Episode 119: The Qur’an, Part 3: Origins

The Qur’an has deep roots in the Bible and in the unique religious climate of Late Antique Mecca. Learn about its many references to the Bible and ancient Arabian religion in this episode.

Episode 119: The Qur’an, Part 3: Origins

Gold Sponsors

David Love

Andy Olson

Andy Qualls

Bill Harris

Christophe Mandy

Jeremy Hanks

Laurent Callot

Maddao

ml cohen

Nate Stevens

Olga Gologan

Steve baldwin

Silver Sponsors

Alexander D Silver

Boaz Munro

Charlie Wilson

Danny Sherrard

David

Devri K Owen

Ellen Ivens

Evasive Species

Hannah

Jennifer Deegan

John Weretka

Jonathan Thomas

Lauris van Rijn

Michael Davis

Michael Sanchez

Mike Roach

Oscar Lamont

rebye

Susan Hall

Top Clean

Sponsors

Carl-Henrik Naucler

Stephen Connelly

Angela Rebrec

Chris Guest

A Chowdhury

A. Jesse Jiryu Davis

Aaron Burda

Abdul the Magnificent

Aksel Gundersen Kolsung

Andrew Dunn

Anthony Tumbarello

Ariela Kilinsky

Arvind Subramanian

Basak Balkan

Bendta Schroeder

Benjamin Bartemes

Bob Tronson

Brian Conn

Carl Silva

Charles Hayes

Chief Brody

Chris Auriemma

Chris Brademeyer

Chris Ritter

Chris Tanzola

Christopher Centamore

Chuck

Cody Moore

Daniel Stipe

David Macher

David Stewart

Denim Wizard

Doug Sovde

Earl Killian

Elijah Peterson

Eliza Turner

Elizabeth Lowe

Eric McDowell

Erik Trewitt

Francine

FuzzyKittens

Garlonga

Glenn McQuaig

J.W. Uijting

Jacob Elster

Jason Davidoff

JD Mal

Jill Palethorpe

Joan Harrington

joanna jansen

Joe Purden

John Barch

john kabasakalis

John-Daniel Encel

Jonah Newman

Jonathan Whitmore

Jonathon Lance

Joran Tibor

Joseph Flynn

Joseph Maltby

Joshua Edson

Joshua Hardy

Julius Barbanel

Kathrin Lichtenberg

Kathy Chapman

Kyle Pustola

Lat Resnik

Laura Ormsby

Le Tran-Thi

Leonardo Betzler

Maria Anna Karga

Marieke Knol

Mark Griggs

MarkV

Matt Edwards

Matt Hamblen

Maury K Kemper

Michael

Mike Beard

Mike Sharland

Mike White

Morten Rasmussen

Mr Jim

Nassef Perdomo

Nick

noah brody

Oli Pate

Oliver

Pat

Paul Camp

Pete Parker

pfschmywngzt

Richard Greydanus

Riley Bahre

Robert Auers

De Sulis Minerva

Rosa

Ryan Shaffer

Ryan Walsh

Ryan Walsh

Shaun

Shaun Walbridge

Sherry B

Sonya Andrews

stacy steiner

Steven Laden

Stijn van Dooren

SUSAN ANGLES

susan butterick

Ted Humphrey

The Curator

Thomas Leech

Thomas Liekens

Thomas Skousen

Tim Rosolino

Tobias Weber

Tom Wilson

Torakoro

Trey Allen

Troy

Valentina Tondato Da Ruos

vika

Vincent

William Coughlin

Xylem

Zak Gillman

Mecca and Medina were not isolated places as of the year of Muhammad’s birth in roughly 570. 570 CE, in fact, marked the precise 500-year anniversary of the destruction of the Second Temple of Jerusalem in 70 CE by the Roman emperor Titus. For 500 years after the destruction of the Second Temple, diasporic Jewish populations had been settling along the back of the Arabian boot, and forming Arabic speaking Jewish tribes such as the ones Muhammad knew and worked with over the course of his life. The Hijaz, or western coast of Arabia, which one scholar calls the “Eurasian hinge,” was the great geographical, commercial, and theological axis of Late Antiquity.1 Arid though it may have been, it was anything but isolated, and by the lifetime of Muhammad, at least five centuries of Jews and Christians had made their homes there.

Fleeing Roman persecutions over the first few centuries CE, Jews left the Roman province of Judaea for safer and more tolerant regions in the east, like Arabia. Just so, escaping various Roman and Sasanian persecutions, different populations of Christians settled in Arabia, as well. By the 500s and 600s, the Hijaz was speckled with various forms of Syriac Christians – Melkites, Jacobites, and Nestorians, along with Copts, and Armenian and Ethiopian Christians, as well.2 The western peninsula, by the year 500, was also home to Jewish Christian sects, like the Nazarenes, Ebionites, and Elkasaites, in addition to Manichaeans driven out of the Roman Empire over the centuries. To put it simply, Muhammad grew up in a city in which pagan polytheists made offerings to idols. He also grew up in a city home to many varieties of Jews, Christians, Jewish Christians, and para-Christian ideologies. Judaism and Christianity, then, were at least five hundred years deep in Mecca when the Prophet grew up there. The city was also home to polytheistic pagan cults involving the worship of goddesses like Allat, Manat, and al-‘Uzza. The mixture of pagan Arabian religion with Judaism in Christianity created what scholar Sidney Griffith calls a “nondenominational Abrahamic monotheism,” in the Hijaz. In Mecca, and its sister settlements up and down the Hijazi caravan routes, Biblical figures like Abraham, Noah, Jesus, and Mary were revered, folkloric figures whose legends intermingled with stories about jinn and witches.3 As with so many other places and times in Late Antiquity, paganism and Abrahamic religion were not oil and water. They mixed freely, as human cultural traditions generally do. And it’s time for us to talk about that mixture, and how the Qur’an demonstrates it.

I want to begin this program on the historical origins of the Qur’an by talking about the Qur’an’s indigenous Arabian roots. The Qur’an is a thoroughly Abrahamic book. But the surahs also frequently address the pagan world into which Islam most immediately emerged during its first decade of existence in Mecca. What do we know about polytheism in pre-Islamic Arabia, and what does the Qur’an say about it? Mecca’s polytheist oligarchy was Islam’s greatest enemy in the religion’s early years, but did polytheism influence the Qur’an, and the way that it describes God? Let’s open up the Qur’an on one side of our desk, and some works of history, archaeology, and Islamic studies scholarship on the other, and try to answer these questions. Unless otherwise noted, quotes from the Qur’an in this episode will come from the M.A.S. Abdel Haleem translation, published by Oxford World’s Classics in 2010. [music]

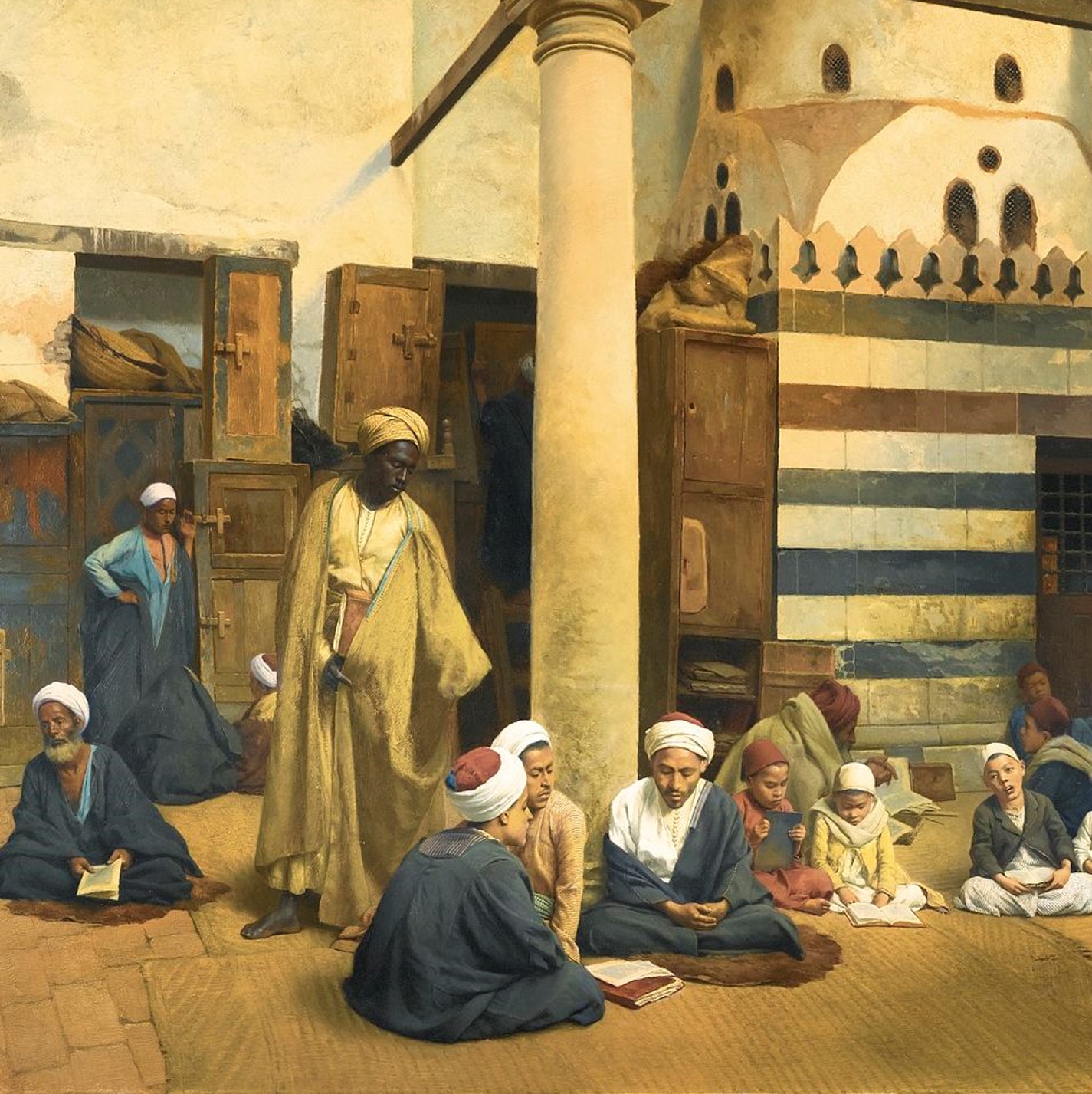

Arabian Polytheism Prior to the Qur’an

One of the main things that we’ve learned about monotheist historiography in our podcast is that monotheists do not tend to tell the truth about polytheists. Religious historians, after all, are not historians of religion. The narrators of the Torah, and the Deuteronomistic history of the Bible castigate the idol-worshipping Israelites and strangers alike in and around the periphery of Jerusalem, and forever after, in later rabbinical literature, in Christian patristic texts, and in Islamic works of history produced centuries after Muhammad lived, pagan polytheism is imagined as diabolical, sensual, riotous, and perverse – a misguided leadup to the monotheist present of little interest other than being an odious and prurient example of what not to do. When the Qur’an was developing between 610 and 632, the first generations of Muslims were fighting, both ideologically and militarily, against a polytheist hegemony in Mecca whose financial interests were enmeshed in the city’s spiritual status quo. We would not expect, then, the Qur’an to have very many kind words about polytheism in Arabia, and indeed it does not.Islamic sources on the indigenous polytheistic religions of the Hijaz, then, including the Qur’an, tend to be condemnatory in tone and not particularly rich in informational content. For hard evidence on Arabian polytheism, we have a fair amount of graffiti and inscriptions at worship sites and tombs, and a few early books from Islamic historians that, while being serviceable sources of information, were never intended as documentary works of religious history. Let’s start with archaeology.

Dry climates are not ideal for supporting large human populations, but they are often wonderlands for the preservation of ancient historical sites. Pre-Islamic Arabian tombs, like the ones up in the Nabataean city of Petra, along with simple cairns scattered throughout Arabia, contain remains buried alongside grave goods, like so many other places in the ancient world. Pervasively, as Pre-Islamic Arabic poetry also suggests, ancient Arabs had beliefs in some sort of afterlife, where possessions that typified who they were could still continue to serve them after they died. Hundreds of inscriptions and graffiti scattered throughout Arabia attest to the unsurprising fact that a vast number of deities were worshipped throughout the peninsula, that they were revered patrons of tribes and guardians of unique physical locations, and that their devotees provided them with prayers and offerings as they sought security, fresh water, fertility, and the promise of good health.4 Drop generic humans anywhere, it seems, and we will gradually congregate around pretty river bends and caves, groves and mountain vistas, and deities will emerge from the stories that we invent there.

The names of a number of these deities have come forward through time, both in the Qur’an, and in early works of Islamic history. Most famously, many of Muhammad’s Meccan contemporaries worshipped a principal deity named Allah – the word in Arabic simply means “God,” and Allah was a supreme deity and provider figure to the Meccans and others who worshipped him. Allah had three daughters, and their names were Allat, Manat, and al-‘Uzza. This theological configuration – a principal or henotheistic deity with three daughters, is the same as the deity Ba’al, who also had three daughters, and was associated with the ancient city of Ugarit. In addition to God’s daughters, the Qur’an also mentions five additional gods, “Waad, Suwa‘, Yaguth, Ya’uq, and Nasr” though the Qur’an only tells us that these deities have “led many astray” (71:24).5 The god Hubal, though mentioned in early Islamic biographies of Muhammad, doesn’t appear in the Qur’an, and nor do three other Meccan deities, Manaf, Isaf, and Na’ila.

For information on these deities, apart from the Qur’an, our richest source is the Kitab al-Asnam, or Book of Idols, written by the historian Hisham ibn al-Kalbi some time before the author’s death in about 819. Al-Kalbi’s Book of Idols is a short catalog of pre-Islamic gods and goddesses in Arabia. The Book of Idols, as the name probably implies, has an overall condemnatory attitude toward the bygone gods and goddesses of Arabia, but nonetheless it’s a useful sourcebook on indigenous Arab religions prior to the life of Muhammad. Let’s take a quick look at Al-Kalbi’s Book of Idols, probably not the most reliable book, as it takes monotheism’s traditionally condemnatory attitude toward the polytheistic past, but still, a useful jumping off point.

The Book of Idols describes the pre-Islamic Kaaba as a place profuse with statues of different gods – statues which had come from all over the place. One of these gods was named Hubal. According to the biographers ibn Ishaq and al-Tabari, Muhammad’s father was nearly sacrificed to the deity Hubal.6 The historian al-Kalbi recorded that a statue of this god, made of red agate, came to the Kaaba and was first revered by an ancestor of Muhammad. Al-Kalbi writes that the statue “stood inside the Ka’bah. In front of it were seven divination arrows.”7 These divination arrows, with words written on them and functioning like the drawing of straws, were used to determine the parentage of newborns, and to make decisions related to the departed, marriage, and journeys. While Hubal, mentioned in early Islamic biographies related to Muhammad, seems to have been a fairly important idol in the Kaaba, there were numerous others.

Among Mecca’s pagan deities were a pair named Isaf and Na’ilah. The early historian al-Kalbi tells us that Isaf and Na’ilah, a pair of young unmarried lovers from Yemen,

set out to perform the pilgrimage. Upon their arrival in Mecca they entered the Ka’bah. Taking advantage of the absence of anyone else and of the privacy of the Sacred House, Isaf committed adultery with her in the sanctuary. Thereupon they were transformed into stone. . .They were then taken out and placed in their respective places. Later on, the. . .Quraysh, as well as everyone who came on pilgrimage to the Sacred House, worshipped them. (7)

It’s a pretty weird story, and maybe it’s intended as such. Illicit sex in a sacred place, though it turned two young lovers to stone, presumably due to the primordial Abrahamic powers of the Kaaba, also leads to their deification by the Meccans in al-Kalbi’s account.

There are a number of other prominent Meccan gods mentioned in the Book of Idols, and in fact, the book begins with those deities listed Qur’an, “Waad, Suwa‘, Yaguth, Ya’uq, and Nasr.” The Book of Idols, again set down very roughly around 800, tells us that the deity Waad was the main god of one the larger tribal groups in Arabia, but nothing else. As for Yaguth, the book offers something similar, attesting that a Yemeni tribe called the Jurash worshipped Yaguth, and a different tribe still revered the god Ya’uq. Like the other minor deities mentioned in the Qur’an, the god Nasr, in al-Kalbi’s Book of Idols, is only described as being the patron deity of the Himyarites prior to about 400 CE. These gods are little more than names in the Qur’an and the Book of Idols. They’re a set of interchangeable figures whose tribal provenances were more interesting than their actual attributes. Though ancient Arabian deities like the Yemeni god Yaguth are mostly lost to history, when we read the Qur’an and Book of Idols, we can intuit that many tribes and coalitions of tribes had religion as a force that helped unify them. The sacred grounds around the Kaaba, during the life of Muhammad, were allegedly home to sculptures of hundreds of deities. If the rest of the ancient world is any clue, the sculptures around the Kaaba were probably totems to tribes and clans who visited the city from time to time, or made donations to the Kaaba’s maintenance, in much the same way that the ancient Greek pilgrimage sites of Delphi and Eleusis were studded with hundreds of statues and small buildings commissioned by visiting donors.

To turn to the subject of pre-Islamic Arabian deities, we should talk a bit more about Allah and his daughters Allat, Manat, and al-‘Uzza. Between monotheism and polytheism is henotheism, the belief in numerous gods but the reverence of one of them in particular. Pre-Islamic Mecca, saturated with so much monotheism from centuries of Jewish and Christian presence there, seems to have been tending toward something like monotheism prior to Muhammad. Linguistically, the name Allah is likely derived from the Aramaic ’Alāhā and Hebrew ’Ĕlōah. The Arabic name for God becomes extant in the historical record from around the first century CE. Around this time, again years from 1-100 CE, the ancient capital of the inland Kindah Kingdom of Arabia, the consonantal root – what we would call LH – of the name Allah begins to appear in inscriptions that seem to indicate the name of a specific deity, rather than a generic word for God.8 In Pre-Islamic Arabic poetry, the high deity Allah is described as a bringer of rain, an architect of human fate, and a god of justice.9 The Arabian roots of the Qur’an, then, included what scholar Nicolai Sinai aptly calls “pagan monotheism” – the worship of a multifaceted and universal deity with a semitically rooted monotheistic name who had been subsuming the fiefdoms of other deities for five hundred years prior to Muhammad’s birth.10 What we’ve called “monotheization” in previous episodes was a long process, and all of the Abrahamic scriptures are snapshots of it taking place.

A relief of the goddess Allat (and possibly Manat and al-Uzza), originally fond in Hatra, in the northern part of present-day Iraq, and dated from 1-300 CE. Photo by Osama Shukir Muhammad Amin. In the picture, Allat (in the middle) has a helmet and wears a gorgon on her breastplate like the Greek Athena.

The pre-Islamic goddess Manat, the Book of Idols explains, had a seaside shrine between Mecca and Medina, and “All the Arabs used to venerate her and sacrifice before her. . .and bring. . .her their offerings” (14), especially the ‘Aws and Khazraj tribes resident in the city of Medina when the Prophet immigrated there. Arabs, Al-Kalbi writes, used to go to the shrine of Manat as part of the pilgrimage circuit to Mecca. In the year 630, though, when Muhammad marched on Mecca, about five nights out from Medina he sent his son-in-law ‘Ali to destroy Manat’s shrine, which ‘Ali did, looting some ancient swords from the shrine.

Allah had a final daughter, other than Allat and Manat, and his third daughter, al-‘Uzza, has a long and detailed entry in the Book of Idols, in contrast to every single other deity’s, seems to indicate that al-‘Uzza was once particularly important. Al-‘Uzza, the book explains, was a newer deity, but she was “the greatest idol among the Quraysh. They used to journey to her, offer gifts unto her, and seek her favours through sacrifice” (18). Al-‘Uzza had a shrine down the Hijazi road down to Ta’if, and according to al-Kalbi, her name was chanted by those who circumambulated the Kaaba (18). The Book of Idols states that the Qur’an’s denunciation of al-‘Uzza “proved very hard upon the Quraysh” (20), and includes a sort of ghost story about the destruction of al-‘Uzza’s sacred site. In this story, Muhammad’s companion Khalid ibn al-Walid, recently converted to Islam, was sent to a valley called Nakhlah, where three trees stood, to destroy the shrine of al-‘Uzza. Khalid proceeded with the destruction of the site. He saw nothing after cutting down the first tree in al-‘Uzza’s valley. He saw nothing after cutting down the second tree. But then, Khalid was shocked to see the goddess al-‘Uzza, herself, in the form of “an Abyssinian woman with disheveled hair and her hands placed on her shoulder[s], gnashing and grating her teeth” (21). The pagan shrine’s guardian sent the embodied deity to kill Khalid, but instead Khalid chopped her head in half, and she crumbled to ashes, after which Khalid killed the shrine’s guardian, as well.

And just as the Book of Idols reports the destruction of the worship sites of Allah’s daughters Allat, Manat, and al-‘Uzza, the section on these three concludes with this terse story about the end of idol worship at the Kaaba: “When, on the day he conquered Mecca, [Muhammad] appeared before the Ka’bah, he found the idols arrayed around it. Thereupon he started to pierce their eyes with the point of his arrow saying ‘Truth is come and falsehood is vanished. . .’ [Muhammad] then ordered that they be knocked down, after which they were taken out and burned” (23). This is a story we’ve heard before, and really, the general purport of al-Kalbi’s Book of Idols. As al-Kalbi puts it, “The Arabs were passionately fond of worshipping idols” (24), but Islam emphatically put an end to the messy and ungovernable epoch of idol worship on the peninsula.

So that’s a quick tour of the basic source materials on pagan religion in the city of Mecca in about the year 600. There’s plenty more to say on this subject, and plenty of scholarship, but the main focus of this podcast episode is the Qur’an, and its attitude toward the polytheistic atmosphere of western Arabia during the early 600s. Accordingly, let’s open up the Qur’an for a little while and explore its verses relating to pagan polytheism. [music]

The Qur’an’s mushrikun: “Associators,” not “Idolaters”

In the Qur’an, pagan polytheists are often called mushrikun. These polytheists are contrasted with the ahl al-kitab, or the “people of the book,” meaning Jews and Christians, and in the Qur’an’s hierarchy of religious practitioners, the mushrikun are the lowest of all. However, there is a complexity to the way that the Qur’an discusses the mushrikun – the polytheists, or idolaters, and this complexity is easy to miss for those of us who read the book in English. Saint Augustine, in the City of God, writes about pagans with vicious and wholesale dismissal, either confidently discounting them as heretics or smugly intimating that their cultic practices are little different than orgies.11 The Qur’an is more nuanced. At times, as Saint Augustine does, the Qur’an takes a snarling and dour stance toward polytheists. At other times, though, using special terminology pertinent to the specific religious climate of Mecca in the early seventh century, the Qur’an makes specific doctrinal criticisms of the evolving religious climate of Mecca, rather than blanket dismissals of the city’s polytheists.The Qur’an tells Muslims, in regards to the Muslim-pagan treaty of al-Hudaybiya of 628, “As for those idolaters who have honored the treaty you [believers] made with them and who have not supported anyone against you: fulfil your agreement with them to the end of their term” (9:4). The overall meaning here is simple – let’s honor our treaty with the idolaters, and keep up our end of the deal. But the terminology is fascinating. In the verse we just heard, the Qur’an uses the words “those idolaters,” or alternately “the polytheists,” and the Arabic original here is al-mushrikin. This is a fairly important Qur’anic word, and mushrikun, though commonly translated as “idolaters,” has a more complex meaning in the original Arabic. The Qur’anic word shirk, that’s s-h-i-r-k when transliterated in English, literally means “associating,” or “associating partners with.” To be clear, then, the word we read in English translations of the word mushrikun in Arabic, that’s translated as “idolators,” actually means “associators,” or in one scholar’s words, “empartnerers.”12

The Royal Terengganu Quran (1871) in Naskh script. The Qur’an has a more sophisticated attitude toward polytheism than is commonly understood.

When the Qur’an criticizes idolators, then, especially when it uses the word mushrikun, the criticism is of monotheists with residual polytheistic tendencies more than anything else. The Qur’an actually says, “If you ask [mushrikun] who created the heavens and earth, they are sure to say, ‘God’” (31:25) – in other words, the so-called “associators” already understand that a single creator deity made the earth, even though they mistakenly assign partners to this deity. Verses in a different surah begin similarly, but then continue to show the Prophet’s frustration with Meccan monotheists backsliding into polytheism – the surah says, “If you [Prophet] ask them, ‘Who created the heavens and earth?’ they are sure to answer, ‘God,’ so say, ‘Consider those [other gods] you invoke beside Him: if God wished to harm me, could [those other gods] undo that harm?. . .God is enough for me: all those who trust should put their trust in him’” (39:38). This verse, and the previous one, along with an additional one elsewhere (43:87) do not state that the Meccan idolators didn’t believe in Allah or God. The emphasis is instead that the “associators” don’t exclusively believe in Allah, and that they assign various delegates or partners to God that the Qur’an emphasizes are false.

The transition from polytheism to monotheism in the Hijaz, then, had been happening piecemeal for centuries before the revelations of Muhammad. Judaism, Zoroastrianism, and Christianity had scriptures, and relative ideological stability, that the more fluid world of Arabian polytheism lacked. When the Qur’an came to being between 610 and 632, it was emphatically opposed to polytheism. At the same time, though, the Qur’anic voice has a great many names for God, making clear that although there is absolutely only one God, that God is the deity of all things once mistakenly associated with other gods. Some central verses making God’s manifold properties abundantly clear occur toward the end of Surat al-Hashr, or “The Gathering,” which are as follows in the Penguin Dawood translation:

He is God, beside. . .whom there is no other deity. . .He is the Sovereign Lord, the Holy One, the Giver of Peace, the Keeper of Faith; the Preserver, the Almighty, the All-powerful, the Most High. Exalted be God above their idols. He is God, the Creator, the Originator, the Modeler. His are the most gracious names. (59:22-4)13

These are marvelous epithets, a list of names that generally emphasize the grandeur and peerlessness of God. But there are far more names for God in the Qur’an. He is called Rabb “Lord,” and Rabb al-‘alamin, or “Lord of the Worlds” (1.1). He’s described as Khaliq, or “creator” (39:62), al-Khallaq, or “All Knowing Creator” (36:81), al-Bari’, or “the Originator” (2:54, 59:24), al-Qahhar, or “the All Powerful” (12:39), al-Hakim, or “the All Wise,” al-Jabbar, or “the compeller” (59:23), al-Rahman, or “the Merciful” (39:53), al-Tawwab, which means something like “Ever Forgiving” (2:128, 4:64, 110:3), and most simply al-Qarib, or “the Near” (2:286).14 And on the subject of the great many names of God in the Qur’an, scholar Tim Winter writes,

These names effectively define the Muslim universe. Most fundamentally, they save the Qur’an’s anti-pagan polemic from collapsing into the adoration of an ineffable monad, but at the same time they tend to prevent readers from constructing a precise and stable image of the solitary deity. . .The Qur’an, then, constructs a God who inscribes by His own complementary qualities but who seems to transcend them, a God who is fully Other but also seems paradoxically open to meaningful analogies with created things.15

Allah, in the Qur’an, may be just one being, but he contains multitudes, and in his myriad of epithets, he subsumes the dominions and attributes of previous deities. The Surahs make polytheism unnecessary, because Allah is the god of all things for which there ever have been gods.

So that should give you a sense of the immediate Arabian, and moreover Meccan background of the Qur’an. The book did not appear in a sudden flash within a world of polytheistic idolaters, but instead a world where gradients of worshippers spanned the gamut from pious, monotheistic Jews, to fully polytheistic tribespeople, to a great many non-denominational pseudo-monotheists in between, many of them quite familiar with Judaism and Christianity. Read within its immediate theological context, the Qur’an appears less of a radical departure from the religious status quo and more of a firm nudge in the direction in which this status quo had already been headed, and the Prophet himself more of a religious reformer and synthesizer than a disruptive interloper.

Those who found Muhammad the most disruptive were the Meccan oligarchs whose business interests depended on the status quo of the pilgrimage circuit there, and over the past couple of generations, scholars like Montgomery Watt have explored how “the commercialization of Mecca led to growing inequality, social and economic injustices, and a breakdown of certain norms of conduct among Arab tribesmen that seemed to demand a more ethically religious structure.”16 In a region of Arabia with grinding income inequality, where increased contact with sophisticated foreign religions was beginning to make the Meccan oligarchs’ cluttered pantheons seem outdated, the God described in the Qur’an, who did everything that every god had ever done, and who loved and forgave everyone equally, proved a very appealing deity. [music]

Jinn in the Qur’an

In a moment, I want to turn to the subject of the Abrahamic roots of the Qur’an – in other words, the book’s frequent mentions of Biblical figures, and retellings of their stories. Before we do that, though, there is another important, indigenous Arabian element of the Qur’an that we should discuss, and that is the book’s numerous references to jinn, or al-Jinni in Arabic. The Bible and the Qur’an both talk about God, angels, Satan, Jesus, and John the Baptist, but only the Qu’ran talks about jinn – that’s j-i-n-n, not the drink, of course – jinn, invisible creatures, neither evil nor good, that were created alongside humanity and share the world with us to this day. Before and after the Qur’an came along, jinn were, and still are, one of the Arabian peninsula’s great contributions to the folklore of the world.Muhammad would have heard stories about jinn growing up as a child, both in Mecca as well as during his time being raised by a Bedouin wet nurse up in the Hijazi highlands. As scholar Ali Olomi writes,

To the ancient Arab, the world around was teeming with invisible life. The desert may appear barren to the untrained eye, but upon closer examination it is full of unseen powers and entities. It is in the desert, with its dunes and mountains, where the jinn made their home. Such jinn could be mischievous or dangerous, like nature itself. The desert sandstorm and the strange sounds at night were all viewed as manifestations of the jinn, and the canny traveler knew to be careful.17

A Persian illustration, from about 1580, of the Biblical King Solomon planning the construction of his temple, in collaboration with several jinn, as described in Q 27:17. A nice image of the hybrid world of Meccan theology around 600 CE, though the illustration is from much later.

Intriguingly, in Surat al-Hijr in the Qur’an, God states that “We created man out of dried clay formed from dark mud – the jinn We created before, from the fire of scorching wind” (15:29). Similarly, another surah, citing creation as miraculous, remembers how God “created mankind out of dried clay, like pottery, the jinn out of smokeless fire” (55:114-5). Having given jinn a memorable creation story, the Qur’an also offers them most of an entire surah. Surat al-Jinn, the Qur’an’s 72nd surah, explains how the jinn have responded to the Qur’an, and more broadly, tells us what kind of beings they are.

The surah devoted to jinn tells us that the jinn have come to believe in the Qur’an after hearing it (72:1-2). Jinn, like humanity, have learned from the Qur’an that God is a singular being with neither a wife, nor any children (72:3). The jinn, the Qur’an says, approached the outer verges of heaven, listening to learn of what lay beyond its guarded ramparts of shooting stars, some of them doubting that God was capable of resurrection (72:8-9, 7), and they wondered about the fates of sentient beings down on earth (72:10). And Surat al-Jinn concludes that “Men have sought refuge with the jinn in the past, but they only misguided them further. . .Some [jinn] are righteous and others less so: [they] follow different paths. . .Some [jinn] submit to Him and others go the wrong way” (72:6, 11 ,14). The jinn, as you’ve just heard, sometimes sound like friendly guardian spirits, and sometimes like mischievous agents of chaos, a group of created beings older than humanity that also sometimes struggle against the divine order of God. While Surat al-Jinn, for the most part, introduces jinn as ambivalent and morally neutral, elsewhere in the Qur’an they tend more toward mischief and rebelliousness.

Humans, in the Qur’an, are said to have invisible companions, or qarin, who tempt them into illicit choices (50:23, 27). The book states, “[God] assign[s] an evil qarin as a comrade for whoever turns away from the revelations of the Lord of Mercy” (43:36). The qarin, or assigned companion, is a jinn-like figure, unseen and capable of nudging any human in potentially dubious moral directions. Sometimes, in the Qur’an, jinn serve people, as the Biblical King Solomon was served by “hosts of jinn” (27:17), who “made for him whatever he wanted – palaces, statues, basins as large as water troughs, [and] fixed cauldrons” (34:13). More often, however, jinn in the Qur’an mean trouble.

Who Is Iblis?

There is a being in the Qur’an whose name is Iblis. The Qur’an tells us this about Iblis: “[God] said to the angels, ‘Bow down before Adam,’ and they all bowed down, but not Iblis: he was one of the jinn and he disobeyed his Lord’s command. Are you [people] going to take him and his offspring as your masters instead of [God]. . .?” (18:50). This anecdote – that the other angels and jinn bowed down before Adam upon the moment of creation, but not Iblis – appears a number of times in the Qur’an. Elsewhere in the Qur’an, God recalls how “We said to the angels, ‘Bow down before Adam,’ and they did. But not Iblis: he was not one of those who bowed down. God said, ‘What prevented you from bowing down as I commanded you?’ and [Iblis] said, ‘I am better than him: You created me from fire and him from clay.’ God said ‘Get down from here! This is no place for your arrogance. Get out! You are contemptible!” (7:11-13). If this story sounds familiar, it’s about to sound even more familiar, as we read what follows in Surat al-A’raf, in the Penguin Tarif Khalidi translation:[Iblis] said: ‘Defer my judgement until the Day when they are resurrected.’

[God] said: ‘You shall be so deferred.’

[Iblis] said: ‘Inasmuch as You have led me astray, I shall lie in wait for them along Your straight path. Then I shall assail them from their front and from their backs, from their right and from their left. Nor will You find most of them to be thankful.’

[God] said: ‘Be gone, accursed and outcast! As for those among them who follow you, I shall fill hell with you all! And you, Adam, dwell with your wife in the Garden, and eat wherever you wish, but do not come near that tree or else you will be sinners.’ (7:13-19)18

Iblis, then, in the Qur’an, was sometimes a jinni, and sometimes an angel, but most often he is described as a shaytan, or devil.

The Abrahamic religions, which posited a beneficent God ruling over an imperfect world, have always struggled with the problem of evil, inventing various origin stories to explain the sources of malfeasance and suffering. And there was, in Abrahamic religion prior to Islam, a mostly non-scriptural story cycle about a fallen angel who, jealous of humanity, rebelled against God and was tossed down to earth as punishment. This narrative was a central part of largely forgotten Christian sects like Manichaeism and Gnosticism. A version of it appeared in the roughly second century BCE books of 1 Enoch and Jubilees, and by the time Muhammad was born, apocryphal scriptures like the Questions of Bartholomew and the Life of Adam and Eve had recounted the legend of a jealous celestial prince, first Mastema, and Azazel, and increasingly later, Satan. A single line in the Gospel of Luke has buttressed this largely non-biblical story. Jesus says in Luke, “I watched Satan fall from heaven like a flash of lightning” (Luke 10:18).19 The operatic saga of Milton’s Paradise Lost, which most of us think is in the Bible, is a vast para-Christian narrative tacked to tiny scraps of scripture.

This narrative, as we just saw, makes it into the Qur’an, and indeed, it does so at several junctures. Iblis, the only named jinn in the Qur’an, is similar to the Satan of non-biblical Christian traditions. Iblis, though, was not the name of Satan for Christian Arabs like the ones Muhammad would have known, and today, the origins of the name Iblis are uncertain.20 Whatever we call him, the Iblis of the Qur’an, whether he began as an angel or a jinn, following a confrontation with God upon the creation of humanity, was later a shaytan, or devil, and in later Islamic tradition still, ash-Shaytan, or the Devil. And as we come to the subject of the Qur’an’s portrayal of Adam and Eve and Satan, it’s time to move on to discuss the Abrahamic ancestry of the book – how not only the Biblical creation story made it into the Qur’an, but also a sizable number of patriarchs and New Testament figures whose names and stories appear frequently throughout the Qur’an’s 114 surahs.

So, in this program so far, we have talked about some of the native Arabian roots of the Qur’an. We learned that there were deep monotheistic traditions resident in the Hijaz in the year of the Prophet’s birth in 570, traditions that had been there for at least 500 years when he was born. Almost every variety of monotheists had settled up and down the Hijaz, creating a widespread climate in which singular deities sovereign over creation and judgment day were gradually replacing motley polytheistic pantheons. We learned that the Meccans worshipped numerous gods, and that Allah’s daughters Allat, Manat, and al-‘Uzza were among them, but that at the same time, rather than disparaging polytheists pure and simple, the Qur’an disparages nonbelievers as mushrikun, or “associators,” emphasizing that the crime is slipping from pure monotheism, rather than being thoroughly polytheistic. We learned that the many epithets for God in the Qur’an deftly assign dozens of domains and properties to Allah, such that the Qur’an’s deity is high and distant, but at the same time near and present in the myriad phenomena of the world around us. And just now, we’ve learned about how the Qur’an describes jinn, once a cast of Arabian spirits of caves, mountains, storms and wadis, as spirits created by the Abrahamic God, one of whom rebelled and was cast down. Now that we have a decent sense of the Qur’an’s Arabian origins, let’s take a long look at its Abrahamic origins, beginning, appropriately, with the way that it tells the story of Adam and Eve. [music]

The Qur’an on Adam and Eve

As scholar Maria Dakake writes, “It has long been observed that the Qur’an assumes its original audience’s familiarity with Biblical narratives.”21 In other words, when Muhammad first recited the surahs of the Qur’an to Khadija, Ali, Abu Bakr, Zayd, and other Meccans, his listeners must have had an overall familiarity with the major figures of the Tanakh and the New Testament.But how was the Prophet Muhammad familiar with Biblical narratives? Did the Arabs of the Hijaz have access to Arabic translations of the Old Testament, or the New Testament? Could Muhammad have read the Bible, or heard it recited at length? In order to answer these questions, we’re going to need to take a good, long look at the great many Qur’anic verses dealing with biblical figures, once again beginning with Adam and Eve.

As we heard a moment ago, the Qur’an variously retells the story of Adam and Eve. Let’s hear the Qur’an’s basic story about Adam and Eve – this is from Surat al-A’raf, the seventh surah, in a fairly long quote from the Penguin N.J. Dawood translation.

[God said] “And you Adam, dwell with your wife in Paradise, and eat of any fruit you please; but never approach this tree or you shall both become wrongdoers.” But Satan tempted them, so that he might reveal to them their shameful parts, which they had never seen before. And he said: “Your Lord has forbidden you both to approach this tree only to prevent you from becoming angels or immortals.” Then [Satan] swore to them that he would give them friendly counsel. Thus did he cunningly seduce them. And when they had eaten of the tree, their shame became visible to them, and they both hastened to cover themselves with the leaves of the Garden. Their Lord called out to them, saying: “Did I not forbid you both to approach that tree, and say to you that Satan was your veritable foe?” They replied: “Lord, we have wronged our own souls. Pardon us and have mercy on us, or we shall surely be among the lost.” [God] said: “Get you down hence, and may your descendants be adversaries to each other. The earth will for a certain term provide your dwelling and your comforts. There shall you live and there shall you die, and thence shall you be raised to life.” (7:19-25)22

William Blake’s Satan Exulting over Eve (1795). The Qur’an uses the Christian exegesis of the Tanakh’s book of Genesis, though it does not share the Augustinian add-on of Original Sin.

Interestingly, though, the Qur’an, and Islam after it, do not share the Augustinian doctrine of original sin. To the Qur’an, Adam and Eve were hanifs – their default, and the default of all humanity, was a primordial awareness of the sovereignty of God, and the signs of the world as evidence for this God. The Qur’an states, “So [Prophet] as a man of pure faith [or hanif], stand firm and true in your devotion to the religion. This is the natural disposition God instilled in mankind – there is no altering God’s creation – and this is the right religion, though most people do not realize it” (30:30). The “natural disposition” here, which the HarperOne Study Qur’an translates as “primordial nature,” is once again an inbuilt devotion to the Abrahamic God.23 The Augustinian doctrine of Original Sin teaches us that God’s creation of humanity was altered permanently by Adam and Eve’s mistake. The Qur’an, though, teaches that humanity’s default state is a ready awareness of God’s sovereignty, and that this default created state is unalterable. Later Islamic commentators, accordingly, affirmed that when children died, they died in possession of their “natural position” or “primordial nature,” and, they were thus sent to heaven, uncorrupted by the false creeds of later periods of history.24

The question arises then, that if humanity were indeed created with an inborn, antediluvian monotheism – if each human being innately understands that there is one God who created the world and who oversees it, then why is the world filled with such a bustling plurality of creeds and religions? The Qur’an’s answer to this question is that history is cyclical. Humanity makes covenants with God, as Adam and Eve did. But humanity stumbles away from those covenants, and needs periodic reminders of God’s sovereignty. These reminders, in the past, have come in the form of Biblical prophets. The Qur’an says that Adam, Noah, then Abraham, and then Moses, and others, up until Muhammad himself, were all put on earth to compel humankind to return to the original monotheistic reverence with which they were naturally born. To repeat, the Qur’an sees Biblical prophets as a series of recurring reminders sent to earth to admonish and nudge humanity back toward the hardwired righteousness with which we are all born. The corollary of the Qur’an’s basic understanding of human history is that the book’s view of human nature is essentially an optimistic, and hopeful one. [music]

Noah in the Qur’an

The Qur’an, then, teaches us that humanity has an inbuilt moral compass pointed toward God, and that prophets arrive at certain junctures of sacred history to remind us of what we already innately understand. There are hundreds of references to Biblical prophets in the Qur’an. Biblical prophets in the Qur’an are exemplary, and often tragic figures – brave, but unheeded; righteous, but ignored. In scholar Robert Tottoli’s words, in the Qur’an, “The tales of the biblical prophets are marked by adversity, opposition, and hardship that each prophet must be able to resist, trusting in his final victory willed by God. . .Torment or conflict, and escape from danger, often involving a flight of some sort, is repeatedly presented as the primary adversaries suffered by the prophets.”25 Biblical prophets often appear in the Qur’an in enumerated lists, as amassed evidence that what the Qur’an is teaching has already been taught before. The earliest of these fraught figures is Noah.Noah’s story appears most lengthily its 26th surah. Let’s hear how the Qur’an recounts what happened to Noah, in the HarperOne Study Qur’an translation.

The people of Noah denied the messengers, when their brother Noah said unto them, “Will you not be reverent? Truly I am a trustworthy messenger unto you. So reverence God and obey me. And I ask not of you any reward for it; my reward lies only with the Lord of the worlds. So reverence God and obey me.” They said, “Shall we believe [in] you, when the lowliest follow you?” [Noah] said, “What knowledge have I of what they used to do? Their reckoning is only by my Lord, were you but aware. And I shall not drive away the believers. I am but a clear warner.” They said, “Truly if you cease not, O Noah, you shall indeed be among the stoned.” He said, “My Lord, verily my people have denied me. So decide between me and them, and deliver me and the believers who are with me!” So We delivered him and those who were with him in the full-laden Ark. Then afterwards We drowned those who remained. (26:105-120)26

Jan van Balen (attr.) Noah and the Ark (c. 1625-50). The Qur’an depicts Noah as having a fraught relationship with his contemporaries, while in the Bible, Noah doesn’t have nearly as many spoken lines.

Let’s talk about why these differences exist. And listen carefully here, by the way – this will be key to understanding the Qur’an’s complex relationship with the Bible. There is no historical evidence that Arabic translations of the Bible existed in the early 600s, when the Qur’an was produced.27 To be clear, there were plenty of Arabic speaking Jews and Christians, and Muhammad would have known some of them. The Jewish gentility of Yathrib and Khaybar and elsewhere would have known the liturgical and scholarly languages of Hebrew and Aramaic. Some of the Christian communities, like Nestorians who had fled Byzantine persecutions in the mid-400s, would have still used some of the New Testament’s original Greek. However, though sacred languages may have been familiar to the Arabic-speaking Jews and Christians of the Hijaz, and though they may have had liturgical readings of scriptures in their original languages, we have no evidence that there was an Arabic Bible – no standard Arabic rendering of either the Old or New Testament.28

This meant, as we’ll see in the remainder of this episode, that Arabs like Muhammad, and probably even Jews and Christians themselves, encountered biblical figures as folkloric archetypes – protagonists of both biblical and non-biblical story cycles, like the one we just heard about Noah. Noah, in the Qur’an, is the boat guy, just like in the Bible. But Noah has different properties, too – he is a hanif, preaching primordial righteousness to any who will listen, and many who will not. The Qur’an was produced in a culture in which biblical figures and truisms were all over, but the Bible itself was not, and so the Qur’an often repurposes Biblical patriarchs in its own distinctive ways. [music]

Abraham in the Qur’an

After Noah, in the Qur’anic lineage of prophets, comes Abraham himself. Abraham, as we learned in prior episodes, was heavily associated with Mecca. Growing up in the city, when Muhammad was a boy, Muhammad would have seen the small hills Safa and Marwa, mounds that, according to tradition, Abraham’s concubine Hagar ran back and forth between, searching for water for her son Ismail. Muhammad would have seen the Zamzam well, which, according to local tradition, God had created to provide water to Hagar and Ismail, and of course Muhammad knew all about the Kaaba, that cube-shaped shrine with an appendant porch that the locals said had been constructed by Abraham. In a way, just as the ancient Greek pilgrimage site of Delphi honored Apollo, Mecca’s principal figure seems to have been Abraham – his was the main shrine that you came to see in the year 600. There were many gods in Mecca, but Abraham was associated with the god who was inexorably, due to the forward momentum of history, gaining ground.Let’s talk about Abraham in the Qur’an, now. His name appears seventy times. The fourteenth Surah is named after him. Abraham, in the Bible, is born ten generations after Noah, who was born nine generations after Adam. After the Old Testament God’s first judgment day – the Biblical Flood – Noah renewed a covenant with God, but ten more generations passed, and humanity’s ever-faltering morality required the coming of another prophet, and a new covenant. That new prophet was Abraham, born nineteen long generations after the creation of humanity. Though Abraham came along quite a while after Noah, both the New Testament and the Qur’an emphasize Abraham as an especially ancient patriarch. Paul’s epistle to the Romans describes how there are “adherents to the law but also. . .those who share the faith of Abraham. . .in the presence of God in whom he believed” (Rom 4:17).29 The New Testament Book of Romans, there, points out that Abraham lived before Moses, and thus before the many commandments of Mosaic Law, but also that Abraham was still a righteous person who shared a covenant with God.

This distinction – that Abraham was virtuous and devout before the Torah ever came to be – was not lost on the Qur’an. The Qur’an exclaims,

People of the Book, why do you argue about Abraham when the Torah and the Gospels were not revealed until after his time? Do you not understand?. . .Abraham was neither a Jew nor a Christian. He was upright and devoted to God, never an idolator, and the people who are closest to him are those who follow his ways. (3:65, 67-8)

The Arabic original for “He was upright and devoted to God” is that Abraham was a hanifan musliman, or a hanif who submitted, or more simply, that Abraham was a Muslim. To some ears, this might be an incendiary statement, but the point that Qur’an makes here is that before, during, and after the entire Bible was written, there were always those of us humans who used our inbuilt capacities to understand the singularity and righteousness of God, and that Abraham was one of these.

There are four sustained narratives about Abraham in the Qur’an, and they follow the Qur’an’s general depiction of prophets as embattled figures, resolute but scorned by indifferent worlds. The first Qur’anic story builds on a nonbiblical Jewish tradition about Abraham’s father owning an idol shop.30 Abraham, in the Qur’an, scornful of his father’s worship of idols (6:74), has an epiphany. Abraham first worships a star, and then the moon, and then the sun, but he sees that all of these celestial bodies set, and Abraham wants to worship something more permanent (6:75-9). Once Abraham vows to worship God, he encounters in his own people many errant skeptics – mushrikun who mistakenly associate other deities with the one true God (6:80-83). That’s the first long story about Abraham in the Qur’an. The second sustained narrative about Abraham in the Qur’an builds on the first. Again, Abraham tells his father and his contemporaries not to worship idols (21:52-7). But this time, Abraham breaks all of the idols into pieces, except for one (21:58). The idol-worshippers are furious, and they plan to burn Abraham, but God protects Abraham and vows retribution against his assailants (21:60-70). These Qur’anic stories about Abraham are again non-biblical, but they had roots in Jewish exegesis. In a town like Mecca, so focused on Abraham, many stories about the patriarch – including those from Jewish traditions, would have been in circulation.

Different stories about Abraham – stories that are actually told in the Bible – also make their way into the Qur’an. Just as he does in the Bible, in the Qur’an, Abraham expresses incredulity toward angelic visitors when he hears that his wife Sarah will soon bear him a son, and then Abraham pleads with the angels to have mercy on the city of Sodom, where Abraham’s nephew Lot lives (11:69-76).31 And just as he does in the Bible, in the Qur’an, Abraham is compelled to sacrifice his son, though the Qur’an never says which son.

The Qur’anic version of this famous moment in the Bible is offered in terse, brisk verses that have some significant differences with what we read in Genesis. Here’s the Abraham-sacrificing -a-son story, as it appears in the 37th surah of the Qur’an, in the Penguin Tarif Khalidi translation.

When the son was old enough to accompany him, he said: “My son, I saw in a dream that I was sacrificing you, so reflect and give me your opinion.” [The boy] said: “Father, do as you are commanded and you shall find me, God willing, steadfast.” When both submitted to the will of God, he bent his head down and on its side. And [God] called out to him: “O Abraham, you have made your vision come true.” Thus [does God] reward the virtuous. That was indeed a conspicuous ordeal. And [God] ransomed him with a mighty sacrifice. And conferred honour upon him among later generations. Peace be upon Abraham! Thus [does God] reward the virtuous. (37:102-110)32

Rembrandt’s Abraham and Isaac (1635). In the Qur’an’s version of the story, it’s not specified whether Isaac or Ishmael is the son to be sacrificed, and the story of the sacrifice is shorter.

There are differences, then, between the Biblical and Qur’anic narratives of Abraham sacrificing his son, and about Abraham’s youth. The Qur’an offers Abraham’s life selectively, emphasizing him as a righteous prophet, and a proto-Muslim, rather than offering the Bible’s full biography. And generally, in comparing the Qur’an to the Book of Genesis, it’s important to remember that we’re setting an apple alongside an orange. The Book of Genesis is an extended third person omniscient narrative, presented in chronological order. The Qur’an is an oration, made of both verse and prose. It scatters prophetic elements of Abraham’s life into multiple surahs, citing putative information about the Abraham that would have been familiar to Late Antique Arabs of the Hijaz. The Bible tells Abraham’s story. The Qur’an cites elements of this story for rhetorical purposes, assuming that you’re familiar with it, and using the old tale to emphasize that righteous monotheists have been out there since way back before the Israelites crossed the river into Israel.

So, having looked at the stories of Adam, Eve, Noah, and Abraham in the Qur’an, we’ve learned about how the Qur’an retells parts of the Bible’s patriarchal sagas. Sometimes the Qur’an introduces narrative elements not present in the Bible, such as Noah’s son drowning, or Abraham smashing his father’s idols. At other times, the Qur’an’s narratives of patriarchs and prophets are pretty closely aligned with relevant passages in the Bible. Most frequently of all, though, the Qur’an briefly references a Biblical episode in order to make a point, assuming that its audience is sufficiently grounded in Biblical knowledge to understand that point. Now that we’ve gone through the most foundational of the Biblical patriarchs in the Qur’an, let’s move forward through a few more, and explore what the Surahs have to say about Moses, Jonah, and Job. [music]

Moses in the Qur’an

Moses is another frequent presence of the Qur’an. The champion of the Israelites, recipient of the commandments, ultimate lawgiver of the twelve tribes, and the anchor of the Pentateuch after Exodus, in the Bible, Moses’ most frequent role is recurrently convincing God not to smash the Israelites after they’ve committed this or that transgression. Other Biblical patriarchs come along earlier in the Torah, but it is Moses who receives the most page space, arriving at the Israelites’ hour of greatest need down in Egypt, guiding them back home, and then, on the banks of the Jordan, offering the entire Book of Deuteronomy as a retirement speech before his successor Joshua, and the subsequent judges, lead the Israelites into a bloody military conquest of Canaan. Moses’ story in the Bible is a long one, and the Qur’an doesn’t tell the entire thing.The Qur’an references Moses often as one of the many hanifs who submitted to God, and a prophet, like many Biblical prophets, who was doubted in his own time. The Qur’an recounts how Moses was born at a dire juncture when the Egyptian Pharaoh had resolved to kill the sons of the Israelites (Ex 1:22, Q 28:4). The Qur’an tells of how Moses received the tablets on which the commandments were inscribed (7:145, 154). But more than any other Biblical stories about Moses, the Qur’an focuses on two. The first is Moses’ confrontation with the Egyptian Pharaoh. The second is the infamous Golden Calf episode. Both of these, as with the Qur’an’s preferred stories about other Biblical prophets, show Moses as an embattled figure, striving to promulgate the basic truths about God in an iniquitous and backsliding world.

The clash between Moses and the Pharaoh is a central episode in both the Book of Exodus as well as the Qur’an. In Exodus, the confrontation takes place in a sort of sorcery contest, in which Moses and his brother Aaron turn Moses’ staff into a snake, then turn the Nile to blood, then summon plagues of frogs, gnats, flies, boils, thunder, locusts, and darkness, until Moses and Aaron pray for the killing of all of the firstborn children of Egypt. The narrative, perhaps 1,200 years old when Muhammad was growing up, still had an enduring power, with its story of lowborn, virtuous commoners confronting the highborn heathens, and ultimately winning out.

Moses and Aaron before Pharaoh (1537), by the Master of the Dinteville Allegory. The Qur’an is fond of this story and tells it lengthily.

What follows in the Qur’an is a truncated version of the tale of the Exodus, narrated by God himself. God recollects sending plagues of locusts, lice, frogs, and blood down among the Egyptians, emphasizing that all of these were intended as clear signs. The Egyptians, however, blamed each subsequent disaster on the Israelites, rather than understanding them as signs, until eventually, God drowned many Egyptians in the sea. God then continues the story of the Exodus in the Qu’ran, using the royal ‘We:’ “We took the Children of Israel across the sea, but when they came upon a people who worshipped idols, they said, ‘Moses make a god for us like theirs’” (7:138). Thus begins the second major story about Moses in the Qur’an – the tale of the Commandments, and the Golden Calf.

As the Israelites began their fateful hankering for false idols in this same sequence in Surat al-A’raf, the seventh surah of the Qur’an, subsequently, Moses spent forty nights in isolation (7:142). Moses asked God to show himself, and rather than appearing as a burning bush, God caused a mountain to crumble in order to demonstrate his presence to Moses (7:143). God then recollects in the Qur’an, “We inscribed everything for him in the Tablets which taught and explained everything, saying, ‘Hold on to them firmly and urge your people to hold fast to their excellent teachings. I will show you the end of those who rebel’” (7:145). And while Moses was busily receiving the commandments of God on the mountain, the Israelites down on the flatland had begun behaving very badly. They were worshipping, the Qur’an says, “a mere shape that made sounds like a cow – a calf made from their jewelry” (7:148). Upon Moses’ return, he chastised the Israelites, including his brother Aaron, whom he’d left to watch over them, and the Israelites repented. Moses then hefted the tablets containing the commandments, and he selected seventy representatives to help lead them, and prayed for mercy from God.

More than fifty verses of the Qur’an’s seventh surah, in the sequence you’ve just heard, retell the story told in the early chapters of Exodus. They follow Exodus fairly closely, with minor differences. Other portions of the Qur’an retell or cite parts of Moses’ story, emphasizing different parts of it for various reasons, including Moses’ confrontation with the Pharaoh (26:18-68, 40:23-34), the Golden Calf episode and its aftermath (20:86-98), and the drowning of the Egyptians (20:77). Elsewhere, the Qur’an tells of how Moses urged his reluctant people to cross the river into Canaan, even though they feared the warlike tribes who lived there (5:20-26). In all of these cases, Moses in the Qur’an is a persistent, beleaguered figure, never at rest, and required again and again to prove the sovereignty of God to dubious Egyptians and backsliding Israelites alike. He is perhaps at his most vulnerable in a brief appearance when he asks the Israelites, “My people, why do you hurt me when you know that I am sent to you by God?” (61:5). Here, Moses, like the other Biblical prophets in the Qur’an, suffers from a basic and flabbergasting paradox. After showing Egyptians and Israelites palpable proof of God’s presence, he is baffled to find, again and again, scorn and resistance. From Noah onward, then, the long line of Biblical prophets in the Qur’an are hampered and flummoxed by historical epochs that are not yet ready for them.

Job and Jonah in the Qur’an

While Moses gets a considerable amount of page space in the Qur’an, so, too, do two final figures from the Old Testament, and these are Job, and Jonah. Let’s start with Job. The Book of Job is one of the most distinctive and searing texts in the Bible, exploring the theme of the Problem of Evil more than any other piece of canonized scripture. At over 12,000 words, and in a series of dramatic dialogues, the Bible’s Book of Job shows the titular character stretched to the limits of what any person can be expected to endure. At the Book of Job’s end, as we learned a hundred episodes ago, the protagonist’s questions are never answered, with Job listening to God’s monologue about how God beat the Behemoth and Leviathan, and then, in the final verses, Job receiving replacement children and livestock for the ones God has destroyed. Job, during the life of Muhammad, was another figure from Judaism known in Mecca, although the Qur’an’s presentation of Job is somewhat shorter and simpler than the Bible’s. Here are the Qur’an’s longest two passages about Job, in the Penguin Dawood translation:And tell of Our servant Job. He called out to his Lord, saying ‘Satan has afflicted me with anguish and torment.’ ‘Stamp your feet [on the ground]; here is a cool spring for you to wash in and drink from.’ We restored. . .him his household and as many more with them: a blessing from Ourself and an Admonition to those that are of good sense possessed. . .We found him a steadfast; a good and penitent man. (38:41-4) [That’s the first one. The next one:]

And tell of Job; how he called on his Lord, saying: ‘I am sorely afflicted: and of all those that show mercy You are the most merciful.’ We answered his prayer and relieved his affliction. We restored to him his family and as many more with them: a blessing from Ourself and an Admonition to the devout. (21:83-4)34

Those are the Qur’an’s stories about Job. We should always remember that Satan is not in the Old Testament, though Christianity and Islam have retrojected him there. The Old Testament tale of Job is a more complicated one, with an ambiguous figure called “the adversary” challenging God to test Job, and then God hurting Job and his family as a result of the bet, until at the apex of the Book of Job in the Bible, God essentially tells Job to shut up.

The Qur’anic version of the story is in some ways morally tidier. It is Satan, through and through, who hurts Job and his family in the Qur’an, and when goodly Job asks God for help, God helps. The Qur’anic tale of Job is the satisfying story of a pious person rewarded, based as it likely was on perhaps a simpler and more folkloric version of Job’s story current in monotheistic circles in seventh-century Arabia.

Just as the Qur’an tells the story of the Book of Job in a truncated fashion, and with important variations, the Qur’an also offers the tale of the Book of Jonah. The Book of Jonah is one of the more optimistic narratives in the Old Testament. In Bible’s Book of Jonah, a reluctant prophet from Samaria receives a message from God that he has to go all the way to Nineveh, in Assyria. Trying to duck out of his duty, Jonah hops on a ship, but, when this ship is blustered by gales, Jonah, realizing that he’s incurred divine wrath and not wanting to get all the sailors onboard killed, jumps overboard, gets swallowed by a whale and spends three days and nights there, then gets puked back up onshore. Afterward, Jonah heads to Nineveh. Jonah tells the Ninevites to repent. They do. 120,000 Ninevites are saved. Jonah, still sullen and surly, still isn’t happy about having had to go all the way to Mesopotamia, but God patiently keeps explaining to Jonah why Jonah had to go. And that’s it. That’s the Biblical version of the Book of Jonah, a lovely, perhaps later Second Temple period book in which, wonder of wonders, good gracious, people actually listen to an Abrahamic prophet, and things turn out alright.

The Qur’an includes anecdotes about Jonah, though not his entire story. Reflecting on how the Ninevites repented in the Book of Jonah narrative, Surat Yunus, the tenth surah of the Qur’an, named after Jonah, says, “If only a single town had believed and benefited from its belief! Only Jonah’s people did so, and when they believed, We relieved them of the punishment of disgrace in the life of this world, and let them enjoy life” (10:98). It’s a nice verse, celebrating one of the more joyful junctures of the Bible’s prophetic books. A different surah, although very quickly, retells the entire Book of Jonah with reasonable accuracy. Here’s the Qur’an’s summation of Jonah, in the Penguin Tarif Khalidi translation of what are in the original Arabic short, rich lines of verse:

Jonah too was a messenger.

Remember when he fled on a laden ship.

He cast lots and was bested.

A great fish swallowed him: he was to blame.

Had he not been one who glorified God,

He would have stayed in its belly till the Day that mankind is resurrected.

We cast him out into the wilderness, ailing.

And we caused to sprout over him a tree of gourd,

And [then] sent him to a hundred thousand, or more.

They believed, so We granted them enjoyment of life (139-148)35

The narrative lines up quite closely with the Book of Jonah, although the shade tree in the Old Testament doesn’t arise until after the Ninevites are saved.

So in summation, we have just, as many people have, explored the way that the Qur’an cites and adapts the Old Testament’s stories of the patriarchs. At a general level, the Qur’an cites each patriarch’s story as the tale of a pre-Islamic Muslim, sent to Earth to remind humanity to return to God. Biblical prophets in the Qur’an are, Jonah aside, steadfast, willing vessels for divine messages, though from Noah enduring the scorn of his community onward, the Qur’an’s gaggle of prophets do not have easy lives. Compelled by divine will on one side and disdained by their contemporaries on the other, Prophets in the Qur’an also, like Jonah, suffer personal crises in which the tribulations of their lives lead them to feel exhaustion and doubt.

So now that we’ve taken a very specific look at the Qur’an’s Abrahamic roots in the Old Testament, let’s look at the Qur’an’s treatment of some other Biblical figures. Just as Jonah, Job, Moses, Abraham, Noah, Adam, and Eve appear to have been familiar figures to the masses of Mecca around 600 CE, so, too, were the major figures of the New Testament. More than anyone in the New Testament, John the Baptist, the Virgin Mary, and Jesus Christ appear frequently in the pages of the Qur’an. So as we come to our final hour or so of content on the Qur’an, let’s consider what the book has to say about the most iconic figures of Christianity. [music]

John the Baptist in the Qur’an

John the Baptist, that insect-munching desert hermit who predicts the coming of Jesus in the New Testament, shows up a few times in the Qur’an. The Qur’an retells the Biblical story of John the Baptist’s early life (Luke 1:1-20), emphasizing that Zechariah, or Zakariyya in the Qur’an, in the Qur’an, was an old man without any kids (19:8), and that Zechariah’s wife Elizabeth, who is unnamed in the Qur’an, was unable to have children (3:40, 21:90). Old Zechariah, in the Qur’an, prays for a child (3:38, 21:89), humbly telling God that even though his hair is gray and his wife is barren, he still wants a child to further the lineage of Jacob (19:6). And God promises the elderly pair a child, telling Zechariah that he will indeed have a son – that this son’s name will be Yahya (the Arabic form of the Aramaic name Yohanon, or John). Interestingly, in the Qur’an, God says that “We have chosen this name for no one before him” (19:7). This Qur’anic detail is not in the Bible, and must have come from an extra-Biblical narrative about John the Baptist current in the Hijaz by the seventh century.The Qur’an retells the Gospel of Luke’s tale of John the Baptist’s father Zechariah being skeptical about the impending miraculous birth, and also of how God struck Zechariah mute when Zechariah asked for a confirmation of the miracle to come (19:10). And again, paralleling the New Testament, the Qur’an recounts how John the Baptist was born with a firm moral compass and showed great promise as a young person (19:12-15). And that’s actually all the Qur’an has to say about Yahya, or John. The book does not retell the Bible’s famous narrative of how John the Baptist was beheaded at the birthday party of the tetrarch Herod Antipas, leaving off to turn to the subject of Maryam, or the Virgin Mary.

The Virgin Mary in the Qur’an

Maryam and ʿIsa, or Mary and Jesus, are revered figures throughout the Qur’an. And but for a few very important sticking points, the Qur’an follows New Testament teachings about this pair. Let’s begin with Mary. Mary is actually mentioned more times in the Qur’an than she is in the Bible, and her life is drawn out more extensively in the Qur’an. As we’ve learned in prior episodes, although the New Testament treats Mary pretty briefly, she was later, in apocryphal books, especially the Proto-Gospel of James, and the Gospel of Pseudo-Matthew, given an extensive backstory. Without getting into a lot of details, it can simply be said that by the year 600, Mary was a more revered figure in Christianity than she had been when the New Testament was actually being written, and the Qur’an respects her and tells her story in a way consistent with general Chrisitan truisms current to the early seventh century.Earlier Christian literature about Mary actually began by assigning Mary herself a virgin birth from her mother Anna, and telling of how Mary grew up in the Jerusalem Temple, leading an incomparably pious life there from age three onward.36 The Qur’an also engages with Mary’s early life. In the Qur’an, we first meet Mary as the daughter of a man named ʿImran (66:12), after whom the third Surah of the Qur’an is named. Mary, the Qur’an says, was pledged to God from birth (3:36), and she was a signal from God (23:50). As Late Antique Christian apocryphal texts taught, the Qur’an describes how Mary was raised in the Temple and given sacred food (3:37), and how she was such a special child that her guardians didn’t know who would care for her (3:44). Then comes the story of Mary’s miraculous pregnancy.

Surat Maryam, or the surah of Mary, tells of the Immaculate Conception of Jesus, a narrative which follows on the heels of the miraculous birth of John the Baptist. Here’s the story of Mary’s annunciation and pregnancy, as it’s told in the Qur’an. This the HarperOne Study Qur’an translation:

And remember Mary in the Book, when she withdrew from her family to an eastern place. And she veiled herself from them. Then We sent unto her Our Spirit, and it assumed for her the likeness of a perfect man. She said, “I seek refuge from thee in the Compassionate, if you are reverent!” He said, “I am but a messenger of thy Lord, to bestow upon thee a pure boy.” She said, “How shall I have a boy when no man has touched me, nor have I been unchaste?” He said, “Thus it shall be. [The] Lord says, ‘It is easy for Me.’” And [it is thus] that We might make him a sign unto mankind; and a mercy from Us. And it is a matter decreed. So she conceived him and withdrew to a place far off. (19:16-22)

Poor Mary, in the Qur’an, has no husband, and no Bethlehem manger, as in the Gospel of Luke (2:7). In the Qur’an, Mary gives birth in the wilderness, clinging to a palm tree, though a divine voice promises her that a stream at her feet will provide her water, and that shaking the aforementioned palm tree will provide her with a bounty of fresh dates whenever she needs them (19:23-26). And this brings us to the subject of Jesus and his birth in the Qur’an.

As we begin to explore the Qur’anic stories of Jesus’ nativity, it’s important to remember something. Just as apocryphal narratives about the Virgin Mary had proliferated by the year 600, by the time Muhammad lived, a great many non-Biblical narratives about Jesus had also grown popular during Late Antiquity. An entire genre of what we might call Christian devotional fiction had arisen by about 600 that generally gets called “Infancy Gospels,” including the Infancy Gospel of Thomas, the Proto-Gospel of James, the Gospel of Pseudo-Matthew, and more. These texts offered long accounts of Jesus’ earliest years, his childhood, and adolescence, many of which are very endearing, and well written, and have cute baby Jesus scenes, though, again, they’re non-canonical. The Qur’an, as it tells Jesus’ story in various surahs, makes use of this outer halo of stories about Christ, in addition to the narratives actually canonized in the Gospels.

In an appealing scene in the Qur’an, the Virgin Mary returns to her people after giving birth to Jesus. Mary’s family sees that she’s had a baby out of wedlock, and, chastening her, they tell her that her parents were good people, implying that she’s a fallen woman. Mary then points to the baby Jesus, who, miraculously, speaks, explaining to everyone, “I am a servant of God. He has granted me the Scripture; made me a prophet; made me blessed wherever I may be. He commanded me to pray, to give alms as long as I live, to cherish my mother. He did not make me domineering or graceless. Peace was on me the day I was born, and will be on me the day I die and the day I am raised to life again” (19:30-33). The courteous, well-spoken infant, we might imagine, silenced Mary’s family’s harsh words against her. And of Mary’s later life, the Qur’an says nothing, leaving off with this scene of baby Jesus vindicating his mother from charges of indecency. And speaking of ‘Isa, or Jesus, let’s shift our focus to Jesus himself in the Qur’an for a while. [music]

Jesus in the Qur’an

Jesus is revered in the Qur’an as a holy prophet born of a virgin. Being a servant of God and given a miraculous birth, in the verses of the Qur’an related to Jesus, Jesus leads a righteous life, serving as one of God’s periodic reminders to return to submission to the original, simple monotheism of the Biblical Abraham, hence the fact that Jesus’ disciples in the Qur’an are called muslimun, or “submitters” (3:52, 61:14), or Muslims. The language here has some weight from later theological history, but the basic message – that Jesus’ disciples agreed to submit to God, is straightforward and uncontentious.And likewise, much of what the Qur’an has to say about Jesus is in line with, particularly, Pauline theology in the Bible. For instance, Jesus says, in the third surah in the Qur’an, “I will heal the blind and the leper, and bring the dead back to life with God’s permission; I will tell you what you may eat and what you may store up in your houses. . .I have come to confirm the truth of the Torah which preceded me, and to make some things lawful to you which used to be forbidden” (3:49-50). The verses there share the general spirit of the Gospels and especially the Pauline epistles – Jesus performs evidentiary miracles and updates the old laws of Moses, guiding the Israelites and others back toward a simpler, more ecumenical religion.

Julius Sergius von Klever’s Christ Walking on Water (c. 1880). Much of what the Qur’an has to say about Jesus has roots in Late Antique Christian theology.

Let’s talk for a moment about the Qur’an’s denial of the divinity of Jesus. Muhammad likely knew a number of different kinds of Christians. As mentioned earlier, these would have included Syriac Christians – Melkites, Jacobites, and Nestorians, along with Copts, and Armenian and Ethiopian Christians, as well. Arabia, by the year 500, was also home to Jewish Christian sects, like the Nazarenes, Ebionites, and Elkasaites, who, from what little we know about them, were Jewish groups that embraced Jesus as a messiah, but held to Mosaic Laws in different ways, and sometimes practiced cultic purity rituals. For all of these groups – especially Monophysites and other Christian refugees exiled from the Byzantine empire due to their specific creeds, the question of Christology was a riddle half a thousand years old – this question of whether Jesus was human, or a divine spirit, and how much of him was human and how much divine, and how his natures comingled, and that kind of thing – this was the central preoccupation of Late Antique Christianity. The Qur’an, in verses like the ones you heard a moment ago, endeavors to clear up this riddle (3:60-2, 43:59), again, telling its readers Jesus was not the son of God, and by extension, taking a firm position within the long history of Christological controversies, church councils, excommunications and exiles that had been so central to Christianity’s first five centuries.

It’s important, then, to understand the Qur’an’s denial of the Trinity in context. In one sense, this denial is anti-Christian polemic. But the Qur’an’s view of Jesus as a great prophet, born of immaculate conception – though nothing more – was also intended as a theological simplification, sweeping away the old paradox of trinitarian monotheism and inviting everyone, Jews and pagan Arabs alike, to revere Jesus Christ. The Qur’an’s distinctive matronymics for Jesus show this desire in action. Christ, in the Qur’an, is called ʿIsa ibn Maryam (5:78, 19:34) and Ibn Maryam (23:50, 43:57) – “Jesus, son of Mary,” and “son of Mary.” Because while there was some disagreement about whether Jesus was the son of God, anyone who knew anything would agree that Jesus was the son of Mary.

While the Qur’an quite clearly denies that Jesus is the son of God at several points, the Qur’an departs from Christian doctrine in another, almost equally salient way. In a word, the Qur’an alleges that Jesus did not die at the crucifixion. First of all, again, in the Qur’an, Jesus is one of God’s prophets, and even one born via immaculate conception. God seems to have very special plans for Jesus. The Qur’an explains, “God said, ‘Jesus, I will take you back and raise you up to Me: I will purify you of [these] disbelievers. To the Day of Resurrection I will make those who followed you superior to those who disbelieved” (3:46). This all sounds reasonably consonant with Christian doctrine, but in the next surah, we hear the following much more controversial verses, in the Penguin Tarif Khalidi translation: