.8 Sophism, whatever it happens to be called in any given century, is a typhoon. No argument can stand against it. The problem is, that like a real typhoon, sophism leaves in its wake an empty crater. And empty craters are not, philosophically speaking, very usable.

But however destructive sophism is, there’s also something inherently healthy, and humble about sophism which I think that Sophocles understood and wove into the lines of the play Antigone. Skepticism, and relativism – really the right and left arms of most sophists’ ideologies – skepticism and relativism don’t exactly inspire impetuous or violent action. The idea that my truth might be quite different from your truth – that idea doesn’t encourage us to shout at one another. It encourages us to ask each other questions, turning jingoism into curiosity, and sometimes, turning xenophobia into xenophilia. Sophism, and all of its philosophical offshoots, then, are as irritating to dogmatists and philosophical system-builders as they are healthy for civilization as a whole.

If we believe that we are infinitely capable of falling into errors and misconceptions, then our best chance of survival is the collaborative exchange of information – exchange like the one fostered by Athenian democracy.9 Hopeful young Haemon tells his father “good as it is to have infallible wisdom, / Since this is rarely found, the next best thing / Is to be willing to listen to wise advice” (145). And we know, hearing Haemon’s gentle, persuasive line, that it’s the best thing that possibly could have been said. But Creon ignores it, certain as he is in the primacy of himself and his state, and Antigone ignores her sister, due to her brooding obsession with correct burial, and in the end, everyone loses.

So Sophocles’ final Theban play closes with a lesson. It’s a lesson, like many in Greek tragedy, that cautions the reader against hubris. But more specifically, it’s a lesson that tells us, in the face of our self-certainty and our obsessions with extrasensory phenomena, to adapt and compromise, to admit when we are wrong, and to stay alive for the sake of the people whom we love. The seasoned, sophist Protagoras, watching Antigone in the mid-spring of 441, would have nodded and found Antigone a rather sad and cross girl who’d pointlessly gone to her grave. But thirty-year-old Socrates, watching Antigone – Socrates would have seen great heroism in the main character’s relentless adamancy. And 42 years later, Socrates, like just Antigone does, against the counsel of everyone around him, went to trial, and killed himself for the sake of his unbudging beliefs. [music]

Jacques-Louis David’s The Death of Socrates (1787), justifiably one of the most famous examples of neoclassical art.

Moving on to Euripides’ Medea

Well, folks, I hope you’ve enjoyed these shows on Sophocles’ three Theban plays, and always, I advise you to read them for yourselves, too. With the last six shows on the Oresteia and then the three Theban plays, I ended up cutting down pages and pages of splendid quotes, and I think that if you check out any of these six plays for yourself, you’ll find them just as rich as I have, and just as likely, they’ll speak to you in ways distinct to who you are, and the experiences that you’ve had.So we’ve finished the Oresteian trilogy of Aeschylus and the Theban plays of Sophocles. That’s great. And now, I’m excited to say, we’re going on to the work of the playwright Euripides, specifically a play that premiered in 331 BCE – ten years after Antigone, and like Antigone, a play with a heroine at its center. This play is called Medea.

Medea is one of my all-time favorite characters in literature. I don’t want to spoil a thing about her story, which I’ll tell in full very soon. For now, if you’ve never heard the tale of Medea, let me tell you this. In the play that we just read together, poor willful Antigone faces the opposition of her dogmatic uncle and the political system of Thebes, and knows ahead of time that resisting Creon and his enforcers will be futile. Eventually, she’s compelled to be buried alive, her only consolation that she did not compromise with her oppressor. That’s Antigone. Now, Medea, in the play we’ll read next time – Medea will also face opposition – the opposition of her king, and husband, and her entire city. But while Antigone’s instinct seems to be to accept her surrogate place in her city’s power structure and die a martyr for her ideas, Medea’s instinct is different. Medea’s instinct is to fight. And as a sorceress from a faraway land – one schooled in black magic and pharmacology, subterfuge and deadly toxins, Medea isn’t exactly a pushover. In Episode 33: Woman the Barbarian, we’re going to learn why the playwright Euripides, with his unorthodox beliefs and shocking endings, was the black sheep, and ultimately the most influential of the great Athenian dramatists who have come down to us. Thanks for listening to Literature and History. There’s a quiz on this program available in the details section of your podcast app if you want to review what you’ve learned. I’ve got a song coming up if you want to hear it. Otherwise Euripides, Medea and I will see you next time.

Still listening? Okay, so, I got to thinking about Socrates and Plato. I’ve read a lot of the Socratic dialogues, and, as may have been clear from the content of this and other episodes, I have not yet been persuaded that Plato is the tower of intellectual clarity that many seem to believe him to be. So I wrote the following song, in which Socrates and Plato, using the Socratic method, discuss their philosophy in a musical duet. This one is called “The Philosophy of Socratato.” Hope it’s fun, and again I’ll be back next time with Euripides’ Medea.

References

2.^ Sophocles. The Three Theban Plays. Translated by Robert Fagles and with an Introduction and Notes by Bernard Knox. Penguin Classics, 1984, pp. 63-4.

3.^ See Plutarch’s Life of Pericles (36).

4.^ Waterfield, Robin. The First Philosophers: The Presocratics and Sophists. Oxford University Press, 2000, p. 211.

5.^ Ibid, p. 211.

7.^ See Plato, Theatetus 16.1 and Aristotle, Metaphysics, 1007 18-25.

8.^ Kant’s Prolegnomena to Any Future Metaphysics (1783) and Sokal, Alan and Bricmont, Jean. Fashionable Nonsense: Postmodern Intellectuals’ Abuse of Science (Picador, 1999). Of course Kant is mainly concerned with Hume’s doctrine of causality, just as Sokal and Bricmont mainly object to postmodernism’s misconceptions about science, but numerous moments of each argument essentially argue against radical skepticism, just like Plato’s Theaetetus.

9.^ In reading Theaetetus 166-7, Robin Waterfield writes, “So, in Protagoras’ case, the idea that nothing is false must be modified: though nothing is false, some beliefs are better than others, and in the political sphere that means they are more conducive to utilitarian harmony.