Episode 121: The Umayyad Caliphate

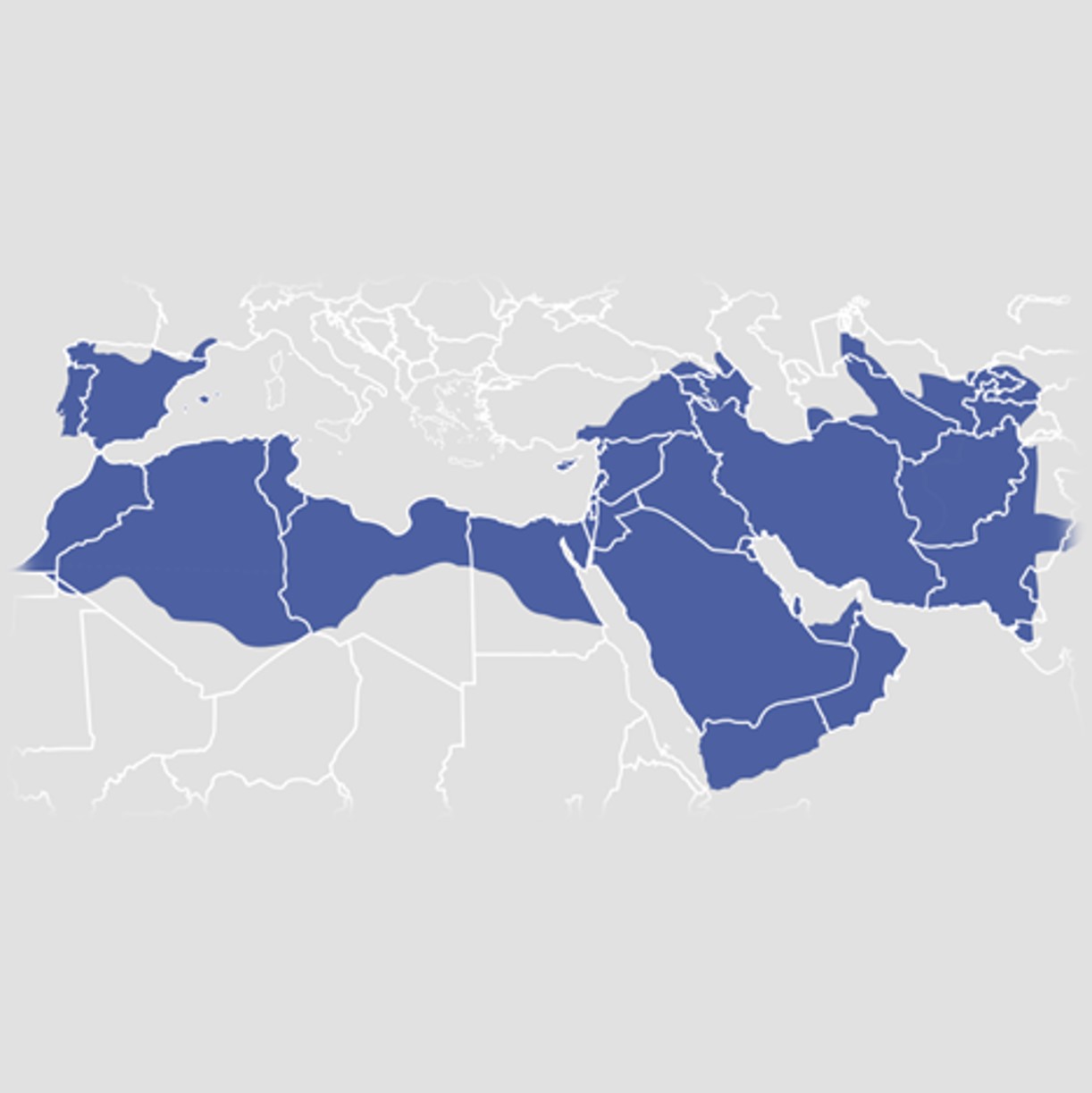

The Umayyad Caliphate, from 661-750, became the largest empire the world had ever known, even as it suffered through two civil wars and significant internal divisions. This episode covers its overall military, political, and cultural history.

Episode 121: The Umayyad Caliphate

Gold Sponsors

David Love

Andy Olson

Andy Qualls

Bill Harris

Christophe Mandy

Jeremy Hanks

John David Giese

KelleyGr

Laurent Callot

Maddao

ml cohen

Nate Stevens

Olga Gologan

Steve baldwin

Silver Sponsors

Lauris van Rijn

Alexander D Silver

Andreu Andreu i Andreu

Basak Balkan

Boaz Munro

Charlie Wilson

David

Devri K Owen

Ellen Ivens

Evasive Species

Hannah

Jennifer Deegan

John Weretka

Jonathan Thomas

Julius Barbanel

Michael Sanchez

Mike Roach

rebye

Top Clean

Sponsors

Katherine Proctor

Carl-Henrik Naucler

Joseph Maltby

Stephen Connelly

Chris Guest

Sander

Matt Edwards

A Chowdhury

A. Jesse Jiryu Davis

Aaron Burda

Abdul the Magnificent

Aksel Gundersen Kolsung

Alex Metricarti

Andrew Dunn

Anthony Tumbarello

Ariela Kilinsky

Arvind Subramanian

Bendta Schroeder

Benjamin Bartemes

Berta Kienle

Brian Conn

Carl Silva

Cat Peterson

Charles Hayes

Chief Brody

Chris Auriemma

Chris Brademeyer

Chris Ritter

Chris Tanzola

Christopher Centamore

Chuck

Cody Moore

Daniel Stipe

David Macher

David Stewart

Denim Wizard

Dominic Klyve

Doug Sovde

Earl Killian

Eliza Turner

Elizabeth Lowe

Eric McDowell

Erik Trewitt

Anonymous

Francine

Friederike Otto

FuzzyKittens

Garlonga

Glenn McQuaig

J.W. Uijting

James McGee

Jason Davidoff

Jay Cassidy

JD Mal

Jillyp

Joan Harrington

joanna jansen

John Barch

John Sanchez

John-Daniel Encel

Jonah Newman

Jonathan Whitmore

Jonathon Lance

Joran Tibor

Joseph Flynn

Joshua Edson

Joshua Hardy

Kathrin Lichtenberg

Kathryn Kane

Kathy Chapman

Kyle Pustola

Lat Resnik

Laura Ormsby

Le Tran-Thi

Leonardo Betzler

Lori Gum

Maria Anna Karga

Mark Griggs

MarkV

Martin Schleuse

Matt Hamblen

Maury K Kemper

Michael

Mike Beard

Mike Sharland

Mike White

Morten Rasmussen

Mr Jim

Nassef Perdomo

Neil Patten

noah brody

Oli Pate

Oliver

Paul Camp

pfschmywngzt

Richard Greydanus

Riley Bahre

Robert Auers

Robert Brucato

De Sulis Minerva

Rosa

Ryan Goodrich

Ryan Shaffer

Ryan Walsh

Ryan Walsh

Shaun

Shaun Walbridge

Sherry B

Sonya Andrews

stacy steiner

Steve Grieder

Steven Laden

Stijn van Dooren

Stuart Sherman

SUSAN ANGLES

susan butterick

Susan Hall

Ted Humphrey

The Curator

Thomas Bergman

Thomas Leech

Thomas Liekens

Thomas Skousen

Thomas Woolverton

Tim Rosolino

Tod Hostetler

Tom Wilson

Torakoro

Trey Allen

Troy

Valentina Tondato Da Ruos

vika

Vincent Vandeven

William Coughlin

Xylem

Zak Gillman

The Umayyad dynasty has a checkered reputation in Islamic history. The geopolitical achievements of the Umayyads are unquestionable. They managed to conquer even more territory than the previous caliphs, including what is today Spain. They built the Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem, and al-Aqsa Mosque next to it, the Great Mosque of Damascus, and they greatly expanded the Prophet’s Mosque in Medina. They were also, however, responsible for keeping Muhammad’s cousin and son-in-law Ali, and his sons, out of power, and killing Ali’s youngest son Husayn. They practiced nepotism on an intercontinental scale, forcing colonized populations to kneel to greedy and often incompetent emirs. And they were, in the end, confronted by so many different groups opposed to them for so many different reasons that their ignominious demise has long been a part of their tarnished legacy.

Following the Rashidun caliphate of 632-661, then, the Umayyad caliphate of 661-750 is a more marbled, intricate era of central Eurasian history. The Umayyad period, governed by 14 caliphs over the course of 89 years, and encompassing a number of succession disputes and civil wars, is not a straightforward epoch of history. Yet the Umayyad empire also laid the groundwork for a lot of what was to come. It was within this period that Shiism solidified, first as a political movement, and increasingly, a theological one. It was within the Umayyad period that the geographical axis of Islam moved northward, to Damascus, and stretched its western and eastern arms to encompass the Iberian Peninsula and the lower Indus. If the Rashidun period was a tidal wave, the Umayyad period was that tidal wave’s end and aftermath, when the water soaked into the ground, and the populations of central Eurasia and North Africa could start to see what the world to come would look like. Controversial, complex, and above all consequential, the Umayyad caliphate is something about which everyone on earth should learn the basics, and over the next two hours, we’re going to do just that. [music]

Background: The Rise of the Umayyads

In order to understand the Umayyad period, we should first learn where the word “Umayyad” comes from. The Umayyads were a group of people. In the Pre-Islamic period, the Umayyads were a clan, and they were a clan within the larger Meccan Quraysh tribe. Their progenitor, Umayya, was roughly of Muhammad’s grandparents’ generation. Over the course of the mid-500s, the Umayyad clan of Mecca had become a powerful branch of the Quraysh tribe, running caravans up and down between Mecca and Syria. Muhammad knew, worked with, and fought with various Umayyads over the course of his life. During the period of Muhammad’s ministry, his older contemporary Abu Sufyan, the grandson of Umayya himself, was for a long time one of the Prophet’s most powerful enemies. After being opposed to the ministry of Muhammad for two decades, however, and facing Muhammad on the battlefield in 625 and 627, in 630, Abu Sufyan, the leader of the Quraysh establishment who had resisted Muhammad for so long, surrendered, and converted to Islam.2The Umayyads, then, in Pre-Islamic Arabian history, were a powerful clan and trade syndicate. Some of their foremost scions tried to stop Muhammad, and Islam, from expanding between 610 and 630. In doing so, the Umayyads were protecting their economic interests. Involved in northern trade, and also, the beneficiaries of profits from the Meccan pilgrimage circuit, the Umayyad clan saw Islam as a threat to business. A new ideology based on monotheism, equality, and the redistribution of wealth imperiled the system on which Umayyad power was based. The Umayyads weren’t the only old guard Meccan elite opposed to Muhammad and Islam. More generally, Mecca’s aristocracy wanted to safeguard their old way of life from the Prophet, and they fought Muhammad and his followers to do so. And after Muhammad conquered Mecca in 630, the ancient clans and tribes of western Arabia, like the Umayyads, did not simply dissolve into an Islamic unity. Blood is thick, and the tribal order of the Peninsula persisted into the first Islamic empire – the Rashidun Caliphate, which we discussed last time.

When we learn about the Rashidun Caliphate – the central events in Islamic history between 632 and 661 – we essentially learn two stories. The first is a story of expansion and triumph. An Arabian power, united under Islam, flared up from the peninsula and defeated two great empires. But there is another story – the story of tensions seething within that Arabian power. Muhammad’s cousin and son-in-law, Ali, first conceded leadership to Abu Bakr in 632, and then to Umar in 634, and then to Uthman in 644, until finally, in 656, Ali was able to assume control of the empire for a fraught and tragically brief four and a half years. It is important to remember that there was never a time, after Muhammad, when the polity of Islam lined up behind a single person. Factions, motivated by clan ties, economic interests, and old vendettas, and a little later, theological discord, and almost always some combination of these, backed one leader or another, because there were great advantages to having someone of one’s own clan on the throne.

The nature of these advantages became clear when the third Rashidun Caliph, Uthman, ruled between 644 and 656. Uthman was of the Umayyad clan. And Uthman used his time in office to reward his fellow Umayyads lavishly, offering them leadership positions throughout the empire. The most consequential promotion of the third caliph Uthman was the promotion of his second cousin, another of the Umayyad clan, to the governorship of Syria. This second cousin was Mu‘awiya, and Mu‘awiya was the son of Muhammad’s old enemy, Abu Sufyan. Mu‘awiya, the first Umayyad emperor, and a main character in our story for today, liked the way that things were going under the reign of the Uthman from 644 to 656. Old Uthman, though a pious Muslim and companion of the Prophet Muhammad, put Umayyads first throughout the growing empire. And when Uthman was assassinated in 656, his second cousin Mu’awiya, the princely heir of a powerful Umayyad family, wanted Umayyads to remain in power. The problem was that Ali, one of Islam’s first ever converts, and the father of Prophet Muhammad’s grandchildren, was long overdue to take over as chief executive of the newborn empire.

Ali, as we learned last time, proved to be the second most pivotal person in Islamic history, after Muhammad himself. During Ali’s life, there were those who believed that he should have immediately succeeded Muhammad after the prophet’s death in 632. Today, Shias believe that Muhammad named Ali as his successor, and that Ahl al-Bayt, or “the people of the house,” in other words, the genetic descendants of Muhammad, are the only ones fit to superintend Islam. When Ali took the throne, finally, in 656, he did so with the intention of making some changes. The previous caliph, the Umayyad Uthman, had put his clan first. Some of the kin whom Uthman had promoted were egregious in the scope of their greed and ineptitude. Muhammad’s cousin and son-in-law Ali, when he became the fourth caliph, distanced himself from the third caliph Uthman’s administration. Ali’s ascension to the throne signaled an economic reform in the empire’s aristocracy. Ali’s ascension meant that the Umayyad clan’s hegemony, entrenched over the previous twelve years of Uthman’s rule, was now no longer secure. And Ali’s most consequential opponent was Mu‘awiya, that Umayyad governor of Syria who was the son of Abu Sufyan, the onetime arch-nemesis of Muhammad himself.

The showdown between Ali and Mu’awiya that ensued has had titanic consequences. To Shias, and the many besides them who revere Ali, Mu’awiya’s seizure of power in Syria in the late 650s was grossly disrespectful to the legacy of the Prophet, and it hobbled what otherwise would have been a spectacular and enlightened reign. Ali faced off against Mu‘awiya over the course of 657, with Mu‘awiya’s power base in Damascus, and Ali’s in Kufa, in what is today Iraq. The end result of their fighting was that the two men drew up negotiations, and it was decided that Ali would continue to hold power in Arabia, Mesopotamia, and Persia, whereas Mu’awiya and his Umayyad allies would rule in Syria. This capitulation on the part of Ali enraged some of Ali’s supporters, who went off on their own and became a group known as the Kharijites. The Kharijite extremists decided that Ali was not staunch and severe enough as a Muslim, and in 661, a Kharijite assassin killed Ali in Kufa, according to tradition, as Ali led prayers there.

The death of the fourth and final Rashidun caliph opened the way for the first Umayyad caliph, Mu’awiya. But there was a problem. That problem was that Ali had two sons, both of them full blooded grandsons of Muhammad himself, and both in their mid-thirties. And where we last left off, Ali’s older son, Hasan, had followed in Ali’s footsteps. Hasan, as of 661, had also capitulated to Mu’awiya, the Umayyad governor of Syria turned self-proclaimed caliph. Hasan, in the capitulation agreement, guaranteed that he would relinquish his claim on the caliphal throne, provided that Mu’awiya would agree to three conditions. First, Mu’awiya promised not to harm Hasan’s followers. Second, Mu’awiya promised to rule according to Qur’anic doctrines, and the customs of the Prophet Muhammad. And third, Mu’awiya promised that his successor would be chosen by a committee. And now, everybody, it’s time to learn the story of the Umayyad caliphate, and whether or not Mu’awiya, the first Umayyad caliph, kept any of his promises to Hasan, the oldest grandson of the Prophet Muhammad. [music]

The Reign of Mu’awiya (661-680)

In early 661, Mu’awiya became the unopposed caliph of the new empire. His chief rival, Muhammad’s eldest grandson Hasan, had retired to Medina. By July of 661, Mu’awiya had earned the sworn allegiance of many emirs and Arab chiefs. Mu’awiya, however, did not rule from the old Rashidun seat of power in Medina. Mu’awiya ruled from Damascus.3Mu’awiya wasn’t the first caliph to move the throne. Just before him, Ali had ruled from Kufa, in Iraq. But with Mu’awiya, the caliphate’s political control room moved west, to Syria. When we say “Syria” today, we think of the modern country. However, the Arabic name Bilad as-Sham, which we might translate as “greater Syria” better describes Syria during the Umayyad period, a region that included modern-day Syria, Lebanon, Jordan, Israel, Palestine, and the southern fringes of Turkey. This was the region that the Romans called Syria. Greater Syria was ecologically richer than western Arabia. It was an area home to agriculture and pastoralism; to port cities and lumberyards; to the Abrahamic epicenter of Jerusalem, and perhaps most pivotally, to a choice swathe of Mediterranean shoreline that quickly became instrumental to Islamic expansion throughout North Africa.

By 661, when he became caliph, Mu’awiya had deep ties to greater Syria, and he had been digging in there for decades. Just as the Umayyads had long been linked with trade to Syria, Mu’awiya had served as a commander during the early Rashidun invasion of Syria in the 630s, holding ever higher military positions under Islam’s first two caliphs between 632 and 644. Mu’awiya married two women from the Kalb Tribe, a powerful Arab dynasty anchored between modern-day Syria and Arabia. When Mu’awiya’s second-cousin Uthman appointed him to the governorship of Syria, Uthman also appointed other Umayyad relatives to various posts. Some of these Umayyad appointees were terrible at their jobs. Uthman’s Umayyad cousin, for instance, had to flee the city of Basrah, and elsewhere, rebels forced Uthman’s foster-brother out of Egypt. Mu’awiya himself, however, was comparably quite competent as the governor of greater Syria, one of his greatest achievements being the construction of the first Islamic navy. As Uthman’s empire shuddered in the early 650s due to the incompetence of various appointees and various uprisings and military stalemates and failures, Mu’awiya’s Syria was the late Rashidun caliphate’s most important military and economic engine.4

The tomb of Mu’awiya ibn Abi Sufyan in the Bab al-Saghir cemetery in Damascus. The resting place of Mu’awiya is regarded far more ambivalently in the Islamic world than those of Ali and Husayn. Photo by محمد اسماعيل كردية.

In the east, the newly minted Umayyad caliphate faced different enemies. When we learn that Mu’awiya’s caliphal predecessors had conquered the Sasanian empire, along with much of the Byzantine empire’s territory, there is a temptation to assume that new Islamic leadership inherited stable regions with orderly bureaucracies that facilitated a new pattern of tax collection. Some provinces that the caliphates conquered were indeed stable and orderly. But constant turmoil in the Sasanian and Byzantine empires, throughout the entire seventh century leading up to the beginning of the Umayyad caliphate in 661, had emboldened a lot of other Sasanian and Byzantine enemies besides the caliphates. The Khazars, headquartered north of the Caucasus Mountains between the Black and Caspian Seas, fought the Byzantines and caliphates alike throughout the seventh, eighth and ninth centuries. Far to the east, in the regions of Khurasan and Sistan, where modern-day Iran meets Turkmenistan and Afghanistan, the Umayyad caliphate fought the Sasanian empire’s old foes along the lower Helmand River and across the Oxus, including a group called the Hephthalites, or White Huns.

As Mu’awiya’s reign lengthened over the course of the 670s, three other things were happening in the Umayyad empire that would have great consequences for the future of the caliphate. First, the Umayyads pushed westward across North Africa. A naval power, now, and capable of rebuffing Byzantine attacks at sea, by 678 the Umayyads had conquered Byzantine north Africa, excepting Carthage and the area around it. Second, Mu’awiya paid very close attention to the governorship of the Hijaz, where the former capital of Medina was seated. For obvious reasons, Medina and Mecca were theologically central to the caliphate, and Mu’awiya was careful to only appoint Umayyad clansmen whom he knew there. Mu’awiya thus put a second cousin, Marwan ibn al-Hakam, in place as governor of Medina for much of Mu’awiya’s time as caliph.

And while Mu’awiya was paying close attention to the leadership of militarily and ideologically important territories in the 670s, he was also paying close attention to his own dynastic legacy. Mu’awiya had decided that his son, Yazid I, would be his heir. The young man, born into the world of the caliphates, had led a military campaign in Anatolia, and had had an important role in directing the pilgrimage to Mecca, roles that his father evidently assumed would make Yazid I eligible for the throne. With Yazid I installed as caliph, Mu’awiya knew that the Umayyad clan would continue to be able to retain and shore up power. And when Mu’awiya died in 680, his son Yazid I took the throne as the second Umayyad ruler, being the first man to assume caliphal leadership by hereditary right. So much, then, for the old world of tribal shuras that had previously decided Arabian leadership. The caliphate was a hereditary monarchy, and Mu’awiya had broken one of the three promises he had made to Muhammad’s oldest grandson Hasan. [music]

The Reign of Yazid I and the Tragedy at Karbala

By the time Yazid I succeeded his father Mu’awiya as the second Umayyad caliph in 680, Muhammad’s oldest grandson Hasan had passed away. Some time between 670 and 680, Hasan died in Medina. His death is most often attributed to a poisoning, with Mu’awiya being the suspected instigator, although sources have never been unanimous. Mu’awiya had promised Hasan in his peace treaty back in 661 that he would not pass power to an heir without some sort of council. Mu’awiya, however, had broken his promise, and so having Hasan poisoned would have been an instrumental step in Mu’awiya’s bid for dynastic power.Although the sources on Hasan’s death are complicated and partisan, if indeed Mu’awiya abetted Hasan’s murder, the first Umayyad caliph committed a horrendous crime in the name of greed and dynastic self-aggrandizement. Ali, and his eldest son Hasan, once the caliphate had grown into an empire, at different moments both swallowed their pride and ambition for the sake of peacemaking, choosing stability within the caliphate over civil war at the cost of their own power. That Mu’awiya would murder Muhammad’s grandson preemptively, merely for the sake of assuring his own son Yazid I’s claim to the throne shows how quickly history changed between the Rashidun and Umayyad caliphates. And six months after the second Umayyad caliph Yazid I took the throne in 680, another great tragedy would befall Islamic history.

Hasan was only one of the Prophet Muhammad’s two grandsons by Ali. The second grandson, Husayn, was 54 years old in 680. He had, like his brother Hasan, lived quietly in Medina during the first decades of the Umayyad caliphate, in spite of perennial efforts of the supporters of Ali to rally around the Prophet’s grandsons and instigate a revolt against the Umayyad regime in Damascus. For decades, Ali and his sons had enjoyed broad support in what is today southeastern Iraq, from the city of Kufa down to Basrah along the prosperous Euphrates floodplain. With Ali gone, and with Hasan gone, support for the younger grandson Husayn still existed in this region. Husayn’s partisans had, for a long time, urged him to rise up and resist the Umayyad power grabs that had mounted since the caliphate of Uthman had begun back in 644.

When Mu’awiya died in 680, his death signaled the end of the Umayyad leadership’s peace treaty with Ali and his sons. And the appointment of Yazid I in 680 to the throne meant that just as this peace treaty expired, the Umayyads had flagrantly broken the terms of those agreements by choosing hereditary succession rather than appointment by committee. After a life spent keeping a low profile, Husayn finally answered the call for revolt in 680. Muhammad’s grandson Husayn sent an emissary up to Kufa to tell supporters in the north to amass. Unfortunately for Husayn, the second Umayyad caliph Yazid I seems to have anticipated the uprising in Iraq.

Yazid I sent his regional governor in to suppress the revolt. This governor, Ubayd Allah ibn Ziyad, would play a central role in Islamic history over the next five years. The Umayyad governor Ubayd Allah ibn Ziyad first put down the Kufan uprising. The governor had intel that Husayn was heading up from the Hijaz to lead the revolt, along with a small retinue of followers, and Ubayd Allah ibn Ziyad sent a larger force to intercept Husayn. The Umayyad forces confronted Husayn and his retinue near Karbala, in present-day Iraq. When no settlement could be reached, a short battle broke out. When it was over, Husayn was dead, along with the members of his household who had accompanied him.

The Imam Husayn Shrine in Karbala during Arba’in of 2019. Photo by J Ansari.

The annual Arba’in pilgrimage to Karbala was prohibited by Saddam Hussein, but today it is actually far larger than the Hajj to Mecca, with 21 million Muslims having participated in 2024, in contrast to the less than two million who embarked on the Hajj. To be clear, the Saudi government, for reasons of safety and logistics, has to limit the number of Hajj participants, as Mecca’s population is less than three million, and Medina’s less than one and a half. But at any rate, for those of us new to Islam, it’s worth remembering that although the Hajj is one of the pillars of Islam, the pilgrimage to Karbala, largely Shiite, is also a central religious rite in the lives of tens of millions of Muslims today.

The Imams regarded as holy by various branches of Shiism. Through Fatima and Ali’s son Husyan (though he was martyred at Karbala in 680), a prophetic line is still believed to have descended, culminating in different Imams for Twelvers, Ismailis, Zaydis, and other, smaller sects.

Abd Allah ibn al-Zubayr was the grandson of Islam’s first caliph, Abu Bakr. A scion of the Quraysh old guard, and with close familial ties to the Prophet Muhammad, Ibn al-Zubayr had considerable support behind him, being a sort of centrist figure around whom Quraysh leadership uncomfortable with Umayyad dominance could rally. Like Husayn, Ibn al-Zubayr refused to pledge allegiance to the new Umayyad caliph Yazid I in 680. With strong support in Mecca and Medina, by 682, Ibn al-Zubayr’s forces had booted the Umayyads out of Medina. In 683, a counterattack ensued, with Yazid I dispatching a Syrian army southward into the Hijaz. The army retook Medina in the late summer of 683, and then turned its attention toward Mecca. After some months of fighting between the Zubayrids defending Mecca, and the Umayyad Syrians attacking Mecca, the war was interrupted by unexpected news from the north. Yazid I, the second Umayyad caliph, had died after only three years on the throne.

The death of Yazid I in 683 marks the beginning of one of the more turbulent periods of early Islamic history, so let’s slow down for a moment, review what we’ve learned so far, and then consider what we’re about to learn. Last time, we went through the relatively straightforward history of the Rashidun caliphate. The Rashidun caliphate exploded in size under the first two caliphs Abu Bakr and Umar. The third caliph Uthman took charge in 644, and though not without achievements, his reign was marked by a problematic degree of nepotism. By the time Uthman died in 656, Uthman’s Umayyad clan had tasted too much unchecked power to relinquish it, and when Ali took the throne in 656, the First Fitna began. As dire as Islam’s initial civil war surely was to live through, it was a relatively simple affair. First, Ali fought off Quraysh opponents, winning the Battle of the Camel 656, at which the Quraysh contenders for the caliphal throne were killed, and after which Ali made peace with Muhammad’s widow Aisha. Then, Ali’s forces fought those of Mu’awiya to a stalemate, signing a treaty that ultimately led Mu’awiya to stay in power until 680. With Ali’s death in 661, the era of the First Fitna ended. Although open hostilities were stalled by Ali’s sons honoring their father’s agreement with Mu’awiya, throughout the reigns of the first two Umayyad caliphs Mu’awiya and Yazid I, tensions still seethed, tensions which led to the Second Fitna, which rocked the Islamic world from 680-692.

With the Second Fitna, and the death of the second Umayyad caliph Yazid I in 683, we come to a more cluttered and challenging period of early Islamic history. Between Yazid I’s death in 683, and the end of the Umayyad caliphate in 750, there were twelve more Umayyad caliphs, meaning that each was on the throne for an average of less than six years. And just as there were many Umayyad caliphs, the caliphate itself became fissured into different power blocs, power blocs which faced off against one another throughout the Second Fitna of 680-692, and the Third Fitna of 744-747, which we’ll discuss later. As of the year 683, again where we are now in our narrative, Muhammad’s grandchildren’s generation were becoming senior citizens, those who had known him were becoming vanishingly few, and the median Muslim believer was as likely to call Syria, Iraq, or Egypt home as western Arabia. In the remainder of this program, then, although we’ll review the full history of the Umayyad caliphate, I’m going to especially concentrate on the Second and Third Fitnas, and several other events that set the stage for the greater medieval world to come. So let’s jump into the Second Fitna, or Islamic civil war, of 680-692. [music]

The Second Fitna: Umayyads, Shi’at Ali, Zubayrids, and Kharijites

Over the twelve years of the Second Fitna of 680-692, four different groups squared off against one another. We have already met all of them. First, there were the Umayyads, that dynasty rooted in Syria that had grown out of a very powerful old Meccan clan. Second, there were the Alids, or Shi’at Ali, who supported Ali and his sons, and were devastated at the death of Husayn near Karbala in late 680. Third, there were the Zubayrids, Quraysh proponents of the first caliph Abu Bakr’s grandson, ‘Abd Allah ibn al-Zubayr. And fourth, there were the Kharijites. The Kharijites, who had emerged as separatists in 657 after Ali first agreed to share power with Mu’awiya, were religious purists who believed that a caliph must have an impeccable character, and the Kharijites became a volatile force in the Umayyad empire after 657, seated in east-central Arabia and what is today the Fars province of Iran. When the second Umayyad caliph Yazid I died in 683 at an unexpectedly young age, further fissures appeared in the empire, with the mighty Umayyad regime in Damascus suddenly lacking a leader.

The power blocs of the Second Fitna in 686. The Umayyad dynasty, under the newly-enthroned Abd al-Malik, was barely hanging on during the second year of the caliph’s reign. Map by Al Ameer son.

Within the four main splinter groups of the early Second Fitna, there were more splinters. The 680s saw tribal groups who had given support to Ibn al-Zubayr going their own way. A faction of the Shi’at Ali lined up behind a partisan of another of ‘Ali’s surviving sons, a partisan named al-Mukhtar, between 685 and 687, and al-Mukhtar’s forces tried to take control of the rich floodplains of the middle Euphrates region. Most consequentially, though, the Umayyad clan itself faced a fork in the road.

The clans of Arab tribes were, needless to say, made up of multiple families. In the case of the Umayyad dynasty thus far, imperial power had been in the hands of the descendants of Muhammad’s old foe-turned-friend, Abu Sufyan. In 684, however, a new scion of the Umayyad clan presented himself as eligible for the position of caliph. This scion was the third Umayyad caliph Marwan, the second cousin of Mu’awiya. Well-connected, and about 60 years of age, Marwan was a reasonable choice for Umayyad leadership. Marwan, however, only ruled for about a year between 684 and 685. At the time of his death in 685, Umayyad power in Syria was focused on locking down control of the wealthy territories of Egypt and southern Iraq, the Umayyad’s main foe at that point being the powerful Arabian forces of Ibn al-Zubayr.

In 685, a new Umayyad caliph – the fifth Umayyad caliph, to be precise, ascended to the throne. This caliph will be part of our story for a while, as he ultimately ruled for two decades. His name was Abd al-Malik, and he would prove to be a successful and talented leader. The fifth Umayyad caliph Abd al-Malik did not inherit a very sturdy looking throne. When Abd al-Malik ascended to the throne, many within Umayyad territories understood Ibn al-Zubayr, seated in Islam’s heartland of western Arabia, to be the real caliph, and then there were the Shi’at ‘Ali and Kharijites, who loathed the Umayyads for various reasons, not to mention the numerous dangerous groups on the periphery of the Umayyad empire. Within a year of the fifth Umayyad caliph Abd al-Malik’s reign, the Byzantines were not only attacking Umayyad holdings in the Caucasus, but also sponsoring independent Umayyad foes up north.

Following initial attacks against his main foe in Arabia, the other claimant to the caliphate, Ibn al-Zubayr, Abd al-Malik paused to shore up his power in the rich territories of greater Syria. In the late 680s, Abd al-Malik reached settlements with the Byzantines, and hostilities between the two groups broke off. After fending off a cousin’s bid for the throne, and cordoning off some tribes in Syria that had proved rebellious, the fifth Umayyad caliph Abd al-Malik turned his attention to Ibn al-Zubayr, that grandson of the first caliph Abu Bakr whom, by 690, many considered caliph. By 691, Abd al-Malik had taken back much of the Euphrates floodplain and was ready to march on Ibn al-Zubayr’s power center in Mecca. The following year, in 692, Abd al-Malik’s forces converged in Ta’if, and then Medina. And during the Hajj of 692, in April, Umayyad forces attacked the city of Mecca. Though the fifth Umayyad caliph Abd al-Malik had wanted to avoid attacking the sacred square around the Kaaba, fierce resistance in the city necessitated it, and in the siege that followed, the Kaaba itself was damaged.6 In the end, the fifth Umayyad caliph achieved his objective. The supporters of Ibn al-Zubayr, grandson of Abu Bakr, were defeated, and Ibn al-Zubayr himself was beheaded, his remains displayed in Medina. The Umayyads, then, as of 692, as the Second Fitna reached its bloody terminus, were ascendant once more. [music]

Abd al-Malik and Waleed I (685-715)

With the end of the Second Fitna, the continued reign of the caliph Abd al-Malik marked a new period of Umayyad history, often called the Marwanid period, after Abd al-Malik’s father Marwan. For the long stretch between 684 and 750, Abd al-Malik and his sons and other relatives would hold power in Syria, and while they would not rule unopposed, the dynasty enjoyed peaceful transfers of power up until the 740s.Having vanquished opposition from other Quraysh clans in the early 690s, the caliph Abd al-Malik nonetheless still had a gigantic empire to run. The Umayyad caliphate’s largest revenue sources were the agricultural powerhouses of Egypt and Iraq. Egypt was a smaller source of revenue, but it was also easier for the Umayyad regime to govern. Conquered and run by the Syrian armies, the only threat to Egypt were the Byzantines and Berbers to the west along the North African coast. Iraq, or more properly the Tigris-Euphrates floodplain, yielded much greater wealth in agriculture, but it was also more volatile. For the fifth Umayyad caliph Abd al-Malik, Iraq was so wealthy that any governor stationed there threatened to become powerful enough to threaten the throne in Damascus. Further, the cities of Kufa and Basrah had exploded in size, by the close of the seventh century having populations as high as 200,000.7 The site of the old Shi’at Ali resistance, and also, the front with the restless populations of the former Sasanian empire, Iraq had to be watched very closely by the Umayyad headquarters in Damascus.

The most powerful enemy of Damascus, in the early 690s, was Constantinople. And in the early 690s, we first begin to see political rhetoric deployed that would be used at various junctures throughout the Middle Ages to come. The Byzantine Emperor Justinian II began describing himself as God’s earthly representative, around 690 issuing coins with his portrait and the caption “Christ’s servant.” Within a few years, the caliph Abd al-Malik had begun minting coins that described him as the commander of the faithful, and as God’s deputy. The rhetoric itself was not unprecedented on either side.8 Yet occurring as it did in the early 690s, the theocratic propaganda was part of a mutual saber rattling designed to bolster each ruler’s claims to unlimited executive power. The Umayyad goal was the destruction of Constantinople, but the caliphate, in the 690s, had to fight the Byzantines in numerous places other than Anatolia. With two other major fronts between Muslims and Christians in the Caucasus region, and the central North African coast, Umayyad and Byzantine fighting in the late 690s resulted in modest territorial gains for the caliphate.

As the caliphate fought the Byzantines in the 690s, the fifth Umayyad caliph Abd al-Malik also had to manage the empire’s gargantuan eastern front. Uprisings in Iraq, by slaves and then by Kharijites, had to be subdued. The distant east of what had formerly been the Sasanian empire remained an almost ungovernable frontier, with powerful inhabitants of modern-day Afghanistan and Pakistan taking back Umayyad territory nearly as quickly as the caliphate could conquer it. And Iraq, closer to Damascus though it was, remained a tinderbox throughout the Umayyad period. Between 701 and 704, an Umayyad general rebelled and claimed control of the Tigris-Euphrates region. The rebellion was a significant one, and as a result of the relentless turmoil in Iraq, the fifth Umayyad caliph Abd al-Malik ordered a garrison of Syrian soldiers stationed in between the metropolises of Kufa and Basrah – a garrison that could be mobilized in either direction to squash insurrections. This would be a reality for much of the Umayyad caliphate’s remainder – Syrian military boots on the ground in Iraq, deployed to subdue the diverse and porous breadbasket of the caliphate, and deployed further eastward into Iran, if necessary. The Umayyad governor of Iraq, who ruled there from 694-714, is said to have lamented, “Oh, people of Iraq, people of dissension and hypocrisy and vile character,” in a stinging one liner full of rhymes and assonance in the original Arabic. While pejorative statements against entire regional populations are generally unconscionable, the statement nonetheless captures the central paradox of Mesopotamia during the early caliphates – it was always profitable, and always problematic.

Parts of the Umayyad period Dome of the Rock still survive in the modern building atop Temple Mount in Jerusalem.

While the construction of the Dome of the Rock, completed around 692, aimed to undergird the caliphal conquest of Jerusalem, the Dome of the Rock was also part of a propagandistic building program undertaken by the caliph Abd al-Malik. This building program also included projects in Mecca. The Kaaba, which had been damaged during the recent Second Fitna, saw refurbishments between 692 and 694. By putting his stamp on Temple Mount in Jerusalem, and the Kaaba in Mecca, the Umayyad caliph Abd al-Malik effectively made Jerusalem in greater Syria a part of the pilgrim’s calendar, leading the Hajj himself in person in 695.

The fifth Umayyad caliph Abd al-Malik, having won the first Fitna in 692, fought the Byzantine Empire and enemies from Central Asia in the distant east, and as we just learned, worked to associate himself and his regime with the past and future of Islam. Abd al-Malik died in 705 CE, having been on the Umayyad throne for more than 20 years. He was around 60, and although he and his predecessors have been deeply tarnished in Islamic history for their actions against the descendants of Muhammad, Abd al-Malik’s deeds as caliph were also the ordinary sorts of things that early medieval autocrats did in west Eurasia in the seventh century – associating themselves with God, eradicating opposition, and undertaking projects that publicized their grandeur and fitness to rule. Abd al-Malik’s eldest son, al-Waleed I, became the sixth Umayyad caliph, following his father’s death, generally keeping with the traditions his father had established.

Al-Aqsa Mosque in Jerusalem atop Temple Mount. A major site for Islamic worship in Jerusalem today, the building was originally constructed during the Umayyad caliph al-Waleed I. Photo by Yazan Jwailes.

Just as the sixth Umayyad caliph al-Waleed I commissioned some historically pivotal building projects, under his tenure on the throne, again 705-715, the caliphate became even more militarily successful than it had before. Al-Waleed I had a stable of loyal personnel who were happy enough with the benefits that the Umayyad regime was showering on them. And while the monumental building projects of the Umayyad empire are one of its famous legacies, another is an event that took place in the year 711.

Leading up to 711, Umayyad power had devastated Byzantine North Africa. Caliphal armies captured Carthage around 698, lost it, and then recaptured it again. After a few final Byzantine holdout fortresses fell into Umayyad hands, by the year 710, the profitable territories of North Africa were under the military control of Damascus. It was in the summer of 711 that the Umayyads, who had set up a garrison at Tangier in modern-day Morocco, crossed the Strait of Gibraltar. As luck had it, the Visigothic leaders who ruled the Iberian Peninsula at the time were in disarray, and Umayyad forces were able to defeat the Visigothic king and those trying to usurp him, clearing the way for what would soon be Al-Andalus.

While the Islamic conquest of Spain was a pivotal moment in European history, the caliphate’s eastward expansions resulted in the acquisition of a great deal of territory and riches, as well. Eastern commanders, between 705 and 712, fought on the western outskirts of Transoxiana, or the parts of present-day Uzbekistan and Tajikistan across the Oxus River from Afghanistan. Seizing trade centers linked to China in what’s today western Kyrgyzstan, the Umayyad caliphate dispatched diplomats to Tang Dynasty rulers. The Umayyad caliphate’s eastern commanders also pushed down into the Sindh region of southern and central Pakistan, and the lower Indus Valley, yielding enormous profits for the caliphate.

With the territories under its military control now stretching from Portugal to India, and from Yemen up to Georgia and Azerbaijan, the Umayyad caliphate was, by 715, ascendant. Under Abd al-Malik and his son al-Waleed I, who had ruled for a combined 30 years, the caliphate had managed to expand and consolidate its power in Damascus even in spite of the considerable forces working against it. But when al-Walid passed away in 715, followed by three subsequent caliphs with short reigns, the Umayyad caliphate’s luck began to change. [music]

Military Failures, Demographic Evolutions, and Short-Lived Caliphs: 715-724

The seventh Umayyad caliph ascended to the throne in 715. His name was Sulayman, and he was the son of the fifth caliph and the brother of the sixth, so his qualifications for leadership were impeccable. Sulayman’s name – the Arabic version of Solomon – seemed to harken a providential time to come. The hundred-year anniversary of the Hijra from Mecca to Medina was coming up. A leader with a storied biblical name had come to follow two successful reigns that had led up to his own. The time had come to put an end to Constantinople, and the idolatry of the Christians in their persistent belief in a trinitarian God.

The Umayyad empire at its apex. Note the significant territorial gains that took place between just 661 and the end of al-Waleed’s reign in 715. Map by Cattette.

However, in the summer of 717, the Umayyad military also ran into some problems. First, the propitiously named new caliph Sulayman died of an illness in September of 717. Second, while the Byzantines had suffered from a long series of leadership hiccups leading up to 717, in 717, those leadership hiccups stopped. The emperor Leo III, the founder of the Isaurian Dynasty, came to the throne, where he would remain for the next 24 years. One of Leo III first diplomatic feats was making an agreement with a barbarian population called the Bulgar Khanate. The Bulgars of Thrace, after whom Bulgaria is named, had been harrying the Byzantine northeast for a long time, and after Leo III reached a settlement with them, the Bulgars were happy to attack the Umayyad land army instead. The 717-718 siege, sometimes called the Second Arab Siege of Constantinople, grinded on until August of 718, when the fleeing Umayyad navy was battered by Byzantine pursuers and then mostly sunk by an Aegean storm.

Back in Damascus, fortunately for the caliphate, no succession dispute followed the seventh Umayyad caliph Sulayman’s passing. An eighth caliph lasted only two and a half years, and then a ninth didn’t make it to four years. Sulayman’s two short-lived successors, who ruled from 717-724, came to the throne when the caliphate’s failures at Constantinople still loomed large in the collective memory. And the eighth and ninth caliphs also ruled over a period during which Islamic history was changing so quickly that one generation’s realities were quite different from the next, again and again.

Perhaps the biggest change was the demographic evolution of the caliphate’s population. The amount of money that had gushed into the powerful clans of Arabia and Syria meant that aristocratic men of fighting age didn’t need to fight any more. As a result, there were many denizens of conquered populations who, due to ambition or coercion, made up a large portion of the Umayyad military. Earlier, back in Rashidun days, an Arab-Muslim elite had been a thin layer of military men and administrators ruling from garrisons. By 720, though, cohabitation, collaboration, and intermarriage had created a porous space in between the Umayyad aristocracy and the various groups who served them. These groups were understood as mawali, an Arabic word that, as we learned last time, can be translated as “client,” or “ally,” or “friend.” Freed slaves and mercenaries assumed various client relationships with the Arab elites of various regions, client relationships rooted in military allegiance. As time passed, clientages based on assistance, or a patron converting a client to Islam, or simply friendship, continued to fuel upward mobility for populations living beneath the Arab clans who held the lion’s share of power in the Umayyad empire. There were Arabs, however, who resented the upward mobility of conquered peoples into the ranks of the Arab patricians, and the later Umayyad caliphate would see tensions between indigenous populations and Arab leadership playing out in various problematic ways.

When we consider the client-patron relationships of the later Umayyad empire, it’s important to remember the scale of this empire. A Nestorian Christian sailor from what is today Lebanon, working with a mixed crew, might shake hands with the Arab admiral who commanded a fleet with little reservations. The Arabs were no better or worse than the Byzantines, who had also oppressed the Nestorians, and so having an Arab patron was fine. But the Umayyad empire was absolutely titanic, and it included various militarily competent groups who had other alliances in the outside world that they could make, rather than alliances with the Arab elite. The Visigoths of the recently conquered territory of Al-Andalus, for instance, had Merovingians on the other side of the Pyrenees. Berbers had connections with a whole network rooted in the Sahara. The armies of the Khurasan and Sistan regions in the distant east had partnerships with India and China. The newly won frontiers of the empire, put simply, were not as safe as the interior for Umayyad aristocrats. Indigenous citizens of the frontier zones knew the lay of the land far better than their Arab conquerors, and the aforementioned Visigoths, Berbers, citizens of Transoxiana, and others, could form powerful alliances with groups fully out of the purview of the Umayyad caliphate.

In summation, then, after failing to take Constantinople in 718, and then having two short-lived caliphs rule over the next six years, the Umayyad empire faced the cold, hard reality of now occupying an absurd amount of territory, being surrounded on all sides by capable enemies, and internally, facing evolving challenges with the governance of colonized populations. In 724, however, the caliphate had a stroke of luck. The tenth caliph, Hisham ibn Abd al-Malik, ascended peacefully to the throne, being in his early thirties, competent, and qualified to rule. Unlike his most recent predecessors, the tenth Umayyad caliph Hisham would have a long tenure on the throne. The last caliph whom we’ll consider in detail in this program, Hisham also had a combination of cautiousness, pragmatism, and foresight that managed to hold the Umayyad caliphate together, as well as to spread knowledge and culture throughout the vast empire. [music]

Hisham ibn Abd al-Malik, the Tenth Umayyad Caliph (724-743)

The tenth Umayyad caliph Hisham ibn Abd al-Malik, who ruled from 724-743, continued the policies of his predecessors, and commenced new ones that fit the changing times. Like other Umayyads before him, he patronized the Hajj, leading the pilgrimage in 725, and building infrastructure on the Syrian road to west Arabia to help pilgrims get down to Mecca. He kept up the steady military campaigns against the Byzantines. In order to facilitate these campaigns, and due to his own land holdings, Hisham moved his permanent residence from Damascus 200 miles to the northeast, to the city of Resafa, in the north-central part of modern-day Syria.

Turkic Khaganates thrived in Central Asia from the earliest days of the Islamic caliphates. Half a century into the Abbasid caliphate, Turkic peoples would become a significant influence on the Islamic empire.

The cities of Kufa and Basrah had swelled to a quarter of a million citizens each by the reign of the tenth Umayyad caliph Hisham, and the diverse and energetic populations in these cities became wellsprings for progressive and revolutionary ideas. When the tenth Umayyad caliph Hisham came to the throne in 724, Shi’at Ali, or the party of Ali, still hoped Ali’s descendants would return to power. The partisans of Ali had, of course, not forgotten that the Umayyads had been directly or indirectly responsible for the deaths of Ali, Hasan, and Husayn, and they were thus certainly not supporters of the Umayyad regime.

Another power bloc resident in Iraq and Iran were the Kharijites. The Kharijites not only rejected Umayyad rule. They rejected Quraysh leadership more generally, embracing the Qur’anic doctrine that all Muslims are equal, and thus that in any leader, piety and personal merits were what counted, rather than tribal pedigree. And the Kharijites did not confine their ministry to the central part of the empire. Spreading their message to North Africa and other regions, the Kharijites told any who would listen that the Umayyad dynasty had to go. In general, conquered populations did not need to be told twice that they were being ruled over by a decadent and unrighteous regime, and for non-Arab Muslims in general, some of whom had to pay an extra tax even though they were Muslims, the Kharijite message of equality before God and pious living resonated quite well.

Though Kufa and Basrah generated firebrand ideas like those of the Kharijites, the Mesopotamian cities were also, even in the early 700s, important to the later cultural history of Islam. Intellectual luminaries came into prominence in Kufa in and after the first quarter of the 700s, including the Sunni jurist and historian al-Sha’bi, and Abu Hanifa, the scholar, jurist, and theologian who founded the Hanafi school of Sunni law, today the most prevalent school of Islamic law on Earth.

By the 720s, internal unrest was a given in the Umayyad empire, and the tenth Umayyad caliph Hisham delegated management of this unrest to a large cadre of loyal governors. Hisham also kept up the family tradition of making war on the Byzantines, wanting to be the Umayyad who finally conquered Constantinople and completed the final triumph of Islam over Christianity. Constantinople, however, was now under strong leadership. Its emperor, Leo III, had firm alliances in place with the Khazar Khagnate based in the upper Caucasus, and Khazars raided Umayyad territories in what is today Georgia, Armenia, and Azerbaijan, making a Muslim mobilization into Anatolia in the 720s and 730s tactically unwise. To skip through a great deal of military history pretty quickly, over the course of the 730s, the Umayyad caliphate nearly captured Sicilian Syracuse, and faced the Byzantines in a large land battle in 740, but the Umayyads lost both engagements, suffering further public relations losses within the caliphate as a result.

The Battle of Tours (732): The Big Picture

Perhaps the most famous military debacle of the Umayyad empire, at least in European history, was the Umayyad defeat at the Battle of Tours, in present-day France, in 732. The Umayyad empire had, following its initial invasion of Hispania in 711, locked down control of much of the Iberian Peninsula, seizing territories from the Visigothic crown and nobility during the 710s. Detailed records of the Muslim conquest of Spain, and the early history of Al-Andalus more generally, are notoriously sparse, being restricted to far later Muslim sources, and a single Christian account most often called the Chronicle of 754, an account that is contemporary but nonetheless not very detailed.9 Visigothic Spain, as we learned in a previous episode, had become Catholic back in 587, but the Iberian Peninsula was, even by the early eighth century, still ideologically and demographically diverse, with the Visigothic monarchy ruling over various populations indifferent to, or hostile to, Visigothic rule. The non-Catholic Christians of the peninsula, as well as Jews, when the Umayyad military disembarked in 711, would have felt no special fondness for the Catholic monarchy that ruled over Iberia, which itself suffered from perennial succession disputes and uprisings by the nobles of powerful fiefdoms. Thus, when Umayyad armies conquered Spain in the 710s, they were a militarily proficient empire marching into a feudal world whose internal population was already discordant, and Visigothic Spain did not last long under the assault of the caliphate. Then, the caliphate turned its attention northward, into the heart of western Europe.For centuries, the Merovingians and Visigoths had sparred over a territory the Romans called Gallia Narbonensis, essentially the southern part of France along the coast, excluding Aquitaine. This region became the northeastern tip of Umayyad territory in Spain, a stretch of France’s Mediterranean coast up to the modern-day city of Narbonne. The Umayyad empire had a base of operations there by 719, spending the 720s securing new landholdings throughout the Iberian Peninsula. As is always the case with imperial expansions in history, though, the armistice in military expansion dried up the river of loot that had empowered and legitimized the conquering force’s leadership, and so further hostilities against unconquered regions became a necessity. In the case of early Umayyad Al-Andalus, the sources of loot most ready at hand were the cathedrals and abbeys of the Frankish territory to the north.

In Francia, at this point, the office of the majordomo, or mayor of the palace, had come to be the real power behind the Merovingian monarchy, and the majordomo Charles Martel, when he assumed his office, would have been well aware of the crisis situation on the southern side of the Pyrenees. Charles Martel ruled Francia from 718-741, and, as students of European history know, he was the father of Pepin the Short, the first Carolingian king, and the grandfather of Charlemagne, the most famous Carolingian king. To turn to the subject of the Battle of Tours of 732, this battle has often been understood as a turning point in European history. The historian Edward Gibbon wrote that:

A victorious line of march had been prolonged above a thousand miles from the rock of Gibraltar to the banks of the Loire; the repetition of an equal space would have carried the Saracens to the confines of Poland and the Highlands of Scotland; the Rhine is not more impassable than the Nile or Euphrates, and the Arabian fleet might have sailed without. . .naval combat into the mouth of the Thames. Perhaps the interpretation of the Koran would now be taught in the schools of Oxford, and her [pupils] might demonstrate to a circumcised people the sanctity and truth of the revelation of Mahomet.10

This is a famous quote about the Battle of Tours of 732, portraying it as the decisive clash between the Umayyad caliphate and the post-Roman monarchies of western Europe. Historians evaluating the Battle of Tours of 732 have run the gamut between deeming it a cataclysmic contest between Christianity and Islam, and deeming it a border skirmish in which a force trying to raid the rich churches of Tours were rebuffed. The real answer probably lies in between these two extremes. Had Umayyad forces, led by their general Abd al-Rahman al-Ghafiqi, prevailed at the Battle of Tours, they might have indeed secured a larger geographical footprint in western Europe. At the same time, though, looking at the greater ebbs and flows of the Umayyad empire, it’s hard to imagine that the caliphate could have somehow persisted infinitely in its military and ideological expansion. Turkic peoples in the east were already retaking stretches of present-day Afghanistan, Pakistan, Tajikistan and Turkmenistan. The Umayyad power centers of northwest Africa, won in a blitzkrieg between 690 and 710, were trembling beneath the pressure of indigenous rebellions. Mesopotamia had never been stable, and there were ineradicable ideological fissures between the Umayyads and their Shiite and Kharijite dissidents. And as always, the caliphate was always one succession dispute away from implosion and fragmentation. So, while it’s possible that the Umayyad caliphate might have carved a swathe of Frankish territory for itself if it had won the Battle of Tours in 732, even a victory at Tours would hardly have guaranteed the Islamization of western Europe.

The Battle of Tours, then, was important, but quite not the civilizational clash it’s sometimes been imagined as. It was followed by a second, and much less often discussed Umayyad invasion of Francia between 735 and 739 – an invasion that managed to capture Arles, Avignon, and much of the southern coast of France. This second invasion was also rebuffed, suggesting that even at maximum size and strength, the Umayyad caliphate had just grown too large too quickly to gobble up any more territory from well-organized defenders.

The Battle of Tours of 732 occurred precisely a hundred years after the death of Muhammad in 632. And as the 730s led into the 740s in the Umayyad empire, and the tenth Umayyad caliph Hisham grew more adept at his role, changes were afoot all over the Islamic world. We have explored, in this program so far, how Umayyad leadership rose out of the bloody and morally murky tumult of the first two Fitnas, how the caliphate continued to stretch to the east and west, how it fought the Byzantines and suppressed internal revolts, and just now, how even in the 730s, it displayed more potential to expand. We have now come to the late afternoon and dusk of the Umayyad empire, and a series of events that brought a new dynasty, soon to be called the Abbasid caliphate, into prominence. [music]

The Qays-Yaman Rivalry

As of the year 740, the Marwanid branch of the Umayyad dynasty had endured for 56 years, through the caliphates of seven different rulers. For more than half a century, in spite of the tribalism of high-level caliphal politics, and the unstable nature of entire time zones of the empire, one subset of one clan of one tribe had held onto power. Within ten years, however, the Umayyads would be finished. What toppled them was a rapid-fire procession of calamities that it’s hard to imagine any imperial regime withstanding.

The Umayyad caliphate and Byzantine empire as of the Third Fitna. Civil wars always meant that the caliphate’s external enemies and internal power blocs would try to divide and conquer the empire. Map by Constantine Plakidas.

Throughout this program, at several junctures we’ve considered some of structural fault lines of Umayyad society. The Umayyad empire was a layer cake, and the layers didn’t always like one another. Autocratic power appointed regional governors with fealty in mind more often than competence. Demographically, Arab Muslims were the gentility, non-Arab Muslims beneath them, and then Christians and Jews, and then others. Throughout these various echelons of society, sometimes, unexpected shared interests begat volatile alliances, and when executive leadership wobbled through succession disputes, or lost clout due to military failures, the strata of entire regions of the caliphate transformed. One of these transformations, by 740, had taken place in the Umayyad power center of Syria, and it would commence the end of the Umayyad caliphate.

We have often, in this season on early Islamic history, learned about the tribal divisions of Arabs and adjacent groups in Late Antiquity. It’s worth repeating, every once in a while, that the Arabian Peninsula is the size of western Europe, and that the tribes and clans of this region had significant cultural and linguistic differences from one another. When the era of the caliphates began, these Arab tribes and groups were thrown into unprecedented proximity together. Living in garrison towns, serving in the military, occupying new bureaucratic positions, and living adjacent to barbarian frontiers, Arab tribes shared homogenizing experiences, including, of course, participation in the egalitarian monotheism of Islam. However, a century of propinquity and shared experience within the novel world of the intercontinental empire could not efface the ancient cultural differences between Arabia’s tribes, nor tribal consortiums.

The latter – tribal consortiums – is an important cultural phenomenon to keep in mind when we consider the twilight of the Umayyad empire in the 740s. Broadly, the inhabitants of Late Antique Arabia understood that Adnani Arabs were northern, and Qahtani Arabs had roots in the southern peninsula. Over the course of the Umayyad caliphate, this north-south polarity became increasingly complicated, as tribes moved around and forged situational partnerships somewhat independently of their ancient heritage. By the year 740, a general fissure existed in Umayyad society that historians call the Qays-Yaman rivalry, with Qays faction being the faction with northern roots, and the Yaman group having southern roots. This fissure’s center was not the Hijaz, nor the Arabian Peninsula itself, nor, certainly, Iran or North Africa, but in Syria, smack dab in the middle of where Umayyad power had always been seated.

Central to the Qays-Yaman rivalry was a tribe called the Kalb. The Kalb tribe, though it had bygone southern roots, was seated in Syria during the time of the caliphates. Kalb women married Umayyad men, and much of the Umayyad dynasty was from the confluence of these two tribes, the Umayyad side part of Muhammad’s own Quraysh tribe, and the Kalb side hailing from the caliphal power center of Syria. This union of clans produced a formidable line of leaders. But it also left others out of power. When the tenth Umayyad caliph Hisham died in 743, another wing of the Umayyad clan saw his passing as a chance to assert their power.

The caliph Hisham’s wish had been that his son would succeed him on the throne. His son represented the established confluence of Umayyad and Kalb power – the primacy of a southern tribal group. However, another wing of the Marwanid family propped up a different heir – the caliph’s brother’s son, who ended up ascending to the throne in 743. This eleventh Umayyad caliph, al-Waleed II, was associated with the Qays, or northern consortium. Al-Walid ruled for less than a year and a half. He began his reign by imprisoning and humiliating his rivals for the throne. The northern-aligned Umayyad caliph declared that he had divine right to rule, and that his sons would rule after him. His cousin, Yazid III, a southern-aligned Umayyad, saw to it that al-Waleed II was besieged and killed. This usurpation, which took place in 744, began what historians call the Third Fitna, and the assassination marked the first time an Umayyad had been killed in office since the death of Uthman, ninety years prior.

The usurper, the son of Hisham and scion of the old Umayyad-Kalb partnership, was again called Yazid III. Yazid III died of an illness in late 744, however, less than six months after being on the throne. His plan was to be succeeded by his son, but the northern-aligned Umayyads still wanted one of their own on the throne, and in 744, the empire descended into civil war.

The Third Fitna of 744-750 was an enormously complicated sequence of events that unfolded across many different time zones. Calling it a civil war is an oversimplification. The Third Fitna immediately began because two branches of the Umayyad clan both sought the caliphal throne for themselves, as we just discussed. But as the Third Fitna expanded into an intercontinental crisis, all of the powder kegs on which the later Umayyad caliphate rested exploded at once, from Egypt, to Syria, to Arabia, to Iraq, to most consequentially of all, Iran. [music]

The Third Fitna’s Beginning

The Third Fitna of 744-750 – to be very clear, the sequence of events that led the Umayyad caliphate to transform into the Abbasid caliphate – the Third Fitna ultimately took place due to broad-based internal dissent against the Umayyad dynasty. The Umayyad dynasty arose in large part because it snatched power from the hands of Muhammad’s family. The first power grab, the First Fitna, from 656-661, was from Muhammad’s cousin and son-in-law ‘Ali. The second power grab, the Second Fitna, from 680-692, began with the murder of Muhammad’s grandson Husayn. By the time of the Third Fitna of 744-750, though two generations had passed, a constellation of different groups had hardened that were opposed to the Umayyads due to the clan’s monopolization of power for the past century. And when the Umayyad clan splintered into northern-aligned Qays Umayyads, and southern-aligned Yaman Umayyads – in other words, when the Umayyads started fighting among themselves, their enemies began fighting them, as well.The last Umayyad caliph – the fourteenth – was Marwan II. Marwan II would rule from 744-750, although the word “rule” should probably be in quote marks next to his name, as the last Umayyad caliph spent most of his reign trying to stop things from exploding. Marwan II was a northern-aligned Qays Umayyad, and he might, ascending to the throne, have expected to fend off rivals from the other side of the family and then proceed over a stable caliphate long afterward. Not knowing just how much chaos the next five years would bring, Marwan II began his reign swatting down rival Umayyad claims to the throne. By the end of 744, Marwan II had managed to fend off his immediate southern-aligned Umayyad rivals, which was a good start.

The problem was, though, that as 744 led into 745, a combination of new and old insurgent groups in the empire were appearing far more quickly than any regime could put them down. An Egyptian governor, in 744, tried to secure new rights for Egyptian Arabs, though he did not succeed.11 An uprising of Shi’at Ali flared to life in Kufa, also in 744, and although it was suppressed, the Alid leader fled to western Iran and secured territories there for much of the next year. Throughout 745, as Shi’at Ali gained ground in western Iran, up in northern Iraq, the purist Kharijite sect instigated a large-scale revolt, naming one of their own as caliph. This Kharijite caliph, by the next year, had raised a large army. Also in 745, down in Yemen, another Umayyad dissident declared himself caliph. The final Umayyad caliph Marwan II could not move quickly enough to put out all of these fires.

Caliph Marwan II did what he could. From 745-6, Marwan II flexed his muscles in the ancestral Umayyad headquarters of greater Syria, seeing the largest threat to his power as the rival southern-aligned Umayyads and wanting to maintain control of the empire’s military seat at all costs. After securing Syria and the Levant in 746, Marwan II hurried to Iraq and fought the Kharijite rebel army there, managing to win and then execute the rival Kharijite caliph late in 746. By 747, after a great deal of effort, Marwan II had reestablished control of Iraq. But that same year, on the other side of the Zagros Mountains, in western Iran, Marwan II faced another rebellion.

This rebellion was made up of a coalition of Shi’at Ali and Kharijites, who at that point had more in common with one another than they did the Umayyad regime. The Shi’at Ali and Kharijites had different ideas about who should rule as caliph. But the Shi’at Ali and Kharijites strongly agreed that the Umayyads should not rule as caliphs. In spite of this partnership, though, in 747 Marwan II defeated the combined forces of the Shi’at Ali and the Kharijites, retaking western Iran for the Umayyads.

From what you’ve heard so far about the Third Fitna, it sounds as though by 747, the final Umayyad caliph Marwan II had things in hand. He had, after all, swatted down sedition throughout the vast reaches of the empire, from Egypt to western Iran. Marwan II, however, ultimately could not overcome the problems that had beset the Umayyad caliphate since its inception. First, many within the empire were furious about Umayyad leadership’s actions against Ali and his sons, most notably the Shi’at Ali, which by the 740s had consolidated into a powerful internal in polity Iraq and Iran, notwithstanding its recent military defeats. Second, there were many working-class Arab Muslims, and various non-Arab Muslims, who had found their treatment at the hands of the Umayyad elite to be unfair, not to mention non-Muslims and slaves who felt the Umayyad yoke especially heavily on their necks. Third, there were purist sects, among them the Kharijites, and more recently, the Ibadis of what is today Yemen and Oman, whose vision of Islam’s future did not include an Umayyad autocracy. By the year 747, these groups, and others, had significant overlapping interests, the most immediate of which was taking advantage of the north-south strife within the Umayyad clan in order to end that clan’s hegemony. And over the course of the 740s, a new group had also come into prominence in the empire that also wanted Umayyad leadership of the caliphate to end. This group was called the Hashimiyya, and would eventually be called the Abbasids. [music]

The Abbasid Revolution (747-750)

The Hashimiyya were so named because they wanted the Hashemites, the clan of Muhammad, to be in power. The Hashimiyya movement, by the year 747, was an anti-establishment coalition that many existing disenfranchised groups could get behind. The Shi’at Ali, who wanted Alid rule, definitely wanted power in the Hashemite clan, because the Hashemite clan was Ali’s clan, as well. The Kharijite purist sect shared the Hashimiyya’s revolutionary agenda, seeing within it the possibility of turning toward a more pious version of Islam and away from the sometimes decadent excesses of Umayyad rulers. What helped make the Hashimiyya an effective resistance bloc in the long term was the group’s caution, and its initial collaboration with other revolutionary groups. Taking advantage of all of the broad-based dislike of Umayyad power, the Hashimiyya sprang into action between 747 and 748, and they did so into the distant territory of Khurasan, where Iran, Afghanistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan come together today.By the late 740s, the Khurasan province – the caliphate’s extreme northeast – was home to a unique population of commingled Arabs and Persians. Khurasan was less densely populated than other regions conquered by the first two caliphates, and Khurasan had fewer garrisons and garrison towns. Subsequently, the Arab settlers who moved to Khurasan had put roots down alongside Persian neighbors, and throughout the region, colonizers and colonized were culturally hybridizing in a way not very common in the rest of the empire. The result of this cultural synthesis, in the politics of the late 740s, was a progressive new populace for whom the faraway Umayyad autocracy was superfluous.

An imaginative portrait of Abu Muslim (c. 720s – 755 CE) from an Ottoman genealogical work done during the 1580s.

The disarray in Khurasan had roots in the Umayyad clan’s civil war. In Khurasan, a northern-aligned Umayyad governor had been locked in conflict with a southern-aligned Umayyad governor. The conflict between these two Umayyad governors is itself a long and dramatic story. For our purposes, it will suffice to say that as Umayyad factionalism up in Khurasan grinded on from 743-747, the region ended up being a rallying place for many different groups opposed to Umayyad rule, who temporarily united underneath the Hashimiyya banner long enough to overthrow the regime. To summarize the saga pretty quickly, the Hashimiyya sectarian Abu Muslim set the rival groups of south- and north-aligned Umayyads against one another in 747, and when the dust had settled, by late 748, the two rival Umayyad governors of Khurasan were dead, and Abu Muslim controlled Khurasan. The Hashimiyya then moved quickly for the jugular of the Umayyad caliphate, and the Umayyad caliphate’s terminal battles all took place in Iran. Hashimiyya armies, between 748 and 750, fought and defeated Umayyad armies, until in January of 750, at the Battle of the Zab, the Umayyad military suffered a final and crushing defeat. Marwan II, the last Umayyad caliph, escaped the battlefield, and in August of 750, he was captured and executed, being one of many Umayyads to die in a bloody purge by the new regime that had taken power.

This new regime was the Abbasid dynasty, and the events that I’ve just described to you are often called the Abbasid revolution. While the history of the early Abbasid caliphate will be the subject of our next program, we should still pause for a moment here and get an idea of how the consortium of dissidents that united beneath the Hashimiyya over the late 740s turned into a new full-fledged caliphate. The answer is actually fairly simple. The Hashimiyya’s general mantra was that Muhammad’s Hashemite clan ought to be in charge. The thing was, though, the Hashimiyya had someone very specific in mind, though they did not proclaim him caliph until very late in the game. This someone was Abu al-Abbas as-Saffah, the great-great grandson of the Prophet Muhammad’s uncle al-Abbas. Al-Abbas, then, the patriarch of the Abbas branch of the Hashemite clan, is where the Abbasid caliphate gets its name – descendants of al-Abbas, Abbasids. The first Abbasid caliph Abu al-Abbas as-Saffah, or more commonly, as-Saffah, proclaimed himself caliph in 750, following numerous major victories over Umayyad armies.

This proclamation struck different portions of the Islamic world differently. As you’ve learned throughout this program, by the year 750, the Umayyads were facing opposition from a variety of different groups. Though the family’s decadence and corruption has likely been exaggerated by later Abbasid sources, Umayyad nepotism had had a pernicious effect on the Islamic world for over a century by 750. In spite of the Abbasid revolution having toppled the much-disliked Umayyads, the ascension of as-Saffah to the throne in 750 was a devastating disappointment to one faction of Islamic society in particular. This was Shi’at Ali. The supporters of Ali had understood that the Hashimiyya movement would enable the surviving descendants of Ali to take the caliphate. When the Hashimiyya movement turned into the Abbasid caliphate in the year 750, the party of Ali, or Shi’at Ali, realized that the Hashimiyya movement had always had Abbasid power as its goal.12 And though the Abbasid caliphate’s inauguration in 750 opened up a prosperous and spectacular era of Islamic history, it also swept some sectarian groups under the rug, the most important of which were Shi’at Ali, and the Alid descendants of Muhammad’s Hashemite clan.

As Abbasid history opened in the 750s, Abbasid caliphs dealt with the descendants of Ali in various ways, sometimes honoring them as advisors and giving them imperial posts, and at other junctures, being suspicious of them as potential usurpers of power. As for the Alids, Ali’s descendants also varied in their fealty to the early Abbasid caliphs. And while Alid family members played power politics with Abbasid family members at high levels across the second half of the 700s, by 800, Shi’at ‘Ali had consolidated into the Shiites. Regardless of whether a descendant of Ali was eligible for caliphal power, the Shiites, by 800, were a firm power bloc within the Abbasid empire, a power bloc with their own theological identity, their own regional ties, and their own demographic appeal, frequently drawing the interest of Persian converts not served well by the old Arabian dominance of the Islamic empire.

Although the Abbasids were just another Quraysh clan, now in charge, their ascension signified major changes. The caliphate was no longer a fresh innovation, and its territories had seen several generations of Islamic traditions. When the first Ummayad caliph Mu’awiya seized power back in 661, a brittle grid of Arab garrison towns were staked into a giant new geographical area. Almost a century later, even though 90% of the caliphate was still not Muslim, the populations who would live underneath Islamic regimes to come had become acquainted with one another. The first two caliphates – the Rashidun caliphate, headquartered in Medina, and the Umayyad caliphate, headquartered in Damascus, had more than anything involved militarized expansion. The third caliphate, though, soon to be headquartered in Baghdad, would be characterized by cultural efflorescence rather than conquest. The Islamic golden age, after all, would be golden because of Islam and the Arabs who had brought it into the larger world, but also, because of everyone else who lived in the empire, as well. [music]

Qusayr ‘Amra and the Greco-Syrian Influence on Umayyad Culture

Over the course of these past two programs on the Rashidun and Umayyad caliphates, we’ve watched the world change very quickly. Between 632 and 750, the old Byzantine-Sasanian front became the center of a new empire, and the demographics and economies of an entire supercontinent transformed at a large scale. We have explored the events of the first two caliphates using a common historical methodology – learning about how an unfolding sequence of caliphs came to be, and how executive leadership of the Rashidun and Umayyad caliphates shaped and reshaped central Eurasia and North Africa. We now have a basic grasp of how the first Islamic empires grew from a very small population of believers in early seventh century Mecca. In the next program, we will move forward through the first century of the Abbasid caliphate, and explore how Abbasid cities and institutions set the stage for some of humanity’s finest intellectual and cultural achievements during the early Middle Ages.It’s important to study history in the way that we have in this and the previous program – military expansions, imperial reigns, large factional clashes – in a word, the big stuff that helps us divide history books into chapters. It’s also important, however, to study historical minutiae, and in the closing portion of this program, I’d like to consider the culture of the Umayyad period in a bit more detail. And we will begin by talking about a single, and very important building – a building that I don’t imagine too many people listening have ever heard of.

Qusayr ‘Amra in Jordan. Only part of the original palace complex still survives today. Photo by Paul Mannix.