Episode 112: Pre-Islamic Arabic Poetry

Prior to the dawn of Islam, the Arabian Peninsula had a great poetic tradition, with many genres, and many poets who are still celebrated and studied today.

| Read Transcription | References and Notes |

| Quiz | Episode Song |

| Episode on Spotify | Episode on Apple Podcasts |

| Previous Show | Next Show |

Episode 112: Pre-Islamic Arabic Poetry

Gold Sponsors

David Love

Andy Olson

Andy Qualls

Bill Harris

Jeremy Hanks

Laurent Callot

Maddao

ml cohen

Nate Stevens

Olga Gologan

Steve baldwin

Silver Sponsors

Alexander D Silver

Boaz Munro

Charlie Wilson

Danny Sherrard

David

Ellen Ivens

Hannah

Anonymous

John Weretka

Jonathan Thomas

Lauris van Rijn

Michael Davis

Michael Sanchez

Mike Roach

Oscar Lamont

rebye

Susan Hall

Top Clean

Sponsors

Carl-Henrik Naucler

Malcolm

Stephen Connelly

Angela Rebrec

Chris Guest

A Chowdhury

A. Jesse Jiryu Davis

Aaron Burda

Abdul the Magnificent

Aksel Gundersen Kolsung

Andrew Dunn

Anthony Tumbarello

Ariela Kilinsky

Arvind Subramanian

Basak Balkan

Bendta Schroeder

Benjamin Bartemes

Bob Tronson

Brian Conn

Carl Silva

Chief Brody

Chris Auriemma

Chris Brademeyer

Chris Ritter

Chris Tanzola

Christophe Mandy

Christopher Centamore

Chuck

Cody Moore

Daniel Stipe

David Macher

David Stewart

Denim Wizard

Doug Sovde

Earl Killian

Elijah Peterson

Eliza Turner

Elizabeth Lowe

Eric McDowell

Erik Trewitt

Evasive Species

Ezio X

Francine

FuzzyKittens

Garlonga

Jacob Elster

Jason Davidoff

JD Mal

Jill Palethorpe

Joan Harrington

joanna jansen

Joe Purden

John Barch

john kabasakalis

John-Daniel Encel

Jonathan Whitmore

Jonathon Lance

Joran Tibor

Joseph Flynn

Joseph Maltby

Joshua Edson

Joshua Hardy

Julius Barbanel

Kathrin Lichtenberg

Kathy Chapman

Kyle Pustola

Lat Resnik

Laura Ormsby

Le Tran-Thi

Leonardo Betzler

Maria Anna Karga

Marieke Knol

Mark Griggs

MarkV

Matt Edwards

Matt Hamblen

Maury K Kemper

Mike Beard

Mike Sharland

Mike White

Morten Rasmussen

Mr Jim

Nassef Perdomo

Neil Patten

Nick

noah brody

Oli Pate

Oliver

Pat

Paul Camp

Pete Parker

pfschmywngzt

Richard Greydanus

Riley Bahre

Robert Auers

Rocaphoria

De Sulis Minerva

Rosa

Ryan Shaffer

Ryan Walsh

Ryan Walsh

Shaun

Sherry B

Sonya Andrews

stacy steiner

Steven Laden

Stijn van Dooren

SUSAN ANGLES

susan butterick

Ted Humphrey

The Curator

Thomas Leech

Thomas Liekens

Thomas Skousen

Tim Rosolino

Tobias Weber

Tom Wilson

Torakoro

Trey Allen

Troy

Valentina Tondato Da Ruos

vika

Vincent

William Coughlin

Xylem

Zak Gillman

In this program, we will start at the beginning, and consider the work of about twenty poets who lived in and around the Arabian Peninsula, mostly during the 500s CE. The corpus of Pre-Islamic poetry, sometimes called Jahili poetry, that has come down to us from Late Antiquity is a marvelous body of work, with disciplined attention to rhyme and meter, a variety and richness of literary devices like metaphor, simile, consonance and assonance, an encyclopedia of place names and references to the flora, fauna, and topography of the ancient peninsula, and a variety of well-developed genres, demonstrating that by the year 600, Arabic poetry was a refined artform that had already been around for a long time. The story of Pre-Islamic Arabic poetry, however, is also a complicated one – especially for newcomers. While the period’s most famous works are still taught to students and studied by scholars all over the Arab world, Jahili Arabic poetry was written down, collected, collated, and anthologized long after the 500s had passed, in the cities and scholarly circles of later Islamic caliphates, which means that the Pre-Islamic Arabic poetry that we possess is likely not a neutral sampling of the poems Arabs were writing before the pivotal events of the 600s, but instead a selection of texts curated to portray the pagan past in various ways that served the later Islamic present.

My goal in this program, then, is first to introduce you to the historical and performance context of Pre-Islamic Arabic poetry – how this poetry was produced and circulated, how professional poets likely made a living, and what Medieval Islamic historians have to tell us about the world of the Pre-Islamic poets. Then I want to look at some of the main genres of the earliest Arabic poetry that we now possess – the qasida, or ode, the Mu’allaqat, a collection of seven famous odes, the sa‘alik, or vagabond poem, the fakhr, or boast poem, the madeeh, or panegyric, the ritha, or lament, and the hija, or satire. Once we get a sense of how these different genres of content weave together in the extant body of the earliest surviving Arabic poetry, we can learn about how this poetry was compiled and produced in the centuries after 750 CE, and how the efforts of later Muslim intellectuals shaped the canon of Arabic literature that predated Muhammad.

In our previous program, we got a sense of what was going on in and around the Arabian Peninsula by the 500s. We learned that the Byzantine and Sasanian empires had long and established traditions of using Arab auxiliaries to fight wars in what’s today Syria, Jordan, and Iraq, and that two Arab client kingdoms, the Ghassanids to the northwest, and the Lakhmids to the northeast had a great deal of influence over the culture of the peninsula by the time Muhammad was born in about 570. We learned that Late Antique kingdoms seated in modern-day Yemen and Ethiopia, Himyar and Aksum, respectively, exerted a lot of sway in Arabia, especially over the trade towns, tribes, and tribal federations of the southern peninsula. We learned that communities of Arab Jews and Arab Christians were seeded throughout Arabia, and that in the greater world where Arabic was one of the spoken languages, in cities like Damascus, al-Hira, Antioch, Mecca, and Yathrib, monotheism mingled freely with the peninsula’s indigenous polytheistic religions. We learned that Arabia had been crisscrossed with international trade since the Hellenistic period, that its Red Sea and Persian Gulf coasts were home to strings of ports and port towns, and toward the end of the previous episode, we got a sense of the complexity of the word “tribe” in the context of Late Antique Arabia. “Tribe,” in the 500s CE, could indeed mean a group of Bedouins in the peninsula’s wilderness, herding camels, migrating with the seasons, and trading whenever it was advantageous. But “tribe,” in the 500s CE, could also describe a genetically related group in an urban area who’d formed a trade syndicate, or who had created a monopoly on the production of goods, or embarked on some other commercial enterprise. Arabia, by the 500s, was not some lonely, untenanted place, but instead, the axis of three continents, and home to many different kinds of people. That its literature, by this juncture, was quite highly developed, then, is no surprise. So let’s begin our long journey into Arabic literature with some very basic stuff. [music]

Pre-Islamic Arabic Poetry: The Basics

The most elementary thing that a newcomer to Pre-Islamic Arabic poetry needs to know is that this was oral poetry, delivered via public performances, rather than circulated in papyrus, or parchment, or paper manuscripts. By the 500s CE, across the world where Arabic was spoken, public poetry performances were one of the main entertainments that speakers of Arabic enjoyed. As the eleventh-century North African literary scholar and poet ibn Rashiq wrote, describing the bygone days before Islam,When there appeared a poet in a family of the Arabs, the other tribes round about would gather together to that family and wish them joy of their good luck. Feasts would be got ready, the women of the tribe would join together in bands, playing upon lutes, as they were wont to do at bridals, and the men and boys would congratulate one another; for a poet was a defence to the honour of them all, a weapon to ward off insult from their good name, and a means of perpetuating their glorious deeds and of establishing their fame for ever. And they used not to wish one another joy but for three things – the birth of a boy, the coming to light of a poet, and the [birth] of a noble mare.2

Perhaps the description is a little exaggerated – a later poet fantasizing about a prior period when poets were revered and celebrated. But, whether or not poets were actually lauded celebrities, in Pre-Islamic Arabia, public recitations nonetheless seem to have been central tribal and civic entertainments. Ages before copyright and the mechanical reproduction of texts, if you were a poet, your best bet at getting paid was to find a patron, or to give excellent public recitations, or ideally, both.

Part of Late Antique Arabic performance culture was a person called the rawi, or “reciter,” or “teller,” who might perform his own compositions, or the compositions of just one poet who’d commissioned him to do so, or some medley of poems pertinent to the occasion at hand. Like ancient Greece’s Pindar, or Sappho, ancient Arabic rawis were bards who could call to mind classics as well as original work, and some rawis likely began by doing covers, so to speak, only to later begin mixing in their own original material.

Because Jahili poetry in Arabic was performed live and for specific occasions, its genres – the satire, the lament, the panegyric, the individual or clan boast poem, and so on – were born to serve specific performance contexts. A Lakhmid court poet might praise the Persian client king with a panegyric. A grieving widow or parent might commission, or deliver a public lamentation. At a trade fair, commercial opponents might hire poets to sing the praises of their own organizations and lampoon the competition. The occasional poetry of antiquity, on the Arabian Peninsula and everywhere else, was often engineered for delivery at very specific times and places.

We tend, today, to have a romantic picture in our heads when we envision a poet – a solitary individual setting down lines that reflect the deepest reservoirs of her emotional experience. Some Jahili poetry is quite personal, just like this. Largely first person in composition, a lot of the poetry we’ll consider in this show is indeed about the emotional experiences of individual poets – melancholy, loss, love, and the lonely life of a nomad. One of its main genres, the sa’alik, or vagabond poem, chronicles the bitterness and resolution of the solitary Bedouin, cut off from tribes and towns for varying reasons, and left to wander among the harsh beauties of the desert astride a trusty camel or horse. The qasida, or ode, was almost always set in the desert hinterlands, ancient Arabic odes having a variety of melancholy first person speakers reflecting on abandoned camps and settlements, loves, losses, wars, friends, and other autobiographical subjects. However, sometimes the most seemingly personal moments of Pre-Islamic Arabic poetry – a dirge for a lost lover or meditation on the speaker’s bygone youth – can suddenly change into a paean for a patron or praises to a sponsoring tribe – demonstrating that Jahili poetry was an artform born from a market economy as much as a desire for individual artistic expression. And on this subject – on the subject of the social role that poets could play on the peninsula during the 500s – I want to tell you a quick story from the annals of later Arabic literary history.

The Story of Al-‘Asha and the Quraysh

Pre-Islamic poets, at least according to later Islamic-Arab literary critics, could be extremely formidable propagandists. A story survives in a text called Kitab al-Aghani or Book of Songs, attributed to the tenth century literary historian Abu al-Faraj al-Isfahani. And the Book of Songs tells a story about a certain poet who went to visit Muhammad. This poet’s name was Maymoon ibn Qays al-A‘sha, usually known by his laqab, or nickname, al-A‘sha, which means “man of poor sight.” Poor al-A‘sha’s sight might have been bad, but by the 610s and 620s, al-A‘sha was a successful itinerant poet whose oral compositions could have a powerful effect on inter-tribal politics. Al-A‘sha was a working bard, familiar with the peninsula’s pagans and Christians, fond of wine and not known for possessing any especially austere personal morality. The tenth-century Book of Songs tells the tale of how the earlier poet al-A‘sha, having heard of the rising reputation of the Prophet Muhammad, went to recite a praise poem for Muhammad. At that time, Muhammad was in conflict with Quraysh tribe that dominated Mecca. One of its principal merchants and leaders was named Abu Sufyan. Although Abu Sufyan eventually came around to Islam, at this juncture he was opposed to Muhammad. When Abu Sufyan learned that the poet al-A‘sha was planning a praise poem to Muhammad, Abu Sufyan and the other Quraysh tribe leaders confronted the poet.Muhammad’s enemies first confirmed that indeed the poet al-A‘sha was planning to recite a madeeh, or praise poem, to Muhammad. Abu Sufyan warned the poet – Muhammad’s new religion was planning all sorts of prohibitions, and would lay down strictures on some of the very pleasures that the poet al-A‘sha enjoyed. For instance, the Quraysh leader warned, Muhammad was planning to forbid fornication. The poet al-A‘sha, an older man by this time, shrugged, saying that he hadn’t necessarily abandoned sex, but that it had abandoned him. The Quraysh leaders said Muhammad planned to outlaw gambling. Al-A‘sha said this would be okay – the Prophet would probably offer something else nice to compensate for the pastime of gambling. The Quraysh leaders said that Muhammad would outlaw usury. That, replied the poet al-A‘sha, didn’t apply to him – he’d neither been a borrower, nor a lender. The Quraysh said Muhammad planned to forbid the drinking of wine. And even this didn’t seem to deter the poet al-A‘sha, who said he could drink some water.

Eugène Alexis Girardet’s Bedouins in the Desert. The qasida of Pre-Islamic Arabic poetry often begins at the site of an abandoned camp.

This story, written down three centuries after it allegedly took place, may be vastly exaggerated, or altogether untrue. A large herd of camels in exchange for not writing a poem is a bargain any writer would be gratified to receive, and in the tenth-century Book of Songs and other works of later Arabic literary history, poets are often heroic figures, their pride, volatility, and scandalous behavior spellbinding to the anthologists who recorded their deeds during the later, tamer centuries of the caliphates. Still, the story of al-A‘sha carries a few important grains of truth. The first is that the public recitation of a rawi, or reciter, could be a powerful force in making or breaking the reputation of a person, or tribe, or organization. The second is that one of Pre-Islamic society’s distinguishing features was a culture of free speech. Lacking theocratic rule or libel laws, an Arab poet in Mecca in 620 likely had more freedom of expression than his counterpart up in Constantinople, where law codes and orthodox ears might deem any given speech slander or heresy. The third is that Pre-Islamic Arabic poetry does seem to have enjoyed a level of esteem beyond that of a mere festival entertainment. The pagan Arab poet was known as a sha‘ir, a shamanic figure capable of creating al-sihr halal, or “legitimate magic,” in connection with the spirit world through a jinn.4 Poets, then, could serve commercial purposes at trade fairs and the intersections of bazaars, but at the rural, tribal level, they were also counselors and luminaries, their unique eloquence understood as an otherworldly gift.

Inasmuch as Pre-Islamic Arabic poetry should be understood as a public, performance based artform that served various roles among the peninsula’s various classes, religions, and ethnic groups, it’s also different than any of the oral poetry we’ve met thus far in the Literature and History podcast. Arabic literature’s surviving pagan poetry is almost uniformly voiced by first person speakers. It records, more often than not, the experience of the contemporary individual, rather than recounting some well-known poetic saga, or partial poetic saga. We might expect, for instance, Pre-Islamic Arabic poetry to contain theological history – perhaps the story of the great Meccan goddesses al-Lat, Manat, and al-Uzza, or the creation of the world, or for the peninsula’s pagan poetry to chronicle the deeds of folk heroes from this or that region. The ancient Greek bard, after all, was accountable to performing set pieces from the epic cycle, or singing the deeds of Hercules, or of the heroes of ancient Thebes, Athens, or Corinth. Contrastingly, Pre-Islamic Arabic poetry is more likely to be about individual experience in the contemporary world – experience with love, loss, sex, war, and exile, rather than pantheons of deities and deeds of heroes.

Let’s talk for a moment about the prosody – in other words the meter and rhyme – of Pre-Islamic Arabic poetry. As we have learned in past episodes, rhyme and meter in oral cultures were not florid decorations, but instead mnemonic devices designed to help bards keep hundreds, and probably thousands of lines of poems in their memories at all times. The most famous form of ancient Arabic poetry is the qasida, or ode, related to the verb qasada, or quest, or journey toward something. We should note that in modern Arabic, qasida is synonymous with the word “poem,” regardless of what the poem is about. But, modern Arabic usage aside, in studies of ancient Arabic poetry, qasida means something very specific. The Late Antique qasida, which almost always involved a desert journey, had several different standard sections to it, and we’ll get into the details of this very soon. While the qasida’s contents might vary, the ancient Arabic ode had a very specific meter – pairs of hemistichs, or half lines, where every other half line shared an end rhyme – the same end rhyme throughout the whole poem. As qasidas had somewhere between ten and a hundred lines, this means that the composers of ancient Arabic odes had to dig deep to continue the same rhyme throughout the entire poem – rather than going ABAB, or AABBCC, the qasida continues AAAA, and so on, with its end rhymes, as in “Roses are red, violets are blue / Sugar is sweet, and so are you. / All of the lines have this rhyme, too. / This was a challenge, as poets knew. / Eighty of these rhymed through and through, / Jahili poets were quite a crew” – in other words, a lot of end rhymes, all the same. There were a number of other different meter and rhyme schemes in early Arabic poetry – Classical Arabic poetry has about fifteen.5 And blank verse, which has no useful mnemonic engineering to help the bard recall lines, was not part of Pre-Islamic Arabic poetry.

The Translations and Prosody of Early Arabic Poetry

Jean-Léon Gérôme’s Riders Crossing the Desert (1870). Jahili poetry frequently features first person speakers, mounted and ruminating in desert landscapes.

There is another issue related to translation that I wanted to introduce before we actually get some early Arabic poetry onto our desk and read it. Today, when Arabic poetry is rendered into English, it is most often translated as blank verse. Blank verse translation lets translators focus on subtle shades of meaning and exact vocabulary, even though such accuracy comes at the expense of musicality. Earlier English language translations of Arabic poetry attempted to render this poetry into familiar English poetic meters with end rhymes, and even worse, to make Classical Arabic sound like Elizabethan English, with thees and thous and syncope rammed awkwardly into barren desert landscapes, long abandoned campsites, and tribal intrigues.

Newcomers to Pre-Islamic Arabic poetry have alternatives the needlessly florid English translations of yesteryear. Unfortunately, however, there is no sizable sourcebook from which English speakers can learn about the body of literature that we’re about to dig into. Modern English language anthologies of Arabic poetry exist – this episode will make use of a Penguin and an NYU anthology, for instance, but these compilations only have a few Pre-Islamic poems. Older translations, like Charles James Lyall’s translation of the eighth-century Mufaddaliyat, done in 1918, and A.J. Arberry’s translation of the Mu’allaqat, published in 1957, contain a wider sampling of the earliest Arabic poetry, but these are old translations, with some of the issues that I described a moment ago. So, in the remainder of this program, out of necessity, I’ll be quoting from a variety of translations, both old and new. My goal is to give you a clear, organized introduction to the different genres of Pre-Islamic Arabic poetry – what they sound like, and what they contain. Because what you’re about to hear will be organized by genre and content, rather than individual author, I won’t name every poet whose work is quoted, nor the translation from which each quote is taken. If you’re interested, though, this episode’s transcription, linked in the show notes to this episode in your podcast app, has footnotes to the exact source of everything quoted.

So, let’s begin by looking at the qasida, again the ode, the most famous form of Pre-Islamic Arabic poetry. Early Arabic qasidas have fairly standard formal conventions, a high degree of literary sophistication, and the most prominent of them are still taught as standard Arabic literature curriculum today. While generally in this program, I’ll focus on poetry rather than poets, one qasida is sufficiently famous that we should take a long look at it from end to end, and consider its author. Scholar Robert Irwin, considering the poet Imru al-Qays’ Mu‘allaqah, calls this poem “probably the most famous poem in the Arabic language,” so the ode we are about to read is in all likelihood a good place to start.6 Let’s go back in time, then, to about 530 CE, and read the Mu‘allaqah of poet Imru al-Qays, and start to get our bearings with Pre-Islamic Arabic poetry. I’ll say ahead of time that most of my quotes from Imru al-Qays’ ode will come from A.J. Arberry’s book, The Seven Golden Odes, published by George Allen in 1957. [music]

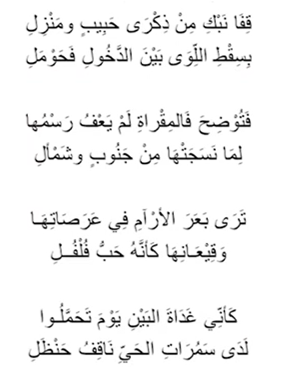

The Mu’Allaqa of Imru Al-Qays

Hemistichs from the Mu’allaqah of Imru al-Qays, some of the most famous lines in Pre-Islamic Arabic poetry.

There are a lot of legends about the poet Imru al-Qays. In one, Imru al-Qays, seeking help in Constantinople, had a tryst with the emperor Justinian’s daughter. On the way back home, the poet died on when he put on a poisoned robe – a gift from the angry emperor. In another, the poet’s father, learning that Imru al-Qays desired to be a poet, exiled the young prince, who afterward wandered among the tribes of Arabia, an aristocrat cast out for his artistic aspirations. In this same legend, when the poet’s father died, Imru al-Qays was angry not so much about the old man’s demise, but that he was now required to avenge it.7 In another legend about Imru al-Qays, the poet’s friend, another poet named as-Samaw’al, promised to keep five suits of armor safe for Imru al-Qays during al-Qays’ expedition up to Constantinople. Al-Qays died, and his friend was so steadfast and loyal to al-Qays that as-Samaw’al allowed his own son to be executed in front of him rather than surrendering his friend and fellow poet’s suits of armor.8

These legends about Imru al-Qays, who lived during the early 500s, were recorded during the 900s, and they depict a fraught, tragic figure whose most famous poem is indeed a melancholy and embittered soliloquy. The poem is known as the Mu’allaqah of Imru al-Qays – I’ll explain what the title of this poem means momentarily – for now let’s read the thing. The Mu’allaqah of the poet Imru al-Qays runs about 90 lines in length. The lines are very long and dense, so I won’t quote it in full.9 Here’s the opening – and I will tell you in advance that it begins with the poet looking forlornly out into an abandoned desert camp, and then sharing his reminiscences with us.

Beyond that reef of sand, recalling a house

And a lady, dismount where the winds cross

Cleaning the still extant traces of colony between

Four famous dunes. Like pepper-seeds in the distance

The dung of white stags in courtyards and cisterns,

Resin blew, hard on the eyes, one morning

Beside the acacia watching the camels going.

And now, for all remonstrance and talk of patience

I will grieve, somewhere in this comfortless ruin

And make a place and my peace with the past.

[Those] were good days with the clover-smelling wenches.

Best by the pool when I caught a clan drenching.

I brought them in file to beg their things back,

Playing for the one that hung back; and paid them,

All but her. . .her

I forced to ride [on] a top heavy [camel saddle],

Tilting along with me by her, her tattling

Of illegal burdening of beasts, and I tickling

Her senses.10

This opening of ancient Arabia’s most famous poem exhibits the main conventions of the qasida. The qasida, which again means journey toward something, generally opens with a halt. The qasida’s speaker asks his traveling companions – also audience members, to pause with him a moment, and to survey something called the atlal– the deserted camp, a place where his tribe or consortium once lived or stayed. The poet’s depiction of a deserted camp is often full of specific place names, and references to the flora and fauna of the desert. A different qasida’s opening also involves a pause at the ruins of an old camp. Let’s hear a second example of this archetypal opening – again, the pause at the abandoned desert camp.

The camp in Rayyán’s vale is marked by relics dim

Like weather-beaten script engraved on ancient [rock].

Over this ruined scene, since it was desolate,

Whole years with secular and sacred months had flown.

In sprintg [it was blessed] by showers [beneath] starry influence shed,

And thunder-clouds bestowed a scant or copious [shower].

Pale herbs had shot up, ostriches on either slope. . .

And large-eyed wild-cows there beside the new-born calves

Reclined, while round them formed a troop [of] calves half-grown.11

The qasida, then, begins with a pause to consider the place of the poet’s past residence – almost always a desert camp. This camp, though no longer inhabited, is still a locus of rich memories, sometimes splendorous in its ruination, animated with the continued life of the desert even if the pastoral nomads who once dwelt there have departed. What comes next in a qasida is something called the naseeb, which we might call “erotic recollection” or “amatory recollection.” In the naseeb of an Arabic ode, the speaker, studying the fading remnants of a place where he used to live, remembers something else – a lost love, or alternately, a former sexual conquest. Let’s look at the naseeb of Imru al-Qays’ famous ode. Imru al-Qays, stirred to nostalgic recollections at the sight of his former camp, remembers,

Oh yes, many a fine day I’ve dallied with the. . .ladies,

and especially I call to mind a day at Dára Juljul. . .

Yes, and the day I entered the litter where Unaiza was

and she cried “Out on you! Will you make me walk on my feet?”. . .

But I said, “Ride on, and slacken the beast’s reins,

and oh, don’t drive me away from your refreshing fruit.

Many’s the pregnant woman like you, aye, and the nursing mother

I’ve night-visited, and made her forget her. . .one-year-old;

whenever he whimpered behind her, [and] she turned to him

with half her body, her other, half unshifted under me.”. . .

Many’s the fair veiled lady, whose tent few would think of seeking,

I’ve enjoyed sporting with, and not in a hurry either,

slipping past packs of watchmen to reach her, with a whole tribe

hankering after my blood, eager every man. . .to slay me. . .

I [arrived], and already she’d stripped off her garments for sleep

beside the tent-flap, all but a single flimsy slip. . .

Out I brought her, and as she stepped she trailed behind us

to cover our footprints [with] the skirt of an embroidered grown.

But when we had crossed the tribe’s enclosure, and dark about us

hung a convenient shallow intricately undulant,

I twisted her side-tresses to me, and she leaned over me. . .

she shows me a waist slender and slight as a camel’s nose-rein,

and a smooth shank like the reed of a watered, bent papyrus.12

The erotic recollections of this ode are complex and lengthy – longer than I’ve quoted here. The famous poet Imru al-Qays’ speaker remembers flirting with a pregnant woman, telling this pregnant woman that he had made love to other pregnant women and nursing mothers, and then a bit later, the speaker recollects an unspecified but illicit union with a woman that had to be carried out in secret. The illicitness and danger of the erotic unions in this poem seem to be part of the fun – the speaker is more of a Casanova than an earnest lover, and carrying on sexual relationships with married women, pregnant women, young mothers, and moreover women – perhaps of opposing clans – guarded by armed men are all objects of fond reminiscence.

Not all qasidas have drawn out erotic recollections. To give you an example of a briefer amorous reminiscence, another famous ode contains the following somewhat shorter erotic recollection.

She shows you, when you enter privily with her

and she’s secure from the eyes of the hateful foemen,

arms of a long-necked she-camel, white and youthful

fresh from the spring-pastures of sand and stone-land,

a soft breast like a casket of ivory

chastely guarded from adventurous fingers,

the flanks of a lithe, long, tender body.13

So, the naseeb, or erotic prelude of the ancient Arabic ode, is a frequent set-piece, and often the naseeb has a trace of danger. Love and sexual intercourse are always rich poetic topics, but in the ancient Arabic qasida, the poet’s sexual pursuits might also be aimed at seducing married women, or women of other tribes – even sneaking through camps to find the right tent. The poet as a participant in adulterous love affairs is something that we’ve seen before, in the elegiac couplets of Latin literature. Catullus, Ovid, and their contemporaries wrote steamy, cynical poetry about how to enjoy sex with married women, and that this would be a subject of Pre-Islamic Arabic poetry demonstrates the sophistication of literature in Arabia by the 500s CE. And while there is certainly some sexual self-aggrandizement and intertribal politics at stake in ancient Arabia’s naseeb preludes, these preludes are probably more than anything recollections of youthful misadventures – the wistful retrospections of aging poets, thinking back to their oversexed youths. [music]

The Mu’Allaqah of Imru Al-Qays, Continued

We are now a couple of sections into what might be the most famous poem in Arabic literature, again the Mu’allaqah of Imru al-Qays. So far, then, from reading this ode, we’ve learned that the qasida involves, first, a stop in some long-abandoned camp, after which follows a recollection of bygone love affairs. What comes next in the qasida varies substantially. The Arabic ode of Late Antiquity was a genre with certain formal conventions, but also one whose central section might be used for a number of different purposes. A commonplace, though, closer to the closing of the ode, is something called the rihla, a section in which the poet contemplates his long journey – both the desert journey undertaken in the poem, as well as, of course, the journey of passing from youth into maturity. Interestingly, a part of the rihla is also, not uncommonly, a praise of the poet’s camel, or horse.14 Let’s hear the rihla of Imru al-Qays’ famous ode – this is an absolutely magnificent string of lines, even in translation – here it is.Oft[en] night like a sea swarming has dropped its curtains

over me, thick with multifarious cares, to try me,

and I said to the night, when it stretched its lazy lines

followed by its fat buttocks, and heaved off its heavy breast,

“Well now, you tedious night, won’t you clear yourself off, and let

dawn shine?”. . .

Many’s the water-skin of all sorts of folk I have slung

by its strap over my shoulder, as humble as can be, and [carried] it;

many’s the valley, bare as a [donkey]’s belly, I’ve crossed,

a valley loud with the wolf howling. . .

Often I’ve been off with the morn, the birds yet asleep in their nests,

my horse short-haired, outstripping the wild game, huge-bodied,

charging, fleet-fleeing, head-foremost, headlong, all together

the match of a rugged boulder hurled from on high by the torrent,

a gay bay, sliding the saddle-felt from his back’s thwart

just as a smooth soft pebble slides off the rain cascading.

Fiery he is, for all his leanness, and when his ardour

boils in him, how he roars.15

The praises to the poet Imru al-Qays’ horse continue some time after these lines, but what you’ve just heard should give you an idea of a thematic turnabout common to the ancient Arabic qasida. In the qasida, generally, the poet halts to survey the ruins of an abandoned camp that’s being overtaken by the desert. Then the camp prompts the poet to think of his lost youth, with its love affairs, sex, and erotic misadventures. Thinking further, the poet of the qasida recollects, in a rihla, or travel contemplation, like the one that we just heard, of how long his life’s journey has been taking place, all of its hills and valleys, literally and figuratively. But seeing his horse or camel, with its youth and vitality, the poet’s mood is heartened, and his thoughts then turn from the irrecoverable past to the immediate joy of physical movement astride his mount.

What closes the qasida is a final part called the madeeh, or panegyric, or praise section. The madeeh varied according to a poet’s agenda. Some odes conclude with words of praise for a patron or desired patron. Other odes extoll the poet himself, or his tribe. Others still deprecate tribal adversaries. And a final convention to end the qasida is a literal thunderstorm. Imru al-Qays’ ode concludes with the latter. A thunderstorm might seem like an odd note for an ode to conclude on. It’s worth remembering two things, though, before we read the end of Imru al-Qays’ qasida. First, a rainy squall dumping water everywhere was, and still is, as you can imagine, a very special occurrence on the Arabian Peninsula. Second, more specifically to Imru al-Qays’ poem, we’ve watched him go from reminiscent melancholy about lost youth and bygone love affairs, to feeling weary in the course of his journey through life, to then feeling heartened by the speed and power of his horse. Concluding with a thunderstorm completes the poet’s internal journey from the landscape of poetic memory to the more enduring cadences of nature. Love affairs and individual youths might come and go, in other words, but the thunder and the rain are the sustenance of all of them. So here are some of the closing lines of Imru al-Qays’ famous poem.

Friend, do you see [the] lightning? Look, there goes its glitter

flashing like two hands now in the heaped-up, crowned stormcloud.

Brilliantly it shines – so flames the lamp of an anchorite

as he slops the oil over the twisted wick.

So with my companions I sat watching it. . .

[T]he cloud started loosing its torrent about Kutaifa

turning upon their beards the [trunks] of the tall [acacias];

over the hills of El-Kanán [it] swept its flying spray

sending the white wild goats hurtling down on all sides.

At Taimá it left not one trunk of a date-tree standing,

not a solitary fort, save those buttressed with hard rocks. . .

In the morning the topmost peak of El-Mujaimir

was a spindle’s whorl cluttered with all the scum of the torrent. . .

In the morning the songbirds all along the broad valley

quaffed the choicest of sweet wines rich with spices;

the wild beasts at evening drowned in the furthest reaches

of the wide watercourse lay like drawn bulbs of wild onion.

Narrating a great storm, as al-Qays does here, allowed a poet to pull out all the stops and describe something sacred and spectacular, after all of the vicissitudes depicted earlier in the ode. The storm in the poem, which overturns trees and slaps muck on the tallest mountain peaks, turns the world topsy turvy – it is a merciless but beautiful thing that quiets the poet’s memories, and brings him into the present moment with his companions once more. Everyone, after all, is a living well of memories, but when the present eclipses the past, via the shimmering thunder of a horse’s hooves or the bright lightning of a desert storm, new memories altogether are made. [music]

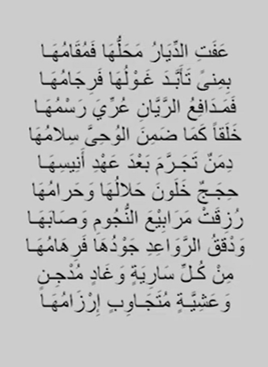

The Mu‘allaqat, or Seven Golden Odes, of Pre-Islamic Arabic Poetry

So that was the Mu’allaqah of Imru al-Qays, and also, a summary of the qasida – again ancient Arabic ode, and its various subcomponents. Let’s review. There is first the melancholy description of the desert camp, or atlal. Then, there is the naseeb, or erotic recollection, sometimes exultant, and sometimes dejected. Next comes the rihla, or meditation on the length of a journey, sometimes with praises to the poet’s horse or camel. Finally, there is the madeeh, or ending of the poem, which could take various forms. Those four, which make up the qasida, teach us a poetic form worth knowing about. As scholar Robert Irwin writes, “Not only has the qasida form dominated Arabic poetry right up to the twentieth century, but its themes and rules have also been adopted and adapted in Persian, Turkish, Hebrew, Kurdish, Urdu, and Hausa poetry.”16 While Imru al-Qays’ qasida is the most well-known of all, a select group of odes, generally understood to be seven in number, may have enjoyed special esteem even in ancient Arabian, and especially Meccan society, prior to the dawn of Islam.This group of seven odes is called the Mu‘allaqat, and we’ve just read the first one together – the Mu‘allaqah of Imru al-Qays. We have learned some vocabulary in this show so far – qasida, ode; madeeh, panegyric or praise; rihla, contemplation on a journey. Now we need to learn the word Mu‘allaqat, that’s the plural, singular Mu‘allaqah. The Mu‘allaqat are a group of seven poems – qasidas, or odes, in fact. A popular legend about the Mu‘allaqat is that these seven odes hung in the Kaaba in Mecca, which was a pilgrimage site long before Muhammad lived. More recent scholarship suggests that the legend of the hanging odes was made up later, and that the group of seven poems was first assembled by the Ummayad literary scholar Hammad al-Rawiya during the eighth century, according either to his tastes or to a lost literary tradition.17 Mu‘allaqat is generally understood to mean “hanging poems,” hence the legend that they once hung in the Kaaba, but the root of the word more likely means something precious, like jewels – something that is hung up more generally.18 What constitutes the Mu‘allaqat is a somewhat spongy group of texts – later Islamic literary history concurs that there are seven different hanging odes by seven different poets, but the exact odes mentioned can vary.

We just read the most famous of all the Mu‘allaqat, the first of the most famous seven Pre-Islamic Arabic poems. Let’s move forward, now, and look at the rest of these poems. I’m going to give you six summaries of the six qasidas most often placed after that of Imru al-Qays in the Mu‘allaqat, and though this will certainly be too much to take in all at once, the details you’re about to hear should still give you a sense of what poetry most revered by Pre-Islamic Arabic audiences, who heard poems like these at trade fairs and competitions and for entertainment at various other functions.

The Mu‘allaqah of Tarafa ibn al-‘Abd

So first, let’s look at the Mu‘allaqah, or the “hanging poem” of the poet Tarafa ibn al-‘Abd, whom we’ll just call Tarafa. Like many Pre-Islamic Arabic poets, Tarafa, active during the middle part of the 500s, allegedly lived a colorful life. Tarafa, of the northwestern Bakr tribe, was born somewhere around Bahrain in the Sasanian-dominated part of the Persian Gulf coast. Tarafa was a satirist and, perhaps, a ne’er-do-well, and though his family parted ways with him, he managed to secure himself an appointment with a Lakhmid king. Unfortunately for Tarafa, he had a loose tongue. He made lewd comments about the king’s sister, and the Lakhmid monarch sent Tarafa back to Tarafa’s tribal home of Bahrain with a letter. Tarafa couldn’t read this letter, but the letter ended up being a death sentence, and the poet, according to tradition, died while still very young. His most famous ode, a plucky self-portrait, insists that taking pleasure in earthly things – water mixed with wine, rainy days, and wiling away the hours with a woman in a tent – that these are what’s most important in life.In Tarafa’s Mu‘allaqah, or “hanging poem,” following the conventional survey of an abandoned camp, and a brief meditation on a beautiful paramour, the speaker writes that his most common cure for melancholy is riding his favorite camel. Tarafa writes, “Ah, but when grief assails me, straightaway I ride it off / mounted on my swift, lean-flanked camel, night and day racing, / sure-footed, like the planks of a litter; I urge her on / down the bright [thoroughfare].”19 Following a long and detailed laudation of his camel, Tarafa writes that he’s not really “one that skulks fearfully among the hilltops” (85), but that indeed he’s quite sociable – a frequenter of taverns and no stranger to a wine cup, where tribes assemble, and seductively dressed women sing songs. Yet the tone of Tarafa’s poem changes, as he tells his reader, “Unceasingly I tippled the wine and took my joy / unceasingly I sold and squandered my hoard and my patrimony / till all my family deserted me” (86). The poet’s knowledge of his failure (at least in his family’s eyes), however, has not led him into a life of penitent reflections. On the contrary, as Tarafa states in carpe diem lines,

But for three things, that are the joy of a young fellow,

I assure you I wouldn’t care when my deathbed visitors arrive –

first, to forestall my charming critics with a good swig

of crimson wine that foams when the water is mingled in;

second, to wheel. . .a curved-shanked steed

streaking like the wolf of the thicket you’ve startled. . .

and third, to curtail the day of showers, such an admirable season,

dallying with a ripe wench under the pole propped tent. . .

So permit me to drench my head while there’s still life in it,

for I tremble at the thought of the scant draught I’ll get when I’m dead. (86)

Death, Tarafa writes, takes every possession of the miser, and so it’s important to spend what one has and enjoy one’s life. With all this said, though, Tarafa does not want to be remembered altogether as someone “slow to doughty enterprises, swift to foul mouthing” (90), and he defends himself in regard to an incident in which he was accused of losing his cousin’s camel, and closes by insisting that he has some martial power, after all, and thus is not altogether a wastrel.

The Mu‘allaqah of Zuhayr ibn Abi Sulma

So that’s Tarafa’s ode, the second of the seven Mu’allaqat – a complex piece in which a speaker admits to enjoying life’s pleasures, and to his own shortcomings and the accusations lobbed against him, but at the same time maintains that he has some moral fiber and hardihood, as well. The third of the seven “hanging poems” or “golden odes” is the Mu‘allaqah of the poet Zuhayr ibn Abi Sulma, or just Zuhayr. Zuhayr’s canonically central ode celebrates a successful peacemaking mission. The deserted camp so central to the qasida at the outset of Zuhayr’s poem has been some time ago blackened by a major tribal war.20 However, younger scions of the war’s progenitors have taken it upon themselves to make peace, offering blood money to the members of the opposing tribe, in order to finally end the generation-long war. The poet Zuhayr marvels at the generosity of the two peacemakers, writing “Various spoils of [their] inheritance were driven forth / among the people, many young camels. . .paid in parcels by one[s] who had not sinned in the strife. . .their spears shared not on the battle field in the blood. . .yet I behold they every one paid in full the [blood money], / a thousand superadded after a thousand complete” (115, 117). Considering the incredible selflessness of this peacemaking effort, the poet Zuhayr then warns the two tribes not to fall back into bloodshed. Zuhayr writes,War is nothing else but what you’ve known and yourselves tasted.

it is not a tale told at random, a vague conjecture;

when you stir it up, it’s a hateful thing you’ve stirred up;

ravenous it is, once you whet its appetite, it bursts aflame,

then it grinds you as a millstone grinds on its cushion;

yearly it conceives, birth upon birth, and with twins for issue. (116)

The poet Zuhayr was old when he wrote these lines – according to the poem, he was 80, and he had seen enough of war, and he closes his poem with moral advice that might have come from the epistles of the aging Horace. In a series of closing lines, Zuhayr urges the poem’s reader to be honest, generous, humble, but also courageous, and to advocate for oneself when necessary.

The Mu‘allaqah of Abu aqil Labeed ibn Rabi’a

Right, so, thus far, we have been through three of the seven Mu‘allaqat, and we’ve already seen that, although the qasida had a basic structure to it, various qasidas take on substantially different forms. Some poets abandoned the naseeb, or erotic prelude, altogether, and the poems’ endings vary widely with the poet’s intentions – Imru al-Qays with a lightning storm, Tarafa with some tempered lines of self-defense, and old Zuhayr with gentle moralistic advice to make peace and not war. It’s important to remember that all of the Mu‘allaqat, again “hanging odes,” come from a relatively brief timeframe – the century between 525 to 625 CE almost certainly encompasses all of them. But in spite of the fairly brief period that produced these seven odes, the odes also came from different tribes and different regions of the Late Antique world where Arabic was spoken, and so it’s no wonder that even the first three of them that we’ve looked at so far exhibit such formal and topical diversity.The next one we’ll consider – number four out of seven – is by the poet Abu aqil Labeed ibn Rabi’a, or, commonly, Labeed. Labeed was from the hijaz, or western coastal region of the Arabian Peninsula. And Labeed’s ode has a fairly conventional qasida structure. First, we hear a haunting description an abandoned desert dwelling place – Labeed writes,

The abodes are desolate, halting-place and encampment, too. . .

naked shows their trace,

rubbed smooth, like letterings long since scored on a stony slab;

blackened [scraps] that, since the time their inhabitants tarried there,

many years have passed over. . .

So I stood and questioned that site; yet how should we question rocks

set immovable, whose speech is nothing significant? (142)

Labeed writes that the group who once lived there was long gone, “swallowed up in the shimmering haze / till they seemed as tamarisk-shrubs and boulders in [a] vale” (143), but also, that the poet Labeed still remembers a long ago love affair with a woman named Lady Nawar – a lady who had moved onto better things and was now beyond his longings.

While most qasidas linger with pride and appreciation on the poet’s camel or horse, Labeed’s Mu‘allaqah spends an unusually long time on the subject, first depicting his female camel as a older, scrawny mount that can still gallop like a gliding cloud, and then, a moment later, in something quite akin to an epic simile, like a wild cow bereaved of her calves. Scholar Reynold Nicholson, back in 1907, aptly observed that “Bedouin poetry abounds in fine studies of animal life” (78), and it’s worth pausing for a moment here to consider just how powerfully Pre-Islamic Arabic poetry can depict the world of animals. In Labeed’s canonical ode, as I said, he compares the will and fierceness of his aging camel to that of a wild cow who has just lost her calves. What follows is a beautiful and tragic portrait of a distraught animal mother – one who “unceasingly / circles about the stony waste, lowing all the while / as she seeks a half-weaned white calf,” a calf that has unfortunately been devoured by wolves. Yet the simile in Labeed’s poem doesn’t end here. Instead, the poet Labeed tells a story about this bereaved cow that’s almost a page in length.

Having lost her calf, the poor cow was stricken and irresolute. The poet Labeed writes,

All that night she wandered, the raindrops streaming upon her

in continuous flow, watering still the herb-strewn sands;

she crouched under the stem of a high-branched tree, apart

on the fringes of certain sand-hills, whose soft slopes trickled down

while the rain uninterruptedly ran down the line

of her back, on a night the clouds blotted the starlight out,

yet she shone radiantly in the face of the gathered murk

as the pearl of a diver shines when taken free from its thread;

but when the shadows dispersed, and the dawn surrounded her,

forth she went, her feet slipping upon the dripping earth. (144-5)

This is almost a mini-epic, and in Labeed’s simile, the cow, as the day lengthens after this dark night, is able to fight off two hunting dogs, killing them both. The world of animals in this qasida, then, as in other Jahili odes, is, like the human one, a world of strength and resilience, but also mourning and sorrow for past loss. The description of Labeed’s camel, with its extended simile, is the ode’s centerpiece, and in the simile’s aftermath, the poet touts some of his virtues, culminating in a summary of how he adjudicated assemblies as a diplomat in the Lakhmid court. [music]

The Mu‘allaqah of ‘Amr ibn Kulthum

That takes us through four out of ancient Arabia’s most famous seven odes. While they have varied in form and content, they have all been first person, they have each begun at an abandoned desert camp, and they have followed the same narrative arc from melancholy reminiscence to self-certainty. The fifth of the Mu’allaqat is a poem by the poet ‘Antarah ibn Shaddad, or commonly ‘Antarah. ‘Antarah is one of the most unique and celebrated writers from Pre-Islamic Arabia, and we will actually have an entire episode on him next time, so for now, we’ll skip ‘Antarah, and consider the last two “Hanging Poems.”Number six of seven is the Mu‘allaqah of the poet ‘Amr ibn Kulthum. The most famous thing ‘Amr ever did was allegedly murdering a Lakhmid king. The Lakhmid monarch ‘Amr ibn Hind has the same given name as the poet whom we’re discussing, so for clarification, we’ll call the king “ibn Hind.” King ibn Hind, to later Islamic literary historians, had a couple of strikes against him. First, he had been responsible for the death sentence of the poet Tarafa, that lover of conviviality we met as the author of the second Mu‘allaqah. Second, the Lakhmid king ibn Hind was, according to tradition, a harsh, arrogant ruler. One day, ibn Hind decided to make a show of his domination over other Arabs. He wanted to see if there were any Arabs out there whose mothers were so arrogant that they’d refuse to serve King ibn Hind’s mother. King ibn Hind learned that indeed, the poet ‘Amr had a mother named Layla who would almost certainly refuse. The Lakhmid King ibn Hind then carried out the experiment, and sure enough, the poet ‘Amr’s mother refused to wait on ibn Hind’s mother, crying out in protest. Hearing his mother’s protest, the poet ‘Amr immediately murdered the Lakhmid monarch. This regicide, if it took place, would have been in the year 569.

Whether or not the poet ‘Amr indeed killed a king in defense of his mother’s honor, the poem he left behind as a part of the Mu‘allaqat definitely shows a court poet who was himself not immune to volatile conceitedness. The poem, evidently delivered to King ibn Hind before the poet and monarch had a falling out, brags that ‘Amr’s own Taghlib tribe “take the banners white into battle / and bring them back crimson, well-saturated” (205). Militaristic self-aggrandizement is the theme of much of the poem – the speaker brags about defending allied neighbors, and about excelling in close quarters and midrange combat. ‘Amr writes that with lances and swords “we split the heads of the warriors / and slit through their necks like scythed grasses” (206).

After the poet brags about his military abilities to the Lakhmid King ibn Hind, the poet ‘Amr threatens the monarch himself, writing, “With what purpose in view, Amr bin Hind, / should we be underlings to your chosen princelet? / Threaten us then, and menace us; but gently” (206). The poet ‘Amr continues to praise nearly every aspect of his own Taghlib tribe – the justness of their rule, their clemency, their violence, their generosity, their armor, and so on, ending with the emphasis that the Taghlib tribespeople were so powerful that even a young Taghlib boy, having just stopped breastfeeding, was formidable enough to make tyrants bow down to him. The poem closes with the line, “[L]et no man act foolishly against us, or we shall exceed the folly of the foolhardiest” (209), maybe a tacit acknowledgement that a propensity for frequent violence, signaled out as a quality of the Taghlib tribe throughout the poem, was not always a good thing.

This second-to-last of the Mu‘allaqat odes really starts to showcase the variety of content in these odes. Compared to the ode of the poet Zuhayr, that measured call for peace and celebration of peacemaking, ‘Amr’s belligerent poem, which grandstands about the power and brutality of his tribe, is something completely different. The qasida, as we’ve seen from reading just a few of them, was quite an elastic genre, and the later Islamic-Arab scholars compiled and wrote about the seven revered “hanging poems” perhaps wanted a representative variety of what poets were writing in the 500s – measured pacificist works, certainly, but also martial poems; poems that extolled the joys of life on earth, poems that were more melancholy and reflective than jubilant, and poems that celebrated the domesticated and wild animal life of the pagan Arab world.

The Mu‘allaqah of al-Harith ibn Hilliza

For completion’s sake, and because these seven poems have been the taproot of Arabic poetry for a long time, let’s consider the seventh and final Mu‘allaqahh. This is the Mu‘allaqah of al-Harith ibn Hilliza, or, commonly, al-Harith. Al-Harith was, like his contemporary Tarafa, from the Bakr tribe from the region around Bahrain, and thus within the sphere of the Lakhmid kingdom’s influence. The previous poem that we read – ‘Amr ibn Kulthum’s, is a brazen, bellicose work that boasts of the power of the Taghlib tribe and spits in the face of the Lakhmid king – that client king who had the great Sasanian Persian empire at his back. Our seventh and final poem – that of al-Harith, is quite a different piece.Al-Harith’s poem was written in the wake of the War of al-Basus, which had dragged on for forty years between al-Harith’s Bakr tribe, and ‘Amr’s Taghlib tribe. In al-Harith’s poem, he carefully defends his own tribe with the Lakhmid court in mind, and he hopes for continued peace between the Bakr and Taghlib tribes. Al-Harith’s ode opens with two conventions of the qasida – he mentions the departure of a woman named Asma, and how her leave-taking brought him great sadness. Then, al-Harith writes that riding a fast camel is a distraction from heartache – a camel that trails a fine dust in its wake, such that through its own passage and the desert breeze, all traces of its footprints gradually wear away with time.

Changing topics, al-Harith writes that he’s heard his Bakr tribe has recently been slandered unjustly. The Bakr, al-Harith writes, have been slandered before, and endured much, but, like a dark mountain, “unweakened by destiny’s inexorable hammering” (223), they continue to persevere. He asks those who slander his tribe to please remember the worst moments of the long war, and that they had sworn a peace oath, and that whatever else each tribe suffered at the hands of other tribes, the Bakr and Taghlib tribes were now at peace. What follows is a convention of Pre-Islamic poetry that we haven’t yet seen – the madeeh, or panegyric – specifically, to the Lakhmid King ‘Amr ibn Hind. Al-Harith calls the Lakhmid monarch “a just monarch. . .the most perfect walking / the virtues he possesses excel all praise. . .a king who thrice has had token of our / good service, and each time the proof was decisive” (226). The ode’s closing panegyric then recollects the services that the Bakr tribe had provided for the Lakhmid king ‘Amr ibn Hind. And that takes us to the end of the seven golden odes, or “hanging poems” or Mu‘allaqat, a dense collection of works with a lot of history behind them that are some of the most influential works of Arabic literature ever written.

The Mu‘allaqat and Pre-Islamic Arabic Poetry

So, I am aware that I’ve just thrown a lot of information your way – the names of seven poets, the names of some of their friends, enemies, and associates, and some of the technical vocabulary of Arabic prosody, to boot. Thus, before we go on to the somewhat simpler task of looking at samples of a couple of other genres of Pre-Islamic Arabic poetry, let’s review what we’ve learned so far, and consider the implications.We now have a pretty good idea of what a qasida is. The qasida is an ode that in its most standard form, begins with a speaker halting at an abandoned desert camp, then engaging in an erotic reminiscence, and often includes the speaker consoling himself with thoughts of his camel or horse, and might wrap up with a panegyric or thunderstorm. There were several reasons that I wanted to take you through all seven of the Mu‘allaqat in detail as dense as that was. First, once again, these seven so-called “hanging odes” are famous, foundational poems in Arabic literary history. Second, their diversity shows the formal sophistication of the qasida, a genre that had certain conventions, but whose conventions could be ignored or amplified depending on what a poet wanted to say. And finally, Pre-Islamic poetry offers us a huge archive of information about the culture of the Arab world prior to the dawn of Islam.

We don’t have any Visigothic odes, nor Hunnic poetry, nor Vandal panegyrics. The pre-Roman history of later groups from Late Antiquity is knowable only through archaeology. Contrastingly, pagan Arabic poetry, though it was compiled and anthologized by later Islamic scholars, and we’ll talk about this in a bit – pagan Arabic poetry paints a picture of a multifarious civilization that spanned from Bedouin tents to Medinan merchant’s houses; from tribes allied with Yemeni monarchies to those allied with the client kings of the Syrian and Mesopotamian north. Pre-Islamic Arabic poetry gives us a sense of what “tribe” meant on the peninsula by the 500s – a genetically linked group, often, but also a commercially linked group, or a confederacy of groups with shared interests – groups that remembered individual and mutual history largely due to poetry itself. We learned the adage ash-shiʿr dīwān al-ʿarab, or “Poetry is the compendium of the Arabs” at the beginning of this episode, and just from learning a bit about the famous hanging odes, you already have an idea of how much information early Arabic poetry contains – personal recollections, tribal interactions, political stuff at the level of the monarchy, ecology, geography, wisdom, peace, war, and more.

Those hanging odes – the Mu‘allaqat – show pagan Arabic verse being leveraged to do all sorts of things – to recall past love affairs, to cherish the unique biomes of specific regions of the peninsula, to mourn heartbreaks and celebrate sexual conquests, to sue for peace and threaten war, to muse about the human condition and bloviate about one’s sword and tribe, to mourn the loss of youth and celebrate the wisdom of age, and to sing the praises of some absolutely tremendous sounding camels. If the Mu‘allaqat were all we possessed of Arabic poetry written before Islam, we would still have a vibrant and impressive body of writing, but the Mu‘allaqat are only the tip of the iceberg. So in the remainder of this episode, before we get into the thorny issue of how Pre-Islamic Arabic poetry was curated and compiled, let’s learn about two more genres besides the qasida. We will begin with the sa’alik poem – the wanderer, or vagabond poem, a dark, beautiful genre that was in all likelihood one of the greatest original productions of the Arabic language prior to Muhammad. [music]

The Sa’alik Poem and the Lamiyyat al-Arab

Not everyone in ancient Arabia was an accepted member of a tribe. Most famously, the Prophet Muhammad, orphaned at birth, spent the first four decades of his life going from being in the care of a Bedouin foster mother to being a respected trading agent with a family and financial security – all before his first revelation. But beyond Muhammad, a number of other sixth-century Arabs whose writings have survived fell through the cracks of tribal society, due to things like exiles, or kidnappings, or enslavements, or unfavorable births. In pagan Arabic poetry, such individuals are tragic, romantic figures – outlaws, or noble brigands – dark heroes often with vengeance on their minds. We’ll spend an entire episode next time with ‘Antarah ibn Shaddad, whose half-caste parentage led him to both heartbreak and vengeance, and who took, with poetry and the sword, what was unavailable to him by more conventional means.So the word sa‘alik means “one who follows the road” – and sa‘alik poetry might be described as outcast poetry or vagabond poetry.21 In all of the qasidas we just read, there is an element of the lone wanderer – the qasida begins with a journey through individual memories and then often includes a description of traveling astride a horse or camel. For the su‘luk, or vagabond poet, however, rootless isolation is more the central point – sa’alik speakers are misanthropic, shunned by society and in turn shunning it back. So, let’s look at what’s perhaps the most famous sa’alik poem in pagan Arabic literature – this one is called the Lamiyyatal-Arab. Structurally, a Lamiyyat is a poem in which all lines end with the Arabic letter “lam,” basically the English “L” sound. There are a number of these poems, but the Lamiyyat al-Arab, which I will just call the Lamiyyat henceforth, is the most famous.

The Lamiyyat is both a sa’alik – again “vagabond” poem, but it’s also something called a fakhr, or “boast” poem. Multiple genres, naturally, coexisted in early Arabic poetry, and it makes sense that a lone wanderer would have a bit of bluster in order to justify his isolationism. The author of the Lamiyyat is one of the more famous poets of Pre-Islamic Arabia – a man named as-Shanfara al-Azdi. As-Shanfara was from the south of the peninsula, likely modern-day Yemen, and his name means “the man with thick lips,” or “he with large lips.” The most famous thing about as-Shanfara, at least in later Islamic literary history, is that as-Shanfara had a bone to pick with a certain tribe – either a tribe that had kidnapped him as a child, or his own tribe, depending on the story. Here’s a version of as-Shanfara’s story from an early English translator of Arabic poetry.

[I]t is said that [as-Shanfara] was captured when a child from his tribe by the. . .Salaman [tribe], and brought up among them: he did not learn his origin until he had grown up, when he vowed vengeance against his captors, and returned to his own tribe. His oath was that he would slay a hundred men of [the] Salaman [tribe]; he slew ninety-eight, when an ambush of his enemies succeeded in taking him prisoner. In the struggle one of his hands was hewn off by a sword stroke, and, taking it in the other, he flung it in the face of a man of [the] Salaman [tribe] and killed him, thus making ninety-nine. Then [as-Shanfara] was overpowered and slain, with one [kill] still wanting to make up his number. As his skull lay bleaching on the ground, a man of his enemies passed by that way and kicked it with his foot; a splinter of bone entered his foot, the wound mortified, and he died, thus completing the hundred.22

And that is an objectively awesome story. In another version, as-Shanfara returns to his own Azd tribe, but, when a young woman of the Azd rejects him, he realizes that his being raised by a foreign tribe has made him half-caste in his own tribe, and he vows revenge on his own tribe.

Whatever the reason for the poet as-Shanfara’s bitter isolation, his most famous poem, again the Lamiyyat, emphasizes that the poet prefers solitude to life in a tribe; indeed, that living in the desert wilderness has made him feel more kinship with the hardy animals of the badlands than he does with human society. Let’s take a look at the Lamiyyat in detail now. The translation we’ll use will be Warren Treadgold’s, published in the Journal of Arabic Literature in 1975. Let me note ahead of time that you’re not going to hear this whole translation, which is both lengthy and copyrighted – I’ll try to quote some representative sections, instead. The Lamiyyat of as-Shanfara begins with these words:

Sons of my mother. . .I choose other company than you

I have some nearer kin than you: swift wolf,

Smooth-coated leopard, jackal with long hair.

With them, entrusted secrets are not told;

Thieves are not shunned, whatever they may dare.

They are all proud and brave, but when [you] see

The day’s first quarry, I am braver than they.23

The opening of the Lamiyyat, then, depicts a man alone – so alone, in fact, that he feels himself sovereign over even his animal neighbors in terms of bravery. Human friends, as-Shanfara writes a moment later, can be ingrates with no appeal to them, and such individuals, for the courageous loner, could be dispatched with a naked blade or a twanging bow.

In the desert, writes as-Shanfara, he is not thirsty. He is no married man, asking for advice from a wife. He is no layabout, spending his days and nights applying perfume and mascara. Far from it, writes as-Shanfara – he goes fearlessly through the dark, barefoot, and “when hard flint-stone meets my calloused feet, / Up from it sparks of fire and splinters spray” (20). What an awesome line, by the way. He has mastered hunger, he says, eating dust, his innards cinched as though with a weaver’s threads. In an epic simile, as-Shanfara envisions himself as a “lean gray wolf” (20), padding through the desert wind until noon. Comparing himself, and perhaps other desert brigands, to wolves, as-Shanfara writes,

When food escapes [a wolf] where he looks for it,

He howls; his comrades answer, hungry ones,

Thin-bellied, gray of face, like arrow-shafts. . .

They, gaping, wide mouthed, look as if their jaws

Were all stick-splinters, as they scowl and bite.

He howls, and they howl in the desert, like

Mourners, bereaved of sons, upon a height. . .

He grieves, and they grieve; he stops, and they stop;

For patience, if grief does no good, is best.

He goes, and they go, hurrying, and each

Is brave, despite his pain from what he hides. (20-1)

So this portrait of the sa’alik, or outcast, shows the vagabond as part of a fraternity – a fraternity of underfed wolves, forlorn, gaunt, but also crafty and enduring – creatures that may not keep close company, but that also derive some sense of camaraderie through knowledge of one another’s existence.

As-Shanfara goes on to say that he is swift – the leader of running grouses dashing toward the rim of a well to fill themselves with water. As much as he has been an affiliate of desert wolves and grouses, the speaker of as-Shanfara’s poem also says he remembers being a hunted man – pursued relentlessly by foes who drew straws to see who would get to kill him, and that the memories of such times still haunt him – that “He lives with cares that still keep coming back, / Severe as [deadly] fever” (21).

The Lamiyyat does not depict the poet as-Shanfara as a handsome man. He states “I lean upon a bony arm. . .Thus, though you see me, like the snake, Sand’s child, / Sun-blistered, ill-clad, sore, and shoeless, still / I have endurance, and I wear its shirt” (22). Such straightened circumstances, however, the poet tells us, bring with them honesty. He wants nothing. His mind is clear with the severe exigencies of the desert. He neither gossips, nor lies, nor traffics in any sort of foolishness. And in his austere clarity, as-Shanfara adds, moving onto a new topic, he is a ruthless foe.

The poem’s speaker growls, “I go in dark and drizzle, and my friends / Are hunger, shivers, shuddering, and fright. / I widow wives and orphan children, then / I go as I have come, in darker night” (22). In the wake of his nocturnal raids, he says, spooked tribespeople report that dogs have growled at the coming of something – a demon, perhaps, but certainly not a man. The closing eight lines of the Lamiyyat reprise much of what the poem has already said – let’s hear them in their entirety, because they’re great:

One day of [hot summer], whose vapors shine,

Whose asps, on his hot earth, contort their shape,

I set my face against him, with no veil

Or covering, except a ragged cape

And long hair, from both sides of which the wind,

When raging, makes my uncombed mane to blow,

Far from the touch of oil and purge of lice,

With matted dirt, last washed a year ago,

As for the dried-up desert, like a shield,

I cross on foot its seldom-traveled sand.

I scan its start and end when I have climbed

A height, and sometimes crouch and sometimes stand.

The yellow she-goats graze about me, like

Maidens whom trailing dresses beautify.

At dusk, they stand around me, like a ram,

White-footed, long-horned, climbing, dwelling high. (22-3)

So there is a close summary of the most famous sa’alik, or outlaw poem, from Pre-Islamic Arabic poetry. The sa’alik poets, scorned by their parent societies, return the scorn, living lives of both pride and hardship in the desert hinterlands, and raiding settled societies whenever they need to. We’ll come back to sa’alik poetry in our next program, but even having seen just one vagabond poem, we can still make some observations about this genre of Pre-Islamic poetry.

As-Shanfara other sa’alik poets from this early period of Arabic literature were at work mostly during the 500s. By this time, writings about desert hermits had been in fashion for several centuries in the Christian world, beginning with the legends of Paul of Thebes and Saint Anthony, popularized particularly between 350 and 400 in the Roman Empire. Christian hermits, like sa’alik poets, lived in the arid wilderness, ate and drank very little, and were revered by those who read about them as exemplars of ascetic fortitude. Some Christian hermits, like Arab sa’alik poets, went to live in the desert due to persecution, but by the year 300, especially in Egypt and Syria, communes of monks in the desert were the roots of the Christian monastic movement. Latin Christendom’s slow embrace of clerical chastity and the severer doctrines of Augustine’s generation were influenced by this cultural fascination with bearded desert dwellers who scorned the finery of civilization.

Naturally, Christian monks lived in the dry regions of Pre-Islamic Arabia, as well. One of them, a monk named Bahira, was, according to some Islamic traditions, the first person to hail young Muhammad as a prophet in the influential biography of the eighth-century Muslim historian Ibn Ishaq. But Christian desert monks, although they were also slender eremites wearing ratty clothes and sporting unkempt hair, are rather different figures than the vagabonds of late antique Arabic poetry. Christian eremitic literature is full of temptation scenes, and what Christian desert hermits swear off in terms of earthly pleasures is promised to them in heavenly rewards. Conversely, Arab sa’alik poets, in exchange for relinquishing civilization, only receive grim fortitude and self-reliance – at best, a fellowship with desert animals; at worst, a joyless hand-to-mouth existence that terminates only with death. There are moments in sa’alik poetry that sound a bit like Christian eremitic literature. As-Shanfara tells us in the poem that we just read, “I am sometimes poor, yet I am rich: / The exile has true wealth, for he is free” (22), and Christianity absolutely adored the literary figure of paradox, as it’s used here. But as-Shanfara’s compensation for living among the scorched rocks and stinging winds is not eventual heavenly pleasure, but instead, the cold clarity of animal survival – the knowledge that exile and isolation have made him stronger, and not weaker. Ancient pagan literature, whichever continent engendered it, did not yet have our present addiction to happy endings. [music]

Pre-Islamic Arabic Satire: Tarafa’s Poem on ‘Amr ibn-Hind

So far in this program, we’ve learned about the qasida, the ode of the desert wanderer, reflecting on his past and other topics, and the sa’alik genre – the vagabond poem. What you’ve heard up to this point sounds like pretty serious stuff – the grave meditations of solitary men astride camels, looking out into the sere countryside and voicing eloquent truisms on life. I also wanted to reserve a place in this program, however, for the genre of hija, or satire. Much of what we know about Jahili satire comes from a book written much later, during the 800s. This book is the Hamasah of Abu Tammam, an anthology that contains an entire chapter dedicated to satirical poetry.Satire, as in Periclean Athens, or republican Rome, or many advanced democracies today – satire works best in non-autocratic, non-theocratic societies precisely like sixth-century Arabia. In a patchwork of tribal groups, cities and towns that gather for major pilgrimages and trade fairs, satire can call out demagogues, liars, and scumbags, decry unfair trade and commercial practices, deflate silly cultural and theological fads, and generally clear the air between groups at loggerheads with one another, sometimes, ending feuds with cathartic bouts of mutual insults, rather than swords. At trade fairs in places like sixth-century Mecca, tribes might fight proxy wars via skilled satirists, and poets themselves might engage in something like slam poetry contests or rap battles, enjoying acclaim, applause, and tips and prizes for their efforts.

One of the most famous instances of satire in pagan Arabic poetry is something we’ve already heard about, albeit briefly, earlier in this episode. The poet Tarafa worked up in the city of al-Hirah, today Kufa, in Iraq, then as now a lovely part of the country, watered by the Euphrates. Tarafa was the court poet of the Lakhmid ruler ‘Amr ibn-Hind, who served the Sasanian empire as a client king from 554-569. As we learned earlier, Tarafa was a proud idler with a bit of a loose tongue, though his Mu‘allaqah also depicts him as a person with some strength and moral fiber. Tarafa evidently got into terminal trouble with the Lakhmid king when he said the following about the king’s sister: “Ah yes, the gazelle with the glittering / ear-rings gave me her company, / and but for the king sitting with us / she’d have pressed her mouth against mine.”24 Whether or not Tarafa spoke these words at an inopportune moment – it seems like an awfully unwise thing to say, even for a sybarite court poet – some verses have come down to us from the poet Tarafa that are sharply satirical of his Lakhmid employer.

Tarafa wrote of the Lakhmid king ‘Amr ibn-Hind,

A marvel is. . .Amr, he and his tyranny

. . .Amr sought to wrong me, quite outrageously.

There’s no good in him, bar that he’s very rich

and his flanks, when he stands up, are very slim.

All the women of the tribe go waltzing round him

crying, “A palm-tree, straight from the [valley].”

He boozes twice daily, and four times every night

so that his belly’s become quite mottled and swollen.

He boozes till the milk of it drowns his heart;

. . .The armor droops on him like a willow-branch –

see how puffed he is, ugly crimson his paunch’s creases!25

Elsewhere, the poet Tarafa allegedly wrote that ‘Amr was so useless that the Lakhmid kingdom would be better off with a nice ewe – or a female sheep with two lambs suckling its milky teats. As we learned earlier, due to the poet Tarafa’s infractions against King ‘Amr ibn Hind, Tarafa was eventually sent back home with a death sentence – a severe punishment, obviously, but the satirical verses that Tarafa lobbed at his employer were, as you just heard, pretty vicious. It’s possible that the Lakhmid king didn’t mind a bit of healthy drubbing, but that Tarafa overstepped the bounds of propriety, but that’s just speculation.

What is more certain is that pagan Arabia, like pre-Christian Greece and Rome, had a healthy, homegrown satirical culture, in which brazen bards, acutely conscious of their unique social power, could say controversial things in a public forum – insulting a tribe, deprecating a king, decrying a tycoon, or just riffing gross, bawdy verses with a poetic peer.